The initial production of hydrocarbons from an oil-bearing formation is accomplished by the use of natural reservoir energy. As discussed in Chapter 1, this type of production is termed primary production. Sources of natural reservoir energy that lead to primary production include the swelling of reservoir fluids, the release of solution gas as the reservoir pressure declines, nearby communicating aquifers, and gravity drainage. When the natural reservoir energy has been depleted, it becomes necessary to augment the natural energy from an external source. The Society of Petroleum Engineers has defined the term enhanced oil recovery (EOR) as the following: “one or more of a variety of processes that seek to improve recovery of hydrocarbon from a reservoir after the primary production phase.”1

These EOR techniques have been lumped into two categories—secondary and tertiary recovery processes. It is these processes that provide the additional energy to produce oil from reservoirs in which the primary energy has been depleted.

Typically, the first attempt to supply energy from an external source is accomplished by the injection of an immiscible fluid—either water, referred to as waterflooding, or a natural gas, referred to as gasflooding. The use of this injection scheme is called a secondary recovery operation. Frequently, the main purpose of either a water or a gas injection process is to repressurize the reservoir and then maintain the reservoir at a high pressure. Hence the term pressure maintenance is sometimes used to describe most secondary recovery processes.

Tertiary recovery processes were developed for application in situations where secondary processes had become ineffective. However, the same tertiary processes were also considered for reservoir applications where secondary recovery techniques were not used because of low recovery potential. In the latter case, the name tertiary is a misnomer. For most reservoirs, it is advantageous to begin a secondary or a tertiary process concurrent with primary production. For these applications, the term EOR was introduced.

A process that is not discussed in this text is the use of pumpjacks at the end of primary production. A pumpjack is basically a device used with a downhole pump to help lift oil from the reservoir when the reservoir pressure has been depleted to a point where the oil cannot travel to the surface. Most producing companies will employ this technology, but it is not considered an enhanced oil recovery process.

On the average, primary production methods will produce from a reservoir about 25% to 30% of the initial oil in place. The remaining oil, 70% to 75% of the initial resource, is a large and attractive target for enhanced oil recovery techniques. This chapter will provide an introduction to the main types of EOR techniques that have been used in the industry. Much of the information in this chapter has been taken from an article written by one of the authors and published in the Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology (third edition).2 The information is used with permission from Elsevier.

As mentioned in the previous section, there are in general two types of secondary recovery processes—waterflooding and gasflooding. These will both be discussed in this section. Waterflooding has been the most used process, but gasflooding has proven very useful with reservoirs with a gas cap and where the hydrocarbon formation has a significant dip structure to it.

Waterflooding recovers oil by the water moving through the reservoir as a bank of fluid and “pushing” oil ahead of it. The recovery efficiency of a waterflood is largely a function of the sweep efficiency of the flood and the ratio of the oil and water viscosities. Sweep efficiency, as discussed in Chapter 10, is a measure of how well the water has contacted the available pore space in the oil-bearing zone. Gross heterogeneities in the rock matrix lead to low sweep efficiencies. Fractures, high-permeability streaks, and faults are examples of gross heterogeneities. Homogeneous rock formations provide the optimum setting for high sweep efficiencies. When injected water is much less viscous than the oil it is meant to displace, the water could begin to finger or channel through the reservoir. As discussed in Chapter 10, section 2.3, this fingering or channeling is referred to as viscous fingering and may lead to significant bypassing of residual oil and lower flooding efficiencies. This bypassing of residual oil is an important issue in applying any enhanced oil recovery technique, including waterflooding.

Gas is also used in a secondary recovery process called gasflooding. When gas is the pressure maintenance agent, it is usually injected into a zone of free gas (i.e., a gas cap) to maximize recovery by gravity drainage. The injected gas is usually produced natural gas from the reservoir in question. This, of course, defers the sale of that gas until the secondary operation is completed and the gas can be recovered by depletion. Other gases, such as N2 and CO2, can be injected to maintain reservoir pressure. This allows the natural gas to be sold as it is produced.

The waterflooding process was discovered quite by accident more than 100 years ago when water from a shallow water-bearing horizon leaked around a packer and entered an oil column in a well. The oil production from the well was curtailed, but production from surrounding wells increased. Over the years, the use of waterflooding grew slowly until it became the dominant fluid injection recovery technique. In the following sections, an overview of the process is provided, including information regarding the characteristics of good waterflood candidates and the location of injectors and producers in a waterflood. Ways to estimate the recovery of a waterflood are briefly discussed. The reader is referred to several good references on the subject that provide detailed design criteria.3–7

Several factors lend an oil reservoir to a successful waterflood. They can be generalized in two categories: reservoir characteristics and fluid characteristics.

The main reservoir characteristics that affect a waterflood are depth, structure, homogeneity, and petrophysical properties such as porosity, saturation, and average permeability. The depth of the reservoir affects the waterflood in two ways. First, investment and operating costs generally increase as the depth increases, as a result of the increase in drilling and lifting costs. Second, the reservoir must be deep enough for the injection pressure to be less than the fracture pressure of the reservoir. Otherwise, fractures induced by high water injection rates could lead to poor sweep efficiencies if the injected water channels through the reservoir to the producing wells. If the reservoir has a dipped structure, gravity effects can often be used to increase sweep efficiencies. The homogeneity of a reservoir plays an important role in the effectiveness of a waterflood. The presence of faults, permeability trends, and the like affect the location of new injection wells because good communication is required between injection and production wells. However, if serious channeling exists, as in some reservoirs that are significantly heterogeneous, then much of the reservoir oil will be bypassed and the water injection will be rendered useless. If a reservoir has insufficient porosity and oil saturation, then a waterflood may not be economically justified, on the basis that not enough oil will be produced to offset investment and operating costs. The average reservoir permeability should be high enough to allow sufficient fluid injection without parting or fracturing the reservoir.

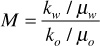

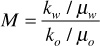

The principal fluid characteristic is the viscosity of the oil compared to that of the injected water. The important variable to consider is actually the mobility ratio, which was defined earlier in Chapter 8 and includes not only the viscosity ratio but also a ratio of the relative permeabilities to each fluid phase:

A good waterflood has a mobility ratio around 1. If the reservoir oil is extremely viscous, then the mobility ratio will likely be much greater than 1, viscous fingering will occur, and the water may bypass much of the oil.

The injection and production wells in a waterflood should be placed to accomplish the following: (1) provide the desired oil productivity and the necessary water injection rate to yield this oil productivity and (2) take advantage of the reservoir characteristics, such as dip, faults, fractures, and permeability trends. In general, two kinds of flooding patterns are used: peripheral flooding and pattern flooding.

Pattern flooding is used in reservoirs having a small dip and a large surface area. Some of the more common patterns are shown in Fig. 11.1. Table 11.1 lists the ratio of producing wells to injection wells in the patterns shown in Fig. 11.1. If the reservoir characteristics yield lower injection rates than those desired, the operator should consider using either a seven- or a nine-spot pattern, where there are more injection wells per pattern than producing wells. A similar argument can be made for using a four-spot pattern in a reservoir with low flow rates in the production wells.

The direct-line drive and staggered-line drive patterns are frequently used because they usually involve the lowest investment. Some of the economic factors to consider include the cost of drilling new wells, the cost of switching existing wells to a different type (i.e., a producer to an injector), and the loss of revenue from the production when making a switch from a producer to an injector.

