Chapter 6

Signal Transduction and Second Messengers

Chapter Outline

I. What is Signal Transduction?

III. General Types of Signal Transduction Cascades and their Components

IIIA. GPCRs and Classical Second Messenger Signaling

IIIB. Receptor Tyrosine Kinases and Receptor Serine/Threonine Kinases

IV. Phosphorylation by Kinases and Other Post-translational Modifications

V. Intracellular Signal Transduction Pathways

VB. Calcium Signaling Pathway: VOCs, ROCs, SMOCs, SOCs and Store Release

VC. The Ca2+-Phosphoinositide Pathway

VD. Cyclic ADP-Ribose and NAADP Pathways

VF. Nitric Oxide (NO)/Cyclic GMP Signaling Pathway

VG. Redox Signaling through NADPH Oxidase (NOX)

VH. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Signaling

VI. Nuclear Factor κB (NF-κB) Signaling Pathway

VK. Sphingomyelin/Ceramide Signaling Pathway

VL. Janus Kinase (JAK)/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STATs)

I What is Signal Transduction?

Primeval unicellular organisms undoubtedly possessed rudimentary detection systems to sense nutrient and temperature gradients, to react to variations in light and to avoid noxious stimuli in their extracellular environments. With the advent of multicellularity, eukaryotic organisms required progressively more sophisticated means to respond to an ever larger array of external cues and to coordinate activities between different cells. Increasingly complex signal transduction networks evolved in higher organisms to control intricate physiological processes such as cellular differentiation, embryonic development, memory and learning.

Classically defined, signal transduction is usually regarded as a process of information transfer mediated by soluble extracellular chemical stimuli (e.g. hormones, neurotransmitters, cytokines) that bind to transmembrane receptors at the cell surface. This initiates intracellular signaling events (e.g. phosphorylation by a kinase) that culminate in a change in a physiological process. Second messengers refer to small molecule chemical mediators, such as calcium ions, cAMP, cGMP, diacylglycerol (DAG) or inositol trisphosphate (InsP3), the concentration of which is rapidly and transiently increased inside the cell following receptor activation.

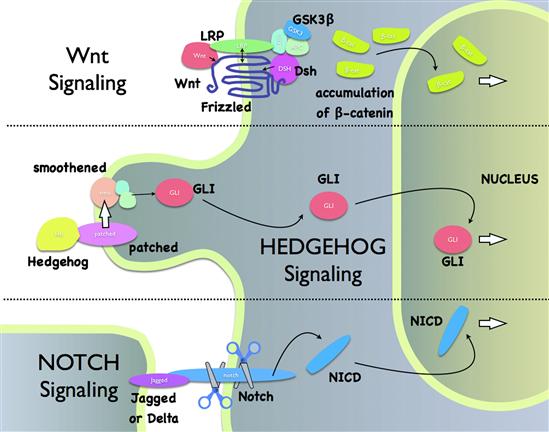

In recent years, additional modes of intracellular communication have begun to be recognized. Signal transduction has therefore become more broadly defined to encompass any type of signaling circuit used by cells to monitor external and internal states in order to effect a change in cellular activity. Most of these pathways do not require the generation of soluble second messenger molecules and they do not even necessarily involve the detection of a soluble extracellular ligand. Moreover, many seemingly specialized signaling pathways, e.g. those formerly of interest principally to developmental biologists such as Wnt, Hedgehog and Notch pathways, are now receiving attention from physiologists as well, as these highly conserved signaling mechanisms continue to exert homeostatic effects on the organism throughout its lifetime. Knowledge about the details of signaling circuits and their elaborate interrelationships is continually evolving. In this chapter, we will survey this complex topic in order to provide a general framework for understanding signaling as it relates to the study of physiology.

II General Principles

The human genome consists of about 23–25 000 protein-coding genes, but there are actually far more biological processes than unique proteins (including splice variants), indicating that many proteins are “recycled” for multiple purposes. Proteins dedicated to signal transduction are highly represented in the human genome. It has been estimated that there are 1543 genes for receptors, 518 protein kinases and 150 different protein phosphatases. Signals are used to control rapidly cellular functions such as ion channel activity, secretion or motility, but most signaling cascades ultimately converge on transcription factors (of which there are at least 1850) to execute programs of gene expression that result in long-term changes in cellular and organismal physiology (Papin et al., 2005). Differentiated cells (of which there are about 200 different types in humans) express a particular repertoire of signaling components (this has sometimes been referred to as the “signalsome”) that allow them to respond appropriately to some types of stimuli while ignoring others.

A number of factors contribute to the enormous diversification that is a hallmark of signaling circuits. First, nearly all types of signaling proteins exist as a multiplicity of distinct isoforms. For example, there are 10 isoforms of the adenylyl cyclases, the enzymes that catalyze the production of cAMP, and 12 protein kinase C (PKC) family members. While at first glance this may seem redundant, the presence of specific isoforms for receptors, effectors (the proteins mediating the signal) and final target proteins that have varying affinities for their ligands actually permits further “tuning” of responses, as it allows the pathway to discriminate between small- and large-amplitude stimulus strength. Moreover, individual isoforms of signaling proteins receive customized inputs from other signaling circuits of the signalsome to regulate differentially their activity.

Second, while there is great diversity in the individual constituents of signaling cascades, there is also some degree of redundancy coming from the fact that multiple signaling pathways frequently converge on the same target to give a similar physiological outcome. An example of this is in transcription factors, which are generally the target of multiple parallel signaling inputs.

A third factor that generates both diversity and specificity among signaling circuits is their spatial organization. Scaffolding molecules increase the efficiency of the process by helping to assemble signaling platforms. These large multiprotein complexes provide physically coupled activation–deactivation cycles of kinases, their phosphatases, upstream activators and downstream effectors. It is important to remember that the enzymatic reactions taking place in these large immobilized aggregates may not necessarily obey simple models of enzymes kinetics. Messages can also be temporally encoded, i.e. some effectors are tuned to respond to short-lived signals, while other processes require sustained signaling to exert an effect. Thus the “spatiotemporal” features of a message, even highly diffusible second messengers like Ca2+ and cAMP, can dictate the physiological response to that signal.

Subtle remodeling of signaling properties takes place throughout the lifetime of a cell due to changes in expression levels of elements within a cascade. This can give rise to a certain degree of heterogeneity even among cells of the same type. Remodeling has been considered to be a key feature in the progression of certain disease states (e.g. cancer, cardiovascular disease).

