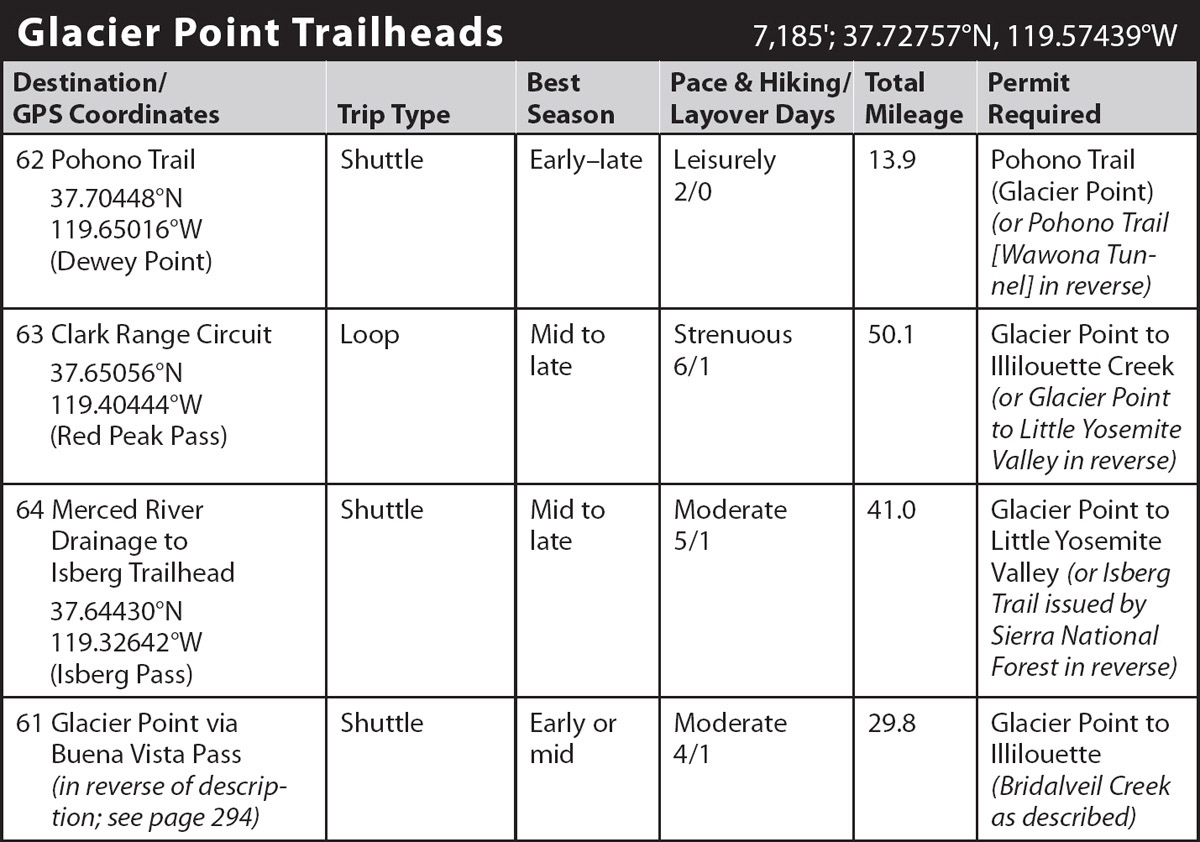

INFORMATION AND PERMITS: These trips begin in Yosemite National Park: wilderness permits and bear canisters are required; pets and firearms are prohibited. Quotas apply, with 60% of permits reservable online up to 24 weeks in advance and 40% available first-come, first-served starting at 11 a.m. the day before your trip’s start date. Fires are prohibited above 9,600 feet. See nps.gov/yose/planyourvisit/wildpermits.htm for more details.

DRIVING DIRECTIONS: From a signed junction (Chinquapin Junction) along Wawona Road (CA 41), drive 15.7 miles on Glacier Point Road to its end; the hikes start from the road-end parking area.

trip 62 Pohono Trail

Trip Data: |

37.70448°N, 119.65016°W (Dewey Point); 13.9 miles; 2/0 days |

Topos: |

Half Dome, El Capitan |

HIGHLIGHTS: The Pohono Trail follows Yosemite Valley’s southern rim, visiting five major viewpoints as it traverses west from Glacier Point. Along this hike you will encounter mostly day hikers, and indeed the trip can be quite easily completed in a day. However, it is well worth making it an overnight trip, for it is a route with endless opportunities for sitting and absorbing the views, especially during the evening and morning hours.

SHUTTLE DIRECTIONS: The endpoint is variously called Tunnel View Trailhead, Pohono Trailhead, and Wawona Tunnel Trailhead. It is located at Discovery View (aka Tunnel View), at the east end of the Wawona Tunnel. This is on Wawona Road (CA 41), 1.5 miles west of where CA 41 merges with Southside Drive in Yosemite Valley—or 7.75 miles north of the Chinquapin junction where the Glacier Point Road begins. The trailhead is on the south side of the road at the back of the smaller, subsidiary parking lot.

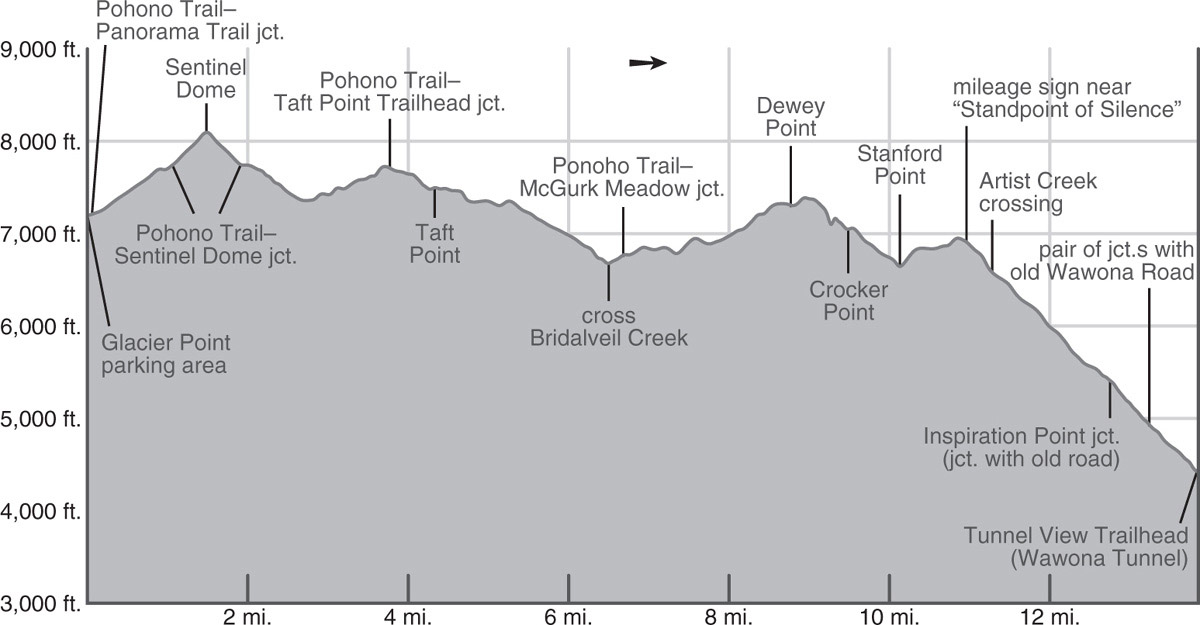

DAY 1 (Glacier Point to Bridalveil Creek, 6.5 miles): The shortest way to the correct trail is to make your way east from the parking area to the Glacier Point amphitheater, but if you have never been to Glacier Point itself, you should first detour to the main vista point overlooking Yosemite Valley.