In peripheral flooding, the injectors are grouped together, unlike in pattern floods where the injectors are interspersed with the producers. Figure 11.2 illustrates two cases in which peripheral floods are sometimes used. In Fig. 11.2(a), a schematic of an anticlinal reservoir with an underlying aquifer is shown. The injectors are placed so that the injected water either enters the aquifer or is near the aquifer-reservoir interface. The pattern of wells on the surface, shown in Fig. 11.2(a), is a ring of injectors surrounding the producers. A monoclinal reservoir with an underlying aquifer is shown in Fig. 11.2(b). In this case, the injectors are again placed so that the injected water either enters the aquifer or enters near the aquifer-reservoir interface. When this is done, the well arrangement shown in Fig. 11.2(b), where all the injectors are grouped together, is obtained.

Figure 11.2 Well arrangements for (a) anticlinal and (b) monoclinal reservoirs with underlying aquifers.

Since the 1990s, other water injections schemes have been used. These include horizontal wells and injection pressures above the reservoir fracturing pressure. The use of these schemes has resulted in mixed success. The reader is encouraged to pursue the literature to research these techniques if further interest is warranted.6–9

Equation (11.1) is an expression for the overall recovery efficiency for any fluid displacement process:

where

E = overall recovery efficiency

Ev = volumetric displacement efficiency

Ed = microscopic displacement efficiency

The volumetric displacement efficiency is made up of the areal displacement efficiency, Es, and the vertical displacement efficiency, Ei. To estimate the overall recovery efficiency, values for Es, Ei, and Ed must be estimated. Methods of estimating these terms are discussed in waterflood textbooks and are too lengthy to present in detail here.3–7 However, some brief, general comments concerning each of the displacement efficiencies can be made.

There are several methods of obtaining estimates for the microscopic displacement efficiency. The basis for one method was presented in section 10.3.1 in Chapter 10. The areal displacement, or sweep, efficiency is largely a function of pattern type and mobility ratio. The vertical displacement efficiency is primarily a function of reservoir heterogeneities and thickness of the reservoir formation.

Waterflooding is an important process for the reservoir engineer to understand. A successful waterflood in a typical reservoir results in oil recoveries increasing from 25% after primary recovery to 30% to 33% overall. It has made and will continue to make large contributions to the recovery of reservoir oil.

Gasflooding was introduced in Chapter 5, sections 5.6 and 5.7, where the injection of an immiscible gas was discussed in retrograde gas reservoirs. Gas is frequently injected in these types of reservoirs to maintain the pressure at a level above the point at which liquid will begin to condense in the reservoir.10,11 This is done because of the value of the liquid and the potential to produce the liquid on the surface. Reservoir gas is also pushed to the producing wells by the injected gas, similar to oil being pushed by a waterflood, as discussed in the previous section.

A second type of gasflooding is that shown in Fig. 11.3. A dry gas is injected into the gas cap of a saturated oil reservoir. This is done to maintain reservoir pressure and also for the gas cap to push down on the oil-bearing formation. Thus oil is pushed to the producing wells. Obviously, the producing wells should be perforated in the liquid zone so that the production of oil will be maximized.

Steeply dipping reservoirs may yield high sweep efficiencies and high oil recoveries. A concern in gasflooding in more horizontal structures is the viscosity ratio of the gas to oil. Since a gas is typically much less viscous than oil, viscous fingering of the gas phase through the oil phase may occur, resulting in poor sweep efficiencies and low oil recoveries. Often in horizontal reservoirs, to help with the poor sweep efficiencies, water is injected after an amount of gas injection. The water is followed by more gas. This process is referred to as the water alternating gas injection process, or WAG. Christensen et al. have shown the effectiveness of this process in several applications.12

As discussed in Chapter 5, N2 and CO2 have been used in gasflooding projects. With the increased desire to sequester CO2, the injection of CO2 has developed into a viable option as a secondary recovery process.13–15

Tertiary oil recovery refers to the process of producing liquid hydrocarbons by methods other than the conventional use of reservoir energy (primary recovery) and secondary recovery schemes discussed in the last section. In this text, tertiary oil recovery processes will be classified into three categories: (1) miscible flooding processes, (2) chemical flooding processes, and (3) thermal flooding processes. The category of miscible displacement includes single-contact and multiple-contact miscible processes. Chemical processes are polymer, micellar polymer, alkaline flooding, and microbial flooding. Thermal processes include hot water, steam cycling, steam drive, and in situ combustion. In general, thermal processes are applicable in reservoirs containing heavy crude oils, whereas chemical and miscible displacement processes are used in reservoirs containing light crude oils. The next few sections provide an introduction to these processes. If interested, the reader is again referred to several good references on the subject that provide detailed design criteria.6,7,16–20

During the early stages of a waterflood in a water-wet reservoir system, the brine exists as a film around the sand grains, and the oil fills the remaining pore space. At an intermediate time during the flood, the oil saturation has been decreased and exists partly as a continuous phase in some pore channels but as discontinuous droplets in other channels. At the end of the flood, when the oil has been reduced to residual oil saturation, Sor, the oil exists primarily as a discontinuous phase of droplets or globules that have been isolated and trapped by the displacing brine.

The waterflooding of oil in an oil-wet system yields a different fluid distribution at Sor. Early in the waterflood, the brine forms continuous flow paths through the center portions of some of the pore channels. The brine enters more and more of the pore channels as the waterflood progresses. At residual oil saturation, the brine has entered a sufficient number of pore channels to shut off the oil flow. The residual oil exists as a film around the sand grains. In the smaller flow channels, this film may occupy the entire void space.

The mobilization of the residual oil saturation in a water-wet system requires that the discontinuous globules be connected to form a continuous flow channel that leads to a producing well. In an oil-wet porous medium, the film of oil around the sand grains must be displaced to large pore channels and be connected in a continuous phase before it can be mobilized. The mobilization of oil is governed by the viscous forces (pressure gradients) and the interfacial tension forces that exist in the sand grain–oil–water system.

There have been several investigations of the effect of viscous forces and interfacial tension forces on the trapping and mobilization of residual oil.4–7,17,21,22 From these studies, correlations between a dimensionless parameter called the capillary number, Nvc, and fraction of oil recovered have been developed. The capillary number is the ratio of the viscous force to the interfacial tension force and is defined by Eq. (11.2).

where υ is velocity, μw is the viscosity of the displacing fluid, σow is the interfacial tension between the displaced and displacing fluids, ko is the effective permeability to the displaced phase, φ is the porosity, and Δp/L is the pressure drop associated with the velocity.

Figure 11.4 is a schematic representation of the capillary number correlation in which the capillary number is plotted on the abscissa, and the ratio of residual oil saturation (value after conducting a tertiary recovery process to the value before the tertiary recovery process) is plotted as the vertical coordinate. The capillary number increases as the viscous force increases or as the interfacial tension force decreases.

The correlation suggests that a capillary number greater than 10–5 for the mobilization of unconnected oil droplets is necessary. The capillary number increases as the viscous force increases or as the interfacial tension force decreases. The tertiary methods that have been developed and applied to reservoir situations are designed either to increase the viscous force associated with the injected fluid or to decrease the interfacial tension force between the injected fluid and the reservoir oil. The next sections discuss the four general types of tertiary processes: miscible flooding, chemical flooding, thermal flooding, and microbial flooding.