Finally, there is an incredible degree of interconnectivity among the various signaling pathways, which are also subject to complex feedback and feed-forward regulation. The signalsome of any given cell would therefore be more realistically represented as a non-linear network of interacting circuits, although generally depicted (as they are in this chapter) as simplified linear sequences of biochemical events.

III General Types of Signal Transduction Cascades and their Components

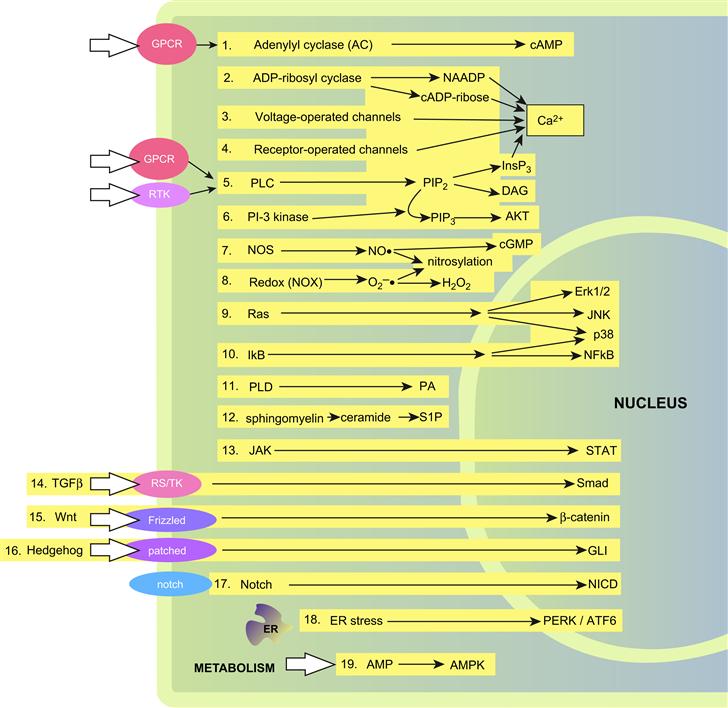

Sir Michael Berridge has categorized the major intracellular signal transduction cascades into ≈19 different groups (Berridge, 2009). Most of these pathways (Fig. 6.1) are highly conserved across animal and even plant species and many are initiated following engagement of two general types of cell surface receptors: G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) or receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). Signals are often transduced and amplified through cycles of reversible covalent modification of target proteins, catalyzed by an activator and deactivator. For example, protein kinases phosphorylate protein targets and their activity is terminated through the action of phosphatases. Another general class of transducer is the small GTP-binding proteins, whose action is accelerated by guanine-nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) and terminated by GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs). Transcription factors are frequently the ultimate target for many of these inputs (Brivanlou and Darnell, 2002). These can be resident in the nucleus, shuttle between nucleus and cytosol or require activation in the cytosol in order to gain access to the nucleus (Table 6.1). We will begin our discussion by briefly introducing some of the common players in signal transduction and then address each pathway separately.

FIGURE 6.1 Inventory of major intracellular signaling pathways. 1. Cyclic AMP signaling pathway; 2. cyclic ADP-ribose and nicotinic acid-adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP); 3. voltage-operated channels (VOCs); 4. receptor-operated channels (ROCs); 5. phospholipase C-dependent hydrolysis of PtdIns4,5P2 (PIP2); 6. PtdIns 3-kinase signaling (phosphorylation of PIP2 to form PIP3); 7. nitric oxide (NO)/cyclic GMP signaling pathway; 8. redox signaling: NADPH oxidase (NOX)→ reactive oxygen species (ROS); 9. mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling; 10. nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway; 11. phospholipase D pathway: phosphatidylcholine→phosphatidic acid (PA); 12. sphingomyelin signaling pathway: formation of ceramide and sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P); 13. Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STATs); 14. Smad signaling pathway: TGFβ→ Smad transcription factors; 15. Wnt signaling pathway; 16. hedgehog signaling: generation of the transcription factor GLI; 17. Notch signaling: generation of the transcription factor NICD (Notch intracellular domain); 18. endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling: information transfer from the ER to the nucleus; 19. AMP signaling: metabolic sensor. (Adapted from Berridge (2009). See http://www.cellsignallingbiology.org for further details.)

TABLE 6.1. Examples of Signal-Dependent Transcription Factors

| Most transcription factors are regulated by multiple signaling inputs; a classic example is CREB (cAMP response element binding), which is phosphorylated by both PKA and Ca2+/ calmodulin-dependent kinase IV (CaMKIV). |

| Nuclear receptors (e.g. steroid hormone receptors) GR, ER, PR, TR, RARs, RXRs, PPARs |

| Regulated by internal states (e.g. ER stress, DNA damage, hypoxia) SREBP, ATF6, p53, HIF |

| Regulated by signals generated at the cell surface: |

| Resident in nucleus CREB, E2F1, ETS, ATMs, SRF, FOS-JUN, MEF2, Myc, MeCP2 Shuttle between nucleus and cytosol DREAM, FOXO Become activated in the cytosol, translocate to nucleus STATs, SMADs, NFκB, β-catenin, NFAT, Tubby, GLI, MITF |

From Brivanlou and Darnell, 2002.

IIIA GPCRs and Classical Second Messenger Signaling

GPCRs comprise an enormous family represented by over 800 genes in the human genome. They have a common structure characterized by seven transmembrane-spanning domains. While a significant percentage of these genes encode receptors for odorants, there are ≈200 distinct GPCRs that recognize a remarkably diverse assortment of known non-odorant ligands. They serve as detectors for neurotransmitters, hormones, peptides, photons, bile acids, amino acids, Ca2+ ions and tastants (including bitter, sweet and umami taste). There are also ≈150 orphan receptors for which the natural ligand remains unidentified. As of 2009, eight Nobel prizes have been awarded for contributions in the field of signal transduction via G proteins and second messengers. GPCRs are also targets (directly or indirectly) for at least 30% of all currently prescribed drugs, further attesting to the physiological and medical importance of this class of proteins (Pierce et al., 2002).

G-protein coupled receptors are so-named because they interact with a class of proteins known as heterotrimeric G-proteins (Oldham and Hamm, 2008), consisting of a Gα subunit (represented by 16 genes) and fused Gβ and Gγ subunits (six and 12 genes, respectively). Lipid modifications (e.g. palmitoylation, prenylation) keep the various subunits anchored to the plasma membrane where they interact with GPCRs.

