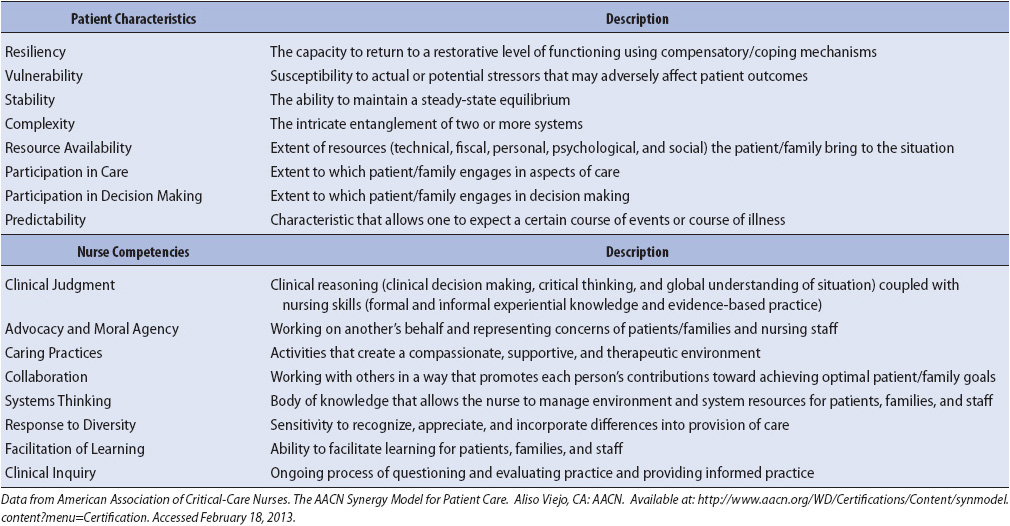

TABLE 2-1. CORE PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS AND NURSE COMPETENCIES AS DEFINED IN THE SYNERGY MODEL

KNOWLEDGE COMPETENCIES

1. Discuss the importance of a multidisciplinary plan of care for optimizing clinical outcomes.

2. Describe interventions for prevention of common complications in progressive care patients:

• Deep venous thrombosis

• Infection

• Sleep pattern disturbances

• Skin breakdown

3. Discuss interventions to maintain psychosocial integrity and minimize anxiety for the progressive care patient and family members.

4. Describe interventions to promote family-focused care, and patient and family education.

5. Identify necessary equipment and personnel required to safely transport the progressive care patient within the hospital.

6. Describe transfer-related complications and preventive measures to be taken before and during patient transport.

It is important to be mindful of the unique needs of patients and their families as they transition from the intensive care or medical-surgical environment to a progressive care environment. Because lengths of stay in progressive care are typically short, preparation for the next anticipated level of care is initiated on arrival to the progressive care unit. Patient and family education is key to preparing for transitioning or potential discharge to home. While it is difficult to ensure all education is done during this short length of stay (LOS), it is important to evaluate educational needs and start a good knowledge foundation. It is also important to recognize anxiety that the patient may experience due to the change of level of care. If the patient is transferring from critical care to progressive care, the patient and family may feel nervous at the perceived decrease in level of nursing vigilance and technology. This can create questions on the part of the patient and family as to whether staff will be available to respond quickly to patient needs and changes in condition. Conversely, if a patient is transferred to the progressive care unit from a medical-surgical area because of declining physiologic status,

anxiety on the part of the patient and family is related to the uncertainty of the patient condition. In either case, it is important to reassure the patient and family that the progressive care nurses have the skills and equipment needed to monitor and meet the needs of the patient.

The achievement of optimal clinical outcomes in the progressive care patient requires a coordinated approach to care delivery by multidisciplinary team members. Experts in nutrition, respiratory therapy, progressive care nursing and medicine, psychiatry, and social work, as well as other disciplines, must work collaboratively to effectively and efficiently provide optimal care.

The use of a multidisciplinary plan of care is a useful approach to facilitate the coordination of a patient’s care by the multidisciplinary team and optimize clinical outcomes. These multidisciplinary plans of care are increasingly being used to replace individual, discipline-specific plans of care. Each clinical condition presented in this text discusses the management of patient needs or problems with an integrated, multidisciplinary approach.

The following section provides an overview of multidisciplinary plans of care and their benefits. In addition, this chapter discusses common patient management approaches to needs or problems during acute illnesses that are not diagnosis specific, but common to a majority of progressive care patients, such as sleep deprivation, skin breakdown, and patient and family education. Additional discussion of these needs or problems is also presented in other chapters related to specific disease management.

A multidisciplinary plan of care is a set of expectations for the major components of care a patient should receive during the hospitalization to manage a specific medical or surgical problem. Other types of plans include clinical pathways, interdisciplinary care plans, and care maps. The multidisciplinary plan of care expands the concept of a medical or nursing care plan and provides an interdisciplinary, comprehensive blueprint for patient care. The result is a diagnosis-specific plan of care that focuses the entire care team on expected patient outcomes.

The multidisciplinary plan of care outlines what tests, medications, care, and treatments are needed to discharge the patient in a timely manner with all patient outcomes met. Multidisciplinary plans of care have a variety of benefits to both patients and the hospital system:

• Improved patient outcomes (survival rates, morbidity)

• Increased quality and continuity of care

• Improved communication and collaboration

• Identification of hospital system problems

• Coordination of necessary services and reduced duplication

• Prioritization of activities

• Reduced LOS and healthcare costs

Multidisciplinary plans of care are developed by a team of individuals who closely interact with a specific patient population. It is this process of multiple disciplines communicating and collaborating around the needs of the patient that creates benefits for the patients. Representatives of disciplines commonly involved in pathway development include physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, physical therapists, social workers, and dieticians. The format for the multidisciplinary plans of care typically includes the following

categories:

• Discharge outcomes

• Patient goals (eg, pain control, activity level, absence of complications)

• Assessment and evaluation

• Consultations

• Tests

• Medications

• Nutrition

• Activity

• Education

• Discharge planning

The suggested activities within each of these categories may be divided into daily activities or grouped into phases of the hospitalization (eg, preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative phases). All staff members who use the path require education as to the specifics of the pathway. This team approach in development and utilization optimizes communication, collaboration, coordination, and commitment to the pathway process.

With the increasing use of electronic health records, multidisciplinary plans of care or pathways are evolving into many different forms as institutions transition from paper to electronic formats. Some electronic formats mimic the paper version. Other institutions may incorporate pieces of the pathway into varied electronic flow sheets (eg, orders, assessments, interventions, education, outcomes, specific plans of care). Regardless of the specific format, multidisciplinary plans of care are used by a wide range of disciplines. Each individual who assesses and implements various aspects of the multidisciplinary plan of care is accountable for documenting that care in the approved format. Specific items of the pathway can then be evaluated and tracked to determine if the items are met, not met, or are not applicable. Items on the plan of care that are not completed typically are termed variances, which are deviations from the expected activities or goals outlined. Events outlined on the plans of care that occur early are termed positive variances. Negative variances are those planned events that are not accomplished on time. Negative variances typically include items not completed due to the patient’s condition, hospital system problems (diagnostic studies or therapeutic interventions not completed within the optimal time frame), or lack of orders. Assessing patient progression on the pathway helps caregivers to have an overall picture of patient recovery as compared to the goals and can be helpful in early recognition and resolution of problems. It is important to remember that individual discipline documentation on the plan of care or pathway does not preclude the need for ongoing, direct communication between disciplines in order to facilitate optimal patient care and achievement of goals.

