Enuresis and Voiding Dysfunction

Jack S. Elder

Normal Voiding and Toilet Training

Fetal voiding occurs by reflex bladder contraction in concert with simultaneous contraction of the bladder and relaxation of the sphincter. Urine storage results from sympathetic and pudendal nerve-mediated inhibition of detrusor contractile activity accompanied by closure of the bladder neck and proximal urethra with increased activity of the external sphincter. The infant has coordinated reflex voiding as often as 15-20 times/day. Over time, bladder capacity increases. In children up to the age of 14 yr, the mean bladder capacity in milliliters is equal to the age + 2 (in years) times 30 (e.g., the bladder capacity of a 6 yr old should be  or 240 mL).

or 240 mL).

At 2-4 yr, the child is developmentally ready to begin toilet training. To achieve conscious bladder control, several conditions must be present: awareness of bladder filling; cortical inhibition (suprapontine modulation) of reflex (unstable) bladder contractions; ability to consciously tighten the external sphincter to prevent incontinence; normal bladder growth; and motivation by the child to stay dry. The transitional phase of voiding refers to the period when children are acquiring bladder control. Females typically acquire bladder control before males, and bowel control typically is achieved before bladder control.

A common condition in children is bladder–bowel dysfunction (BBD) . This term refers to disorders of bladder and/or bowel function. The old term for this condition was dysfunctional elimination syndrome.

Diurnal Incontinence

Daytime incontinence not secondary to neurologic abnormalities is common in children. At age 5 yr, 95% have been dry during the day at some time and 92% are dry consistently. At 7 yr, 96% are dry, although 15% have significant urgency at times. At 12 yr, 99% are dry consistently during the day. The most common causes of daytime incontinence are overactive bladder (urge incontinence) and bladder–bowel dysfunction . Table 558.1 lists the causes of diurnal incontinence in children.

Table 558.1

The patient history should assess the pattern of incontinence, including the frequency of voiding, frequency of day and night urinary leakage, volume of urine lost during incontinent episodes, whether the incontinence is associated with urgency or giggling, whether it occurs after voiding, and whether the incontinence is continuous. In addition, whether the patient has a strong continuous urinary stream and sensation of incomplete bladder emptying should be assessed. A diary of when the child voids and whether the child is wet or dry is helpful. Other urologic problems, such as urinary tract infections (UTIs), vesicoureteral reflux, neurologic disorders, or a family history of renal duplication anomalies, should be assessed. Bowel habits also should be evaluated because incontinence is common in children with constipation and/or encopresis. Diurnal incontinence can occur in children with a history of sexual abuse or following bullying. Physical examination is directed at identifying signs of organic causes of incontinence. Short stature, hypertension, enlarged kidneys and/or bladder, constipation, labial adhesion, ureteral ectopy, back or sacral anomalies (see Fig. 557.4 in Chapter 557 ), and neurologic abnormalities should be documented.

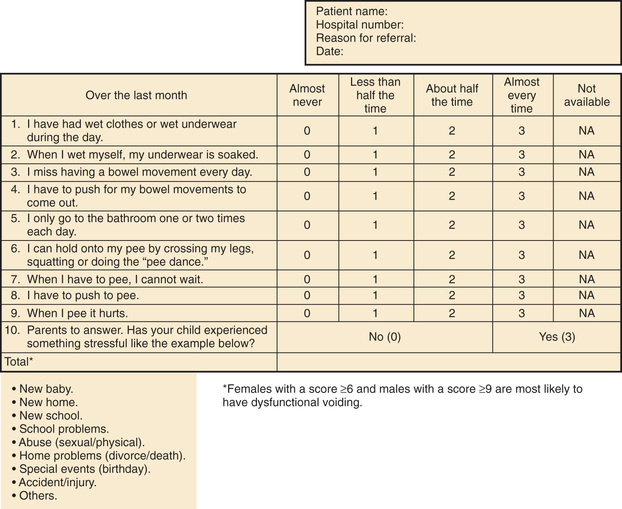

Assessment tools include urinalysis, with culture if indicated; bladder diary (recorded times and volumes voided, whether wet or dry); postvoid residual urine volume (generally obtained by bladder scan); and the Dysfunctional Voiding Symptom Score (Fig. 558.1 ). An alternative to the Dysfunctional Voiding Symptom Score is the Vancouver Nonneurogenic Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction/Dysfunctional Elimination Syndrome questionnaire. This questionnaire is a validated tool that consists of 14 questions scored on a 5-point Likert scale to assess lower urinary tract and bowel dysfunction. In most cases, a uroflow study with electromyography (noninvasive assessment of urinary flow pattern and measurement of external sphincter activity) is indicated. Another item that may be useful in children older than age 5 yr is the Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC) . The Pediatric Symptom Checklist is a brief screening questionnaire consisting of 35 questions that is used by pediatricians and other health professionals to improve the recognition and treatment of psychosocial problems in children.