In Chapter 10, it was noted that the microscopic displacement efficiency is largely a function of interfacial forces acting between the oil, rock, and displacing fluid. If the interfacial tension between the trapped oil and displacing fluid could be lowered to 10–2 to 10–3 dynes/cm, the oil droplets could be deformed and squeeze through the pore constrictions. A miscible process is one in which the interfacial tension is zero—that is, the displacing fluid and residual oil mix to form one phase. If the interfacial tension is zero, then the capillary number NVC becomes infinite and the microscopic displacement efficiency is maximized.

Figure 11.5 is a schematic of a miscible process. Fluid A is injected into the formation and mixes with the crude oil, forming an oil bank. A mixing zone develops between fluid A and the oil bank and will grow due to dispersion. Fluid A is followed by fluid B, which is miscible with fluid A but not generally miscible with the oil and which is much cheaper than fluid A. A mixing zone will also be created at the fluid A–fluid B interface. It is important that the amount of fluid A that is injected be large enough that the two mixing zones do not come in contact. If the front of the fluid A–fluid B mixing zone reaches the rear of the fluid A oil mixing zone, viscous fingering of fluid B through the oil could occur. On the other hand, the volume of fluid A must be kept small to avoid large injected-chemical costs.

Consider a miscible process with n-decane as the residual oil, propane as fluid A, and methane as fluid B. The system pressure and temperature are 2000 psia and 100°F, respectively. At these conditions, both n-decane and propane are liquids and are therefore miscible in all proportions. The system temperature and pressure indicate that any mixture of methane and propane would be in the gas state; therefore, the methane and propane would be miscible in all proportions. However, the methane and n-decane would not be miscible for similar reasons. If the pressure were reduced to 1000 psia and the temperature held constant, the propane and n-decane would again be miscible. However, mixtures of methane and propane could be located in a two-phase region and would not lend themselves to a miscible displacement. Note that, in this example, the propane appears to act as a liquid when in the presence of n-decane and as a gas when in contact with methane. It is this unique capacity of propane and other intermediate range hydrocarbons that leads to the miscible process.

There are, in general, two types of miscible processes. The first type is referred to as the single-contact miscible process and involves such injection fluids as liquefied petroleum gases (LPG) and alcohols. The injected fluids are miscible with residual oil immediately on contact. The second type is the multiple-contact, or dynamic, miscible process. The injected fluids in this case are usually methane, inert fluids, or an enriched methane gas supplemented with a C2-C6 fraction; this fraction of alkanes has the unique ability to behave like a liquid or a gas at many reservoir conditions. The injected fluid and oil are usually not miscible on first contact but rely on a process of chemical exchange of the intermediate hydrocarbons between phases to achieve miscibility. These processes are discussed in great detail in other texts.16–20,23

The phase behavior of hydrocarbon systems can be described through the use of ternary diagrams such as Fig. 11.6. Crude oil phase behavior can typically be represented reasonably well by three fractions of the crude. One fraction is methane (C1). A second fraction is a mixture of ethane through hexane (C2-C6). The third fraction is the remaining hydrocarbon species lumped together and called C7+.

Figure 11.6 Ternary diagram illustrating typical hydrocarbon phase behavior at constant temperature and pressure.

Figure 11.6 illustrates the ternary phase diagram for a typical hydrocarbon system with these three pseudocomponents at the corners of the triangle. There are one-phase and two-phase regions (enclosed within the curved line V0-C-L0) in the diagram. The one-phase region may be vapor or liquid (to the left of the dashed line through the critical point, C) or gas (to the right of the dashed line through the critical point). A gas could be mixed with either a liquid or a vapor in appropriate percentages and yield a miscible system. However, when liquid is mixed with a vapor, often the result is a composition in the two-phase region. A mixing process is represented on a ternary diagram as a straight line. For example, if compositions V and G are mixed in appropriate proportions, the resulting mixture would fall on the line VG. If compositions V and L are mixed, the resulting overall composition M would fall on the line VL but the mixture would yield two phases since the resulting mixture would fall within the two-phase region. If two phases are formed, their compositions, V1 and L1, would be given by a tie line extended through the point M to the phase envelope. The part of the phase boundary on the phase envelope from the critical point C to point V0 is the dew-point curve. The phase boundary from C to L0 is the bubble-point curve. The entire bubble point–dew point curve is referred to as the binodal curve.

The oil–LPG–dry gas system will be used to illustrate the behavior of the first-contact miscible process on a ternary diagram. Figure 11.7 is a ternary diagram with the points O, P, and V representing the oil, LPG, and dry gas, respectively. The oil and LPG are miscible in all proportions. A mixing zone at the oil-LPG interface will grow as the front advances through the reservoir. At the rear of the LPG slug, the dry gas and LPG are miscible, and a mixing zone will also be created at this interface. If the dry gas–LPG mixing zone overtakes the LPG–oil mixing zone, miscibility will be maintained, unless the contact of the two zones yields mixtures inside the two-phase region (see Fig. 11.7, line M0M1).

Reservoir pressures sufficient to achieve miscibility are required. This limits the application of LPG processes to reservoirs having pressures at least of the order of 1500 psia. Reservoirs with pressures less than this might be amenable to alcohol flooding, another first-contact miscible process, since alcohols tend to be soluble with both oil and water (the drive fluid in this case). The two main problems with alcohols are that they are expensive and they become diluted with connate water during a flooding process, which reduces the miscibility with the oil. Alcohols that have been considered are in the C1-C4 range.

Multiple-contact or dynamic miscible processes do not require the oil and displacing fluid to be miscible immediately on contact but rely on chemical exchange between the two phases for miscibility to be achieved. Figure 11.8 illustrates the high-pressure (lean-gas) vaporizing, or the dry gas miscible process.

The temperature and pressure are constant throughout the diagram at reservoir conditions. A vapor denoted by V in Fig. 11.8, consisting mainly of methane and a small percentage of intermediates, will serve as the injection fluid. The oil composition is given by the point O. The following sequence of steps occurs in the development of miscibility:

1. The injection fluid V comes in contact with crude oil O. They mix, and the resulting overall composition is given by M1. Since M1 is located in the two-phase region, a liquid phase L1 and a vapor phase V1 will form with the compositions given by the intersections of a tie line through M1, with the bubble-point and dew-point curves, respectively.

2. The liquid L1 has been created from the original oil O by the vaporizing of some of the light components. Since the oil O was at its residual saturation and was immobile due to the relative permeability, Kro, being zero, when a portion of the oil is extracted, the volume, and hence the saturation, will decrease and the oil will remain immobile. The vapor phase, since Krg is greater than zero, will move away from the oil and be displaced downstream.

3. The vapor V1 will come in contact with fresh crude oil O, and again the mixing process will occur. The overall composition will yield two phases, V2 and L2. The liquid again remains immobile and the vapor moves downstream, where it comes in contact with more fresh crude.

4. The process is repeated with the vapor-phase composition moving along the dew-point curve, V1-V2-V3, and so on, until the critical point, C, is reached. At this point, the process becomes miscible. In the real case, because of reservoir and fluid property heterogeneities and dispersion, there may be a breaking down and a reestablishment of miscibility.

Behind the miscible front, the vapor-phase composition continually changes along the dew-point curve. This leads to partial condensing of the vapor phase with the resulting condensate being immobile, but the amount of liquid formed will be quite small. The liquid phase, behind the miscible front, continually changes in composition along the bubble point. When all of the extractable components have been removed from the liquid, a small amount of liquid will be left, which will remain immobile. There will be these two quantities of liquid that will remain immobile and not be recovered by the miscible process. In practice, operators have reported that the vapor front travels anywhere from 20 ft to 40 ft from the wellbore before miscibility is achieved.