Planning care for individual acutely ill patients begins with ensuring each nurse caring for a patient has the corresponding competencies and skills to meet the patient’s needs. The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses has developed the AACN Synergy Model for Patient Care to delineate core patient characteristics and needs that drive the core competencies of nurses required to care for patients and families (Table 2-1). All eight competencies identified in the Synergy Model are essential for the progressive care nurse’s practice, though the extent to which any particular competency is needed on a daily basis depends on the patient’s needs at that point in time. When making patient staffing assignments, the charge nurse or nurse manager should assess the priority needs of the patient and assign a nurse who has the proficiencies to meet those patient needs. By matching the competencies of the nurse with the needs of the patient, synergy occurs resulting in optimal patient outcomes.

Progressive care units are high-technology, high-intervention environments with multiple providers. It is an ongoing challenge for nurses to be ever thoughtful of minimizing the safety risks inherent in such an environment. Progressive care units are constantly working to improve ways to optimize care and minimize risks to patients.

As the nurse develops an ongoing plan of care, he or she must incorporate safety initiatives into that care. Conditions of acutely ill patients can change quickly, so ongoing awareness and vigilance is the key even when the patient appears to be stable or improving. The progressive care unit environment itself can contain safety issues. Inappropriate use of medical gas equipment or ventilator settings, electrical safety with invasive lines, certain types of restraints, bedside rails, and cords and tubings lying on the floor may all be hazardous to the acutely ill patient. In addition, with so many healthcare providers involved in the care of each patient, it is imperative that communication remains accurate and timely. Use of a standardized handoff communication tool is a fundamental step in preventing errors related to poor communication among healthcare providers.

Finally, as described in more detail under section “Prevention of Common Complications,” many common complications can be prevented by patient safety initiatives such as preventing ventilator-acquired pneumonia, blood stream infections, and urinary tract infections. In addition to meticulous care of patients, it is advisable for the healthcare team to have daily discussions on rounds as to whether the invasive lines and catheters need to remain in place. Removing these pieces of equipment as soon as clinically appropriate is the first step in preventing complications from occurring.

The development of an acute illness, regardless of its cause, predisposes the patient to a number of physiologic and psychological complications. A major focus when providing care to progressive care patients is the prevention of complications associated with acute illness. The following content overviews some of the most common complications.

Ongoing assessments and monitoring of progressive care patients (see Table 1-13) are key to early identification of physiologic changes and to ensuring that the patient is progressing to the identified transition goals. It is important for the nurse to use critical thinking skills throughout the provision of care to accurately analyze patient changes.

After each assessment, the data obtained should be looked at in totality as they relate to the status of the patient. When an assessment changes in one body system, rarely does it remain an isolated issue, but rather it frequently either impacts or is a result of changes in other systems. Only by analyzing the entire patient assessment can the nurse see what is truly happening with the patient and anticipate interventions and responses.

When you assume care of the patient, define what goals the patient should achieve by the end of the shift, either as identified by the plan of care or by your assessment. This provides opportunities to evaluate care over a period of time. It prevents a narrow focus on the completion of individual tasks and interventions rather than the overall progression of the patient toward various goals. In addition, it is key to anticipate the potential patient responses to interventions. For instance, have you noticed that you need to increase the insulin infusion in response to higher glucose levels every morning around 10.00 AM? When looking at the whole picture, you may realize that the patient is receiving several medications in the early morning that are being given in a dextrose diluent. Recognition of this pattern helps you to stabilize swings in blood glucose.

Progressive care patients are at increased risk of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) due to their underlying condition and immobility. Routine interventions can prevent this potentially devastating complication from occurring. There is increasing evidence to support early and progressive mobility of patients to decrease the risk of DVTs in addition to improving respiratory function and muscle strength. It takes a team effort to fully implement early mobility protocols, including nurses, physical therapists, respiratory therapists, and physicians. Increased mobility is emphasized as soon as the patient is stable. Even transferring the patient from the bed to the chair changes positioning of extremities and improves circulation. Additionally, use of sequential compression devices assists in enhancing lower extremity circulation. Avoid placing intravenous (IV) access in the groin site or lower limbs as this impedes mobility and potentially blood flow, and can thus increase DVT risk. Ensure adequate hydration. Many patients may also be placed on low-dose heparin or enoxaparin protocols as a preventative measure.

Progressive care patients are especially vulnerable to infection during their stay in the progressive care unit. It is estimated that 20% to 60% of progressive care patients acquire some type of infection. In general, hospital-acquired infections because of the high use of multiple invasive devices and the frequent presence of debilitating underlying diseases are a risk in the progressive care unit. Hospital-acquired infections increase the patient’s LOS and hospitalization costs, and can markedly increase mortality rates depending on the type and severity of the infection and the underlying disease. Although urinary tract infections are the most common hospital-acquired infections in the progressive care setting, hospital-acquired pneumonias are the second most common infection and the most common cause of mortality from infections. Details of specific risk factors and control measures for the prevention of hospital-acquired pneumonias are presented in Chapter 10 (Respiratory System). Other frequent infections include bloodstream and surgical site infections. It is imperative for progressive care practitioners to understand the processes that contribute to these potentially lethal infections and their roles in preventing these untoward events.

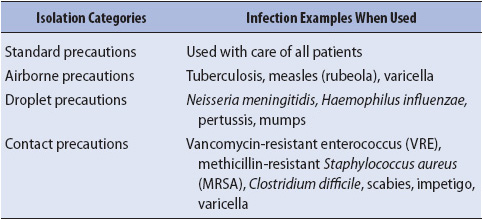

Standard precautions, sometimes referred to as universal precautions or body substance isolation, refer to the basic precautions that are to be used on all patients, regardless of their diagnosis. The general premise of standard precautions is that all body fluids have the potential to transmit any number of infectious diseases, both bacterial and viral. Certain basic principles must be followed to prevent direct and indirect transmission of these organisms. Nonsterile examination gloves should be worn when performing venipuncture, touching nonintact skin or mucous membranes of the patient or for touching any moist body fluid. This includes urine, stool, saliva, emesis, sputum, blood, and any type of drainage. Other personal protective equipment, such as face shields and protective gowns, should be worn whenever there is a risk of splashing body fluids into the face or onto clothing. This protects not only the healthcare worker, but also prevents any contamination that may be transmitted between patients via the caregiver. Specific control measures are aimed at specific routes of transmission. See Table 2-2 for examples of isolation precaution categories and the types of infections for which they are instituted.

TABLE 2-2. ISOLATION CATEGORIES AND RELATED INFECTION EXAMPLES

Other interventions to prevent nosocomial infections are similar regardless of the site. Maintaining glycemic control in both diabetic and nondiabetic patients may help decrease the patient’s risk for developing an infection. Invasive lines or tubes should never remain in place longer than absolutely necessary and never simply for staff convenience. Avoid breaks in systems such as urinary drainage systems and IV lines. Use of aseptic technique is essential if breaks into these systems are necessary. Hand washing before and after any manipulation of invasive lines is essential.

