Neuropathic Bladder

Jack S. Elder

Neuropathic bladder dysfunction in children usually is congenital, generally resulting from neural tube defects or other spinal abnormalities. Acquired diseases and traumatic lesions of the spinal cord are less common. Central nervous system tumors, sacrococcygeal teratoma, spinal abnormalities associated with imperforate anus (see Chapter 371 ), and spinal cord trauma also can result in abnormal innervation of the bladder and/or sphincter (Table 557.1 ).

Table 557.1

From Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Partin AW, Peters CW (eds): Campbell-Walsh urology, 11th ed, Vol 4, Philadelphia, 2016, Elsevier, Box 142-1, p. 3273.

Neural Tube Defects

Neural tube defects, resulting from failure of the neural tube to close spontaneously between the third and fourth wk in utero, result in abnormalities of the vertebral column that affect spinal cord function, including myelomeningocele and meningocele (see Chapters 609.3 and 609.4 ). Specialized medical centers in the United States have performed antenatal myelomeningocele closure. Long-term results from one large clinical trial (the “MOMS trial”), have not shown a definite improvement in lower urinary tract function, although some children have demonstrated nearly normal bladder function, and overall there has been a significant reduction in the need for ventriculoperitoneal shunting.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

The most important urologic consequences of neuropathic bladder dysfunction associated with neural tube defects are urinary incontinence (see Chapter 558 ), urinary tract infections (UTIs; see Chapter 553 ), and hydronephrosis from vesicoureteral reflux (see Chapter 554 ) or detrusor–sphincter dyssynergia (see Chapter 558 ). Pyelonephritis and renal functional deterioration (see Chapter 553 ) are common causes of premature death in affected patients.

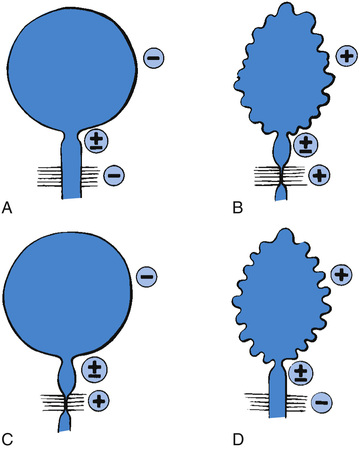

In the neonate, renal ultrasonography, assessment of postvoiding residual urine volumes, and a voiding cystourethrogram are performed after closure of the myelomeningocele. Approximately 10–15% of newborns with myelomeningocele have hydronephrosis, and renal malformations are common; 25% have vesicoureteral reflux. A urodynamic study also should be performed. In this study, the bladder is filled with saline, and the bladder volume, bladder pressure, abdominal pressure, and sphincter tone are measured until the patient voids. During bladder filling, the bladder might show (1) uninhibited (premature) contractions (termed hyperreflexia) at low volumes, (2) normal bladder volume with contraction at an appropriate volume, or (3) atonia (lack of bladder contraction). Bladder compliance or elasticity also may be abnormal (i.e., abnormally high bladder pressure during bladder filling). The sphincter can show (1) normal tonicity with relaxation during bladder contraction, (2) reduced or absent tonicity, or (3) normal or increased tonicity that increases significantly during a bladder contraction (termed detrusor–sphincter dyssynergia) (Fig. 557.1 ).

Renal Damage

Renal damage usually results from detrusor–sphincter dyssynergia. This dyssynergia causes functional obstruction of the bladder outlet, leading to bladder muscle hypertrophy and trabeculation, high intravesical pressure, and transmission of this high pressure into the upper urinary tracts, causing hydronephrosis (Fig. 557.2 ). Vesicoureteral reflux and UTI compound this problem, but severe hydronephrosis can result without reflux. Treatment includes reduction of bladder pressure with anticholinergic drugs (e.g., oxybutynin, 0.2 mg/kg/24 hr in 2 or 3 divided doses) and clean intermittent catheterization every 3-4 hr. If the child has vesicoureteral reflux or UTI, antimicrobial prophylaxis also is prescribed.

Temporary urinary diversion by cutaneous vesicostomy is an alternative in the newborn or infant with severe reflux, if intermittent catheterization is difficult, or if anticholinergic medications are not well tolerated. Another option for treating the severely trabeculated bladder is transurethral injection of botulinum toxin (Botox) into the detrusor muscle, which reduces bladder hypertonicity for approximately 6 mo and often needs to be repeated. A different approach in these children is to temporarily inactivate the tight sphincter by urethral overdilation or transurethral injection of botulinum toxin into the sphincter. In children with upper tract changes, continuous overnight bladder drainage allows significant bladder relaxation and can reduce bladder wall thickening and lessen hydronephrosis.

