Chapter 18

Creativity within a Living World

The mystery of creativity

Evolution is an interplay between habit and creativity. If there were only habits, nothing really new would happen, although old habits could be shuffled and recombined. If there were only creativity there would be a dazzling display of novelty, but nothing would ever stabilize.

Formative causation accounts for the habits of nature. It explains the way in which patterns of organization are repeated again and again – for example, in the formation of haemoglobin molecules, in the growth of wheat plants, in the nest-building instincts of weaver birds – in terms of morphic fields sustained by morphic resonance from previous similar systems. But it does not explain how a new pattern of organization, such as a new kind of crystal, or a new instinct, or a new scientific theory, comes into being in the first place. These new patterns, these new holons, are new fields of activity. Where do these fields come from? How are they created?

Creativity is a profound mystery precisely because it involves the appearance of patterns that have never existed before. We usually explain things in terms of pre-existing causes: the cause somehow contains the effect; the effect follows from the cause. If we apply this way of thinking to the creation of a new form of life, a new work of art, or a new theory, we infer that the new pattern of organization was already present. But since it was unmanifested, it must have been a latent possibility. Given the appropriate circumstances, this latent pattern becomes actual. Creativity thus consists in the realization of this pre-existing possibility. In other words, the new pattern has not been created at all; it has only been manifested in the physical world, whereas previously it was unmanifested.

This is in essence the Platonic theory of creativity. All possible forms have always existed as timeless Forms, or as mathematical potentialities implicit in the eternal laws of nature: ‘The possible would have been there from all time, a phantom awaiting its hour; it would therefore have become reality by the addition of something, by some transfusion of blood or life,’ as Henri Bergson expressed it.1 He pointed out that this is the conception inherent in traditional European philosophies:

The ancients, Platonists to a greater or lesser degree … imagined that Being was given once and for all, complete and perfect, in the immutable system of Ideas; the world which unfolds before our eyes could therefore add nothing to it; it was, on the contrary, only diminution or degradation; its successive states measured as it were the increasing or decreasing distance between what is, a shadow projected in time, and what ought to be, Idea set in eternity. The moderns, it is true, take a quite different point of view. They no longer treat Time as an intruder, a disturber of eternity; but they would very much like to reduce it to a simple appearance. The temporal is, then, only the confused form of the rational. What we perceive as being a succession of states is conceived by our intellect, once the fog has settled, as a system of relations. The real becomes once more the eternal, with this simple difference, that it is the eternity of the Laws in which the phenomena are resolved instead of being the eternity of the Ideas which serve them as models.2

Platonic philosophy and the theories of mechanistic physics were conceived in the context of a non-evolutionary world. Eternal Forms or laws seemed appropriate in an eternal universe. But they are thrown into question by evolution, a process of creative development. Creativity may be real; new patterns of organization may be made up as the world goes along. Everything new that happens is possible in the tautological sense that only the possible can happen. But new forms of organization, which are only knowable after they actually come into being, do not imply a pre-existent reality transcending time and space.

In this chapter I consider different ways of thinking about the creativity of the evolutionary process; but it is important to recognize at the outset that none ultimately dispel the mystery. If we adopt a Platonic approach, we are left with the mystery of a transcendent realm of latent possibilities. If we accept that there is a genuine creativity in the evolutionary process, how can we explain it? We can attribute it to intelligences in nature, chance, life, or fields. But then we cannot explain why any of these should have the capacity to create new patterns of organization in the first place: we sooner or later reach the limits of our understanding. If we attribute creativity to divine powers or superhuman intelligences on the one hand, or to chance on the other, we reach these limits sooner; if we recognize that creative capacities are inherent in morphic fields themselves, we reach these limits later, but we reach them just the same.

I begin by considering the conception of creativity in mechanistic science before the theory of cosmic evolution.