The high-pressure vaporizing process requires a crude oil with significant percentages of intermediate compounds. It is these intermediates that are vaporized and combined with the injection fluid to form a vapor that will eventually be miscible with the crude oil. This requirement of intermediates means that the oil composition must lie to the right of a tie line extended through the critical point on the binodal curve (see Fig. 11.8). A composition lying to the left, such as denoted by point A, will not contain sufficient intermediates for miscibility to develop. This is due to the fact that the richest vapor in intermediates that can be formed will be on a tie line extended through point A. Clearly, this vapor will not be miscible with crude oil A.

As pressure is reduced, the two-phase region increases. It is desirable, of course, to keep the two-phase region minimal in size. As a rule, pressures of the order of 3000 psia or greater and an oil with an API gravity greater than 35 are required for miscibility in the high-pressure vaporizing process.

The enriched gas-condensing process is a second type of dynamic miscible process (Fig. 11.9). As in the high-pressure vaporizing process, where chemical exchange of intermediates is required for miscibility, miscibility is developed during a process of exchange of intermediates with the injection fluid and the residual oil. In this case, however, the intermediates are condensed from the injection fluid to yield a “new” oil, which becomes miscible with the “old” oil and the injected fluid. The following steps occur in the process (the sequence of steps is similar to those described for the high-pressure vaporizing process but contain some significant differences):

1. An injection fluid G rich in intermediates mixes with residual oil O.

2. The mixture, given by the overall composition M1, separates into a vapor phase, V1, and a liquid phase, L1.

3. The vapor moves ahead of the liquid that remains immobile. The remaining liquid, L1, is then contacted by fresh injection fluid, G. Another equilibrium occurs, and phases having compositions V2 and L2 are formed.

4. The process is repeated until a liquid is formed from one of the equilibration steps that is miscible with G. Miscibility is then said to have been achieved.

Ahead of the miscible front, the oil continually changes in composition along the bubble-point curve. In contrast to the high-pressure vaporizing process, there is the potential for no residual oil to be left behind in the reservoir as long as there is a sufficient amount of G injected to supply the condensing intermediates. The enriched gas process may be applied to reservoirs containing crude oils with only small quantities of intermediates. Reservoir pressures are usually in the range of 2000 psia to 3000 psia.

The intermediates are expensive, and so usually a dry gas is injected after a sufficient volume of enriched gas has been injected.

The use of inert gases, in particular CO2 and N2, as injected fluids in miscible processes, has become extremely popular. The representation of the process with CO2 or N2 on the ternary diagram is exactly the same as the high-pressure vaporizing process, with the exception that either CO2 or N2 becomes a component and methane is lumped with the intermediates. Typically the one-phase region is largest for CO2, with N2 and dry gas having about the same one-phase size. The larger the one-phase region, the more readily miscibility will be achieved. Miscibility pressures are lower for CO2, usually in the neighborhood of 1200 psia to 1500 psia, whereas N2 and dry gas yield much higher miscibility pressures (i.e., 3000 psia or more).

The capacity of CO2 to vaporize hydrocarbons is much greater than that of natural gas. It has been shown that CO2 vaporizes hydrocarbons primarily in the gasoline and gas-oil range. This capacity of CO2 to extract hydrocarbons is the primary reason for the use of CO2 as an oil recovery agent. It is also the reason CO2 requires lower miscibility pressures than natural gas. The presence of other diluent gases such as N2, methane, or flue gas with the CO2 will raise the miscibility pressure. The multiple-contact mechanism works nearly the same with a diluent gas added to the CO2 as it does for pure CO2. Frequently, an application of the CO2 process in the field will tolerate higher miscibility pressures than what pure CO2 would require. If this is the case, the operator can dilute the CO2 with other available gas, raising the miscibility pressure but also reducing the CO2 requirements. Due to the recent consideration to sequester CO2 because of its contributions to greenhouse gases, companies may find it very desirable to use CO2 as a flooding agent.

The pressure at which miscibility is achieved is best determined by conducting a series of displacement experiments in a long, slim tube. A plot of oil recovery versus flooding pressure is made, and the minimum miscibility pressure is determined from the plot.

Because of differences in density and viscosity between the injected fluid and the reservoir fluid(s), the miscible process often suffers from poor mobility. Viscous fingering and gravity override frequently occur. The simultaneous injection of a miscible agent and brine may take advantage of the high microscopic displacement efficiency of the miscible process and the high macroscopic displacement efficiency of a waterflood. However, the improvement may not be as good as hoped for since the miscible agent and brine may separate due to density differences, with the miscible agent flowing along the top of the porous medium and the brine along the bottom. Several other variations of the simultaneous injection scheme may be attempted. These typically involve the injection of a miscible agent followed by brine or the altering of miscible agent-brine injection. The latter variation has been named the WAG process (discussed earlier) and has become the most popular. A balance between amounts of injected water and gas has to be achieved. Too much gas will lead to viscous fingering and gravity override of the gas, whereas too much water could lead to the trapping of reservoir oil by the water. The addition of foam generating substances to the brine phase may aid in reducing the mobility of the gas phase.

Operational problems involving miscible processes include transportation of the miscible flooding agent, corrosion of equipment and tubing, and separation and recycling of the miscible flooding agent.

Chemical flooding processes involve the addition of one or more chemical compounds to an injected fluid either to reduce the interfacial tension between the reservoir oil and injected fluid or to improve the sweep efficiency of the injected fluid by making it more viscous, thereby improving the mobility ratio. Both mechanisms are designed to increase the capillary number.

Three general methods are typically included in chemical flooding technology. The first is polymer flooding, in which a large macromolecule is used to increase the displacing fluid viscosity. This process leads to improved sweep efficiency in the reservoir of the injected fluid. The remaining two methods, micellar-polymer flooding and alkaline flooding, make use of chemicals that reduce the interfacial tension between oil and a displacing fluid. This text will include a fourth method—microbial flooding.

The addition of large molecular weight molecules called polymers to an injected water can often increase the effectiveness of a conventional waterflood. Polymers are usually added to the water in concentrations ranging from 250 to 2000 parts per million (ppm). A polymer solution is more viscous than brine without polymer. In a flooding application, the increased viscosity will alter the mobility ratio between the injected fluid and the reservoir oil. The improved mobility ratio will lead to better vertical and areal sweep efficiencies and thus higher oil recoveries. Polymers have also been used to alter gross permeability variations in some reservoirs. In this application, polymers form a gel-like material by cross-linking with other chemical species. The polymer gel sets up in large permeability streaks and diverts the flow of any injected fluid to a different location.

Two general types of polymers have been used. These are synthetically produced polyacrylamides and biologically produced polysaccharides. Polyacrylamides are long molecules with a small effective diameter. Thus they are susceptible to mechanical shear. High rates of flow through valves will sometimes break the polymer into smaller entities and reduce the viscosity of the solution. A reduction in viscosity can also occur as the polymer solution tries to squeeze through the pore openings on the sand face of the injection well. A carefully designed injection scheme is necessary. Polyacrylamides are also sensitive to salt. Large salt concentrations (i.e., greater than 1–2 wt%) tend to make the polymer molecules curl up and lose their viscosity-building effect.

Polysaccharides are less susceptible to both mechanical shear and salt. Since they are produced biologically, care must be taken to prevent biological degradation in the reservoir. As a rule, polysaccharides are more expensive than polyacrylamides.

