The hub of Mac customization is System Preferences, the modern-day successor to the old Control Panel (Windows) or Control Panels (previous Mac systems). Some of its panels are extremely important, because their settings determine whether or not you can connect to a network or go online to exchange email. Others handle the more cosmetic aspects of customizing Mac OS X.

This chapter guides you through the entire System Preferences program, panel by panel.

Tip

Only a system administrator (Administrator accounts) can change settings that affect everyone who shares a certain machine: its Internet settings, Energy Saver settings, and so on. If you see a bunch of controls that are dimmed and unavailable, now you know why.

A tiny padlock in the lower-left corner of a panel is the other telltale sign. If you, a nonadministrator, would like to edit some settings, then call an administrator over to your Mac and ask him to click the lock, input his password, and supervise your tweaks.

You can open System Preferences in dozens of ways:

Click its icon in the Dock.

Press Option-volume key (

,

,  , or

, or  on the top row of the keyboard), Option-brightness keys (

on the top row of the keyboard), Option-brightness keys ( or

or  ), or on laptops that have them, Option-keyboard-brightness keys (

), or on laptops that have them, Option-keyboard-brightness keys ( or

or  ). These tricks open the Sound and Displays panes, but you can then click Show All or press ⌘-L to see the full spread.

). These tricks open the Sound and Displays panes, but you can then click Show All or press ⌘-L to see the full spread.If you know the name of the System Preferences panel you want, it’s often quicker to use Spotlight. To open Energy Saver, for example, hit ⌘-space, type ener, and then press ⌘-Return. See Chapter 3 for more on operating Spotlight from the keyboard.

Here’s a new method in Snow Leopard that saves you a couple of steps. Turns out that if you put the System Preferences icon in your Dock (Chapter 4), you can open it and jump to a particular preference panel in one smooth move: Use your mouse to click-and-hold the System Preferences icon. You get a pop-up menu of every single System Preferences panel.

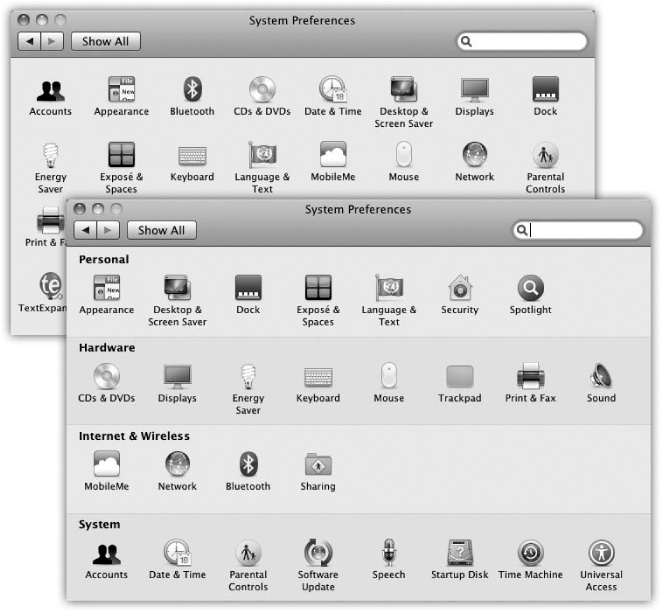

Suppose, then, that by hook or by crook, you’ve figured out how to open System Preferences. You’ll notice that, at first, the rows of icons are grouped according to function: Personal, Hardware, and so on (Figure 9-1, top). But you can also view them in tidy alphabetical order, as shown at bottom in Figure 9-1. That can spare you the ritual of hunting through various rows just to find a certain panel icon whose name you already know. (Quick, without looking: Which row is Date & Time in?) This chapter describes the various panels following this alphabetical arrangement.

Figure 9-1. You can view your System Preferences icons alphabetically (top), rather than in rows of arbitrary categories (bottom); just choose View→Organize Alphabetically. This approach not only saves space, but also makes finding a certain panel much easier, because you don’t need to worry about which category it’s in.

Either way, when you click one of the icons, the corresponding controls appear in the main System Preferences window. To access a different preference pane, you have a number of options:

Fast: When System Preferences first opens, the insertion point is blinking in the new System Preferences search box. (If the insertion point is not blinking there, press ⌘-F.) Type a few letters of volume, resolution, wallpaper, wireless, or whatever feature you want to adjust. In a literal illustration of Spotlight’s power, the System Preferences window darkens except for the icons where you’ll find relevant controls (Figure 9-2). Click the name or icon of the one that looks the most promising.

Figure 9-2. Even if you don’t know which System Preferences panel contains the settings you want to change, Spotlight can help. Type into the box at the top, and watch as the “spotlight” shines on the relevant icons. At that point, you can either click the icon, click the name in the pop-up menu, or arrow down the menu and press Return to choose.

Faster: Click the Show All icon in the upper-left corner of the window (or press ⌘-L, a shortcut worth learning). Then click the icon of the new panel you want.

Fastest: Choose any panel’s name from the View menu—or from the System Preferences Dock icon pop-up menu described above.

Note

Once System Preferences is actually open, the click-and-hold thing no longer produces the list of all preference panes. Instead, you need to Control-click (or right-click) the System Preferences Dock icon to get that menu.

Here, then, is your grand tour of all 27 of Snow Leopard’s built-in System Preferences panes. (You may have a couple more or fewer, depending on whether you have a laptop or a desktop Mac. And if you’ve installed any non-Apple panes, they appear in their own row of System Preferences, called Other.)

This is the master list of people who are allowed to log into your Mac. It’s where you can adjust their passwords, startup pictures, self-opening startup items, permissions to use various features of the Mac, and other security tools. All of this is described in Chapter 12.

This panel is mostly about how things look on the screen: windows, menus, buttons, scroll bars, and fonts. Nothing you find here lets you perform any radical surgery on the overall Mac OS X look—but you can tweak certain settings to match your personal style.

Two pop-up menus let you crank up or tone down Mac OS X’s overall colorfulness:

Appearance. Choose between Blue and Graphite. Blue refers to Mac OS X’s factory setting—bright, candy-colored scroll-bar handles, progress bars,

menu, and pulsing OK buttons—and those shiny red, yellow, and green buttons in the corner of every window. If you, like some graphics professionals, find all this circus-poster coloring a bit distracting, then choose Graphite, which renders all those interface elements in various shades of gray.

menu, and pulsing OK buttons—and those shiny red, yellow, and green buttons in the corner of every window. If you, like some graphics professionals, find all this circus-poster coloring a bit distracting, then choose Graphite, which renders all those interface elements in various shades of gray.Highlight color. When you drag your cursor across text, its background changes color to indicate that you’ve selected it. Exactly what color the background becomes is up to you—just choose the shade you want using the pop-up menu. The Highlight color also affects such subtleties as the lines on the inside of a window as you drag an icon into it.

If you choose Other, the Color Picker palette appears, from which you can choose any color your Mac is capable of displaying (Uninstalling Software).

The two sets of radio buttons control the scroll-bar arrow buttons of all your windows. You can keep these arrows together at one end of the scroll bar, or you can split them up so the “up” arrow sits at the top of the scroll bar and the “down” arrow is at the bottom. (Horizontal scroll bars are similarly affected.) For details on the “Jump to the next page” and “Jump to here” options, see Resize Handle.

Tip

And what if you want the ultimate convenience: both arrows at both ends of the scroll bar? You just need a moment alone with TinkerTool, described on TinkerTool: Customization 101.

You can also turn on these checkboxes:

Use smooth scrolling. This option affects only one tiny situation: when you click (or hold the cursor down) inside the empty area of the scroll bar (not on the handle, and not on the arrow buttons). And it makes only one tiny change: Instead of jumping abruptly from screen to screen, the window lurches with slight accelerations and decelerations, so that the paragraph you’re eyeing never jumps suddenly out of view.

Minimize when double-clicking a window title bar. This option provides another way to minimize a window. In addition to the tiny yellow Minimize button at the upper-left corner of the window, you now have a much bigger target—the entire title bar.

Just how many of your recently opened documents and applications do you want the Mac to show using the Recent Items command in the  menu? Pick a number from the pop-up menus. For example, you might choose 30 for documents, 20 for programs, and 5 for servers.

menu? Pick a number from the pop-up menus. For example, you might choose 30 for documents, 20 for programs, and 5 for servers.

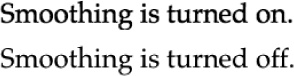

The Mac’s built in text-smoothing (antialiasing) feature is supposed to produce smoother, more commercial-looking text anywhere it appears on your Mac: in word processing documents, email messages, Web pages, and so on.

Experiment with the on/off checkbox—“Use LCD font smoothing when available,” for example—to see how you like the effect. Either way, it’s fairly subtle. (See Figure 9-3.) Furthermore, unlike most System Preferences, this one has no effect until the next time you open the program in question. In the Finder, for example, you won’t notice the difference until you log out and log back in again.

At smaller type sizes (10-point and smaller), you might find that text is actually less readable with font smoothing turned on. It all depends upon the font, the size, your monitor, and your taste. For that reason, this pop-up menu lets you choose a cutoff point. If you choose 12 here, for example, then 12-point (and smaller) type still appears crisp and sharp; only larger type, such as headlines, displays the graceful edge smoothing. You can choose a size cutoff as low as 4-point.

(None of these settings affect your printouts, only the onscreen display.)

