9 |

Social phobia |

Social phobia (also known as social anxiety disorder) is natural, because everyone – or nearly everyone – suffers from it occasionally. Most of us can remember a time when we have felt embarrassed by something we have done, or have made fools of ourselves in public. But social phobia is a more extreme and persistent kind of social anxiety that interferes with people’s lives, sometimes in serious ways. When suffering from social phobia people feel apprehensive or nervous interacting with others, or uncomfortable in their presence. This makes it hard to feel at ease around other people, and to be spontaneous and natural in conversation. Talking to people, or knowing that they are being observed, can be enough to make someone with social phobia feel worried and self-conscious. Common fears are that they will do something embarrassing or humiliating and that others will then make critical judgements about them. So they will end up feeling rejected and inadequate. Socially phobic people do not have to do something embarrassing or humiliating to feel upset and anxious – they just have to think that they might, or that they already have, and that others have noticed, or think that they soon will. No wonder that at times they want the floor to open and swallow them up.

There is no hard and fast way of making the distinction between social phobia and common, manageable social anxiety. This is important as it means that no treatment will get rid of the problem altogether. The main aims of treatment are therefore different: to help people feel less distressed by social anxiety, and to stop the anxiety interfering with their lives. Then they can make friends, build families, go to work, and do other things they want to do, including allowing others get to know them more easily. When you have social phobia it is hard to feel at ease in the company of others, and to ‘be yourself’. This means that the people we meet may not be able to discover how interesting, or thoughtful, or energetic or generous we can be. One of the rewards of learning to overcome social phobia is that you can then express yourself in ways that may previously have been stifled by feeling anxious: to enjoy, rather than to fear, being yourself.

Social anxiety affects our body, our feelings, our behaviour and our thinking, but it does not affect everyone in exactly the same way. Think about what you notice happening to you when you are anxious in social situations; if the things that you notice are not on the list below, then add them for yourself.

Examples of effects on your body:

• Shaking or trembling

• Sweating

• Blushing

• Tension

• Racing heart

Examples of effects on your feelings or emotions:

• Panicky feelings

• Fear, apprehension, nervousness

• Frustration, irritation, anger

• Shame

• Sadness, depression, feeling hopeless

Examples of effects on behaviour:

• Avoiding people, places or activities

• Escaping from difficult situations

• Protecting yourself from things that you fear

• Trying not to attract attention

Examples of effects on thinking:

• Worrying about what others think of you

• Becoming painfully self-conscious and self-aware

• Dwelling on things that you think you did wrong

• Believing, or assuming, that you are inadequate

The four kinds of symptoms are closely linked. For example you can’t think what to say, so you feel upset and self-conscious, look away (your behaviour), and start to blush (a bodily change). Then you are so aware of blushing that it gets even harder to think what to say, and you feel desperate to get away. These close links are made so fast that it can be hard to work out what happened first.

• Gemma’s biggest fear was that if others got to know her they wouldn’t like her. She was relatively comfortable with her immediate family, but she had never made close friends at school, and in her late thirties she still felt lonely and isolated.

• Tom was unable to do things if other people were watching. He found it hugely difficult to use his mobile phone when with his friends, or to fill in a form if someone was watching. He could not order a round of drinks in a quiet bar, or eat out comfortably in a restaurant.

• Ed found it excruciatingly embarrassing to talk to anyone whom he perceived to be physically attractive. He had not had any lasting close relationships by the time he asked his doctor for help when he was in his mid-forties.

• Kim was extremely successful at work as a solicitor, but found parties and informal gatherings impossibly difficult. James was the opposite. He could tell jokes and play around with people his own age, but became tense, anxious and self-conscious at work. He found it especially difficult to talk to anyone in authority, such as his boss.

• Joe found all social life a torture. He worked with computers and tried to prepare himself for meeting people during the lunch break by rehearsing things to talk about. He had been unable to accept promotion as this would involve speaking up in meetings, and organizing and reviewing the work of others.

Social phobia affects men and women roughly equally. It often starts around adolescence. Speaking in public, or speaking up in front of others, is the most common difficulty. Social phobia occurs all over the world, though the precise form that it takes varies from culture to culture. The things that will embarrass you, and make you feel that others are judging you negatively, will occur differently in different cultures. In some cultures it is acceptable to talk about money, or to make direct eye contact with someone of the opposite sex. In others, it is not. When socially phobic people feel anxious they (naturally) try to protect themselves from the disasters that they fear. The things that they do in these situations are called their safety behaviours (see Chapter 1). We all know that alcohol oils the wheels of social interaction, and socially anxious people can come to depend on it. When this happens, it makes sense to try to tackle both problems at once.

The vast majority of people all over the world go through a stage of being shy and most of us grow out of this during childhood. Many people feel shy at times all through their lives. They may be ‘slow to warm up’, but feel fine once they have got to know people. Feeling shy feels similar to social anxiety, and some people think of social phobia as an extreme form of shyness. The steps taken during treatment for social anxiety are also helpful for shy people, and it may not matter therefore which word you use to describe your problem. What matters is not whether you call it ‘social anxiety’ or ‘shyness’, but whether it causes you distress or interferes with doing what you want to do – if it doesn’t then that’s fine. But if it does, then it may be something that you want to change.

Tip for supporters

It is hard to overcome social phobia, and also hard to ask for help – especially for those with social anxiety! So encourage the person you are helping to talk about it. Remind them that it is worth trying to change even though it can be difficult. When they are ready, help them to think about the ways in which their social fears and worries cause them distress or interfere with their lives, and to identify as many aspects of their social anxiety as they can.

Thanks to the research of two clinical psychologists, David Clark and Adrian Wells, we now know that there are three aspects of social phobia that keep the problem going. These are:

• self-consciousness;

• patterns of thinking;

• safety behaviours.

So these are the things to focus on during treatment.

