Somewhere between email and the telephone lies a unique communication tool called instant messaging. Plenty of instant messenger programs run on the Mac, but guess what? You don’t really need any of them. Mac OS X comes with its very own instant messenger program called iChat, built right into the system and ready to connect to your friends on the AIM, Jabber, or GoogleTalk networks.

In Snow Leopard, iChat was the focus of a lot of refinement and polish. Video conversations now require much lower bandwidth, meaning that slower Internet connections may now be eligible to try out video chats. The window for iChat Theater (when you show a movie or slideshow presentation to someone on the other end) can now be four times as big as before (640 x 480 pixels, for example). And so on.

To start up iChat, go to Applications→iChat, or just click iChat’s Dock icon. This chapter covers how to use iChat to communicate by video, audio, and text with your online pals.

iChat does five things very well:

Instant messaging. If you don’t know what instant messaging is, there’s a teenager near you who does.

It’s like live email. You type messages in a chat window, and your friends type replies back to you in real time. Instant messaging combines the privacy of email and the immediacy of the phone.

In this regard, iChat is a lot like the popular AOL Instant Messenger (AIM) and Buddy Chats. In fact, iChat lets you type back and forth with any of AIM’s 150 million members, which is a huge advantage. (It speaks the same “chat” language as AIM.) But iChat’s visual design is pure Apple.

Free long distance. If your Mac has a microphone, and your buddy’s does, too, the two of you can also chat out loud, using the Internet as a free long-distance phone. Wait, not just the two of you—the 10 of you, thanks to iChat’s party-line feature.

Free videoconferencing. If you and your buddies all have broadband Internet connections and a camera—like the one built into many Mac models—or even a digital camcorder, up to four participants can join in video chats, all onscreen at once, no matter where they happen to be in the world. This arrangement is a jaw-dropping visual stunt that can bring distant collaborators face to face without plane tickets—and it costs about $99,900 less than professional videoconferencing gear.

File transfers. Got an album of high-quality photos or a giant presentation file that’s too big to send by email? Forget about using some online file-transfer service or networked server; you can drag that monster file directly to your buddy’s Mac, through iChat, for a direct machine-to-machine transfer. (It lands in the other Mac’s Downloads folder.)

Presentations. You can open up most kinds of documents, at nearly full size, to show your video buddy, right there in the iChat window, without actually having to transfer it. That’s iChat Theater.

iChat lets you reach out to chat partners on three networks:

The AIM network. If you’ve signed up for a MobileMe address (the paid kind or the free kind described below) or a free AOL Instant Messenger (AIM) account, you can chat with anyone in the 150 million-member AOL Instant Messenger network.

The Jabber network. Jabber is a chat network whose key virtue is its open-source origins. In other words, it wasn’t masterminded by some corporate media behemoth; it’s an all-volunteer effort, joined by thousands of programmers all over the world. There’s no one Jabber chat program (like AOL Instant Messenger). There are dozens, available for Mac OS X, Windows, Linux, Unix, iPhone, Palm organizers, and so on. They can all chat with one another across the Internet in one glorious frenzy of typing.

And now there’s one more program that can join the party: iChat.

Google Talk. Evidently, Google felt that there just weren’t enough different chat programs, because it released its own in 2005.

Behind the scenes, it uses the Jabber network, so Google Talk doesn’t really count as a different network. (Hence the headline.) But it does mean you can use iChat to converse with all those Google Talkers, too.

Your own local network. Thanks to the Bonjour network-recognition technology, you can communicate with other Macs on your own office network without signing up for anything at all—and without being online. This is a terrific feature when you’re sitting around a conference table, idly chatting with colleagues using your wireless laptop (and the boss thinks you’re taking notes). It’s also handy when you want to type little messages throughout the day to a family member downstairs, or a roommate 15 feet away.

Each network generally has its own separate Buddy List window and its own chat window, but you can consolidate all your chats into a single window (You Invite Them).

You log into each network separately using the iChat→Accounts submenu, but you can be logged into all of them at once. This is a great option if your friends are spread out among different chat networks.

Note

If you’re on AOL’s AIM service, why would you want to use iChat instead? Easy: Because iChat is a nice, cleanly designed program that’s free of advertisements, chatbots, and clunky interface elements.

Otherwise, however, chatting and videoconferencing works identically on all three networks. Keep that in mind as you read the following pages.

When you open iChat for the first time, you see the “Welcome To iChat” window (Figure 21-1). This is the first of several screens in the iChat setup sequence, during which you’re supposed to tell it which kinds of chat accounts you have and set up your camera, if any.

An account is a name and password. Fortunately, these accounts are free, and there are several ways to acquire one.

Tip

The easiest procedure is to set up your accounts before you open iChat for the first time, because then you can just plug in your names and passwords in the setup screens.

You can input your account information later, though. Choose iChat→Preferences, click the Accounts button, click the  button, and choose the right account type (Jabber, MobileMe, Google Talk, or AIM) from the Account Type pop-up menu.

button, and choose the right account type (Jabber, MobileMe, Google Talk, or AIM) from the Account Type pop-up menu.

If you’re already a member of Apple’s MobileMe service (Chapter 18), iChat fills in your member name and password automatically.

If not, you can get an iChat-only MobileMe account for free. To get started, do one of these two things:

Either way, you go to an Apple Web page, where you can sign up for a free iChat account name. You also get 60 days of the more complete MobileMe treatment (usually $100 a year) described in Chapter 18. When your trial period ends, you lose all the other stuff MobileMe provides, but you do get to keep your iChat name.

