Chapter 13

Groovin’ in a Genre: It's All About Style!

In This Chapter

Exploring different ways to play a song

Exploring different ways to play a song

Knowing when to blend (or not)

Knowing when to blend (or not)

Access the audio tracks and video clips at www.dummies.com/go/bassguitar

Access the audio tracks and video clips at www.dummies.com/go/bassguitar

Imagine that you're invited to a luau, and on the big day you show up in shorts and a colorful T-shirt with a big lei around your neck. Seems appropriate enough, right? However, as you enter the party, you catch a glimpse of all the other guests wearing their finest tuxedos and ball gowns. It turns out that your expected poolside BBQ is actually a formal dinner party. You stick out like a fresh ink stain on a wedding dress; you certainly won't blend in with this crowd.

Music genres (jazz, world beat, rock, and so on) work on the same premise — certain elements in each groove indicate which genre you're playing in. If you play your groove in the wrong genre — a funk groove in a country tune, for example — prepare to audition for a new gig. But if you master a few basic grooves for each genre and learn to use the appropriate one for your band's interpretation of a tune, get ready to dump your day job for a lucrative career as an in-demand bass player. In this chapter, I demonstrate the simple but crucial steps you can take to ensure that you're always in style, no matter what genre you're asked to play in.

Playing Grooves in Each Genre: One Simple Song, Many Genres Strong

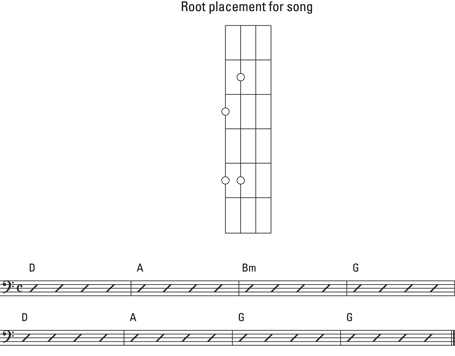

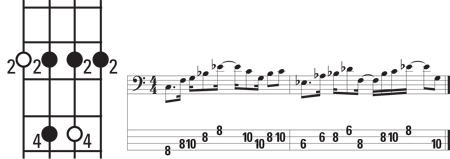

The song in Figure 13-1 uses a standard chord progression that's a common sequence in many tunes. You can find this exact same chord sequence, or large portions of it, in plenty of songs in different genres, from pop to shuffle. I use this same chord progression in every example throughout this chapter, but each rendition of it sounds distinctly different, depending on the genre of groove being played over it.

Note: I don't include country and world beat as individual genres in this section because they're technically part of pop and Latin, respectively. I also don't include jazz because traditionally it doesn't groove (it most likely walks).

Figure 13-1: Song notation with standard progression.

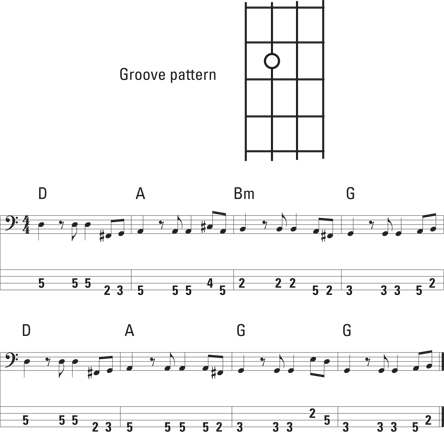

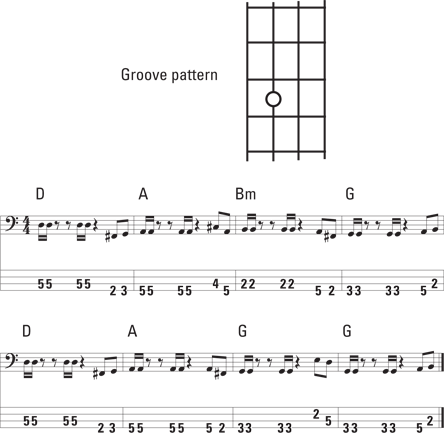

Pop: Backing up the singer-songwriter

Playing space (playing sparingly) is the name of the game when you're performing in the pop genre. A simple, uncluttered accompaniment (the bass line you play to support a soloist) is your best choice. Most important is the groove skeleton (see Chapter 6 for a thorough discussion of the groove skeleton). The two notes making up the groove skeleton are hit on beat 1 and on the and of beat 2 (Chapter 4 provides an explanation on how to count the different parts of a beat). All the other notes of the groove fall on eighth notes and lead smoothly to the next chord in the progression.