Bowel function should be assessed also. The Bristol Stool Form Score (Fig. 558.2 ) should be recorded. In addition, the clinician should utilize the Rome III diagnostic criteria, which classify functional gastrointestinal disorders that do not have underlying structural or tissue-based causes. Children 4 yr of age or older are diagnosed as being constipated if they fulfill two or more of the following criteria over a period of 2 mo: two or fewer defecations in the toilet per week, at least one episode of fecal incontinence per week, a history of retentive posturing or excessive volitional stool retention, a history of painful or hard bowel movements, the presence of a large fecal mass in the rectum, and a history of large-diameter stools that obstruct the toilet.

Imaging is performed in children who have significant physical findings, those who have a family history of urinary tract anomalies or UTIs, and those who do not respond to therapy appropriately. A renal/bladder ultrasonogram with or without a voiding cystourethrogram is indicated. Urodynamics should be performed if there is evidence of neurologic disease and may be helpful if empirical therapy is ineffective. If there is any evidence of a neurologic disorder or if there is a sacral abnormality on physical examination, an MRI of the lower spine should be obtained.

Overactive Bladder (Diurnal Urge Syndrome)

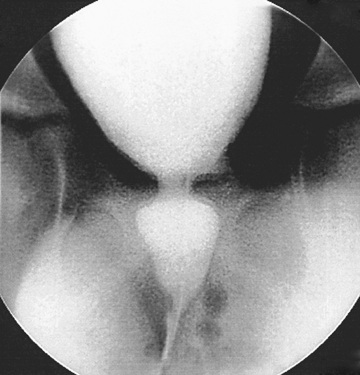

Children with an overactive bladder typically exhibit urinary frequency, urgency, and urge incontinence. Often a female will squat down on her foot to try to prevent incontinence (termed Vincent's curtsy ). The bladder in these children is functionally, but not anatomically, smaller than normal and exhibits strong uninhibited contractions. Approximately 25% of children with nocturnal enuresis also have symptoms of an overactive bladder. Many children indicate they do not feel the need to urinate, even just before they are incontinent. In females, a history of recurrent UTI is common, but incontinence can persist long after infections are brought under control. It is unclear if the voiding dysfunction is a sequela of the UTIs or if the voiding dysfunction predisposes to recurrent UTIs. In some females, voiding cystourethrography shows a dilated urethra (spinning-top deformity , Fig. 558.3 ) and narrowed bladder neck with bladder wall hypertrophy. The urethral finding results from inadequate relaxation of the external urinary sphincter. Constipation is common and should be treated, particularly with any child with Bristol Stool Score 1, 2, or 3.

The overactive bladder nearly always resolves, but the time to resolution is highly variable, occasionally not until the teenage years. Initial therapy is timed voiding, every 1.5-2 hr. Treatment of constipation and UTIs is important. Another treatment is biofeedback, in which children are taught pelvic floor exercises (Kegel exercises), because daily performance of these exercises can reduce or eliminate unstable bladder contractions. Biofeedback often consists of 8-10 1-hr sessions and may include participation with animated computer games. Biofeedback also may include periodic uroflow studies with sphincter electromyography to be certain that the pelvic floor relaxes during voiding, and assessment of postvoid residual urine volume by sonography. Anticholinergic therapy often is helpful if bowel function is normal. Oxybutynin chloride is the only FDA-approved medication in children, but hyoscyamine, tolterodine, trospium, solifenacin, and mirabegron have demonstrated safety in children; these medications reduce bladder overactivity and may help the child achieve dryness. Treatment with an α-adrenergic blocker such as terazosin or doxazosin can aid in bladder emptying by promoting bladder neck relaxation; these medications also have mild anticholinergic properties. If pharmacologic therapy is successful, the dosage should be tapered periodically to determine its continued need. Children who do not respond to therapy should be evaluated urodynamically to rule out other possible forms of bladder or sphincter dysfunction. In refractory cases, other procedures such as sacral nerve stimulation (InterStim), percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation, and intravesical botulinum toxin injection have been effective in children.

