CHAPTER 7

VEGETABLES

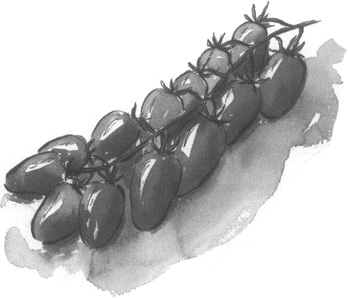

A recurring theme of this book is that people who grow their own vegetables enjoy multiple benefits: not only is the food fresher and tastier, and conveniently located just a few steps from the kitchen, but gardeners can enjoy unusual varieties that are not widely available. What’s more, gardeners have the fun of watching the entire growing process and the satisfaction of knowing that they had a role in it.

None of this qualifies as news, of course. All vegetable gardeners know it is infinitely more satisfying to make a delicious meal using produce they grew themselves. In earlier times in our history, people had little choice in the matter. Our great-grandparents might smile if they could hear us make such a fuss over beans or lettuce from our garden, but we know that as delicious as they are, homegrown vegetables are a rare treat today, repaying us many times over for our small effort.

In this section we present an array of vegetables that are appropriate for container gardens, including some tried-and-true varieties and some that may be new to you.

One thing you should keep firmly in mind is that across the board your final yield from a container garden will be smaller than what you would get from a comparable number of plants in a traditional, in-the-ground garden. On the other hand, you do get vine-ripened tomatoes and gourmet salad greens and luscious edible flowers and all the chives any normal person could possibly use. And that’s good enough.

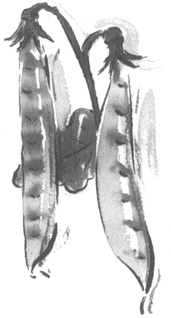

If the only fresh beans you’ve ever eaten came from the supermarket, you are in for a treat. Growing them yourself has it all over store-bought, and not just because of freshness. For one thing, you won’t have to be limited to the standard green variety. For another, the plants are handsome and can be used (the pole types, that is) as a living curtain outside a window or as a windbreak for a windy balcony.

Yet another bonus is that the beans themselves are preceded by pretty little flowers, which are also edible and make a charming garnish, especially the lilac blossoms of purple-podded types and the bright red flowers of scarlet runner beans. And beans are among the easiest vegetables to grow. All in all, they are a very satisfying choice for your patio garden.

Bean Basics. All beans belong in one of two big categories: pole and bush; there are several types within each category, and many varieties of each type. Pole beans are long vines, 8 feet tall or more, and need vertical support. Bush beans are short, stocky plants that do not need support. Both types are very appropriate for container growing, but you do have to know which type you have, so pay attention to the mail-order catalog description and the information on the seed packet. If you plant pole beans without some kind of trellis to grow on, pretty soon you’ll have a big mess. All other things being equal, bush types produce beans earlier than pole beans, but pole types continue to produce over a longer period of time.

Planting. You will almost never find baby bean plants for sale, so you have no choice but to grow beans from seed. The seeds are large and easy to handle, germinate readily, and grow quickly. Some pointers to keep in mind:

1. Plant seeds directly in the container, but wait until the weather is really warm (with nighttime temperatures of 60°F).

2. For pole beans, put a cluster of three or four seeds in front of each vertical member of your trellis. (In many books, this cluster is called a “hill,” a term that has nothing whatsoever to do with height.) For bush beans, space individual seeds 4 inches apart. In both cases, plant the seeds approximately 1 inch deep and cover lightly with potting soil or moist peat moss.

3. All beans (peas, too) will benefit from a preplanting treatment with an inoculant. Functioning like a booster shot, it enhances the plant’s natural ability to convert nitrogen from the air into nitrogen in the soil, which is important because nitrogen is one of the three primary nutrients that plants need for vigorous growth.

The long and the short of it is, beans that are inoculated grow stronger and produce more beans. Inoculant comes in the form of a powder, which you dredge the seeds in before planting. It also comes in the form of granules, which you sprinkle directly into the soil along with the seeds.

Success with Beans. Beans are quite easy to grow. Not many diseases haunt them, and insect pests are minimal. (An exception is the fava bean, which aphids love.)

Your biggest concern should be watering. Beans do best with a steady, even amount of moisture. If your summers are hot and dry, check the soil every day. Never let it go completely dry, or the plants will simply shut down. Once the first tiny beans form, begin a regular program of fertilizing.

Harvesting. First the pretty little flowers wither and dry, then overnight, or so it seems, there’s a miniature bean where the flower used to be. The first time you notice it, it’s maybe an inch long and about as big around as a baby’s shoelace. The next thing you know, it’s a full-size bean, and pretty soon they’re coming on faster than you can count.

It’s very important to keep the beans harvested. Left too long on the vine, not only do the pods become tough but the plants stop producing.

Use two hands for harvesting. Grasp the stem with one hand and gently pull the beans away with your other hand, using an upward motion. Don’t yank; bush beans, which are shallow-rooted, may come up out of the dirt, and pole vines may be ripped off the trellis.

Over the full growing season, you can expect to harvest approximately 1 gallon of beans (the full pods) from each plant of the bush type, and 1 to 2 gallons from each pole plant, including favas. For those beans that you shell (and discard the pods), the actual yield will obviously be less.

Varieties. One of the hardest things about beans is also the most fun—becoming acquainted with all the wonderful types and varieties. If you had a large farm garden, you could grow some of everything, but with container gardens you are forced to choose. It’s important, therefore, to pay attention to key words in the catalog description, and to make your choices based on what is most important to you: taste, color, growing period, and so forth.

Here are the basic types, and suggested varieties of each:

• Snap beans. Also known as string beans, these are your basic green bean.

For pole beans, we like:

Blue Lake (60 days). Stringless, tender pods with excellent flavor; long yielding.

Kentucky Blue (65 days). All-America Selection. Long, straight pods combine flavor from two classic varieties: Kentucky Wonder and Blue Lake. Vigorous and productive. Needs a hefty trellis.

Cascade Giant (60 days). Long, tender pods are light green streaked with scarlet and purple, and have a unique meaty flavor. Produces an early harvest at base of plant, with later crop on vines.

For bush beans, we like:

Blue Lagoon (60 days). Fine flavor, very productive, and a concentrated harvest from compact plants.

Bush Blue Lake (60 days). Same classic flavor as the pole type.

Tendercrop (54 days). Vigorous, good flavor, and very popular.

• Purple-podded beans. A variation on regular green snap beans, these are green on the inside, but the exterior of the pod is an amazing rich purple that turns green when cooked. The flowers are lovely, in shades of lilac and lavender. Again, both bush and pole types are available:

Purple Queen (bush, 52 days). Beans are flavorful and a uniform deep purple. Leaves and flowers also have strong purple coloring.

Purple Peacock (pole, 60 days). Vigorous, productive vines make an attractive summer screen.

• Italian beans. Compared to standard snap beans, Italian pods are wider and flatter, almost as if pressed in a book. You can eat them as young snap beans or let them get larger and shell them. Romano (70 days) is a good pole type; Varoma (58 days) is one of several flavorful bush varieties.

• Wax beans. In a three-bean salad, these are the yellow ones.

Two good bush varieties are:

Roc d’Or (54 days). Productive, superior flavor, and tolerant of cool, wet growing conditions.

Gold Crop (56 days). Stringless, tender, with good flavor; sets pods well in hot weather.

• Scarlet runner beans. A longtime favorite for the brilliant red flowers, but also valuable for the beans themselves, which can be either eaten fresh or left on the vine to dry. The term “runner” implies a vine, and most scarlet runner beans do grow as vines, but these are not the same as pole snap beans; they are their own species. Runner beans can be started sooner than regular snap beans, and thrive where summers are on the coolish side, like New England or the Pacific Northwest. The cheerful flowers look splendid in a salad or garnishing a bowl of steamed spinach.

These beans are lusty growers, with large, lush, dark green leaves; the vines will quickly cover a trellis or wall, giving you shade or a screen in addition to perky flowers and tasty beans.

For pole types, good varieties include:

Scarlet Emperor (70 days). Fully mature pods are 10 to 12 inches long, but for best table quality and a steady production of red flower sprays, pick beans before seeds begin to swell, when they are about 7 to 8 inches in length.

Painted Lady (90 days). The beautiful flowers have a scarlet hood and white base.

The terminology is confusing, but there are also bush runner beans that don’t form runners. A nice one is Dwarf Bees (80 days). This dwarf variety, only 18 to 24 inches tall, needs no staking. Like all the runner types, it produces brilliant flowers and tasty beans. Seeds may be somewhat hard to find.

