The word ‘Berlin’, a crossed-out heart, a capital ‘U’, and an unmistakable message: when the ‘Berlin does not love you’ stickers first appeared on buildings and street furniture across Germany’s capital in the summer of 2011 (Figure 1.1), there was considerable uproar and media attention. Their emergence did not come out of the blue, however, but reflected a conflict that had been brewing for some time. Boosted by ever-growing visitor numbers and revenues, Berlin’s business elites and politicians celebrated the city’s booming tourism trade throughout the 1990s and early 2000s as a kind of saviour for the economically troubled city, and proactively designed various campaigns to lure even more visitors to Berlin. The reaction of many residents, especially in Berlin’s central residential neighbourhoods, towards the rocketing presence – and prevalence – of tourism in their midst has been, meanwhile, decisively less enthusiastic. Against the backdrop of the city’s profound socio-spatial restructuring after the fall of the Wall in 1989, some residents had already, in the late 1990s, voiced concerns about what they perceived as a touristification of Berlin’s inner city. By the early 2010s concerns about the negative impacts of its success as a tourist destination had become so widespread that even national and international media began to pay attention to the issue (see, inter alia, Hollersen and Kurbjeweit 2011; Duvernoy 2012). Graffiti with slogans like ‘No more rolling suitcases’ and ‘Tourists f*** off’ became an almost ubiquitous sight in Berlin’s districts; fierce debates at community meetings about the conversion of residential apartments into holiday rentals became more frequent. Anonymous posters citing Hans Magnus Enzensberger’s famous words – ‘The tourist destroys what he seeks by finding it’ (Enzensberger 1996) – echoed a sentiment that a growing number of residents expressed quite openly: the city, they felt, was in danger of falling victim to its own success.

Meanwhile, on the other side of Europe, in August 2014 photographic evidence of an incident which took place in Barcelona made headlines in the local, national and international press: three young Italian male tourists wandered around naked in broad daylight in the streets and shops of La Barceloneta, Barcelona’s waterfront neighbourhood, without being stopped by the police and oblivious to the outrage caused to passers-by and locals. Angry residents posted pictures on social media, which prompted a deluge of journalistic attention beyond the boundaries of the Spanish state (i.e. Kassam 2014). Various residents’ associations from the historic district of Ciutat Vella – Barcelona’s Old City, which concentrates a significant part of tourist flows – had, for years, been campaigning against the negative impacts of the tourist economy on their neighbourhoods, such as the proliferation of short-term rental apartments, problems of noise and anti-social behaviour linked with ‘drunken tourism’, or the occupation and commodification of public space by cafe terraces. These associations got together and started quasi-daily demonstrations (Figure 1.2) outside the District and City halls to demand that politicians implement tighter control and regulation of the city’s tourism economy and, more broadly, to plead for a change in the city’s urban development model under the motto ‘Barcelona is not for sale’. A well-known Barcelona housing activist, Ada Colau (2014), wrote an opinion piece in English in the Guardian to explain to an international audience why ‘mass tourism can kill a city – just ask Barcelona’s residents’. Eighteen months later she became Barcelona’s new mayor, following local elections which saw a left-wing grassroots movement which emerged out of citizens’ activism and local urban social mobilization get into power, Barcelona en Comú. One of the central themes of the ‘Barcelona in Common’ campaign was tourism’s negative impacts on the city’s socio-economic fabric and the need to ‘regulate the sector, return to the traditions of local urban planning, and put the rights of residents before those of big business’ (Colau 2014: n.p.).

Source: Jonathan Adami.

Source: Maurice Moeliker.

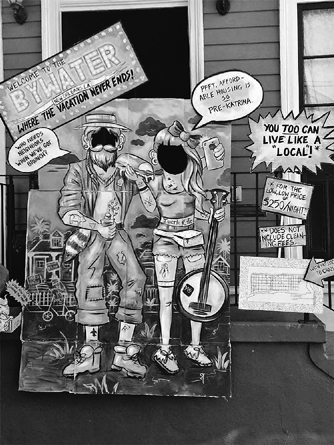

Currently the third and fifth most visited cities in Europe by bednight volumes (European Cities Marketing 2014), both Berlin and Barcelona have recorded particularly steep increases in tourist numbers since the early 1990s. It is perhaps no surprise that the impact of tourism on these cities’ urban and social fabric have been increasingly contested. Yet manifestations of discontent, protest and resistance like the ones described above are not as exceptional as Berlin’s and Barcelona’s local media have tended to describe them. In Italy, individuals and groups are campaigning to help ‘Save Florence’ and the art-infused city’s local heritage from the damage inflicted by mass tourism (Figure 1.3). In New Orleans, new hotel developments as well as a proliferation of unlicensed short-term rentals is provoking dissent by neighbourhood groups and affordable housing advocates who are concerned that the ‘Big Easy’ is ‘in danger of losing its identity’ (Moskowitz 2015) (Figure 1.4). New companies such as Airbnb have exploited the profits to be made from the so-called ‘sharing economy’ by offering online advertising and management platforms for individuals to rent their home, or part thereof, for short-term periods of time to tourists and visitors. This is having visible impacts on local housing markets, and similar protests have emerged in other cities (e.g. San Francisco – see Opillard in this volume). In Lisbon, local residents have formed a community group called ‘People live here’ (Aqui mora gent) in response to the city’s growing ‘party tourism’ phenomenon. Meanwhile, in Hong Kong, there has been a strong backlash against the large numbers of mainland Chinese travellers (see Garrett in this volume), while cities in Central and Latin America and the Caribbean too are replete with examples of tourism-related struggles (see Betancur 2014).

Source: D. L. Ashliman.

Across the globe, from established tourist cities such as Venice or Prague to less traditional tourist destinations in both the global North and South, there is thus mounting evidence that points to an increasing politicization of what hitherto had essentially been a non- or minor issue in urban political struggles in most cities. This politicization manifests itself in different ways: in some contexts residents and other stakeholders take issue with the growth of tourism as such, as well as the impacts it has on their cities; in others, particular forms and effects of tourism are contested or deplored; and in numerous settings, as will be discussed in this volume, contestations revolve less around tourism itself than around broader processes, policies and forces of urban change perceived to threaten the right to ‘stay put’, the quality of life or the identity of existing urban populations.

It might nonetheless be misleading or premature to conclude that there is a global ‘revolt against tourism’, as Elisabeth Becker (2015) recently argued in the New York Times. Clearly, we are seeing a proliferation of forms of contestation – big and small – surrounding tourism. However, given their oftentimes different causes, characteristics and concerns – and taking into account that many of them are not against tourism as such – one should avoid the pitfall of making them appear more similar or uniform than they are in reality. This volume has been motivated by the fact that the rise of urban tourism as a source of contention and dispute has thus far received relatively little systematic attention and analysis. Critical urban and tourism studies have certainly produced valuable empirical and theoretical findings regarding what we have described as urban tourism’s increasing ‘politicization from below’. However, to our knowledge, so far no coordinated attempt has been made to provide a wide-ranging international overview (in English) of the types of controversies, conflicts and protests that have emerged in response to tourism’s ascendancy within the contemporary urban fabric, as well as its increasingly significant role in the economic and political agendas of urban policy-makers. The present volume attempts to fill this gap. It contends that controversies, debates and protests surrounding urban tourism not only warrant investigation in their own right, but also offer a useful lens through which fresh light can be cast on the profound role tourism plays in contemporary cities, as well as on the current ‘urban moment’ more generally with its attendant conflicts and contradictions. In theoretical terms, the book seeks to connect the largely discrete yet interconnected disciplines of ‘urban studies’ and ‘tourism studies’. More widely the book borrows from, and links up with, debates from the following disciplines: urban sociology, urban policy and politics, urban geography, urban anthropology, cultural studies, urban design and planning, tourism studies and tourism management.