Note

If your MobileMe name is missingmanualguy, you’ll appear to everyone else as missingmanualguy@mac.com. The software tacks on the “@me.com” suffix automatically.

Figure 21-1. The iChat setup assistant gives you the chance to input your account names and passwords if you already have them. Only one of these screens (“Set up iChat Instant messaging”) offers you the chance to create a chat account, in this case a free MobileMe account. Otherwise, you’re expected to have a name and password (for AIM, Google Talk, or Jabber, for example) already.

You can’t create a Jabber account using iChat. Apple expects that, if you’re that interested in Jabber, you already have an account that’s been set up by the company you work for (Jabber is popular in corporations) or by you, using one of the free Jabber programs.

Alternatively, you can just sign up for a free Google Talk account, which is the same as having a free Gmail account. (Go to Gmail.com to sign up for one.)

Once you’ve got a Gmail address, choose iChat→Preferences→Accounts, and click the  button. Under Account Type, choose Google Talk and type in your complete Gmail address (like gwashington@gmail.com) and password. Your Gmail name pops up on iChat’s Jabber list—along with any of your Gmail contacts who are already online and yapping.

button. Under Account Type, choose Google Talk and type in your complete Gmail address (like gwashington@gmail.com) and password. Your Gmail name pops up on iChat’s Jabber list—along with any of your Gmail contacts who are already online and yapping.

If you’re an America Online member, your existing screen name and password work; if you’ve used AIM before, you can use your existing name and password.

If you’ve never had an AIM account, then choose AIM from the Account Type pop-up menu, and then click Get an iChat Account. You’re taken to the Web, where you can make up an AIM screen name.

Once you’ve entered your account information, you’re technically ready to start chatting. All you need now is a chatting companion, or what’s called a buddy in instant-messaging circles. iChat comes complete with a Buddy List window where you can house the chat “addresses” for all your friends, relatives, and colleagues out there on the Internet.

Actually, to be precise, iChat comes with three Buddy Lists (Figure 21-2):

AIM Buddy List. This window lists all your chat pals who have either MobileMe or AIM accounts; they all share the same Buddy List. You see the same list whether you log into MobileMe or your AIM account.

Jabber List. Same idea, except that all your contacts in this window must have Jabber or Google Talk accounts.

Bonjour. This list is limited to your local network buddies—the ones in the same building, most likely, and on the same network. You can’t add names to your Bonjour list; anyone who’s on the network and running iChat appears automatically in the Bonjour list.

When you start iChat, your Buddy Lists automatically appear (Figure 21-2). If you don’t see them, choose the list you want from the Window menu: [Your MobileMe/AIM account], Bonjour List, or Jabber List. (Or press their keyboard shortcuts: ⌘-1, ⌘-2, or ⌘-3.)

Adding a buddy to this list entails knowing that person’s account name, whether it’s on AIM, MobileMe, or Jabber. Once you have it, you can either choose Buddies→Add Buddy (Shift-⌘-A) or click the  button at the bottom-left corner of the window.

button at the bottom-left corner of the window.

Down slides a sheet attached to the Buddy List window, offering a window into the Address Book program (Chapter 19).

Tip

As you accumulate buddies, your Buddy List may become crowded. If you choose View→Show Offline Buddies (so that the checkmark disappears), only your currently online buddies show up in the Buddy List—a much more meaningful list for the temporarily lonely.

Figure 21-2. Left: Click the  button to add a new buddy, either by choosing from your address book or from scratch (by clicking New Person). If you’ve used AIM before, you may find that you’ve already got buddies in your list. AIM accounts store their Buddy Lists on AOL’s computers, so you can keep your buddies even if you switch computers. Right: Is your Buddy List taking up too much screen space? Use the options in the View menu to lose the buddy pictures and other chunky icons to streamline the window.

button to add a new buddy, either by choosing from your address book or from scratch (by clicking New Person). If you’ve used AIM before, you may find that you’ve already got buddies in your list. AIM accounts store their Buddy Lists on AOL’s computers, so you can keep your buddies even if you switch computers. Right: Is your Buddy List taking up too much screen space? Use the options in the View menu to lose the buddy pictures and other chunky icons to streamline the window.

If your chat companion is already in Address Book, scroll through the list until you find the name you want (or enter the first few letters into the Search box), click the name, and then click Select Buddy.

If not, click New Person and enter the buddy’s AIM address, MobileMe address, or (if you’re in the Jabber list) Jabber address. You’re adding this person to both your Buddy List and to your Address Book.

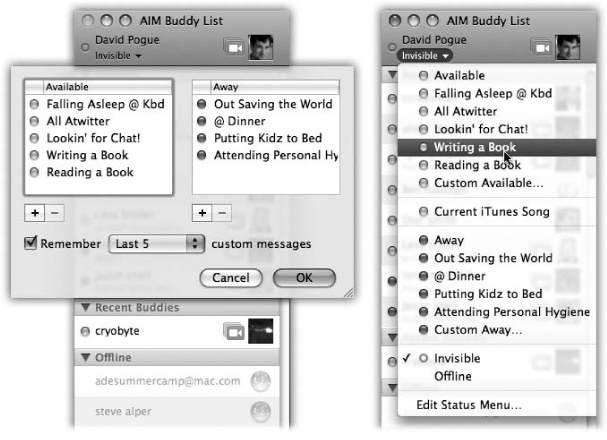

Using the pop-up menu just below your name (Figure 21-3, right), you can display your current mental status to other people’s Buddy Lists. You can announce that you’re Available, Away, or Drunk. (You have to choose Edit Status Menu for that last one; see Figure 21-3, left.)