If the child has constipation based on the criteria described above, treatment generally is initiated with polyethylene glycol powder, which has been shown to be safe in children and generally more effective than other laxative preparations.

Nonneurogenic Neurogenic Bladder (Hinman Syndrome)

Hinman syndrome is a very serious but uncommon disorder involving failure of the external sphincter to relax during voiding in children without neurologic abnormalities. Children with this syndrome, also called nonneurogenic neurogenic bladder, typically exhibit a staccato stream, day and night wetting, recurrent UTIs, constipation, and encopresis. Evaluation of affected children often reveals vesicoureteral reflux, a trabeculated bladder, and a decreased urinary flow rate with an intermittent pattern (Fig. 558.4 ). In severe cases, hydronephrosis, renal insufficiency, and end-stage renal disease can occur. The pathogenesis of this syndrome is thought to involve learning abnormal voiding habits during toilet training; the syndrome is rarely seen in infants. Urodynamic studies and magnetic resonance imaging of the spine are indicated to rule out a neurologic cause for the bladder dysfunction.

The treatment usually is complex and can include anticholinergic and α-adrenergic blocker therapy, timed voiding, treatment of constipation, behavioral modification, and encouragement of relaxation during voiding. Biofeedback has been used successfully in older children to teach relaxation of the external sphincter. Botulinum toxin injection into the external sphincter can provide temporary sphincteric paralysis and thereby reduce outlet resistance. In severe cases, intermittent catheterization is necessary to ensure bladder emptying. In selected patients, external urinary diversion is necessary to protect the upper urinary tract. These children require long-term treatment and careful follow-up.

Infrequent Voiding (Underactive Bladder)

Infrequent voiding is a common disorder of micturition, usually associated with UTIs. Affected children, usually females, void only twice a day rather than the normal 4-7 times. With bladder overdistention and prolonged retention of urine, bacterial growth can lead to recurrent UTIs. Some of these children are constipated. Some also have occasional episodes of incontinence from overflow or urgency. The disorder is behavioral. If the child has UTIs, treatment includes antibacterial prophylaxis and encouragement of frequent voiding and complete emptying of the bladder by double voiding until a normal pattern of micturition is re-established.

Vaginal Voiding

In females with vaginal voiding, incontinence typically occurs after urination after the female stands up. Usually the volume of urine is 5-10 mL. One of the most common causes is labial adhesion (Fig. 558.5 ). This lesion, typically seen in young females, can be managed either by topical application of estrogen cream to the adhesion or lysis in the office. Some females experience vaginal voiding because they do not separate their legs widely during urination. These females typically are overweight and/or do not pull their underwear down to their ankles when they urinate. Management involves encouraging the female to separate the legs as widely as possible during urination. The most effective way to do this is to have the child sit backward on the toilet seat during micturition.

Other Causes of Incontinence in Females

Ureteral ectopia, usually associated with a duplicated collecting system in females, refers to a ureter that drains outside the bladder, often into the vagina or distal urethra. It can produce urinary incontinence characterized by constant urinary dribbling all day, even though the child voids regularly. Sometimes the urine production from the renal segment drained by the ectopic ureter is small, and urinary drainage is confused with watery vaginal discharge. Children with a history of vaginal discharge or incontinence and an abnormal voiding pattern require careful study. The ectopic orifice usually is difficult to find. On ultrasonography or intravenous urography, one may suspect duplication of the collecting system (Fig. 558.6 ), but the upper collecting system drained by the ectopic ureter usually has poor or delayed function. CT scanning of the kidneys or an MR urogram should demonstrate subtle duplication anomalies. Examination under anesthesia for an ectopic ureteral orifice in the vestibule or the vagina may be necessary (Fig. 558.7 ). Treatment in these cases is either partial nephrectomy, with removal of the upper pole segment of the duplicated kidney and its ureter down to the pelvic brim, or ipsilateral ureteroureterostomy, in which the upper pole ectopic ureter is anastomosed to the normally positioned lower pole ureter. These procedures often are performed by minimally invasive laparoscopy with or without robotic assistance.

Giggle incontinence typically affects females 7-15 yr of age. The incontinence occurs suddenly during giggling, and the entire bladder volume is lost. The pathogenesis is thought to be sudden relaxation of the urinary sphincter. Anticholinergic medication and timed voiding occasionally are effective. The most effective treatment is low-dose methylphenidate, which seems to stabilize the external sphincter.