Source: Caroline Thomas.

This introductory chapter aims to establish the context within which the rise of urban tourism as a powerful force of urban change and as a source of contention is situated. Conceptualizing the rise of (urban) tourism as both indicative and constitutive of broader processes of economic and social change, it will first provide some critical reflections on the nature of tourism as a social phenomenon. The section that follows will discuss the formidable growth of urban tourism in recent decades, and the role it has acquired in urban development strategies and governance. The subsequent section will provide a short review of the transformation of urban conflicts and social movements in cities in general. Tourism is only one – albeit increasingly potent – force of rapid urban change and is closely intertwined with other forces, as further discussed below, which may themselves be the object of contestation. The subject matter of ‘protest and resistance in the tourist city’ is thus best understood as part of wider struggles around contemporary urban restructuring, the transformation of urban governance and the ‘Right to the City’, even if not all tensions surrounding urban tourism easily fit into such a framework of analysis. Embedded in a discussion of the book’s objectives and underlying research questions, the final section will present a taxonomy of the conflicts, contestations and struggles surrounding tourism that can be observed in cities of the Global North and South and thereby introduce the chapters of the volume.

Coming to terms with (urban) tourism

The fundamental premise that underpins this volume is as simple as it is frequently overlooked, namely that tourism is fundamentally political. In fact, the process of defining, conceptualizing and measuring tourism is itself, from the onset, deeply political. The way tourism is accounted for and made sense of locally, for instance, has usually been shaped by the hotel industry and associated businesses. As the key local stakeholders in tourism development, they often purport what counts as tourism and what does not, and most statistics and data compiled on the local level reflect their interests and needs: the emphasis rests on visitors staying in hotels and similar establishments while day-trippers, people visiting friends and relatives, or those renting short-term (often unlicensed) holiday apartments were at least until recently either not accounted for or only insufficiently so. As a result, the conventional wisdom in the policy, scholarly and media spheres has tended in most contexts to equate ‘tourists’ with ‘hotel guests’ – a restrictive and increasingly flawed definition.

Yet what is actually meant by the term ‘tourism’? And what does it mean to be a tourist? There is still much contention and debate over the meaning of those terms, and it is beyond the scope of this chapter to revisit the intense debates that have surrounded those issues. For the purposes of this volume, we adopted a deliberately broad understanding of tourism. A tourist, in line with the definition by the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), is understood as someone who ‘travels to and stays in places outside the usual environment for not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business and other purposes’ (UNWTO 1995: 1). Tourism is conceptualised as ‘the sum of phenomena and relationships arising from the interaction of tourists, business suppliers, host governments, and host communities’ (McIntosh and Goeldner 1990, cited in Hall and Jenkins 1995: 7).

The pervasiveness of tourism for contemporary societies rests not only with the ever-growing numbers of people participating in it, but also with the wider impacts it has on the world we live in and the way we look at – and act in – it. While not going as far as Munt’s assertion that we live in a world in which ‘tourism is everything and everything is tourism’ (cited in Gale 2008: 4), we nonetheless contend that it is hard to overestimate tourism’s influence as a social force. In today’s hyper-connected world, few places remain whose cultures, economies, social relations and spatial dynamics are not impacted by tourism. Moreover, the ‘gaze’ (Urry 1990) of ever more consumers, entrepreneurs and policy-makers is increasingly shaped by tourism.

Furthermore, rather than grouping tourists into a homogenous whole and conceiving tourism as a distinct and easily separable phenomenon, we stress that tourism is highly variegated and that its forms and practices intersect and overlap with other patterns of consumption, production, mobility and leisure. The boundaries between tourist and non-tourist practices in cities, for instance, have always been fluctuating, but have become increasingly blurred in recent decades as a result of increasing global mobility, a growing fluidity between travel, leisure and migration, a breakdown of the conventional binary divide between work and leisure, a disruption in the concepts of ‘home’ and ‘away’, as well as changes in the consumption patterns and preferences of middle- and upper-class city dwellers. Affluent city residents have been found to increasingly behave ‘as if tourists’ in their own cities, that is to engage in activities that are indistinguishable from those of visitors (Lloyd and Clark 2001: 357). Tourists visiting cities are increasingly likely to be frequent and experienced travellers who are familiar with the places they visit and/or seek to experience ‘ordinary’ or mundane spaces as locals would. Besides, growing numbers of ‘temporary city users’ (Costa and Martinotti 2003; Maitland and Newman 2009) that are neither readily identified as ‘tourists’ nor as ‘locals’, e.g. second-homers, frequent business travellers on short-term assignments, mobile ‘creatives’ or artists in temporary residence, or students going on exchanges, also make it increasingly difficult to establish a clear-cut distinction between tourism and everyday life. These ‘temporary city users’ have become more prevalent in a number of cities over the past decades and their practices have visible impacts on urban spaces and socio-economic relations in the city (Novy 2010).

As regards the supply side, sharp demarcations are also difficult to establish. Tourism relates to production activities that are dispersed across different branches of the economy; tourism resources (apart from accommodation) are in most urban contexts rarely solely produced for, or consumed by, tourists and efforts by local elites to transform urban environments into ‘places to play’ (Judd and Fainstein 1999) are rarely, if ever, exclusively driven by a desire to cater to the ‘visitor class’ (Eisinger 2000) alone. Rather, as will be discussed below, such efforts have to be seen in the context of a more general turn towards leisure and consumption in urban economic development. This underscores the need to address tourism not in isolation from, but in the context of wider social, political and economic processes. This has been recognized for some time: grounded in development and dependency theory, the first critical analyses of tourism as an activity predominantly organized by the capitalist system flourished in the 1970s (Jafari 2003; Weaver 2004). Since then, there has been a significant expansion of scholarship from both political-economic as well as cultural-interpretive perspectives that have highlighted the embeddedness of tourism within broader processes of economic and social change, such as globalization, industrial and regional restructuring, the turn towards entrepreneurial governance or the rise of ‘postmodern’ consumerism and the associated commodification of cultures and places.

