For the first 20 years of the Mac’s existence, you began your workday by double-clicking the Macintosh HD icon in the upper-right corner of the screen. That’s where you kept your files.

These days, though, you’d be disappointed if you did that. All you’ll find in the Macintosh HD window is a set of folders called Applications, Library, Users, and so on—folders you didn’t put there.

Most of these folders aren’t very useful to you, the Mac’s human companion. They’re there for Mac OS X’s own use—which is why, in Snow Leopard, the Macintosh HD icon doesn’t even appear on the screen. (At least not at first; you can choose Find-er→Preferences and turn the “Hard disks” checkbox back on, if you really want to.) Think of your main hard drive window as storage for the operating system itself, which you’ll access only for occasional administrative purposes.

So where is your nest of files, folders, and so on? All of it, everything of yours on this computer, lives in the Home folder. That’s a folder bearing your name (or whatever name you typed in when you installed Mac OS X).

Mac OS X is rife with shortcuts for opening this all-important folder:

Choose Go→Home, or press Shift-⌘-H.

In the Sidebar (Windows and How to Work Them), click the

icon.

icon.In the Dock, click the Home icon. (If you don’t see one, consult Conduct Speed Tests for instructions on how to put one there.)

Press ⌘-N, or choose File→New Finder Window. (If your Home folder doesn’t open when you do that, see The Finder Toolbar.)

All these steps open your Home folder directly.

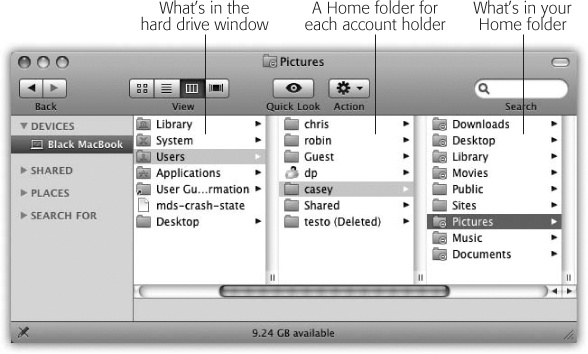

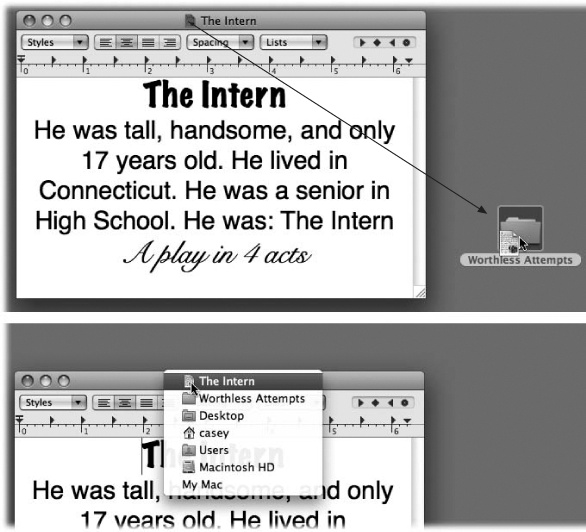

If you’re the compulsive sort, you can also navigate to it the long way: Double-click the Users folder, and then double-click the folder inside it that bears your name and looks like a house (see Figure 2-1).

Figure 2-1. This is it: the folder structure of Mac OS X. It’s not so bad, really. For the most part, what you care about are the Applications folder in the main hard drive window and your own Home folder. You’re welcome to save your documents and park your icons almost anywhere on your Mac (except inside the System folder or in other people’s Home folders). But keeping your work in your Home folder makes backing up and file sharing easier.

So why has Apple demoted your files to a folder three levels deep? The answer may send you through the five stages of grief—Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression, and finally Acceptance—but if you’re willing to go through it, much of the mystery surrounding Mac OS X will fade away.

Mac OS X has been designed from the ground up for computer sharing. It’s ideal for any situation where different family members, students, or workers share the same Mac.

Each person who uses the computer will turn on the machine to find his own separate desktop picture, set of files, Web bookmarks, font collection, and preference settings. (You’ll find much more about user accounts in Chapter 12.)

Like it or not, Mac OS X considers you one of these people. If you’re the only one who uses this Mac, fine—simply ignore the sharing features. (You can also ignore all that business at the beginning of Chapter 1 about logging in.) But in its little software head, Mac OS X still considers you an account holder and stands ready to accommodate any others who should come along.

In any case, now you should see the importance of the Users folder in the main hard drive window. Inside are folders—the Home folders—named for the different people who use this Mac. In general, nobody is allowed to touch what’s inside anybody else’s folder.

If you’re the sole proprietor of the machine, of course, there’s only one Home folder in the Users folder—named for you. (The Shared folder doesn’t count; it’s described on Logging Out.)

This is only the first of many examples in which Mac OS X imposes a fairly rigid folder structure. Still, the approach has its advantages. By keeping such tight control over which files go where, Mac OS X keeps itself pure—and very, very stable. Other operating systems known for their stability, including Windows XP, Windows Vista, and Windows 7, work the same way.

Furthermore, keeping all your stuff in a single folder makes it very easy for you to back up your work. It also makes life easier when you try to connect to your machine from elsewhere in the office (over the network) or elsewhere in the world (over the Internet), as described in Chapter 22.

If you did want to explore the entirety of Mac OS X, to examine the contents of your hard drive (choose Go→Computer and double-click “Macintosh HD”), you’d find the following folders in the main hard drive window:

Applications. The Applications folder, of course, contains the complete collection of Mac OS X programs on your Mac (not counting the invisible Unix ones). Even so, you’ll rarely launch programs by opening this folder; the Dock is a far more efficient launcher, as described in Chapter 4.

Desktop. This folder stores icons that appear on the Mac OS X desktop. The difference is that you don’t control this one; Apple does. Anything in here also appears on your desktop. (This Apple-controlled one is usually empty.)

Library. This folder bears more than a passing resemblance to the System Folder subfolders of Macs gone by, or the Windows folder on PCs. It stores components for the operating system and your programs (sounds, fonts, preferences, help files, printer drivers, modem scripts, and so on).

System. This is Unix, baby. These are the actual files that turn on your Mac and control its operations. You’ll rarely have any business messing with this folder, which is why Apple made almost all of its contents invisible.

User Guides And Information. Here’s a link to a folder that contains random Getting Started guides from Apple, including a Welcome to Snow Leopard booklet.

Users. As noted earlier, this folder stores the Home folders for everyone who uses this machine.

Your old junk. If you upgraded your Mac from an earlier Mac operating system, then your main hard drive window also lists whatever folders you kept there.

Within the folder that bears your name, you’ll find another set of standard Mac folders. (You can tell the Mac considers them holy because they have special logos on their folder icons.) Except as noted, you’re free to rename or delete them; Mac OS X creates the following folders solely as a convenience:

Desktop. When you drag an icon out of a folder or disk window and onto your Mac OS X desktop, it may appear to show up on the desktop. But that’s just an optical illusion, a visual convenience. In truth, nothing in Mac OS X is really on the desktop. It’s actually in this Desktop folder, and mirrored on the desktop area.