Better yet, if you have music playing in iTunes, you can tell the world what you’re listening to at the moment by choosing Current iTunes Song. (Your buddy can even click that song’s name to open its screen on the iTunes Store, all for Instant Purchase Gratification.)

For some people, by far the juiciest status option is Invisible (available for MobileMe and AIM accounts only). It’s like a Star Trek cloaking device for your onscreen presence (Figure 21-3). Great for stalkers!

Figure 21-3. Left: Choose Edit Status Menu from the pop-up menu at the top of the iChat Buddy List to set up more creative alternatives to “Available” and “Away.” Right: Your edited list of status messages is now available. The most interesting one is Invisible. It lets you see your friends online, but they can’t see you—great when you’re too busy to chat with annoying barely-acquaintances but want to keep an eye out for a particular pal. You can still send and receive messages to anyone on your Buddy List.

In View→Sort Buddies, you can rearrange your buddies as they’re listed in the Buddy Lists:

By Availability. Your available pals move to the top of the list, sorted alphabetically by last name. Unavailable buddies (marked by red dots and visible Away messages) get shoved to the bottom.

By First Name, By Last Name. Just what you’d think.

Manually. This option lets you drag your friends up and down your Buddy List in order of your purely personal preferences, regardless of the alphabet.

Tip

In View→Buddy Names, you can chose to see your friends listed by Full Names, Short Names (usually the first name), or by Handle (IM screen name). If your Buddy List is showing screen names (“jdeaux444”) mixed in with proper names (“Johann Deux”), it’s because you haven’t recorded the real-nameless people’s real names. Click a buddy’s name, choose Buddies→Show Info, then click Address Card to fill in the person’s first and last names.

Once you get a lot of people piled on your list, all with their buddy pictures and audio/video chat icons, you may feel like iChat is taking up way too much screen real estate. If you want a more space-efficient view of your Buddy List (like the one shown on the right in Figure 21-2), go to the View menu and turn off Show Buddy Pictures, Show Audio Status, or Show Video Status. You can turn off Buddy Groups here as well, if you’d prefer to see your buddies in one undivided list.

As with any conversation, somebody has to talk first. In chat circles, that’s called inviting someone to a chat.

To “turn on your pager” so you’ll be notified when someone wants to chat with you, run iChat. Hide its windows, if you like, by pressing ⌘-H.

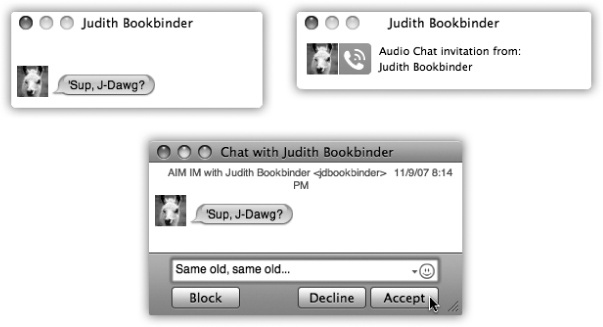

When someone tries to “page” you for a chat, iChat comes forward automatically and shows you an invitation message like the one in Figure 21-4. If the person initiating a chat isn’t already in your Buddy List, you’ll simply see a note that says “Message from [name of the person].”

Tip

If you’re getting hassled by someone on your AIM/MobileMe Buddy List, click his screen name and choose Buddies→Block Person. If the person isn’t online at the time, go to iChat→Preferences→Accounts→Security and click the button for “Block specific people.” Click the Edit List button, and then type in the screen name of the person you want out of your IM life.

Figure 21-4. You’re being invited to a chat! Your buddy wants to have a typed chat (top left) or a spoken one (top right). To begin chatting, click the invitation window, type a response in the bottom text box if you like (for text chats), and click Accept (or press Return). Or click Decline to lock out the person sending you messages—a good trick if someone’s harassing you.

To invite somebody in your Buddy List to a chat:

For a text chat, double-click the person’s name, type a quick invite (“You there?”), and press Return.

You can invite more than one person to the chat. Each time you click the

button at the bottom of the Participants list, you choose another person to invite. (Or ⌘-click each name in the Buddy List to select several people at once and then click the A button at the bottom of the list to start the text chat.) Everyone sees all the messages anyone sends.

button at the bottom of the Participants list, you choose another person to invite. (Or ⌘-click each name in the Buddy List to select several people at once and then click the A button at the bottom of the list to start the text chat.) Everyone sees all the messages anyone sends.To start an audio or video chat, click the microphone or movie-camera icon in your Buddy List (shown in Figure 21-2).

To initiate a chat with someone who isn’t in the Buddy List, choose File→New Chat With Person. Type the account name, and then click OK to send the invitation.

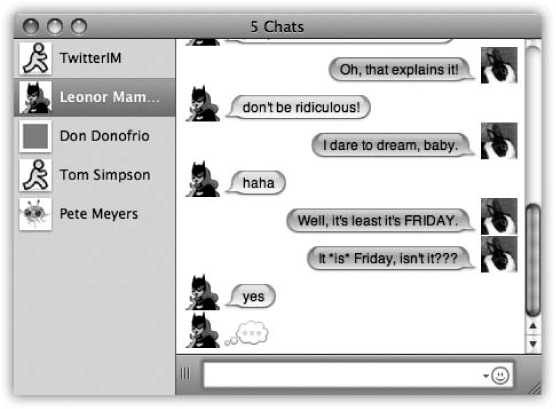

Either way, you can have more than one chat going at once. Real iChat nerds often wind up with screens overflowing with individual chat windows.