That tourism is not only imbricated with but also central to many of the critical issues relevant to the understanding of contemporary societies was, meanwhile, for a long time not acknowledged by scholars outside the field of tourism studies. Instead, many scholars in sociology, geography and related disciplines did not view tourism as worthy of serious study. The sustained growth of tourism in recent decades has defeated such a view. According to the UNWTO (2015), tourism worldwide – as measured by international arrivals – has experienced a more than 40-fold increase, from approximately 25 million in 1950 to more than 1.1 billion in 2014. This trend is set to continue: international tourist arrivals worldwide are expected to reach 1.4 billion by 2020 and 1.8 billion by the year 2030. Urban tourism is thereby said to represent a particularly dynamic segment of tourism activity. Reliable statistics are hard to obtain, yet it is widely assumed that cities represent a key driver of overall tourism volume growth: a recent industry report suggested for instance that the volume of city trips increased by a staggering hard-to-believe 47 per cent from 2009 to 2013 alone (ITB 2013: 7).

Despite this – and the fact that urban environments worldwide have historically been among the most significant of all tourist destinations (Karski 1990) – urban tourism was for a long time not afforded much attention. Urban tourism suffered until well into the 1990s from what Ashworth (1989) famously called a ‘double neglect . . . whereby . . . those interested in the study of tourism have tended to neglect the urban context in which much of it is set, while those interested in urban studies . . . have been equally neglectful of the importance of the tourist function of cities’ (p. 33). This has changed in recent years, as urban tourism has been receiving an increased amount of scholarly attention. Works which address the chief concerns of this volume remain rather scarce, however, as most research thus far took a ‘practical’ and prescription-minded perspective and ignored the premise exposed earlier: that (urban) tourism is eminently political and consequently prone to controversy and social conflicts.

From marginal to integral: tourism’s changing role in urban development politics and processes of urban change

That tourism transforms the spaces in which it develops, and that the changes it brings about are not always positive or desirable, has been recognized ever since the existence of tourism as a known phenomenon. Henri Stendhal, who coined the word ‘tourist’ to refer to an individual who travelled for pleasure, commented peevishly on the growth of tourism mobility that occurred during his lifetime. Writing about a visit to Florence in 1817, he complained that the city of his dreams was being occupied by too many visitors and remarked that Florence was ‘nothing better than a vast museum full of foreign tourists’ (cited in Culler 1981: 130). Conflicts between tourists and locals have also been documented since the 1800s, such as tensions in coastal towns in early Victorian Britain in response to the growth of (working-class) leisure mobility (see Morgan and Pritchard 1999; Churchill 2014) or the resentment that early forms of ‘urban poverty tourism’ (Steinbrink 2012) sparked in cities like London or New York. Such conflicts – while in no way trivial to those involved – were in the wider scheme of things of rather minor significance, however, and were afforded relatively little attention.

As a scholarly concern, urban tourism generally was, as noted earlier, for a long time deemed a peripheral topic, and policy-makers and planners – a few exceptions notwithstanding – typically also devoted only little attention to what was widely considered a ‘marginal social activity’ (Beauregard 1998: 220). Today the opposite is true, as a result of broad processes of economic, social and political change widely analysed in urban geography, sociology and politics. Cities – as a result of economic globalization and the rescaling and transformation of state activity – have been subjected to a series of unprecedented changes involving a profound restructuring of their economic bases, a transformation of their demographic composition and social class structure, as well as a significant remaking of the contexts for local governance. Cities’ economies experienced a marked shift away from manufacturing towards service and knowledge-based industries. Urban politics became more and more a politics of economic development and entrepreneurialism as cities were forced into a global interurban competition for investment and economic growth. Consumption, culture and leisure moved centre stage in cities’ political economy as productive sectors in their own right and as favoured means to achieve competitive advantage. And urban planners and policy-makers became increasingly preoccupied with place marketing and image-making policies so as to valorise cities as value-generating units (Harvey 1989, 1990).

Tourism emerged in this context as an attractive development option not only because of the increased recognition of its economic potential. Rather, it was seen as compatible with and conducive to other policies that came to characterize the ‘new urban politics’ from the late 1970s and early 1980s onwards (Hall and Hubbard 1998). Examples of the latter include traditional amenity-based development strategies to lure investment capital, residents and businesses; culture-based strategies (Bianchini and Parkinson 1993; Zukin 1995; Evans 2001; Miles 2007), or the more recent ‘creative city’ craze that has gripped mayors, planners and policy advisors in Europe, North America and elsewhere. Tourism moreover has been perceived by urban policy-makers and elites as an economic sector easy to promote, requiring little public investment besides promotional campaigns to stimulate the overall growth of the sector (Greenberg 2008; Colomb 2011) and measures supporting the ‘tourist-friendly’ reshaping of the city’s spaces (e.g. through more policing of tourist hotspots). Against the backdrop of declining urban industrial bases and fiscal crises, it increasingly turned into a critical means to reposition cities in a rapidly changing economic environment and/or reaffirm their standing in an evolving metropolitan hierarchy (Fainstein et al. 2003: 2). Following the 2008 economic crisis, which affected global flows of foreign direct investment and visitors, many city leaders have often chosen to intensify, rather than roll back, place marketing and tourism promotion policies, even in a context of fiscal austerity and massive cuts in public spending.

Such arguments are more applicable to some contexts than others. Most of the foundational analyses of contemporary urban restructuring, including cities’ shift towards leisure and consumption, are overwhelmingly rooted in the experience of European and North American cities. In many parts of the world, urban dynamics differ decisively from those whose experience dominates the (Anglophone) urban studies literature to this day (see Robinson 2006). Contrary to the suggestion by Fainstein et al. (2003: 8) that ‘virtually every city sees a tourism possibility and has taken steps to encourage it’, the elevation of tourism as a policy objective has not reached all places and contexts. But places that do not aspire to develop tourism get fewer and fewer – even the North Korean government has begun to market the country as a tourist destination – and many of the above-mentioned trends first observed in Western cities are also increasingly influencing the trajectories of cities in other contexts as well, in part due to the global emulation between city elites (see, inter alia, Broudehoux 2004; Yeoh 2005) and the globe-trotting travels of various forms of neoliberal urban policies (McCann and Ward 2011).

Neoliberalization refers to a combination of two processes: ‘the (partial) destruction of extant institutional arrangements and political compromises through market-oriented reform initiatives; and the (tendentious) creation of a new infrastructure for market-oriented economic growth, commodification, and the rule of capital’ (Brenner and Theodore 2002: 362). While neoliberalization strategies display important geographical variations (ibid.), many authors stress that place marketing and tourism promotion form a key component of the neoliberal policy experiments carried out in various cities and regions. Urban leaders have supported various initiatives to fuel the growth of the tourism sector in their cities in partnership with the private sector, mobilizing the cultural, social and physical capital present in their city in the process (see, inter alia, Hoffman et al. 2003; Spirou 2011). Frequently assisted or influenced by international institutions such as the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank, local and national governments in the Spanish and Portuguese-speaking Americas had begun, for instance, already in the late 1970s, to pursue the redevelopment of central locations, especially, heritage/historic centres, for tourism consumption, and in doing so transform them into ‘wealth production machines’ and prepare the ground for tourism gentrification (Betancour 2014: 4). Such efforts are prominently discussed by Latin American researchers and viewed as crucial expressions of a specific model of urban development that emerged as a result of the neoliberal reforms undertaken in the region (Janoschka et al. 2014).

