Leon Chaitow

What is NMT? – Introduction

In an earlier text describing neuromuscular technique (NMT), the following introduction was used (Chaitow 2011), as it is again here without apology, as it encapsulates the essence of the subject:

Imagine a palpation technique that becomes a means of therapeutic intervention by virtue of the addition of increased pressure.

Imagine also a palpation technique that, in a non-invasive manner, meets and matches the tone of the tissues it is addressing and sequentially seeks out changes from the norm in almost all accessible (to finger or thumb) areas of the soft tissues.

Imagine this approach as systematically providing information regarding tissue tone, induration, fibrosity, oedema, discrete localized soft tissue changes, areas of altered structure, adhesions or pain – and being able to switch from a painless and pleasant assessment mode, to a treatment focus that starts the process of normalizing the changes it uncovers.

This is neuromuscular technique (NMT).

Two versions

This chapter describes

Neuromuscular technique

(European version) as well as

Neuromuscular therapy

(American version) – both of which are soft-tissue assessment and treatment methods, developed in the

1930s in the UK, and separately in the USA – as well as a variety of adjunctive, soft-tissue manipulation methods complementary to both versions of NMT, examples of which are listed in

Box 14.1

.

Aims of NMT and allied approaches

NMT refers to specialized diagnostic (assessment mode) or therapeutic (treatment mode) manually applied methods.

When used therapeutically, NMT aims to produce modifications in dysfunctional soft tissues (the muscle–fascia web), encouraging a restoration of normality, with a primary focus of deactivating focal points of dysfunctional activity, e.g. myofascial trigger points, as well as paying attention to causative or maintaining features – such as postural or overuse patterns.

Additional NMT attention is towards normalizing imbalances in hypertonic and/or fibrotic tissues, either as an end in itself, or as a precursor to joint mobilization/rehabilitation. In doing so, NMT aims to elicit physiological responses involving mechanoreceptors, Golgi tendon organs, muscle spindles and other proprioceptors, in order to achieve the functional improvements.

Insofar as they integrate with NMT, other means of influencing such neural responses may include all or any of the approaches listed in

Box 14.1

.

NMT attempts to:

•

Offer reflex benefits

•

Deactivate myofascial trigger points and other sources of pain

•

Prepare for other therapeutic methods, such as rehabilitation exercises or manipulation

•

Relax and normalize tense, fibrotic soft tissues

•

Enhance lymphatic and general circulation and drainage

•

Simultaneously offer the practitioner diagnostic information

•

Include re-education (enhanced posture, breathing, ergonomics, etc.) in all therapeutic approaches

•

Assist in rehabilitation.

NMT takes account of issues commonly involved in causing or intensifying pain and dysfunction – including:

•

Biochemical features:

nutritional imbalances and deficiencies, toxicity (exogenous and endogenous), endocrine imbalances (e.g. thyroid deficiency), ischemia, inflammation, and where appropriate refers for medical advice/attention

•

Psychosocial factors:

stress, anxiety, depression, etc. and where appropriate referrals for medical advice/attention

•

Biomechanical factors:

posture, including patterns of use, hyperventilation tendencies, as well as locally dysfunctional states such as hypertonia, trigger points, neural compression or entrapment, and where appropriate referrals for medical advice/attention.

NMT sees its role as attempting to normalize or modulate whichever of these (or additional) influences on musculoskeletal pain and dysfunction can be identified, in order to remove or modify as many etiological and perpetuating influences as possible without creating further distress or requirement for excessive adaptation.

Key point

NMT recognizes self-regulation as the primary agent in recovery, and sees its role as identification and modulation, or removal, of factors that may retard recovery. As an essential adjunct to that role, it sees a requirement to advise on prevention and modification of factors that may lead to adaptation exhaustion.

NMT’s origins

European version (Lief’s) NMT

Stanley Lief

DO, DC, the founder of the British College of Osteopathic Medicine and developer of the European version of neuromuscular technique was greatly influenced in the 1930s by an Ayurvedic practitioner, Dr Dewanchand Varma

, whose manual treatment method involved an early form of what was to become NMT, which he called ‘pranotherapy’.

Varma (1935) discussed the ways in which

‘energy pathways’

could be obstructed

‘by adhesions’,

in which the superficial soft tissues harden –

‘so that the nervous currents can no longer pass through them’.

Varma mentions changes in the skin when such obstructions occur, saying:

‘If the skin becomes attached to the underlying muscle, the current cannot pass, the part loses its sensibility.’

