Little boxes on the hillside, little boxes made of ticky tacky,

Little boxes on the hillside, little boxes all the same.

There’s a green one and a pink one, and a blue one and a yellow one,

And they’re all made out of ticky tacky, and they all look just the same.

“Little Boxes” by Malvina Reynolds (1900–1978), American folk/blues singer-songwriter and political activist.

In this chapter we begin our detailed study of fractal dimensions of a network  . There are two approaches to calculating a fractal dimension of

. There are two approaches to calculating a fractal dimension of  . One approach, applicable if

. One approach, applicable if  is a spatially embedded network, is to treat

is a spatially embedded network, is to treat  as a geometric object and apply techniques, such as box counting or modelling

as a geometric object and apply techniques, such as box counting or modelling  by an IFS,

applicable to geometric objects. For example, in Sect. 5.3 we showed how to calculate the similarity dimension d

S of a tree

described by an IFS. Also, several studies have computed d

B for networks embedded in

by an IFS,

applicable to geometric objects. For example, in Sect. 5.3 we showed how to calculate the similarity dimension d

S of a tree

described by an IFS. Also, several studies have computed d

B for networks embedded in  by applying box counting to the geometric figure. This was the approach taken to calculate d

B in [Benguigui 92] for four railroad networks, in [Arlt 03] for the microvascular network of chicks, in [Lu 04] for road networks in cities in Texas, and in [Hou 15] for electric power networks; later in this book we will consider those studies in more detail. These approaches to computing d

B make no use of network properties. The focus of this chapter is how to compute a fractal dimension for

by applying box counting to the geometric figure. This was the approach taken to calculate d

B in [Benguigui 92] for four railroad networks, in [Arlt 03] for the microvascular network of chicks, in [Lu 04] for road networks in cities in Texas, and in [Hou 15] for electric power networks; later in this book we will consider those studies in more detail. These approaches to computing d

B make no use of network properties. The focus of this chapter is how to compute a fractal dimension for  using methods that treat

using methods that treat  as a network and not simply as a geometric object.

as a network and not simply as a geometric object.

. The network fractal dimensions we will consider include:

. The network fractal dimensions we will consider include: the box counting dimension (this chapter), based on the box-counting method for geometric fractals, describes how the number of boxes of size s needed to cover

varies with s,

the correlation dimension (Chapter 11), which describes how the number of nodes within r hops of a random node varies with r, extends to networks the correlation dimension of geometric objects (Chapter 9),

the information dimension (Chapter 15) which extends to networks the information dimension of geometric objects (Chapter 14),

the generalized dimensions (Chapter 17) which extends to networks the generalized dimensions of geometric objects (Chapter 16).

As discussed in the beginning of Chap. 3 and in Sect. 5.5, several definitions of “fractal” have been proposed for a geometric object Ω. None of them has proved entirely satisfactory. As we saw in Sect. 6.5, applications of d

B of Ω compare d

B to the dimension of similar objects (e.g., healthy versus unhealthy lungs), or examine how d

B changes over time. Although focusing on the definition of “fractality” for Ω does not concern us, in later chapters we will need to focus on the definition of “fractality” for  . The reason this is necessary for

. The reason this is necessary for  is that, while the terms “fractality” and “self-similarity” are often used interchangeably for Ω, they have been given very different meanings for

is that, while the terms “fractality” and “self-similarity” are often used interchangeably for Ω, they have been given very different meanings for  . With this caveat on terminology, in this chapter and in the next chapter we study the box counting dimension of

. With this caveat on terminology, in this chapter and in the next chapter we study the box counting dimension of  .

.

Analogous to computing d

B of a geometric fractal, computing d

B of  requires covering

requires covering  by a set of “boxes”, where a box is a subnetwork of

by a set of “boxes”, where a box is a subnetwork of  . The methods for computing a covering of

. The methods for computing a covering of  are also called box counting methods,

and several methods have been proposed. Most methods are for unweighted networks for which “distance” means chemical distance (i.e., hop count);

a few methods are applicable to unweighted networks, e.g., spatially embedded networks for which “distance” means Euclidean distance. Most of this chapter will focus on unweighted networks, and we begin there. Recall that throughout this book, except where otherwise indicated, we assume that

are also called box counting methods,

and several methods have been proposed. Most methods are for unweighted networks for which “distance” means chemical distance (i.e., hop count);

a few methods are applicable to unweighted networks, e.g., spatially embedded networks for which “distance” means Euclidean distance. Most of this chapter will focus on unweighted networks, and we begin there. Recall that throughout this book, except where otherwise indicated, we assume that  is a connected, unweighted, and undirected network.

is a connected, unweighted, and undirected network.

7.1 Node Coverings and Arc Coverings

In this section we consider what it means to cover a network  of N nodes and A arcs.

of N nodes and A arcs.

Definition 7.1 The network B is a subnetwork of  if B can be obtained from

if B can be obtained from  by deleting nodes and arcs.

A box is a subnetwork of

by deleting nodes and arcs.

A box is a subnetwork of  .

A box is disconnected if some nodes in the box

cannot be connected by arcs in the box. □

.

A box is disconnected if some nodes in the box

cannot be connected by arcs in the box. □

Let  be a collection of boxes. Two types of coverings of

be a collection of boxes. Two types of coverings of  have been proposed: node coverings and arc coverings.

Let s be a positive integer.

have been proposed: node coverings and arc coverings.

Let s be a positive integer.

Definition 7.2 (i) The set  is a node s-covering of the network

is a node s-covering of the network  if for each j we have diam(B

j) < s and if each node in

if for each j we have diam(B

j) < s and if each node in  is contained in exactly one B

j. (ii) The set

is contained in exactly one B

j. (ii) The set  is an arc s-covering of

is an arc s-covering of  if for each j we have diam(B

j) < s and if each arc in

if for each j we have diam(B

j) < s and if each arc in  is contained in exactly one B

j. □

is contained in exactly one B

j. □

If B

j is a box in a node or arc s-covering of  , then the requirement diam(B

j) < s in Definition 7.2 implies that B

j is connected. However, as discussed in Sect. 8.6, this requirement, which is a standard assumption in defining the box counting dimension of

, then the requirement diam(B

j) < s in Definition 7.2 implies that B

j is connected. However, as discussed in Sect. 8.6, this requirement, which is a standard assumption in defining the box counting dimension of  [Gallos 07b, Kim 07a, Kim 07b, Rosenberg 17b, Song 07], may for good reasons frequently be violated in some methods for determining the fractal dimensions of

[Gallos 07b, Kim 07a, Kim 07b, Rosenberg 17b, Song 07], may for good reasons frequently be violated in some methods for determining the fractal dimensions of  .

.

It is possible to define a node covering of  to allow a node to be contained in more than one box; coverings with overlapping boxes are used in [Furuya 11, Sun 14]. The great advantage of non-overlapping boxes is that they immediately yield a probability distribution, as discussed in Chap. 15. The probability distribution obtained from a non-overlapping node covering of

to allow a node to be contained in more than one box; coverings with overlapping boxes are used in [Furuya 11, Sun 14]. The great advantage of non-overlapping boxes is that they immediately yield a probability distribution, as discussed in Chap. 15. The probability distribution obtained from a non-overlapping node covering of  is the basis for computing the information dimension d

I and the generalized dimensions D

q of

is the basis for computing the information dimension d

I and the generalized dimensions D

q of  (Chap. 17). Therefore, in this book each covering of

(Chap. 17). Therefore, in this book each covering of  is assumed to use non-overlapping boxes, as specified in Definition 7.2.

is assumed to use non-overlapping boxes, as specified in Definition 7.2.