You pick up a trail at the southern edge of the amphitheater and follow it, quickly reaching a fork where the Panorama Trail veers left (southeast), but you trend right (southwest), on the Pohono Trail. The Pohono Trail soon crosses the Glacier Point Road and completes a pair of switchbacks up through an open red fir forest, before the trail begins a long northwesterly traverse around a ridge. The trail turns south to continue circumventing the ridge, and soon you reach a junction in a cool gully where the Pohono Trail continues right (southwest), while left (northeast) is a spur leading to Sentinel Dome. Your eventual route is along the Pohono Trail, but first take the detour to Sentinel Dome, Yosemite Valley rim’s second highest viewpoint—only Half Dome is taller.

Climbing onto, then up the ridge, the trail keeps crossing paths with an old service road leading to a radio facility; stick to the steep trail. At a signed trail junction you meet the route standardly used to access Sentinel Dome and turn right (southwest) to ascend the final slope to the summit. As you ascend the bedrock slopes, watch your footing, for although there is nowhere far to fall, it is remarkably easy to slip on the gravel and sand lying atop slabs of rock.

Sentinel Dome was formed by the exfoliation of rock layers, rather than by glaciation and the rock exposed here—like everywhere on this walk—has been weathering for hundreds of thousands of years. Exfoliation is the shedding of thin layers of granite slab from the surface of the dome, and if you stare closely at the steep sides of Sentinel Dome, you can, without too much imagination, see it as a giant onion slowly being peeled apart. But the view is likely what most captures your attention, especially the panopoly of summits to the east that will be hidden for the remainder of your walk. Meanwhile, El Capitan, Yosemite Falls, and Half Dome stand out as the three most prominent valley landmarks. Northwest of Half Dome are two bald features, North and Basket Domes. On the skyline above North Dome stands blocky Mount Hoffmann, the park’s geographic center, while to the east, above Mount Starr King, an impressive unglaciated dome, stands the rugged crest of the Clark Range. A disc atop the summit identifies these landmarks and many others. Now return to the junction with the Pohono Trail, and turn left, continuing west.

Over the coming 0.8 mile, the trail descends gently but steadily, dropping 400 feet as it skirts around the steep northwestern slopes of Sentinel Dome toward seasonal Sentinel Creek. Approaching the crossing, you drop from drier, shrub-dominated slopes into a dense red fir forest, step across the creek, and soon exit the closed forest canopy again to ascend a drier ridge of broken slabs dotted with Jeffrey pines. In spring, detour along Sentinel Creek’s eastern bank toward the valley rim for an exposed view of ephemeral Sentinel Falls and a little-visited view to Yosemite Falls. Onward, the grade slowly increases, leading to a junction, where left (east) leads back to a Glacier Point Road parking area, the trailhead commonly used to hike to Sentinel Dome and Taft Point, while the Pohono Trail continues right (west) toward Taft Point.

Around the first corner you enjoy a seeping creeklet that drains through a small field of corn lilies, bracken fern, and a rainbow of other tall flowers that thrive in this moist, shaded glade. Leaving this colorful distraction behind, the trail continues descending toward the Yosemite Valley rim, now across drier slopes of broken slabs, which are covered with shrubs and drought-tolerant wildflowers.

Soon you arrive at The Fissures—five vertical, parallel fractures that cut through overhanging Profile Cliff just beneath your feet. Because this area, like your entire route, is unglaciated, there is much loose rock and gravel; take care, for a misstep could be dangerous in this area. A short unsigned spur trail leads to fantastic views down the slots.

Just beyond The Fissures, where the Pohono Trail makes a near U-turn, you turn right (north) and walk briefly up a spur trail to “Taft Point,” where a small railing, offering remarkably little protection, marks the viewpoint at the brink of overhanging Profile Cliff. From this viewpoint, and true Taft Point, off to your left (northwest) and completely unprotected, your sight line of the valley’s monuments is unobstructed. It includes the Cathedral Spires, Cathedral Rocks, El Capitan, the Three Brothers, Yosemite Falls, and Sentinel Rock. But it is the view northwest to the prow of El Capitan that Taft Point showcases better than any other Yosemite rim vista—how the gentle rolling upland is abruptly truncated with the 3,000-foot-tall granite wall is truly awe inspiring.

Vista of Yosemite Valley from Stanford Point Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

Most day hikers turn back at Taft Point and the next miles of trail are much less walked. You traverse open stretches, where slabs lie close to the surface and vegetation is sparse, step across small trickles whose banks are densely decorated with colorful wildflowers, and walk through beautiful dense fir forests, first red fir, then as you drop in elevation, white fir. The fir forest here is wonderful—this is one of the rare bits of Yosemite to not yet suffer the consequences of a catastrophic forest fire, and it is well worth enjoying the deep shade that the lichen-laden firs provide. This wonderful, relaxing, downhill walking continues until you cross Bridalveil Creek on a bridge. This is the only permanent water source along the route and is therefore the best place to spend the night; there are various small campsites just northwest of the bridge (6,680'; 37.69399°N, 119.62195°W). If you want to make a dry camp (that is, carry water from here), there are also flat sandy sites closer to Dewey Point.

DAY 2 (Bridalveil Creek to Discovery View at Wawona Tunnel, 7.4 miles): Continuing along the Pohono Trail, you soon reach a junction with the lateral to Glacier Point Road that passes through McGurk Meadow. Still continuing westward (right) along the Pohono Trail, you pass through a series of sandy flats, then cross a broad, low divide. As with yesterday’s walk, you are repeatedly treated to beautiful rich fir forests, the chartreuse lichen on their trunks marking the winter snow level. Traipsing along you cross three seasonal Bridalveil Creek tributaries, the first two larger, the third smaller, then start up a fourth that drains a curving gully. To your right (north) are some small campsites, if there is still water. On the gully’s upper slopes, Jeffrey pine, huckleberry oak, and greenleaf manzanita replace the fir cover.

In a few minutes you reach highly scenic 7,385-foot Dewey Point, located at the end of a short spur trail. If you have a head for heights, you can look straight down the massive face that supports Leaning Tower. Just to the right are the steep Cathedral Rocks rising on the other side of Bridalveil Creek. Looking across Yosemite Valley, the broad, smooth face of El Capitan rises high above the valley floor. Also intriguing is the back side of Middle Cathedral Rock, with an iron-rich, rust-stained surface.