Discussions in

Chapter 2

that describe current thinking and evidence relating to ‘densification’ and reduced sliding potential of superficial fascia correlate well with Varma’s description of the changes he found in these tissues.

Varma’s form of manual soft-tissue manipulation was designed – as he explained – to ‘release’ these palpable obstructions. Varma’s methods were adapted and incorporated by Lief, into what became known as NMT; however, with a quite different therapeutic focus – aimed at normalizing soft-tissue dysfunction, releasing restrictions and easing pain.

Varma suggested a two-stage treatment protocol comprising, as it does in the current use of NMT, an assessment phase that seamlessly merges with treatment delivery, as what is being palpated becomes the target for therapeutic attention, as required.

The actual manipulation of the tissues in Varma’s model was performed by first

‘separating’

skin from underlying tissue, followed by a gentle

‘separation’

of the muscle fibers, a process which required:

‘… highly sensitive fingers, able to distinguish between thick and thin fibers, and … highly developed consciousness and sensitivity, attained by hours of patient daily practice on the living body.’

These skills are still required for successful use of NMT. See the NMT palpation exercise later in this chapter in order to compare Varma’s descriptions with those in the exercise.

Boris Chaitow

DC, co-developer with Lief of NMT, has written (personal communication, 1983):

This unique manipulative formula

[NMT]

is applicable to any part of the body, for any physical and physiological dysfunction, and for both articular and soft tissue lesions.

To apply NMT successfully it is necessary to develop the art of palpation and sensitivity … the whole secret is to be able to recognise the ‘abnormalities’ in the feel of tissue structures.

The pressure applied by the thumb (in general), should involve a ‘variable’ pressure, i.e. with an appreciation of the texture and character of the tissues … The level of the pressure applied should not be consistent because the character and texture of tissue is always variable. These variations can be detected by an educated ‘feel’. … This variable factor in digital pressure constitutes probably the most important quality any practitioner of NMT can learn, enabling him to maintain more effective control of pressure, develop a greater sense of diagnostic feel, and be far less likely to irritate or bruise the tissue.

The clinical relevance of Boris Chaitow’s words deserve emphasis for anyone learning or using NMT, since variation of applied digital pressure, during the application of NMT, is probably the most important

single feature that distinguishes it from other forms of manual therapies. Refining the ability to ‘meet and match’

the tension of the tissues being evaluated is a key feature of Lief’s NMT.

Peter Lief

DC (1963), the son of the developer of NMT, has observed that:

‘It sometimes takes many months of practice to develop the necessary sense of touch, which must be firm, yet at the same time sufficiently light, in order to discern the minute tissue changes that constitute the palpable neuromuscular lesion.’

Brian Youngs

DO (1963), who worked as an assistant to Stanley Lief, described what the palpating fingers are seeking and finding and – because NMT diagnosis and treatment are virtually simultaneous – what they are aiming to achieve:

The palpable changes in soft tissues – as listed by Lief – can be summarized by the word ‘congestion’. This ambiguous word can be interpreted as a past hypertrophic fibrosis. Reflex cordant contraction of a muscle region reduces the blood flow – and in such relatively anoxic regions of low pH and low hormonal concentration, fibroblasts proliferate and increased fibrous tissue is formed. This results in an increase in the thickness of the existing connective tissue partitions – the epimysia and perimysia – probably infiltrating deeper between the muscle fibres to affect the normal endomysia.

Thickening of the fascia and subdermal connective tissue occurs if these structures are similarly affected by a reduced blood flow … Fibrosis seems to occur automatically in areas of reduced blood flow … depending upon the constitutional background. Where tension is the aetiological factor, fibrosis seems inevitable.’

The description by Young of the myofascial environment of ischemia and congestion is, of course, precisely the background out of which myofascial trigger points evolve. It should be no surprise, therefore, that NMT is seen as an ideal treatment approach for identifying and deactivating trigger points (see notes on integrated neuromuscular inhibition technique (INIT) later in the chapter.)

Youngs suggested that Lief’s NMT may offer beneficial effects, including:

•

Restoration of muscular balance and tone and consequent pain reduction and enhanced function

•

Encouragement of normal trophicity in muscular and connective tissues by altering the histological picture from a pathohistological to a physiologic–histological pattern, with more normal vascular and hormonal responses

•

Potentially providing visceral benefits by reducing levels of somatovisceral reflex activity

•

Improving circulation and drainage relating to areas of stasis.

