Right out of the box, Mac OS X comes with a healthy assortment of about 50 freebies: programs for sending email, writing documents, doing math, even playing games. Some have been around for years. Others, though, have been given extreme makeovers in Snow Leopard. They’re designed not only to show off some of Mac OS X’s most dramatic technologies, but also to let you get real work done without having to invest in additional software.

A broad assortment of programs sits in the Applications folder in the main hard drive window, and another couple dozen less frequently used apps await in the Applications→Utilities folder.

This chapter guides you through every item in your new software library, one program at a time. (Of course, your Applications list may vary. Apple might have blessed your particular Mac model with some bonus programs, or you may have downloaded or installed some on your own.)

Tip

A reminder: You can jump straight to the Applications folder in the Finder by pressing Shift-⌘-A (the shortcut for Go→Applications), or by clicking the Applications folder icon in the Sidebar. You might consider adding the Application folder’s icon to the Dock, too, so you can access it no matter what program you’re in. Shift-⌘-U (or Go→Utilities) takes you, of course, to the Utilities folder.

The Address Book is a database that stores names, addresses, email addresses, phone numbers, and other contact information. See To Do List: Mail/iCal Joint Custody.

This software-robot program is introduced in Chapter 7.

The Calculator is much more than a simple four-function memory calculator. It can also act as a scientific calculator for students and scientists, a conversion calculator for metric and U.S. measures, and even a currency calculator for world travelers.

The little Calculator widget in the Dashboard is quicker to open, but the standalone Calculator program is far more powerful. For example:

Calculator has three modes: Basic, Advanced, and Programmer (Figure 10-1). Switch among them by choosing from the View menu (or pressing ⌘-1 for Basic, ⌘-2 for Advanced, or ⌘-3 for Programmer).

You can operate Calculator by clicking the onscreen buttons, but it’s much easier to press the corresponding number and symbol keys on your keyboard.

As you go, you can make Calculator speak each key you press. The Mac’s voice ensures that you don’t mistype as you keep your eyes on the receipts in front of you, typing by touch.

Just choose Speech→Speak Button Pressed to turn this feature on or off. (You choose which voice does the talking in the Speech panel of System Preferences.)

Tip

If you have a pre-2008 laptop, you probably have an embedded numeric keypad, superimposed on the right side of the keyboard and labeled on the keys in a different color ink. When you press the Fn key in the lower-left corner of the keyboard, typing these keys produces the numbers instead of the letters. (You can also press the NumLock key to stay in number mode, so you don’t have to keep pressing Fn.)

Press the C key to clear the calculator display.

Once you’ve calculated a result, you can copy it (using Edit→Copy, or ⌘-C) and paste it directly into another program.

Calculator even offers Reverse Polish Notation (RPN), a system of entering numbers that’s popular with some mathematicians, programmers, and engineers, because it lets them omit parentheses. Choose View→RPN to turn it on and off.

Tip

How cool is this? In most programs, you don’t need Calculator or even a Dashboard widget. Just highlight an equation (like 56*32.1-517) right in your document, and press ⌘-Shift-8. Presto—Mac OS X replaces the equation with the right answer. This trick works in TextEdit, Mail, Entourage, FileMaker, and many other programs.

And if you ever find that it doesn’t work, remember that the Spotlight menu is now a calculator, too. Type or paste an equation into the Spotlight search box; instantly, the answer appears in the results menu.

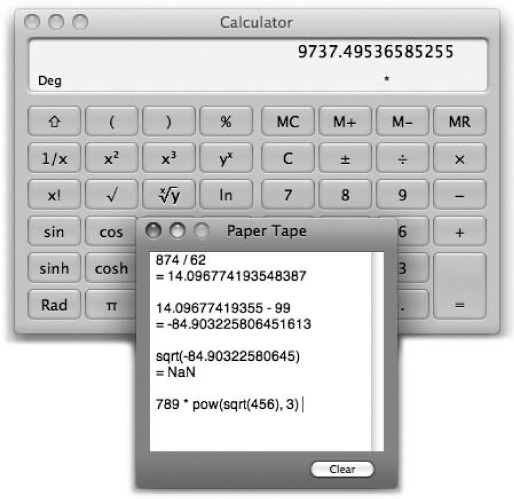

Figure 10-1. The Calculator program offers a four-function Basic mode, a full-blown scientific calculator mode, and a programmer’s calculator (shown here, and capable of hex, octal, decimal, and binary notation). The first two modes offer a “paper tape” feature (View→Show Paper Tape) that lets you correct errors made way back in a calculation. To edit one of the numbers on the paper tape, drag through it, retype, and then click Recalculate Totals. You can also save the tape as a text file by choosing File→Save Tape As, or print it by selecting File→Print Tape.

Calculator is more than a calculator; it’s also a conversion program. No matter what units you’re trying to convert—meters, grams, inches, miles per hour, money—Calculator is ready.

Now, the truth is, the Units Converter widget in Dashboard is simpler and better than this older Calculator feature. But if you’ve already got Calculator open, here’s the drill:

Clear the calculator (for example, type the letter C on your keyboard). Type in the starting measurement.

To convert 48 degrees Celsius to Fahrenheit, for example, type 48.

From the Convert menu, choose the kind of conversion you want.

In this case, choose Temperature. When you’re done choosing, a dialog box appears.

Use the pop-up menus to specify which units you want to convert to and from.

To convert Celsius to Fahrenheit, choose Celsius from the first pop-up menu, and Fahrenheit from the second.

Click OK.

That’s it. The Calculator displays the result—in degrees Fahrenheit, in this example.

The next time you want to make this kind of calculation, you can skip steps 2, 3, and 4. Instead, just choose your desired conversion from the Convert→Recent Conversions submenu.

Calculator is especially amazing when it comes to currency conversions—from pesos to American dollars, for example—because it actually does its homework. It goes online to download up-to-the-minute currency rates to ensure that the conversion is accurate. (Choose Convert→Update Currency Exchange Rates.)

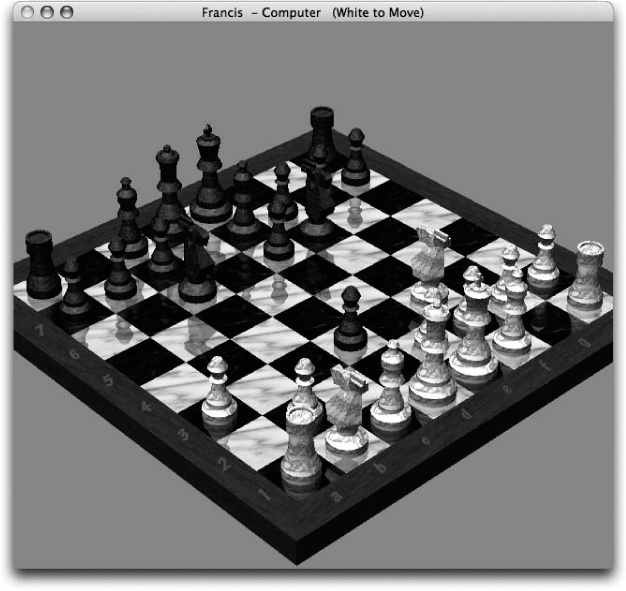

Mac OS X comes with only one game, but it’s a beauty (Figure 10-2). It’s a traditional chess game played on a gorgeously rendered board with a set of realistic 3-D pieces.

Note

The program is actually a sophisticated Unix-based chess program, Sjeng Chess, that Apple packaged up in a new wrapper.

When you launch Chess, you’re presented with a fresh, new game that’s set up in Human vs. Computer mode—meaning that you, the Human (light-colored pieces) get to play against the Computer (your Mac, on the dark side). Drag the chess piece of your choice into position on the board, and the game is afoot.

If you choose Game→New Game, however, you’re offered a pop-up menu with choices like Human vs. Computer, Human vs. Human, and so on. If you switch the pop-up menu to Computer vs. Human, you and your Mac trade places; the Mac takes the white side of the board and opens the game with the first move, and you play the black side.

Tip

The same New Game dialog box also offers a pop-up menu called Variant, which offers three other chess-like games: Crazyhouse, Suicide, and Losers. The Chess help screens (choose Help→Chess Help, and then click “Starting a new chess game”) explain these variations.

Figure 10-2. You don’t have to be terribly exact about grabbing the chess pieces when it’s time to make your move. Just click anywhere within a piece’s current square to drag it into a new position on the board (shown here in its Marble incarnation). And how did this chess board get rotated like this? Because you can grab a corner of the board and rotate it in 3-D space. Cool!

On some night when the video store is closed and you’re desperate for entertainment, you might also want to try the Computer vs. Computer option, which pits your Mac against itself. Pour yourself a beer, open a bag of chips, and settle in to watch until someone—either the Mac or the Mac—gains victory.

Choose Chess→Preferences to find some useful controls like these:

Style. Apple has gone nuts with the computer-generated materials options in this program. (Is it a coincidence that Steve Jobs is also the CEO of Pixar, the computer-animation company?)

In any case, you can choose all kinds of wacky materials for the look of your game board—Wood, Metal, Marble, or Grass (?)—and for your playing pieces (Wood, Metal, Marble, or Fur).

Computer Plays. Use this slider to determine how frustrated you want to get when trying to win at Chess. The farther you drag the slider toward the Stronger side, the more calculations the computer runs before making its next move—and, thus, the harder it gets for you to outthink it. At the Faster setting, Chess won’t spend more than 5 seconds ruminating over possible moves. Drag the slider all the way to the right, however, and the program may analyze each move for as long as 10 fun-filled hours. This hardest setting, of course, makes it all but impossible to win a game (which may stretch on for a week or more anyway).

Choosing the Faster setting makes it only mildly impossible.

Speech. The two checkboxes here let you play Chess using the Mac’s built-in voice-recognition features, telling your chess pieces where to go instead of dragging them, and listening to the Mac tell you which moves it’s making. Speech Recognition has the details.

