Networks are awesome. Once you’ve got a network, you can copy files from one machine to another—even between Windows PCs and Macs—just as you’d drag files between folders on your own Mac. You can send little messages to other people’s screens. Everyone on the network can consult the same database or calendar, or listen to the same iTunes music collection. You can play games over the network. You can share a single printer or cable modem among all the Macs in the office. You can connect to the network from wherever you are in the world, using the Internet as the world’s longest extension cord back to your office.

In Snow Leopard, you can even do screen sharing, which means that you, the wise computer whiz, can see what’s on the screen of your pathetic, floundering relative or buddy elsewhere on the network. You can seize control of the other Mac’s mouse and keyboard. You can troubleshoot, fiddle with settings, and so on. It’s the next best thing to being there—often, a lot better than being there.

This chapter concerns itself with local networking—setting up a network in your home or small office. But don’t miss its sibling, Chapter 18, which is about hooking up to the somewhat larger network called the Internet.

Most people connect their computers using one of two connection systems: Ethernet or WiFi (which Apple calls AirPort).

Every Mac (except the MacBook Air) and every network-ready laser printer has an Ethernet jack (Figure 13-1). If you connect all the Macs and Ethernet printers in your small office to a central Ethernet hub or router—a compact, inexpensive box with jacks for five, 10, or even more computers and printers—you’ve got yourself a very fast, very reliable network. (Most people wind up hiding the hub in a closet and running the wiring either along the edges of the room or inside the walls.) You can buy Ethernet cables, plus the hub, at any computer store or, less expensively, from an Internet-based mail-order house; none of this stuff is Mac-specific.

Tip

If you want to connect only two Macs—say, your laptop and your desktop machine—you don’t need an Ethernet hub. Instead, you just need a standard Ethernet cable. Run it directly between the Ethernet jacks of the two computers. (You don’t need a special crossover Ethernet cable, as you did with Macs of old.) Then connect the Macs as described in the box on Networking Without the Network.

Or don’t use Ethernet at all; just use a FireWire cable or a person-to-person AirPort network.

Figure 13-1. Every Mac except the Air has a built-in Ethernet jack (left). It looks like an overweight telephone jack. It connects to an Ethernet router or hub (right) via an Ethernet cable (also known as Cat 5 or Cat 6), which ends in what looks like an overweight telephone-wire plug (also known as an RJ-45 connector).

Ethernet is the best networking system for many offices. It’s fast, easy, and cheap.

WiFi, known to the geeks as 802.11 and to Apple fans as AirPort, means wireless networking. It’s the technology that lets laptops the world over get online at high speed in any WiFi “hot spot.” Hot spots are everywhere these days: in homes, offices, coffee shops (notably Starbucks), hotels, airports, and thousands of other places.

Tip

At www.jiwire.com, you can type in an address or a city and learn exactly where to find the closest WiFi hot spots.

When you’re in a WiFi hot spot, your Mac has a very fast connection to the Internet, as though it’s connected to a cable modem or DSL.

AirPort circuitry comes preinstalled in every Mac laptop, iMac, and Mac Mini, and you can order it built into a Mac Pro.

This circuitry lets your machine connect to your network and the Internet without any wires at all. You just have to be within about 150 feet of a base station or access point (as Windows people call it), which must in turn be physically connected to your network and Internet connection.

If you think about it, the AirPort system is a lot like a cordless phone, where the base station is, well, the base station, and the Mac is the handset.

The base station can take any of these forms:

AirPort base station. Apple’s sleek, white, squarish or rounded base stations ($100 to $180) permit as many as 50 computers to connect simultaneously.

The less expensive one, the AirPort Express, is so small it looks like a small white power adapter. It also has a USB jack so you can share a USB printer on the network. It can serve up to 10 computers at once.

A Time Capsule. This Apple gizmo is exactly the same as the AirPort base station except that it also contains a huge hard drive so that it can back up your Macs automatically over the wired or wireless network.

A wireless broadband router. Lots of other companies make less expensive WiFi base stations, including Linksys (www.linksys.com) and Belkin (www.belkin.com). You can plug the base station into an Ethernet router or hub, thus permitting 10 or 20 wireless-equipped computers, including Macs, to join an existing Ethernet network without wiring. (With all due non-fanboyism, however, Apple’s base stations and software are infinitely more polished and satisfying to use.)

Another Mac. Your Mac can also impersonate an AirPort base station. In effect, the Mac becomes a software-based base station, and you save yourself the cost of a separate physical base station.

A few, proud people still get online by dialing via modem, which is built into some old AirPort base station models. The base station is plugged into a phone jack. Wireless Macs in the house can get online by triggering the base station to dial by remote control.

Tip

If you connect through a modern router or AirPort base station, you already have a great firewall protecting you. You don’t have to turn on Mac OS X’s firewall. But remember to turn it on when you escape to the local WiFi coffee shop with your laptop.

For the easiest AirPort network setup, begin by configuring your Mac so that it can go online the wired way, as described in the previous pages. Once it’s capable of connecting to the Internet via wires, you can then use the AirPort Utility (in your Applications→Utilities folder) to transmit those Internet settings wirelessly to the base station itself. From then on, the base station’s modem or Ethernet jack—not your Mac’s—will do the connecting to the Internet.

Whether you’ve set up your own wireless network or want to hop onto somebody else’s, Chapter 18 has the full scoop on joining WiFi networks.

You’re forgiven for splurting your coffee. Everyone knows that FireWire is great for hooking up a camcorder or a hard drive, and a few people know about FireWire Disk Mode. But not many people realize that FireWire makes a fantastic networking cable, since it’s insanely, blisteringly fast. (All right, gigabit Ethernet is faster, and so is FireWire 800. But attaining that kind of networking nirvana requires that all your Macs, hubs, and other networking gear are all compatible with gigabit Ethernet or FireWire 800.)

FireWire networking, technically known as IP over FireWire, is an unheralded, unsung feature of Mac OS X. But when you have a lot of data to move between Macs—your desktop and your laptop, for example—a casual FireWire network is the way to go. It lets you copy a gigabyte of email, pictures, or video files in a matter of seconds.

Here’s how you unleash this secret feature:

Connect two Macs with a FireWire cable.

You can’t use the one that fits a camcorder. You need a six-pin-to-six-pin cable for traditional FireWire jacks. If you want to use the faster FireWire 800 connection on some of the latest Mac models, you’ll need to shop for an even less common cord.

Both computers can remain turned on; you can even continue to use both Macs while they’re connected.

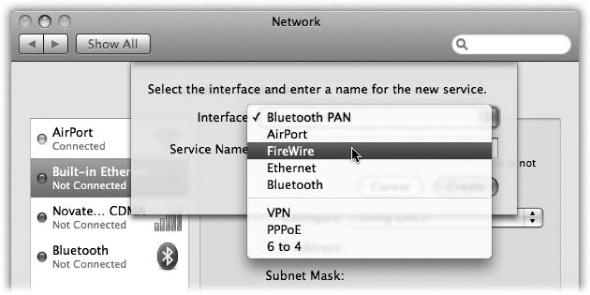

Open System Preferences→Network. Click the

icon and enter your Administrator password. Click the

icon and enter your Administrator password. Click the  button below the list of network connections.

button below the list of network connections.Figure 13-2. In the Network pane of System Preferences, you can add your FireWire port to the list of network connections. The point of this window, by the way, is that a Mac can maintain simultaneous open network connections—Ethernet, AirPort, FireWire, and dial-up modem. (That’s a feature called multihoming.)

The tiny dialog box shown in Figure 13-2 appears, letting you specify what kind of network connection you want to set up.

From the pop-up menu, choose FireWire. Click Create.

Now your newly created FireWire connection appears in the list.

Repeat steps 2 through 3 on the second Mac.

By now, it may have dawned on you that you can’t actually get online via FireWire, since your cable runs directly between two Macs. But you can always turn on Internet Sharing (Making the Switch) on the other Mac.

Quit System Preferences.