How evolution brings nature back to life

When the mechanistic theory first came into being, it portrayed nature as inanimate, unconscious, machine-like, repetitive and uncreative. By contrast, God was the sole source of all the laws of nature, of all matter and motion, and of all the designs of plants and animals. Nature had no freedom or creativity. Nature was not creative; it was created.

In Europe before the seventeenth century, as in other parts of the world, nature was seen as alive; the world was animate, and so were all living beings within it. They had a life of their own, and expressed their own purposes. When nature was personified, she was the Great Mother. When she was depersonified by mechanistic science, she became matter in motion, still the source and substance of all things, but with no life or spontaneity; she was governed in every respect by the eternal laws of God the Father. The mechanistic philosophy treated the entire universe as inanimate3 (Chapters 2 and 3). In so far as plants and animals seemed to have purposive designs, they reflected the intelligence of the designer, the God of the world machine.

The theory of evolution by natural selection was a liberation from this external God. Creativity was inherent in life itself. For Charles Darwin, the source of evolutionary creativity was not beyond nature, in the eternal designs of a machine-making God, the God of Paley’s natural theology (Chapter 3). The evolution of life took place spontaneously within the material world. Nature itself, or herself, has given rise to all the myriad forms of life.

Darwin could not help personifying nature (see above). In personified terms, what his theory tells us is that Mother Nature, rather than the Heavenly Father, is the source of all life. The Great Mother is prodigiously fertile; but she is also cruel and terrible, the devourer of her own offspring. It was this destructive aspect of Nature that impressed Darwin so deeply, and in the form of natural selection he made it the primary creative power, ‘a power incessantly ready for action’.4

Thus in the light of the Darwinian theory of evolution, nature becomes creative, and takes on the attributes of the archaic Mother Goddess, from whose womb all life comes forth and to whom all life returns. When de-personified, she can simply be called nature, or matter, or life, or emergent evolution. Evolutionary creativity can be attributed either to the Great Mother herself or the de-personified abstractions that replace her.

In the dialectical materialism of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, matter was the creative source of everything and underwent a continual, spontaneous, dialectical development, resolving conflicts and contradictions in successive syntheses. But ‘matter’ in this sense had prodigious creative properties that the matter of Newtonian physics did not have. Permanent billiard-ball atoms had no power to create cells or chimpanzees or philosophical theories. Even the dynamic, self-organizing atoms of modern quantum physics have no such creative power. If we extend the meaning of the word matter to include not merely matter as physicists conceive of it but also fields and energy, and indeed all physical reality, then we might as well call it nature; though not the inanimate, uncreative nature of Newtonian physics, but the creative nature of an evolutionary world.

Henri Bergson attributed this creativity to the élan vital or vital impetus. Like Darwinians, Marxists, and other believers in emergent evolution, he denied that the evolutionary process was designed and planned in advance in the eternal mind of a transcendent God. Instead, evolution was spontaneous and creative:

Nature is more and better than a plan in course of realization. A plan is a term assigned to a labour: it closes the future whose form it indicates. Before the evolution of life, on the contrary, the portals of the future remain wide open. It is a creation that goes on forever in virtue of an initial movement. This movement constitutes the unity of the organized world – a prolific unity, of an infinite richness, superior to any that the intellect could dream of, for the intellect is only one of its aspects or products.5

The neo-Darwinian theory of evolution shares this vision of evolution as a spontaneous, creative process. As the molecular biologist Jacques Monod put it in his book on the neo-Darwinian world view, Chance and Necessity, ‘evolutionary emergence, owing to the fact that it arises from the essentially unforseeable, is the creator of absolute newness.’6 What Bergson attributed to the élan vital, Monod ascribed to ‘the inexhaustible resources of the well of chance’,7 expressed through random mutations in DNA.