Most of the specificity of the signal derives from the Gα subunit, which is allowed to couple to an effector when the receptor is engaged by its ligand. The major types of Gα subunits are:

• Gαs – couples to adenylyl cyclases (AC1–AC9) to generate the second messenger, cAMP

• Gαi/o – inhibits the activity of most adenylyl cyclases

• Gαq/11 – couples to phospholipase C and the Ca2+-phopshoinositide pathway

• Gα12/13 – ultimately engages the small GTP-binding protein Rho A, to alter the cytoskeleton.

Engagement of the GPCR with its ligand results in exchange of a GDP for GTP on the Gα subunit and dissociation of the heterotrimeric complex into free Gα and Gβγ dimers. This permits the GTP-bound Gα subunit to couple with its effectors (e.g. adenylyl cyclases or phospholipase C; see below). The Gβγ subunits also have biological activities that include interactions with ion channels, monomeric G-proteins (e.g. Rac, Cdc42) and PI 3-kinase. GPCRs can also interact (via heterotrimeric G proteins) with ion channels, e.g. the GIRK channels (G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channels).

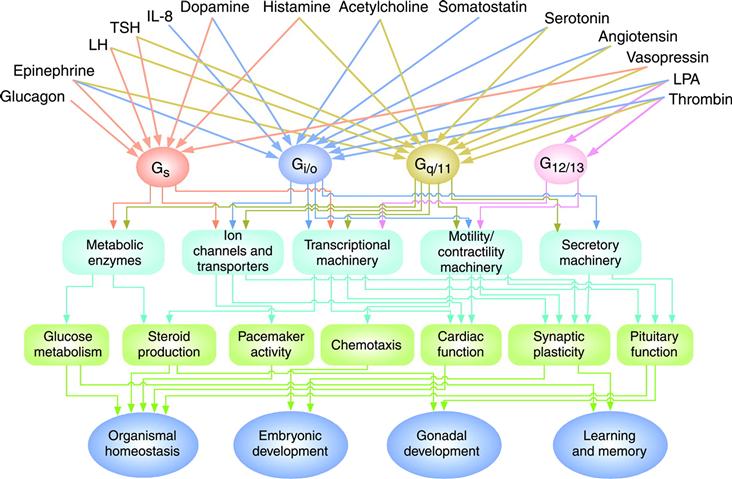

Figure 6.2 illustrates some of the more common stimuli and biological outputs of this signaling system (Neves et al., 2002). There are a few things worth pointing out. First, because of GPCR isoform diversity, a single type of extracellular ligand can activate multiple kinds of intracellular signaling pathways. It is also the case that certain GPCRs are promiscuous, i.e. it is possible for particular GPCRs to couple to more than one type of Gα subunit in order simultaneously to activate multiple pathways (Hofer and Brown, 2003). It is also noteworthy that communication via the vast majority of GPCR ligands ultimately converges on just two second messenger systems: the Ca2+/phosphoinositide (via Gαq/11) and cAMP signaling systems (via Gαs and Gαi/o). How these simple messengers manage to control so many biological functions is an exciting area of continuing investigation.

FIGURE 6.2 Regulation of biological functions through heterotrimeric G-protein pathways. Examples of regulatory networks that control functions via the four major classes of heterotrimeric G proteins are depicted. See text for further details. (Taken from Neves et al. (2002). Science. 296, 1636–1639, AAAS Publishers.)

IIIB Receptor Tyrosine Kinases and Receptor Serine/Threonine Kinases

Numerous growth factors, survival factors and hormones, such as insulin, exert their actions through receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). These are single-membrane spanning proteins that are represented by ≈20 different subfamilies. They generally form dimers upon engagement with their ligand (an exception is the insulin receptor, which is already in a dimeric configuration in the absence of insulin), causing tyrosine residues in a cytoplasmic domain of the receptor to become autophosphorylated. The RTK then assumes an active conformation that permits it to interface with several types of downstream signaling transducers. RTKs are also linked to scaffolding proteins that facilitate these processes. Major intracellular pathways that are turned on by RTK stimulation include:

1. Ras – the activated RTK is linked via adaptors proteins (Grb2 and SOS) to the small G protein ras which, in turn, activates another monomeric G protein known as raf. Raf is important in turning on the MAP kinase cascade (e.g. ERK1/2; see below)

2. PLCγ – activation of phospholipase Cγ generates InsP3/Ca2+ and DAG (see Ca2+-phosphoinositide pathway below)

3. PI-3kinase – generates the lipid PIP3 to activate Akt (protein kinase B; see below)

4. Src family kinases – these are part of a large family of non-receptor tyrosine kinases. They work by both helping to assemble signaling complexes and to phosphorylate tyrosine residues on targets within the complex.

The receptor serine/threonine kinases (RS/TKs) of the transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) superfamily are also single-membrane spanning receptors. RS/TKs are detectors for certain growth stimuli, including bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) and TGFβ (Moustakas et al., 2001). These receptors generally form tetramers and couple to the Smad signaling pathway (discussed below).

IIIC Small GTP-Binding Proteins

As the name suggests, these are small monomeric proteins that bind GTP, which results in the G protein assuming an “on” state. This reaction is generally catalyzed by a large assortment of guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs). When GTP is hydrolyzed to GDP, the G proteins are in the “off” state. GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) accelerate this process (Bos et al., 2007).

Monomeric G proteins (≈150 different ones) are important intermediaries in numerous types of signal transduction systems and can be subdivided into five general families: Ras, Rho, Rab, Ran and Arf. Ras proteins (36 genes) are control points for multiple types of signaling pathways (e.g. MAP kinase and PI-3 kinase pathways; see below). Many of the other G proteins (e.g. Rho family members) have key roles in the control of the cytoskeleton, while others (e.g. Rab, Arf) are involved in membrane trafficking. Ran is involved in nuclear transport.

