Stomach and duodenal origin

Bleeding ulcers account for 50% of the cases of upper GI bleeding.19 Erosion of a blood vessel by an ulcer located in the stomach or duodenum must always be considered as a possible cause of upper GI bleeding. A gastric ulcer may penetrate the left gastric artery and a duodenal ulcer may penetrate the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery. There is a decrease in bleeding ulcers related to decreased H. pylori prevalence, whereas an increasing proportion of bleeding ulcers are related to NSAID use.19

Acute gastritis produced by the ingestion of drugs or alcohol or the reflux of bile from the small intestine can result in bleeding. Drugs, either prescribed by the doctor or over-the-counter, are a major cause of upper GI bleeding. For example, the patient who regularly takes aspirin or aspirin-containing compounds may be at risk of bleeding episodes. Aspirin, NSAIDs (e.g. ibuprofen) and corticosteroids can cause irritation and disruption of the gastric mucosal barrier. Aspirin-containing products are sold without prescriptions as over-the-counter drugs. It is not unusual for a patient to deny the use of aspirin yet be self-medicating with aspirin-containing drugs, such as Alka-Seltzer and Aspalgin powders. A careful history of all commonly used drugs is therefore necessary whenever upper GI bleeding is suspected.

Physiological stress ulcers (stress-related mucosal disease), which may occur after severe burns, trauma or major surgery, erode more superficial blood vessels than does a peptic ulcer. Mucosal injury is found in approximately 70–90% of intensive care unit patients.20 The combination of hypoperfusion and gastric irritants (HCl and pepsin) possibly contributes to this mucosal damage.

Gastric cancer can also result in upper GI bleeding. Gastric cancer can be the cause of a steady blood loss as it grows and ulcerates through the mucosa and blood vessels located in its path. Gastric varices and gastric antral vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach) can also cause gastric bleeding. Arteriovenous malformations are a cause of either acute or chronic GI blood loss.

EMERGENCY ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT

Although approximately 80–85% of patients who have massive haemorrhage spontaneously stop bleeding, the cause must be identified and treatment initiated immediately. A complete history of events leading to the bleeding episode is deferred until emergency care has been initiated. The immediate physical examination must include a systemic evaluation of the patient’s condition with emphasis on blood pressure, rate and character of pulse, peripheral perfusion with capillary refill, and observation for the presence or absence of neck vein distension. Vital signs should be monitored every 15–30 minutes. Signs and symptoms of shock must be evaluated and treatment should be started as soon as possible (see Ch 66). The patient’s respiratory status should be carefully assessed, along with a thorough abdominal examination. The presence or absence of bowel sounds should be assessed and noted. A tense, rigid, board-like abdomen may indicate a perforation and peritonitis.

Once the immediate interventions have begun, the patient or family should answer the following questions. Is there a history of previous bleeding episodes? Has weight loss been a recent problem? Has the patient received blood transfusions in the past and were there any transfusion reactions? Is there a religious preference that prohibits the use of blood or blood products? Does the patient have any other illnesses that may contribute to bleeding or interfere with treatment (e.g. liver disease, cirrhosis)?

Laboratory studies should be ordered, including an FBC, serum urea, serum electrolyte and blood glucose levels, prothrombin time, liver enzyme tests and a type and cross-match for possible blood transfusions. All vomitus and stools should be tested for the presence of gross and occult blood. A urinalysis specific gravity gives an immediate indication of the patient’s hydration status.

IV lines, preferably two, with 16- or 18-gauge needles, should be established for fluid and blood replacement. The type and amount of fluids infused are dictated by physical and laboratory findings. It is generally best to begin with an isotonic crystalloid solution (e.g. Hartmann’s solution). Whole blood, packed RBCs and fresh frozen plasma may be used for replacement of lost volume in massive haemorrhage. Because of the potential for fluid overload and immunological reactions, packed RBCs are often preferred over whole blood. (The use of blood transfusions and volume expanders is discussed in Ch 30.) The haemoglobin and haematocrit values are not of immediate assistance in estimating the degree of blood loss but they provide a baseline for guiding further treatment. The initial haematocrit may be normal and may not reflect the loss until 4–6 hours after fluid replacement has taken place, since initially the loss of plasma and RBCs is equal. When upper GI bleeding is less profuse, infusion of isotonic saline solution followed by packed RBCs permits restoration of the haematocrit more quickly and does not create complications related to fluid volume overload. The use of supplemental oxygen delivered by face mask or nasal cannula may help increase blood oxygen saturation.

For most patients who are bleeding profusely, an indwelling urinary catheter is inserted so that urine volume can be accurately assessed hourly. A central venous pressure line may be inserted so that the patient’s fluid volume status can be monitored easily. If the patient has a history of valvular heart disease, coronary artery disease or congestive heart failure, or when pulmonary oedema is a factor, the use of a pulmonary artery catheter may be necessary to monitor the patient.

Most endoscopists advocate endoscopy without prior lavage to avoid mucosal injury from suction applied to the NG tube. However, others prefer an NG tube to be placed and lavage with room temperature water or saline to be initiated before endoscopy. In this case a large tube passed through the mouth may be more beneficial than a small one passed through the nose. Passage through the mouth is easier but no tube should ever be advanced against resistance because of the likelihood of damaging the gastric mucosa or causing perforation. Aspiration of stomach contents through a large-bore tube such as a Lavacuator tube facilitates the removal of clots from the stomach. Lavage allows for better endoscopic visualisation of the gastric mucosa. If used, the usual procedure is to instil approximately 50–100 mL of water or saline solution each time, leave it in place for several minutes, and then allow drainage by gravity or low suction. This procedure may be repeated every 30–45 minutes.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Endoscopic therapy

The goal of endoscopic haemostasis is to coagulate or thrombose the bleeding vessel and reduce the necessity of a surgical procedure. Endoscopic therapy has proven useful in stopping the bleeding of gastritis, Mallory-Weiss tear, oesophageal and gastric varices, bleeding peptic ulcers, arteriovenous malformations and polyps. Several techniques are used, including: (1) thermal (heat) probe; (2) multipolar and bipolar electrocoagulation probe; (3) argon plasma coagulation; (4) neodymium:yttrium-aluminium-garnet (Nd:YAG) laser; (5) the application of haemostatic clips, loops or bands; (6) injection of therapeutic agents such as adrenaline or tissue glue; and (7) balloon tamponade. Multipolar electrocoagulation, thermal probes and injection of adrenaline are the most commonly used procedures. The heat probe coagulates tissue by directly applying a heating element to the bleeding site. Argon plasma coagulation is a non-contact coagulation that delivers monopolar current to tissue. For variceal bleeding, other strategies include variceal ligation, injection sclerotherapy and balloon tamponade (see Ch 43). Overall, endoscopic therapy is more effective than medical management alone in reducing bleeding episodes.

Surgical therapy

Surgical intervention is indicated when bleeding continues regardless of the therapy provided and when the site of the bleeding has been identified. A high percentage of patients are known to have another massive haemorrhage within 5 years after the first bleeding episode. Some doctors believe surgical therapy is necessary when the patient continues to bleed after rapid transfusion of up to 2000 mL of whole blood or remains in shock after 24 hours. The site of the haemorrhage determines the choice of operation. In addition, the surgeon must consider the age of the patient because mortality rates increase considerably in those over the age of 60 years. It is essential that the operation be performed as soon as the need has been established.

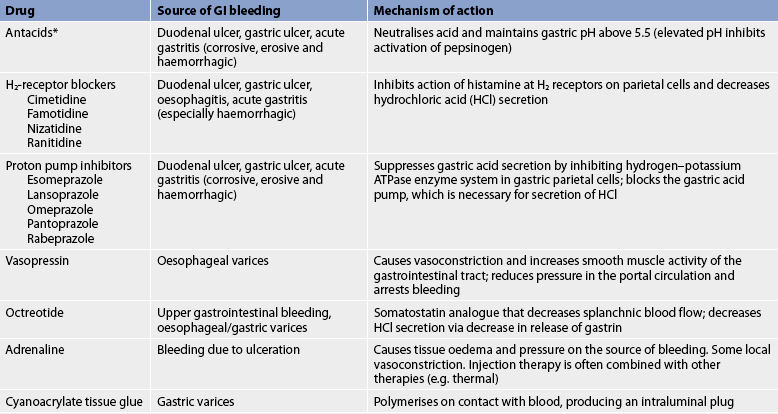

Drug therapy

During the acute phase, drugs are used to decrease bleeding, decrease HCl secretion and neutralise the HCl that is present. Drug therapy to decrease bleeding is administered during endoscopy. Injection therapy with adrenaline (1:10,000 dilution) is effective for acute haemostasis. These agents produce tissue oedema and, ultimately, pressure on the source of bleeding. To secure haemostasis and prevent rebleeding, injection therapy is often combined with other therapies (e.g. thermocoagulation or laser treatment). A sclerosant (an agent that produces inflammation and results in fibrosis of the tissues), such as sodium tetradecyl sulfate, may be used for bleeding oesophageal varices if variceal banding is not available. Tissue glue may be injected to control bleeding gastric fundal varices.

