Palaeozoic tropical rainforests and their effect on global climates: is the past the key to the present? … The Palaeozoic evidence clearly confirms that there is a correlation between levels of atmospheric CO2 and global climates. However, care must be taken in extrapolating this evidence to the present-day tropical forests, which do not act as a comparable unsaturated carbon sink.

—Cleal and Thomas (2005, 13)

THE EFFECT OF THE LATE PALEOZOIC ICE AGE IN EARTH HISTORY

What were the effects of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age in Earth history? First, the climatic conditions created by the ice age—a planet with cold poles, arid temperate zones, and an ever-wet, ever-warm tropical zone—were perfect for forming what Stephen Greb and his colleagues, as noted in chapter 3, called the “largest tropical peat mires in Earth history” (Greb et al. 2003, 127), perfect habitats in which the peculiar lycophyte trees flourished. Those peat mires and lycophyte tropical rainforests later fossilized to produce the worldwide distribution of Carboniferous coal deposits that would be used by humans over 250 million years later as the principal source of energy in the process of industrialization, first in Europe and then around the world—continuing to the present day in developing countries like China and India. In this chapter, we will examine how the climatic and biological processes that created these massive coal deposits during the Late Paleozoic Ice Age have affected our modern world.

Legacy 1: The Industrial Revolution?

Humans learned how to create fire and burn wood in prehistory. In fact, the use of fire in the human lineage is much older than the 300,000-year-old species Homo sapiens—we know from the fossil record that the older hominin species Homo erectus also learned how to used fire some 1.5 million years ago. We also know from historical records that our ancestors knew about coal, the strange black rocks that they found lying on the ground in some regions of the Earth—black rocks that could ignite and burn. However, for the great majority of our history, our ancestors burned wood for energy. Later humans learned how to make charcoal from wood by heating wood in kilns, cooking out volatiles like water and partially oxidizing the remaining carbon. Charcoal is a more concentrated form of burnable carbon; that is, charcoal has a higher energy content per unit mass than ordinary wood. Everyone who has ever used charcoal to grill hamburgers or other food on a summer day is familiar with this fact, recognizing that it would take a much larger mass of wood to accomplish the same amount of cooking (the amount of wood required would not fit in your average backyard grill!).

In Europe, people first began to burn coal to create hotter fires in order to melt metal ores from their rock matrix and to soften metal for working it into tools and ornaments. People rapidly discovered that burning less concentrated-carbon forms of coal, such as bituminous coal, created irritating and unhealthy air pollution and thus began to use more concentrated-carbon forms of coal, such as anthracite, for domestic purposes like heating their homes.

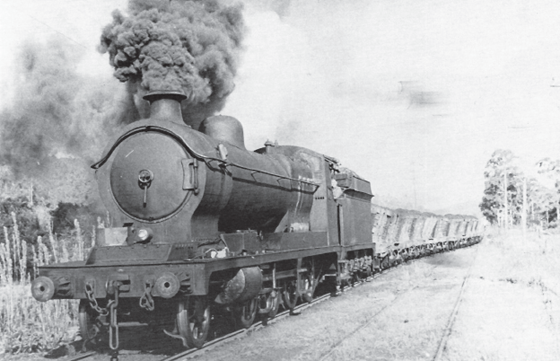

Then the first primitive steam engines were invented. It was discovered that the pressure produced by boiling water into steam could be controlled and used to power machines that could, for example, turn the massive heavy millstones that were used to grind grain into flour. These steam engines were much more powerful than traditional sources of energy for grinding grain, such as using the energy of flowing water over waterwheels or connecting the millstones to a team of horses that walked around and around in circles. More experimentation produced more efficient steam engines, until the Scot James Watt patented the first efficient, modern-type steam engine in 1769. Producing the steam power in these engines required a very hot fire—and coal was the perfect fuel for that fire. Even today, it is amazing to ride on a train powered by a now-antique steam engine. The steam engine produces so much power that it not only propels itself, but it also pulls along its source of energy—a second car loaded with coal—as well as a whole series of cars connected to the train behind the coal car. Those cars are heavy, and they can be filled with even heavier loads of coal ore from coal mines in freight cars (fig. 7.1) or loads of people in passenger cars. Yet the steam engine at the front of the train pulls them all, powered by the energy released by burning the coal in the coal car.

FIGURE 7.1 Coal-powered, steam-engine train hauling freight cars loaded with coal ore in Australia.

Source: Photograph courtesy of Wikipedia/Christchurch. Reprinted under permission of the GNU Free Documentation License.

Next, just as people discovered that charcoal could be made by cooking off the volatiles in wood, people discovered that coke could be made by cooking coal. Burning coke could then produce extremely hot fires in very large blast furnaces, and those huge blast furnaces could be used to produce much less expensive, high-quality iron in massive amounts—cheap iron that could be used to make more machines, particularly steam-driven machines.

Thus was born the technology needed to drive the European Industrial Revolution, beginning in Britain in the mid-1700s. The Industrial Revolution probably began first in Britain because, by geologic coincidence, large amounts of coal-containing strata and metallic-ore-containing rocks were both present. And those coal strata in England, Wales, and Scotland are almost all Carboniferous in age. Then the Industrial Revolution spread to continental Europe—particularly to southern Belgium and the middle region of Germany, where coal-bearing strata were also present. And those coal strata in the Ardennes of Belgium and the Ruhrgebiet of Germany are almost all Carboniferous in age. The Industrial Revolution spread around the world in the 1700s and 1800s, following the geologic outcrops of Carboniferous coal. As Nick Lane pointed out (see chapter 2), 90 percent of all the coal strata on Earth were deposited during the height of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age—in the time interval from the Serpukhovian Age in the Early Carboniferous to the Wuchiapingian Age in the Late Permian (Lane 2002, 84). Coal was originally present on the surface of the Earth, where early humans discovered that these peculiar black rocks could burn. With the need for coal to fuel the Industrial Revolution, intensive mining of coal spread around the world. Coal strata are relatively shallow and could be mined by open-pit excavations or shallow mine tunnels underground. As the shallow deposits of coal were mined out, deeper underground mines were dug, and entire mountain tops were removed in some regions of the Earth to reach the coal buried at depth. The mining and burning of coal for energy continues to the present day, but most of the coal burned today is used to produce electricity, not to power steam engines.

