Every computer offers a way to find files. And every system offers several different ways to open them. But Spotlight, a star feature of Mac OS X (and touched up in Snow Leopard), combines these two functions in a way that’s so fast, so efficient, so spectacular, it reduces much of what you’ve read in the previous chapters to irrelevance.

That may sound like breathless hype, but wait till you try it. You’ll see.

See the little magnifying-glass icon in your menu bar ( )? That’s the mouse-driven way to open the Spotlight Search box.

)? That’s the mouse-driven way to open the Spotlight Search box.

The other way is to press ⌘-space bar. If you can memorize only one keystroke on your Mac, that’s the one to learn. It works both at the desktop and in other programs.

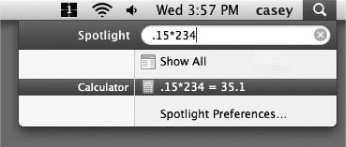

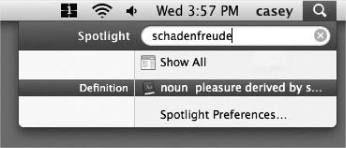

In any case, the Spotlight text box appears just below your menu bar (Figure 3-1).

Begin typing to identify what you want to find and open. For example, if you’re trying to find a file called Pokémon Fantasy League.doc, typing just pok or leag would probably suffice. (The Search box doesn’t find text in the middles of words, though; it searches from the beginnings of words.)

A menu immediately appears below the Search box, listing everything Spotlight can find containing what you’ve typed so far. (This is a live, interactive search; that is, Spotlight modifies the menu of search results as you type.) The menu lists every file, folder, program, email message, Address Book entry, calendar appointment, picture, movie, PDF document, music file, Web bookmark, Microsoft Office (Word, Power-Point, Excel, Entourage) document, System Preferences panel, To Do item, chat transcript, Web site in your History list, and even font that contains what you typed, regardless of its name or folder location.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: In fact, Spotlight in Snow Leopard recognizes a couple of new data types. It now finds photos according to who is in them (using iPhoto’s Faces feature) or where they were taken (using iPhoto’s Places feature). If you use iChat (Chapter 21), Spotlight also finds the lucky members of your Buddy lists.

Figure 3-1. Left: Press ⌘-space bar, or click the magnifying-glass icon, to make the Search box appear. Right: As you type, Spotlight builds the list of every match it can find, neatly organized by type: programs, documents, folders, images, PDF documents, and so on.

If you see the icon you were hoping to dig up, just click it to open it. Or use the arrow keys to “walk down” the menu, and then press Return or Enter to open the one you want.

If you click an application, it pops onto the screen. If you select a System Preferences panel, System Preferences opens and presents that panel. If you choose an appointment, the iCal program opens, already set to the appropriate day and time. Selecting an email message opens that message in Mail or Entourage. And so on.

Spotlight is so fast, it eliminates a lot of the folders-in-folders business that’s a side effect of modern computing. Why burrow around in folders when you can open any file or program with a couple of keystrokes?

It should be no surprise that a feature as important as Spotlight comes loaded with options, tips, and tricks. Here it is—the official, unexpurgated Spotlight Tip-O-Rama:

If the very first item—labeled Top Hit—is the icon you were looking for, just press Return or Enter to open it.

This is a huge deal, because it means that in most cases, you can perform the entire operation without ever taking your hands off the keyboard.

To open Safari in a hurry, for example, press ⌘-space bar (to open the Spotlight Search box), type safa, and hit Return, all in rapid-fire sequence, without even looking. Presto: Safari is before you.

(The only wrinkle here is that the Spotlight menu may still be building itself. If you go too quickly, you may be surprised as another entry jumps into the top slot just as you’re about to hit Return—and you wind up opening the wrong thing. Over time, you develop a feel for when the Top Hit is reliably the one you want.)

And what, exactly, is the Top Hit? Mac OS X chooses it based on its relevance (the importance of your search term inside that item) and timeliness (when you last opened it).

Tip

Spotlight makes a spectacular application launcher. That’s because Job One for Spotlight is to display the names of matching programs in the results menu. Their names appear in the list nearly instantly—long before Spotlight has built the rest of the menu of search results.

If some program on your hard drive doesn’t have a Dock icon, for example—or even if it does—there’s no faster way to open it than to use Spotlight.

To jump to a search result’s Finder icon instead of opening it, ⌘-click its name.

Spotlight’s menu shows you only 20 of the most likely suspects, evenly divided among the categories (Documents, Applications, and so on). The downside: To see the complete list, you have to open the Spotlight window (Opening the Spotlight Window Directly).

The upside: It’s fairly easy to open something in this menu from the keyboard. Just press ⌘-↓ (or ⌘-↑) to jump from category to category. Once you’ve highlighted the first result in a category, you can walk through the remaining four by pressing the arrow key by itself. Then, once you’ve highlighted what you want, press Return or Enter to open it.

In other words, you can get to anything in the Spotlight menu with only a few keystrokes.

The Esc key (top-left corner of your keyboard) offers a two-stage “back out of this” method. Tap it once to close the Spotlight menu and erase what you’ve typed, so that you’re all ready to type in something different. Tap Esc a second time to close the Spotlight text box entirely, having given up on the whole idea of searching.

(If you just want to cancel the whole thing in one step, press ⌘-space bar again, or ⌘-period, or ⌘-Esc.)

Think of Spotlight as your little black book. When you need to look up a number in Address Book, don’t bother opening Address Book; it’s faster to use Spotlight. You can type somebody’s name or even part of someone’s phone number.

