As the iconic band the Grateful Dead famously sang, “What a long, strange trip it’s been.”

I have been blessed by a career that began with a focus on interpersonal, team, and organizational communication. Through a series of fortuitous events, over thirty years ago I made the transition from public relations, employee newsletters, and speechwriting to leadership education, executive coaching, and organizational development. I began helping individuals, teams, and organizations learn how to collaborate in creating their desired outcomes and, in the process, learn to communicate more effectively with one another.

Along the way, I faced both personal and professional challenges fraught with drama. Divorce. Being fired from a job I didn’t relish in the first place. Working for one of the worst bosses ever. You get the picture—the usual roller coaster of life. Of course, I have been blessed with many ups as well as downs on the journey.

Dealing with the dramas in my personal life, coupled with what I was learning in my profession, led to the writing and publication of my first book, The Power of TED* (*The Empowerment Dynamic). Largely due to the struggles I faced in these personal dramas, the book was written as a fable on “self-leadership.”

The fable format of that book struck a chord. To date, The Power of TED* has sold well over 100,000 copies in print, e-book, and audio. People continue to write me to share how the book has changed their relationships at home, at school, and at work. I have been humbled by the stories people have told in their letters and emails. Some have brought me to tears.

To my surprise and delight, many organizations started adopting The Power of TED*, its language, and its frameworks in their efforts to improve the ways employees relate to one another, as well as to customers and other stakeholders.

As an outgrowth of the reception The Power of TED* was having in organizations, I began teaching classes—along with my wife, Donna Zajonc, who is a Master Certified Coach and a great facilitator. We developed and now teach the 3 Vital Questions as a way to more clearly and directly apply the TED* (*The Empowerment Dynamic)® frameworks to organizational realities.

As Donna and I began to offer the 3 Vital Questions® material via workshops, consultations, and presentations, we found that simply asking these questions engaged people and contributed to significant positive change in their workplaces. People began asking, “When are you going to write the 3 Vital Questions book?”

Well, here it is.

If you have ever experienced infighting, such as a team or a department pitting itself against another team or department; if you have ever worked for a micromanaging and overbearing boss; if you have ever navigated the changes that come with a merger or other significant restructuring process, then you have had a front-row seat to organizational drama.

The cost of drama is tremendous, for any organization. Do a quick online search on “the cost of workplace drama” and you may be amazed at some of the hard dollars-and-cents costs associated with organizational conflict. These costs accrue due to lost productivity, turf battles, infighting, gossip, rumors, picking sides, blaming, faultfinding, absenteeism, turnover, and engaging in what Peter Block has called the politics of manipulation.

Gallup research indicates that there’s approximately $500 billion in lost productivity annually, in the United States alone, due to negative behavior in organizations. Other research has estimated that managers spend as much as 40% of their time dealing with conflict and drama. Sadly, in the case of some organizations, that estimate may be low.

At a minimum, workplace drama causes inefficiency, frustration, and waste. The personal costs to those who work in organizations is immeasurable.

At one point in my career, a new boss took over the department I worked in. This person, I soon discovered, was the most drama-producing boss I would ever work for. Every night I went home stressed and exhausted, worrying what the next day would bring. I tossed and turned at night. I wasn’t present to my family even when at home because I was always thinking about my problems at work. I engaged in “ain’t it awful” stories of my work life with anyone who would listen. This book’s fable turns that story around, eradicating the drama in much the way I wish I had been able to turn my own story around those many years ago.

Needless to say—but its very prevalence points out our need to say it—drama is one of the primary forms of resistance and reactivity that hobbles the rate of positive organizational change. Even when positive change does take place, the initial atmosphere of success and freshness can quickly turn into an atmosphere of failure and discouragement once the drama resumes. And almost any experience of drama at work can be traced back to the impact of resistance to change.

What is the answer? Transforming and reducing drama in the workplace.

Before I get into that story, however, I think it is important to reveal the deeper professional context that gave rise to this work.

This book was more than three decades in the making. Since it is entitled 3 Vital Questions, I guess you could say it represents one vital question per decade!

Over that period, I was working in leadership education and development, executive coaching, and organizational development, and in this work I found countless models, workshops, books, articles, and conversations that informed me along the way.

Life in our organizations is undergoing unprecedented and increasing change. A bold new era of volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (sometimes referred to as VUCA) presents constant challenges for leaders and organizational cultures. Ask any executive—whether in the corporate, nonprofit, or educational world—and they can readily describe the anxiety that comes with this volatile mix of conditions.

In my professional journey, there was one pivotal learning experience that sparked the inquiry—and set the stage—for what became the 3 Vital Questions.

It was the mid-1990s. I was attending a workshop on organizational culture. I was there in my capacity as program manager and internal organizational development consultant focusing on executive education for a major financial services corporation. One of the faculty (David Ulrich of the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business) presented his research findings on the success rate of change efforts in organizations. I was stunned (but not too surprised) when he reported that 80% to 85% of change efforts fail to produce their intended results!

