One of the most important job functions of the reservoir engineer is the prediction of future production rates from a given reservoir or specific well. Over the years, engineers have developed several methods to accomplish this task. The methods range from simple decline-curve analysis techniques to sophisticated multidimensional, multiflow reservoir simulators.1–7 Whether a simple or complex method is used, the general approach taken to predict production rates is to calculate producing rates for a period for which the engineer already has production information. If the calculated rates match the actual rates, the calculation is assumed to be correct and can then be used to make future predictions. If the calculated rates do not match the existing production data, some of the process parameters are modified and the calculation repeated. The process of modifying these parameters to match the calculated rates with the actual observed rates is referred to as history matching.

The calculational method, along with the necessary data used to conduct the history match, is often referred to as a mathematical model or simulator. When decline-curve analysis is used as the calculational method, the engineer is doing little more than curve fitting, and the only data that are necessary are the existing production data. However, when the calculational technique involves multidimensional mass and energy balance equations and multiflow equations, a large amount of data is required, along with a computer to conduct the calculations. With this complex model, the reservoir is usually divided into a grid. This allows the engineer to use varying input data, such as porosity, permeability, and saturation, in different grid blocks. This often requires estimating much of the data, since the engineer usually knows data only at specific coring sites that occur much less frequently than the grid blocks used in the calculational procedure.

History matching covers a wide variety of methods, ranging in complexity from a simple decline-curve analysis to a complex multidimensional, multiflow simulator. This chapter will begin with a discussion of the least complex model—that of simple decline-curve analysis. This will provide a starting point for a more advanced model that uses the zero-dimensional Schilthuis material balance equation, discussed in earlier chapters.

Decline-curve analysis is a fairly straightforward method of predicting the future production of a well, using only the production history of that well. This type of analysis has a long tradition in the oil industry and remains one of the most common tools for forecasting oil and gas production.8–13 In general, there are two approaches to decline-curve analysis: (1) curve fitting the production data using one of three models developed by Arps8 and (2) type-curve matching using techniques developed by Fetkovich.10 This chapter will present a brief introduction to the approach developed by Arps.

In Chapter 8, the notions of the transient time and pseudosteady-state time periods were discussed. The reader will recall that the transient time during the production life of a well refers to the time before the effects of the outer boundary has been felt by the producing fluid. The pseudosteady-state time period refers to the time that the effects of the outer boundary have been felt and that the reservoir pressure is dropping at a uniform rate throughout the drainage volume of the well. Theoretically, the approach by Arps requires that the producing well be in the pseudosteady-state time period both for the production period in which the engineer is attempting to model and for the future projected production life that the engineer is attempting to predict. Arps predicted that the production decline from a well would model one of three curves (exponential, hyperbolic, or harmonic decline) and could be represented by the following equation:

where

q = flow rate at time t

t = time

b = empirical constant derived from production data

d = Arps’s decline-curve exponent (exponential, d = 0; hyperbolic, 0 < d < 1; harmonic, d = 1)

Example 12.1 illustrates decline-curve analysis by considering the production from a well and assuming that the production data fit an exponential curve. The following steps are performed:

1. The production history of a given well is obtained and plotted against time.

2. An exponential line of the form q = qi* exp (–b*t) is fit to the data.

3. The equation is extrapolated to determine future production of the well.

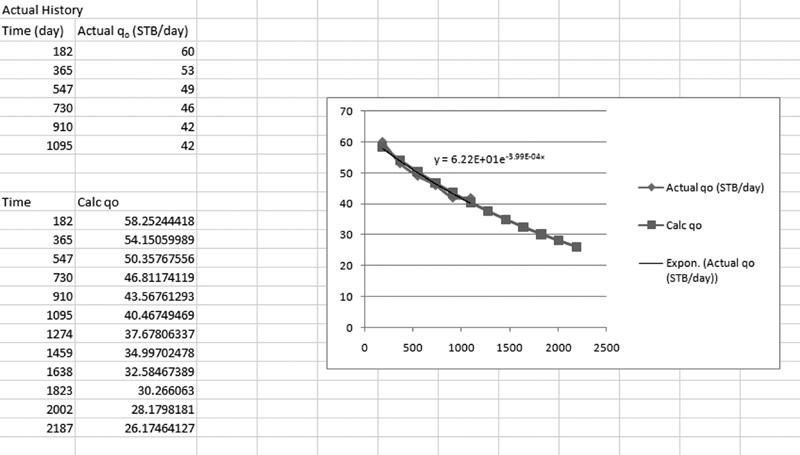

Example 12.1 Determining the Production Forecast for Well 15-1 Using the Production History Shown in Fig. 12.1

Given

See the production history shown in Fig. 12.1.