The current recommendation from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is that peripheral IV lines remain in place no longer than 72 to 96 hours. There is no standard recommendation for routine removal of central venous catheters when required for prolonged periods. If the patient begins to show signs of sepsis that could be catheter-related, these catheters should be removed. More important than the length of time the catheter is in place is how carefully the catheter was inserted and cared for while in place. All catheters that have been placed in an emergency situation should be replaced as soon as possible or within 48 hours. Dressings should be kept dry and intact and changed at the first signs of becoming damp, soiled, or loosened. IV tubing should be changed no more frequently than every 72 hours, with the exception of tubing for blood, blood products, or lipid-based products, each of which has specific criteria for how often the tubing should be changed.

Strategies to prevent hospital-acquired pneumonia in progressive care patients include the following for patients at high risk of aspiration, which is the primary risk factor: maintain the head of the bed at greater than or equal to 30°, assess residual volumes during enteral feeding and adjust feeding rates accordingly, and wash hands before and after contact with patient secretions or respiratory equipment (refer to chapters 5 and 14 for specific content related to these recommendations).

One of the most important defenses to preventing infection, though, is hand washing. Hand washing is defined by the CDC as vigorous rubbing together of lathered hands for 15 seconds followed by a thorough rinsing under a stream of running water. Particular attention should be paid around rings and under fingernails. It is best to keep natural fingernails well trimmed and unpolished. Cracked nail polish is a good place for microorganisms to hide.

Artificial fingernails should not be worn in any healthcare setting because they are virtually impossible to clean without a nailbrush and vigorous scrubbing. Hand washing should be performed prior to donning examination gloves to carry out patient care activities and after removing examination gloves. Washing should occur any time bare hands become contaminated with any wet body fluid and should be done before the body fluid dries. Once it dries, microorganisms begin to colonize the skin, making it more difficult to remove them. Use of alcohol-based waterless cleansers is convenient and effective when no visible soiling or contamination has occurred.

Dry, cracked skin, a long-standing problem associated with hand washing, has new significance with the emergence of blood-borne pathogens. Frequent hand washing, especially with antimicrobial soap, can lead to extremely dry skin. The frequent use of latex examination gloves has been associated with increased sensitivities and allergies, causing even more skin breakdown. All of this skin breakdown can put the healthcare provider at risk for blood-borne pathogen transmission, as well as for colonization or infection with bacteria. Attention to skin care is extremely important for the progressive care practitioner who is using antimicrobial soap and latex gloves frequently. Lotions and emollients should be used to prevent skin breakdown. If skin breakdown does occur, the employee health nurse should be consulted for possible treatment or work restriction until the condition resolves.

Skin breakdown is a major risk with progressive care patients due to immobility, poor nutrition, invasive lines, surgical sites, poor circulation, edema, and incontinence issues. Skin can become fragile and easily tear. Pressure ulcers can start to occur in as little as 2 hours. Healthy people constantly reposition themselves, even in their sleep, to relieve areas of pressure. Progressive care patients who cannot reposition themselves rely on caregivers to assist them. Pay particular attention to pressure points that are most prone to developing breakdown, namely, heels, elbows, coccyx, and occiput. When receiving progressive care patients following prolonged surgical procedures, ask the perioperative providers about the patient’s positioning during the procedure. This will help determine the need for close monitoring of the related pressure points for early indication of tissue injury. Also be cognizant of equipment that may contribute to breakdown, such as drainage tubes and even bed rails, if patients are positioned in constant contact with them. As the patient’s condition changes, so does the risk of developing a pressure ulcer. Assessing the patient’s risk routinely with a risk assessment tool alerts the caregiver to increasing or decreasing risk and therefore potential changes in interventions.

There are many simple interventions to maintain skin integrity: reposition the patient minimally every 2 hours, particularly if they are not spontaneously moving; use pressure-reduction mattresses for patients at high risk of breakdown; elevate heels off the bed using pillows placed under the calves or heel protectors; consider elbow pads; avoid long periods of sitting in a chair without repositioning; inflatable cushions (donuts) should never be used for either the sacrum or the head because they can actually cause increases in pressure on surrounding skin surfaces; and use a skin care protocol with ointment barriers for patients experiencing incontinence to prevent skin irritation and tissue breakdown.

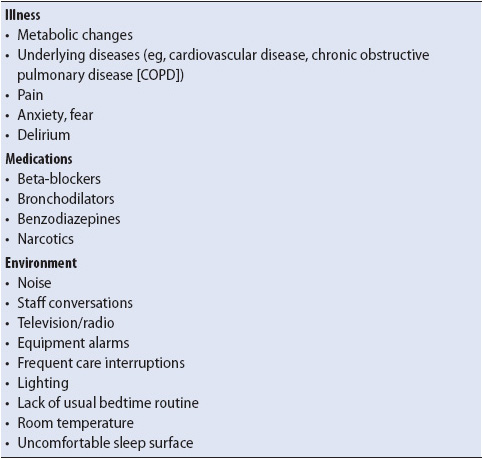

Progressive care patients are at risk for altered sleep patterns. Sleep is a problem for patients for many reasons, not the least of which are the pain and anxiety of an acute illness within an environment that is inundated with the multiple activities of healthcare providers. Table 2-3 identifies the many reasons for patients to experience sleep deprivation. The priority of sleep in the hierarchy of patient needs is often perceived to be low by clinicians. This contradicts patients’ own statements about the progressive care experience. Patients complain about lack of sleep as a major stressor along with the discomfort of unrelieved pain. The vicious cycle of undertreated pain, anxiety, and sleeplessness continues unless clinicians intervene to break the cycle with simple but essential interventions individualized to each patient.

TABLE 2-3. FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO SLEEP DISTURBANCES IN PROGRESSIVE CARE

Noise, lights, and frequent patient interruptions are common in many progressive care settings, with staff able to tune out the disturbances after they have worked in the setting for even a short period of time. Subjecting patients to these environmental stimuli and interruptions to rest/sleep can quickly lead to sleep deprivation. Psychological changes in sleep deprivation include confusion, irritability, and agitation. Physiologic changes include depressed immune and respiratory systems and a decreased pain threshold. Patients may already be sleep-deprived when they are transferred from a critical care unit to the progressive care setting. The progressive care unit routine can help start to reestablish a healing sleep pattern.

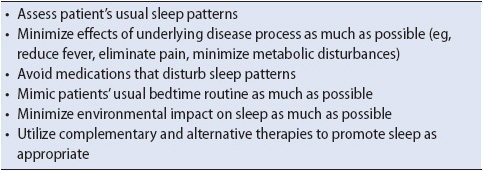

Enhancing patients’ sleep potential in the progressive care setting involves knowledge of how the environment affects the patient and where to target interventions to best promote sleep and rest. A nighttime sleep protocol where patients are closely monitored but untouched from 1 to 5 AM is an excellent example of eliminating the hourly disturbances that may have been occurring in the ICU. Encouraging blocks of time for sleep and careful assessment of the quantity and quality of sleep are important to patient well-being. The middle-of-the-night bath should not be a standard of care for any patient. Table 2-4 details basic recommendations for sleep assessment, protecting or shielding the patient from the environment, and modifying the internal and external environments of the patient. When these activities are incorporated into standard practice routines, progressive care patients receive optimal opportunity to achieve sleep.