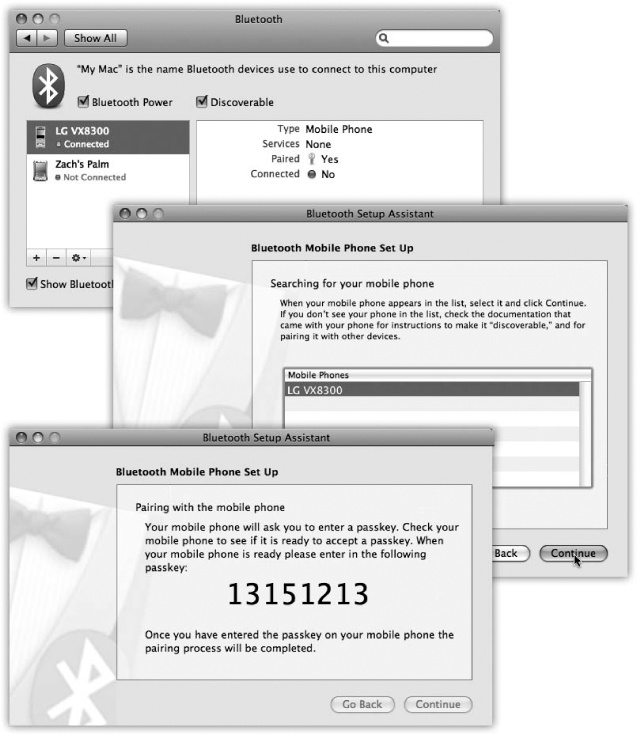

Bluetooth is a short-range, low-power, wireless cable-elimination technology. It’s designed to connect gadgets in pairings that make sense, like cellphone+earpiece, wireless keyboard+Mac, or Mac+cellphone (to connect to the Internet or to transmit files).

Now, you wouldn’t want the guy in the next cubicle to be able to operate your Mac using his Bluetooth keyboard. So the first step in any Bluetooth relationship is pairing, where you formally introduce the two gadgets that will be communicating. Here’s how that goes:

Open System Preferences→Bluetooth.

Make sure the On checkbox is turned on. (The only reason to turn it off is to save laptop battery power.) Also make sure Discoverable is turned on; that makes the Mac “visible” to other Bluetooth gadgets in range.

Click the

button below the list at left.

button below the list at left.The Bluetooth Setup Assistant opens. After a moment, it displays the names of all Bluetooth gadgets it can sniff out: nearby headsets, laptops, cellphones, and so on. Usually, it finds the one you’re trying to pair.

Click the gadget you want to connect to, and then click Continue.

If you’re pairing a mobile phone or something else that has a keypad or keyboard, the Mac now displays a large, eight-digit passcode. It’s like a password, except you’ll have to input it only this once, to confirm that you are the true owner of both the Mac and the gadget. (If it weren’t for this passcode business, some guy next to you at the airport could enjoy free laptop Internet access through the cellphone in your pocket.)

At this point, your phone or palmtop displays a message to the effect that you have 30 seconds to type that passcode. Do it. When the gadget asks if you want to pair with the Mac and connect to it, say yes.

If you’re pairing a phone or palmtop, the Mac now asks which sorts of Bluetooth syncing you want to do. For example, it can copy your iCal appointments, as well as your Address Book, to the phone or palmtop.

(Or, if there are no kinds of Bluetooth syncing that your Mac can do with the gadget—for example, unless your cellphone offers Bluetooth file transfers, there may be nothing it can accomplish by talking to your Mac—an error message tells you that, too.)

Tip

A few Bluetooth phones, including the iPhone, can even get your laptop onto the Internet via the cellular airwaves. No WiFi required—the phone never even leaves your pocket, and your laptop can get online wherever there’s a cellphone signal.

This is a special setup, however, involving signing up with your cell carrier (and paying an additional monthly fee). If you’ve signed up, then turn on the third option here (“Access the Internet”).

When it’s all over, the new gadget is listed in the left-side panel, in the list of Bluetooth cellphones, headsets, and other stuff that you’ve previously introduced to this Mac. Click the  button to open the Bluetooth Setup Assistant again, or the

button to open the Bluetooth Setup Assistant again, or the  button to delete one of the listed items.

button to delete one of the listed items.

If you click Advanced, you arrive at a pop-up panel with a few more tweaky Bluetoothisms:

Figure 9-4. Top: This System Preferences panel reveals a list of every Bluetooth gadget your Mac knows about. Click a Bluetooth device to see details. Middle: The Bluetooth Setup Assistant scans the area for Bluetooth gadgets and, after a moment, lists them. Click one, and then click Continue. Bottom: Where security is an issue, the Assistant offers you the chance to pair your Bluetooth device with the Mac. To prove that you’re really the owner of both the laptop and the phone, the Mac displays a one-time password, which you have 30 seconds to type into the phone. Once that’s done, you’re free to use the phone’s Internet connection without any further muss, fuss, or passwords.

Open Bluetooth Assistant at startup when no input device is present. Here’s where you can tell the Bluetooth Setup Assistant to open up automatically when the Mac thinks no keyboard and mouse are attached (because it assumes that you have a wireless Bluetooth keyboard and mouse that have yet to be set up).

Allow Bluetooth devices to wake this computer. Turn this on if you want to be able to wake up a sleeping Mac when you press a key, just like a wired keyboard does.

Prompt for all incoming audio requests. The Mac will let you know if your Bluetooth cellphone, music player, or another music gadget tries to connect.

Share my Internet connection with other Bluetooth devices. Pretty obscure—but when the future arrives, Mac OS X will be ready. The PAN service referred to in the description of this item lets your Mac, which presumably has a wired or WiFi Internet connection, share that connection with Bluetooth gadgets (like palmtops) that don’t have an Internet connection.

Serial ports. This list identifies which simulated connections are present at the moment. It’s a reference to those different Bluetooth profiles (features) that various gadgets can handle. They include Bluetooth File Transfer (other people with Bluetooth Macs can see a list of what’s in your Public folder and help themselves; see Fetching a file), Bluetooth File Exchange (other people can send files to you using Bluetooth; Via Flash Drive), Bluetooth-PDA-Sync (personal digital assistants—that is, Palm organizers—can sync with your Mac via Bluetooth); and so on.

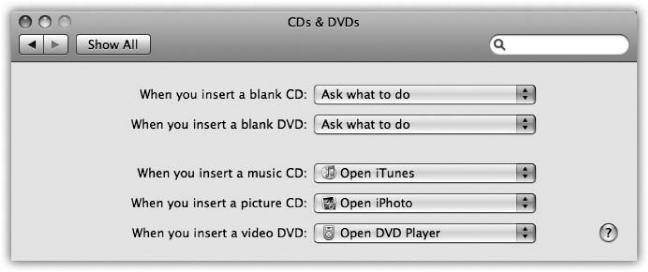

This handy pane (Figure 9-5) lets you tell the Mac what it should do when it detects that you’ve inserted a CD or DVD. For example, when you insert a music CD, you probably want iTunes (Chapter 11) to open automatically so you can listen to the CD or convert its musical contents to MP3 or AAC files on your hard drive. Similarly, when you insert a picture CD (such as a Kodak Photo CD), you probably want iPhoto to open in readiness to import the pictures from the CD into your photo collection. And when you insert a DVD from Blockbuster, you want the Mac’s DVD Player program to open.

Figure 9-5. You can tell the Mac exactly which program to launch when you insert each kind of disc, or tell it to do nothing at all.

For each kind of disc (blank CD, blank DVD, music CD, picture CD, or video DVD), the pop-up menu lets you choose options like these:

Ask what to do. A dialog box appears that asks what you want to do with the newly inserted disc.

Open (iDVD, iTunes, iPhoto, DVD Player…). The Mac can open a certain program automatically when you insert the disc. When the day comes that somebody writes a better music player than iTunes, or a better digital shoebox than iPhoto, then you can use the “Open other application” option.

Run script. If you’ve become handy writing or downloading AppleScript programs (Chapter 7), you can schedule one of your own scripts to take over from here. For example, you can set things up so that inserting a blank CD automatically copies your Home folder onto it for backup purposes.

Ignore. The Mac won’t do anything when you insert a disc except display its icon on the desktop. (If it’s a blank disc, the Mac does nothing at all.)

Your Mac’s conception of what time it is can be very important. Every file you create or save is stamped with this time, and every email you send or receive is marked with this time. As you might expect, setting your Mac’s clock is what the Date & Time pane is all about.

Click the Date & Time tab. If your Mac is online, turn on “Set date & time automatically” and be done with it. Your Mac sets its own clock by consulting a highly accurate scientific clock on the Internet. (No need to worry about daylight saving time, either; the time servers take that into account.)

Tip

If you have a full-time Internet connection (cable modem or DSL, for example), you may as well leave this checkbox turned on, so your Mac’s clock is always correct. If you connect to the Internet by dial-up modem, however, turn off the checkbox, so your Mac won’t keep trying to dial spontaneously at all hours of the night.

If you’re not online and have no prospect of getting there, you can also set the date and time manually. To change the month, day, or year, click the digit that needs changing and then either (a) type a new number or (b) click the little arrow buttons. Press the Tab key to highlight the next number. (You can also specify the day of the month by clicking a date on the minicalendar.)

To set the time of day, use the same technique—or, for more geeky fun, you can set the time by dragging the hour, minute, or second hands on the analog clock. Finally, click Save. (If you get carried away with dragging the clock hands around and lose track of the real time, click the Revert button to restore the panel settings.)

Tip

If you’re frustrated that the Mac is showing you the 24-hour “military time” on your menu bar (that is, 17:30 instead of 5:30 p.m.)—or that it isn’t showing military time when you’d like it to—click the Clock tab and turn “Use a 24-hour clock” on or off.

