Email is a fast, cheap, convenient communication medium. In fact, these days, anyone who doesn’t have an email address is considered some kind of freak.

If you do have an email address or two, you’ll be happy to discover that Mac OS X includes Mail, a program that lets you get and send email messages without having to wade through a lot of spam (junk mail). Mail is a surprisingly complete program, substantially speeded up for Mac OS 10.6, and it’s filled with shortcuts and surprises around every turn.

And this desktop post office offers more than just mail—among other things, you can also use the program as a personal notepad and a newsreader for your favorite Web sites.

Not bad for a freebie, eh?

What you see the first time you open Mail may vary. If you’ve signed up for a MobileMe account (and typed its name into the MobileMe pane of System Preferences), then you’re all ready to go; you see the main Mail window full of messages. If you don’t get the offer to set up an account, choose File→Add Account to jump-start the process. (That’s also how you add other accounts later.)

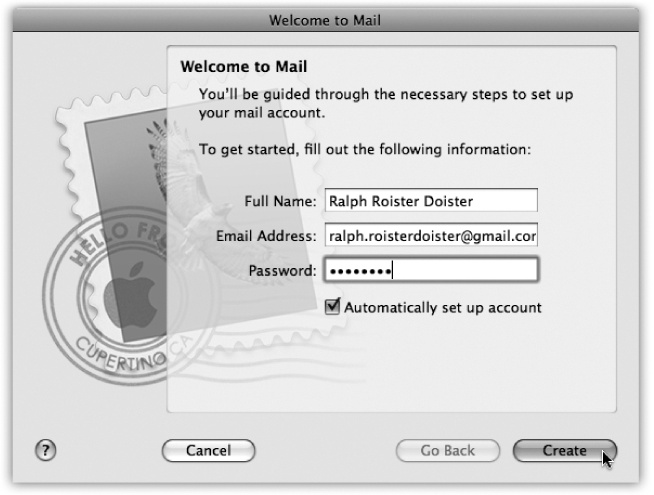

If you get your mail from some other service provider, like Verizon, Comcast, Gmail, Yahoo, or whatever, Mail setup is almost as easy. Apple has rounded up the acronym-laden server settings for 30 popular mail services and built them right in.

All you have to do is type your email name and password into the box (Figure 19-1). If Mail recognizes the suffix (for example, @gmail.com), and if “Automatically set up account” is turned on, then Mail does the heavy lifting for you.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: If you work in a company that uses Microsoft’s Exchange networked mail/calendar system, the good news rolls on. Just entering your email address and password is usually enough to connect to the corporate email system. For details and caveats, see Life with Microsoft Exchange.

Figure 19-1. Mail takes the pain, agony, and acronyms out of setting up an email account on your Mac. Forget about remembering your SMTP server address (or even what SMTP stands for), and just type your email address and password into the box. If you use a mainstream mail service like Gmail, Hotmail, Yahoo, Comcast, or Verizon, Mail configures your account settings automatically after you click the Create button.

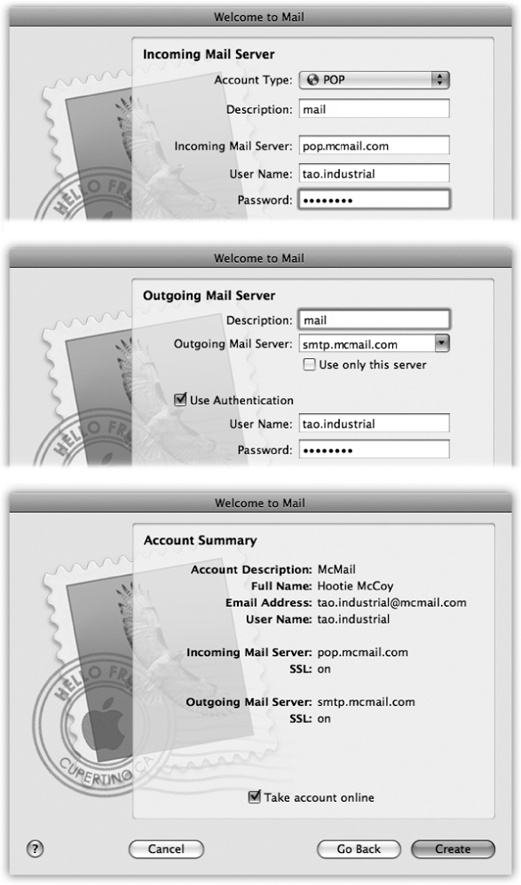

Now, if you use a service provider that Mail doesn’t recognize when you type in your email name and password—you weirdo—then you have to set up your mail account the long way. Mail prompts you along, and you confront the dialog boxes shown in Figure 19-2, where you’re supposed to type in various settings to specify your email account. Some of this information may require a call to your Internet service provider (ISP).

Here’s the rundown:

Account Type is where you specify what flavor of email account you have. See the box on POP, IMAP, Exchange, and Web-based Mail for details; check with your ISP if you’re not sure which type you have.

Account Description is for your reference only. If you want an affectionate nickname for your email account, type it here.

Full Name (shown in Figure 19-1) will appear in the “From:” field of any email you send. Type it just the way you’d like it to appear.

Figure 19-2. These dialog boxes let you plug in the email settings provided by your Internet service. If you want to add another email account later, choose File→Add Account, and then enter your information in the resulting dialog box. (Or, if you like doing things the hard way, choose Mail→Preferences→Accounts tab, click the

in the lower-left corner of the window, and then enter your account information in the fields on the right.)

in the lower-left corner of the window, and then enter your account information in the fields on the right.)Email Address is the address you were assigned when you signed up for Internet services, such as billg@microsoft.com.

Incoming Mail Server, Outgoing Mail Server are where you enter the information your ISP gave you about its mail servers. Usually, the incoming server is a POP3 server, and its name is related to the name of your ISP, such as popmail.mindspring.com. The outgoing mail server (also called the SMTP server) usually looks something like mail.mindspring.com.

User Name, Password. Enter the name and password provided by your ISP. (Often, they’re the same for both incoming and outgoing servers.)

Click Continue when you’re finished.

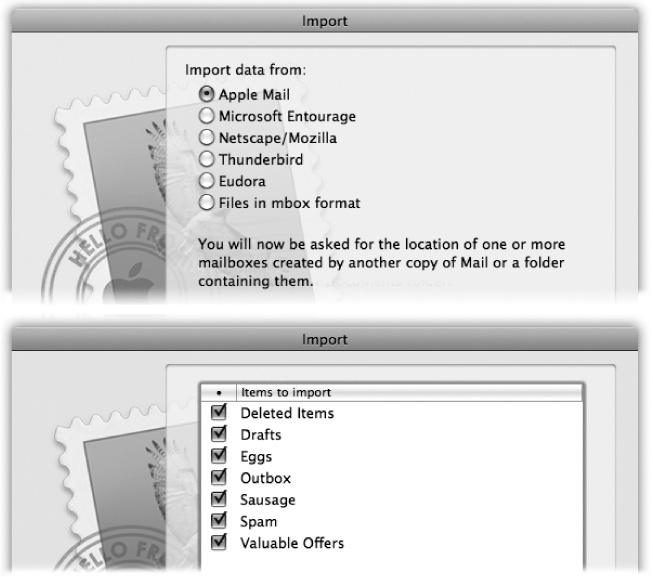

Mail can also import your email collection from an email program you’ve used before—Entourage, Thunderbird, Netscape/Mozilla, Eudora, or even a version of Mac OS X Mail that’s stored somewhere else (say, on an old Mac’s hard drive). Importing is a big help in making a smooth transition between your old email world and your new one.

Figure 19-3. If you go to File→Import Mailboxes, Mail offers to import your old email collection from just about any other Mac email program (top). You can even specify which email folders you want to import (bottom). When the importing process is finished—and it can take a very long time—you’ll find precisely the same folders set up in Mail.

To bring over your old mail and mailboxes, choose File→Import Mailboxes. Figure 19-3 has the details.

You get new mail and send mail you’ve already written using the Get Mail command. You can trigger it in any of several ways:

Click Get Mail on the toolbar.

Choose Mailbox→Get All New Mail (or press Shift-⌘-N).

Control-click (or right-click) Mail’s Dock icon, and choose Get New Mail from the shortcut menu. (You can use this method from within any program, as long as Mail is already open.)

Wait. Mail comes set to check your email automatically every few minutes. To adjust its timing or to turn this feature off, choose Mail→Preferences, click General, and then choose a time interval from the “Check for new messages” pop-up menu.

Now Mail contacts the mail servers listed in the Accounts pane of Mail’s preferences, retrieving new messages and downloading any files attached to those messages. It also sends any outgoing messages that couldn’t be sent when you wrote them.

Tip

The far-left column of the Mail window has a tiny Mail Activity monitor tucked away; click the second tiny button at the lower-left corner of the Mail window to reveal Mail Activity. If you don’t want to give up Mailboxes-list real estate, or if you prefer to monitor your mail in a separate window, you can do that, too. The Activity Viewer window gives you a Stop button, progress bars, and other useful information. Summon it by choosing Window→Activity, or by pressing ⌘-0.

Also, if you’re having trouble connecting to some (or all) of your email accounts, choose Window→Connection Doctor. There, you can see detailed information about which of your accounts aren’t responding. If your computer’s Internet connection is at fault, you can click Network Diagnostics to try to get back online.