American version NMT

The original work that evolved into the American version of NMT took place in the late 1970s and early 1980s, based largely on the methods devised and taught by Raymond Nimmo DC (1959) – known as ‘receptor-tonus technique’.

Nimmo’s research into the pathological influences and relevance, as well as the therapeutic implications of treating what he termed ‘noxious pain points’, paralleled the work of his contemporary, Janet Travell MD, in relation to her research into myofascial trigger points (Travell & Simons 1999).

Nimmo’s approach to these pain generators was modified and expanded by others (Vannerson & Nimmo 1971), building on the writings and research of Travell and Simons (1999).

American version NMT now incorporates systematic approaches to health enhancement, with

attention to biochemical, biomechanical and psychosocial causative and maintaining factors.

Despite major evolutionary differences, the two versions of NMT are currently very similar. Both utilize a full range of soft-tissue manipulation modalities (see list in

Box 14.1

) as well as evidence-based rehabilitation methodologies. Both versions also focus on the full range of somatic dysfunction and pain, and the causes of these – with the American version possibly paying more attention to myofascial pain than Lief’s model.

NMT’s evolution – a combined training and a new profession

Neuromuscular physical therapists, trained in both versions of NMT, have formed an Association of Neuromuscular Therapists, and are now recognized health care providers in the Republic of Ireland, with a variety of basic and advanced courses available. This, together with the establishment of a Masters level degree course in Neuromuscular Therapy, validated by the University of Chester in the UK, marks a major point in the continued evolution of NMT in Europe.

In the USA, members of organizations such as the National Association of Myofascial Trigger Point Therapists are strong advocates of NMT.

The evolution of myofascial pain

Stecco et al. (2013) offer a compelling description of the origins of myofascial pain.

They note that aponeurotic fascia (such as the thoracolumbar fascia) is made up of layers of dense fascia where force and load are absorbed, dispersed and transmitted from myofascial insertions (as described in

Ch. 1

). These richly innervated layers are separated by looser connective tissue that encourages gliding between deep fascial layers, due to the presence of hyaluronic acid (HA).

They also note that epimysial fascia (surrounding muscles) contains free nerve endings and is directly connected to muscle – creating functional continuity between muscles, joints and deeper fascial structures:

‘The collagen fibers of the epimysial fasciae is occupied by the matrix or ground substance, rich in proteoglycans, and in particularly hyaluronic acid (HA).’

Following injury (overuse, misuse, etc.), fatty infiltration occurs, HA decreases, viscosity and acidification increases, sliding function reduces, and ‘

free nerve endings become hyperactivated

’, resulting in local inflammation, pain and sensitization. These changes can be reversed by reducing stiffness, density and viscosity – and improving pH – all potentially possible via manual therapies (as described in

Ch. 5

).

Therefore:

‘Dysfunction of fascia –

[involves]

– alteration of the loose connective tissue (LCT) comprising adipose cells, glycosaminoglycans, and HA. … an alteration of the quantity or quality of the component of the LCT may change the viscosity and therefore the function of the lubricant that the LCT facilitates … We suggest this syndrome

[myofascial pain]

be defined as ‘densification of fascia’ ….

[and that]

… this is different from the functional alterations observed from morphological alterations such as frank fibrosis.’

NOTE

: Compare the Stecco description above with that of Gautschi, below, in

Box 14.2

.

Validating studies

Regarding NMT’s efficacy in achieving reversal of such changes, research validation is slowly appearing, for example:

•

Jaw pain:

Spanish researchers (Ibáñez-García et al. 2009) show that NMT (Lief’s method) and strain–counterstrain (

Ch. 15

) are equally, and significantly, effective in the management of latent trigger points in the masseter muscle.

•

Chronic neck pain:

Escortell-Mayor et al. (2011) treated patients with chronic neck pain (‘mechanical neck disorder’) either with NMT and complementary soft-tissue approaches or by means of electrotherapy (TENS). A significant degree of short-term pain relief was noted in both groups with approximately 30% maintaining their improvement at 6-month follow-up.

•

Myofascial upper trapezius pain (1):

Nagrale and colleagues (2010) demonstrate the efficacy of NMT when incorporated into the INIT focused trigger point protocol (INIT is described below in

Box 14.2

; Chaitow 1994).