Note, however, that this affects only the menu bar clock. If you’d like to reformat the menu bar clock and all other dates (like the ones that show when your files were modified in list views), click the Open Language & Text button at the bottom of the Date & Time pane. Once there, click the Formats tab. There you’ll see a Customize button for Times, which leads you to a whole new world of time-format customization. You can drag elements of the current time (Hour, Minute, Second, Millisecond, and so on) into any order you like, and separate them with any desired punctuation. This way, you can set up your date displays in (for example) the European format, expressing April 13 as 13/4 instead of 4/13).

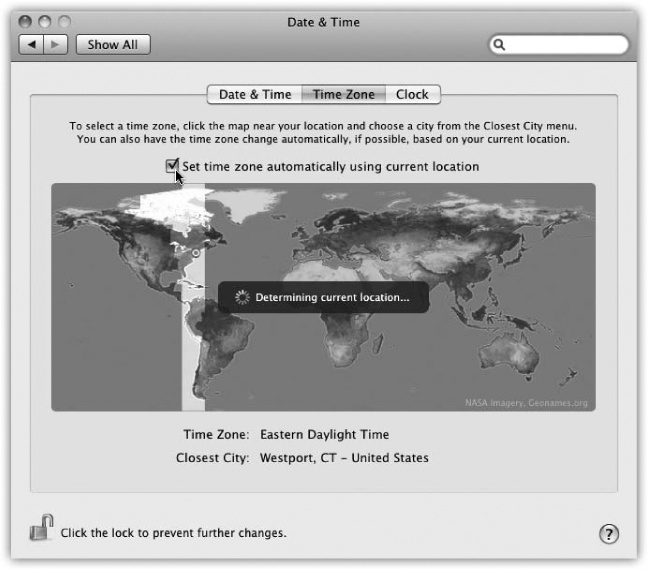

You’d be surprised how important it is to set the time zone for your Mac. If you don’t do so, the email and documents you send out—and the Mac’s conception of what documents are older and newer—could be hopelessly skewed.

You can teach your Mac where it lives by using what may be Snow Leopard’s snazziest new feature: its ability to set its own time zone automatically. That’s an especially useful feature if you’re a laptop warrior who travels a lot.

Just turn on “Set time zone automatically using current location” (Figure 9-6). If possible, the Mac will think for a moment and then, before your eyes, drop a pin onto the world map to represent your location—and set the time zone automatically. (The world map goes black-and-white to show that you can no longer set your location manually.)

Figure 9-6. To set your time zone the quick and dirty way, click a section of the map to indicate your general region of the world. To teach the Mac more precisely where you are in that time zone, use the Closest City pop-up menu. (Or, instead of using the pop-up menu with the mouse, you can also highlight the text in the Closest City box. Then start typing your city name until the Mac gets it.)

Often, you’ll be told that the Mac is “Unable to determine current location at this time.” In that case, specify your location manually, as shown in Figure 9-6.

In the Clock pane, you can specify whether or not you want the current time to appear, at all times, at the right end of your menu bar. You can choose between two different clock styles: digital (3:53 p.m.) or analog (a round clock face). You also get several other options that govern this digital clock display: the display of seconds, whether or not you want to include designations for a.m. and p.m., the day of the week, a blinking colon, and the option to use a 24-hour clock.

Tip

At the bottom of the dialog box, you’ll find a feature called “Announce the time.” At the intervals you specify, the Mac can speak, out loud, the current time: “It’s 10 o’clock.” If you tend to get so immersed in “working” that you lose track of time, Mac OS X just removed your last excuse.

In Snow Leopard, there’s a handy new feature: For the first time since the birth of Mac OS X, the menu-bar clock can show not just the time, not just the day of the week, but also today’s date. Turn on the “Show the day of the week” and “Show date” checkboxes if you want to see, for example, “Wed May 5 7:32 PM” on your menu bar.

If you decide you don’t need all that information—if your menu bar is crowded enough as it is—you can always look up today’s day and date just by clicking the time on your menu bar. A menu drops down revealing the complete date. The menu also lets you switch between digital and analog clock types and provides a shortcut to the Date & Time preferences pane.

Tip

This one’s for Unix geeks only. You can also set the date and time from within Terminal (Chapter 16). Use sudo (sudo), type date yyyymmddhhmm.ss, and press Enter. (Of course, replace that code with the actual date and time you want, such as 201004051755.00 for April 5, 2010, 5:55 p.m.) You might find this method faster than the System Preferences route.

This panel offers two ways to show off Mac OS X’s glamorous graphics features: desktop pictures and screen savers.

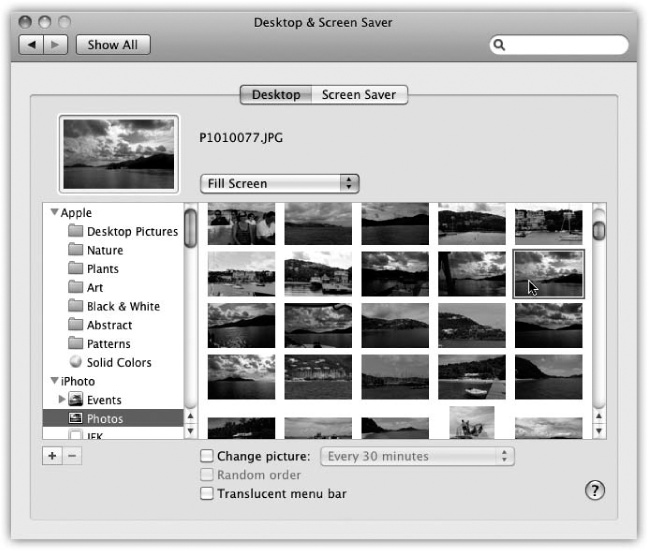

Mac OS X comes with several ready-to-use collections of desktop pictures, ranging from National Geographic—style nature photos to plain solid colors. To install a new background picture, first choose one of the image categories in the list at the left side of the window, as shown in Figure 9-7.

Figure 9-7. Using the list of picture sources at left, you can preview an entire folder of your own images before installing one specific image as your new desktop picture. Use the  button to select a folder of assorted graphics—or, if you’re an iPhoto veteran, click an iPhoto album name, as shown here. Clicking one of the thumbnails installs the corresponding picture on the desktop.

button to select a folder of assorted graphics—or, if you’re an iPhoto veteran, click an iPhoto album name, as shown here. Clicking one of the thumbnails installs the corresponding picture on the desktop.

Your choices include Desktop Pictures (muted, soft-focus swishes and swirls), Nature (bugs, water, snow leopard, outer space), Plants (flowers, soft-focus leaves), Black & White (breathtaking monochrome shots), Abstract (swishes and swirls with wild colors), Patterns (a pair of fabric close-ups), or Solid Colors (simple grays, blues, and greens).

Of course, you may feel that decorating your Mac desktop is much more fun if you use one of your own pictures. You can use any digital photo, scanned image, or graphic you want in almost any graphics format (JPEG, PICT, GIF, TIFF, Photoshop, and—just in case you hope to master your digital camera by dangling its electronic instruction manual in front of your nose each morning—even PDF).

That’s why icons for your own Pictures folder and iPhoto albums also appear here, along with a  button that lets you choose any folder of pictures. When you click one of these icons, you see thumbnail versions of its contents in the main screen to its right. Just click the thumbnail of any picture to apply it immediately to the desktop. (There’s no need to remove the previously installed picture first.)

button that lets you choose any folder of pictures. When you click one of these icons, you see thumbnail versions of its contents in the main screen to its right. Just click the thumbnail of any picture to apply it immediately to the desktop. (There’s no need to remove the previously installed picture first.)

Tip

If there’s one certain picture you like, but it’s not in any of the listed sources, you can drag its image file onto the well (the miniature desktop displayed in the Desktop panel). A thumbnail of your picture instantly appears in the well and, a moment later, the picture is plastered across your monitor.

No matter which source you use to choose a photo of your own, you have one more issue to deal with. Unless you’ve gone to the trouble of editing your chosen photo so that it matches the precise dimensions of your screen (1280 x 854 pixels, for example), it probably isn’t exactly the same size as your screen.

Tip

The top 23 pixels of your graphic are partly obscured by Snow Leopard’s translucent menu bar—something to remember when you prepare the graphic. Then again, you can also make the menu bar stop being translucent—by turning off the “Translucent menu bar” checkbox shown in Figure 9-7.

Fortunately, Mac OS X offers a number of solutions to this problem. Using the popup menu just to the right of the desktop preview well, you can choose any of these options:

Fit to Screen. Your photo appears as large as possible without distortion or cropping. If the photo doesn’t precisely match the proportions of your screen, you get “letterbox bars” on the sides or at top and bottom. (Use the swatch button just to the right of the pop-up menu to specify a color for those letterbox bars.)

Fill Screen. Enlarges or reduces the image so that it fills every inch of the desktop without distortion. Parts may get chopped off. At least this option never distorts the picture, as the “Stretch” option does (below).

Stretch to Fill Screen. Makes your picture fit the screen exactly, come hell or high water. Larger pictures may be squished vertically or horizontally as necessary, and small pictures are drastically blown up and squished, usually with grisly results.

Center. Centers the photo neatly on the screen. The margins of the picture may be chopped off.

If the picture is smaller than the screen, it sits smack in the center of the monitor at actual size, leaving a swath of empty border all the way around. As a remedy, Apple provides a color-swatch button next to the pop-up menu (also shown in Figure 9-7). When you click it, the Color Picker appears (Uninstalling Software), so that you can specify the color in which to frame your little picture.

