CHAPTER 9

FRUITS

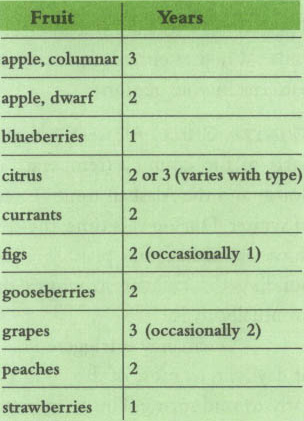

The first thing to understand about growing fruits is that it’s something of a commitment. With the possible exception of strawberries, which some people treat as annuals, plants that produce fruit need several years to become mature enough to bear their crop. Some may yield a few fruits in the second year, or even the first (see table below), but by and large it takes three years to really get the good stuff.

What you have in the meantime are some very handsome plants (some trees, some shrubs) with other virtues: lovely, fragrant flowers, striking fall color, pretty foliage, or all three. And you have a serious plant, something large enough to become the focal point around which you organize other, smaller containers into a coordinated garden design, or to stand regally on its own.

The greatest joy, though, comes with the fruit itself. Ripened to its fullest glory, it is unbelievably superior to anything store-bought. When you and your guests first experience the unique texture of a fresh fig, smooth and slightly crunchy in the same bite, or feel the sweet-tart burst of a fresh gooseberry on your tongue, or melt down to your socks at the honey-sweetness of a tree-ripened peach, you deserve to feel very, very proud of yourself.

It’s important to remember, though, that these plants will be around for years. The implications are worth reviewing.

First, we’re not talking about a petite little pansy here. Many mature fruit trees are large plants, in both height and spread. You need to plan for the future as you’re making your original selections, making sure that your space is large enough to do justice to the plant.

Also, the container itself needs to be large enough to hold a plant that will grow in it for years. (Size considerations are discussed in the individual plant sections.) The container should be made of a material that survives freezing weather: wood, plastic, or the new fiberglass material. And because you may need to relocate the container into a more sheltered spot for the winter, you should plan a way to make it easily movable: either add a set of casters, or invest in a heavy-duty plant dolly with wheels.

The second important point to keep in mind: because fruit trees and shrubs live for many years, they have to survive your winters. You need to learn about the climate patterns in your area and match them against the particular needs of the fruits you’re interested in growing.

The Crucial Questions About Climate

Two aspects of winter weather are crucial to fruit plants:

1. Exposure to the correct temperature range (32° to 45°F) for the right amount of time to send the plant into dormancy; this is known as winter chill.

2. Protection from prolonged, severe cold that could kill the plant.

These two factors are not interrelated except that they collide on the calendar. Whether either presents a problem for you is a matter of the weather patterns in your region.

WINTER CHILL. All trees and shrubs that produce fruit in the temperate parts of the country (temperate meaning everyplace between the Deep South and the Alaskan tundra) need to go through a period of dormancy in winter. During this time, the tree loses its leaves and its internal systems slow way down; the plant is alive, but resting. In this state, the plant is building the cellular structures that will in spring become flowers, and eventually fruits.

Dormancy is triggered by changes in temperature and in the hours of daylight. In most of the country, it begins in mid autumn and lasts until early to mid spring. This is an important phase in the plant’s natural annual cycle, and cannot successfully be either forced or curtailed.

Winter chill is the term used to describe a certain temperature range—between 32° and 45°F—that is necessary for the plant to set next year’s blossoms. This period of cold but not freezing weather is usually expressed in hours; and different types of fruits, even different varieties of the same fruit, need a different number of hours. For instance, apples (generally speaking) need around 600 hours of winter chill. That sounds like a lot until you realize that 600 hours translates to just 25 days, assuming that each 24-hour period remains within that 32° to 45°F range. Winter chill requirements are cumulative: sometime between when the leaves start to fall in autumn and when the new buds begin to open up in spring, the plant must be exposed to that many hours in total. Temperatures below freezing do not count.

In almost all parts of the country, except the Deep South and southern California, winter chill is not something you even need to think about. As long as you have mild to moderate winters, you will have enough winter chill hours for all the fruits in this section.

The difficulty comes in colder climates, where the dormant period includes bitterly cold months when the plant is in danger of freezing. That takes us to our second concern.

WINTER PROTECTION. Once the thermometer drops below 32°F for any prolonged period, your fruit trees and shrubs move beyond the “good” range that allows for winter chill; now they are in the danger zone where they could be killed.

This is far more of a problem for container gardeners because it is the roots that are at risk. Plants in traditional gardens are surrounded by a large mass of earth that serves to insulate the roots. In containers, the plant’s roots have just a few inches of soil, if that, between them and the surrounding air. When the air temperature is, say, 25°F, the soil in the container and the plant roots will freeze, and the plant may die—unless you take action.

We give cold protection special focus here because it’s something you have to be aware of for almost all fruits. But keep in mind that the ideas described here apply for any plants that you hope to carry through the winter. What you have to be concerned about is severe, unrelenting cold, the kind of weather where it’s 15° or 20°F or even colder at night and never gets above 32°F during the day. An occasional night at 25°F will not be fatal to the plant, as long as the temperature warms up to 32°F or above during the day.

If you live in an area that gets that kind of very cold weather in the winter, you surely know it. If your weather patterns are usually warmer than this, but occasional hard freezes are not unknown, then you need to discipline yourself to pay careful attention to the forecast and be ready to take action when needed. In both cases, you have two, maybe three, courses of action:

1. Move the entire container into a location where it will be protected from the worst weather. This may be a garage, an unheated room in your home, an outdoor shed, or something similar. It doesn’t matter if the area is dark, as long as the temperature is above freezing. Just be sure not to bring the plant indoors into a room that is heated for human comfort, or it will be too warm. During this time the tree, which is dormant, does not actively take up water, so you do not need to water it as you would outdoors; just check from time to time to be sure the soil has not completely dried out. In spring, when temperatures climb back above freezing, bring the container back outside.

2. If you don’t have such a protected space, the tree will have to stay outside, and you’ll have to wrap it and the entire container in some kind of insulating material. What you use, and how much of it, will be a function of how low you expect the thermometer to drop. See box for several ideas.

3. For double protection, set the wrapped container down onto the ground, if possible. The surrounding soil mass will keep it about 5° warmer.

As we said previously, things will be much easier if you start your fruit trees in containers that are easily moved, either by attaching casters or by setting the containers on plant dollies with wheels. Do this from the get-go, and you’ll have no trouble moving your fruit trees during their first winter. You will also find that the gap created by the wheels gives welcome room to maneuver a blanket wrap, if that’s the route you take. So in either case—for moving or for easily getting underneath the bottom of the container—a wheeled base makes life much simpler. It all boils down to this:

• Unless you live in a subtropical climate, winter chill happens naturally; you don’t have to do anything to provide for it. If you do live in a subtropical climate, accept that there are some fruits you simply won’t be able to grow. If your climate is marginal in regard to winter chill, look for varieties with significantly lower winter-chill requirements.

• In extremely cold climates you won’t have to worry about winter chill, but you will have to worry about freezing. If you’re not able to provide protection, you’re better off not trying to keep any plant alive through the winter.

Planting Techniques

Another important consideration when growing fruit trees is how to plant them. Most fruit-bearing plants come into a gardener’s life in a condition known as bare-root. (Roses are also sold this way, and many landscape plants.) The term means just what you would think: the roots are bare—that is, not planted in soil. They are encased in some material that holds moisture around the roots, and then wrapped with plastic to hold that moisture-retaining material in place.

The first time you buy a bare-root plant and open the package, you may feel your heart sink. The poor thing looks completely dead, especially if there are no leaves or buds showing. But the plant isn’t dead, it’s merely dormant; it was intentionally harvested by the grower in its dormant state because it can be shipped more safely that way. Planted in soil, watered, and set in the sun, it will soon burst into life.