Tip

If your Chess-playing skills are less than optimal, the Moves menu will become your fast friend. The three commands tucked away there undo your last move (great for recovering from a blunder), suggest a move when you don’t have a clue what to do next, and display your opponent’s previous move (in case you failed to notice what the computer just did).

You can choose Game→Save Game to save any game in progress, so you can resume it later.

To analyze the moves making up a game, use the Game Log command, which displays the history of your game, move by move. A typical move would be recorded as “Nb8 – c6,” meaning the knight on the b8 square moved to the c6 square. Equipped with a Chess list document, you could re-create an entire game, move by move.

Dashboard, described in Chapter 5, is a true-blue, double-clickable application. As a result, you can remove its icon from your Dock, if you like.

For word nerds everywhere, the Dictionary (and thesaurus) is a blessing—a handy way to look up word definitions, pronunciations, and synonyms. To be precise, Snow Leopard comes with electronic versions of multiple reference works in one:

The complete Oxford American Writers Thesaurus.

A dictionary of Apple terms, from “A/UX” to “widget.” (Apparently there aren’t any Apple terms that begin with X, Y, or Z.)

Wikipedia. Of course, this famous open-source, citizen-created encyclopedia isn’t actually on your Mac. All Dictionary does is give you an easy way to search the online version, and display the results right in the comfy Dictionary window.

A Japanese dictionary, thesaurus, and Japanese-to-English translation dictionary.

Tip

You don’t ordinarily see the Japanese reference books. You have to turn them on in Dictionary→ Preferences.

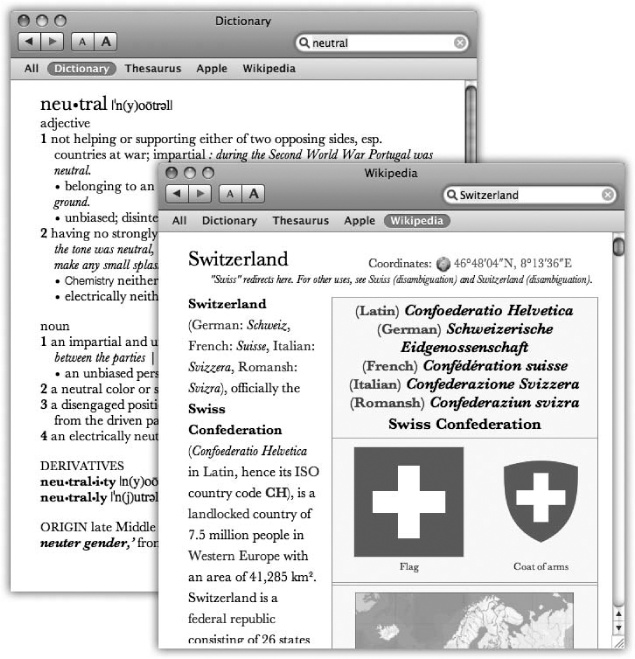

Figure 10-3. When you open the Dictionary, it generally assumes that you want a word’s definition (top left). If you prefer to see the Wikipedia entry (lower right) at startup time instead, for example, choose Dictionary→Preferences—and drag Wikipedia upward so that it precedes New Oxford American Dictionary. That’s all there is to it!

Mac OS X also comes with about a million ways to look up a word:

Double-click the Dictionary icon. You get the window shown at top in Figure 10-3. As you type into the Spotlight-y search box, you home in on matching words; double-click a word, or highlight it and press Return, to view a full, typographically elegant definition, complete with sample sentence and pronunciation guide.

Tip

And if you don’t recognize a word in the definition, click that word to look up its definition. (Each word turns blue and underlined when you point to it, as a reminder.) You can then double-click again in that definition—and on, and on, and on.

(You can then use the History menu, the

and

and  buttons on the toolbar, or the ⌘-[ and ⌘-] keystrokes to go back and forward in your chain of lookups.)

buttons on the toolbar, or the ⌘-[ and ⌘-] keystrokes to go back and forward in your chain of lookups.)It’s worth exploring the Dictionary→Preferences dialog box, by the way. There, you can choose U.S. or British pronunciations and adjust the font size.

Press F12. Yes, the Dictionary is one of the widgets in Dashboard (Calculator).

Control-click (right-click) a highlighted word in a Cocoa program. From the shortcut menu, choose Look Up in Dictionary. The Dictionary program opens to that word. (Or visit the Dictionary’s Preferences box and choose “Open Dictionary panel.” Now you get a panel that pops out of the highlighted word instead.)

Use the dict:// prefix in your Web browser. This might sound a little odd, but it’s actually ultra-convenient, because it puts the dictionary right where you’re most likely to need it: on the Web.

Turns out that you can look up a word (for example, preposterous) by typing dict://preposterous into the address bar—the spot where you’d normally type http://www.whatever. When you hit Return, Mac OS X opens Dictionary automatically and presents the search results from all of its resources (dictionary, thesaurus, Apple terms, and Wikipedia).

Point to a word in a basic Mac program, and then press Control-⌘-D. That keystroke makes the definition panel sprout right from the word you were pointing to. (The advantage here, of course, is that you don’t have to highlight the word first.) “Basic Mac program,” in this case, means one of the Apple standards: Mail, Stickies, Safari, TextEdit, iChat, and so on.

Highlight a word in a basic Mac program, and then press Shift-⌘-L. That’s the keyboard shortcut for the Look Up in Dictionary Service (see Chapter 7).

The front matter of the Oxford American Dictionary (the reference pages at the beginning) is here, too. It includes some delicious writers’ tools, including guides to spelling, grammar, capitalization, punctuation, chemical elements, and clichés, along with the full text of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. Just choose Go→Front/Back Matter—and marvel that your Mac comes with a built-in college English course.

DVD Player, your Mac’s built-in movie projector, is described in Chapter 11.

For details on this font-management program, see Chapter 14.

This full-screen multimedia playback program is now part of Mac OS X; it’s available even on Macs that didn’t come with Apple’s slim white remote control. Chapter 15 has details.

GarageBand, Apple’s do-it-yourself music construction kit, isn’t actually part of Mac OS X. If you have a copy, that’s because it’s part of the iLife suite that comes on every new Mac (along with iMovie, iPhoto, and iWeb). There’s a crash-course bonus chapter on this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com.

In many ways, iCal is not so different from those “Hunks of the Midwest Police Stations” paper calendars people leave hanging on the walls for months past their natural life span.

But iCal offers several advantages over paper calendars. For example:

It can automate the process of entering repeating events, such as weekly staff meetings or gym workouts.

iCal can give you a gentle nudge (with a sound, a dialog box, or even an email) when an important appointment is approaching.

iCal can share information with your Address Book program, with Mail, with your iPod or iPhone, with other Macs, with “published” calendars on the Internet, or with a Palm organizer. Some of these features require one of those MobileMe accounts described in Chapter 18. But iCal also works fine on a single Mac, even without an Internet connection.

iCal can subscribe to other people’s calendars. For example, you can subscribe to your spouse’s calendar, thereby finding out when you’ve been committed to after-dinner drinks on the night of the big game on TV.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: You can now tell iCal to display your online calendars from Google and Yahoo—without requiring hacks, add-on software, or weeks of fasting.

iCal can now display your company’s Exchange calendar, too. For those details, see Chapter 8.

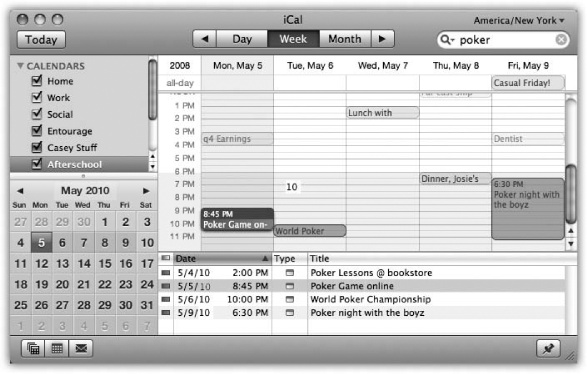

When you open iCal, you see something like Figure 10-4. By clicking one of the View buttons above the calendar, you can switch among these views:

Day shows the appointments for a single day in the main calendar area, broken down by time slot.

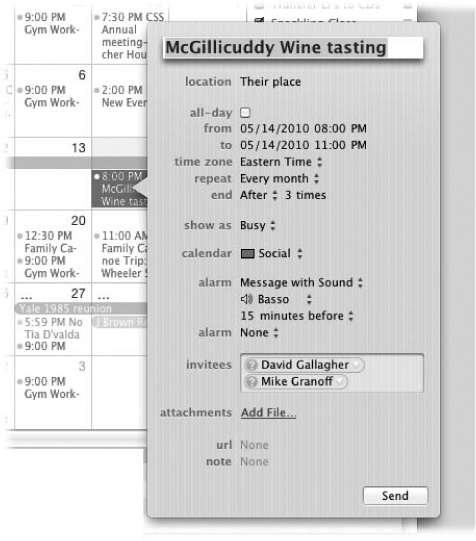

Figure 10-4. In iCal, the miniature navigation calendar (lower left) provides an overview of adjacent months. You can jump to a different week or day by clicking the

and

and  buttons, and then clicking within the numbers. Double-click any appointment to see the summary balloon shown here. You can hide the To Do list either by using the View→Hide To Dos command or by clicking the thumbtack button in the lower-right corner.

buttons, and then clicking within the numbers. Double-click any appointment to see the summary balloon shown here. You can hide the To Do list either by using the View→Hide To Dos command or by clicking the thumbtack button in the lower-right corner.If you choose iCal→Preferences, you can specify what hours constitute a workday. This is ideal both for those annoying power-life people who get up at 5 a.m. for two hours of calisthenics and the more reasonable people who sleep until 11 a.m.

Week fills the main display area with seven columns, reflecting the current week. (You can establish a five-day work week instead in iCal→Preferences.)

