Chapter 28. Windows Control Panel Utilities

This chapter covers the following A+ 220-1002 exam objective:

• 1.6 – Given a scenario, use Microsoft Windows Control Panel utilities.

This chapter focuses on the Control Panel. We’ll be discussing many of the utilities that are stored in the Windows CP, and we’ll be digging through a bunch of dialog boxes and other utility windows. Take some time to look at your Windows system’s Control Panel, and familiarize yourself with the various icons that are displayed—in Category mode, and in icons mode. Let us begin.

Note

Some of the items listed in this CompTIA A+ objective are covered elsewhere in the book.

As always, I highly recommend opening and working on programs and utilities within a VM, or at a system that is located on an isolated test network (or both!)

1.6 – Given a scenario, use Microsoft Windows Control Panel utilities.

ExamAlert

Objective 1.6 concentrates on: Internet Options; Display Settings; User Accounts; Folder Options; System; Windows Firewall; Power Options; Credential Manager; Programs and Features; HomeGroup; Devices and Printers; Sound; Troubleshooting; Network and Sharing Center; Device Manager; BitLocker; and Sync Center.

The Control Panel (CP) is where a user would go to make system configuration changes; for example, changing the color scheme, making connections to networks, installing or modifying new hardware, and so on. The Control Panel can be opened in a variety of ways. For example, in Windows 10 go to Start > Windows System > Control Panel. In Windows 8, you can use the Charms bar or right-click Start. In Windows 7, you can click Start > Control Panel. Or in any Windows OS, you can type control in the Search field or Run prompt. By default, the Control Panel shows up in Category view. For example, in Windows 10, 8 and 7, System and Security is a category. To see all the individual Control Panel icons, click the drop-down arrow next to View by: Category, and then select either Large icons or Small icons.

Get used to working in the Control Panel, but keep in mind that for Windows 10 some of the icons have been moved to the Settings area. Either way, be ready to operate these tools—for the exam, and for the real-world.

ExamAlert

The CompTIA A+ exams expect you to know the individual icons in the Control Panel. In Windows, this is also referred to as All Control Panel Items. Study them!

Internet Options

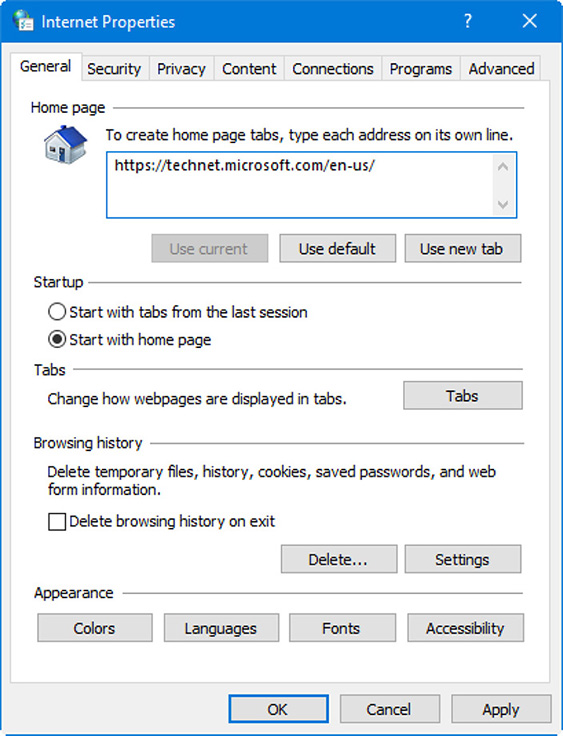

Internet Options is where you go if you want to make configuration changes for Internet Explorer (IE) or Edge. These changes can also carry over to other browsers that ride along on top of IE/Edge. If you open the Internet Options applet in the Control Panel of Windows it will bring up the Internet Properties dialog box as shown in Figure 28.1. You can also open it by going to Run, and typing inetcpl.cpl.

Figure 28.1 Internet Properties dialog box opened to the General tab

Here we have seven tabs. The names are pretty self-explanatory, but let’s discuss each one briefly. These are just the basics for now, but you should know the tabs well because we will be returning to many of them as we progress through the book.

• General: In this first tab you can set the home page (or pages) to whatever you want. You can see that we set it to the TechNet. You can also configure how pages are displayed, delete the browsing history, and change the appearance of the browser.

• Security: Here you can create and modify security zones—including the Internet—and change the security levels for each zone; this checks for ActiveX controls, unsafe content, and has other safeguards. The higher you set the slider, the more security there will be, and the less you will be able to connect to. We’ll discuss this concept more in the security section of this book.

• Privacy: In this tab you can block or allow specific websites (domains) and enable/configure the pop-up blocker.