Your Macs are ready to talk—fast. Read the following pages for details on sharing files between them.

When you’re done wiring (or not wiring, as the case may be), your network is ready. Your Mac should “see” any Ethernet or shared USB printers, in readiness to print (Chapter 14). You can now play network games or use a network calendar. And you can now turn on File Sharing, one of the most useful features of all.

In File Sharing, you can summon the icon for a folder or disk attached to another computer on the network, whether it’s a Mac or a Windows PC. It shows up in a Finder window, as shown in Figure 13-3.

At this point, you can drag files back and forth, exactly as though the other computer’s folder or disk is a hard drive connected to your own machine.

The thing is, it’s not easy being Apple. You have to write one operating system that’s supposed to please everyone, from the self-employed first-time computer owner to the network administrator for NASA. You have to design a networking system simple enough for the laptop owner who just wants to copy things to a desktop Mac when returning from a trip, yet secure and flexible enough for the network designer at a large corporation.

Clearly, different people have different attitudes toward the need for security and flexibility.

That’s why Snow Leopard offers two ways to share files—a simple and limited way, and a more complicated and flexible way:

The simple way: the Public folder. Every account holder has a Public folder. It’s free for anyone else on the network to access. Like a grocery store bulletin board, there’s no password required. Super-convenient, super-easy.

There’s only one downside, and you may not care about it: You have to move or copy files into the Public folder before anyone else can see them. Depending on how many files you want to share, this can get tedious, disrupt your standard organizational structure, and eat up disk space.

The flexible way: Any folder. You can also make any file, folder, or disk available for inspection by other people on the network. This method means that you don’t have to move files into the Public folder, for starters. It also gives you elaborate control over who is allowed to do what to your files. You might want to permit your company’s executives to see and edit your documents, but allow the peons in Accounting just to see them. And Andy, that unreliable goofball in Sales? You don’t want him even seeing what’s in your shared folder.

Of course, setting up all those levels of control means more work and more complexity.

Inside your Home folder, there’s a folder called Public. Inside everybody’s Home folder is a folder called Public.

Anything you copy into this folder is automatically available to everyone else on the network. They don’t need a password, they don’t need an account on your Mac—they just have to be on the same network.

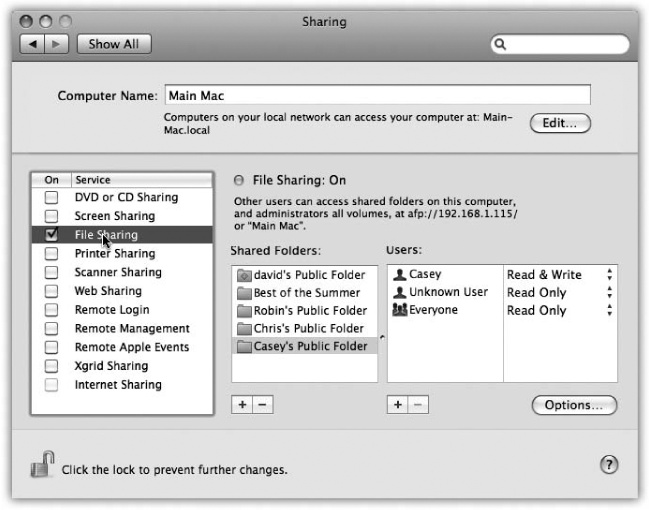

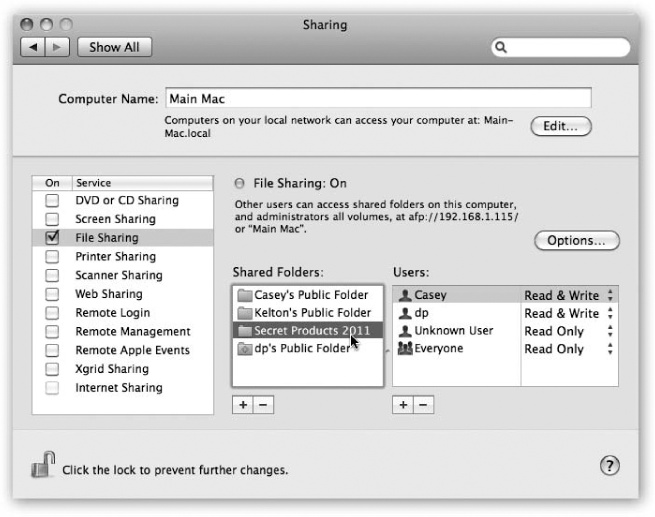

To make your Public folder available to your network mates, you have to turn on the File Sharing master switch. Choose  →System Preferences, click Sharing, and turn on File Sharing (Figure 13-3).

→System Preferences, click Sharing, and turn on File Sharing (Figure 13-3).

Now round up the files and folders you want to share with all comers on the network, and drag them into your Home→Public folder. That’s all there is to it.

Note

You may notice that there’s already something in your Public folder: a folder called Drop Box. It’s there so that other people can give you files from across the network, as described later in this chapter.

So now that you’ve set up Public folder sharing, how are other people supposed to access your Public folder? See Accessing Shared Files.

If the Public folder method seems too simple and restrictive, then you can graduate to the “share any folder” method. In this scheme, you can make any file, folder, or disk available to other people on the network.

This time, you don’t have to move your files anywhere; they sit right where you have them. And this time, you can set up elaborate sharing privileges (also known as permissions) that grant individuals different amounts of access to your files.

This method is more complicated to set up than that Public-folder business. In fact, just to underline its complexity, Apple has created two different setup procedures. You can share one icon at a time by opening its Get Info window; or you can work in a master list of shared items in System Preferences.

The following pages cover both methods.

Here’s how to share a Mac file, disk, or folder disk using its Get Info window.

The following steps assume that you’ve turned on  →System Preferences→Sharing→File Sharing, as shown in Figure 13-3.

→System Preferences→Sharing→File Sharing, as shown in Figure 13-3.

Highlight the folder or disk you want to share. Choose File→Get Info.

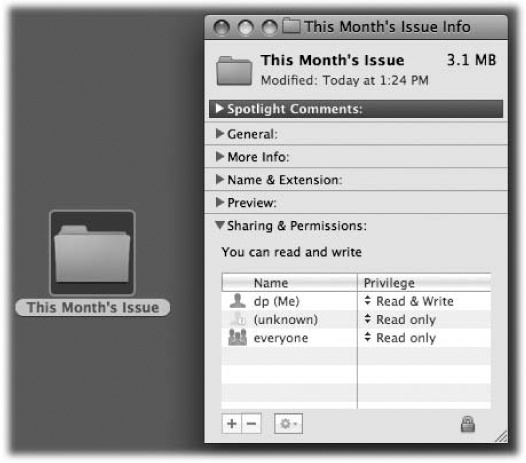

The Get Info dialog box appears (Figure 13-4). Expand the General panel, if it’s not already visible.

Note

Sharing an entire disk means that every folder and file on it is available to anyone you give access to. On the other hand, by sharing only a folder or two, you can keep most of the stuff on your hard drive private, out of view of curious network comrades. Sharing only a folder or two does them a favor, too, by making it easier for them to find the files they’re supposed to have. This way, they don’t have to root through your entire drive looking for the folder they actually need.

Enter your administrative password, if necessary.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: New in Mac OS X 10.6: To help you remember what you’ve made available to other people on the network, a gray banner labeled “Shared Folder” appears across the top of any Finder window that you’ve shared. It even appears at the top of the Open and Save dialog boxes.

OK, this disk or folder is now shared. But with whom?

Expand the Sharing & Permissions panel, if it’s not already visible. Click the

icon and enter your administrator’s password.

icon and enter your administrator’s password.The controls in the Sharing & Permissions area spring to life and become editable. At the bottom of the Info panel is a little table. The first column can display the names of individual account holders, like Casey or Chris, or groups of account holders, like Everyone or Accounting Dept.

The second column lists the privileges each person or group has for this folder.