•

Myofascial upper trapezius pain (2):

Saadat et al. (2018) used the INIT protocol in a controlled research study, to treat upper trapezius myofascial pain. Pain intensity significantly decreased in the intervention group immediately after treatment (P=0.01) and 24 hours after treatment (P=0.009) in comparison with the control group.

•

Shoulder impingement pain:

using a combination of trigger point release (

Ch. 21

) and neuromuscular techniques, Hidalgo-Lozano et al. (2011) were able to demonstrate that manual treatment of active trigger points (TrPs) reduced spontaneous pain and increased pain tolerance in patients with shoulder impingement. They note that:

‘current findings suggest that active TrPs in the shoulder musculature may contribute to shoulder

[pain]

complaint and sensitization in patients with shoulder impingement syndrome’.

•

Whiplash:

Fernández-de-las-Peñas et al. (2005) report that the soft-tissue techniques used in their protocol comprised neuromuscular technique in paraspinal muscles, muscle energy techniques (

Ch. 12

) in the cervical spine, myofascial release (

Ch. 13

) in the occipital region, and myofascial trigger point manual therapies (

Ch. 21

), as required.

‘The manipulative protocol developed by our research group has been shown to be effective in the management of whiplash injury. The biomechanical analysis of a rear-end impact justifies some of the manipulative techniques … myofascial trigger points in trapezius muscles, suboccipital muscles, scalene muscles and sternocleidomastoid muscles, commonly play an important role in the treatment of people suffering from post-whiplash symptoms.’

•

Plantar heel pain:

Renan-Ordine et al. (2011) compared the benefits of self-stretching with the same stretching methods accompanied by NMT, in treatment of 60 patients with plantar heel pain. One group of patients performed calf and foot stretches, and had hands-on therapy (NMT) provided by a physical therapist, while the other group only performed stretches. The treatment performed by the physical therapist focused on treating trigger points that felt ‘knotty’ and which were significantly painful when pressed. The researchers found greater improvements in patients who both performed the stretches and who also received hands-on therapy. The scale of benefit was clinically important for both improved physical function as well as for bodily pain. Importantly, there was also a significant increase in pain threshold levels within the NMT group, supporting the suggestion of the general pain modulating effects of this form of therapy.

Key point

A number of these studies demonstrate the practical, clinical way in which NMT may be successfully used alongside complementary modalities, most of which are outlined in different chapters in this book. The other listed modalities in

Box 14.1

are briefly defined in

Box 14.2

.

Box 14.2 Adjunctive/complementary (to NMT) soft-tissue methods

Box 14.1

lists the major methods that are used alongside NMT, both European and American versions. Most of these topics are covered in separate chapters – with those that are not, briefly described and defined below.

Active Release Technique

®

(ART)

Active Release Technique®

is a modality with similarities to traditional ‘pin and stretch’ techniques. ART involves the practitioner isolating a contact point close to the region of soft-tissue dysfunction, after which the patient is directed to move in ways that produce a longitudinal sliding motion of soft tissues (nerves, fascia, ligaments, muscles) beneath the anchored contact point. Alternatively the movements may be initiated by the practitioner, or may involve both passive and active movements.

Several studies have evaluated the efficacy of ART in different settings, for example:

Increased pain threshold (Robb & Pajaczkowski 2010)

Increased pain threshold (Robb & Pajaczkowski 2010)

Increased hamstring flexibility (George 2006)

Increased hamstring flexibility (George 2006)

Carpal tunnel syndrome (George et al. 2006)

Carpal tunnel syndrome (George et al. 2006)

Quadriceps strength (Drover et al. 2004).

Quadriceps strength (Drover et al. 2004).

Harmonic technique (and oscillation)

Harmonic technique involves the induction of cyclical motion in different body regions in an attempt to bring about a state of resonance in body tissues. The method differs from rhythmic articulation where the practitioner imposes a rhythm on the patient’s tissues. In harmonic technique, the practitioner tunes in to and uses the patient’s own free oscillation frequency to induce the cyclical motion

A study of the method found that the motion induced in the lumbopelvic complex, using a modified harmonic technique – involving rhythmic rocking – displayed properties of harmonic motion (Waugh 2007). The advantages of this approach in relation to fascial function is suggested by evidence of enhanced HA production when oscillating motions are induced, as explained in

Chapter 1

.

Integrated neuromuscular inhibition technique (INIT)

INIT is a validated sequence of modalities used in treatment of myofascial pain (Chaitow 1994). Following identification of an active myofascial trigger point (TrP), a sequence is introduced:

1.