IV Phosphorylation by Kinases and Other Post-translational Modifications

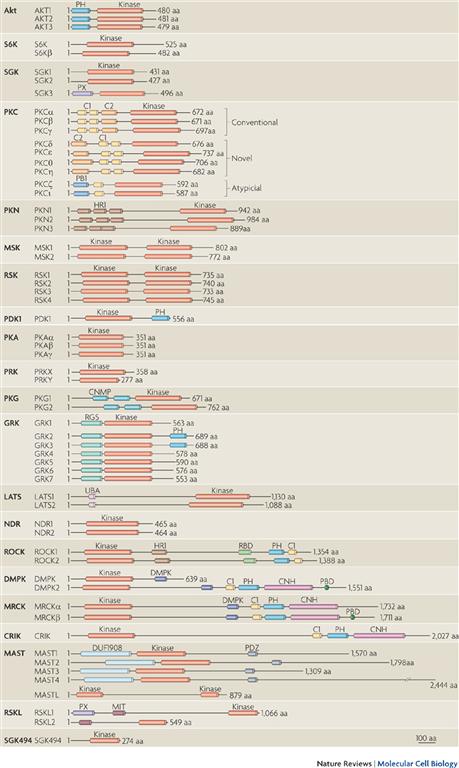

The most common motif for altering the activity of a target is through reversible phosphorylation of specific amino acid residues by a protein kinase (Pearce et al., 2010). These are usually serine or threonine residues or, in the case of tyrosine kinase family members, a tyrosine residue. Protein kinases have regulatory roles in all aspects of eukaryotic cell function and provide tremendous signal amplification. The domains of some of the more common kinases with similarity to the classical protein kinases A, C and G (PKA, PKC, PKG) are illustrated in Fig. 6.3. Phosphatases accelerate the removal of phosphate groups on phosphorylated proteins to terminate the signal.

FIGURE 6.3 Examples of kinases with structural similarities to protein kinase A (PKA), protein kinase G (PKG) and protein kinase C (PKC). (From Pearce, L.R., Komander, D. & Alessi, D.R. (2010). The nuts and bolts of AGC protein kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 11, 9–22.)

Other types of reversible modifications to amino acid residues are also used (albeit less commonly than phosphorylation) to control the activity of intermediates and final targets in signaling cascades. These include:

V Intracellular Signal Transduction Pathways

VA Cyclic AMP Pathway

The foundations of the second messenger concept were established nearly half a century ago when Sutherland and Rall identified a small heat stable factor that mediated the intracellular actions of the hormones glucagon and epinephrine on glycogen metabolism in the liver. The mysterious factor turned out to be cAMP, a discovery that earned Sutherland the 1971 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (Rehmann et al, 2007).

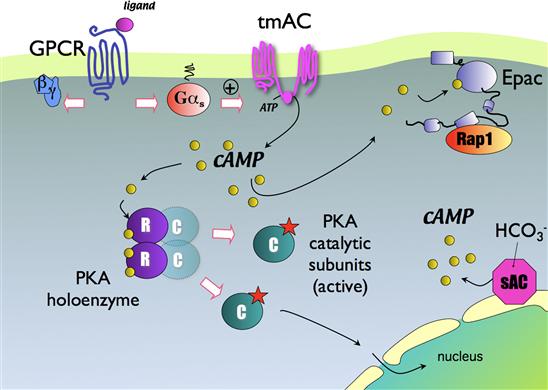

This small highly diffusible second messenger is produced mostly through the activation of GPCRs that are coupled via Gαs to adenylyl cyclases (ACs; Fig. 6.4). The conventional ACs are a family of nine membrane spanning proteins (AC1–AC9) that are regulated differentially by other signaling pathways (e.g. Ca2+). A given cell type may express several different isoforms of AC. Apart from the conventional ACs, there is also another route to cAMP production via a so-called “soluble” adenylyl cyclase (sAC or AC10). This AC is not a transmembrane protein, but it can nevertheless be localized to discrete regions of the cell (e.g. organelles) to provide localized cAMP signals. Because sAC is activated mainly by HCO3−/CO2 (it is also regulated by Ca2+) it has been considered to function as a metabolic sensor.

FIGURE 6.4 Basic features of the cyclic AMP signaling cascade.

Once cAMP is generated, it can bind to and alter the activity of three general types of effector proteins:

• cyclic nucleotide-gated channels (see Chapter 35)

PKA is without question the most important target of the cAMP signal. At rest, PKA exists as a four-protein complex known as a heterotetramer because it consists of two catalytic subunits and two regulatory subunits. When cAMP binds the regulatory subunits, it releases the catalytic subunits, which are then free to phosphorylate other proteins within the cell. Important PKA targets include ion channels (e.g. CFTR, AMPA receptors), metabolic enzymes (e.g. lipase) and cAMP-dependent transcription factors such as the prototypical CREB (cAMP response element binding) protein. Inputs from other signaling cascades, including Ca2+ and MAP kinase pathways, also converge on CREB to regulate its function.

Epac (exchange protein activated by cAMP) is a more recently identified effector of the cAMP signal for which there are two isoforms, Epac1 and Epac2. The best understood action of Epac is to enhance the GTP-ase activity of the small G proteins of the Ras superfamily, Rap1 and Rap2.

The cAMP signal is terminated by phosphodiesterases (PDEs), a complex family of enzymes with more than 20 members. Some of these isoforms of PDE also preferentially metabolize cyclic GMP (see below). PDEs are of major interest for drug development. Because the various isoforms can have tissue-specific distributions (e.g. in airway and cardiovascular systems), they may provide an avenue for controlling particular tissue functions using isoform-selective drugs.

VB Calcium Signaling Pathway: VOCs, ROCs, SMOCs, SOCs and Store Release

Calcium is a major second messenger used by virtually all cells. It is at the same time the simplest messenger, since no enzymes are needed to create or destroy this ubiquitous signal, and one of the most versatile, since it can convey information in many different compartments within the cell (e.g. local events within cytosol, mitochondria, ER lumen and extracellular space) (Hofer and Brown, 2003; Berridge et al., 2003). Moreover, signaling targets can respond differentially to specific types of signals. For example, many Ca2+ signals are oscillatory in nature and this pattern may preferentially activate one kind of target (e.g. an ion channel) while a sustained elevation in Ca2+ may ultimately activate another (e.g. a transcriptional cascade). As details of this system are covered in several other chapters in this volume (e.g. Chapters 13, 14, 42), we will present only a general overview of the Ca2+ signaling pathway here.

Ca2+ is normally maintained at very low levels in the cytosol (≈50 nM – this is very low if you consider that distilled water contains about 5–10 μM free Ca2+!) but it can rapidly become elevated as much as 10–20-fold through any number of different mechanisms:

1. VOCs: voltage-operated Ca2+ entry pathways (in excitable cells; see Chapter 21)

2. ROCs: receptor operated Ca2+ channels, activated by extracellular ligands such as glutamate or ATP (see Chapter 36)

3. SMOCs: second messenger-gated channels are opened by ligands generated inside the cell (cAMP, cGMP, DAG, arachidonic acid)

4. release from intracellular Ca2+ stores, especially the ER, following activation of intracellular Ca2+ release channels. These are Ca2+ selective channels typically located on the ER or SR membrane, and include InsP3R, release channels activated via cADPR, and RyR (see Chapter 42). These pathways are discussed below.