Of the four aspects of social phobia listed in the box on pp. 244–45, the effects on your body and your feelings are usually the things that socially anxious people notice most, and that they are most concerned by. So these are usually the things that people try to change by themselves, before they decide to ask for help. Knowing where to focus that effort instead, so as to work on self-consciousness, on the way we think, and on safety behaviours, makes all the difference.

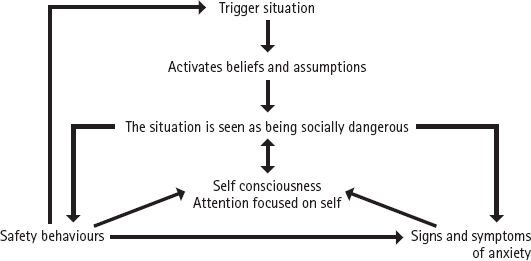

The new theory, supported by findings from research studies, is mapped out in the diagram below. The main aspects of social phobia are shown in the written parts of the diagram, and the cycles that keep the phobia going are shown by the arrows linking these aspects.

Figure 9.1: The Clark and Wells (1995) model of social phobia

If you look carefully at this diagram you will see that self-consciousness appears in the middle, at the bottom, and it is linked to everything else. The patterns of thinking are hidden in the beliefs and assumptions (‘I’m useless’; ‘you’ve got to be outgoing for people to like you’), and in the thoughts that make a social situation seem to be dangerous (‘this is horrible’, ‘I can’t think of anything to say’, ‘everyone’s looking at me’). The safety behaviours include all manner of ways of protecting ourselves when this happens – from keeping quiet for fear of saying something wrong, to chattering on and on so there aren’t any embarrassing silences. The signs and symptoms of anxiety are all the horrible things you feel – and no longer want to feel – when this happens.

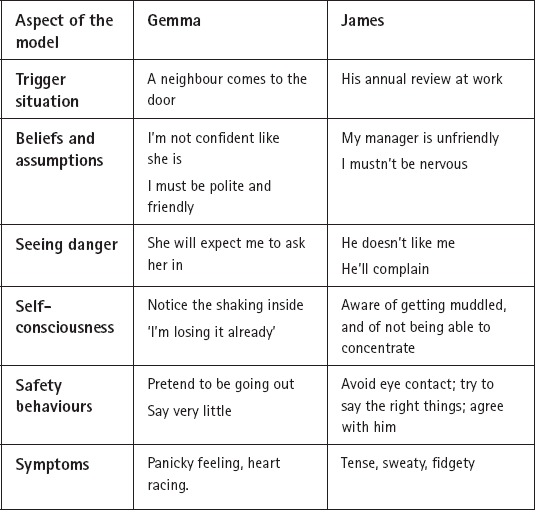

Some examples of the main elements in the model are shown in Table 9.1. Read through these and then fill in the blank table, starting with a recent example of one of the situations that you find difficult – a trigger situation for you. Later in the chapter we will ask you to put these into a diagram like the one on p. 248.

Table 9.1: Understanding social phobia

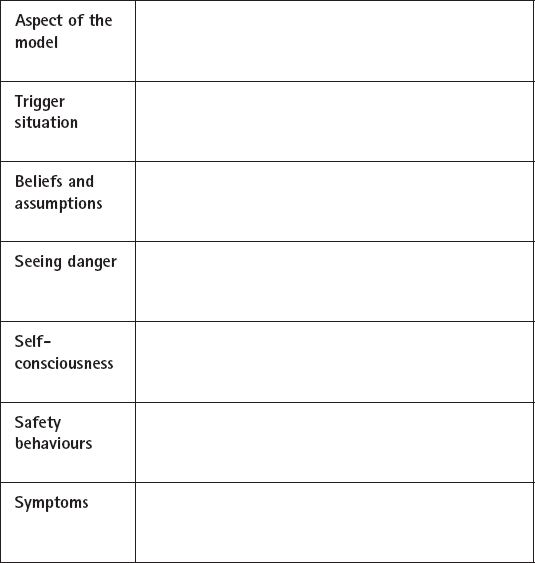

Here is a blank one for you to complete for yourself:

Table 9.2: Understanding your social phobia

Links between the main elements of the model on pp. 248, shown by the arrows in the diagram, help to explain why social phobia persists. The ways in which each of these main elements keep the problem going are described next. Use these descriptions to help you think of the ways in which these links work for you.

When anxious, socially phobic people focus in on themselves, self-consciousness fills up their minds, leaving little room for other things. So they find it hard to hear what others say, or to notice the expression on their faces. Instead they become painfully aware of themselves: of the sound of their own voice, or their feelings, or of what they think they are doing wrong – their shaking hands or muddled speech. That’s why they sometimes do exactly what they hope not to do, and knock over the coffee mug, or stumble over their words, or can’t think of anything to say. It is hard to pay full attention to what’s going on if we are constantly preoccupied with ourselves and our shortcomings. And of course these are what we remember later.

Self-consciousness comes from focusing our attention inwards, on ourselves, so that we become hyper-aware of what is going on inside us. It keeps the problem going because:

1. It inhibits our performance. When we are preoccupied with ourselves we may come across to others as distant or self-absorbed, or even as unfriendly or uninterested.

2. It prevents us picking up information about what is happening. There is no brain-space left for noticing important things, especially those things that can be read in people’s faces. So when we get positive responses from others we may not even notice.

3. It creates a vicious cycle. Being self-conscious makes us even more aware of what is going on in our mind and body. This makes the situation we are in feel even more dangerous, so that the desire to protect ourselves or keep ourselves safe also increases.

Patterns of thinking keep social phobia going because they set in motion vicious cycles of thoughts, feelings and behaviour. If we see a situation as socially dangerous we might think: ‘I don’t belong here. Nobody here really likes me.’ So we might feel sad and anxious, and find it hard to relax and to talk freely. Then the interaction we have becomes stilted or awkward, confirming our impression that we don’t really belong. Many of the ways people think are reflected in the predictions they make about social situations, even if they haven’t put those predictions into words. Here are some examples of common predictions:

• I won’t be able to keep the conversation going.