• Filet beans. Tiny, delicate beans also known by their French name, haricots verts. Filet is a particular type of bean, not, as some people think, an immature snap bean. We recommend the variety called Straight ’n Narrow (53 days), a compact bush type.

• Dried beans. Kidney beans, black beans, black-eyed peas, garbanzos—all the ones we normally buy as dried beans—can also be grown at home. With the limited space you have for gardening, however, you might decide it’s easier to buy dried beans at the supermarket.

• Lima beans. The southerners’ favorite, for good reason: limas need a long growing season. If your growing season is short but you love the taste, try a bush type, which matures faster.

Two good ones are:

Thorogreen (68 days). Vigorous 18-inch plants bear till frost.

Fordhook 242 (85 days). High yielding, heat tolerant, and easy to shell.

• Fava beans. The sweetly fragrant flowers of fava beans make them a welcome addition to the culinary container garden. The individual beans are very large (their other name, broad bean, is quite apt) and have a dense, meaty texture. Rich in protein, fresh and dried favas have long been a favorite of European families, and in recent years the fresh beans have become popular with gourmet cooks here. If you want to try them fresh, growing your own is your best bet. Unlike limas and even snap beans, favas prefer cool, damp weather; plant them in spring, about the same time as peas. The plants grow to about 3 feet tall, so a short trellis is a good idea.

Aphids can be a problem in the spring. One easy control is to just pinch off the growing tips where they tend to cluster. This has the advantage of forcing plants to put energy into maturing the crop of newly set beans. Harvesting occurs at several stages: pick the first pods when no more than 4 inches in length and beans are slim and flexible. Cook like snap beans, either whole or sliced. When the pods gain size and begin to droop, they are ready for eating as fresh shell beans. Steam for three to five minutes, then serve hot with butter or cooled for salads. If the seed coat on the bean has matured, slip it off before serving. At season’s end, allow the beans to dry and store for soups.

A few people of Mediterranean heritage have a rare genetic allergy to favas. If you have never eaten them, start with a very small portion to see if they agree with you.

Good varieties are:

Broad Windsor (75 days). Large beans, four to five per pod, with good flavor.

Aquadulce (85 days). Hardy; in mild-winter climates, plant in fall for a spring crop.

Theme Garden

A Kid’s Garden

Talk to any longtime gardener, and you’ll find a common theme: almost all of them started gardening as a child. They speak with great fondness of summer days in the garden, working alongside their parents, their grandfather, a favorite aunt; they smile at the memory of pulling up their very first radish, eating sun-warmed tomatoes right there in the garden patch, surviving their first encounter with a ferocious-looking hornworm.

Of course, childhood experience isn’t a prerequisite; many people first discover the pleasure of gardening as adults. But the reverse is universally true: anyone who learns about gardening as a child is hooked for life, even if circumstances sometimes intervene. By introducing children to gardens, you’re equipping them for a lifetime of enjoyment. And even without that lofty parental goal, helping children start their garden is its own reward because they have so much fun and you have the even greater pleasure of watching their enjoyment.

Children are naturally attracted to small things of all species; just think how they go silly over new puppies or fuzzball kittens. They exhibit that same sense of delight when a seed they planted with their own hands breaks through the soil and pokes its head up to say hello.

Containers provide the perfect way to start children gardening because the very chores that make them lose interest in larger gardens are practically nonexistent in containers. For maximum success:

1. Let the kids make the decisions about what to plant, based on what they like to eat, but point them toward varieties that grow fast.

2. Set them up with their own container and gear; as much as possible, let them do the work.

3. Be flexible, and don’t expect picture-perfect results.

We suggest two gardens here: one for toddlers and one for older children.

A GARDEN FOR TODDLERS

Everything in this garden is easy to grow and produces the good stuff at a young child’s eye level.

Easter Egg radishes are a blend of several varieties in one seed packet, producing radishes in different colors: white, red, pink, and lilac. Harvesting them is always a surprise; you never know what colors you’ll get.

Thumbelina carrots are small and round, rather than long and skinny. Even children who don’t usually like carrots like these because of the fun shape.

Pansies are especially attractive to small children if they can see a cat’s face in the flower. This mimicry is most obvious with bicolor or tricolor flowers, in small or medium sizes. Very large flowers in solid colors are quite pretty, but they don’t look like kittens.

Wee-B-Little pumpkins are perfect jack-o’-lantern miniatures, about 3 to 4 inches across. The plant grows as a semi-bush, and will basically fill the container by mid summer. If several children claim this garden, you might want to let them create “autographed” pumpkins. When the fruits are about the size of a baseball, have each child write his or her name on a pumpkin with a felt marker. Then you go over the writing with a nail or the tip of a sharp knife, cutting lightly down through the skin. The cuts will scar over, and each mature pumpkin will be personalized.

Start with a container at least 18 inches wide. In early spring (as soon as pansies show up at the garden center), set out pansies and sow seeds of radishes and carrots. It’s okay if the seeds get mixed together; in fact, many people deliberately plant radishes, which germinate very quickly, in with other, slower seeds to keep the soil surface loose. The radishes are ready to eat in less than a month; as they come out, space is opened up for the carrots. The pansies will still be looking cute through early summer.

In early June plant a few pumpkin seeds in the center of the container. Or, if your growing season is short, start seeds indoors in early May and transplant into the container in June. In either case, by mid summer the plant will stretch across the entire container, which is okay because everything else has been harvested. The pumpkins start forming in August, and are ready for decorating the table (or eating) by Halloween.

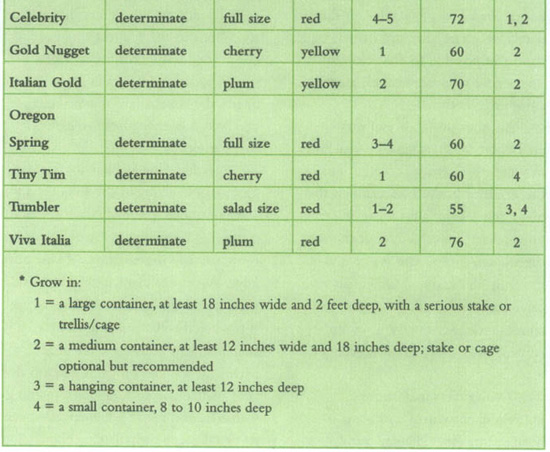

As an alternative, if your kids have an old toy dump truck or something similar that they no longer use, plant a few pansies in the truck’s bed and set the truck right on top of the container. As the pumpkin vine grows and threatens to overtake the whole container, move the truck down to the floor and keep it watered; in the fall, when the temperatures turn cool, the pansies will put on another burst of flowers.

To add a playful element that will keep children entertained and also keep birds away, search out a colorful whirlygig. Older wooden ones in antique stores are very endearing, and very dear. New ones can be charming, and even the inexpensive plastic versions captivate young children with their movement and bright colors.

A GARDEN FOR OLDER CHILDREN

Children who enjoy eating sunflower seeds as a snack get a big kick out of growing the flowers and seeing the seeds form in autumn. And if your mental image of a sunflower is something 10 feet tall, you’ll be glad to know about dwarf varieties. Three good ones are Teddy Bear, Sunspot, and Big Smile dwarf sunflowers. They seldom top 2 feet—just the right height for a child, and for a container.

Purple-podded beans are remarkable for their color; the outer skin of the pod is a dark purple that turns green when cooked. The taste is the same as regular green beans’, which means the children either will or will not like to eat them, but kids are guaranteed to enjoy the magic show when the beans turn color. They are available in pole and bush forms, but choose a bush type for this garden.

Jack-Be-Little pumpkins are perfect pumpkins in miniature, 3 inches across and 2 inches high. Their tiny size is especially appealing to very young children, but we’ve chosen this variety for older children because the pumpkins form on a vine and thus need to be on a trellis, too high for toddlers to watch them growing.

This garden works well in a medium to large container, 14 to 18 inches in diameter. Position a strong trellis at the rear for the pumpkin vine to climb.

Easter Egg radishes, described above, can be planted and harvested several times from March through May. In late May, plant bean and sunflower seeds in among the last of the radishes, and pumpkin seeds just in front of the trellis legs.

In almost every respect, beets are a perfect choice for the container garden: they’re easy to grow and fast to mature, they don’t take up much room, they can be resown for several harvests per year, they don’t need a lot of maintenance, they taste significantly better than canned, and you can eat the entire plant.