The powerful steam engines of the 1700s, 1800s, and early 1900s have been replaced today by an even more powerful, more efficient type of engine—the internal combustion engine. The invention and near-universal use of internal combustion engines today was made possible by a new type of energy source—petroleum—and its refined products such as gasoline and jet fuel. Unlike coal, large quantities of petroleum are not present on the surface of the Earth or at shallow depths underground. It was only after people perfected deep-drilling machines—the early ones powered by steam engines—that abundant petroleum became available as an energy source.

Legacy 2: Modern Global Climate Change?

It is no accident that climate scientists divide the recent history of carbon-dioxide levels in the Earth’s atmosphere into “preindustrial” and “industrial” phases, in recognition of the atmospheric effect of the tons of coal that has been burned since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. The preindustrial amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was 0.03 percent—that is, in the entire recorded human history of burning wood and charcoal, over 6,000 years, the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere did not exceed 0.03 percent. At the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, humans began to burn coal in vast quantities, and the present-day level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has risen to 0.04 percent in less than 200 years.

It is an empirical observation, a fact, that the Earth is heating up. Combining that fact with the fact that the amount of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has vastly increased in a tiny amount of time on geologic timescales has led climate scientists to conclude cause and effect—that is, that the industrially driven1 increase in the carbon-dioxide content of the atmosphere has caused the Earth to retain more heat in the atmosphere instead of losing it to space and, as a result, the planet has become hotter. As 90 percent of the coal in the Earth’s strata that has been burned since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution was deposited during the Late Paleozoic Ice Age, by extension one could blame the Late Paleozoic Ice Age for modern global climate change!

However, as one might expect, the situation is more complicated than that, and one cannot blame the Late Paleozoic peat bogs and tropical mires for everything. The industrial burning of coal is clearly a major culprit in the increase of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere, but since about the mid-1900s, vast quantities of petroleum have been burned, and the burning of petroleum has also added tonnes of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. It is usually impossible to determine how old that petroleum was—was it formed from organics deposited during the Late Paleozoic Ice Age or from some other geologic time period? Petroleum is a liquid, and a slippery liquid at that, and it easily migrates within rocks under the influence of gravity and differential pressure within the rock. Petroleum can accumulate in vast pools deep underground that are very distant from the original strata in which the petroleum formed.

Another complicating factor is that not only has the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere increased rapidly in less than 200 years, but the number of human beings on the Earth has also increased rapidly in the same period of time. In the early 1800s, early in the Industrial Revolution, there were about one billion human beings present on the Earth. Two hundred years later, at the beginning of the third millennium, the number of human beings on the Earth has increased to 7.6 billion. All of those people have depended primarily on energy from burning hydrocarbons—first coal, then petroleum—and that burning of hydrocarbons has added carbon dioxide to the Earth’s atmosphere. If the Earth’s human population had remained stable at around one billion individuals throughout those 200 years, clearly only a small fraction of the coal and petroleum that has been burned during that time interval would have been burned—and the Earth would be a much cooler (and less crowded) place.

Still, the fact remains that all of that Carboniferous coal (and petroleum, whatever age it happens to be) was burned for energy—and continues to be burned today. Where is the Earth headed in the future? Are we headed for a hothouse world like the Earth that existed in the Early Triassic—a world, described in detail in chapter 6, so hot that the tropical zones were essentially lethal, a world in which complex plant and animal life was confined to latitudes higher than 30° in the Northern Hemisphere and 40° in the Southern Hemisphere?

Legacy 3: The Successful Invasion of Land by Animals?

A twin result of the huge size and the peculiar growth pattern of the trees in the ancient lycophyte rainforests was the massive removal of carbon dioxide from the Earth’s atmosphere, the fixation of the carbon from carbon-dioxide molecules into plant tissues, and the burial of those carbon-rich plant tissues in bogs where they would later be fossilized into coal. Simultaneously, the oxygen released in fixing carbon during plant photosynthesis resulted in a massive injection of free oxygen into the Earth’s atmosphere during the Late Paleozoic Ice Age. That abundance of atmospheric oxygen led to the evolution of gigantism in both marine and land animals and, on land, in both arthropod and vertebrate clades of animals, as we saw in chapter 4.

In the vertebrate clade of animals, the initial boost of atmospheric oxygen, it is argued, was a major assist in both the final invasion of land by the tetrapods in the Visean Age of the Carboniferous and in the evolution of the first amniotes (Graham et al. 1995, 1997; McGhee 2013). As outlined in chapter 4, Jeffrey Graham and his colleagues have pointed out that the hyperoxic Carboniferous atmosphere enabled the previously aquatic tetrapods of the Devonian to obtain more oxygen with their primitive lungs, to decrease the amount dehydration they experienced in air breathing, and to boost their metabolic rates so they could move more energetically and endure the constant pull of gravity experienced in moving on dry land.

The key innovation in the successful invasion of land by vertebrates was the evolution of the amniote egg and the anatomical antidehydration adaptations that characterize the amniote animals. The hyperoxic Carboniferous atmosphere would have allowed tetrapods to develop larger eggs and, at the same time, to minimize water loss from those eggs (Graham et al. 1997). With an atmosphere rich in oxygen, the egg could absorb more oxygen per unit surface area of the egg. A larger egg has a larger internal volume (hence more space for extra tissue layers and fluid in addition to the embryo) with a relatively smaller external surface area (thus less water loss across that surface area to the outside world) than a small egg. The amniote egg is an innovative, two-layer adaptation to protect the developing embryo from dehydration in the harsh, dry-air environments of the terrestrial realm. First, the embryo is enclosed in a water-filled region contained by the surrounding amniotic membrane. In essence, rather than floating in an actual pond of water as amphibian embryos do, the amniote embryo floats within its own private amniotic pond. Second, the outside layer of the egg is a tough shell rather than the soft, gelatinous outer covering of the amphibian egg. Both of these layers help protect the embryo from serious water loss and death by dehydration. Thus the amniotes can lay their eggs on dry land and have them survive. This is not true of most amphibians. Their eggs will rapidly dehydrate if exposed to dry air, shriveling up and shrinking as moisture is lost to the atmosphere, and the embryo will die.