Now, the average person has no clue what “privileges” means, and this is why things get a little hairy when you’re setting up folder-by-folder permissions. But read on; it’s not as bad as it seems.

Edit the table by adding people’s names. Then set their access permissions.

At the moment, your name appears in the Name column, and it probably says Read & Write in the Privilege column. In other words, you’re currently the master of this folder. You can put things in, and you can take things out.

Figure 13-4. The file-sharing permissions controls are here, in the Get Info box for any file, folder, or disk.

In other words, if you just want to share files with yourself, so you can transfer them from one computer to another, you can stop here.

If you want to share files with other people, well, note that at the moment, the privileges for “Everyone” is probably set to “Read only.” Other people can see this folder, but they can’t do anything with it.

Your job is to work through this list of people, specifying how much control each person has over the file or folder you’re sharing.

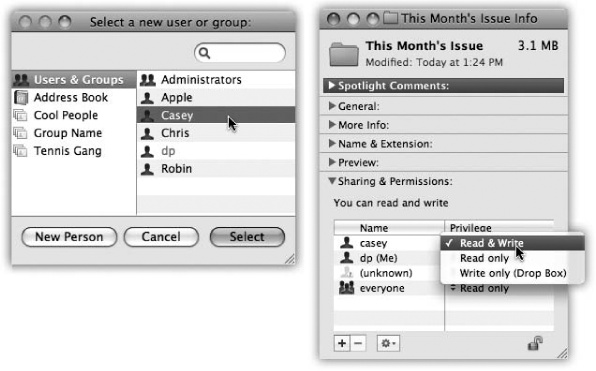

To add the name of a person or group, click the

button below the list. The people list shown in Figure 13-5 appears.

button below the list. The people list shown in Figure 13-5 appears.Figure 13-5. This list includes every account holder on your Mac, plus groups you’ve set up, plus the contents of your Address Book. One by one, you can add them to the list of lucky sharers of your files or folders—and then change the degree of access they have to the stuff you’re sharing.

Now click a name in the list. Then, from the Privilege pop-up menu, choose a permissions setting.

Read & Write has the most access of all. This person, like you, can add, change, or delete any file in the shared folder, or make any changes they like to a document. Give Read & Write permission to people you trust not to mess things up.

Read only means “Look, but don’t touch.” This person can see what’s in the folder (or file) and can copy it, but they can’t delete or change the original. It’s a good setting for distributing company documents or making source files available to your minions.

Write only (drop box) means that other people can’t open the folder at all. They can drop things into it, but it’s like dropping icons through a mail slot: The letter disappears into the slot, and then it’s too late for them to change their minds. As the folder’s owner, you can do what you like with the deposited goodies. This drop-box effect is great when you want students, coworkers, or family members to be able to turn things in to you—homework, reports, scandalous diaries—without running the risk that someone else might see those documents. (This option doesn’t appear for documents—only disks and folders.)

No access is an option only for “Everyone.” It means that other people can see this file or folder’s icon but can’t do a thing with it.

Close the Get Info window.

Now the folder is ready for invasion from across the network.

It’s very convenient to turn on sharing one folder at a time, using the Get Info window. But there’s another way in, too, one that displays all your shared stuff in one handy master list.

To see it, choose  →System Preferences. Click Sharing. Click File Sharing (and make sure it’s turned on).

→System Preferences. Click Sharing. Click File Sharing (and make sure it’s turned on).

Figure 13-6. Hiding in System Preferences is a list of every file, disk, and folder you’ve shared. To stop sharing something, click it and click the  button. To share something new, drag its icon off the desktop, or out of its window, directly into the Shared Folders list.

button. To share something new, drag its icon off the desktop, or out of its window, directly into the Shared Folders list.

Now you’re looking at a slightly different kind of permissions table, shown in Figure 13-6. It has three columns:

Shared folders. The first column lists the files, folders, and disks you’ve shared. You’ll probably see that every account’s Public folder is already listed here, since they’re all shared automatically. (You can turn off sharing for a Public folder, too, just by clicking it and then clicking the

button.)

button.)But you can add more icons to this list. Either drag them into the list directly from the desktop or a Finder window, or click the

sign, navigate to the item you want to share, select it, and then click Add. Either way, that item now appears in the Shared Folders list.

sign, navigate to the item you want to share, select it, and then click Add. Either way, that item now appears in the Shared Folders list.Users. When you click a shared item, the second column sprouts a list of who gets to work with it from across the network. You’re probably listed here, of course, since it’s your stuff. But somebody called Unknown User also appears in this list (a reference to people who sign in as Guests, as described on Group). There’s also a listing here for Everyone, which really means, “everyone else”—that is, everyone who’s not specifically listed here.

You can add to this list, too. Click

to open the person-selection box shown in Figure 13-5. It lists the other account holders on your Mac, some predefined groups, and the contents of your Address Book.

to open the person-selection box shown in Figure 13-5. It lists the other account holders on your Mac, some predefined groups, and the contents of your Address Book.Note

Most of the Address Book people don’t actually have accounts on this Mac, of course. If you choose somebody from this list, you’re asked to make up an account password. When you click Create Account, you have actually created a Sharing Only account on your Mac for that person, as described on Managed accounts with Parental Controls. When you return to the Accounts pane of System Preferences, you’ll see that new person listed.

Double-click a person’s name to add her to the list of people who can access this item from over the network, and then set up the appropriate privileges (described next).

To remove someone from this list, of course, just click the name and then click the

button.

button.Users. This third column lets you specify how much access each person in the second column has to this folder. Your choices, once again, are Read & Write (full access to change or delete this item’s contents); Read Only (open or copy, but can’t edit or delete); and Write Only (Drop Box), which lets the person put things into this disk or folder, but not open it or see what else is in it.

For the Everyone group, you also get an option called No Access, which means that this item is completely off-limits to everyone else on the network.

And now, having slogged through all these options and permutations, your Mac is ready for invasion from across the network.

So far in this chapter, you’ve read about setting up a Mac so people at other computers can access its files.

Now comes the payoff: sitting at another computer and connecting to the one you set up. There are two ways to go about it: You can use the Sidebar, or you can use the older, more flexible Connect to Server command. The following pages cover both methods.

Suppose, then, that you’re seated in front of your Mac, and you want to see the files on another Mac on the network. Proceed like this:

Open any Finder window.

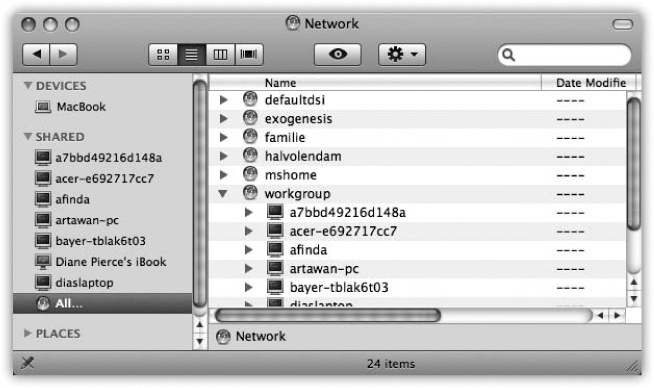

In the Shared category of the Sidebar at the left side of the window, icons for all the computers on the network appear. See Figure 13-7.

Tip

The same Sidebar items show up in the Save and Open dialog boxes of your programs, too, making the entire network available to you for opening and saving files.

Figure 13-7. Macs appear in the Sidebar with whatever names they’ve been given in System Preferences→Sharing. Their tiny icons usually resemble the computers themselves. Other computers (like Windows PCs) have generic blue monitors.

If you don’t see a certain Mac’s icon here, it might be turned off, it might not be on the network, or it might have File Sharing turned off. (And if you don’t see any computers at all in the Sidebar, then your computer might not be on the network. Or maybe you’ve turned off the checkboxes for “Connected Servers” and “Bonjour Computers” in Finder→Preferences→Sidebar.)

