We hope you enjoyed the book. In this section, we have reproduced each of the diagrams in the book so that you can access them in one place. (Below the title of each diagram we reference the chapters in the book where the diagram is explored.) In a few cases, we present the diagrams in a slightly different form, with appropriate explanations. We also provide some additional thoughts and thought questions regarding each diagram. Following this section, we include two “Going Deeper” sections that take some of the ideas in the book to a deeper level. In those sections we have added for your consideration two diagrams that are not included in the book.

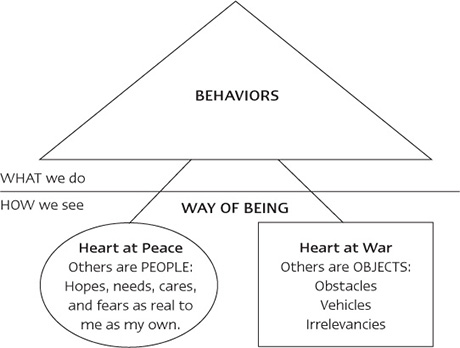

The Way-of-Being Diagram

(See chapter 4, “Beneath Behavior.”)

The Way-of-Being Diagram is formed through a combination of two distinctions. The first distinction is between our behavior and our way of being—that is, between what we are doing on the one hand and how we see others while we are doing what we are doing on the other. The diagram then draws a second distinction within our way of being: we can see others either as people, who matter like we ourselves matter, or as objects that don’t matter like we matter. When we see others as counting like we ourselves count, our hearts are at peace. When we see others as not counting like we count, our hearts are at war.

One of the important points illustrated by this diagram is that getting behavior right is only half of the story. There is almost nothing so common, for example, as people engaging in otherwise good or helpful behavior while mad at those they are doing it for. People who have done this before, and who have been upset at others’ responses to them, know that good behavior is undercut by a poor way of being—every time.

Another important issue is that way-of-being-level problems cannot be solved merely by behavioral solutions. The problem of sexual assault is an example of this. The military, for instance, has made a big push to eradicate this terrible crime. Until now, however, most of the well-meaning efforts to address the problem have been behavioral in nature. This doesn’t make these efforts wrong, per se, but it does make them incomplete. A person who sexually abuses another sees that person as an object. Unless the problem of objectification of others is solved, sexual assaults will not be curbed, no matter the behavioral efforts to address the issue.

In business, a company’s survival depends on its being behaviorally competitive. That is, if what it sells and what it does to produce its products and bring them to market are not sufficiently competitive, the company will go out of business. At the level of what they are doing, the market forces competitors to catch up with each other’s innovations in order to survive. So over time, at the level of the what, competitors end up resembling each other. (Consider how the products and services in most competitive industries—medicine, consumer electronics, automobiles, and so on—more or less resemble each other.) This implies that lasting competitive advantage is not a function of the what but a function of the how. A company that operationalizes seeing others as people sees differently in a way that allows it to achieve a competitive advantage. The gulf between its own performance and its nearest competitors’ cannot be bridged merely by mimicking the company’s behavior. Competitors have to be willing to give up all the objectifications of others that have, until that moment, characterized their enterprises. From strategy to internal processes and systems to customer service, competitors have to be willing to see others as people, with all that implies, to cross the chasm. This is why lasting competitive advantage is a function of the how.

Consider how common it is to inadvertently ignore the issue of way of being. When faced with difficult situations, we often ask, What should we do to handle this? The question sends us searching for only behavioral solutions. As with the problem of sexual assault discussed above, way-of-being-level problems cannot be solved by behavioral solutions alone. Individuals and organizations that realize and act upon this understanding are able to achieve much higher levels of performance than those that don’t.

You may find it helpful to ask questions that keep you aware of the importance of our way of being.

For example, in your opinion, do the other people at work matter like you matter? What would others say about how you see them?

How about at home? Do the things that matter to your family members matter as well to you? Are you aware of their needs as much as you are of your own?

Are the strategies, systems, and processes in your company built upon the assumption that people are people or on the assumption that people are objects?

For each of your relationships, is your heart mostly at peace or mostly at war? What do you need to do to improve any of those relationships?

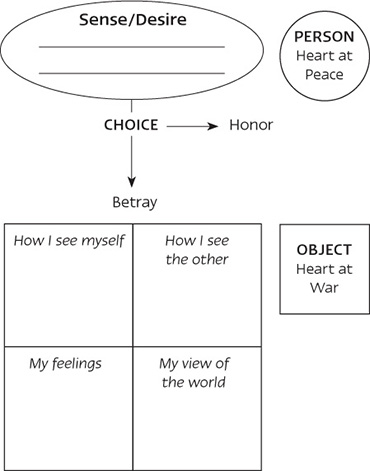

The Choice Diagram

(See chapters 10, “Choosing War”; 11, “A Need for War”; 14, “The Path to War”; and 21, “Action.”)