Among a million other things, Spotlight tracks the keywords, descriptions, faces, and places you’ve applied to your pictures in iPhoto. As a result, you can find, open, or insert any iPhoto photo at any time, no matter what program you’re using, just by using the Spotlight box at the top of every Open File dialog box (The File Format Pop-up Menu)! This is a great way to insert a photo into an outgoing email message, a presentation, or a Web page you’re designing. iPhoto doesn’t even have to be running.

Spotlight is also a quick way to adjust one of your Mac’s preference settings. Instead of opening up the System Preferences program, type the first few letters of, say, volume or network or clock into Spotlight. The Spotlight menu lists the appropriate System Preferences panel, so you can jump directly to it.

If you point to an item in the Spotlight menu without clicking, a little tooltip balloon appears. It tells you the item’s actual name—which is useful if Spotlight listed something because of text that appears inside the file, not its name—and its folder path (that is, where it is on your hard drive).

The Spotlight menu lists 20 found items. In the following pages, you’ll learn about how to see the rest of the stuff. But for now, note that you can eliminate some of the categories that show up here (like PDF documents or Bookmarks), and even rearrange them, to permit more of the other kinds of things to enjoy those 20 seats of honor. Details on Customizing Spotlight.

Spotlight shows you only the matches from your account and the public areas of the Mac (like the System, Application, and Developer folders)—but not what’s in anyone else’s Home folder. If you were hoping to search your spouse’s email for phrases like “meet you at midnight,” forget it.

If Spotlight finds a different version of something on each of two hard drives, it lets you know by displaying a faint gray hard drive name after each such item in the menu.

Spotlight works by storing an index, a private, multimegabyte Dewey Decimal System, on each hard drive, disk partition, or USB flash (memory) drive. If you have some oddball type of disk, like a hard drive that’s been formatted for Windows, Spotlight doesn’t ordinarily index it—but you can turn on indexing by using the File→Get Info command on that drive’s icon.

If you point to something in the results list without clicking, you can press ⌘-I to open the Get Info window for that item.

Most people just type the words they’re looking for into the Spotlight box. But if that’s all you type, you’re missing a lot of the fun.

If you type more than one word, Spotlight works just the way Google does. That is, it finds things that contain both words somewhere inside.

But if you’re searching for a phrase where the words really belong together, put quotes around them. You’ll save yourself from having to wade through hundreds of results where the words appear separately.

For example, searching for military intelligence rounds up documents that contain those two words, but not necessarily side by side. Searching for “military intelligence” finds documents that contain that exact phrase. (Insert your own political joke here.)

You can confine your search to certain categories using a simple code. For example, to find all photos, type kind:image. If you’re looking for a presentation document but you’re not sure whether you used Keynote, iWork, or PowerPoint to create it, type kind:presentation into the box. And so on.

Here’s the complete list of kinds. Remember to precede each keyword type with kind and a colon.

To find this: | Use one of these keywords: |

|---|---|

A program | app, application, applications |

Someone in your Address Book | contact, contacts |

A folder or disk | folder, folders |

A message in Mail | email, emails, mail message, mail messages |

An iCal appointment | event, events |

An iCal task | to do, to dos, todo, todos |

A graphic | image, images |

A movie | movie, movies |

A music file | music |

An audio file | audio |

A PDF file | pdf, pdfs |

A System Preferences control | preferences, system preferences |

A Safari bookmark | bookmark, bookmarks |

A font | font, fonts |

A presentation (PowerPoint, iWork) | presentation, presentations |

You can combine these codes with the text you’re seeking, too. For example, if you’re pretty sure you had a photo called “Naked Mole-Rat,” you could cut directly to it by typing mole kind:images or kind:images mole. (The order doesn’t matter.)

You can use a similar code to restrict the search by chronology. If you type date:yesterday, then Spotlight limits its hunt to items you last opened yesterday.

Here’s the complete list of date keywords you can use: this year, this month, this week, yesterday, today, tomorrow, next week, next month, next year. (The last four items are useful only for finding upcoming iCal appointments. Even Spotlight can’t show you files you haven’t created yet.)

If your brain is already on the verge of exploding, now might be a good time to take a break.

In Mac OS X 10.4, Spotlight could search on either of the criteria described above: kind or date.

But these days, you can limit Spotlight searches by any of the 125 different info-morsels that might be stored as part of the files on your Mac: author, audio bit rate, city, composer, camera model, pixel width, and so on. Other has a complete discussion of these so-called metadata types. (Metadata means “data about the data”—that is, descriptive info-bites about the files themselves.) Here are a few examples:

author:casey. Finds all documents with “casey” in the Author field. (This presumes that you’ve actually entered the name Casey into the document’s Author box. Microsoft Word, for example, has a place to store this information.)

width:800. Finds all graphics that are 800 pixels wide.

flash:1. Finds all photos that were taken with the camera’s flash on. (To find photos with the flash off, you’d type flash:0. A number of the yes/no criteria work this way: Use 1 for yes, 0 for no.)

modified:3/7/10-3/10/10. Finds all documents modified between March 7 and March 10, 2010.

You can also type created:6/1/10 to find all the files you created on June 1, 2010. Type modified:<=3/9/10 to find all documents you edited on or before March 9, 2010.

As you can see, three range-finding symbols are available for your queries: <, >, and -. The < means “before” or “less than”; the > means “after” or “greater than”; and the hyphen indicates a range (of dates, sizes, or whatever you’re looking for).

Tip

Here again, you can string words together. To find all PDFs you opened today, use date:today kind:PDF. And if you’re looking for a PDF document that you created on July 4, 2010, containing the word wombat, you can type created:7/4/10 kind:pdf wombat—although at this point, you’re not saving all that much time.