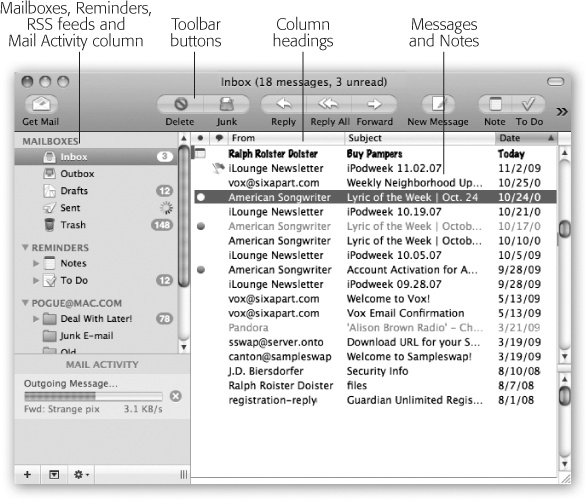

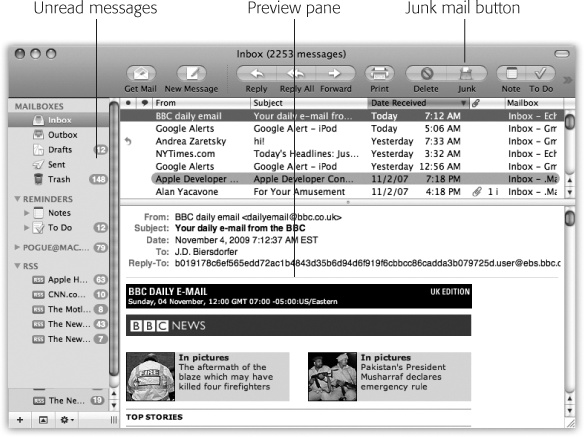

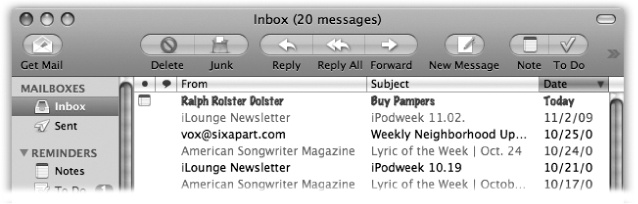

If you used early versions of Mail, the first thing you may notice is that the Mailbox panel isn’t just for mailboxes anymore. Categories like Reminders and RSS Feeds can appear there, too, as shown in Figure 19-4. But the top half of this gray-blue column on the left side lists all your email accounts’ folders (and subfolders, and sub-subfolders) for easy access. Mail looks quite a bit like iTunes (and iPhoto, and the Finder)—except here you have mailboxes where your iTunes Library and connected iPods would be.

In the Mailboxes panel, sometimes hidden by flippy triangles, you may find these folders:

Inbox holds mail you’ve received. If you have more than one email account, you can expand the triangles to see separate folders for your individual accounts. You’ll see this pattern repeated with the Sent, Junk, and other mailboxes, too—separate accounts have separate subheadings.

Tip

If Mail has something to tell you about your Inbox (like, for instance, that Mail can’t connect to it), a tiny warning triangle appears on the right side of the Mailboxes column. Click it to see what Mail is griping about.

If you see a lightning-bolt icon, that’s Mail’s way of announcing that you’re offline. Click the icon to try to connect to the Internet.

Figure 19-4. If you’ve ever used iTunes, you’ll notice a lot of similarities with the Mail window. All your information sources—mailboxes, notes, To Do items, and RSS Feeds—are grouped tidily in the far-left column, where you can always see them. Buttons along the top of the Mail window let you create new messages, notes, and tasks with a click. To see what’s in one of these folders, click it once. The list of its messages appears in the top half of the right side of the window (the Messages list).

Outbox holds mail you’ve written but haven’t yet sent (because you were on an airplane when you wrote it, for example). If you have no mail waiting to be sent, the Outbox itself disappears.

Drafts holds messages you’ve started but haven’t yet finished and don’t want to send just yet.

Sent, unsurprisingly, holds copies of messages you’ve sent.

Trash works a lot like the Trash on your desktop, in that messages you put there don’t actually disappear. They remain in the Trash folder until you permanently delete them or move them somewhere else—or until Mail’s automatic trash-cleaning service deletes them for you.

Junk appears automatically when you use Mail’s spam filter, as described later in this chapter.

Reminders. Any Notes you’ve jotted down while working in Mail are here. To Do items hang out here as well. (Both are described later in this chapter.)

RSS Feeds. Who needs to bop into a Web browser to keep up with the news? Mail brings it right to you while you’re corresponding, as described in a moment.

Mail Activity. You don’t need to summon a separate window to see how much more of that message with the giant attachment the program still has to send. To reveal the Mail activity panel, shown in Figure 19-4, click the second tiny icon in the bottom left side of the Mail window.

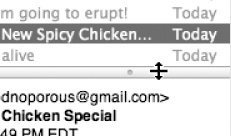

Preview pane. The difference between Figure 19-4 and 19-5 is the Preview pane—the bottom half of the main window, which shows the contents of whatever message you’ve selected in the list. If you’re not already seeing this pane, drag the bottom edge of the window, marked with a dot, upward (as shown in the box on the facing page); that’s the movable border between window halves.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: For the first time, you can now drag the mailboxes up and down in the list. Sweet.

Figure 19-5. The many panes of Mail. Click an icon in the Mailboxes column to see its contents in the Messages list. When you click the name of a message in the Messages list (or press the ↑ and ↓ keys to highlight successive messages in that list), you see the message itself, along with any attachments, in the Preview pane. Click one of the column headings (From, Subject, and so on) to sort your mail collection by that criterion.

To send an email, click New Message in the toolbar or press ⌘-N. The New Message form, shown in Figure 19-6, opens. Here’s how you go about writing a message:

In the “To:” field, type the recipient’s email address.

If somebody is in your Address Book, type the first couple of letters of the name or email address; Mail automatically completes the address. (If the first guess is wrong, type another letter or two until Mail revises its guess.)

Tip

If you find Mail constantly tries to autofill in the address of someone you don’t really communicate with, you can zap that address from its memory by choosing Window→Previous Recipients. Click the undesired address, and then click Remove From List.

As in most dialog boxes, you can jump from blank to blank (from “To:” to “Cc:,” for example) by pressing Tab. To send this message to more than one person, separate the addresses with commas: bob@earthlink.net, billg@microsoft.com, and so on.

Tip

If you send most of your email to addresses within the same organization (like reddelicious@apple.com, grannysmith@apple.com, and winesap@apple.com), Mail can automatically turn all other email addresses red. It’s a feature designed to avoid sending confidential messages to outside addresses.

To turn this feature on, choose Mail→Preferences, click Composing, turn on “Mark addresses not ending with,” and then type the “safe” domain (like apple.com) into the blank.

To send a copy to other recipients, enter their addresses in the “Cc:” field.

Cc stands for carbon copy. Getting an email message where your name is in the “Cc:” line implies: “I sent you a copy because I thought you’d want to know about this correspondence, but I’m not expecting you to reply.”

Tip

If Mail recognizes the address you type into the “To:” or “Cc:” box (because it’s someone in your Address Book, for instance), the name turns into a shaded, round-ended box button. Besides looking cool, these buttons have a small triangle on their right; when you click one, you get a list of useful commands (including Open in Address Book).

These buttons are also drag-and-droppable. For example, you can drag one from the “To:” box to the “Cc:” field, or from Address Book to Mail.

Figure 19-6. A message has two sections: the header, which holds information about the message; and the body, the big empty area that contains the message itself. In addition, the Mail window has a toolbar, which offers features for composing and sending messages. The Signature pop-up menu doesn’t exist until you create a signature; the Account pop-up menu lets you pick which email address you’d like to send the message from (if you have more than one email address).

Type the topic of the message in the Subject field.

It’s courteous to put some thought into the Subject line. (Use “Change in plans for next week,” for instance, instead of “Yo.”) And leaving it blank only annoys your recipient. On the other hand, don’t put the entire message into the Subject line, either.

Specify an email format.

There are two kinds of email: plain text and formatted (which Apple calls Rich Text). Plain text messages are faster to send and open, are universally compatible with the world’s email programs, and are greatly preferred by many veteran computer fans. And even though the message itself is plain, you can still attach pictures and other files. (If you want to get really graphic with your mail, you can also use the Stationery option, which gives you preformatted message templates to drop in pictures, graphics, and text. Flip to Stationery for more on using stationery.)

Resourceful geeks have even learned how to fake some formatting in plain messages: They use capitals or asterisks instead of bold formatting (*man* is he a GEEK!), “smileys” like this—:-)—instead of pictures, and pseudo-underlines for emphasis (I _love_ Swiss cheese!).

By contrast, formatted messages sometimes open slowly, and in some email programs the formatting doesn’t come through at all.

To control which kind of mail you send on a message-by-message basis, choose from the Format menu either Make Plain Text or Make Rich Text. To change the factory setting for new outgoing messages, choose Mail→Preferences; click the Composing icon; and choose from the Message Format pop-up menu.

Type your message in the message box.

You can use all standard editing techniques, including copy and paste, drag and drop, and so on. If you selected the Rich Text style of email, you can use word processor–like formatting (Figure 19-7).

As you type, Mail checks your spelling, using a dotted underline to mark questionable words (also shown in Figure 19-7). To check for alternative spellings for a suspect word, Control-click it. From the list of suggestions in the shortcut menu, click the word you really intended, or choose Learn Spelling to add the word to the Mac OS X dictionary. You can read much more about Mac OS X’s built-in spelling/grammar checker (and typing expander) in Chapter 6.

If you’re composing a long email message, or if it’s one you don’t want to send until later, click the Save as Draft button, press ⌘-S, or choose File→Save As Draft. You’ve just saved the message in your Drafts folder. It’ll still be there the next time you open Mail. To reopen a saved draft later, click the Drafts icon in the Mailboxes column and then double-click the message you want to work on.

Click Send (or press Shift-⌘-D).

Mail sends the message.

Tip

To resend a message you’ve already sent, Option-double-click the message in your Sent mailbox. Mail dutifully opens up a brand-new duplicate, ready for you to edit, readdress if you like, and then send again.

(The prescribed Apple route is to highlight the message and then choose Message→Send Again, but that’s not nearly as much fun.)

Figure 19-7. If you really want to use formatting, click the Fonts icon on the toolbar to open the Font panel, or the Colors icon to open the Color Picker dialog box. The Format menu (in the menu bar) contains even more controls: paragraph alignment (left, right, center, or justify), and even Copy and Paste Style commands that let you transfer formatting from one block of text to another.

If you’d rather have Mail place each message you write in the Outbox folder instead of connecting to the Net when you click Send, choose Mailbox→Take All Accounts Offline. While you’re offline, Mail refrains from trying to connect, which is a great feature when you’re working on a laptop at 39,000 feet. (Choose Mailbox→Take All Accounts Online to reverse the procedure.)