Solution

Using Microsoft Excel, estimate the production and time from Fig. 12.1. Plot them in Excel and fit an exponential trend line to the data. Create a new table, adding values for time in excess of the production history, and calculate values for the flow rate based on the equation given by the trend line. Plot these values next to the actual data.

The reader can see the simplicity of decline-curve analysis in the solution of this problem. However, the engineer, in using this technique to predict future hydrocarbon recoveries, needs to be aware of the assumptions built into the approach—the main one being that the drainage area of the well will continue to perform as it had during the time that the history is attempting to be matched. Engineers, while continuing to use simple decline-curve analysis, are becoming increasingly aware that sophisticated models using mass and energy balance equations and computer modeling techniques are much more reliable when predicting reservoir performance.

The material balance equations presented in Chapters 3 to 7 and Chapter 10 do not yield information on future production rates because the equations do not have a time dimension associated with them. These equations simply relate average reservoir pressure to cumulative production. To obtain rate information, a method is needed whereby time can be related to either the average reservoir pressure or cumulative production. In Chapter 8, single-phase flow in porous media was discussed and equations were developed for several situations that related flow rate to average reservoir pressure. It should be possible, then, to combine the material balance equations of Chapters 3 to 7 and 10 with the flow equations from Chapter 8 in a model or simulator that would provide a relationship for flow rates as a function of time. The model will require accurate fluid and rock property data and past production data. Once a model has been tested for a particular well or reservoir system and found to reproduce actual past production data, it can be used to predict future production rates. The importance of the data used in the model cannot be overemphasized. If the data are correct, the prediction of production rates will be fairly accurate.

The problem considered in this chapter involves a volumetric, internal gas-drive reservoir. In Chapter 10, several different methods to calculate the oil recovery as a function of reservoir pressure for this type of reservoir were presented. For the example in this chapter, the Schilthuis method is used. The reader will remember that the Schilthuis method requires permeability ratio versus saturation information and the solution of Eqs. (10.33), (10.40), and (10.41), written with the two-phase formation volume factor:

The procedure mentioned in the previous section yields oil and gas production as a function of the average reservoir pressure, but it does not give any indication of the time required to produce the oil and gas. To calculate the time and rate at which the oil and gas are produced, a flow equation is needed. It was found in Chapter 8 that most wells reach the pseudosteady state after flowing for a few hours to a few days. An assumption will be made that the well used in the history match described in this chapter has been produced for a time long enough for the pseudosteady-state flow to be reached. For this case, Eq. (8.45) can be used to describe the oil flow rate into the wellbore:

This equation assumes pseudosteady-state, radial geometry for an incompressible fluid. The subscript, o, refers to oil, and the average reservoir pressure,  , is the pressure used to determine the production, Np, in the Schilthuis material balance equation. The incremental time required to produce an increment of oil for a given pressure drop is found by simply dividing the incremental oil recovery by the rate computed from Eq. (8.45) at the corresponding average pressure:

, is the pressure used to determine the production, Np, in the Schilthuis material balance equation. The incremental time required to produce an increment of oil for a given pressure drop is found by simply dividing the incremental oil recovery by the rate computed from Eq. (8.45) at the corresponding average pressure:

The total time that corresponds to a particular average reservoir pressure can be determined by summing the incremental times for each of the incremental pressure drops until the average reservoir pressure of interest is reached.

Since Eq. (12.2) requires ΔNp and the Schilthuis equation determines ΔNp/N, N, the initial oil in place, must be estimated. In Chapter 6, section 6.3, it was shown that the initial oil in place could be estimated from the volumetric approach by the use of the following equation:

Combining these equations with the solution of the Schilthuis material balance equation yields the necessary production rates of both oil and gas.