The reason is simple enough: Everyone who shares your machine will, upon logging in, see his own stuff sitting on the desktop. Now you know how Mac OS X does it: There’s a separate Desktop folder in every person’s Home folder.

Tip

The fact that the desktop is actually a folder is handy, because it gives you a sneaky way to jump to your Home folder from anywhere. Simply click the desktop background and then press ⌘-↑ (which is the keystroke for Go→Enclosing Folder; pay no attention to the fact that the command is dimmed at the moment). Because that keystroke means “open whatever folder contains the one I’m examining,” it instantly opens your Home folder. (Your Home folder is, of course, the “parent” of your Desktop folder.)

Documents. Apple suggests that you keep your actual work files in this folder. Sure enough, whenever you save a new document (when you’re working in Keynote or Word, for example), the Save As box proposes storing the new file in this folder, as described in Chapter 5.

Your programs may also create folders of their own here. For example, you may find a Microsoft User Data folder for your Entourage email, a Windows folder for use with Parallels or VMWare Fusion (Chapter 8), and so on.

Library. As noted earlier, the main Library folder (the one in your main hard drive window) contains folders for fonts, preferences, help files, and so on.

You have your own Library folder, too, right there in your Home folder. It stores the same kinds of things—but they’re your fonts, your preferences.

Once again, this setup may seem redundant if you’re the only person who uses your Mac. But it makes perfect sense in the context of families, schools, or offices where numerous people share a single machine. Because you have your own Library folder, you can have a font collection that’s “installed” on the Mac only when you’re using it. Each person’s program preference files are stored independently, too (the files that determine where Photoshop’s palettes appear, and so on). And each person, of course, sees his own email when launching Mac OS X’s Mail program (Chapter 19)—because mail, too, is generally stored in the personal Library folder.

Other Library folders store your Favorites, Web browser plug-ins and cached Web pages, keyboard layouts, sound files, and so on. (It’s best not to move or rename Library folders.)

Movies, Music, Pictures. The various Mac OS X programs that deal with movies, music, and pictures will propose these specialized folders as storage locations. For example, when you plug a digital camera into a Mac, the iPhoto program automatically begins to download the photos on it—and stores them in the Pictures folder. Similarly, iMovie is programmed to look for the Movies folder when saving its files, and iTunes stores its MP3 files in the Music folder.

Public. If you’re on a network, or if others use the same Mac when you’re not around, this folder can be handy: It’s the “Any of you guys can look at these files” folder. Other people on your network, as well as other people who sit down at this machine, are allowed to see whatever you’ve put in here, even if they don’t have your password. (If your Mac isn’t on an office network and isn’t shared, you can throw away this folder.) Details on sharing the Mac are in Chapter 12, and those on networking are in Chapter 13.

Sites. Mac OS X has a built-in Web server, software that turns your Mac into a Web site that people on your network—or, via the Internet, all over the world—can connect to. This Mac OS X feature relies on a program called the Apache Web server, which is so highly regarded in the Unix community that programmers lower their voices when they mention it.

Details of the Web server are in Chapter 22. For now, though, note that this is the folder where you will put the actual Web pages you want to make available to the Internet at large.

Every document, program, folder, and disk on your Mac is represented by an icon: a colorful little picture that you can move, copy, or double-click to open. In Mac OS X, icons look more like photos than cartoons, and you can scale them to practically any size.

A Mac OS X icon’s name can have up to 255 letters and spaces. If you’re accustomed to the 31-character or even eight-character limits of older computers, that’s quite a luxurious ceiling.

If you’re used to Windows, you may be delighted to discover that in Mac OS X, you can name your files using letters, numbers, punctuation—in fact, any symbol except the colon (:), which the Mac uses behind the scenes for its own folder-hierarchy designation purposes. And you can’t use a period to begin a file’s name.

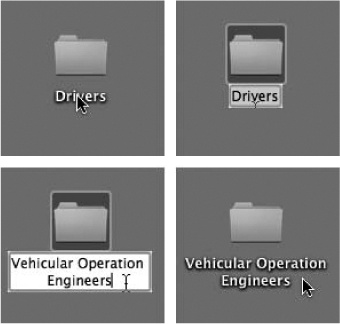

To rename a file, click its name or icon (to highlight it) and then press Return. (Or, if you have time to kill, click once on the name, wait a moment, and then click a second time.)

In any case, a rectangle appears around the name (Figure 2-2). At this point, the existing name is highlighted; just begin typing to replace it. If you type a very long name, the rectangle grows vertically to accommodate new lines of text.

Tip

If you simply want to add letters to the beginning or end of the file’s existing name, press the ← or → key immediately after pressing Return. The insertion point jumps to the beginning or end of the file name.

You can give more than one file or folder the same name, as long as they’re not in the same folder. For example, you can have as many files named “Chocolate Cake Recipe” as you like, provided each is in a different folder. And, of course, files called Recipe. doc and Recipe.xls can coexist in a folder, too.

Figure 2-2. Click an icon’s name (top left) to produce the renaming rectangle (top right), in which you can edit the file’s name. Snow Leopard is kind enough to highlight only the existing name, and not the suffix (like .jpg or .doc). Now begin typing to replace the existing name (bottom left). When you’re finished typing, press Return, Enter, or Tab to seal the deal, or just click somewhere else.

As you edit a file’s name, remember that you can use the Cut, Copy, and Paste commands in the Edit menu to move selected bits of text around, just as though you were word processing. The Paste command can be useful when, for instance, you’re renaming many icons in sequence (Quarterly Estimate 1, Quarterly Estimate 2…).

And now, a few tips about renaming icons:

When the Finder sorts files, a space is considered alphabetically before the letter A. To force a particular file or folder to appear at the top of a list view window, insert a space (or an underscore) before its name.

Older operating systems sort files so that 10 and 100 come before 2, the numbers 30 and 300 come before 4, and so on. You wind up with alphabetically sorted files like this: “1. Big Day,” “10. Long Song,” “2. Floppy Hat,” “20. Dog Bone,” “3. Weird Sort,” and so on. Generations of computer users have learned to put zeros in front of their single-digit numbers just to make the sorting look right.

In Mac OS X, though, you get exactly the numerical list you’d hope for: “1. Big Day,” “2. Floppy Hat,” “3. Weird Sort,” “10. Long Song,” and “20. Dog Bone.”

In addition to letters and numbers, Mac OS X also assigns punctuation marks an “alphabetical order,” which is this: ` (the accent mark above the Tab key), ^, _, -, space, –, —, comma, semicolon, !, ?, ‘, “, (,), [, ], {, }, @, *, /, &, #, %, +, <, =, ≠, >, |, ~, and $.