In Monod’s conception, the creative role of chance, of that which is indeterminate, is expressed in its interplay with necessity, that which is determinate. Here again, it is illuminating to see what happens when these abstract principles are personified. Just as nature becomes the Great Mother, they too come to life in the form of goddesses. In pre-Christian Europe, Necessity was one of the names for Fate or Destiny, often represented by the Three Fates, the stern spinning-women who spin, allot, and cut the thread of life, dispensing to mortals their destiny at birth. This ancient image is paralleled in neo-Darwinian thinking in a curiously literal manner. The thread of life that determines an organism’s genetic destiny consists of the helical DNA molecules arranged in thread-like chromosomes.

On the other hand, Chance is one of the names of the goddess Fortune. The turnings of her wheel, the Wheel of Fortune, confer prosperity and misfortune. She is the patroness of gamblers; another of her names is Lady Luck.8 The goddess Fortuna is blind. And so is chance. In Monod’s words:

Chance alone is at the source of every innovation, of all creation in the biosphere. Pure chance, absolutely free but blind, at the very root of the stupendous edifice of evolution: this central concept of modern biology is no longer one among other possible or conceivable hypotheses. It is today the sole conceivable hypothesis, the only one compatible with observed or tested fact. And nothing warrants the supposition (or the hope) that conceptions about this should, or ever could, be revised.9

However, the realm in which chance and necessity hold sway is only one aspect of the mechanistic worldview. The other is the Platonic realm of eternal Forms, laws, or mathematical formulae. Some biologists prefer to see this realm, rather than the workings of blind chance, as the source of all new forms of life. The evolution of dinosaurs or starfish or palm trees represents the manifestation of pre-existing non-material archetypes (see above). These archetypes themselves cannot evolve; they are beyond time and space. Either they are ideas in the mind of God, or, if we dispense with God, they have an independent mathematical existence inexplicable in terms of anything else.

Thus neo-Darwinism leads to an impasse. In so far as evolutionary creativity depends on the manifestation of eternal Forms or principles of order, it is not true creativity at all, but only the manifestation of patterns that have always existed in a non-material mathematical realm. And in so far as creativity depends on blind chance, it is essentially unintelligible, and we have to leave it at that.

In Europe, the transcendent realm was traditionally regarded as the province of the Heavenly Father and the material realm the province of the Great Mother. In these personified terms, Platonism stresses the rational, male creative principle, and materialism the non-rational, female aspects of creativity. Do these personified archetypes represent a deeper way of understanding the mystery of creativity than the abstractions of modern thought? Or are impersonal abstractions a higher form of understanding than primitive, personified modes of thought found in myths and religions? However we choose to see it, archaic and modern ways of explaining creativity show striking parallels.

The evolutionary philosophy of organism allows us to go further. The organizing principles of nature are not beyond it, in a transcendent realm, but within it. Not only does the world evolve in space and time, but the immanent organizing principles themselves evolve. According to the hypothesis of formative causation, these organizing principles are morphic fields.

Fields have inherited many of the properties ascribed to souls in the pre-mechanistic philosophies of nature. The growth of field theories is another way in which nature has been coming back to life.

Fields, souls and magic

What the mechanistic philosophy of the seventeenth century rejected, and what mechanists still reject, is the idea that the world and all living beings within it are animate; or in other words that they are organized by non-material souls, or animas, or psyches.

Aristotle and neo-Platonic philosophers like Plotinus worked out the idea of animating souls in systematic detail, and Thomas Aquinas laid the foundations of the theory of souls taught throughout Europe in the medieval universities. Souls pervaded much Renaissance philosophy, and persisted into the twentieth century in vitalist biology. They have been revived in a modern evolutionary form in the holistic philosophy of organism. In this process, souls as purposive organizing principles have been replaced by organizing fields, organizing relations, principles of self-organization, mind in nature, patterns that connect, the implicate order, information, systems properties, developmental attractors, and organizing principles under other names.