TABLE 2-4. EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE: SLEEP PROMOTION IN PROGRESSIVE CARE

Keys to maintaining psychological integrity during an acute illness include keeping stressors at a minimum; encouraging family participation in care; promoting a proper sleep-wake cycle; encouraging communication, questions, and honest and positive feedback; empowering the patient to participate in decisions as appropriate; providing patient and family education about unit expectations and rules, procedures, medications, and the patient’s physical condition; ensuring pain relief and comfort; and providing continuity of care providers. It is also important to have the patient’s usual sensory and physical aids available, such as glasses, hearing aids, and dentures, as they may help prevent confusion. Encourage the family to bring something familiar or personal from home, such as a family or pet picture.

Delirium is evidenced by disorientation, confusion, perceptual disturbances, restlessness, distractibility, and sleep-wake cycle disturbances. Any prior LOS in an ICU may have already resulted in, or put a patient at risk for, development of confusion. Causes of confusion are usually multifactorial and include metabolic disturbances, polypharmacy, immobility, infections (particularly urinary tract and upper respiratory infections), dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, sensory impairment, and environmental challenges. Treatment of delirium is a challenge and therefore prevention is ideal.

Delirium is most common in postsurgical and elderly patients and is the most common cause of disruptive behavior in progressive care. It is not unusual for providers to suspect delirium when acutely ill patients are confused and restless, however in reality there are several different subtypes of delirium: hyperactive (restlessness, agitation, irritability, aggression); hypoactive (slow response to verbal stimuli, psychomotor slowing); and mixed delirium (both hyperactive and hypoactive behaviors). Assessment of delirium should be routine in the progressive care unit, and there are several valid and reliable tools that can be used to identify delirium.

Often mislabeled as psychosis, delirium is not psychosis. Sensory overload is a common risk factor that contributes to delirium in the acutely ill. Medications that may also play a role in instigating delirium include prochlorperazine, diphenhydramine, famotidine, benzodiazepines, opioids, and antiarrhythmic medications.

Medication for managing delirious behavior is best reserved for those cases in which behavioral interventions have failed. Sedative-hypnotics and anxiolytics may have precipitated the delirium and can exacerbate the sleep-wake cycle disturbances causing more confusion. The agitated patient may require low-dose neuroleptics or short-acting benzodiazepines. Restraints are discouraged because they tend to increase agitation.

External stimulation should be minimized and a quiet, restful, well-lit room maintained during the day. Consistency in care providers is also important. Repeating orientation cues minimizes fear and confusion; for example, “Good morning Bill, my name is Sue. It’s Monday morning in April and you are in the hospital. I’m a nurse and will stay here with you.” Background noise from a television or radio often increases anxiety as the patient has trouble processing the noise and content. Explain all procedures and tests concretely. Introduce one idea at a time, slowly, and have the patient repeat the information. Repeat and reinforce as often as needed.

If the patient demonstrates a paranoid element in his or her delirium, avoid confrontation and remain at a safe distance. Accept bizarre statements calmly, with a nod, but without agreement. Explain to the family that the behaviors are symptoms that will most likely resolve with time, resumption of normal sleep patterns, and medication. Delirious patients usually remember the events, thoughts, conversations, and provider responses that occur during delirium. The recovered patients may be embarrassed and feel guilty if they were combative during their illness.

Depression occurring with a medical illness affects the long-term recovery outcomes by lengthening the course of the illness, and increasing morbidity and mortality. Risk factors that predispose for depression with medical disorders include social isolation, recent loss, pessimism, financial pressures, history of mood disorder, alcohol or substance abuse/withdrawal, previous suicide attempts, and pain. Many patients arrive in the hospital with a history of treatment for depression which can be exacerbated by a critical illness crisis. It is important that healthcare providers don’t forget to maintain the patient’s psychiatric medication regimen if at all possible in order to avoid worsening of the patient’s psychological status.

Educating the patient and family about the temporary nature of most depressions during acute illness assists in providing reassurance that this is not an unusual phenomenon. Severe depressive symptoms often respond to pharmacologic intervention, so a psychiatric consultation may be warranted. Keep in mind that it may take several weeks for antidepressants to reach their full effectiveness. If you suspect a person is depressed, ask directly. Allow the patient to initiate conversation. If negative distortions about illness and treatment are communicated, it is appropriate to correct, clarify, and reassure with realistic information to promote a more hopeful outcome. Consistency in care providers promotes trust in an ongoing relationship and enhances recovery.

A patient who has attempted suicide or is suicidal can be frightening to hospital staff. Staff members are often uncertain of what to say when the patient says, “I want to kill myself … my life no longer has meaning.” Do not avoid asking if the person is feeling suicidal; you do not promote suicidal thoughts by asking the question. Many times the communication of feeling suicidal is a cover for wanting to discuss fear, pain, or loneliness. A psychiatric referral is recommended in these situations for further evaluation and intervention.

Medical disorders can cause anxiety and panic-like symptoms, which are distressing to the patient and family and may exacerbate the medical condition. Treatment of the underlying medical condition may decrease the concomitant anxiety. Both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions can be helpful in managing anxiety during acute illness. Pharmacologic agents for anxiety are discussed in Chapter 6 (Pain and Sedation Management) and Chapter 7 (Pharmacology). Goals of pharmacologic therapy are to titrate the drug dose so that the patient can remain cognizant and interactive with staff, family, and environment; to complement pain control; and to assist in promoting sleep. There are also a variety of nonpharmacologic interventions to decrease or control anxiety:

• Breathing techniques: These techniques target somatic symptoms and include deep and slow abdominal breathing patterns. It is important to demonstrate and do the breathing with patients, as their heightened anxiety decreases their attention span. Practicing this technique may decrease anxiety and assist the patient through difficult procedures.

• Muscle relaxation: Reduce psychomotor tension with muscle relaxation. Again, the patient will most likely be unable to cue himself or herself, so this is an excellent opportunity for the family to participate as the cuing partner. Cuing might be, “The mattress under your head, elbow, heel, and back feels heavy against your body, press harder, and then try to drift away from the mattress as you relax.” Commercial relaxation tapes are available but are not as useful as the cuing by a familiar voice.

• Imagery: Interventions targeting cognition, such as imagery techniques, depend on the patient’s capacity for attention, memory, and processing. Visualization imagery involves recalling a pleasurable, relaxing situation; for example, a hot bath, lying on a warm beach, listening to waves, or hearing birds sing. Guided imagery and hypnosis are additional therapies, but require some competency to be effective; thus, a referral is suggested. Patients who practice meditation as an alternative for stress control should be encouraged to continue, but the environment may need modification to optimize the effects.

• Preparatory information: Providing the patient and family with preparatory information is extremely helpful in controlling anxiety. Allowing the patient and family to control some aspects of the illness process, even if only minor aspects of care, can be anxiolytic.

• Distraction techniques: Distraction techniques can also interrupt the anxiety cycle. Methods for distracting can be listening to familiar music or humorous tapes, watching videos, or counting backward from 200 by 2 rapidly.

• Use of previous coping methods: Identify how the patient and family have dealt with stress and anxiety in the past and suggest that approach if feasible. Supporting previous coping techniques may well be adaptive.

Patient and family education in the progressive care environment is essential to providing information regarding diagnosis, prognosis, treatments, and procedures. In addition, education provides patients and family members a mechanism by which fears and concerns can be put in perspective and confronted so that they can become active members in the decisions made about care.