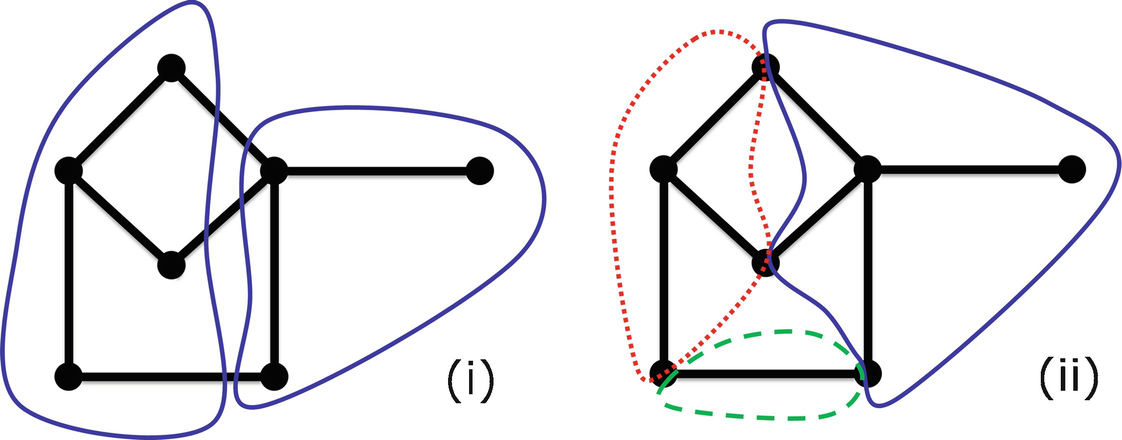

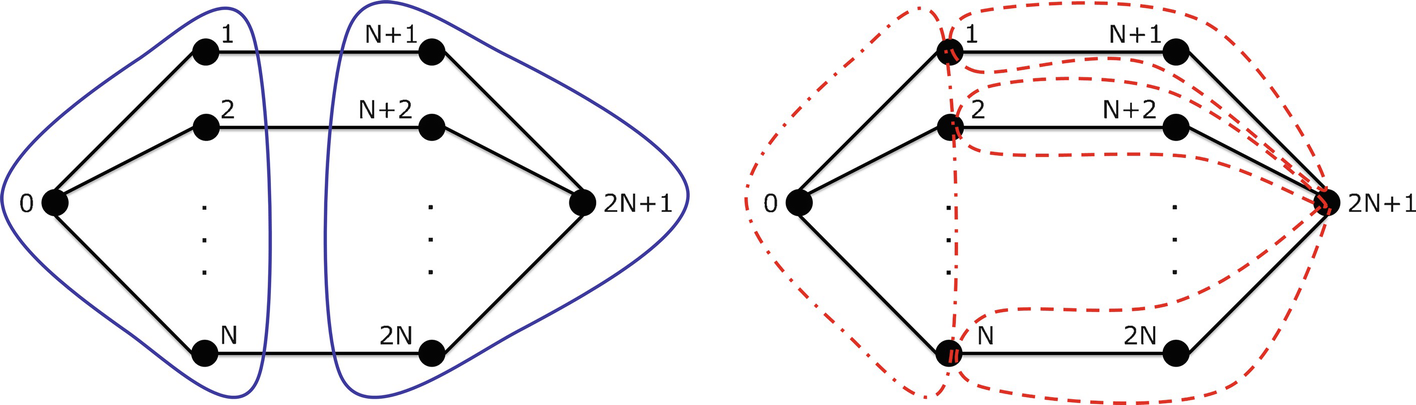

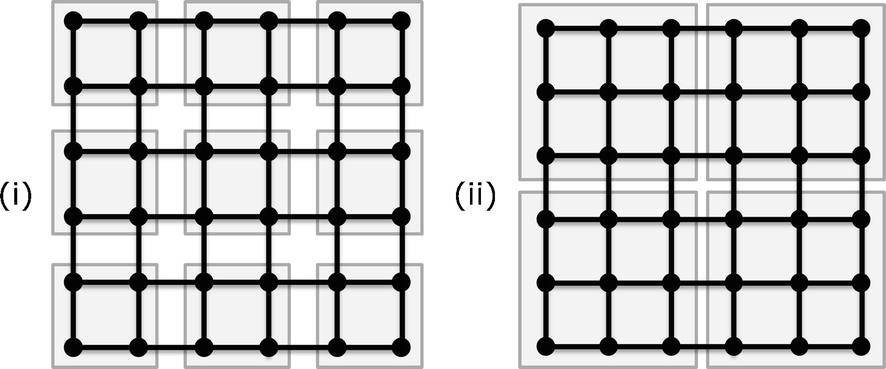

A node 3-covering (i) and an arc 3-covering (ii)