Finally, a large container of food for the embryo is enclosed within the amniote egg—the yolk sac. Thus the embryo can develop to a considerable degree within the egg itself, feeding on nutrients from the yolk sac, rather than hatching out of the egg at an early growth stage and foraging for food in a free-swimming larval stage, as in many amphibians. In consequence, the amniotes have direct development—there is no larval stage. What emerges from an amniote egg looks like a small, scaled-down version of the adult animal. In contrast, what emerges from a frog egg—a tadpole—looks like a fish, not a frog. Fish, of course, need water to swim in; a hatchling tetrapod amniote does not.

The amniotes were the victorious conquerors of land in the clade of the vertebrate animals.2 That victory was achieved by the evolution of the amniote egg, which freed the vertebrates from the constraint of having to reproduce in or near a body of water such as a river or lake. Prior to this innovation, tetrapods still laid their eggs in water, much like fish—and many of the non-amniote tetrapods, the amphibians, still do so today. Free from this constraint, the amniotes invaded the highlands and dry areas of the Earth far from standing bodies of water.

Just as the amniotes were the final conquerors of land in the vertebrate clade, the winged insects were the victorious conquerors of land in the clade of the arthropods (McGhee 2013). The hyperoxic atmosphere of the Carboniferous, it is argued, was also a major assist in the evolution of the winged insects, as we considered in chapter 4. Flying is a highly energetic activity that requires a lot of oxygen. The arthropods invaded land back in the Silurian, long before the vertebrates emerged from the water and the start of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age (McGhee 2013). Why, then, did it take them so long to take the next evolutionary step, to develop flight? The development of a hyperoxic atmosphere in the Carboniferous and the evolutionary diversification and spread of the flying insects during the Late Carboniferous may not be a coincidence (Graham et al. 1995, 119, fig. 2). With the evolution of flight, the insects could disperse over huge areas of land in a very short period of time—the world was theirs for the taking. Only much later, in the Late Triassic, would the vertebrates evolve powered flight in the clade of the reptiles with the first pterosaurs.

Legacy 4: The Evolution of Mammals and Dinosaurs?

The decline and depletion of free oxygen in the atmosphere following the end of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age and the catastrophic Emeishan and Siberian LIP eruptions, it is argued, was a major impetus for the evolution of yet more efficient respiratory metabolisms—and eventually the evolution of endothermic metabolisms—in both the synapsid and reptilian clades of vertebrates, and the eventual evolution of both mammals and dinosaurs (Graham et al. 1995, 1997). Geologic history—the very existence of the Mesozoic and Cenozoic Eras of geologic time—would not have developed the way it did if these two major groups of land animals had not evolved. Every schoolchild knows that the Mesozoic was the Age of Dinosaurs and the Cenozoic is the Age of Mammals. They may not be aware, however, that both the dinosaurs and the mammals evolved in the Late Triassic, and that the ecological conditions on land that resulted from the end of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age may have contributed to the evolution of both groups.

Some may argue that the evolution of dinosaurs and mammals is not really a legacy of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age but rather a legacy of the Emeishan and Siberian LIP eruptions, which produced the conditions that resulted in oxygen depletion in the Earth’s atmosphere at the end of the Permian. Still, the hyperoxic atmosphere created by the Late Paleozoic Ice Age set the stage for the environmental selective pressures that would result from the collapse of that atmosphere, and for the onset of the hypoxic and poisonous atmospheric conditions in the latest Permian and early Triassic. As we considered in detail in chapter 4, Graham and colleagues have argued that the onset of hypoxia in the latest Permian and earliest Triassic triggered the evolution of the four-chambered heart, and perhaps full endothermy, in the therapsids within the synapsid clade (Graham et al. 1997). In the reptilian clade, we know that four-chambered hearts evolved in the Early Triassic, as the crocodilian archosaurs appear in the fossil record at this time and they possess four-chambered hearts. Still, as discussed in chapter 4, the oldest known (as yet) true mammals and dinosaurs appear in the fossil record in the Late Triassic—at least 15 million years after the Late Permian–Early Triassic hypoxic interval of time.

Legacy 5: The Destruction of the Paleozoic World?

The ecological shocks of the successive phases of glaciation during the Late Paleozoic Ice Age triggered a series of extinctions that progressively winnowed and depleted Paleozoic marine world animals in the Earth’s oceans. The Frasnian, Famennian, and Serpukhovian extinctions all preferentially eliminated marine animals that belonged to the Paleozoic world fauna, and preferentially spared marine animals that belong to the modern world fauna (Sepkoski 1984, 1990, 1996; Stanley 2007). We know that the Famennian and Serpukhovian extinctions were triggered by Late Paleozoic Ice Age glaciations, and, as discussed in chapter 1, evidence exists that the Frasnian extinction was as well. In essence, the winnowing effect of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age glacially induced extinctions resulted in a Paleozoic marine world fauna that was progressively weakened and eventually could not withstand the catastrophic environmental changes triggered by the Emeishan and Siberian LIP eruptions. As discussed in chapter 6, the hot, acid, poisonous seawaters of the latest Permian oceans were too much for the Paleozoic fauna, and the 200-million-year old ecological structure of the Paleozoic marine world collapsed, never to recover (figs. 6.10, 6.11; table 6.6).

In contrast, the Paleozoic terrestrial world was largely the product of the terrestrial climatic conditions created by Late Paleozoic Ice Age, as discussed in chapter 6; how, then, can that world’s demise be attributed to its creator? It is the end of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age that was the harbinger of the end of the Paleozoic terrestrial world, and thus one may argue that both the existence of and the end of the Paleozoic terrestrial world were a legacy of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age. This causal relationship can be seen most clearly in Olson’s extinction, which we considered in detail in chapter 5. The waning of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age in the Early Permian triggered major contractions in the ever-warm, ever-wet equatorial zone of the Earth, and major elements of the terrestrial vertebrate fauna of the Paleozoic terrestrial world died out as a result. One could argue that the waning of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age produced its own winnowing effect in preferentially eliminating species of the Paleozoic terrestrial world fauna, resulting in a weakened fauna that could not withstand the catastrophic environmental changes triggered by the Emeishan and Siberian LIP eruptions in the Late Permian.

On the other hand, it can be counterargued that the destruction of the Paleozoic World is not really a legacy of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age but rather a legacy of the Emeishan and Siberian LIP eruptions; those eruptions produced the catastrophic environmental conditions that lethally heated and poisoned vast areas of both the seas and the land of the Earth, and the very atmosphere of the entire planet. The counterargument would be that had it not been for the Emeishan and Siberian LIP eruptions, the characteristic faunas of the Paleozoic world might have survived. This hypothetical possibility is but one of many that we will explore in the next sections of the chapter.