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: If the other Mac is just asleep, though, it still shows up in the Sidebar, and you can wake it up to get at it. How is that possible? Through the miracle of the new Wake for Network Access feature described on Checkbox Options.

If there are a lot of computer icons in the Sidebar, or if you’re on a corporate-style network that has sub-chunks like nodes or workgroups, you may also see an icon called All. Click it to see the full list of network entities that your Mac can see: not just individual Mac, Windows, and Unix machines, but also any “network neighborhoods” (limbs of your network tree). For example, you may see the names of network zones (clusters of machines, as found in big companies and universities).

Or, if you’re trying to tap into a Windows machine, open the icon representing the workgroup (computer cluster) that contains the machine you want. In small office networks, it’s usually called MSHOME or WORKGROUP. In big corporations, these workgroups can be called almost anything—as long as it’s no more than 12 letters long with no punctuation. (Thanks, Microsoft.)

If you do see icons for workgroups or other network “zones,” double-click until you’re seeing the icons for individual computers.

Note

If you’re a network nerd, you may be interested to note that Mac OS X can “see” servers that use the SMB/CIFS, NFS, FTP, and WebDAV protocols running on Mac OS X Server, AppleShare, Unix, Linux, Novell NetWare, Windows NT, Windows 2000, Windows XP, and Windows Vista servers. But the Sidebar reveals only the shared computers on your subnet (your local, internal office network). (It also shows Back to My Mac if it’s set up; see Screen sharing the manual way.)

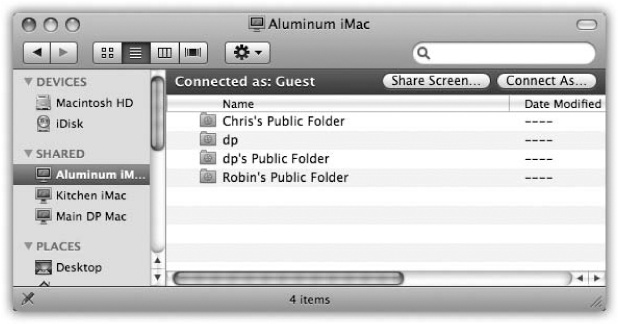

Click the computer whose files you want to open.

In the main window, you now see the icons for each account holder on that computer: Mom, Dad, Sissy, whatever. If you have an account on the other computer, you’ll see a folder representing your stuff, too (Figure 13-8).

At this point, the remaining instructions diverge, depending on whether you want to access other people’s stuff or your stuff. That’s why there are two alternative versions of step 3 here:

If you want to access the stuff that somebody else has left for you, double-click that person’s Public folder.

Instantly, the icon for that folder appears on your desktop, and an Eject button (

) appears beside the computer’s name in the Sidebar.

) appears beside the computer’s name in the Sidebar.In this situation, you’re only a Guest. You don’t have to bother with a password. On the other hand, the only thing you can generally see inside the other person’s account folder is his Public folder.

Tip

Actually, you might see other folders here—if the account holder has specifically shared them and decided that you’re important enough to have access to them, as described on Setup: Sharing Through Any Folder.

One thing you’ll find inside the Public folder is the Drop Box folder. This folder exists so that you can give files and folders to the other person. You can drop any of your own icons onto the Drop Box folder—but you can’t open the Drop Box folder to see what other people have put there. It’s one-way, like a mail slot in somebody’s front door.

If you see anything else at all in the Public folder you’ve opened, then it’s stuff the account holder has copied there for the enjoyment of you and your network mates. You’re not allowed to delete anything from the other person’s Public folder or make changes to anything in it.

You can, however, open those icons, read them, or even copy them to your Mac—and then edit your copies.

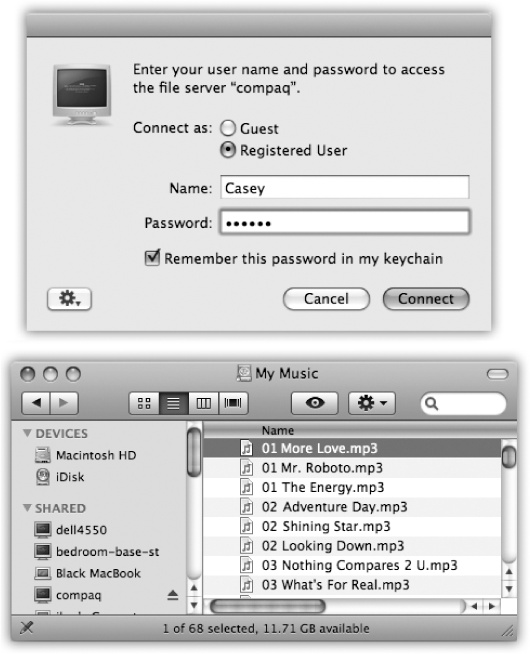

To access your own Home folder on the other Mac, click it, and then click the Connect As button (Figure 13-9). Sign in as usual.

When the “Connect to the file server” box appears, you’re supposed to specify your account name and password (from the Mac you’re tapping into). This is the same name and password you’d use to log in if you were actually sitting at that machine.

Type your short user name and password. (If you’re not sure what your short user name is, open System Preferences on your home-base Mac, click Accounts, and then click your account name.) And if you didn’t set up a password for your account, leave the password box empty.

Tip

The dialog box shown in Figure 13-9 includes the delightful and timesaving “Remember this password in my keychain” option, which makes the Mac memorize your password for a certain disk so you don’t have to type it—or even see this dialog box—every darned time you connect. (If you have no password, though, the “Remember password” doesn’t work, and you’ll have to confront—and press Return to dismiss—the “Connect to the file server” box every time.)

Figure 13-9. Top: You can sign in to your account on another Mac on the network (even while somebody else is actually using that Mac in person). Click Connect As (top right), and then enter your name and password. Turn on “Remember this password” to speed up the process for next time. The Action ( ) pop-up menu offers a Change Password command that gives you the opportunity to change your account password on the other machine, just in case you suspect someone saw what you typed. Bottom: No matter which method you use to connect to a shared folder or disk, its icon shows up in the Sidebar. It’s easy to disconnect, thanks to the little

) pop-up menu offers a Change Password command that gives you the opportunity to change your account password on the other machine, just in case you suspect someone saw what you typed. Bottom: No matter which method you use to connect to a shared folder or disk, its icon shows up in the Sidebar. It’s easy to disconnect, thanks to the little  button.

button.

When you click Connect (or press Return or Enter), your own Home folder on the other Mac appears. Its icon shows up on your desktop, and a little  button appears next to its name. Click it to disconnect.

button appears next to its name. Click it to disconnect.

Tip

Once you’ve connected to a Mac using your account, the other Mac has a lock on your identity. You’ll be able to connect to the other Mac over and over again during this same computing session, without ever having to retype your password.

In the meantime, you can double-click icons to open them, make copies of them, and otherwise manipulate them exactly as though they were icons on your own hard drive. Depending on what permissions you’ve been given, you can even edit or trash those files.

Tip

There’s one significant difference between working with “local” icons and working with those that sit elsewhere on the network. When you delete a file from another Mac on the network, either by pressing the Delete key or by dragging it to the Trash, a message appears to let you know that you’re about to delete that item instantly and permanently. It won’t simply land in the Trash “folder,” awaiting the Empty Trash command.

You can even use Spotlight to find files on that networked disk. If the Mac across the network is running Leopard or Snow Leopard, in fact, you can search for words inside its files, just as though you were sitting in front of it. If not, you can still search for text in files’ names.

The Sidebar method of connecting to networked folders and disks is practically effortless. It involves nothing more than clicking your way through folders—a skill that, in theory, you already know.

But the Sidebar method has its drawbacks. For example, the Sidebar doesn’t let you type in a disk’s network address. As a result, you can’t access any shared disk on the Internet (an FTP site, for example), or indeed anywhere beyond your local subnet (your own small network).