Numbers come after punctuation; letters come next; and bringing up the rear are these characters: μ (Option-M); π (Option-P); Ω (Option-Z), and

(Shift-Option-K).

(Shift-Option-K).When it comes time to rename files en masse, add-on shareware can help you. A Better Finder Rename, for example, lets you manipulate file names in a batch—numbering them, correcting a spelling in dozens of files at once, deleting a certain phrase from their names, and so on. You can download this shareware from this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com.

To highlight a single icon in preparation for printing, opening, duplicating, or deleting, click the icon once. (In a list or column view, as described in Chapter 1, you can also click on any visible piece of information about that file—its size, kind, date modified, and so on.) Both the icon and the name darken in a uniquely Snow Leopardish way.

Tip

You can change the color of the oval highlighting that appears around the name of a selected icon. Choose  →System Preferences, click Appearance, and use the Highlight Color pop-up menu.

→System Preferences, click Appearance, and use the Highlight Color pop-up menu.

That much may seem obvious. But most first-time Mac users have no idea how to manipulate more than one icon at a time—an essential survival skill in a graphic interface like the Mac’s.

Figure 2-3. You can highlight several icons simultaneously by dragging a box around them. To do so, drag from outside the target icons diagonally across them (right), creating a translucent gray rectangle as you go. Any icons or icon names touched by this rectangle are selected when you release the mouse.If you press the Shift or ⌘ key as you do this, then any previously highlighted icons remain selected.

To highlight multiple files in preparation for moving or copying, use one of these techniques:

To highlight all the icons. To select all the icons in a window, press ⌘-A (the equivalent of the Edit→Select All command).

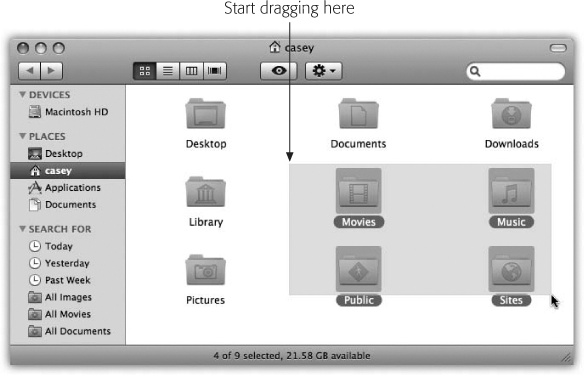

To highlight several icons by dragging. You can drag diagonally to highlight a group of nearby icons, as shown in Figure 2-3. In a list view, in fact, you don’t even have to drag over the icons themselves—your cursor can touch any part of any file’s row, like its modification date or file size.

To highlight consecutive icons in a list. If you’re looking at the contents of a window in list view or column view, you can drag vertically over the file and folder names to highlight a group of consecutive icons, as described above. (Begin the drag in a blank spot.)

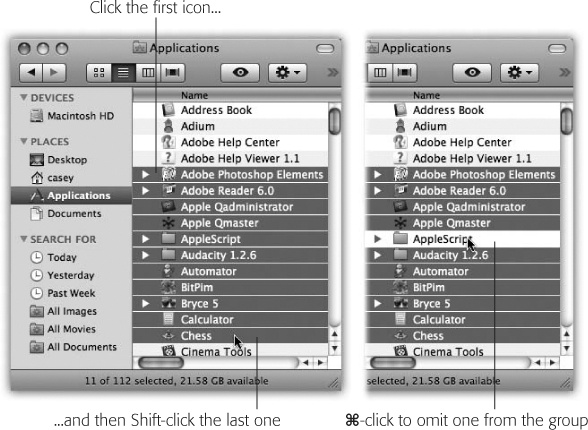

There’s a faster way to do the same thing: Click the first icon you want to highlight, and then Shift-click the last file. All the files in between are automatically selected, along with the two icons you clicked. Figure 2-4 illustrates the idea.

Figure 2-4. Left: To select a block of files in list view, click the first icon. Then, while pressing Shift, click the last one. Mac OS X highlights all the files in between your clicks. This technique mirrors the way Shift-clicking works in a word processor and in many other kinds of programs. Right: To remove one of the icons from your selection, ⌘-click it.

To highlight random icons. If you want to highlight only the first, third, and seventh icons in a window, for example, start by clicking icon No. 1. Then ⌘-click each of the others (or ⌘-drag new rectangles around them). Each icon darkens to show that you’ve selected it.

If you’re highlighting a long string of icons and click one by mistake, you don’t have to start over. Instead, just ⌘-click it again so the dark highlighting disappears. (If you do want to start over, you can deselect all selected icons by clicking any empty part of the window—or by pressing the Esc key.) The ⌘ key trick is especially handy if you want to select almost all the icons in a window. Press ⌘-A to select everything in the folder, then ⌘-click any unwanted icons to deselect them.

Tip

In icon view, you can either Shift-click or ⌘-click to select multiple individual icons. But you may as well just learn to use the ⌘ key when selecting individual icons. That way you won’t have to use a different key in each view.

Once you’ve highlighted multiple icons, you can manipulate them all at once. For example, you can drag them en masse to another folder or disk by dragging any one of the highlighted icons. All other highlighted icons go along for the ride. This technique is especially useful when you want to back up a bunch of files by dragging them onto a different disk, delete them all by dragging them to the Trash, and so on.

When multiple icons are selected, the commands in the File and Edit menus—like Duplicate, Open, and Make Alias—apply to all of them simultaneously.

For the speed fanatic, using the mouse to click an icon is a hopeless waste of time. Fortunately, you can also select an icon by typing the first few letters of its name.

When looking at your Home window, for example, you can type M to highlight the Movies folder. And if you actually intended to highlight the Music folder instead, then press the Tab key to highlight the next icon in the window alphabetically. Shift-Tab highlights the previous icon alphabetically. Or use the arrow keys to highlight a neighboring icon.

(The Tab-key trick works only in icon, list, and Cover Flow views—not column view, alas. You can always use the← and → keys to highlight adjacent columns, however.)

After highlighting an icon this way, you can manipulate it using the commands in the File menu or their keyboard equivalents: Open (⌘-O), put it into the Trash (⌘-Delete), Get Info (⌘-I), Duplicate (⌘-D), or make an alias (⌘-L), as described later in this chapter. By turning on the special disability features described on Mouse & Trackpad Tab (Cursor Control from the Keyboard), you can even move the highlighted icon using only the keyboard.

If you’re a first-time Mac user, you may find it excessively nerdy to memorize keystrokes for functions that the mouse performs perfectly well. If you make your living using the Mac, however, memorizing these keystrokes will reward you immeasurably with speed and efficiency.