• Content: Use this tab to find out what security certificates have been installed that IE/Edge can use, and to import new certificates. You can get more in-depth information about certificates in the Certificate Manager (certmgr.msc). In this tab you can also change the AutoComplete settings which suggest full words and phrases based on the first couple of letters that you type into the URL bar and text fields.

• Connections: Here you can set up different connections to the Internet including broadband and dial-up, and manage LAN settings, including the ability to connect to websites via a proxy server.

• Programs: Use this tab to select how links will be opened, manage add-ons, use an HTML editor, and set programs and associations with IE/Edge.

• Advanced: This tab is the catch-all for the rest of the settings that don’t fit in the other tabs, as well as advanced settings such as international settings, multimedia, and security settings.

ExamAlert

Be able to describe each of the Internet Properties tabs for the exam.

Display

Display is where we can modify how our monitor outputs the image of the OS, change the size of items, calibrate color, project to other screens, and make use of ClearType text, which is a Microsoft technology designed to automatically make displayed text appear clearer. These are pretty straightforward settings, but three concepts require a little more discussion: Resolution, refresh rate and color depth.

Note

In Windows 10, Display has moved from the Control Panel to Settings.

Resolution

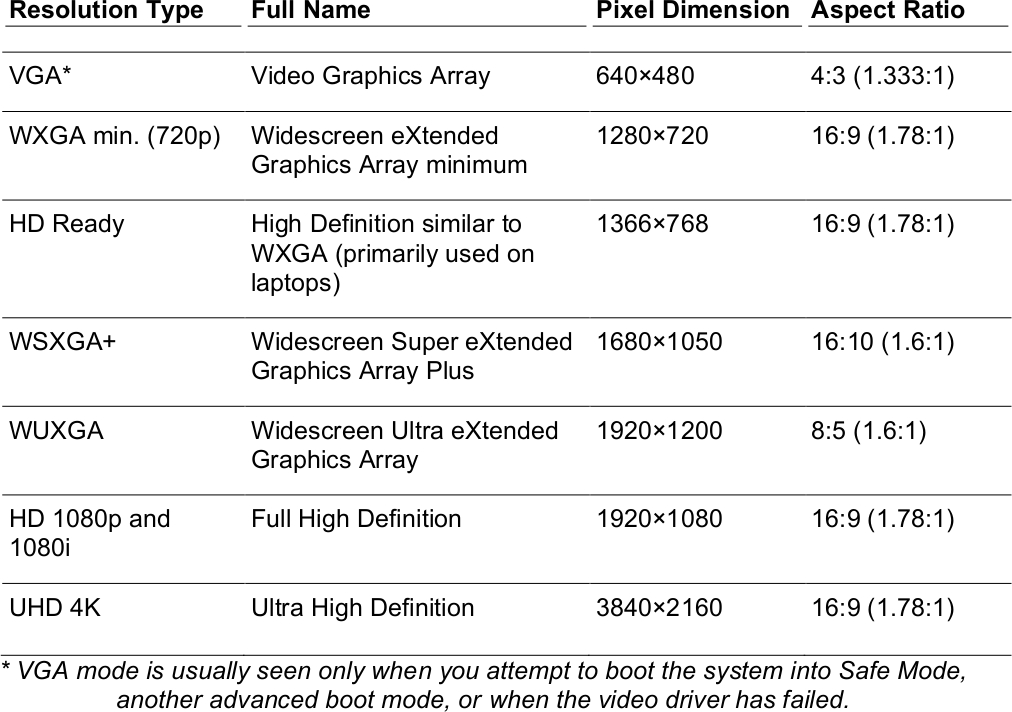

Display resolution is described as the number of pixels (picture elements) on a screen. It is measured horizontally by vertically (H×V). The more pixels that can be used on the screen, the bigger the desktop becomes and the more windows a user can fit on the display. The word resolution is somewhat of a misnomer and will also be referred to as pixel dimensions. Table 28.1 shows several typical resolutions used in Windows.

Table 28.1 List of Display Resolutions

Aspect ratio can be defined as an image’s width divided by its height (for example, VGA’s resolution is 640×480). When you divide the width (640) by the height (480), the result is 1.333. You also hear this referred to as a four-to-three ratio (4:3). This means that for every 4 pixels running horizontally, there are 3 pixels running vertically. Wider resolutions have a higher first number (for example 16:9). Most current laptops and desktop LCD screens use a widescreen format by default (16:9, 8:5, or 16:10). Take a look at your own computer’s resolution setting and figure out which aspect ratio it uses.

Display resolutions continue to get larger. Keep in mind, however, that the maximum resolution of a monitor can be achieved only if the video card—and cable—can support it.