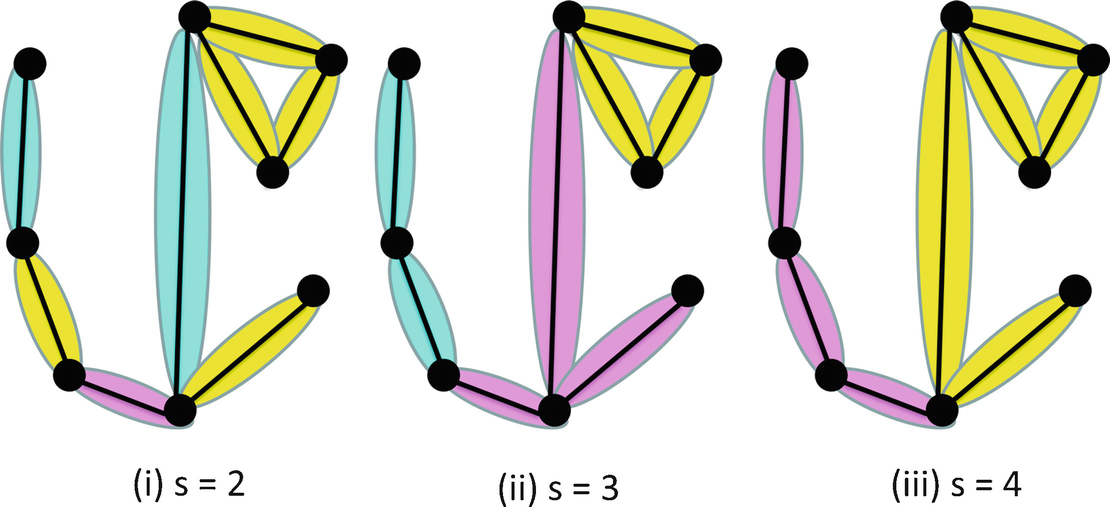

Arc s-coverings for s = 2, 3, 4

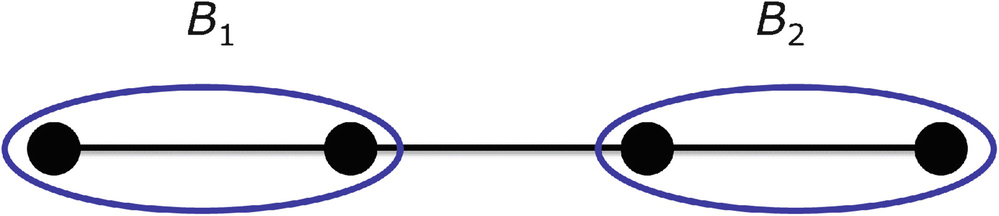

A node covering which is not an arc covering

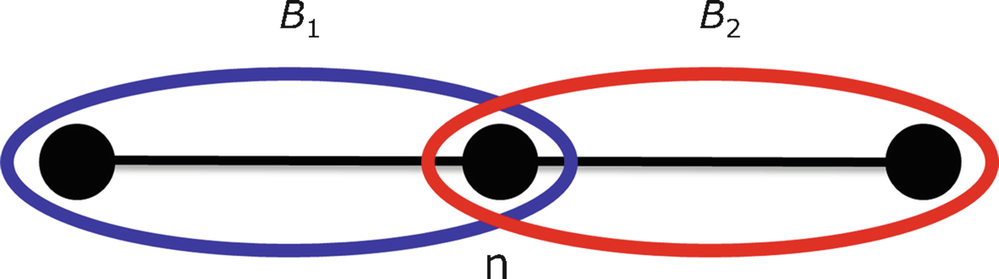

An arc covering which is not a node covering

Definition 7.3 (i) An arc s-covering  is minimal

if for any other arc s-covering

is minimal

if for any other arc s-covering  , we have J ≤ J

′. Let B

A(s) be the number of boxes in a minimal arc s-covering of

, we have J ≤ J

′. Let B

A(s) be the number of boxes in a minimal arc s-covering of  . (ii) A node s-covering

. (ii) A node s-covering  is minimal if for any other node s-covering

is minimal if for any other node s-covering  , we have J ≤ J

′. Let B

N(s) be the number of boxes in a minimal node s-covering of

, we have J ≤ J

′. Let B

N(s) be the number of boxes in a minimal node s-covering of  . □

. □

That is, a covering is minimal if it uses the fewest possible number of boxes. For s > Δ, the minimal node or arc s-covering consists of a single box, which is  itself. Thus B

A(s) = B

N(s) = 1 for s > Δ.

itself. Thus B

A(s) = B

N(s) = 1 for s > Δ.

How large can the ratio B

A(s)∕B

N(s) be? For s = 2, the ratio can be arbitrarily large. For consider  , the complete graph on N nodes, which has N(N − 1)∕2 arcs. For s = 2, we have B

N(2) = ⌈N∕2⌉, since each box in the node 2-covering contains one arc, which covers two nodes. We have B

A(2) = N(N − 1)∕2, since each box in the arc 2-covering contains one arc. Thus B

A(2)∕B

N(2) is

, the complete graph on N nodes, which has N(N − 1)∕2 arcs. For s = 2, we have B

N(2) = ⌈N∕2⌉, since each box in the node 2-covering contains one arc, which covers two nodes. We have B

A(2) = N(N − 1)∕2, since each box in the arc 2-covering contains one arc. Thus B

A(2)∕B

N(2) is  .

.

Comparing B N(2) and B A(2)

This network has 2N + 2 nodes and 3N arcs. We have B

N(3) = 2; the two boxes in the minimal node cover are shown on the left. We have B

A(3) = N + 1, as shown on the right. Thus B

A(3)∕B

N(3) is  .

.

Exercise 7.1

⋆ For each integer s ≥ 2, is there a graph with N nodes such that B

A(s)∕B

N(s) is  ? □

? □

Virtually all research on network coverings has considered node coverings; only a few studies, e.g., [Jalan 17, Zhou 07], use arc coverings. The arc covering approach of [Jalan 17] uses the N × N adjacency matrix M (Sect. 2.1). For a given integer s between 2 and N∕2, the method partitions M into non-overlapping square s × s boxes, and then counts the number m(s) of boxes containing at least one arc. The network has fractal dimension d if m(s) ∼ s −d. Since m(s) depends in general on the order in which the nodes are labelled, m(s) is averaged over many shufflings of the node order.

The reason arc coverings are rarely used is that, in practice, computing a fractal dimension of a geometric object typically starts with a given set of points in  (the points are then covered by boxes, or the distance between each pair of points is computed, as discussed in Chap. 9), and nodes in a network are analogous to points in

(the points are then covered by boxes, or the distance between each pair of points is computed, as discussed in Chap. 9), and nodes in a network are analogous to points in  . Having contrasted arc coverings and node coverings for a network, we now abandon arc coverings; henceforth, all coverings of

. Having contrasted arc coverings and node coverings for a network, we now abandon arc coverings; henceforth, all coverings of  are node coverings, and by covering

are node coverings, and by covering  we mean covering the nodes of

we mean covering the nodes of  . Also, henceforth by an s-covering we mean a node s-covering, and

by a covering of size s we mean an s-covering.

. Also, henceforth by an s-covering we mean a node s-covering, and

by a covering of size s we mean an s-covering.

7.2 Diameter-Based and Radius-Based Boxes

There are two main approaches used to define boxes for use in covering  : diameter-based boxes and radius-based boxes.

: diameter-based boxes and radius-based boxes.

Definition 7.4 (i) A radius-based box  with center node

with center node  and radius r is

the subnetwork of

and radius r is

the subnetwork of  containing all nodes whose distance to n does not exceed r. Let B

R(r) be the minimal number of radius-based boxes of radius at most r needed to cover

containing all nodes whose distance to n does not exceed r. Let B

R(r) be the minimal number of radius-based boxes of radius at most r needed to cover  . (ii) A diameter-based box

. (ii) A diameter-based box

of size s is a subnetwork of

of size s is a subnetwork of  of diameter s − 1.

Let B

D(s) denote the minimal number of diameter-based boxes of size at most s needed to cover

of diameter s − 1.