5. SOCs: store-operated Ca2+ entry channels are activated when the free concentration of Ca2+ in the ER lumen is reduced, for example following agonist/InsP3-induced release described in the next section.

VC The Ca2+-Phosphoinositide Pathway

GPCRs and RTKs elicit Ca2+ signals via the Ca2+-phosphoinositide pathway, a ubiquitous mechanism found in nearly all cell types (including excitable cells). Receptor engagement results in increased turnover by phospholipases (PLCβ for GPCRS and PLCγ for RTKs) that hydrolyze the plasma membrane lipid PIP2 to produce DAG (which remains associated with the bilayer) and a small diffusible hydrophilic molecule, InsP3. While DAG works to stimulate certain PKC isoforms, InsP3 is able to bind to a Ca2+ release channel on the ER membrane known as the InsP3 receptor. The ER continually sequesters Ca2+ via a pump known as the SERCA (sarcoendoplasmic Ca2+-ATPase; see Chapter 13) so that the free resting [Ca2+] is ≈500 μM in the ER lumen. Once the InsP3 receptor is opened, the cation floods out of the ER into the cytoplasm, generating a spike in cytosolic Ca2+ that subsides as the stores become emptied.

There is then a second and very interesting phase of the signal. The reduction in free [Ca2+] within the ER lumen is sensed by the luminal domain of a recently identified ER transmembrane protein known as STIM1. The decreased [Ca2+] causes STIM1 to aggregate in discrete zones of ER just under the plasma membrane and this leads to the activation of Ca2+ selective channels (mostly of the family of channels known as Orai channels) in the plasma membrane. Entry of Ca2+ through these channels typically generates a sustained phase of the Ca2+ signal that serves both as a source of Ca2+ for refilling the ER stores and as a signal for cellular targets that require a more persistent elevation for their activation. When the initiating stimulus is removed and InsP3 production ceases, the stores refill through the action of the SERCAs.

VD Cyclic ADP-Ribose and NAADP Pathways

Cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR) and nicotinic acid-adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) are related Ca2+-mobilizing messengers that are synthesized by a single enzyme (ADP ribosyl cyclase) from NAD+ and NADP, respectively. Curiously, the same synthetic enzyme also degrades cADPR. While cADPR is established to release Ca2+ from the ER, the physiological role of cADPR as a messenger has been somewhat controversial. The stimuli leading up to its production and the precise mechanisms by which it releases Ca2+ are, however, an active area of investigation.

NAADP is an extremely potent releaser of intracellular Ca2+ stores. The “two-pore channels” (TPC1 and TPC2) that reside in acidic endolysosomal compartments, were recently identified as bona fide targets of NAADP (Zhu et al., 2010). Since other intracellular Ca2+ release channels on the ER/SR (InsP3R and RyR) increase their open probability with increasing levels of cytosolic [Ca2+], a small spurt of Ca2+ from these acidic compartments may serve to “prime” the InsP3R and/or RyR, resulting in the generation of global Ca2+ signals.

VE PtdIns 3-Kinase Signaling

The membrane lipid constituent PIP2 has many biological functions that include regulation of ion channels and exocytosis. It is also an important precursor for other biologically active lipids (Wymann and Schneiter, 2008). As noted above, stimulation of GPCRs and RTKs can lead to activation of phospholipases (PLCβ or PLCγ, respectively) that metabolize PIP2 into InsP3 and DAG. Following receptor engagement, another parallel arm of these reactions can also be set in motion that involves phosphorylation of PIP2 by the enzyme phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase (PI3-kinase). A major target of the newly generated lipid species, PIP3, is another kinase, protein kinase B (PKB), more commonly known as AKT.

AKT is in effect recruited to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane by the freshly generated PIP3 because it contains a domain known as the Pleckstrin Homology (PH) domain, a common lipid-binding motif found in many lipid-dependent signaling proteins. Another player in this cascade, that also has a PH-domain, is PDK1 (phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1). When AKT and PDK1 are both recruited to the plasma membrane at the same time, PDK1 can phosphorylate and turn on AKT. Once activated, AKT phosphorylates or interacts with a wide range of targets (e.g. the kinase mTOR) to govern processes such as growth, protein, lipid and glycogen synthesis and apoptosis and proliferation.

PI3K/AKT signaling is arrested when PIP3 in the membrane becomes metabolized. This occurs through a specific enzyme known as PTEN. PTEN is a phosphoinositide phosphatase, i.e. an enzyme capable of removing phosphate groups from PIP3. The timely termination of the signal by PTEN is crucial. For example, during growth factor stimulation, the absence of PTEN leads to overstimulation of this pathway and inappropriate entry into the cell cycle even after the initiating stimulus has been removed. In fact, PTEN is defined as a tumor suppressor gene and PTEN mutations and deficiencies are prevalent in many types of human cancers. PTEN and other elements of the PI3K pathway are actively being investigated as targets for anticancer drugs.

VF Nitric Oxide (NO)/Cyclic GMP Signaling Pathway

Nitric oxide (NO) is a highly reactive, membrane permeable gaseous transmitter that is produced from the amino acid L-arginine by three different nitric oxide synthase (NOS) enzymes: eNOS (endothelial NOS), nNOS (neuronal NOS) and iNOS (inducible NOS) (Pacher et al., 2007). The nNOS and eNOS isoforms were named for the tissues in which they were originally identified and iNOS was so named because its expression could be induced in macrophages during inflammation, however, all three enzymes are actually widely distributed across different cell types.

NO is generated by eNOS and nNOS following an elevation in intracellular Ca2+. The iNOS enzyme, on the other hand, appears to be constitutively active (although regulated by other signaling molecules, particularly calmodulin) and can produce large amounts of NO for prolonged periods.

Once synthesized, the NO molecule has two major jobs. The first is to activate the so-called “soluble” guanylyl cyclase (sGC), which catalyzes the formation of cGMP (Rehmann et al., 2007) (which is more stable than NO) from GTP. Cyclic GMP in turn activates a cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) that can phosphorylate numerous downstream targets. The cyclic nucleotide can also activate channels in the plasma membrane (see Chapter 35).