Sending little text messages is fine, but it’s not much help when you want to send somebody a photograph, a sound, or a Word document. To attach a file to a message you’ve written, use one of these methods:

Drag the icons you want to attach directly off the desktop (or out of a folder) into the New Message window. There your attachments appear with their own hyper-linked icons (shown in Figure 19-7), meaning that your recipient can simply click to open them.

Tip

Exposé was born for this moment. Hit ⌘-F3 to make all open windows flee to the edges of the screen, revealing the desktop. Root around until you find the file you want to send. Begin dragging it; without releasing the mouse, press ⌘-F3 again to bring your message window back into view. Complete your drag into the message window. (On old plastic keyboards, press F11 instead.)

Mail makes it look as though you can park the attached file’s icon (or the full image of a graphics file) inside the text of the message, mingled with your typing. Don’t be fooled, however; on the receiving end, all the attachments will be clumped together at the end of the message (unless your recipient also uses Mail or you’ve sent pictures with Stationery).

Drag the icons you want to attach from the desktop onto Mail’s Dock icon. Mail dutifully creates a new, outgoing message, with the files already attached.

Click the Attach icon on the New Message toolbar, choose File→Attach File, or press Shift-⌘-A. The standard Open File sheet now appears so you can navigate to and select the files you want to include. (You can choose multiple files simultaneously in this dialog box. Just ⌘-click or Shift-click the individual files you want as though you were selecting them in a Finder window.)

Once you’ve selected them, click Choose File (or press Return). You return to the New Message window, where the attachments’ icons appear, ready to ride along when you send the message.

To remove an attachment, drag across its icon to highlight it, and then press the Delete key. (You can also drag an attachment icon clear out of the window into your Dock’s Trash, or choose Message→Remove Attachments.)

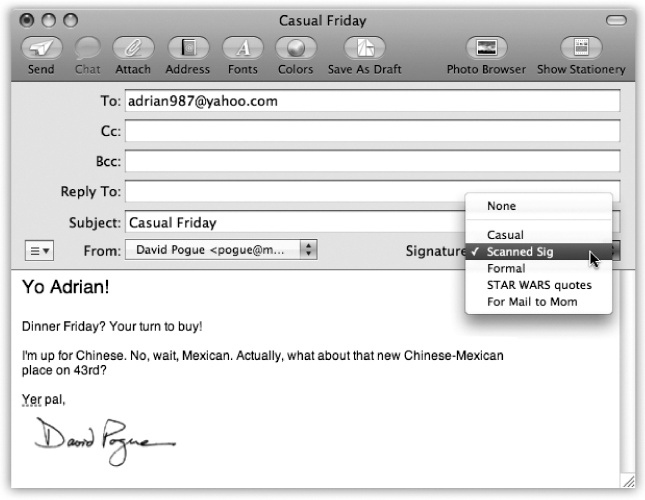

Signatures are bits of text that get stamped at the bottom of your outgoing email messages. A signature might contain a name, a postal address, a pithy quote, or even a scan of your real signature, as shown in Figure 19-6.

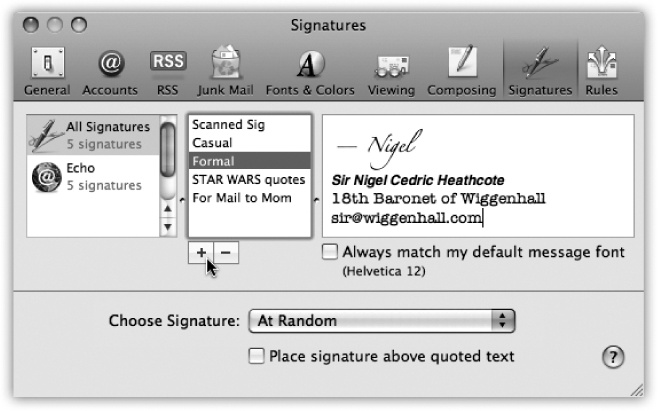

You can customize your signatures by choosing Mail→Preferences and then clicking the Signatures icon. Here’s what you should know:

To build up a library of signatures that you can use in any of your accounts: Select All Signatures in the leftmost pane, and then click the

button to add each new signature (Figure 19-8). Give each new signature a name in the middle pane, and then customize the signatures’ text in the rightmost pane.

button to add each new signature (Figure 19-8). Give each new signature a name in the middle pane, and then customize the signatures’ text in the rightmost pane.Tip

If you ever get tired of a signature, you can delete it forever by selecting All Signatures→[your signature’s name], clicking the

button, and then clicking OK.

button, and then clicking OK.Figure 19-8. After naming your signature in the middle pane and typing the text on the right, don’t miss the Format menu, which you can use to dress up your signature with colors and formatting. You can even paste a picture into the signature box. Click OK when you’re finished. (You can use formatted signatures only when sending Rich Text messages.)

To make a signature available in one of your email accounts: Drag the signature’s name from the middle pane onto the name of the account in the leftmost pane. In other words, you can make certain signatures available to only your work (or personal) account, so you never accidentally end up appending your secret FBI contact signature to the bottom of a birthday invitation you send out.

To assign a particular signature to one account: In the left pane, click an account; choose from the Choose Signature pop-up menu. Each time you compose a message from that account, Mail inserts the signature you selected.

Tip

To make things more interesting for your recipients, pick At Random; Mail selects a different signature each time you send a message. Or, if you’re not that much of a risk-taker, choose In Sequential Order; Mail picks the next signature in order for each new message you write.

Remember that you can always change your signature on a message-by-message basis, using the Signature pop-up menu in any new email message.

To use the signature feature as a prefix in replies: Turn on “Place signature above quoted text.” If you turn on this setting, your signature gets inserted above any text that you’re replying to, rather than below. You’d use this setting if your “signature” said something like, “Hi there! You wrote this to me!”

Rich text—and even plain text—messages are fine for your everyday personal and business correspondence. After all, you really won’t help messages like, “Let’s have a meeting on those third-quarter earnings results” much by adding visual bells and whistles.

But suppose you have an occasion where you want to jazz up your mail, like an electronic invitation to a bridal shower or a mass-mail update as you get your kicks down Route 66.

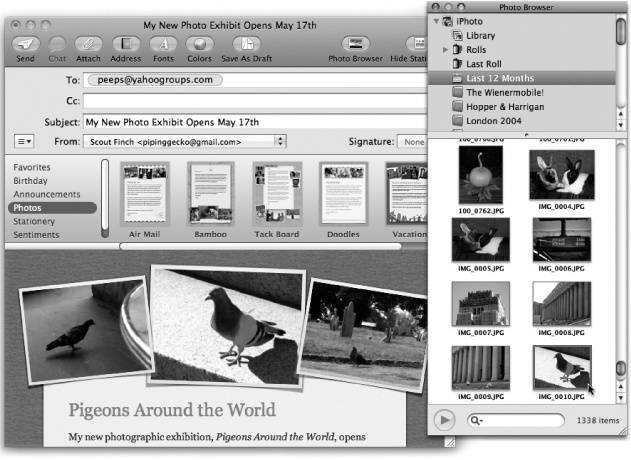

These messages just cry out for Mail’s Stationery feature. Stationery means colorful, predesigned mail templates that you make your own by dragging in photos from your own collection. Those fancy fonts and graphics will certainly get people’s attention when they open the message.

Note

They will, that is, if their email programs understand HTML formatting. That’s the formatting Mail uses for its stationery. (If HTML rings a bell, it’s because this HyperText Markup Language is the same used to make Web pages so lively and colorful.)

It might be a good idea to make sure everyone on your recipient list has a mail program that can handle HTML; otherwise, your message may look like a jumble of code and letters in the middle of the screen.

To make a stylized message with Mail Stationery:

Create a new message.

Click File→New Message, press ⌘-N, or click the New Message button on the Mail window toolbar. The choice is up to you.

On the right side of the toolbar on the New Message window, click Show Stationery.

A panel opens up, showing you all the available templates, in categories like “Birthday” and “Announcements.”

Click a category, and then click a stationery thumbnail image to apply it to your message.

The body of your message changes to take on the look of the template.

If you like what you see, click the Hide Stationery button on the toolbar to fold up the stationery-picker panel.

Tip

If you don’t like the background color, try clicking the thumbnail; some templates offer a few different color choices.

Now, without question, Apple’s canned stationery looks fantastic. The only problem is, the photos that adorn most of the templates are pictures of somebody else’s family and friends. Unless you work for Apple’s modeling agency, you probably have no clue who they are.

Fortunately, it’s easy enough to replace those placeholder photos with your own snaps.

Add and adjust pictures.

Click the Photo Browser icon on the message toolbar to open up a palette that lists all the photos you’ve stored in iPhoto, Aperture, and Photo Booth (Figure 19-9).

Tip

If you don’t keep your pictures in any of those programs, you can drag any folder of pictures onto the Photo Browser window to add them.

Figure 19-9. To use Stationery, start by clicking a template, then add your own text in place of the generic copy that comes with the template. Click the Photo Browser button at the top of the message window to open your Mac’s photo collections (shown at right), and then drag the images you want into the picture boxes on the stationery template. You don’t have to know a lick of HTML to use the templates—it’s all drag, drop, and type, baby.

Now you can drag your own pictures directly onto Apple’s dummy photos on the stationery template. They replace the sunny models.

To resize a photo in the template, double-click it. A slider appears that lets you adjust the photo’s size within the message. Drag the mouse around the photo window to reposition the picture relative to its frame.

Select the fake text and type in what you really want to say.

Unless you’re writing to your Latin students, of course, in which case “Duis nonsequ ismodol oreetuer iril dolore facidunt” might be perfectly appropriate.

In any case, as you type over the dummy text, your words are autoformatted to match the template design.

Once you’ve got that message looking the way you want it, address it just as you would any other piece of mail, and then click the Send button to get it on its way.

Tip

You’re not stuck with Apple’s designs for your Stationery templates; you can make your own. Just make a new message, style the fonts and photos the way you want them, and then choose File→Save as Stationery. You can now select your masterwork in the Custom category, which appears down at the end of the list in the stationery-picker panel.

If you decide that the message would be better off as plain old text, click Show Stationery on the message window. In the list of template categories, click Stationery and then Original to strip the color and formats out of the message.

Tip

If you find you’re using one or two templates a lot (if, for example, all your friends are having babies these days), drag your frequently used templates into the Favorites category so you don’t have to go wading around for them.