The only drawback seems to be that for whatever reason, people don’t think of growing them. But even if beets are not high on your list of favorites, we urge you to include them in one of your containers for all the reasons above, and two more: you’ll get to enjoy the tops, which are wonderfully rich, smooth-tasting greens, and you can grow delightful varieties you’ll never find in a supermarket.

Beet Basics. From one plant you get two crops: the round red root that you envision when someone says “beet,” and the leaves that grow above ground. The most reliable way to find beet greens is to grow them, for even fresh beets in the supermarket often have the tops chopped off. Very young, tender leaves are wonderful raw in a salad, and older leaves can be cooked like spinach; even people who don’t usually like cooked greens often enjoy beet leaves, with their soft, mellow flavor.

Planting. Beets are a cool-season vegetable, which means you can start them early in spring and resow several times, up till early summer, and then again in late summer for a fall/winter crop. In very general terms, that means mid March to early June for the first sowings, then again during the first three weeks of August for the second crop. You can even start seeds indoors ahead of time, should you get garden-restless in February. Germination takes one to two weeks.

To speed germination, soak seeds overnight, then plant directly in the potting soil ½ inch deep and 1 inch apart. The hard, bumpy seeds are actually clusters of several seeds, so you’ll get several seedlings sprouting from each one. When the seedlings are about 2 inches tall, thin away all but one in each cluster. (Rinse the thinnings and add them, whole, to any mixture of sautéed greens.)

Success with Beets. The secret of tender, tasty beets is to keep them growing fast, and that means consistent watering and fertilizing. Add a balanced fertilizer once a week, and keep a close eye on soil moisture. If the soil dries out, or if there is an alternating pattern of too dry, then too wet, the beets will become tough and woody.

Harvesting. Start harvesting the roots when they are about an inch in diameter; to get an estimate of size, brush away the soil from the shoulders of one plant. Beets have a very cooperative nature: they are ready to eat when very small, but they also keep growing without loss of quality. If you make a second sowing in August, you may well be harvesting fresh beets right through the winter.

To cook beets (the roots, that is) without their bleeding, leave about an inch of stem in place and add a tablespoon of vinegar to the cooking water, When the beets are done, slip off the peel and the stem ends. For full, deep flavor, try baking beets in the oven.

Varieties. The classic beet is round and red, but that’s only the beginning of the story. The fun part of growing beets is having access to unusual types: beets that are long and thin like carrots, or golden yellow, or pink-swirled inside like candy.

Scarlet Supreme (50 days). Outstanding on almost every front: it matures earlier than others, produces lots of bright green tops, and is sweet and tender.

Golden Beet (55 days). Another heirloom type, with a sweet-tasting root that is a lovely golden yellow and dark green leaves with yellow ribs. Popular with gourmet cooks because the color doesn’t bleed. Plant more thickly than other varieties, to compensate for lower germination rate.

Detroit Dark Red (55 to 60 days). This standard, classic red beet is an heirloom variety, and the most popular for home gardens.

Chioggia (55 days). This heirloom variety produces roots with a pretty pattern of concentric circles of red or pink, alternating with circles of white or cream color. Grated raw into salads, they add a zap of color and texture; the flavor is unusually sweet.

• Cylindrical beets. These are a perfect example of the joy of growing your own food: you can have an unusual treat with no more effort than is involved in growing the ordinary kind. Rather than the familiar round globes, cylindrical beets are long and slender, like a carrot if carrots were beet red. Because of this narrow shape, they need less growing room; in the same amount of container space, you can get up to four times the yield. Another nice feature is that the mature beets can be sliced crosswise into rounds of uniform size for a very attractive salad presentation.

The downside is that they are a bit slower to mature; you might think about growing some of both types for a long, delicious harvest.

Two very nice cylindrical varieties are Formanova and Forona, both 60 days. If you plan to try these, use a slightly deeper soil depth than for round beets: 8 inches minimum.

Fresh, sweet tidbits with a true carrot taste, frilly foliage that is pretty in its own right, and delightful varieties that have never seen the inside of a supermarket—are those enough reasons for growing your own carrots? If not, think of them as a way to introduce children to gardens, with a vegetable they probably already like in shapes they never saw before. Adults who think a carrot is carrot is a carrot will change their minds when they first taste one that is truly fresh.

Carrot Basics. It’s a bit of a challenge to sort out all the choices among carrots because of the way they are named. Seed catalogs describe individual varieties as being, for instance, “a Chantenay type” or “early Nantes.” Chantenay and Nantes are names of older varieties that have now become generic terms for different types of carrots; the distinguishing trait is their shape. Long and thin Imperator is the one you usually find in the supermarket. Chantenays are tapered, with a broad top and pointed tip, and can grow to very large size. Danvers are also tapered, a bit smaller. Nantes types have straight, untapered sides and blunt ends. Two other generic types, with more logical names, are round and finger carrots, and they are what you would think: round like golf balls, and finger-shaped. Rounds, fingers, and Nantes are best for containers.

Planting. Carrots germinate best when the soil is 70° to 80°F, but they can be started much sooner, as long as temperatures don’t sink below 45°F. The seeds are quite tiny, and in cooler weather they take a long time to germinate; in the meantime, it’s essential that they be kept moist. Carrots don’t transplant well, and so must be sown in place. All this adds up to something of a challenge when it comes to getting them started. Here are some tips:

1. Make a mixture of carrot seeds and radish seeds, and plant the mixture; the radishes germinate rapidly, keeping the potting soil loose for the teeny carrot seedlings and serving as place markers. Check the soil every day; add water if needed. Use a gentle mist so you don’t dislodge the seeds. Keep the moisture level up even after the radishes begin to grow; the carrot seeds still need it, and it will keep the radishes tender and crisp.

2. Alternative for different taste buds: mix one part carrot seeds with three parts bok choy seeds. In 30 to 45 days, depending on the variety, you’ll be harvesting the bok choy and the carrots will be just developing; as the bok choy comes out, it opens up room for the growing carrots.

3. If you’d rather not mix things, sow the carrot seeds alone (about ¼ inch deep) and take extra measures to keep them damp. Cover the seeds with wet burlap, a thin layer of sphagnum moss or peat moss that you presoaked, or even something like damp paper towels if that’s all you have. Keep the covering layer damp, and keep checking underneath; at the first sight of feathery green seedlings, remove the covering.

Either mixed or plain, you can continue sowing carrot seeds in batches for an extended harvest season. It doesn’t have to be a precise system: when you’ve pulled up about half your carrots, plant some more.

Because the seeds are so small, you cannot help but plant them very thickly, which means that you’ll need to do some serious thinning once the tops are about 2 inches high. For long, slender types, thin seedlings to ½ inch apart; the round ones need more room, about a 1-inch spacing.

Rose Marie says: With these root crops you don’t have to be too precise about the thinning. Just keep getting in there and picking out the largest ones, which creates room for their smaller brothers to grow. The first tiny thinnings can be added whole to salads—the tender young foliage is good to eat. Just rinse, and pinch off the threadlike root at the growing tip.

Success with Carrots. Once you get past the germination challenge, carrots are extremely easy to grow. Keep them watered and fertilized with a balanced fertilizer, and you can turn your attention elsewhere.

Harvesting. You can start harvesting anytime the carrots reach the size you want. There is no particular trick to it; just be sure you have a firm grip on the stems, near the shoulder of the carrot root.

If you sow in the summer for a winter crop and carrots are still growing when the weather turns cool, you can leave them in place and have the fun of pulling fresh carrots at Thanksgiving. Cover the soil with protective mulch in very cold areas; sphagnum moss, this time in a thick layer, will work fine.

Varieties. Two round ones we like for containers are Thumbelina (60 days), an AAS winner, and Parmex (70 days). Both are sweet, bite-sized treats that make children smile.

Scarlet Nantes (70 days). A - Nantes carrot, approximately 6 inches long. Touchon (75 days) is an heirloom Nantes type that is nearly coreless and very juicy.

Little Finger (65 days) is a Nantes type in shape but smaller overall, like your little finger. Minicor (55 days) is very similar.

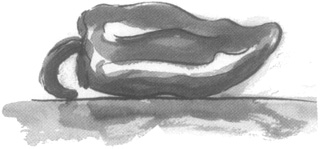

Cucumbers that are allowed to grow on the vine until they are just-right ripe have a rich, full, cucumbery taste that is as different from supermarket cucumbers as a fresh pineapple is from a picture of a pineapple. If you love cucumbers, you’ll want to grow your own, for that wonderful flavor and for the unusual varieties available (lemon cucumber is pictured above). Just remember: they do take up room—more than, say, carrots—so be prepared.