Total incontinence in females may be secondary to epispadias (see Fig. 556.2 in Chapter 556 ). This condition, which affects only 1 in 480,000 females, is characterized by separation of the pubic symphysis, separation of the right and left sides of the clitoris, and a patulous urethra. Treatment is bladder neck reconstruction; an alternative surgical therapy is placement of an artificial urinary sphincter to repair the incompetent urethra.

A short, incompetent urethra may be associated with certain urogenital sinus malformations. The diagnosis of these malformations requires a high index of suspicion and a careful physical examination of all incontinent females. In these cases, urethral and vaginal reconstruction often restores continence.

Voiding Disorders Without Incontinence

Some children have abrupt onset of severe urinary frequency, voiding as often as every 10-15 min during the day, without dysuria, UTI, daytime incontinence, or nocturia. The most common age for these symptoms to occur is 4-6 yr, after the child is toilet trained, and most are males. This condition is termed the daytime frequency syndrome of childhood, or pollakiuria . The condition is functional; no anatomic problem is detected. Often the symptoms occur just before a child starts kindergarten or if the child is having emotional family stress-related problems. These children should be checked for UTIs, and the clinician should ascertain that the child is emptying the bladder satisfactorily. Another contributing cause is constipation. Occasionally, pinworms cause these symptoms. The condition is self-limited, and symptoms generally resolve within 2-3 mo. Anticholinergic therapy rarely is effective.

Some children have the dysuria–hematuria syndrome, in which the child has dysuria without UTI but with microscopic or total gross hematuria (blood throughout the stream). This condition affects children who are toilet-trained and is often secondary to hypercalciuria. A 24-hr urine sample should be obtained and calcium and creatinine excretion assessed. A 24-hr calcium excretion of > 4 mg/kg is abnormal and deserves treatment with thiazides, because some of these children are at risk for urolithiasis. Terminal hematuria (blood at the end of the stream) occurs in males and typically is secondary to bladder–bowel dysfunction or urethral meatal stenosis. Cystoscopy is not indicated, and the condition usually resolves with treatment for constipation.

Nocturnal Enuresis

By 5 yr of age, 90–95% of children are nearly completely continent during the day, and 80–85% are continent at night. Nocturnal enuresis refers to the occurrence of involuntary voiding at night after 5 yr, the age when volitional control of micturition is expected. Enuresis may be primary (estimated 75–90% of children with enuresis; nocturnal urinary control never achieved) or secondary (10–25%; the child was dry at night for at least a few months and then enuresis developed). Overall, 75% of children with enuresis are wet only at night, and 25% are incontinent day and night. This distinction is important, because children with both forms are more likely to have an abnormality of the urinary tract. Monosymptomatic enuresis is more common than polysymptomatic enuresis (associated urgency, hesitancy, frequency, daytime incontinence).

Epidemiology

Approximately 60% of children with nocturnal enuresis are males. The family history is positive in 50% of cases. Although primary nocturnal enuresis may be polygenetic, candidate genes have been localized to chromosomes 12 and 13. If one parent was enuretic, each child has a 44% risk of enuresis; if both parents were enuretic, each child has a 77% likelihood of enuresis. Nocturnal enuresis without overt daytime voiding symptoms affects up to 20% of children at the age of 5 yr; it ceases spontaneously in approximately 15% of involved children every year thereafter. Its frequency among adults is < 1%.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of primary nocturnal enuresis (normal daytime voiding habits) is multifactorial (Table 558.2 ).

Table 558.2

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

A careful history should be obtained, especially with respect to fluid intake at night and the pattern of nocturnal enuresis. Children with diabetes insipidus (see Chapter 574 ), diabetes mellitus (see Chapter 607 ), and chronic renal disease (see Chapter 550 ) can have a high obligatory urinary output and a compensatory polydipsia. The family should be asked whether the child snores loudly at night. Many children with enuresis sleepwalk or talk in their sleep. A complete physical examination should include palpation of the abdomen and possibly a rectal examination after voiding to assess the possibility of a chronically distended bladder and constipation. The child with nocturnal enuresis should be examined carefully for neurologic and spinal abnormalities. There is an increased incidence of bacteriuria in enuretic females, and, if found, it should be investigated and treated (see Chapter 553 ), although this does not always lead to resolution of bedwetting. A urine sample should be obtained after an overnight fast and evaluated for specific gravity or osmolality to exclude polyuria as a cause of frequency and incontinence and to ascertain that the concentrating ability is normal. The absence of glycosuria should be confirmed. If there are no daytime symptoms, the physical examination and urinalysis are normal, and the urine culture is negative, further evaluation for urinary tract pathology generally is not warranted. A renal ultrasonogram is reasonable in an older child with enuresis or in children who do not respond appropriately to therapy.