Providing patient and family education in acute care is challenging; multiple barriers (eg, environmental factors, patient stability, patient and family anxiety) must be overcome or adapted to provide this essential intervention. The importance of education, coupled with the barriers common in progressive care, necessitates that education be a continuous ongoing process engaged in by all members of the team.

Education in the progressive care setting is most often done informally, though some patients may be able to tolerate limited sessions in a classroom setting. Education of the patient and family can often be subtle, occurring with each interaction between the patient, family, and members of the healthcare team. Education may also now be more direct, particularly in relation to self-care or managing equipment at home.

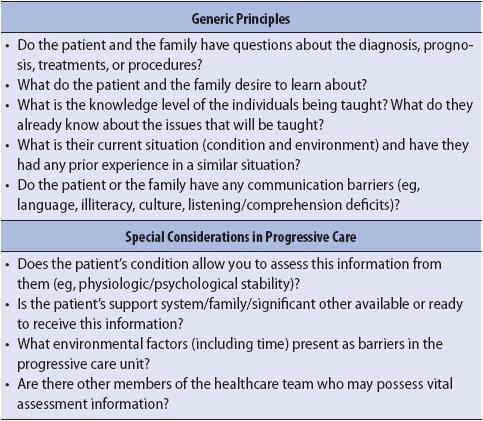

Assessment of the patient’s and family’s learning needs should focus primarily on learning readiness. Learning readiness refers to that moment in time when the learner is able to comprehend and synthesize the shared information. Without learning readiness, teaching may not be useful. Questions to assess learning readiness are listed in Table 2-5.

TABLE 2-5. ASSESSMENT OF LEARNING READINESS

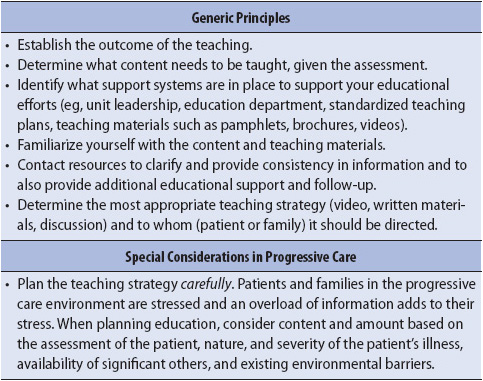

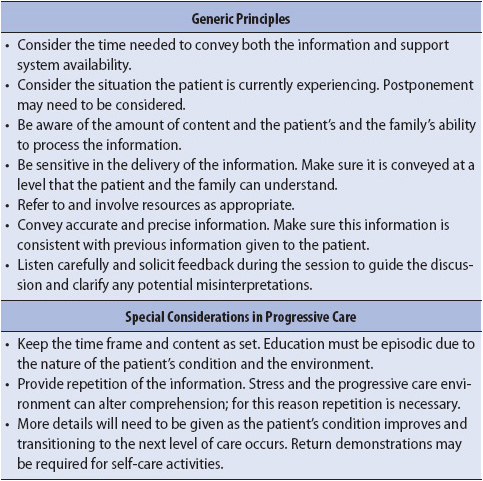

Prior to teaching, the information gathered in the assessment is prioritized and organized into a format that is meaningful to the learner (Table 2-6). Next, the outcome of the teaching is established along with appropriate content, and then a decision should be made about how to share the information. The next step is to teach the patient, family, and significant others (Table 2-7). Although this phase often appears to be the easiest, it is actually the most difficult. It is crucial during the communication of the content, regardless of the type of communication vehicle used (video, pamphlet, discussion), to listen carefully to the needs expressed by the learner and to provide clear and precise responses to those needs.

TABLE 2-6. PRINCIPLES FOR TEACHING PLANS

TABLE 2-7. PRINCIPLES FOR EDUCATIONAL SESSIONS

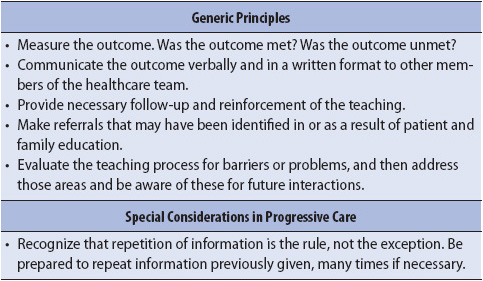

Following educational interventions, it is essential to determine if the educational outcomes have been achieved (Table 2-8). Even if the outcome appears to have been achieved, it is not unusual that the learners may not retain all the information. Patients and families experience a great deal of stress while in the acute care environment; reinforcement is often necessary and should be anticipated.

TABLE 2-8. PRINCIPLES FOR EDUCATIONAL OUTCOME MONITORING

There is a strong evidence base to support that family presence and involvement in the progressive care unit aids in the recovery of progressive care patients. Family members can help patients cope, reduce anxiety, and provide a resource for the patient. Families, however, also need support in maintaining their strength and having needs met to be able to function as a positive influence for the patient rather than having a negative impact.

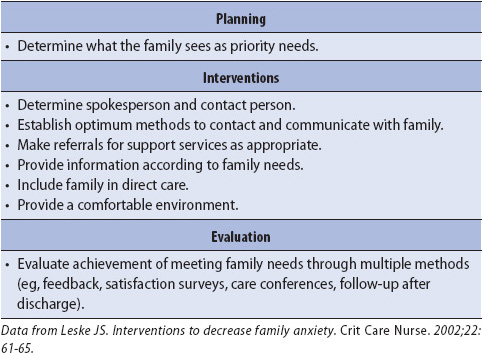

Developing a partnership with the family and a trusting relationship is in everyone’s best interest so that optimal functioning can occur. Research shows that there can frequently be disagreement between the nurse and family perspectives about the type or priorities of family needs. Therefore, it is important to discuss family needs and perceptions directly with each family and tailor interventions based on those needs (Table 2-9).

TABLE 2-9. EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE: FAMILY INTERVENTIONS

Research has consistently identified five major areas of family needs (receiving assurance, remaining near the patient, receiving information, being comfortable, and having support available). These and the importance of unrestricted family visitation are addressed next.

Family members need reassurance that the best possible care is being given to the patient. This instills confidence and a sense of security for the family. It can also assist in either maintaining hope or can be helpful in redefining hope to a more realistic image when appropriate.

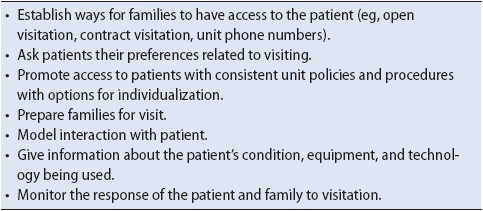

Family members need to have consistent access to their loved one. Of primary importance to the family is the unit visiting policy. Specifics to be discussed include the number of visitors allowed at one time, age restrictions, visiting times if not flexible or open, and how to gain access to the unit (Table 2-10). There is increasing evidence to support the presence of a family member with the patient during invasive procedures, as well as during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Although this practice may still be controversial, family members have reported a sense of relief and gratitude at being able to remain close to the patient. It is recommended that written policies be developed through an interdisciplinary approach prior to implementing family presence at CPR or procedures.