The reservoir model developed in the previous two sections will now be applied to history-matching production data from a well in a volumetric, internal gas-drive reservoir. Actual oil production and instantaneous gas-oil ratios for the first 3 years of the life of the well are plotted in Fig. 12.1. The data for the problem were obtained from personnel at the University of Kansas and are used here by permission.14

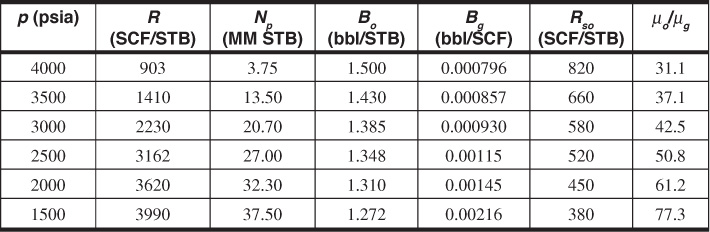

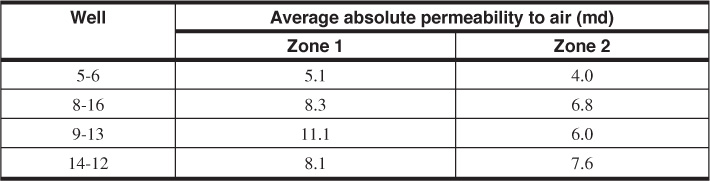

The well is located in a reservoir that is sandstone and produced from two zones, separated by a thin shale section, approximately 1 ft to 2 ft in thickness. The reservoir is classified as a stratigraphic trap. The two producing zones decrease in thickness and permeability in directions where it is believed that a pinch-out occurs. Permeability and porosity decrease to unproductive limits both above and below the producing formation. The initial reservoir pressure was 620 psia. The average porosity and initial water saturation values were 21.5% and 37%, respectively. The area drained by the well is 40 ac. Average thicknesses and absolute permeabilities were reported to be 17 ft and 9.6 md for zone 1 and 14 ft and 7.2 md for zone 2. Laboratory data for fluid viscosities, formation volume factors, solution gas-oil ratio, oil relative permeability, and the gas-to-oil permeability ratio are plotted in Figs. 12.2 to 12.6.

Table 12.1 Excel Functions Used to Calculate Fluid Property Data for the Schilthuis History-Matching Problem

Table 12.2 Excel Functions Used to Calculate Oil Relative Permeability Curve in the Schilthuis History-Matching Problem

One of the first steps in attempting to perform the history match is to convert the fluid property data provided in Figs. 12.2 to 12.4 to a more usable form. This is done by simply regressing the data to create Excel functions in Microsoft Excel’s Visual Basic Editor for each parameter—for example, oil and gas viscosity as a function of pressure. The resulting functions can be found in the program listing in Table 12.1. The two permeability relationships also need to be regressed for use in the example.

Both the relative permeability to oil and the permeability ratio can be expressed as functions of gas saturation. These Excel functions are structured in a different manner from the fluid property equations. The constants for the regressed equations are placed in an array, shown in Tables 12.2 and 12.3, and a regression is performed between each set of points. These relationships are handled this way to facilitate modifications to the equations used in the program if necessary.

Table 12.3 Excel Functions Used to Calculate Gas to Oil Permeability Ratio Curve in the Schilthuis History-Matching Problem

With the data of Figs. 12.2 to 12.6 expressed in equation format, the history match is now ready to be executed. An example of the Excel worksheet is shown in Table 12.4.

The Excel sheet is laid out with the reservoir variables such as initial pressure, wellhead flowing pressure, reservoir area, and so on shown at the top of the page. Directly below are the zone-specific data of height, initial hydrocarbon in place, and permeability. Those values are totaled to provide a value for the entire well. Below are the reservoir properties at each average well pressure in 10-psi increments. To the right are the actual production values for the wells, and a comparison between actual and calculated is shown in the graph in the bottom corner. The equations for each of the cells are shown in Table 12.5.

The sheet requires a user-specified delNpguess value in order to determine the reservoir properties at a given pressure. Once those values are determined, the sheet automatically calculates a new delNp and an Np for that pressure. The delNpguess will need to be iterated until it is equal to delNp. To aid in this, the check column was created. At the end of the check column is a cell with the sum of the check values. Using Excel’s built-in solver tool, that cell can be iteratively solved for a minimum value by adjusting the delNpguess for each pressure increment. This allows the user to rapidly solve the set of equations in the Schilthuis balance and get the result at that set of conditions.

When the program is executed using the original data given in the problem statement as input, the oil production rate and R, or instantaneous GOR, values obtained result in the plots shown in Fig. 12.7. Notice that the calculated oil production rates, shown in Fig. 12.7(a), begin higher than the actual rates and decrease faster with time or with a greater slope. The calculated instantaneous GOR values are compared with the actual GOR values in Fig. 12.7(b) and found to be much lower than the actual values.