From a mechanistic point of view, traditional animism and modern organicism both involve an invalid projection of the human purposes onto the inanimate world around us. In Monod’s words, animist belief, in which he included both organicism and dialectical materialism, ‘consists essentially in a projection into inanimate nature of man’s awareness of the intensely teleonomic functioning of his own nervous system’.10

This kind of projection would inevitably result in delusion if nature were inanimate and mechanistic. But this begs a question, for it leaves unexplained the intensely teleonomic functioning of our nervous systems themselves, the teleonomy of all living organisms, and the self-organizing properties of natural systems at all levels of complexity.

Ironically, the mechanistic approach itself seems to be more anthropomorphic than the animistic. It projects one particular kind of human activity, the construction and use of machines, onto the whole of nature. The mechanistic theory derives its plausibility precisely from the fact that machines do have purposive designs whose source is in purposive minds – the minds of their human creators and users.

Classical physics is replete with terms that imply correspondences between human life and the realm of nature, words whose animistic associations have long been unconscious: for example law, force, work, energy, and attraction. Quantum physics has mischievously added more, such as charm. And in biology too we find explanatory terms that do not properly belong in an inanimate world: function, adaptation, selection, information, selfish genes, genetic programs, and so on.

Mechanistic science developed against an animistic background, in a world where magic was taken seriously. A number of ancient magical conceptions are surprisingly similar to essential elements of classical and modern physics. In this connection, the following discussion by the anthropologist James Frazer is particularly interesting:

If we analyse the principles of thought on which magic is based, they will probably be found to resolve themselves into two: first, that like produces like, or that an effect resembles its cause; and second, that things which have once been in contact with each other continue to act on each other at a distance after the physical contact has been severed. The former principle may be called the Law of Similarity, the latter principle the Law of Contact or Contagion. From the first of these principles, namely the Law of Similarity, the magician infers that he can produce any effect he desires merely by imitating it: from the second he infers that whatever he does to a material object will affect equally the person with whom the object was once in contact, whether it formed part of his body or not … The same principles which the magician applies in the practice of his art are implicitly believed by him to regulate the operations of inanimate nature; in other words, he tacitly assumes that the Laws of Similarity and Contact are of universal application and not limited to human actions.11

Physicists, like Frazer’s magicians, gain their power by imitating nature: but they do not do it by making material models, like wax dolls, but by making mathematical models. Not all the models they make are successful. But the successful ones seem to correspond in some mysterious way to aspects of the physical world, and by virtue of these models scientists can gain powers to predict and control. Such models lie at the heart of all modern technologies. In the light of the non-locality or entanglement inherent in quantum theory the Law of Contact has also taken on a new significance: separated parts that were once in contact remained linked to each other at a distance; a change in one entangles the other.

Like the world of the magician, the world of the physicist is full of unseen connections traversing apparently empty space. As Frazer put it, the laws of magic assume that things act on each other at a distance through a secret sympathy, the impulse being transmitted from one to the other by means of what we may conceive as a kind of invisible ether, not unlike that which is postulated by modern science for a precisely similar purpose, namely, to explain how things can physically affect each other through a space which appears to be empty.12

Now fields themselves, rather than fields of ether, are thought to be the medium of the secret sympathies of nature.

According to the old animistic philosophies, the soul of the world, and the souls of all beings within it were immutable. They influenced the matter with which they were associated, but they did not evolve; they stayed the same. Until very recently the fields of physics were thought of in a similar way. They stayed the same: their nature was not changed by the energy they contained and organized or by what happened within them. But now they have histories.

As we saw in Chapter 17, contemporary theories of the evolution of physical fields uneasily straddle two very different paradigms: the traditional conception of eternal mathematical laws and the idea of the universe as a vast evolving organism. Are the mathematical structures of a grand unified theory or superstring theory more real than the fields through which they are manifested in space and time? Or are the fields more real than the mathematics by which they are described and modelled?

If mathematical laws are more real than fields, then the ultimate reality is still in the transcendent realm of eternal Ideas or laws. This is what most physicists have always assumed. If, on the other hand, fields are more real than mathematical models, we are in an evolving universe whose organizing principles are evolving too.