Returning to the Pohono Trail again, you continue west. The remaining 5.1 miles are almost entirely downhill, and you descend 0.75 mile to Crocker Point, the vista point again located at the end of a spur trail on the brink of an overhanging cliff that provides a heart-pounding view similar to the last one. Thereafter, a 0.65-mile descent, mostly well south of the rim, takes you down to Stanford Point, also at the end of a short spur trail. Its views are similar to those from Crocker Point, although more of Yosemite Valley’s walls are hidden behind nearby features.

From that point, you climb 250 feet south up the ridge rising above Stanford Point, leading away from the valley rim, passing a welcome spring, and soon dropping slightly to Meadow Brook. If any water remains along this trail through midsummer, it will be found here. Thickets of tasty thimbleberries, azaleas, and scrubby red-stemmed American dogwood lap up the moisture. Among red firs, you make an undulating traverse, shortly reaching a puzzling metal mileage sign that is neither at a junction nor an obvious vista (6,920'; 37.70284°N, 119.67270°W). Just 100 feet (in elevation) downslope of here is the location of one of many old vista points along the next section of trail, this one once dubbed the “Standpoint of Silence.”

OLD INSPIRATION POINT

About 0.15 mile past the mileage sign, turning right (north) off the trail leads to the valley rim at the location still marked “Old Inspiration Point” on the topo maps; however, few people will find the brushy 200-foot off-trail descent worth the detour. Before construction of the old Wawona Road, the stock trail built by the Mann brothers in 1856 offered access to it, for it would have been the first major Yosemite Valley vista on their route from Wawona to Yosemite Valley.

Continuing, the Pohono Trail now completes a 300-foot descent into the Artist Creek drainage. Crossing Artist Creek, the trail continues down, the first 400 feet steeply as the north-trending trail traverses from the drainage onto a ridge. Where the trail bends west, there is another brushy opportunity to descend 200 feet off-trail to the northeast to another rocky vista point, this one labeled Mount Beatitude on old maps—although it is unlikely more blessed than the other vista points you’ve enjoyed. The trail descends slightly more gradually for the following 600 feet. The forest here is increasingly open and the temperatures warmer.

At 5,600 feet the trail turns more northeasterly again and continues down to a junction with an old road which leads left (west) to the next “Inspiration Point,” a commanding viewpoint passed by travelers on the stage road built to replace the Mann Brothers’ trail, but now somewhat overgrown. You stay right (northeast), on the trail, and descend another 500 feet via short switchbacks, now having oaks and conifers shade you, but also hiding most of the scenery. After 0.5 mile, you intersect the old Wawona Road itself and jog just 30 feet left (west) along it, then turn right (northeast) to continue your downward route. The final 0.6 mile is again steep and scrubby, with only broken views, taking you to the Pohono Trail’s end at the southside parking lot of tourist populated Discovery View at the eastern entrance to the Wawona Tunnel. This is the inspiring first viewpoint to Yosemite Valley that is enjoyed by throngs of today’s travelers on the modern road from Wawona (4,398'; 37.71510°N, 119.67678°W)!

trip 63 Clark Range Circuit

Trip Data: |

37.65056°N, 119.40444°W (Red Peak Pass); 50.1 miles; 6/1 days |

Topos: |

Half Dome, Merced Peak, Mount Lyell, |

HIGHLIGHTS: The Clark Range is the rugged crest bisecting southern Yosemite; it is striking from any vista point in the southern half of the park. This remote loop encircles the range, providing endless views and leading you along two beautiful river drainages, the lesser visited corridor harboring Illilouette Creek and the deep, rugged canyons through which the mighty Merced River flows, as well as over alpine Red Peak Pass.

HEADS UP! This hike can also be started at the Mono Meadow Trailhead, in which case you will join the trail at the Illilouette Creek–Mono Meadow junction, 3.9 miles into the hike. If you are unable to secure a permit leaving Glacier Point, this is a good alternative. It is actually 1 mile shorter but requires a (short) car shuttle.

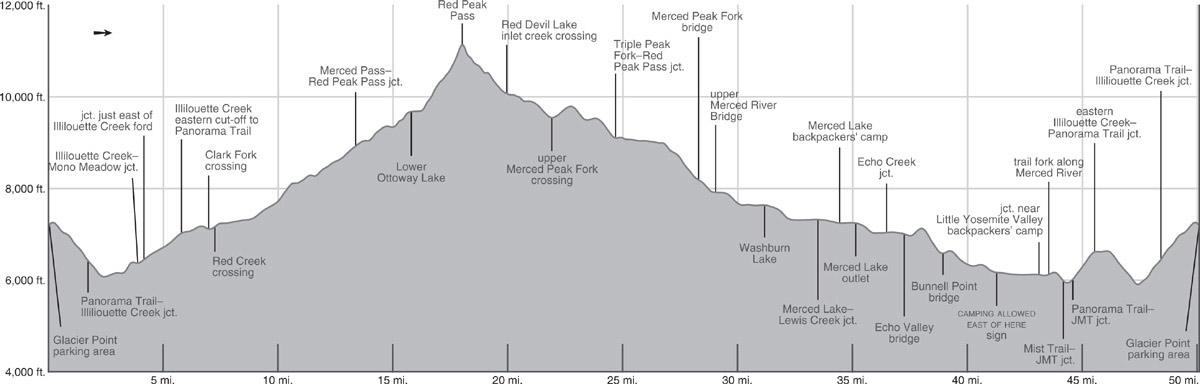

DAY 1 (Glacier Point parking area to Clark Fork Illilouette Creek, 6.9 miles): The shortest way to the correct trail is to make your way east from the parking area to the Glacier Point amphitheater, but if you have never been to Glacier Point itself, you should first detour to the main vista point overlooking Yosemite Valley.

You pick up a trail at the southern edge of the amphitheater and follow it south, quickly reaching a fork, where you trend left (southeast) on the Panorama Trail, while the Pohono Trail veers right (southwest; Trip 62). You climb a bit more before starting a moderate descent, initially with grand views to the east. A 1986 natural fire blackened most of the forest from near the trailhead to just beyond the upcoming Buena Vista Trail junction, with only patches of trees surviving. In the open areas, black oaks are thriving, and shrubs have regenerated with a vengeance, but in open patches there are still great views of Half Dome, Mount Broderick, Liberty Cap, Nevada Fall, and Mount Starr King between blackened trunks. Views become more restricted as you descend, and eventually you meet the Buena Vista Trail.

Lower Ottoway Lake Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

Turning right (south) to follow the Buena Vista Trail, you now descend a steep sandy slope through firs, manzanita, and spiny chinquapin leading to the banks of Illilouette Creek. Then, for nearly a mile you climb along the creek corridor as it winds through a gorge, a most spectacular experience. There are cascades; big, deep pools; giant, smooth boulders; and mill holes in rocks created by the churning water. Pink and yellow azalea flowers grace the banks.