To remove one from Favorites, click it, and then click the  in the top-left corner of the thumbnail.

in the top-left corner of the thumbnail.

Mail puts all incoming email into your Inbox; the statistic after the word Inbox lets you know how many messages you haven’t yet read. New messages are also marked with light-blue dots in the main list.

Tip

The Mail icon in the Dock also shows you how many new messages you have waiting; it’s the number in the red circle.

Click the Inbox folder to see a list of received messages. If it’s a long list, press Control-Page Up and Control-Page Down to scroll. (Page Up and Page Down without the Control key scrolls the Preview pane instead.)

Click the name of a message once to read it in the Preview pane, or double-click a message to open it into a separate window. (If a message is already selected, pressing Return or Enter also opens its separate window.)

Tip

Instead of reading your mail, you might prefer to have Mac OS X read it to you, as you sit back in your chair and sip a strawberry daiquiri. Highlight the text you want to hear (or choose Edit→Select All), and then choose Edit→Speech→Start Speaking. You’ll hear the message read aloud, in the voice you’ve selected on the Speech pane of System Preferences (Chapter 9).

To stop the insanity, choose Edit→Speech→Stop Speaking.

Once you’ve viewed a message, you can respond to it, delete it, print it, file it, and so on. The following pages should get you started.

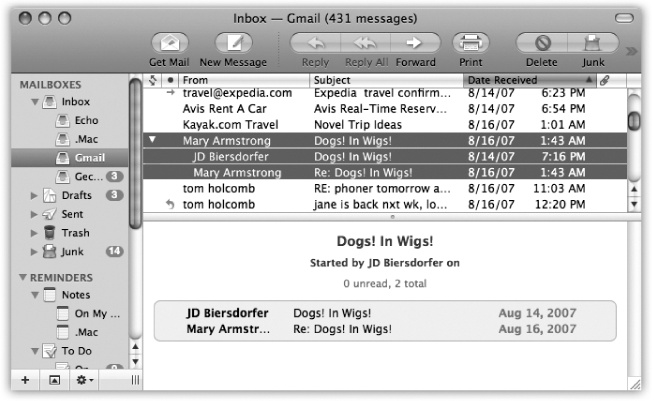

Threading is one of the most useful mail-sorting methods to come along in a long time. When threading is turned on, Mail groups emails with the same subject (like “Raccoons” and “Re: Raccoons”) as a single item in the main mail list.

To turn on threading, choose View→Organize by Thread. If several messages have the same subject, they all turn light blue to indicate their membership in a thread (Figure 19-10).

Figure 19-10. Threads have two parts: a heading (the subject of the thread, listed in dark blue when it’s not selected) and members (the individual messages in the thread, listed in light blue and indented). Often, the main list shows only a thread’s heading; click the flippy triangle to reveal its members.

Here are some powerful ways to use threading:

View a list of all the messages in a thread by clicking its heading. In the Preview pane, you see a comprehensive inventory of the thread (Figure 19-10). You can click a message’s name in this list to jump right to it.

Move all the members of a thread to a new mailbox simply by moving its heading. You might find this useful, for example, when you’ve just finished a project and want to file away all the email related to it quickly. (As a bonus, a circled number tells you how many messages you’re moving as you drag the heading.) You can even delete all the messages in a thread at once by deleting its heading.

Examine thread members from multiple mailboxes. Normally, threads display only messages held in the same mailbox, but that’s not especially convenient when you want to see both messages (from your Inbox) and your replies (in your Sent box). To work around that problem, click Inbox, and then ⌘-click the Sent mailbox (or any other mailboxes you want to include). Your threads seamlessly combine related messages from all the selected mailboxes.

Quickly collapse all threads by choosing View→Collapse All Threads. If your main list gets cluttered with too many expanded threads, this is a quick way to force it into order. (If, on the other hand, your main list isn’t cluttered enough, choose View→Expand All Threads.)

Send someone all the messages in a thread by selecting the thread’s heading and clicking Forward. Mail automatically copies all the messages of the thread into a new message, putting the oldest at the top. You might find this useful, for instance, when you want to send your boss all the correspondence you’ve had with someone about a certain project.

When you choose the Message→Add Sender to Address Book command, Mail memorizes the email address of the person whose message is on the screen. In fact, you can highlight a huge number of messages and add all the senders simultaneously using this technique.

Thereafter, you’ll be able to write new messages to somebody just by typing the first few letters of her name or email address.

Data detectors are described on Keyboard Viewer: The Return of Key Caps. They’re what you see when Mac OS X recognizes commonly used bits of written information: a physical address, a phone number, a date and time, a flight number, and so on. With one quick click, you can send that information into the appropriate Mac OS X program, like iCal, Address Book, the Flights widget in Dashboard, or your Web browser (for looking an address up on a map).

This is just a public-service reminder that data detctors are especially useful—primarily useful, in fact—in Mail. Watch for the dotted rectangle that appears when you point to a name, address, date, time, or flight number.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: When someone sends you what looks like a date and time—“Hey, we’re getting together for a luau at my apartment on 6/12/2010 at 8:30 pm! Hope you can come!”—the data detector goes one better. Now the pop-up menu that opens when you click the  button actually proposes, “Create New iCal Event.” (It even works for less specific wording, like, “Can you come over Thursday afternoon at 3:30?”)

button actually proposes, “Create New iCal Event.” (It even works for less specific wording, like, “Can you come over Thursday afternoon at 3:30?”)

You look over the proposed appointment (you’ll probably want to edit the title), and that’s it—Mail actually creates an appointment on your iCal automatically!

Just as you can attach files to a message, so people often send files to you. Sometimes they don’t even bother to type a message; you wind up receiving an empty email message with a file or two attached. Only the presence of the file’s icon in the message body tells you there’s something attached.

Tip

Mail doesn’t ordinarily indicate the presence of attachments in the Messages list. It can do so, however. Just choose View→Columns→Attachments. A new column appears in the email list—at the far right—where you see a paper-clip icon and the number of file attachments listed for each message.

Mail doesn’t store downloaded files as normal file icons on your hard drive. They’re actually encoded right into the .mbox mailbox databases described on Archiving Mailboxes. To extract an attached file from this mass of software, you must proceed in one of these ways:

Click the Quick Look button in the message header. Instantly, you’re treated to a nearly full-size preview of the file’s contents. Yes, Quick Look has come to email. Its strengths and weaknesses here are exactly as described in Chapter 1.

Click the Save button in the message header to save it to the Mac’s Downloads folder, nestled within easy reach in the Dock.

Control-click (or right-click) the attachment’s icon, and choose Save Attachment from the shortcut menu. You’ll be asked to specify where you want to put it. Or save time by choosing Save to Downloads Folder, meaning the Downloads folder in the Dock.

Drag the attachment icon out of the message window and onto any visible portion of your desktop (or any visible folder).

Click the Save button at the top of the email, or choose File→Save Attachments. (If the message has more than one attachment, this maneuver saves all of them.)

Double-click the attachment’s icon, or single-click the blue link underneath the icon. If you were sent a document (a photo, Word file, or Excel file, for example), it now opens in the corresponding program.

Control-click the attachment’s icon. From the shortcut menu, you can specify which program you want to use for opening it, using the Open With submenu.

To answer a message, click the Reply button on the message toolbar (or choose Message→Reply, or press ⌘-R). If the message was originally addressed to multiple recipients, you can send your reply to everyone simultaneously by clicking Reply All instead.

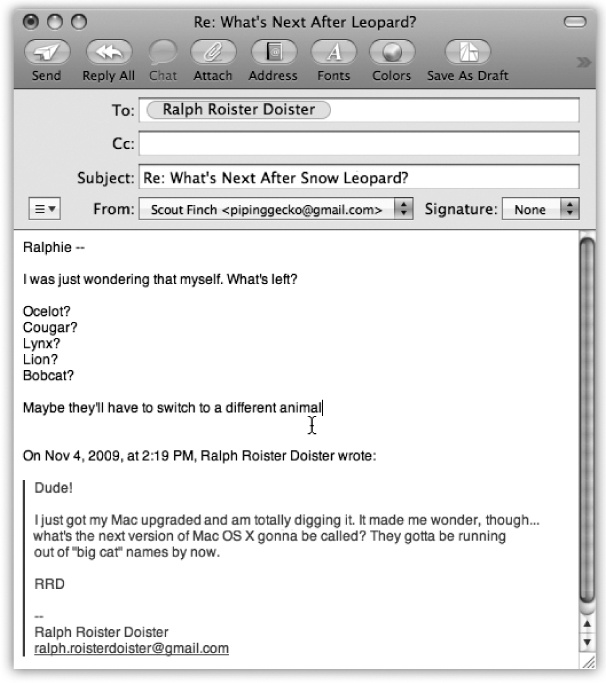

A new message window opens, already addressed. As a courtesy to your correspondent, Mail places the original message at the bottom of the window, set off by a vertical bar, as shown in Figure 19-11.

Tip

If you highlight some text before clicking Reply, Mail pastes only that portion of the original message into your reply. That’s a great convenience to your correspondent, who now knows exactly which part of the message you’re responding to.

At this point, you can add or delete recipients, edit the Subject line or the original message, attach a file, and so on.

Tip

Use the Return key to create blank lines in the original message. Using this method, you can splice your own comments into the paragraphs of the original message, replying point by point. The brackets preceding each line of the original message help your correspondent keep straight what’s yours and what’s hers.

Figure 19-11. In Mail messages formatted with Rich Text (not to be confused with Rich Text Format word processing format, which is very different), a reply includes the original message, marked in a special color (which you can change in Mail→Preferences) and with a vertical bar to differentiate it from the text of your reply. (In plain-text messages, each line of the reply is >denoted >with >brackets, although only your recipient will see them.) The original sender’s name is automatically placed in the “To:” field. The subject is the same as the original subject with the addition of Re: (shorthand for Regarding). You’re now ready to type your response.

When you’re finished, click Send. (If you click Reply All in the message window now, your message goes to everyone who received the original note, even if you began the reply process by clicking Reply. Mac OS X, in other words, gives you a second chance to address your reply to everyone.)

Instead of replying to the person who sent you a message, you may sometimes want to pass the note on to a third person.