What If the Late Paleozoic Ice Age Had Never Happened?

From the perspective of human history, this question has major implications. If there had been no Late Paleozoic Ice Age, then there would have been no Earth with a tropical zone with huge expanses of lycophyte rainforests from 326 to 254 million years ago (tables 3.2 and 5.1). If there had been no lycophyte rainforests, then there would have been no massive coal deposits in Carboniferous strata—indeed, there would have been no “Carboniferous” at all in the geologic timescale. If the Carboniferous coal strata had never existed, would there ever have been an industrial revolution?

From prehistoric times we have burned wood for heat—heat to keep our habitats warm and heat to cook our food. Wood is readily available at the Earth’s surface, and it is also a renewable resource, as new trees can be grown to replace old ones that have been cut and used for fuel. However, neither wood nor charcoal made from wood contains enough energy per unit mass to efficiently fuel a steam engine—for that we need coal. In human history, coal also was initially readily available at the surface of the Earth, or only shallowly buried beneath that surface. Yet 90 percent of the coal that was present in the Earth’s strata was formed during the Late Paleozoic Ice Age, and if the Late Paleozoic Ice Age had never occurred, then that coal would not have existed. How long would a nascent industrial revolution have lasted that was fueled by only 10 percent of the coal that was used to fuel the historical Industrial Revolution? In an alternative world in which the Late Paleozoic Ice Age had never occurred, could humankind have quickly made the jump—while those meager 10 percent of coal supplies still lasted—from steam engines to the use of petroleum and the invention of the internal combustion engine?

The problem with petroleum is that it is usually not readily available at the Earth’s surface—or even shallowly below that surface. It takes powerful drilling machines to reach the petroleum pools located deep beneath the surface of the Earth. In an alternative world in which the Late Paleozoic Ice Age had never occurred, would humankind have used its coal-fired steam engines to drill for oil before the coal ran out? Or would that alternative humankind have remained in the preindustrial stage of our own world, forever existing in small cities and predominantly agrarian communities that used wood for fuel, unaware of the existence of the vast pools of oil buried deep beneath the surface of the Earth?

Clearly our modern dilemma of carbon-dioxide-induced global warming would not have occurred if the Late Paleozoic Ice Age had not occurred, as the vast deposits of coal that formed in that ice age would never have existed to be burned by humans. If the Industrial Revolution had never occurred, the human population itself might not have exploded as it did; in an alternative world in which the Late Paleozoic Ice Age had never occurred the human population might have grown at a much slower rate, fueled solely by our intellectual advances in more efficient agricultural methods to produce more food and our advances in more efficient medical methods to preserve and prolong life.

The question “What if the Late Paleozoic Ice Age had never happened?” also has major implications for Earth history and evolutionary ecology. If the great lycophyte tropical rainforests had never existed, the hyperoxic atmosphere of the Earth during much of the Carboniferous–Permian interval of geologic time also would never have existed, as those peculiar rainforests not only acted as massive carbon sinks but also released tons of free molecular oxygen into the atmosphere. In the absence of a hyperoxic atmosphere, the convergent evolution of the numerous giant animals that we considered in detail in chapter 4 would never have happened. Giant griffenflies would never have soared through the skies of the Earth, alligator-size millipedes would never have crawled through the peat bogs and rainforests below, and so on.

However, there is a more serious side to this question than the potential absence of animal gigantism in the Carboniferous and Permian. Without the energetic boost of that oxygen-enriched atmosphere, would the tetrapods have finally managed to emerge from the rivers and lakes and become fully terrestrial in the Early Carboniferous? Without that hyperoxic atmosphere, would the amniotes have evolved? Without extra oxygen, would the tracheal-breathing insects have finally managed to perfect the highly energetic activity of flight? Or, in an alternative world in which the Late Paleozoic Ice Age had never occurred, would the tetrapods have remained in the aquatic evolutionary stage, and if the amniotes had never evolved, would the land areas of the Earth have been populated by amphibian vertebrates only? Within the terrestrial arthropods, would the insects have remained grounded in the mode of life in which arthropods had previously existed for some 100 million years since their initial invasion of land back in the Silurian?

As discussed in the first section of the chapter, we also know that the Famennian and Serpukhovian extinctions were triggered by the Late Paleozoic Ice Age glaciations, and evidence exists that the Frasnian extinction was as well. If the Late Paleozoic Ice Age had never happened, then the glacially induced Famennian and Serpukhovian—and possibly the Frasnian—extinctions would never have happened. These events were the seventh, sixth, and fourth most ecologically severe biodiversity crises in Earth history (table 1.3). How would our Earth have been different if these crises had never happened?

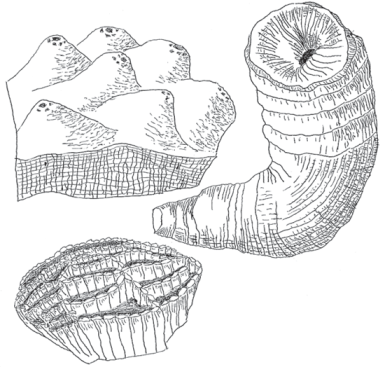

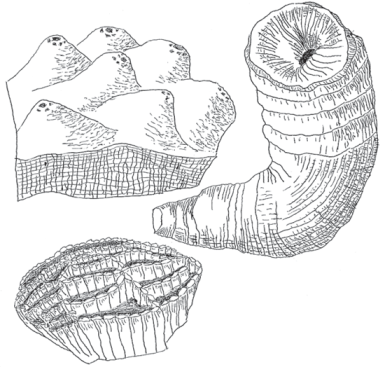

In the oceans, the Frasnian crisis destroyed the largest reefs in Earth history—the massive Paleozoic-style skeletal reefs of stromatoporoid sponges, tabuate corals, and rugose corals (fig. 7.2). The stromatoporoids just barely survived the Frasnian extinction, only to be exterminated by the Famennian crisis. The tabulate corals never recovered their previous diversity, but the rugosans did begin to recover and diversify in the Early Carboniferous, only to be decimated by the Serpukhovian crisis (McGhee et al. 2012). One hundred thirty million years were to pass before the corals once again became the major skeletal-building element in reefs—in the Middle Triassic, with the evolution of the scleractinian corals (Flügel and Stanley 1984; Fois and Gaetani 1984). If the Late Paleozoic Ice Age had never happened, would Paleozoic-style massive skeletal reefs have survived to the present? Would the scleractinian corals and our modern-style reefs have never evolved?