Let B

D(s) denote the minimal number of diameter-based boxes of size at most s needed to cover  . □

. □

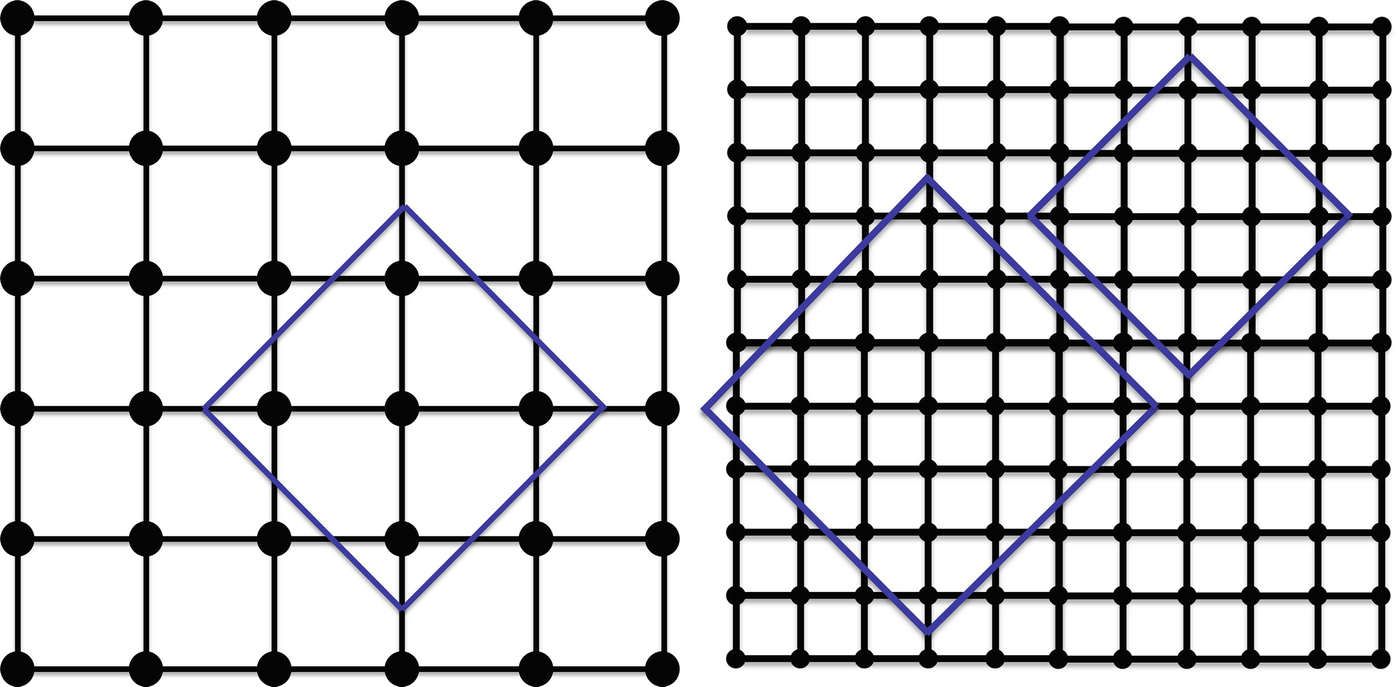

Optimal B D(3) box (left), and optimal B D(5) and B D(7) boxes (right)

The subscript “R” in B

R(n, r) denotes “radius”. Thus the node set of  is

is  . Radius-based boxes are used in the Maximum Excluded Mass Burning and Random Sequential Node Burning methods which we will study

in Chap. 8. Interestingly, the above definition of a radius-based box may frequently be violated in the Maximum Excluded Mass Burning and Random Sequential Node Burning methods. In particular, some radius-based boxes created by those methods may be disconnected, or some boxes may contain only

some of the nodes within distance r of the center node n.

. Radius-based boxes are used in the Maximum Excluded Mass Burning and Random Sequential Node Burning methods which we will study

in Chap. 8. Interestingly, the above definition of a radius-based box may frequently be violated in the Maximum Excluded Mass Burning and Random Sequential Node Burning methods. In particular, some radius-based boxes created by those methods may be disconnected, or some boxes may contain only

some of the nodes within distance r of the center node n.

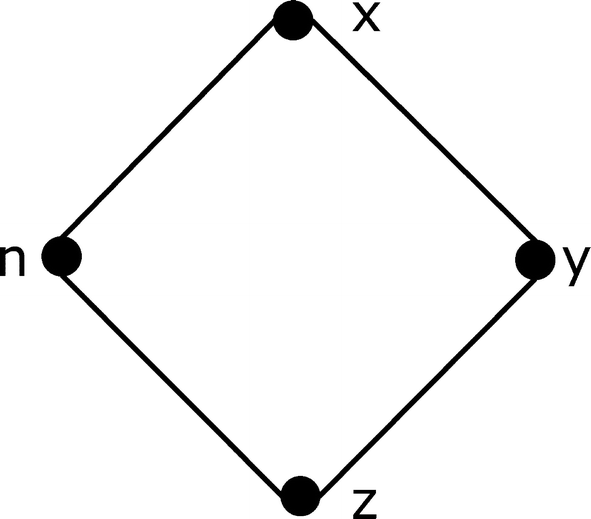

For a given s there is in general not a unique  ; e.g., for a long chain network and s small, there are many diameter-based boxes of size s. A diameter-based box

; e.g., for a long chain network and s small, there are many diameter-based boxes of size s. A diameter-based box  is not defined in terms of a center node; instead, for nodes

is not defined in terms of a center node; instead, for nodes  we require dist(x, y) < s.1 Diameter-based boxes are used in the Greedy Node Coloring, Box Burning, and Compact Box Burning heuristics described in Chap. 8. The above definition of a diameter-based box also may frequently be violated in the Box Burning and Compact Box Burning methods. Also, since each node in

we require dist(x, y) < s.1 Diameter-based boxes are used in the Greedy Node Coloring, Box Burning, and Compact Box Burning heuristics described in Chap. 8. The above definition of a diameter-based box also may frequently be violated in the Box Burning and Compact Box Burning methods. Also, since each node in  must belong to exactly one B

j in an s-covering

must belong to exactly one B

j in an s-covering  using diameter-based boxes, then in general we will not have diam(B

j) = s − 1 for all j. To see this, consider a chain of 3 nodes (call them x, y, and z), and let s = 2. The minimal 2-covering using diameter-based boxes requires two boxes, B

1 and B

2. If B

1 covers x and y, then B

2 covers only z, so the diameter of B

2 is 0.

using diameter-based boxes, then in general we will not have diam(B

j) = s − 1 for all j. To see this, consider a chain of 3 nodes (call them x, y, and z), and let s = 2. The minimal 2-covering using diameter-based boxes requires two boxes, B

1 and B

2. If B

1 covers x and y, then B

2 covers only z, so the diameter of B

2 is 0.

is, by definition, B

D(2r + 1). We have B

D(2r + 1) ≤ B

R(r) [Kim 07a]. To see this, let

is, by definition, B

D(2r + 1). We have B

D(2r + 1) ≤ B

R(r) [Kim 07a]. To see this, let  , j = 1, 2, …, B

R(r) be the boxes in a minimal covering of

, j = 1, 2, …, B

R(r) be the boxes in a minimal covering of  using radius-based boxes of radius at most r. Then r

j ≤ r for all j. Pick any j, and consider box

using radius-based boxes of radius at most r. Then r

j ≤ r for all j. Pick any j, and consider box  . For any nodes x and y in

. For any nodes x and y in  we have

we have

has diameter at most 2r.

Thus these B

R(r) boxes also serve as a covering of size 2r + 1 using diameter-based boxes. Therefore, the minimal number of diameter-based boxes of size at most 2r + 1 needed to cover

has diameter at most 2r.

Thus these B

R(r) boxes also serve as a covering of size 2r + 1 using diameter-based boxes. Therefore, the minimal number of diameter-based boxes of size at most 2r + 1 needed to cover  cannot exceed B

R(r); that is, B

D(2r + 1) ≤ B

R(r).

cannot exceed B

R(r); that is, B

D(2r + 1) ≤ B

R(r). of Fig. 7.7.

of Fig. 7.7.