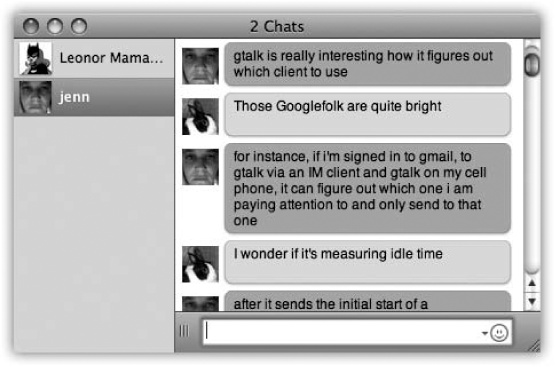

But in modern times, you can now contain all your conversations in a single window. If you like the idea of a consolidated chatspace, choose iChat→Preferences→Mes-sages and slap a checkmark in the “Collect chats in a single window” box. Figure 21-5 shows the result.

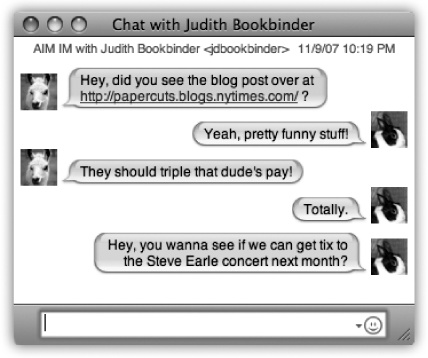

A typed chat works like this: Each time you or your chat partner types something and then presses Return, the text appears on both of your screens (Figure 21-6). iChat displays each typed comment next to an icon, which can be any of these three things:

A picture they added. If the buddy added her own picture—to her own copy of iChat, a Jabber program, or AOL Instant Messenger—it will be transmitted to you, appearing automatically in the chat window. Cool!

Figure 21-6. As you chat, your comments always appear on the right. If you haven’t yet created a custom icon, you’ll look like a blue globe or an AOL running man. You can choose a picture for yourself either in your own Address Book card or right in iChat. And Web links your pals paste into messages are perfectly clickable—your Web browser leaps right up to take you to the site your friend has shared.

A picture you added. If you’ve added a picture of that person to the Buddy List or Address Book, you see it here instead. (After all, your vision of what somebody looks like may not match his own self-image.)

Generic. If nobody’s done icon-dragging of any sort, you get a generic icon—either a blue globe (for MobileMe people), a light bulb (for Google Talkers), or the AOL Instant Messenger running man (for AIM people).

To choose a graphic to use as your own icon, click the square picture to the right of your own name at the top of the Buddy, Jabber, or Bonjour list. From the pop-up palette of recently selected pictures, choose Edit Picture to open a pop-up image-selection palette, where you can take a snapshot with your Mac’s camera or choose a photo file from your hard drive. Feel free to build an array of graphics to represent yourself—and to change them in midchat, using this pop-up palette, to the delight or confusion of your conversation partner.

Tip

When you minimize the iChat message window, its Dock icon displays the icon of the person you’re chatting with—a handy reminder that she’s still there.

Typing isn’t the only thing you can do during a chat. You can also perform any of these stunts:

Open the drawer. Choose View→Show Chat Participants to hide or show the “drawer” that lists every person in your current group chat. To invite somebody new to the chat, click the

button at the bottom of the drawer, or drag the person’s icon out of the Buddy List window and into this drawer.

button at the bottom of the drawer, or drag the person’s icon out of the Buddy List window and into this drawer.Format your text. You can press ⌘-B or ⌘-I to make your next typed utterance bold or italic. Or change your color or font by choosing Format→Show Colors or Format→Show Fonts, which summons the standard Mac OS X color or font palettes. (If you use some weird font that your chat partners don’t have installed, they won’t see the same typeface.)

Insert a smiley. When you choose a face (like Undecided, Angry, or Frown) from this quick-access menu of smiley options (at the right end of the text-reply box), iChat inserts it as a graphic into your response.

On the other hand, if you know the correct symbols to produce smileys—that:) means a smiling face, for example—you can save time by typing them instead of using the pop-up menu. iChat converts them into smiley icons on the fly, as soon as you send your reply.

Send a file. Choosing Buddies→Send File lets you send a file to all the participants in your chat.

Better yet, just drag the file’s icon from the Finder into the box where you normally type. (This trick works well with pictures, because your conversation partner sees the graphic right in his iChat window.)

This is a fantastic way to transfer a file that would be too big to send by email. A chat window never gets “full,” and no attachment is too large to send.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: You can now use Quick Look on a file someone’s sending you in iChat, to have a full-size look at it before downloading. Just choose File→Quick Look after someone’s sent you something (or click its thumbnail and press the space bar).

This method halves the time of transfer, too, since your recipients get the file as you upload it. They don’t have to wait 20 minutes for you to send the file, and then another 20 minutes to download it, as they would with email or FTP.

Note, though, that this option isn’t available in old versions of the AOL Instant Messenger program—only new versions and iChat.

If you have multiple conversations taking place—and are flinging files around to a bunch of people—you can keep an eye on each file’s progress with the File Transfer Manager. Choose Window→File Transfers (or press Option-⌘-L) to pop open an all-in-one document delivery monitor.

Get Info on someone. If you click a name in your Buddy list, and then choose Buddies→Show Info (or Control-click someone’s name and choose Show Info from the shortcut menu), you get a little Info window about your buddy, where you can edit her name, email address, and picture. (If you change the picture here, you’ll see it instead of the graphic your buddy chose for herself.)

If you click the Alerts tab at this point, you can make iChat react when this particular buddy logs in, logs out, or changes status—for example, by playing a sound or saying, “She’s here! She’s here!”