• They will see how nervous I am.

• I’ll do something stupid.

• No one will want to talk to me.

These negative predictions explain why social life feels so threatening, and why socially anxious people want to protect themselves by using safety behaviours. The more you protect yourself the harder it is to build your confidence, and this keeps the fears and anxious predictions going, too, in another vicious cycle.

Underlying the thoughts that make social situations seem dangerous and threatening are often more longstanding ways of thinking that many people never put into words. These are beliefs and assumptions, and they also create cycles that keep the problem going. A belief reflects fundamental attitudes, for example about oneself, ‘I’m different from others’; or about others, ‘people always judge me’ . . . negatively of course. Assumptions reflect the (unwritten) rules that people live by, and they fit with their beliefs. If we believe that we are fundamentally different from others we might assume that if we try to be like them, then they might like us. If we believe that people always judge us (negatively), then we might do our best to make sure that they never really get to know us, and go through life trying to hide our real selves from other people. But this sort of behaviour is likely to keep our anxiety going, and to strengthen the underlying beliefs and assumptions.

The natural thing to do if we are facing a threat, or a risk or a danger, is to try to keep ourselves safe. But if we protect ourselves we never get to find out that maybe the situation is not as dangerous as we thought it was, or to build our confidence. Once again, vicious cycles, as reflected in the arrows in the diagram on p. 248, keep the problem going. The box below shows some examples of how safety behaviours can keep social anxiety going.

Examples of how safety behaviours can keep social anxiety going

• You say little, so people you are talking to ignore you, and you feel left out and think they are rejecting you. Feeling rejected makes it feel only sensible to keep quiet next time, too.

• You know that when you are nervous your hands shake. But you don’t want people to notice this, so you tense them up, and hold your arms in tightly, to prevent them shaking. But tension makes it harder, not easier, to stop shaking. Besides, the effort to hide the shaking makes you self-conscious, and then you feel more, not less, nervous that others will notice your shaking.

• Many people who don’t want to attract attention to themselves speak quietly. But then those around them can’t hear what they are saying, and try harder to hear. They may come closer, or look at them carefully, or ask them to repeat what they just said. Again the attempt to keep safe backfired.

It makes sense to try to keep yourself safe if you feel anxious, or think that you are at risk of being rejected, embarrassed, or humiliated. The safety behaviours and avoidance link up with the feelings and thoughts, and all together they become like bad habits: they make the problem worse, not better. The way to make your social life feel safe is just like learning to feel safe in a swimming pool – to get in there and splash around, enjoy yourself and then learn to swim.

1. The post-mortem. Just as it sounds, this involves thinking about (dissecting) a social situation once it is over: something like a meal with friends, or a recent conversation. This is when all the things you think you did wrong come to mind, bringing embarrassment or even horror with them. The post-mortem is quite normal. It happens to all of us – when we cringe as a memory comes back to us, even if it’s the middle of the night. The trouble is that the post-mortem is no help to us at all. It comes with a delay, so prolongs the agony. It brings bad feelings with it all over again, and it adds feeling bad about ourselves to all the other bad feelings: ‘I’m hopeless . . . useless . . . completely unacceptable.’ The other problem with the post-mortem is that our memory is affected by our anxiety: we remember what we think happened, not what actually happened, and so we reinforce our negative views of ourselves in social situations.

If this happens to you, try to recognize it as unhelpful and turn your mind away from it. Distract yourself by doing something, or thinking about something interesting or pleasant instead.

2. Low confidence. If your social phobia has gone on a long time it is not surprising that it has undermined your confidence, or begun to do so. This makes it hard to do new things. The less you do the harder it is to remember that confidence comes from doing things and not worrying too much about the mistakes that you make along the way. It is impossible to learn without making mistakes. So try not to be held back by feeling unconfident. If you have a go, your confidence will start to build up in all sorts of ways, and working on your social phobia, especially as described in the section on Doing Things Differently pp. 278–80 is especially helpful in building social aspects of your confidence.

3. Feeling low and depressed. Social phobia gets people down. That is hardly surprising as it interferes with doing the things that you want to do, and with being the sort of person you would like to be, and know that you could be when with others. For this reason the last chapter of this book explains what to do if you are depressed as well as anxious. Our research has also shown that working to overcome their social phobia generally makes people less depressed as well. This is especially true if the social phobia began before they became depressed rather than the other way round.

First you will need to plan how you want to approach the work of overcoming your social phobia. The next step is to make sure you understand your social phobia: how it works and how it affects you personally. Assessing yourself, and setting your personal goals, comes next. Then you will be able to focus on the three central parts of the work:

1. Reducing self-consciousness: working to shift the focus of attention.

2. Changing thinking patterns: identifying and re-thinking your thoughts and expectations.

3. Doing things differently: devising experiments to find out what happens if you test out your expectations without using safety behaviours. Use the information that you pick up in your experiments to help you to re-think your old patterns of thinking.

Following these steps has an excellent chance of bringing about valuable and lasting change. They are described in the following two sections: ‘How to approach this self-help programme’ and ‘Treatment’.

It is probably best to read the whole chapter right through first, and then to go back to the beginning and work through it at your own pace. Working steadily, doing something every day if possible, is particularly helpful. You will need to set aside a regular time to work on your social phobia: ideally about an hour once a week and a much shorter time every day (or most days). This time is for planning the work and for thinking about how it is going.

Your first step should be to decide how you are going to keep track of the work that you do and how it goes. So get a special notebook, or make a new file on your computer. If you have a supporter, set aside times for regular meetings or conversations, and start these by deciding what to talk about, or ‘setting an agenda’. Each time, decide what your priorities are, and make sure that you always end the session with a clear understanding of the tasks that need to be completed before you talk next.

Tip for supporters

Read this chapter all the way through. Then ask the person you are helping when, and how frequently, they would like to talk to you about their efforts to change. Be guided by them. Think of yourself as helping to make specific plans about what to do, helping them to feel in charge of the work they are doing, so as to build their confidence. Encourage them to write down the reasons it is worth trying to change, and to make a list of the specific things that they would like to be able to do more easily. These are the goals for both of you to keep in mind.