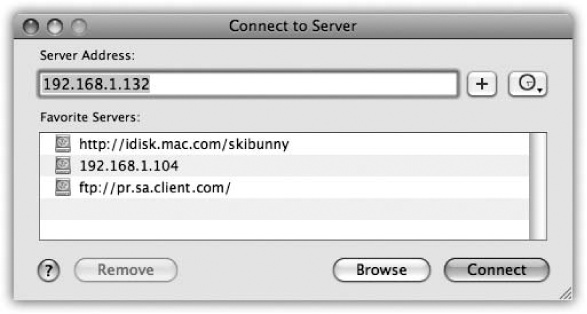

Fortunately, there’s another way. When you choose Go→Connect to Server, you get the dialog box shown in Figure 13-10. You’re supposed to type in the address of the shared disk you want.

Figure 13-10. The Sidebar method of connecting to shared disks and folders is quick and easy, but it doesn’t let you connect to certain kinds of disks. The Connect to Server method entails plodding through several dialog boxes and doesn’t let you browse for shared disks, but it can find just about every kind of networked disk.

For example, from here you can connect to:

Everyday Macs on your network. If you know the IP address of the Mac you’re trying to access (you geek!), you can type nothing but its IP address into the box and then hit Connect.

And if the other Mac runs Mac OS X 10.2 or later, you can just type its Bonjour (formerly Rendezvous) name: afp://upstairs-PowerMac.local.

Tip

To find out your Mac’s IP address, open the Network pane of System Preferences. There, near the top, you’ll see a message like this: “AirPort is connected to Tim’s Hotspot and has the IP address 192.168.1.113.” That’s your IP address.

To see your Bonjour address, open the Sharing pane of System Preferences. Click File Sharing. Near the top, you’ll see the computer name with “.local” tacked onto its name—and hyphens instead of spaces—like this: Little-MacBook.local.

After you enter your account password and choose the shared disk or folder you want, its icon appears on your desktop and in the Sidebar. You’re connected exactly as though you had clicked Connect As (Figure 13-9).

The next time you open the Connect to Server dialog box, Mac OS X remembers that address, as a courtesy to you, and shows it pre-entered in the Address field.

Macs across the Internet. If your Mac has a permanent (static) IP address, the computer itself can be a server, to which you can connect from anywhere in the world via the Internet. Details on this procedure begin on Connecting from the Road.

Windows machines. Find out the PC’s IP address or computer name, and then use this format for the address:smb://192.168.1.34 or smb://Cheapo-Dell.

After a moment, you’re asked to enter your Windows account name and password, and then to choose the name of the shared folder you want. When you click OK, the shared folder appears on your desktop as an icon, ready to use. (More on sharing with Windows PCs later in this chapter.)

NFS servers. If you’re on a network with Unix machines, you can tap into one of their shared directories using this address format: nfs://Machine-Name/pathname, where Machine-Name is the computer’s name or IP address, and pathname is the folder path (Title Bar) to the shared item you want.

FTP servers. Mac OS X makes it simple to bring FTP servers onto your screen, too. (These are the drives, out there on the Internet, that store the files used by Web sites.)

In the Connect to Server dialog box, type the FTP address of the server you want, like this: ftp://www.apple.com. If the site’s administrators have permitted anonymous access—the equivalent of a Guest account—that’s all there is to it. A Finder window pops open, revealing the FTP site’s contents.

If you need a password for the FTP site, however, what you type into the Connect to Server dialog box should incorporate the account name you’ve been given, like this: ftp://yourname@www.apple.com. You’ll be asked for your password.

Tip

You can even eliminate that password-dialog box step by using this address format: ftp://yourname:yourpassword@www.apple.com.

Once you type it and press Return, the FTP server appears as a disk icon on your desktop (and in the Sidebar). Its contents appear, too, ready to open or copy.

WebDAV server. This special Web-based shared disk requires a special address format, like this: http://Computer-Name/pathname (Technically, the iDisk is a WebDAV server—but there are far user-friendlier ways to get at it.)

In each case, once you click OK, you may be asked for your name and password.

And now, some timesaving features in the Connect to Server box:

Once you’ve typed a disk’s address, you can click

to add it to the list of server favorites. The next time you want to connect, you can just double-click its name.

to add it to the list of server favorites. The next time you want to connect, you can just double-click its name.The clock-icon pop-up menu lists Recent Servers—computers you’ve accessed recently over the network. If you choose one of them from this pop-up menu, you can skip having to type in an address.

Tip

Like the Sidebar network-browsing method, the Connect to Server command displays each connected computer as an icon in your Sidebar, even within the Open or Save dialog boxes of your programs. You don’t have to burrow through the Sidebar’s Network icon to open files from them, or save files onto them.

When you’re finished using a shared disk or folder, you can disconnect from it by clicking the  icon next to its name in the Sidebar.

icon next to its name in the Sidebar.

In Mac OS X, you really have to work if you want to know whether other people on the network are accessing your Mac. You have to choose System Preferences→Sharing→File Sharing→Options. There you’ll see something like, “Number of users connected: 1.”

Maybe that’s because there’s nothing to worry about. You certainly have nothing to fear from a security standpoint, since you control what they can see on your Mac. Nor will you experience much computer slowdown as you work, thanks to Mac OS X’s prodigious multitasking features.

Still, if you’re feeling particularly antisocial, you can slam shut the door to your Mac. Just open System Preferences→Sharing and turn off File Sharing.

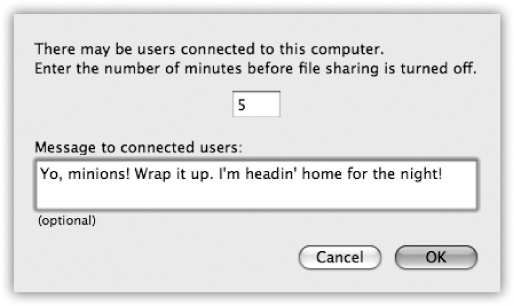

If anybody is, in fact, connected to your Mac at the time (from a Mac), you see the dialog box in Figure 13-11. If not, your Mac instantly becomes an island once again.

Microsoft Windows may dominate the corporate market, but there are Macs in the offices of America—and there are PCs in homes. Fortunately, Macs and Windows PCs can see each other on the network, with no special software (or talent) required.

In fact, you can go in either direction. Your Mac can see shared folders on the Windows PC, and a Windows PC can see shared folders on your Mac.

It goes like this.

Suppose you have a Windows PC and a Mac on the same wired or wireless network. Here’s how you get the Mac and PC chatting:

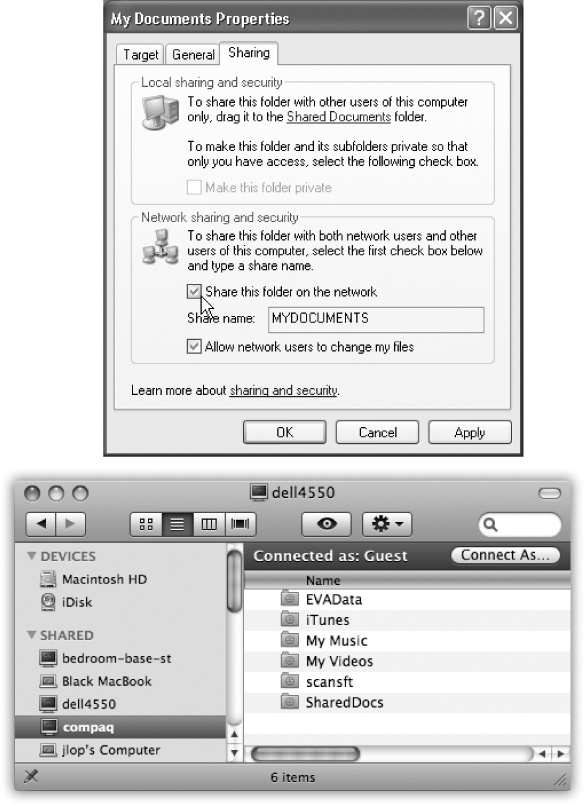

On your Windows PC, share some files.