Send an Instant Message. Not everything in a chat session has to be “heard” by all participants. If you choose Buddies→Send Instant Message, you get a private chat window, where you can “whisper” something directly to a special someone behind the other chatters’ backs.

Send a Secure Message. Fellow MobileMe members can engage in encrypted chats that keep the conversation strictly between participants. If you didn’t turn on encrypted chats when you set up your MobileMe account in iChat, choose iChat→Preferences→Accounts→Security, and then click Enable.

Send Email. If someone messages you, “Hey, will you email me directions?” you can do so on the spot by choosing Buddies→Send Email. Your email program opens up automatically so you can send the note along; if your buddy’s email address is part of his Address Book info, the message is even preaddressed.

Send an SMS message to a cellphone. If you’re using an AIM screen name or MobileMe account, you can send text messages directly to your friends’ cellphones (in the United States, anyway). Choose File→Send SMS. In the box that pops up, type the full cellphone number, without punctuation, like this: 2125551212.

Press Return to return to the chat window. Type a very short message (a couple of sentences, tops), and then press Return.

Tip

If iChat rudely informs you that your own privacy settings prevent you from contacting “this person,” choose iChat→Preferences, click Accounts, click your chat account, and turn on “Allow anyone.”

Obviously, you can’t carry on much of an interactive conversation this way. The only response you get is from AOL’s computers, letting you know that your message has been sent. But what a great way to shoot a “Call me!” or “Running late—see you tonight!” or “Turn on Channel 4 right now!!!” message to someone’s phone.

On the other hand, if you’re going to be away from your Mac for a few hours, you can have iChat forward incoming chat messages to your cellphone. Choose iChat→Preferences→Accounts and click Configure AIM Mobile Forwarding. In the resulting window, fill in your own cellphone number, so the incoming messages know where to go.

The words you might have for iChat’s word-balloon design might be “cute” and “distinctive.” But it’s equally likely that your choice of adjectives includes “juvenile” and “annoying.”

Fortunately, behind iChat’s candy coating are enough options tucked away in the View menu that you’ll certainly find one that works for you (see Figure 21-7).

You can even change iChat’s white background to any image using View→Set Chat Background. Better yet, find a picture you like and drag it into your chat window; iChat immediately makes it the background of your chat. To get rid of the background and revert to soothing white, choose View→Clear Chat Background.

iChat becomes much more exciting when you exploit its AV Club capabilities. Even over a dial-up modem connection, you can conduct audio chats, speaking into your microphone and listening to the responses from your speaker.

Figure 21-7. iChat can look like almost anything. Here, for example, is what a chat looks like with the balloon effect turned off (giving you colored rectangles instead). You can even turn off balloons and pictures if they bother you that much. You can also hide the names. You make these changes for a chat in progress using the View menu. You can also change the color and typeface settings in the iChat→Preferences→Messages panel.

If you have a broadband connection, though, you get a much more satisfying experience—and, if you have a pretty fast Mac, up to 10 of you can join in one massive, free conference call from across the Internet.

A telephone icon next to a name in your Buddy List tells you that the buddy has a microphone and is ready for a free Internet “phone call.” If you see what appear to be stacked phone icons, then your pal’s Mac has enough horsepower to handle a multiple-person conference call. (You can see these icons back in Figure 21-2.)

To begin an audio chat, you have three choices:

Click the telephone icon next to the buddy’s name.

Highlight someone in the Buddy List, and then click the telephone icon at the bottom of the list.

If you’re already in a text chat, choose Buddies→Invite to Audio Chat.

Once your invitation is accepted, you can begin speaking to each other. The bars of the sound-level meter let you know that the microphone—which you’ve specified in the iChat→Preferences→Audio/Video tab—is working.

If you and your partner both have broadband Internet connections, even more impressive feats await. You can conduct a free video chat with up to four people, who show up on three vertical panels, gorgeously reflected on a shiny black table surface. This isn’t the jerky, out-of-audio-sync, Triscuit-sized video of days gone by. If you’ve got the Mac muscle and bandwidth, your partners are as crisp, clear, bright, and smooth as television—and as big as your screen, if you like.

People can come and go; as they enter and leave the “videosphere,” iChat slides their glistening screens aside, enlarging or shrinking them as necessary to fit on your screen.

Apple offers this luxurious experience, however, only if you have luxurious gear:

A video camera. It can be the tiny iSight camera that’s embedded above the screens of iMacs and laptops; an external FireWire iSight camera; an ordinary digital cam-corder; or a golf-ball Webcam that connects via FireWire instead of USB.

Bandwidth. You need Internet upload/download speeds of at least 100 kilobits per second for basic, tiny video chats with one other person, and a minimum of 384 Kbps for four-way video chats. And those are for the smallest video windows. Starting a video chat at the highest video quality requires 300 Kbps uploading bandwidth. That requirement is a heck of a lot lower than in the pre–Snow Leopard iChat, but it may still be too rich for residential DSL packages.

Tip

As you’re beginning to appreciate, iChat’s system requirements are all over the map. Some features require very little horsepower; others require tons.

To find out exactly which features your Mac can handle, choose Video→Connection Doctor; from the Show pop-up menu, choose Capabilities. There’s a little chart of all iChat features, showing checkmarks for the ones your Mac can manage.

If you see a camcorder icon next to a buddy’s name, you can have a full-screen, high-quality video chat with that person, because they, like you, have a suitable camera and a high-speed Internet connection. If you see a stacked camcorder icon, then that person has a Mac that’s capable of joining a four-way video chat.