FIGURE 7.2 The skeletal-building elements of the massive Paleozoic-style reefs were chiefly stromatoporoid sponges like Stromatopora polyostiolata (top left), tabulate corals like Halysites catenularia (bottom left), and rugosan horn-corals like Caninia torquia (right).

Source: Stromatopora, Halysites, and Caninia modified and redrawn from Tasch (1973); Hoskins, Inners, and Harper (1983); and Moore, Lalicker, and Fischer (1952), respectively.

The Devonian is also known as the “Age of Armored Fishes,” the great placoderms (table 7.1) (Young 2010). As discussed in chapter 2, some of the great armored fishes were as big as modern-day killer whales, but unlike killer whales, the armored fishes had no teeth. Instead, they had sharp bone blades in their mouths that functioned in a way similar to the sharp bone beaks of modern-day snapping turtles. And even though they possessed massive armor plates of bone around their heads, internally these peculiar fishes had skeletons made of cartilage, rather than bone, like modern-day sharks. Imagine a huge shark with a head like a snapping turtle and you have a fish similar to the great placoderm predators (see fig. 2.1).

TABLE 7.1 Detailed phylogeny of placoderm and sarcopterygian vertebrates showing the effect of the twin Late Devonian extinctions (modified from tables 6.5 and 6.8).

| VERTEBRATA (animals with vertebrae) |

| – Gnathostomata (jawed vertebrates) |

| – – PLACODERMI (armored fishes) †Famennian |

| – – – Acanthothoraci †Frasnian |

| – – – unnamed clade †Famennian |

| – – – – unnamed clade †Famennian |

| – – – – – Rhenanida †Frasnian |

| – – – – – Antiarchi †Famennian |

| – – – – unnamed clade †Famennian |

| – – – – – Arthrodira †Famennian |

| – – – – – unnamed clade †Famennian |

| – – – – – – Petalichthyida †Frasnian |

| – – – – – – Ptychtodontida †Famennian |

| – – CHONDRICHTHYES (sharks, rays, and kin) |

| – – Acanthodii (spine fin fishes) |

| – – Osteichthyes (bony fishes) |

| – – – ACTINOPTERYGII (ray fin fishes) |

| – – – SARCOPTERYGII (lobe fin fishes + descendants) |

| – – – – CROSSOPTERYGII |

| – – – – – Porolepiformes †Famennian |

| – – – – – unnamed clade |

| – – – – – – Onychodontida †Famennian |

| – – – – – – Actinista (living coelacanths) |

| – – – – DIPNOI (lung fishes) |

| – – – – TETRAPODOMORPHA (tetrapod-like fishes + descendants) |

| – – – – – Rhizodontia |

| – – – – – Osteolepidiformes |

| – – – – – – Osteolepididae †Famennian |

| – – – – – – Megalichthyidae |

| – – – – – – Eotetrapodiformes |

| – – – – – – – Tristichopteridae †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – unnamed clade |

| – – – – – – – – Elpistostegalia †Frasnian |

| – – – – – – – – TETRAPODA (limbed vertebrates) |

| – – – – – – – – – Family Elginerpetontidae †Frasnian |

| – – – – – – – – – – Elginerpeton pancheni †Frasnian |

| – – – – – – – – – – Obruchevichthys gracilis †Frasnian |

| – – – – – – – – – Family incertae sedis †Frasnian |

| – – – – – – – – – – Sinostega pani †Frasnian |

| – – – – – – – – – unnamed clade |

| – – – – – – – – – – Family incertae sedis †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – Densignathus rowei †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – – – – unnamed clade |

| – – – – – – – – – – – Family incertae sedis †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – Ventastega curonica †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – unnamed clade †Frasnian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – Family incertae sedis †Frasnian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – Metaxygnathus denticulus †Frasnian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – Family incertae sedis †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – Jakubsonia livnensis †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – unnamed clade |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – Family Acanthostegidae †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – Acanthostega gunnari †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – unnamed clade |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – Family incertae sedis †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Ymeria denticulata †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – unnamed clade |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Family Ichthyostegidae †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Ichthyostega stensioei †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Ichthyostega watsoni †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Ichthyostega eigili †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – unnamed clade |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Family incertae sedis †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Hynerpeton bassetti †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – unnamed clade |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Family Tulerpetontidae †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Tulerpeton curtum †Famennian |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – unnamed clade |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Family Colosteidae |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – unnamed clade |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Family Crassigyrinidae |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – unnamed clade |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Family Whatcheeriidae |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – unnamed clade |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Family Baphetidae |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – unnamed clade |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Neotetrapoda |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – BATRACHOMORPHA (ancestors of amphibians) |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Lepospondyli |

| – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – REPTILIOMORPHA (ancestors of amniote tetrapods) |

Source: Phylogenetic data modified from Lecointre and Le Guyader (2006), Ahlberg et al. (2008), Clack et al. (2012), and Benton (2015).

Note: Lineages that went extinct in either the Frasnian or Famennian are marked with a dagger (†); the age of their extinction is in bold; major clades are in capitals.

The Frasnian extinctions eliminated half of the world’s diversity of armored fishes (table 7.1); the Famennian extinctions eliminated them all (table 7.1). Our modern ecologically and numerically dominant fishes, the sharks (the chondrichthyans, table 7.1) and ray-fin fishes (the actinopterygians, table 7.1), diversified only in the Early Carboniferous, filling the ecological void left by the vanished armored fishes (Sallan and Coates 2010; McGhee 2013). If the Late Paleozoic Ice Age had never happened, would our rivers, lakes, and seas still be populated by giant dinichthyids and titanichthyids—the “terrible fishes” and “titanic fishes”—that were seven meters (23 feet) long, with massive bony head armor and jaws like a snapping turtle? Would sharks and ray-fin fishes never have diversified, but only continued to exist in the shadow of the great armored fishes if the Late Paleozoic Ice Age had never happened?