Patch Management

Know the high-def resolution modes and understand the difference between the 16:9, 16:10, 8:5, and 4:3 aspect ratios.

To modify screen resolution in Windows 8/7, right-click the desktop and select Screen Resolution. The Resolution drop-down menu is within that window. Or go to Control Panel > All Control Panel Items > Display, and click the Adjust resolution link. In Windows 10, right-click the desktop and select Display Settings, or go to Settings > Display. Remember that there are usually several ways to navigate to the same configuration Window—use whatever works best for you!

Sometimes a user might set the resolution too high, resulting in a scrambled or distorted display. This can happen when video cards support higher resolution modes than the monitor supports. When this happens, reboot the computer into either Enable Low-Resolution Video or Safe Mode, and then adjust the resolution setting to a level that the monitor can support.

A video card’s amount of memory dictates the highest resolution and color depth settings. You can multiply the resolution by the color depth to find out how much memory will be needed. For example, if a user wants to run a 1920×1080 resolution at 32-bit color (4 bytes of color), the equation is 1920×1080×4, which would equal approximately 8 MB—easily covered by today’s video cards. But keep in mind that this is the bare minimum needed to display Windows and that more will be necessary for advanced display settings. Much more video memory is necessary to run games and graphics programs. Some desktop computers and laptops have integrated video, which uses shared video memory. This means that instead of the video device having its own memory, it shares the motherboard’s RAM. Motherboard RAM will usually be slower than a video card’s memory, and there will probably be less available. Due to this, a PCI Express video card is recommended over integrated video for computers that run resource-intensive applications such as CAD, virtualization, video editing, and games.

Note

Another related concept is video scaling. Windows allows for scaling which makes icons, text, and images appear bigger on the screen without having to adjust the resolution. For example, Windows 10 allows custom scaling between 100% and 500% of the original. This can be very helpful for educators and presenters, people with poor vision, or for technicians who remotely control systems that have very high resolutions.

Color Depth

Color depth (also known as bit depth or color quality) is a term used to describe the number of bits that represent color. For example, 1-bit color is known as monochrome—those old screens with a black background and one color for the text, like Neo’s computer in The Matrix! But what is 1-bit color? 1-bit color in the binary numbering system means a binary number with one digit. This digit can be a zero or a one, for a total of two values: usually black and white. This is defined in scientific notation as 21 (2 to the 1st power equals 2). Another example would be 4-bit color, which is used by the ancient but awesome Commodore 64 computer. In a 4-bit color system you can have 16 colors total. In this case, 24= 16. Of course, 16 colors aren’t nearly enough for today’s applications; 16-bit, 24-bit, and 32-bit are the most common color depths used by Windows. For example, 24-bit color allows for 16,777,216 different shades. 8-bit color is used in VGA mode, which is uncommon for normal use, but you might see it if you boot into Safe Mode or other advanced modes that disable the normal video driver.

Why is all this important? Two reasons:

• First, backward compatibility. A user might need to use an older program that doesn’t display well in 32-bit color. You might choose to reduce the color depth to 16-bit from within the monitor’s properties window or run the program in compatibility mode with a lesser color depth.

• Second, to reduce the amount of computer resources needed. Usually a computer has enough video resources to run 32-bit, but you never know when you will work on an older computer that has a low-end video card and limited RAM. Reducing the color depth can help the system to perform better.

To modify color depth, do the following:

• Windows 8/7: Go to All Control Panel Items > Display > Screen Resolution (or right-click the desktop and select Screen Resolution. Then click the Advanced settings link. This brings up the Display Adapter Properties dialog box. Next, go to the Monitor tab and locate the Colors menu dropdown.

• Windows 10: Go to the Display Adapter properties dialog box > Adapter tab, and click on List All Modes. Navigating to this dialog box can vary depending on third-party software. In Windows 10, one way is to go to Settings > System > Display, then click the Advanced display settings link and finally locate the Display adapter properties link.

Note

In Windows—especially Windows 10—be prepared for 32-bit color depth options only. If you can’t change color depth, consider using Program Compatibility mode instead. We’ll discuss that later in this chapter.

Refresh Rate

Refresh rate is generally known as the number of times a display is “painted” per second. It is more specifically known as vertical refresh rate. On an LCD, the liquid crystal material is illuminated at a specific frequency. This is usually set to 60 Hz and is not configurable on most LCDs. (The configuration can be found in the monitor’s properties window.) However, there are some computer monitors (and some televisions) that can go to 120 Hz and 240 Hz and beyond. If it can be configured, you would do so in the Display Adapter Properties dialog box within the Monitor tab.