TABLE 2-10. EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE: FAMILY VISITATION IN PROGRESSIVE CARE

Communication with the patient and family should be open and honest. Clinicians should keep promises (be thoughtful about what you promise), describe expectations, not contract for secrets or elicit care provider preferences, should apologize for inconveniences and mistakes, and maintain confidentiality. Concise, simplistic explanations without medical jargon or alphabet shorthand facilitate understanding. Contact interpreters, as appropriate, when language barriers exist.

Evaluate your communication by asking the patient and family for their understanding of the message you sent and its content and intent. When conflict occurs, find a private place for discussion. Avoid taking the confrontation personally. Ask yourself what the issue is and what needs to occur to reach resolution. If too much emotion is present, agree to address the issue at a later time, if possible.

It is helpful to establish a communication tree so that one family member is designated to be called if there are changes in the patient’s condition. Establish a time for that person to call the unit for updates. Reassure them you are there to help or refer them to other system supports. Unit expectations and rules can be conveyed in a pamphlet for the family to refer to over time. Content that is helpful includes orientation about the philosophy of care; routines such as shift changes and physician rounds; the varied roles of personnel who work with patients; and comfort information such as food services, bathrooms, waiting areas, chapel services, transportation, and lodging. Clarify what they see and hear. Mobilize resources and include them in patient care and problem solving, as appropriate. Some progressive care units invite family members to medical rounds for the discussion of their loved ones. Adequate communication can decrease anxiety, increase a sense of control, and assist in improving decision making by families.

There should be space available in or near the progressive care unit to meet comfort needs of the family. This should include comfortable furniture, access to phones and restrooms, and assistance with finding overnight accommodations. Encourage the family to admit when they are overwhelmed, take breaks, go to meals, rest, sleep, take care of themselves, and not to abandon members at home. Helping the family with basic comfort needs helps decrease their distress and maintain their reserves and coping mechanisms. This improves their ability to be a valuable resource for the patient.

Utilize all potential resources in meeting family needs. Relying on nurses to fulfill all family needs while they are also trying to care for a progressive care patient can create tension and frustration. Assess the family for their own resources that can be maximized. Utilize hospital referrals that can assist in family support such as chaplains, social workers, and child-family life departments.

There is an abundance of evidence demonstrating that unrestricted access of the patient’s support network (family, significant others, trusted friends) can be beneficial to the patient by providing emotional and social support; conveying the patient’s wishes when he or she is unable to speak for self, improving communication, and improving patient and family satisfaction. However, many hospitals continue to have policies that restrict visitation. There are certainly individual circumstances where open visiting can be ill-advised due to medical, therapeutic, or safety considerations (eg disruptive behavior, infectious disease concerns, patient privacy, or per patient request). On admission to the progressive care unit, the patient should be asked to identify their “family” and their visiting preferences, and care providers should partner with the patient and family to accommodate those preferences while meeting safety, privacy, and decision-making needs.

For the family, the progressive care setting symbolizes a variety of hopes, fears, and beliefs that range from hope of a cure to end-of-life care. A family-focused approach can promote coping and cohesion among family members and minimize the isolation and anxiety for patients. Anticipating family needs, focusing on the present, fostering open communication, and providing information are vital to promoting psychological integrity for families. By using the event of hospitalization as a point of access, progressive care clinicians assume a major role in primary prevention and assisting families to cope positively with crisis and grow from the experience.

Preventing common complications and maintaining physiologic and psychosocial stability is a challenge even when in the controlled environment of the progressive care unit. It is even more challenging when the need for transporting the progressive care patient to other areas of the hospital is necessary for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. The decision to transport the progressive care patient out of the well-controlled environment of the progressive care unit elicits a variety of responses from clinicians. It’s not uncommon to hear phrases like these: “What if something happens en route?” “Who will take care of my other patients while I’m gone?” Responses like these underscore the clinician’s understanding of the risks involved in transporting progressive care patients.

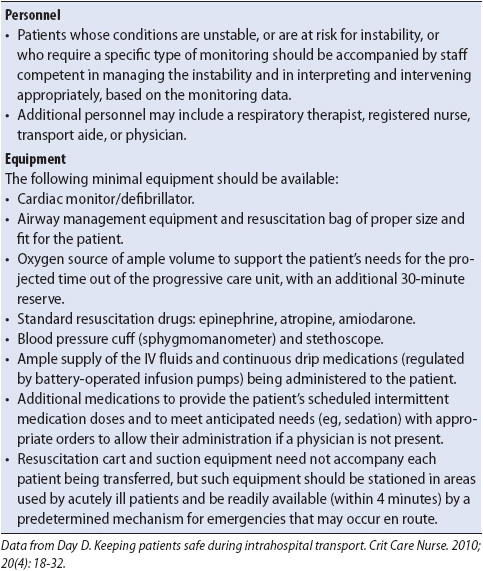

Transporting a progressive care patient involves more than putting the patient on a stretcher and rolling him or her down the hall. Safe patient transport requires thoughtful planning, organization, and interdisciplinary communication and cooperation. The goal during transport is to maintain the same level of care, regardless of the location in the hospital. The transfer of progressive care patients always involves some degree of risk to the patient. The decision to transfer, therefore, should be based on an assessment of the potential benefits of transfer and be weighed against the potential risks.

The reason for moving a progressive care patient is typically the need for care, technology, or specialists not available in the progressive care unit. Whenever feasible, diagnostic testing or simple procedures should be performed at the patient’s bedside within the progressive care unit. If the diagnostic test or procedural intervention under consideration is unlikely to alter management or outcome of the patient, then the risk of transfer may outweigh the benefit. It is imperative that every member of the healthcare team assists in clarifying what, if any, benefit may be derived from transport.

Prior to initiating transport, a patient’s risk for development of complications during transport should be systematically assessed. The switching of technologies in the progressive care unit to portable devices may lead to undesired physiologic changes. In addition, complications may arise from environmental conditions outside the progressive care unit that are difficult to control, such as body temperature fluctuations or inadvertent movement of invasive devices (eg, tracheostomies, chest tubes, IV devices). Common complications associated with transportation are summarized in Table 2-11.

TABLE 2-11. POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS DURING TRANSPORT

Maintaining adequate ventilation and oxygenation during transport is a challenge. Patients who are not intubated prior to their transfer are at risk for developing airway compromise. This is particularly a problem in patients with decreased levels of consciousness. Continuous monitoring of airway patency is critical to ensure rapid implementation of airway strategies, if necessary.

Hypoventilation or hyperventilation can result in pH changes, which may lead to deficits in tissue perfusion and oxygenation. Therefore, respiratory and nursing personnel who are properly trained in the mechanisms of unique ventilatory requirements need to provide ventilation during transport. Patients requiring continuous bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) or high-flow oxygen may experience changes in respiratory status during transport. The percentage of inspired oxygen (FiO2) may need to be increased during transport. Increasing the FiO2 for any patient requiring transfer may help avoid other complications from hypoxia. Ensuring the appropriate portable equipment to maintain adequate oxygenation may be complex but imperative. The patient’s special respiratory equipment may also be transported to the destination so that he or she can be placed back on the equipment during the procedure.