For variceal bleeding, vasopressin, which is a posterior pituitary extract, can be used to produce vasoconstriction. It is used to treat upper GI bleeding in those patients who do not respond to other therapies and who are poor surgical risks. It is administered by continuous intravenous infusion. Side effects of IV vasopressin include decreased myocardial contractility and decreased coronary blood flow. The patient undergoing vasopressin therapy must be closely monitored for its myocardial, visceral and peripheral ischaemic side effects. Vasopressin should be used with caution in patients with a known history of vascular disease.

Octreotide, a synthetic somatostatin analogue, may be beneficial in patients with upper GI bleeding, particularly variceal. The drug reduces splanchnic blood flow, as well as acid secretion. It is given as an initial IV bolus and then by continuous infusion.20 Octreotide has now largely replaced the use of vasopressin.

Efforts are made to reduce acid secretion because the acidic environment can alter platelet function, as well as interfere with clot stabilisation. A PPI (e.g. omeprazole) is administered intravenously to decrease acid secretion (see Table 41-9).

For patients who have persistent bleeding following endoscopic treatment, angiographic interventions may be used to locate the source and/or to control the bleeding. Arterial GI bleeding can be controlled by arterial infusion of vasopressin.

Sedatives to control agitation and restlessness should be administered cautiously. They make accurate assessment of the patient’s condition more difficult. Anticholinergic drugs are contraindicated in acute upper GI bleeding episodes.

Peptic ulcer disease

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is a condition characterised by erosion of the GI mucosa resulting from the digestive action of HCl and pepsin. Any portion of the GI tract that comes into contact with gastric secretions is susceptible to ulcer development, including the lower oesophagus, stomach, duodenum and margin of gastrojejunal anastomosis after surgical procedures.

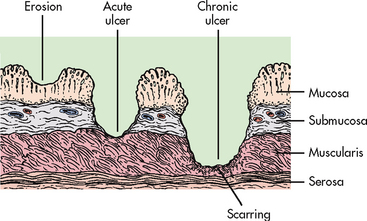

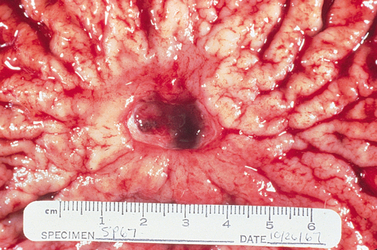

Peptic ulcers can be classified as acute or chronic, depending on the degree and duration of mucosal involvement (see Fig 41-12), and gastric or duodenal, according to the location. An acute ulcer is associated with superficial erosion and minimal inflammation. It is of short duration and resolves quickly when the cause is identified and removed. A chronic ulcer (see Fig 41-13) is one of long duration, eroding through the muscular wall with the formation of fibrous tissue. It is present continuously for many months or intermittently throughout the person’s lifetime. A chronic ulcer is at least four times as common as acute erosion.

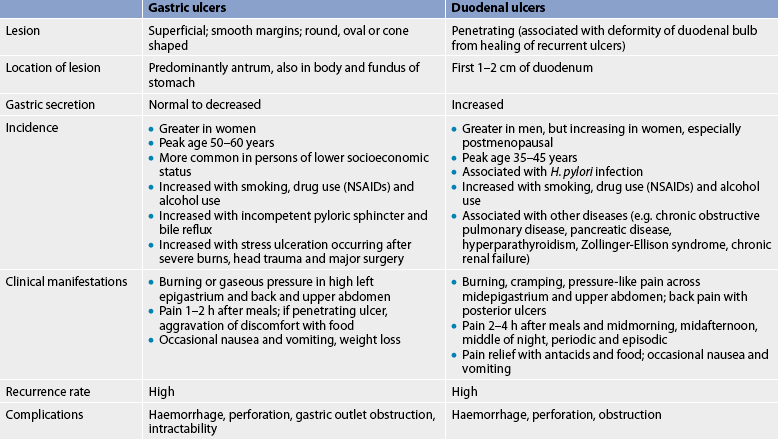

Gastric and duodenal ulcers, although defined as peptic ulcers, are different in their aetiology and incidence (see Table 41-11). Generally, however, the treatment of all types of ulcers is quite similar.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Peptic ulcers develop only in the presence of an acid environment. Patients with pernicious anaemia and achlorhydria rarely have PUD. An excess of gastric acid may not be necessary for ulcer development. The typical person with a gastric ulcer has normal to less than normal gastric acidity compared with the person with a duodenal ulcer. However, some intraluminal acid does seem to be essential for a gastric ulcer to occur.

Pepsinogen, the precursor of pepsin, is activated to pepsin in the presence of HCl and a pH of 2–3. The HCl secreted by the parietal cells has a pH of 0.8. After mixing with the stomach contents, the pH reaches 2–3, a highly favourable range of acidity for pepsin activity. When the stomach acid level is neutralised by the presence of food or antacids or when acid secretion is blocked by drugs, the pH is increased to 3.5 or more, at which level pepsin has little or no proteolytic activity.

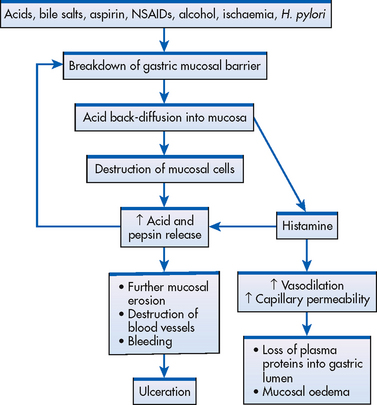

The stomach is normally protected from autodigestion by the gastric mucosal barrier. The GI tract has a high cell turnover rate and the surface mucosa of the stomach is renewed about every three days. As a result of this high turnover rate, the mucosa can continually repair itself except in extreme instances when the cell breakdown surpasses the cell renewal rate. Normally, water, electrolytes and water-soluble substances (e.g. glucose) can easily pass through the barrier, although the mucosal barrier prevents the back-diffusion of acid and pepsin from the gastric lumen through the mucosal layers to the underlying tissue. However, with certain conditions, the mucosal barrier can be impaired and back-diffusion of acid and pepsin can occur (see Fig 41-14). When the barrier is broken, HCl freely enters the mucosa and injury to the tissues occurs. This results in cellular destruction and inflammation. Histamine is released from the damaged mucosa, resulting in vasodilation and increased capillary permeability. The released histamine also stimulates further secretion of acid and pepsin.

As described in the section on gastritis, a variety of agents are known to destroy the mucosal barrier. H. pylori produces the enzyme urease, which buffers the area around it through the production of ammonia, thus protecting itself from destruction. Urease also mediates inflammation, rendering the mucosa especially vulnerable to other noxious substances. Ulcerogenic drugs, such as aspirin and NSAIDs, inhibit synthesis of prostaglandins and cause abnormal permeability. Corticosteroids have the ability to decrease the rate of mucosal cell renewal and thereby decrease the mucosal barrier’s protective effects. Lipid-soluble cytotoxic drugs can pass through the barrier and destroy it. Increased vagus nerve stimulation from a variety of causes (e.g. emotions) results in hypersecretion of HCl acid and can alter the mucosal barrier. Duodenal ulcers are associated with high acid content. It has been suggested that the continual response of the parietal cells to maximal stimulation results in hyperplasia of the cells.

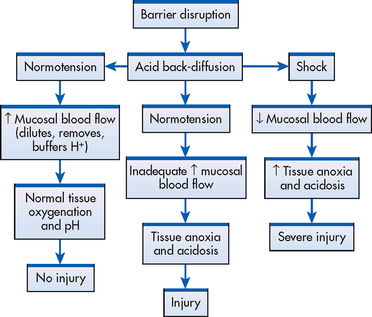

When the mucosal barrier is disrupted, there is a compensatory increase in blood flow (see Fig 41-15). This phenomenon can occur in several ways. Prostaglandin-like substances and histamine act as vasodilators, thus increasing capillary blood flow. As blood flow increases within the affected mucosa, hydrogen ions are rapidly removed from the area, buffers are delivered to help neutralise the hydrogen ions present, nutrients necessary for cell function arrive and the rate of mucosal cell replication increases. When the increase is sufficient to dilute, buffer and remove the excess hydrogen ions, tissue damage may be minimal or may result in no injury at all. When blood flow is not sufficient to carry out these processes, tissue injury results. Figure 41-15 shows a representation of the interrelationship between the mucosal blood flow and disruption of the gastric mucosal barrier.

There are two additional mechanisms that protect against damage. First, mucus is secreted by superficial mucous cells and forms a layer that can entrap or slow the diffusion of hydrogen ions across the mucosal barrier in the stomach. Second, bicarbonate is secreted by the gastric and duodenal mucosa, and this helps neutralise HCl in the lumen of the GI tract.

Gastric ulcers

Although gastric ulcers can occur in any portion of the stomach, they are most commonly found in the antrum. In Western countries, gastric ulcers are less common than duodenal ulcers. Gastric ulcers are more prevalent in women and in older adults. The mortality rate from gastric ulcers is greater than that from duodenal ulcers because the peak incidence of gastric ulcers occurs in persons over 50 years of age. Gastric ulcers are more likely to result in haemorrhage, perforation and obstruction compared to duodenal ulcers.

H. pylori, medications, smoking and bile reflux are risk factors for gastric ulcers. The ingestion of hot, rough or spicy foods has been suggested as a causative factor but there is no evidence to substantiate this claim.

Duodenal ulcers

Duodenal ulcers account for about 80% of all peptic ulcers. Duodenal ulcers may occur at any age but the incidence is especially high between 35 and 45 years of age. Duodenal ulcers can develop in anyone, regardless of occupation or socioeconomic group.