Don’t confuse the refresh rate with frames per second (frames/s or fps). Although the two are directly related, they are not the same thing. For example, a digital video camera might record video at 30 fps. When played back or edited, this will run fine on a 60 Hz monitor. However, if a user is playing a video game that is set to run at 90 fps, the game attempts to send those frames of video data from the video card to the monitor. If the monitor is limited to a 60 Hz refresh rate, the video card will attempt to display the additional frames within the given refresh rate, potentially causing a blur, which might or might not be acceptable to the user. For many users in the gaming community, the higher the frames per second, the better. But to actually attain a higher frame rate (beyond 60 fps), a higher refresh rate will also be necessary.

User Accounts

There are three main types of user accounts you should know for the exam:

• The Administrator account has full (or near full) control of an operating system. It is usually the most powerful account in Windows and has access to everything.

• The Standard User account (also simply referred to as the User) is the normal account for a person on a network. The user has access to (owns) his/her data but cannot access the data of any other user and by default cannot perform administrative tasks (such as installing software).

• The Guest account has limited access to the system. A Guest cannot install software or hardware, cannot change settings or access any data, and cannot change the password.

Within Windows you can add or remove accounts, change passwords, change group associations, and so on. To make modifications to the users, do the following:

• In all versions of Windows (if the edition supports it) go to Local Users and Groups, either from within Computer Management, or directly: Run > lusrmgr.msc. Of the listed options, this is the preferred method for administrators.

• Windows 10: Go to Settings > Accounts > Family & other people (or similar name).

• Windows 8/7: Go to Control Panel > User Accounts > Manage Accounts.

We’ll be discussing user accounts more (especially user security) as we move through the book.

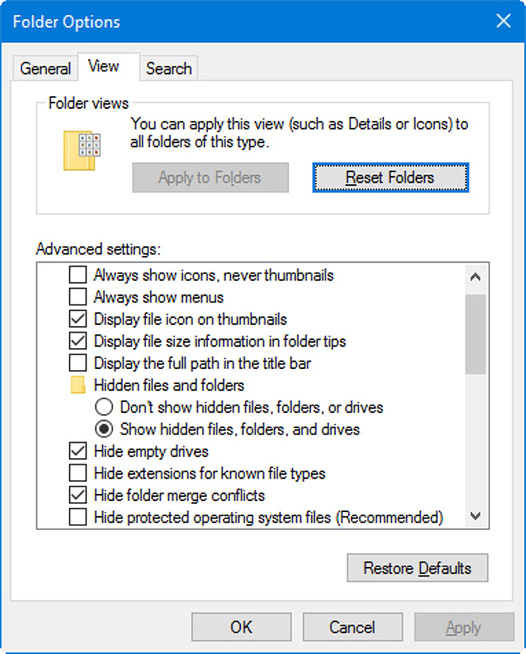

Folder Options

Folder options is where you can modify how folders display information, whether or not certain data is visible, and modify how indexes are searched. This is available as a Control Panel icon in Windows 8/7, but in Windows 10 you will have to go a different way; for example, open File Explorer—make sure you have This PC or a folder clicked—then on the menu bar click View then Options and then click Change folder and search options.

The General tab gives you the option to change how folders are browsed. By default, each folder is opened in the same window, but you could modify this so that each clicked folder opens in a separate window; just be careful, this could result in a lot of open windows and confusion. You can also choose to single-click or double click items as a preference. You can also increase privacy by deselecting the two options for showing recently used files and folders in the Quick access areas.

The View tab offers some more specific options. Take a look at Figure 28.2 for an example.

Figure 28.2 Folder Options dialog box opened to the View tab

For example, hidden files are not displayed by default. But if you select the Show hidden files, folders, and drives radio button, then hidden files will be displayed in Explorer. Another option is a couple of lines below that called: Hide protected operating system files (Recommended). This is check marked by default, but if you were to deselect that, then system files would become visible to you. If you were to do both of these things, then files such as bootmgr and pagefile.sys files would now become visible in the root of C:. You can also deselect the Hide extensions for known file types checkbox so that you can see all of the extensions associated with files. All of these are great options for the administrator, but they are not set up by default so that the typical user doesn’t get any more information than he or she needs. Spend a little time configuring the various Folder Options and imagine to yourself what would be best for the typical user and what would be best for the admin.

Performance (Virtual Memory)

Virtual memory makes a program think that it has contiguous address space, when in reality the address space can be fragmented and often spills over to a hard drive. RAM is a limited resource, whereas virtual memory is, for most practical purposes, unlimited.