Tile. This option makes your picture repeat over and over until the multiple images fill the entire monitor. (If your picture is larger than the screen, no such tiling takes place. You see only the top center chunk of the image.)

The novelty of any desktop picture, no matter how interesting, is likely to fade after several months of all-day viewing. That’s why the randomizing function is so delightful.

Turn on “Change picture” at the bottom of the dialog box. From the pop-up menu, specify when you want your background picture to change: “Every day,” “Every 15 minutes,” or, if you’re really having trouble staying awake at your Mac, “Every 5 seconds.” (The option called “When waking from sleep” refers to the Mac waking from sleep, not its owner.)

Finally, turn on “Random order,” if you like. If you leave it off, your desktop pictures change in alphabetical order by file name.

That’s all there is to it. Now, at the intervals you specified, your desktop picture changes automatically, smoothly cross-fading between the pictures in your chosen source folder like a slideshow. You may never want to open another window, because you’ll hate to block your view of the show.

On the Screen Saver panel, you can create your own screen-saver slideshows—an absolute must if you have an Apple Cinema Display and a cool Manhattan loft apartment.

Tip

Of course, a screen saver doesn’t really save your screen. LCD flat-panel screens, the only kind Apple sells, are incapable of “burning in” a stationary image of the sort that originally inspired the creation of screen savers years ago.

No, these screen savers offer two unrelated functions. First, they mask what’s on your screen from passersby whenever you leave your desk. Second, they’re kind of fun.

When you click a module’s name in the Screen Savers list, you see a mini version of it playing back in the Preview screen. Click Test to give the module a dry run on your full monitor screen.

When you’ve had enough of the preview, just move the mouse or press any key. You return to the Screen Saver panel.

Apple provides a few displays to get you started, in two categories: Apple and Pictures.

Arabesque. Your brain will go crazy trying to make sense of the patterns of small circles as they come and go, shrink and grow. But forget it; this module is all just drugged-out randomness.

Computer Name. This display shows nothing more than the Apple logo and the computer’s name, faintly displayed on the monitor. (These elements shift position every few minutes—it just isn’t very fast.) Apple probably imagined that this feature would let corporate supervisors glance over at the screens of unattended Macs to find out who was not at their desks.

Flurry. You get flaming, colorful, undulating arms of fire, which resemble a cross between an octopus and somebody arc welding in the dark. If you click the Options button, you can control how many streams of fire appear at once, the thickness of the arms, the speed of movement, and the colors.

iTunes Artwork. Somebody put a lot of work into the album covers for the CDs whose music you own—so why not enjoy them as art? This module builds a gigantic mosaic of album art from your music collection, if you have one. The tiles periodically flip around, just to keep the image changing. (The Options button lets you specify how many rows of album-art squares appear, and how often the tiles flip.)

RSS Visualizer. Here, buried 43 layers deep in the operating system, is one of Mac OS X’s most spectacular and useful features: the RSS Visualizer. When this screen saver kicks in, it shows a jaw-dropping, 3-D display of headlines (news and other items) slurped in from the Safari Web browser’s RSS reader. (RSS items, short for Really Simple Syndication or Rich Site Summary, are like a cross between email messages and Web pages—they’re Web items that get sent directly to you. Details in Chapter 20.)

After the introductory swinging-around-an-invisible-3-D-pole-against-a-swirling-blue-sky-background sequence, the screen saver displays one news blurb at a time. Each remains on the screen just long enough for you to get the point of the headline. Beneath, in small type, is the tantalizing instruction, “Press the ‘3’ key to continue.” (It’s a different number key for each headline.) If you do, indeed, tap the designated key, you leave the screen saver, fire up Safari, and wind up on a Web page that contains the complete article you requested.

The whole thing is gorgeous, informative, and deeply hypnotic. Do not use while operating heavy equipment.

Shell. Five swirling fireworky spinners, centered around a bigger one.

Spectrum. This one’s for people who prefer not to have anything specific on their screens, like photos or text; instead, it fills the screen with a solid color that gradually shifts to other glowing rainbow hues.

Word of the Day. A parade of interesting words drawn from the Dictionary program. You’re invited to tap the D key to open the dictionary to that entry to read more. Build your word power!

The screen savers in this category are all based on the slideshowy presentation of photos. You can choose from three presentations of pictures in whatever photo group you choose, as represented by the three Display Style buttons just below the screen-saver preview.

Slideshow displays one photo at a time; they slowly zoom and cut into each other.

Tip

If you click Options, you get choices like “Present slides in random order” (instead of the order they appear in Apple’s photo folder, or yours); “Cross-fade between slides” (instead of just cutting abruptly); “Zoom back and forth” (that is, slowly enlarge or shrink each photo to keep it interesting); “Crop slides to fit on screen” (instead of exposing letterbox bars of empty desktop if the photo’s shape doesn’t match the screen’s); and “Keep slides centered” (instead of panning gracefully across).

Collage sends individual photos spinning randomly onto the “table,” where they lie until the screen is full.

Mosaic will blow your mind; see Figure 9-8.

Tip

Click the Options button to specify the speed of the receding, the number of photos that become pixels of the larger photo, and whether or not you want the composite photos to appear in random order.

In any case, all these photo-show options are available for whatever photo set you choose from the list at left. These are your choices:

Abstract, Beach, Cosmos, Forest, Nature Patterns, Paper Shadow. Abstract features psychedelic swirls of modern art. In the Beach, Cosmos, Forest, and Nature screen savers, you see a series of tropical ocean scenes, deep space objects, lush rain forests, and leaf/flower shots. Paper Shadow is a slideshow of undulating, curling, black-and-white shadowy abstract forms.

Each creates an amazingly dramatic, almost cinematic experience, worthy of setting up to “play” during dinner parties like the lava lamps of the ’70s.

iPhoto albums. If you’re using iPhoto to organize your digital photos, you’ll see its familiar album and Event lists here, making it a snap to choose any of your own photo collections for use as a screen saver.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: A new option debuts here: Flagged. It displays only the photos you’ve flagged in iPhoto—which you do by clicking a photo and pressing ⌘-period—which gives you more freedom than having to choose one prepared album or another.

Figure 9-8. This feeble four-frame sample will have to represent, on this frozen page, the stunning animated pull-out that is the Mosaic screen saver. It starts with one photo (top); your “camera” pulls back farther and farther, revealing that that photo is just one in a grid—a huge grid—that’s comprised of all your photos. As you pull even further back, each photo appears so small that it becomes only one dot of another photo—from the same collection! And then that one starts shrinking, and the cycle repeats, on and on into infinity.

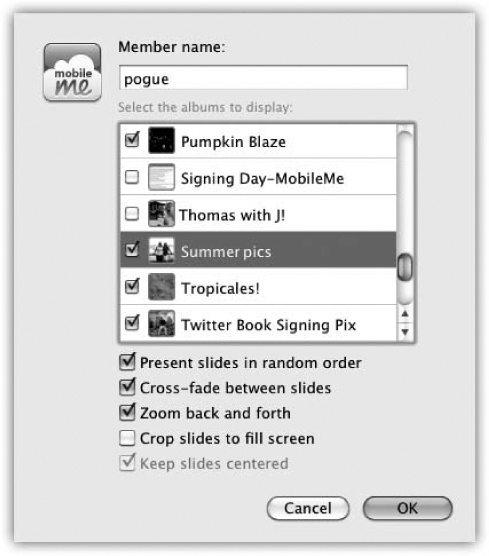

MobileMe albums. One of the perks of paying $100 per year for a MobileMe membership is the ability to create slideshows online. If you’ve published some of them, their names show up here.

Weirder yet, you can also enjoy a screen saver composed of photos from somebody else’s MobileMe gallery. (“Oh, look, honey, here’s some shots of Uncle Jed’s crops this summer!”)

Click the

button and choose MobileMe Gallery. You’re asked which member’s slideshow collection you want to view and how you want it to appear (Figure 9-9).

button and choose MobileMe Gallery. You’re asked which member’s slideshow collection you want to view and how you want it to appear (Figure 9-9).

Tip

If you click the  button and choose RSS Feed, can also specify an RSS feed’s address. The idea, of course, is that you’d specify a photo RSS feed’s address here, like the ones generated by iPhoto.

button and choose RSS Feed, can also specify an RSS feed’s address. The idea, of course, is that you’d specify a photo RSS feed’s address here, like the ones generated by iPhoto.

If you set up more than one MobileMe and RSS-feed address here, the screen saver presents them as sequential slideshows. Drag them up or down the list to change their order.

Figure 9-9. Once you enter a MobileMe member’s name, you’re shown that person’s list of public photo albums. At this point, you can also specify how you want the screen saver to look: Turn off the crossfade between slides, crop the slides so they fit on the screen, present the slides in random order, and so on.)

Whichever screen-saver module you use, you have two further options:

Use random screen saver. If you can’t decide which one of the modules to use, turn on this checkbox. The Mac chooses a different module each time your screen saver kicks in.

Show with clock. This option just superimposes the current time on whatever screen saver you’ve selected. You’d be surprised at how handy it can be to use your Mac as a giant digital clock when you’re getting coffee across the room.