Now, those examples are just a few representative searches out of the dozens that Mac OS X makes available.

It turns out that the search criteria codes that you can type into the Spotlight box (author:casey, width:800, and so on) correspond to the master list that appears when you choose Other in the Spotlight window, as described on The Spotlight Window. In other words, there are 125 different search criteria.

There’s only one confusing part: In the Other list, lots of metadata types have spaces in their names. Pixel width, musical genre, phone number, and so on.

Yet you’re allowed to use only one word before the colon when you type a search into the Spotlight box. For example, even though pixel width is a metadata type, you have to use width: or pixelwidth: in your search.

So it would probably be helpful to have a master list of the one-word codes that Spotlight recognizes—the shorthand versions of the criteria described on Other.

Here it is, a Missing Manual exclusive, deep from within the bowels of Apple’s Spotlight department: the master list of one-word codes. (Note that some search criteria have several alternate one-word names.)

Real Search Attribute | One-Word Name(s) |

|---|---|

Keywords | keyword |

Title | title |

Subject | subject, title |

Theme | theme |

Authors | author, from, with, by |

Editors | editor |

Projects | project |

Where from | wherefrom |

Comment | comment |

Copyright | copyright |

Producer | producer |

Used dates | used, date |

Last opened | lastused, date |

Content created | contentcreated, created, date |

Content modified | contentmodified, modified, date |

Duration | duration, time |

Item creation | itemcreated, created, date |

Contact keywords | contactkeyword, keyword |

Version | version |

Pixel height | pixelheight, height |

Pixel width | pixelwidth, width |

Page height | pageheight |

Page width | pagewidth |

Color space | colorspace |

Bits per sample | bitspersample, bps |

Flash | flash |

Focal length | focallength |

Alpha channel | alpha |

Device make (camera brand) | make |

Device model (camera model) | model |

ISO speed | iso |

Orientation | orientation |

Layers | layer |

White balance | whitebalance |

Aperture | aperture, fstop |

Profile name | profile |

Resolution width | widthdpi, dpi |

Resolution height | heightdpi, dpi |

Exposure mode | exposuremode |

Exposure time | exposuretime, time |

EXIF version | exifversion |

Codecs | codec |

Media types | mediatype |

Streamable | streamable |

Total bit rate | totalbitrate, bitrate |

Video bit rate | videobitrate, bitrate |

Audio bit rate | audiobitrate, bitrate |

Delivery type | delivery |

Altitude | altitude |

Latitude | latitude |

Longitude | longitude |

Text content | intext |

Display name | displayname, name |

Red eye | redeye |

Metering mode | meteringmode |

Max aperture | maxaperture |

FNumber | fnumber, fstop |

Exposure program | exposureprogram |

Exposure time | exposuretime, time |

Headline | headline, title |

Instructions | instructions |

City | city |

State or province | state, province |

Country | country |

Album | album, title |

Sample rate | audiosamplerate, samplerate |

Channel count | channels |

Tempo | tempo |

Key signature | keysignature, key |

Time signature | timesignature |

Audio encoding application | audioencodingapplication |

Composer | composer, author, by |

Lyricist | lyricist, author, by |

Track number | tracknumber |

Recording date | recordingdate, date |

Musical genre | musicalgenre, genre |

General MIDI sequence | ismidi |

Recipients | recipient, to, with |

Year recorded | yearrecorded, year |

Organizations | organization |

Languages | language |

Rights | rights |

Publishers | publisher |

Contributors | contributor, by, author, with |

Coverage | coverage |

Description | description, comment |

Identifier | id |

Audiences | audience, to |

Pages | pages |

Security method | securitymethod |

Content Creator | creator |

Due date | duedate, date |

Encoding software | encodingapplication |

Rating | starrating |

Phone number | phonenumber |

Email addresses | |

Instant message addresses | imname |

Kind | kind |

URL | url |

Recipient email addresses | |

Email addresses | |

Filename | filename |

File pathname | path |

Size | size |

Created | created |

Modified | modified |

Owner | owner |

Group | group |

Stationery | stationery |

File invisible | invisible |

File label | label |

spotlightcomment, comment | |

Fonts | font |

Instrument category | instrumentcategory |

Instrument name | instrumentname |

What comp sci professors call Boolean searches are terms that round up results containing either of two search terms, both search terms, or one term but not another.

To go Boolean, you’re supposed to incorporate terms like AND, OR, or NOT into your search queries.

For example, you can round up a list of files that match two terms by typing, say, vacation AND kids. (That’s also how you’d find documents coauthored by two people—you and a pal, for example. You’d search for author:Casey AND author:Chris. Yes, you have to type Boolean terms in all capitals.)

Tip

You can use parentheses instead of AND, if you like. That is, typing (vacation kids) finds documents that contain both words, not necessarily together. But the truth is, Spotlight runs an AND search whenever you type two terms, like vacation kids—neither parentheses nor AND is required.

If you use OR, you can find items that match either of two search criteria. Typing kind:jpeg OR kind:pdf turns up photos and PDF files in a single list.

The minus sign (hyphen) works, too. If you did a search for dolphins, hoping to turn up sea-mammal documents, but instead find your results contaminated by football-team listings, by all means repeat the search with dolphins -miami. Mac OS X eliminates all documents containing “Miami.”

As you may have noticed, the Spotlight menu doesn’t list every match on your hard drive. Unless you own one of those extremely rare 60-inch Apple Skyscraper Displays, there just isn’t room.

Instead, Spotlight uses some fancy behind-the-scenes analysis to calculate and display the 20 most likely matches for what you typed. But at the top of the menu, you usually see that there are many other possible matches; it says something like “Show All,” meaning that there are other candidates. (Mac OS X no longer tells you how many other results there are.)