Cucumber Basics. In the minds of people who sell us the seeds, cucumbers are grouped into two large categories, based on how they are used: picklers and slicers. Picklers are short, stubby, and bumpy. Slicers are the familiar long green vegetables that we slice raw for salads and crudités. Many catalogs group into another category the types known as “burp-less,” specially bred to eliminate the enzymes that make digestion difficult for some people (burpless is also the name of a specific variety, as well as the name of a subcategory). And some catalogs create a separate category for Asian cucumbers, which are unusually long and thin, mild, and crunchy.

Deep in their genes cucumbers are vines, but plant breeders, constantly searching for new items to offer customers, have developed several types that maintain a compact bush shape. The vine types need to be grown on trellises, the bush types do not; be sure you know which you are getting. In catalog descriptions and on seed packets, bush types will be indicated as such; the vining types may not say anything in this regard.

Planting. Cucumber plants are heat lovers; they simply won’t germinate until the temperature hits 70°F. For direct sowing, wait until the weather, and thus the soil in your container, is really warm. Plant six to eight seeds in a cluster, about ½ inch deep; when they have two sets of true leaves, thin to the strongest two or three seedlings. Pinch the others off at the soil line to avoid damaging the roots of the keepers. Be ruthless about doing this; it really is important.

Cucumbers grow so fast once they get started, it usually doesn’t help much to start them indoors. However, if you find small transplants at the garden center, you can plant them in your containers a bit early with some nighttime protection; see page 55 for ideas.

Success with Cucumbers. Consistent water and lots of fertilizer—that’s the secret to success. You are going to be surprised at how fast cucumber vines grow when the weather is to their liking. To support that growth, especially once they start setting fruit, give the plants a balanced fertilizer once a week and make sure the potting mix never dries out—that’s what produces cucumbers that are bitter, hollow, or otherwise unpleasant.

To help hold moisture in the soil, cover the surface with a light mulch of peat moss or florist’s decorative moss. This has the extra benefit of keeping any surface roots from drying out.

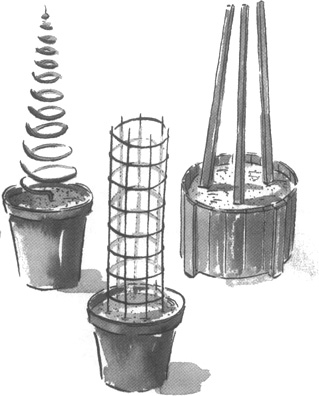

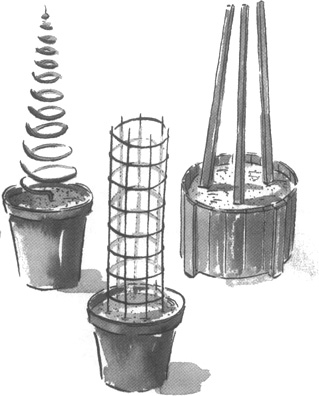

Cukes do extremely well trained to a trellis (see Chapter 4 for ideas). In a 20-inch container with a 4-foot demicage, you could plant up to six cucumber vines. Not only do you get maximum use of your space, but long, thin varieties like Suyo Long or Sweet Success grow into an attractive straight shape, instead of being twisted and curled.

Cucumbers are susceptible to a large array of plant diseases, most of them caused by pathogens that live in garden soil. As you study seed catalogs you’ll see that breeders have been hard at work developing disease-resistant varieties. In containers you’ll miss most of those problems, but you could very well encounter powdery mildew late in the season; see page 76 for treatment.

Harvesting. With cucumbers we get an easy lesson in one of Mother Nature’s fundamental principles: the goal of a plant is to reproduce itself. Annuals, which have only one season in which to do so, have an innate drive to produce seeds. One cucumber is a veritable seed factory; all you have to do is slice one vertically to realize how many seeds are inside. If we leave that one fruit on the vine, all the seeds will reach viable size, and the plant, having done its job, will stop producing cucumbers. But if we interrupt that cycle and pick the fruit before the seeds inside are mature, the plant will desperately make more cukes.

The moral of the story: pick cucumbers while they are small and tender, or the vines will shut down. Be vigilant; in the height of summer, the fruits grow astonishingly fast. If one gets away from you (you’ll know it’s overmature if you see yellow skin), remove and discard it.

Most cucumber plants produce both male and female flowers; the male flowers, which sit at the end of a short stalk, appear first, several days before the first female. Don’t be surprised when the first flowers fall off without showing any signs of producing fruits; those are the males. Female flowers have a small bulge behind the flower, where it connects to the stem.

Varieties. The whole point of growing pickling cucumbers is to make pickles, but it’s necessary to grow a lot of cucumbers to make that project worthwhile—more than you can reasonably grow in a container. We’re going to assume you’re more interested in growing the slicing type, and there are many fine varieties to choose from.

Lemon (60 days). Almost everyone laughs with delight the first time they see a lemon cucumber, so different is it from the classic, long green item. Very reminiscent of lemons in size, shape, and color, they nonetheless taste like cucumbers, with a mild, almost sweet flavor. This is a very old heirloom variety, first introduced more than 100 years ago. Harvest lemon cukes while they’re small and show just a trace of yellow at the blossom end. They need a trellis.

Suyo (62 days). These wonderful Japanese-style cucumbers are just as easy to grow as the ordinary kind, and the results are extraordinary: the long, slender fruits are crisp, not very seedy, and quite delicious—a real conversation piece. They need a strong trellis.

Salad Bush (57 days) is an All-America Selection with good disease resistance and the perfect shape for containers: short, very productive vines. Cucumbers are about 8 inches long, with smooth, dark green skins. Fanfare (63 days), another All-America winner with a compact growth habit, is very appropriate for containers. Good yield of slender, extra-crisp fruits.

Sweet Success (50 days) is an example of a fascinating development in plant breeding: gynoecious cucumbers, with self-pollinating, all-female flowers. The fruits are seedless (or virtually so; you may see the faint outlines of undeveloped seeds inside). If they are grown side by side with regular cucumbers, some cross-pollination occurs and seeds will form in these “seedless” fruits. But if you harvest them early, while they are young and tender, the seeds will not have developed to a noticeable stage. Sweet Success is an All-America Selection, and produces a steady crop of slender, 10- to 12-inch cucumbers. They need a trellis.

Theme Garden

Country Kitchen in the Round

Gardening is as subject to trends as any other human endeavor. Spend some time in your local library’s periodicals room, browsing recent issues of several gardening magazines, and you’ll soon realize that you’ve seen the same general topics over and over. What makes gardening trends so interesting is the frequency with which the newest “hot topics” turn out to be very old ideas.

Take kitchen gardens, for example. A few years ago, they were the trend du jour in gardening publications; there was even a mild flurry about the elegant French version of a kitchen garden known as the potager. The ultimate kitchen garden is a happy, floriferous mélange of good things to eat, all growing lustily together: vegetables and herbs side by side with flowers and fruit trees. Our great-grandmothers grew their food just this way, and they never thought to call it anything special.

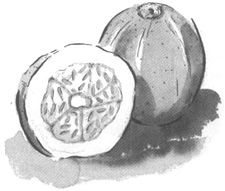

Today most gardeners would love nothing better than to have their great-grandmother’s garden, but many of us simply do not have the space. It is for these admirers of country gardens and country cooking that we designed this particular container garden, which provides a great bounty of good food in a small area. In a circle just 5 feet across, an astonishing variety of edibles can be grown. To put it another way, in a space no bigger than many kitchen tables, you can have an entire kitchen garden bursting with all the good things you like to eat.

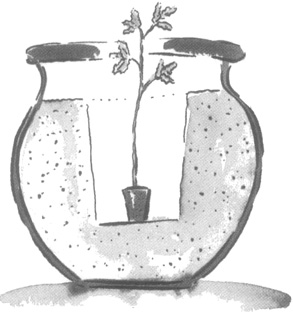

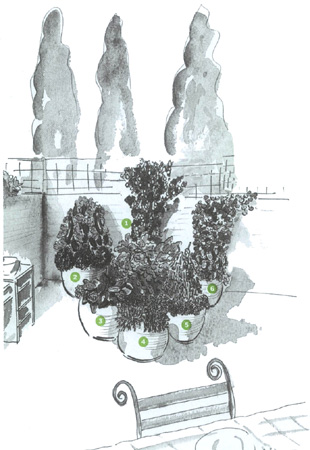

What makes this garden work so well for so many situations is that it is planted in six different containers, so you can arrange them in whatever configuration best fits your garden site. In the drawing here, for instance, the pots are arranged in a semi-circle against the wall, and the tomato uses the fence as a support. You can also move them during the season, as the sun and weather patterns change. This is a very flexible concept, so we’ll give only general suggestions before turning you loose to plant whatever you truly love.