At this point, it is necessary to ask how the calculated instantaneous GOR values could be raised in order for them to match the actual values. An examination of Eq. (10.33) suggests that R is a function of fluid property data and the ratio of gas-to-oil permeabilities. To calculate higher values for R, either the fluid property data or the permeability ratio data must be modified. Because fluid property data are readily and accurately obtained and the permeabilities could change significantly in the reservoir owing to different rock environments, it seems justified to modify the permeability ratio data. It is often the case when conducting a history match that an engineer will find differences between laboratory-measured permeability ratios and field-measured permeability ratios. Mueller, Warren, and West showed that one of the main reasons for the discrepancy between laboratory kg/ko values and field-measured values can be explained by the unequal stages of depletion in the reservoir.15 For the same reason, field instantaneous GOR values seldom show the slight decline predicted in the early stages of depletion and, conversely, usually show a rise in gas-oil ratio at an earlier stage of depletion than the prediction. Whereas the theoretical predictions assume a negligible (actually zero) pressure drawdown, so that the saturations are therefore uniform throughout the reservoir, actual well pressure drawdowns will deplete the reservoir in the vicinity of the wellbore in advance of areas further removed. In development programs, some wells are often completed years before other wells, and depletion is naturally further advanced in the area of the older wells, which will have gas-oil ratios considerably higher than the newer wells. And even when all wells are completed within a short period, when the formation thickness varies and all wells produce at the same rate, the reservoir will be depleted faster when the formation is thinner. Finally, when the reservoir comprises two or more strata of different specific permeabilities, even if their relative permeability characteristics are the same, the strata with higher permeabilities will be depleted before those with lower permeabilities. Since all these effects are minimized in high-capacity formations, closer agreement between field and laboratory data can be expected for higher capacity formations. On the other hand, high-capacity formations tend to favor gravity segregation. When gravity segregation occurs and advantage is taken of it by shutting in the high-ratio wells or working over wells to reduce their ratios, the field-measured kg/ko values will be lower than the laboratory values. Thus the laboratory kg/ko values may apply at every point in a reservoir without gravity segregation, and yet the field kg/ko values will be higher owing to the unequal depletion of the various portions of the reservoir.

The following procedure is used to generate new permeability ratio values from the actual production data:

1. Plot the actual R values versus time and determine a relationship between R and time.

2. Choose a pressure and determine the fluid property data at that pressure. From the chosen pressure and the output data in Table 12.4, find the time that corresponds with the chosen pressure.

3. From the relationship found in step 1, calculate R for the time found in step 2.

4. With the value of R found in step 3 and the fluid property data found in step 2, rearrange Eq. (10.33) and calculate a value of the permeability ratio.

5. From the pressure chosen in step 2 and from the Np values calculated from the chosen pressure, calculate the value of the gas saturation that corresponds with the calculated value of the permeability ratio.

6. Repeat steps 2 through 5 for several pressures. The result will be a new permeability ratio–gas saturation relationship.

In Excel, the solution resembles Table 12.6.

The reader should realize that in steps 2 and 5 the original permeability ratio was used to generate the data of Table 12.4. This suggests that the new permeability ratio–gas saturation relationship could be in error because it is based on the data of Table 12.4 and that, to have a more correct relationship, it might be necessary to repeat the procedure. The quality of the history match obtained with the new permeability ratio values will dictate whether this iterative procedure should be used in generating the new permeability ratio–gas saturation relationship. The new permeability ratios determined from the previous six-step procedure are plotted with the original permeability ratios in Fig. 12.8.

It is now necessary to regress the new permeability ratio–gas saturation relationship and input the new data into the Excel worksheet before the calculation can be executed again to obtain a new history match. When this is done, the calculation yields the results plotted in Fig. 12.9.

The new permeability ratio data has significantly improved the match of the instantaneous GOR values, as can be seen in Figure 12.9(b). However, the oil production rates are still not a good match. In fact, the new permeability ratio data have yielded a steeper slope for the calculated oil rates, as shown in Figure 12.9(a), than what is observed in Figure 12.7(a) from the original data. A look at the calculation scheme helps explain the effect of the new permeability ratio data.