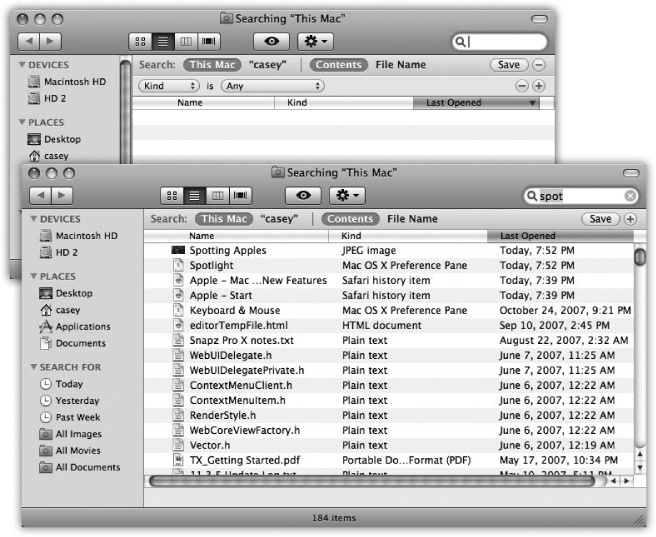

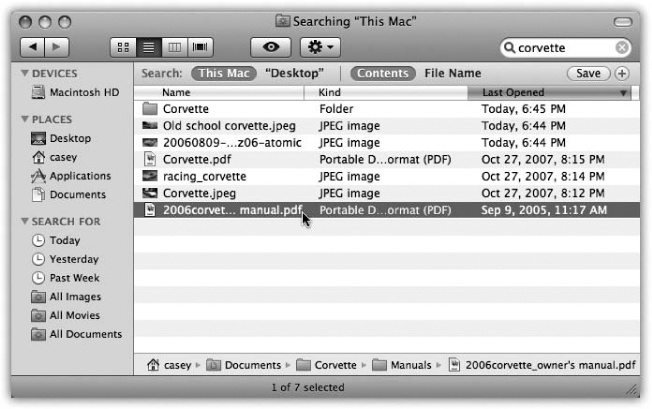

There is, however, a second, more powerful way into the Spotlight labyrinth. And that’s to use the Spotlight window, shown in Figure 3-2.

If the Spotlight menu—its Most Likely to Succeed list—doesn’t include what you’re looking for, then click Show All. You’ve just opened the Spotlight window.

Now you have access to the complete list of matches, neatly listed in what appears to be a standard Finder window.

When you’re in the Finder, you can also open the Spotlight window directly, without using the Spotlight menu as a trigger. Actually, there are three ways to get there (Figure 3-2):

⌘-F (for Find, get it?). When you choose File→Find (or press ⌘-F), you get an empty Spotlight window, ready to fill in for your search.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: When the Find window opens, what folder does it intend to search?

Until Snow Leopard came along, the answer was always: “Your whole Mac.” Which was a pain. Most of the time, what you wanted to search was the folder you were in. So you had to take an extra second to click that folder’s name at the top of the Find window.

In Snow Leopard, you’re saved that step. Choose Finder→Preferences→Advanced. From the “When performing a search” pop-up menu, you can choose Search This Mac, Search the Current Folder (usually what you want), or Use the Previous Search Scope (that is, either “the whole Mac” or “the current folder,” whichever you set up last time).

Option-⌘-space bar. This keystroke opens the same window. But it always comes set to search everything on your Mac (except other people’s Home folders, of course), regardless of the setting you made in Preferences (as described in the previous paragraphs).

Open any desktop window, and type something into the Search box at upper right. Presto—the mild-mannered folder window turns into the Spotlight window, complete with search results.

Tip

You can change the Find keystrokes to just about anything you like. See Control the Toolbar.

When the Searching window opens, you can start typing whatever you’re looking for into the Search box at the upper right.

As you type, the window fills with a list of the files and folders whose names contain what you typed. It’s just like the Spotlight menu, but without the 20-item results limit (Figure 3-2).

While the searching is going on, a sprocket icon whirls away in the lower-right corner. To cancel the search and clear the box (so you can try a different search), click the  button next to the phrase you typed. Or just hit the Esc key.

button next to the phrase you typed. Or just hit the Esc key.

The real beauty of the Searching window, though, is that it can hunt down icons using extremely specific criteria; it’s much more powerful (and complex) than the Spotlight menu. If you spent enough time setting up the search, you could use this feature to find a document whose name begins with the letters Cro, is over a megabyte in size, was created after 10/1/09 but before the end of the year, was changed within the past week, has the file name suffix .doc, and contains the phrase “attitude adjustment.” (Of course, if you knew that much about a file, you’d probably know where it is without having to use the Searching window. But you get the picture.)

To use the Searching window, you need to feed it two pieces of information: where you want it to search, and what to look for. You can make these criteria as simple or as complex as you like.

The three phrases at the top of the window—This Mac, “Folder Name,” and Shared—are buttons. Click one to tell Spotlight where to search:

This Mac means your entire computer, including secondary disks attached to it (or installed inside)—minus other people’s files, of course.

“Letters to Congress” (or whatever the current window is) limits the search to whatever window was open. So if you want to search your Pictures folder, open it first and then hit ⌘-F. You’ll see the Pictures button at the top of the window, and you can click it to restrict the search to that folder.

Shared. Click this button to expand the search to your entire network and all the computers on it. (This assumes, of course, that you’ve brought their icons to your screen as described in Chapter 13.)