Most mail-order nurseries time their shipping so that the plant arrives at your door at the correct planting time for your climate. When you receive the plant, whether through the mail or purchased at the garden center, here’s what to do:

1. Open the package, pull away the packing material, and inspect the roots. They should look strong and healthy. If they are withered, rotten, or obviously dead, return the plant and ask for a replacement. Experience, however, tells us that most nurseries are extraordinarily careful, and in all probability your new plant will be healthy. Just be sure you proceed to the next step immediately,

2. Either plant the young tree (skip to Step 3) or, if you can’t get to it right away, use one of these temporary measures:

a. Soak the plant in a bucket of water to rehydrate the roots. This will hold it for a day or two.

b. Resoak the packing material and wrap it loosely around the roots, allowing for some air circulation. This will hold it for three to four days.

c. Put the plant in a temporary pot and cover the roots with damp potting soil. This will hold it for several weeks.

3. Unless its already soaking, set the plant in a bucket of water so the roots are submerged while you get your container and all your supplies ready.

4. Prepare your soil mixture: potting mix, hydrogel crystals, slow-release fertilizer, and any extra soil amendments you might need (review Chapter 5 for details). Fill the container about one-quarter to one-third full. Add more potting mix and shape it into a mound like a volcano, with its top an inch or so below the rim of the pot.

5. Look closely at the roots of your plant, and cut away any that seem dead or mushy. If the roots are a tangled mess, use your fingers to pull them into separate strands. Trim any that are noticeably longer than the others. Your goal is to create a conical shape that will fit down over the “volcano” of soil.

6. Loosely place the roots over the “volcano” and check for fit. The crown of the plant (the spot just above the highest roots where the stem becomes somewhat smaller and darker in color) should be at the ultimate soil line, just below the rim; make the mound larger or smaller if need be.

7. Add more soil over the roots and around the edges, tamping lightly as you go. Water thoroughly and let things settle; add more soil as needed.

If it is not bare-root, a young fruit tree or shrub will be planted in a temporary nursery pot filled with soil. Growers refer to these as “container plants,” but don’t expect a handsome container that you’d want to use as the plant’s permanent home—it will be an ordinary, utilitarian black plastic. Whereas bare-root plants are available for purchase only in the dormant season, from winter to early spring, container plants have no such limitations. Theoretically, they can be sold anytime, and you can plant them whenever you find them at the garden center.

Water the nursery pot thoroughly to loosen the soil and then gently slide out the entire contents of the pot—plant and soil. Try to keep the soil ball intact as much as possible. Fill your permanent container about one-third to one-half full with new potting soil, and set the plant-plus-soil in the center. Fill in around the edges with more potting soil, water thoroughly, and you’re set.

As you ponder your wish list for your new container garden, you might think you could never include something like apples. It’s hard to imagine that the substantial specimens you may have seen in old orchards could grow on a deck or balcony. And in reality, you could never handle those huge trees in a container. Fortunately, apple specialists have developed trees that never get higher than 8 feet, sometimes less. There’s also a new form of apple tree, called columnar, that slowly grows to about 8 feet high with little or no branching; this tall, ultraslender shape is very appropriate for small spaces that would not be able to accommodate a wide-spreading tree. With these new types of trees, container growing of apples has become not only possible, but easy. And the fruits you harvest will be fully ripe, rich in flavor, and without the chemical residues found on most commercially grown fruit.

Apple Basics. Most modern fruit trees are a combination of parts of two trees, physically fused together in a process called grafting. The upper portion of one tree, the scion, which produces the fruit, is grafted onto the lower stem of another tree, called the rootstock. This is how the qualities of a particular variety are preserved.

Take the Red Delicious apple, for example. A piece of a branch from an established Red Delicious tree (the scion) is tied to a cut surface on the stem of the rootstock, where they grow together. The resulting tree will produce exactly the same fruit as the original tree from which the scion branch was cut. But if you plant seeds from a Red Delicious apple and they eventually grow into trees, those trees may bear fruit, but they won’t look or taste like the apple you started with.

The scion, in other words, determines what type of apples the tree will bear. The rootstock, in contrast, determines important growing characteristics; fruit tree growers choose a particular rootstock for the qualities it gives the tree. Some rootstocks are better adapted to wet soils, some are more resistant to certain diseases, some cause a tree to bloom and bear fruit earlier, and so on. Also, most important for our purposes here, it is the rootstock that determines the ultimate size of the tree.

For container growing, then, it is very important to learn what root-stock has been used. Rather than being given colorful names, rootstocks are identified by a code made up of a letter and a number. The letter indicates where the particular stock originated (for example, an M indicates the breeding program at the Mailing Research Station in England), and the numbers are assigned in sequence (so M-27 is the one that was developed just after M-26).

Rootstocks that will keep an apple tree to 8 feet, small enough for container growing, are P-22, M-27, M-9, and possibly M-26. Don’t bother with anything else. Mail-order catalogs that specialize in fruit trees are usually careful to identify root-stock, but at a retail garden center you may have to do some double-checking. Some garden centers sell trees that have been labeled dwarf or semi-dwarf, terms that are so imprecise they have become meaningless. Before buying a tree labeled in this way, check with staff to verify the root-stock; if necessary, ask them to contact the grower and find out what root-stock the tree is on. This will save you many headaches in the future.

Columnar trees will surprise you the first time you see them. They do not have branches in the usual sense, but merely very short stems (called spurs) attached to the main trunk, on which the apples develop, so that in late summer the full-size apples seem to be growing directly from the tree’s trunk. Any branches that do form also tend to grow straight up. The trees grow slowly but bear fruit earlier: at two years, compared to three for most others. Because columnar varieties are naturally slow growing, rootstock is not really an issue.

Pollination. Some fruit trees can bear fruit by themselves; these are described as self-fertile. Others need a different variety nearby for cross-pollination, without which they will not bear fruit. Apples are in the second group: they need another variety of apple for pollination. With a few exceptions, any two apple trees that bloom at the same time are pollinators for each other. Ideally, the two varieties should be located within 20 feet of each other. The perfect solution, if you have the room, is to grow two varieties. If that is not possible, you will have to rely on cross-pollination from an apple tree nearby.

You may also find that your tree bears fruit without any obvious pollinator. Jim Gilbert of Northwoods Nursery in Oregon, an extremely knowledgeable grower who has seen just about every possible problem, loves to tell about an old Gravenstein apple tree he once had high in the Cascade Mountains. Growing all alone, without, as far as he could tell, another apple tree for miles around, the tree produced abundant crops of fruit for years.

Hardiness. Most apple varieties are technically hardy to –25°F, which means that almost anywhere in the United States you can have a nice apple tree in your backyard, providing you have a backyard. If you’re growing your fruit trees in containers, severe cold weather can be more of a challenge.

Bear in mind that the root system of an apple tree is hardy to only about 15°F. In the ground, the earth mass keeps the root temperature from falling to dangerous levels. But in a container outdoors, without protection, your apple tree will be killed if the soil temperature drops too low. You have two ways to protect against this: (1) insulate the container and, if possible, set it on the ground, or (2) bring it into a warmer environment. See page 289 for more on both techniques.

The bottom line is this: if your winter temperatures are consistently below 15°F, and you have no way to provide some sort of protection, you will in all likelihood lose your apple tree. Unless you believe this kind of challenge builds character, you’re better off not taking the gamble.

Chilling requirements. Like most other fruit trees, apples need to go through a period of winter chill: a certain number of hours between the temperatures of 32° and 45°F. During this dormant period the trees rest, getting ready to bloom and set fruit the following season. (See page 286 for a more detailed explanation of winter chill, and see specific requirements in the Varieties section below.)

This means that you cannot keep your apple tree at room temperature all winter and expect fruit the following year. It also means that if you live in the Deep South, where temperatures rarely go below 50°F, you should plan on getting your apples at the supermarket. Southerners in marginal climate zones may have success with low-chill varieties (see the special note in the Varieties section).

In more northerly areas, where there is a distinct winter but not horrific cold, just let the tree go dormant naturally (which you will recognize when it begins to lose its leaves). Between November and February, you will undoubtedly accumulate the number of winter-chill hours you need. Remember, though, that if there is a prolonged period of bitter cold in the winter months, the container must be moved into some protected area until the weather is not so severe.

Planting. You can plant your apple tree at almost any time of year, whenever you find a healthy specimen at the garden center. You’ll probably find the greatest selection in the spring, and most will be bare-root plants (see page 290). In summer and fall, you’re more likely to find small trees in nursery containers. In warmer climates, trees are often available in the winter as well, either bare-root or containerized. If you order from a mail-order nursery specializing in fruit trees, you will in all likelihood receive a bare-root plant.