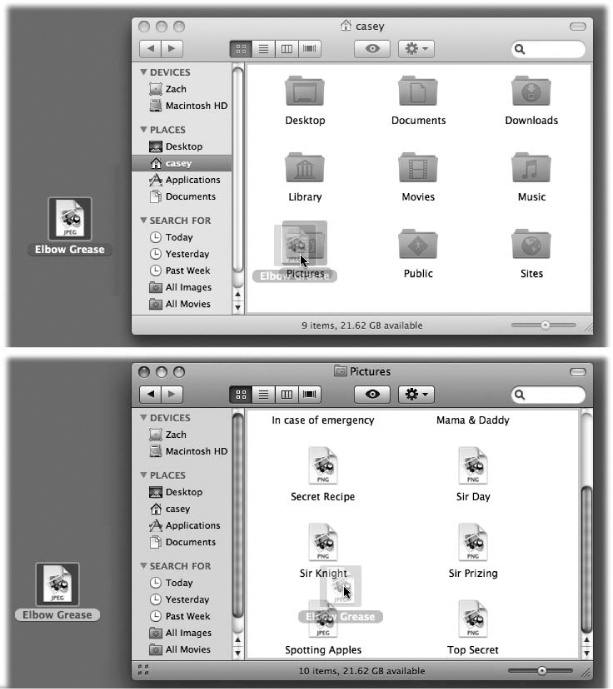

In Mac OS X, there are two ways to move or copy icons from one place to another: by dragging them and by using the Copy and Paste commands.

You can drag icons from one folder to another, from one drive to another, from a drive to a folder on another drive, and so on. (When you’ve selected several icons, drag any one of them; the others tag along.) While the Mac is copying, you can tell that the process is under way even if the progress bar is hidden behind a window, because the icon of the copied material shows up dimmed in its new home, darkening only when the copying process is over. (You can also tell because Snow Leopard’s progress box is a lot clearer and prettier than it used to be.) You can cancel the process by pressing either ⌘-period or the Esc key.

Tip

If you’re copying files into a disk or folder that already contains items with the same names, Mac OS X asks you individually about each one. (“An older item named ‘Fiddlesticks’ with extension ‘.doc’ already exists in this location.”) Note that, thank heaven, Mac OS X tells you whether the version you’re replacing is older or newer than the one you’re moving.

Turn on “Apply to all” if all the incoming icons should (or should not) replace the old ones of the same names. Then click Replace or Don’t Replace, as you see fit—or Stop to halt the whole copying business.

Understanding when the Mac copies a dragged icon and when it moves it bewilders many a beginner. However, the scheme is fairly simple (see Figure 2-5) when you consider the following:

Dragging from one folder to another on the same disk moves the icon.

Dragging from one disk (or disk partition) to another copies the folder or file. (You can drag icons either into an open window or directly onto a disk or folder icon.)

If you press the Option key as you release an icon you’ve dragged, you copy the icon instead of moving it. Doing so within a single folder produces a duplicate of the file called “[Whatever its name was] copy.”

If you press the ⌘ key as you release an icon you’ve dragged from one disk to another, you move the file or folder, in the process deleting it from the original disk.

Tip

This business of pressing Option or ⌘ after you begin dragging is a tad awkward, but it has its charms. For example, it means you can change your mind about the purpose of your drag in mid-movement, without having to drag back and start over.

And if it turns out you just dragged something into the wrong window or folder, a quick ⌘-Z (the shortcut for Edit→Undo) puts it right back where it came from.

Dragging icons to copy or move them probably feels good because it’s so direct: You actually see your arrow cursor pushing the icons into the new location.

But you pay a price for this satisfying illusion. You may have to spend a moment or two fiddling with your windows to create a clear “line of drag” between the icon to be moved and the destination folder. (A background window will courteously pop to the foreground to accept your drag. But if it wasn’t even open to begin with, you’re out of luck.)

There’s a better way. Use the Copy and Paste commands to move icons from one window into another (just as you can in Windows, by the way—except that you can only copy, not cut, Mac icons). The routine goes like this:

Highlight the icon or icons you want to move.

Use any of the techniques described starting on Selecting Icons.

Choose Edit→Copy.

Or press the keyboard shortcut: ⌘-C.

Open the window where you want to put the icons. Choose Edit→Paste.

Once again, you may prefer to use the keyboard equivalent: ⌘-V. And once again, you can also Control-click (right-click) inside the window and then choose Paste from the shortcut menu that appears, or you can use the

menu.

menu.A progress bar may appear as Mac OS X copies the files or folders; press Esc or ⌘-period to interrupt the process. When the progress bar goes away, it means you’ve successfully transferred the icons, which now appear in the new window.

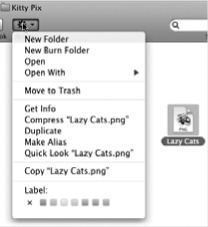

You may remember from Chapter 1 that the title bar of every Finder window harbors a secret pop-up menu. When you ⌘-click it, you’re shown a little folder ladder that delineates your current position in the folder hierarchy. You may also remember that the tiny icon just to the left of the window’s name is actually a handle that you can drag to move a folder into a different window.

Figure 2-5. Top: By dragging the document-window proxy icon, you can create an alias of your document on the desktop or anywhere else. (Make sure the icon has darkened before you begin to drag.) Bottom: If you ⌘-click the name of the document in its title bar, you get to see exactly where this document sits on your hard drive. (Choosing the name of one of these folders opens that folder and switches you to the Finder.)

In many programs, you get the same features in document windows, as shown in Figure 2-5. For example, by dragging the tiny document icon next to the document’s name, you can perform these two interesting stunts:

Create an alias on the desktop or the Dock. By dragging this icon to the desktop or onto a folder or disk icon, you create an instant alias of the document you’re working on. (If you drag into the right end of the Dock, you can park the document’s icon there, too.) This is a useful feature when, for example, you’re about to knock off for the night, and you want easy access to the file you’ve been working on when you return the next day.

Launch from a Dock icon. By dragging this title-bar icon onto another program’s Dock icon, you open your document in that other program. For example, if you’re in TextEdit working on a memo and you decide that you’ll need the full strength of Microsoft Word to dress it up, you can drag its title-bar icon directly onto the Word icon in the Dock. Word then launches and opens up the TextEdit document, ready for editing.

Note to struggling writers: Unfortunately, you can’t drag an open document directly into the Trash.

Here’s a common dilemma: You want to drag an icon not just into a folder, but into a folder nested inside that folder. This awkward challenge would ordinarily require you to open the folder, open the inner folder, drag the icon in, and then close both windows. As you can imagine, the process is even messier if you want to drag an icon into a sub-subfolder or a sub-sub-subfolder.

Instead of fiddling around with all those windows, you can instead use the spring-loaded folders feature (Figure 2-6).

It works like this: With a single drag, drag the icon onto the first folder—but keep your mouse button pressed. After a few seconds, the folder window opens automatically, centered on your cursor:

In icon view, the new window instantly replaces the original.

In column view, you get a new column that shows the target folder’s contents.

In list and Cover Flow views, a second window appears.