Month shows the entire month that contains the current date (Figure 10-4). Double-click a date number to open the day view for that date.

To save space, iCal generally doesn’t show you the times of your appointments in Month view. If you’d like to see them anyway, choose iCal→Preferences, click General, and turn on “Show time in month view.”

Tip

If your mouse has a scroll wheel, you can use it to great advantage in iCal. For example, when entering a date, turning the wheel lets you jump forward or backward in time. It also lets you change the priority level of a To Do item you’re entering, or even tweak the time zone as you’re setting it.

In any of the views, double-click an appointment to see more about it. The very first time you do that, you get the summary balloon shown in Figure 10-4. If you want to make changes, you can then click the Edit button to open a more detailed view.

Tip

In Week or Day view, iCal sprouts a handy horizontal line that shows where you are in time right now. (Look in the hours-of-the-day “ruler” down the left side of the window to see this line’s little red bulb.) A nice touch, and a handy visual aid that can tell you at a glance when you’re already late for something.

The basic iCal calendar is easy to figure out. After all, with the exception of one unfortunate Gregorian incident, we’ve been using calendars successfully for centuries.

Even so, there are two ways to record a new appointment: a simple way and a more flexible, elaborate way.

You can quickly record an appointment using any of several techniques, listed here in order of decreasing efficiency:

In Month view, double-click a blank spot on the date you want. A pop-up info balloon appears (Figure 10-5), where you type the details for your new appointment.

In Day or Week view, double-click the starting time to create a one-hour appointment. Or drag vertically through the time slots that represent the appointment’s duration. Either way, type the event’s name inside the newly created colored box.

Choose File→New Event (or press ⌘-N). A new appointment appears on the currently selected day, regardless of the current view.

In any view, Control-click or right-click a date and choose New Event from the shortcut menu.

Unless you use the drag-over-hours method, a new event believes itself to be one hour long. But in Day or Week view, you can adjust its duration by dragging the bottom edge vertically. Drag the dark top bar up or down to adjust the start time.

In many cases, that’s all there is to it. You have just specified the day, time, and title of the appointment. Now you can get on with your life.

The information balloon shown in Figure 10-5 appears when you double-click a Month-view square, or double-click any existing appointment.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: After you’ve already edited an appointment once, the full info balloon is a little more effort to open; double-clicking an event produces only the summary balloon shown in Figure 10-4.

The short way to open the full balloon is to click the appointment and then press ⌘-E (which is short for Edit→Edit Event). The long way is to double-click the appointment to get the summary balloon and then click Edit inside it.

But the best solution to this problem is to avail yourself of the new Snow Leopard option in iCal→Preferences→Advanced. It’s the checkbox called “Open events in separate windows.” Now when you double-click an appointment in iCal, it opens immediately into a full-size Details window, saving you that intermediate step forever. (You can close the window with a quick ⌘-W.)

For each appointment, you can Tab your way to the following information areas:

subject. That’s the large, bold type at the top—the name of your appointment. For example, you might type Fly to Phoenix.

location. This field makes a lot of sense; if you think about it, almost everyone needs to record where a meeting is to take place. You might type a reminder for yourself like My place, a specific address like 212 East 23, or some other helpful information like a contact phone number or flight number.

all-day. An “all-day” event, of course, refers to something that has no specific time of day associated with it: a holiday, a birthday, a book deadline. When you turn on this box, you see the name of the appointment jump to the top of the iCal screen, in the area reserved for this kind of thing.

from, to. You can adjust the times shown here by typing, clicking buttons, or both. Press Tab to jump from one setting to another, and from there to the hours and minutes of the starting time.

For example, start by clicking the hour, then increase or decrease this number either by pressing ↑ and ↓ or by typing a number. Press Tab to highlight the minutes and repeat the arrow-buttons-or-keys business. Finally, press Tab to highlight the AM/PM indicator, and type either A or P—or press ↑ or ↓—to change it, if necessary.

time zone. This option appears only after you choose iCal→Preferences→Advanced and then turn on “Turn on time zone support.” And you would do that only if you plan to be traveling on the day this appointment comes to pass.

Once you’ve done that, a time zone pop-up menu appears. It starts out with “America/New York” (or whatever your Mac’s usual time zone is); if you choose Other, a tiny world map appears. Click the time zone that represents where you’ll be when this appointment comes due. From the shortcut menu, choose the major city that’s in the same zone you’ll be in.

Tip

The time zone pop-up menu remembers each new city you select. The next time you travel to a city you’ve visited before, you won’t have to do that clicking-the-world-map business.

Now, when you arrive in the distant city, use the time zone pop-up menu at the top-right corner of the iCal window to tell iCal where you are. You’ll see all of iCal’s appointments jump, like magic, to their correct new time slots.

repeat. The pop-up menu here contains common options for recurring events: every day, every week, and so on. It starts out saying None.

Once you’ve made a selection, you get an end pop-up menu that lets you specify when this event should stop repeating. If you choose “Never,” you’re stuck seeing this event repeating on your calendar until the end of time (a good choice for recording, say, your anniversary, especially if your spouse might be consulting the same calendar). You can also turn on “After” (a certain number of times), which is a useful option for car and mortgage payments. And if you choose “On date,” you can specify the date that the repetitions come to an end; use this option to indicate the last day of school, for example.

“Custom” lets you specify repeat schedules like “First Monday of the month” or “Every two weeks.”

show as (busy/free/tentative/“out of office”). This little item, new in Snow Leopard, shows up only if you’ve subscribed to an Internet-based calendar (in geek-speak, a CalDAV server) or you’ve hooked up to your company’s Exchange calendar (Chapter 8). It communicates to your colleagues when you might be available for meetings.

Note

If your calendar comes from a CalDAV server, then your only options are “busy” and “free.” The factory setting for most appointments is “busy,” but for all-day events it’s “free.” Which is logical; just because it’s International Gecko Appreciation Day doesn’t mean you’re not available for meetings (rats!).

You might think: “Well, duh—if I’ve got something on the calendar, then I’m obviously busy!” But not necessarily. Some iCal entries might just be placeholders, reminders to self, TV shows you wanted to watch, appointments you’d be willing to change—not things that would necessarily render you unavailable if a better invitation should come along.

calendar. A calendar, in iCal’s confusing terminology, is a subset—a category—into which you can place various appointments. You can create one for yourself, another for family-only events, another for book-club appointments, and so on. Later, you’ll be able to hide and show these categories at will, adding or removing them from iCal with a single click. Details begin on Searching for Events.

alarm. This pop-up menu tells iCal how to notify you when a certain appointment is about to begin. iCal can send any of four kinds of flags to get your attention. It can display a message on the screen (with a sound, if you like), send you an email, run a script of the sort described in Chapter 7, or open a file on your hard drive. (You could use this unusual option to ensure that you don’t forget a work deadline by flinging the relevant document open in front of your face at the eleventh hour.)

Once you’ve specified an alarm mechanism, a new pop-up menu appears to let you specify how much advance notice you want for this particular appointment. If it’s a TV show you’d like to watch, you might set up a reminder five minutes before airtime. If it’s a birthday, you might set up a two-day warning to give yourself enough time to buy a present. In fact, you can set up more than one alarm for the same appointment, each with its own advance-warning interval.

Tip

In iCal→Preferences→Advanced, you can opt to prevent alarms from going off—a good checkbox to inspect before you give a presentation in front of 2,000 people. There’s also an option to stifle alarms except when iCal is open. In other words, just quitting iCal is enough to ensure that those alarms won’t interrupt whatever you’re doing.

invitees. If the appointment is a meeting or some other gathering, you can type the participants’ names here. If a name is already in your Address Book program, iCal proposes autocompleting the name for you.

If you separate several names with commas, iCal automatically turns each into a shaded oval pop-up button. You can click it for a pop-up menu of commands like Remove Attendee and Send Email. (That last option appears only if the person in your Address Book has an email address, or if you typed a name with an email address in brackets, like this: Chris Smith <chris@yahoo.com>.)

Once you’ve specified some attendees, a Send button appears in the Info box. If you click it, iCal fires up Mail and prepares ready-to-send messages, each with an iCal.ics attachment: a calendar-program invitation file. See the box on Inviting Guests.

attachments. This new option lets you fasten a file to the appointment. It can be anything: a photo of the person you’re meeting, a document to finish by that deadline, the song that was playing the first time you met this person—whatever.

url. A URL is a Uniform Resource Locator, better known as a Web address, like www.apple.com. If there’s a URL relevant to this appointment, by all means type it here. Type more than one, if it’ll help you; just be sure to separate them with a comma.

note. Here’s your chance to customize your calendar event. You can type, paste, or drag any text you like in the note area—driving directions, contact phone numbers, a call history, or whatever.

Your newly scheduled event now shows up on the calendar, complete with the color coding that corresponds to the calendar category you’ve assigned.

Once you’ve entrusted your agenda to iCal, you can start putting it to work. iCal is only too pleased to remind you (via pop-up messages) of your events, reschedule them, print them out, and so on. Here are a few of the possibilities:

To edit a calendar event’s details, you have to open its Info balloon, as described in Figure 10-5.

And if you want to change only an appointment’s “calendar” category, Control-click (or right-click) anywhere on the appointment and, from the resulting shortcut menu, choose the category you want.

In both cases, you bypass the need to open the Info balloon.

You don’t have to bother with this if all you want to do is reschedule an event, however, as described next.

If an event in your life gets rescheduled, you can drag an appointment block vertically in a day- or week-view column to make it later or earlier the same day, or horizontally to another date in any view. (If you reschedule a recurring event, iCal asks if you want to change only this occurrence, or this and all future ones.)

If something is postponed for, say, a month or two, you’re in trouble, since you can’t drag an appointment beyond its month window. You have no choice but to open the Info balloon and edit the starting and ending dates or times—or just cut and paste the event to a different date.