Rhythmic intermittent compression of the TrP until sensitivity reduces, followed by

2.

The application of counterstrain positioning of the tissues (see

Ch. 15

), followed by

3.

An isometric contraction of the tissues housing the trigger point and subsequent stretching of those local tissues (see

Chs 12 & 21

).

4.

Finally, an isometric contraction of the entire muscle (not just the local area) is used as a precursor to stretch of the muscle.

Studies have validated the method when compared with other trigger point deactivation approaches (Nagrale et al. 2010).

Gautschi’s Swiss variation

Gautschi (2008, 2010) offered a fascia-oriented explanation for a manual treatment model (‘Swiss approach’) for management of myofascial pain, that has distinct similarities to the NMT/INIT (Chaitow 1994) model, as described above.

1.

Gautschi notes that the flow of impulses from proprioceptive and nociceptive receptors, in the connective tissue of muscle, are altered when such tissues are dysfunctional.

2.

Such changes, it is suggested, become chronic

(‘chronification of myofascial pain’

) as myofascial syndrome progresses, and the taut bands associated with trigger points place fascial structures under permanent tension, affecting both fascial architecture and function.

‘Taut bands reveal themselves in the form of muscle shortening. Restricted mobility and altered movement and posture patterns appear and can lead to adaptation processes and the decompensation of fascial structures.’

3.

The sequence of manual trigger point treatment, as advocated by the Swiss model, involves:

a.

Manual compression

of the myofascial trigger point creates temporary ischemia – followed by reactive hyperemia and an increase in metabolism. There is a simultaneous relaxation reflex of the taut band associated with the mTrP

b.

Manual stretching

of the local TrP region has the effect of reducing local edema and modifying reactive connective tissue adhesions (‘

pathological crosslinks’

)

c.

Fascial stretching technique

(

manual stretching of the superficial and intramuscular fascia

) reduces sympathetic activity and tone

d.

Fascia separation technique

frees adhesions between fascia of neighboring muscles

e.

Stretching and relaxation

improves muscle flexibility

f.

Functional training:

improved ergonomics reduces incorrect load on the muscles and fascia.

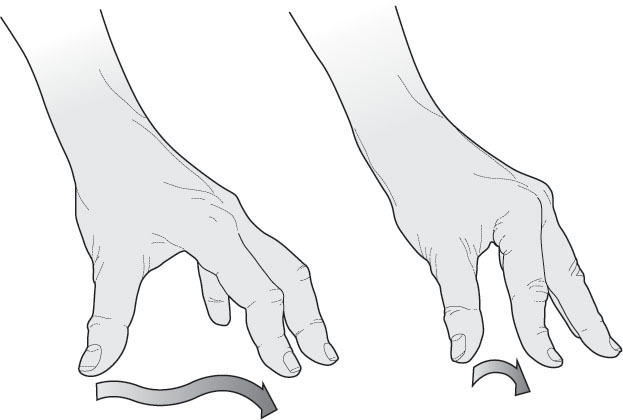

Specific (‘scar/adhesion’) release techniques (

Fig. 14.1

)

Lief described and used methods that could be applied to tight, fibrosed, contracted soft tissue areas of the body, where scarring or adhesion formation is inhibiting normal tissue function (Newman Turner 1984).

Figure 14.1

Specific release technique (see description in

Box 14.2

).

Method:

1.

Having located an area of contracted tissue, the therapist’s middle finger (of the right hand in this description) locates a point of strong restriction and these tissues are drawn towards the practitioner to the limit of pain-free movement.

2.

The therapist then abducts the right elbow as the shoulder is internally rotated, adding torsional load to the already extended and compressed tissues.

3.

The middle finger (right hand) and its neighbors should by now be flexed and fairly rigid, and be imparting force in three directions, i.e. downwards (towards the floor), towards the practitioner, and with a slight rotational addition.

4.

The tip of the flexed thumb of the left hand is then placed no more than ¼ inch (0.5 cm) adjacent to the middle finger of the right hand, exerting downward pressure (towards the floor) and away from the therapist – as the left elbow is abducted and the shoulder internally rotated, in order to provide a counter-pressure to the forces being created by the right hand.

5.

The fulcrum created by the tensions created by the right hand fingers pulling one way, and the left thumb pushing the other, while also being torsioned against each other, builds a combination of tensional forces in several directions at the same time.

6.