The Late Devonian extinctions were particularly severe in the clade of the sarcopterygian vertebrates (table 7.1), where they acted as evolutionary bottlenecks. As discussed in chapter 2, an evolutionary or genetic bottleneck is produced when the population sizes of a given species shrink almost to the critical minimum level from which a species cannot recover. One of the consequences of a species’ surviving an evolutionary bottleneck is the sharp reduction of morphological or genetic diversity in the population of survivors. Another is a reduction in the geographic range of a species: species that may once have had large populations spread across a continent may be found in only a few regional patches with small numbers of individuals after an evolutionary bottleneck. Finally, as implied in the descriptive name “bottleneck,” only a few lineages manage to survive past that evolutionary constriction. All of these classic bottleneck phenomena are seen in the lineage of the sarcopterygians in the twin Late Devonian extinctions; hence I call these two evolutionary events the End-Frasnian Bottleneck and the End-Famennian Bottleneck (McGhee 2013).

The sarcopterygian lobe-fin fishes are not familiar to us today, but they greatly outnumbered our modern, familiar ray-fin fishes (the actinopterygians, table 7.1) back in the Devonian. The sarcopterygian clade was hit hard by the Late Devonian extinctions, and today they are represented by only one genus of coelacanth fish, three groups of lung fish, and, of course, ourselves—the modern living tetrapods.

The End-Famennian Bottleneck eliminated two-thirds of the lineages of the crossopterygian lobe-fin fishes (table 7.1). For many years, paleontologists thought that the crossopterygians were extinct—that is, that they had encountered an evolutionary dead end rather than a bottleneck. Then, in 1938, off the coast of South Africa, fishermen unexpectedly captured a very odd-looking fish. Unlike a ray-fin fish, whose fins appears to attach directly to its body, this fish had peculiar stumpy lobes—lobes that contained bones—protruding from its body, and its fins were attached to these lobes. To their astonishment, paleontologists recognized the fish as a living coelacanth crossopterygian and gave it the name Latimeria chalumnae. Since that time, other individuals of Latimeria chalumnae have been sighted and photographed in the waters off South Africa and Madagascar, have appeared in National Geographic magazine and television programs, and so on. The crossopterygians had survived the End-Famennian Bottleneck after all, and are still alive today.

Only three families of lungfishes, the dipnoian sarcopterygians (table 7.1), survive today—the Neoceratodontidae in Australia, the Lepidosirenidae in South America, and the Protopteridae in Africa. These widely scattered lungfish groups are rare, the only survivors of a group of fishes that were very numerous in the Devonian. What if lobe-fin crossopterygian and dipnoian fishes were common today, as they were in the Devonian, and ray-fin fishes were rare? The idea that we evolved from fish might not seem so strange to people if every time they bought a fish at the supermarket, it had four stumpy limblike fins, complete with internal bones, as in a crossopterygian fish. What if it were not at all unusual to go down to a river and see several different types of fishes crawling about on the banks, breathing air? If, like common pet turtles in aquaria, modern-day children kept air-breathing fish as pets at home, would their parents still be skeptical than land vertebrates are the descendants of fish?

Next we encounter the tetrapodomorph fishes—the ancestors of the living tetrapods (table 7.1). No fewer than three groups of lobe-fin, tetrapodomorph fishes were independently evolving tetrapod-like morphologies in the Devonian—the tristichopterids like Eusthenopteron (fig. 7.3), the elpistostegalians like Tiktaalik (fig. 7.3), and, of the course, the tetrapods themselves (table 7.1) (Ahlberg and Johanson 1998; Coates et al. 2008; McGhee 2013). The End-Frasnian Bottleneck eliminated the elpistostegalians, and the End-Famennian Bottleneck eliminated the tristichopterids (table 7.1). The extinction of the elpistostegalian, tristichopterid, and osteolepidid tetrapodomorphs created a large phylogenetic gap between the advanced tetrapods and the basal rhizodont and megalichthyid tetrapodomorphs (table 7.1). The rhizodonts would not survive the Carboniferous, and the megalichthyids would not survive the Permian. By the end of the Paleozoic, only the tetrapod clade remained of the once diverse tetrapodomoph lineages. As a result of the Late Devonian extinctions and bottlenecks, a large phylogenetic gap exists today between living limbed vertebrates (the tetrapods; table 7.1) and living finned vertebrates (the ray-fin fishes, the actinopterygians; table 7.1). All of our intermediate cousins are gone, which is why a modern-day lizard seems to us to be such a radically different animal from a trout.

FIGURE 7.3 From lobed fins to limbs (from top to bottom): comparison of the bones in the fin of the tristichopterid fish Eustenopteron foordi, in the fin of the elpistostegalian tetrapodomorph Tiktaalik roseae, in the forelimb of the aquatic tetrapod Acanthostega gunnari, in the forelimb of the cynodont synapsid Thrinaxodon liorhinus, in the forelimb of the mammalian synapsid mountain lion Felis concolor, and in the arm of the human Homo sapiens.

Source: Illustration by Kalliopi Monoyios © 2013. Reprinted with permission.

If these two bottlenecks in vertebrate evolution had not occurred, might further parallel evolution in both the elpistostegalian and tristichopterid lineages have produced animals with four limbs? That is, could the condition of possessing four limbs have evolved independently in three separate vertebrate lineages, instead of just one? This is not an outlandish idea: it is a fact that three other groups of vertebrates have convergently, independently, evolved wings from their forelimbs—the pterosaurs, the birds, and the bats. The pterosaurs are ornithodiran reptiles, and they evolved wings from their forelimbs in the Triassic. The birds are also reptiles, but they belong to a much more derived lineage of reptiles—the dinosaurs. They independently evolved wings from their forelimbs in the Jurassic. The bats are very different from the pterosaurs and birds as they are synapsids, not reptiles. They are also are very highly derived synapsids—they are mammals—and yet they also independently evolved wings from their forelimbs in the Paleocene, at the beginning of the Cenozoic (Benton 2005). If three separate groups of vertebrates could independently, convergently, accomplish the seemingly highly unlikely feat of evolving wings from modified forelimbs, it is equally likely that three separate groups of advanced lobe-fin fishes could have independently, convergently, evolved four limbs from their four ventral lobe fins. Today the skies of the Earth are the territory of birds and bats—two very different kinds of winged animals that have no common winged ancestor. What if the land areas of the Earth were also home to two, or even three, different kinds of limbed vertebrates that also had no common limbed ancestor but had independently evolved their four limbs? We will never know, as the Late Devonian bottlenecks eliminated that evolutionary possibility forever.3

The first of the tetrapods—the true limbed vertebrates (table 7.1)—were aquatic animals, not land dwellers. Their limbs were short, and the manus and pes (hand and foot) morphologies on the limb, used as swimming and crawling paddles, were very different from those of modern tetrapods (fig. 7.3). Only with subsequent evolution would the paddlelike limbs of the early aquatic tetrapods be modified to limbs that would bear the weight of the animal as it walked on dry land. The Devonian aquatic tetrapods like Acanthostega (fig. 7.3) were the classic “fish with feet” that are featured today on cars with Darwin bumper stickers.