Because the new values of instantaneous GOR were calculated with the new permeability ratio data, which in turn were determined by using Eq. (10.33) and the actual GOR values, it should be expected that the calculated GOR values would match the actual GOR values. The flow rate calculation, which involves Eq. (8.45), does not use the permeability ratio, so the magnitude of the flow rates would not be expected to be affected by the new permeability ratio data. However, the time calculation does involve Np, which is a function of the permeability ratio in the Schilthuis material balance calculation. Therefore, the rate at which the flow rates decline will be altered with the new permeability ratio data.

To obtain a more accurate match of oil production rates, it is necessary to modify additional data. This raises the question, what other data can be justifiably changed? It was argued that it was not justifiable to modify the fluid property data. However, the fluid property data and/or equations should be carefully checked for possible errors. In this case, the equations were checked by calculating values of Bo, Bg, Rso, μo, and μg at several pressures and comparing them with the original data. The fluid property equations were found to be correct and accurate. Other assumed reservoir properties that could be in error include the zone thicknesses and absolute permeabilities. The thicknesses are determined from logging and coring operations from which an isopach map is created. Absolute permeabilities are measured from a small sample of a core taken from a limited number of locations in the reservoir. The number of coring locations is limited largely because of the costs involved in performing the coring operations. Although the actual measurement of both the thickness and permeability from coring material is highly accurate, errors are introduced when one tries to extrapolate the measured information to the entire drainage area of a particular well. For instance, when constructing the isopach map for the zone thickness, you need to make assumptions regarding the continuity of the zone in between coring locations. These assumptions may or may not be correct. Because of the possible errors introduced in determining average values for the thickness and permeability for the well-drainage area, varying these parameters and observing the effect of our history match is justified. In the remainder of this section, the effect of changing these parameters on the history-matching process is examined. Table 12.7 contains a summary of the cases that are discussed.

In case 3, the thicknesses of both zones were adjusted to determine the effect on the history match. Since the calculated flow rates are higher than the actual flow rates, the thicknesses were reduced. Figure 12.10 shows the effect on oil producing rate and instantaneous GOR when the thicknesses are reduced by about 20%.

By reducing the thicknesses, the calculated oil production rates are shifted downward, as shown in Figure 12.10(a).

This yields a good match with the early data but not with the later data, because the calculated values decline at a much more rapid rate than the actual data. The calculated instantaneous GOR values still closely match the actual GOR values. These observations can be supported by noting that the zone thickness enters into the calculation scheme in two places. One is in the calculation for N, the initial oil in place, which is performed by using Eq. (12.3). Then N is multiplied by each of the ΔNp/N values determined in the Schilthuis balance. The second place the thickness is used is in the flow equation, Eq. (8.45), which is used to calculate qo. The instantaneous GOR values are not affected because neither the calculation for N nor the calculation for qo is used in the calculation for instantaneous GOR or R. However, the oil flow rate is directly proportional to the thickness, so as the thickness is reduced, the flow rate is also reduced. At first glance, it appears that the decline rate of the flow rate would be altered. But upon further study, it is found that although the flow rate is obviously a function of the thickness, the time is not. To calculate the time, an incremental ΔNp is divided by the flow rate corresponding with that incremental production. Since both Np and qo are directly proportional to the thickness, the thickness cancels out, thereby making the time independent of the thickness. In summary, the net result of reducing the thickness is as follows: (1) the magnitude of the oil flow rate is reduced, (2) the slopes of the oil production and instantaneous GOR curves are not altered, and (3) the instantaneous GOR values are not altered.

To determine the effect on the history match of varying the absolute permeabilities, the permeabilities were reduced by about 20% in case 4. Figure 12.11 shows the oil production rates and the instantaneous GOR plots for this new case. The quality of the match of oil production rates has improved, but the quality of the match of the instantaneous GOR values has decreased. Again, if the equations involved are examined, an understanding of how changing the absolute permeabilities has affected the history match can be obtained.

Figure 12.10 History match of case 3. Case 3 used the new permeability ratio data and reduced zone thicknesses.

Figure 12.11 History match of case 4. Case 4 used the new permeability ratio data and reduced absolute permeabilities.