Fording a creek descending from Mono Meadow, you leave Illilouette Creek’s banks and climb a mostly open slope to a junction where right (west) leads to Mono Meadow, while you continue left (east). Just 100 feet later you reach a second junction, where right (north) is the Buena Vista Trail (Trip 61), while you turn left (east) to continue ascending the Illilouette Creek drainage. Passing campsites to either side of the trail, you immediately drop to a ford. Notoriously dangerous at high flows and still a knee-height wade in midsummer, contemplate the large rounded cobble on the riverbed—such large rocks indicate how tumultuous the water here can be. (Note: If, when picking up your wilderness permit you are warned this crossing is hazardous, there is an alternative route that is 2.4 miles longer and requires more climbing, but it crosses Illilouette Creek on a footbridge. At the junction 1.7 miles from the trailhead, stay on the Panorama Trail for an additional 2.9 miles, then turn right (south), staying right (south) at a second junction and rejoining the described route at the 5.7-mile mark, at the Illilouette Creek eastern cut-off junction shown on the elevation profile.) Climbing up the far riverbank, you come to yet another junction, this one on a sandy flat. Here, you head right (east), up the Illilouette Creek drainage, while left (north) leads back toward the Panorama Trail.

Following the bare slope eastward, you gently ascend a ridge while enjoying views ahead to Mount Starr King, a striking, bald dome. Even the forest stands you pass through are sparse, for only shallow soils lay atop the bedrock here. Gradually the trail trends southeasterly and sidles up into an Illilouette Creek tributary that you follow to the next junction, where those taking the “hazardous crossing” detour rejoin the route.

Turning right (southeast), your southeasterly-trending route continues on a bench well above Illilouette Creek through a dry open forest dominated by Jeffrey pines and red fir. Some giant fractured boulders undoubtedly catch your eye; these fell from a dome north of here hundreds of years ago. Some tree bases bear fire scars from low-intensity burns in decades past. Traipsing onto a more open slope, Grey Peak and Red Peak become visible through the trees to the southeast, their bedrock hues matching their names. Ahead you come to a pair of creek crossings, the Clark Fork Illilouette Creek and Red Creek, both currently crossed via logs at high flow. Below the trail, the Clark Fork cascades impressively down slabs as it drops to unite with Illilouette Creek. There are a number of good campsites on knobs and in sandy flats near the first crossing—a good place to spend your first night (7,111'; 37.67938°N, 119.50118°W).

DAY 2 (Clark Fork Illilouette Creek to Lower Ottoway Lake, 8.9 miles): The trail continues its southerly bearing, initially still high above Illilouette Creek, crossing the crests of a series of low moraines. The ground cover here is lush, even grass covered in patches, for the soil is, in part, derived from the metamorphic rocks comprising Grey and Red Peaks. Metamorphic soils are more nutrient rich and hold water better than the surrounding granitic sands, supporting more luxuriant plant growth. It also makes for pleasant, soft walking underfoot.

Beneath a moraine, 1.4 miles from the Clark Fork, you reach the banks of Illilouette Creek and begin a delightful, albeit exposed, journey upstream along its eastern bank. The forest is mostly open and granite slabs extend right to the water’s edge, allowing you to continually enjoy the beautiful bubbling, cascading creek. Near the start of this section, water seeps from the base of the moraine, irrigating small wildflower gardens, while cracks in the slabs are filled with magenta mountain pride penstemon. Aspen groves fill many of the flatter pockets, contrasting with the familiar conifer forests. The distractions are welcome, for you are walking uphill across slabs, stepping over rocks, and ascending uneven steps—this is not a fast stretch of trail. Along the way, you can find several, mostly small, places to camp along the creek’s east bank.

At 3.3 miles after reaching Illilouette Creek’s banks, you step across a tributary, then Illilouette Creek itself in rapid succession (campsites nearby); both crossings currently have handy logs. The trail now winds upward among outcrops and boulders, leveling out to weave through a small glade before ascending another narrow corridor between steeper slabs. Crossing Illilouette Creek again, now often barely flowing in late summer, the trail soon passes close to Lower Merced Pass Lake, a forest-rimmed lake with bright white slabs descending to its western shore; there are ample campsites near here. Beyond, one more upward step in the landscape brings you to a junction, where you turn left (east) toward Lower Ottoway Lake and Red Peak Pass, while right (south) leads to Merced Pass. Upper Merced Pass Lake, just out of sight to the southeast, has lovely campsites along its western shore; from the main trail junction, you’ll notice a blocked off but well-worn use trail heading to it. If you’re short on water, take the short detour to the lake, for most of the unnamed creeklets nearby are dry by midsummer.

Striking out in a generally northeasterly direction, the trail to Lower Ottoway Lake rises and falls over a series of ridges emanating from a spur west of Merced Peak, as it slowly traverses toward Ottoway Creek. The landscape shifts in tandem, dropping into moist red fir communities in the draws, then climbing back to drier slab environments. After 1.7 miles you cross Ottoway Creek (currently on a log), near a small campsite, and begin a more diligent upward trajectory. With increasing elevation, fewer forested glades interrupt the rocky switchbacks up slabs, and after another 0.75 mile you reach the shores of Lower Ottoway Lake. There are campsites both on a flat knob northwest of the lake (9,678'; 37.64324°N, 119.42044°W; no campfires) and in forest stands to its east. Anglers can dangle lines for tasty rainbow trout.

DAY 3 (Lower Ottoway Lake to Triple Peak Fork Merced River, 8.9 miles): Red Peak Pass, your immediate goal, lies just 2.25 miles beyond Lower Ottoway Lake’s outlet, but with a nearly 1,500-foot climb, it takes a little time. After a pleasant 0.4 mile dawdle to the eastern side of the lake, the steep climb begins, oscillating between metamorphic and granite rock. The upcoming mile is a delight for wildflower enthusiasts—bright bursts of color decorate the ground on both the dry, slabby stretches of trail and beside the numerous trickles of water you step across. What better distraction from the arduous climb? After just over a mile and 800 feet of ascent, there is a brief interlude in the slope. If you were to cut south from here across broken, reddish-hued slabs you would pass a small lake, then reach Upper Ottoway Lake, offering imposing views of Merced and Ottoway Peaks’ headwalls and the deep cirque beneath them that once held Merced Peak’s Little Ice Age glacier, but virtually no campsites.

On the trail, you now trend north, briefly along a grassy meadow, then onto the final 28 switchbacks to the pass, zigzagging up a generally dry, sandy slope to the summit of 11,143-foot Red Peak Pass. From the pass, you have views as far as Matterhorn Peak along the park’s north rim. Closer, Mount Lyell crowns the upper Merced River basin and is flanked on the northwest by Mount Maclure and on the southeast by Rodgers Peak. Pyramid-shaded Mount Florence breaks the horizon west of this trio, while east of all of them, the dark, sawtooth Ritter Range pokes above the horizon. Below the peaks lies a broad upland surface that is cleft by the 2,000-foot-deep Merced River Canyon, at whose headwaters you will finish your day.