If the other computers are Macs running Leopard or Snow Leopard, Spotlight can search their files just the way it does on your own Mac—finding words inside the files, for example. If they’re any other kind of computer, Spotlight can search for files only by name.

The two other buttons at the top of the Spotlight window are also very powerful:

Contents. This button, the factory setting, searches for the words inside your files, along with all the metadata attached to them.

File Name. There’s no denying that sometimes you already know a file’s name—you just don’t know where it is. In this case, it’s far faster to search by name, just as people did before Spotlight came along. The list of results is far shorter, and you’ll spot what you want much faster. That’s why this button is so welcome.

If all you want to do is search your entire computer for files containing certain text, you might as well use the Spotlight menu described at the beginning of this chapter.

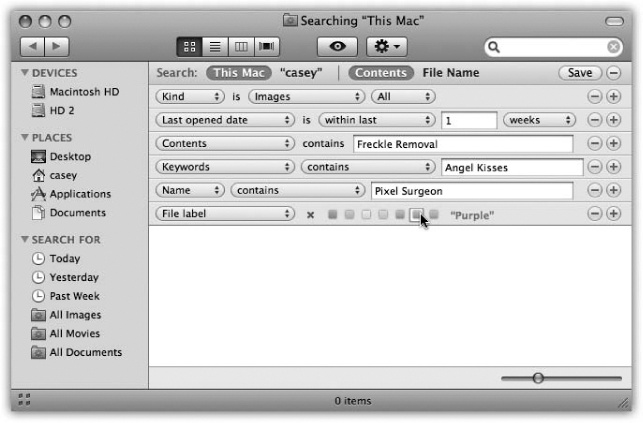

The power of the Spotlight window, though, is that it lets you design much more specific searches, using over 125 different search criteria: date modified, file size, the “last opened” date, color label, copyright holder’s name, shutter speed (of a digital photo), tempo (of a music file), and so on. Figure 3-3 illustrates how detailed this kind of search can be.

Figure 3-3. By repeatedly clicking the  button, you can turn on as many criteria as you’d like; each additional row further narrows the search.

button, you can turn on as many criteria as you’d like; each additional row further narrows the search.

To set up a complex search like this, use the second row of controls at the top of the window.

And third, and fourth, and fifth. Each time you click one of the  buttons at the right end of the window, a new criterion row appears; use its pop-up menus to specify what date, what file size, and so on. Figure 3-3 shows how you might build, for example, a search for all photo files that you’ve opened within the last week that contain a Photoshop layer named Freckle Removal.

buttons at the right end of the window, a new criterion row appears; use its pop-up menus to specify what date, what file size, and so on. Figure 3-3 shows how you might build, for example, a search for all photo files that you’ve opened within the last week that contain a Photoshop layer named Freckle Removal.

To delete a row, click the  button at its right end.

button at its right end.

Tip

If you press Option, the  button changes into a … button. When you click it, you get sub-rows of parameters for a single criterion. And a pop-up menu that says Any, All, or None appears at the top, so that you can build what are called exclusionary searches.

button changes into a … button. When you click it, you get sub-rows of parameters for a single criterion. And a pop-up menu that says Any, All, or None appears at the top, so that you can build what are called exclusionary searches.

The idea here is that you can set up a search for documents created between November 1 and 7 or documents created November 10 through 14. Or files named Complaint that are also either Word or InDesign files.

The mind boggles.

Here’s a rundown of the ways you can restrict your search, according to the options in the first pop-up menu of a row. Note that after you choose from that first pop-up menu (Last Opened, for example), you’re supposed to use the additional pop-up menus to narrow the choice (“within last,” “2,” and “weeks,” for example), as you’ll read below.

Note

It may surprise you that choosing something from the Kind pop-up menu triggers the search instantly. As soon as you choose Applications, for example, the window fills with a list of every program on your hard drive. Want a quick list of every folder on your entire machine? Choose Folders. (Want to see which folders you’ve opened in the past couple of days? Add another row.)

If you also type something into the Search box at the very top of the window—before or after you’ve used one of these pop-up menus—the list pares itself down to items that match what you’ve typed.

When the first pop-up menu says Kind, you can use the second pop-up menu to indicate what kind of file you’re looking for: Applications, Documents, Folders, Images, Movies, Music, PDF files, Presentations, Text files, or Other.

For example, when you’re trying to free up some space on your drive, you could round up all your movie files, which tend to be huge. Choosing one of these file types makes the window begin to fill with matches automatically and instantly.

And what if the item you’re looking for isn’t among those nine canned choices? What if it’s an alias, or a Photoshop plug-in, or some other type?

That’s what the Other option is all about. Here, you can type in almost anything that specifies a kind of file: Word, Excel, TIFF, JPEG, AAC, final cut, iMovie, alias, zip, html, or whatever.

When you choose one of these options from the first pop-up menu, the second popup menu lets you isolate files, programs, and folders according to the last time you opened them, the last time you changed them, or when they were created.

Today, yesterday, this week, this month, this year. This second pop-up menu offers quick, canned time-limiting options.

Within last, exactly, before, after. These let you be more precise. If you choose before, after, or exactly, then your criterion row sprouts a month/day/year control that lets you round up items that you last opened or changed before, after, or on a specific day, like 5/27/10. If you choose “within last,” then you can limit the search to things you’ve opened or changed within a specified number of days, weeks, months, or years.

These are awesomely useful controls, because they let you specify a chronological window for whatever you’re looking for.

Tip

You’re allowed to add two Date rows—a great trick that lets you round up files that you created or edited between two dates. Set up the first Date row to say “is after,” and the second one to say “is before.”