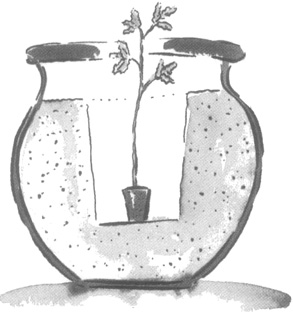

POT 1. In the center, in full sun, a large (24-inch) container. Sturdily staked in the middle of the pot is one luscious tomato. On the edges, plant your favorite cucumber and some trailing nasturtiums. As an option, encircle the entire container with a wire trellis made from concrete reinforcing wire with a 6-inch grid. It should be tall enough to extend another 24 inches or so above the rim. It supports not only the tomato and the cucumber in the large container, but some of the other containers’ plants as well.

In a circle around Pot 1 are five smaller containers, 14 to 18 inches in diameter, with assorted plants. Here are some suggestions.

POT 2. One or two Asian eggplants at the rear, with three or four basils on the outer edge. Place this pot in full sun.

POT 3. One sun-loving summer squash, fronted with lettuce. By the time the summer heat knocks out the lettuce, the squash will be at its prime.

POT 4. Climbing nasturtiums at the rear, peppers near the front; this is another sun lover.

POT 5. Bush peas on the inside, lettuce circling the outer edges. Bush peas don’t absolutely need a trellis, but will appreciate the extra support. Around the first of July, direct-sow seeds of bush beans in among the pea plants; by the time they germinate, the peas will be ready to come out (cut off at ground level and leave the roots in place). This container can go on the shady side of your circle.

POT 6. A small herb garden for fans of Paul Simon: parsley, sage, trailing rosemary, and thyme; sun or part shade.

If you add the wire trellis to the center container, many of the plants in the smaller containers will grab onto it. This is fine if you don’t plan to move anything later on, but if you do, you can accomplish the same results by using individual short trellises in the smaller containers. In particular, pots number 2, 4, and 5 would benefit from a bit of trellis support.

Very few people are ambivalent about eggplant. Either you like it or you don’t, and if you don’t, then you’re not likely to develop a fondness for it just because you grew it with your own hands. But if you do like it, or if you’re ready to try something new, the small Japanese or dwarf varieties are terrific—beautiful while they’re growing, delicious when cooked.

If you’ve never seen eggplants growing, you’re in for a treat. The plants are extremely attractive, with elegant leaves, pretty little flowers, and rich, lustrous fruits that may be regal purple, ivory, lavender, blush pink, or lime green, depending on the variety.

Eggplant Basics. It’s convenient to think of eggplants in two major groups: the familiar fat shape, and the long, slender Asian types. Seed merchants have provided us with many choices, including smaller, miniaturized versions in many luscious colors.

Planting. These are hot-weather plants, and need temperatures of at least 75°F to germinate. Germination takes two to three weeks; add another couple of weeks to reach transplant size, and then another two to three months to start producing the fruits. It’s clear, then, that you won’t have time for direct sowing. If you are lucky enough to have a garden center stocked with unusual vegetable varieties, you can buy your eggplant transplants in May and June. But if you don’t, your only choice is to start seeds indoors ahead of time.

Backtrack eight weeks from the time when daytime high temperatures usually reach 80°F in your area. Plant seeds ¼ inch deep in peat pots or pellets; keep the tray very warm (see pages 57 to 58). Depending on your climate, you may have to move the seedlings into larger, intermediate pots before the soil outside is warm enough to receive them. Be sure to harden off the seedlings (see page 60) before planting outside.

To give the babies the best chance, keep containers in full sun and cover with black plastic a few days ahead to really warm up the potting soil. For the first couple of weeks, when nighttime temperatures are not reliable, you may need to provide some protection for the tender plants. Blanket them with plastic sheeting, held up off the plants with short stakes; or cover them with milk-jug cloches (see page 47) at night.

Success with Eggplants. Your biggest problem will be timing—getting transplants into the container when the weather is ready. Otherwise, eggplants are generally hardy plants that present few troubles for the container gardener. Occasional problems include aphids, flea beetles, or Colorado potato beetles (eggplants are in the same family as potatoes), but all are manageable (see Chapter 6). Raising the containers up off the floor seems to help deter flea beetles.

Put the container in your sunniest location, keep the soil moist, and fertilize every two weeks. If the roots are warm, you’ll have a little eggplant factory at work.

Harvesting. Eggplants that are overmature are not very appealing; if anything, you may want to pick them a bit ahead of time. The outside skin should still be glossy and smooth. Cut off each eggplant with clippers or a sharp knife, taking a bit of the stem. To keep the plant producing, it’s important to keep up with harvesting. If even one fruit sets seed, the plant will slow down significantly.

Varieties. Traditional varieties, the ones that produce the familiar big, round, dark purple eggplants, don’t work very well in containers: the eggplants they produce are simply too large and too heavy. Fortunately, we have other varieties to explore.

Two general categories of eggplant are excellent for containers: the Asian types, which are by nature long and slender, and the dwarf varieties, which are the traditional oval shape but much smaller.

• Asian type. Ichiban (61 days) has long, slender, dark purple fruits—the classic Japanese eggplant. Asian Bride (70 days) has a similar shape as Ichiban but a different color: a delicate white with beautiful lavender streaks. Green Goddess (63 days) is an extremely productive type with fruits that are 8 inches long, 2 inches in diameter, and a knockout color: lime green. Neon (65 days) is a modified Asian type, with medium-long fruits slightly swollen near the end. It is well named: the outer skin is a rich, intense, deep pink that glows like neon against the bright green leaves.

• Dwarf varieties. Bambino (75 days) produces lots of small round fruits, 1 to 1½ inches in diameter, deep purple in color. It is particularly good for containers because the plant itself is smaller than most. Little Fingers (65 days) has dark glossy purple fruits, short and slender, 3 to 4 inches long.

Rosa Bianca (75 days) has roundish fruits, rather like a softball that got squashed at one end, and mild flavored, but the real delight is their gorgeous color: soft lavender streaked with white is an heirloom variety from Italy.

Comprido Verde Claro (72 days) has small and slender fruits, 3 to 4 inches long, and notable for their amazing color: leaf green at first, gradually turning orange.

The virtues of greens are many: they are easy to grow, thrive in almost any kind of weather, excel in containers, produce a crop quickly, and provide more vitamins per square inch than anything in the garden. But like many things that are good for us, they are often overlooked by gardeners as being not particularly glamorous. That’s a shame, because many of these plants are beautiful to look at and contribute delicious, unusual flavors to the dinner table. Southern European gardeners have built their cuisines on these easy-to-grow, nutritious powerhouses, and American cooks are now beginning to wise up.

Note that in this section we’ve included the green leafy vegetables that are usually eaten cooked (except for spinach, which has its own section). The specialty greens that usually go raw into salads are found in the Lettuce section. We admit that the distinction is subtle and a bit arbitrary, and some items could as well go in one section as the other. If you don’t find something you expect to see here, check under Lettuce or Spinach.

Rose Marie says: My Greek grandmother loved going out to her field to harvest mustard greens, fresh and tender with a little bite. She prepared an endless variety of cooked salads: single or mixed greens, coarsely chopped and sautéed briefly in olive oil, then served with wedges of fresh lemon. Delicious hot, cold, or warm.

Greens Basics. Speaking in general terms, which we have to do in this consolidated section, greens are cool-season vegetables that are grown for their leaves. One very cooperative trait is their long period of productivity: they germinate just fine in cool weather, keep producing during the summer, when lettuce and spinach wimp out, and go on through fall without blinking. Even a light frost doesn’t bother them—in fact, many people think frost improves the taste—so they can continue into the winter and even winter over in temperate areas.

Planting. As soon as nighttime temperatures are no longer cold enough to freeze your container soil, you can direct-sow seeds for these greens. The seeds are generally quite small, and thus should be planted only about ¼ inch deep. Because small seeds are difficult to space evenly, you’re bound to get lots of baby seedlings that will need thinning; if you like, you can replant the thinnings into another container. As a group, greens transplant very successfully, so you can start seeds indoors three to four weeks before your spring frost date to get a jump on your first planting.

Because greens do transplant easily, you’re also likely to find some of the better-known types for sale as young transplants at your garden center early in the season. This is a good way to go with these plants: you get the benefit of someone else’s greenhouse work, but you don’t have to worry about the weather being too cool to set out plants, as is sometimes the case with other vegetable transplants being sold at the same time.