After a well-earned break, you begin the 6.6-mile descent to the Triple Peak Fork Merced River. The initial headwall is descended via tight switchbacks down a steep talus slope; fortunately the trail is in good shape, having been reworked and rerouted to minimize summer snow cover and rockfall damage. The trail next leads into a drainage where a cluster of tarns marks the headwaters of the Red Peak Fork, then cuts northeast down a rocky rib. Past the first stunted whitebark pines, the trail turns south to reach a shelf cradling a shallow tarn. On a map, this looks like tempting camping terrain, but keep your expectations in check, for you may enjoy beautiful flower displays on metamorphic substrates, but you will be less enamored by how it generally decomposes to form a pavement of sharp-tipped cobble and boulders—not ideal for a tent.

Absorbing the exquisite views of the Cathedral Range, you continue past another cluster of ponds, turn north to descend a rib, and quite suddenly find yourself back in granite. Indeed, at the next lake you pass, at 9,900 feet, there are amazing treeline campsites in sandy patches among the granite slabs northeast of the lake.

Continuing your descent, note that the cliffs overhead are all grayish metamorphic rock, while you are on the other side of the geologic contact, walking among the most beautifully polished granite slabs, with trees growing only in strips of deeper soil between the ribs of rocks. You cross the Merced Peak Fork where it meanders through a beautiful meadow ringed by hemlock trees (limited campsites) and climb north, then east across a shallow rib to a small saddle cradling two tarns.

The final 1.9 miles to the Triple Peak Fork are mostly under forest cover, a mix of hemlock, western white pine, and, of course, lodgepoles, some of them magnificently large specimens. The trail’s location is well placed, winding down forested ramps. Near the bottom, broken rock and small bluffs further constrain the trail’s route, restricting it to the sinuous passageways between them. Then quite suddenly you reach the bright white slabs of the river corridor and a junction (9,105'; 37.65847°N, 119.34456°W). There are good forested campsites near the junction or ones on open slab a few minutes upstream or downstream. Fishing is good for brook and rainbow trout.

DAY 4 (Triple Peak Fork Merced River to Merced Lake, 9.7 miles): Follow Trip 55, Day 4 for the 5.9 miles to Washburn Lake (7,640'; 37.71130°N, 119.36661°W). Today’s description then continues another 3.8 miles downriver.

Continuing, the mostly open, sandy trail continues right along the east side of Washburn Lake. Beyond the lake, the trail continues its moderate descent along the river through open forest and across slabs, fording a small stream every quarter mile or so. Where the canyon floor begins to widen, the trail diverges east from the river, hugging the cliff walls as it skirts a big previously burned flat, now dense with scrub and downed trees (but harboring a few campsites in the direction of the river). The trail proceeds levelly to the Merced Lake Ranger Station (emergency services available in summer) and a junction where you turn left (west) toward Merced Lake, while right (north) leads up Lewis Creek (Trip 55).

Crossing multistranded Lewis Creek on a series of footbridges, the nearly flat trail soon leads past some campsites and through a peaceful Jeffrey pine forest—this is one of the few places in the park where such a forest exists, with well-spaced trees and a beautiful forest floor of large cones and long, shiny needles. If you’d like a private campsite for this night, search in the direction of the Merced River along this length. Trending north, west, and then south the trail skirts around a rocky rib and descends briefly into the Merced Lake basin. Turning north again, you pass the Merced Lake High Sierra Camp, with its meager store and drinking water faucet, and continuing along the trail, soon reach the Merced Lake backpackers’ camp (7,242'; 37.74049°N, 119.40718°W) to the north of the trail (and before reaching Merced Lake itself). The only legal camping along Merced Lake, it offers a pit toilet and bear boxes. The relatively warm lake is ideal for swimming, and fishing is also fair.

DAY 5 (Merced Lake to Little Yosemite Valley, 8.7 miles): West of the backpackers’ camp, the trail skirts Merced Lake’s quiet northern shore. At its outlet, the steep granite slabs comprising the canyon walls pinch together and the river chutes downstream, foaming and churning as its races down slabs—you enjoy this spectacle just feet from the river’s edge. Where the trail turns away from the river are some small campsites north of the trail, some on sand, others in lodgepole glades. Descending again, you reach the east end of boggy Echo Valley, a dense tangle of approximately 15-foot-tall lodgepole pines, regenerating after fires in 1988 and 1993. In the middle of the thicket you cross Echo Creek’s braided river channels on three bridges and come to a junction with a trail ascending right (north) up Echo Creek (Trip 46), while you continue straight ahead (west) down the Merced River corridor. The western end of spacious Echo Valley was less impacted by fire, and a few campsites exist atop sandy knobs.

At the valley’s western end, you cross the river on a sturdy bridge and skirt across a steep slab slope on a narrow trail. From the bench you can study an immense arch on the broad, hulking granitic mass opposite you and watch the water churning below. Continuing alternately across bedrock and through small glades, your climb reaches its zenith amid a spring-fed wildflower garden bordered by aspens.

The trail then descends more than a dozen switchbacks down an open, rocky slope for 400 feet back to the river’s banks. You follow the south bank briefly downstream and then cross the Merced River on a pair of bridges. Just after the crossing there are small campsites atop slabs right (east) of the trail. Within minutes, the trail and creek are together forced into the center of a narrow gorge, as Bunnell Point to the south and a steep unnamed dome to the north constrict the river corridor. The river tumbles down bare granite slabs, culminating in Bunnell Cascade, while the trail switchbacks to its side. You drop into Lost Valley, badly charred in the 2014 Meadow Fire. Previously much of this section had been a dense forest with abundant dead material on the ground, providing ample fuel for the fire to spread; this is a natural process and was caused by a lightning-strike fire, but the lack of shade and loss of beautiful dense forest stands are nonetheless unwelcome to a backpacker.

At its end, the Merced’s flow is again pinched, this time by unofficially named Sugarloaf Dome to the north, and again chutes down bare slabs. It lands in a beautiful pool, a superb swimming hole—and a popular campsite until the Meadow Fire blackened the environs. The next 0.3 mile is the last legal camping before Little Yosemite Valley’s backpackers’ campground 2.2 miles to the west. Trying to be optimistic about the fire-scorched landscape, admire the blackened tree trunks as artistic totems and note that the lack of trees improves the views of the canyon’s walls. A thick accumulation of glacial sediments covers most of the valley floor, which, like beach sand, makes you work even though the trail is level. Soon after you enter standing forest, you cross Sunrise Creek and reach a junction at the southern edge of Little Yosemite Valley’s backpackers’ camp (6,120'; 37.73196°N, 119.51536°W), the last campsite before the trailhead. Turning right (north) you’ll quickly reach the large camping area, with toilets, food-storage boxes, and (usually) a ranger stationed just to the northeast.