To do so, click the Forward toolbar button (or choose Message→Forward, or press Shift-⌘-F). A new message opens, looking a lot like the one that appears when you reply. You may wish to precede the original message with a comment of your own, along the lines of: “Frank: I thought you’d be interested in this joke about your mom.”

Finally, address it as you would any outgoing piece of mail.

A redirected message is similar to a forwarded message, with one useful difference: When you forward a message, your recipient sees that it came from you. When you redirect it, your recipient sees the original writer’s name as the sender. In other words, a redirected message uses you as a low-profile relay station between two other people.

Treasure this feature. Plenty of email programs, including Outlook and Outlook Express for Windows, don’t offer a Redirect command at all. You can use it to transfer messages from one of your own accounts to another, or to pass along a message that came to you by mistake.

To redirect a message, choose Message→Redirect, or press Shift-⌘-E. You get an outgoing copy of the message—this time without any quoting marks. (You can edit redirected messages before you send them, too, which is perfect for April Fools’ Day pranks.)

Sometimes there’s no substitute for a printout. Choose File→Print, or press ⌘-P to summon the Print dialog box.

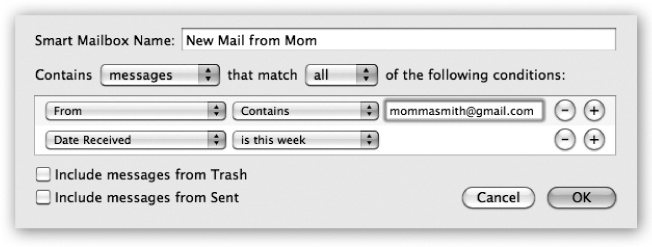

Mail lets you create new mailboxes in the Mailboxes pane. You might create one for important messages, another for order confirmations from Web shopping, still another for friends and family, and so on. You can even create mailboxes inside these mailboxes, a feature beloved by the hopelessly organized.

Mail even offers smart mailboxes—self-updating folders that show you all your mail from your boss, for example, or every message with “mortgage” in its subject. It’s the same idea as smart folders in the Finder or smart playlists in iTunes: folders whose contents are based around criteria you specify (Figure 19-12).

Figure 19-12. Mail lets you create self-populating folders. In this example, the “New Mail from Mom” smart mailbox will automatically display all messages from her that you’ve received in the past week.

The commands you need are all in the Mailbox menu. For example, to create a new mailbox folder, choose Mailbox→New Mailbox, or click the  button at the bottom of the Mailboxes column. To create a smart mailbox, choose Mailbox→New Smart Mailbox.

button at the bottom of the Mailboxes column. To create a smart mailbox, choose Mailbox→New Smart Mailbox.

Mail asks you to name the new mailbox. If you have more than one email account, you can specify which one will contain the new folder. (Smart mailboxes, however, always sit outside your other mailboxes.)

Tip

If you want to create a folder-inside-a-folder, use slashes in the name of your new mailbox. (If you use the name Cephalopods/Squid, for example, then Mail creates a folder called Cephalopods, with a subfolder called Squid.) You can also drag the mailbox icons up and down in the drawer to place one inside another.

None of those tricks work for smart mailboxes, however. The only way to organize smart mailboxes is to put them inside a smart mailbox folder, which you create using Mailbox→New Smart Mailbox. You might do that if you have several smart mailboxes for mail from your coworkers (“From Jim,” “From Anne,” and so on) and want to put them together in one collapsible group to save screen space.

When you click OK, a new icon appears in the mailbox column, ready for use.

You can move a message (or group of messages) into a mailbox folder in any of three ways:

Drag it out of the main list onto a mailbox icon.

In the list pane, highlight one or more messages, and then choose from the Message→Move To submenu, which lists all your mailboxes.

Control-click (or right-click) a message, or one of several that you’ve highlighted. From the resulting shortcut menu, choose Move To, and then, from the submenu, choose the mailbox you want.

Of course, the only way to change the contents of a smart mailbox is to change the criteria it uses to populate itself. To do so, double-click the smart mailbox icon and use the dialog box that appears.

Sometimes you’ll receive email that prompts you to some sort of action, but you may not have the time (or the fortitude) to face the task at the moment. (“Hi there… it’s me, your accountant. Would you mind rounding up your expenses for 1999 through 2009 and sending me a list by email?”)

That’s why Mail lets you flag a message, summoning a little flag icon in a new column next to a message’s name. These indicators can mean anything you like—they simply call attention to certain messages. You can sort your mail list so that all your flagged messages are listed first; click the flag at the top of the column heading.

To flag a message in this way, select the message (or several messages) and then choose Message→Mark→As Flagged, or press Option-⌘-L, or Control-click (right-click) the message’s name in the list and, from the shortcut menu, choose Mark→As Flagged. (To clear the flags, repeat the procedure, but use the Mark→As Unflagged command instead.)

Tip

This whole flagging business has another useful side effect. When Mail finds messages it thinks are spam, it marks them with little trash-bag icons in the flag column. If you sort your mail by flag, then all your spam gets grouped together—which is great if you want to do one big spam-cleaning by dragging it all to the Trash.

When you deal with masses of email, you may come to rely on Mail’s dedicated searching tools. They’re fast and convenient, and when you’re done with them, you can go right back to browsing your Message list as it was.

The box in the upper-right corner of the main mail window is Mail’s own private Spotlight. You can use it to hide all but certain messages, as shown in Figure 19-13.

Tip

You can also set up Mail to show you only certain messages that you’ve manually selected, hiding all others in the list. To do so, highlight the messages you want, using the usual selection techniques (Selecting by Clicking). Then choose View→Display Selected Messages Only. (To see all of them again, choose View→Display All Messages.)

Figure 19-13. You can jump to the search box by clicking or by pressing Option-⌘-F. As you type, Mail shrinks the list of messages. You can fine-tune your results using the buttons just above the list. To return to the full message list, click the tiny  at the right side of the search box.

at the right side of the search box.

In Snow Leopard, this search box is powerful indeed. For example:

You have the power of Spotlight charging up your search rankings; the most relevant messages for your search appear high on the list. And Notes and To Do items show up in the search results now, too.

When you’re searching, a thin row of buttons appears underneath the toolbar. You can use these buttons to narrow your results to only messages with your search term in their subject, for example, or to only those messages in the currently selected mailbox.

When you select a message in the search view, the Preview pane pops up from the bottom of the window. If you click Show in Mailbox, on the other hand, you exit the search view and jump straight to the message in whatever mailbox it came from. That’s perfect if the message is part of a thread, since jumping to the message also displays all the other messages from its thread.

If you think you’ll want to perform the current search again sometime, click Save in the upper-right corner of the window. Mail displays a dialog box with your search term and criteria filled in; all you have to do is give it a name and click OK to transform your search into a smart mailbox that you can open anytime.

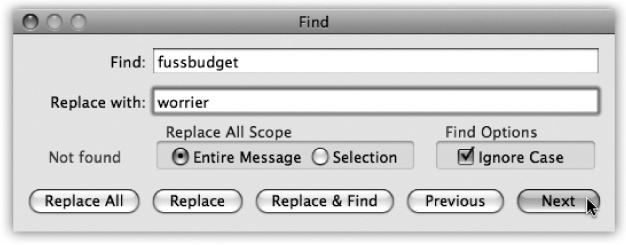

You can also search for certain text within an open message. Choose Edit→Find→Find (or press ⌘-F) to bring up the Find dialog box (Figure 19-14).

Sometimes it’s junk mail. Sometimes you’re just done with it. Either way, it’s a snap to delete a selected message, several selected messages, or a message that’s currently before you on the screen. You can press the Delete key, click the Delete button on the toolbar, choose Edit→Delete, or drag messages out of the list window and into your Trash mailbox—or even onto the Dock’s Trash icon.

All these commands move the messages to the Trash folder. If you like, you can then click its icon to view a list of the messages you’ve deleted. You can even rescue messages by dragging them back into another mailbox (back to the Inbox, for example).

Mail doesn’t vaporize messages in the Trash folder until you “empty the trash,” just like in the Finder. You can empty the Trash folder in any of several ways:

Click a message (or several) within the Trash folder list, and then click the Delete icon on the toolbar (or press the Delete key). Now those messages are really gone.

Choose Mailbox→Erase Deleted Messages (⌘-K). (If you have multiple accounts, choose Erase Deleted Messages→In All Accounts.)

Control-click (or right-click) the Trash mailbox icon, and then choose Erase Deleted Messages from the shortcut menu. Or choose the same command from the

pop-up menu at the bottom of the window.

pop-up menu at the bottom of the window.Wait. Mail will permanently delete these messages automatically after a week.

If a week is too long (or not long enough), you can change this interval. Choose Mail→Preferences, click Accounts, and select the account name from the list at left. Then click Mailbox Behaviors, and change the “Erase deleted messages when” pop-up menu. If you choose Quitting Mail from the pop-up menu, Mail will take out the trash every time you quit the program.

Mail offers a second—and very unusual—method of deleting messages that doesn’t involve the Trash folder at all. Using this method, pressing the Delete key (or clicking the Delete toolbar button) simply hides the selected message in the list. Hidden messages remain hidden, but don’t go away for good until you use the Rebuild Mailbox command described in the box on Rebuilding Your Mail Databases.

If this arrangement sounds useful, choose Mail→Preferences; click Accounts and select the account from the list on the left; click Mailbox Behaviors; and then turn off the checkbox called “Move deleted messages to a separate folder” or “Move deleted messages to the Trash mailbox.” (The checkbox’s wording depends on what kind of account you have.) From now on, messages you delete vanish from the list.

They’re not really gone, however. You can bring them back, at least in ghostly form, by choosing View→Show Deleted Messages (or pressing ⌘-L). Figure 19-15 shows the idea.

Using this system, in other words, you never truly delete messages; you just hide them.

Figure 19-15. To resurrect a deleted message (indicated in light gray type), Control-click it and choose Undelete from the shortcut menu.

At first, you might be concerned about the disk space and database size involved in keeping your old messages around forever like this. Truth is that Mac OS X is perfectly capable of maintaining many thousands of messages in its mailbox databases—and with the sizes of hard drives nowadays, a few thousand messages aren’t likely to make much of a dent.