Clean intermittent catheterization and anticholinergic therapy cure reflux in up to 80% of children with grade I or II reflux. Children with more severe reflux often require subureteral endoscopic injection therapy (see Chapter 554 ) or open antireflux surgery followed by intermittent catheterization and anticholinergic drugs. In older children with myelomeningocele with high-grade reflux, UTI, and hydronephrosis, augmentation enterocystoplasty (enlarging the bladder with a patch of intestine) with intermittent catheterization may be necessary. This intervention allows a normal-capacity bladder with low bladder pressure and effective drainage of the bladder.

Urinary Incontinence

Incontinence in the child with neuropathic bladder can result from total or partial denervation of the sphincter, bladder hyperreflexia, poor bladder compliance, chronic urinary retention, or a combination of these factors.

Incontinence often is addressed at 4 to 5 yr and is tailored to the individual child. Nearly all children require clean intermittent catheterization to stay dry. This technique allows efficient bladder emptying with minimal risk of symptomatic UTI. The urinary tract should be reevaluated with renal ultrasonography, a voiding cystourethrogram, and a urodynamic study, including bladder capacity. If the external sphincter tone is sufficient and the bladder has adequate compliance, intermittent catheterization every 3-4 hr often is successful in keeping the child socially dry. If there are unstable bladder contractions, an anticholinergic medication such as oxybutynin chloride, hyoscyamine, or tolterodine is prescribed to increase bladder capacity. If there is sphincteric incompetence, α-adrenergic medications are prescribed to enhance outlet resistance. Bacteriuria is seen in up to 50% of children using intermittent self-catheterization, but it seldom causes symptoms. In the absence of reflux, there seems to be little cause for concern. Performing intermittent catheterization with a new catheter (hydrophilic or standard silicone) each time is also quite effective in preventing bacteriuria and avoids the need for antibiotic prophylaxis. With this treatment plan, 40–85% of patients are dry, depending on the definition of continence; some children wear a pad in their underwear or a diaper but feel that they are dry.

If there is persistent incontinence despite medical therapy, reconstructive urinary tract surgery nearly always can provide complete or satisfactory continence. If urethral resistance is low, bladder neck reconstructive procedures such as a periurethral sling often are successful. Alternatively, implantation of an artificial sphincter usually is successful. This sphincter consists of an inflatable cuff that is placed around the bladder neck, a pressure-regulating balloon implanted in the extraperitoneal space, and a pump mechanism that is implanted in the scrotum of boys and in the labia majora of girls. Squeezing the pump 3 to 4 times moves the fluid out of the inflatable urethral cuff and then the cuff slowly refills over the next 2 to 3 min.

If the bladder capacity or bladder compliance is low, or if there are persistent uninhibited contractions despite anticholinergic therapy, enlargement of the bladder with a patch of small or large intestine, termed augmentation cystoplasty or enterocystoplasty, is effective. These patients still need to perform clean intermittent catheterization. If urethral catheterization is difficult, a continent urinary stoma may be incorporated into the urinary tract reconstruction. A common method is the Mitrofanoff procedure (appendicovesicostomy), in which the appendix is isolated from the cecum on its vascular pedicle and is interposed between the bladder and abdominal wall to allow intermittent catheterization through a dry stoma. An ileal conduit with a bag on the abdominal wall is rarely used.

Complications of Augmentation Cystoplasty

Urinary Tract Infection

The urine may be colonized with Gram-negative bacteria, and attempts to sterilize the urine for prolonged periods usually fail. There is no evidence that chronic bacteriuria in patients who have had enterocystoplasty is associated with renal damage; therefore, only symptomatic UTIs should be treated.

Metabolic Acidosis

The enteric mucosal surface in contact with the urine absorbs ammonium, chloride, and hydrogen ions and loses potassium. Hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis can result, possibly requiring medical treatment (see Chapter 68 ). Chronic acidosis can compromise skeletal growth. This condition is common with colocystoplasty but is uncommon with ileocystoplasty. Metabolic acidosis also is common in patients with compromised renal function. To overcome this limitation of enterocystoplasty in patients with chronic renal insufficiency, a composite augmentation using stomach and a small or large bowel gastric segment can be used. The stomach secretes chloride and hydrogen ions; thus, preexisting metabolic acidosis remains stable or improves.

Spontaneous Perforation

Perforation of the augmented bladder is a life-threatening complication that results most often from acute or chronic overdistention of the augmented bladder. Patients with this complication typically present with severe abdominal pain and signs of peritonitis. Prompt diagnosis and treatment with exploratory laparotomy and bladder closure are necessary. Meticulous adherence to the prescribed program of intermittent catheterization to avoid bladder overdistention is important.

Bladder Calculi

Bladder calculi have developed in as many as 70% of children followed for 10 yr after enterocystoplasty. The calculi develop in response to mucus that accumulates in the bladder and act as a nidus for stone formation. This complication can be prevented by daily irrigation of the bladder with sterile saline.