Creative morphic fields

The evolution of organizing fields is an unfamiliar idea. It is alien to traditional animism, alien to the traditions of physics, and alien to the mechanistic philosophy. If fields evolve, it is no longer appropriate to think of them in terms of immutable essences or changeless laws; nor does the concept of blind chance seem sufficient to explain the appearance of such integrated structures of ordering.

Before we explore in more detail the possible roles of morphic fields in evolutionary creativity, let us recall the hypothetical properties of these fields at all levels of complexity:

- They are self-organizing wholes.

- They have both a spatial and a temporal aspect, and organize spatio-temporal patterns of vibratory or rhythmic activity.

- They attract the systems under their influence towards characteristic forms and patterns of activity, whose coming-into-being they organize and whose integrity they maintain. The ends or goals towards which morphic fields attract the systems under their influence are called attractors. The pathways by which systems usually reach these attractors are called chreodes.

- They interrelate and co-ordinate the morphic units or holons that lie within them, which in turn are wholes organized by morphic fields. Morphic fields contain other morphic fields within them in a nested hierarchy or holarchy.

- They are structures of probability, and their organizing activity is probabilistic.

- They contain a built-in memory given by self-resonance with a morphic unit’s own past and by morphic resonance with all previous similar systems. This memory is cumulative. The more often particular patterns of activity are repeated, the more habitual they tend to become.

In the course of this book, the question of creativity has been left open. In an attempt to address it, I first examine how creativity is expressed within existing morphic fields and then consider how entirely new fields might originate.

The kind of creativity expressed within the context of already existing morphic fields is creativity in a weak sense of the word. The end-points or goals or attractors given by the fields remain the same; what are new are the ways of reaching them. This kind of creativity is commonly expressed by words such as adaptability, flexibility, ingeniousness, and resourcefulness. The appearance of entirely new fields with their new goals or attractors involves a higher order of creativity or originality.

The main reason that developmental biologists proposed the idea of morphogenetic fields in the first place was because organisms can retain their wholeness and recover their form even if parts of them are damaged or removed (Fig. 5.3). The field in some sense contains the virtual form or pattern of the entire morphic unit, and it attracts the developing or regenerating system towards it. If the process of development is displaced from its normal pathway, it can return to it, just as a ball pushed up the side of a hill can roll back into the valley and rejoin the usual canalized pathway of change in Waddington’s model of a chreode (Fig. 6.2).

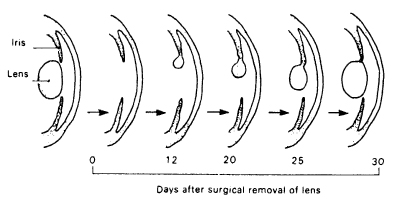

In all processes of regulation and regeneration, the developmental process adjusts in such a way that a more or less normal structure of activity is regained by a more or less new route. In other words, there is an element of novelty or creativity in the developmental process. A striking example is the way in which a newt’s eye regenerates after the surgical removal of its lens. In normal embryonic development the lens develops from an infolding of the embryonic skin tissue that overlies the developing eye; but in response to the removal of the lens from an eye that is already mature, a new lens arises from the edge of the iris (Fig. 18.1).

Figure 18.1 Regeneration of a lens from the margin of the iris in a newt’s eye after the surgical removal of the lens. (Cf. Needham, 1942)

Many further examples of regulation or adjustment are provided by the way in which developing organisms respond to genetic mutations. Mutant organisms are not merely the product of mutant genes: they are the result of developmental processes that have adjusted to the new internal conditions in such a way that integrated organisms are still produced, even if they are abnormal in various ways. In so far as random mutations are a source of evolutionary creativity, the creativity is inherent not so much in the chromosomal and genetic changes as in the ways that organisms respond and adjust to them: it is an expression of the organizing activity of the morphic fields.