Meanwhile, there’s a huge benefit to this arrangement. At some point, almost everyone wishes they could resurrect a deleted message—maybe months later, maybe years later. Using the hidden-deleted-message system, your old messages are always around for reference. (The downside to this system, of course, is that SEC investigators can use it to find incriminating mail that you thought you’d deleted.)

When you do want to purge these messages for good, you can always return to the Special Mailboxes dialog box and turn the “Move deleted mail to a separate folder” checkbox back on.

Time Machine (Chapter 6) keeps a watchful eye on your Mac and backs up its data regularly—including your email. If you ever delete a message by accident or otherwise make a mess of your email stash, you can duck into Time Machine right from within Mail.

But not everybody wants to use Time Machine, for personal reasons—lack of a second hard drive, aversion to software named after H. G. Wells novels, whatever.

Yet having a backup of your email is critically important. Think of all the precious mail you’d hate to lose: business correspondence, electronic receipts, baby’s first message. Fortunately, there’s a second good way to back up your email—archive it, like this:

In the Mailboxes column, choose which mailbox or mailboxes you want to archive.

If you have multiple mailboxes in mind, Control-click (or right-click) each one until you’ve selected all the ones you want.

At the bottom of the Mail window, open the

pop-up menu and choose Archive Mailbox(es).

pop-up menu and choose Archive Mailbox(es).You can also get to this command by choosing Mailbox→Archive.

In the box that appears, navigate to the place you want to stash this archive of valuable mail, like a server, flash drive, or folder. Click Choose.

Your archived mailboxes are saved to the location you’ve chosen. You can now go back to work writing new messages.

Later, if you need to pull one of those archives back into duty, choose File→Import Mailboxes. Choose the “Mail for Mac OS X” option and navigate back to the place you stored your archived mailboxes.

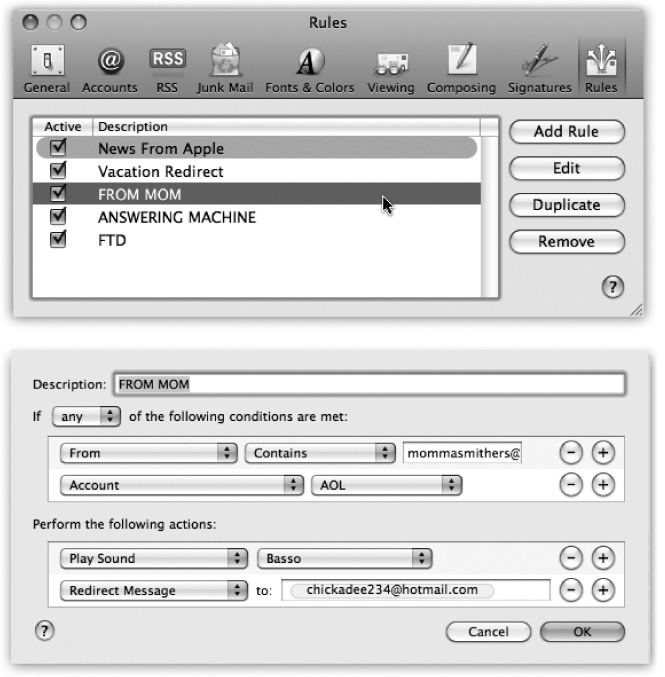

Once you know how to create folders, the next step in managing your email is to set up a series of message rules (filters) that file, answer, or delete incoming messages automatically based on their contents (such as their subject, address, and/or size). Message rules require you to think like the distant relative of a programmer, but the mental effort can reward you many times over. Message rules turn Mail into a surprisingly smart and efficient secretary.

Here’s how to set up a message rule:

Choose Mail→Preferences. Click the Rules icon.

The Rules pane appears, as shown at top in Figure 19-16.

Click Add Rule.

Now the dialog box shown at bottom in Figure 19-16 appears.

Use the criteria options (at the top) to specify how Mail should select messages to process.

For example, if you’d like the program to watch out for messages from a particular person, you would set up the first two pop-up menus to say “From” and “Contains,” respectively.

To flag messages containing loan, $$$$, XXXX, !!!!, and so on, set the pop-up menus to say “Subject” and “Contains.”

You can set up multiple criteria here to flag messages whose subjects contain any one of those common spam triggers. (If you change the “any” pop-up menu to say “all,” then all the criteria must be true for the rule to kick in.)

Figure 19-16. Top: Mail rules can screen out junk mail, serve as an email answering machine, or call important messages to your attention. All mail message rules you’ve created appear in this list. (The color shading for each rule is a reflection of the colorizing options you’ve set up, if any.) Bottom: Double-click a rule to open the Edit Rule dialog box, where you can specify what should set off the rule and what it should do in response.

Specify which words or people you want the message rule to watch for.

In the text box to the right of the two pop-up menus, type the word, address, name, or phrase you want Mail to watch for—a person’s name, or $$$$, in the previous examples.

In the lower half of the box, specify what you want to happen to messages that match the criteria.

If, in steps 1 and 2, you’ve told your rule to watch for junk mail containing $$$$ in the Subject line, here’s where you can tell Mail to delete it or move it into, say, a Junk folder.

With a little imagination, you’ll see how the options in this pop-up menu can do absolutely amazing things with your incoming email. Mail can colorize, delete, move, redirect, or forward messages—or even play a sound when you get a certain message.

By setting up the controls as shown in Figure 19-16, for example, you’ll have specified that whenever your mother (mom@mcmail.com) sends something to your Gmail account, you’ll hear a specific alert noise as the email is redirected to a different email account, chickadee745@hotmail.com.

In the very top box, name your mail rule. Click OK.

Now you’re back to the Rules pane (Figure 19-16, top). Here you can choose a sequence for the rules you’ve created by dragging them up and down. Here, too, you can turn off the ones you won’t be needing at the moment, but may use again one day.

Tip

Mail applies rules as they appear, from top to bottom, in the list. If a rule doesn’t seem to be working properly, it may be that an earlier rule is intercepting and processing some messages before the “broken” rule even sees them. To fix this, try dragging the rule (or the interfering rule) up or down in the list.

Spam, the junk that now makes up more than 80 percent of email, is a problem that’s only getting worse. Luckily, you, along with Mail’s advanced spam filters, can make it better—at least for your email accounts.

You’ll see the effects of Mail’s spam filter the first time you check your mail: A certain swath of message titles appears in color. These are the messages that Mail considers junk.

Note

Out of the box, Mail doesn’t apply its spam-targeting features to people whose addresses are in your Address Book, to people you’ve emailed recently, or to messages sent to you by name rather than just by email address. You can adjust these settings in Mail→Preferences→Junk Mail tab.

During your first couple of weeks with Mail, your job is to supervise Mail’s work. That is, if you get spam that Mail misses, click the message, and then click the Junk button at the top of its window, or the Junk icon on the toolbar. On the other hand, if Mail flags legitimate mail as spam, slap it gently on the wrist by clicking the Not Junk button. Over time, Mail gets better and better at filtering your mail; it even does surprisingly well against the new breed of image-only spam.

The trouble with this so-called Training mode is that you’re still left with the task of trashing the spam yourself, saving you no time whatsoever.

Once Mail has perfected its filtering skills to your satisfaction, though, open Mail’s preferences, click Junk Mail, and click “Move it to the Junk mailbox.” From now on, Mail automatically files what it deems junk into a Junk mailbox, where it’s much easier to scan and delete the messages en masse.

The Junk filter goes a long way toward cleaning out the spam from your mail collection—but it doesn’t catch everything. If you’re overrun by spam, here are some other steps you can take:

Don’t let the spammers know you’re there. Choose Mail→Preferences, click Viewing, and turn off “Display remote images in HTML messages.” This option thwarts a common spammer tactic by blocking graphics that appear to be embedded into a message but are actually retrieved from a Web site somewhere. Spammers use that embedded-graphics trick to know that their message has fallen on fertile ground—a live sucker who actually looks at these messages—but with that single preference switch, you can fake them out.

Rules. Set up some message rules, as described on the preceding pages, that autoflag messages as spam that have subject lines containing trigger words like “Viagra,” “Herbal,” “Mortgage,” “Refinance,” “Enlarge,” “Your”—you get the idea.

Create a private account. Above all, if you’re overrun by spam, consider sacrificing your address to the public areas of the Internet, like chat rooms, online shopping, Web site and software registration, and newsgroup posting. Spammers use automated software robots that scour every public Internet message and Web page, recording email addresses they find. (In fact, that’s probably how they got your address in the first place.)

Using this technique, at least you’re now restricting the junk mail to a secondary mail account. Reserve a separate email account for person-to-person email.

Here are some suggestions for avoiding spammers’ lists in the first place:

Don’t ask for it. When filling out forms online, turn off the checkboxes that say, “Yes, send me exciting offers and news from our partners.”

Fake out the robots. When posting messages in a newsgroup or message board, insert the letters NOSPAM somewhere into your email address. Anyone replying to you via email must delete the NOSPAM from your email address, which is a slight hassle. Meanwhile, though, the spammers’ software robots will lift a bogus email address from your online postings.

Never reply to spam. Doing so identifies your email address as an active one and can lead to even more unwanted mail. Along the same lines, never click the “Please remove me from your list” link at the bottom of an email unless you know who sent the message.

And for goodness’ sake, don’t order anything sold by the spammers. If only one person in 500,000 does so, the spammer makes money.

Mail gets more than mail. It also helps you keep yourself up to date with the world outside—and within your own little corner of it.

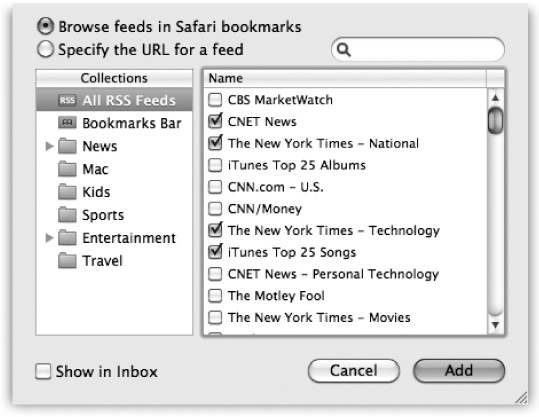

For example, the ability to subscribe to those constantly updating news summaries known as RSS feeds has saved a lot of people a lot of time over the years. After all, why waste precious minutes looking for the news when you can make the news find you?