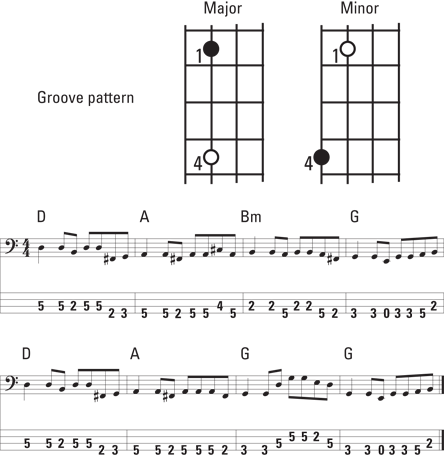

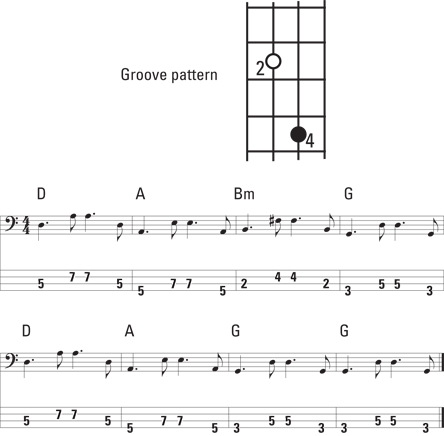

Rocking by the quarter or eighth note

Playing this chapter's standard progression in the rock genre requires some minor changes, but they yield major results. In Track 99, listen to how the same song transforms instantly when you play your groove skeleton right on beats 1 and 2. The same song, at the same tempo, with the same progression all of a sudden has much more of a punch to it — it has a rock sound. The notes after the groove skeleton are eighth notes and lead to the next chord in the progression. Figure 13-3 shows the rock bass part to this song. Get your rockin’ attitude ready and play along with Track 99.

Figure 13-2: A bass part in the pop genre.

You can add some urgency to the rock genre by playing a groove skeleton that includes notes on beat 1 and on the and of 1, making this an eighth-note rock. All the other notes stay pretty much the same as in the quarter-note rock. Keep your hand in position; no shifting is required (or desired).

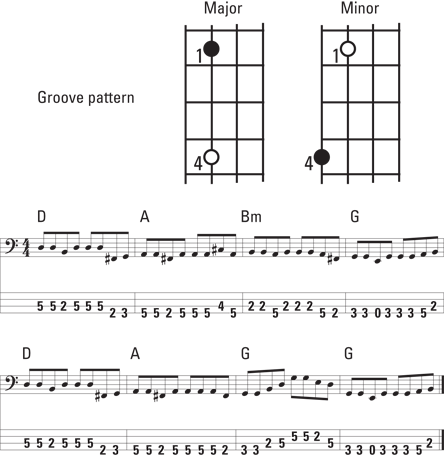

R & B/Soul, with or without the dot

In the R & B/Soul genre, things get a bit funkier. Two different groove skeletons are used most commonly to evoke this genre. One is the same as the eighth-note rock genre, in which the notes are played on beat 1 and on the and of 1.

Figure 13-3: Rock bass part with a quarter-note groove skeleton.

Figure 13-4: Rock bass part with a groove skeleton that uses two eighth notes.

Adding a dot to the first note of the R & B/Soul groove skeleton (see Chapter 4 for an explanation of the dot) is an even clearer indication that you're about to enter Soul City. Your groove skeleton is now on beat 1 and the a of 1. In addition, your follow-up notes, including the groove apex, are still in the sixteenth-note rhythms of e and a. It's hard to believe you're still playing the same old tune at the beginning of this chapter, isn't it?

Figure 13-5: R & B/Soul bass part with a groove skeleton that uses two eighth notes.