You will use the main CBT methods as well as some special ones designed to tackle the unique features of social phobia: self-consciousness and concerns about how you are perceived by others. Self-consciousness is a natural human emotion that we all feel when we become aware of the scrutiny of others but when it is excessive it can seriously inhibit social performance and enjoyment of social interactions. CBT techniques can help you to learn what you can do to reduce this self-consciousness.

CBT will also help you to become less concerned about how you think you are coming across to others – about what you think they are thinking about you. Mostly, when something scares you, the fear dies away when you face your fears. But in social phobia this seems not to happen. Most sufferers have already, to a greater or lesser extent, confronted the source of their phobia – other people – on a daily basis. It is after all, impossible to avoid them. But facing others appears not to reduce the fear of meeting them or interacting with them. This is because the underlying fear is about what others are thinking about you, which you often can’t know for certain, as it comes from a kind of guesswork. In tackling your social anxiety you will discover how to approach situations that you would normally avoid, and how to find out what you need to know once you are in them.

Start by thinking about why exactly you want to change. Try to be clear with yourself, as this helps you to keep in mind why overcoming the problem is important. For example, Shireen was prompted to tackle her social anxiety when she noticed her children were learning to do some of the same things and seemed to be ‘catching’ her social anxiety. Gemma realized that her biological clock was ticking and unless she was able to socialize outside her immediate family she might not be able to find a lasting relationship or to have children of her own. James was prompted to seek help when he took on a new role at work that meant he had to engage in more formal business situations. He felt that he was ‘too old’ to still be so shy.

In your notebook or on your computer, write down the main reasons why it is important to you to be less socially anxious. Make sure you can find your notes easily so you can refer back to them if at times it seems like a struggle to persevere. Even if all goes smoothly there are likely to be times when it is easier to rely on old habits than to push yourself to face situations you instinctively avoid.

It is helpful to get an idea of how severe your social anxiety is at the moment, as this will help you to measure your progress as you start to make changes. There are some self-report measures that are freely available for this purpose, which you can access on the internet. One of these is the Social Phobia Rating Scale (SPRS) which can be downloaded from: www.goodmedicine.org.uk/stressedtozest/2008/11/handouts-questionnaires-social-anxiety and is included in the Appendices. Fill this in before you start, and do it regularly during treatment. You can decide how often: for example you could do it weekly, or monthly, or before each meeting with your supporter.

Next think about exactly what you want to achieve. These aims can then be refined into Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Timely (SMART) goals. In setting your personal goals for overcoming your social anxiety, questions to ask yourself will include:

• What exactly do I want to be able to do differently?

° In what circumstances? With whom? When? How often?

• How will I know when I can do that?

° What might others notice is different about me?

° How would I know it was different?

• How do I want to feel differently?

° What is it realistic to expect?

° How will I know if I do feel that way?

Tom worried about his hands shaking noticeably in front of others. His goals for treatment focused on being able to do things that he currently avoided:

• Complete a form in front of other people, e.g., in the post office.

• Use his mobile phone on the bus or in the street, then with groups of friends.

• Eat in a nearby café, and then in other restaurants.

• Order beer in a bar (he currently chose drinks that were not filled to the top of the glass) and carry it to a table.

• Be able to concentrate on speaking to another person while his hands were on show.

Goals will often focus on helping you to engage in situations that you have previously avoided, but they may also be about what you do in such situations.

Gemma wanted to be more open with people and to express her opinions even if she thought others wouldn’t share them. Her goals were to begin doing this with those she felt most secure with (close family and friends) then work up to the scarier situations – with more casual acquaintances and then in more public or formal ones such as complaining about poor service in a restaurant, or returning something to a shop. In particular, she wanted to stop preparing for conversations by rehearsing what she could ask the person about, and instead just talk about whatever came up.

Ed specifically wanted to stop avoiding certain people that he feared would trigger his blushing (people that he found attractive). Ideally he would have liked to be able to engage such people in conversation without any fear of blushing, but thought that a more realistic goal was to be able to talk to the person irrespective of whether he blushed.

It is unlikely that you will ever be totally free of any social anxiety or self-consciousness at all (and it wouldn’t be desirable to be completely immune to the opinions of others), but what exactly would you like to be able to do?

Tip for supporters

You could help the person you are supporting to make a list of their goals – help them to identify why it is important to them to tackle their social anxiety, what benefits it would bring and what they might reasonably expect to be different once they have had a go at overcoming social anxiety.

It can be hard to work out exactly what is keeping your social phobia going, so it is a good idea to set some time aside and find a quiet place to sit down and do this. The aim is to work out your underlying fears and to be able to pinpoint the various ways in which you try to protect yourself, or the safety behaviours linked to your fears.

A useful first stage is to draft your own version of Clark and Wells’s model of social phobia (see Figure 9.1). Earlier (p. 249) we asked you to work out the main elements of the model starting from a specific difficult situation. Now the task is to fill in the blank boxes in the diagram below. Some questions have been added on the table to help you to identify what might be relevant in those boxes, and a blank flow chart has been provided in the Appendix. The boxes and questions are numbered as a rough guide to the order but you might prefer to complete them in a different order.

Now you can use the information you have collected to work out how the different aspects of the problem link together for you. Think about how your thoughts influence your feelings, physiology and behaviour; about how your behaviour links back to the way you think about yourself; how self-consciousness affects what you do and what you think and so on. This work can give you some clues about what you should do to bring about change. What most people who experience excessive social anxiety want is to feel better, to feel less anxious and experience fewer physiological symptoms of anxiety. But as it is difficult to change feelings directly, it is more useful to look instead at the things that lead to the feelings: the self-consciousness, thoughts and safety behaviours.

Tip for supporters

You could have a go at this, too – then compare notes to see if you can add anything to each other’s versions.