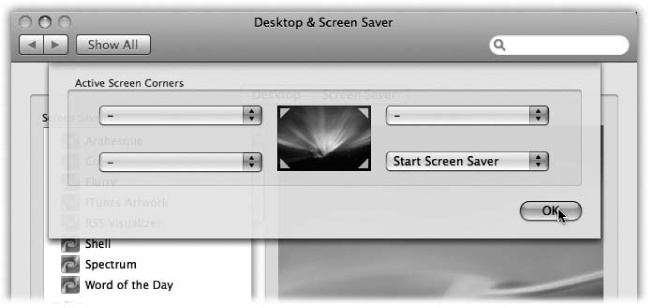

You can control when your screen saver takes over in a couple of ways:

After a period of inactivity. Using the “Start screen saver” slider, you can set the amount of time that has to pass without keyboard or mouse activity before the screen saver starts. The duration can be as short as 3 minutes or as long as 2 hours, or you can drag the slider to Never to prevent the screen saver from ever turning on by itself.

Tip

The screensaver can auto-lock your Mac after a few minutes (and require the password to get back in)—a great security safety net when you wander away from your desk. See Logout Options.

When you park your cursor in the corner of the screen. If you click the Hot Corners button, you see that you can turn each corner of your monitor into a hot corner (Figure 9-10).

Tip

You can find dozens more screen saver modules from Apple. To look them over, click the  button below the list; choose Browse Screen Savers. You’re taken to www.apple.com/downloads/macosx/icons_ screensavers, where you can choose from a selection of amazing add-on screensaver modules. (The older ones may not be compatible with Snow Leopard’s new 64-bit design, however.)

button below the list; choose Browse Screen Savers. You’re taken to www.apple.com/downloads/macosx/icons_ screensavers, where you can choose from a selection of amazing add-on screensaver modules. (The older ones may not be compatible with Snow Leopard’s new 64-bit design, however.)

Displays is the center of operations for all your monitor settings. Here, you set your monitor’s resolution, determine how many colors are displayed onscreen, and calibrate color balance and brightness.

Tip

You can open up this panel with a quick keystroke from any program on the Mac. Just press Option as you tap one of the screen-brightness keys on the top row of your keyboard.

The specific controls depend on the kind of monitor you’re using, but here are the ones you’ll most likely see:

This tab is the main headquarters for your screen controls. It governs these settings:

Resolutions. All Mac screens today can make the screen picture larger or smaller, thus accommodating different kinds of work. You perform this magnification or reduction by switching among different resolutions (measurements of the number of dots that compose the screen). The Resolutions list displays the various resolution settings your monitor can accommodate: 800 x 600, 1024 x 768, and so on.

When you use a low-resolution setting, such as 800 x 600, the dots of your screen image get larger, thus enlarging (zooming in on) the picture—but showing a smaller slice of the page. Use this setting when playing a small QuickTime movie, for example, so that it fills more of the screen. (Lower resolutions usually look blurry on flat-panel screens, though.) At higher resolutions, such as 1280 x 800, the screen dots get smaller, making your windows and icons smaller, but showing more overall area. Use this kind of setting when working on two-page spreads in your page-layout program, for example.

Tip

You can adjust the resolution of your monitor without having to open System Preferences. Just turn on “Show displays in menu bar,” which adds a Displays pop-up menu (a menulet) to the right end of your menu bar for quick adjustments. (If you choose Number of Recent Items—did Apple really mean for this command to say that?—then you can adjust how many common resolutions are listed in this menulet.)

Colors, Refresh Rate, Brightness, Contrast. If you’re still using a CRT screen—that is, not a flat panel—these additional controls appear. Colors specifies how many colors your screen can display (256, Thousands, and so on)—an option that’s here only for nostalgia’s sake, since no normal person would deliberately want photos to look worse. Refresh Rate controls how many times per second your screen image is repainted by your monitor’s electron gun. Choose a setting that minimizes flicker. Finally, the Brightness and Contrast sliders let you make the screen look good in the prevailing lighting conditions.

Of course, most Apple keyboards have brightness-adjustment keys, so these software controls are included just for the sake of completeness.

Automatically adjust brightness as ambient light changes. This option appears only if you have a Mac laptop with a light-up keyboard. In that case, your laptop’s light sensor also dims the screen automatically in dark rooms—if this checkbox is turned on. (Of course, you can always adjust the keyboard lighting manually, by tapping the

and

and  keys.)

keys.)

This pane appears only on Macs with those increasingly rare CRT (that is, non-flat) screens. It lets you adjust the position, size, and angle of the screen image on the glass itself—controls that can be useful in counteracting distortion in aging monitors.

From the dawn of the color-monitor era, Macs have had a terrific feature: the ability to exploit multiple monitors all plugged into the computer at the same time. Any Mac with a video-output jack (laptops, iMacs), or any Mac with a second or third video card (Power Macs, Mac Pros), can project the same thing on both screens (mirror mode); that’s useful in a classroom when the “external monitor” is a projector.

Tip

The standard video card in a Mac Pro has jacks for two monitors. By installing more video cards, you can get up to six monitors going at once.

But it’s equally useful to make one monitor act as an extension of the next. For example, you might have your Photoshop image window on your big monitor but keep all the Photoshop controls and tool palettes on a smaller screen. Your cursor passes from one screen to another as it crosses the boundary.

You don’t have to shut down the Mac to hook up another monitor. Just hook up the monitor or projector and then choose Detect Displays from the Displays menulet.

When you open System Preferences, you see a different Displays window on each screen, so that you can change the color and resolution settings independently for each. Your Displays menulet shows two sets of resolutions, too, one for each screen.

If your Mac can show different images on each screen, then your Displays panel offers an Arrangement tab, showing a miniature version of each monitor. By dragging these icons around relative to each other, you can specify how you want the second monitor’s image “attached” to the first. Most people position the second monitor’s image to the right of the first, but you’re also free to position it on the left, above, below, or even directly on top of the first monitor’s icon (the last of which produces a video-mirroring setup). For the least likelihood of going insane, consider placing the real-world monitor into the same position.

For committed multiple-monitor fanatics, the fun doesn’t stop there. See the microscopic menu bar on the first-monitor icon? You can drag that tiny strip onto a different monitor icon, if you like, to tell Displays where you’d like your menu bar to appear. (And check out how most screen savers correctly show different stuff on each monitor!)

This pane offers a list of color profiles for your monitor (or, if you turn off “Show profiles for this display only,” for all monitors). Each profile represents colors slightly differently—a big deal for designers and photo types. See Getting ColorSync Profiles for more on color profiles.

When you click Calibrate, the Display Calibrator Assistant opens to walk you through a series of six screens, presenting various brightness and color-balance settings in each screen. You pick the settings that look best to you; at the end of the process, you save your monitor tweaks as a ColorSync profile, which ColorSync-savvy programs can use to adjust your display for improved color accuracy.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: Speaking of options that only color nerds will appreciate: The standard gamma (contrast) setting in Snow Leopard has been changed from 1.8 to 2.2. That is, the overall contrast has been boosted to a level that matches Windows and most TV sets. Supposedly that’s something that graphics pros had been clamoring for. If you prefer the older look, click the Calibrate button; in the Display Calibration Assistant that appears, you have a gamma choice on the very first options screen.

See Chapter 4 for details on the Dock and its System Preferences pane.

The Energy Saver program helps you and your Mac in a number of ways. By blacking out the screen after a period of inactivity, it prolongs the life of your monitor. By putting the Mac to sleep half an hour after you’ve stopped using it, Energy Saver cuts down on electricity costs and pollution. On a laptop, Energy Saver extends the length of the battery charge by controlling the activity of the hard drive and screen.

Best of all, this pane offers the option to have your computer turn off each night automatically—and turn on again at a specified time in anticipation of your arrival at the desk.

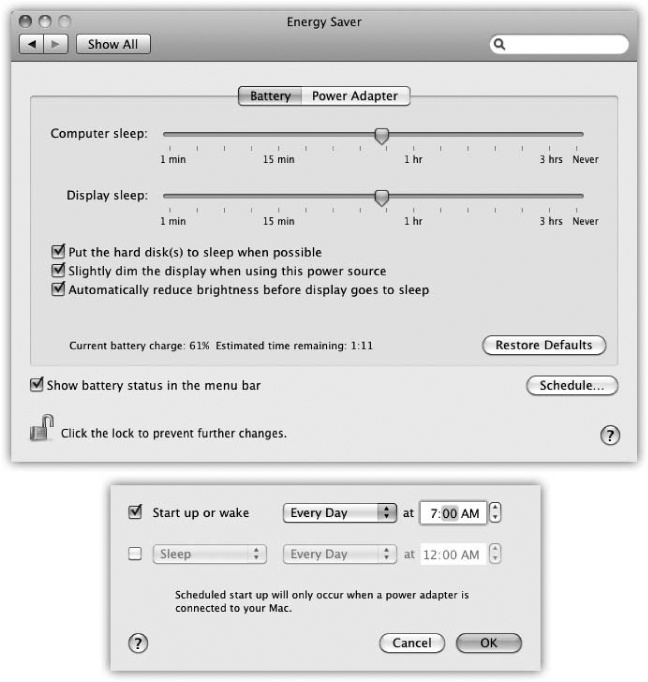

The Energy Saver controls are different on a laptop Mac and a desktop Mac, but both present a pair of sliders (Figure 9-11).

Figure 9-11. Top: Here’s what Energy Saver looks like on a laptop. In the “Put the display to sleep” option, you can specify an independent sleep time for the screen. Bottom: Here are the Schedule controls—a welcome return of the Mac’s self-scheduling abilities.

The top slider controls when the Mac will automatically go to sleep—anywhere from 1 minute after your last activity to Never. (Activity can be mouse movement, keyboard action, or Internet data transfer; Energy Saver won’t put your Mac to sleep in the middle of a download.)