This isn’t really a book about Windows networking (thank heaven), but here are the basics.

Just as on the Mac, there are two ways to share files in Windows. One of them is super-simple: You just copy the files you want to share into a central, fully accessible folder. No passwords, accounts, or other steps are required.

In Windows XP, that special folder is the Shared Documents folder, which you can find by choosing Start→My Computer. Share it on the network as shown in Figure 13-12, top.

In Windows Vista, it’s the Public folder, which appears in the Navigation pane of every Explorer window. (In Vista, there’s one Public folder for the whole computer, not one per account holder.)

In Windows 7, there’s a Public folder in each of your libraries. That is, there’s a Public Documents, Public Pictures, Public Music, and so on.

Figure 13-12. Top: To share a folder in Windows, right-click it, choose Properties, and then turn on “Share this folder on the network.” In the “Share name” box, type a name for the folder as it will appear on the network. (No spaces are allowed). Bottom: Back in the safety of Mac OS X, click the PC’s name in the Sidebar. (If it’s part of a workgroup, click All, and then your workgroup name first. And if you still don’t see the PC’s name, see the box on the next page.) Next, click the name of the shared computer. If the files you need are in a Shared Documents or Public folder, no password is required. You see the contents of the PC’s Shared Documents folder or Public folder, as shown here. Now it’s just like file sharing with another Mac. If you want access to any other shared folder, click Connect As, and see Figure 13-13.

The second, more complicated method is the “share any folder” method, just as in Leopard. In XP or Vista, you right-click the folder you want to share, choose Properties from the shortcut menu, click the Sharing tab, and turn on “Share this folder on the network” (Figure 13-12, top). In Windows 7, use the Share With menu at the top of any folder’s window. See the box on Windows 7 Hell for more details.

Repeat for any other folders you want to make available to your Mac.

On the Mac, open any Finder window.

The shared PCs may appear as individual computer names in the Sidebar, or you may have to click the All icon to see the icons of their workgroups (network clusters—an effect shown on Accessing Shared Files). Unless you or a network administrator changed it, the workgroup name is probably MSHOME or WORKGROUP. Double-click the workgroup name you want.

Tip

You can also access the shared PC via the Connect to Server command, as described on Connection Method B: Connect to Server. You could type into it smb://192.168.1.103 (or whatever the PC’s IP address is) or smb://SuperDell (or whatever its name is) and hit Return—and then skip to step 5. In fact, using the Connect to Server method often works when the Sidebar method doesn’t.

Now the names of the individual PCs on the network appear in your Finder window. (If you’re running Windows 7, see the box on When Windows 7 Can’t See the Mac.)

Double-click the name of the computer you want.

If you’re using one of the simple file-sharing methods on the PC, as described above, that’s all there is to it. The contents of the Shared Documents or Public folder now appear on your Mac screen. You can work with them just as you would your own files.

If you’re not using one of those simple methods, and you want access to individual shared folders, read on.

Click Connect As.

This button appears in the top-right corner of the Finder window; you can see it at bottom in Figure 13-12.

Now you’ re asked for your name and password (Figure 13-13, top).

Figure 13-13. Top: The PC wants to make sure you’re authorized to visit it. If the terminology here seems a bit geeky by Apple standards, no wonder—this is Microsoft Windows’ lingo you’re seeing, not Apple’s. Fortunately, you see this box only the very first time you access a certain Windows folder or disk; after that, you see only the box shown below. Bottom: Here, you see a list of shared folders on the PC. Choose the one you want to connect to, and then click OK. Like magic, the Windows folder shows up on your Mac screen, ready to use!

Enter the name and password for your account on the PC, and then click OK.

At long last, the contents of the shared folder on the Windows machine appear in your Finder window, just as though you’d tapped into another Mac (Figure 13-13, bottom). The icon of the shared folder appears on your desktop, too, and an Eject button (

) appears next to the PC’s name in your Sidebar.

) appears next to the PC’s name in your Sidebar.From here, it’s a simple matter to drag files between the machines, open Word documents on the PC using Word for the Mac, and so on—exactly like you’re hooked into another Mac.

Cross-platformers, rejoice: Mac OS X lets you share files in both directions. Not only can your Mac see other PCs on the network, but they can see the Mac, too.

On the Mac, open  →System Preferences→Sharing. Click File Sharing (make sure File Sharing is turned on), and then click Options to open the dialog box shown in Figure 13-14.

→System Preferences→Sharing. Click File Sharing (make sure File Sharing is turned on), and then click Options to open the dialog box shown in Figure 13-14.

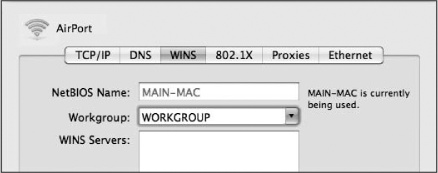

Turn on “Share files and folders using SMB (Windows).” Below that checkbox, you see a list of all the accounts on your Mac. Turn on the checkboxes to specify which Mac user accounts you want to be able to access. You must type in each person’s password, too. Click Done.

Figure 13-14. Prepare your Mac for visitation by the Windows PC. It won’t hurt a bit. The system-wide On switch for invasion from Windows is the third checkbox here, in the System Preferences→Sharing→File Sharing→Options box. Next, turn on the individual accounts whose icons you’ll want to show up on the PC. Enter their account passwords, too. Click Done when you’re done.

Before you close System Preferences, study the line near the middle of the window, where it says something like: “Other users can access your computer at afp://192.168.1.108 or MacBook-Pro.” You’ll need one of these addresses shortly.

Now, on Windows XP, open My Network Places; in Windows Vista, choose Start→Network; in Windows 7, expand the Network heading in the sidebar of any desktop window. If you’ve sacrificed the proper animals to the networking gods, your Mac’s icon should appear by itself in the network window, as shown in Figure 13-15, top.

Double-click the Mac’s icon. Public-folder stuff is available immediately. Otherwise, you have to sign in with your Mac account name and password; Figure 13-15, middle, has the details.

Figure 13-15. Top: Double-click the icon of the Mac you want to visit from your Windows machine (Vista is shown here). Middle: Type your Mac’s name in all capitals (or its IP address), then a backslash, and then your Mac account short name. (You can find out your Mac’s name on the Sharing pane of System Preferences.) Enter your Mac account’s password, too. Turn on “Remember my password” if you plan to do this again someday. Click OK. Bottom: Here’s your Mac Home folder—in Windows! Open it up to find all your stuff.

In the final window, you see your actual Home folder—on a Windows PC! You’re ready to open its files, copy them back and forth, or whatever (Figure 13-15, bottom).

If your Mac’s icon doesn’t appear, and you’ve read the box on When the Mac Doesn’t See the PC, wait a minute or two. Try restarting the PC. In Windows XP, try clicking “Microsoft Windows Network” or “View workgroup computers” in the task pane.

If your Mac still doesn’t show up, you’ll have to add it the hard way. In the address bar of any Windows window, type \\macbook-pro\chris (but substitute your Mac’s actual computer name and your short account name), taking care to use backslashes, not normal / slashes. You can also type your Mac’s IP address in place of its computer name.

In the future, you won’t have to do so much burrowing; your Mac’s icon should appear automatically in the My Network Places or Network window.

The direct Mac-to-Windows file-sharing feature of Mac OS X is by far the easiest way to access each other’s files. But it’s not the only way. Via Flash Drive offers a long list of other options, from flash drives to the iDisk.

The prayers of baffled beginners and exasperated experts everywhere have now been answered. Now, when the novice needs help from the guru, the guru doesn’t have to run all the way downstairs or down the hall to assist. Thanks to Snow Leopard’s screen-sharing feature, you can see exactly what’s on the screen of another Mac, from across the network—and even seize control of the other Mac’s mouse and keyboard (with the newbie’s permission, of course).

(Anyone who’s ever tried to help someone troubleshoot over the phone knows exactly what this means. If you haven’t, this small example may suffice: “OK, open the Apple menu and choose ‘About This Mac.’” Pause. “What’s the Apple menu?”)