If a scheduled meeting becomes shorter or your lunch hour becomes a lunch hour-and-a-half (in your dreams), changing the length of the representative calendar event is as easy as dragging the bottom border of its block in any column view (see Figure 10-6).

To commit your calendar to paper, choose File→Print, or press ⌘-P. The resulting Print dialog box lets you include only a certain range of dates, only events on certain calendars, with or without To Do lists or mini-month calendars, and so on.

You should recognize the oval text box at the top of the iCal screen immediately: It’s almost identical to the Spotlight box. This search box is designed to let you hide all appointments except those matching what you type into it. Figure 10-7 has the details.

Just as iTunes has playlists that let you organize songs into subsets and iPhoto has albums that let you organize photos into subsets, iCal has calendars that let you organize appointments into subsets. They can be anything you like. One person might have calendars called Home, Work, and TV Reminders. Another might have Me, Spouse ’n’ Me, and Whole Family. A small business could have categories called Deductible Travel, R&D, and R&R.

To create a calendar, double-click any white space in the Calendar list (below the existing calendars), or click the  button at the lower-left corner of the iCal window. Type a name that defines the category in your mind.

button at the lower-left corner of the iCal window. Type a name that defines the category in your mind.

Tip

Click a calendar name before you create an appointment. That way, the appointment will already belong to the correct calendar.

To change the color-coding of your category, Control-click (right-click) its name; from the shortcut menu, choose Get Info. The Calendar Info box appears. Here, you can change the name, color, or description of this category—or turn off alarms for this category.

You assign an appointment to one of these categories using the pop-up menu on its Info balloon, or by Control-clicking (right-clicking) an event and choosing a calendar name from the shortcut menu. After that, you can hide or show an entire category of appointments at once just by turning on or off the appropriate checkbox in the Calendars list.

Tip

iCal also has calendar groups: calendar containers, like folders, that consolidate the appointments from several other calendars. Super-calendars like this make it easier to manage, hide, show, print, and search subsets of your appointments.

To create a calendar group, choose File→New Calendar Group. Name the resulting item in the Calendar list; for the most part, it behaves like any other calendar. Drag other calendar names onto it to include them. Click the flippy triangle to hide or show the component calendars.

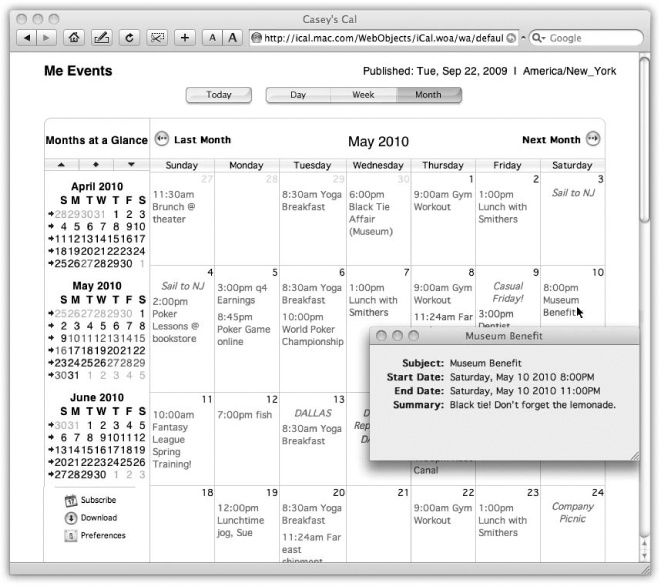

One of iCal’s best features is its ability to post your calendar on the Web, so that other people (or you, on a different computer) can subscribe to it, which adds your appointments to their calendars. If you have a MobileMe account, then anyone with a Web browser can also view your calendar, right online.

For example, you might use this feature to post the meeting schedule for a club that you manage, or to share the agenda for a series of upcoming financial meetings that all of your coworkers will need to consult.

Begin by clicking the calendar category you want in the left-side list. (iCal can publish only one calendar category at a time. If you want to publish more than one calendar, create a calendar group.)

Then choose Calendar→Publish; the dialog box shown at top in Figure 10-8 appears. This is where you customize how your saved calendar is going to look and work. You can even turn on “Publish changes automatically,” so whenever you edit the calendar, iCal connects to the Internet and updates the calendar automatically. (Otherwise, you’ll have to choose Calendar→Refresh every time you want to update the Web copy.)

Figure 10-8. If you click “Publish on: MobileMe,” iCal posts the actual, viewable calendar on the Web, as shown in Figure 10-9. If you choose “a private server,” you have the freedom to upload the calendar to your own personal Web site, if it’s WebDAV-compatible (ask your Web-hosting company). Your fans will be able to download the calendar, but not view it online.

While you’re at it, you can include To Do items, notes, and even alarms with the published calendar.

When you click Publish, your Mac connects to the Web and then shows you the Web address (the URL) of the finished page, complete with a Send Mail button that lets you fire the URL off to your colleagues.

If somebody else has published a calendar, you can subscribe to it by choosing Calendar→Subscribe. In the Subscribe to Calendar dialog box, type in the Internet address you received from the person who published the calendar. Alternatively, click the Subscribe button on any iCal Web page (Figure 10-9, lower left).

Figure 10-9. Your calendar is now live on the Web. Your visitors can control the view, switch dates, double-click an appointment for details—it’s like iCal Live!

Either way, you can also specify how often you want your own copy to be updated (assuming you have a full-time Internet connection) and whether or not you want to be bothered with the publisher’s alarms and notes.

When it’s all over, you see a new “calendar” category in your left-side list, representing the published appointments.

Tip

Want to try it out right now? Visit www.icalshare.com, a worldwide clearinghouse for sets of iCal appointments. You can subscribe to calendars for shuttle launches, Mac trade shows, National Hockey League teams, NASCAR races, soccer matches, the Iron Chef and Survivor TV shows, holidays, and much more. You’ll never suffer from empty-calendar syndrome again.

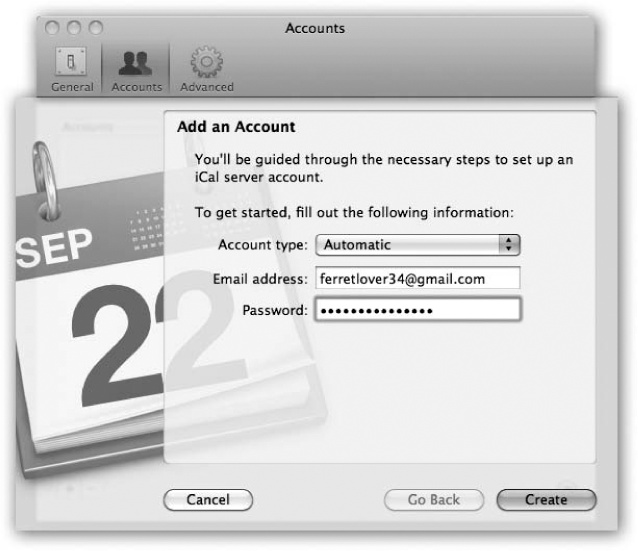

If you maintain a calendar online—at www.google.com/calendar or http://calendar.yahoo.com, for example, you may take particular pleasure in discovering how easy it is to bring those appointments into iCal. It’s one handy way to keep, for example, a husband’s and wife’s appointments visible on each other’s calendars.

Setting this up is ridiculously easy in Snow Leopard (see Figure 10-10).

Figure 10-10. To bring your Yahoo or Google calendar into iCal for free twoway syncing, choose iCal→Preferences→Accounts. Click the  button below the list. Enter your Google or Yahoo address (for example, ferretlover34@gmail.com) and password, as shown here. Click Create.

button below the list. Enter your Google or Yahoo address (for example, ferretlover34@gmail.com) and password, as shown here. Click Create.

In a minute or so, you’ll see all your Google or Yahoo appointments show up in iCal. (Each Web calendar has its own heading in the left-side list.) Better yet: It’s a two-way sync; changes you make to these events in iCal show up on the Web, too.

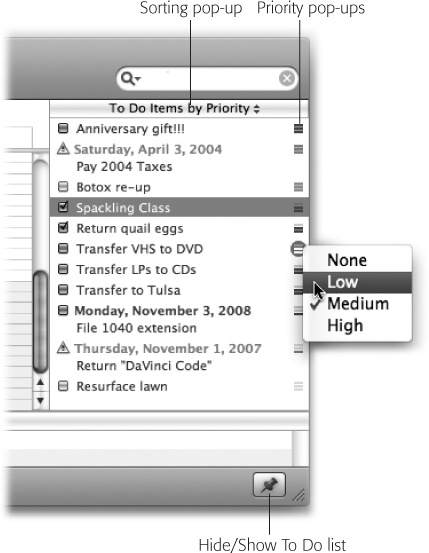

iCal’s Tasks feature lets you make a To Do list and shepherds you along by giving you gentle reminders, if you so desire (Figure 10-11). What’s nice is that Mac OS X maintains a single To Do list, which shows up in both iCal and Mail.

Figure 10-11. Using the To Do Info balloon, you can give your note a priority, a calendar (category), or a due date. Tasks that come due won’t show up on the calendar itself, but a little exclamation point triangle appears in the To Do Items list.

To see the list, click the pushpin button at the lower-right corner of the iCal screen. Add a new task by double-clicking a blank spot in the list that appears, or by choosing File→New To Do. After the new item appears, you can type to name it.

To change the task’s priority, alarm, repeating pattern, and so on, double-click it. An Info balloon appears, just as it does for an appointment.

Tip

Actually, there’s a faster way to change a To Do item’s priority—click the tiny three-line ribbed handle at the right side of the list. Turns out it’s a shortcut menu that lets you choose Low, Medium, or High priority (or None).

To sort the list (by priority, for example), use the pop-up menu at the top of the To Do list. To delete a task, click it and then press the Delete key.

Tip

You have lots of control over what happens to a task listing after you check it off. In iCal→Preferences, for example, you can make tasks auto-hide or auto-delete themselves after, say, a week or a month. (And if you asked them to auto-hide themselves, you can make them reappear temporarily using the Show All Completed Items command in the pop-up menu at the top of the To Do list.)