Although many factors are thought to contribute to the formation of duodenal ulcers, H. pylori has been identified as playing a key role. H. pylori is found in approximately 90–95% of patients with duodenal ulcers. However, not all individuals with evidence of H. pylori go on to develop ulcers, suggesting that additional factors are needed to produce these conditions. Examination of different strains of H. pylori suggests differences in virulence across subtypes of the organism. H. pylori survives in the human upper GI tract for a long time as a result of its ability to move in mucus, attach to mucosal cells and produce urease. Infection with H. pylori is highest in less developed countries and in people of low socioeconomic status. Although the routes of transmission are largely unknown, it is thought that infection occurs during childhood via transmission from family members to the child, possibly through a faecal–oral and/or oral–oral route. In Western countries, people born before 1940 have a significantly higher risk of carrying H. pylori than persons in younger age groups. This enhanced prevalence in older persons has been attributed to the presence of crowded living conditions and poor sanitation practices, which were more common in the first half of the last century. There is a high incidence in refugees and asylum seekers, especially those in Australia who are held in detention centres. H. pylori has been linked to mucosal-associated lymphoid tumours, gastric carcinoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Research into a genetic cause for ulcers has shown that there is a familial tendency. Supporting a genetic aetiology is the fact that people with blood group O have an increased incidence of duodenal ulcers. A proportion of ulcers are not due to NSAIDs or H. pylori. In these patients it is important to rule out Zollinger-Ellison syndrome and gastric cancer.

Stress ulcers

Stress ulcers, or stress-related mucosal disease, are acute ulcers that develop following a major physiological insult such as trauma or surgery. A stress ulcer is a form of erosive gastritis (see Fig 41-11). It is believed that the gastric mucosa of the body of the stomach undergoes a period of transient ischaemia in association with hypotension, severe injury, extensive burns or complicated surgery. The ischaemia is due to decreased capillary blood flow or shunting of blood away from the GI tract so that blood flow bypasses the gastric mucosa. This occurs as a compensatory mechanism in hypotension or shock. The decrease in blood flow produces an imbalance between the destructive properties of HCl and pepsin and the protective factors of the stomach’s mucosal barrier, especially in the fundic portion, resulting in ulceration. Multiple superficial erosions result and these may bleed. Risk factors for the development of stress ulcer bleeding are respiratory failure and coagulopathy. These patients should receive prophylaxis with antisecretory agents. The diagnosis of stress ulcer is made on endoscopy and treatment is with aggressive reduction of gastric pH using PPIs.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

It is common for the person with gastric or duodenal ulcers to have no pain or other symptoms. The gastric mucosa and duodenal mucosa are not rich in sensory pain fibres, which may account for this phenomenon. When pain does occur with duodenal ulcer, it is described as ‘burning’ or ‘cramp-like’, occurring 2–4 hours after meals. It is most often located in the midepigastric region beneath the xiphoid process and is usually relieved by food or antacids. The pain associated with gastric ulcers is located high in the epigastrium. It is not necessarily relieved by food and may occur immediately after eating or a short time (30 minutes to 2 hours) later. The pain is described as ‘burning’ or ‘gaseous’. The pain can occur when the stomach is empty or when food has been ingested. If the ulcer has eroded through the gastric mucosa, food tends to aggravate rather than alleviate the pain. Some people do not experience any pain until the presence of the ulcer is demonstrated through a serious complication such as haemorrhage or perforation.

Ulcers located on the posterior aspect of the duodenum can be manifested by back pain. They are relieved by antacids alone or in combination with an H2R antagonist and sometimes by foods that neutralise and dilute the HCl. A characteristic of a duodenal ulcer is its tendency to occur continuously for a few weeks or months and then disappear for a time, only to recur some months later.

COMPLICATIONS

The three major complications of chronic PUD are haemorrhage, perforation and gastric outlet obstruction. All are considered emergency situations and are initially treated conservatively. However, surgery may become necessary at any time during the course of the therapy.

Haemorrhage

Haemorrhage is the most common complication of PUD. It develops from erosion of the granulation tissue found at the base of the ulcer during healing or from erosion of the ulcer through a major blood vessel. Duodenal ulcers account for more upper GI bleeding episodes than gastric ulcers.

Perforation

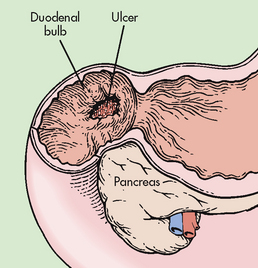

Perforation is considered the most lethal complication of a peptic ulcer. Perforation is not common and occurs more frequently with duodenal ulcers than gastric ulcers. Anterior wall duodenal ulcers are more likely to perforate and perforation tends to occur in large chronic duodenal ulcers that have not healed. Posterior duodenal ulcers that perforate will be contained by the pancreas, resulting in a penetrating, not perforated, duodenal ulcer (see Fig 41-16). Perforated gastric ulcers are most often located on the lesser curvature of the stomach. Even though duodenal ulcers are more prevalent and perforate more frequently, mortality rates associated with perforation of gastric ulcers are higher. The older age of patients with a gastric ulcer, who often have other concurrent medical problems, is thought to account for the higher mortality rates.

Perforation of a peptic ulcer occurs when the ulcer penetrates the serosal surface, with spillage of either gastric or duodenal contents into the peritoneal cavity. The size of the perforation is directly proportional to the length of time the patient has had the ulcer. The larger the perforation, the longer the history of ulcer. Small perforations seal themselves and result in a cessation of symptoms; larger perforations require immediate surgical closure. Spontaneous sealing occurs as a result of large amounts of fibrin being produced in response to the perforation. This leads to fibrinous fusion of the duodenum or gastric curvature to adjacent tissue, mainly the liver.

The clinical manifestations of perforation are characterised by their sudden and dramatic onset. The patient experiences sudden, severe upper abdominal pain that quickly spreads throughout the abdomen. The visceral and parietal layers of the peritoneum have an abundance of pain receptors and this contributes to the abrupt, intense pain experienced. There may be shoulder pain if the spillage causes irritation to the phrenic nerve. The abdominal muscles contract, appearing rigid and board-like as they attempt to protect the abdomen from further injury. The patient’s respirations become shallow and rapid. Bowel sounds are usually absent. Nausea and vomiting may occur but are generally absent. Many patients report a history of ulcer disease or recent symptoms of indigestion.

The contents entering the peritoneal cavity from the stomach or duodenum contain a variety of ingredients that include air, saliva, food particles, HCl, pepsin, bacteria, bile, and pancreatic fluid and enzymes. Bacterial peritonitis may occur within 6–12 hours. The intensity of the peritonitis is proportional to the amount and duration of the spillage through the perforation. It is difficult to determine from the sudden onset of symptoms whether a gastric or a duodenal ulcer is the cause because the clinical characteristics of intestinal perforation are the same (see Ch 42).

Gastric outlet obstruction

Ulcers located in the antrum and the prepyloric and pyloric areas of the stomach and the duodenum can predispose to gastric outlet obstruction. The obstruction is due to oedema, inflammation and pylorospasm as well as fibrous scar tissue formation, all of which contribute to the narrowing of the pylorus.

The patient with gastric outlet obstruction generally has a long history of ulcer pain. Ulcer-like pain of short duration or complete absence of pain is more indicative of a malignant obstruction. The pain progresses to a more generalised upper abdominal discomfort that becomes worse towards the end of the day as the stomach fills and dilates. Relief may be obtained by belching or by self-induced vomiting. Vomiting is common and often projectile. The vomitus contains food particles that were ingested many hours or even a day or two before the vomiting episode. There is often an offensive odour because the contents have been in the stomach for a time. The patient who vomits frequently will be anorectic, with evident weight loss, and will complain of thirst and an unpleasant taste in the mouth. Constipation is a common complaint that usually results from dehydration and decreased dietary intake secondary to anorexia.

The patient with gastric outlet obstruction may show a swelling in the upper abdomen indicating dilation of the stomach. Loud peristalsis can be heard and visible peristaltic waves are often observed passing across the abdomen from left to right. If the stomach is grossly dilated, it is possible to palpate it as well.

With the advent of improved ulcer management, gastric outlet obstruction is becoming less common.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

The diagnostic measures used to determine the presence and location of a peptic ulcer are similar to those used for acute upper GI bleeding. Endoscopy is the procedure most often used because it allows for direct viewing of the entire gastric and duodenal mucosa. This procedure can also be used to determine the degree of ulcer healing after treatment. During endoscopy, tissue specimens can be obtained for identification of H. pylori and to rule out gastric cancer.

There are currently several diagnostic tests available to confirm H. pylori infection. These are classified as non-invasive and invasive. Non-invasive tests include serum or whole blood antibody tests, in particular immunoglobulin G (IgG). This test is approximately 90–95% sensitive for H. pylori infection. However, because of the length of time that IgG levels remain elevated in the blood after the infection, the serological tests will not distinguish active from recently treated disease. The urea breath test can determine the presence of active infection. Urea is a by-product of the metabolism of H. pylori. Although not as accurate as the urea breath test, stool antigen tests can also be performed. Invasive tests involve biopsy of the stomach and include the rapid urease test, as well as other histological markers of infection. These tests have greater sensitivity and specificity but involve an endoscopic procedure.