There can be a large number of processes, each with its own virtual address space. When the memory in use by all the existing processes exceeds the amount of RAM available, the operating system moves pages of information to the computer’s hard drive, freeing RAM for other uses. In Windows, virtual memory is known as the paging or page file, specifically, pagefile.sys, which exists in the root of C:. To view this file, you need to unhide it. As previously mentioned, this can be done within the Folder Options dialog box in the View tab. Select the radio button called Show hidden files, folders, and drives. Then, a few lines below, deselect the check mark next to Hide protected operating system files. While you’re at it, deselect Hide extensions for known file types. This allows you to not only see the filename but the three-letter extension as well. Finally, pagefile.sys should now show up in the root of C:, where pagefile is the filename and .sys is the extension.

Take a look at the size of your page file and jot down what you find. To modify the size and location of the page file, open the System Properties dialog box and click the Advanced tab (or try using Run and typing systempropertiesadvanced.exe). Next, click the Settings button within the Performance box; this brings up the Performance Options window. Now click the Advanced tab and then click Change in the Virtual memory box. From here, you can let Windows manage the virtual memory for you or select a custom size for the page file. The paging file has the capability to increase in size as needed. If a user runs a lot of programs simultaneously, then increasing the page file size might resolve performance issues. Another option would be to move the page file to another volume on the hard drive or to another hard drive altogether. It is also possible to create multiple paging files or stripe a paging file across multiple drives to increase performance. Of course, nothing beats adding physical RAM to the computer, but when this is not an option, possibly because the motherboard has reached its capacity for RAM, optimizing the page file might be the solution. For more information about configuring virtual memory in Windows, visit https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/previous-versions/technet-magazine/ff382717(v=msdn.10).

ExamAlert

Know where to configure virtual memory, and know the location of pagefile.sys.

Note

We cover remote settings in Chapter 29, “Windows Networking and Application Installation”, and system protection and the Windows Firewall in Chapter 27, “Microsoft Operating System Features and Tools, Part 2”, as well as in the security portion of this book.

Power Management

Part of optimizing an operating system is to manage power wisely. You can manage power for hard drives, the display, and other devices; you can even manage power for the entire operating system.

To turn off devices in Windows after a specified amount of time, navigate to the Control Panel. Then select Large icons. (From now on, I will assume you know how to use the individual icons in the Control Panel.) Next, open the Power Options icon. From here, you can select a power plan such as Balanced, eco, Power Saver, or High Performance—it will vary from one computer to the next. There are a lot of settings within these power plans; here’s one example. In Balanced, click Change plan settings. The Display is set to turn off after a certain amount of time; it can be set from 1 minute to 5 hours, or it can be set to never. Going a little further, if you click the Change Advanced Power Settings link, the Power Options dialog box appears. From here, you can specify how long before the hard drive turns off and set power savings for devices such as the processor, wireless, USB, PCI Express, and so on. Take a few minutes looking through these options and the options for the other power plans.

Some users confuse the terms standby and hibernate; let’s try to eliminate that confusion now. Standby means that the computer goes into a low power mode, shutting off the display and hard drives. Information that you were working on and the state of the computer are stored in RAM. The processor still functions but has been throttled down and uses less power. Taking the computer out of standby mode is a quick process; it usually requires the user to press the power button or a key on the keyboard. It takes only a few seconds for the CPU to process the standby information in RAM and return the computer to the previous working state. Hard drives and other peripherals might take a few more seconds to get up to speed. Keep in mind that when there is a loss of power, the computer will turn off and the contents of RAM will be erased, unless it is a laptop (which has a built-in battery) or if the computer is connected to a UPS; but either way, uptime will be limited. Note that some laptops still use a fair amount of power when in standby mode. Hibernate is different than standby in that it effectively shuts down the computer. Hibernation consumes the least amount of power of any power state except for when the computer is turned off. All data that was worked on is stored to the hard drive in a file called hiberfil.sys in the root of C:. This will usually be a large file. Because RAM is volatile and the hard drive is not, hibernate is a safer option when it comes to protecting the data and the session that you were working on, especially if you plan to leave the computer on for an extended period of time. However, because the hard drive is so much slower than RAM, coming out of hibernation will take longer than coming out of standby mode. Hibernation has also been known to fail in some cases and cause various issues in Windows.

Standby is known as “Sleep” in Windows and is accessible in the same location as the shutdown options. Either use the Start button (click or right-click) or press Alt+F4 on the keyboard (after all other programs have been closed).

Hibernation, however, might need to be turned on before it can be used. To enable hibernation in Windows, open the Command Prompt as an administrator. Then type powercfg.exe/hibernate on. Next, you need to turn off Hybrid sleep in the Power Options dialog box that we accessed previously. Expand Sleep, expand Allow Hybrid Sleep, and then set it to off. Finally, set the Hibernate After option to the number of minutes you desire. Now check the Start menu again; the Hibernate option should be there just below Sleep.