Diameter-based versus radius-based boxes

The only nodes adjacent to n are x and z, so  and B

R(1) = 2. Yet the diameter of

and B

R(1) = 2. Yet the diameter of  is 2,

so it can be covered by a single diameter-based box of size 3, namely

is 2,

so it can be covered by a single diameter-based box of size 3, namely  itself, so B

D(3) = 1. Thus B

R(r) and B

D(2r + 1) are not in general equal. Nonetheless, for the C. elegans and Internet backbone networks studied in [Song 07], the calculated fractal dimension was the same whether radius-based or diameter-based boxes were used. Similarly, both radius-based and diameter-based boxes yielded a fractal dimension of approximately 4.1 for the WWW (the World Wide Web) [Kim 07a].

itself, so B

D(3) = 1. Thus B

R(r) and B

D(2r + 1) are not in general equal. Nonetheless, for the C. elegans and Internet backbone networks studied in [Song 07], the calculated fractal dimension was the same whether radius-based or diameter-based boxes were used. Similarly, both radius-based and diameter-based boxes yielded a fractal dimension of approximately 4.1 for the WWW (the World Wide Web) [Kim 07a].

As applied to a network  , the term box counting refers to computing a minimal s-covering of

, the term box counting refers to computing a minimal s-covering of  for

a range of values of s, using either radius-based boxes or diameter-based boxes. Conceivably, other types of boxes might be used to cover

for

a range of values of s, using either radius-based boxes or diameter-based boxes. Conceivably, other types of boxes might be used to cover  . Once we have computed B

D(s) for various values of s (or B

R(r) for various values of r) we can try to compute d

B.

. Once we have computed B

D(s) for various values of s (or B

R(r) for various values of r) we can try to compute d

B.

Computing any fractal dimension for a finite network is necessarily open to the same criticism that can be directed to computing a fractal dimension of a real-world geometric object, namely that a fractal dimension is defined only for a fractal (a theoretical construct with structure at infinitely many levels), and is not defined for a pre-fractal. This criticism has not impeded the usefulness of d B of real-world geometric objects. Applying the same reasoning to networks, we can try to compute d B for a finite network, and even for a small finite network.

In the literature on fractal dimensions of networks, d

B is often (e.g., [Song 07]) informally defined by the scaling  . The drawback of this definition is that the scaling relation “∼” is not well defined, e.g., often in the statistical physics literature “∼” indicates a scaling as s → 0 (Sect. 1.2), which is not meaningful for a network. In the context of network fractal dimensions, the symbol “∼”, is usually interpreted to mean “approximately behaves like”. Definition 7.5 below provides a more computationally useful definition of d

B. Recall that Δ is the diameter of

. The drawback of this definition is that the scaling relation “∼” is not well defined, e.g., often in the statistical physics literature “∼” indicates a scaling as s → 0 (Sect. 1.2), which is not meaningful for a network. In the context of network fractal dimensions, the symbol “∼”, is usually interpreted to mean “approximately behaves like”. Definition 7.5 below provides a more computationally useful definition of d

B. Recall that Δ is the diameter of  .

.

has box counting dimension d

B if over some range of s and for some constant c we have

has box counting dimension d

B if over some range of s and for some constant c we have

exists, then

exists, then  enjoys the fractal scaling property, or, more simply,

enjoys the fractal scaling property, or, more simply,  is fractal.

□

is fractal.

□Alternatively and equivalently, sometimes (7.1) is written as  . If

. If  has box counting dimension d

B, then over some range of s we have

has box counting dimension d

B, then over some range of s we have  for some constant α. Since each box in the covering need not have the same size, it could be argued that this fractal dimension of

for some constant α. Since each box in the covering need not have the same size, it could be argued that this fractal dimension of  should instead be called the Hausdorff dimension of

should instead be called the Hausdorff dimension of  ; a different definition of the Hausdorff dimension of

; a different definition of the Hausdorff dimension of  [Rosenberg 18b] is studied in Chap. 18. Calling

[Rosenberg 18b] is studied in Chap. 18. Calling  “fractal” if d

B exists is the terminology used in [Gallos 07b].

“fractal” if d

B exists is the terminology used in [Gallos 07b].