Note that there is also a nitric oxide-independent route to cGMP production that occurs when certain peptide hormones, such as atrial natriuretic factor (ANP) and guanylin, bind to the transmembrane receptor known as particulate guanylyl cyclase (pGC). In addition to stimulating the formation of cGMP, the other major action of NO is to cause S-nitrosylation of the thiol-side chains of cysteine residues within protein targets, thereby altering their activity.

Ferid Murad, Louis Ignarro, and Robert Furchgott were awarded the 1998 Nobel prize for their discovery of NO, underscoring the physiological and clinical importance of this messenger. NO (originally known as EDRF or endothelial-derived relaxing factor) regulates smooth muscle relaxation and hence controls vasodilatation, bladder function, penile erection and gastrointestinal motility, to name but a few of its functions. Nitric oxide is also used by fireflies to elicit flashes of light and by plants to evade pathogens. Other endogenous “gasotransmitters” have recently been described, including carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) gas.

VG Redox Signaling through NADPH Oxidase (NOX)

It has long been appreciated that immune cells, such as neutrophils, take advantage of the regulated production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) via NADPH oxidases (Nox) in order to neutralize invading pathogens. It is now known that nearly all cell types utilize Nox (of which there are five isoforms, Nox1–Nox5) and the related dual-oxidase enzymes, Duox (represented by two isoforms, Duox1 and Duox2), to generate reactive oxygen species and peroxide (H2O2) metabolites that, in effect, serve as short-lived second messengers to regulate a wide variety of cell functions.

One route to the activation of NADPH oxidases occurs at the plasma membrane after stimulation of receptors for hormones, growth factors or cytokines linked to PI3-K. This enzyme converts PIP2 into PIP3 (see above) and the resulting PIP3 stimulates Nox, producing superoxides that can inactivate many protein targets (e.g. transcription factors, tyrosine phosphatases, PTEN) in the localized microdomain surrounding the Nox complex. It should be noted that substantial amounts of ROS can also be generated as a by-product of mitochondrial respiration.

VH Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Signaling

The MAPK pathway is a major multikinase signaling circuit that is often thought of in the context of growth factor stimulation (e.g. gene expression leading to growth and proliferation). In fact, it controls a multitude of cellular functions including metabolism, motility, apoptosis and long-term memory, to name a few. It receives inputs from multiple signaling systems, including GPCRs, RTKs, Toll receptors and integrins, and can also transduce the effects of environmental stresses (e.g. osmotic stress, UV radiation).

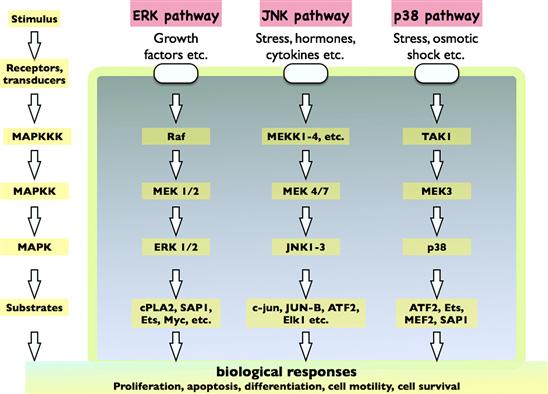

There are three major types of MAPK cascades named after their major transducers:

As shown in Fig. 6.5, the general scheme of this pathway involves the initial activation of a MAPKKK, which phosphorylates a MAPKK which, in turn, phosphorylates ERK, JNK or p38 (the MAPK). Although counterintuitive, it is thought that this arrangement of having three kinases in a row may actually conduct the signal faster than systems employing fewer numbers of kinases. Once phosphorylated, ERK, JNK and p38 frequently translocate to the nucleus to regulate gene expression.

FIGURE 6.5 MAP kinase cascades.

VI Nuclear Factor κB (NF-κB) Signaling Pathway

The NF-κB/Rel family (NF-κB1, NF-κB2, NF-κB3, RelB, and cRel) consists of a group of master transcription factors that remain latent in the cytoplasm until activated (Hayden et al., 2006; Perkins, 2007). It is commonly regarded as a “first responder” to a large, diverse, panel of stress-induced stimuli that include cytokines (e.g. tumor necrosis factor, TNFα), lymphokines, mitogens, hormones, carcinogens, inflammatory agents, tumor promoters, drugs, UV light, oxidative stress and certain growth factors. There are at least 150 types of extracellular stimuli known to activate this signaling system, which is present in nearly all cells. It also is involved in the control of osteoclastogenesis through the RANKL receptor and activation of receptors, known as Toll-like receptors, whose job it is to recognize pathogens and inflammatory cytokines. Each of these types of inputs requires a complex cast of players (not detailed here) that ultimately converge on the NF-κB pathway according to the following general scheme.

At rest, NF-κB is retained in the cytoplasm (and is therefore kept inactive) by “IκB” (inhibitor of NF-κB). IκB is a cytosolic resident that belongs to a family of six proteins responsible for masking the nuclear localization signal of NF-κB. However, in response to diverse stimuli, a kinase known as “IKK” (inhibitor of NF-κB kinase) becomes activated. There are three forms of IKK (IKKα, IKKβ and “NEMO”, a regulatory protein also known as IKKγ), which phosphorylate IκB, thereby tagging it for degradation by the proteasome. Liberated from IκB, NF-κB is now free to enter the nucleus, where it can bind to DNA and turn on expression of large gene sets, e.g. those involved in innate immune and stress responses. The NF-κB pathway also receives inputs from numerous other signaling systems to modulate its activity and is an important object of drug discovery efforts.

VJ Phospholipase D Pathway

There are more than 1000 types of biological lipids. Phospholipase D enzymes (two isoforms: PLD1 and PLD2) hydrolyze phoshatidylcholine, a ubiquitous lipid constituent of the bilayer, to generate the bioactive lipid, phosphatidic acid (PA). PLD1 is located principally on intracellular membranes (the ER, Golgi and endosomal membranes) and in caveolae of the plasma membrane. PLD1 becomes activated by elements downstream of GPCR or RTK stimulation (e.g. via PKC). PLD2 appears to not be activated by these stimuli and is mainly localized to the plasma membrane. Once synthesized, PA acts as a second messenger to regulate a number of enzymes, including protein phosphatases, mTOR and other targets that control budding and fusion, secretion, changes in cytoskeleton and proliferation (Cazzolli et al., 2006).