Once you understand more about what keeps your problem going you will be ready to use the strategies for changing some of those things. The priorities are listed in the box below.

Priorities for change

• Reducing self-consciousness: The main strategy is to learn to focus outside yourself so that you are no longer constantly aware of what is going on inside – or self-consciousness. This means practising paying attention to what is going on in the situation you are in, to other people, to what they are saying or doing and so on.

• Changing thinking patterns: This involves thinking again about the thoughts, predictions and assumptions that are linked with fear and anxiety and learning how to re-think these things.

• Doing things differently: Planning experiments will help you to do things in new ways and to work out what this tells you about yourself and about other people.

The next stage of treatment is to learn about and to practise the strategies and techniques that will help you to feel less socially anxious. The three main aspects of treatment are described separately on pp. 255–85, as you should do them in that order. Indeed this could be useful, especially when you are learning about exactly what to do. Once you know about all three you will be able to combine the methods. For example you might experiment with talking to some people who make you feel nervous; practise paying attention to them and to their feelings while you are talking, and think afterwards about whether you were right to expect that they would reject you. Learning how to do each of these things is described next.

The aim is to learn to forget yourself in order to be yourself, just as you would if you were running downstairs. If you tried to tell yourself exactly how to do this you would probably trip over, as too much self-awareness interferes with performance. So what you are going to practise is switching your attention. Learning to focus externally is not a new skill – you probably do it all the time, for example when you lose yourself in a film, book or piece of music, and fail to notice what else is going on around you; or when you are so engrossed in answering your emails that you don’t notice the television in the background any more. So you should practise giving more attention to the person or people that you are interacting with. Eventually this will enable you to become more fluent and attentive, and to feel more comfortable.

Focusing externally is a big effort at first, but over time it should become habit. The first thing to practise is switching attention from internal to external, and back again, in non-threatening situations. For example, you could do this while watching television, or on the bus, or walking the dog. First pay attention to what is going on in your body (focusing internally), and then switch your attention to what is going on around you (focusing externally). When inwardly focused you are paying attention to how your body feels on the inside, and what is going on in your mind: noticing how hot you feel or worrying about how you are coming across. When you are externally focused you will notice what you can see, hear, smell and feel around you, such as the colours in the sky, wind on your face, and feel of the ground under your feet as you walk the dog, or exactly what is happening in a television programme as you watch it. Notice the contrast between the two kinds of attention: being involved with a television programme as opposed to noticing that you feel hungry, or worried about something, or annoyed with someone else.

Some useful points to remember about attention switching:

• Attention naturally wanders, as things around you grab your attention. So you will not be able to keep it fixed in one place. Don’t worry about that, and just turn it outwards again if you notice yourself becoming self-conscious.

• In an un-self-conscious conversation, as you probably know, attention naturally moves between other people, the things around you, and your own feelings and ideas. So don’t try to fix on something, like the other person’s face. Let your attention wander about, and move it outwards if you notice your signs and symptoms of anxiety.

• The more interested and curious you are the more you will pay attention to what you are talking about, and to other people, and the less attention will be left over for your anxiety and worrying thoughts. So give yourself something to find out from the other person, or talk about something that really interests you.

One strong motivator for focusing internally in social situations is the perceived need to monitor how you feel in order to estimate how (badly) you are coming across. But self-perceptions of this kind are terribly inaccurate – you do not appear how you feel. People cannot see how you feel – if they could you wouldn’t have to explain it to them. You will get a much better sense of how you are coming across by focusing externally and by finding out more about other people – collecting the kind of information that passes you by when self-consciousness dominates. This helps you to notice, for instance, that not everyone is staring at you even when it feels as if they are, or that the person that you are speaking to is enjoying the conversation.

First practise switching your attention in non-threatening situations and then try doing it in social situations. Start with relatively easy ones, such as speaking to people you feel relatively comfortable with, then move on to more threatening situations. If you find yourself becoming self-conscious try not to worry about it, and just move your attention outwards once more. Practising switching your attention back and forth will make this easier to do.

You might find it helpful to compare the effects of being internally or externally focused in social situations – so try a few minutes’ conversation each way and see which you think makes you (i) feel more comfortable and (ii) perform better in the situation.

Tip for supporters

You can help the person you are supporting ‘compare and contrast’ the effects of being internally or externally focused. Get them to practise a pretend social situation with you, e.g. having a chat over coffee for five minutes. Ideally it would be a situation that will make them a little anxious. For the first role-play ask them to focus on themselves, and in particular on what is going on inside their body and mind, as much as possible. In contrast, in the second one ask them to try to focus externally – on you and the conversation. Immediately after each conversation ask them to rate, from 0–10, how anxious they felt, how anxious they think they looked, and how well they think they came across. This will enable them to compare directly the effects of focusing internally to externally. You could also give them feedback as to how they came across in each version.

In this section you will learn how to re-think the patterns of thinking that otherwise contribute to keeping your social phobia going. These patterns include your expectations, predictions, assumptions and beliefs, and these will be different for different people. Gemma thought that if she revealed her true self to people they would reject her for being boring and dull. Tom’s concerns centred on his assumption that people would know how anxious he was, and think him odd if they saw his hands shaking. Ed worried that he might blush when speaking to someone he found attractive, and that the person would then think he was coming on to them and think him a sad old letch. Kim knew that she was unable to make small talk and believed that others found her dull and uninteresting. James usually felt OK in informal social situations but struggled at work or when speaking to people in authority as he believed he was not bright enough to be doing this job, and assumed they would discover how stupid he was. Joe, whose social anxiety affected all situations, believed that he would be revealed as generally inadequate in every way, whatever he did.

Having negative predictions in mind drives the anxious feelings. If you think that you are coming across as a total idiot, and think that others can see how anxious you feel inside it makes perfect sense that you feel anxious. Thus an obvious way forward is to use CBT techniques to help recognize your patterns of thinking, and then to examine the validity and helpfulness of these thoughts and predictions.