Polymer flooding has not been successful in high-temperature reservoirs. Neither polymer type has exhibited sufficiently long-term stability above 160°F in moderate-salinity or heavy-salinity brines.

Polymer flooding has the best application in moderately heterogeneous reservoirs and reservoirs containing oils with viscosities less than 100 centipoise (cp). Polymer projects may find some success in reservoirs having widely differing properties—that is, permeabilities ranging from 20–2000 millidarcies (md), in situ oil viscosities of up to 100 cp, and reservoir temperatures of up to 200°F.

Since the use of polymers does not affect the microscopic displacement efficiency, the improvement in oil recovery will be due to improved sweep efficiency over what is obtained during a conventional waterflood. Typical oil recoveries from polymer flooding applications are in the range of 1% to 5% of the initial oil in place. Operators are more likely to have a successful polymer flood if they start the process early in the producing life of the reservoir.

The basic micellar-polymer process uses a surfactant to lower the interfacial tension between the injected fluid and the reservoir oil. A surfactant is a surface-active agent that contains a hydrophobic (“dislikes” water) part to the molecule and a hydrophilic (“likes” water) part. The surfactant migrates to the interface between the oil and water phases and helps make the two phases more miscible. Interfacial tensions can be reduced from ~30 dynes/cm, found in typical waterflooding applications, to 10–4 dynes/cm, with the addition of as little as 0.1 wt% to 5.0 wt% surfactant to water-oil systems. Soaps and detergents used in the cleaning industry are surfactants. The same principles involved in washing soiled linen or greasy hands are used in “washing” residual oil off rock formations. As the interfacial tension between an oil phase and a water phase is reduced, the capacity of the aqueous phase to displace the trapped oil phase from the pores of the rock matrix increases. The reduction of interfacial tension results in a shifting of the relative permeability curves so that the oil will flow more readily at lower oil saturations.

When surfactants are mixed above a critical saturation in a water-oil system, the result is a stable mixture called a micellar solution. The micellar solution is made up of structures called microemulsions, which are homogeneous, transparent, and stable to phase separation. They can exist in several shapes, depending on the concentrations of surfactant, oil, water, and other constituents. Spherical microemulsions have typical size ranges from 10–6 to 10–4 mm. A microemulsion consists of external and internal phases sandwiched around one or more layers of surfactant molecules. The external phase can be either aqueous or hydrocarbon in nature, as can the internal phase.

Solutions of microemulsions are known by several other names, including surfactant solutions, soluble oils, and micellar solutions. Figure 11.5 can be used to represent the micellar-polymer process. A certain volume of the micellar or surfactant solution, fluid A, is injected into the reservoir. The surfactant solution is then followed by a polymer solution, fluid B, to provide a mobility buffer between the surfactant solution and the drive water, which is used to push the entire system through the reservoir. The polymer solution is designed to prevent viscous fingering of the drive water through the surfactant solution as it starts to build up an oil bank ahead of it. As the surfactant solution moves through the reservoir, surfactant molecules are retained on the rock surface due to the process of adsorption. Often a preflush is injected ahead of the surfactant to precondition the reservoir and reduce the loss of surfactants to adsorption. This preflush contains sacrificial agents such as sodium tripolyphosphate.

There are, in general, two types of micellar-polymer processes. The first uses a low-concentration surfactant solution (less than 2.5 wt%) but a large injected volume (up to 50% pore volume). The second involves a high-concentration surfactant solution (5 wt% to 12 wt%) and a small injected volume (5% to 15% pore volume). Either type of process has the potential of achieving low interfacial tensions with a wide variety of brine crude oil systems.

Whether the low-concentration or the high-concentration system is selected, the system is made up of several components. The multicomponent facet leads to an optimization problem, since many different combinations could be chosen. Because of this, a detailed laboratory screening procedure is usually undertaken. The screening procedure typically involves three types of tests: (1) phase behavior studies, (2) interfacial tension studies, and (3) oil displacement studies.

Phase behavior studies are typically conducted in small (up to 100 ml) vials in order to determine what type, if any, of microemulsion is formed with a given micellar-crude oil system. The salinity of the micellar solution is usually varied around the salt concentration of the field brine where the process will be applied. Besides the microemulsion type, other factors examined could be oil uptake into the microemulsion, ease with which the oil and aqueous phases mix, viscosity of the microemulsion, and phase stability of the microemulsion.

Interfacial tension studies are conducted with various concentrations of micellar solution components to determine optimal concentration ranges. Measurements are usually made with the spinning drop, pendent drop, or the sessile drop techniques.

The oil displacement studies are the final step in the screening procedure. They are usually conducted in two or more types of porous media. Often initial screening experiments are conducted in unconsolidated sand packs and then in Berea sandstone. The last step in the sequence is to conduct the oil displacement experiments in actual cored samples of reservoir rock. Frequently, actual core samples are placed end to end in order to obtain a core of reasonable length, since the individual core samples are typically only 5–7 in. long.

If the oil recoveries from the oil displacement tests warrant further study of the process, the next step is usually a small field pilot study involving anywhere from 1 to 10 acres.

The micellar-polymer process has been applied in several projects. The results have not been very encouraging. The process has demonstrated that it can be a technical success, but the economics of the process has been either marginal or poor in nearly every application.19,20 As the price of oil increases, the micellar-polymer process will become more attractive.

When an alkaline solution is mixed with certain crude oils, surfactant molecules are formed. When the formation of surfactant molecules occurs in situ, the interfacial tension between the brine and oil phases could be reduced. The reduction of interfacial tension causes the microscopic displacement efficiency to increase, thereby increasing oil recovery.

Alkaline substances that have been used include sodium hydroxide, sodium orthosilicate, sodium metasilicate, sodium carbonate, ammonia, and ammonium hydroxide. Sodium hydroxide has been the most popular. Sodium orthosilicate has some advantages in brines with a high divalent ion content.

There are optimum concentrations of alkaline and salt and optimum pH, where the interfacial tension values experience a minimum. Finding these requires a screening procedure similar to the one discussed previously for the micellar-polymer process. When the interfacial tension is lowered to a point where the capillary number is greater than 10–5, oil can be mobilized and displaced.

Several mechanisms have been identified that aid oil recovery in the alkaline process. These include the following: lowering of interfacial tension, emulsification of oil, and wettability changes in the rock formation. All three mechanisms can affect the microscopic displacement efficiency, and emulsification can also affect the macroscopic displacement efficiency. If a wettability change is desired, a high (2.0–5.0 wt%) concentration of alkaline should be used. Otherwise, concentrations of the order of 0.5–2.0 wt% of alkaline are used.

The emulsification mechanism has been suggested to work by either of two methods. The first is by forming an emulsion, which becomes mobile and later trapped in downstream pores. The emulsion “blocks” the pores, which thereby diverts flow and increases the sweep efficiency. The second mechanism is by again forming an emulsion, which becomes mobile and carries oil droplets that it has entrained to downstream production sites.

The wettability changes that sometimes occur with the use of alkaline affect relative permeability characteristics, which in turn affect mobility and sweep efficiencies.

Mobility control is an important consideration in the alkaline process, as it is in all tertiary processes. Often, it is necessary to include polymer in the alkaline solution in order to reduce the tendency of viscous fingering to take place.