Whether related to their underlying disease processes or the anxiety of being taken out of a controlled environment, the potential for cardiovascular complications exists in all patients being transported. These complications include hypotension, hypertension, arrhythmias, tachycardia, ischemia, and acute pulmonary edema. Many of these complications can be avoided by adequate patient preparation with pharmacologic agents to maintain hemodynamic stability and manage pain and anxiety. Continuous infusions should be carefully maintained during transport, with special attention given to IV lines during movement of the patient from one surface to another. Additional emergency equipment may need to be taken on the transport such as hand pumps for patients on ventricular assist devices.

The potential for respiratory and cardiovascular changes during transport increases the risk for cerebral hypoxia, hypercarbia, and intracranial pressure (ICP) changes. Patients with high baseline ICP may require additional interventions to stabilize cerebral perfusion and oxygenation prior to transport (eg, hyperventilation, increased partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood [PaO2], blood pressure control). In addition, patients with suspected cranial or vertebral fractures are at high risk for neurologic damage during repositioning from bed to transport carts or diagnostic tables. Proper immobilization of the spine is imperative in these situations, as is the avoidance of unnecessary repositioning of the patient. Positioning the head in the midline position with the head of the bed elevated, when not contraindicated, may decrease the risk of increases in ICP.

Gastrointestinal (GI) complications may include nausea or vomiting, which can threaten the patient’s airway, as well as cause discomfort. Premedicating patients at risk for GI upset with an H2-blocker, proton pump inhibitor or an antiemetic as appropriate may be helpful. For patients with large volume nasogastric (NG) drainage, preparations to continue NG drainage during transportation or in the destination location may be necessary.

The level of pain experienced by the patient is likely to be increased during transport. Many of the diagnostic tests and therapeutic interventions in other hospital departments are uncomfortable or painful. Anxiety associated with transport may also increase the level of pain. Additional analgesic or anxiolytic agents, or both may be required to ensure adequate pain and anxiety management during the transport process. Keeping the patient and family members well informed is also helpful in decreasing anxiety levels.

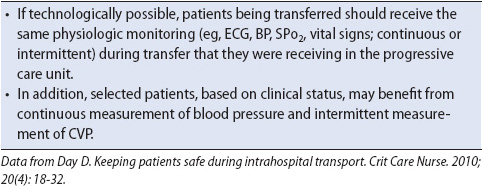

During transport, there should be no interruption in the monitoring or maintenance of the patient’s vital functions. The equipment used during transport as well as the skill level of accompanying personnel must be equivalent with the interventions required or anticipated for the patient while in the progressive care unit (Table 2-12). Intermittent and continuous monitoring of physiologic status (eg, cardiac rhythm, blood pressure, oxygenation, ventilation) should continue during transport and while the patient is away from the progressive care unit (Table 2-13).

TABLE 2-12. TRANSPORT PERSONNEL AND EQUIPMENT REQUIREMENTS

TABLE 2-13. MONITORING DURING TRANSFER

Questions that need to be answered to prepare for transfer include the following:

• What is the current level of care (equipment, personnel)?

• What will be needed during the transfer or at the destination to maintain that level of care?

• What additional therapeutic interventions may be required before or during transport (eg, pain and sedation medications or titration of infusions)?

• Do I have all the necessary equipment needed in the event of an emergency during the transport?

If you are unsure what capabilities exist at the destination, call the receiving area in advance to ask about their support capabilities; for example, are there adequate outlets to plug in electrical equipment rather than continuing to use battery power, do they have capability for high levels of suction pressure if needed, or what specialty instructions need to be followed in magnetic resonance imaging? Will they be ready to take the patient immediately into the procedure with no waiting?

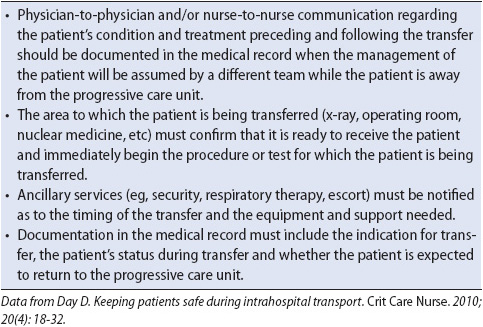

Before transfer, the plan of care for the patient during and after transfer should be coordinated to ensure continuity of care and availability of appropriate resources (Table 2-14). The receiving units should be contacted to confirm that all preparations for the patient’s arrival have been completed. Communication, both written and verbal, between team members should delineate the current status of the patient, management priorities, and the process to follow in the event of untoward events (eg, unexpected hemodynamic instability or airway problems).

TABLE 2-14. PRETRANSFER COORDINATION AND COMMUNICATION

After you have assessed the patient’s risk for transport complications, the patient should be prepared for transfer, both physically and mentally. As you are organizing the equipment and monitors, explain the transfer process to the patient and family. The explanation should include a description of the sensations the patient may expect, how long the procedure should last, and the role of individual members of the transport team. It is important to allay any patient or family anxiety by identifying current caregivers who will accompany the patient during transport. The availability of emergency equipment and drugs and how communication is handled during transportation also may be information that will reassure the patient and family.

Once preparations are complete, the actual transfer can begin. Ensure that the portable equipment has adequate battery life to last well beyond the anticipated transfer time in case of unanticipated delays. Connect each of the portable monitoring devices prior to disconnection from the bedside equipment, if possible. This enables a comparison of vital sign values with the portable equipment.

Once vital sign measurement equipment and noninvasive oxygenation monitors are in place and values verified, disconnect the patient from the bedside oxygen source and begin portable oxygenation. Assess for clinical signs and symptoms of respiratory distress and changes in ventilation and oxygenation. It may be easier to transfer the patient on the bed if it will fit in elevators and spaces in the receiving area. Check IV lines, pressure lines, monitor cables, NG tubes, chest tubes, urinary catheters, or drains of any sort to ensure proper placement during transport and to guard against accidental removal during transport.

During transport, the progressive care nurse is responsible for continuous assessment of cardiopulmonary status (ie, electrocardiograph, blood pressures, respiration, oxygenation) and interventions as required to ensure stability. Throughout the time away from the progressive care environment, it is imperative that vigilant monitoring occurs regarding the patient’s response not only to the transport, but also to the procedure or therapeutic intervention. Alterations in drug administration, particularly analgesics, sedatives, and vasoactive drugs, are frequently needed during the time away from the progressive care unit to maintain physiologic stability. Documentation of assessment findings, interventions, and the patient’s responses should continue throughout the transport process.

Following return to the progressive care unit, monitoring systems and interventions are reestablished and the patient is completely reassessed. Often, some adjustment in pharmacologic therapy or oxygen support is required following transport. Allowing for some uninterrupted time for the family to be at the patient’s bedside and for patient rest is another important priority following return to the unit. Documentation of the patient’s overall response to the transport situation should be included in the medical record.

Interfacility patient transfers, although similar to transfers within a hospital, can be more challenging. The biggest differences between the two are the isolation of the patient in the transfer vehicle, limited equipment and personnel, and a high complication rate due to longer transport periods and inability to control environmental conditions (eg, temperature, atmospheric pressure, sudden movements), which may cause physiologic instability.

The primary consideration in interfacility transfer is maintaining the same level of care provided in the progressive care unit. Accordingly, the mode of transfer should be selected with this in mind. The resources available in the sending facility must be made as portable as possible and must accompany the patient; for example, ventricular assist devices must be continued without interruption. This requirement often challenges progressive care practitioners’ skills and abilities, as well as the equipment resources necessary to ensure a safe transport.