In parallel, it is well documented that the restructuring processes of recent decades – in which activities previously deemed peripheral to the ‘productive city’, such as tourism and leisure, moved centre stage in cities’ political economy – coincided with and contributed to an intensification of inequalities of various kinds. The contemporary city is not only one increasingly ‘consumed by consumption’ (Miles and Miles 2004: 172), but also one that is increasingly fragmented or divided. Urban inequality has grown considerably in most countries of the world and it has become increasingly clear that there is a flip side to the ‘renaissance’ or ‘triumph’ cities are said to have experienced in recent decades (see, inter alia, Porter and Shaw 2013). Escalating rents and housing prices make them increasingly unaffordable for low-income groups, while the most dynamic and desirable destinations among them are increasingly turning into exclusive playgrounds for the rich. That increasing social polarization and inequality, as well as gentrification and the destruction of low- and mixed-income communities, have become defining characteristics of the current urban moment is not accidental but in part the direct, often even deliberate, result of political actions such as the reduction of welfare spending, the dismantling of public housing and the shift towards market-oriented and property-led urban development strategies.

Urban tourism is intrinsically related to these trends in several ways. In terms of public policy, it has emerged as a popular priority in the boosterist agendas of local governments and growth coalitions, thus being granted public funding and investments which may have opportunity costs for other policy fields (e.g. welfare). Urban tourism has also frequently been found to perpetuate lopsided development patterns and contribute to existing or new patterns of urban inequality. Already in the 1970s there were significant debates about the uneven relations tourism entails and creates, but these debates were confined mainly to non-urban destinations – especially poorer, so-called ‘Third World’ countries. Dismissing ‘the economics of tourism’ and especially its central assumption that tourism represents a ‘passport for development’ that is unequivocally good for local communities, Turner and Ash were among the first to point out that the tourism industry involved substantial opportunity costs (see Pleumarom 2012). They described how tourism schemes overexploited cultural and natural resources, inflated prices beyond the reach of average levels of purchasing power, and disrupted and displaced traditional economies:

The locals build the resorts and serve in them which, if fully controlled by foreigners, will contain few really worthwhile jobs. In the meantime, the fields return to weeds; the locals lose their ability to produce anything of direct practical use to themselves. While they’ve been building the resorts, they haven’t been building the schools, the irrigation systems or the textile factories which would educate, feed or clothe them [. . .] For the sake of this industry, they can lose their land, their jobs and their way of life – for what?

(Turner and Ash 1975, cited in Pleumarom 2012: 94)

Such intellectual critiques gave rise to the search for alternative development paths which were more conducive to local host communities’ well-being (see Jafari 2003; Weaver 2004). However, their impact on discussions concerning tourism in cities remained for a long time rather limited. More extensively discussed in urban (tourism) research is another important line of criticism levelled against tourism: that tourism contributes to a commodification and destruction of cultures and places, and tends to set dynamics in motion that can lead to an erosion of precisely those attributes that constituted the original attraction for tourists to visit (Sorkin 1992; Zukin 1995; Harvey 2001).

These two lines of criticism have taken on particular relevance in the case of urban tourism, not just because of its quantitative growth, but also because of qualitative changes in the nature and geography of tourism flows. In many cities, urban tourism has spread geographically across urban space to new areas which lacked conventional tourist attractions – and were until recently not planned or marketed as tourist zones. New neighbourhoods have become increasingly desirable sites of tourism, leisure and consumption, e.g. the districts of Prenzlauer Berg, Friedrichshain, Kreuzberg and Neukölln in Berlin (Novy and Huning 2008) or London’s East End (Brick Lane and Shoreditch (Maitland 2006). In some cities of the Global South, e.g. Brazilian and South African cities, tourists have been increasingly attracted to informal settlements, something referred to as ‘slum’ or ‘favela tourism’ (Frenzel et al. 2012; Broudehoux in this volume). Throughout the 1990s and the 2000s, such neighbourhoods became established destinations widely mentioned in tourist guidebooks, especially those catering for a young audience eager to ‘go off the beaten track’ (Maitland and Newman 2009).

The emergence of these neighbourhoods as ‘new tourism areas’ (Maitland 2006, 2007; Maitland and Newman 2004) is the outcome of the convergence of a number of trends (Novy and Huning 2008) which can be broadly classified into sociological, demand-related factors (i.e. the diversification of tourist audiences; the changing cultural practices of the new middle classes, e.g. in Europe in part due to the rapid development of low-cost airlines; the blurring of boundaries between tourism and other forms of mobility and practices of ‘place consumption’ (see Selby 2004)) and supply-side explanations (which include the role of local policies, place promotion and tourism marketing). In many cities, the local state and tourism marketing organizations have begun to promote such ‘new tourism areas’ for their vibrant sub- and counter-cultural and artistic scenes and ‘authentic’, ‘off-beat’ feel, for example in Berlin (Novy and Huning 2008; Colomb 2011, 2012), Amsterdam and Melbourne (Shaw 2005) or Paris (Vivant 2009). Ethnic diversity too has been mobilized in urban tourism strategies, e.g. in New York (Hoffman 2003), London (Shaw et al. 2004) or Berlin (Novy 2011a, 2011b). Occasionally described as ‘touristification’ (Bianchi 2003; Stock 2007), such processes of symbolic and physical appropriation and commodification have consequences for the spaces and people concerned, as discussed below. This multifaceted transformation of urban spaces under the influence of tourism flows, and the role of increasing tourist demand as a contributing and accelerating factor in broader urban transformation processes (e.g. gentrification), explain why urban tourism has become an increasingly contested topic, and why tourists have become an increasingly popular bogeyman in conflicts concerning urban restructuring processes.

Protests, resistance and (new) urban social movements in the tourist city: contestations in context

Many of the forms of protest and resistance surrounding urban tourism which are explored in this volume (further discussed in the next section) need to be put into the context of recent developments in the fields of urban activism and protest more generally – and the ways scholars have made sense of them. This section gives a brief overview of these developments, although it should be acknowledged that not everywhere can we observe structured or visible forms of collective mobilizations surrounding urban tourism. In some cities, as will be discussed in a number of chapters, we can discern micro-practices of resistance or individual adaptation to tourism flows and their impacts, which do not take the shape of fully-fledged social mobilizations for various reasons.

The role of the city as a space for the mobilisation and staging of protest has attracted increasing attention in recent years and a lot of developments, although disparate and disjointed, point to an upsurge of urban mobilisations and contestations. These mobilisations and contestations do not always revolve around territorially bounded urban issues. Instead, cities frequently – as was, for example, the case with Occupy New York, the Arab Springs or the Puerta del Sol protests in Madrid – serve as arenas within which broader political struggles that are not primarily urban-oriented are fought (Miller and Nicholls 2013: 452; Rodgers et al. 2014). Significantly, however, urban development processes and urban politics as such have also become increasingly contested in a variety of contexts and in a wide range of forms. This in itself is not new: the concept of urban social movements coined by Castells (1977) captured the emergence, in the 1960s and 1970s, of new social movements ‘rooted in collectivities with a communal base’ and/or with ‘the local state as their target of action’ (Fainstein and Fainstein 1985: 189). Castells’ early categorization of urban social movements (1983) identified three types: those focusing on issues of collective consumption; those defending the cultural and social identity of a particular place; and those seeking to achieve control and management of local spaces, institutions or assets. The concept of urban social movements was subsequently broadened to refer to citizen action centred on urban issues, irrespective of its potential or actual effects (Pickvance 2003). Such social mobilizations have taken different forms and shapes in different national and local contexts, and have followed a path-dependent trajectory of transformation influenced by local opportunity structures and specific combinations of state-market-civil society relations.