Choose a large container for your apple tree; a 10- or 15-gallon pot is the minimum for long-term growth. A coarse planting mix that drains well is best.

With a bare-root tree, first trim the roots back to fit the pot without circling, then begin filling the pot with potting mix. As you fill, hold the tree in the pot so that the graft union (the swollen area near the base) is level with the rim of the pot. Fill the pot to within about 2 inches of the top, being careful that the graft union is well above the soil line.

If you are transplanting a containerized plant, remove it from its pot and inspect the root system. If it is quite dense and has circled around the pot, you’ll need to break up the root mass somewhat. Pull at larger exposed roots and try to separate them from the main body of roots. Sometimes you may have to beat on the roots with a stick to loosen the snarl. Once you have separated some of the main roots, prune them to fit the pot, and plant as you would for a bare-root tree.

After planting, prune back the branches and the top of the tree to about one-third their length (see details in the Pruning section, below), and water the container very thoroughly, until water runs out the bottom. Now you have one more task: staking.

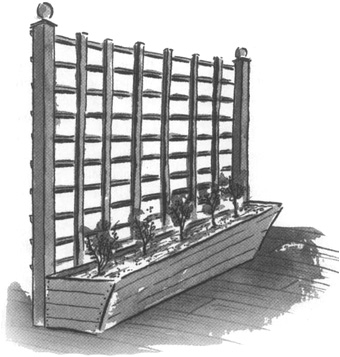

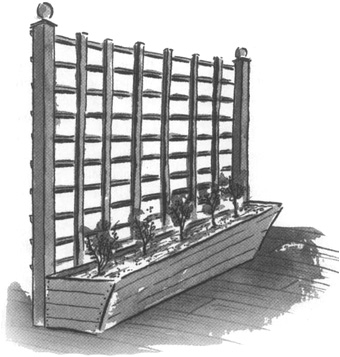

The dwarfing rootstock that keeps your tree at a small size is, unfortunately, not strong enough to hold up the tree on its own. You need to add some extra support, in the form of a stout stake or trellis. Loosely tie the main stem of the tree to the stake or trellis with thick string or a similar material. Be sure to keep it loose during the life of your tree; tightly tying a tree can disfigure or even kill it.

Columnar apple varieties usually do not need staking.

Success with Apples. Apples are easy trees to grow if you follow a few basic guidelines about watering, fertilizing, pruning, and pest and disease control.

Watering. Proper watering is critical. Your apple tree will not live without water, yet can be damaged or even killed by too much.

When you first plant a bare-root tree in the spring, water it thoroughly as described above. After that it will probably not need water again for several weeks; the root system of a dormant tree is not active, and it cannot use any excess water. Check the potting soil every few days to be sure it is not drying out. Keeping the soil lightly moist is all you need to do until your tree is actively growing.

After your tree begins growing, it will start to use the water in the pot. Check the soil more frequently, and water whenever it shows signs of drying. If your tree is in a large pot, a deep watering every five to seven days should be enough, but be especially vigilant during extremely hot, dry summer days.

Starting in late August or early September, begin holding back on the water, providing just enough to keep the soil very lightly moist. This will slow down the growth rate and allow the tree to prepare for the colder temperatures of winter.

Fertilizing. When you plant a tree in the ground, nature does a pretty good job of providing all the nutrients and minerals necessary for the tree to survive. In a container, however, those essential nutrients must come from you in the form of added fertilizer. This is not an exact science.

Take a moment to review the basics of fertilizer formulas in Chapter 6. Remember, too, that container gardens require more frequent fertilizing than traditional gardens, because the requisite frequent waterings wash away the nutrients that were in the potting mix you started with.

What type of fertilizer you use is a matter of personal choice. Just remember that your goal is the production of flowers and fruit, so select a formulation high in phosphorus (see Chapter 6 for details). Many people report good results from the following program: once a week while the tree is actively growing, give it a drink of soluble synthetic fertilizer such as Miracle-Gro, but dilute it to half strength. Others like the simplicity of a slow-release fertilizer such as Osmocote, described in Chapter 6.

Organic gardeners can choose from a variety of commercial organic fertilizers. You can also apply blood meal and bone meal to the surface of the pot in late spring, for slow-release organic fertilizing. Use one handful of each per foot of height of the tree.

Your apple tree should grow 8 to 12 inches a year, and its leaves should be dark green in color. If this happens, your fertilizer program is working. If you are using homemade organic fertilizers such as manure or compost tea and the leaves turn a pale green or yellowish green, especially the older leaves, you may want to increase the frequency of fertilizing or make a more concentrated solution.

Late in the summer, as you are beginning to cut down on water, you should also gradually stop fertilizing. This allows the tree to harden off and get ready for winter.

Pruning. Let’s return to the day you first acquired your tree. After planting, staking, and watering, it is time to think about its form. If you are growing a columnar variety, the tree should be a straight spire with few or no branches. Any branches that do appear should be very short spurs from the main trunk. Basically, columnar varieties do not need pruning. If a columnar tree gets too tall for your space, you can cut it back to about half its height; it will grow back with one or more upright branches that will soon bear fruit.

Apple varieties other than columnar will usually come as a whip (that is, a single slender trunk without branches) or as a young tree with a clearly defined main trunk and a few branches. After planting, check all the branches. First, look for any that are broken and make a cut below the break, discarding the part you cut off. Next, wherever two branches cross and rub together, prune away the weaker one, cutting back to the trunk. It is also a good idea to balance the tree by pruning back any branches that are significantly longer than others.

There is some debate about whether it is useful to do any further pruning. Some growers think it’s best to leave the tree alone at this point, while others recommend pruning branches back to about half their length to compensate for the disturbance and shock of transplanting. We advocate the latter approach.

The next thing to think about is how you want to form your tree. Keep this general concept in mind: when you remove the growing tip of a branch, it sends out side branches. If you cut back the central leader of your new tree by about half (the central leader is the shoot growing straight up at the center of the tree, what will eventually become the trunk), you accomplish two things: you control its height, and you also encourage the tree to form side branches, which are generally stronger. Take note, however, that some trees have such a strong urge for a central leader that in a few years another branch will try to grow in that position.

Assuming you started with a dwarf rootstock, cutting back the central leader simply to keep the tree short will not be needed unless you miscalculated your space. You will find, however, that by regularly pruning the leader and the strong branches, you will encourage the tree to grow the short spurs on which fruit is produced. The best time to do this is in the spring; cut away one-third to one-half of the portion of the branches that grew last year.

It is also a good idea to keep branches as horizontal as possible, as this stimulates the formation of flower buds and fruit instead of vegetative buds that simply make longer branches. To accomplish this, you can insert a short piece of wood (a wooden clothespin works well) between the trunk and branch to gently force the branch downward, or you can tie the branch down toward the floor or ground to keep it in a more horizontal position.

As the tree gets older, most of your pruning will entail removing branches that are crossing, or controlling branches or central leaden that are growing too fast and causing the tree to become unbalanced.

Insects and Diseases. Probably the worst insect pest of apples is the codling moth. This is a worm that eats the core of the apple and then tunnels out to the surface, leaving a small hole. It leaves a mess at the core, but you can cut around the outside hole and still have apple to eat. This pest is difficult to control. If it becomes a problem for you, purchase a pheromone trap at the garden center, to attract the moth that lays the eggs of the larvae that do the damage.

Two other insects you may encounter are mites and aphids. They don’t eat the fruit itself, but can feed on the foliage and severely reduce the vigor of the tree. You may already have experienced aphids if you have a vegetable garden; the best way to control them is to knock them off the plant with a hard spray from the hose, or to apply insecticidal soap, which suffocates them. See Chapter 6 for more details.

Mites are smaller, spiderlike insects that also suck plant juices. They are so tiny that you may see their damage before you see them; you can use a magnifier to identify them. Damage shows as speckling on the leaves or as small webs underneath the leaves. Mites are harder to dislodge with water, but the soap compounds will also work on them. Predatory mites that can help keep the pest mites in check are also available.