Barium contrast studies are reserved for those patients who cannot undergo endoscopy. X-ray studies are ineffective in identifying a shallow superficial ulcer because of failure of the barium to fill the ulcer crater properly and are unable to differentiate a peptic ulcer from a malignant tumour. In addition, X-rays do not as readily demonstrate the degree of healing that can be visually determined with the endoscope. Barium studies are of benefit in the diagnosis of gastric outlet obstruction. Barium normally should pass from the stomach within 2 hours but with gastric outlet obstruction, 50% of the barium remains on follow-up films up to 6 hours later.

Gastric analysis is not used in the diagnosis of PUD but can assist in diagnosing a gastrinoma (Zollinger-Ellison syndrome). Elevated serum gastrin levels combined with elevated gastric acid secretion levels are suggestive of a gastrinoma. Gastric analysis procedure is described in Table 38-10.

Laboratory analyses, including an FBC, urinalysis, liver enzyme studies, serum amylase determination and stool examination, should be performed. An FBC may indicate the presence of anaemia secondary to bleeding from the ulcer. Liver enzyme studies help determine any liver problems, such as cirrhosis, that may complicate the treatment of the ulcer. Stools are routinely tested for the presence of blood. A serum amylase determination is frequently ordered to provide information on pancreatic function when posterior wall penetration into the pancreas is suspected.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE: CONSERVATIVE THERAPY

When the patient’s clinical manifestations and health history suggest the diagnosis of PUD and diagnostic studies confirm it, a medical regimen is instituted (see Box 41-8). The regimen consists of adequate rest, dietary modifications, drug therapy, elimination of smoking and long-term follow-up care. The aim of the treatment program is to decrease gastric acidity, enhance mucosal defence mechanisms and minimise the harmful effects on the mucosa.

BOX 41-8 Peptic ulcer disease

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Diagnostic studies

History and physical examination

Upper GI endoscopy with biopsy

H. pylori testing of breath, urine, blood, tissue

Upper GI barium contrast study

Full blood count

Urinalysis

Liver enzymes

Serum electrolytes

Collaborative therapy

Conservative therapy

Adequate rest

Bland diet (six small meals a day)

Cessation of smoking

• Drug therapy

• H2-receptor blockers (see Box 41-9)

• Proton pump inhibitors (see Box 41-9)

• Antibiotics for H. pylori (see Table 41-7)

• Antacids (see Table 41-12)

• Anticholinergics

• Cytoprotective drugs (see Box 41-9)

Stress management

Acute exacerbation without complications

NBM

NG suction

Adequate rest

Cessation of smoking

IV fluid replacement

Drug therapy

• H2-receptor blockers

• Proton pump inhibitors

• Antacids

• Anticholinergics

• Sedatives

Acute exacerbation with complications (haemorrhage, perforation, obstruction)

NBM

NG suction

Bed rest

IV fluid replacement (Hartmann’s)

Blood transfusions

Stomach lavage (possible)

Surgical therapy

Perforation—simple closure with omentum graft

Gastric outlet obstruction—pyloroplasty and vagotomy

Ulcer removal/reduction

• Billroth I and II

• Vagotomy and pyloroplasty

GI, gastrointestinal; IV, intravenous; NBM, nil by mouth; NG, nasogastric.

Patients are generally treated as outpatients. The healing of a peptic ulcer requires many weeks of therapy. Pain disappears after 3–6 days but ulcer healing is much slower. Complete healing may take 3–9 weeks, depending on the ulcer size, the treatment regimen employed and patient compliance. Endoscopic examination is the most accurate method to monitor ulcer healing. The usual follow-up endoscopic evaluation is performed 3–6 months after diagnosis and treatment.

Aspirin and non-selective NSAIDs should be discontinued or the doses reduced. There is evidence that COX-2 inhibitors are associated with a lower risk of gastric and duodenal ulcers. However, their usefulness is balanced by their association with increased risk for myocardial infarction and other cardiovascular events. When aspirin or non-selective NSAIDs must be continued, enteric-coated or highly buffered preparations or co-administration with a PPI or misoprostol should be considered. Patients with H. pylori infection and a history of ulcer complications who require NSAIDs should also receive an antisecretory agent or misoprostol in addition to antibiotics. Patients receiving low-dose aspirin for cardiovascular and stroke risk who have a history of ulcer disease or complications may need to receive long-term treatment with a PPI.21 Enteric-coated aspirin decreases localised irritation but has not been proven to reduce the overall risk for GI bleeding.

Smoking has an irritating effect on the mucosa, increases gastric motility and delays mucosal healing. It should be eliminated completely or severely reduced. Avoidance or restriction of alcohol intake will also enhance healing. The combination of adequate rest and abstinence from smoking accelerates ulcer healing. Adequate rest, both physical and emotional, is important for ulcer healing and may require some modifications in the patient’s daily routine.

Drug therapy

Drugs are a vital part of therapy. The patient must be well informed about each drug prescribed, why it is ordered and the expected benefits. Strict adherence to the prescribed regimen of drugs is important. Drug therapy includes the use of H2R antagonists, PPIs, antibiotics, antacids, cytoprotective therapy and anticholinergics (see Boxes 41-8 and 41-9, and Tables 41-12 and 41-13).

BOX 41-9 Peptic ulcer disease

DRUG THERAPY

Antisecretory

H2-receptor blockers

• Cimetidine

• Famotidine

• Nizatidine

• Ranitidine

Proton pump inhibitors

• Esomeprazole

• Lansoprazole

• Omeprazole

• Pantoprazole

• Rabeprazole

Anticholinergics

Antisecretory and cytoprotective

Cytoprotective

Sucralfate

Bismuth subsalicylate

Antibiotics for H. pylori

Amoxycillin

Metronidazole

Tetracycline

Clarithromycin

Others

Tricyclic antidepressants

• Imipramine

• Doxepin

TABLE 41-13

Side effects of antacid therapy

DRUG THERAPY

| Antacid |

Reactions |

| Aluminium hydroxide gels |

Constipation, phosphorus depletion with chronic use; calcium resorption and bone demineralisation |

| Calcium carbonate |

Constipation, hypercalcaemia, milk-alkali syndrome, renal calculi |

| Magnesium preparations |

Diarrhoea, hypermagnesaemia |

| Sodium preparations |

Milk-alkali syndrome if used with large amounts of calcium; used with caution in patients on sodium restrictions |

| Sodium bicarbonate |

Metabolic alkalosis |

Because recurrence of peptic ulcer is frequent, interruption or discontinuation of therapy can have detrimental results. The patient must be encouraged to comply with therapy and continue with follow-up care. H2R antagonists and PPIs may be stopped after the ulcer has healed or may be prescribed in the form of low-dose maintenance therapy. No other drugs, unless prescribed by the doctor, should be taken because they may have an ulcerogenic effect. Finally, the patient and family should be told what to do in the event that pain and discomfort recur or blood is noted in the vomitus or stools.

H2R antagonists

H2R antagonists, such as cimetidine, ranitidine, famotidine and nizatidine, are frequently used in the management of PUD. These drugs block the action of histamine on the H2 receptors and thus reduce HCl secretion. This decreases the conversion of pepsinogen to pepsin and accelerates ulcer healing.

H2R antagonists may be administered orally or intravenously. Depending on the specific drug, therapeutic effects last up to 12 hours. However, the onset of action (i.e. symptom relief) is longer than with antacids. Famotidine, ranitidine and nizatidine have longer half-lives than cimetidine, thus requiring fewer doses and providing nocturnal acid suppression. More side effects are associated with cimetidine. These include granulocytopenia, gynaecomastia, diarrhoea, fatigue, dizziness, rash and mental confusion in the older adult. However, the rate of these side effects is low. Famotidine and nizatidine are considered more potent at reduced dosage levels compared with cimetidine and the side effects are minimal. Ranitidine is available in an over-the-counter form. Such preparations are at a lower dose than drugs that are prescribed. H2R antagonists are used in combination with antibiotics to treat ulcers related to H. pylori and are used prophylactically to prevent stress ulcers.

PPIs

PPIs, such as omeprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole, pantoprazole and esomeprazole, block the ATPase enzyme that is important for the secretion of HCl. These agents are more effective than H2R antagonists in reducing gastric acid secretion and promoting ulcer healing. PPIs are also used in combination with antibiotics to treat ulcers caused by H. pylori.

Antibiotic therapy

Antibiotics are prescribed to eradicate H. pylori infection. The treatment of H. pylori is the most important element of treating ulcer disease in patients positive for H. pylori. When H. pylori is present, ulcer recurrence rates with H2R antagonists alone can be as high as 75–90%, whereas with antibiotic treatment the recurrence rate may be less than 10%. Antibiotic therapy for H. pylori is shown in Table 41-7. A growing percentage of patients will not have the H. pylori eradicated with a single round of therapy due to the development of antibiotic-resistant organisms. Thus, second-line therapies are needed for those who relapse.

Once the presence of H. pylori has been determined, antibiotic treatment is instituted. The regimen of choice is based on the antibiotic susceptibility of the H. pylori organism, patient compliance, side effects and costs. Most drug regimens involve treatment for 7–14 days. No single agent has been effective in eliminating H. pylori (see Table 41-7). Combination therapies of PPIs with clarithromycin and amoxycillin are used to eradicate H. pylori associated with PUD.