Still keeping the button down, drag onto the inner folder; its window opens, too. Now drag onto the inner inner folder—and so on. (If the inner folder you intend to open isn’t visible in the window, you can scroll by dragging your cursor close to any edge of the window.)

Tip

You can even drag icons onto disks or folders whose icons appear in the Sidebar (Chapter 1). When you do so, the main part of the window flashes to reveal the contents of the disk or folder you’ve dragged onto. When you let go of the mouse, the main window changes back to reveal the contents of the disk or folder where you started dragging.

In short, Sidebar combined with spring-loaded folders makes a terrific drag-and-drop way to file a desktop icon from anywhere to anywhere—without having to open or close any windows at all.

Figure 2-6. Top: To make spring-loaded folders work, start by dragging an icon onto a folder or disk icon. Don’t release the mouse button. Wait for the window to open automatically around your cursor. Bottom: Now you can either let go of the mouse button to release the file in its new window or drag it onto yet another, inner folder. It, too, will open. As long as you don’t release the mouse button, you can continue until you’ve reached your folder-within-a-folder destination.

When you finally release the mouse, you’re left facing the final window. All the previous windows closed along the way. You’ve neatly placed the icon into the depths of the nested folders.

That spring-loaded folder technique sounds good in theory, but it can be disconcerting in practice. For most people, the long wait before the first folder opens is almost enough wasted time to negate the value of the feature altogether. Furthermore, when the first window finally does open, you’re often caught by surprise. Suddenly your cursor—mouse button still down—is inside a window, sometimes directly on top of another folder you never intended to open. But before you can react, its window, too, has opened, and you find yourself out of control.

Fortunately, you can regain control of spring-loaded folders using these tricks:

Choose Finder→Preferences. On the General pane, adjust the “Spring-loaded folders and windows” delay slider to a setting that drives you less crazy. For example, if you find yourself waiting too long before the first folder opens, then drag the slider toward the Short setting.

You can turn off this feature entirely by choosing Finder→Preferences and turning off the “Spring-loaded folders and windows” checkbox.

Tap the space bar to make the folder spring open at your command. That is, even with the Finder→Preferences slider set to the Long delay setting, you can force each folder to spring open when you are ready by tapping the space bar as you hold down the mouse button. True, you need two hands to master this one, but the control you regain is immeasurable.

Whenever a folder springs open into a window, twitch your mouse up to the newly opened window’s title bar or down to its information strip. Doing so ensures that your cursor won’t wind up hovering on, and accidentally opening, an inner folder. With the cursor parked on the gradient gray, you can take your time to survey the newly opened window’s contents, and plunge into an inner folder only after gaining your bearings.

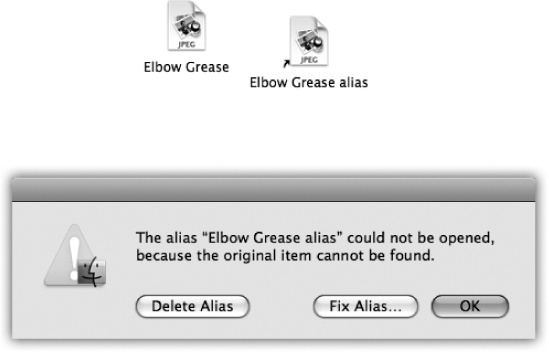

Highlighting an icon and then choosing File→Make Alias (or pressing ⌘-L) generates an alias, a specially branded duplicate of the original icon (Figure 2-7). It’s not a duplicate of the file—just of the icon; therefore it requires negligible storage space. When you double-click the alias, the original file opens. (A Macintosh alias is essentially the same as a Windows shortcut.)

Figure 2-7. Top: You can identify an alias by the tiny arrow badge on the lower-left corner. (Longtime Mac fans should note that the name no longer appears in italics.) Bottom: If the alias can’t find the original file, you’re offered the chance to hook it up to a different file.

You can create as many aliases as you want of a single file; therefore, in effect, aliases let you stash that file in many different folder locations simultaneously. Double-click any one of them and you open the original file, wherever it may be on your system.

Tip

You can also create an alias of an icon by Option-⌘-dragging it out of its window. (Aliases you create this way lack the word alias on the file name—a distinct delight to those who find the suffix redundant and annoying.) You can also create an alias by Control-clicking (or right-clicking) a normal icon and choosing Make Alias from the shortcut menu that appears, or by highlighting an icon and then choosing Make Alias from the  menu.

menu.

An alias takes up very little disk space, even if the original file is enormous. Aliases are smart, too: Even if you rename the alias, rename the original file, move the alias, and move the original around on the disk, double-clicking the alias still opens the original file.

And that’s just the beginning of alias intelligence. Suppose you make an alias of a file that’s on a removable disc, like a CD. When you double-click the alias on your hard drive, the Mac requests that particular disc by name. And if you double-click the alias of a file on a different machine on the network, your Mac attempts to connect to the appropriate machine, prompting you for a password (see Chapter 13)—even if the other machine is thousands of miles away and your Mac must go online to connect.

Here are a couple of ways you can put aliases to work:

You may want to file a document you’re working on in several different folders, or place a particular folder in several different locations.

You can use the alias feature to save you some of the steps required to access another hard drive on the network. (Details on this trick are in Chapter 13.)

Tip

Mac OS X makes it easy to find the file an alias “points to” without actually having to open it. Just highlight the alias and then choose File→Show Original (⌘-R), or choose Show Original from the  menu. Mac OS X immediately displays the actual, original file, sitting patiently in its folder, wherever that may be.

menu. Mac OS X immediately displays the actual, original file, sitting patiently in its folder, wherever that may be.

An alias doesn’t contain any of the information you’ve typed or composed in the original file. Don’t email an alias to the Tokyo office and then depart for the airport, hoping to give the presentation upon your arrival in Japan. When you double-click the alias, now separated from its original, you’ll be shown the dialog box at the bottom of Figure 2-7.

If you find yourself 3,000 miles away from the hard drive on which the original file resides, click Delete Alias (to delete the orphan alias) or OK (to do nothing, leaving it where it is).

In certain circumstances, however, the third button—Fix Alias—is the most useful. Click it to summon the Fix Alias dialog box, which you can use to navigate the folders on your Mac. When you click a new icon and then click Choose, you associate the orphaned alias with a different file.

Such techniques become handy when, for example, you click your book manuscript’s alias on the desktop, forgetting that you recently saved it under a new name and deleted the older draft. Instead of simply showing you an error message that says “‘Enron Corporate Ethics Handbook’ can’t be found,” the Mac displays the box that contains the Fix Alias button. By reassociating the alias with the new document, you can save yourself the trouble of creating a new alias. From now on, double-clicking your manuscript’s alias on the desktop opens the new draft.

Tip

You don’t have to wait until the original file no longer exists before choosing a new original for an alias. You can perform alias reassignment surgery anytime you like. Just highlight the alias icon and then choose File→Get Info. In the Get Info dialog box, click Select New Original. In the resulting window, find and double-click the file you’d now like to open whenever you double-click the alias.