Diseases that attack apple trees are a serious concern for commercial orchardists, but represent less of a threat for container gardeners. In the highly controlled environment of one carefully watched container, it is less likely that diseases will get a foothold. The very best advice we can give you is to search out apple varieties that have been bred for resistance to diseases. Apple scab is the biggest problem; read catalog descriptions closely for varieties that are resistant to it.

Harvesting. Now the real fun comes in, the result of all your tender loving care. In the third year, generally speaking (second year for columnar types), you can start picking your own apples. Compared with store-bought fruit, tree-ripened apples are far superior, sweet and delicious. You may find yourself saying, “Now this is what apples are supposed to taste like.”

All apples must be picked when fully ripe to appreciate their richness and flavor; they do not ripen after being picked. But how do you know when they are ripe? By their color, the ease with which they can be picked, and their firmness and taste. Yellow apples turn from a greenish yellow to a brighter yellow as they ripen; red apples turn a darker red. Apples are also usually ripe when they separate from the tree with just the tiniest tug, or when they begin falling. (However, insect-damaged fruit will sometimes drop prematurely, so you should try tasting one before picking the remainder.) Of course, once you have bitten into a fruit, it will spoil whether it is ripe or not.

Another sign of ripeness is firmness. Try pressing the fruit with your thumb; if it gives a tiny bit, it is probably ripe. Late-ripening varieties are often good keepers and can be stored in a cool room or garage for several months; a month or two of cool storage actually develops better flavor. Early-ripening varieties should be kept in the refrigerator and can usually be stored for a month or two.

Varieties. Apples can be easy trees to grow in containers, and a number of disease-resistant varieties bear delicious fruit. Concentrate on these varieties, and you’ll go a long way toward avoiding disease problems.

As you browse through mail-order catalogs, remember to focus first on trees with dwarfing rootstocks (unless you want to try columnar types). The next question is, what variety should you choose for the top of the tree? For container growing, it is best to stick with what are referred to as low- to medium-vigor varieties, meaning that they do not put on a great deal of lush growth but stay relatively small overall.

Here are some recommended varieties, listed in order of ripening. All require a minimum of 600 hours of winter chill.

• Dwarf Varieties. A very early ripening variety, Wynooche Early is disease-resistant and easy to grow. Selected by fruit enthusiast Howard Hughes in Aberdeen, Washington, it bears medium-size greenish yellow fruit with a red blush. Very flavorful and juicy, Wynooche Early ripens in early to mid August, and also stores well.

Akane, from Japan, is a disease-resistant variety that bears medium-size bright red fruit with snow white, juicy, flavorful flesh. A low-vigor tree, it is a good choice for container growing. Akane ripens in late August.

Free yourself of worries about apple scab and other diseases; Liberty is one of the best disease-resistant varieties. The large red fruit with firm and flavorful flesh is great for both eating out of hand and cooking. The tree has an attractive compact form and dark green glossy foliage. Ripens in mid September.

Spartan bears tasty, large, dark red fruit with flavorful, firm, juicy flesh. Very disease-resistant and of medium vigor, this is a good variety for container growing. Spartan ripens in late September into October and can be stored for several months in a cool room or under refrigeration.

Calville Blanc d’Hiver is a very large, tasty French dessert apple. The fruit is bright yellow with firm, pure white, sweet-tart flesh. It stores very well and is great for both fresh eating and cooking. Calville Blanc is quite disease-resistant and compact in size. The fruit ripens in mid to late October.

• Columnar Varieties. Two very fine new columnar varieties come to us from Canada: Scarlet Sentinel and Golden Sentinel. Both were bred for their disease resistance and high-quality fruit. Scarlet Sentinel bears attractive red-and-yellow medium-size fruit with sweet, flavorful flesh. Golden Sentinel has large yellow apples with crisp, juicy, flavorful flesh.

Scarlet Sentinel is a low-vigor tree, which makes it an easy plant for container growing. Golden Sentinel is somewhat more vigorous but still a good variety for containers. Both will flower and bear fruit the year after you plant them.

North Pole, also bred in Canada, has a Macintosh-type fruit with dark red, large, juicy apples. It ripens earlier than the Sentinels, but is somewhat more susceptible to apple scab.

• Crabapples. These can also make great container plants and are particularly pretty in bloom. Crabapple varieties to consider are Dolgo, Callaway, and Red Siberian (which also has red flesh).

Theme Garden

Dinner at the Four Seasons

Our mental image of lush vegetable gardens always includes a Norman Rockwell sense of hot summertime—the proud gardener wiping away a sheen of well-earned perspiration while lugging baskets spilling over with corn, potatoes, beans, and world-class tomatoes. It’s true that summer is the time of greatest bounty, but let’s not blindly assume that the other three seasons are barren. With careful planning and reasonable cooperation from the weather, it is possible to harvest homegrown goodies in all four seasons.

Everything in this garden will be planted in one large container, at least 2 feet across. In areas of severe winters the plants may require protection; see Chapter 1 for tips.

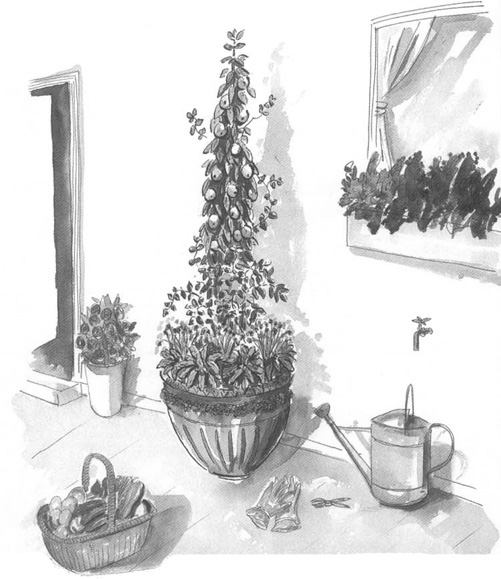

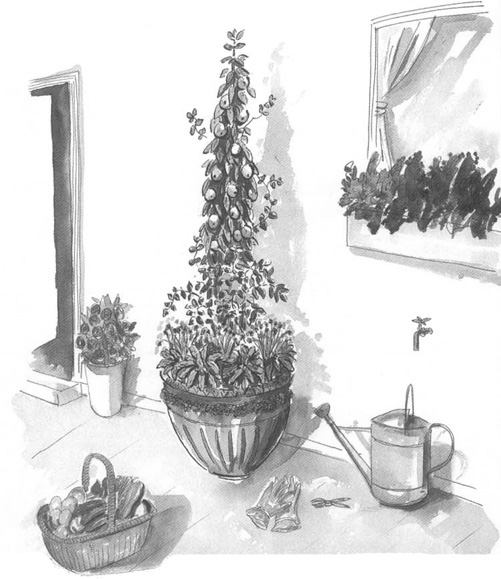

The centerpiece of this garden is a columnar apple tree. (Stop here, take a look at page 287, and decide whether your apple tree needs to be moved for the winter; if so, plan your strategy before planting the container.) Columnar apples don’t look anything like typical apple trees. They don’t have broad branches extending out from the trunk with apples dangling from the branches. In fact, they don’t have any branches to speak of, just very short stubs sticking out from the trunk; until you look closely, you would think the apples were growing directly from the trunk.

Jim Gilbert, a knowledgeable and generous nurseryman who specializes in fruit trees, once playfully described columnar apple trees as looking like Brussels sprouts. Did you ever see, at a farmers’ market or roadside stand, an entire harvested plant of Brussels sprouts? The farmer chops off the roots and removes all the big floppy leaves, and all that remains are the tight little sprouts spiraling around the otherwise bare stem, which looks a lot like a green club with knobby spurs. That’s very much what a columnar apple tree looks like, except the “stem” is longer and the “sprouts” are larger.

What’s amazing about these trees, though, is that they produce full-size apples, of whatever variety you selected when you purchased your tree. They may look unconventional, but the advantage they offer gardeners with limited space is immediately obvious.

Early in the spring, sow seeds of Malabar spinach at the base of the apple tree. This vining type of spinach will climb up into the tree, the better for you to enjoy the rich coloration of its stems and leaves. You’ll never get a huge harvest at any one time, but you will be able to take a few leaves of spinach now and then to jazz up your salads for months.