Not all crude oils are amenable to alkaline flooding. The surfactant molecules are formed with the heavier, acidic components of the crude oil. Tests have been designed to determine the susceptibility of a given crude oil to alkaline flooding. One of these tests involves titrating the oil with potassium hydroxide (KOH). An acid number is found by determining the number of milligrams of KOH required to neutralize 1 g of oil. The higher the acid number, the more reactive the oil will be and the more readily it will form surfactants. An acid number larger than ~0.2 mg KOH suggests potential for alkaline flooding.

In general, alkaline projects have been inexpensive to conduct, but recoveries have not been large in the past field pilots.19–20

Microbial enhanced oil recovery (MEOR) flooding involves the injection of microorganisms that react with reservoir fluids to assist in the production of residual oil. The US National Institute for Petroleum and Energy Research (NIPER) maintains a database of field projects that have used microbial technology. There has been significant research conducted on MEOR, but few pilot projects have been conducted. The Oil and Gas Journal’s 2012 survey reported no ongoing projects in the United States related to this technology.24 However, researchers in China have reported mild success with MEOR.25

There are two general types of MEOR processes—those in which microorganisms react with reservoir fluids to generate surfactants or those in which microorganisms react with reservoir fluids to generate polymers. Both processes are discussed here, along with a few concluding comments regarding the problems with applying them. The success of MEOR processes will be highly dependent on reservoir characteristics. MEOR systems can be designed for reservoirs that have either a high or low degree of channeling. Therefore, MEOR applications require a thorough knowledge of the reservoir. Mineral content of the reservoir brine will also affect the growth of microorganisms.

Microorganisms can be reacted with reservoir fluids to generate either surfactants or polymers in the reservoir. Once either the surfactant or polymer has been produced, the processes of mobilizing and recovering residual oil become similar to those discussed with regard to chemical flooding.

Most pilot projects have involved an application of the huff and puff or thermal-cycling process discussed with regard to thermal flooding. A solution of microorganisms is injected along with a nutrient—usually molasses. When the solution of microorganisms has been designed to react with the oil to form polymers, the injected solution will enter high-permeability zones and react to form the polymers that will then act as a permeability reducing agent. When oil is produced during the huff stage, oil from lower permeability zones will be produced. Conversely, the solution of microorganisms can be designed to react with the residual crude oil to form a surfactant. The surfactant lowers the interfacial tension of the brine-water system, which thereby mobilizes the residual oil. The oil is then produced in the huff part of the process.

The reaction of the microorganisms with the reservoir fluids may also produce gases, such as CO2, N2, H2, and CH4. The production of these gases will result in an increase in reservoir pressure, which will thereby enhance the reservoir energy.

Since microorganisms can be reacted to form either polymers or surfactants, a knowledge of the reservoir characteristics is critical. If the reservoir is fairly heterogeneous, then it is desirable to generate polymers in situ, which could be used to divert fluid flow from high- to low-permeability channels. If the reservoir has low injectivity, then using microorganisms that produced polymers could be very damaging to the flow of fluids near the wellbore. Hence a thorough knowledge of the reservoir characteristics, particularly those immediately around the wellbore, is extremely important.

Reservoir brines could inhibit the growth of the microorganisms. Therefore, some simple compatibility tests could result in useful information as to the viability of the process. These can be simple test-tube experiments in which reservoir fluids and/or rock are placed in microorganism-nutrient solutions and growth and metabolite production of the microorganisms are monitored.

MEOR processes have been applied in reservoir brines up to less than 100,000 ppm, rock permeabilities greater than 75 md, and depths less than 6800 ft. This depth corresponds to a temperature of about 75°C. Most MEOR projects have been performed with light crude oils having API gravities between 30 and 40. These should be considered “rule of thumb” criteria. The most important consideration in selecting a microorganism-reservoir system is to conduct compatibility tests to make sure that microorganism growth can be achieved.

The main technical problems associated with chemical processes include the following: (1) screening of chemicals to optimize the microscopic displacement efficiency, (2) contacting the oil in the reservoir, and (3) maintaining good mobility in order to lessen the effects of viscous fingering. The requirements for the screening of chemicals vary with the type of process. Obviously, as the number of components increases, the more complicated the screening procedure becomes. The chemicals must also be able to tolerate the environment in which they are placed. High temperature and salinity may limit the chemicals that could be used.

The major problem experienced in the field to date in chemical flooding processes has been the inability to contact residual oil. Laboratory screening procedures have developed micellar-polymer systems that have displacement efficiencies approaching 100% when sand packs or uniform consolidated sandstones are used as the porous medium. When the same micellar-polymer system is applied in an actual reservoir rock sample, however, the efficiencies are usually lowered significantly. This is due to the heterogeneities in the reservoir samples. When the process is applied to the reservoir, the efficiencies become even worse. Research needs to be conducted on methods to reduce the effect of the rock heterogeneities and to improve the displacement efficiencies.

Mobility research is also being conducted to improve displacement sweep efficiencies. If good mobility is not maintained, the displacing fluid front will not be effective in contacting residual oil.

Operational problems involve treating the water used to make up the chemical systems, mixing the chemicals to maintain proper chemical compositions, plugging the formation with particular chemicals such as polymers, dealing with the consumption of chemicals due to adsorption and mechanical shear and other processing steps, and creating emulsions in the production facilities. Research to address these operational problems is ongoing. Despite these problems, chemical flooding can be effective in the right reservoir conditions and in a favorable economic environment.

Primary and secondary production from reservoirs containing heavy, low-gravity crude oils is usually a very small fraction of the initial oil in place. This is due to the fact that these types of oils are very thick and viscous and, as a result, do not migrate readily to producing wells. Figure 11.10 shows a typical relationship between the viscosity of several heavy, viscous crude oils and temperature.

As can be seen, viscosities decrease by orders of magnitude for certain crude oils, with an increase in temperature of 100°F to 200°F. This suggests that, if the temperature of a crude oil in the reservoir can be raised by 100°F to 200°F over the normal reservoir temperature, the oil viscosity will be reduced significantly and will flow much more easily to a producing well. The temperature of a reservoir can be raised by injecting a hot fluid or by generating thermal energy in situ by combusting the oil. Hot water or steam can be injected as the hot fluid. Three types of processes will be discussed in this section: steam cycling, steam drive, and in situ combustion. In addition to the lowering of the crude oil viscosity, there are other mechanisms by which these three processes recover oil. These mechanisms will also be discussed.

Most of the oil that has been produced by tertiary methods to date has been a result of thermal processes. There is a practical reason for this, as well as several technical reasons. In order to produce more than 1% to 2% of the initial oil in place from a heavy-oil reservoir, thermal methods have to be employed. As a result, thermal methods were investigated much earlier than either miscible or chemical methods, and the resulting technology was developed much more rapidly.26,27

The steam-cycling, or stimulation, process was discovered by accident in the Mene Grande Tar Sands, Venezuela, in 1959. During a steam-injection trial, it was decided to relieve the pressure from the injection well by backflowing the well. When this was done, a very high oil production rate was observed. Since this discovery, many fields have been placed on steam cycling.

The steam-cycling process, also known as the steam huff and puff, steam soak, or cyclic steam injection, begins with the injection of 5000 bbl to 15,000 bbl of high-quality steam. This could take a period of days to weeks to accomplish. The well is then shut in, and the steam is allowed to soak the area around the injection well. This soak period is fairly short, usually from 1 to 5 days. The injection well is then placed on production. The length of the production period is dictated by the oil production rate but could last from several months to a year or more. The cycle is repeated as many times as is economically feasible. The oil production will decrease with each new cycle.