Treatment

The best approach to treatment is to reassure the child and parents that the condition is self-limited and to avoid punitive measures that can affect the child's psychological development adversely. Fluid intake should be restricted to 2 oz after 6 or 7 PM . The parents should be certain that the child voids at bedtime. Avoiding extraneous sugar and caffeine after 5 PM also is beneficial. If the child snores and the adenoids are enlarged, referral to an otolaryngologist should be considered, because adenoidectomy can cure the enuresis in some cases.

Active treatment should be avoided in children younger than 6 yr of age, because enuresis is extremely common in younger children. Treatment is more likely to be successful in children approaching puberty compared with younger children. In addition, treatment is most likely to be effective in children who are motivated to stay dry and is less successful in children who are overweight. Treatment should be viewed as a facilitator that requires active participation by the child (e.g., a coach and an athlete).

The simplest initial measure is motivational therapy and includes a star chart for dry nights. Waking children a few hours after they go to sleep to have them void often allows them to awaken dry, although this measure is not curative. Some have recommended that children try holding their urine for longer periods during the day, but there is no evidence that this approach is beneficial. Conditioning therapy involves use of a loud auditory or vibratory alarm attached to a moisture sensor in the underwear. The alarm activates when voiding occurs and is intended to awaken children and alert them to void. This form of therapy has a reported success of 30–60%, although the relapse rate is significant. Often the auditory alarm wakes up other family members and not the enuretic child; persistent use of the alarm for several months often is necessary to determine whether this treatment is effective. Conditioning therapy tends to be most effective in older children. Another form of therapy to which some children respond is self-hypnosis. The primary role of psychological therapy is to help the child deal with enuresis psychologically and help motivate the child to void at night if he or she awakens with a full bladder.

Pharmacologic therapy is intended to treat the symptom of enuresis and thus is regarded as second line and is not curative. Direct comparisons of the moisture alarm with pharmacologic therapy favor the former because of lower relapse rates, although initial response rates are equivalent.

One form of treatment is desmopressin acetate, a synthetic analog of antidiuretic hormone that reduces urine production overnight. This medication is FDA-approved in children and is available as a tablet, with a dosage of 0.2-0.6 mg 2 hr before bedtime. In the past a nasal spray was used, but some children experienced hyponatremia and convulsions with this formulation, and the nasal spray is no longer recommended for nocturnal enuresis. Hyponatremia has not been reported in children using the oral tablets. Fluid restriction at night is important, and the drug should not be used if the child has a systemic illness with vomiting or diarrhea or if the child has polydipsia. Desmopressin acetate is effective in as many as 40% of children and is most effective in those approaching puberty. If effective, it should be used for 3-6 mo, and then an attempt should be made to taper the dosage. Some families use it intermittently (sleepovers, school trips, vacations) with success. If tapering results in recurrent enuresis, the child should return to the higher dosage. Few adverse events have been reported with the long-term use of desmopressin acetate.

For therapy-resistant enuresis or children with symptoms of an overactive bladder, anticholinergic therapy is indicated. Oxybutynin 5 mg or tolterodine 2 mg at bedtime often is prescribed. If the medication is ineffective, the dosage may be doubled. The clinician should monitor for constipation as a potential side effect.

A third-line treatment is imipramine, which is a tricyclic antidepressant. This medication has mild anticholinergic and α-adrenergic effects, reduces the urine output slightly, and also might alter the sleep pattern. The dosage of imipramine is 25 mg in children age 6-8 yr, 50 mg in children age 9-12 yr, and 75 mg in teenagers. Reported success rates are 30–60%. Side effects include anxiety, insomnia, and dry mouth, and heart rhythm may be affected. If there is any history of palpitations or syncope in the child, or sudden cardiac death or unstable arrhythmia in the family, long QT syndrome in the patient needs to be excluded. The drug is one of the most common causes of poisoning by prescription medication in younger siblings.

In unsuccessful cases, combining therapies often is effective. Alarm therapy plus desmopressin is more successful than either alone. The combination of oxybutynin chloride and desmopressin is more successful than either alone. Desmopressin and imipramine also may be combined.