Details on the iChat instant-messaging program can be found in Chapter 21.

iDVD isn’t really part of Mac OS X, although you probably have a copy of it; as part of the iLife software suite, iDVD comes free on every new Mac. iDVD lets you turn your digital photos or camcorder movies into DVDs that work on almost any DVD player, complete with menus, slideshow controls, and other navigation features. iDVD handles the technology; you control the style.

For a primer on iDVD, see the free, downloadable iLife appendix to this chapter, available on this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com.

This unsung little program, completely redesigned in Snow Leopard, was originally designed to download pictures from a camera and then process them automatically (turning them into a Web page, scaling them to emailable size, and so on). Of course, after Image Capture’s birth, iPhoto came along, generally blowing its predecessor out of the water.

Even so, Apple includes Image Capture with Mac OS X for these reasons:

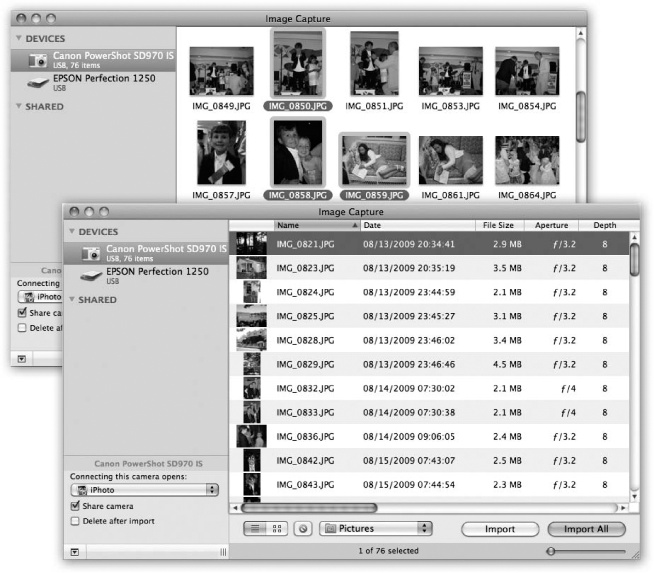

Image Capture is a smaller, faster app for downloading all or only some pictures from your camera (Figure 10-12). iPhoto can do that nowadays, but sometimes that’s like using a bulldozer to get out a splinter.

Image Capture can grab images from Mac OS X–compatible scanners, too, not just digital cameras.

Image Capture can download your sounds (like voice notes) from a digital still camera; iPhoto can’t.

Image Capture can share your camera or scanner on the network.

Image Capture can turn a compatible digital camera into a Webcam, broadcasting whatever it “sees” to anyone on your office network—or the whole Internet. Similarly, it can share a scanner with all the networked Macs in your office.

You can open Image Capture in either of two ways: You can simply double-click its icon in your Applications folder, or you can set it up to open automatically whenever you connect a digital camera and turn it on. To set up that arrangement, open Image Capture manually. Using the “Connecting this camera opens:” pop-up menu, choose Image Capture.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: For the first time, you can now specify which program on your Mac opens when you connect a camera independently for each camera. For example, you can set it up so that when you connect your fancy SLR camera, Aperture opens; when you connect your spouse’s pocket camera, iPhoto opens; and when you connect your iPhone, Image Capture opens, so you can quickly grab the best shots and email them directly.

Figure 10-12. Top: In some ways, Image Capture is like a mini iPhoto; use the slider in the lower right to change the thumbnail sizes. Use the “Delete after import” checkbox (lower-left) if you want your camera’s card erased after you slurp in its photos. You can choose the individual pictures you want to download, rotate selected shots (using the buttons at the top), or delete shots from the camera. Bottom: List view gives you a table of details about the photos to be imported.

Once Image Capture is open, it looks like Figure 10-12. Its controls, once buried in menus and Preferences dialog boxes, have, in Snow Leopard, all been brought out to the main window so they’re readily available.

When you connect your camera, cellphone, or scanner, its name appears in the leftside list. To begin, click it. After a moment, Image Capture displays all the photos on the camera’s card, in either list view or icon view (your choice).

Use this pop-up menu to specify what happens to the imported pictures. Image Capture proposes putting photos, sounds, and movies from the camera into your Home folder’s Pictures, Music, and Movies folders, respectively. But you can specify any folder (choose Other from the pop-up menu).

Furthermore, there are some other very cool options here:

iPhoto. Neat that you can direct photos from your camera to iPhoto via Image Capture. Might come in handy when you didn’t expect to want to load photos into your permanent collection, but change your mind when you actually look them over in Image Capture.

Preview opens the fresh pictures in Preview so you can get a better (and bigger) look at them.

Mail sends the pix directly into the Mac’s email program, which can be very handy when the whole point of getting the photos off the camera is to send them off to friends.

Build web page creates an actual, and very attractive, Web page of your downloaded shots. Against a dark gray background, you get thumbnail images of the pictures in a Web page document called index.html. Just click one of the small images to view it at full size, exactly as your Web site visitors will be able to do once this page is actually on the Web. (Getting it online is up to you.)

Note

Image Capture puts the Web page files in a Home folder→Pictures→Webpage on [today’s date and time] folder. It contains the graphics files incorporated into this HTML document; you can post the whole thing on your Web site, if you like.

Image Capture automatically opens up this page in your Web browser, proud of its work.

MakePDF. What is MakePDF? It’s a little Snow Leopard app you didn’t even know you had.

When you choose this option, you wind up with what looks like a Preview window, showing thumbnails of your photos. If you choose Save right now, you’ll get a beautiful full-color PDF of the selected photos, ready to print out and then, presumably, to cut apart with scissors or a paper cutter. But if you use the Layout menu, you can choose different layouts for your photos: 3 x 5, 4 x 6, 8 x 10, and so on.

And what if a photo doesn’t precisely fit the proportions you’ve selected? The Crop commands in the Layout menu (for example, “Crop to 4 x 6”) center each photo within the specified shape, and then trim the outer borders if necessary. The Fit commands, on the other hand, shrink the photo as necessary to fit into the specified dimensions, sometimes leaving blank white margins.

Other. The beauty of the Image Capture system is that people can, in theory, write additional processing scripts. Once you’ve written or downloaded them, drop them into your System→Library→Image Capture→Automatic Tasks folder. Then enjoy their presence in the newly enhanced Import To pop-up menu.

Tip

You can set up Image Capture to download everything on the camera automatically when you connect it. No muss, no options, no fuss.

To do that, connect the camera. Click its name in the Devices list. Then, from the “Connecting this camera opens” pop-up menu, choose AutoImporter. From now on, Image Capture downloads all pictures on the camera each time it’s connected.

When the downloading process is complete, a little green checkmark appears on the thumbnail of each imported photo.

Clicking Import All, of course, begins the process of downloading the photos to the folder you’ve selected. A progress dialog box appears, showing you thumbnail images of each picture that flies down the wire.

If you prefer to import only some photos, select them first. (In icon view, you click and Shift-click to select a bunch of consecutive photos, and ⌘-click to add individual photos to the selection. In icon view, you can only click and Shift- click to select individual photos.) Then click Import.

You’re sitting in front of Macintosh #1, but the digital camera or scanner is connected to Macintosh #2 downstairs, elsewhere on the network. What’s a Mac fan to do?

All right, that situation may not exactly be the scourge of modern computing. Still, downloading pictures from a camera attached to a different computer can occasionally be useful. In a graphics studio, for example, when a photographer comes back from the field, camera brimming with fresh shots, he can hook up the camera to his Mac so that his editor can peruse the pictures on hers, while he heads home for a shower.

To share your camera on the network, hook it up; then turn on the Share Camera checkbox (lower left). (This trick works with scanners, too.)

On the other Mac (it, too, must be running Snow Leopard), open Image Capture. The shared camera’s name appears in the Shared list at left. Click the camera’s name. Now you see the photos on that camera, much like what’s shown in Figure 10-12; you can view and download the photos exactly as though the camera’s connected to your Mac.

A few newer camera models can actually be controlled from the Mac. You can trigger the shutter button from your laptop, for example, without touching the camera and risking jiggling it. (Studio photographers often use this trick.)

Note

The Webcamable cameras include recent Canon PowerShot models, some Kodaks, and several Nikon digital SLRs. In Snow Leopard, you can’t operate a camera like this from across the network or Internet—only when the camera is actually attached to your Mac. Sorry, babysittercam fans.

To set this up, connect the camera. Choose File→Take Picture. (If the command is dimmed, then your camera doesn’t offer this remote-control feature.)

If you do have this feature, a new dialog box appears, showing a preview of what the camera sees. It also offers options that let you control when pictures are taken: manually (when you press the space bar or Return key) or automatically at regular intervals.

If you own a scanner, chances are good that you won’t be needing whatever special scanning software came with it. Instead, Mac OS X gives you two programs that can operate any standard scanner: Image Capture and Preview. In fact, the available controls are identical in both programs.

To scan in Image Capture, turn on your scanner and click its name in the left-side list. Put your photos or documents into the scanner.

Note

You can share a scanner on the network, if you like, by turning on the Share button in the lower-left corner of the window. That’s sort of a weird option, though, for two reasons. First, what do you gain by sitting somewhere else in the building? Do you really want to yell or call up to whoever’s sitting next to the scanner: “OK! Put in the next photo!”?

Second, don’t forget that anyone else on the network will be able to see whatever you’re scanning. Embarrassment may result. You’ve been warned.

Now you have a couple of decisions to make:

Separate and straighten? If you turn on “Detect separate items,” Snow Leopard will perform a nifty little stunt indeed: It will check to see if you’ve put multiple items onto the scanner glass, like several small photos. (It looks for rectangular images surrounded by empty white space, so if the photos are overlapping, this feature won’t work.)