Success with Greens. If you want tender, succulent greens, keep the plants growing fast. That means lots of water and steady fertilizing; since it’s the foliage you’re interested in, use fish emulsion or a fertilizer high in nitrogen (the first number). Most greens are relatively trouble free, but you may have to contend with slugs and snails in the spring and aphids in the summer; see Chapter 6 for controls.

Harvesting. All these plants can be harvested when they are still quite young, and you’ll have baby chard or baby bok choy or baby whatever, just like the baby vegetables you’d pay a pretty penny for at the gourmet greengrocer. Otherwise, keep them growing fast for tasty full-size leaves. Take care, however, not to let them get too large. Most of what shows up in the produce aisle is overgrown, giving nongardeners a false impression of what these plants really taste like. If some of the oldest leaves on your plants get too big and tough, just remove and discard them to keep newer growth coming on.

Harvest the outermost leaves, just enough for tonight’s supper, and your plants will keep producing. Pull away the leaves or slice the stalks at the base with a sharp knife. The technique for kale and collards is a bit different: if you slice leaves from the crown (the center of the plant), the plant will form new branches with more new leaves; use a knife for a clean cut.

Varieties. We offer just a few suggestions for each of the plants, even though many of them have many varieties and all are very fine container plants. Spend a few minutes with seed catalogs, and you’ll realize the astonishing range of intriguing possibilities. The reputation of leafy greens as unglamorous country cousins will be banished once and for all. Most plants in this chapter belong to the cabbage family and share significant family traits; once you have experience with one, you can confidently grow its relatives.

• Swiss chard. Botanically, chard is a first cousin to beets, but gastronomically it’s closer to spinach. It sends up tall, upright leaves on thick, succulent stalks; both the leaves and stalks are delicious. The crinkly leaves are larger than spinach and the taste is more robust, what some people describe as earthy. Chard is a vitamin factory that just keeps going from spring till frost, and even through to the next spring in mild-winter areas. But when all is said and done, the main reason we’re attracted to it is its looks: chard plants are some of the most beautiful vegetables you’ll ever see. Don’t be surprised if your visitors mistake them for a rare specimen of some exotic ornamental.

Two long-familiar types are red chard and white chard—a reference to the color of the stems. Fordhook Giant (60 days), the classic white chard, has been grown in America since 1750; Ruby Red (60 days), sometimes sold as Rhubarb Chard, is also an heirloom variety, having debuted in 1857. Several other varieties are offered by seed catalogs, all of them fine, but a real treat is the new type called Bright Lights (55 days), an All-America Selection for 1998. What makes this such a stunning variety is the brilliant colors of the stems: they may be hot pink, orange, red, golden yellow, purple, white, or magenta-and-white striped. Each color is so richly luminous it seems impossible.

Maggie says: One summer, I constantly found my neighbors gathered at the edge of my patio, gazing at the containers of Bright Lights chard and whispering to each other. It was so much fun, I could hardly bear to harvest any of it.

Johnny’s Seeds, which introduced Bright Lights, now has isolated the yellow strain in a new variety named Bright Yellow (60 days).

The color of the stem stays true through light cooking; you can also harvest leaves while they are still young and slice the colorful stems crosswise like celery for a salad surprise.

• Collards. Anyone raised in the South is familiar with “a mess of greens,” which invariably means collard greens. Collards are large plants whose upright blue-green leaves taste somewhat like cabbage. They are very closely related to kale (see below), but because they tolerate heat better, collards are the greens of choice in the South. Like other cabbage family members, collards grow nicely in cool weather, and a summer planting will produce a fall crop that collard lovers swear tastes better when “sweetened” by frost. The classic variety is Georgia (80 days). Vates (80 days) is very similar.

• Kale. You’ve seen kale in the supermarket: the large, dark blue-green, extremely frilly leaves next to the cabbage. You’ve also seen decorative versions in the garden center, perhaps labeled “ornamental cabbage”: very pretty curly rosettes with a blush pink or lavender center. (Yes, you can eat them, although the taste is mediocre; they also make fine garnishes.) But you may not have seen the flat-leaved, nonfrilly types that are such nutrition-packed standouts in the home garden. “Flat” is a relative term in this case—not as flat as, say, the leaf of a maple tree, but side by side with the supermarket kale, curled within an inch of its life, you would definitely see a difference. Kale is delicious cooked like spinach or, in true Italian fashion, sliced into hearty soups.

Among our favorites are two very handsome kales that are heirlooms: Red Russian (50 days) is thought to have been brought to North America across the Bering Strait by Russian traders around 1850. The leaves resemble the foliage of oak trees but are much larger; the plants reach a height of 2 to 3 feet. The basic color of the leaves is a grayish green, but in cold weather, which kale survives very nicely, the stems and veins turn a beautiful lavender color. Lacinato (62 days), an Italian heirloom also known as Black Tuscan, sends up very dark green leaves with a puckered surface and edges that curl under. Overall, the plant grows in a fountain shape, 2 feet tall, and looks stunning as the centerpiece of a container garden.

Dwarf Blue Curled Scotch (55 days) has the deeply frilled leaves that you expect from kale, in the more traditional rounded shape; a real knockout of a plant.

• Mustard. It is all but impossible to draw a sensible line between American mustards and the many Asian greens that are also mustards. Let us begin with Southern Curled (48 days), an heirloom dating from the 1740s, which produces the hearty-flavored leaves traditionally favored in the South. It is particularly attractive paired in a container with Red Giant (45 days), which has a sharper flavor and a scrumptious coloration: dark green leaves overlaid with a translucent purplish red.

Osaka Purple (45 days) is quite similar but smaller overall. Both of these red mustards are heirlooms, and because of their colors make a very nice accent in mesclun salads.

For a gentler taste, we like Tendergreen (45 days); this heirloom variety is sometimes called mustard spinach, and aptly so, for the flavor is somewhere between the two. It is slower to bolt and go to seed than other mustards, another nice feature.

• Asian greens. With the popularity of stir-fry dishes and our unflagging enthusiasm for healthy eating, Americans have fallen in love with Asian foodstuffs. Catering to those interests, many supermarkets now carry a nice variety of Asian greens; however, sometimes you have to buy more than you can use, and then eventually you’ll have a slimy green mess to get rid of. How convenient it would be to have a supply of these wonderful green vegetables right outside your door, always ready, always the right amount.

Bok choy (also spelled pac choi or pak choi—same thing), perhaps the most familiar Asian vegetable after Chinese cabbage, is very easy to grow in containers. The large white stems are sweet and crunchy, the small, dark green leaves are tender and mild-flavored. Among several fine varieties we especially like are Mei Qing Choi (45 days), a dwarf type that stays small, and Joi Choi (45 days), a vigorous producer that does well in both warm and cool weather.

Also try komatsuna (40 days), very leafy with just a hint of tanginess in its taste; Green in Snow mustard (50 days), with tasty leaves and an irresistible name; Chinese kale (50 days), also known as Chinese broccoli and by its Chinese name, gai lohn, which sends up lots of edible flower stalks; tat soi (45 days), with very dark green leaves that grow in a flat rosette shape—very pretty; and mizuna (35 days), a rounded, frilly rosette that is delicious steamed like spinach and also wonderful fresh in salads. It isn’t afraid of cold weather, and also can sail through summer heat if kept well watered.

Maggie says: The first year I grew mizuna, it was love at first sight. The leaves are bright green and very frilly, with slender, juicy white stems. It grows in a soft mound that is especially beautiful when you’re looking down on it. The whole plant is so pretty I would happily grow it just for looks if I didn’t know how great it tastes. And I must have very stupid slugs in my container garden, for they ate the boring old regular lettuce and left the mizuna alone.

If the Garden Fairy challenged you to limit yourself to just one container with edibles, and in it you could plant only one item, you could not go wrong if you chose lettuce. In fact, lettuce may be just about the perfect container vegetable: easy to grow, with a short time to harvest, lovely to look at, and just exactly the type of thing you want to be able to pick fresh for each salad. The one drawback to growing lettuce—that it doesn’t like hot weather—is actually a bit more manageable in containers because you can pick up your garden and move it into the shade.

Lettuce Basics. Looking through some of the catalogs, it’s easy to feel befuddled by the sheer number of lettuce offerings; but when you consider that more than 800 varieties are recognized in the United States alone, the range of catalog varieties is actually rather modest.