Day 6 (Little Yosemite Valley to Glacier Point, 7.0 miles): Returning to the junction just south of the camping area, turn right (west) and proceed just out of sight of the Merced River’s edge to a junction where your trail merges with a second Little Yosemite Valley route. You continue straight ahead (left; west), first along the river’s azalea-lined bank and then over a small saddle. On its far side, the trail descends a brushy, rocky slope to reach a junction (and pit toilets) where the John Muir Trail (JMT), the route you’ve been following since the campsite, trends left (south), while the infamously steep Mist Trail descends the steep gully to the right (west), en route to Yosemite Valley.

Staying on the JMT, you climb briefly to slabs lining a picturesque stretch of river—but do not swim here, for you are just steps from the brink of Nevada Fall. For an aerial vista, about 100 feet before the bridge, strike northwest (right) to find a short spur trail that drops to a shelf with a fenced viewpoint beside the fall’s brink. Returning to the trail, cross the bridge, climb briefly through a glade of tall firs, and soon reach a junction with the Panorama Trail, where you turn southwest (left) toward Glacier Point, while the JMT stays right (west), bound for Yosemite Valley destinations.

Climbing diligently for the first time in many miles, you pass slabs with a low rock wall, once built to divert runoff away from the JMT, located at the base of the cliff face. You then disappear under forest cover and switchback up a pleasantly cool slope with soft conifer duff underfoot. A 600-foot ascent brings you to a junction, where the Panorama Trail, your route, stays right (west), while left (south) leads back up the Illilouette Creek drainage.

The trail now makes a broad, arcing contour around the top of Panorama Cliff. The name is fitting, for your senses are soon dominated by the vista to the east: Half Dome, Mount Broderick, Liberty Cap, Clouds Rest, and Nevada Fall. Stay a few steps back from the cliff edge—a former viewpoint near Panorama Point, a little farther west, was undermined, in part, by a monstrous rockfall that occurred in spring 1977 and left the vista’s railing hanging in midair. After imbibing the views, the route begins to descend, first on two long switchbacks, then on a long traverse to the southwest, and finally via a series of tighter switchbacks that drop you to the banks of Illilouette Creek. The trail briefly traces the creek upstream before crossing it on a bridge.

While the broad views and creek have been beautiful, you are still waiting for a glimpse of Illilouette Fall itself. This comes 0.3 mile past the bridge, on your first long switchback north. Just as you are about to turn south again, note an indistinct spur trail that goes a few steps below the trail to a viewpoint. Here, from atop an overhanging cliff, you have an unobstructed view of 370-foot-high Illilouette Fall, which splashes just 600 feet away over a low point on the rim of massive Panorama Cliff. Behind it Half Dome rises boldly, while above Illilouette Creek, Mount Starr King rises even higher. Returning to the trail, five more switchbacks lead up to the trail junction, where on the first day you headed south up Illilouette Creek. Now, turn right (north) and retrace your steps to Glacier Point.

trip 64 Merced River Drainage to Isberg Trailhead

Trip Data: |

37.64430°N, 119.32642°W (Isberg Pass); 41.0 miles; 5/1 days |

Topos: |

Half Dome, Merced Peak, Mount Lyell, Timber Knob |

HIGHLIGHTS: This route traverses the very heart of southeastern Yosemite, following the Merced River to its headwaters. You then climb to Isberg Pass, boasting one of Yosemite’s premier views, before descending into the San Joaquin River watershed and passing a sequence of beautiful lakes. Remoteness and panoramic vistas invite you to take this trip. Only the notably long car shuttle might dissuade you—if you are able to take additional days, you could loop back to Glacier Point via Fernandez Pass, Merced Pass, and the trail down Illilouette Creek.

SHUTTLE DIRECTIONS: The Isberg Trailhead near Clover Meadow is the most remote trailhead in this book—and a long car shuttle from Glacier Point. From Yosemite Forks on CA 41 (3.4 miles north of Oakhurst and about 12 miles south of Yosemite National Park’s Wawona entrance station) follow Road 222, signposted for Bass Lake, 3.5 miles east. Here the road becomes Malum Ridge Road (Road 274). Continue straight ahead (east) 2.4 more miles to a junction with FS 7 (5S07), where you turn left (north) onto Beasore Road.

Now reset your odometer to zero. Paved but windy Beasore Road climbs north, passing Chilkoot Campground at 4 miles, followed by a series of dirt roads departing westward. At 11.6 miles, you reach a four-way intersection at Cold Spring Summit, with Sky Ranch Road (FS 6S10X) to the left and a parking area with toilets is on the right. Continuing straight ahead on Beasore Road (FS 5S07), you wind past Beasore Meadows, Jones Store, Mugler Meadow, and Long Meadow. At 20.2 miles, you reach Globe Rock (on your right; toilets) and FS 5S04 (on your left).

Beyond Globe Rock the road surface can be speckled with potholes, although it is being resurfaced during the summer of 2020. Ahead you pass a spur to Upper Chiquito Campground (21.3 miles), the impressive granite domes named the Balls (24.2 miles), the Jackass Lakes Trailhead (26.8 miles), and the Bowler Campground (27.1 miles). Soon thereafter two prominent spur roads bear left, first one to the Norris Trailhead (FS 5S86; 27.5 miles) and just beyond one to the Fernandez and Walton Trailheads (FS 5S05; 27.6 miles).

Continuing on Beasore Road, you pass FS 5S88 (branches south 0.4 mile to Minarets Pack Station; 29.6 miles) and quickly meet the end of paved Minarets Road (FS 4S81; 29.8 miles), which has ascended 52 paved miles north from the community of North Fork. At this junction, stay left (northeast), turning onto FS 5S30, and drive 1.8 miles to a junction at Clover Meadow Ranger Station. The entrance to Clover Meadow Campground is just beyond it, a pleasant campground with piped water, vault toilets, and—amazingly—cell reception!

You still have a short distance to reach your trailhead. Remaining on FS 5S30, you bear left at a junction with FS 4S60 (bound for primitive Granite Creek Campground), descend to cross the West Fork of Granite Creek, then immediately turn right and parallel the creek east, now on a truly unpaved road. At a Y-junction, bear left (right descends back to Granite Creek Campground), briefly climb a steep hill (yes, it is two-wheel drive), level out, and almost immediately turn right into the quite large Isberg Trailhead parking area, 3.1 miles past the Clover Meadow Ranger Station.