The End-Frasnian Bottleneck hit the tetrapods hard (table 7.1). Before the bottleneck, these early aquatic tetrapods had a worldwide distribution—from Scotland (Elginerpeton pancheni) and Latvia (Obruchevichthys gracilis) in Europe in the west to China (Sinostega pani) and Australia (Metaxygnathus denticulus) in the east. After the bottleneck, surviving early Famennian tetrapods are found only in Europe. Before the bottleneck, tetrapods had a diversity of body sizes, from large individuals up to 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) long to small individuals about a 0.5 meters (1.6 feet) long. After the bottleneck, surviving Famennian tetrapods are about all the same size—about a meter (3.3 feet) long. The End-Frasnian Bottleneck triggered a sharp reduction in morphological variance and geographic range in surviving tetrapod faunas, reductions that are classic evolutionary bottleneck phenomena. What diverse Famennian morphological novelties and body sizes might our cousins in the other Frasnian tetrapod lineages have produced if they had not been eliminated by the End-Frasnian Bottleneck? How would the future course of tetrapod evolution have changed if these lineages had survived?4

Following the Famennian Gap cold period (table 1.7), the tetrapods began to recover their species diversity and began to lose many of their fishlike traits as they became more adapted to life on dry land. Then they encountered the End-Famennian Bottleneck, and it triggered an even more severe diversity contraction than had the End-Frasnian Bottleneck (table 1.7). Not only were almost all of the new Famennian clades eliminated, two lineages of Frasnian survivors (the lineages of Densignathus rowei and Ventastega curonica) were also driven to extinction. Only three groups are thought to have survived the bottleneck—the colosteids, the crassigyrinids, and the whatcheeriids (table 1.7). Only the whatcheeriids are known from fossils in the Famennian (Daeschler et al. 2009; McGhee 2013), and the presumed survival of the colosteids and crassigyrinids is based solely on phylogenetic analyses that indicate that they are more primitive than the whatcheeriids and thus evolved before the whatcheeriids.5

As discussed in chapter 2, following the Famennian glaciations and the Tournaisian Gap cold period (table 1.7), the tetrapods began once again to recover. The whatcheeriids (see fig. 2.2) in particular blossomed in diversity and achieved a worldwide distribution, with new species being found in North America, Europe, and Australia. By the Visean Age, the tetrapod invasion of land was in full progress, and the two major clades of the batrachomorphs (ancestors of our modern amphibians) and the reptiliomorphs (ancestors of the amniotes—the living reptiles, dinosaurs, and mammals) had evolved (tables 2.4 and 7.1).

At the very least, the End-Frasnian Bottleneck set back and delayed the successful invasion of land by tetrapods by some six million years (the duration of the Famennian Gap, table 1.7), and the End-Famennian Bottleneck likewise generated another delay of some ten million years (the duration of the Tournaisian Gap). At the worst, the bottlenecks changed the direction of tetrapod evolution forever—we will never know how the exterminated lineages would have evolved or what ecological diversifications and evolutionary innovations they would have produced. In our impoverished world, only one lineage of four-limbed vertebrates exists—a sad legacy of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age.

On the other hand, as discussed at the beginning of this section, the hyperoxic atmosphere produced by the Late Paleozoic Ice Age was a major boost to that surviving tetrapod lineage in its final and successful invasion of land. The other major clade of terrestrial invaders, the arthropods, likewise received that energetic boost—a boost that sent them into the skies. In a world where the hyperoxic atmosphere of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age had never existed, perhaps both of those evolutionary events might still have happened—but they might also have taken much longer than the rapid burst of evolutionary events that occurred in the Serpukhovian–Bashkirian interval of Carboniferous time.

WHAT IF THE SIBERIAN MANTLE PLUME HAD MISSED THE TUNGUSKA BASIN?

The continental glaciations of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age eventually would have ended even if the global warming produced by the Emeishan LIP eruption and then the extreme global heating produced by the Siberian LIP eruption had never happened. After its long 115-million-year trek, the supercontinental mass of Gondwana was finally moving off the South Pole in the latest Permian, as discussed in chapter 1 (fig. 1.3). By the Middle Triassic, about 240 million years ago, the South Pole was open ocean.6 The giant landmass of Gondwana began to break up in the Middle Jurassic: the plate fragment holding South America and Africa began to move north, and the plate fragment holding India, Antarctica, and Australia began to move south, back toward the South Pole. By the Early Cretaceous, the continental region of Antarctica was once again located over the South Pole, and then first India and later Australia began to split away from it. By the Eocene Epoch of the Cenozoic Era, Antarctica was a totally separate continent—a small fraction of the original giant continent Gondwana—sitting directly on the South Pole, and the initial phases of the continental glaciation that would produce the Cenozoic Ice Age had begun.7

In itself, eruption of a mantle plume the size of the Siberian one would have affected the climate of the entire planet, but not to the extent that it did when combined with the vaporization and explosive venting of gases from the huge volume of Tunguska Basin organic-rich and evaporite strata that the Siberian mantle plume burned through on its way to the surface of the Earth. The Siberian mantle plume alone erupted enough lava to cover five million square kilometers (1.93 million square miles) of land; as discussed in chapter 6, that is enough lava to cover 62 percent of the area of the United States between the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. The Siberian flood-basalt eruption is estimated to have been 8.3 to 20 times larger than the Emeishan LIP, producing some 45 to 108 trillion tonnes (50 to 119 trillion tons) of sulfur-dioxide pollutant and its byproduct, sulfuric acid. The acidification of the world’s oceans and acid rain poisoning of the world’s land areas would have proceed just as they did at the end of the Permian in the absence of any further gaseous input from the Tunguska Basin strata—but it can be argued that the environmental impacts would have been measured on a smaller scale. This is because the massive additional injection of sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere from the Tunguska Basin anhydrite deposits—strata rich in calcium sulfate—would not have occurred if the Siberian mantle plume had missed the Tunguska Basin.