If it finds multiple items, Snow Leopard automatically straightens them, compensating for haphazard placement on the glass, and then saves them as individual files.

Where to file. Use the “Scan to” pop-up menu to specify where you want the newly scanned image files to land—in the Pictures folder, for example. You have some other cool options beyond sticking the scans in a folder; you can use the Web page, PDF, iPhoto, and other options described on Import To:.

Once you’ve put a document onto it or into it, click Scan. The scanner heaves to life. After a moment, you see on the screen what’s on the glass. It’s simultaneously been sent to the folder (or post-processing task) you requested using the “Scan to” popup menu.

As you can see, Apple has tried to make basic scanning as simple as possible: one click. That idiotproof method gives you very few options, however.

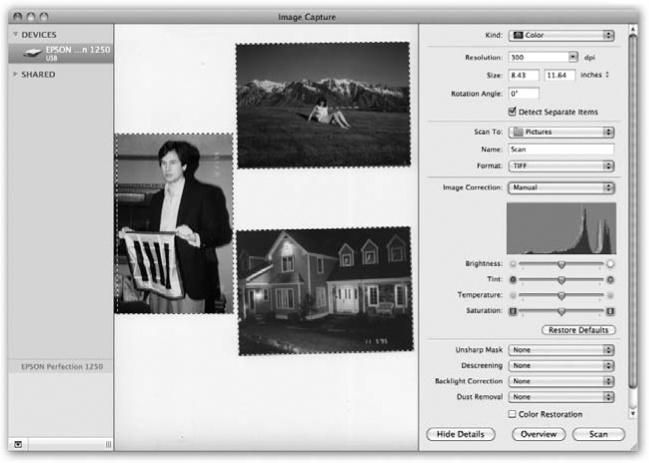

If you click Show Details before you scan, though, you get a special panel on the right side of the window that’s filled with useful scanning controls (Figure 10-13).

Figure 10-13. When you use the Show Details button, you get a new panel on the right, where you can specify all the tweaky details for the scan you’re about to make: resolution, size, and so on. See how the three photos have individual dotted lines around them? That’s because “Detect Separate Items” is turned on. These will be scanned into three separate files.

Here are some of the most useful options:

Resolution. This is the number of tiny scanned dots per inch. 300 is about right for something you plan to print out; 72 is standard for graphics that will be viewed on the screen, like images on a Web page.

Name. Here, specify how you want each image file named when it lands on your hard drive. If it says Scan, then the files will be called Scan 1, Scan 2, and so on.

Format. Usually, the file format for scanned graphics is TIFF. That’s a very high-res format that’s ideal if you’re scanning precious photos for posterity. But if these images are bound for the Web, you might want to choose JPEG instead; that’s the standard Web format.

Image Correction. If you choose Manual from this pop-up menu, then, incredibly, you’ll be treated to a whole expando-panel of color correction tools: brightness, tint, saturation, a histogram, and so on.

Unsharp Mask. This option sharpens up any slightly “soft” photos after scanning.

Descreening. Sometimes, when you scan printed photos from a newspaper or magazine, you get a moiré effect: a weird rippling pattern in the scanned image that wasn’t in the original. This option is supposed to get rid of that ugliness.

Dust Removal. Dust is a common problem in scanned images. This option attempts to eliminate the specks of dust that might mar a photo.

Opening the Details panel has another handy benefit, too: It lets you scan only a portion of what’s on the scanner glass.

Once you’ve put the document or photo into the scanner, click Overview. Snow Leopard does a quick pass and displays on the screen whatever’s on the glass. You’ll see a dotted-line rectangle around the entire scanned image—unless you’d turned on “Detect separate images,” in which case you see a dotted-line rectangle around each item on the glass.

You can adjust these dotted-line rectangles around until you’ve enclosed precisely the portion of the image you want scanned. For example, drag the rectangles’ corner handles to resize them; drag inside the rectangles to move them; drag the right end of the line inside the rectangle to rotate it; preview the rotation by pressing Control and Option.

Finally, when you think you’ve got the selection rectangle(s) correctly positioned, click Scan to trigger the actual scan.

Note

These instructions apply to the most common kind of scanner—the flatbed scanner. If you have a scanner with a document feeder—a tray or slot that sucks in one paper document after another from a stack—the instructions are only slightly different.

You may, for example, see a Mode or Scan Mode pop-up menu; if so, choose Document Feeder. You’ll want to use the Show Details option described above. You may also be offered a Duplex command (meaning, “scan both sides of the paper”—not all scanners can do this).

Here’s another pair of the iLife apps—not really part of Mac OS X, but kicking around on your Mac because iLife comes with all new Macs.

A basic getting-started chapter for these programs awaits, in free downloadable PDF form, on this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com.

See Chapter 6 for details on this file-synchronization software.

iTunes is Apple’s beloved digital music–library program. Chapter 11 tells all.

See Chapter 19 for the whole story.

It may be goofy, it may be pointless, but the Photo Booth program is a bigger time drain than Solitaire, the Web, and Dancing with the Stars put together.

It’s a match made in heaven for Macs that have a tiny video camera above the screen, but you can also use it with a camcorder, iSight, or Webcam. Just be sure the camera is turned on and hooked up before you open Photo Booth. (Photo Booth doesn’t even open if your Mac doesn’t have some kind of camera.)

Open this program and then peer into the camera. Photo Booth acts like a digital mirror, showing whatever the camera sees—that is, you.

But then click the Effects button. You enter a world of special visual effects—and we’re talking very special. Some make you look like a pinhead, or bulbous, or like a Siamese twin; others simulate Andy Warhol paintings, fisheye lenses, and charcoal sketches (Figure 10-14). In the Snow Leopard version, in fact, there are four pages of effects, nine previews on a page; click the left or right arrow buttons, or press ⌘-← or ⌘-→, to see them all. (The last two pages hold backdrop effects, described below.)

Some of the effects have sliders that govern their intensity; you’ll see them appear when you click the preview.

When you find an effect that looks appealing (or unappealing, depending on your goals here), click the camera button, or press ⌘-T. You see and hear a 3-second countdown, and then snap!—your screen flashes white to add illumination, and the resulting photo appears on your screen. Its thumbnail joins the collection at the bottom.

If you click the 4-Up button identified in Figure 10-14, then when you click the Camera icon (or press ⌘-T), the 3-2-1 countdown begins, and then Photo Booth snaps four consecutive photos in 2 seconds. You can exploit the timing just the way you would in a real photo booth—make four different expressions, horse around, whatever.

The result is a single graphic with four panes, kind of like what you get at a shopping-mall photo booth. (In Photo Booth, they appear rakishly assembled at an angle; but when you export the image, they appear straight, like panes of a window.) Its icon plops into the row of thumbnails at the bottom of the window, just like the single still photos.

Photo Booth can also record videos, complete with those wacky distortion effects. Click the third icon below the screen, the Movie icon (Figure 10-14), and then click the camera button (or press ⌘-T). You get the 3-2-1 countdown—but this time, Photo Booth records a video, with sound, until you click the Stop button or the hard drive is full, whichever comes first. (The little digital counter at left reminds you that you’re still filming.) When it’s over, the movie’s icon appears in the row of thumbnails, ready to play or export.

Or choose Edit→Auto Flip New Photos if you want Photo Booth to do the flipping for you from now on.

To look at a photo or movie you’ve captured, click its thumbnail in the scrolling row at the bottom of the screen. (To return to camera mode, click the camera button.)

Fortunately, these masterpieces of goofiness and distortion aren’t locked in Photo Booth forever. You can share them with your adoring public in any of four ways:

Drag a thumbnail out of the window to your desktop. Or use the File→Reveal in Finder command to see the actual picture or movie files.

Click Mail to send the photo or movie as an outgoing attachment in Mail.

Click the iPhoto button to import the shot or movie into iPhoto.

Click Account Picture to make this photo represent you on the Login screen.

Tip

You can choose one frame of a Photo Booth movie to represent you. As the movie plays, click the Pause button, then drag the scroll-bar handle to freeze the action on the frame you want. Then click Account Picture.

Similarly, you can click your favorite one pane of a 4-up image to serve as your account photo—it expands to fill the Photo Booth screen—before clicking Account Picture.

And speaking of interesting headshots: If you export a 4-up image and choose it as your buddy icon in iChat (Chapter 21), you’ll get an animated buddy icon. That is, your tiny icon cycles among the four images, creating a crude sort of animation. It’s sort of annoying, actually, but all the kids are doing it.

As you set off on your Photo Booth adventures, a note of caution: Keep it away from children. They won’t move from Photo Booth for the next 12 years.

Preview is Mac OS X’s scanning software, graphics viewer, fax viewer, and PDF reader. It’s always been teeming with features that most Mac owners never even knew were there—but in Snow Leopard, it’s been given even more horsepower.

Preview can import pictures directly from a digital camera (or iPhone), meaning that there are now three Snow Leopard apps that can perform that duty. (iPhoto and Image Capture are the other two.) It’s sometimes handy to use Preview for this purpose, though, because it has some great tools for photos: color-correction controls, size/ resolution options, format conversion, and so on.

The actual importing process, though, is exactly like using Image Capture for this purpose. Connect your camera, choose File→Import from [Your Camera’s Name], and carry on as described on Import To:.

Preview can also operate a scanner, auto-straighten the scanned images, and export them as PDF files, JPEG graphics, and so on.

This, too, is exactly like using Image Capture to operate your scanner. Only the first step is different. Open Preview, choose File→Import from Scanner→[Your Scanner’s Name], and proceed as described on Image Capture as Spycam.

Clearly, Apple saved some time by reusing some code.