To begin a video chat, click the camera icon next to a buddy’s name, or highlight someone in the Buddy List and then click the camcorder icon at the bottom of the list. Or, if you’re already in a text chat, choose Buddies→Invite to Video Chat.

A window opens, showing you. This Preview mode is intended to show what your buddy will see. (You’ll probably discover that you need some kind of light in front of you to avoid being too shadowy.) As your buddies join you, they appear in their own windows (Figure 21-8).

Figure 21-8. That’s you in the smaller window. To move your own mini-window, click a different corner, or drag yourself to a different corner. If you need to blow your nose or do something else unseemly, Option-click the microphone button to freeze the video and mute the audio. Click again to resume.

And now, some video-chat notes:

If your conversation partners seem unwilling to make eye contact, it’s not because they’re shifty. They’re just looking at you, on the screen, rather than at the camera—and chances are you aren’t looking into your camera, either.

You can have video chats with Windows computers, too, as long as they’re using a recent version of AOL Instant Messenger. Be prepared for disappointment, though; the video is generally jerky, small, and slightly out of sync. That’s partly due to the cheap USB Webcams most PCs have, and partly due to the poor video codec (compression scheme) built into AIM.

If you use iChat with a camcorder, then you can set the camera to VTR (playback) mode and play a tape right over the Internet to a buddy on the other end! (The video appears flipped horizontally on your screen but looks right to the other person.)

You can capture a still “photo” of a video chat by ⌘-dragging the image to your desktop, or by choosing Video→Take Snapshot (Option-⌘-S).

Don’t want to see yourself in the picture-in-picture window during your video chat? Choose Video→Hide Local Video.

This cutting-edge technology can occasionally present cutting-edge glitches. The video quality deteriorates, the transmission aborts suddenly, the audio has an annoying echo, and so on. When problems strike, iChat Help offers a number of tips; the Video→Connection Doctor can identify your network speed. (iChat video likes lots of network speed.)

Just as you can save your typed transcripts of instant message conversations, you can record your audio and video chats. Once you start a chat, choose Video→Re-cord Chat. Your buddy is asked if it’s OK for you to proceed with the recording (to ward off any question of those pesky wiretapping laws); if permission is granted, then iChat begins recording the call.

When you’ve got what you want, click Stop. Your recordings are automatically saved into Home→Documents→iChats (AAC files for audio conversations, MPEG-4 files for video chats). From there, you can drag them into iTunes to play or sync them up with an iPod or iPhone. Yes, you can now relive those glorious iChat moments when you’re standing in line at the grocery store.

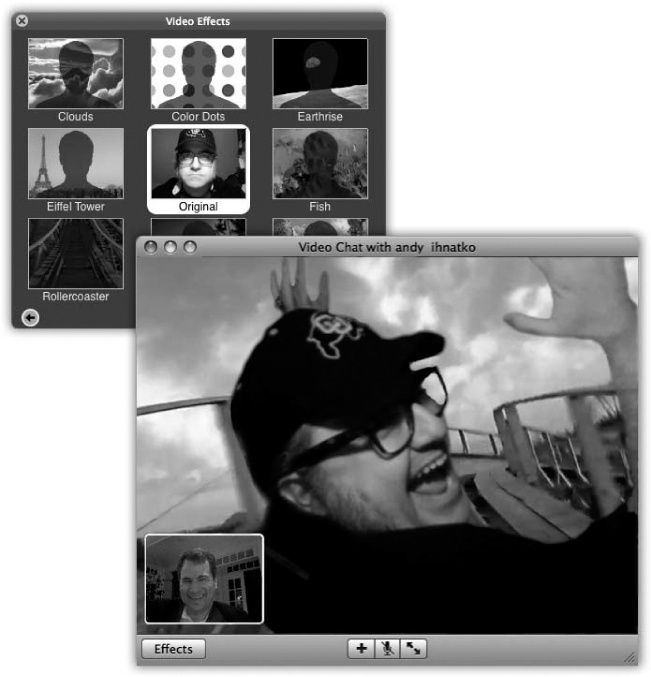

If your video chats look like a bunch of cubicle-dwellers sitting around chatting at their desks, you can liven things up with one of iChat’s most glamorous and jaw-dropping features: photo or video backgrounds for your talking head. Yes, now you can make your video chat partners think you’re in Paris, on the moon, or even impersonating a four-panel Andy Warhol silkscreen.

Note

The iChat and Photo Booth backdrop effects are serious, serious processor hogs; they require bandwidth, man, serious bandwidth—at least 128 Kbps for both upload and download speeds.

Here’s how to prepare your backdrop for a video chat:

Go to iChat→Preferences→Audio/Video.

A video window opens so you can see yourself.

Press Shift-⌘-E (or go to Video→Show Video Effects).

The Effects box appears, looking a lot like the one in Photo Booth (Chapter 10); a lot of the visual backdrops are quite similar. Click the various squares of the tictac-toe grid to see how each effect will transform you in real time: making your face bulbous, for example, or rendering you in delicate colored pencil shadings.

The first two pages of effects all do video magic on you and everything else in the picture. If you want one of those, click it; you’re done. There’s no step 3. Your video-chat buddies now see you in your distorted or artistic new getup.

The second two pages of effects, however, don’t do anything to your image. Instead, they replace the background.

This is the really amazing part. In TV and movies, replacing the background is an extremely common special effect. All you have to do is set up a perfectly smooth, evenly lit, shadowless blue or bright green backdrop behind the subject. Later, the computer replaces that solid color with a new picture or video of the director’s choice.

iChat, however, creates exactly the same special effect (Figure 21-9) without requiring the bluescreen or the greenscreen. Read on.

Click the background effect you want.