Make sure you play the rhythm of the first two notes cleanly and crisply; it's a very particular feel that's not easy to catch right away. The trick is to make sure you complete this rhythmic phrase directly before beat 2 comes around.

Figure 13-6: R & B/Soul bass part with a groove skeleton that uses a dotted eighth note and a sixteenth note.

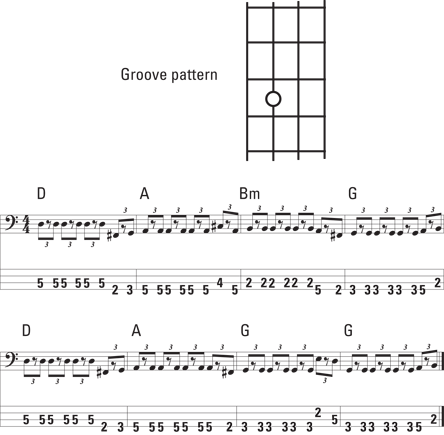

Feeling da funk

Bring on da funk! It's time to really get down. Funk is a genre that can be busy or sparse, but it's most definitely performed with a sixteenth-note feel. Signaling a funk groove with two sixteenth notes upfront as your groove skeleton leaves no doubt in anyone's mind that your intentions are . . . funky! The notes following the groove skeleton are placed onto the e and a of any of the beats in the sixteenth-note rhythms. Keep your notes short and crisp — no lingering allowed.

Figure 13-7: Funk bass part with a groove skeleton that uses two sixteenth notes.

Layin’ down some Latin grooves

Latin bass parts are one of the most easily recognizable musical figures in world beat and you won't have trouble finding people to play with. The standard Latin groove is a predictable root-5 pattern, as shown in Figure 13-8 (for more on roots and 5ths, check out Chapter 2).

Figure 13-8: Latin bass groove.

Be sure to leave lots of space in your groove for the two dozen percussionists who want to play with you on the Latin stuff.

When you're feelin’ blue, shuffle

The shuffle genre is most often expressed in the blues style. With only three subdivisions per beat (triplets) instead of four (sixteenth notes), the shuffle has a much more relaxed feel than, say, funk style.

You can instantly recognize a shuffle by its lopsided feel — each beat is subdivided into three equal parts: The first two parts of the first beat are assigned to the first note you play, and the third part of the beat is assigned to the second note. The resulting rhythm is long, short, long, short, and so on (sort of like a drunkard limping back to his room after a bar brawl).

Figure 13-9: Shuffle bass part.

To Blend or Not to Blend: Knowing How to Fit In

Blending a bass line means choosing the notes you play so they support the song perfectly without being overly noticeable. It's almost like the hidden beams in the ceiling of a modern house — you don't see them, but if they weren't there, the roof would collapse.

A bold groove, on the other hand, has a much more obvious role in a tune. It's more akin to the exposed beams of an old colonial house. They, too, serve to hold up the roof, but they're obvious and also ornamental; they're a major part of the aesthetics.

- Blending grooves: You use a blending groove when you're playing a supportive role in a song, when you're trying to stay out of the way of the vocals or a melody instrument, or when you're just not all that familiar with the particular song (or musicians you're playing with).

Think of the song “Soul Man” (either the version by Sam & Dave or the one by the Blues Brothers — they're both played with Donald “Duck” Dunn on bass). The bassist plays a perfectly complex yet unobtrusive groove. It blends so well that it's kind of difficult to think of what exactly the bass is doing.

- Bold grooves: Playing a bold groove thrusts you into a leadership position; you're leading the song, and your bass part has a much more authoritative and unyielding quality. This means, of course, that you have to be very familiar with the song.

The Beatles’ “Come Together” (with Paul McCartney on bass) is a perfect example of a bass line that really sticks out, creating a secondary melody to the song. It doesn't blend in at all.

Just blending in: How to do it

A blending bass groove is a favorite device of session bassists, who may play in hundreds of recording sessions per year. After all, this type of groove is the perfect vehicle to support a song without diverting attention from the melody and words.

You can achieve the desired blending effect as a bass player by keeping your notes low. Yes, I know, it's kind of a no-brainer — it is a bass. What I mean is keeping the notes you use to flesh out the groove below the root of the groove skeleton (see Chapter 6 for a definition of the groove skeleton). In other words, after you establish the groove skeleton, play the follow-up notes lower than the root.