ExamAlert

Know the differences between standby, sleep, and hibernate.

Credential Manager

The Windows Credential Manager is where login-based information is stored. These could be basic credentials such as usernames and passwords, or more complex credentials that use certificates. From this program you can add, remove and edit the credentials that give you access to networks and websites.

You can open this directly from Control Panel > All Control Panel Items. (You can also go to Run, and type control /name Microsoft.CredentialManager.)

By default, when you first open the program you will see Web Credentials and Windows Credentials. A web credential could be a login to a social media site that you allowed Windows to save for you. An example of a Windows credential could be a login to a Microsoft domain or to a local system.

Open a credential by clicking the arrow; from here you can remove the credential or edit it (for example, editing the password). You can also add new credentials, back them up and restore them.

Another window with the same content (called Stored User Names and Passwords), can be access from the command line by typing the following:

rundll32.exe keymgr.dll, KRShowKeyMgr

Once again, here you can add or remove—and backup and restore—credentials for programs, websites, and networks; but the data is organized differently.

Take a look at both programs, and analyze the stored passwords. You might be surprised by some of the credentials that are stored there—especially Web Credentials. Be ready to remove these if they are unwanted, or pose a security risk.

Programs and Features

Programs and Features is used to modify Windows applications and features, as well as third-part applications and features, and to repair them or uninstall them.

You can get to the list of options under Programs and Features by accessing the Control Panel (in Category mode) and by selecting Programs. From there you will see options to uninstall programs, turn Windows features on or off, view the installed updates for Windows and other programs, and Run programs made for previous versions of Windows. Except for that last one, these options are also available if you go to Control Panel > All Control Panel Items > Programs and Features. (Go directly there by accessing Run and typing appwiz.cpl.)

So, if you need to uninstall or repair a program, or if you need to add features (such as Hyper-V or the .NET Framework), then use Programs and Features.

ExamAlert

Know how to access Programs and Features to uninstall programs or turn Windows features on or off.

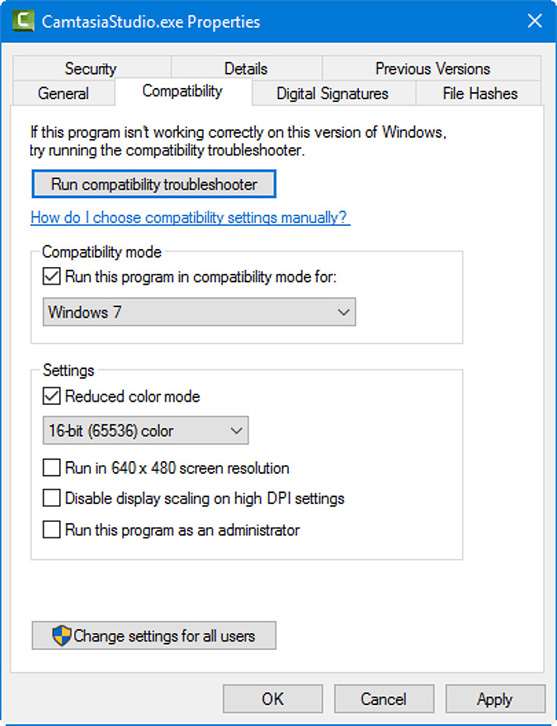

Program Compatibility

Most applications run properly on Windows. However, some applications that were designed for older versions of Windows might not run properly on your version of Windows. To make applications written for older versions of Windows compatible with Windows 10/8/7, use the Program Compatibility utility or the Compatibility tab of a program file’s Properties window.

To start the wizard in Windows, open the Control Panel and then click the Programs icon (in Category mode). Then, under Programs and Features, click the link called Run Programs Made for Previous Versions of Windows. That brings up the Program Compatibility Troubleshooter. This program asks you which programs you want to make compatible, which OS it should be compatible with, and (depending on the version) inquires as to the resolution and colors that the program should run in. Windows will attempt to “fix” programs automatically if possible. The Program Compatibility Troubleshooter can also be run from the Compatibility tab of an individual program’s properties.

To use the Compatibility tab, right-click the program you want to make compatible from within Explorer and then click Properties. From there, click the Compatibility tab. You can select which OS compatibility mode you want to run the program in and define settings such as resolution, colors, and so on. An example of this is displayed in Figure 28.3 which was taken from a Windows 10 Pro computer. It shows an older version of an application that I have set to run in compatibility mode for Windows 7 and at reduced color (16-bit).

Figure 28.3 Compatibility tab of a program’s Properties window.