Antacids

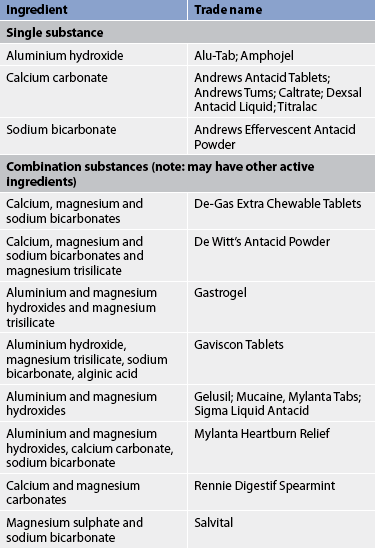

Antacids are used as adjunct therapy for PUD. They increase gastric pH by neutralising the acid. As a result, the acid content of chyme reaching the duodenum is reduced. In addition, some antacids, such as aluminium hydroxide, can bind to bile salts, thus decreasing the detrimental effects of bile on the gastric mucosa. Patients who are vulnerable for stress ulcer formation may be treated prophylactically with antacids and an antisecretory agent.

Antacids consist of systemic and non-systemic types. Systemic antacids, such as sodium bicarbonate, are extremely soluble and are absorbed into the circulation. Their long-term use can lead to systemic alkalosis; therefore, they are rarely used in ulcer treatment. The non-systemic antacids are insoluble and poorly absorbed. The common commercial non-systemic antacids consist of magnesium hydroxide or aluminium hydroxide as single preparations or in various combinations (see Table 41-12).

The antacid preparation may be in liquid or tablet form. A large number of tablets may be required to equal the same dose of a liquid preparation. Because the tablets are chewable, some of the drug is left coating the teeth and gingivae instead of the stomach.

The neutralising effects of antacids taken on an empty stomach last only 20–30 minutes because they are quickly evacuated. When antacids are taken after meals, the effects may last as long as 3–4 hours. Therapy recommending frequent dosing (e.g. hourly) often results in poor compliance.

Antacids are also used in the management of bleeding peptic ulcer. After the acute phase of bleeding has diminished, antacids are generally administered hourly, either orally or through the NG tube. If the tube is in place, the stomach contents should be aspirated and tested periodically for pH level. If pH is less than 5, intermittent suction may be used or the frequency or dosage of the antacid may be increased.

The type and dosage of antacid prescribed depends on side effects (see Table 41-13) as well as potential drug interactions. Preparations high in sodium should be used with caution in older adults and in patients with liver cirrhosis, hypertension, congestive heart failure or renal disease. Magnesium preparations should not be prescribed for patients with renal failure because of the risk of magnesium toxicity. The most frequent side effect experienced with magnesium antacids is diarrhoea. Aluminium hydroxide causes constipation. An antacid combination of aluminium and magnesium salts seems to lessen the side effects of both.

Antacids have the capacity to interact unfavourably with some drugs. They can enhance the absorption of drugs such as amphetamines. The action of digoxin can be potentiated when taken in combination with calcium or magnesium antacids. In some instances, antacids may decrease the absorption rates of prescribed drugs, such as phenytoin and tetracycline. Therefore, it is important for the nurse to inquire about any drugs that are being taken before antacid therapy is begun.

Cytoprotective drug therapy

Sucralfate is used for the short-term treatment of ulcers. It has proven to be cytoprotective of the oesophagus, stomach and duodenum. Its ability to accelerate ulcer healing is thought to be a result of the formation of an ulcer-adherent complex covering the ulcer and thereby protecting it from erosion caused by pepsin, acid and bile salts. Sucralfate does not have acid-neutralising capabilities. Its action is most effective at a low pH and it should be given at least 30 minutes before or after an antacid. Adverse side effects are minimal. However, it does bind with cimetidine, digoxin, warfarin, phenytoin and tetracycline, causing reduced bioavailability of these drugs.

Misoprostol is a synthetic prostaglandin analogue. It has protective and some antisecretory effects on gastric mucosa. Misoprostol is used for the prevention of gastric ulcers induced by NSAIDs and aspirin. A major advantage of misoprostol is that it does not interfere with the therapeutic effects of aspirin and NSAIDs. Patients who require chronic NSAID therapy, such as those with osteoarthritis, may benefit from the use of misoprostol. All NSAIDs, even COX-2 inhibitors, impair ulcer healing. Misoprostol should not be used in women of reproductive age who are pregnant or not using contraception.

Anticholinergic drugs

Anticholinergic drugs are only occasionally ordered in the treatment of PUD. These drugs decrease cholinergic (vagal) stimulation of gastric acid. Because they decrease gastric motility, they are not used where gastric outlet obstruction is a concern. Anticholinergics are associated with a number of side effects, such as dry mouth and skin, flushing, thirst, tachycardia, dilated pupils, blurred vision and urine retention. Anticholinergics must be prescribed with caution in patients with narrow-angle glaucoma and benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Nutritional therapy

There is no specific recommended dietary modification for PUD. Each patient should be instructed to eat and drink foods and fluids that do not cause any distressing symptoms. Alcohol and caffeine-containing products should be eliminated because of their irritating effects. Foods known to irritate the gastric mucosa include hot, spicy foods, fried food, chocolate, citrus fruits, tomato based products and carbonated beverages should be avoided.

Therapy related to complications of peptic ulcer disease

Acute exacerbation

An acute exacerbation is frequently accompanied by bleeding, increased pain and discomfort, and nausea and vomiting. Management is similar to that described for upper GI bleeding. Endoscopic evaluation is performed to reveal the degree of inflammation or bleeding as well as the ulcer location.

Perforation

The immediate focus of management of a patient with a perforation is to stop the spillage of gastric or duodenal contents into the peritoneal cavity and restore blood volume. An NG tube is inserted into the stomach to provide continuous aspiration and gastric decompression to halt spillage through the perforation. Although duodenal aspiration is not achieved as promptly, placement of the tube as near to the perforation site as possible facilitates decompression.

Circulating blood volume must be replaced with Hartmann’s and albumin solutions. These solutions substitute for the fluids lost from the vascular and interstitial spaces as the peritonitis develops. Blood replacement in the form of packed RBCs may be necessary. Unless contraindicated, a central venous pressure line and an indwelling urinary catheter should be inserted and monitored hourly. The patient with a history of cardiac disease requires ECG monitoring or placement of a pulmonary artery catheter for more accurate assessment of left ventricular function. Broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy should be started immediately to treat bacterial peritonitis. Administration of pain medications provides comfort.

Either open or laparoscopic procedures are used for perforation repair depending on the location of the ulcer and the surgeon’s preference. The operative procedure involving the least risk to the patient is simple oversewing of the perforation and reinforcement of the area with a graft of omentum. The excess gastric contents are suctioned from the peritoneal cavity during the surgical procedure.

Gastric outlet obstruction

The aim of therapy for obstruction is to decompress the stomach, correct any existing fluid and electrolyte imbalances and improve the patient’s general state of health. An NG tube is inserted into the stomach and attached to continuous suction to remove excess fluids and undigested food particles. With continuous decompression for several days, the stomach has the opportunity to regain its normal muscle tone, the ulcer can begin healing and the inflammation and oedema will subside.

The tube is clamped after several days of suction and gastric residue is measured periodically. The frequency and amount of time the tube remains clamped are proportional to the amount of aspirate obtained and the comfort level of the patient. A method commonly followed is to clamp the tube overnight for approximately 8–12 hours and to measure the gastric residue in the morning. When the aspirate falls below 200 mL, it is considered to be within a normal range and the patient can begin oral intake of clear liquids. Initially, oral fluids are begun at 30 mL per hour and then gradually increased in amount. The patient must be watched carefully for signs of distress or vomiting. As the amount of gastric residue decreases, solid foods are added and the tube is removed.

IV fluids and electrolytes are administered according to the degree of dehydration, vomiting and electrolyte imbalance indicated by laboratory studies. Pain relief results from the decompression measures and analgesics are usually not necessary. Antacids and antisecretory drug therapy (e.g. H2R antagonists, PPIs) are an integral part of treatment if the obstruction has been determined on endoscopic examination to be the result of an active ulcer. Pyloric obstruction may be treated non-surgically by balloon dilatations performed through the endoscope. Surgical intervention may be necessary to remove scar tissue.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE

NURSING MANAGEMENT: PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

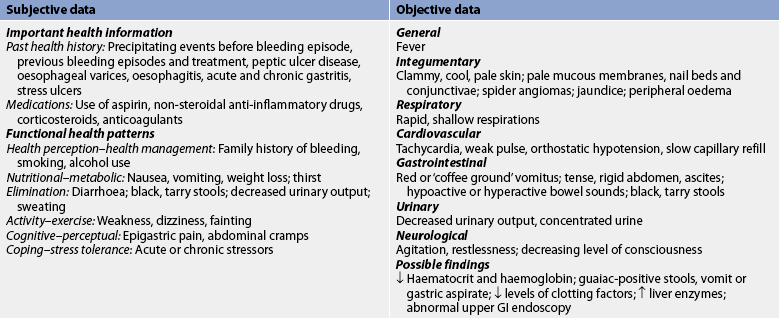

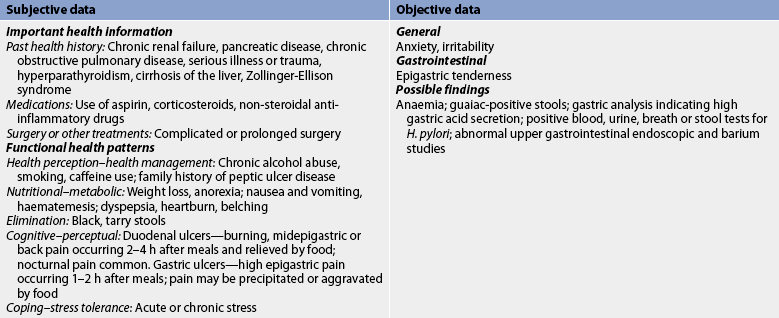

Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from a patient with PUD are presented in Table 41-14.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