In fact, if it doesn’t hurt your brain to think about it, how about this? You can even have more than two Date rows. Use one pair to specify a range of dates for the file’s creation date and two other rows to limit when it was modified.

Science!

Spotlight likes to find text anywhere in your files, no matter what their names are. But when you want to search for an icon by the text that’s in only its name, this is your ticket. (Capitalization doesn’t matter.)

Wouldn’t it be faster just to click the File Name button at the top of the window? Yes—but using the Search window offers you far more control, thanks to the second pop-up menu that offers you these options:

Contains. The position of the letters you type doesn’t matter. If you type then, you find files with names like “Then and Now,” “Authentic Cajun Recipes,” and “Lovable Heathen.”

Starts with. The Find program finds only files beginning with the letters you type. If you type then, you find “Then and Now,” but not “Authentic Cajun Recipes” or “Lovable Heathen.”

Ends with. If you type then, you find “Lovable Heathen,” but not files called “Then and Now” or “Authentic Cajun Recipes.”

Is. This option finds only files named precisely what you type (except that capitalization still doesn’t matter). Typing then won’t find any of the file names in the previous examples. It would unearth only a file called simply “Then.” In fact, a file with a file name suffix, like “Then.doc,” doesn’t even qualify.

(If this happens to you, though, here’s a workaround: From the first pop-up menu, choose Other; in the dialog box, pick Filename. The Filename criterion ignores extensions; it would find “Then.doc” even if you searched for “then.”)

You can think of this option as the opposite of Name. It finds only the text that’s inside your files, and completely ignores their icon names.

That’s a handy function when, for example, a document’s name doesn’t match its contents. Maybe a marauding toddler pressed the keys while playing Kid Pix, renaming your doctoral thesis “xggrjpO#$5%////.” Or maybe you just can’t remember what you called something.

If this were a math equation, it might look like this: options x options = overwhelming.

Choosing Other from the first pop-up menu opens a special dialog box containing at least 125 other criteria. Not just the big kahunas like Name, Size, and Kind, but far more targeted (and obscure) criteria like “Bits per sample” (so you can round up MP3 music files of a certain quality), “Device make” (so you can round up all digital photos taken with, say, a Canon Rebel camera), “Key signature” (so you can find all the GarageBand songs you wrote in the key of F sharp), “Pages” (so you can find all Word documents that are really long), and so on. As you can see in Figure 3-4, each one comes with a short description.

You may think Spotlight is offering you a staggering array of file-type criteria. In fact, though, big bunches of information categories (technically called metadata) are all hooks for a relatively small number of document types. For example:

Figure 3-4. Here’s the master list of search criteria. Turn on the “In menu” checkboxes of the ones you’ll want to reuse often, as described in the box on page 108. Once you’ve added some of these search criteria to the menu, you’ll get an appropriate set of “find what?” controls (“Greater than” and “Less than” pop-up menus, for example).

Digital photos and other graphics files account for the metadata types alpha channel, aperture, color space, device make, device model, EXIF version, exposure mode, exposure program, exposure time, flash, FNumber, focal length, ISO speed, max aperture, metering mode, orientation, pixel height, pixel width, redeye, resolution height, resolution width, and white balance.

Digital music files have searchable metadata categories like album, audio bit rate, bits per sample, channel count, composer, duration, General MIDI sequence, key signature, lyricist, musical genre, recording date, sample rate, tempo, time signature, track number, and year recorded. There’s even a special set of parameters for GarageBand and Soundtrack documents, including instrument category, instrument name, loop descriptors, loop file type, loop original key, and loop scale type.

Microsoft Office documents can contain info bits like authors, contributors, fonts, languages, pages, publishers, and contact information (name, phone number, and so on).

This massive list also harbors a few criteria you may use more often, like Size, Label, and Visibility (which lets you see all the invisible files on your hard drive). See the box on Feeding the Barren Pop-up Menus.

Now, you could argue that in the time it takes you to set up a search for such a specific kind of data, you could have just rooted through your files and found what you wanted manually. But hey—you never know. Someday, you may remember nothing about a photo you’re looking for except that you used the flash and an f-stop of 1.8.

Tip

Don’t miss the Search box in this dialog box. It makes it super-easy to pluck one useful criterion needle—Size, say—out of the haystack. Also don’t forget about the “In menu” checkbox in the right column. It lets you add one of these criteria to the main pop-up menu, so you don’t have to go burrowing into Other again the next time.

In Snow Leopard, more than ever, the results window is a regular old Finder window, with all the familiar views and controls (Figure 3-5).

Figure 3-5. Click a result once to see where it sits on your hard drive (bottom). If the window is too narrow to reveal the full folder path, run your cursor over the folders without clicking. As your mouse moves from one folder to another, Leopard briefly reveals its name, compressing other folders as necessary to make room. (Sub-tip: You can drag icons into these folders, too.)

You can work with anything in the results window exactly as though it’s a regular Finder window: Drag something to the Trash, rename something, drag something to the desktop to move it there, drag something onto a Dock icon to open it with a certain program, Option-⌘-drag it to the desktop to create an alias, and so on.

You can move up or down the list by pressing the arrow keys, scroll a “page” at a time with the Page Up and Page Down keys, and so on. You can also highlight multiple icons simultaneously, the same way you would in a Finder list view: Highlight all of them by choosing Edit→Select All; highlight individual items by ⌘-clicking them; drag diagonally to enclose a cluster of found items; and so on.

Or you can proceed in any of these ways:

Change the view by clicking one of the View icons or choosing from the View menu. You can switch among icon, list, or Cover Flow views (see Chapter 1). Actually, Cover Flow is a great view for search results; since this list is culled from folders all over the computer, you otherwise have very little sense of context as you examine the file names.