The Choice Diagram illustrates how we go into the box and shift from seeing others as people to seeing them as objects. When we see others as people, from time to time we will have impressions of appropriate things to do for others. When we are seeing others as people and see that they are in need, for example, we will naturally desire to do something to help them if we can. This was the Yusuf and Mordechai situation in the book.

Such situations present us with a choice. We can act on the sense to help, or, like Yusuf, we can resist or betray this sense. The diagram illustrates how, when we betray this sense, we go into the box and justify ourselves. You will see this is the case by testing this diagram with your own stories. Think of a time when you resisted a sense to help someone in some way. Write that sense in the oval at the top of the diagram. Then think about how you started to see this other person after you betrayed this sense to help. List the ways you started to see the person in the upper right quadrant of the box. Then think of how you started to see yourself after you betrayed this sense, and list those responses in the box’s upper left quadrant. You can also add the kinds of feelings you experienced after you betrayed yourself as well as how you viewed the world. After you have completed those quadrants, ask yourself, Do these thoughts and feelings invite me to go back and do what I was originally feeling I should do? If the answer to this question is no, this is likely an example of what we call self-betrayal, with the hallmark sign of feeling justified.

Pay attention to the senses you have to help others, and see what happens as you try to honor those senses.

Use this diagram to record an example of self-betrayal from your own life. After you have done so, look at the upper-right quadrant of the box and ask this question: After I betrayed myself, is this person now a person or an object to me? Then look at the upper-left quadrant and ask the same question about yourself: After I betrayed myself, am I seeing myself as a person or an object? (As you think about this question, you can consider it this way: Do the things I’ve listed about myself really capture who I am, or is this characterization of myself only half of a picture?)

What about when you have a sense to do something for yourself but don’t do it? For example, what if you have a sense to work out but then don’t do it? Could this also be a self-betrayal? Use the diagram to explore that kind of example as well. How do you end up seeing others? How do you end up seeing yourself? What kinds of feelings do you have, and so on? Do you feel justified at the end of the story? All things considered, does this seem like a self-betrayal or not?

Pay attention to the kinds of things that show up in the two left-hand quadrants of the box in your stories. Do the ways you see yourself and your emotions seem more like better-than symptoms or worse-than symptoms? Do you see any I-deserve or need-to-be-seen-as justifications? If so, consider what those boxes might do to others. How might they invite others to respond to you for example?

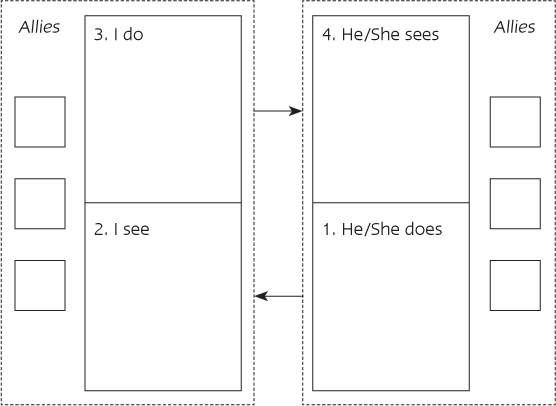

The Collusion Diagram

(See chapters 5, “The Pattern of Conflict,” and 6, “Escalation.”)

The Collusion Diagram illustrates how one person in the box invites others to get in the box in response. In addition, the diagram shows how when two parties are in the box toward each other, they each invite the very mistreatment they are blaming the other party for! This raises the question of why we would ever do that. Why would we ever invite others to do the very things we are complaining about? The answer is that when we are in the box, we have a need that trumps all others: the need to be justified. While we complain about what the other party is doing, his or her mistreatment of us gives us justification for our mistreatment of that person. Each party gives the other reason to keep doing exactly what he or she is doing.

This has a haunting implication: When we are in the box and have the need to feel justified, being justified becomes more important to us than being successful or happy. We don’t believe that this is true when we are in the box, of course. And it seems crazy even to say it. However, you can test this premise with any collusion situation.

You can use this diagram to chart a situation. Think of someone you are in the box toward. Write the person’s name on the line in the middle of the box on the right. Then write your name on the middle line in the left-hand box. Then in quadrant 1 list something the person does that bothers you when you are in the box—something you wish he or she would quit doing. In quadrant 2 list how you see this person and what he or she is doing when you are in the box. In quadrant 3 list the kinds of things you do in response when you are seeing the person in the ways you listed in quadrant 2. Finally, do your best to put yourself in the other person’s shoes. Ask yourself this question: If the other person is in the box toward me, how is he or she likely to see me and what I am doing? Write your responses to this question in quadrant 4.

Once you have filled in each of the quadrants, consider this question: If the person is seeing you in the ways you’ve listed in quadrant 4, is he or she likely to do less or more of the behaviors you listed in quadrant 1? If the answer is “more,” it suggests that you are inviting the very things you are complaining about and that justification is therefore more important to you than solution. That may sound crazy. Then again, to be in the box is to be a bit crazy.