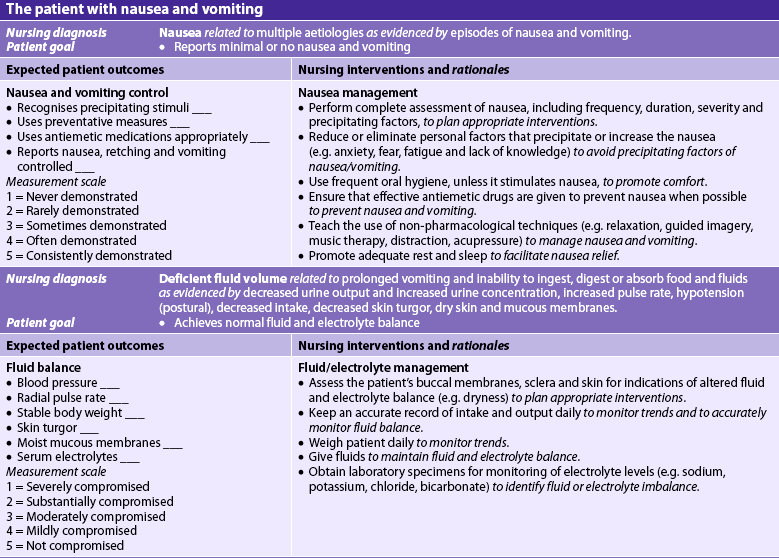

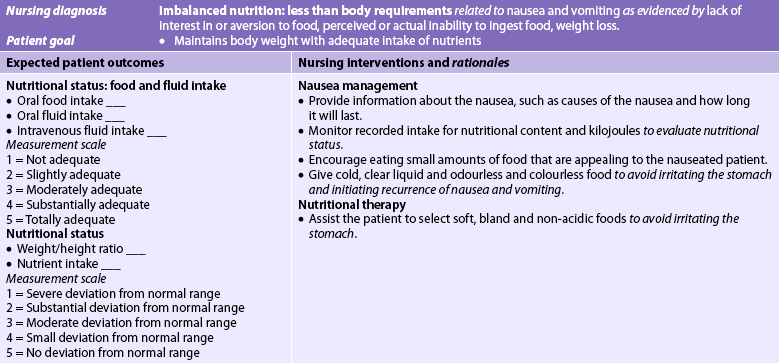

Nursing diagnoses related to PUD may include, but are not limited to, those presented in NCP 41-2.

NURSING CARE PLAN 41-2 The patient with peptic ulcer disease

Planning

Planning

Overall goals are that the patient with PUD will: (1) comply with the prescribed therapeutic regimen; (2) experience a reduction or absence of discomfort; (3) exhibit no signs of GI complications; (4) have complete healing of the peptic ulcer; and (5) make appropriate lifestyle changes to prevent recurrence.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Health promotion

Health promotion

Nurses need to be involved in identifying patients at risk of ulcer development. Early detection and treatment of ulcers are important aspects of reducing morbidity associated with ulcers. Patients who are taking ulcerogenic drugs, such as aspirin and NSAIDs, are at risk of ulcer development. Patients need to be encouraged to take these drugs with food. Patients should be taught to report symptoms related to gastric irritation, including epigastric pain, to their healthcare provider.

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

During the acute exacerbation of an ulcer, the patient generally complains of increased pain and nausea and vomiting, and some may have evidence of bleeding. Initially many patients attempt to cope with the symptoms at home before seeking medical assistance.

During this acute phase the patient may be maintained on NBM status for a few days, have an NG tube inserted and be connected to intermittent suction, and have fluids replaced intravenously. The rationale for this therapy must be conveyed to the anxious patient and family. They must understand that the advantages far outweigh any temporary discomfort imposed by the presence of the NG tube. Regular mouth care alleviates the dry mouth. Cleansing and lubrication of the nares facilitate breathing and decrease soreness. Gastric contents may be analysed for pH, blood or bile. When the stomach is kept empty of gastric secretions, the ulcer pain diminishes and ulcer healing begins. Usually this form of intervention is effective.

Because the patient is on NBM, IV fluids are ordered. The volume of fluid lost, signs and symptoms of hydration status and laboratory test results (haemoglobin, haematocrit and electrolytes) determine the type and amount of IV fluids administered. The nurse should be aware of any other current health problem that could be adversely affected by the type of fluid used or the rate of the infusion. Repeated monitoring of these parameters provides information on the hydration status and the effectiveness of treatment. Vital signs are initially taken at least hourly so that shock can be detected and treated.

Physical and emotional rest is conducive to ulcer healing. The patient’s immediate environment should be quiet and restful. The use of a mild sedative or tranquilliser has beneficial effects when the patient is anxious and apprehensive. The nurse must use good judgement before sedating a person who is becoming increasingly restless. There is a danger that the drug will mask the signs of shock secondary to upper GI bleeding.

If the patient’s condition improves without progression of symptoms (e.g. increased pain, vomiting and haemorrhage), the regimen outlined for conservative therapy is followed. However, complications such as haemorrhage, perforation and gastric outlet obstruction can occur.

Haemorrhage

Haemorrhage

Changes in the vital signs and an increase in the amount and redness of the aspirate often signal massive upper GI bleeding. When there is an increased amount of blood in the gastric contents, the patient’s pain is often decreased because the blood helps to neutralise the acidic gastric contents. It is important to maintain the patency of the NG tube so that blood clots do not obstruct the tube. If the tube becomes blocked, the patient can develop abdominal distension. Similar interventions to those described for upper GI bleeding are used. The nurse needs to monitor the results of the haemoglobin and haematocrit determinations.

Perforation

Perforation

When there is sudden, severe abdominal pain unrelated in intensity and location to the pain that brought the patient to the hospital, the nurse must recognise the possibility of ulcer perforation. Perforation is indicated by a rigid, board-like abdomen; severe generalised abdominal and shoulder pain; drawing up of the knees; and shallow, grunting respirations. The bowel sounds that may have been previously normal or hyperactive may diminish and become absent. When any person with an ulcer, particularly a chronic duodenal ulcer, demonstrates these manifestations, perforation should be suspected and the doctor notified immediately.

Vital signs should be promptly taken and recorded every 15–30 minutes. The nurse should temporarily stop all oral or NG drugs and feedings until the doctor has been notified and a definitive diagnosis made. If perforation does exist, anything taken orally can add to the spillage into the peritoneal cavity and increase discomfort. If IV fluids are being administered at the time of the perforation, the rate should be maintained or increased to replace the depleted plasma volume.

When perforation is confirmed, antibiotic therapy is usually started. When the perforation fails to seal spontaneously, surgical closure (either laparoscopically or through an open incision) is necessary and is performed as soon as possible. There is often little time to prepare the patient and family thoroughly for the surgical intervention.

Gastric outlet obstruction

Gastric outlet obstruction

Gastric outlet obstruction can occur at any time and is most likely to occur in the patient whose ulcer is located close to the pylorus. Because the onset of symptoms is usually gradual, the condition does not generally present as an emergency, as does haemorrhage or perforation. Relief of symptoms may be achieved by constant NG aspiration of stomach contents. This allows oedema and inflammation to subside and then permits normal flow of gastric contents through the pylorus.

Obstruction can also occur during the treatment of an acute episode of peptic ulcer exacerbation. If these symptoms are experienced while the patient is still on NBM, the patency of the NG tube should be suspected. Regular irrigation of the tube with a saline solution facilitates proper functioning. It may be helpful to reposition the patient from side to side so that the tube tip is not constantly lying against the mucosal surface.

When oral feedings have been resumed and symptoms of obstruction are observed, the doctor should be promptly informed. Generally, all that is necessary to treat the problem is to resume gastric aspiration so that the oedema and inflammation resulting from the acute episode have time to resolve. IV fluids with electrolyte replacement keep the patient hydrated during this period. The NG tube can be clamped and gastric fluids can be aspirated to check for retention. It is important to maintain accurate intake and output records, especially of the gastric aspirate. When conservative treatment is not successful, surgery may be performed after the acute phase has passed.

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

The patient in whom PUD has been diagnosed has specific needs that must be met to prevent and avoid recurrence or complications. General instructions should cover aspects of the disease process itself, drugs, possible changes in lifestyle (including diet) and regular follow-up care. Box 41-10 provides a patient and family teaching guide for the patient with PUD.

BOX 41-10 Peptic ulcer disease

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

The following are teaching guidelines for the patient and family:

1. Explain dietary modifications, including avoidance of foods that cause epigastric distress. This may include black pepper, spicy foods and acidic foods. Small frequent meals are better tolerated than large meals.

2. Explain the rationale for avoiding cigarettes. In addition to promoting ulcer development, smoking will delay ulcer healing.