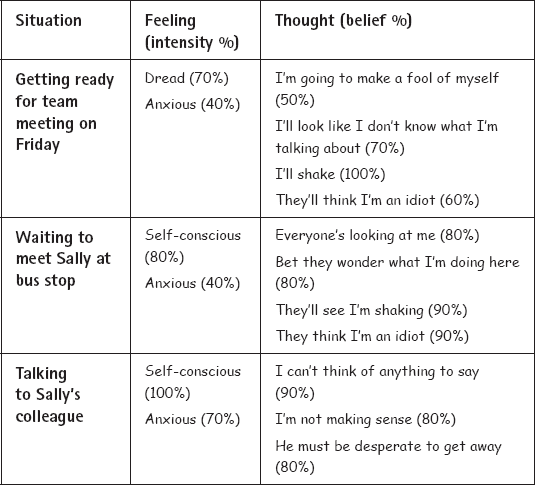

The first stage is to tune in to exactly what you are saying to yourself in social situations. When you notice yourself becoming anxious stop and ask yourself, ‘What is it I am most bothered about? What is the worst that I am fearing could happen?’ It is useful to keep a chart like the one below to keep a record of your thoughts.

Table 9.3: Social phobia thought record

Tips for supporters

You can help by putting questions to the person you are supporting when they are beginning to get anxious about a social situation. The following list of questions might be useful in helping them to identify clearly what they are thinking:

• What is going through your mind right now?

• Is there something that you are predicting will go wrong?

• What’s the worst that could happen in this situation?

• Is there a particular symptom or symptoms that you are worried about other people seeing?

• Do you have any image or impression of how you are likely to come across?

Once you have tuned in to what you are thinking, the next step is to begin to examine the validity and helpfulness of these thoughts. Thoughts are our opinions, not necessarily facts. When we are anxious our thinking often becomes distorted, and overly black and white. We tend to make negative predictions about how we are coming across that may not be justified. So when I feel as if I am blushing, I may think I have gone bright red, and that everyone has noticed and thinks I am an idiot but this isn’t necessarily the case. Firstly, I may not look as red as I feel and, secondly, even if I have gone red, others may not be paying attention to that, or may view it much less harshly than I imagine.

There are many ways of re-thinking old patterns of thinking. The one described next uses an expanded version of the chart above, and the work is done by re-thinking old habits of thought, either by yourself or with the help of someone else. Another way, described in the next section, is to experiment with new ways of doing things so that you can collect some new information relevant to the kinds of situations that trouble you.

In order to examine the validity of socially anxious thoughts you need to examine the evidence for them, and the extra columns added to the chart on pp. 272–3 help us to do this. First, decide which of the thoughts to evaluate – the one that bothers you most is likely to be most useful and this thought has been emboldened in the chart. Then start to look for the evidence that supports this thought. When you have found all you can, turn your attention to the evidence that does not support this thought. With both kinds of evidence in front of you think them through and see if you can come up with a realistic, and balanced conclusion. Finally, think about how to take the issue forward. You might even be able to make a definite plan of action.

Tips for supporters

You can help at all stages. In particular by helping them to:

• Be specific about exactly what they are predicting in a given social situation.

• Find any evidence that does not fit with their negative predictions or beliefs.

• Make a plan of action for what to do differently in the light of any changes in their thinking about a particular situation.

Try to complete thought records when the issue is ‘live’: as soon as possible after something that made you anxious. It gets harder to ‘catch’ the thoughts the longer it is since the situation happened. At first, completing thought records as shown above may seem laborious and inconvenient. Like any skill it requires practice, and it helps to write things out in full until you feel you have got the hang of it. Your helper, if you have one, may be able to assist with particularly tricky thoughts, or when you are struggling to find anything that does not fit with the thought. Over time you should be able to spot repeating patterns in your thinking and thought records, and it will get easier as you will have addressed that type of thought many times before. With practice you will get better at thinking things through in this way in your head and may only need to write down the most difficult issues. An example is given on the next page, and a blank form for you to complete follows, and is in the appendix.

The following four themes are such common ones that it helps to be aware of them as you start this aspect of the work.

1. Taking too much responsibility. People with social anxiety often take 100 per cent of the responsibility for how any social interaction goes. If it doesn’t go well they assume it is their fault, and that they messed it up. It is worth remembering that you only ever share the responsibility for a social interaction – if it doesn’t go well maybe it is because the other person isn’t very easy to talk to! Or because they have something else on their mind at the moment that is distracting them. Or perhaps you just don’t have a lot in common. Or is it the situation that is difficult? People with social anxiety tend to blame any social failure on themselves while really responsibility is shared.

2. Emotional reasoning. This means using your feelings as evidence of how you are coming across. It happens because when socially anxious we become hyperaware of what is going on in our body, and much less aware of what is going on around us. This influences the judgements about how it is going because the main thing the socially anxious person is aware of is their own feelings of anxiety. It is natural to assume that this is what dominated the situation for others, too, but it isn’t. People with social anxiety often feel that their anxiety is completely obvious to others, but it isn’t. Other people can’t see your feelings – if they could no one would ever have to ask how you are because they’d be able to tell from looking. Just like people can’t tell if you are hungry or thirsty from just looking at you, they can’t tell how you are feeling. They may be able to make a guess on the basis of what you do, if you laugh or cry for instance, but it will still be a guess. We all learn to behave in ways that disguise our feelings. Switching your attention outside of yourself will help you to be less hyperaware of your anxiety and be better able to observe how other people behave and react. Then you can draw conclusions based on what is happening in the social situation and the interaction with the other person, rather than on how you feel inside.

3. Overly high standards for social performance. People with social anxiety often have very high standards for their own social performance, such as feeling that they should be fluent and interesting all the time, or that it is totally unacceptable to forget what one was saying, and to dry up in the middle of a conversation. In reality all these things are common. Conversations often meander around, or become repetitive and stilted. It is worth paying attention to the times when other people make these ‘social mistakes’ and observing how they are responded to. For example, if someone repeats themselves, or forgets what they were saying, does anyone really seem bothered by it?