Windows incorporates the Program Compatibility Assistant (PCA), which automatically attempts to help end users run applications that were designed for earlier versions of Windows. If for some reason, this assistant were to cause a program to fail, then its service can be disabled in services.msc or in the Group Policy Editor. For more information on some common PCA scenarios visit: https://docs.microsoft.com/enus/windows/desktop/w8cookbook/pca-scenarios-for-windows-8

ExamAlert

Know how to use the Program Compatibility utility and the Compatibility tab in a program’s Properties window.

Devices and Printers

This is where you can add, configure, troubleshoot, and remove your printers and other devices such as monitors, UPS, wireless devices, mice, and audio/multimedia devices. Most technicians use it for printers, and if you do, you’ll find that it can be a good launching point for the configuration of other devices on the system. We discuss this part of Windows more in the printers section and elsewhere in the book.

Note

Although HomeGroup has been removed as of Windows 10, we discuss it in Chapter 29 as well as the Network and Sharing Center.

Sound

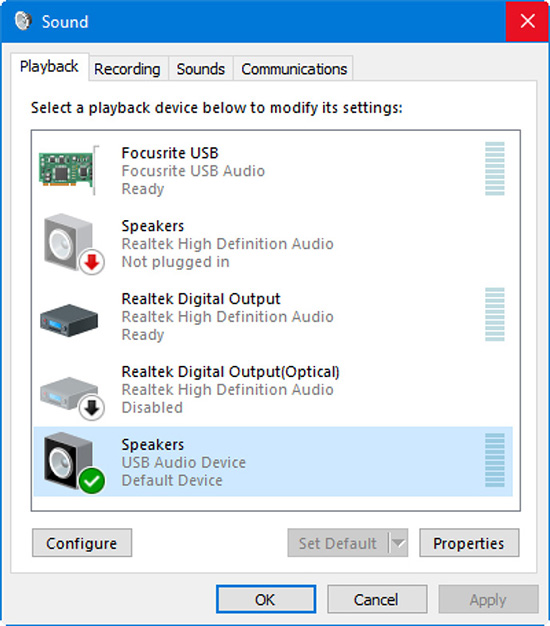

Audio takes a back seat in the A+ certification somewhat, but in some environments—for example in my line of work—it is crucial. To troubleshoot audio problems, the best place to go is: Control Panel > All Control Panel Items > Sound, which displays a dialog box similar to Figure 28.4. You can also get to this by right-clicking the sound icon in the notification area and selecting Sounds, or going to Run, and typing mmsys.cpl.

Figure 28.4 Sound dialog box in Windows

Here you can modify which audio devices are used for playback and recording, as well as select specific sound themes for Windows. You can also modify what happens with the volume of Windows and programs when communications are detected, for example video chatting, or webinars.

In Figure 28.4, you’ll note that the device simply called “Speakers” is check marked; that means it is the default device that will be used for the playback of audio. On my system, that happens to be a USB headset. In addition to that, there is a Focusrite USB device that is “Ready”. If we needed to output audio from that device, we would have to right-click it and select Set as default device. The same process is necessary in the Recording tab if you are using multiple microphones and recording devices. As people such as technicians, educators, presenters, and video bloggers want to incorporate better microphones than the ones that are included with a system, this recording tab of the Sound dialog box becomes critical. However, if you have a custom audio processor with its own software, you might have to access that instead of the Sound dialog box to get full functionality, or possibly to have any functionality at all.

ExamAlert

Know how to enable and disable audio devices in the Playback and Recording tabs of the Sound dialog box.

Troubleshooting

Windows comes with a built-in troubleshooting system that can automatically attempt to fix problems with the system related to programs, hardware, Internet connections, network connectivity, system settings, security, and more. If a program, device, or setting fails, the troubleshooter (by default) will try to help with the problem. Or you can go to the Troubleshooting icon in the Control Panel, and look for help for your specific problem; be it hardware or software related. You can also disable the automatic troubleshooter here (if it interferes with your software), and perform a remote assistance request (shown as a link called Get help from a friend) to have others aid with the problem.

You can also initiate specific troubleshooters from the command line (or Run). For example, let’s say that you were having issues with a UPS that is connected to your computer via USB. If you wanted to have Windows troubleshoot your power system, then you could type msdt.exe /id PowerDiagnostic. That will bring up the Power troubleshooter window. The msdt.exe (Microsoft Support Diagnostic Tool) is pretty powerful. There are a lot of IDs that you can use to troubleshoot different parts of the system. See the following link for a list of those Troubleshooting Pack IDs.

In addition, if you have engaged in a tech support communication of some sort with Microsoft, they might give you a passkey to be used with msdt so that they can further analyze your system. Simply type msdt in the Run prompt, and type in the passkey to get additional support for the computer.