Also in springtime, plant several clumps of chives underneath the tree. They help prevent apple scab (a serious disease), provide you with delicious fresh chives practically forever, and in early summer produce endearing little puffball flowers in a soft shade of lavender. Put the chives in as soon as you can; they may die down in very cold winters, but they are a perennial and will come back next spring, stronger than ever.

Beside the chives, plant seeds of regular spinach, any variety. The contrast between the emerald green of standard spinach and the rich magenta of the Malabar is gorgeous. Sow the seeds as early in the spring as possible; enjoy fresh spinach all spring and early summer, until the weather gets so hot the plants fizzle out. At that point, yank out the bolted spinach and in its space set out one or more plants of dwarf basil and several Tagetes marigolds. The basil will do its magic up until the first cool days of fall, and the marigolds will last even longer than that.

When crisp autumn weather kills the basil plants, replace them with cheerful pansies. Select pansies in shades of purple and blue and mix them in among the bright yellow marigolds for a beautiful color combination. The pansies will outlast the marigolds, blooming all the way through early winter; if you clip them back and add a layer of mulch before a serious cold snap actually freezes them, they’ll sometimes come back with a new burst of blooms in early spring.

The harvest: chives in spring, summer, and fall; spinach in spring and early summer; basil and marigolds in summer; apples in early fall; pansies in autumn and early winter. All in one handsome container, taking up just 2 to 3 feet of floor space. Nice work!

Rose Marie says: A few years back, our friend Jim Gilbert, of Northwoods Nursery, introduced the variety North Pole into this country, and so last year I decided to try it.

Everything went extremely well at first. The young tree looked suspiciously like a buggy whip until it started leafing out, but once that happened it did indeed look like a tree, albeit a very skinny one. I had planted Malabar spinach at the base, and it looked wonderful vining up into the tree.

Then, disaster. One night, a deer from the nearby wooded area found the tree too strong a temptation and ate all the leaves—apple and spinach. A healthy young tree, growing like a champ, was transformed into a buggy whip again. I felt guilty about getting angry at Bambi, but angry I was.

This story has a moderately happy ending. With lots of coddling, the tree lived. It is not as vigorous as it would have been had it not been set back by the deer attack, but it did eventually recover—most plants are a lot tougher than we give them credit for. And we have since moved the container out of Bambi’s reach.

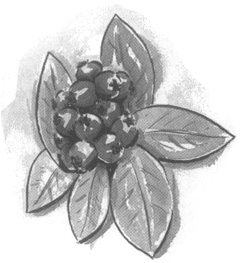

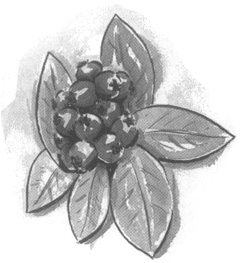

Plump blue beads dusted with a soft, silvery blue powder, hanging in clusters from a neat little shrub, just begging you to pick them. Can you imagine yourself stepping out onto the deck or patio on a summer morning and picking a handful of these sweet, dew-covered berries to plop into your breakfast cereal?

Blueberries are a real joy for container gardeners because they are so easy to grow and produce so well in small spaces. They are striking in appearance, so handsome that many traditional gardeners consider them ornamental plants that also produce delicious fruit. The dainty leaves bud out with reddish tips, then turn dark green with subtle hints of pink and aqua as they mature. They form a canopy over clusters of tiny white or pink flowers shaped like miniature Tiffany lamps. In the fall, the foliage turns a flaming red with brilliant yellows and oranges, a real visual treat. Artists like to paint pictures of blueberries on the bush because there are so many interesting colors intermingled. But the main reason for growing blueberries is because the berries are so delicious: sweet and just slightly tart when ripe, with a distinctive, nothing-like-it taste. One or two plants will provide plenty of berries for eating fresh, making syrup, adding to muffins or pancakes, and even some extra to pop in the freezer for later.

Blueberry Basics. Blueberries grow on small to medium-size twiggy bushes, and are grouped into three basic types: highbush, which reach 5 to 6 feet; lowbush, which creep by underground stems and get only a foot or so tall; and rabbiteye, which can top out at a lofty 15 feet. They’re all terrific in their place, but a container is not that place. (One exception is a highbush type that can be grown in a container if it’s large enough. You might think of it as something between a large shrub and a small tree, providing shade for more tender plants growing in containers beneath it. Highbush blueberries are the ones you’ll find in your supermarket.)

Fortunately for us container gardeners, breeders have developed a half-high blueberry (sometimes listed in catalogs as a dwarf blueberry) by crossing the high and low varieties; these are the ones most often chosen for containers.

Planting. If you order from a mail-order catalog, you’ll probably receive a bare-root plant. At the retail garden center in early spring, you may find either packaged bare-root plants or potted plants, usually in 1- or 2-gallon containers, that are just beginning to leaf out. Sometimes in early summer you can also find larger plants that actually have fruit on them. Pick bushy plants with multiple stems (if possible) and bright green branches. If a plant has only one main stem but looks really healthy, that’s okay; it probably just needs another year in good soil to send up more stems. But if you see a lot of brown or black brittle twigs at the ends of the branches, pass on that plant. Review the general directions on pages 290 to 291 for planting bare-root and container-grown perennials.

Large wooden planter boxes, the kind used for small trees, are excellent choices for blueberries because they drain well, aren’t damaged by the weather, and look great. They should be at least 2 feet by 2 feet by 2 feet, and larger wouldn’t hurt. Half whiskey barrels also are good choices, but make sure they have several drainage holes in the bottom. Clay pots are not the best choice, as they may crack in freezing weather.

Blueberries like soil that drains well (so the roots aren’t waterlogged) but holds a light, constant moisture level. Finding that delicate balance is not as difficult as you might think: it’s only a question of using a planting mix that has a high proportion of organic material such as peat moss or sphagnum moss. Those ingredients also give you something else blueberries require: a soil that is more acidic than alkaline (see the Soil section in Chapter 5 for more on this). Often in garden centers you will find potting soil marked as ideal for rhododendrons, azaleas, and camellias; that’s also perfect for blueberries.

Pick the spot for your container carefully, because once it’s filled with soil and planted it will be heavy and hard to move around (unless you add casters to your wooden container or set it on a wheeled base). Remove the plant from its nursery pot (if you start with a containerized plant) and fill the container partway with potting mix. Loosen the roots if they are compacted, but try to keep the original soil ball intact as much as possible. Set the plant in position so the top of the soil ball is about 3 to 4 inches below the rim of the new container. Fill in with soil, raising the level of the plant as you go if necessary; the crown of the plant (where the topmost roots end and the stems begin) should never be any deeper than it was in the nursery pot.

Blueberries like their roots right at the surface of the soil but with a light mulch over them. Water thoroughly to settle the plant, then lay 2 to 3 inches of coarse bark, moss, or pine needles over the surface of the soil. This will help hold in moisture and insulate against temperature extremes, while still letting air get to the surface roots.

Success with Blueberries. Blueberries are, by and large, quite easy to grow. But there are a few things that will help them thrive.

Watering. First, they must have almost constant moisture but not be standing in water. A drip watering system is ideal, if you can provide it; the slowly dripping water moistens, but passes on through, the porous soil. Otherwise, daily watering will be necessary in hot weather. Check the soil with your finger; it should always feel like a damp, wrung-out sponge.

Maggie says: The Pacific Northwest is blueberry heaven. Here in this land of gracious-plenty rainfall and acidic soil, you’d think all anyone would have to do is stick a blueberry stem in the ground and walk away, then stroll back in the summer to pick the berries. Yet I learned an important lesson from my friend Barbara Ashmun, whose gorgeous garden has several low-lying spots where water doesn’t drain. After years of struggling with these mini-bogs, she found that the secret of growing blueberries there was to put them in containers. So here she is, with all the room in the world (nearly an acre), growing 5-foot blueberry bushes in ordinary black plastic nursery containers, with tremendous success.

Soil. Even though blueberry plants love acid soil, it is possible for it to become too acidic. When that happens, the plant is unable to take up iron from the soil, creating an unhealthy condition called chlorosis. Fortunately, the plant gives you a very clear clue: the leaves turns yellow except for the veins, which stay dark green. You can correct this condition by adding a small amount of lime. The best is a form known as chelated iron (also called sequestered or micronized iron); it is readily absorbed by the plant and you see results quickly, thus eliminating the temptation to add too much lime, which would make the soil too alkaline.