With Mail, you don’t even have to waste the seconds switching from your Inbox to your browser or dedicated RSS program to get a fresh dose of headlines. They can appear right in the main Mail window. You don’t even have to switch programs to find out which political candidate shot his foot off while it was still in his mouth.

In fact, if you find it too exhausting to click the RSS icon in the Mailboxes list, you can choose instead to have all your RSS updates land right in your Inbox along with all your other messages.

With just a few clicks, you can bring the news of the world right in with the rest of your mail. Choose File→Add RSS Feeds, and then proceed as shown in Figure 19-17.

If you want the RSS headlines to appear in your Inbox like regular email messages, turn on “Show in Inbox.” Finally, once you’ve chosen the feeds you want to see, click Add. Your feeds now appear wherever you told them to go: either the Inbox or the Mailboxes column.

Now, in the RSS category of your Mailboxes list, the names of your RSS feeds show up; the number in the small gray circle tells you how many unread headlines are in the list. If a feed headline intrigues you enough to want more information, click “Read More…” to do just that. Safari pops up and whisks you away to the Web site that sent out the feed in the first place.

Tip

Click the up arrow button next to a feed’s name to move all its updates into your Inbox; there, they appear with the same blue RSS label, but they behave as though they’re an Inbox category to spare you having to flip back and forth between two distant areas of the Mailboxes list.

If you accidentally click that arrow, and you don’t really want 57 headlines from RollingStone.com peppering your daily dose of mail, click the feed’s name and then click the down-pointing arrow next to it; it returns to the RSS section of the list. Alternatively, you can Control-click (or right-click) the feed name under Mailboxes and turn off “Show in Inbox” from the shortcut menu.

Figure 19-17. In the Add RSS Feeds box, you can click to add sites you’ve already subscribed to in Safari. If you don’t already have the feed bookmarked in Safari, click “Specify a custom feed URL” and paste the feed’s address into the resulting box. If you’ve got a ton of feeds and don’t want to wade through them all, use the search box to seek out the specific feed you need.

Now that you’ve got your feeds in Mail, you may want to fiddle around with them.

Updating. You can change the frequency of your news updates by choosing Mail→Preferences→RSS→Check for Updates. You can automatically update them every half hour, every hour, or every day. You can also command Mail to update a certain feed right now; Control-click the feed’s name in the Mailboxes list and, from the shortcut menu, choose “Update BBC News” (or whatever its name is).

Archiving. You can save and store a whole batch of feeds in an archive file, just as you can do with regular mailboxes; choose Mailbox→Archive Feed. A dialog box walks you through saving a copy of all the messages to a backup drive or other location for safekeeping.

Sharing. If you want to share the news with a friend, Control-click a headline; from the shortcut menu, choose Forward (or Forward as Attachment) to pop the info into a new Mail message that you can send off to your pal.

Renaming. You don’t have to use the site’s full name in your Mail window—after all, “WaPo” fits much better in the Mailboxes column than “Washington Post.” To rename a feed, select it and then choose Mailbox→Rename Feed. Type in the new name and press Return. (You can also Control-click or right-click the name to bring up the Rename Feed option.)

Deleting. After you’ve read a news item and are done with it, click the Delete button at the top of the window. You can tell Mail to dump all the old articles after a certain amount of time (a day, a week, a month) in Mail→Preferences→RSS→Remove Articles.

Or, to get rid of an RSS feed altogether, select it and then choose Maibox→Delete Feed. (Control- or right-clicking the name gives you the same option.)

Let’s face it: No operating system is complete without Notes. You have to have a place for little reminders, phone numbers, phone messages, Web addresses, brainstorms, shopping-list hints—anything that’s worth writing down, but too tiny to justify heaving a whole word processor onto its feet.

The silly thing is how many people create reminders for themselves by sending themselves an email message.

That system works, but it’s a bit inelegant. Fortunately, Mac OS X has a dedicated Notes feature. As a bonus, it syncs automatically to the Notes folder of your iPhone’s mail program, or to other computers, as long as you have an IMAP-style email account (see the box on POP, IMAP, Exchange, and Web-based Mail).

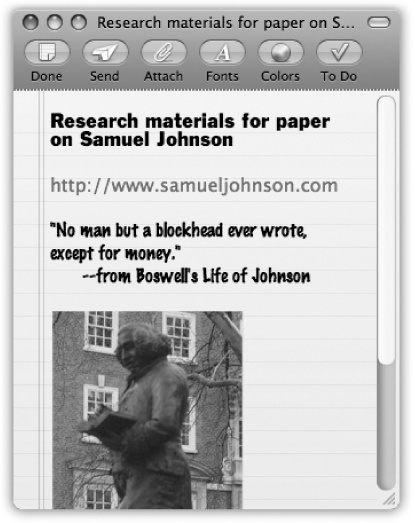

Notes look like actual yellow notepaper with ruled lines, but you can style ’em, save ’em, and even send ’em to your friends. You can type into them, paste into them, and attach pictures to them. And unlike loose scraps of paper or email messages to yourself that may get lost in your mailbox, Notes stay obediently tucked in the Reminders section of the Mailboxes list so you can always find them when you need them.

Tip

Ordinarily, Notes also appear in your Inbox, at the top. If you prefer to keep your Inbox strictly for messages, though, you can remove the Notes. Choose Mail→Preferences→Accounts→Mailbox Behaviors, and then turn off “Store notes in Inbox.” The Notes will still be waiting for you in the side column, down in the Reminders area.

To create a Note, click the Note button on the Mail toolbar. You can also choose File→New Note or press Control-⌘-N to pop up a fresh piece of onscreen paper.

Once you have your Note, type your text and click the Fonts and Colors buttons at the top of the window to style it. To insert a picture, click the Attach button, and then find the photo or graphic on your Mac you want to use. Figure 19-18 shows an example.

Note

You can also attach other kinds of files to a Note—ordinary documents, for example. But you can’t send such Notes to other people—only Notes with pictures.

Figure 19-18. They may look like little pads of scratch paper, but Mail Notes let you paste in Web addresses and photos alongside your typed and formatted text. If you want to share, click the Send button to have the entire Note plop into a new Mail message, ready to be addressed.

When you’re finished with your Note, click Done to save it. When you look for it in the Reminders category of the Mailboxes list, you’ll see that Mail used the first line of the Note as its subject.

To delete a Note for good, select it and press the Delete key.

If you’ve worked hard on this little Note and want to share it, double-click it to open the Note into a new window. Click the Send button on its toolbar. Mail puts the whole thing into a new Mail message—complete with yellow-paper background—so your pal can see how seriously (and stylishly) you take the whole concept of “Note to self.”

You’ve got all this mail piling up with all sorts of things to remember: dinner dates, meeting times, project deadlines, car-service appointments. Wouldn’t it be great if you didn’t have to remember to look through your mailbox to find out what you’re supposed to be doing that day?

It would, and it is, thanks to Mail’s To Do feature. And the best part is that Mail accesses the same To Do list as iCal. The same task list shows up in both programs.

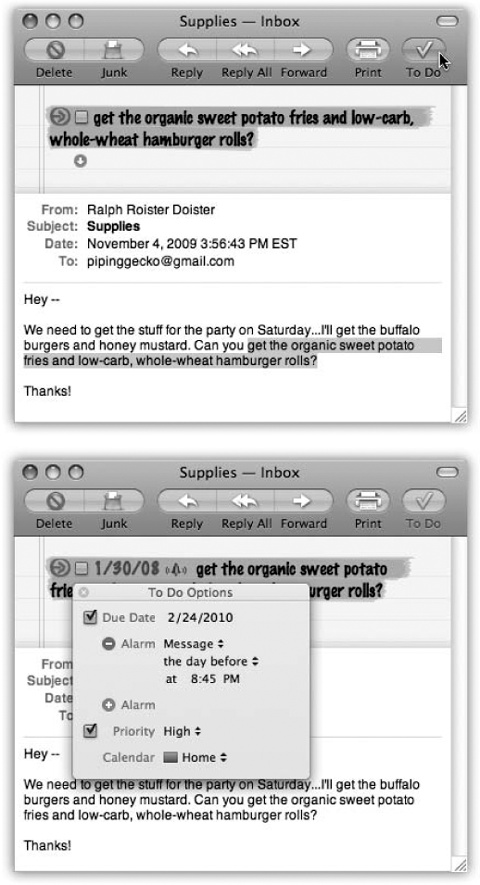

Figure 19-19. Top: If a message brings a task that you need to complete, you can give yourself an extra little reminder, right in Mail. Highlight the pertinent text and click the To Do button to add a large, colorful reminder to the top of the message. Bottom: Click the arrow next to the first line of the To Do for a quick and easy way to set a due date/time and alarm, and also to choose which calendar you want to use for this particular chore.

You can use To Dos in several different ways. For example, when you get an email message that requires further action (“I need the photos for the condo association newsletter by Friday”), highlight the important part of the text. Then do any of these things:

Click To Do in the message window’s toolbar.

Choose File→New To Do.

Press Option-⌘-Y.

Control-click (or right-click) the highlighted text, and then choose New To Do from the shortcut menu.

In each case, Mail pops a copy of the selected text into a yellow strip of note-style paper at the top of the message, as shown in Figure 19-19.

That task is also listed in the Reminders area of the Mailboxes list. If you need to see all the tasks that await you from all your mail accounts, click the flippy triangle to have it spin open and reveal your chores. The number in the gray circle indicates how many To Do items you still need to do.

Tip

Control-click (or right-click) any item in this To Do list to open a shortcut menu that offers useful controls for setting its due date, priority, and calendar (that is, iCal category).

When you click the To Do area of the Mailboxes list, all your tasks are listed in the center of the Mail window. Click the gray arrow after each To Do subject line to jump back to the original message it came from.

Tip

Not all of your life’s urgent tasks spring from email messages. Fortunately, you can create standalone To Dos, too. Just click the To Do button at the top of the Mail window when no message is selected. A blank item appears in your To Do list with the generic name “New To Do.” Select the name to overwrite it with what this reminder is really about: Buy kitty litter TODAY (or whatever).

When you complete a task, click the small checkbox in front of the To Do subject line—either in the message itself or in the Reminders list. Once you’ve marked a task as Done this way, the number of total tasks in the Reminders list goes down by one, and that’s one less thing you have to deal with.