Mayer’s conceptualization of the evolution of urban social movements over time (2009), while simplifying a complex reality, points to some common trends of change across many parts of the Global North. In the 1990s, the strengthening of neoliberal municipal agendas which mobilized urban space as an arena for growth and market discipline led to a renewed politicization of urban struggles which challenged the effects of urban entrepreneurialism, increasing policing and surveillance and corporate urban development (e.g. anti-gentrification struggles under slogans such as ‘Reclaim the Streets’). Recent scholarly contributions on urban social movements and contestations of contemporary forms of urban governance have highlighted the continuous transformation of the scope and agenda of movements since the 2000s in the face of the ‘increasingly authoritarian, uneven and unjust nature of an ever more “neoliberalized” global political economy’ (Purcell 2003: 564). In the context of the transformation of urban economic development agendas discussed in the previous section, and more recently of the ‘austerity politics’ following the 2008 economic crisis, several scholars have identified the emergence of new types of movements and coalitions which have begun to challenge, in particular, the consequences of the neoliberalization of policies in various fields (Koehler and Wissen 2003; Leitner et al. 2006; Mayer 2009, 2013).

Henri Lefebvre’s concept of the ‘right to the city’ (1968) – a right both to use urban space and to participate in its social and political production – has in fact become a ‘major formulation of progressive demands for social urban change around the world’ (Marcuse 2009: 246). Activists in many parts of the world with various backgrounds and objectives have adopted it as a motto for broad urban social mobilizations protesting economic and environmental injustice, austerity politics, speculative gentrification and displacement, neighbourhood destruction, homelessness, etc. and demanding the creation of more just and democratic cities (Brenner et al. 2012). The US-based ‘Right to the City’ Alliance is one such example – a coalition of community-based groups, worker and labour rights’ organizations, housing rights campaigners, environmental activists and migrant and minority groups united in their opposition against neoliberal economic and urban policies and social and environmental injustices of various kinds (Marcuse 2009; Mayer 2009).

Nicholls (2008) argues that the formation of such broad coalitions often results from a particular urban restructuring threat which acts as a ‘structural push’. Tourism and its impacts, in some localities, can be perceived as such a ‘threat’ by local actors, when it reaches a certain tipping point (e.g. as has been the case in Barcelona in recent years). It may crystalize the discontent which exists in a latent way with regard to various processes of urban and neighbourhood change which have negatively affected residents over the years, and are not caused by tourism per se. The city is a site of struggles over what type of urban development model should be prioritized, and tourism is often part and package of a broad economic model which has increasingly generated popular discontent. As the majority of chapters in this volume demonstrate, the conflicts surrounding tourism are rarely only about a crude tension between ‘hosts’ and ‘guests’, but instead reflect wider struggles over urban restructuring and socio-spatial transformations and who benefits and loses from them. A particularly good example of this is the complex links between ‘touristification’ and ‘gentrification’ processes, which are difficult to disentangle. The growth of tourism has been one factor among others which has fuelled changes in the residential markets of various cities. The increase in new hotels and hostels, as well as the sharp rise in the conversion of residential apartments into holiday rentals – a major topic of contention in various cities such as New York, Paris, Barcelona, Berlin or San Francisco (see Opillard in this volume) – has contributed to housing shortages and rent increases in neighbourhoods which were already affected by gentrification processes.

Additionally, there is further evidence that in several cities marked by a visible ‘cultural’ or ‘creative’ turn in urban economic development – i.e. where the government has promoted a development agenda based on the marketing and promotion of creative industries, cultural consumption and urban tourism – a surge in activism and social mobilization around the consequences of such policy orientations has been witnessed (Novy and Colomb 2013). In various cities, protests led by coalitions of various actors, including cultural producers and ‘creative milieux’, have increasingly voiced their concerns about the ways in which culture and the arts are instrumentalized in post-industrial image economies, how cities’ existing social and cultural capital – old and new – is lost or commodified as a result of rampant gentrification, commercial development and/or tourism, and how increasing rents displace low-income residents, cultural producers and alternative social and subcultural projects. In that context it is important to note that former urban social movements which became consolidated into more established community initiatives can themselves become the object of tourism practices or of the tourist gaze (see Fraeser in this volume), in particular in the case of alternative cultural spaces and initiatives such as (former) squats (see Pruijt 2003, 2004, Uitermark 2004 and Owen 2008 on the – contested – transformation of part of the Amsterdam squatting movement into providers of cultural services). Just like Mayer (2003) showed how the social capital present in some urban social movements has been instrumentalized by the state for economic competitiveness and social cohesion objectives, ‘creative’ and ‘cultural’ capital can be instrumentalized in the same way in marketing and economic development policies which seek to encourage urban tourism, consumption and the attraction of ‘creative’ workers and firms more generally (Colomb 2011).

Harvey, in Spaces of Capital (2001), stresses that contradictions – and thus conflict – emerge from this appropriation and commodification of a locale’s cultural capital upon which consumption-driven urban economies and tourism are based. First, the exploitation of local marks of distinction with the potential to yield monopoly rents inevitably tends to lead to homogenization, which decreases uniqueness and ‘erase(s) the monopoly advantage’ which can be extracted from a place, item or event – something commonly discussed by critical cultural geographers in their investigation of tourism and place marketing strategies around the world (e.g. Kearns and Philo 1993). Second, drawing on uniqueness and local specificities to maintain a competitive edge and appropriate monopoly rents implies that capital has to ‘support a form of differentiation and allow of divergent and to some degree uncontrollable local cultural developments that can be antagonistic to its own smooth functioning’ (Harvey 2002: n.p.). These contradictions, according to Harvey, open ‘new spaces for political thought and action within which alternatives can be both devised and pursued’, but also could ‘lead a segment of the community concerned with cultural matters to side with a politics opposed to multinational capitalism’ (2001: 410) and favour alternatives based on different kinds of social and ecological relations (2002). This can help generate new coalitions or mobilizations bringing together the materially ‘deprived’ and the intellectually and politically ‘discontented’, as recent ‘forms of (post-)Occupy collaborations that bring together austerity victims and other groups of urban “outcasts” with (frequently middle-class-based) radical activists’ have shown in some places (Mayer 2013: 5).