The best course of all is to prevent this condition from happening by always using a fertilizer with the proper acid balance (such as those recommended for rhododendrons, azaleas, and camellias). Blueberries are heavy feeders, so starting in early spring, feed the plants once a month at the recommended rate. Around mid August, begin tapering off; do not fertilize at all during the fall and winter.

Winter protection is important if you live in a cold climate. Blueberries are naturally very hardy plants, but when grown in a container, their roots are exposed to cold air from all sides. If some of the branches die, new ones will grow; but if the roots die, the plant is gone. When cold weather arrives, move the container into a more sheltered location, or wrap it in some insulating material (see page 288) during the coldest times.

Winter chill is also a factor with blueberries (see page 286). Most blueberries need around 800 hours, although there is one that southern gardeners can grow successfully (see Varieties, below).

Pruning. Your blueberry plants will give you years of berries, especially if you prune the mature plants lightly. The pruning process is not as elaborate or as precise as with some of the tree fruits, and the improvement in production is noticeable. Don’t do anything the first two or three years. Each year thereafter, early in the spring, completely remove some of the very oldest branches (with the darkest and scraggliest-looking bark), and clip off any twigs that seem unusually thin and weak. You’ll have much larger berries (but fewer of them) if you cut back the remaining stems by about one-third to one-half. This forces new growth, and new growth bears the largest berries.

Harvesting. One of the surest signs that your berries are ripening will be the appearance of visiting birds. Robins, jays, starlings, and a few others love blueberries. When you see the very first berries starting to turn from green to blue, you’ll need to protect your crop by covering the whole plant with bird netting. The netting should be raised high enough over the plant that birds can’t reach through for a sneak attack, and the bottom should be secured so they can’t slip in under the net.

Different varieties of blueberries ripen at different times, but you can tell when they’re ripe when most of the berries in a cluster turn dark blue. Pick one of the darkest and taste it. If it’s very tart, wait a few days. When fully ripe, they should not make you pucker. The berries do not all ripen at the same time, so you can harvest over a period of two to three weeks for each variety you are growing.

Varieties. All blueberries are self-fertile, but you will get much larger crops if you plant at least two varieties for cross-pollination.

Earliblue, a highbush type, is a vigorous upright plant with good cold-hardiness. It has large fruit that ripens early (June). Bluecrop, another highbush, has large, light blue berries in midseason (July); it is very productive, cold-hardy, and more drought-tolerant than most.

Patriot, a half-high type with upright growth, is cold-hardy; it ripens midseason (July), with large, good-flavored fruit. Northblue, also a half-high type, is only 20 to 30 inches tall at maturity. For such a small plant it is extremely productive, with masses of large, slightly tart berries in mid summer.

Northsky is a half-high type especially recommended for very cold climates. It grows only about 18 inches high, but spreads to about 3 feet, and ripens in mid summer.

Sunshine Blue, a compact half-high with pretty pink flowers, is the one for southerners. It is less finicky about acid soil than most blueberries, and needs only 150 hours of winter chilling. (Interestingly, it does very well in colder climates, too.) About 3 feet tall, with large berries in July.

Citrus trees are considered almost exotic by those who live where citrus doesn’t grow naturally. When oranges were first introduced in Europe, they were so coveted that wealthy families built special glass houses to grow them in. These elaborate and expensive orangeries were the forerunners of present-day greenhouses. But you don’t need a fancy orangerie to grow a citrus tree. With reasonably cooperative weather and good winter stewardship, you can grow one in a pot on the patio.

Citrus trees have handsome foliage and deliciously fragrant flowers. In California and Florida, they are often massed together as hedges. Very small plants are also sold all around the country as houseplants, and those who grow them are happy with their good looks even if they never produce fruit. Somewhere between huge hedges and dainty houseplants are the diminutive citrus trees of container gardens, and they offer the same joys—beautiful foliage, luscious flowers, and, with any luck, wonderful fruit.

Citrus Basics. All citrus fruits grow on small to medium-size trees that thrive in subtropical climates where the days and nights are about equal in length and temperatures stay above freezing. Some of the hardier varieties of citrus will take a light frost of short duration, but none will survive freezing weather.

The fruits that must develop sugars to be palatable—orange, grapefruit, tangerine, tangelo—need longer time in hot weather, and so are questionable for colder areas unless you’re interested only in aesthetics. But fruits that are naturally sour, such as lemons and limes, are possible in all but the coldest climates, with some extra attention in winter.

Planting. The citrus trees you’ll buy for your container garden are grafted. The top portion is selected for its superior fruit quality, and the bottom portion, the rootstock, is selected for its dwarfing quality. This is what makes these trees small enough to grow in containers. You can see the graft as a diagonal scar on the trunk. If later on you see a vigorous branch suddenly zooming out from the trunk, look at it closely; if it’s coming from below the graft, prune it off completely, back to the trunk; any fruit it produces will be undesirable, and it will draw vigor from the “good” branches.

Citrus plants have a shallow, spreading root system with surface roots right at the top of the soil, which don’t like to be covered. Whether you start with a bare-root or potted plant, keep this in mind. And review page 290 for the basics of planting both types of perennial plants.

Use a large container that will hold at least 15 gallons of soil, such as a redwood tub, half barrel, or large terra-cotta pot. If you live in a cold climate, it’s a good idea to set the container on a plant trolley with wheels, as it will have to be brought inside for winter. Citrus plants like very rich, acid soil with a high content of organic matter. If you can find a commercial potting mix formulated for rhododendrons or camellias, that’s perfect. Otherwise, use an all-purpose soil and mix in some extra materials that will increase the organic content: peat moss, sphagnum moss, and commercial bagged compost all will work.

Fill your container about three-quarters full and spread the roots evenly over the top; fill in around them with more soil. When you’re done, you want the roots to be just below the surface of the soil. Tamp the soil in around the root ball and water it well to settle the roots. Spread a light, airy mulch such as wood chips over the exposed roots to keep them from drying out.

Success with Citrus. If you live in southern California, the Southwest, or Florida, you already have what citrus needs most: heat, and lots of it. Apartment dwellers in those parts of the country need not envy their friends with large yards; both can grow citrus with equal ease and equal success.

The farther north you live, the more attention you will have to pay to wintertime protection, and here container gardeners have something of an edge because they can move their trees inside for the winter.

Grow citrus outside during the frost-free months; they must have strong light and lots of moving fresh air plus all the heat you can give them. They love to be close to a wall or structure where they will get reflected heat. On the other hand, they need filtered light shade from the harshest summer afternoon sun to prevent sun scald.

Leave the citrus plants outside until the night temperature starts to drop to about 45°F. Then begin to move them gradually into a protected, moderately warm area for the winter. They need as much light as you can manage. Many people grow them inside in a south-facing window and provide supplemental light during stretches of dark, overcast days. Most citrus plants flower around New Year’s Day, and if they are indoors you get to enjoy the heavenly fragrance. Then in the spring, after there is no more danger of freezing, move the plants back outside.

These are heavy feeders. Every month (except during the winter) give them an application of fertilizer formulated specifically for citrus (anything labeled “high acid” or “for rhododendrons” will also work). They also respond well to an occasional booster of fish emulsion, two or three times per year.

Water frequently, but be very careful that your soil is draining well. Citrus roots are especially vulnerable to being smothered by waterlogged soil. Also, don’t wet the trunk while you’re watering.

Citrus do have some pest problems that you need to watch for. Red spider mites are one, and if you keep the plant misted and watered regularly you can spot them before they get ahead of you. If mites are present, you’ll see the water cling to very fine webbing at the point where a leaf stem is attached to a branch. Washing the plant with a mild soap-and-water solution will help (you can do this in the shower) but you’ll probably need to spray the leaves with an insecticidal soap spray (see Chapter 6) on a regular basis. Remember, never use a systemic insecticide (one that is taken up by the roots) on anything you are going to eat!