VK Sphingomyelin/Ceramide Signaling Pathway

Ceramides are bioactive lipids that can be generated enzymatically in response to stressful stimuli that include TNFα, radiation, chemotherapy drugs and through the activation of “death receptors” by a transmembrane protein known as Fas ligand on a neighboring cell. There are two routes to its formation: (1) from the breakdown of sphingomyelin (a constituent of the lipid bilayer, particularly the plasma membrane); or (2) through de novo synthesis (Hannun and Obeid, 2008).

Ceramide has several protein targets, including the protease cathepsin D, a particular isoform of PKC (PKCξ;) and ceramide-activated phosphatases. However, its action does not stop there. Ceramide is further converted to the lipid messenger sphingosine, which activates certain kinases. Like ceramide, sphingosine can drive apoptosis (programmed cell death) and cell cycle arrest.

This cascade continues even further, however, since sphingosine is the precursor for another potent bioactive lipid, sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P). S1P is generated when sphingosine kinase becomes activated by diverse stimuli that include growth factors (PDGF, IGF, VEGF), cytokines (IL-1, TNF), hypoxia and oxidized LDL to name a few (Wymann and Schneiter, 2008). S1P can act as a local extracellular messenger to stimulate GPCRs of the “EDG” family (specifically EDG1, 3, 5, 6 and 8) on the same cell or on neighboring cells. EDG receptors are coupled to the Ca2+-phosphoinositide signaling pathways.

VL Janus Kinase (JAK)/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STATs)

This relatively simple pathway mediates the actions of more than 30 different hormones and cytokines, including numerous interleukins (e.g. IL-2), interferons, growth hormone, erythropoietin and prolactin. It is frequently referred to as a “fast-track” for signaling because there are so few components between the initial activation of the receptor (RTK, GPCR, cytokine receptor etc.) and the translocation of activated STATs to the nucleus, where they bind the promoter region of responsive genes. There are four JAK family members (JAK1–JAK3 and TYK1) and seven STATs.

Typically, JAKs “prime” the ligand-bound cytokine receptor for its interaction with the STATs by phosphorylating specific tyrosine residues on the dimerized receptor. STATs dock onto the phosphorylated receptor and then themselves become phosphorylated by JAKs (which remain associated with the receptor). At this point the activated STATs disengage from the receptor and form dimers, rendering them competent to enter into the nucleus to complete their work as transcription factors.

VM Smad Signaling Pathway

Instructions from the TGF-β super-family of growth factors, including bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), are funneled via their serine-threonine kinase receptors on the cell surface into an intracellular system of transcription factors and regulators known as Smads (Moustakas et al., 2001). Smads exist as three different types: R-Smads, co-Smad and I-Smads. The R-Smads are receptor-regulated and become directly phosphorylated when TGF-β binds its receptor (through a multistep process), activating the R-Smads, Smad2 or Smad3. Alternatively, agonists of the BMP-type bind to their cognate receptors to activate Smad1, Smad5, or Smad8. Smad4 is known as a co-Smad, which serves to facilitate signaling by forming dimers with R-Smads that then translocate to the nucleus to elicit expression of target genes. I-Smads (Smad6, 7) compete with Smad4 to inhibit this process.

In addition to controlling developmental processes, these systems maintain important physiological functions in the adult. For example, BMP is involved in skeletal remodeling and controlling proliferation of cells within the intestinal stem cell niche. TGF-β also directs differentiation of maturing cells within the intestinal villus, a structure characterized by extremely rapid cell turnover.

VN Wnt Signaling Pathway

Wnt, Notch and Hedgehog (along with the TGF-β and receptor tyrosine kinase systems described above) are the major signaling pathways controlling early development throughout the animal kingdom. These pathways (Fig. 6.6) also exert important homeostatic and remodeling functions in adult organisms and are being increasingly indicted in the genesis of disease states, including tumorigenesis.

FIGURE 6.6 Wnt, Hedgehog and Notch pathways.

Wnts are extracellular lipoprotein growth factors that are encoded by 19 different genes in humans (Gordon and Nusse, 2006). Wnt binds to a receptor known as “Frizzled” (of which there are 10 types) that resembles the seven membrane-spanning receptors of the GPCR family. In the “canonical” (i.e. orthodox) Wnt/β-catenin pathway, Wnt also binds to a co-receptor of the LRP family and these proteins then form a complex with an intracellular protein known as disheveled. The Wnt pathway is somewhat unusual in that ligand binding leads to downstream steps that turn off constitutive degradation of the transcription factor β-catenin by a destruction complex formed by Axin, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) protein and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3). This allows β-catenin to accumulate to high levels and act as a transcription factor in the nucleus. There also exist β-catenin-independent modes of Wnt/Frizzled signaling. Among its many functions, the Wnt pathway is known to turn on proliferation of intestinal stem cells. It is noteworthy that mutations in members of this pathway are frequently observed in colon cancer cells.

VO Hedgehog Signaling

The hedgehog gene was so named following the discovery of a Drosophila mutant possessing anterior-posterior patterning defects. This animal also presented a spiky hedgehog-like appearance due to the condensed solid lawn of denticles (cuticular extensions) on the body surface. The hedgehog protein (of which there are three in vertebrates, Indian hedgehog, desert hedgehog and sonic hedgehog) is a secreted morphogen that has recently emerged as an important target for anticancer drugs, with several compounds in clinical trials. This pathway is active in adult hematopoietic stem cells and hair follicles, where it signals the transition to the growth phase. Components of this pathway are frequently mutated in skin cancer cells.

Hedgehog (often abbreviated Hh) is secreted from cells by an unusual pathway (Chen et al., 2007). The cytosolic protein first acquires certain unique lipid modifications that allow it to be recognized and exported from the cell by a transmembrane enzyme known as dispatched. Carrier proteins in the extracellular milieu facilitate the delivery of Hh to target cells, where it binds a receptor called patched. At rest, the function of patched is to repress another transmembrane protein, smoothened. The job of smoothened is to keep transcription factors of the GLI family (three in mammals: GLI1–GLI3) in a dormant state. Binding of Hh to patched therefore effectively allows for the activation of GLI. An interesting feature of the preceding steps is that they take place almost entirely on the primary cilium of the target cell, a specialized surface projection present in virtually every vertebrate cell type. Once GLI is generated, it translocates to the nucleus where it controls transcription of genes involved in proliferation.