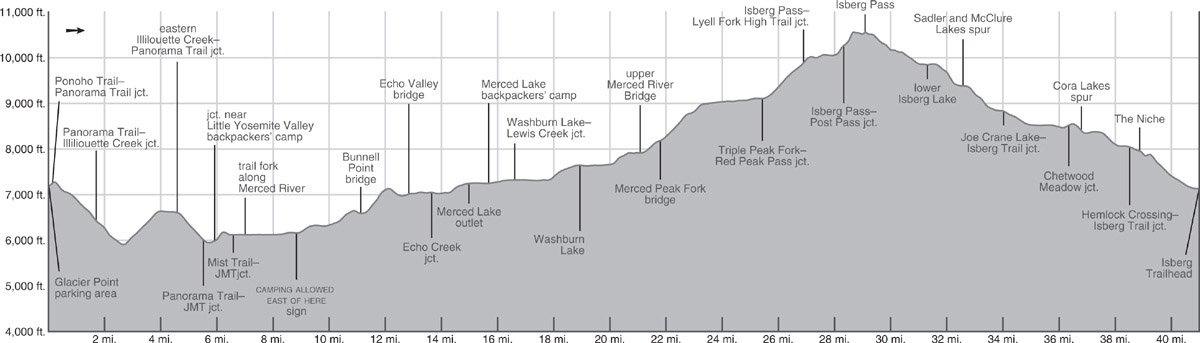

DAY 1 (Glacier Point parking area to Little Yosemite Valley, 7.0 miles): The shortest way to the correct trail is to make your way east from the parking area to the Glacier Point amphitheater, but if you have never been to Glacier Point itself, you should first detour to the main vista point overlooking Yosemite Valley.

You pick up a trail at the southern edge of the amphitheater and follow it south, quickly reaching a fork, where you trend left (southeast) on the Panorama Trail, while the Pohono Trail veers right (southwest). You climb a bit more before starting a moderate descent, initially with grand views to the east. A 1986 natural fire blackened most of the forest from near the trailhead to just beyond the upcoming Buena Vista Trail junction, with only patches of trees surviving. In the open areas, black oaks are thriving, and shrubs have regenerated with a vengeance, but in open patches there are still great views of Half Dome, Mount Broderick, Liberty Cap, Nevada Fall, and Mount Starr King between blackened trunks. Views become more restricted as you descend, and eventually you meet the Buena Vista Trail (Trips 61 and 63).

You turn left (north) here and switchback down toward seasonally raging Illilouette Creek. At the northern end of the fifth (one-way) switchback, an indistinct spur trail goes a few steps below the trail to a viewpoint. Here, from atop an overhanging cliff, you have an unobstructed view of 370-foot-high Illilouette Fall, Half Dome rising boldly behind it. This is not a vista point to be missed, for Illilouette Fall, nestled in a narrow alcove, mostly hides itself from view. The trail makes one final switchback and then crosses the creek on a wide bridge.

Now begins an 800-foot ascent to the top of Panorama Cliff. The trail first climbs briefly along the rim, then switchbacks away from the cliff edge, before once again returning to the rim as you round Panorama Point. After another moderate climb of 200 feet, you descend gently to the rim for more views, now dominated by the monuments to the east: Half Dome, Mount Broderick, Liberty Cap, Clouds Rest, and Nevada Fall. Your contour ends at a junction with a trail up Illilouette Creek.

Here, you go left (east) to stay on the Panorama Trail, which now descends 800 feet toward Nevada Fall via a long series of switchbacks, mostly through a dense forest of tall, water-loving Douglas-firs and incense cedars. When you reach a junction with the John Muir Trail (JMT), turn right (east) onto the JMT and descend to the bridge over the Merced River at Nevada Fall. About 100 feet due north of the bridge, strike northwest (left) to find a short spur trail that drops to a shelf that leads south to a fenced viewpoint beside the fall’s brink. Back on the main trail, you descend briefly and reach the top of the Mist Trail, which has ascended steeply beside the Merced River from Yosemite Valley.

From the junction and its adjacent outhouses, you begin the final climb to Little Yosemite Valley, first by ascending a brushy, rocky slope and then quickly descending and reaching both forest shade and the Merced River. Beneath pine, white fir, and incense cedar, you continue northeast along the river’s azalea-lined bank, soon reaching a trail fork. You keep right (east) on the main, riverside trail and continue just out of sight of the river’s edge, to reach a junction at the southern edge of the Little Yosemite Valley backpackers’ camp (6,120'; 37.73196°N, 119.51536°W). Turn left (north) and within steps you’ll see the tent city to the right where you will spend your first night. There are toilets and food-storage boxes; a usually staffed ranger station is hidden to the northeast of the camping area.

DAY 2 (Little Yosemite Valley to Merced Lake, 8.7 miles): Follow Trip 59, Day 2 from Little Yosemite Valley to the backpackers’ campground at Merced Lake (7,242'; 37.74049°N, 119.40718°W).

DAY 3 (Merced Lake to Triple Peak Fork Meadow, 9.7 miles): Beyond the High Sierra Camp, the trail loops south around a shallow ridge and proceeds a mile east on an almost level, wide, sandy path under forest canopy, noteworthy for the beautiful grove of Jeffrey pines; there are possible campsites here. You cross roaring Lewis Creek on a pair of bridges and arrive at a junction with the trail up Lewis Creek (Trip 46). The Merced Lake Ranger Station, with emergency services in summer, is just south of the junction.

You turn right (south), toward Washburn Lake. For the next 0.6 mile you continue through a broad, flat valley. The trail stays well northeast of the river as it hugs the cliff walls, skirting a previously burned flat dense with scrub and downed trees. Beyond, the valley narrows, but the route is nearly flat for another 0.7 mile, before beginning a moderate ascent alongside the river through open forest and across slabs, fording a small stream about every quarter mile.

The gradient flattens after about a mile and you soon reach Washburn Lake’s outlet, a nice spot for your first break of the day, with the still water mirroring the soaring granite cliffs across the lake on a typically calm morning. Skirting the northeast shore of the lake on a mostly open, sandy trail, you reach an expansive flat near the inlet, with a few campsites interspersed with some downed trees. Continuing to traverse dry slopes above the forested flats, you pass a lovely waterfall and climb to the next broad, flat, valley, where the trail arcs southeast and then south, ascending gradually through an idyllic setting.

You bridge the Merced River just near the confluence of its Lyell and Triple Peak forks. Tangles of downed trees here, the aftermath of a windstorm, limit camping options, but are an impressive sight. After meandering for a third of a mile through valley-bottom forest, the river splits again, with the Triple Peak Fork trending east, while you climb along the Merced Peak Fork; the mighty river has quickly divided into a collection of tributaries emanating from individual cirque basins at the cachement headwaters. For the next 0.7 mile, you continue southward up the river’s west bank through red fir and juniper, the gradient now sufficiently steep to necessitate an occasional switchback. You’ll undoubtedly sense that steep walls are suddenly encroaching upon you, and indeed after crossing the Merced Peak Fork on a bridge, the trail begins switchbacking up the exfoliating slab wall east of the river. In places, beautiful rock walls support the trail and elsewhere it follows natural passageways. At the end of a long switchback to the northeast you are treated to views of Triple Peak Falls along the Triple Peak Fork and then turn to the southeast to follow the drainage upward.