At that time, the screen goes dark, the hard drive stops spinning, and your processor chip slows to a crawl. Your Mac is now in sleep mode, using only a fraction of its usual electricity consumption. To wake it up when you return to your desk, press any key. Everything you were working on, including open programs and documents, is still onscreen, exactly as it was. (To turn off this automatic sleep feature entirely, drag the slider to Never.)

The second slider controls when the screen goes black to save power. These days, there’s really only one good reason to put the screen to sleep independently of the Mac itself: so that your Mac can run its standard middle-of-the-night maintenance routines, even while the screen is off to save power.

Below the sliders, you see a selection of additional power-related options:

Put the hard disk(s) to sleep when possible. This saves even more juice—and noise—by letting your drives stop spinning when not in use. The downside is a longer pause when you return to work and wake the thing up, because it takes a few seconds for your hard drive to “spin up” again.

Wake for network access. This option lets you access a sleeping Mac from across the network. How is that possible? See the box on the next page.

Note

The wording of this option reflects how your Mac can connect to a network. If it can connect either over an Ethernet cable or a wireless hot spot, it says, “Wake for network access.” If it’s not a wireless Mac, you’ll see, “Wake for Ethernet network access.” If it’s a MacBook Air without an Ethernet adapter, it says, “Wake for AirPort network access.” On a laptop, the “wake” feature is available only when the machine’s lid is left open and you’re plugged into a power outlet.

Allow power button to put the computer to sleep. On desktop Macs, it can be handy to sleep the Mac just by tapping its

button.

button.Start up automatically after a power failure. This is a good option if you leave your Mac unattended and access it remotely, or if you use it as a network file server or Web server. It ensures that, if there’s even a momentary blackout that shuts down your Mac, it starts itself right back up again when the juice returns. (On a laptop, it’s available only when you’re adjusting Power Adapter mode.)

Slightly dim the display when using this power source. You see this checkbox only when you’re adjusting the settings for battery-power mode on a laptop. It means “Don’t use full brightness, so I can save power.”

Automatically reduce the brightness of the display before display sleep. When this option is on for your laptop, the screen doesn’t just go black suddenly after the designated period of inactivity; instead, it goes to half brightness as a sort of drowsy mode that lets you know full sleep is coming soon.

Show battery status in the menu bar. This on/off switch (laptops only) controls the battery menulet described in the box on the facing page.

Note

On a laptop, notice the two tabs at the top of the dialog box. They let you create different settings for the two states of life for a laptop, when it’s plugged in (Power Adapter) and when it’s running on battery power (Battery). That’s important, because on a laptop, every drop of battery power counts.

However, Snow Leopard no longer offers a choice of battery-power “profiles,” like Better Energy Savings and Better Performance. Simpler is better, right?

By clicking the Schedule button, you can set up the Mac to shut itself down and turn itself back on automatically (Figure 9-11, bottom).

If you work 9 to 5, for example, you can set the office Mac to turn itself on at 8:45 a.m. and shut itself down at 5:30 p.m.—an arrangement that conserves electricity, saves money, and reduces pollution, but doesn’t inconvenience you in the least. In fact, you may come to forget that you’ve set up the Mac this way, since you’ll never actually see it turn itself off.

Exposé and Spaces, the two ingenious window- and screen-management features of Mac OS X, are described in detail in Chapter 5—and so is this joint-venture control panel.

The changes you make on this panel are tiny but can have a cumulatively big impact on your daily typing routine. The options have been organized on two panes.

In Snow Leopard, Apple has continued its annual shuffling around of the controls for the keyboard, mouse, and trackpad (which, believe it or not, all used to be in a single System Preferences pane). On this pane, you have:

Key Repeat Rate, Delay Until Repeat. You’re probably too young to remember the antique once known as the typewriter. On some electric versions of this machine, you could hold down the letter X key to type a series of XXXXXXXs—ideal for crossing something out in a contract, for example.

On the Mac, every key behaves this way. Hold down any key long enough, and it starts spitting out repetitions, making it easy to type, for example, “No WAAAAAAAY!” or “You go, girrrrrrrrrl!” These two sliders govern this behavior. On the right: a slider that determines how long you must hold down the key before it starts repeating (to prevent triggering repetitions accidentally, in other words). On the left: a slider that governs how fast each key spits out letters once the spitting has begun.

Use all F1, F2, etc. keys as standard function keys. This option appears only on laptops and aluminum-keyboard Macs. It’s complicated, so read The Complicated Story of the Function Keys slowly.

Illuminate keyboard in low light conditions. This setting appears only if your Mac’s keyboard does, in fact, light up when you’re working in the dark—a showy feature of many Mac laptops. You can specify that you want the internal lighting to shut off after a period of inactivity (to save power when you’ve wandered away, for example), or you can turn the lighting off altogether. (You can always adjust the keyboard brightness manually, of course, by tapping the

and

and  keys.)

keys.)Show Keyboard & Character Viewer in menu bar. You can read all about these special symbol-generating windows on Formats Tab. For years, the on/off switch for these handy tools has been buried in the International pane of System Preferences; in Snow Leopard, there’s a duplicate on/off switch here, for your convenience.

Modifier Keys. This button lets you turn off, or remap, the functions of the Option, Caps Lock, Control, and ⌘ keys. It’s for Unix programmers whose pinkies can’t adjust to the Mac’s modifier-key layout—and for anyone who keeps hitting Caps Lock by accident during everyday typing.

This pane is new in Snow Leopard—and pretty neat. It lets you make up new keystrokes for just about any function on the Mac, from capturing a screenshot to operating the Dock, triggering one of the Services, or operating a menu in any program from the keyboard. You can come up with keyboard combinations that, for example, are easier to remember, harder to trigger by accident, or easier to hit with one hand.

Step-by-step instructions for using this pane appear on Control the Toolbar.

The primary job of this pane, formerly called International, is to set up your Mac to work in other languages. If you bought your Mac with a localized operating system—a version that already runs in your own language—and you’re already using the only language, number format, and keyboard layout you’ll ever need, then you can ignore most of this panel. But when it comes to showing off Mac OS X to your friends and loved ones, the “wow” factor on the Mac’s polyglot features is huge. Details appear on The Many Languages of Mac OS X Text.

This panel is of no value unless you’ve signed up for a MobileMe account. See Chapter 18 for details.

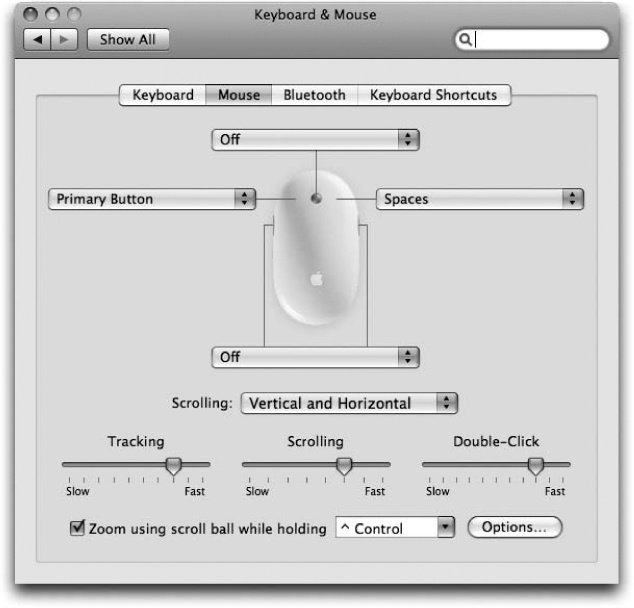

This pane, newly split apart from the Keyboard & Mouse panel that kicked around the Mac OS for decades, looks different depending on what kind of mouse (if any) is attached to your Mac.

It may surprise you that the cursor on the screen doesn’t move 5 inches when you move the mouse 5 inches on the desk. Instead, the cursor moves farther when you move the mouse faster.

Figure 9-12. This enormous photographic display shows up only if you have the Mighty Mouse, Apple’s “two-button” mouse. The pop-up menus let you program the right, left, and side buttons. They offer functions like opening Dashboard, triggering Exposé, and so on. This is also where you can turn the right-clicking feature on (just choose Secondary Button from the appropriate pop-up menu)—or swap the right- and left-click buttons’ functions.

How much farther depends on how you set the first slider here. The Fast setting is nice if you have an enormous monitor, since you don’t need an equally large mouse pad to get from one corner to another. The Slow setting, on the other hand, forces you to pick up and put down the mouse frequently as you scoot across the screen. It offers very little acceleration, but it can be great for highly detailed work like pixel-by-pixel editing in Photoshop.

The Double-Click Speed setting specifies how much time you have to complete a double-click. If you click too slowly—beyond the time you’ve allotted yourself with this slider—the Mac “hears” two single clicks instead.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: If you have a real mouse attached, you also see the magnificent “Zoom using scroll wheel while holding Control” checkbox at the bottom of this pane. What this means is that you can magnify the entire screen, zooming in, by turning the little ball or wheel atop your mouse while you press the Control key. It’s great for reading tiny type, examining photos up close, and so on.

If you have an Apple Mighty Mouse—the white mouse that has come with desktop Macs since 2005—then the Mouse pane is a much fancier affair (Figure 9-12).

On a laptop without any mouse attached, the Mouse pane still appears in System Preferences—but its sole function is to help you “pair” your Mac with a wireless Bluetooth mouse.

See Chapters Chapter 13 and Chapter 18 for the settings you need to plug in for networking.

These controls are described at length in Chapter 12.

Chapter 14 describes printing and faxing in detail. This panel offers a centralized list of the printers you’ve introduced to the Mac.

See Chapter 12 for details on locking up your Mac.