After all slack has been removed, a very rapid clockwise movement of the right hand and anticlockwise movement of the left hand produces a high-velocity soft-tissue ‘springing’ release – as the elbows snap towards the trunk and the palms of the hands turn rapidly upwards. The amount of force imparted should not produce pain.

7.

The sequence can be repeated several times to start a process of change in the connective tissues – usually accompanied by erythema.

8.

Variations of hand placement and directions of imposed force offer alternatives.

Key Point

A variety of non-invasive approaches are seen to integrate with, and are complementary to, the European (Lief’s) version of neuromuscular technique, as described above. The eclectic collection of modalities, above (see

Box 14.2

) – along with osteopathic techniques such as muscle energy technique (

Ch. 12

) and positional release methods (

Ch. 15

), as well as basic massage and other soft-tissue focused methods – comprise a comprehensive model which has – for obvious reasons – been termed soft-tissue manipulation (Chaitow 1984).

NMT palpation exercise

NOTE

: The NMT palpation exercise described in detail below derives from the Lief European tradition, and would be preceded, accompanied, or followed, by other palpation methods, such as those described in

Chapter 4

(STAR assessment, skin function palpation).

Although described as a ‘

palpation

’ exercise, it is important to grasp that palpation and treatment are not seen as separate operations in NMT – one flows to and from the other, backwards and forwards.

As areas of local interest are identified they are explored and, if necessary, treated using slightly firmer pressure than the palpation level, or one or

other of the range of complementary methods listed at the start of this chapter.

During the NMT palpation exercise described below, try to focus on as many of the following features as possible, as your contact fingers or thumb moves through and across the tissues being explored:

•

Temperature changes:

Hypertonic muscle will probably be warmer than chronically fibrosed tissue, and there may be variations within a few centimeters.

•

Tenderness:

Ask for feedback whenever there seems a ‘different’ feel in the tissues being palpated.

•

Edema:

Pay attention to any impression of swelling, fullness, ‘bogginess’ or congestion

•

Fiber direction:

Try to establish the orientation of tissues, their likely attachment sites, and the vectors of force that daily living imposes on them.

•

Localized contractures:

Local, sometimes very small, areas, may display evidence of reflex or trigger point activity with the presence of taut bands or minute contracture ‘knots’ that are exquisitely painful on pressure, and which may refer pain to distant areas (see

Ch. 21

).

Ask yourself - as you assess:

•

What tissues am I feeling?

•

What is the significance of what I can feel in relation to the individual’s condition (posture, for example) or symptoms?

•

How does what I can feel relate to any other areas of dysfunction I may have noted elsewhere?

•

Is what I can feel acute or chronic?

•

Is this a local problem, or part of a larger pattern of dysfunction?

•

What do these palpable changes mean?

NMT palpation protocol

A light lubricant is always used in NMT to avoid skin friction.

The examination/treatment table should be at a height that allows the therapist to stand erect, legs separated for ease of weight transference, with the assessing arm fairly straight at the elbow.

This allows the practitioner’s bodyweight to be transferred down the extended arm through the thumb, imparting any degree of force required, from extremely light to quite substantial, simply by leaning on the arm (

Fig. 14.2

). This may present a problem for practitioners whose thumbs are too flexible or unstable. A solution is for them to use only the finger contact as described below.

Figure 14.2

NMT thumb stroke – the stationary fingers provide a fulcrum as the moving thumb weaves through the tissues, assessing and treating.

For finger palpation the main contact is usually made with the tip of the middle or index finger, ideally supported by a neighboring digit (

Fig. 14.3

).

For the thumb stroke it is important that the fingers of the assessing/treating hand act as a fulcrum, and that they lie ahead of the contact thumb, allowing the stroke being made by the thumb to move across the palm of the hand, in the direction of the ring or small finger, as the stroke progresses.

Figure 14.3

NMT finger stroke intercostal assessment, with non-active hand supporting and distracting tissue to prevent bunching.

For balance and control, the fingers should be spread (as in

Fig. 14.2

), the tips of fingers providing a point of balance, a fulcrum or ‘bridge’, in which the palm is arched in order to allow free passage of the thumb towards one of the fingertips, as the thumb moves in a direction that takes it away from the practitioner’s body.

Each thumb stroke, whether diagnostic or therapeutic, covers approximately 4–5 cm before the thumb stops, as the fingers/fulcrum is then moved, as the thumb stroke continues searching through the tissues.