Tourism related protests are, as several chapters in this volume show, frequently part of, or at least connected to, wider efforts to defend and reclaim the right to the city, challenge the predominance of exchange value over use value in the production of the built environment, and create ‘cities for people, not for profit’ (Brenner et al. 2012). At the same time, however, it is also important to recognize that not all tourism-related mobilizations readily slot into such a framework of analysis, and that not all of them can reasonably be regarded as ‘progressive’. Tensions surrounding tourism involve different actors with different motives and agendas, and mobilizations clearly can be defensive, reactionary, exclusionary or even racist. To not recognize that NIMBYism (‘Not In My Back Yard’), i.e. the defence of narrow interests around issues of individual property and consumption, is at play in some cases would be naive. It is equally important to acknowledge that tourism (and tourists) often provides a scapegoat for urban ills that they are barely responsible for. Moreover, (middle-class) individuals who are prolific travellers themselves, or came to settle in an urban area for the same reasons which draw visitors, often seem to complain loudest when tourism-related issues surface in their neighbourhoods. It is therefore not all that surprising that voices critiquing or resisting tourism are regularly accused of being hypocritical, self-serving and parochial. Such accusations, while sometimes true, are also regularly wrongly employed by representatives of the tourism industry, local media or policy-makers to discredit legitimate local mobilisations, stifle debate and draw attention away from the fact that tourism development has in many contexts emerged as an object of increasing contestations for understandable reasons. One consequence of these contestations has been that tourism in cities is increasingly recognized as what it is: increasingly consequential and inherently political (Burns and Novelli 2007; Hall 1994). Its political nature stems from the environment and circumstances in which it takes place, the decisions and underlying interests and power structures – sometimes proximate and sometimes remote – that shape it, as well as the profound, frequently socially and spatially uneven outcomes it involves.

Tourism’s ‘politicization from below’

The aim of this book is to analyse and better understand what type of conflicts and contestations around urban tourism have unfolded in contemporary cities across the world, and to explore the various ways in which community groups, residents and other organizations have responded to – and challenged – tourism development in cities in an international perspective. Our focus lies on the rise of urban tourism as a source of contention and the actors, causes and consequences of the multiple and variegated struggles around tourism that have emerged in recent years. The guiding questions which have structured the volume are as follows: Where and at what scale do conflicts and protests occur? What do they revolve around? Who are the actors and protagonists involved? What are their motives, demands and agenda, and how do they articulate them? Who are the target(s) of their demands or protests – the state, the tourism industry/the market, tourists? What impacts and consequences do manifestations of protest and resistance have? In particular, how do the local state and the tourism industry respond to them? What kinds of alternative approaches to tourism development (if any) are being proposed?

The present volume seeks in a modest way to shed light on these questions by bringing together a collection of theoretically rich and empirically detailed contributions by scholars from around the world. The aim is not to provide an exhaustive or representative overview, but to explore the diversity of struggles around urban tourism across different places and spaces, as well as the variety of disciplinary perspectives which can be used to make sense of these. This is reflected in the diverse backgrounds of the contributors to this volume – sociologists, anthropologists, geographers, political scientists, planners and architects. While the 16 chapters selected for the volume adopt a deliberately broad view of the subject, the majority of chapters align with our premise that tourism is increasingly the cause of unease and contestation and therefore experiences a ‘politicization from below’. The contributions to the book cover more than 16 cities across Europe, North America, South America and Asia, which have been the recipients of increasing tourist flows. In those cities, residents have begun to note the effect of tourism on their daily life more clearly.

In some cases, this has led to the emergence of forms of collective mobilizations specifically set up around tourism-related issues, either at the city-wide scale (e.g. in Berlin, Chapter 3; in Hong Kong, Chapter 6; in Venice, Chapter 9; or in Barcelona) or in particular neighbourhoods or sites (e.g. in Barcelona’s Park Güell, Chapter 13). In other cases, existing forms of community activism (e.g. residents’ or neighbourhood associations, housing rights collectives) or existing urban social movements have increasingly turned their attention towards tourism-related issues and incorporated them into their agenda as part of broader claims about: the defence of quality of life and public space management (e.g. in Paris, Chapter 3); neighbourhood restructuring, heritage protection and the ‘right to stay put’ in historic city centres (e.g. in Prague, Chapter 4 and in Valparaíso, Chapter 7); housing shortages, tenants’ rights and rapid gentrification (e.g. San Francisco, Chapter 7); the desirability of new urban projects and questions of urban density (e.g. Santa Monica, Chapter 5); or the social impacts of mega-events (e.g. Belo Horizonte, Chapter 12 and more generally in many cities which were candidates for hosting the Olympic Games, Chapter 11). In other contexts, no structured or visible forms of collective mobilizations surrounding urban tourism might exist, but micro-practices of resistance (e.g. in the use of space by locals) against the impacts of touristification and forms of ‘micro’ or infra-politics’ (see Chapter 2 for a discussion) can be uncovered (e.g. in Paris, Chapter 2 and in Singapore, Chapter 16).

All cities covered in the book are complex local societies divided by social, economic, class, ethnic and other lines. Local residents, individuals and groups are not homogeneous ‘communities’ who react to the prevalence of urban tourism in the same way. The potential benefits of urban tourism (and its costs) are consequently also the object of struggles between people, economic actors and social groups, who may enter into conflicts about: who can and should reap the positive benefits and profits generated by the tourist economy, based on unevenly distributed forms of cultural and economic capital (e.g. in Shanghai, Chapter 15 and Buenos Aires, Chapter 14); which kind of tourism they wish to see in the space they occupy (e.g. in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, Chapter 10 or in a squatted building complex and alternative social-cultural centre in Hamburg, Chapter 17); the political, symbolic and economic use of tourism in societies marked by ethno-nationalist conflict (e.g. in Belfast, Chapter 8 and to an extent in Hong Kong, Chapter 6). In some contexts, thus, tourism has the capability to exacerbate or mitigate existing or latent urban conflicts (among social groups and between particular groups and the state) seemingly unrelated to tourism in the first place (see Chapter 8 on Belfast).

The main issues and themes of contention in most of the struggles surrounding urban tourism, at the risk of oversimplification, are about:

• the negative effects and externalities caused by tourism on people and places (which tend to become more intense and widely spread as tourism increases) (Table 1.1);

• equity impacts, i.e. the distribution of the costs and benefits of urban tourism among various groups and spaces – often very unevenly spread;

• the politics of urban tourism, including especially what is perceived as a skewed political agenda in favour of the ‘visitor class’ and the prioritization of development for exchange value over development for use value in the definition and conduct of public policies.

| ECONOMIC |

• Changing market demand for goods and services (from serving local needs to catering for the visitor economy, e.g. bars, souvenir shops) • Loss of small independent shops and growth of chain and franchised establishments • Increasing commercial rents and consumer prices → (Commercial/retail gentrification (loss or displacement of resident-serving businesses) • Increase and spatial expansion of tourism accommodation industry (hotels, hostels, bed & breakfast establishments, commercial vacation rental operators) • Increase in the number of second homes • Increase in the number of (short-term) rental housing units put on the market by individuals (owner-occupiers, tenants or landlords renting part or all of a housing unit, e.g. through online platforms) • Increasing property values and rents → (Residential gentrification/displacement of low income residents and loss of housing units for long-term residents • Conflicts between social and economic agents around who benefits from the visitor economy (e.g. conflicts about wages in the hotel industry, street vending or the ‘tourist tax’) |