Generally speaking, lettuce is grouped into four categories based on shape. Romaine lettuce makes tight heads of long, narrow, crisp leaves. Butterheads form rosettes of very tender leaves with a small, loose head at the center. One early variety was named Bibb, in honor of its developer, and today that has become a generic name for the whole category. Crisphead lettuces have a large, tight ball of a head inside looser outer leaves; Iceberg is one variety. Looseleaf lettuces do not form a head of any kind, just layers of individual leaves in an overall rounded shape.

Each type has its charms, and if you had unlimited space we would encourage you to grow some of everything. But for container gardens we advise you to stick with the looseleafs, primarily for economy of space. Unlike the other three types, which are harvested one entire head at a time, looseleaf lettuces can be harvested one leaf at a time. Thus you can pick just enough for tonight’s salad and leave the plant to keep producing more. Also, most looseleaf lettuces are cut-and-come-again plants: snip off leaves and others grow in their place. But we wouldn’t be making this recommendation if the looseleafs weren’t also outstanding in other important respects: taste and looks.

Planting. Lettuce is most definitely a cool-season plant; it germinates better, and grows better, in cool weather. Even though breeders have worked hard to bring us varieties that handle warm weather better than some others, the improvement is relative, and you should still think of lettuce as a spring and fall crop.

If you can find a good selection of lettuce starts at the garden center, by all means use them; it will make your life considerably easier. However, some of the very best varieties can be obtained only as seeds.

Start seeds indoors about a month before your spring frost date, and move the seedlings outdoors after hardening off (see page 60), when they are 1 to 2 inches tall. Try to do this on a cloudy day, and provide the seedlings with some shade the first few days.

Direct sowing in spring is an easy alternative in mild or temperate parts of the country, for the seeds germinate readily at temperatures as low as 40°F. (In fact, there are reports of seeds germinating on melting ice.) For a steady supply of lettuce, make several sowings two to three weeks apart. As the seedlings grow, gradually thin them until you have about a 6-inch spacing.

If you have some containers with potting soil from last year, and it’s so early in the year that you haven’t planted anything else yet, loosen up the soil surface and sprinkle on a few lettuce seeds; they’ll be up and going while you’re still deciding on your summer plans.

To grow lettuce in the cool days of autumn, you need to sow seeds in late summer—which is a problem because the seeds don’t germinate well in hot weather. To get around this, simply prechill the seeds and the potting soil. You can chill the seeds by refrigerating them for seven days in a zip-top bag mixed with a small amount of moist potting soil. Or if you have some seeds left over from the spring, put the partially used packets into a moisture-proof container and store it in the refrigerator or freezer until late summer. When you’re ready to plant, water the potting mix well (this has the effect of chilling it) in the evening, and plant your seeds in that damp, cool soil.

Success with Lettuce. Lettuce turns bitter when the soil dries out; keep the plants evenly moist, and they’ll grow fast and sweet. Cool, damp environments are perfect for lettuce—and for slugs. Be vigilant, and use the controls suggested in Chapter 6 if you see their trademark: big holes in your leaves and silvery trails on the soil.

One final problem: in hot weather lettuce will bolt. That’s the term for a sudden spurt of growth—where once there was a nice pretty mound of lettuce, there’s a very long stem with just a few leaves, and it seems to have happened overnight. It’s as if you reached deep down inside the plant, grabbed an invisible center knob, and pulled upward. Instead of being tight together, the leaves are spaced out all along the stem. Eventually the plant will flower and make seeds, but in the meantime it is basically worthless, for the leaves now have a very bitter taste. Pull out the plant and make way for the next crop.

Slow-bolting varieties have been developed (some catalogs list them under Summer Lettuces), and they are modestly successful. You can also help by providing some shade for your lettuce plants during hot weather. But the only sure way to prevent bolting is to grow lettuce in the cool “shoulder seasons” of late spring and early fall.

Harvesting. The beauty of loose-leaf lettuces, as we have said, is that you can just take a few leaves without pulling up the entire plant. Work from the outside in; grasp the bottom of a leaf (its stem end) and pull it off with a sideways motion. If you are growing mesclun or salad mixes (see pages 114 to 115), use scissors to snip off as much as you need, in the cut-and-come-again technique (see page 112). And don’t forget that the larger seedlings that you pull up for thinning can be eaten as “baby lettuce.”

Varieties. One of the earliest, most reliable, and tastiest lettuces is also one of our oldest: the heirloom Black-Seeded Simpson (45 days) has been cultivated in America for more than 100 years. It’s a bright, clear green, with pretty ruffly leaves, and tolerates heat better than many others. It is too delicate to survive shipping to market, so only home gardeners can enjoy this tasty lettuce.

Deer Tongue (60 days) is an even older heirloom, dating from the 1740s; the name comes from the shape of the leaves, extended triangles. A very attractive variation is Red Deer Tongue, with red-tipped leaves.

Oak Leaf (40 to 45 days), another heirloom, is also named for its leaf shape. Over the years breeders have developed several variations on the oak leaf theme, so that the word has come to be used generically as well as for a specific variety.

Among these “oak leaf types” are some real beauties. Salad Bowl (50 days), an All-America winner, and Red Salad Bowl (50 days), with green and red leaves respectively, make a nice pairing. Brunia (50 days) is mostly green, with bronze coloration on the tips. They make a handsome trio.

Red Sails (55 days) is extremely beautiful, easy to grow, and slow to bolt: no wonder it was named an All-America Selection. The leaves are bright green at the base, gradually blending to a rich red near the edges; viewed from above, the whole plant seems a striking burgundy red, a color that becomes more vibrant with maturity. A good choice for fall as well as spring.

Lollo Rossa (55 days) is like no other lettuce. The outer edges of each leaf are very heavily frilled, so much so that looking at the plant, you cannot see down into the center. The entire plant is exquisitely decorative, all the more so because of its beautiful coloration: bronze red over bright green. The plants grow into compact, well-rounded mounds that make a handsome border around the rim of a large container. Be prepared for your visitors to go nuts over this one. Two traits you should be aware of: this variety is prone to bolting, and it also responds well to cut-and-come-again treatment; the latter takes care of the former.

For a stunning color palette, combine Lollo Rossa with two new varieties: Lollo Bionda, with soft green leaves, and Impuls, a dramatic cranberry red.

OTHER SALAD GREENS

As American tastes become more sophisticated and interest in healthful eating habits continues to grow, we have seen a great surge of interest in some of the more unusual greens for salad. In fact, in many larger cities it is no longer noteworthy to find once-rare items like arugula and mâche in the neighborhood supermarket.

No longer rare, maybe, but still pricey. Grow these gourmet greens yourself—for thriftiness, for freshness, and for the sheer fun of it.

Most of these salad greens are like lettuce in their growing needs. They do well in cool or moderate temperatures, not so well in very hot weather. Most are cut-and-come-again plants. In all likelihood you’ll have to order seeds, but generally you’re spared the agony of sorting through many varieties because catalogs tend to offer just one or two choices. Start seeds indoors around February, or direct-sow in containers starting in March, or both. Keep them well watered, watch for slugs, create some shade in mid summer, and enjoy.

• Arugula, also known as rocket (42 days). The plant is not among the most gorgeous, but who cares—we’re not after looks but taste. The pleasantly sharp tang is unmistakable and unsubstitutable. If you love that taste, you’ll want to grow your own. It’s quite easy and extremely convenient, since you can simply pluck off leaves as needed. Like most other salad greens, arugula is susceptible to bolting in very hot weather, but all is not lost. The leaves get more pungent after bolting, and the pretty little edible flowers add a touch of spiciness to salads.

New on the American scene is Italian Wild Arugula (55 days), also called Rucola, a hot-weather substitute. It’s actually a separate species from regular garden rocket but has a similar flavor—that robust, piquant taste we associate with arugula—and stands up to summer heat. The leaves, stems, and flowers can all be used in salads, although you can extend the harvest period if you continually cut back the plant to hold off flowering.

• Endive, escarole. These two plants are virtual twins in a genetic sense, although they look very different. Both are bitter-tasting, though not unpleasantly so.

Endive is familiar and easy to recognize: very frilly, almost lacy leaves with long white stems. It is not Belgian endive. Leafy endive is very popular in France, where it is known as chicorée frisée, and Americans have adopted frisée as a synonym for endive (it means “curly” and is the source of our word “frizzy”). The white stems are crisp and succulent, and longer than you would find on, say, a ruffled lettuce leaf.

Commercial growers cover the center of the plant to make more of the stem area white and also to soften the taste, a process called blanching. You can easily do this yourself if you care to: either tie the leaves together at the top or cover the center of the plant with a plate or something similar. Both methods block sunlight from the heart of the plant, thus preventing the photosynthesis that turns plant material green.