Equation (8.45) suggests that the oil flow rate is directly proportional to the effective permeability to oil, ko:

Equation (12.4) shows the relationship between the effective permeability to oil and the absolute permeability, k. Combining Eqs. (8.45) and (12.4), it can be seen that the oil flow rate is directly proportional to the absolute permeability. Therefore, when the absolute permeability is reduced, the oil flow rate is also reduced. Since the time values are a function of qo, the time values are also affected. The magnitude of the instantaneous GOR values is not a function of the absolute permeability, since neither the effective nor the absolute permeabilities are used in the Schilthuis material balance calculation. However, the time values are modified, so the slope of both the oil production rate and the instantaneous GOR curves are altered. This is exactly what should happen in order to obtain a better history match of the oil production values. However, although it has improved the oil production history match, the instantaneous GOR match has been made worse. By reducing the absolute permeabilities, it has been found that (1) the magnitude of the oil flow rates are reduced, (2) the magnitude of the instantaneous GOR values are not changed, and (3) the slopes of both the oil production and instantaneous GOR curves are altered.

By modifying the zone thicknesses and absolute permeabilities, the magnitude of the oil flow rates and the slope of the oil flow rate curve can be modified. Also, while adjusting the oil flow rate, slight changes in the slope of the instantaneous GOR curve are obtained. In case 5, both the zone thickness and the absolute permeability are changed in addition to using the new permeability ratio data. Figure 12.12 contains the history match for case 5. As can be seen in Figure 12.12(a), the calculated oil flow rates are an excellent match to the actual field oil production values. The match of instantaneous GOR values has worsened from cases 2 to 4 but is still much improved over the match in case 1, which was obtained by using the original permeability ratio data.

Figure 12.12 History match of case 5. Case 5 used the new permeability ratio data and modified zone thicknesses and absolute permeabilities.

A second iteration of the permeability ratio values may be necessary, depending on the quality of the final history match that is obtained. This is because the procedure used to obtain the new permeability ratio data involves using the old permeability ratio data. The calculated instantaneous GOR values do not match the actual field GOR values very well, so a second iteration of the permeability ratio values is warranted. Following the procedure of obtaining new permeability ratio data in conjunction with the results of case 5, a second set of new permeability ratios is obtained. This second set is plotted in Figure 12.13, along with the original data and the first set used in cases 2 to 5.

By using the permeability ratio data from the second iteration and by adjusting the zone thicknesses and absolute permeabilities as needed, the results shown in Figure 12.14 are obtained. It can be seen that the quality of the history match for both the oil production rate and the instantaneous GOR values is very good. When a history match is obtained that matches both the oil production and instantaneous GOR curves this well, the model can be used with confidence to predict future production information.

Figure 12.14 History match of case 6. Case 6 used permeability ratio data from a second iteration and modified zone thicknesses and absolute permeabilities.

Now that a model has been obtained that matches the available production data and can be used to predict future oil and gas production rates, an assessment of the modifications to the data that were performed during the history match should be made. Table 12.8 contains information concerning the data that were varied in the six cases that have been discussed.

All other input data were held constant at the original values for all six cases. The first and second iterations of the gas-to-oil permeability ratio data led to values higher than the original data, as can be seen in Figure 12.13. In the last section, several reasons for a discrepancy between laboratory-measured permeability ratio values and field-measured values were discussed. These reasons included greater drawdown in areas closer to the wellbore than in areas some distance away from the wellbore, completion and placing on production of some wells before others, two or more strata of varying permeabilities, and gravity drainage effects. All these phenomena lead to unequal stages of depletion within the reservoir. The unequal stages of depletion cause varying saturations throughout the reservoir and hence varying effective permeabilities. The data plotted in Figure 12.13 suggest that the discrepancy between the laboratory-measured permeability ratio values and the field-determined values is not great and that the use of the modified permeability ratio values in the matching process is justified.

For the final match in case 6, the zone thicknesses were increased by about 30% over the original data of case 1, and the absolute permeabilities were reduced by about 39%. At first glance, these modifications in zone thickness and absolute permeability might seem excessive. However, remember that the values of zone thickness and absolute permeability were determined in the laboratory on a core sample, approximately 6 in. in diameter. Although the techniques used in the laboratory are very accurate in the actual measurement of these parameters, to perform the history match, it was necessary to assume that the measured values would be used as average values over the entire 40-ac drainage area of the well. This is a very large extrapolation, and there could be significant error in this assumption. If the small magnitudes of the original values are considered, the adjustments made during the history-matching process are not large in magnitude. The adjustments were only 2.8 md to 3.7 md and 4.2 ft to 5.0 ft. These numbers are large relative to the initial values but are certainly not large in magnitude.