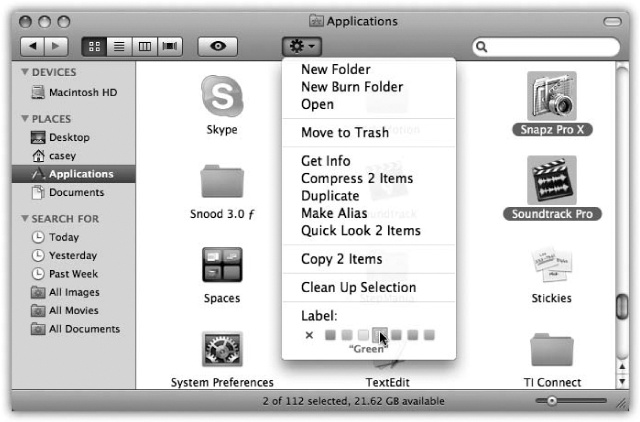

Snow Leopard includes a welcome blast from the Mac’s distant past: icon labels. This feature lets you tag selected icons with one of seven different labels, each of which has both a text label and a color associated with it.

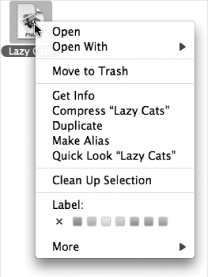

To do so, highlight the icons. Open the File menu (or the  menu, or the shortcut menu that appears when you Control-click/right-click the icons). There, under the heading Color Label, you’ll see seven colored dots, which represent the seven labels you can use. Figure 2-8 shows the routine.

menu, or the shortcut menu that appears when you Control-click/right-click the icons). There, under the heading Color Label, you’ll see seven colored dots, which represent the seven labels you can use. Figure 2-8 shows the routine.

After you’ve applied labels to icons, you can perform some unique file-management tasks—in some cases on all of them simultaneously, even if they’re scattered across multiple hard drives. For example:

Round up files with Find. Using the Find command described in Chapter 3, you can round up all the icons with a particular label. Thereafter, moving these icons at once is a piece of cake—choose Edit→Select All, and then drag any one of the highlighted icons out of the results window and into the target folder or disk.

Figure 2-8. Use the File menu,

menu, or shortcut menu to apply label tags to highlighted icons. You can even apply a label within an icon’s Get Info dialog box (page 88). Instantly, the icon’s name takes on the selected shade. In a list or column view, the entire row takes on that shade, as shown in Figure 2-9. (If you choose the little X, you remove any labels you may have applied.)

menu, or shortcut menu to apply label tags to highlighted icons. You can even apply a label within an icon’s Get Info dialog box (page 88). Instantly, the icon’s name takes on the selected shade. In a list or column view, the entire row takes on that shade, as shown in Figure 2-9. (If you choose the little X, you remove any labels you may have applied.)Using labels in conjunction with Find like this is one of the most useful and inexpensive backup schemes ever devised: Whenever you finish working on a document that you’d like to back up, Control-click it and apply a label called, for example, Backup. At the end of each day, use the Find command to round up all the files with the Backup label—and then drag them as a group onto your backup disk.

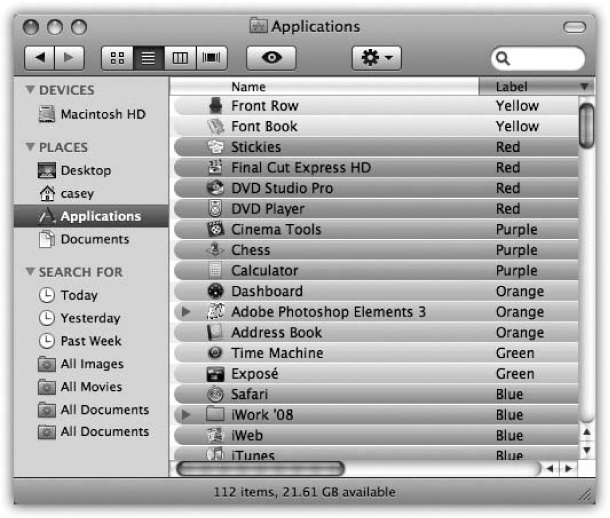

Sort a list view by label. No other Mac sorting method lets you create an arbitrary order for the icons in a window. When you sort by label, the Mac creates alphabetical clusters within each label grouping, as shown in Figure 2-9.

This technique might be useful when, for example, your job is to process several different folders of documents; for each folder, you’re supposed to convert graphics files, throw out old files, or whatever. As soon as you finish working your way through one folder, flag it with a label called Done. The folder jumps to the top (or bottom) of the window, safely marked for your reference pleasure, leaving the next unprocessed folder at your fingertips, ready to go.

Track progress. Use different-colored labels to track the status of files in a certain project. For example, the first drafts have no labels at all. Once they’ve been edited and approved, make them blue. Once they’ve been sent to the home office, make them purple. (Heck, you could have all kinds of fun with this: Money-losing projects get red tints; profitable ones get green; things that make you sad are blue. Or maybe not.)

Figure 2-9. Sorting by label lets you create several different alphabetical groups within a single window. In Snow Leopard, in fact, you can sort by labels in any view using the View→Show View Options palette. In a list view, the quickest way to sort by label is to first make the label column visible. Do so by choosing View→Show View Options and then turning on the Label checkbox.

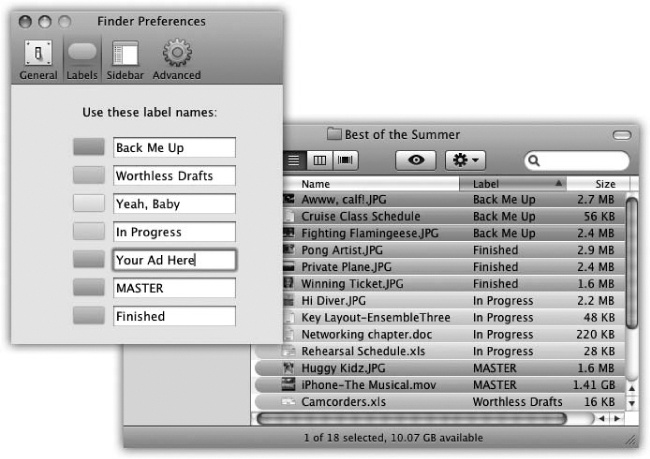

When you install Mac OS X, the seven labels in the File menu are named for the colors they show: Red, Orange, Yellow, and so on. Clearly, the label feature would be much more useful if you could rewrite these labels, tailoring them to your purposes.

Doing so is easy. Choose Finder→Preferences. Click Labels. Now you see the dialog box shown in Figure 2-10, where you can edit the text of each label.

No single element of the Macintosh interface is as recognizable or famous as the Trash icon, which now appears at the end of the Dock.