To delete a big yellow To Do banner from a message, point to the left side of the banner until a red handwritten-looking X appears. Click the X to zap the To Do banner from the message.

You can delete a To Do item from the Reminders list by selecting it and then pressing Delete, among other methods.

Seeing your To Do items in Mail is great—when you’re working in Mail. Getting them into iCal is even better, though, because you can see the big picture of an entire day, week, or month. Mail and iCal share the exact same To Do list. Create a To Do in one program, and it shows up instantly in the other one.

Tip

You can even set the due date and priority of a task from within Mail. Those controls are in the To Do Options balloon (Figure 19-19). Open this balloon by Control-clicking the task and choosing Edit To Do, or just click the large arrow button that appears to the left of a To Do banner in an email message window. Later, in iCal, if you double-click a To Do item and then click “Show in Mail,” you get whisked back to the original message, sitting right there in Mail.

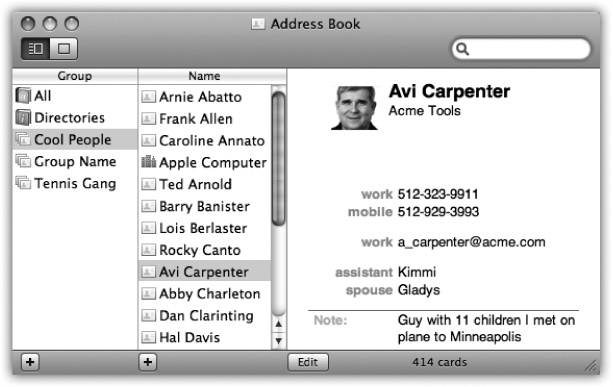

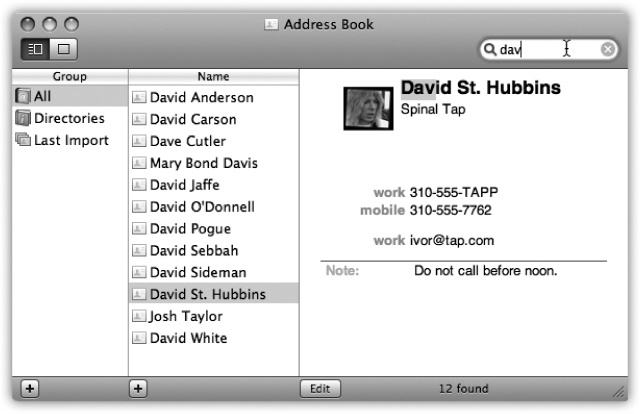

Address Book is Mac OS X’s little-black-book program—an electronic Rolodex where you can stash the names, job titles, addresses, phone numbers, email addresses, and Internet chat screen names of all the people in your life (Figure 19-20). Address Book can also hold related information, like birthdays, anniversaries, and any other tidbits of personal data you’d like to keep at your fingertips.

Figure 19-20. The big question: Why isn’t this program named iContact? With its three-paned view, soft rounded corners, and gradient-gray background, it looks like a close cousin of iPhoto, iCal, and iTunes.

Once you make Address Book the central repository of all your personal contact information, you can call up this information in a number of convenient ways:

You can launch Address Book and search for a contact by typing just a few letters in the Search box.

Regardless of what program you’re in, you can use a single keystroke (F12 is the factory setting, or the

key on aluminum keyboards) to summon the Address Book Dashboard widget. There, you can search for any contact you want. When you’re done, hide the widget with the same quick keystroke.

key on aluminum keyboards) to summon the Address Book Dashboard widget. There, you can search for any contact you want. When you’re done, hide the widget with the same quick keystroke.When you’re composing messages in Mail, Address Book automatically fills in email addresses for you when you type the first few letters.

Tip

If you choose Window→Address Panel (Option-⌘-A) from within Mail, you can browse all your addresses without even launching the Address Book program. Once you’ve selected the people you want to contact, just click the “To:” button to address an email to them—or, if you already have a new email message open, to add them to the recipients.

When you use iChat to exchange instant messages with people in your Address Book, the pictures you’ve stored of them automatically appear in chat windows.

If you’ve bought a subscription to the MobileMe service (Chapter 18), you can synchronize your contacts to the Web so you can see them while you’re away from your Mac. You can also share Address Books with fellow MobileMe members: Choose Address Book→Preferences→Sharing, click the box for “Share your address book,” and then click the

button to add the MobileMe pals you want to share with. You can even send them an invitation to come share your contact list. If you get an invitation yourself, open your own Address Book program and choose Edit→Subscribe to Address Book.

button to add the MobileMe pals you want to share with. You can even send them an invitation to come share your contact list. If you get an invitation yourself, open your own Address Book program and choose Edit→Subscribe to Address Book.Address Book can send its information to an iPod or an iPhone, giving you a “little black book” that fits in your shirt pocket, can be operated one-handed, and comes with built-in musical accompaniment. (To set this up, open iTunes while your iPod or iPhone is connected. Click the iPod/iPhone’s icon; on the Contacts or Info tab, turn on “Synchronize Address Book Contacts.”)

You can find Address Book in your Applications folder or in the Dock.

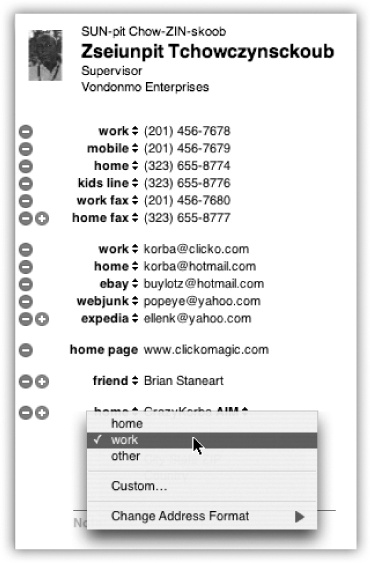

Each entry in Address Book is called a card—like a paper Rolodex card, with predefined spaces to hold all the standard contact information.

To add a new person, choose File→New Card, press ⌘-N, or click the  button beneath the Name column. Then type in the contact information, pressing the Tab key to move from field to field, as shown in Figure 19-21.

button beneath the Name column. Then type in the contact information, pressing the Tab key to move from field to field, as shown in Figure 19-21.

Tip

If you find yourself constantly adding the same fields to new cards, check out the Template pane of Address Book’s Preferences (Address Book→Preferences). There, you can customize exactly which fields appear for new cards.

Each card also contains a free-form Notes field at the bottom, where you can type any other random crumbs of information you’d like to store about the person (pet’s name, embarrassing nicknames, favorite Chinese restaurant, and so on).

Figure 19-21. If one of your contacts happens to have three office phone extensions, a pager number, two home phone lines, a cellphone, and a couple of fax machines, no problem—you can add as many fields as you need. Click the little green  buttons when editing a card to add more phone, email, chat name, and address fields. (The buttons appear only when the existing fields are filled.) Click a field’s name to change its label; you can select one of the standard labels from the pop-up menu (Home, Work, and so on) or make up your own labels by choosing Custom, as seen in the lower portion of this figure. This example shows some unusual fields that you can plug into your address cards. The phonetic first/last name fields (shown at top) let you store phonetic spellings of hard-to-pronounce names. The other fields store screen names for instant messaging networks like Jabber and Yahoo. To add fields like these, choose from the Card→Add Field menu.

buttons when editing a card to add more phone, email, chat name, and address fields. (The buttons appear only when the existing fields are filled.) Click a field’s name to change its label; you can select one of the standard labels from the pop-up menu (Home, Work, and so on) or make up your own labels by choosing Custom, as seen in the lower portion of this figure. This example shows some unusual fields that you can plug into your address cards. The phonetic first/last name fields (shown at top) let you store phonetic spellings of hard-to-pronounce names. The other fields store screen names for instant messaging networks like Jabber and Yahoo. To add fields like these, choose from the Card→Add Field menu.

When you create a new address card, you’re automatically in Edit mode, which means you can add and remove fields and change the information on the card. To switch into Browse Mode (where you can view and copy contact information but not change it), click the Edit button or choose Edit→Edit Card (⌘-L). You can also switch out of Browse Mode in the same ways.

You can also make new contacts in the Address Book right in Mail, saving you the trouble of having to type names and email addresses manually. Select a message in Mail, then choose Message→Add Sender to Address Book (Shift-⌘-Y). Presto: Mac OS X adds a new card to the Address Book, with the name and email address fields already filled in. Later, you can edit the card in Address Book to add phone numbers, street addresses, and so on.

The easiest way to add people to Address Book is to import them from another program like Entourage, Outlook Express, or Palm Desktop.

Address Book isn’t smart enough to read an Entourage or Outlook Express database—it can only import files in vCard format, the less common LDIF format, or tab-separated or comma-separated database files (described next).

It’s a fine art, this importing business; all kinds of things can go wrong. The fields (like Name, Street, Phone) may not be in the right order. Tab-separated export files may not have the right number of empty fields. And so on.

For best results, choose Address Book→Help, and search for “Importing contacts from other applications.” The resulting page gives special tips for each kind of export/ import file format.

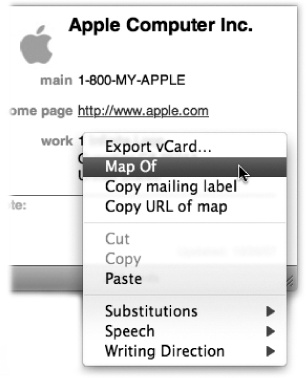

Address Book exchanges contact information with other programs primarily through vCards. vCard is short for virtual business card. More and more email programs send and receive these electronic business cards, which you can identify by their .vcf file name extensions (if, that is, you’ve set your Mac to display these extensions).

If you ever receive an email with a vCard file attached, drag the .vcf file into your Address Book window to create an instant entry with a complete set of information. You can create vCards of your own, too. Just drag a name out of your Address Book and onto the desktop (or into a piece of outgoing mail).

Tip

In addition to letting you create vCards of individual entries, Address Book makes it easy to create vCards that contain several entries. To do so, ⌘-click the entries in the Name column that you want included, and drag them to the desktop. There, they’ll appear all together as a single vCard. You can even drag an item from the Group column to the desktop to make a vCard that contains all the group’s entries.