4. Believing you are boring, unlikeable or uninteresting. People with social anxiety may believe that they are socially unattractive, for a variety of reasons, such as not being interesting or witty enough. However, it is worth remembering that acceptability is much more to do with the match between two people, and whether they like each other, than with the characteristics of either of them. There will always be people that you don’t like, or have a lot in common with, and others will feel the same about you. This doesn’t make you boring or unlikeable; it just means that you are not well suited to each other. If you are not interested in golf, then you may find the conversation boring, but other golfers won’t. Indeed, the people most likely to be experienced as boring by others are those who don’t show any interest in the other person, and just bang on about whatever it is they want to talk about, and this is far from what most people with social anxiety do!

You might be able to help the person spot themes in their thought records:

• Do they seem to be taking too much responsibility for social interactions?

• Are they basing their conclusions about social situations solely on how they felt in the situation?

• Do they seem to have very high standards for their own social performance?

• Do they seem to be consistently overly critical of themselves?

There is no way round it: the way to build confidence is to face the things that you fear. In this section you will learn how to stop doing the things that feel as if they will protect you: avoiding difficult situations and keeping yourself safe. These behaviours contribute to keeping the problem going. Instead you will discover how to do things differently by planning some mini-experiments. First you will need to identify your personal self-protection strategies: what you avoid and how you try to keep yourself safe. Then you can use this information to plan some experiments, to test out some of your fears. Thinking the experiments through, before and after you have done them, brings the three parts of the treatment together by linking the new behaviours to new ways of thinking.

Start by thinking about, and trying to recognize, the ways in which you try to protect yourself. Avoidance is not doing something because it would make you anxious. Safety behaviours involve doing something to make you feel less anxious. They both work in the same way, and both of them keep the problem going, so make as long a list as you can of all these things. Prompt yourself by answering the questions below.

Avoidance: not doing something that would make you anxious

1. What social events do you avoid going to?

2. What social interactions would you never join in with?

3. Are there times when you make excuses or find a way of making your escape? If so, when does this happen?

4. Do you refuse invitations? Which sorts of invitations?

Some examples of avoidance: saying no to social invitations, arriving late or leaving early to limit the time; refusing to try new things or places because of fear of embarrassment; not speaking in front of others; staying away from certain people or situations; avoiding speaking to someone you find attractive.

Safety behaviours: doing something to protect yourself

1. What do you do that makes anxiety-provoking situations feel safer?

2. How do you try to make sure that nothing too bad happens?

3. Are there ways in which you try not to attract attention?

4. Do you do anything in social situations to try to prevent yourself coming across badly? Or to prevent others from noticing?

Some examples of safety behaviours: looking down so no one can catch your eye or see your face; not wearing bright-coloured clothing, or clothes that make you feel hot; being careful about what you say; handing stuff round at a party so you can move on easily; taking a friend with you if you feel too nervous on your own.

Avoidance and safety behaviours often overlap. For instance, you might avoid speaking up in front of a group, or keep yourself safe by saying very little. The important point is to be aware of both of these ways of protecting yourself. They can both be tackled using mini-experiments to test out the consequences of behaving differently.

Gemma didn’t avoid conversations but she avoided expressing her true opinions in those conversations for fear that it would make people dislike her. Her new boyfriend had noticed that she always made sure she was behind him if they ever entered a bar or restaurant, and she would make sure she did not arrive before he did by waiting in her car nearby until he texted her. Tom didn’t avoid going to the pub with friends, but his main safety behaviour involved keeping his hands out of view so people wouldn’t notice if they were shaking. Ed was aware that he tended to avoid eye contact when talking to anyone he found attractive. He also tried to keep himself cool to limit any blushing and sweating. So avoidance is not just about avoiding going into the situations, but also about what you do once you are there, for example, for Tom, carrying a round of drinks from the bar, and for Gemma, expressing opinions, especially disagreement.

Tip for supporters

You can help the person you are supporting to draw up a list of the self-protective strategies that they use. You might be able to spot things that they hadn’t even noticed themselves – situations they are avoiding or the subtle things they do to protect themselves in those situations. Encourage them to begin to change these behaviours by reminding them that facing fears helps to build confidence.

Once you begin going into social situations that you have previously avoided it is important that you get the most out of them. To do this you can treat each time as an experiment – a chance to discover how realistic your social fears are, or to discover what happens if you behave differently in the situation. So it is important to think in advance about how you will get the information to answer your questions. So for Tom, whose primary concern was that others would notice his hands shaking, it was important to work out how he would know if they did notice his hands shaking. Tom was confident that if the friends whom he went to the pub with noticed his shaking, they would comment. So when he went to the pub and reduced his avoidance by ordering drinks that were full to the top and carrying them back from the bar, he paid attention to whether anyone commented on his shaking. He was even able to ask one of his closest friends if they had noticed anything.

Similarly for Ed, who was concerned about blushing if he had to speak to someone attractive, it was important to be able to tell if he had blushed, and what, if anything, the other person had made of it. How would he know if they did indeed think he was a ‘sad old letch’ as he feared? He thought that if a girl had noticed his blushing and thought him a sad old letch, then she would make every effort to end the conversation as soon as possible. So he used this to judge whether his fears were being realized or not. In this way it is possible to treat every situation as an ‘experiment’, helping you to discover more about your social anxiety, and about how you actually are coming across. No single experiment will fundamentally change your perception, but each one is like a pebble on the beach, and over time the pebbles accumulate to change the shape of the beach – in this case to change your thoughts and feelings about how you come across to others. For this reason it is important to keep detailed notes of the outcomes of your experiments (See Chapter 5, p. 62–7, for behavioural experiments and worksheet). These are used to record (i) what you feared in advance of the situation, (ii) what you did to test that fear, (iii) what the outcome was and (iv) what you concluded from it.