You can discard almost any icon by dragging it into the Trash can (actually a waste-basket, not a can, but let’s not quibble). When the tip of your arrow cursor touches the Trash icon, the little wastebasket turns black. When you release the mouse, you’re well on your way to discarding whatever it was you dragged. As a convenience, Mac OS X even replaces the empty-wastebasket icon with a wastebasket-filled-with-crumpled-up-papers icon, to let you know there’s something in there.

It’s well worth learning the keyboard alternative to dragging something into the Trash: Highlight the icon, and then press ⌘-Delete (which corresponds to the File→Move to Trash command). This technique is not only far faster than dragging, but it also requires far less precision, especially if you have a large screen. Mac OS X does all the Trash-targeting for you.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: If a file is locked (Locked Files: The Next Generation), a message appears to let you know; it offers you the chance to fling it into the Trash anyway. That’s a better solution than before, when you’d be forced to unlock the file before you could trash it.

Figure 2-10. Top left: In the Labels tab of the Preferences dialog box, you can change the predefined label text. Each label can be up to 31 letters and spaces long. Bottom right: Now your list and column views reveal meaningful text tags instead of color names.

File and folder icons sit in the Trash forever—or until you choose Finder→Empty Trash, whichever comes first.

If you haven’t yet emptied the Trash, you can open its window by clicking the waste-basket icon once. Now you can review its contents: icons that you’ve placed on the waiting list for extinction. If you change your mind, you can rescue any of these items in any of these ways:

Use the new Put Back command. This feature, new in Snow Leopard, flings the trashed item back into whatever folder it came from, even if that was weeks ago. (Well, sort of new—it’s been in Windows for years, and was in Mac OS 9 before that.)

You’ll find the Put Back command wherever fine shortcut menus are sold. For example, it appears when you Control-click the icon, right-click it, or click the icon and then open the

menu.

menu.Hit Undo. If dragging something to the Trash was the most recent thing you’ve done, you can press ⌘-Z—the keyboard shortcut for the Edit→Undo command. That keystroke not only removes it from the Trash, but also returns it to the folder from which it came. This trick works even if the Trash window isn’t open.

Drag it manually. Of course, you can also drag any icon out of the Trash with the mouse, which gives you the option of putting it somewhere new (as opposed to back in the folder it started from).

If you’re confident that the items in the Trash window are worth deleting, use any of these three options:

Choose Finder→Empty Trash.

Press Shift-⌘-Delete. Or, if you’d just as soon not bother with the “Are you sure?” message, then throw the Option key in there, too.

Control-click the wastebasket icon (or right-click it, or just click it and hold the mouse button down for a moment); choose Empty Trash from the shortcut menu.

Tip

This last method has two advantages. First, the Mac doesn’t bother asking “Are you sure?” (If you’re clicking right on the Trash and choosing Empty Trash from the pop-up menu, it’s pretty darned obvious you are sure.) Second, this method nukes any locked files without making you unlock them first.

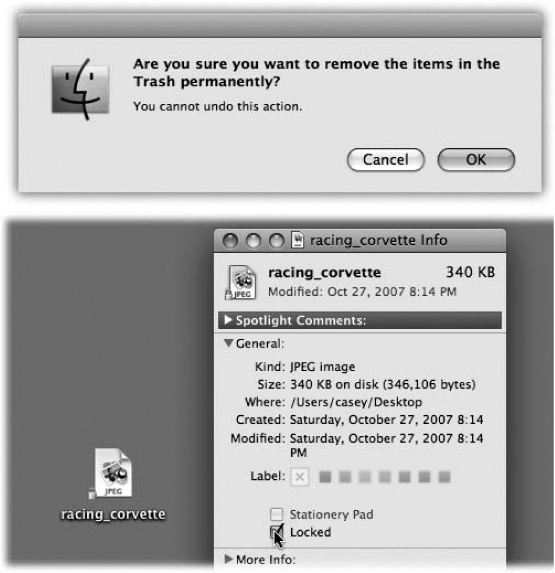

If you use either of the first two methods, the Macintosh asks you to confirm your decision. Click OK. (Figure 2-11 shows both this message and the secret for turning it off forever.)

Either way, Mac OS X now deletes those files from your hard drive.

When you empty the Trash as described above, each trashed icon sure looks like it disappears. The truth is, though, the data in each file is still on the hard drive. Yes, the space occupied by the dearly departed is now marked with an internal “This space available” message, and in time, new files may overwrite that spot. But in the meantime, some future eBay buyer of your Mac—or, more imminently, a savvy family member or office mate—could use a program like Norton Utilities to resurrect those deleted files. (In more dire cases, companies like DriveSavers.com can use sophisticated clean-room techniques to recover crucial information—for several hundred dollars, of course.)

That notion doesn’t sit well with certain groups, like government agencies, international spies, and the paranoid. As far as they’re concerned, deleting a file should really, really delete it, irrevocably, irretrievably, and forever.

Figure 2-11. Top: Your last warning. Mac OS X doesn’t tell you how many items are in the Trash or how much disk space they take up. If you’d rather not be interrupted for confirmation every time you empty the Trash, you can suppress this message permanently. To do that, choose Finder→Preferences, click Advanced, and then turn off “Show warning before emptying the Trash.” Bottom: The Get Info window for a locked file. Locking a file in this way isn’t military-level security by any stretch—any passing evildoer can unlock the file in the same way. But it does trigger an “operation cannot be completed” warning when you try to put it into the Trash—or indeed when you try to drag it into any other folder—providing at least one layer of protection against losing or deleting it.

Mac OS X’s Secure Empty Trash command to the rescue! When you choose this command from the Finder menu, the Mac doesn’t just obliterate the parking spaces around the dead file. It actually records new information over the old—random 0’s and 1’s. Pure static gibberish.

The process takes longer than the normal Empty Trash command, of course. But when it absolutely, positively has to be gone from this earth for good (and you’re absolutely, positively sure you’ll never need that file again), Secure Empty Trash is secure indeed.

By highlighting a file or folder, choosing File→Get Info, and turning on the Locked checkbox, you protect that file or folder from accidental deletion (see Figure 2-11 at bottom). A little padlock icon appears on the corner of the full-size icon, also shown in Figure 2-11.

Locked files in Snow Leopard behave quite differently than they used to:

Dragging the file into another folder makes a copy; the original stays put.

Putting the icon into the Trash produces a warning message: “Item ‘Shopping List’ is locked. Do you want to move it to the Trash anyway?” If so, click Continue.

Once a locked file is in the Trash, you don’t get any more warnings. When you empty the Trash, that item gets erased right along with everything else.

You can unlock files easily enough. Press Option-⌘-I (or press Option as you choose File→Show Inspector). Turn off the Locked checkbox in the resulting Info window. (Yes, you can lock or unlock a mass of files at once.)