The other point to notice about collusion is that we often gather allies to our side to bolster our justification claims. Although we may like the people we are gathering, we are not really seeing them as people when we gather them. Rather, we are valuing them as vehicles that help us feel right in our positions.

Finding collusions is very easy. All you have to do is think of something that someone else is doing that bothers you—something you wish he or she would quit doing. Write that person’s name in the box on the right and whatever he or she is doing that bothers you in quadrant 1. Then move to quadrant 2 and then 3 and then 4. Once you have filled in quadrant 4, you can tell whether you have a collusion by whether the items you listed in quadrant 4 lead to more of what you listed in quadrant 1.

Whom do you think you may be in collusion with in your work life?

Whom do you think you may be in collusion with in your family life?

For each of the collusions you can identify, whom have you gathered as allies?

One strategy for breaking a collusion is to do the following: Assume that you are out of the box. Then, when you get to quadrant 2, ask, If I weren’t in the box, how might I see this person and the things he or she is doing in quadrant 1? Write your responses to that question in quadrant 2. Then ask, If I were seeing this person in the ways I’ve listed in quadrant 2, how might I act toward him or her? Write those responses in quadrant 3. What you will likely find is that your responses in quadrants 2 and 3 when you ask these questions are entirely different from your responses when you filled in the Collusion Diagram before. Seeing and acting in these different ways will be the way out of the collusion.

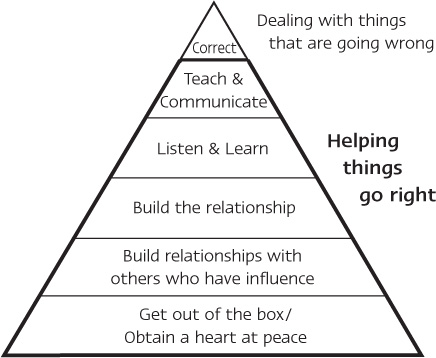

The Influence Pyramid

(See chapters 2, “Deeper Matters,” and 22, “A Strategy of Peace.”)

The Influence Pyramid is a strategic framework for helping other people to change. We can think of the pyramid as something we are always living from the bottom up. Then, when things are going wrong, we can locate what we need to do to help things go right by thinking from the top of the pyramid down.

The SWAT teams of a major metropolitan police department, for example, use this structure as a guiding framework for their work. SWAT teams usually engage in the community at the top level of the pyramid—correction. They break into homes, they issue arrest warrants, they work to resolve hostage situations, and so on. Since they began operationalizing the pyramid from the bottom up on a day-to-day basis, and applying the pyramid from the top down in all of their interventions, the SWAT teams have seen dramatically improved results. Since structuring their work this way, they have recovered guns and drugs at almost double the rate as before and in such a way that the number of complaints filed against them by members of the community has plummeted. It turns out that people whose homes are broken into by the police respond much better when the police are seeing and regarding them as people. Instead of just taking corrective actions, as had been their approach in years past, now, after establishing safety, the teams quickly move down the pyramid—teaching and communicating, listening and learning, building relationships, and so on. Instead of turning streets and neighborhoods against them, they build relationships in the community that strengthen their ability to help.

In a situation that inspired the story shared by Yusuf on page 219 of the book, a father who didn’t like the boy his daughter was dating did what many fathers in such situations do—he kept asking his daughter why she was dating such a loser. Not surprisingly, the more he tried to correct her, the more she became attached to the boy. When the father began considering this situation with the Influence Pyramid in mind, he realized that to help the situation go right, he needed to start spending more time at the lower levels of the pyramid. He realized that one of the areas he had been completely neglecting was building relationships with others who have influence with his daughter. He knew he needed to try to build a relationship with this boy. So the next time the boy came to get his daughter, this father invited him in. The next time he invited him to stay for dinner, and so on. Then two very interesting things happened. The first was that this father actually started to like the boy! The second was that his daughter decided that she didn’t like the boy anymore.

The Influence Pyramid gives very helpful guidance in difficult situations. As discussed in the book, three lessons help in its application. First, most time and effort should be spent at the lower levels of the pyramid. Second, the solution to a problem at one level of the pyramid is always below that level of the pyramid. And third, one’s effectiveness at each level of the pyramid ultimately depends on the lowest level of the pyramid—one’s way of being.

Think of someone you wish would change in some way. The first thing to do would be to consider why you want the person to change. For example, do you want the person to change because it will help you or because it will help him or her? This is a pretty good indicator of one’s way of being.

Look at the pyramid and identify the areas of the pyramid where you probably should be spending more time and effort regarding this person. What might you do to improve your efforts in those areas?

What is the state of your relationship with this person and with others who have influence with this person?

Have you really been listening to this person? Are you open to learning from him or her?

How has your communication been with this person? What might you do to improve it?