Mac OS X is an upstanding network citizen, flexible enough to share its contents with other Macs, Windows PCs, people dialing in from the road, and so on. On this panel, you’ll find on/off switches for each of these sharing channels.

In this book, many of these features are covered in other chapters. For example, Screen Sharing and File Sharing are in Chapter 13; Printer Sharing and Fax Sharing are in Chapter 14; Web Sharing and Remote Login are in Chapter 22; Internet Sharing is in Chapter 18.

Here’s a quick rundown on the other items:

DVD or CD Sharing. This feature was added to accommodate the MacBook Air laptop, which doesn’t have a built-in CD/DVD drive. When you turn on this option, any MacBook Airs on the network can “see,” and borrow, your Mac’s DVD drive, for the purposes of installing new software or running Mac disk-repair software. (Your drive shows up under the Remote Disc heading in the Air’s Sidebar.)

Remote Management. Lets someone else control your Mac using Apple Remote Desktop, a popular add-on program for teachers.

Remote Apple Events. Lets AppleScript gurus (Chapter 7) send commands to Macs across the network.

Xgrid Sharing. Xgrid is powerful software that lets you divide up a complex computational task—like computer animation or huge scientific calculations—among a whole bunch of Macs on your network, so that they automatically work on the problem when they’re otherwise sitting idle. If you’re intrigued, visit http://developer.apple.com/hardware/hpc/xgrid_intro.html.

Bluetooth Sharing. This pane lets you set up Bluetooth file sharing, a way for other people near you to shoot files over to (or receive files from) your laptop—without muss, fuss, or passwords. Via Flash Drive has the details.

Whenever Apple improves or fixes some piece of Mac OS X or some Apple-branded program, the Software Update program can notify you, download the update, and install it into your system automatically. These updates may include new versions of programs like iPhoto and iMovie; drivers for newly released printers, scanners, cameras, and such; bug fixes and security patches; and so on.

Software Update doesn’t download the new software without asking your permission first and explicitly telling you what it plans to install, as shown in Figure 9-13.

For maximum effortlessness, turn on the “Check for updates” checkbox and then select a frequency from the pop-up menu—daily, weekly, or monthly. If you also turn on “Download updates automatically,” you’ll still be notified before anything gets installed, but you won’t have to wait for the downloading—the deed will already be done.

(If you’ve had “Check for updates” turned off, you can always click the Check Now button to force Mac OS X to report in to see if new patches are available.)

Software Update also keeps a meticulous log of everything it drops into your system. On this tab, you see them listed, for your reference pleasure.

Figure 9-13. When Software Update finds an appropriate software morsel, it presents a simple message: “Software updates are available for your computer. Do you want to install them?” You could click install, if you’re the trusting short. But it’s informative to click Show Details instead. Doing so expands the box to what’s pictured here; you can click each proposed update and read about it.

Tip

In your Macintosh HD→Library→Receipts folder, you’ll find a liberal handful of .pkg files that have been downloaded by Software Update.

Most of these are nothing more than receipts that help Mac OS X understand which updaters you’ve already downloaded and installed. They make intriguing reading, but their primary practical use is finding out whether or not you’ve installed, for example, the 10.6.1 update.

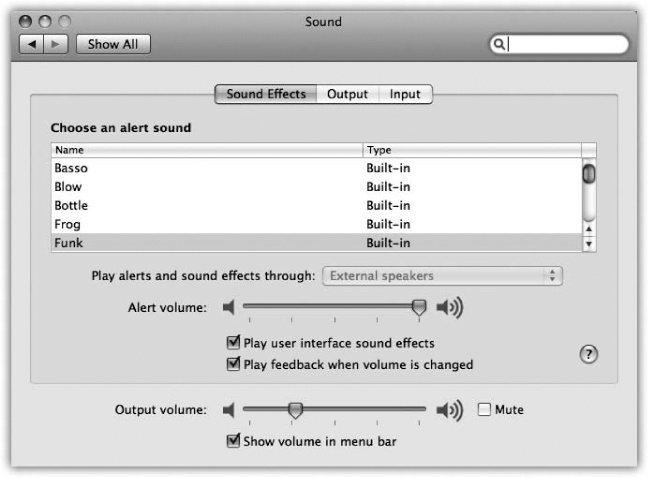

Using the panes of the Sound panel, you can configure the sound system of your Mac in any of several ways.

Tip

Here’s a quick way to jump directly to the Sound panel of System Preferences—from the keyboard, without ever having to open System Preferences or click Sound. Just press Option as you tap the  ,

,  or

or  key on the top row of your Apple keyboard.

key on the top row of your Apple keyboard.

“Sound effects” means error beeps—the sound you hear when the Mac wants your attention, or when you click someplace you shouldn’t.

Just click the sound of your choice to make it your default system beep. Most of the canned choices here are funny and clever, yet subdued enough to be of practical value as alert sounds (Figure 9-14). As for the other controls on the Sound Effects panel, they include these:

Alert volume slider. Some Mac fans are confused by the fact that even when they drag this slider all the way to the left, the sound from games and music CDs still plays at full volume.

The actual main volume slider for your Mac is the “Output volume” slider at the bottom of the Sound pane. The “Alert volume” slider is just for error beeps; Apple was kind enough to let you adjust the volume of these error beeps independently.

Play user interface sound effects. This option produces a few subtle sound effects during certain Finder operations: when you drag something off the Dock, into the Trash, or into a folder, or when the Finder finishes a file-copying job.

Play feedback when volume is changed. Each time you press one of the volume keys (

,

,  ,

,  ), the Mac beeps to help you gauge the current volume.

), the Mac beeps to help you gauge the current volume.That’s all fine when you’re working at home. But more than one person has been humiliated in an important meeting when the Mac made a sudden, inappropriately loud sonic outburst—and then amplified that embarrassment by furiously and repeatedly pressing the volume-down key, beeping all the way.

If you turn off this checkbox, the Mac won’t make any sound at all as you adjust its volume. Instead, you’ll see only a visual representation of the steadily decreasing (or increasing) volume level.

Play Front Row sound effects. You can read about Front Row, which turns your screen into a giant multimedia directory for your entire Mac, in Chapter 15. All this option does is silence the little clicks and whooshes that liven up the proceedings when you operate Front Row’s menus.

“Output” means speakers or headphones. For most people, this pane offers nothing useful except the Balance slider, with which you can set the balance between your Mac’s left and right stereo speakers. The “Select a device” wording seems to imply that you can choose which speakers you want to use for playback. But Internal Speakers is generally the only choice, even if you have external speakers. (The Mac uses your external speakers automatically when they’re plugged in.)

A visit to this pane is necessary, however, if you want to use USB speakers or a Bluetooth or USB phone headset. Choose its name from the list.

This panel lets you specify which sound source you want the Mac to “listen to,” if you have more than one connected: external microphone, internal microphone, line input, USB headset, or whatever. It also lets you adjust the sensitivity of that microphone—its input volume—by dragging the slider and watching the real-time Input level meter above it change as you speak. Put another way, it’s a quick way to see if your microphone is working.

The “Use ambient noise reduction” is great if you make podcasts or use dictation software. It turns any mike into what amounts to a noise-canceling microphone, deadening the background noise while you’re recording.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: Here’s a much quicker way to change your audio input or output: Press Option as you click the  menulet. You get a secret pop-up menu that lists your various microphones, speakers, and headphones, so you can switch things without a visit to System Preferences.

menulet. You get a secret pop-up menu that lists your various microphones, speakers, and headphones, so you can switch things without a visit to System Preferences.

If you’d prefer even more control over your Mac’s sound inputs and outputs, don’t miss the rewritten Audio/MIDI Setup program in your Applications→Utilities folder.

Your Mac’s ability to speak—and be spoken to—is described in juicy detail starting on Speech Recognition.

Here’s how you tell the Mac (a) which categories of files and information you want the Spotlight search feature to search, (b) which folders you don’t want searched, for privacy reasons, and (c) which key combination you want to use for summoning the Spotlight menu or dialog box. Details are in Chapter 3.

Use this panel to pick the System Folder your Mac will use the next time it starts up—when you’re swapping between Mac OS X and Windows (running with Boot Camp), for example. Check out the details in Chapter 8.

Here’s the master on/off switch and options panel for Time Machine, which is described in Chapter 6.

This panel, present only on laptops, keeps growing with each successive MacBook generation. (It’s shown in Figure 6-3 on page 225.)

At the top, you find duplicates of the same Tracking Speed and Double-Click Speed sliders described under Mouse earlier in this chapter—but these let you establish independent tracking and clicking speeds for the trackpad. (There’s even a new Scrolling slider, too, so you can control how fast the Mac scrolls a document when you drag two fingers down the trackpad.)

You may love your Mac laptop now, but wait until you find out about these special features. They make your laptop crazy better. It turns out you can point, click, scroll, right-click, rotate things, enlarge things, hide windows, and switch programs—all on the trackpad itself, without a mouse and without ever having to lift your fingers.

Apple keeps adding new “gestures” with each new laptop, so yours may not offer all these options. But here’s what you might see. (If you point to one of these items without clicking, a movie illustrates each of these maneuvers right on the screen.)

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: In Snow Leopard, all Mac laptops that have multi-touch trackpads can handle the three-finger and four-finger gestures described below. (For a while there, those gestures were available only on the latest models, the ones with no separate clicker button below the trackpad.)

Tap to Click. Usually, you touch your laptop’s trackpad only to move the cursor. For clicking and dragging, you’re supposed to use the clicking button beneath the trackpad (or, on the latest models, click the trackpad surface itself).