Charles Darwin explicitly recognized just such a holistic organizing principle, which he described as a ‘co-ordinating power’:

[W]hen any part or organ is either greatly increased in size or wholly suppressed through variation and continued selection, the co-ordinating power of the organisation will continually tend to bring again all the parts into harmony with one another.13

Environmental changes, like genetic mutations, impose new necessities on organisms. Necessity is the mother of invention: but the inventions themselves are made by organisms. The adjustment of the form and function of plants and animals to the conditions of life, their adaptation to the environment, occurs in countless ways. Such purposive adaptations, which so impressed both Lamarck and Darwin, tend to become increasingly hereditary and habitual the more often they are repeated, and are a major source of creativity in the evolutionary process.

Likewise, in the realm of behaviour, we find comparable abilities to adjust creatively to genetic mutations, to damage, and to change in the environment. Animals born with abnormal bodies sometimes manage to survive through appropriate adjustments of their movements and behaviour. Creatures that have lost a limb or some other structure often adjust to the damage more or less effectively: for example a dog can learn to run on three legs, and blind people develop ways of finding their way around by relying on other senses. Termites can repair damage to their nests. If obstacles are put in the path of animals or of people who want to get somewhere, they may find a way round the obstacle and get there by a different route. Animals and people transferred to new and unfamiliar environments often adjust more or less appropriately.

Of course, not all kinds of mutation, damage, and environmental change elicit successful responses. Many are immediately lethal. Others are too extreme for adaptation to occur successfully. But within certain limits, innovative responses occur at all levels of organization. Morphic fields appear to have an inherent creativity, which is recognisable precisely because the new pathways of development or behaviour often seem so adaptive and purposeful.

To some extent, every individual organism and every element of its structure and behaviour represents a creative response to its internal and external conditions. No two organisms of the same kind are exactly identical; they are in different places, in different microenvironments, made up of different atoms and molecules, and subject to chance fluctuations from the quantum level upwards. Morphic fields are not rigid; they are probability structures and bring about their ordering effects through a probabilistic influence; they have an inherent flexibility. They encompass the uniqueness of individual morphic units within a field of probability that defines the structure and the limits of the type; they are, in the language of dynamics, attractors or basins of attraction.

‘Where there’s a will, there’s a way.’ The will is given by the goal or attractor, which lies in the virtual future. The progress of a system towards its morphic attractor involves adjustments, great and small, of its component parts and their interrelationships; it finds a way. In so far as it is prevented from following the usual, habitual path, it may find a more or less new way of reaching the same goal.

Much human creativity is of this general type: it involves finding new ways to achieve habitual goals or ends – inventive ways of saying or doing or making things; ingenious ways of repairing things; the solving of puzzles and problems; the making of better mousetraps.

The finding of new ways is different in degree from the process by which we learn our usual ways of behaving, speaking, and thinking, but it does not differ in kind. When we learn anything at all, success depends on doing it in a manner that is adapted to our own bodies, skills, and circumstances. And every time we do something, or speak, or think, our habits adjust themselves more or less well to the conditions on that particular occasion. A great deal of this adjustment is unconscious. But even when we use our conscious minds to adjust, adapt, find a new way, or solve a problem, we generally find it hard to say how we did it. The answer just comes, it happens, we stumble upon it, or the penny drops. It is as if the new ways come through consciousness; but the creative processes themselves are unconscious, beneath or behind our awareness.

The inherent tendency of systems to find a way to their morphic attractors, or to find a way back to them, is also expressed in the context of social and cultural fields. The co-ordinated behaviour of social insects such as bees, for example, is organized by the morphic fields of the society; and if the hive is damaged and members of the colony are killed, the behaviour of the surviving insects is often regulated in such a way that the damage is made good and the harmonious functioning of the colony is restored. The adjustment of human families, communities, and larger societies to accidents, loss of life, external or internal threats, disturbances, and calamities seems comparable: individuals respond as the collective field adjusts to the new conditions and progressively restores the society to a co-ordinated integrity.