| PHYSICAL |

• Overcrowding and resulting problems (e.g. traffic congestion) • Deterioration of public spaces (e.g. through tacky souvenir stores, vandalism, etc.) • Privatisation and/or commodification of public space (e.g. proliferation of cafe terraces or enclosure of tourist sites) and community resources • Disruption of the aesthetic appearance of communities/spread of ‘sameness’ • Environmental pressures (production of waste, litter, increasing water demand ...) • Land-use conflicts (e.g. the use of land for tourism-related activities vs. the use for housing, light manufacturing, etc.) • Over-development, ‘land grabs’, forced evictions and creative-destructive spatial dynamics • Physical manifestations of commercial and residential gentrification (see above) |

| SOCIAL AND SOCIO-CULTURAL |

• Commercialisation, exploitation and distortion of culture (tangible/intangible), heritage and public space • ‘Festivalisation’ and ‘eventification’ • Invasive behaviour of tourists (voyeurism and intrusion)/conflicts arising from different uses of and behaviour in public space (e.g. ‘party tourism’) • Problems of public order (crime, prostitution, ‘uncivil’ behaviour, etc.) • Repressive policies (e.g. anti-homeless laws) • Heightened community divisions (e.g. between tourism beneficiaries and those bearing the burden, between alternative visions of what is heritage) • Loss of diversity/cultural homogenisation (e.g. loss of alternative spaces for artists or sub-cultural scenes) • Changing demographic make-up and tense relations within host communities between long-term residents and ‘outsiders’ (linked with gentrification dynamics) |

| PSYCHOLOGICAL |

• Feelings of alienation, of physical and psychological displacement from familiar places (real or perceived) • Feeling of loss of control over community future • Loss of a sense of belonging or attachment to the community • Feelings of frustration and resentment among local people towards visitors |

Source: Compiled by authors.

The book is structured as follows. Chapters 2 to 6 each offer an overview of the conflicts and social mobilizations surrounding tourism at the scale of an entire city, analysing in a detailed way the rise, and forms, of contention around aspects of urban tourism. In Paris (France), the quintessential tourist city, Gravari-Barbas and Jacquot (Chapter 2) argue that there are no coherent mobilizations against tourism as such, but that existing residents’ associations and other actors have integrated claims about the impacts of the visitor economy in mainstream fights for quality of life, led by (middle-class) residents. They also show that resistance to tourism can take the shape of daily practices (e.g. of mobility in the city) of ‘infra-’ or ‘micropolitics’, as well as of bottom-up tourism approaches developed as alternatives to mainstream tourism.

Novy (Chapter 3) analyses the rise of discontent and protest surrounding the impact of growing tourist numbers in Berlin (Germany) in recent years. Embedded in a discussion of tourism’s trajectory since the city’s reunification and the key tenets of urban development and governance that shaped it, his analysis sheds light on the depoliticization and subsequent repoliticization of tourism as a policy field and posits that tourism-related mobilizations, while not uniform in their messages, are not so much ‘anti-tourist’ as they are critical of the city-state’s approach to tourism development.

Pixová and Sládek (Chapter 4) analyse the forms of citizens’ protest and resistance which have emerged in reaction to the touristification of Prague’s historic core (Czech Republic), and show that they are integrated within broader, and relatively recent, forms of civic engagement and social mobilizations surrounding urban issues in post-socialist Prague. Activists tend to blame the city’s problems on poor governance, management and public policy, not on tourism or tourists as such.

Peters (Chapter 5) analyses the recent conflicts surrounding urban development in Santa Monica (USA), one of California’s premier tourist destinations, where newcomers (in particular skilled workers in the creative sectors) and temporary visitors clash with long-term residents in their visions for the city’s future. Three different vignettes discuss how hotel workers struggle for living wage ordinances and fair treatment in the tourism service industry; how residents fight back against the perceived over-densification of their city; and how the sharp increase in short-term vacation rentals exacerbates the area’s housing affordability crisis and is thus contested.

In Hong Kong, Garrett (Chapter 6) demonstrates that struggles surrounding urban tourism need to be understood against the backdrop of ideological and geopolitical concerns and disputes: the steep rise in mainland Chinese tourists and day trippers have had increasingly visible and contested impacts on Hong kongers’ daily lives and have led to the emergence of anti-Chinese tourism demonstrations. These are part of broader struggles surrounding the relationship between the People’s Republic of China and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, illustrated by the emergence of Hong Kong City State, localist and nativist sentiments.

Chapters 7 to 12 each address one particular sub-theme within the wider struggles surrounding tourism issues outlined above. Opillard (Chapter 7) provides a comparison of current tourism gentrification processes in San Francisco (USA) and Valparaíso (Chile), and of the discontents and forms of protest which they have generated in two very different contexts. San Francisco’s corporate-led touristification and the emergence of new key actors in the tourism industry, such as Airbnb, has fuelled existing gentrification process and intensified the displacement of local residents. This has been contested by housing activist movements which have stepped up their mobilization around the regulation of the so-called ‘sharing economy’. In Valparaíso, the designation of the historic core as a UNESCO World Heritage Site has led to new flows of investment and restructuring of the urban fabric which have triggered the gentrification of some neighbourhoods, contested by long-term residents.

Bereskin (Chapter 8) offers a slightly different take on the central theme of the book and studies the interaction of tourism development, protest and the long-standing ethnonationalist conflict in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Government tourism policies since the mid-1980s have exacerbated the economic, spatial and symbolic exclusion of the communities who have most suffered from the legacy of ‘the Troubles’, but sidelined communities have used tourism as a tool of protest by creating alternative tourism offers to challenge state narratives, cultivate group recognition and secure economic benefits. Tourism has created a new field of interaction between the city’s Catholic and Protestant communities, at times provoking cultural identity contests and competition between the two communities and at other times providing opportunities for intergroup contact and cooperation.

Vianello (Chapter 9) analyses the social mobilizations which have emerged to challenge cruise tourism in one of the world’s cities most heavily threatened by tourism: Venice (Italy). The Committee No Grandi Navi – Laguna Bene Comune (No Big Ships – Lagoon as a Commons) has brought together various social actors (e.g. radical left-wing activists linked with social centres and middle-class environmental campaigners) to actively lobby public authorities for more stringent regulations of the cruise ship traffic in the lagoon, in a challenging political context which has prioritized the growth of cruise tourism (and related investments) at all costs.

Broudehoux (Chapter 10) discusses the emergence of a new form of urban tourism – slum tourism – in the squatter settlements of Rio de Janeiro (Brazil), and shows the multiple forms it has taken in the context of ‘pacification’ programmes for the favelas. She examines the relationship between visitors, residents and intermediary agents in these new forms of tourism, the conflicts and tensions generated, and the critiques and modes of resistance developed by the residents of these informal communities.

Lauermann (Chapter 11) discusses the urban politics of protesting sports ‘mega-events’ like the Olympics, which are used as catalysts for economic growth through a boost of the visitor economy. While mega-events can generate temporary gains in tourism economies and facilitate the pursuit of longer-term urban development goals, the mega-event planning process often bypasses normal processes of democratic deliberation and can introduce a ‘democratic displacement’ in the city. The chapter reviews the role of anti-bid social mobilizations (which contest Olympic projects at the early stages of planning) and their role in disrupting existing models of event-led urban development in the tourist city.