Other studies’ results have landed in the same ballpark as Ulrich’s findings. At best, research indicates at least 60% of organizational change efforts fail to produce lasting positive change.

To be fair, the studies included a range of “failure”—from crash-and-burn utter failure to the change initiative simply taking longer than planned or not attaining the level of results (e.g., cost savings) originally projected.

My own experience had shown me that many change initiatives bring with them a certain level of resentment, resistance, and (surprise!) drama—themes that are woven throughout this book.

But first, back to the impact of that learning experience and those statistics. I started to wonder: what might be some of the underlying causes of such a poor success rate? I pondered, did a little research, had conversations with colleagues. And then …

Then, I came across an article by Peter Senge (“Building Learning Organizations,” published in the March 1992 issue of the Journal for Quality and Participation). Embedded in the article was the clue I had been searching for—one that has informed much of my work ever since.

Senge referred to an observation by Douglas Englebart (collaborative work expert and inventor of the computer mouse), that every organization has three dimensions of work. Every organization—be it a for-profit corporation, a nonprofit organization, an educational organization, or any other type of entity.

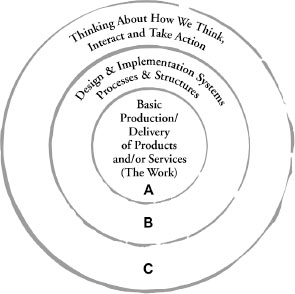

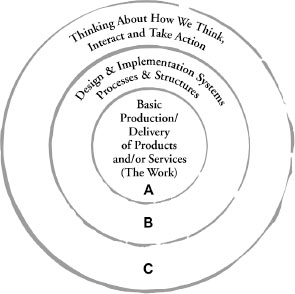

The article referred to these three dimensions simply as A, B, and C (see also Diagram 1):

The production and delivery of products and/or services. This is “the work” we engage in to serve our customers and clients.

The design and implementation of the systems, processes, and structures that enable the work to be done. The primary responsibility for this dimension is held by management.

The way we think about how we think, interact, and take action. To quote Senge’s article, “Ultimately, the quality of [this] work determines the quality of the systems and processes [that organizations] design and the products and services [they] provide” (p. 35). This is the work of leadership—which can include anyone, anywhere in the organization.

Diagram 1. The Three Dimensions of Work

Here’s an example of how dimension C affects dimension B that is critical to the epiphany that is coming:

Douglas McGregor, at MIT’s Sloan School of Management in the 1940s, developed a theory of employee motivation that addresses thinking about how we think, interact, and act. He called it, simply, Theory X and Theory Y.

Theory X sees employees (and co-workers) as problems. It assumes that people are basically lazy and will avoid work if they can, so they need to be controlled and threatened with punishment if they do not perform. This, of course, creates environments of mistrust, blame, and drama. This set of assumptions leads to systems, processes, and structures (dimension B) that are traditionally controlling, hierarchical, heavy on policies and procedures, and perpetuate an environment of “us” versus “them,” such as workers versus management, “our” department versus others, and so on.

Theory Y, on the other hand, assumes that employees and co-workers are inherently self-motivated and seek out work and responsibility that satisfies their desire to create products and services that meet the needs of others. They want to do a good job. Therefore, management seeks ways to tap into the creativity and commitment of those doing the work (dimension A) through systems, processes, and structures (dimension B) such as self-directed work teams, employee empowerment initiatives, encouragement of employee input and feedback, and so on.

I still remember reading that article and having one of those eureka moments as it suddenly hit me why so many change efforts fail.

And here it is, the fundamental reason: most change initiatives are rooted in dimension B—management’s systems, processes and structures—without any consideration for, let alone work within, dimension C, which is how we’re thinking about how we work.

Managers may restructure or implement systems for improvement, or attempt to instill what some call a “burning platform for change” in the workforce. None of these are bad things to do per se. In fact, in the right context, they can be hugely useful. But if they are initiated without stepping back into dimension C—thinking about how we think, how we interact, and how we take action—then sustainable and successful change is quite unlikely. As one former colleague quipped, “All we’re doing is pushing soap around the tub!”

The 3 Vital Questions are purely focused on dimension C—a dimension of work that has been missing in all too many change methodologies. And while this book is squarely focused on organizational life, the challenge of creating change in our personal lives (e.g., weight loss, healthy eating, smoking cessation) also can be addressed by stepping back and doing dimension C work on ourselves.

It begins with establishing and practicing the 3 Vital Questions, which set the stage for sustainable change and fulfilling work. It is this inside-out work (on the individual and personal level) that leads to outside-in work on the organization.