These fields work through their influence on the people within them. Some people may have more awareness than others of what needs to be done, and leaders of various kinds generally have the ability to communicate it. Both this awareness and people’s responses to it are influenced by the collective field and are not just the product of separate, individual minds. Nor do rulers, patriarchs, matriarchs, shamans, prophets, priests, leaders, or other persons of authority claim that they are speaking merely as individuals: they do so under the aegis of the gods or guardian spirits or ancestors, or the values or traditions of the group, for the sake of the whole group’s life and survival.

Habit and creativity

The idea underlying the preceding discussion is that morphic fields have an inherent creativity. The idea emphasized in earlier chapters of this book is that they are habitual in nature. These two aspects of fields are complementary, rather than contradictory. Morphic fields contain goals or attractors that are indeed habitual and conservative; the creativity that occurs within them involves finding new ways of reaching these goals. The expression of any habitual pattern of development or activity requires flexibility; habits could not be viable without a creative adaptation to circumstances.

Nevertheless, as fields evolve and as habitual chreodes become established within them, there is a sense in which their inherent creativity is reduced. The evolutionary radiations or explosive phases that seem to occur fairly early in the history of a new phylum, order, family, genus, or species involve various differentiations or adaptations of the ancestral form (Chapter 16). Comparable explosive phases may have occurred in the evolution of patterns of instinctive behaviour, as well as in the evolution of human languages and social, political, and cultural forms. Similar processes occur in the evolution of religions, arts, and sciences when distinct sects, schools, and traditions arise within them. In the realm of technology, there is often a comparable proliferation of versions and models following the invention of a new kind of machine: think, for example, of the variety of cars on the market, or the variety of mobile phones.

There is an obvious reason why the appearance of new variations on basic themes tends to become less frequent as time goes on: the number of possible variant forms is finite. As new versions appear and either die out or become increasingly habitual, there are progressively fewer remaining potentialities that have not already been explored.

However, no amount of creativity expressed within the context of any morphic field at any level of complexity can explain the appearance of a new field itself for the very first time.

The origin of new fields

The appearance of a new kind of field involves a creative jump or synthesis. A new morphic attractor comes into being, and with it a new pattern of relationships and connections. Consider a new kind of molecule, for example, or a new kind of instinct, or a new theory.

One way of thinking about these creative syntheses involves looking from below, from the bottom up: we then see the ‘emergence’ of ever more complex forms at higher levels of organization. The progressive appearance of new syntheses is elevated to a general principle in dialectical materialism and in other philosophies of emergent evolution. Evolution then becomes more than a word describing a process; it involves a creative principle inherent in matter, or energy, nature, life, or process itself. New patterns of organization, new morphic fields, come into being as a result of this intrinsic creativity. But why should matter, energy, nature, life, or process be creative? This is inevitably mysterious. Not much more can be said than that it is their nature to be so.

Another approach is to start from above, from the top down, and to consider how new fields may have originated from pre-existing fields at a higher and more inclusive level of organization. Fields arise within fields. For example, a new habit of behaviour, such as the opening of milk bottles by tits (Fig. 9.5), involves the appearance of a new morphic field. From the ‘bottom up’ point of view, this must have emerged by the synthesis of pre-existing behavioural patterns, such as the tearing of strips of bark from twigs, in a new, higher-level whole. From the ‘top down’ point of view, this new field arose in the higher-level, more inclusive morphic field that organizes the searching for food and all the activities involved in feeding. This higher-level field may somehow have formed within itself a new lower-level field, that of milk-bottle opening.

This creative process is interactive in the sense that the higher-level fields within which new fields come into being are modified by these new patterns of organization within them. They have a greater internal complexity, which is the context in which the further creation of new fields within them is expressed.