Figure 13-10: A blending groove.

The bold and the beautiful: Creating a bold groove

When you want to capture the ear of your audience, create a bold groove by choosing a sequence of notes that rise. Let your notes soar upward. After you establish the groove skeleton, play the follow-up notes higher than the root (instead of lower).

Figure 13-11: A bold groove.

Blending and bolding by genre

The choice of using a blending groove versus a bold groove falls squarely on your shoulders as the bass player. You're the one to choose which kind of groove to go for, but you don't want to use a groove arbitrarily. You need to follow certain broad guidelines, and as you gain experience, you develop an ear for what's needed. Both types of grooves work in all genres.

Rock, for example, may call for a blending or a bold groove, depending on the particular style of the tune. For example, a pop style (singer-songwriter) usually needs a blending groove, because the words need to be understood. A progressive rock tune, on the other hand, is much more likely to sport a bold groove. Both styles are part of the rock genre but call for very different groove types.

In other cases, the choice between using a blending versus a bold groove is even more subjective. Take R & B/Soul, for example. Some songs have a busy but blending bass groove (the Temptations’ “Cloud Nine” is an excellent example), while others have an equally busy but bold groove (the Four Tops’ “Bernadette” comes to mind). Both songs are part of the same genre (R & B/Soul) and even the same style (Motown), yet one has a blending groove while the other is bold. As you gain more experience in playing bass, the choice between whether to use a blending or a bold groove becomes easier.

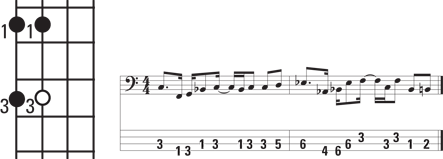

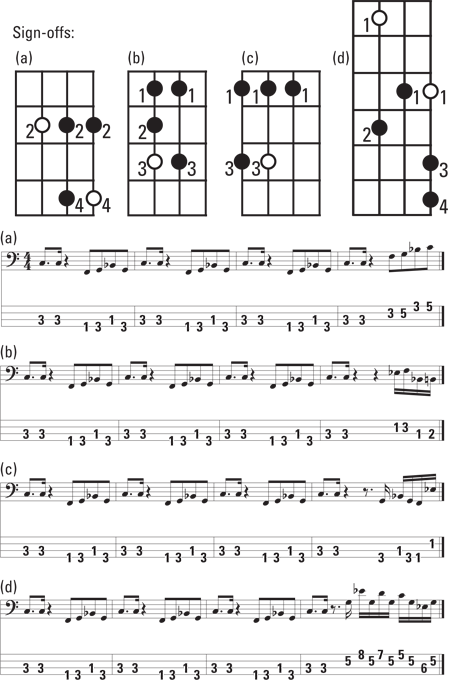

Signing off with a flourish

Putting your own stamp on a groove is just like writing a letter. In a letter, you take care of all the important points you need to cover and then sign it at the end. It's the same with bass grooves.

A sign-off is usually in contrast to the rest of the grooves in a phrase and signals that a large four- or eight-bar phrase is about to be completed. Some musicians refer to this as a turnaround. This is your flourish, your personal signature. You use this element to alert the other players and the listeners that you're about to start a new phrase (for an explanation of phrases, check out Chapter 4).

You can sometimes tell who the bass player is by listening to his or her signature at the end of a phrase. Jaco Pastorius, for example, signs off very differently than Paul McCartney, and Donald “Duck” Dunn does it quite differently than Pino Palladino.

Figure 13-12: Sign-offs, or turnarounds, for a groove.

Each genre may include several different styles that are closely related. Visit Chapters

Each genre may include several different styles that are closely related. Visit Chapters  Check out Video 32 to see me playing the various genre grooves covered in the following sections.

Check out Video 32 to see me playing the various genre grooves covered in the following sections. To get a grip on sixteenth-note rhythms and all their subdivisions, practice playing the patterns in Chapter

To get a grip on sixteenth-note rhythms and all their subdivisions, practice playing the patterns in Chapter