Tip for supporters

You can help the person you are supporting to identify what it is they fear most about the situation, and by devising a way of testing that within the situation. You may even be able to collect ‘data’ for them – for example by monitoring and observing how other people react to them in social situations.

Experiments take the sting out of facing your fears. The whole point of them is to find out something you want to know. That means that as well as being anxious or nervous about doing them you soon become interested in what you are going to discover, or curious about what you will find out.

For instance, many people avoid talking about social anxiety for fear of what other people might think of them. But a degree of social anxiety is natural so everyone knows how it feels. An early experiment you might start with is to ask one or two people that you know if they ever get anxious in social situations, such as when speaking up in public, or when meeting new people. If they say yes, then ask how it affects them. What do they worry about? How do they make sense of their anxiety in that situation? Once you have a few findings, stop and think about them. What did they say? Did their fears seem realistic?

And what does it tell you about the normality of social anxiety? Think, too, about how you felt while collecting this information? Were you as anxious as you expected to be?

This is an important point. Making a prediction before you try doing something new helps you to collect a lot more information than you might otherwise be able to. The steps to go through when you are planning these are:

1. Identify what you do to protect yourself.

2. Find out what happens if you give up protecting yourself in this way by making a specific prediction about what will happen if you don’t do it (or even do the opposite).

3. Draw conclusions from what you have done.

Gemma’s main fear was that people wouldn’t like her if they got to know her. So to protect herself she always avoided talking about herself, and expressing her opinions. So one of her main experiments was to go into social situations and talk about herself, and express her opinions. She tried this out by going into work on a Monday morning and instead of just saying ‘yes, thanks’ when colleagues asked if she had a nice weekend, she actually told them about her weekend. She predicted that they would quickly lose interest and would not ask about her weekend again. What she found was quite the opposite – most people seemed genuinely interested in what she had been up to and she discovered common interests with some of her colleagues, which made it much easier to talk to them in other situations, too.

Doing experiments like this made it easier for her to develop confidence and drop other safety behaviours, such as always making sure her husband was with her or entered a social situation first. She had predicted that if she met her boyfriend in the pub, and arrived first, everyone in the pub would stare at her as she came in and think she was some kind of weirdo. To begin to test this out first she went to a pub with her husband and just observed whether other people were on their own, and if they seemed to be the focus of other people’s attention. What she found was that plenty of people were on their own, particularly early in the evening. Some appeared to be waiting for someone, and others didn’t. Noticing this helped to plan her next experiment – going into the pub to wait for her husband by herself. What she discovered was that no one paid her any attention.

In contrast, Tom was fine about going to the pub, but it was what he did when he was there that he needed to experiment with. He predicted that his friends would notice his hands shaking if he carried full drinks back from the bar and that they would realize how anxious he was and make fun of him for it. What he found out was that in fact all they did was complain about how long it had taken him to get served!

Sometimes it isn’t possible to know what others are thinking, or how they view something simply by observing their reactions. So it can be useful to ask them. For example, Ed was concerned that if people noticed he was blushing they would think he was a ‘sad old letch’ or at the least lying to them. Before he even put himself in the situation it seemed important to find out more about what people generally thought when they noticed someone blush; so he asked a female friend what she would think if, when she was talking to a man of a similar age to herself, he started to blush. Would she necessarily think he was lying or coming on to her? He was surprised to discover that she would only have thought that maybe he was hot or self-conscious. However, this was only one person’s view so he needed to ask a few more people to get a sense of how people generally viewed blushing.

Once Ed discovered that people didn’t automatically conclude that you were coming on to them, or lying, if you happened to blush when you were speaking to them, it was easier for him to begin to tackle the list of situations that he avoided, and to ensure that he wasn’t avoiding aspects of those situations, such as speaking to women he perceived to be attractive, or avoiding showing his face when speaking.

Gemma was concerned what people would think of her if she went into a pub on her own. To find out more before doing the experiments above she asked a few female friends if they ever went into pubs on their own, even just to wait for someone. She was surprised by the range of responses – one friend who travelled a lot with work was used to going to pubs and restaurants on her own and felt no anxiety about it. Others did go into pubs on their own but some of Gemma’s friends also said that it made them slightly anxious, particularly at first. And one even used Gemma’s tactic of always waiting outside.

Tip for supporters

You can help the person you are supporting to construct and carry out surveys by helping them to identify what it is they need to find out in relation to their social concerns. Once you have identified which questions to ask, the sufferer may have a limited pool of people to ask, or be too embarrassed to ask people, so you may be able to extend this by asking your acquaintances their opinions – either face to face or via an email survey. An advantage of an email survey is that the responses can be passed on to the person you are supporting directly so they get the full range of other people’s views.

Because social anxiety is such a usual phenomenon you can’t expect to ever reach a place where you don’t ever feel it again. What you are aiming for is to be able to enjoy doing the things you want to be able to do without being distressed by worries about how you come across, or being overwhelmed by the physical sensations of anxiety. This is the same as with the other anxiety disorders, and techniques to address it are found in Chapter 6.

It is important to remember that social anxiety is usual, so you shouldn’t expect to ever be completely free from any social anxiety whatsoever. What we hope is that the techniques outlined in this chapter have helped you to get your social anxiety to a manageable level – so it no longer stops you from living the life you want to live or causes you significant distress. We hope that learning about what keeps social anxiety going – the thoughts, self-consciousness and self-protective behaviours – has helped you to understand how social anxiety escalates. And that learning what to do about it has helped you to change your thinking, reduce your feelings of self-consciousness and experiment with behaving differently in social situations. Just as these different components combine to create vicious cycles that escalate anxiety, they can be used to create ‘virtuous cycles’ to reduce anxiety. Being less self-conscious helps you to notice positive feedback from others and engage in the situation, which gives you the confidence to test out your predictions and behave differently. So the key task in the future is to continue to use the techniques so you can keep the cycles turning in the virtuous direction. And to remember that some social anxiety is usual and even useful!