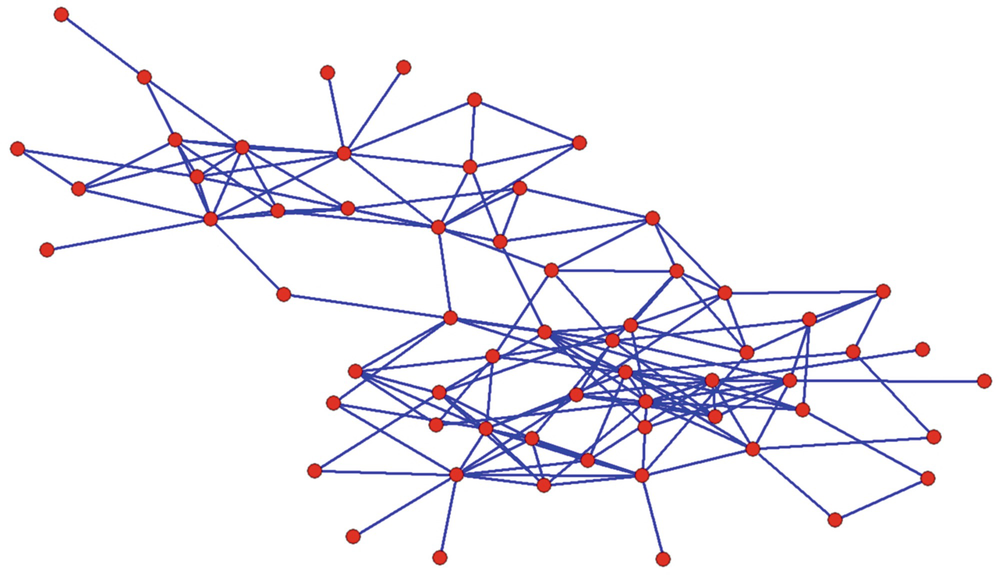

Frequent associations among 62 dolphins

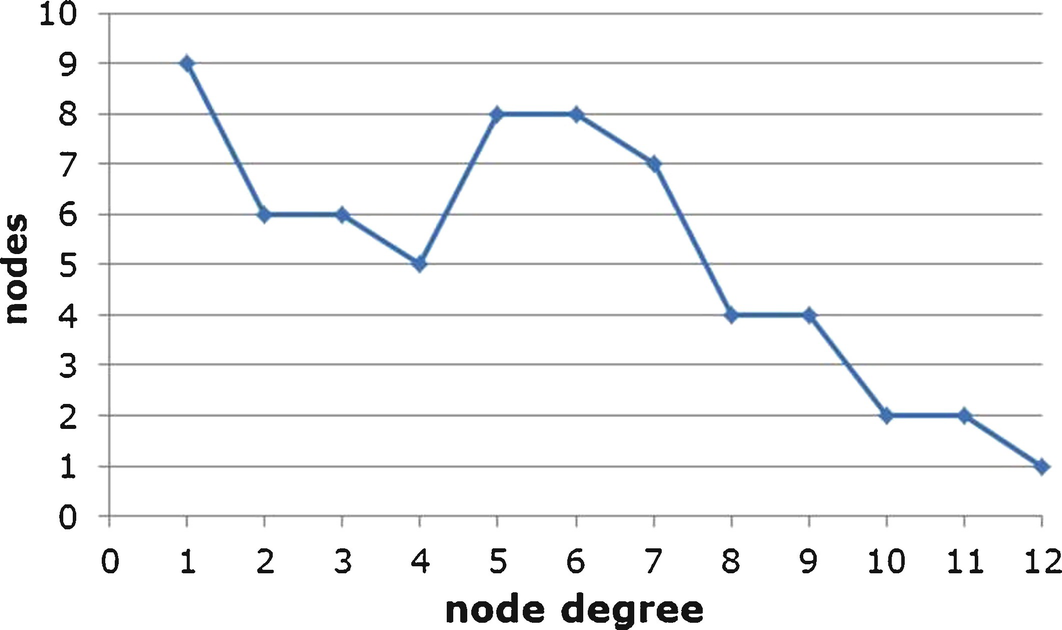

Node degrees for the dolphins network

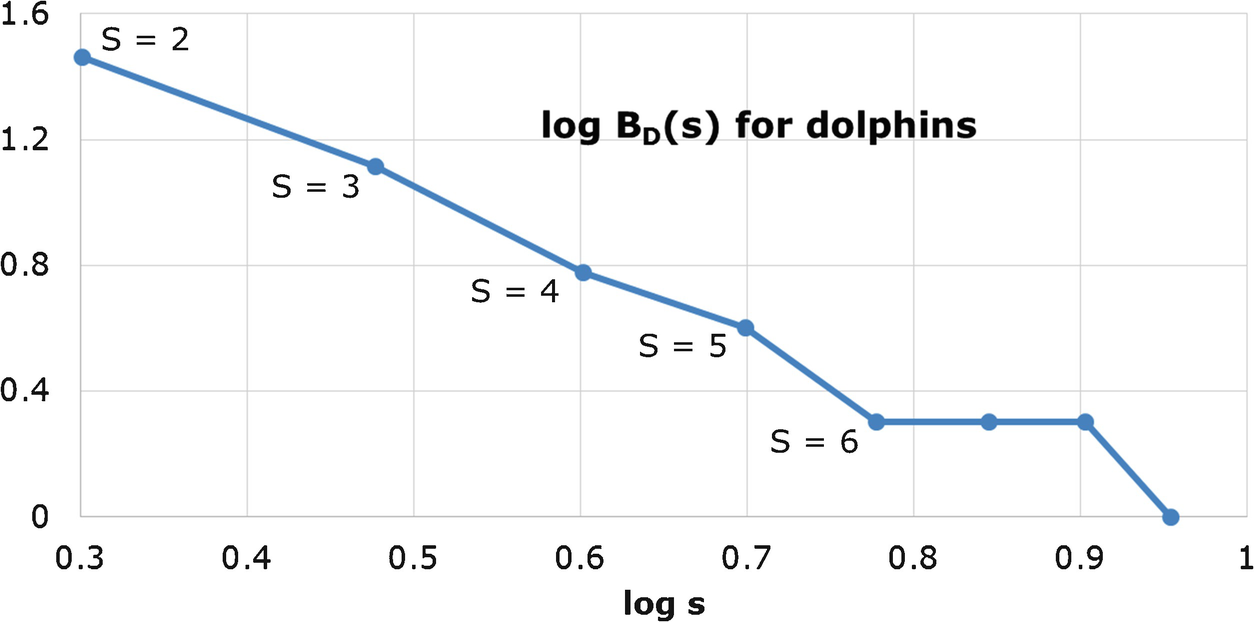

Diameter-based box counting results for the dolphins network

This figure suggests that d

B should be estimated over the range 2 ≤ s ≤ 6. Applying regression to the  values over this range of s yields the estimate d

B = 2.38. □

values over this range of s yields the estimate d

B = 2.38. □

Exercise 7.2 ⋆ In Sect. 5.4 we defined the packing dimension of a geometric object. Can we define a packing dimension of a network? □

7.3 A Closer Look at Network Coverings

In describing their box counting method (which we present in Chap. 8), [Kim 07a] wrote “The particular definition of box size has proved to be inessential for fractal scaling.” On the contrary, it can make a great deal of difference which box definition is being used when computing d

B. To see this, and recalling Definition 7.4, suppose we create two new definitions: (i) a wide box  of size s is a subnetwork of

of size s is a subnetwork of  of diameter s,

and (ii) let

of diameter s,

and (ii) let  denote the minimal number of wide boxes of size at most s needed to cover

denote the minimal number of wide boxes of size at most s needed to cover  . With these two new definitions, the difference between a wide box

. With these two new definitions, the difference between a wide box  of size s and a diameter-based box

of size s and a diameter-based box  of size s is that the diameter of

of size s is that the diameter of  is s and the diameter of

is s and the diameter of  is s − 1.

is s − 1.

Chain network

. Let N = K! for some integer K. Then for 1 ≤ s ≤ K − 1, if we cover

. Let N = K! for some integer K. Then for 1 ≤ s ≤ K − 1, if we cover  by wide boxes of size s, each box contains exactly s + 1 nodes, so there are no partially filled boxes in the covering. Figure 7.12

by wide boxes of size s, each box contains exactly s + 1 nodes, so there are no partially filled boxes in the covering. Figure 7.12