3. Encourage the need to reduce or eliminate alcohol ingestion.

4. Explain the rationale for avoiding over-the-counter drugs unless approved by the patient’s healthcare provider. Many preparations contain ingredients, such as aspirin, that should not be taken unless approved by the healthcare provider. Check with the healthcare provider regarding the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

5. Explain the rationale for not interchanging brands of antacids and H2-receptor antagonists that can be purchased over-the-counter without checking with the healthcare provider. This interchange can lead to harmful side effects.

6. Teach the need to take all medications as prescribed. This includes both antisecretory and antibiotic drugs. Failure to take medications as prescribed can result in relapse.

7. Explain the importance of reporting any of the following:

•

increased nausea and/or vomiting

•

increase in epigastric pain

•

bloody emesis or tarry stools.

8. Explain the relationship between symptoms and stress. Stress-reducing activities or relaxation strategies are encouraged.

9. Encourage the patient and family to share their concerns about lifestyle changes and living with a chronic illness.

Knowing the cause of the ulcer and understanding the disease process may motivate the patient to become more involved in care and increase compliance with therapy. The patient must understand the dietary modifications and why they are important for recovery and health maintenance. The nurse and the dietician should elicit a dietary history from the patient and plan for ways that dietary modifications can be incorporated easily into the patient’s home and work settings. The patient who is following a diet prescribed for another illness needs to know how to balance the two so that neither condition is harmed by dietary interventions.

Patients do not always give the healthcare provider accurate information about their habitual use of alcohol or cigarettes. The nurse should provide useful information about the detrimental effects of alcohol and cigarettes on ulcer disease and ulcer healing.

The nurse should teach the patient about prescribed drugs, including their actions, side effects and inherent dangers if omitted for any reason. The patient should know why over-the-counter drugs (e.g. aspirin, NSAIDs) should not be taken unless approved by the healthcare provider. Because antacids and some H2R antagonists may be bought without a prescription, the patient must be informed that interchanging brands without checking with their doctor or nurse can lead to harmful side effects.

Efforts should be made to obtain more information about the patient’s psychosocial status. Knowledge of lifestyle, occupation and coping behaviours can be helpful in planning care. Patients may be reluctant to talk about personal subjects, the stress experienced at home or on the job, the usual methods of coping, or dependence on drugs or alcohol. Unfortunately, patients do not often see the relationship between lifestyle or occupation and ulcer disease. It is important to listen for subtle clues from the patient’s statements and to observe for behaviours that will give the nurse insight into the patient.

The need for long-term follow-up care must be stressed to the patient. Because successful treatment is frequently followed by a recurrence of the ulcer disease, the patient is instructed to seek immediate intervention if symptoms recur. The patient who has recurrence of ulcer disease following initial healing must learn to live with a disease that is chronic. They may be angry and frustrated, especially if the prescribed mode of therapy has been faithfully followed yet has failed to prevent the recurrence.

Unfortunately, many patients do not adhere to the plan of care originally designed and they experience repeated exacerbations. Patients quickly learn that they often experience no discomfort when they omit prescribed drugs or indulge in occasional dietary indiscretions. Consequently, they make no or little alteration in lifestyle. After an acute exacerbation the patient is often more amenable to following the plan of care and open to suggestions for changes in lifestyle. Changes such as smoking cessation and alcohol abstinence are difficult for many people and may be met with resistance. The patient may fare better from a reduction in use of these substances rather than total elimination. Although alcohol and smoking are known to interfere with ulcer healing, they frequently serve as coping mechanisms. From the patient’s point of view, the distress caused by their total elimination may outweigh the benefits to be gained from abstention. The goal, however, should always be total cessation. A patient with chronic ulcers must be aware of the complications that may result from the disease, the clinical manifestations indicating their presence and what to do until the healthcare provider can be seen.

Evaluation

Evaluation

Expected outcomes for the patient with a PUD are addressed in NCP 41-2.

COLLABORATIVE THERAPY: SURGICAL THERAPY FOR PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE

Due to the use of antisecretory agents, surgery for PUD is now relatively uncommon. The following criteria are used as general indications for surgical intervention:

• intractability: failure of the ulcer to heal or recurrence of the ulcer after therapy

• a history of recurrent haemorrhage or increased risk of bleeding during treatment

• a concurrent condition, such as severe burns, trauma or sepsis

• drug-induced ulcers, especially when withdrawal from the drug may put the person at risk

• possible existence of a malignant ulcer

• obstruction.

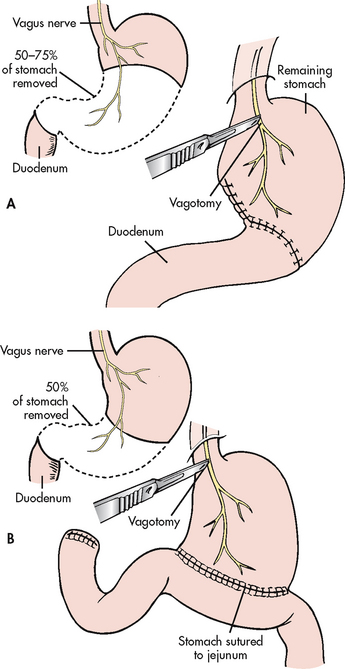

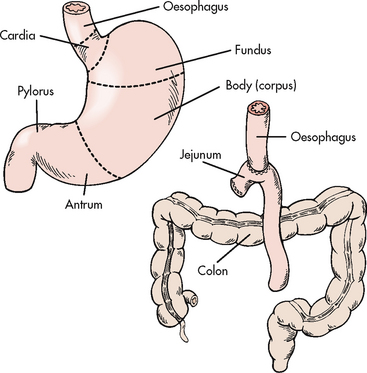

A variety of surgical procedures are used to treat PUD. They usually involve a partial gastrectomy, vagotomy or pyloroplasty. Partial gastrectomy with removal of the distal two-thirds of the stomach and anastomosis of the gastric stump to the duodenum is called a gastroduodenostomy or Billroth I operation; partial gastrectomy with removal of the distal two-thirds of the stomach and anastomosis of the gastric stump to the jejunum is called a gastrojejunostomy or Billroth II operation (see Fig 41-17). In both procedures the antrum and the pylorus are removed. Because the duodenum is bypassed, the Billroth II operation is the preferred surgical procedure to prevent recurrence of duodenal ulcers.

Vagotomy is the severing of the vagus nerve, either totally (truncal) or selectively. Selective vagotomy consists of cutting the nerve at a particular branch of the vagus nerve, resulting in denervation of only a portion of the stomach, such as the antrum or the parietal cell mass. These procedures are done to decrease gastric acid secretion.

Pyloroplasty consists of surgical enlargement of the pyloric sphincter to facilitate the easy passage of contents from the stomach. It is most commonly done after vagotomy or to enlarge an opening that has been constricted by scar tissue. A vagotomy decreases gastric motility and, subsequently, gastric emptying. A pyloroplasty accompanying vagotomy increases gastric emptying.

The combination of a Billroth I or II procedure with vagotomy has the advantage of eliminating the ulcer and the stimulus for acid secretion. Surgical removal of the antrum results in removal of the source of gastrin secretion. (Gastrin normally stimulates parietal and chief cells.) Vagotomy eliminates the stimulus of HCl and gastrin hormone secretion as a result of vagal stimulation.

Postoperative complications

Similar to all surgical procedures, acute postoperative bleeding at the surgical site can occur. Patients should be monitored as described under acute upper GI bleeding. The most common postoperative complications from peptic ulcer surgery are: (1) dumping syndrome; (2) postprandial hypoglycaemia; and (3) bile reflux gastritis.

Dumping syndrome

Dumping syndrome is the direct result of surgical removal of a large portion of the stomach and the pyloric sphincter. These changes drastically reduce the reservoir capacity of the stomach. Although dumping syndrome is more commonly experienced after a Billroth II procedure, it can occur after any gastric reconstruction and vagotomy. Approximately 20% of patients experience dumping syndrome after PUD surgery.

Dumping syndrome is associated with meals having a hyperosmolar composition. Normally, gastric chyme enters the small intestine in small amounts and thus shifts in fluid from the extracellular space are minimal. After surgery, however, the stomach no longer has control over the amount of gastric chyme entering the small intestine. Consequently, a large bolus of hypertonic fluid enters the intestine and results in fluid being drawn into the bowel lumen. This creates a decrease in plasma volume, distension of the bowel lumen and rapid intestinal transit.

The onset of symptoms occurs at the end of a meal or within 15–30 minutes after eating. The patient usually describes feelings of generalised weakness, sweating, palpitations and dizziness. These symptoms are attributed to the sudden decrease in plasma volume. The patient complains of abdominal cramps, borborygmi (audible abdominal sounds produced by hyperactive intestinal peristalsis) and the urge to defecate. These manifestations usually last for no longer than an hour after meals.

Postprandial hypoglycaemia

Postprandial hypoglycaemia is considered a variant of dumping syndrome because it is the result of uncontrolled gastric emptying of a bolus of fluid high in carbohydrate into the small intestine. The bolus of concentrated carbohydrate results in hyperglycaemia and the release of excessive amounts of insulin into the circulation. A secondary hypoglycaemia then occurs, with symptoms appearing about 2 hours after meals. The symptoms experienced are the ones observed in any hypoglycaemic reaction and include sweating, weakness, mental confusion, palpitations, tachycardia and anxiety.