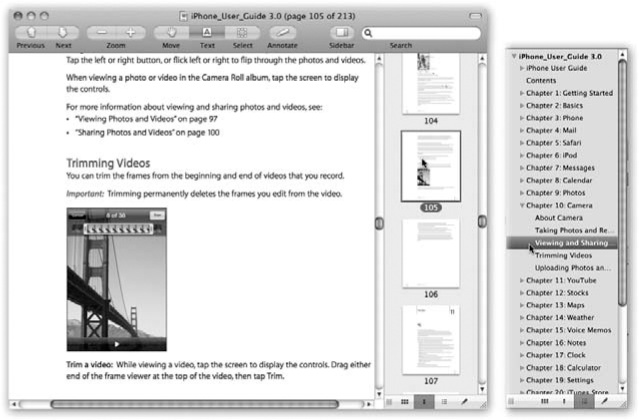

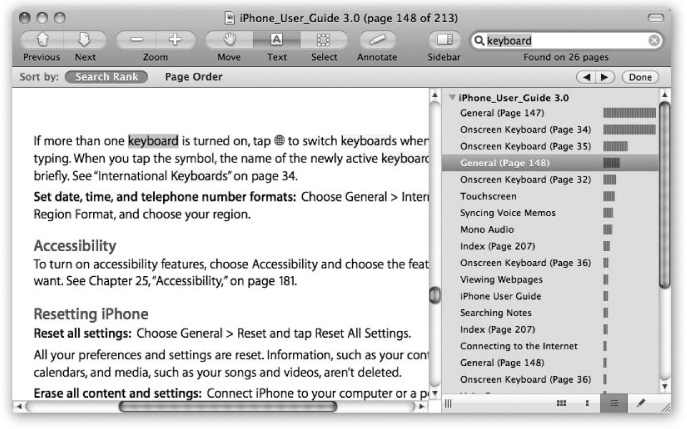

One hallmark of Preview is its effortless handling of multiples: multiple fax pages, multiple PDF files, batches of photos, and so on. The key to understanding the possibilities is mastering the Sidebar, shown in Figure 10-15. The idea is that these thumbnails let you navigate pages or graphics without having to open a rat’s nest of individual windows.

Tip

You can drag these thumbnails from one Preview window’s Sidebar into another. That’s a great way to mix and match pages from different PDF documents into a single new one, for example.

To hide or show the Sidebar, press Shift-⌘-D (or click the Sidebar button in the toolbar, or use the View→Sidebar submenu). Once the Sidebar is open, the four tiny icons at the bottom let you choose among four views:

Tip

You can also change among these four views using the View→Sidebar submenu—or by pressing the keyboard shortcuts Option-⌘-1, 2, 3, and 4.

Contact Sheet. When you choose this view, the main window scrolls away, leaving you with a full screen of thumbnail miniatures. It’s like a light table where you can look over all the photos or PDF pages at once. Make them bigger or smaller using the slider in the lower left.

Thumbnails. This standard view (Figure 10-15, left) offers a scrolling vertical list of miniature pages or photos. Click one to see it at full size in the main window. Make the thumbnails larger or smaller by dragging the small grabber handle at the bottom of the main window/Sidebar dividing line.

Table of Contents. If you’re looking over photos, this option turns the Sidebar into a scrolling list of their names. If you’ve opened a group of PDFs all at once, you see a list of them. Or, if you have a PDF that contains chapter headings, you see them listed in the Sidebar as, yes, a table of contents.

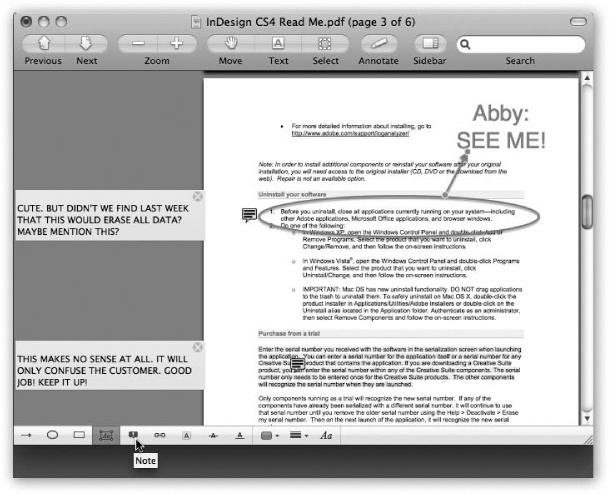

Annotations. Later in this section, you can read about all the ways you can mark up a PDF document with notes, underlines, highlighting, and so on. This Sidebar view displays a list of all such annotations, so you can skip directly from one to the next, responding to your editor’s worthless sniping far more efficiently.

Preview, as you’re probably starting to figure out, is surprisingly versatile. It can display and manipulate pictures saved in a wide variety of formats, including common graphics formats like JPEG, TIFF, PICT, and GIF; less commonly used formats like BMP, PNG, SGI, TGA, and MacPaint; and even Photoshop, EPS, and PDF graphics. You can even open animated GIFs by adding a Play button to the toolbar, as described on The Toolbar.

If you highlight a group of image files in the Finder and open them all at once (for example, by pressing ⌘-O), Preview opens the first one, but lists the thumbnails of the whole group in the Sidebar. You can walk through them with the ↑ and ↓ keys, or you can choose View→Slideshow (Shift-⌘-F) to open a full-screen slideshow. (You have to click through the pictures manually, though.)

To crop graphics in Preview, drag across the part of the graphic that you want to keep. To redraw, drag the round handles on the dotted rectangle; or, to proceed with the crop, choose Tools→Crop. (The keyboard shortcut is ⌘-K.)

If you don’t think you’ll ever need the original again, save the document. Otherwise, choose File→Save As to spin the cropped image out as a separate file, preserving the original in the process.

Preview is no Photoshop, but it’s getting closer every year. Let us count the ways:

Choose Tools→Inspector. A floating palette appears. Click the first tab to see the photo’s name, when it was taken, its pixel dimensions, and so on. Click the second one for even more geeky photo details, including camera settings like the lens type, ISO setting, focus mode, whether the flash was on, and so on. The third tab lets you add keywords, so you’ll be able to search for this image later using Spotlight. (The fourth is for PDF documents only, not photos; it lets you add annotations.)

Choose Tools→Adjust Color. A translucent, floating color-adjustment palette appears, teeming with sliders for brightness, contrast, exposure, saturation (color intensity), temperature and tint (color cast), sharpness, and more. See Figure 10-16.

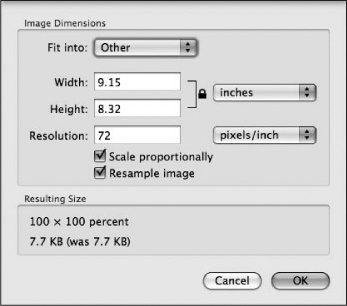

Choose Tools→Adjust Size. This command lets you adjust a photo’s resolution, which comes in handy a lot. For example, you can scale an unwieldy 10-megapixel, gazillion-by-gazillion-pixel shot down to a nice 640 x 480 JPEG that’s small enough to send by email. Or you can shrink a photo down so it fits within a desktop window, for use as a window background.

Figure 10-16. Humble little Preview has grown up into a big, strong mini-Photoshop. You can really fix up a photo if you know what you’re doing, using these sliders. Or you can just click the Auto Levels button. It sets all those sliders for you, which generally does an amazing job of making almost any photo look better.

There’s not much to it. Type in the new print dimensions you want for the photo, in inches or whatever units you choose from the pop-up menu. If you like, you can also change the resolution (the number of pixels per inch) by editing the Resolution box.

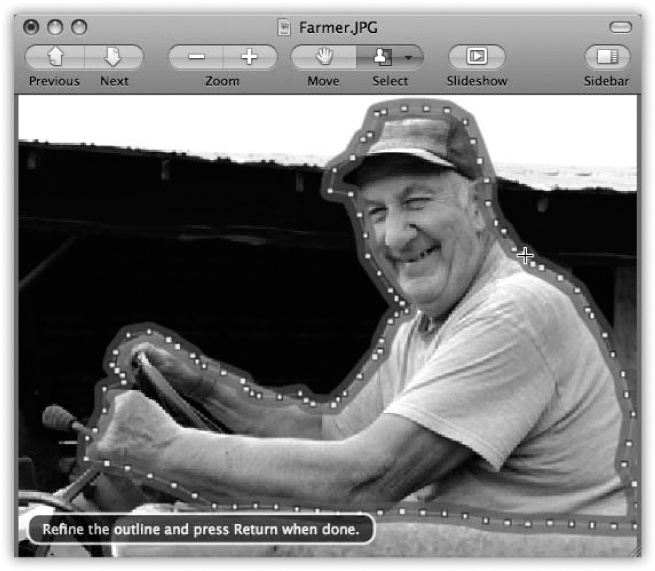

Here’s a Photoshoppy feature you would never, ever expect to find in a simple viewer like Preview: You can extract a person (or anything, really) from its background. That’s handy when you want to clip yourself out of a group shot to use as your iChat portrait, when you want to paste somebody into a new background, or when you break up with someone and want them out of your photos.

Solid backgrounds. If the background is simple—mostly a solid color or two—you can do this job quickly. Start by making sure the toolbar is visible (⌘-B). From the Select pop-up menu, choose Instant Alpha.

This feature is extremely weird, but here goes: Click the first background color you want to eliminate. Preview automatically dims out all the pixels that match the color you clicked. Click again in another area to add more of the background to the dimmed patch.

Actually, if you click and drag a tiny distance, you’ll see sensitivity-percentage numbers appear next to your cursor. They indicate that the more you drag, the more you’re expanding the selection to colors close to the one you clicked. The proper technique, then, isn’t click-click-click; it’s drag-drag-drag.

If you accidentally eat into part of the person or thing that you want to keep, Option-drag across it to remove those colors from the selection.

When it looks like you’ve successfully isolated the subject from the background, press Return or Enter. There it is, ready to cut or copy.

Complex backgrounds. If the background isn’t primarily solid colors, the process is a little trickier. Again, start by making sure the toolbar is visible (⌘-B). From the Select pop-up menu, choose Extract Shape.