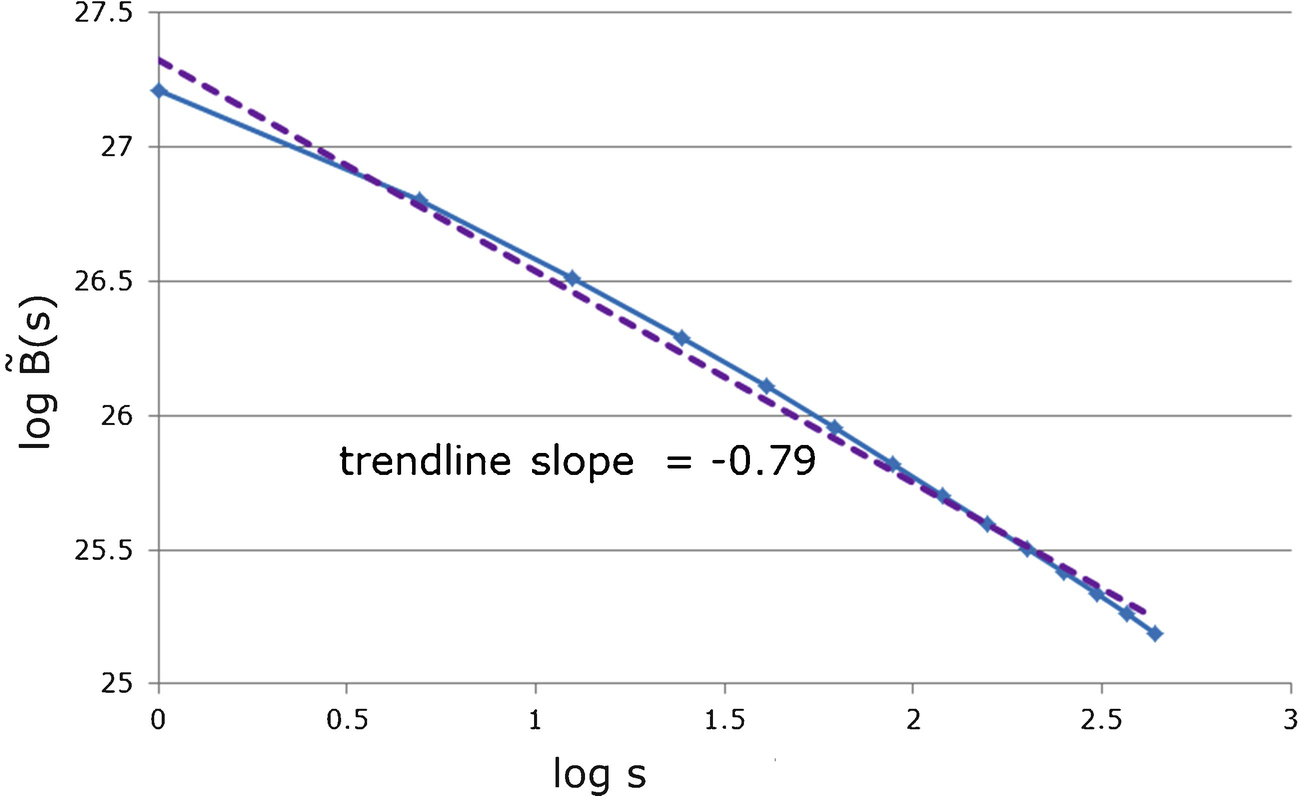

versus

versus  using wide boxes

using wide boxes

plots  versus

versus  for K = 15 and this range of s. The curve is concave, not linear, and a trend line for these points has a slope of − 0.79, rather than a straight line with a slope of − 1.

for K = 15 and this range of s. The curve is concave, not linear, and a trend line for these points has a slope of − 0.79, rather than a straight line with a slope of − 1.

cannot be satisfied, for some constant β, with d

B = 1 for some range of s. To show analytically that for this chain network

cannot be satisfied, for some constant β, with d

B = 1 for some range of s. To show analytically that for this chain network  cannot be satisfied with d

B = 1, suppose

cannot be satisfied with d

B = 1, suppose  for some range of s. For s ≤ K − 1 each wide box in the covering of the chain contains exactly s + 1 nodes, so

for some range of s. For s ≤ K − 1 each wide box in the covering of the chain contains exactly s + 1 nodes, so  and

and

with d

B = 1 cannot hold, which provides the counterexample to the claim in [Kim 07a] that the particular definition of box size is inessential. However, if we use diameter-based boxes

with d

B = 1 cannot hold, which provides the counterexample to the claim in [Kim 07a] that the particular definition of box size is inessential. However, if we use diameter-based boxes  as defined by Definition 7.4, then for a chain network of K! nodes the problem disappears, since then each box of size s contains s nodes, not s + 1. This leads to the following rule, applicable to any

as defined by Definition 7.4, then for a chain network of K! nodes the problem disappears, since then each box of size s contains s nodes, not s + 1. This leads to the following rule, applicable to any  , not just to a chain network.

, not just to a chain network.Rule 7.1 When using diameter-based boxes of size s, the box counting dimension d

B of  should be calculated using the ordered pairs

should be calculated using the ordered pairs  . □

. □

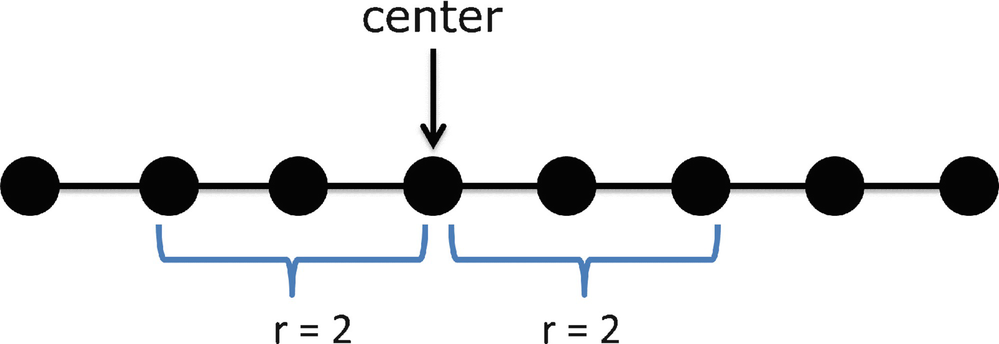

contains 2r + 1 nodes, assuming we are not close to either end of the chain. This is illustrated is Fig. 7.13, where for r = 2 the box covers 5 nodes.

contains 2r + 1 nodes, assuming we are not close to either end of the chain. This is illustrated is Fig. 7.13, where for r = 2 the box covers 5 nodes.

Radius-based box

, where β is a constant, yields B

R(r) = βr

−1, which we rewrite as rB

R(r) = β. Thus for r ≤ (K − 1)∕2,

, where β is a constant, yields B

R(r) = βr

−1, which we rewrite as rB

R(r) = β. Thus for r ≤ (K − 1)∕2,

, not just to a chain network.

, not just to a chain network.Rule 7.2 When using radius-based boxes with radius r, the box counting dimension d

B of  should be calculated using the ordered pairs

should be calculated using the ordered pairs  . □

. □

Exercise 7.3 Since B D(s) = 1 when s > Δ, does it follow that B R(r) = 1 when 2r + 1 > Δ? □

copies of G(K

2), or using

copies of G(K

2), or using  copies of G(K

1). This is illustrated in Fig. 7.14 for K = 6, K

1 = 2, and K

2 = 3.

copies of G(K

1). This is illustrated in Fig. 7.14 for K = 6, K

1 = 2, and K

2 = 3.

Covering a 6 × 6 grid

We will return to rectilinear networks in Sect. 11.4, where we study the correlation dimension of a rectilinear grid.

Exercise 7.5 Consider an infinite rectilinear grid in  . Show that, when s is odd, a box with the maximal number of nodes has a center node, and the maximal number of nodes in a box of size s is (s

2 + 1)∕2. □

. Show that, when s is odd, a box with the maximal number of nodes has a center node, and the maximal number of nodes in a box of size s is (s

2 + 1)∕2. □

Exercise 7.6 Let  be the box counting dimension of network

be the box counting dimension of network  . Suppose

. Suppose  is a subnetwork of

is a subnetwork of  . Does the strict inequality

. Does the strict inequality  hold? □

hold? □

Exercise 7.7 As discussed in Sect. 5.5, a geometric fractal is sometimes defined as an object whose dimension is not an integer. Is this a useful definition of a “fractal network”? □

Exercise 7.8 Consider an infinite rectilinear lattice in  .

What does a diameter-based box of size s look like when s is even? □

.