Mechanisms of oil recovery due to this process include (1) reduction of flow resistance near the wellbore by reducing the crude oil viscosity and (2) enhancement of the solution gas drive mechanism by decreasing the gas solubility in an oil as temperature increases.

Often, in heavy-oil reservoirs, the steam stimulation process is applied to develop injectivity around an injection well. Once injectivity has been established, the steam stimulation process is converted to a continuous steam-drive process.

The oil recoveries obtained from steam stimulation processes are much smaller than the oil recoveries that could be obtained from a steam drive. However, it should be apparent that the steam stimulation process is much less expensive to operate. The cyclic steam stimulation process is the most common thermal recovery technique.19,20,24 Recoveries of additional oil have ranged from 0.21 bbl to 5.0 bbl of oil per barrel of steam injected.

The steam-drive process is much like a conventional waterflood. Once a pattern arrangement is established, steam is injected into several injection wells while the oil is produced from other wells. This is different from the steam stimulation process, whereby the oil is produced from the same well into which the steam is injected. As the steam is injected into the formation, the thermal energy is used to heat the reservoir oil. Unfortunately, some of the energy also heats up the entire environment, such as formation rock and water, and is lost. Some energy is also lost to the underburden and overburden. Once the oil viscosity is reduced by the increased temperature, the oil can flow more readily to the producing wells. The steam moves through the reservoir and comes in contact with cold oil, rock, and water. As the steam contacts the cold environment, it condenses, and a hot water bank is formed. This hot water bank acts as a waterflood and pushes additional oil to the producing wells.

Several mechanisms have been identified that are responsible for the production of oil from a steam drive. These include thermal expansion of the crude oil, viscosity reduction of the crude oil, changes in surface forces as the reservoir temperature increases, and steam distillation of the lighter portions of the crude oil.

Most steam applications have been limited to shallow reservoirs because, as the steam is injected, it loses heat energy in the wellbore. If the well is very deep, all the steam will be converted to liquid water.

Steam drives have been applied in many pilot and field-scale projects with very good success. Oil recoveries have ranged from 0.3 bbl to 0.6 bbl of oil per barrel of steam injected. A process that was developed in the 1970s and has become increasingly popular is the steam assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) process. This process involves the drilling of two horizontal wells (see Fig. 11.11) a few meters apart. Steam is injected in the top well and heavy oil, as it heats up from the steam, drains into the bottom well. The process works best in reservoirs with high vertical permeability and has received much attention by companies with heavy-oil resources. There have been many applications of this process in Canada and Venezuela.19,20,24

Figure 11.11 Schematic of the steam assisted gravity drainage process (courtesy Canadian Centre for Energy Information).

Early attempts at in situ combustion involved what is referred to as the forward dry combustion process. The crude oil was ignited downhole, and then a stream of air or oxygen-enriched air was injected in the well where the combustion was originated. The flame front was then propagated through the reservoir. Large portions of heat energy were lost to the overburden and underburden with this process. To reduce the heat losses, a reverse combustion process was designed. In reverse combustion, the oil is ignited as in forward combustion but the air stream is injected in a different well. The air is then “pushed” through the flame front as the flame front moves in the opposite direction. The process was found to work in the laboratory, but when it was tried in the field on a pilot scale, it was never successful. It was found that the flame would be shut off because there was no oxygen supply and that, where the oxygen was being injected, the oil would self-ignite. The whole process would then revert to a forward combustion process.

When the reverse combustion process failed, a new technique called the forward wet combustion process was introduced. This process begins as a forward dry combustion does, but once the flame front has been established, the oxygen stream is replaced by water. As the water comes in contact with the hot zone left by the combustion front, it flashes to steam, using energy that otherwise would have been wasted. The steam moves through the reservoir and aids the displacement of oil. The wet combustion process has become the primary method of conducting combustion projects.

Not all crude oils are amenable to the combustion process. For the combustion process to function properly, the crude oil has to have enough heavy components to serve as the source of fuel for the combustion. Usually this requires an oil of low API gravity. As the heavy components in the oil are combusted, lighter components as well as flue gases are formed. These gases are produced with the oil and raise the effective API gravity of the produced oil.

The number of in situ combustion projects has decreased since the 1980s. Environmental and other operational problems have proved to be excessively burdensome to some operators.26–27

The main technical problems associated with thermal techniques are poor sweep efficiencies, loss of heat energy to unproductive zones underground, and poor injectivity of steam or air. Poor sweep efficiencies are due to the density differences between the injected fluids and the reservoir crude oils. The lighter steam or air tends to rise to the top of the formation and bypass large portions of crude oil. Data have been reported from field projects in which coring operations have found significant differences in residual oil saturations in the top and bottom parts of the swept formation. Research needs to be conducted on methods of reducing the tendency for the injected fluids to override the reservoir oil. Techniques involving foams are being employed.

Large heat losses continue to be associated with thermal processes. The wet combustion process has lowered these losses for the higher temperature combustion techniques, but the losses are severe enough in many applications to prohibit the combustion process. The losses are not as large with the steam processes because they typically involve lower temperatures. The development of a feasible downhole generator will significantly reduce the losses associated with steam-injection processes.

The poor injectivity found in thermal processes is largely a result of the nature of the reservoir crude oils. Operators have applied fracture technology in connection with the injection of fluids in thermal processes. This has helped in many reservoirs.

Operational problems include the following: the formation of emulsions, the corrosion of injection and production tubing and facilities, and adverse effects on the environment. When emulsions are formed with heavy crude oil, they are very difficult to break. Operators need to be prepared for this. In the high-temperature environments created in the combustion processes and when water and stack gases mix in the production wells and facilities, corrosion becomes a serious problem. Special well liners are often required. Stack gases also pose environmental concerns in both steam and combustion applications. Stack gases are formed when steam is generated by either coal- or oil-fired generators and, of course, during the combustion process as the crude is burned.

A large number of variables are associated with a given oil reservoir—for instance, pressure and temperature, crude oil type and viscosity, and the nature of the rock matrix and connate water. Because of these variables, not every type of tertiary process can be applied to every reservoir. An initial screening procedure would quickly eliminate some tertiary processes from consideration in particular reservoir applications. This screening procedure involves the analysis of both crude oil and reservoir properties. This section presents screening criteria for each of the general types of processes previously discussed in this chapter, except microbial flooding. (A discussion of MEOR screening criteria appears in section 11.3.5.3.) It should be recognized that these are only guidelines. If a particular reservoir-crude oil application appears to be on a borderline between two different processes, it may be necessary to consider both processes. Once the number of processes has been reduced to one or two, a detailed economic analysis should then be conducted.

Some general considerations can be discussed before the individual process screening criteria are presented. First, detailed geological study is usually desirable, since operators have found that unexpected reservoir heterogeneities have led to the failure of many tertiary field projects. Reservoirs that were found to be highly faulted or fractured typically yield poor recoveries from tertiary processes. Second, some general comments pertaining to economics can also be made. When an operator is considering tertiary oil recovery in particular applications, candidate reservoirs should contain sufficient recoverable oil and be large enough for the project to be potentially profitable. Also, deep reservoirs could involve large drilling and completion expenses if new wells are to be drilled.

Table 11.2 contains the screening criteria that have been compiled from the literature for the miscible, chemical, and thermal techniques.

The miscible process requirements are characterized by a low-viscosity crude oil and a thin reservoir. A low-viscosity oil will usually contain enough of the intermediate-range components for the multicontact miscible process to be established. The requirement of a thin reservoir reduces the possibility that gravity override will occur and yields a more even sweep efficiency.