Malignant Neoplasm

Invasive transitional cell carcinoma has been reported in nearly 4.6% of patients undergoing enterocystoplasty (compared with a 2.6% risk in spina bifida patients without enterocystoplasty). The pathogenesis is uncertain, but there is speculation that it is related to bacteriuria and the bowel-bladder contact. The risk is highest following gastrocystoplasty. The risk increases 10 yr following enterocystoplasty. Although these patients probably should undergo screening, there are no guidelines or recommendations regarding this practice. It seems appropriate to advise yearly endoscopic examinations or urine cytologic studies beginning in the 10th postoperative yr.

Future Management

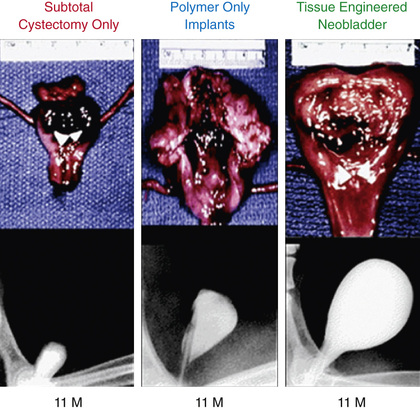

The development of a tissue-engineered bladder using a composite scaffold, which could be attached to the dome of the bladder to increase capacity and compliance, might help patients achieve continence (Fig. 557.3 ). Clinical trials are ongoing.

Associated Disorders

Constipation

Many patients with spina bifida also have bowel problems with constipation, and a vigorous bowel regimen is important. Some benefit from the Malone antegrade continence enema (MACE) procedure, in which the appendix is brought out to the skin to allow a catheter to be inserted into the cecum for antegrade enema. The stoma is continent, and an antegrade enema can be performed with tap water each day. This form of management allows the patient to be continent of stool and be more self-sufficient. An alternative to the MACE procedure is a percutaneous cecostomy, in which a button is placed into the cecum to allow an antegrade flush. The ACE and percutaneous cecostomy procedures can be performed laparoscopically.

Latex Allergy

Latex allergy is a very serious problem encountered by as many as half of patients with spina bifida and other urologic conditions who require clean intermittent catheterization and urinary tract reconstructive procedures. This immunoglobulin E–mediated allergy is acquired and is secondary to repeated exposure to the latex allergen. Latex allergy can manifest as watery eyes, sneezing, itching, hives, or anaphylaxis when blowing up a balloon or if an examiner is using latex gloves. Intraoperatively, a sensitized patient can experience anaphylactic shock. A latex-free environment should be provided for all children with spina bifida in the office, during hospitalization, and during operative procedures. Affected children also should wear a medical alert bracelet.

Occult Spinal Dysraphism

Approximately 1 in 4,000 patients have occult spinal dysraphism, a category that includes lipomeningocele, intradural lipoma, diastematomyelia, tight filum terminale, dermoid cyst-sinus, aberrant nerve roots, anterior sacral meningocele, and cauda equina tumor. More than 90% of patients have a cutaneous abnormality overlying the lower spine, including a small dimple, tuft of hair, dermal vascular malformation, or subcutaneous lipoma (Fig. 557.4 ). Often these children have high-arched feet, discrepancy in muscle size and strength between the legs, and a gait abnormality. Newborns and young infants often have a normal neurologic examination. Older children often have absent perineal sensation and back pain. Lower urinary tract function is abnormal in 40% of patients, including incontinence, recurrent UTI, and fecal soiling. The likelihood of a normal examination is inversely related to the child's age at surgical correction of the spinal lesion. In infants with abnormal urodynamics, 60% revert to normal; in older children, only 27% become normal. Management of the urinary tract in other children is similar to that described earlier for neural tube defects.

Sacral Agenesis

Sacral agenesis is defined as the absence of part or all of ≥ 2 lower vertebral bodies. This condition is more common in the offspring of women with diabetes. These children have a flattened buttock and a low, short gluteal cleft but usually have no orthopedic deformity, although some have high-arched feet. Palpation of the coccygeal area detects the absent vertebrae. Approximately 20% of cases are undetected until the age of 3-4 yr; many are diagnosed after unsuccessful toilet training. Urodynamic studies in these children show a variety of patterns, and most need clean intermittent catheterization and pharmacotherapy to stay dry.

Imperforate Anus

Approximately 30–45% of children with a high imperforate anus have a neuropathic bladder, often because of sacral agenesis. Newborns with imperforate anus should undergo a spinal ultrasound during their initial evaluation, and if these children have difficulty with toilet training, complete urologic evaluation with upper and lower urinary tract imaging and urodynamics should be performed. See Chapter 371 for further details.

Cerebral Palsy

Children with cerebral palsy (see Chapter 616.1 ) often have reasonable bladder control. However, they achieve continence at a later age than unaffected children. Overall, 25–50% are incontinent, and the risk is directly related to the severity of physical impairment. Their upper urinary tracts usually are normal. Urodynamic studies have shown that most have uninhibited bladder contractions. Timed voiding and anticholinergic therapy are usually effective. Upper urinary tract deterioration is uncommon, and clean intermittent catheterization rarely is necessary.