Nor is playing Bail-Out-the-Newbie the only situation when screen sharing is useful. It’s also great for collaborating on a document, showing something to someone for approval, or just freaking each other out. It can also be handy when you are the owner of both Macs (a laptop and a desktop, for example), and you want to run a program that you don’t have on the Mac that’s in front of you. For example, you might want to adjust the playlist selection on the upstairs Mac that’s connected to your sound system.

Or maybe you just want to keep an eye on what your kids are doing on the Macs upstairs in their rooms.

The controlling person can do everything on the controlled Mac, including running programs, messing around with the folders and files, and even shutting it down.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: In fact, screen sharing has been enhanced in one especially juicy way in Mac OS X 10.6: Now you can press keystrokes on your Mac—⌘-Tab, ⌘-space, ⌘-Option-Escape, and so on—to trigger the corresponding functions on the other Mac. (In Mac OS X 10.5, your own Mac intercepted these keystrokes.)

If you want a keystroke to affect your own Mac, first click your own Desktop, or click into a different window on your own Mac.

Mac OS X is crawling with different ways to use screen sharing. You can do it over a network, over the Internet, and even during an iChat chat.

Truth is, the iChat method, described in Chapter 21, is much simpler and better than the small-network method described here. It doesn’t require names or passwords, it’s easy to flip back between seeing the other guy’s screen and your own, and you can transfer files by dragging them from your screen to the other guy’s (or vice versa).

Then again, the small-network method described here is built right into the Finder, doesn’t require logging into iChat, and doesn’t require Leopard or Snow Leopard running on both computers.

As always, trying to understand meta concepts like seeing one Mac’s screen on the monitor of another can get confusing fast. So in this example, suppose that you want to take control of Mac #1 while seated at Mac #2.

Now, it would be a chaotic world (although greatly entertaining) if any Mac could randomly take control of any other Mac. Fortunately, though, nobody can share your screen or take control of your Mac without your explicit permission.

To give such permission, choose  →System Preferences→Sharing, and then turn on Screen Sharing.

→System Preferences→Sharing, and then turn on Screen Sharing.

Note

If a message appears to the effect that “Screen Sharing is currently being controlled by the Remote Management service,” turn off the Remote Management checkbox and then try again.

At this point, there are three levels of security to protect your Mac against unauthorized remote-control mischief:

Secure. If you select All Users, anyone with an account on your Mac will be able to tap in and take control any time they like, even when you’re not around. They’ll just have to enter the same name and password they’d use if they were sitting in front of your machine.

If “anyone” means “you and your spouse” or “you and the other two fourth-grade teachers,” then that’s probably perfectly fine.

Securer. For greater security, though, you can limit who’s allowed to stop in. Click “Only these users” and then click the

sign. A small panel appears, listing everyone with an account on your Mac. Choose the ones you trust not to mess things up while you’re away from your Mac (Figure 13-16).

sign. A small panel appears, listing everyone with an account on your Mac. Choose the ones you trust not to mess things up while you’re away from your Mac (Figure 13-16).Securest. If you click “Only these users” and then don’t add anyone to the list, then only people who have Administrator accounts on your Mac (Administrator accounts) can tap into your screen.

Alternatively, if you’re only a little bit of a Scrooge, you can set things up so that they can request permission to share your screen—as long as you’re sitting in front of your Mac at the time and feeling generous.

To set this up, click Computer Settings and then turn on “Anyone may request permission to share screen.” Now your fans will have to request permission to enter, and you’ll have to grant it (by clicking OK on the screen), in real time, while you’re there to watch what they’re doing.

All right, Mac #1 has been prepared for invasion. Now suppose you’re the person on the other end. You’re the guru, or the parent, or whoever wants to take control.

Sit at Mac #2 elsewhere on your home or office network. Open a Finder window. Expand the Sharing list in the Sidebar, if necessary, so that you see the icon of Mac #1.

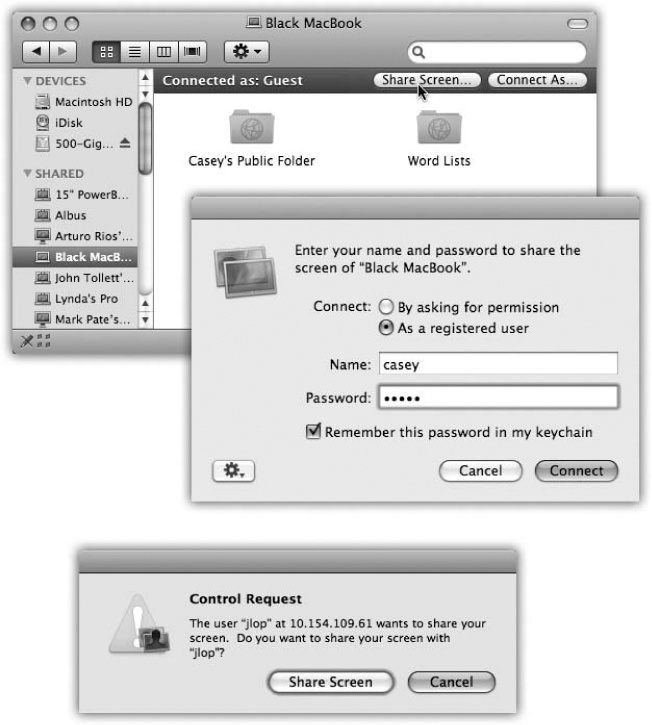

When you click that Mac’s icon, the dark strip at the top of the main window displays a button that wasn’t there before: Share Screen. Proceed as shown in Figure 13-17.

Tip

In theory, you can also connect from across the Internet, assuming you left your Mac at home turned on and connected to a broadband modem, and assuming you’ve worked through the port-forwarding issue described on Web Sharing.

In this case, though, you’d begin by choosing Go→Connect to Server in the Finder; in the Connect to Server box, type in vnc://123.456.78.90 (or whatever your home Mac’s public IP address is). The rest of the steps are the same.

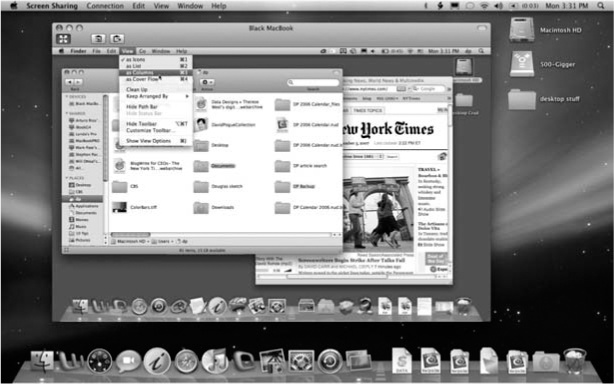

If you’ve signed in successfully, or if permission is granted, then a weird and wonderful sight appears. As shown in Figure 13-18, your screen now fills with a second screen—from the other Mac. You have full keyboard and mouse control to work with that other machine exactly as though you were sitting in front of it.

Well, maybe not exactly. There are a few caveats.

Mismatched screen sizes. If the other screen is smaller than yours, no big deal. It floats at actual size on your monitor, with room to spare. But if it’s the same size as yours or larger, then the other Mac’s screen gets shrunken down to fit in a window.

If you’d prefer to see it at actual size, choose View→Turn Scaling Off. Of course, now you have to scroll in the Screen Sharing window to see the whole image.

Tip

Another way to turn scaling on and off is to click the first button on the Screen Sharing toolbar (Figure 13-18).

The speed-vs.-blurriness issue. Remember, you’re asking the other Mac to pump its video display across the network—and that takes time. Entire milliseconds of time, in fact.