The following questions represent my addition to the contributions of many others. The questions focus on what I have found to be the most important frameworks and tools that inform dimension C—the essential dimension that precedes as well as enhances successful change management. I believe these three questions are what change leadership is all about.

Question 1. Where are you putting your focus?

Are you focusing on problems or on outcomes?

Question 2. How are you relating?

How are you relating to others, to your experience, and even to yourself? Are you relating in ways that produce or perpetuate drama, or in ways that empower others and yourself to be more resourceful, resilient, and innovative?

Question 3. What actions are you taking?

Are you merely reacting to the problems of the moment, or are you taking creative and generative action—including the solving of problems—in service to outcomes?

In formulating this set of 3 Vital Questions, I have benefited greatly from the influence of intimate and distant mentors, as well as a measure of creative thinking and experience. In particular, I was blessed many years ago when three powerful influences came into my life in a synchronous way over a period of several months.

First, I was exposed to the work of Robert Fritz, through his early course on the Technologies for Creating, which I experienced through a workshop facilitated by a certified instructor. The principles of what Fritz calls structural tension are captured in his books The Path of Least Resistance (1989) and Creating (1991). Fritz’s concepts were described as creative tension in Peter Senge’s classic The Fifth Discipline (1990). I choose to describe this framework—in chapters 10 and 11—as dynamic tension because my experience is that it characterizes the constant change and unfolding involved in the process of creating outcomes. This work informs the third of the 3 Vital Questions.

Shortly thereafter, I was introduced to Bob Anderson, founder of The Leadership Circle (www.theleadershipcircle.com) and now chairman and chief development officer of the Full Circle Group (www.fcg-global.com), as well as co-author with William Adams of the extraordinary book Mastering Leadership (2016). I cannot overstate Bob’s influence on me, through his genius and through our work together over the past quarter century (plus), during which Bob became a close colleague, mentor, collaborator, and ultimately a dear friend. I was fortunate to become an early facilitator of his Empowering Leadership workshop (a title later changed to Mastering Leadership and now called Authentic Leader).

Bob’s originality and creativity have led to an amazing body of work, including the most powerful 360-degree feedback tool I have ever experienced: the Leadership Circle Profile. Bob’s early work on mental models and what he calls the human operating system forms the foundation of the 3 Vital Questions. In particular, it informs the first of the 3 Vital Questions and the way I describe the two primary orientations (which I refer to as the Problem and Outcome Orientations and he refers to as the Reactive and Creative Orientations). References to the Leadership Circle Profile (LCP) come from my former work as a facilitator of certifications for the LCP and my continued services as a coach and debriefer of this most powerful feedback system.

Shortly after meeting and beginning to work with Bob, I entered a challenging personal period in which I learned about the Karpman Drama Triangle, developed by Dr. Stephen Karpman in the late 1960s. His brilliant observation of the relationship dynamics that show up whenever we experience or witness drama was, for me, a blinding flash of the obvious. After months of contemplating the insights of this model, I experienced the epiphany of a much more empowered way of being in relationship with others. This “aha” moment eventually led to the writing and publication of The Power of TED* (*The Empowerment Dynamic).

While writing this book on the 3 Vital Questions, I drew on specific concepts learned from two other particular sources: The idea of there being a “commitment behind the complaint”—discussed in chapter 8—comes from the work of Robert Kegan and Lisa Laskow Lahey, presented in their book How the Way We Talk Can Change the Way We Work: Seven Languages of Transformation (2001). The distinction between the “looking good” and “learning” intentions—mentioned in chapter 9—comes from the work of Diana Cawood (www.cleardaycoach.com) and is used with permission.

These frameworks and relational “technologies” are the heart and soul of this book. Though I have read, experienced, and experimented with countless theories, workshops, models, and tools over the years, in my teaching over the past thirty years I have returned again and again to the foundational questions that are presented here.

In keeping with The Power of TED*, this book is written as a fable in which people in different areas of an organization learn to apply the 3 Vital Questions as they navigate change in ways that empower them, transform their workplace dramas, and produce lasting positive results.

You will meet Lucas, a young professional in an informal leadership role, who is marking time in a job that no longer inspires him while dealing with a new boss who adds fuel to his struggles.

Staying late one night, Lucas meets a custodian by the name of Ted. But Ted is no ordinary custodian. These two strike up a conversation that unfolds over many months as Ted shares with Lucas the 3 Vital Questions that he learned years before from a senior executive.

Besides sharing what he is learning with his wife, Sarah, Lucas discovers that his neighbor, Kasey, is a successful middle manager in another part of the same organization and that, earlier in her career, Kasey once had much the same experience with Ted-the-custodian that Lucas is now having. Kasey becomes a mentor to Lucas, helping him to think through and, most importantly, apply the 3 Vital Questions to the challenges he faces.

Lucas discovers that in work, as well as in all areas of life, transformation begins by recognizing one’s own drama. And so his story begins.