Looking down on the upper Isberg Lake basin Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

About a mile above the bridge the gradient starts to ease and forest cover returns, becoming denser as you pass a stock drift fence and turn due south. You are now in a lovely, long-hanging valley that the trail follows creekside for more than 2 miles. In places there are slabs right up to the banks, but mostly the Triple Peak Fork fills a deep, lazy channel that meanders down the middle of the verdant Triple Peak Fork Meadow. At the southwestern tip of the meadow are a number of good campsites, some among slabs west of the meadow and others in lodgepole forest near a junction with the westbound trail to Red Peak Pass (9,105'; 37.65847°N, 119.34456°W). Fishing is good for brook and rainbow trout.

DAY 4 (Triple Peak Fork Meadow to Sadler Lake, 7.2 miles): At the aforementioned junction, right (west) leads up to Red Peak Pass (Trip 63), while you turn left (east) and cross the creek on a convenient log—hopefully still present. Leaving behind the wonderful landscape of polished slabs, you ascend southward through dry lodgepole forest. The trail turns north after 0.7 mile and soon big hemlock trees garner your attention. The forested climb continues to a junction, where you are greeted by all-consuming views of the Clark Range and beyond. At this junction, you turn right (south) toward Isberg Pass, while left (north) leads to the headwaters of the Lyell Fork Merced along a route often referred to as the High Trail (Trip 55).

Your route skirts the side of steep granite bluffs and within steps a magical landscape emerges ahead—a strikingly flat, long shelf perched high on the mountain side. At the north end of this basin lies long, oval-shaped Lake 10,005 and a smaller companion. There is camping at the north end of the larger lake, set back from its sandy northern beach in the lodgepole forest. The trail itself skirts well west of the lakes, traversing straight across the expansive flower-dotted meadow—staring down you’ll see endless colorful dots, including diminutive lupines, cinquefoil, and daisies. This delightful stroll leads you back to steeper terrain, as you cross two small creeks, the first seasonal, the second spring fed and permanent, and begin climbing coarse decomposing granite.

A beautiful, lush slope of fell-field species leads to a junction, where you turn left (northeast) toward Isberg Pass, while right (southeast) leads to Post Peak Pass (Trip 68). It is only 0.6 mile from here to Isberg Pass and with only 250 feet of elevation gain, but it is the slowest stretch of trail on your route: at first you ascend a steep, loose trail across a steeper, looser slope and then begin winding between slabs and broken blocks. It is cumbersome walking, as on many occasions you climb a few steps downward to bypass a small obstacle. Finally you reach Isberg Pass (10,510'), dropping your pack atop beautiful polished slabs while gawking at the view—most immediately striking is the sawtoothed Ritter Range to the east, but much of southern Yosemite is laid out to the north and west, while to the southeast you are staring across the expansive San Joaquin River drainage.

The pass marks the boundary between Yosemite National Park and the Ansel Adams Wilderness. Leaving the park, you descend easier terrain to the northeast. The rock here is colorful—admire the red-and-gray-striped summit of Isberg Peak—because you are near the contact between granitic and metamorphic rock, and many of the granitic rocks on this slope were partially altered during long-ago geologic skirmishes. A long traverse leads to 26 tight but relatively gentle switchbacks down a south-facing rib. Soon the narrow, winding, often incised trail skirts upper Isberg Lake and passes two small tarns. The views are tremendous and the rocks engaging, dotted with inclusions, blobs of older, darker rocks engulfed in the lighter-colored granite. Verdant slopes are irrigated by endless trickles and wildflowers abound as you loop down a 300-foot slope to lower Isberg Lake. Fishing in these lakes is fair to good for brook and rainbow trout. The campsites around lower Isberg Lake are mostly tiny, with space for only a single tent in each sandy patch, for most of the ground is covered by sedge meadows and expanses of dwarf bilberry and red mountain heather.

The trail crosses a shallow rib and descends 500 feet down a steep slope sparsely covered with lodgepole pines. The landscape flattens abruptly where you reach the marshy north shore of Sadler Lake and the trail skirts east around the lake. Camping is only legal along the south and west sides of the lake; to reach them continue south until you come to a junction, located just where you feel you’re leaving the lake behind. Here a spur trail strikes west (right; 9,377'; 37.64194°N, 119.30058°W; no campfires), signposted for McClure Lake, after passing ample camping around Sadler Lake’s shores.

DAY 5 (Sadler Lake to Isberg Trailhead, 8.4 miles): Returning to the main Isberg Trail, turn right (south) and continue down. Leaving Sadler Lake’s shelf behind, the trail descends again, the lodgepole pine cover now denser, to a ford of East Fork Granite Creek. Its gradient easing, the trail follows the orange bedrock channel for a half mile before veering away from the creek and passing a junction where you continue left (southeast) down the main trail, while right (northwest) is a spur to Joe Crane Lake (Trip 67). The trail continues to descend, crossing several small creeks before it levels off in Knoblock Meadow.

Cross East Fork Granite Creek again, a ford at high flows, and skirt the meadow’s eastern edge, where you pass a few small campsites. Abundant tarns and marshy meadows make the ensuing miles a mosquito factory in June and July, but this stretch is correspondingly resplendent with water-loving wildflowers. The trail then swings south-southeast away from the creek to cross a low bedrock ridge and 1.2 miles past the ford reaches a junction with a little-used lateral left (east) toward Chetwood Creek. Staying right (southeast), it is an easy half mile over a low moraine down to an unmarked spur junction at the northeast corner of Middle Cora Lake, leading to campsites along the southwest shore (8,386'; 37.59755°N, 119.26961°W; Trip 67). Camping is prohibited, however, within 400 feet of the lake’s eastern shore, the corridor through which the trail passes. Note: from here to the trailhead, much of the landscape was burned in the 2020 Creek Fire, the flames still active as this book goes to press.

Onward, ford Middle Cora Lake’s outlet, and sidle around the east side of a small dome on slabs. Beyond, you drop more steeply into a lush tributary that you descend to its confluence with East Fork Granite Creek. Here you ford East Fork Granite Creek for the last time (wet feet in early season) and follow its bank downstream. Ignore a succession of old, unmarked trail treads that depart to the right, staying along the creek’s western bank. You reach a junction with the Stevenson Trail that leads east (left), back across the creek, bound for the Hemlock Crossing along the North Fork San Joaquin River (Trip 69).

Continuing downstream, sometimes through moist forest, other times along the creek’s riparian corridor, you reach a wonderful passageway, the Niche. Here the ridges to the east and west converge on the creek, whose channel narrows as it passes through this slot and then drops steeply on its journey south. With just over 2 miles remaining, the trail swings west to leave Ansel Adams Wilderness and descends a brushy slope before again turning south. Continue onward, following a seasonal tributary as you head down the increasingly dusty trail, which ends at a dirt road. Here you turn left (east) and walk just a few steps to a parking area on the south side of the road. Note this road, Forest Service Road 5S30, is not shown on USGS topo maps, making it difficult to visualize where you’ve just landed. The Isberg Trailhead is, however, correctly plotted on U.S. Forest Service maps (7,100'; 37.54710°N; 119.26610°W).