It can be concluded that the model developed to perform the history match for the well in question is reasonable and defendable. More sophisticated equations could have been developed, but for this particular example, the Schilthuis material balance coupled with a flow equation was quite adequate. As long as the simple approach meets the objectives, there is great merit in keeping things simple. However, the reader should realize that the principles that have been discussed about history matching are applicable no matter what degree of model sophistication is used.

12.1 The following data are taken from a volumetric, undersaturated reservoir. Calculate the relative permeability ratio kg/ko at each pressure and plot versus total liquid saturation:

Connate water, Sw = 25%

Initial oil in place = 150 MM STB

Boi = 1.552 bbl/STB

12.2 Discuss the effect of the following on the relative permeability ratios, calculated from production data:

(a) Error in the calculated value of initial oil in place

(b) Error in the value of the connate water

(c) Effect of a small but unaccounted for water drive

(d) Effect of gravitational segregation, both where the high gas-oil ratio wells are shut in and where they are not

(e) Unequal reservoir depletion

(f) Presence of a gas cap

12.3 For the data that follow and are given in Figs. 12.15 to 12.17 and the fluid property data presented in the chapter, perform a history match on the production data in Figs. 12.18 to 12.21, using the Excel worksheet in Table 12.4. Use the new permeability ratio data plotted in Figs. 12.8 and 12.13 to fine-tune the match. The following table indicates laboratory core permeability measurements:

Figure 12.15 Structural map of well locations for Problem 12.3.

Figure 12.16 Isopach map of zone 1 for Problem 12.3.

Figure 12.17 Isopach map of zone 2 for Problem 12.3.

Figure 12.18 Actual oil production and instantaneous GOR for well 5-6 for Problem 12.3.

Figure 12.19 Actual oil production and instantaneous GOR for well 8-16 for Problem 12.3.

Figure 12.20 Actual oil production and instantaneous GOR for well 9-13 for Problem 12.3.

Figure 12.21 Actual oil production and instantaneous GOR for well 14-12 for Problem 12.3.

12.4 Create an Excel worksheet that uses the Muskat method discussed in Chapter 10 in place of the Schilthuis method used in Chapter 12 to perform the history match on the data in Chapter 12.

12.5 Create an Excel worksheet that uses the Tarner method discussed in Chapter 10 in place of the Schilthuis method used in Chapter 12 to perform the history match on the data in Chapter 12.

1. A. W. McCray, Petroleum Evaluations and Economic Decisions, Prentice Hall, 1975.

2. H. B. Crichlow, Modern Reservoir Engineering—A Simulation Approach, Prentice Hall, 1977.

3. P. H. Yang and A. T. Watson, “Automatic History Matching with Variable-Metric Methods,” Society of Petroleum Engineering Reservoir Engineering Jour. (Aug. 1988), 995.

4. T. Ertekin, J. H. Abou-Kassem, and G. R. King, Basic Applied Reservoir Simulation, Vol. 10, Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2001.

5. J. Fanchi, Principles of Applied Reservoir Simulation, 3rd ed., Elsevier, 2006.

6. C. C. Mattax and R. L. Dalton, Reservoir Simulation, Vol. 13, Society of Petroleum Engineers, 1990.

7. M. Carlson, Practical Reservoir Simulation, PennWell Publishing, 2006.

8. J. J. Arps, “Analysis of Decline Curves,” Trans. AlME (1945), 160, 228–47.

9. J. J. Arps, “Estimation of Primary Oil Reserves,” Trans. AlME (1956), 207, 182–91.

10. M. J. Fetkovich, “Decline Curve Analysis Using Type Curves,” J. Pet. Tech. (June 1980), 1065–77.

11. R. G. Agarwal, D. C. Gardner, S. W. Kleinsteiber, and D. D. Fussell, “Analyzing Well Production Data Using Combined-Type-Curve and Decline-Curve Analysis Concepts,” SPE Res. Eval. & Eng. (1999), 2, 478–86.

12. T. Ahmed, Reservoir Engineering Handbook, 4th ed., Gulf Publishing Co., 2010.

13. I. D. Gates, Basic Reservoir Engineering, Kendall Hunt Publishing, 2011.

14. Personal contact with D. W. Green.

15. T. D. Mueller, J. E. Warren, and W. J. West, “Analysis of Reservoir Performance Kg/Ko Curves and a Laboratory Kg/Ko Curve Measured on a Core Sample,” Trans. AlME (1955), 204, 128.