In general, the chemical processes require reservoir temperatures of less than 200°F, a sandstone reservoir, and enough permeability to allow sufficient injectivity. The chemical processes will work on oils that are more viscous than what the miscible processes require, but the oils cannot be so viscous that adverse mobility ratios are encountered. Limitations are set on temperature and rock type so that chemical consumption can be controlled to reasonable values. High temperatures will degrade most of the chemicals that are currently being used in the industry.

In applying the thermal methods, it is critical to have a large oil saturation. This is especially pertinent to the steamflooding process, because some of the produced oil will be used on the surface as the source of fuel to fire the steam generators. In the combustion process, crude oil is used as fuel to compress the airstream on the surface. The reservoir should be of significant thickness in order to minimize heat loss to the surroundings.

The recovery of nearly 70% to 75% of all the oil that has been discovered to date is an attractive target for EOR processes. The application of EOR technology to existing fields could significantly increase the world’s proven reserves. Several technical improvements will have to be made, however, before tertiary processes are widely implemented. The economic climate will also have to be positive because many of the processes are either marginally economical or not economical at all. Steamflooding and polymer processes are currently economically viable. In comparison, the CO2 process is more costly but growing more and more popular. The micellar-polymer process is even more expensive.

In a recent report, the US Department of Energy stated that nearly 40% of all EOR oil produced in the United States was due to thermal processes.28 Most of the rest is from gas injection processes, either gasflooding or the miscible flooding processes. Chemical flooding, although highly researched in the 1980s, is not contributing much, mostly due to the costs associated with the processes.28

EOR technology should be considered early in the producing life of a reservoir. Many of the processes depend on the establishment of an oil bank in order for the process to be successful. When oil saturations are high, the oil bank is easier to form. It is crucial for engineers to understand the potential of EOR and the way EOR can be applied to a particular reservoir.

As discussed at the end of the previous chapter, an important tool that the engineer should use to help identify the potential for an enhanced oil recovery process, either secondary or tertiary, is computer modeling or reservoir simulation. The reader is referred to the literature if further information is needed.29–33

11.1 Conduct a brief literature review to identify recent applications of enhanced oil recovery. Of the tertiary recovery processes discussed in the chapter, are there processes that are receiving more attention than others? Why?

11.2 Review the most recent Oil and Gas Journal survey of enhanced oil recovery projects. Are there countries that are more active than others in regards to EOR projects? Why?

11.3 How are the world’s oil reserves affected by the price of oil?

11.4 How has the continued development of techniques such as fracking and horizontal drilling affected the implementation of EOR projects?

1. Society of Petroleum Engineers E&P Glossary, Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2009.

2. R. E. Terry, “Enhanced Oil Recovery,” Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology, 3rd ed., Academic Press, 2003, 503–18.

3. C. R. Smith, Mechanics of Secondary Oil Recovery, Robert E. Krieger Publishing, 1966.

4. G. P. Willhite, Waterflooding, Vol. 3, Society of Petroleum Engineers, 1986.

5. F. F. Craig, The Reservoir Engineering Aspects of Waterflooding, Society of Petroleum Engineers, 1993.

6. L. W. Lake, ed., Petroleum Engineering Handbook, Vol. 5, Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2007.

7. T. Ahmed, Reservoir Engineering Handbook, 4th ed., Gulf Publishing Co., 2010.

8. J. J. Taber and R. S. Seright, “Horizontal Injection and Production Wells for EOR or Waterflooding,” presented before the SPE conference, Mar. 18–20, 1992, Midland, TX.

9. M. Algharaib and R. Gharbi, “The Performance of Water Floods with Horizontal and Multilateral Wells,” Petroleum Science and Technology (2007), 25, No. 8.

10. Penn State Earth and Mineral Sciences Energy Institute, “Gas Flooding Joint Industry Project,” http://www2011.energy.psu.edu/gf

11. N. Ezekwe, Petroleum Reservoir Engineering Practice, Pearson Education, 2011.

12. J. R. Christensen, E. H. Stenby, and A. Skauge, “Review of WAG Field Experience,” SPEREE (Apr. 2001), 97–106.

13. S. Kokal and A. Al-Kaabi, Enhanced Oil Recovery: Challenges and Opportunities, World Petroleum Council, 2010.

14. G. Mortis, “Special Report: EOR/Heavy Oil Survey: CO2 Miscible, Steam Dominate Enhanced Oil Recovery Processes,” Oil and Gas Jour. (Apr. 2010), 36–53.

15. P. DiPietro, P. Balash, and M. Wallace, “A Note on Sources of CO2 Supply for Enhanced-Oil-Recovery Operations,” SPE Economics and Management (Apr. 2012).

16. H. K. van Poollen and Associates, Enhanced Oil Recovery, PennWell Publishing, 1980.

17. D. W. Green and G. P. Willhite, Enhanced Oil Recovery, Vol. 6, Society of Petroleum Engineers, 1998.

18. L. W. Lake, Enhanced Oil Recovery, Prentice Hall, 1989 (reprinted in 2010).

19. J. Sheng, Modern Chemical Enhanced Oil Recovery, Gulf Professional Publishing, 2011.

20. V. Alvarado and E. Manrique, Enhanced Oil Recovery: Field Planning, and Development Strategies, Gulf Professional Publishing, 2010.

21. J. J. Taber, “Dynamic and Static Forces Required to Remove a Discontinuous Oil Phase from Porous Media Containing Both Oil and Water,” Soc. Pet. Engr. Jour. (Mar. 1969), 3.

22. G. L. Stegemeier, “Mechanisms of Entrapment and Mobilization of Oil in Porous Media,” Improved Oil Recovery by Surfactant and Polymer Flooding, ed. D. O. Shah and R. S. Schechter, Academic Press, 1977.

23. F. I. Stalkup Jr., Miscible Displacement, Society of Petroleum Engineers, 1983.

24. L. Koottungal, “2012 Worldwide EOR Survey,” Oil and Gas Jour. (Apr. 2, 2012), 41–55.

25. Q. Li, C. Kang, H. Wang, C. Liu, and C. Zhang, “Application of Microbial Enhanced Oil Recovery Technique to Daqing Oilfield,” Biochemical Engineering Jour. (2002), 11, 197–99.

26. M. Prats, Thermal Recovery, Society of Petroleum Engineers, 1982.

27. T. C. Boberg, Thermal Methods of Oil Recovery, John Wiley and Sons, 1988.

28. US Office of Fossil Energy, “Enhanced Oil Recovery,” http://energy.gov/fe/science-innovation/oil-gas/enhanced-oil-recovery

29. J. J. Lawrence, G. F. Teletzke, J. M. Hutfliz, and J. R. Wilkinson, “Reservoir Simulation of Gas Injection Processes,” paper SPE 81459, presented at the SPE 13th Middle East Oil Show and Conference, Apr. 5–8, 2003, Bahrain.

30. T. Ertekin, J. H. Abou-Kassem, and G. R. King, Basic Applied Reservoir Simulation, Vol. 10, Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2001.

31. J. Fanchi, Principles of Applied Reservoir Simulation, 3rd ed., Elsevier, 2006.

32. C. C. Mattax and R. L. Dalton, Reservoir Simulation, Vol. 13, Society of Petroleum Engineers, 1990.

33. M. Carlson, Practical Reservoir Simulation, PennWell Publishing, 2006.