What does a diameter-based box of size s look like when s is even? □

Exercise 7.9 Let  be a 6 × 6 square rectilinear lattice in

be a 6 × 6 square rectilinear lattice in  . Compute B

D(s) for s = 2, 3, 4, 5. Compute B

R(r) for r = 1, 2, 3. □

. Compute B

D(s) for s = 2, 3, 4, 5. Compute B

R(r) for r = 1, 2, 3. □

7.4 The Origin of Fractal Networks

is fractal if for some d

B and some c we have

is fractal if for some d

B and some c we have  over some range of s. The main feature apparently displayed by fractal networks is a repulsion between hubs,

where a hub is a node with a significantly higher node degree

than a non-hub node. That is, the highly connected nodes tend to be not directly connected [Song 06, Zhang 16]. This tendency can be quantified using the joint node degree

distribution p(δ

1, δ

2) that a node with degree δ

1 and a node with degree δ

2 are neighbors. In contrast, for a non-fractal network

over some range of s. The main feature apparently displayed by fractal networks is a repulsion between hubs,

where a hub is a node with a significantly higher node degree

than a non-hub node. That is, the highly connected nodes tend to be not directly connected [Song 06, Zhang 16]. This tendency can be quantified using the joint node degree

distribution p(δ

1, δ

2) that a node with degree δ

1 and a node with degree δ

2 are neighbors. In contrast, for a non-fractal network  , hubs are mostly connected to other hubs, which

implies that

, hubs are mostly connected to other hubs, which

implies that  enjoys the small-world

property [Gallos 07b]. (Recall from Sect. 2.2 that

enjoys the small-world

property [Gallos 07b]. (Recall from Sect. 2.2 that  is a small-world network if

is a small-world network if  grows as

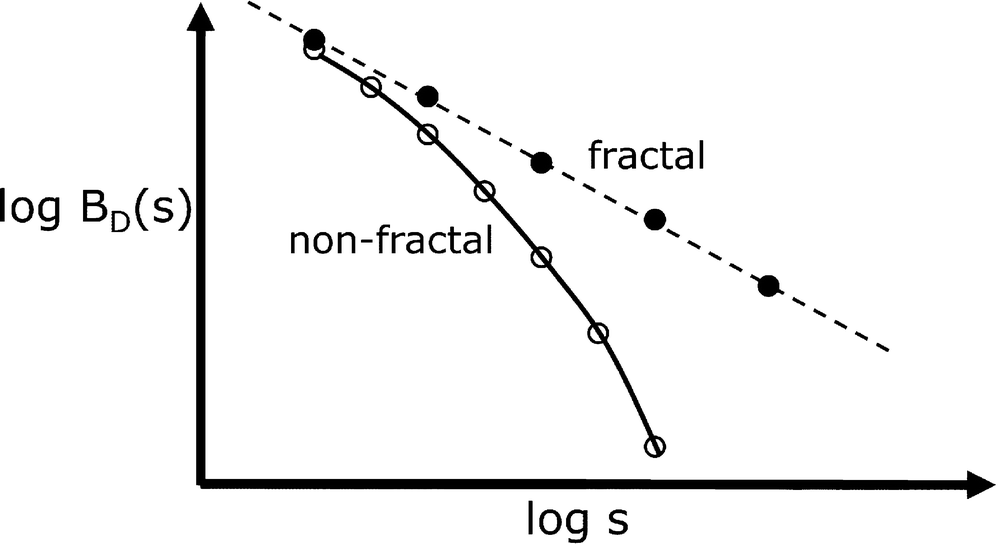

grows as  .) Also, the concepts of modularity and fractality for a network are closely related. Interconnections within a module (e.g., a biological subsystem) are more prevalent than interconnections between modules. Similarly, in a fractal network, interconnections between a hub and non-hub nodes are more prevalent than interconnections between hubs. Non-fractal networks are typically characterized by a sharp decay of B

D(s) with s, which is better described by an exponential law B

D(s) ∼ e

−β s, where β > 0, rather than by a power law B

D(s) ∼ s

−β, with a similar statement holding if radius-based boxes are used [Gallos 07b]. These two cases are illustrated in Fig. 7.15, taken from [Gallos 07b],

.) Also, the concepts of modularity and fractality for a network are closely related. Interconnections within a module (e.g., a biological subsystem) are more prevalent than interconnections between modules. Similarly, in a fractal network, interconnections between a hub and non-hub nodes are more prevalent than interconnections between hubs. Non-fractal networks are typically characterized by a sharp decay of B

D(s) with s, which is better described by an exponential law B

D(s) ∼ e

−β s, where β > 0, rather than by a power law B

D(s) ∼ s

−β, with a similar statement holding if radius-based boxes are used [Gallos 07b]. These two cases are illustrated in Fig. 7.15, taken from [Gallos 07b],

Fractal versus non-fractal scaling

where the solid circles are measurements from a fractal network, and the hollow circles are from a non-fractal network.

Various researchers have proposed models to explain why networks exhibit fractal scaling. One proposed cause [Song 06] is the disassortative correlation between the degrees of neighboring nodes. A disassortative network is a network in which nodes of low degree are more likely to connect with nodes of high degree, and so there is a strong disassortativity (i.e., repulsion) between hubs. This can be modelled by Coulomb’s Law [Zhang 16].

(Sect. 2.5). Recall that the skeleton

(Sect. 2.5). Recall that the skeleton  of

of  is often defined to be the betweenness

centrality or load-based spanning tree of

is often defined to be the betweenness

centrality or load-based spanning tree of  .

The skeleton

of a scale-free

network has been found [Kim 07b] to have the same topological properties as a random branching tree. Associated with a random branching tree

is the parameter μ(r), the average number of children of a node whose distance from the root node is r. As r →∞, we have μ(r) → μ for some μ. The critical case for this branching process corresponds to μ = 1, and for this value the random branching tree is known to be fractal. Specifically, suppose

.

The skeleton

of a scale-free

network has been found [Kim 07b] to have the same topological properties as a random branching tree. Associated with a random branching tree

is the parameter μ(r), the average number of children of a node whose distance from the root node is r. As r →∞, we have μ(r) → μ for some μ. The critical case for this branching process corresponds to μ = 1, and for this value the random branching tree is known to be fractal. Specifically, suppose  is a scale-free random branching tree for which the probability p

k that each branching event produces k offspring scales as p

k ∼ k

−γ and

is a scale-free random branching tree for which the probability p

k that each branching event produces k offspring scales as p

k ∼ k

−γ and  . Then the box counting dimension of

. Then the box counting dimension of  is given by

is given by

and

and  have been found to be nearly equal [Kim 07b], then the fractal scaling enjoyed by

have been found to be nearly equal [Kim 07b], then the fractal scaling enjoyed by  is also enjoyed by

is also enjoyed by  . For example, for the World Wide Web (WWW), the number of boxes

needed to cover the WWW and its skeleton are nearly equal, and the same fractal dimension of 4.10 is obtained [Kim 07b]. The mean branching value μ(r) hits a plateau value μ ≈ 3.5 at r ≈ 20. In contrast, for non-fractal networks, the mean branching number of the skeleton decays to zero without forming a plateau.

. For example, for the World Wide Web (WWW), the number of boxes

needed to cover the WWW and its skeleton are nearly equal, and the same fractal dimension of 4.10 is obtained [Kim 07b]. The mean branching value μ(r) hits a plateau value μ ≈ 3.5 at r ≈ 20. In contrast, for non-fractal networks, the mean branching number of the skeleton decays to zero without forming a plateau.