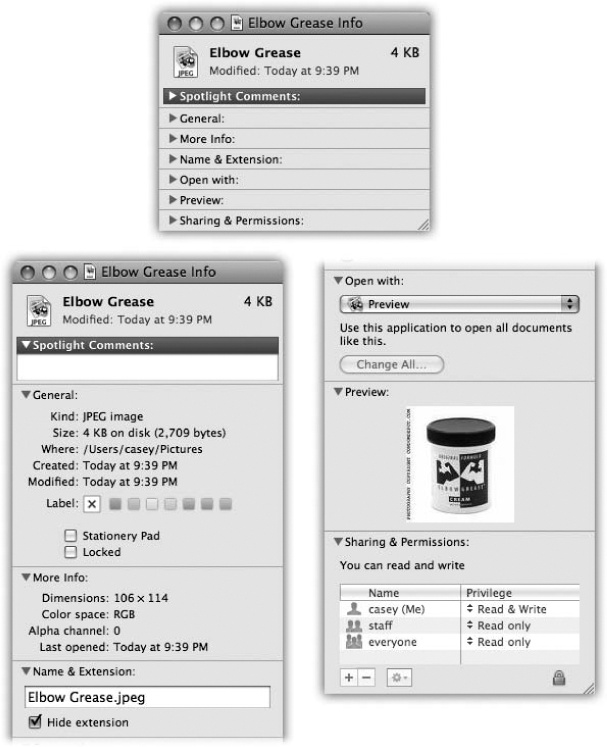

By clicking an icon and then choosing File→Get Info, you open an important window like the one shown in Figure 2-12. It’s a collapsible, multipanel screen that provides a wealth of information about a highlighted icon. For example:

For a document icon, you see when it was created and modified, and what programs it “belongs” to.

For an alias, you learn the location of the actual icon it refers to.

For a program, you see whether or not it’s been updated to run on Intel-based Macs. If so, the Get Info window says “Kind: Universal.” If not, it says “Kind: PowerPC” and will probably run slower than you’d like because it must be translated by Rosetta (Universal Apps (Intel Macs) and Rosetta).

For a disk icon, you get statistics about its capacity and how much of it is full.

If you open the Get Info window when nothing is selected, you get information about the desktop itself (or the open window), including the amount of disk space consumed by everything sitting on or in it.

If you highlight 11 icons or more simultaneously, the Get Info window shows you how many you highlighted, breaks it down by type (“23 documents, 3 folders,” for example), and adds up the total of their file sizes. That’s a great opportunity to change certain file characteristics on numerous files simultaneously, such as locking or unlocking them, hiding or showing their filename extensions (How Documents Know Their Parents), changing their ownership or permissions (The Get Info method), and so on.

If you highlight fewer than 11 icons, Mac OS X opens up individual Get Info windows for each one.

Figure 2-12. Top: The Get Info window can be as small as this, with all its information panes collapsed. Bottom: Or, if you click each flippy triangle to open its corresponding panel of information, it can be as huge as this—shown here split in two because the book isn’t tall enough to show the whole thing. The resulting dialog box can easily grow taller than your screen, which is a good argument for either (a) closing the panels you don’t need at any given moment or (b) running out to buy a really gigantic monitor. And as long as you’re taking the trouble to read this caption, here’s a tasty bonus: There’s a secret command in Snow Leopard called Get Summary Info. Highlight a group of icons, press Control-⌘-I, and marvel at the special Get Info box that tallies up their sizes and other characteristics.

In Mac OS X versions 10.0 and 10.1, a single Get Info window remained on the screen all the time as you clicked one icon after another. (Furthermore, the command was called Show Info instead of Get Info. Evidently “Show Info” sounded too much like it was the playbill for a Broadway musical.)

The single info window—officially called the Inspector—was great for reducing clutter, but it didn’t let you compare the statistics for the Get Info windows of two or three folders side by side.

So beginning in 10.2, Apple returned to the old way of doing Get Info: A new dialog box appears each time you get info on an icon (unless you’ve highlighted 11 or more icons, as already described).

But the uni-window approach is still available for those occasions when you don’t need side-by-side Get Info windows—if you know the secret. Highlight the icon and then press Option-⌘-I (or hold down Option and choose File→Show Inspector). The Get Info Inspector window that appears looks slightly different (it has a smaller title bar and a dimmed Minimize button), and it changes to reflect whatever icons you now click.

Apple built the Get Info window out of a series of collapsed “flippy triangles,” as shown in Figure 2-12. Click a triangle to expand a corresponding information panel.

Tip

The title-bar hierarchical menu described on Title Bar works in the Get Info dialog box, too. That is, ⌘-click the Get Info window’s title bar to reveal where this icon is in your folder hierarchy.

Depending on whether you clicked a document, program, disk, alias, or whatever, the various panels may include the following:

Spotlight Comments. Here, you can type in comments for your own reference. Later, you can view these remarks in any list view if you display the Comments column (Your Choice of Columns)—and you can find them when you conduct Spotlight searches (Chapter 3).

General. Here’s where you can view the name of the icon, and also see its size, creation date, most recent change date, locked status, and so on.

If you click a disk, this info window shows you its capacity and how full it is. If you click the Trash, you see how much stuff is in it. If you click an alias, this panel shows you a Select New Original button and reveals where the original file is. The General panel always opens the first time you summon the Get Info window.

More Info. Just as the name implies, here you’ll find more info, most often the dimensions and color format (graphics only) and when the icon was last opened. These morsels are also easily Spotlight-searchable.

Name & Extension. On this panel, you can read and edit the name of the icon in question. The “Hide extension” checkbox refers to the suffix on Mac OS X file names (the last three letters of Letter to Congress.doc, for example).

Many Mac OS X documents, behind the scenes, have filename extensions of this kind—but Mac OS X comes factory-set to hide them. By turning off this check-box, you can make the suffix reappear for an individual file. (Conversely, if you’ve elected to have Mac OS X show all file name suffixes, then this checkbox lets you hide the extensions on individual icons.)

Open with. This section is available for documents only. Use the controls on this screen to specify which program will open when you double-click this document, or any document of its type.

Preview. When you’re examining pictures, text files, PDF files, Microsoft Office files, sounds, clippings, and movies, you see a magnified thumbnail version of what’s actually in that document. This preview is like a tiny version of Quick Look (Quick Look). A controller lets you play sounds and movies, where appropriate.

Sharing & Permissions. This panel is available for all kinds of icons. If other people have access to your Mac (either from across the network or when logging in, in person), this panel lets you specify who is allowed to open or change this particular icon. See Chapter 12 for a complete discussion of this hairy topic.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: In Mac OS X 10.5, you sometimes saw other panels in the Get Info window. For example, iPhoto and iDVD each offered a Plug-ins panel that let you manage add-on software modules. In Snow Leopard, however, those panels are no longer available. Apple Tech Support probably received one too many call about a “broken” iPhoto that resulted from the customer’s fiddling with the Plug-ins panel.