The other pest you may encounter is scale, an insect that is very hard to spot. They appear on the stems and underside of the leaves as small oval, translucent spots that look like drops of wax. Use a cotton swab dipped in rubbing alcohol to clean them off. Inspect every leaf, stem, and branch regularly to control scale.

If your tree starts to drop a lot of leaves, it’s hungry. Prune lightly and feed it; it should recover quickly.

Pruning is not a major chore with citrus, but since fruit forms on new growth, you want to prune regularly to encourage new branches. Starting about the third year, cut back all new branches by about one-third of their length. Also, check the plants regularly for broken or extremely weak branches, and cut them off.

Harvesting. It takes about a year for citrus fruit to ripen. This is why you often see blooms, green fruit, and ripe fruit all at the same time. Blossoms from last year will have formed ripe fruit just as the plant is beginning to bloom in the present year. Fruit is ripe when it is fully colored and comes away from the branch easily.

Varieties. All citrus are self-fertile; you don’t have to worry about planting two varieties for pollination as you do with some fruits.

• Grapefruit, Oranges. Ruby is the small, pink-fleshed grapefruit you see in the supermarket. Remember, if you hope to eat your fruit, all grapefruit varieties need lots of heat to sweeten up and color properly. The same is generally true of oranges, although the navel types take less heat to ripen than juice varieties. Robertson is one very productive variety of naval orange, and a fine small-size tree.

• Lemons, Limes. Container gardeners outside the Citrus Belt will probably have more luck with lemons and limes (although of the two, limes are far more tender and easily damaged by cold). Ponderosa lemon is a small tree that bears young, with very large fruit. Pink Lemonade is a beautiful lemon plant with green-and-white variegated foliage. The rind of the young fruit is striped and the flesh is pink. It does not, alas, make pink juice.

Perhaps the very best choice for marginal climates is the Meyer lemon. While not a true lemon in the botanical sense (it is a cross between a lemon and an orange), it makes a wonderful substitute. The tree is naturally small and thus good for containers; the fruit is rounder than the familiar pointed oval, and a darker golden yellow; and both the flesh and the peel have a somewhat sweeter, mellower taste. It is easy to grow, blooms and fruits almost constantly, and best of all is more cold-hardy than most citrus. The one you are most likely to find is called Improved Meyer Lemon, a disease-resistant cultivar.

The Key lime, also called Mexican lime, is very vulnerable to cold weather. An interesting alternative and a very good conversation piece is the Kaffir lime. This is the one to grow if you enjoy Southeast Asian cuisine. Its fresh leaves are widely used for seasoning, and the fragrant flowers are edible. The fruit itself is not used in cooking, although the peel sometimes is; the tree is grown for the leaves.

Bursting with flavor, exquisitely beautiful to look at, and very nutritious, currants and gooseberries are ideal for container gardens because the bushes are small; even when fully mature, they seldom get taller than 4 feet. Both make very attractive plants: handsome shrubs covered in season with small fruits that positively glow in the sunshine. But the real reason for growing them is the incomparable taste of the fruit; sweet and tart at the same time, they are like nothing else you’ve ever tasted. In fancy markets, you would pay an arm and a leg for a tiny basket of these gems. Imagine the pleasure of having your own supply right at hand.

It’s possible you have never tasted either of these fruits in their fresh form. Although they have been a staple in European gardens for centuries, where they are prized for fresh eating and for the wonderful preserves, pies, and other sweets made from them, they are not very well known to most Americans.

If your only experience of gooseberries is a jar of commercial jam from a gourmet shop, and the only currants you’ve ever tasted are the dried, wrinkled specks sold next to the raisins (which are made from small grapes and are not currants at all), you’re in for a delicious surprise. And if you grow the sweeter varieties, you can finish off your next dinner party by presenting a beautiful crystal dish filled with black currants, red currants, and pink and green gooseberries, glistening like jewels. Your guests will have an unforgettable treat.

Besides their exceptional taste, gooseberries and currants are rich in vitamins B and C, calcium, and potassium, and are a good source of dietary fiber. That may not be your primary reason for growing them, but it’s a nice extra benefit.

Currant and Gooseberry Basics. These two fruits are closely related, but there are important differences between them. Currants come in three colors: jet black, red, and white. Gooseberries can be either red or greenish yellow, with distinctive stripes running from top to bottom, like longitude lines on a globe. Gooseberries are bigger, about the size of a marble; currants are tiny, rarely more than ¼ inch in diameter. Currants are more strongly flavored; gooseberries are often sweeter. These minor differences aside, the two are botanically very similar, and they need the same growing conditions and care.

Size. Even when they reach their full size, currants and gooseberries are relatively small plants, 3 to 4 feet in height and diameter. Gooseberries tend to form round-headed bushes with branches close to the ground. Currants are typically more upright.

Pollination. All gooseberries are self-fertile, and will bear good crops without cross-pollination. So are most—but not all—currants. Read catalog descriptions for currants carefully. If you have a variety that is not self-fertile, you must plant another variety near it (ideally in the same pot) for cross-pollination by bees and other insects. The flowers themselves are small whitish bells, not especially noteworthy in appearance but essential for fruit.

Hardiness and Chilling Requirements. Both types of plants are deciduous, and will lose their leaves with the coming of fall. The autumn coloration is nothing to write home about, but it does serve as a signal that the plant is about to move into dormancy, which in turn is your cue to mobilize wintertime protection.

Currants and gooseberries are much hardier than most fruits. In traditional gardens they can withstand temperatures of –25°F and below, some as low as –40°F. Remember, though, that in containers roots are more vulnerable to damage from freezing than they would be if planted in the ground, and so those numbers need to be adjusted. To be on the safe side, make sure the roots of currants and gooseberries are kept above 20°F.

On the other hand, don’t be in too much of a hurry to tuck your plants in for the winter. With gooseberries and currants, which are native to colder regions of the earth, it’s a good idea to leave them in a natural environment, complete with hard fall frosts, as long as possible. This ensures they get the 600 to 700 hours of winter chill they need. (See page 286 for a complete explanation of winter chill.) Unfortunately, gardeners in the far southern parts of the country will have a hard time accumulating 600 hours at temperatures between 32° and 45°F.

It’s only when the thermometer drops below 20°F and threatens to stay there for a long period that you should swing into action. Complete details on the two basic strategies for winter protection—wrapping and moving the container—are described on page 289. Be sure to remove the insulating wrap, or bring the container back outside, once the danger of severe freezing is past. With the coming of warm weather, your plant will be ready to grow and reward you once again with a bountiful harvest of fruit.

Planting. You can plant your currant or gooseberry at almost any time of year (except the dead of winter), but the widest selection of varieties is available in the spring. From both mail-order and retail nurseries, what you’ll find in the spring will be bare-root plants (see page 290).

Potted plants are often available in summer and fall, usually in gallon-size pots. Before you buy one at the garden center, slip the whole thing out of the pot and inspect the roots. If you see a tangled mass of roots growing in circles, the plant is rootbound; pass on it. Plants that start with such a congested root system are more difficult to get established because the tangled roots have a hard time taking up water.

Because currant and gooseberry plants are smaller overall, you can use a smaller container for them than you would for another fruit tree. They are also shallow rooted, so a container that is proportionally wider rather than deeper is best. Even something as small as a squat 5-gallon size will do for several years; if you start with a 7- or 10-gallon container, the plant can grow even longer before it needs repotting.

Any planting mix that drains well will work. Fill the pot about halfway with soil and then prepare your plant. If you’re starting with a potted plant, remove it from the nursery container and loosen the roots by digging your fingers into the root mass and pulling out the larger ones; if any are noticeably longer than the others, trim them back to equal length. Unwrap bare-root plants and spread out the roots; prune back any that are broken or excessively long. Identify the crown of the plant; the point low down on the main stem, just above the topmost roots, where the stem becomes smaller and darker.

Set the plant in the pot, spread the roots out as evenly as possible, and begin filling the pot. When you’re done, you want the crown to be about 1 inch below the rim of the container. You may need to lift the plant gently as you add soil, to keep it at the correct height.

If you started with a potted plant, a good rule of thumb is to have the plant in the final container at the same level as it was in the nursery container. Finish by watering the container thoroughly to settle the plant and make sure the potting soil is in good contact with the roots.