Figure 13-17. Top: Start by clicking Share Screen in the strip at the top of the other Mac’s window. Middle: If you’ve been pre-added to the VIP list of authorized screen sharers, as already described, you can sign in with your name and password. If not, you can request permission to share Mac #1’s screen. You’ll be granted permission only if Mac #1’s owner happens to be sitting in front of it at the moment and has opted to accept such requests. Bottom: If you request permission, the other person (sitting at Mac #1) sees your request in this form.

So ordinarily, the Mac uses something called adaptive quality, which just means that the screen gets blurry when you scroll, quit a program, or do anything else that creates a sudden change in the picture. You can turn off this feature by choosing View→Full Quality. Now you get full sharpness all the time—but things take longer to scroll, appear, and disappear.

Manage the Clipboard. Believe it or not, you can actually copy and paste material from the remote-controlled Mac to your own—or the other way—thanks to a freaky little wormhole in the time-space continuum.

Just make the Screen Sharing toolbar visible (you can see it in Figure 13-18). Click the second button on it to copy the faraway Mac’s Clipboard contents onto your Clipboard. Or click the third button to put what’s on your Clipboard onto the other Mac’s Clipboard. Breathe slowly and drink plenty of fluids, and your brain won’t explode.

Note

Unfortunately, there’s no way to transfer files while screen sharing—only material you’ve copied out of documents. Use the iChat method described in Chapter 21 if you want to exchange files.

Figure 13-18. Don’t be alarmed. You’re looking at the other Mac’s desktop in a window on your Mac desktop. You have keyboard and mouse control, and so does the other guy (if he’s there); when you’re really bored, you can play King of the Cursor. (Note the Screen Sharing toolbar, which has been made visible by choosing View→Show Toolbar.)

Quitting. When you hit the ⌘-Q keystroke, you don’t quit Screen Sharing; you quit whatever program is running on the other Mac! So when you’re finished having your way with the other computer, choose Screen Sharing→Quit Screen Sharing to return to your own desktop (and your own sanity).

The steps above guide you through screen sharing between two Leopard or Snow Leopard Macs. But screen-sharing is based on a standard technology called VNC, and Mac OS X is bristling with different permutations.

Two people who both have Mac OS X 10.5 or later can perform exactly the same screen-sharing stunt over the Internet. No accounts, passwords, or setup are required—only the granting of permission by the other guy. Just initiate an iChat chat, and then proceed as described on Sharing Your Screen. It’s really awesome.

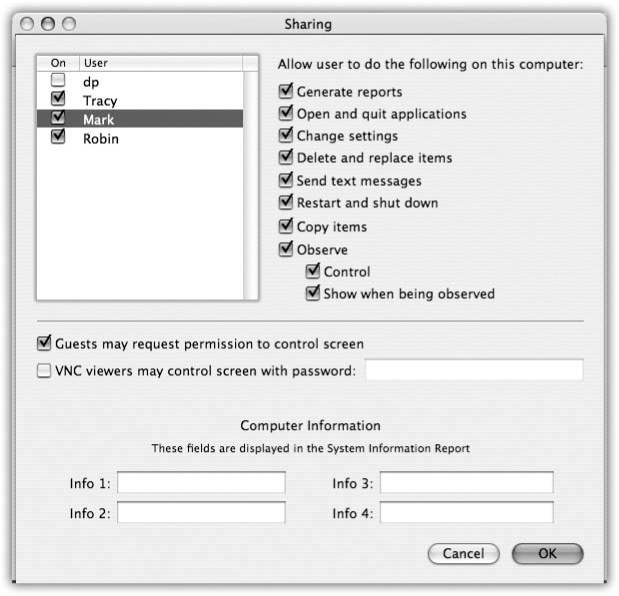

Both Macs don’t have to be running Mac OS X 10.5 or 10.6 to use screen sharing. As it turns out, Mac OS X 10.3 and 10.4 are capable of sharing their screens, too—it’s just that the on/off switch has a different name. Figure 13-19 has details.

Once you’ve turned on Apple Remote Desktop on the older Mac, as shown in Figure 13-19, you can sit at your Leopard/Snow Leopard Mac and take control by clicking Share Screen in the Sidebar, exactly as described above.

Note

At this point, the screen sharing is one-way: Your modern Mac can see the older Mac’s screen. If you want the older Mac to access your Mac’s screen, return to the box shown in Figure 13-19. Turn on “VNC viewers may control screen with password,” and make up a password. Now download the free Chicken of the VNC software; it’s available from this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com. Use it to access the Snow Leopard Mac; the box on Screen Sharing with Windows and Other Oddball Machines has more details on this concept.

Figure 13-19. On pre-10.5 Macs, there’s no option for Screen Sharing in the Sharing pane of System Preferences. There is one, however, called Apple Remote Desktop—and that’s the one that permits screen sharing with 10.5 and 10.6 machines. When you click it, you’re offered many of the same options that Snow Leopard offers. More, in fact.

Screen Sharing is an actual, double-clickable program, with its own icon on your Mac. (It’s in the System→Library→CoreServices folder.) When you double-click it, you can type in the public IP address (Web Sharing) or domain name of the computer you want to connect to, and presto: You’re connected!

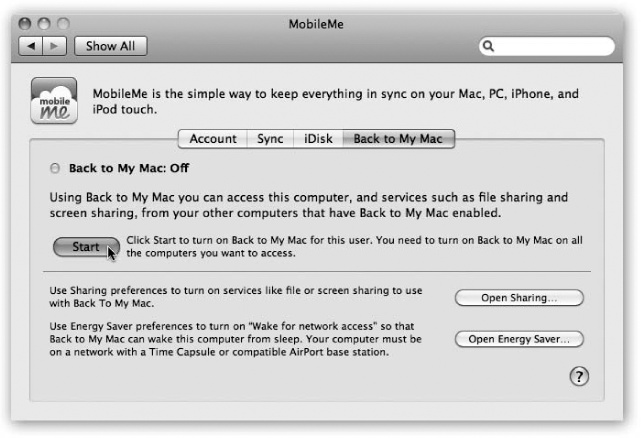

“Back to My Mac” is intended to simplify the nightmare of remote networking. It works only if:

You’re a MobileMe member.

You have at least two Macs, both running Leopard or Snow Leopard.

On each one, you’ve entered your MobileMe information into the MobileMe pane of System Preferences, and logged in.

Once that’s all in place, your Macs behave exactly as though they’re on the same home network, even though they can be thousands of miles apart across the network.

To set it up, proceed as shown in Figure 13-20.

Figure 13-20. On the first Mac, open System Preferences. Click MobileMe, and then click Back to My Mac. Click Start. Close System Preferences. Repeat on each Mac, making sure they all have the same MobileMe account information.

Now, on each Mac you’ll want to “visit” from afar, open the System Preferences→Sharing pane and turn on File Sharing and/or Screen Sharing.

Then, on your laptop in New Zealand, you see an entry for Back to My Mac in the Sharing section of your Sidebar. Click to see the icon of your Mac back at home. At this point, you can connect to it for file sharing by clicking Connect As (Connection Method A: Use the Sidebar), or take control of it by clicking Share Screen (Mac #2: Take Control).

In theory, Back to My Mac spares you an awful long visit to networking hell (including the port-forwarding headache described on Web Sharing), because Apple has done all the configuration work for you.

Note

Lots of people can’t get Back to My Mac to work. Apple says the problems are related to (a) firewalls, (b) port-forwarding issues, and (c) router incompatibilities. Apple also says you’ll have the best luck on networks that involve only an AirPort base station—and not a hardware router.

All the technical details are available online. Go to http://search.info.apple.com and do a search for 306672. (That’s the article number that explains the Back to My Mac issues.)

If you’re one of the several million lucky people who have full-time Internet connections—in other words, cable modem or DSL accounts—a special thrill awaits. You can connect to your Mac from anywhere in the world via the Internet. If you have a laptop, you don’t need to worry when you discover you’ve left a critical file on your desktop Mac at home.

Mac OS X offers several ways to connect to your Mac from a distant location, including file sharing over the Internet, Back to My Mac, virtual private networking, FTP, and SSH (secure shell). Chapter 22 has the details.