These principles may well apply at all levels of organization, from new kinds of protein molecules that have arisen within the fields of cells to galaxies within the field of the growing universe. In every case, the higher-level fields are influenced by what has happened in the past and what is happening within them now; their creativity is evolutionary.

Ultimately this way of thinking leads us back to the primal morphic field of the universe as the ultimate source and ground of all the fields within it. In the context of modern evolutionary cosmology, this is the original unified field from which all the fields of nature were derived as the universe grew and developed.

In summary, we can either think of the creation of new fields as an ascending process, with new syntheses emerging at progressively higher levels of organization, or we can think of it as a descending process, with new fields arising within higher-level fields, which are their creative source. Or, of course, we can think of evolutionary creativity as a combination of these processes.

The primal field of nature

What could the idea of a primal, unified, universal field possibly mean?

The sceptic in all of us is inclined to think that it doesn’t mean much. It is just another speculative theory that takes us beyond anything that we can directly observe. We are leaving empirical science behind us and entering the realm of metaphysics. There is no point in going further, for we will only enmesh ourselves in tangled webs of speculation.

If we do want to go further, we have to recognize that we are indeed in the field of metaphysics. For more than two and a half millennia, philosophers have discussed the source of pattern and order in the world, the nature of flux and change, the nature of space and time, and the relation of the changing world of our experience to eternity and changelessness. In one major tradition, rooted in the cosmology of Plato, these questions have been answered in terms of the anima mundi, the world soul. The cosmos was contained within the world soul, which in turn was contained within the mind of God, the realm of Ideas beyond both time and space. The world soul differed from the realm of Ideas in that it had within it time, space, and becoming. It was the creative source of all of the souls within it, just as in modern theoretical physics the ten- or eleven-dimensional primal unified field is the source of all the fields of evolutionary nature.

Just as the notion of the primal field raises the question of its relationship to eternal laws, so the notion of the world soul raised the question of its relationship to eternal Ideas. For the neo-Platonic philosopher Plotinus, these Ideas dwelt within what he called the Intelligence. The Intelligence differed from the Soul in possessing perfect self-awareness, and in contemplating the Forms themselves rather than images of the Forms. Just as the Intelligence ‘like some huge organism contains potentially all other intelligences,’ so the Soul contains potentially all other souls:

From the one Soul proceed a multiplicity of different souls … The function of the Soul as intellective is intellection. But it is not limited to intellection. If it were, there would be no distinction between it and the Intelligence. It has functions besides the intellectual, and these, by which it is not simply intelligence, determine its distinctive existence. In directing itself to what is above, it thinks. In directing itself to itself, it preserves itself. In directing itself to what is lower, it orders, administers, and governs.14

Below the influence of the Soul ‘we can find nothing but the indeterminateness of Matter’.15 But at all levels of existence the contents of the world are organized by souls; none are entirely indeterminate or inanimate:

The whole constitutes a harmony, in which each inferior grade is ‘in’ the next above … The bond of unity between the higher and lower products of Soul is the aspiration, the activity, the life, which is the reality of the world of becoming.16

However we interpret the similarities and differences between the old idea of the world soul and the new idea of the primal unified field, both inevitably raise the further question of their own origin and the source of the activity within them. The world soul was traditionally believed to arise from and to be contained within the being of God. Most contemporary physicists believe that the primal field is in some sense contained within or arises from eternal, transcendent laws. But then what is the source of these laws? How could transcendent, non-physical laws have given rise to the physical reality of the universe?

We may, of course, simply regard the origin of the universe and the creativity within it as an impenetrable mystery and leave it at that. If we choose to look further, we find ourselves in the presence of several long-established traditions of thought about the ultimate creative source, whether this is conceived of as the One, Brahma, the Void, the Tao, the eternal embrace of Shiva and Shakti, or the Holy Trinity.

In all these traditions, we sooner or later arrive at the limits of conceptual thought, and also at a recognition of these limits. Only mystical insight, contemplation or enlightenment can take us beyond them.