Now carefully trace the person or thing that you’ll want to extract. Preview marks your tracing with a fat pink line (Figure 10-17).

You can trace straight lines by releasing your mouse button and clicking the next endpoint. Preview draws a straight line between your last drag and the click.

Tip

If the pink outline is too thick or too thin for your tastes, hold down the  or

or  keys to make the entire line grow thinner or thicker.

keys to make the entire line grow thinner or thicker.

Don’t worry if you’re not exact; you’ll be able to refine the outline later. (Zoom in for tight corners by pressing ⌘-+.) Continue until you’ve made a complete closed loop. Or just double-click to say, “Connect where I am now with where I started.”

(Hit Esc to erase the line and start over—or give up.)

When you’re done, the outline sprouts dotted handles, as shown in Figure 10-17. You can drag them to refine the border’s edges. When the outline looks close enough, press Return or Enter.

Figure 10-17. After your outline is complete, the fat pink outline sprouts a trail of tiny handles. Drag them to refine the edge.

Now you enter the Instant Alpha mode described above. If you see bits of background still showing, dab them with the mouse; they fade into the foggy “not included” area. If you accidentally chopped out a piece of your person, Option-dab. In both cases, Preview includes all pixels of the same color you dabbed, making it easy to remove, for example, a hunk of fabric.

When it all looks good, press Return or Enter. Preview ditches the background, leaving only the outlined person. If you choose File→Save As, you’ll have yourself an empty-background picture, ready to import or paste into another program.

Once you’ve exported the file, congratulate yourself. You’ve just created a graphic with an alpha channel, which, in computer-graphics terms, is a special mask that can be used for transparency or blending. The background that you deleted—the empty white part—appears transparent when you import the graphic into certain graphically sophisticated programs. For example:

iMovie ’08 or ’09. You can drag your exported graphic directly onto a filmstrip in an iMovie project. The white areas of the exported Preview image become transparent, so whatever video is already in the filmstrip plays through it. Great for opening credits or special effects.

Preview. Yes, Preview itself recognizes incoming alpha channels. So after you cut the background out of Photo A, you can select what’s left (press ⌘-A), copy it to the Clipboard (⌘-C), open Photo B, and paste (⌘-V). The visible part of Photo A gets pasted into the background of Photo B.

Photoshop, Photoshop Elements. Of course, these advanced graphics programs recognize alpha channels, too. Paste in your Preview graphic; it appears as a layer, with the existing layers shining through the empty areas.

Tip

Here’s a great way to create a banner or headline for your Web page: Create a big, bold-font text block in TextEdit. Choose File→Print; from the PDF pop-up button, choose Open PDF in Preview.

In Preview, crop the document down, and save it as a PNG-format graphic (because PNG recognizes alpha channels). Then use the Instant Alpha feature to dab out the background and the gaps inside the letters. When you import this image to your Web page, you’ll find a professional-looking text banner that lets your page’s background shine through the empty areas of the lettering.

Preview doesn’t just open all these file formats—it can also convert between most of them. You can pop open some old Mac PICT files and turn them into BMP files for a Windows user, pry open some SGI files created on a Silicon Graphics workstation and turn them into JPEGs for use on your Web site, and so on.

Tip

What’s even cooler is you can open raw PostScript files right into Preview, which converts them into PDF files on the spot. You no longer need a PostScript laser printer to print out high-end diagrams and page layouts that come to you as PostScript files. Thanks to Preview, even an inkjet printer can handle them.

All you have to do is open the file you want to convert and choose File→Save As. In the dialog box that appears, choose the new format for the image using the Format pop-up menu (JPEG, TIFF, PNG, or Photoshop, for example). Finally, click Save to export the file.

Preview is a nearly full-blown equivalent of Acrobat Reader, the free program used by millions to read PDF documents. It lets you search PDF documents, copy text out of them, add comments, fill in forms, click live hyperlinks, add highlighting, circle certain passages, type in notes—features that used to be available only in Adobe’s Acrobat Reader.

Here are the basics:

Use the View→PDF Display submenu to control how the PDF document appears: as two-page spreads; as single scrolling sheets of “paper towel”; with borders that indicate ends of pages; and so on.

Press the space bar to page through a document (add Shift to page upward. The Page Up and Page Down keys do the same thing.)

Tip

Some PDF documents include a table of contents, which you’ll see in Preview’s Sidebar, complete with flippy triangles that denote major topics or chapter headings (Figure 10-19, right). You can use the ↑ and ↓ keys alone to walk through these chapter headings, and then expand one that looks good by pressing the → key. Collapse it again with the ← key.

In other words, you expand and collapse flippy triangles in Preview just as you do in a Finder list view.

Figure 10-18. The new Annotation strip at the bottom edge of the Preview window makes it incredibly easy to add different kinds of annotations. This strip appears when you click the Annotate button on the top toolbar, or whenever you’ve added a marking or a note manually using the Tools→Annotate submenu. Click the button you want, then drag diagonally to define a rectangle, oval, arrow, or link. Or click to place a Note icon and edit that note in the left margin. You can drag or delete the annotation’s little icon, or adjust its look using the Tools→Inspector palette.

Bookmark your place by choosing Bookmarks→Add Bookmark (⌘-D); type a clever name. In the future, you’ll be able to return to that spot by choosing its name from the Bookmarks menu.

You can type in notes, add clickable links (to Web addresses or other spots in the document), or use circles, arrows, rectangles, strikethrough, underlining, or yellow highlighting to draw your readers’ attention to certain sections, as shown in Figure 10-18.

Tip

Preview ordinarily stamps each text note with your name and the date. If you’d rather not have that info added, choose Preview→Preferences, click PDF, and then turn off “Add name to annotations.”

These remain living, editable entities even after the document is saved and reopened. These are full-blown Acrobat annotations; they’ll show up when your PDF document is opened by Acrobat Reader or even on Windows PCs.

Turn smoothing on or off to improve readability. To find the on/off switch, choose Preview→Preferences, and click the PDF tab. Turn on “Smooth line art and text.” (Though antialiased text generally looks great, it’s sometimes easier to read very small type with antialiasing turned off. It’s a little jagged, but clearer nonetheless.)

Turn on View→PDF Display→Single Page (or Double Page) Continuous to scroll through multipage PDF documents in one continuous stream, instead of jumping from page to page when you use the scroll bars.

To find a word or phrase somewhere in a PDF document, press ⌘-F (or choose Edit→Find→Find) to open the Find box—or just type into the

box at the top of the Sidebar, if it’s open. Proceed as shown in Figure 10-19.

box at the top of the Sidebar, if it’s open. Proceed as shown in Figure 10-19.If you want to copy some text out of a PDF document—for pasting into a word processor, for example, where you can edit it—click the Text tool (the letter A on the toolbar) or choose Tools→Text Tool. Now you can drag through some text and then choose Edit→Copy, just as though the PDF document were a Web page. You can even drag across page boundaries.

Note

Snow Leopard Spots: Ordinarily, dragging across text selects the text from one edge of the page to the other, even if the PDF document is laid out in columns. But in Snow Leopard, Preview is a bit smarter. It can tell if you’re trying to get the text in only one column, and highlights just that part automatically. (The old Preview could do this, too, but you had to press Option as you dragged.)

You can save a single page from a PDF as a TIFF file to use it in other graphics, word processing, or page layout programs that might not directly recognize PDF.

To extract a page, use the usual File→Save As command, making sure to choose the new file format from the pop-up menu. (If you choose a format like Photoshop or JPEG, Preview converts only the currently selected page of your PDF document. That’s because there’s no such thing as a multipage Photoshop or JPEG graphic. But you already knew that.)

Add keywords to a graphic or PDF (choose Tools→Show Inspector, click the

tab, click the

tab, click the  button). Later, you’ll be able to call up these documents with a quick Spotlight search for those details.

button). Later, you’ll be able to call up these documents with a quick Spotlight search for those details.

You can have hours of fun with Preview’s toolbar. Exactly as with the Finder toolbar, you can customize it (by choosing View→Customize Toolbar—or by Option-⌘-clicking the upper-right toolbar button), rearrange its icons (by ⌘-dragging them sideways), and remove icons (by ⌘-dragging them downward).

There’s a lot to say about QuickTime player, but it’s all in Chapter 15.

Apple’s Web browser harbors enough tips and tricks lurking inside to last you a lifetime. Details in Chapter 20.

Stickies creates virtual Post-it notes that you can stick anywhere on your screen—a triumphant software answer to the thousands of people who stick notes on the edges of their actual monitors. Like the Stickies widget in Dashboard, you can open this program with a keystroke (highlight some text, then press Shift-⌘-Y)—but it’s a lot more powerful.

You can use Stickies to type quick notes and to-do items, paste in Web addresses or phone numbers you need to remember, or store any other little scraps and snippets of text you come across. Your electronic Post-it notes show up whenever the Stickies program is running (Figure 10-20).

Figure 10-20. In the old days of the Mac, the notes you created with Stickies were text-only, singlefont deals. Today, however, you can use a mix of fonts, text colors, and styles within each note. You can even paste in graphics, sounds, and movies (like PICT, GIF, JPEG, QuickTime, AIFF, whole PDF files, and so on), creating the world’s most elaborate reminders and to-do lists.

The first time you launch Stickies, a few sample notes appear automatically, describing some of the program’s features. You can quickly dispose of each sample by clicking the close button in the upper-left corner of each note or by choosing File→Close (⌘-W). Each time you close a note, a dialog box asks if you want to save it. If you click Don’t Save (or press ⌘-D), the note disappears permanently.

To create a new note, choose File→New Note (⌘-N). Then start typing or:

Drag text in from any other program, such as TextEdit, Mail, or Microsoft Word. Or drag text clippings from the desktop directly into your note. You can also drag a PICT, GIF, JPEG, or TIFF file into a note to add a picture. You can even drag a sound or movie in. (A message asks if you’re sure you want to copy the whole whopping QuickTime movie into a little Stickies note.)