A classic endive variety is Green Curled Ruffec (90 days), an heirloom. Très Fine Frisée (60 days) is a real charmer, a 6-inch miniature with mild flavor and extremely lacy leaves.

Escarole is a broad-leaved endive (or endive is a narrow-leaved escarole, depending on your perspective). Broadleaf Batavian (90 days) is an heirloom variety dating from the mid 1860s.

Both escarole and endive belong to the chicory family, and in that group are the plants whose roots are roasted, ground, and added to coffee in New Orleans. Also in the family is the salad green with the bright red heart—radicchio, described below.

• Mâche, also known as corn salad and lamb’s lettuce, is quite popular in Europe and is becoming more familiar here. It has a mild flavor that many describe as nutty, and is so hardy it can be sown in early fall for a winter salad green. This is one of those plants for which we recommend keeping seeds around; whenever you have a vacant patch in a container, tuck in a few.

Blonde Shell-Leaved (50 days) has small, round leaves that are slightly cupped, like shells. Large-Seeded Dutch (50 days), with large leaves, is very productive.

• Purslane. Two different plants, with no other botanical relation aside from their common names, are called purslane.

Winter Purslane (40 days), also known as miner’s lettuce, has a fresh taste and juicy texture. Sow seeds in late summer for fall and winter. It has a distinctive leaf pattern: two small leaves, approximately heart-shaped, are joined in pairs at their base, making a ripply edged funnel that encloses a small white flower. Snip off what you need, and new growth soon follows.

Golden Purslane (50 days) produces fleshy, succulent leaves with a tart, tangy taste and an upright growth pattern; it thrives in hot weather, and is sometimes called summer purslane. Both purslanes have been considered weeds by some misguided souls who don’t know what they’re missing.

• Radicchio. Enormously popular with chefs and creators of “designer” salad mixes, the brilliant red radicchio deserves a place in every garden. It has a toothy texture, a zippy, tart taste, and knock-your-socks-off color. For visual impact, nothing else will do.

Rose Marie says: The slightly bittersweet juiciness of these greens is absolutely addictive.

Traditionally, radicchio has been grown in a two-step process: seeds planted in spring produced a large head of green leaves by summer’s end; that head was sliced off a little above ground level and in a few weeks small heads sprouted around the decapitated stem. In the cool days of autumn, the small new heads developed the strong red color that, for Americans at least, today defines this vegetable.

In recent years, new varieties have been developed that produce a red head without the extra step, although sometimes it is hidden inside an outer covering of green leaves. Some catalog descriptions point out certain varieties that do not require “cutting back,” meaning one-step production.

Milan (78 days) is one of the most reliable varieties of a vegetable that, despite the best efforts of skilled seedsmen, is still not entirely predictable. Firebird (74 days) is described as an excellent variety for those who haven’t grown radicchio before.

Castelfranco (85 days), an heirloom, forms heads without being cut back, as does Chioggia (60 days).

Theme Garden

The Salad Basket

The next time you’re in the supermarket, trying to select the prettiest lettuce from all those displayed before you, think about this: the lettuce was grown in a farmer’s field that may be 100 miles away, if lettuce is in season in your region, or 1,000 miles away if it is not.

Once harvested from the field, it was taken to a packinghouse, where it was cleaned and packed in boxes bearing the packer’s brand name. The packer sold that lettuce to a broker, who also buys lettuce, along with all kinds of other produce, from other packers. The broker used a refrigerated truck to bring the produce to your area. Once it arrived, the broker’s representative sold the lettuce either to a local wholesaler, who then sold it to your market, or to a supermarket chain. The supermarket chain received it at its distribution center, and later moved it into the individual stores.

Where it sat for an unknown period until you came along.

At home, you put the lettuce into your refrigerator. You will use some for tonight’s dinner, but you almost never use it all; the rest will stay until you finish it or it turns to green slime, whichever comes first.

Now consider this alternate scenario: instead of dragging yourself to the market to buy ordinary lettuce that may be as much as five days old and that is almost certain to be more than you need, you step outside onto your patio or balcony or you open the window to your window box. From your container garden of beautiful salad greens, you pick just enough for tonight’s salad. You choose two kinds of lettuce, maybe bright green Simpson and burgundy Red Sails, some arugula, a few leaves of escarole, and a bit of fresh chives. They are fresher than fresh and have not been sprayed with dubious chemicals; they look beautiful and taste fabulous. Tomorrow you can do it all again, with a completely different combination of tastes.

We think salad greens are just about the perfect container edible. They are dead easy to plant (just sprinkle the seeds on the soil in your container), grow quickly, and have a terrific ratio of produce to growing space since you eat the whole plant, not just its fruit. Size is not a determining factor: you could have a tiny salad garden in a window box, a large medley of greens in a wine barrel, or anything in between. You can grow unusual salad greens, including many gourmet types that are not commercially practical and thus can be enjoyed only by home gardeners, just as easily as you can the more prosaic ones.

In your salad garden you can feature any of the delicious things you like to put in your salads. Here we suggest only two combinations, but many other possibilities will come to you as you scan through this book. You might want to include some of the many kinds of lettuce, spinach and spinach alternatives, mustard greens, beet greens, Swiss chard, kale, mâche, escarole, endive, arugula, the wonderful Asian greens, scallions, green garlic, chives, even salad flowers like nasturtiums.

THE CLASSIC SALAD BASKET

This selection fits nicely in a rather small round container or a window box. Plan an arrangement built around the various heights of the plants. In the center, the two tall plants: scallions and chervil. The chervil will get about a foot tall, the scallions a bit shorter. Around these two, set out two different kinds of lettuce chosen for their contrasting shape, color, and texture. One suggestion: Black-Seeded Simpson, a bright green looseleaf lettuce with frilly leaves, and Red Deer Tongue, with smooth, triangular-shaped leaves tipped in red. In a round container, you might want to do one circle of green and one of red, or intermix the two. In a rectangular window box, put the two tall plants in the center and the two lettuces arranged down both sides.

The anise-tasting chervil leaves are a delightful addition to salads. Chervil usually has to be started from seed because nursery plants are rare. Sow the seeds right in the final container, starting as early in spring as you possibly can (as soon as the soil is no longer frozen). You can plant scallion seeds at the same time, although transplants are not hard to find and will get your garden off to a fast start. Lettuce transplants are a common sight in garden centers in the spring, but to be sure of the varieties you have selected, your best bet is to order seeds and start them indoors early (see pages 54 to 60).

The lettuces will be at their peak from mid spring through early summer; once hot weather arrives, they will bolt (shoot up tall and spindly, with bitter leaves) and nothing you can do will stop it. The chervil will last somewhat longer, but eventually it bolts also. The scallions will remain all season, and in fact will multiply for next year as long as you don’t harvest them all. When the lettuce and chervil have passed their peak, pull out the plants and replace them with hot-weather crops (see page 79 for weather-specific lists).

A WINTER SALAD BOWL

Many salad vegetables grow best in cool weather. Often gardeners think in terms of spring—probably because they are so eager to get going after the winter—but they shouldn’t overlook the possibilities of fall gardens. In milder climates, those gardens can extend well into the winter months. With that kind of climate in mind, we suggest the following winter salad garden. This garden works best in a round container, medium size to large, but you could also use a window box as long as it is a fairly good size. Sow seeds or set out transplants in August, and you could be serving fresh salads from your garden as late as Thanksgiving.

Imagine a circle made of four rings, like a bull’s-eye target; you’re going to fill those rings with plants in alternating green and red colors. In the very center, one mizuna plant. This Japanese beauty is delicious as a cooked vegetable or raw as a salad green, and it is exquisitely beautiful. Its bright green leaves are extremely feathery, on long, crisp white stems, and they arch outward from the center in a pretty rosette that gets wider as the plant grows. Harvest the older (that is, outermost) leaves to retain the soft mounded shape.

Arranged in a circle around the mizuna, plant several radicchio plants with their red and white swirls. Search out one of the varieties that do not require cutting back (see pages 114 to 115), so that you can plant these gorgeous red globes at the same time as the rest of your winter garden.

The next circle contains two types of greens, planted alternately: arugula and winter purslane. Their textures and leaf shapes make a nice contrast with each other, and their bright green color is a terrific foil between two rings of red: the radicchio on the inner circle, and the burgundy lettuce on the outside. Arugula, with its strong bite, gives a real punch to a mixed-green salad. Winter purslane, less well known in the United States, has a milder taste, a juicy texture, and unusual, very attractive leaves.