For bare-root plants, it’s a good idea to cut back the top after planting. This helps balance the top with the root system, part of which was lost when the plant was dug up at the nursery. Cut each branch by about a third to half of its original length. At the same time, remove any branches that are broken or rubbing against other branches.

If you started with a container plant, you won’t have to do any pruning other than removing broken or crossing branches. The only exception to this would be if you purchased an older potted plant that was seriously rootbound or had lots of weak growth from the previous season. You should cut back this sort of plant severely, leaving only 2- to 3-inch stubs of the previous growth. This may seem to be harsh treatment, but it will help the plant generate healthy new growth (see the Pruning section below).

Success with Currants and Gooseberries. Currants and gooseberries make wonderful container plants. They take up little space, produce good crops of delicious fruit, and are bothered by few pests and diseases. Follow these basic growing practices, and you should enjoy many years of tasty harvests.

Watering. If you’re planting a bare-root plant in the spring, it will likely be dormant or just starting growth. Until the roots have begun active growth, they cannot take up much water, and overwatering can cause more harm than good. Check the soil every few days; just poke your finger down an inch or so. If it feels completely dry, give the container a deep watering, and then no more until the soil is dry again.

Within a week or two after planting, if the weather is warm, your plant will begin active growth. When you see buds and new leaves forming and the stems getting longer, you’ll know the roots are active, too. At that point, you should begin a regular watering schedule. Deep waterings once a week should be enough, except during the hottest weather, when you will need to keep a vigilant eye. At the first sign of wilting, water heavily.

If you start with a container plant in the spring or summer, you will need to water it more often at first than you would a bare-root plant. Keep in mind that the roots require several weeks to fully grow into the potting soil in the new container. During this time, the soil immediately around the root system (the soil that was in the original nursery container) can dry out while the surrounding oil in the new pot can feel moist. Be sure that you water close to the plant to get water into the root zone. After a few weeks, the roots should have grown into the new potting soil and you can begin the same watering schedule as described for a bare-root plant.

In late summer, begin holding back on water to help your plant harden off and prepare for winter.

Fertilizing. The fertilizer information given in the Apples section also applies to currants and gooseberries; see page 297.

Pruning. To continue looking good and pumping out berries, currants and gooseberries need to be pruned every year. The process is not difficult, but a quick botany review will help you understand why this is necessary.

In some plants, the cellular activity that produces buds for flowers (and ultimately fruit) begins a year in advance. So a branch that forms in year 1 will not actually bear fruit until year 2. The first year nothing of significance happens, at least on the surface; the second year, that same branch will set flowers and fruit.

Gooseberries and currants are of this type; they bear fruit on stems that are two years and three years old. But unlike some other fruit plants, the individual branches do not continue to bear fruit forever. After the third year they lose vigor, and productivity drops way off. To say this a different way, currants and gooseberries form fruits on two- and three-year-old branches—not on one-year-old branches (usually), and not on four-year-old branches. For a continuous supply of fruit, then, you need a continuous supply of new shoots. And that is accomplished by regular pruning. Prune when the plant is dormant, either in winter if your winters are relatively mild, or in early spring before the plant starts growing for the season.

For these two fruits, pruning has three objectives:

1. To shape the plant in the form of an open bush.

2. To maintain equal proportions of one-, two-, and three-year-old shoots.

3. To distribute the fruit-bearing shoots and the current year’s growth evenly around the bush.

The difficulty in explaining the process is that we humans tend to think of age in human terms. In a baby’s first year of life, we say the baby is so many months old, and doesn’t become one year old until the end of the twelfth month. So in its second year of life, a baby is one year old. With plants, we calculate differently. The stem or branch that grows in one season is one year old that same season; the following year, that same branch is considered to be two years old. (Gardeners use the term “wood” for all branches and stems; you’ll hear them refer, for example, to “two-year-old wood.”)

It’s obvious, then, that to properly prune these bushes, you need to be able to tell the older from the newer stems. The short answer is that the older they are, the darker and more scaly the bark.

The pruning process is not complicated. With just a bit of practice, you can probably do it in less time than it takes us to explain it. We will describe how to prune, one year at a time, using imaginary colored ribbons to distinguish each year’s growth. You could also use ribbons literally, although in bright sun the colors may fade over time. An alternative is to circle each stem with a strip of tape for each year of growth.

1. Early spring, year 1. Plant your new plant; if you started with a bare-root plant, shorten the stems as described in the Planting section above.

2. Summer, year 1. Whether you have planted a bare-root or potted plant, let it grow freely the first year. Mentally (or literally) mark all the new stems that grow this spring as “red” stems. There is a chance of a few fruits being produced the first summer, but primarily this is the year for the plant to get established.

3. Early spring, year 2. Select five or six strong “red” stems that are well spaced around the plant; cut off the rest, down to the base.

4. Summer, year 2. The “red” stems are two years old and bear fruit. Mentally designate the new stems that grow this year as “blue.”

5. Early spring, year 3. Prune away several of the “red” stems, leaving three or four good ones. Choose five or six strong “blue” ones, evenly spaced around the bush, and cut out the rest.

6. Summer, year 3. The “red” stems are three years old and the “blue” ones are two years old; both bear fruit. Designate the stems that grow this summer as “yellow.”

7. Early spring, year 4. Prune away all the remaining “red” stems; their productive life is over. Also, prune away about half the “blue” stems, leaving the rest for this summer. Select five or six well-spaced “yellow” stems, and remove the others.

8. Summer, year 4. This summer the “blue” stems are three years old and the “yellow” ones are two years old; both will bear fruit. This year’s new growth is designated “purple” and will be the source of fruit-bearing stems next year.

And so on.

This is the basic idea. With each year’s pruning, you can leave more or fewer shoots than the numbers suggested here, depending on how big you want your plant to be.

To put this entire process in a nutshell: each spring, remove the shoots that are more than three years old, and thin out the others so the plant doesn’t get too crowded. What is important is continuous shoot renewal, so that vigorous new growth is always coming on to replace the old.

Insects and Diseases. The most bothersome disease of both gooseberries and currants is powdery mildew, which shows up as a white coating on the leaves (see Chapter 6). Severe infections can stop shoots from growing, which reduces the crop of fruit for the following year. While it doesn’t usually bother the fruit of currants, powdery mildew can seriously damage gooseberries. The best preventive measure is to plant disease-resistant varieties; at the first sign of mildew on your gooseberry bush, begin treatment as described in Chapter 6.

Insects that bother gooseberries and currants include currantworm and aphids. Currantworm is easy to control but hard to see at first. The worm is a green caterpillar that seems to be able to make itself the exact color of the leaves. It starts by eating the edge of the leaves and, if not controlled, can defoliate the plant. Rotenone spray, a natural insecticide, gives excellent control of this pest. Aphids cause discoloring and puckering of the leaves. They are not always easy to control, but insecticidal soaps and simply spraying them off the leaves with your garden hose can be effective; see Chapter 6 for more specifics.

Harvesting. Most varieties of currants and gooseberries ripen in mid summer. Your cue is the change in color. Currants change from the green of young fruit to the color of the variety you have planted: black currants will become jet black, red currants will become beautiful bright red and translucent, and white currants (which are basically a white version of red currants) will become pale white and strikingly translucent, with their tan seeds visible inside the berries.

After the fruit has changed color, the next test of ripeness is taste. When fully ripe, all currants will have a complement of sweet and tart flavors. Ripened currants are easy to pick. Some varieties will be in long clusters called strigs; you can simply pinch off the entire strig. Others will come off easily individually. After harvesting, the berries will keep at room temperature for a day or two, and a week or so in the refrigerator. For longer storage they can be frozen or dried.

Gooseberries also change color when ripe, from green to yellowish green or red, depending on the variety. They also soften a bit when fully ripe. Again, the best way to determine their ripeness is to taste one. Gooseberries are usually sweeter than currants, with a milder flavor. They are picked individually and will keep somewhat longer than currants. They can also be frozen or dried for long-term storage.

Varieties. Because currants and gooseberries have been cultivated for so long, many varieties have been developed. In recent years growers have concentrated on improving disease resistance while maintaining large fruit size and good flavor. The varieties listed here are just a sample of the many available. All varieties listed are self-fertile.