In contrast, finger strokes move towards the practitioner, commonly with the other hand acting to prevent tissues from bunching or mounding.

Variable pressure essential

The very essence of either the thumb or finger contact involves application of a variable degree of pressure

that allows the palpating contact to ‘insinuate’ its way through whatever fibrous, indurated or contracted structures it meets. In the palpation mode of NMT these strokes ‘meet and match’ tissue tensions, so that the therapist becomes aware of changes in tissue resistance, a fraction ahead of the thumb or finger contact, as it teases its way through the tissues.

This variability of pressure represents a major difference between European and American NMT, with the latter tending to employ strokes that glide across or through the tissues being assessed, in a firm manner, with little pressure variation. In European NMT, degree of resistance or obstruction presented by the palpated tissues determines the degree of effort required.

Tense, contracted or fibrous tissues are never simply overcome by force, instead, the fibers are ‘worked through’, using a constantly varying amount of pressure, as angles of application modify. If reflex pressure techniques are being employed, a much longer stay on a point will be needed, but in normal diagnostic and therapeutic use the thumb continues to move as it probes, decongests and generally treats the tissues.

All significant findings – whether relating to the quality of the tissues, or of responses from the patient, particularly in relation to sensitivity or pain, should be recorded on a chart. A degree of vibrational contact, as well as variable pressure, allows the contact to have an ‘intelligent’ feel that does not risk traumatizing or bruising tissues, even when or if heavy pressure is used.

In deeper NMT palpation, or when a shift occurs from palpation to treatment, the pressure of the palpating fingers or thumb may need to increase sufficiently to make contact with structures, such as the paravertebral musculature, without provoking a defensive response.

The changes that might be sensed during palpation could include immobility/rigidity, tenderness, edema, deep muscle tension, fibrotic and interosseous changes.

Apart from fibrotic changes, characteristic of chronic dysfunction, all these changes can be found in either acute or chronic problems.

American NMT: the palpation glide

Effleurage (gliding stroke) forms an important component of the American version of NMT (

Fig. 14.4

).

Gliding strokes warm the superficial fascia and are thought to enhance drainage. As with the European assessment methods described above, the gliding process helps to identify contracted bands, along with nodules and tender points. Gliding repeatedly on these may reduce their size and tenacity. Clinical experience suggests that gliding on the tissues several times, then working somewhere else and returning to glide again, may produce optimal results. The direction of application of glides may be either with or across the direction of the muscle fibers, or more usually, a combination of both. Following the course of lymphatic flow is particularly suggested if tissues are congested.

Figure 14.4

NMT glide stroke: the fingers support and steady the hands as the primary tools – the thumbs – assess and treat palpation findings.

Therapeutic objectives: palpation becomes treatment

NMT – both versions – aims to produce modifications in dysfunctional tissue, encouraging a restoration of normality, with a primary focus of deactivating focal points of reflexogenic activity such as myofascial trigger points. NMT therefore utilizes physiological responses involving neurological mechanoreceptors, Golgi tendon organs, muscle spindles and other proprioceptors, in order to achieve the desired responses.

An alternative focus is towards normalizing imbalances in hypertonic and/or fibrotic tissues, either as an end in itself or as a precursor to joint mobilization.

Similarly, it should be obvious that the very nature of NMT evaluation makes it an ideal tool for searching for superficial fascial restrictions, characterized by loss of gliding potential, as explained in earlier chapters, and of assisting in restoration of normal function.

The clinical examination that uses NMT – as described above – should move seamlessly from the gathering of information, into application of treatment objectives. The process of discovery leads to therapeutic action as the practitioner searches for evidence of tissue dysfunction, and then applies appropriate techniques, turning ‘finding into fixing’. This transition from examination to treatment and back to examination is a characteristic of NMT.

Use of complementary modalities

Insofar as they integrate with NMT, other modalities, including positional release (strain–counterstrain) and muscle energy methods, are seen to form a natural set of allied approaches. Traditional massage methods that encourage a reduction in retention of metabolic wastes are included in this category of allied approaches.

Conclusion

Emerging as it does from an amalgam of traditional Asian massage methods (‘pranotherapy’), through a prism of osteopathic assessment approaches (see notes on STAR palpation in

Ch. 4

), while being influenced by physical therapy palpation techniques (see notes on skin assessment methods, also

Ch. 4

) – with distinct influences from research into myofascial pain – modern NMT has both a strong interdisciplinary flavor.