Note

Column view isn’t available here, since the displayed search results are collected from all over your computer. They don’t all reside in the same folder. Still, Apple’s given you a consolation prize: the folder path display at the bottom of the window. It tells you where the selected item is hiding on your hard drive just as clearly as column view would have.

Sort the results by clicking the column headings. It can be especially useful to sort by Kind, so that similar file types are clustered together (Documents, Images, Messages, and so on), or by Last Opened, so that the list is chronological.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: For the first time, you can sort the search results even in icon view. True, there are no column headings to click—but you can use the

menu to choose “Keep Arranged by” [whatever criterion you like]. Snow Leopard will remember this sort order the next time you do an icon-view search.

menu to choose “Keep Arranged by” [whatever criterion you like]. Snow Leopard will remember this sort order the next time you do an icon-view search.Change the view options. Press ⌘-J (or choose View→Show View Options) to open the View Options panel for the results window. Here, you can add a couple of additional columns (Date Modified, Date Created); change the icon size or text size; or turn on the “always” checkbox at the top, so that future results windows will have the look you’ve set up here.

Get a Quick Look at one result by clicking it and then hitting the space bar. You get the big, bold, full-size Quick Look preview window.

Get more information about a result by selecting it and then choosing File→Get Info (⌘-I). The normal Get Info window appears, complete with date, size, and location information.

Find out where it is. It’s nice to see all the search results in one list, but you’re not actually seeing them in their native habitats: the Finder folder windows where they physically reside.

If you click once on an icon in the results, the bottom edge of the window becomes a folder map that shows you where that item is.

For example, in Figure 3-5, the notation in the Path strip means: “The 2006 corvette_owner’s manual.pdf icon you found is in the Manuals folder, which is in the Corvette folder, which is in the Documents folder, which is in Casey’s Home folder.”

To get your hands on the actual icon, choose File→Open Enclosing Folder (⌘-R). Mac OS X highlights the icon in question, sitting there in its window wherever it happens to be on your hard drive.

Open the file (or open one of the folders it’s in). If one of the found files is the one you were looking for, double-click it to open it (or highlight it and press either ⌘-O or ⌘-↑). In many cases, you don’t know or care where the file was—you just want to get into it.

Tip

You can also double-click to open any of the folders in the folder map at the bottom of the window. For example, in Figure 3-5, you could double-click the selected PDF icon to open it, or the Manuals folder to open it, and so on.

Move or delete the file. You can drag an item directly out of the found-files list and into a different folder, window, or disk—or straight to the Dock or the Trash. If you click something else and then re-click the dragged item in the results list, the folder map at the bottom of the window updates itself to reflect the file’s new location.

Start over. If you’d like to repeat the search using a different search phrase, just edit the text in the Search box. (Press ⌘-F to empty the Search box and the Spotlight window.)

Give up. If none of these avenues suits your fancy, you can close the window as you would any other (⌘-W).

You’ve just read about how Spotlight works fresh out of the box. But you can tailor its behavior, both for security reasons and to fit it to the kinds of work you do.

Here are three ways to open the Spotlight preferences center:

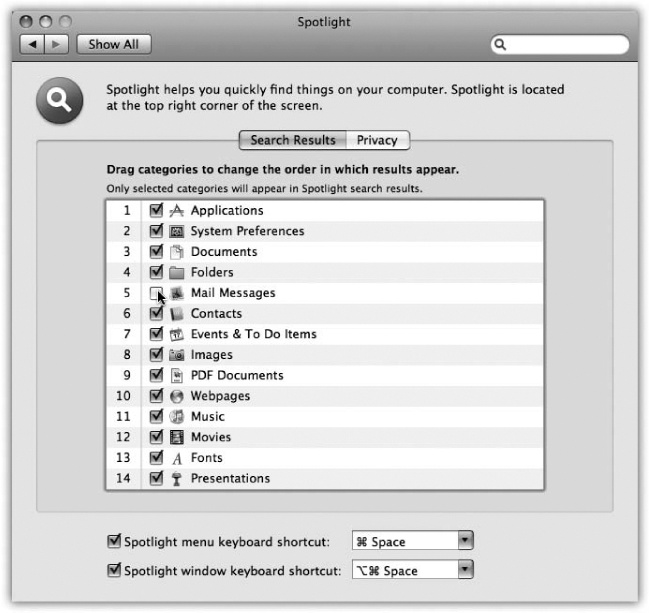

In any case, you wind up face to face with the dialog box shown in Figure 3-6.

You can tweak Spotlight in three ways here, all very useful:

Turn off categories. The list of checkboxes identifies what Spotlight tracks. If you find that Spotlight uses up valuable menu space listing, say, Web bookmarks or fonts—stuff you don’t need to find very often—then turn off their checkboxes.

Now the Spotlight menu’s 20 precious slots are allotted to icon types you care more about.

Prioritize the categories. This dialog box also lets you change the order of the category results; just drag a list item up or down to change where it appears in the Spotlight menu.

The factory setting is for Applications to appear first in the results. That makes a lot of sense if you use Spotlight as a quick program launcher (which is a great idea). But if you’re a party planner, and you spend all day on the phone, and the most important Spotlight function for you is its ability to look up someone in your Address Book, then drag Contacts to the top of the list. You’ll need fewer arrow-key presses once the results menu appears.

Change the keystroke. Ordinarily, pressing ⌘-space bar highlights the Spotlight Search box in your menu bar, and Option-⌘-space bar opens the Spotlight window described above. If these keystrokes clash with some other key assignment in your software, though, you can reassign them to almost any other keystroke you like.