VP Notch Signaling

Notch is a cell surface receptor that is an integral component of a relatively simple signaling pathway used extensively throughout the animal kingdom for controlling development (Bray, 2006). It takes its name from a notched wing phenotype in Drosophila first identified in genetic studies performed nearly a century ago. Flies with the notch mutation have increased numbers of neurons but less epidermal tissue.

There are four human Notch receptors (Notch1–4). Notch is unusual because most of its ligands are transmembrane proteins, therefore it becomes activated only when there is contact between receptor and ligand on a neighboring cell. This pathway is also very straightforward in that it signals without any amplification. The cascade starts when the Notch receptor encounters a transmembrane ligand on the communicating cell. One such ligand is known as Jagged and another is known as Delta. This interaction initiates two proteolytic cleavage events (not detailed here) that ultimately liberate an intracellular fragment of the Notch receptor called NICD (Notch intracellular domain). NICD works as a transcription factor that then translocates to the nucleus to alter gene expression. The signal is terminated via proteolytic degradation of NICD.

It is possible to envision how this arrangement permits one cell to influence gene expression in another and thereby allow an organism to assemble complex multicellular structures with similar or dissimilar phenotypes. In adult organisms, Notch signaling is involved in structural homeostasis, response to injury and repair. For example, this can take the form of influencing of the fate of intestinal cells destined for either secretory or absorptive lineages, and during angiogenesis.

VQ Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Signaling

This pathway provides a route for transmitting information from the ER to the nucleus (Ron and Walter, 2007). The ER stress response starts when polypeptides that are being processed in the ER lumen lose their tertiary structure or there is an overload of ER proteins. This can occur physiologically, e.g. if there is a sudden upregulation of protein production so that the protein-folding machinery in the ER becomes overwhelmed, and during viral infections. It also occurs when there is a persistent loss of Ca2+ from the ER lumen, causing Ca2+-dependent chaperones to allow unfolding of the proteins they are escorting (note that this underscores the overall importance of reliable ER Ca2+ homeostasis, apart from its signaling function).

The presence of unfolded polypeptides in the lumen is sensed by several different systems (Lai et al., 2007). For example, this condition elicits processing and release of an ER-resident transcription factor ATF6, which ultimately travels to the nucleus, where it induces the expression of more chaperone proteins. Another attempt to correct the problem is mediated by the ER kinase PERK, which ultimately turns off protein synthesis. Persistent unfolded protein responses result in apoptosis through other ER stress sensors.

VR AMPK Signaling: Metabolic Sensors

Cells need a way to communicate and adapt to changes in energetic status. When ATP levels are low, AMP is increased and this is detected by a fuel-sensing kinase, AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase) (Steinberg and Kemp, 2009). AMPK directs processes that allow the cell to correct its energy deficit by turning on ATP-generating processes (glycolysis, fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial biogenesis) while inhibiting activities that use up ATP (gluconeogenesis, glycogen, fatty acid and protein synthesis). It also directly influences appetite-regulation in the hypothalamus.

AMPK is interesting in that it not only senses local AMP concentrations, but it also integrates the actions of hormones involved in energy balance such as leptin, ghrelin, adiponectin, glucocorticoids, insulin, as well as cannabinoids. It has generated recent excitement due to its apparent role in mediating the longevity-producing effects of calorie restriction.

VI Conclusions

The preceding provides a brief and highly simplified snapshot of the major signaling pathways involved in the control of physiological processes. It highlights their beautiful diversity but also hints at their overwhelming intricacy. For the physiologist, the interconnected nature of these signaling networks means that perturbation of any one component may result in unforeseen alterations in other aspects of a cell’s function. Systems biology approaches and new methods for monitoring signaling molecules with high spatiotemporal resolution (e.g. fluorescence- and GFP-based sensors) are among the tools that are currently being used to help unravel this complexity. The good news for those of us studying the regulation of physiological function is that each cell type and organ system will present us with diverse and exciting challenges for a long time to come.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Berridge, M. (2009). Cell Signalling Pathways. In www.cellsignallingbiology.org ed.). Portland Press Limited.

2. Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:517–529.

3. Bos JL, Rehmann H, Wittinghofer A. GEFs and GAPs: critical elements in the control of small G proteins. Cell. 2007;129:865–877.

4. Bray SJ. Notch signalling: a simple pathway becomes complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:678–689.

5. Brivanlou AH, Darnell Jr JE. Signal transduction and the control of gene expression. Science. 2002;295:813–818.

6. Cazzolli R, Shemon AN, Fang MQ, Hughes WE. Phospholipid signalling through phospholipase D and phosphatidic acid. IUBMB Life. 2006;58:457–461.

7. Chen MH, Wilson CW, Chuang PT. SnapShot: hedgehog signaling pathway. Cell. 2007;130:386.

8. Gordon MD, Nusse R. Wnt signaling: multiple pathways, multiple receptors, and multiple transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22429–22433.

9. Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:139–150.

10. Hayden MS, West AP, Ghosh S. SnapShot: NF-kappaB signaling pathways. Cell. 2006;127:1286–1287.

11. Hofer AM, Brown EM. Extracellular calcium sensing and signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:530–538.

12. Lai E, Teodoro T, Volchuk A. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: signaling the unfolded protein response. Physiology (Bethesda). 2007;22:193–201.

13. Moustakas A, Souchelnytskyi S, Heldin CH. Smad regulation in TGF-beta signal transduction. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:4359–4369.

14. Neves SR, Ram PT, Iyengar R. G protein pathways. Science. 2002;296:1636–1639.

15. Oldham WM, Hamm HE. Heterotrimeric G protein activation by G-protein-coupled receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:60–71.

16. Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:315–424.

17. Papin JA, Hunter T, Palsson BO, Subramaniam S. Reconstruction of cellular signalling networks and analysis of their properties. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:99–111.

18. Pearce LR, Komander D, Alessi DR. The nuts and bolts of AGC protein kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:9–22.

19. Perkins ND. Integrating cell-signalling pathways with NF-kappaB and IKK function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:49–62.

20. Pierce KL, Premont RT, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:639–650.

21. Rehmann H, Wittinghofer A, Bos JL. Capturing cyclic nucleotides in action: snapshots from crystallographic studies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:63–73.

22. Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529.

23. Steinberg GR, Kemp BE. AMPK in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:1025–1078.

24. Wymann MP, Schneiter R. Lipid signalling in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:162–176.

25. Zhu MX, Ma J, Parrington J, Galione A, Evans AM. TPCs: Endolysosomal channels for Ca2+ mobilization from acidic organelles triggered by NAADP. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1966–1974.