Now validated in a number of studies, NMT can be seen to be a useful assessment and treatment approach to almost all other soft-tissue approaches – as well as evolving to become the major therapeutic tool of an emerging profession of neuromuscular therapists, both in Europe and the USA.

References

Chaitow L 1984 Soft tissue manipulation. Thorsons HarperCollins, London

Chaitow L 1994 Integrated neuromuscular inhibition technique. Br J Osteopath 13:17–20

Chaitow L 2011 Modern neuromuscular techniques, 3rd edn. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, Edinburgh, p 35

Drover J et al 2004 Influence of active release technique on quadriceps inhibition and strength: a pilot study. J Manip Physiol Ther 27(6):408–413

Escortell-Mayor E et al 2011 Primary care randomized clinical trial: manual therapy effectiveness in comparison with TENS in patients with neck pain. Man Ther 16(2011):66–73

Fernández-de-las-Peñas C et al 2005 Manual treatment of post-whiplash injury. J Bodyw Mov Ther 9:109–119

Gautschi R 2008 Myofasziale Triggerpunkt-Therapie. In: van den Berg, F. (Hrsg.) Angewandte Physiologie, Bd. 4: Schmerzen verstehen und beeinflussen. 2. erweiterte Auflage. Thieme, Stuttgart, pp 310–366

Gautschi R 2010 Manuelle Triggerpunkt-Therapie, Myofasziale Schmerzen und Funktionsstörungen erkennen, verstehen und behandeln. Thieme, Stuttgart.

George J 2006 The effects of active release technique on hamstring flexibility: a pilot study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 29:224–227

George J et al 2006 The effects of active release technique on carpal tunnel patients: a pilot study. J Chiropr Med 5(4):119–122

Hidalgo-Lozano A et al 2011 Changes in pain and pressure pain sensitivity after manual treatment of active trigger points in patients with unilateral shoulder impingement: A case series. J Bodyw Mov Ther (2011)15:399–404

Ibáñez-García J et al 2009 Changes in masseter muscle trigger points following strain-counterstrain or neuro-muscular technique. J Bodyw Mov Ther 13(1):2–10

Lief P 1963 British naturopathic. British Naturopathic Journal 5(10):304–324

Nagrale et al 2010 Efficacy of an integrated neuromuscular inhibition technique on upper trapezius trigger points in subjects with non-specific neck pain. J Man Manip Ther 18(1):37–43

Newman Turner R 1984 Naturopathic medicine: treating the whole person. Thorsons, Wellingborough, UK

Nimmo R 1959 Factor X. The receptor (1):4. Reprinted in: Schneider M, Cohen J, Laws S (eds) 2001 The collected writings of Nimmo and Vannerson, pioneers of chiropractic trigger point therapy. Self-published, Pittsburgh

Renan-Ordine R et al 2011 Effectiveness of myofascial trigger point manual therapy combined with a self-stretching protocol for the management of plantar heel pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 41(2):43–51

Robb A, Pajaczkowski J 2010 Immediate effect on pain thresholds using active release technique on adductor strains: pilot study. J Bodyw Mov Ther 15(1):57–62

Saadat Z et al 2018 Effects of Integrated Neuromuscular Inhibition Technique on pain threshold and pain intensity in patients with upper trapezius trigger points. J Bodyw Mov Ther (in press)

Stecco A et al 2013 Fascial components of the myofascial pain syndrome. Curr Pain Headache Rep 17:352

Travell J, Simons D 1999 Myofascial pain and dysfunction: the trigger point manual, vol 1, 2nd edn. The lower body. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore

Vannerson J, Nimmo R 1971 Specificity and the law of facilitation in the nervous system. The receptor 2(1). Reprinted in: Schneider M, Cohen J, Laws S (eds) 2001 The collected writings of Nimmo and Vannerson, pioneers of chiropractic trigger point therapy. Self-published, Pittsburgh

Varma D 1935 The human machine and its forces. Health for All, London, 1935

Waugh J 2007 An observational study of motion induced in the lumbar–pelvic complex during ‘harmonic’ technique: a preliminary investigation. Int J Osteopath Med 10(2–3):65–79

Youngs B 1963 The physiological background of neuromuscular technique. British Naturopathic Journal and Osteopathic Review 5:176–178

Neuromuscular technique (Lief’s European version)

Neuromuscular technique (Lief’s European version)

Neuromuscular therapy (American version)

Neuromuscular therapy (American version)