Many people find, however, that it’s more direct to tap and drag directly on the trackpad, using the same finger that’s been moving the cursor. That’s the purpose of this checkbox. When it’s on, you can tap the trackpad surface to register a mouse click at the location of the cursor. Double-tap to double-click.

Dragging. This option lets you move icons, highlight text, or pull down menus—in other words, to drag, not just click—using the trackpad.

Start by tapping twice on the trackpad, then immediately after the second tap, begin dragging your finger. (If you don’t start moving promptly, the laptop assumes that you were double-clicking.) You can stroke the trackpad repeatedly to continue your movement, as long as your finger never leaves the trackpad surface for more than about a second. When you “let go,” the drag is considered complete.

Drag Lock. If you worry that you’re going to “drop” what you’re dragging if you stop moving your finger, turn on this option instead. Once again, begin your drag by double-clicking, then move your finger immediately after the second click.

When this option is on, however, you can take your sweet time in continuing the movement. In between strokes of the trackpad, you can take your finger off the laptop for as long as you like. You can take a phone call, a shower, or a vacation; the Mac still thinks that you’re in the middle of a drag. Only when you tap again does the laptop consider the drag a done deal.

Scroll. This one is sweet. You have to try it to believe it. It means that dragging two fingers across your trackpad scrolls whatever window is open, just as though you had slid over to the scroll bar and clicked there. Except doing it with your two fingers, right in place, is infinitely faster and less fussy. You even get a Scrolling Speed slider.

Rotate. Place two fingers on the trackpad, and then twist them around an invisible center point, to rotate a photo or a PDF document. This doesn’t work in all programs or in all circumstances, but it’s great for turning images upright in the Finder, Preview, iPhoto, Image Capture, and so on.

Pinch Open & Close. If you’ve used an iPhone, this one will seem familiar. What it means is, “Put two fingers on the trackpad and spread them apart to enlarge what’s on the screen. Slide two fingers together to shrink it down again.” It doesn’t work in every program—it affects icons on the desktop, pictures in Preview and iPhoto, text in Safari, and so on—but it’s great when it does.

Screen zoom. Here’s another irresistible feature. It lets you zoom into the screen image, magnifying the whole thing, just by dragging two fingers up or down the trackpad while you’re pressing the Control key. You can zoom in so far that the word “zoom” in 12-point type fills the entire monitor.

This feature comes in handy with amazing frequency. It’s great for reading Web pages in tiny type, or enlarging Web movies, or studying the dot-by-dot construction of a button or icon that you admire. Just Control-drag upward to zoom in, and Control-drag downward to zoom out again.

You can click Options to customize this feature. For example, you can substitute the Option or ⌘ key, if Control isn’t working out for you. Furthermore, you can specify how you want to scroll around within your zoomed-in screen image. The factory setting, “Continuously with pointer,” is actually pretty frustrating; the whole screen shifts around whenever you move the cursor. (“So the pointer is at or near the center of the image” is very similar.) “Only when the pointer reaches an edge” is a lot less annoying, and lets you use the cursor (to click buttons, for example) without sending the entire screen image darting away from you.

Secondary click. This means “right-click.” Right-clicking is a huge deal on the Mac; it unleashes useful features just about everywhere.

On all Mac laptops, you can trigger a right-click by clicking with your thumb while resting your index and middle fingers on the trackpad.

On the latest laptops—the ones with no separate clicker button—there’s another option: a pop-up menu that lets you designate a certain trackpad corner (bottom right, for example) as the right-click spot. Clicking there triggers a right-click—to open a shortcut menu, for example. Weird, but wonderful.

Swipe to Navigate. Drag three fingers horizontally across the trackpad to skip to the next or previous page or image in a batch. Here again, this feature doesn’t work in all programs, but it’s great for flipping through images or PDF pages in Preview or iPhoto.

Swipe Up/Down for Exposé. A four-finger swipe up the trackpad triggers the “Show desktop” function of Exposé. A four-finger drag downward triggers the “Show all windows” function instead. Swipe the opposite direction to restore the windows.

Swipe Left/Right to Switch Applications. A four-finger swipe left or right makes the ⌘-Tab program switcher appear (The “Heads-Up” Program Switcher) so that you can point to a different program’s icon and switch to it with a click.

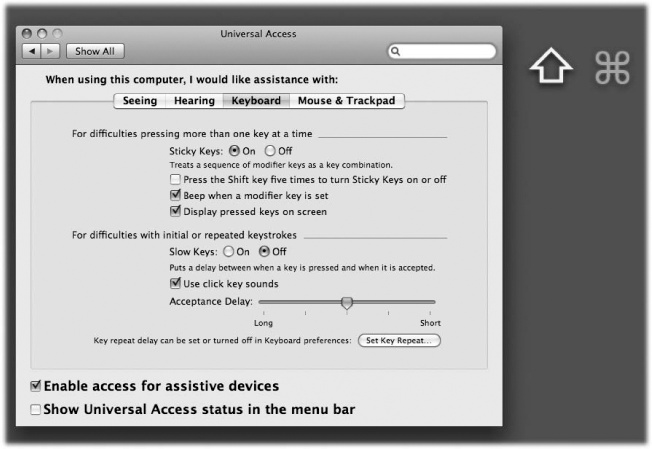

The Universal Access panel is designed for people who type with one hand, find it difficult to use a mouse, or have trouble seeing or hearing. (These features can also be handy when the mouse is broken or missing.)

Accessibility is a huge focus for Apple, and in Snow Leopard, there are more features than ever for disabled people, including compatibility with Braille screens (yes, there is such a thing). In fact, there’s a whole Apple Web site dedicated to explaining all these features: www.apple.com/macosx/accessibility.

Here, though, is an overview of the noteworthiest features.

If you have trouble seeing the screen, then boy, does Mac OS X have features for you (Figure 9-15).

One option is VoiceOver, which makes the Mac read out loud every bit of text that’s on the screen. The impressively enhanced Snow Leopard version of VoiceOver is described on VoiceOver.

Another quick solution is to reduce your monitor’s resolution—thus magnifying the image—using the Displays panel described earlier in this chapter. If you have a 17-inch or larger monitor set to, say, 640 x 480, the result is a greatly magnified picture. That method doesn’t give you much flexibility, however, and it’s a hassle to adjust.

If you agree, then try the Zoom feature that appears here; it lets you enlarge the area surrounding your cursor in any increment.

Tip

If you have a laptop, just using the Control-key trackpad trick described on Two Fingers is a far faster and easier way to magnify the screen. If you have a mouse, turning the wheel or trackpea while pressing Control is also much faster. Both of those features work even when this one is turned Off.

To make it work, press Option-⌘-8 as you’re working. Or, if the Seeing panel is open, click On in the Zoom section. That’s the master switch.

No zooming actually takes place, however, until you press Option-⌘-plus sign (to zoom in) or Option-⌘-minus sign (to zoom out). With each press, the entire screen image gets larger or smaller, creating a virtual monitor that follows your cursor around the screen.

While you’re at it, pressing Control-Option-⌘-8, or clicking the “Switch to Black on White” button, inverts the colors of the screen, so that text appears white on black—an effect that some people find easier to read. (This option also freaks out many Mac fans who turn it on by mistake, somehow pressing Control-Option-⌘-8 by accident during everyday work. They think the Mac’s expensive monitor has just gone loco. Now you know better.)

Figure 9-15. You’ll be amazed at just how much you can zoom into the Mac’s screen using this Universal Access pane. In fact, there’s nothing to stop you from zooming in so far that a single pixel fills the entire monitor. (That may not be especially useful for people with limited vision, but it can be handy for graphic designers learning how to reproduce a certain icon, dot by dot.)

Tip

There’s also a button called Use Grayscale, which banishes all color from your screen. This is another feature designed to improve text clarity, but it’s also a dandy way to see how a color document will look when printed on a monochrome laser printer.

No matter which color mode you choose, the “Enhance contrast” slider is another option that can help. It makes blacks blacker and whites whiter, further eliminating in-between shades and thereby making the screen easier to see. (If the Universal Access panel doesn’t happen to be open, you can always use the keystrokes Control-Option-⌘-< and Control-Option-⌘-> to decrease or increase contrast.)

If you have trouble hearing the Mac’s sounds, the obvious solution is to increase the volume, which is why this panel offers a direct link to the Sound preferences pane.

Fortunately, hearing your computer usually isn’t critical (except when working in music and audio, of course). The only time audio is especially important is when the Mac tries to get your attention by beeping. For those situations, turn on “Flash the screen when an alert sound occurs” (an effect you can try out by clicking the Flash Screen button). Now you’ll see a white flash across the entire monitor whenever the Mac would otherwise beep—not a bad idea on laptops, actually, so that you don’t miss beeps when you’ve got the speakers muted.

(The “Play stereo audio as mono” option is intended for people with hearing loss in one ear. This way, you won’t miss any of the musical mix just because you’re listening through only one headphone.)

This panel offers two clever features designed to help people who have trouble using the keyboard.

Sticky Keys lets you press multiple-key shortcuts (involving keys like Shift, Option, Control, and ⌘) one at a time instead of all together.

To make Sticky Keys work, first turn on the master switch at the top of the dialog box. Then go to work on the Mac, triggering keyboard commands as shown in Figure 9-16.

If you press a modifier key twice, meanwhile, you lock it down. (Its onscreen symbol gets brighter to let you know.) When a key is locked, you can use it for several commands in a row. For example, if a folder icon is highlighted, you could double-press ⌘ to lock it down—and then type O (to open the folder), look around, and then press W (to close the window). Press the ⌘ key a third time to “un-press” it.

Tip