Sync Center

The Sync Center is valuable when you are dealing with files that you work on that are stored locally as well as on file servers. This tool keeps the data between the two files synchronized as you update on one location or another. If you work on data that is stored on the cloud, a tool such as this becomes less commonly used. But if you need to work on files locally and from other locations or from a network drive and the file has to exist in multiple locations, then the Sync Center might be necessary. The Sync Center utility allows you to view any partnerships that you currently have, and any conflicts that might occur. If you want to keep copies of your work stored on a file server, you might need to enable offline files, which you can do from here. If the file server goes down, then files that have been configured as offline files can still be worked on, and when the server comes back up, they will be synchronized (if synchronization has been configured properly). Offline files can be viewed once they are enabled in the Offline Files Folder and are stored in C:\Windows\CSC (permissions are required to view this folder).

Note

We discuss the Device Manager in Chapter 26, Microsoft Operating System Features and Tools, Part 1,” and BitLocker in Chapter 33, “Windows Security Settings and Best Practices.”

Cram Quiz

Answer these questions. The answers follow the last question. If you cannot answer these questions correctly, consider reading this section again until you can.

1. You have been tasked with verifying the certificates that are in use on a computer that is configured to use Microsoft Edge. Which tab of the Internet Properties dialog box should you access?

![]() A. General

A. General

![]() B. Security

B. Security

![]() C. Privacy

C. Privacy

![]() D. Content

D. Content

![]() E. Connections

E. Connections

![]() F. Programs

F. Programs

![]() G. Advanced

G. Advanced

2. Which window would you navigate to in order to modify the virtual memory settings in Windows? (Select the best answer.)

![]() A. Device Manager

A. Device Manager

![]() B. Performance Options

B. Performance Options

![]() C. System

C. System

![]() D. Folder Options

D. Folder Options

![]() E. System Properties

E. System Properties

3. Which power management mode stores data on the hard drive?

![]() A. Sleep

A. Sleep

![]() B. Hibernate

B. Hibernate

![]() C. Standby

C. Standby

![]() D. Pillow.exe

D. Pillow.exe

4. What should you modify if you needed to change the number of pixels that are displayed horizontally and vertically on the screen?

![]() A. Color depth

A. Color depth

![]() B. Refresh rate

B. Refresh rate

![]() C. Resolution

C. Resolution

![]() D. Scaling

D. Scaling

5. You are about to start troubleshooting a Windows system. You need to be able to view the bootmgr file in the C: root of the hard drive. Which of the following should you configure to make this file visible? (Select the two best answers.)

![]() A. Hidden files and folders

A. Hidden files and folders

![]() B. Extensions for known file types

B. Extensions for known file types

![]() C. Encrypted or compressed NTFS files in color

C. Encrypted or compressed NTFS files in color

![]() D. Protected operating system files

D. Protected operating system files

6. A customer’s computer has many logins to websites saved within Windows. Some of these are security risks. Where can you go to remove those login usernames and passwords? (Select the two best answers.)

![]() A. Programs and Features

A. Programs and Features

![]() B. Credential Manager

B. Credential Manager

![]() C. Devices and Printers

C. Devices and Printers

![]() D. MSDT

D. MSDT

![]() E. Store User Names and Passwords

E. Store User Names and Passwords

![]() F. Sync Center

F. Sync Center

Cram Quiz Answers

1. D. Go to the Content tab of the Internet Properties dialog box (also known as Internet Options) to find out about the certificates that are in use within Microsoft Edge or Internet Explorer—and any other browsers that piggyback the Internet Properties settings.

2. B. Navigate to the Performance Options dialog box and then click the Advanced tab to modify virtual memory in Windows. You access that window from the System Properties window, clicking the Advanced tab, selecting the Performance section, and then clicking the Settings button. Although System Properties is essentially correct, it is not the best, or most accurate, answer.

3. B. When a computer hibernates, all the information in RAM is written to a file called hiberfil.sys in the root of C: within the hard drive.

4. C. Modify the screen resolution to change how many pixels are displayed on the screen (H x V). For example, change from 1280 x 720 to 1920 x 1200, or vice-versa. Scaling is similar in that it will make text and images appear larger or smaller depending on how you set it, but it doesn’t actually change the amount of pixels that are displayed on the screen.

5. A and D. Configure Hidden files and folders and set it to “Show hidden files, folders, and drives”, and configure protected operating system files by deselecting the check mark for the setting “Hide protected operating system files”. Files such as bootmgr are hidden and protected by default; you need to unhide them in both ways in order to see them.

6. B and E. Use the Credential Manager or the similar Store User Names and Passwords utilities to remove login credentials to websites and networks that are considered to be security risks. The less passwords that are “lying” around, the better!