Capanema Alvares et al. (Chapter 12) further discuss the contested politics of mega-events as a tool of urban economic development and tourism policy, by looking at the socially contested and contentious impacts of the large-scale projects developed in a mid-sized Brazilian metropolitan area, Belo Horizonte, in preparation for the 2014 FIFA (Fédération Internationale de Football Association) World Cup and 2016 Summer Olympic Games hosted in Brazil. The huge public investments and stringent policy measures taken to prepare and sanitize urban spaces in Rio and other cities for those mega-events have come under mounting criticisms from a variety of actors. In June 2013, the country was shaken by the largest demonstrations in twenty years, triggered by a brutally repressed protest against the rise in public transport fares in São Paulo. Up to one million protesters took to the streets across the country to protest various issues, among which was the questionable amount of public expenditure spent on mega-event related projects to the detriment of social infrastructure, and the brutal evictions to make way for the construction works accompanying the preparation of those mega-events, as the case of Belo Horizonte illustrates.

Finally, Chapters 13 to 17, which are all characterized by the use of ethnographic approaches and in-depth, in situ observation, offer a series of case studies focusing on particular spaces or neighbourhoods which are used as lenses to address particular issues. Arias-Sans and Russo (Chapter 13) address the tensions between pressures for privatization and demands for commoning in over-used tourist spaces, discussing the contestations surrounding the plan to enclose part of the Park Guëll, a major tourist attraction in Barcelona, Catalonia (Spain). Following the structure of a Greek tragedy, the chapter narrates the different stages of the conflict and unpacks the various arguments at stake between different social actors.

Lederman (Chapter 14) discusses how different categories and classes of local residents grapple with the opportunities presented by the growing visitor economy in San Telmo, a historic neighbourhood of Buenos Aires (Argentina), a country marked by an acute economic crisis in the early 2000s which left many impoverished. Drawing upon extensive observation of a street-based tourist market, he shows how vendors and artisans engage in complex strategies of symbolic ownership of the street by creating multiple linkages to local institutions and appealing to legitimized artistic identities and forms of cultural production. The chapter illustrates how tourism profoundly reflects and reshapes existing forms of social stratification between city residents, as benefits from the lucrative visitor economy are shaped by the hidden mechanisms of social and cultural power and capital.

Arkaraprasertkul (Chapter 15) also uses an ethnographic lens to investigate another type of conflict over the material benefits generated by the growing visitor economy – between the old and the new residents of an increasingly popular traditional lilong neighbourhood in Shanghai (China). Young creative entrepreneurs have settled in the city’s downtown, rundown historic alleyways, building small-scale, often unlicensed businesses such as cafes and design stores which have contributed to the successful transformation of such neighbourhoods into tourist attractions. As a result, tensions have arisen between different categories of residents over the unequal distribution of the benefits from the growing tourism and leisure economy, which has led to a crackdown on such activities by public authorities. The chapter illustrates another form of protest and resistance – one against the implications of the new creative activities, and the visitors they attract, in a historic residential neighbourhood, rather than one of protest against tourism as such.

Luger (Chapter 16), in the case of Singapore, analyses how individual micro-practices of what he terms ‘guerilla tourism’, combined with an emerging social mobilization, have questioned the state-led tourism promotion agenda which has prioritized elite spaces such as the Botanic Gardens – Singapore’s first UNESCO World Heritage Site – over less formal spaces which have important collective memory and environmental value for local residents. He shows how a loose network of grassroots groups have come together to reclaim and stop the destruction of Bukit Brown, the largest Chinese cemetery outside of China. Through the concept of ‘guerilla tourism’, conceptualized as an example of de Certeau’s ‘going off the pathway’, the author shows how alternative (tourism) narratives are performed through the act of transgressing boundaries and walking, contesting and reshaping the hegemony of consumption-led urban development in the authoritarian tourist city.

Fraeser (Chapter 17) shows how forms of social protest and cultural resistance have themselves become, or been packaged as, ‘tourist attractions’. Through the case of the Gängeviertel, a small building complex in the heart of Hamburg (Germany), she shows how a space of resistance can take advantage of its attractiveness for policy-makers and tourists alike, notwithstanding the co-optation and commercialization that this entails and the ambiguous consequences for the nature of the space. The primacy given by the Gängeviertel’s activists to openness to visitors (more than radical autonomy) has turned the quarter into some kind of alternative tourist attraction, attracting both passive consumers and engaged visitors who wish to get involved in the social, cultural and political practices of the Gängeviertel collective and thus become part of its commoning process.

As this book is a first attempt to address the topic, it inevitably has weaknesses and limits. First, beyond the identification of a number of frequent issues and common themes in the present section, we have not developed a fully-fledged analytical framework for a systematic comparison between the cases, which are too disparate for that. Second, some themes which have acquired a lot of political resonance in recent years and are the object of high-profile debates in many locations, would have warranted more detailed analyses, in particular the proliferation of short-term tourism rental practices and the impacts they have on housing markets and neighbourhood change in various cities (hinted at in the case of Paris in Chapter 2, San Francisco in Chapter 7 and Santa Monica in Chapter 5) (Figure 1.5). Third, we have not discussed questions of methodology nor that of the researcher’s positionality in relation to the topic under investigation. As researchers are also tourists (in their free time) or ‘temporary city users’ (when doing field work in urban locations), they too contribute to the processes at play in tourist cities. In some cases, researchers are activists, engaging in collective mobilizations in their city to deal with some of the contentious issues evoked in this book, as individual citizens or as ‘experts’. Fourth, the book barely addresses cases (of which there are plenty) where tourism activities and practices are relatively well integrated into urban space and appear accepted by local residents – or at least are not too contentious. There would be analytical value in studying why this may be the case, and whether this is related to questions of scale and the nature of tourism flows and practices, or of public policy and the regulation of tourism in urban space.

Source: left, Evan Bench; right, Claire Colomb.

We are aware that the book, because of its focus on conflict, protest and resistance, might be perceived as presenting a one-sided and overly negative picture of tourism as a phenomenon and contemporary force of urban change. However, it should not be read as an attack on tourism as such. We are critical of tourism in its current form but do not suggest that tourism is by definition exploitative and destructive. Nor do we subscribe to portrayals of the practices and experiences of being a tourist or traveller (which we all engage in) as being inevitably ‘tragic’ or even ‘vaguely pathetic’ in their character (Harrison 2003: 25). Tourism can – and often does – create numerous benefits for both visitors and host communities. At the same time, however, we recognize that its practice and structures are rooted in unequal power relations and unsustainable development patterns which frequently inhibit any real ability for those being visited to assert control over tourism development, and cause largely negative consequences for the world we occupy (as residents) and travel through (as visitors). For this reason, the developments described and analysed in the present book should be addressed with both further research and action. This includes both a critical questioning and challenging of the way tourism operates and is dealt with in cities’ political arenas, as well as intensified efforts to envision new forms of (state, community and market-led) regulations of the visitor economy and develop alternative forms of tourism. This is particular important as urban tourism flows are unlikely to weaken in the near future. The possibility of supply-side shocks resulting from terrorism, epidemics and natural catastrophes or sharply rising petrol and mobility prices notwithstanding, tourism will most likely not go away anytime soon, which is why more attention is needed to understand – and deal with – its impacts on cities.