Figure 3-6. Here’s where you can specify what categories of icons you want Spotlight to search, which order you want them listed in the Spotlight menu, and what keystroke you want to use for highlighting the Spotlight Search box.

Most people notice only the pop-up menu that lets you select one of your F-keys (the function keys at the top of your keyboard). But you can also click inside the white box that lists the keystroke and then press any key combination—Control-S, for example—to choose something different.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: You can now choose any available keystroke. You’re no longer required to include one of the F-keys (such as F4).

Apple assumes no responsibility for your choosing a keystroke that messes up some other function on your Mac. ⌘-S, for example, would not be a good choice.

On the other hand, if you choose a Spotlight keystroke that Mac OS X uses for some other function (like Shift-⌘-3), a little yellow alert icon appears in the Spotlight pane. This icon is actually a button; clicking it brings you to the Keyboard & Mouse pane, where you can see exactly which keystroke is in dispute and change it.

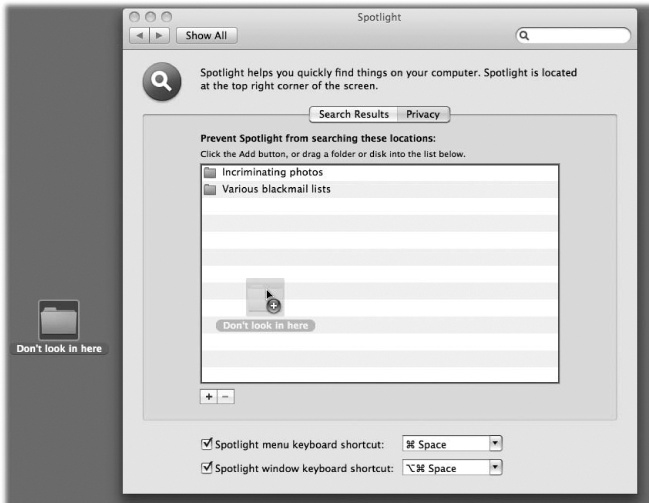

Ordinarily, Spotlight looks for matches wherever it can, except in other people’s Home folders. (That is, you can’t search through other people’s stuff).

But even within your own Mac world, you can hide certain folders from Spotlight searches. Maybe you have privacy concerns—for example, you don’t want your spouse Spotlighting your stuff while you’re away from your desk. Maybe you just want to create more focused Spotlight searches, removing a lot of old, extraneous junk from its database.

Figure 3-7. You can add disks, partitions, or folders to the list of non-searchable items just by dragging them from the desktop into this window. Or, if the private items aren’t visible at the moment, you can click the  button, navigate your hard drive, select the item, and click Choose. To remove something from this list, click it and then press the Delete key or click the

button, navigate your hard drive, select the item, and click Choose. To remove something from this list, click it and then press the Delete key or click the  button.

button.

Either way, the steps are simple. Open the Spotlight panel of System Preferences, as described previously. Click the Privacy tab. Figure 3-7 explains the remaining steps.

Tip

When you mark a disk or folder as non-searchable, Spotlight actually deletes its entire index (its invisible card-catalog filing system) from that disk. If Spotlight ever seems to be acting wackily, you can use this function to make it rebuild its own index file on the problem disk. Just drag the disk into the Privacy list and then remove it again. Spotlight deletes, and then rebuilds, the index for that disk.

(Don’t forget the part about “remove it again,” though. If you add a disk to the Privacy list, Spotlight is no longer able to find anything on it, even if you can see it right in front of you.)

Once you’ve built up the list of private disks and folders, close System Preferences. Spotlight now pretends the private items don’t even exist.

You may remember from Chapter 1 (or from staring at your own computer) that the Sidebar at the left side of every desktop window contains a set of little folders under the Searches heading. Each is actually a smart folder—a self-updating folder that, in essence, performs a continual, 24/7 search for the criteria you specify. (Smart folders are a lot like smart albums in iPhoto and iTunes, smart mailboxes in Mail, and so on.)

Note

In truth, the smart folder performs a search for the specified criteria at the moment you open it. But because it’s so fast, it feels as though it’s been quietly searching all along.

The ones installed there by Apple are meant as inspiration for you to create your own smart folders. The key, as it turns out, is the little Save button in the upper-right corner of the Spotlight window.

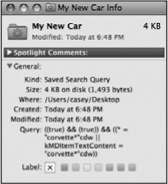

Here’s a common example—one that you can’t replicate in any other operating system. You choose File→Find. You set up the pop-up menus to say “last opened date” and “this week.” You click Save. You name the smart folder something like Current Crises, and you turn on “Add to Sidebar” (Figure 3-8).

Tip

Behind the scenes, smart folders you create are actually special files that are stored in your Home→Library→Saved Searches folder.

From now on, whenever you click that smart folder, it reveals all the files you’ve worked on in the past week or so. The great part is that these items’ real locations may be all over the map, scattered in folders all over your Mac and your network. But through the magic of the smart folder, they appear as though they’re all in one neat folder.

Tip

If you decide your original search criteria need a little fine-tuning, click the smart folder. From the  menu, choose Show Search Criteria. You’re back on the original setting-up-the-search window. Use the pop-up menus and other controls to tweak your search setup, and then click the Save button once again.

menu, choose Show Search Criteria. You’re back on the original setting-up-the-search window. Use the pop-up menus and other controls to tweak your search setup, and then click the Save button once again.

To delete a smart folder, just drag its icon out of the Sidebar. (Or if it’s anywhere else, like on your desktop, drag it to the Trash like any other folder.)