Planning for transitioning of the patient to the next stage of care (eg, transfer from progressive care to rehabilitation) should begin soon after the patient is admitted to the progressive care unit. It involves assessing minimally where and with whom the patient lives, what external resources were being used prior to admission, and what resources are anticipated to be required on transfer out of the progressive care unit. Complex patients require extensive preplanning in achieving a successful transition. As the patient stabilizes and improves, the thought of leaving the progressive care unit can be frightening as it is perceived as moving to a level of care where there are fewer staff to monitor the patient. Reinforce the positive aspect of planning for the transition in that it is a sign that the patient is improving and making progress.

If the patient is transferring to another institution, such as an acute or subacute rehabilitation facility, consider having the family visit the facility prior to transfer. This gives them an opportunity to meet the new caregivers, ask any questions they may have, and be a positive influence to alleviate anxiety the patient may be experiencing about the transfer.

If the transfer is internal to another patient care unit and the patient’s care is complex, consider working with the receiving unit staff in advance to inform them of the anticipated plan of care and any patient preferences. Identify a primary nurse in advance from the receiving unit, if possible, who may be able to take the time to meet the patient before the transfer. Clinical nurse specialists or nurse managers may also be able to meet the patient and family, describe the receiving unit, and act as a resource after the transfer, again giving a sense of control to the patient and family.

Transitioning of care also includes planning care for the patient who is dying. Caring for the dying patient and his or her family can be the most rewarding challenge. The use of advance directives provides a means for the acutely ill patient to communicate wishes regarding end-of-life issues. A dialogue with the patient about end-of-life care is an appropriate avenue for discussing values and beliefs associated with dying and living. Hopefully, discussions prior to a traumatic event or progressive care admission have occurred so the patient is empowered to institute stopping or continuing life-support measures and has designated a surrogate decision maker. If advance directives are in place, then advocating for those wishes and promoting comfort are primary responsibilities of clinicians. If previous discussions have not taken place, as with an unexpected traumatic accident, then requesting system resources to assist the family while you attend to the patient’s critical needs is appropriate. Providing for clergy to assist with spiritual needs and rituals also can help the family to cope with the crisis.

It is important to have an awareness of your own philosophical feelings about death when caring for dying persons. Be genuine in your care, touch, and presence, and do not feel compelled to talk. Take your cue from the patient. Crying or laughing with the patient and family is an acknowledgment of humanness—an existential relationship and a rare gift in a unique encounter.

Agard AS, Lomberg K. Flexible family visitation in the intensive care unit: nurses’ decision making. J Clin Nurs. 2010;20:1106-1114.

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. AACN practice alert. Family presence: visitation in the adult ICU. 2011. Available at http://www.aacn.org/WD/practice/docs/practicealerts/family-visitation-adult-icu-practicealer. Accessed February 18, 2013.

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. The AACN Synergy Model for patient care. Aliso Viejo, CA: AACN. Available at http://www.aacn.org/WD/Certifications/Content/synmodel.content?menu=Certification. Accessed February 18, 2103.

DeCourcey M, Russell AC, Keister KJ. Animal-assisted therapy. Evaluation and implementation of a complementary therapy to improve the psychological and physiological health of critically ill patients. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2010;29(5):211-214.

Duran DR, Oman KS, Abel JJ, Koziell VM, Szymanski D. Attitudes toward and beliefs about family presence: a survey of healthcare providers, patients’ families, and patients. Am J Crit Care. 2007;16(3):270-282.

Hoghaug G, Fagermoen MS. Lerdal A. The visitor’s regard of their need for support, comfort, information, proximity, and assurance in the intensive care unit. Inten and Crit Care Nurs. 2012;28(6):263-268.

Obringer K, Hilgenberg C, Booker K. Needs of adult family members of intensive care unit patients. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(11-12):1651-1658.

Whitcomb J, Roy D, Blackman VS. Evidence-based practice in a military intensive care unit family visitation. Nurs Res. 2010;59(1):S32-S39.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Improving surveillance for ventilator-associated events in adults. Overview and proposed new definition algorithm. Available at www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/vae/CDC_VAE_CommunicationSummary-for-compliance_20120313.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2013.

Bennett JV, Brockmann PS, eds. Hospital Infections. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

Gould CV, Umscheid CA, Argawal RK, et al. Guideline for prevention of catheter-related urinary tract infections, 2009. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/cauti/001_cauti.html. Accessed February 18, 2013.

O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections, 2011. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/BSI/BSI=guidelines-2100.html. Accessed February 18, 2013.

Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, et al. Management of multidrug-resistant organisms in healthcare settings, 2006. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/mdro/mdro_0.html. Accessed February 18, 2103.

Wenzel RP, ed. Prevention and Control of Nosocomial Infections. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 2002.

Rankin SH, Stallings KD, London E. Patient Education in Health and Illness. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

Redman BK. The Practice of Patient Education. 10th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby-Elsevier; 2006.

Gorman LM, Sultan DF. Psychosocial Nursing for General Patient Care. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis Co; 2008.

ICU Delirium and Cognitive Impairment Study Group. Vanderbilt University. http://www.icudelirium.org/. Accessed June 1, 2009.

Neufeld KJ, Bienvenu OJ, Rosenberg PB, et al. The Johns Hopkins Delirium Consortium: a model for collaborating across disciplines and departments for delirium prevention and treatment. JAGS. 2011;59:S244-S248.

Olson T. Delirium in the intensive care unit: role of the critical care nurse in early detection and treatment. Dynamics. 2012;23(4):32-36.

Sendelbach S, Guthrie PF, Schoenfelder DP. Acute confusion/delirium. Identification, assessment, treatment, and prevention. J Gerontol Nurs. 2009;35(11):11-18.

Friese RS. Sleep and recovery from critical illness and injury: a review of theory, current practice, and future directions. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(3):697-705.

Jones C, Dawson D. Eye masks and earplugs improve patient’s perception of sleep. Crit Care Nurs. 2012;17(5):247-254.

Patel M, Chipman J, Carlin BW, Shade D. Sleep in the intensive care unit setting. Crit Care Nurse Q. 2008;31(4):309-320.

Day D. Keeping patients safe during intrahospital transport. Crit Care Nurs. 2010;30(4):18-32.

Warren J, Fromm RE, Orr RA, et al. Guidelines for the inter- and intrahospital transport of critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:256-262.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Preventing pressure ulcers in hospitals: a toolkit for improving quality of care. Available at www.ahrq.gov/research/ltc/pressureulcertoolkit/putool3a.html. Accessed February 18, 2103.

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. AACN practice alert. Ventilator associated pneumonia. Aliso Viejo, CA: AACN. Available at http://www.aacn.org/WD/Practice/Docs/PracticeAlerts/ventilator%20Associated%20Pneumonia%201-2008.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2013.

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Protocols for Practice: Creating Healing Environments. 2nd ed. Aliso Viejo, CA: AACN; 2007.

Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):263-306.

Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Piolo GF, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. 8th ed. CHEST. 2008;133(suppl 6):381S-453S.

Sedwick MB, Lance-Smith M, Reeder SJ, Nardi J. Using evidence-based practice to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care Nurse. 2012;32(4):41-50.

Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nurses Society. Guidelines for Prevention and Management of Pressure Ulcers. Glenview, IL: WOCN; 2010.