Bile reflux gastritis

Gastric surgery that involves the pylorus, either reconstruction or removal, can result in reflux of bile into the stomach. Prolonged contact with bile causes damage to the gastric mucosa and chronic gastritis and the recurrence of PUD.

The symptom associated with reflux alkaline gastritis is continuous epigastric distress that increases after meals. Vomiting relieves the distress but only temporarily. The administration of cholestyramine, either before or with meals, has met with success. Cholestyramine binds with the bile salts that are the source of irritation in this condition.

Nutritional therapy

Discharge planning and instruction should be started as soon as the immediate postoperative period is successfully passed. Dietary instructions may be given by the dietician and reinforced by the nursing staff. Because the stomach’s reservoir has been greatly diminished after gastric resection, the meal size must be reduced accordingly.

Postprandial hypoglycaemic reaction can be avoided if these dietary instructions are followed. The immediate ingestion of sugared fluids or boiled lollies relieves the hypoglycaemic symptoms. The treatment of this type of hypoglycaemia is similar to that of dumping syndrome. To avoid similar occurrences the patient should be instructed to limit the amount of sugar consumed with each meal. Although only a small percentage of patients experience bile reflux gastritis, the patient must be cautioned to notify the healthcare provider of any continuous epigastric distress after meals similar to that felt before surgery.

The symptoms of dumping syndrome are self-limiting and often disappear within several months to a year after surgery. Interventions prescribed for the patient are diet instruction, rest and reassurance. The diet should consist of small, dry feedings daily that are low in carbohydrate, are restricted in refined sugars and contain moderate amounts of protein and fat. Diet principles are presented in Box 41-11.

BOX 41-11 Postgastrectomy dumping syndrome

NUTRITIONAL THERAPY

Purposes

1. To slow the rapid passage of food into the intestine.

2. To control symptoms of dumping syndrome (dizziness, sense of fullness, diarrhoea, tachycardia), which sometimes occur following a partial or total gastrectomy.

Diet principles

1. Meals are divided into six small feedings to avoid overloading the intestines at mealtimes.

2. Fluids should not be taken with meals but at least 30–45 minutes before or after meals; this helps prevent distension or a feeling of fullness.

3. Concentrated sweets (e.g. honey, sugar, jelly, jam, lollies, sweet pastries, sweetened fruit) are avoided because they sometimes cause dizziness, diarrhoea and a sense of fullness.

4. Protein and fats are increased to promote rebuilding of body tissues and to meet energy needs. Meat, cheese, eggs and milk products are specific foods to increase in the diet.

5. The amount of time these restrictions should be followed varies. The healthcare provider decides the proper amount of time to remain on this prescribed diet according to the patient’s clinical condition and progress.

Fluids should be taken between meals but not with the meal, and the patient should plan rest periods of at least 30 minutes after each meal. The recumbent position is the most beneficial if the patient can arrange it. Reassuring the patient that the unpleasant symptoms are usually of short duration is helpful in gaining cooperation.

Gerontological considerations: peptic ulcer disease

The incidence of peptic ulcers and, in particular, gastric ulcers in patients over 60 years of age is increasing.22 This is related to the increased use of NSAIDs. In the elderly patient, pain may not be the first symptom associated with an ulcer. For some patients the first manifestation may be frank gastric bleeding (e.g. haematemesis, melaena) or a decrease in haematocrit. The morbidity and mortality rates associated with gastric ulcers in the elderly patient are higher than those for younger adults because of concomitant health problems (e.g. cardiovascular, pulmonary) and a decreased ability to withstand hypovolaemia.

The treatment and management of ulcers in older adults are similar to those in younger adults. An emphasis is placed on prevention of both gastritis and peptic ulcers. This includes teaching the patient to take NSAIDs and other gastric-irritating drugs with food, milk or antacids. The patient may be treated with antisecretory agents (i.e. PPIs or H2R antagonists). Patients should be instructed to avoid irritating substances, such as alcohol and cigarette smoking, and to report abdominal pain or discomfort to their healthcare provider.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: SURGICAL THERAPY FOR PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE

NURSING MANAGEMENT: SURGICAL THERAPY FOR PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE

Preoperative care

Preoperative care

Given the greater use of endoscopic procedures for the treatment of PUD, surgical procedures are used less frequently. Surgery can involve either laparoscopic or open surgery techniques. When surgery is planned, the surgeon should provide the necessary information about the procedure and the expected outcome so that the patient can make an informed decision. The nurse can help the patient and family by clarifying and interpreting their questions. A discussion of the surgical procedure accompanied by a diagram or picture showing the anatomical changes that will result should be incorporated into the preoperative teaching plan. Instructions should be clear on what to expect after surgery, including comfort measures, pain relief, coughing and breathing exercises, use of an NG tube and IV fluid administration (see Ch 17).

Postoperative care

Postoperative care

Care of the patient after major abdominal surgery is similar to the postoperative care after abdominal laparotomy (see Ch 42). An NG tube is used to decompress the remaining portion of the stomach so as to decrease pressure on the suture line and to allow resolution of oedema and inflammation resulting from surgical trauma.

The gastric aspirate is observed for colour, amount and odour during the immediate postoperative period. The colour of the aspirate is expected to be bright red at first, with a gradual darkening within the first 24 hours after surgery. Normally the colour changes to yellow–green within 36–48 hours. If the tube becomes clogged during this period, periodic gentle irrigations with normal saline solution may be ordered. It is essential that NG suction is working and that the tube remains patent so that accumulated gastric secretions do not put a strain on the anastomosis. This can lead to distension of the remaining portion of the stomach and result in: (1) rupture of the sutures; (2) leakage of gastric contents into the peritoneal cavity; (3) haemorrhage; and (4) possible abscess formation. If the tube must be replaced or repositioned, the surgeon must be called to perform this task because of the danger of perforating the gastric mucosa or disrupting the suture line.

The nurse observes the patient for signs of decreased peristalsis and lower abdominal discomfort that may indicate impending intestinal obstruction. Accurate intake and output records must be kept. Vital signs are monitored and recorded every 4 hours.

The patient is kept comfortable and free of pain by the administration of the prescribed drugs and by frequent changes in position. The incision is relatively high in the epigastrium and may interfere with deep breathing and coughing measures, both necessary to prevent pulmonary complications. Splinting the area with a pillow assists in pain control and protects the abdominal suture line from rupturing during coughing. The dressing must be observed for signs of bleeding or odour and drainage indicative of an infection. Early ambulation is encouraged and is increased daily.

While the NG tube is connected to suction, IV therapy is maintained. Potassium and vitamin supplements are added to the infusion until oral feedings are resumed. Before the NG tube is removed, the patient is started on oral feedings of clear liquids to determine the tolerance level. The stomach is aspirated within 1 or 2 hours to assess the amount remaining and its colour and consistency. When fluids are well tolerated, the tube is removed and fluids are increased in frequency with a slow progression to regular foods. The regimen of six small meals a day is begun.

Pernicious anaemia is a long-term complication of total gastrectomy and may occur after partial gastrectomy. Pernicious anaemia is caused by the loss of intrinsic factor, which is produced by the parietal cells. Depending on the amount of parietal cell mass removed in surgery, the patient may eventually require regular injections of vitamin B12. (Vitamin B12 deficiency and pernicious anaemia are discussed in Ch 30.)

PUD is a chronic problem and ulcers can recur, especially at the site of the anastomosis. Adequate rest, nutrition, adherence to prescribed drug therapy and avoidance of known irritants and stressors are keys to complete recovery. Avoiding the use of drugs not prescribed by the healthcare provider is re-emphasised, along with restrictions on smoking and alcohol use. If the patient is willing to make these kinds of adjustment in lifestyle, a successful rehabilitation is more likely.

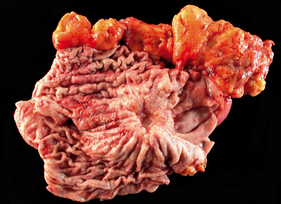

Gastric cancer

Gastric cancer commonly refers to adenocarcinoma of the stomach (see Fig 41-18), which accounts for 95% of gastric malignancies. Other histological types include lymphomas and smooth muscle sarcomas. The rate of gastric cancer has been steadily declining since the 1930s. In New Zealand the rates are 4.3 per 100,000 for women and 8.7 per 100,000 for men.1 Although mortality has declined over recent years, gastric cancer is the twelfth most common cancer in Australia and accounts for nearly 1900 new cancer cases and more than 1000 deaths annually.2 Gastric cancer shows the largest ethnic inequalities of the GI cancers, with Māoris experiencing two to three times the rates of non-Māoris. Worldwide, gastric adenocarcinoma is the second most common cancer. Gastric cancer is more prevalent in men of lower socioeconomic status, primarily those living in urban areas. The incidence of gastric cancer increases with age, with most individuals diagnosed over 65. Gastric cancer is typically at an advanced stage when diagnosed and is not usually amenable to surgical resection. At the time of diagnosis, only 10–20% of patients have disease confined to the stomach and more than 50% have advanced metastatic disease. The 5-year survival rate is 80% in patients with early stages of gastric cancer and less than 30% in those with advanced disease.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Many factors have been implicated in the development of gastric cancer. Geographic differences in incidence exist and indicate a likely role for environmental factors.