Suppose, for example, that you’ve clicked the video loop showing the Eiffel Tower with people walking around. At this point, a message appears on the screen that says, “Please step out of the frame.”

Duck out of camera range (or move off to one side).

See, iChat intends to memorize a picture of the real background—without you in it. When you return to the scene, your high-horsepower Mac then compares each pixel of its memorized image with what it’s seeing now. Any differences, it concludes, must be you. And that is how it can create a bluescreen effect without a bluescreen.

When the screen says, “Background detected,” step back into the frame.

Zut alors! You are now in virtual Paris. Go ahead and start the video chat with your friends, and don’t forget your beret.

If you want to clear out the background or change it, click the Original square in the middle of the Effects palette and then choose a different backdrop. (You can also change backdrops in midchat by choosing Video→Show Video Effects to open the Effects palette.)

If things get too weird and choppy onscreen, you can restore the normal background by choosing Video→Reset Background. (That’s also handy if you suddenly have to have a video talk with your boss about your excessive use of iChat while he’s away on his business trip.)

Tip

You can use one of your own photos or video clips as iChat backdrops, too. In the Video Effects box, click the arrows on the bottom until you get to the screen with several blank User Backdrop screens. Next, drag a photo or video from the desktop directly onto one of the blank screens. Click it just like you would any of Apple’s stock shots.

Figure 21-9. Top left: You have plenty of backgrounds to choose from for your next video chat. Click an effect to add it to your chat window. Click the small arrows at the bottom of the window to advance or retreat through the various effects styles. Click the Original square in the middle of the window to erase the effect and start again from scratch. Lower right: Let the live bluescreen action begin!

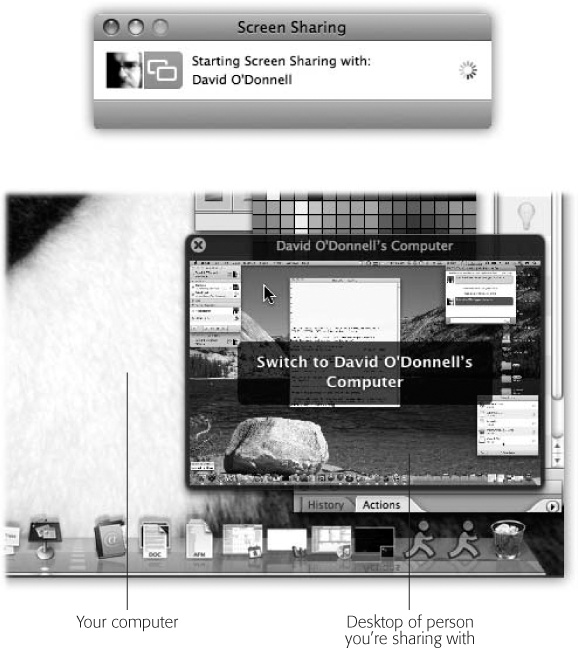

As you’ve seen already in this chapter, iChat lets you share your thoughts, your voice, and your image with the people on your Buddy Lists. And now, for its next trick, it lets you share…your computer.

iChat’s screen sharing feature is a close relative of the network screen-sharing feature described in Chapter 13. It lets you see not only what’s on a faraway buddy’s screen, but control it, taking command of the distant mouse and keyboard. (Of course, screen sharing can work the other way, too.)

You can open folders, create and edit documents, and copy files on the shared Mac screen. Sharing a screen makes collaborating as easy as working side by side around the same Mac, except now you can be sitting in San Francisco while your buddy is banging it out in Boston.

And if you’re the family tech-support specialist—but the family lives all over the country—screen sharing makes troubleshooting a heckuva lot easier. You can now jump on your Mom’s shared Mac and figure out why the formatting went wacky in her Word document, without her having to attempt to explain it to you over the phone. (“And then the little thingie disappeared and the doohickey got scrambled…”)

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: Once you’re controlling someone else’s screen remotely, your keyboard shortcuts now operate their Mac instead of yours. Press ⌘-Tab to bring up the application switcher, hit ⌘-Q to quit a program, use all the Exposé and Spotlight shortcuts, and so on.

To make iChat screen sharing work, you and your buddy must both be running Macs with Leopard or Snow Leopard. On the other hand, you can share over any account type: AIM, MobileMe, Google Talk, Bonjour, or Jabber.

To begin, click the sharee’s name in your Buddy List.

If you want to share your screen with this person, choose Buddies→Share My Screen.

If you want to see her screen (because she has all the working files on her Mac), choose Buddies→Ask to Share.

Note

Similar commands are available in the Screen Sharing pop-up button—the one that looks like two overlapping squares at the bottom of the Buddy List window. The commands say “Share My Screen with casey234” and “Ask to Share casey234’s screen.”

Once the invitation is accepted, the sharing begins, as shown in Figure 21-10. To help you communicate further, iChat politely opens up an audio chat with your buddy so you can have a hands-free discussion about what you’re doing on the shared machine.

If you’re seeing someone else’s screen, you see his Mac desktop in full-screen view, right on your own machine. You also see a small window showing your own Mac; click it to switch back to your own desktop.

Tip

To copy files from Mac to Mac, drag them between the two windows. Files dragged to your Mac wind up in your Downloads folder.

If something’s not right, or you need to bail out of a shared connection immediately, press Control-Escape on the Mac’s keyboard.

Figure 21-10. Top: You either send or receive an invitation to start sharing your screen, but make sure you know with whom you’re dealing before accepting the offer and starting the sharing process. Bottom: When you’re sharing someone else’s screen, you have the option to click back and forth between the two Mac screens.

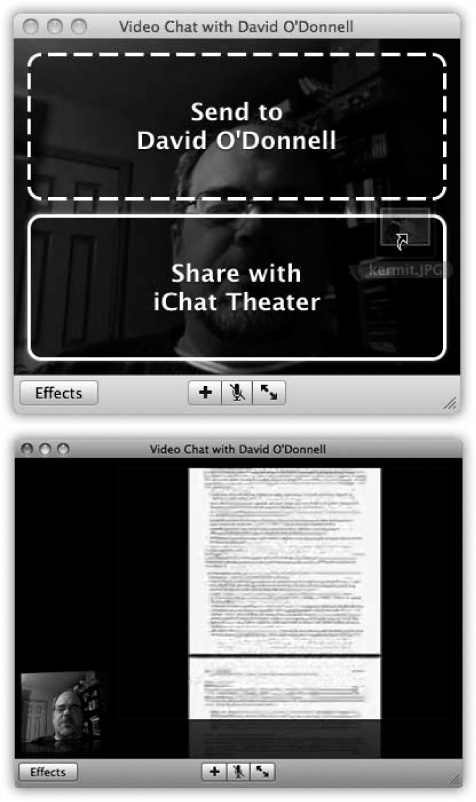

Talk about the next best thing to being there. The iChat Theater feature lets you make pitches and presentations to people and committees in faraway cities—without standing in a single airport-security line.

That’s because iChat Theater turns the chat window into a presentation screen for displaying and narrating your own iPhoto or Keynote slideshows, QuickTime movie files, and even text documents. Your buddy, on the other end of the iChat line, sees these documents at nearly full size—with you in a little picture-in-picture screen in the corner.

All you need is:

Some stuff to show off. iChat Theater can display exactly the same kinds of files that Quick Look (Chapter 1) can display: Word, Excel, and PowerPoint documents, photos, text and HTML files, PDF files, audio and movie files, fonts, vCards, Pages, Numbers, Keynote, and TextEdit documents, and so on.

A zippy broadband Internet connection. iChat Theater likes 384 kilobits per second or faster; check with your Internet provider if you aren’t sure of your connection speed.

To get the show running, you can take one of two approaches.

Figure 21-11. Top: You can start an iChat Theater session by choosing File→Share a File with iChat Theater, or as shown here, by simply dropping the file on an open video chat window and going for the iChat Theater option. Bottom: Once you’ve started a Theater show in Chat, the shared file takes center stage so you both can look at it and discuss amongst yourselves.

If a video chat is under way, you can just drag the file(s) you want to share into the video window. iChat asks if you want to send the file to the person or share it with iChat Theater (Figure 21-11, top). Click iChat Theater, of course.

If no video chat is in progress, choose File→Share a File in iChat Theater. Locate the file you want to present on your hard drive. When iChat asks you to start a video chat with the buddy who’s going to be your audience, click the video-camera icon next to that person’s name (or choose Video→Invite to Video Chat).

When your friend accepts, the curtain goes up, as shown the bottom of Figure 21-11. The file you’re sharing takes center stage (er, window) and your buddy appears in a little video window off to the side. Click the  button to expand the view to full screen.

button to expand the view to full screen.

If you have iPhoto ’08 or later, sharing picture albums is one menu command away: Choose File→Share iPhoto with iChat Theater. When the Media Browser pops up, pick the album you want to present. The first picture in the selected album appears in the iChat window before iPhoto itself opens, so you can use iPhoto’s nice controls for cruising forward (or backward) through your album.

The same thing happens if you’re running a Keynote presentation in iChat Theater: The first slide shows up in the chat window while the Keynote program launches to provide you with the proper controls to click through the rest of the slides in the presentation.

When the show is over, close the window to end the iChat Theater session.

If you’ve done nothing but chat in iChat, you haven’t even scratched the surface. The iChat→Preferences dialog box gives you plenty of additional control. A few examples:

General pane. If you turn on Show status in menu bar, you bring the iChat menulet to your menu bar. It lets you change your iChat status (Available, Away, and so on), whether you’re in iChat or not.

And if you turn off “When I quit iChat, set my status to Offline,” then quitting iChat doesn’t actually log you out. When someone wants a chat with you, iChat opens automatically.

The General pane is also where you tell iChat what to do when you’re temporarily away from the Mac. You can have it automatically reply to chat invitations with your personalized “I’m not here” message. When you come back to the Mac or wake it up from sleep, you can have iChat flip your status from Away to Available all by itself.

Accounts pane. If you have more than one AIM, Jabber, or MobileMe account, you can switch among them here. Your passwords are conveniently saved in your Mac OS X Keychain.

Messages pane. The Messages preference panel lets you design your chat windows—the background color, word balloon color, and typeface and size of text you type.

If you want to set a special background image for your chats, you can do that as well—just drag a graphics file into the chat preview box on this pane. You can revert to a white background by choosing View→Clear Background.

Tip

Here’s a little tweak, right on the Messages pane, that nobody ever mentions: the preference setting called “Watch for my name in incoming messages.” It alerts you anytime anyone, in any of the open chats, types your name, even if you’re doing something else on the Mac. (As in, “Casey, are you there? Casey!? CASEY!!”)

Alerts pane. Here, you can choose how iChat responds to various events. For example, it can play a sound, bounce its Dock icon, or say something out loud whenever you log in, log out, receive new messages, or run an AppleScript, as described earlier in this chapter.

Audio/Video pane. This is where you get a preview of your own camera’s output, limit the amount of bandwidth (signal-hogging data) the camera uses (a troubleshooting step), and specify that you want iChat to fire up automatically whenever you switch on the camera.