Beyond the effects of sulfur dioxide, the environmental consequences of the Siberian LIP eruption would have been radically different if the hot plume had missed the Tunguska Basin. At the end of the Permian, between 100 and 160 trillion tonnes (110 to 176 trillion tons) of carbon dioxide and between 14 and 42 trillion tonnes (16 to 46 trillion tons) of methane were injected into the Earth’s atmosphere from the organic-rich strata in the Tunguska Basin (Svensen et al. 2009; Payne et al. 2010), as discussed in chapter 6. What if this had never happened? If the Earth’s atmosphere had never become vastly enriched and polluted with those two greenhouse gases, the horrific Hot Earth of the latest Permian and Early Triassic would never have occurred. The global depletion of oxygen from the Earth’s atmosphere that occurred at the end of the Permian—caused by the oxidation of those trillions of tonnes of methane—would never have happened. The additional acidification of the world’s oceans by carbonic acid would never have occurred; ocean acidification would have been the product of the mantle plume’s own sulfur dioxide without any extra boost from the Tunguska Basin carbon deposits. Coal fly ash from the burning Tunguska Basin coal strata would never have been explosively injected into the atmosphere, oceanic euxinia would not have occurred, and unknown trillions of marine organisms would never have suffocated from the oxygen-depleting effects of eutrophication. Thus three of the end-Permian kill mechanisms that we considered in chapter 6—heat death, carbon-dioxide poisoning, and suffocation—would either not have occurred at all or would have been vastly reduced in their lethality.

Finally, we have the evaporite strata of the Tunguska Basin. At the end of the Permian, between five and 15 trillion tonnes (six to 17 trillion tons) of methyl chloride and between 87 and 255 billion tonnes (96 to 281 billion tons) of methyl bromide were injected into the Earth’s atmosphere from the burning of the Tunguska Basin evaporite deposits (Svensen et al. 2009). If the Siberian mantle plume had missed the Tunguska Basin, those gases never would have been injected into the atmosphere, the ozone layer of the atmosphere never would have been destroyed, and the vast increase in the radiation flux of ultraviolet at the Earth’s surface never would have occurred. Yet another of the end-Permian kill mechanisms—radiation poisoning—would either not have occurred at all or would have been vastly reduced in its lethality.

In chapter 6 we also considered the alternative mantle-plume-chemistry model of Sobolev and colleagues (Sobolev et al. 2011), who argued that the Siberian LIP itself could have produced as much as 175 trillion tonnes (193 trillion tons) of carbon dioxide and as much as 18 trillion tonnes (20 trillion tons) of hydrochloric acid if the melting and recycling of oceanic crustal rock located beneath Siberia had produced a magma that was more gaseous and carbon rich than typical basaltic-type lavas of other LIP eruptions like those of Laki, Iceland. Thus, in the case of each kill mechanism discussed above, I have included the possibility that even if the Siberian mantle plume had missed the Tunguska Basin, the kill mechanisms of heat death, carbon-dioxide poisoning, suffocation, and radiation poisoning still might have occurred but would have been vastly reduced in their lethality. Even if the magma-chemistry model of Sobolov and colleagues is eventually shown to be correct, it is a known fact that the Siberian mantle plume did indeed burn through the organic-rich and evaporitic strata of the Tunguska Basin. Thus, whatever the lethality of the kill mechanisms produced by the Sobolev and colleagues model for the Siberian mantle plume alone, all of the intensification of those kill mechanisms produced by the vast tonnages of carbon dioxide, methane, methyl chloride, and methyl bromide that were injected into the Earth’s atmosphere at the end of the Permian would have to be subtracted if the mantle plume had missed the Tunguska Basin.

Would the end-Permian mass extinction have happened at all if the kill mechanisms of heat death, carbon-dioxide poisoning, suffocation, and radiation poisoning had never occurred, or occurred with much reduced intensities? If the Siberian mantle plume had missed the Tunguska Basin, would the only major kill mechanism triggered have been acidification resulting from the plume’s venting of sulfur dioxide? The Siberian volcanic eruptions were the largest continental LIP in Earth history (Reichow et al. 2009), but would sulfur-dioxide-induced acidification of the world’s oceans and land areas have been lethal enough to cause the largest loss of biodiversity and the severest ecological catastrophe in Earth history, the end-Permian mass extinction (table 1.3)?

If an extinction event of much reduced severity had occurred at the end of the Permian—in essence, if there had been no end-Permian mass extinction—would the Paleozoic world have never come to an end (table 6.6)? Jack Sepkoski would have argued that the Paleozoic marine world would still have ended, even in the absence of the end-Permian mass extinction—it just would have taken longer and not been as abrupt in an alternative world in which the Siberian mantle plume missed the Tunguska Basin. Sepkoski’s analyses of the interactive evolutionary dynamics (Sepkoski 1981, 1984, 1990; Sepkoski and Miller 1985) of his Paleozoic evolutionary fauna and modern evolutionary fauna supported the conclusion that the modern evolutionary fauna would have actively, competitively, ecologically replaced the Paleozoic evolutionary fauna with time, just as his Paleozoic evolutionary fauna competitively replaced the Cambrian evolutionary fauna (figs. 6.10, 6.11). Sepkoski’s analyses showed that every major crisis in the Paleozoic had differentially eliminated Paleozoic marine world fauna and favored the modern evolutionary fauna—in essence, that the Paleozoic marine world was doomed even in the absence of the catastrophic effects of the end-Permian mass extinction. The winnowing effect of the Frasnian, Famennian, Serpukhovian, and Captanian extinctions on the Paleozoic marine world fauna would still have occurred in a world where there had been no end-Permian mass extinction, and Sepkoski would have argued that each future biodiversity crisis in the marine realm would have continued to eliminate Paleozoic marine world fauna in favor of the modern evolutionary fauna in an inexorable process of natural selection.

However, the story might have been very different for the Paleozoic terrestrial world fauna in a world in which the end-Permian mass extinction had never happened. In such an alternative world, in the absence of the catastrophic effects of the Siberian LIP, would the diverse land-dwelling vertebrate faunas of the Paleozoic world have been replaced almost entirely by reptiles (tables 6.7 and 6.8)? And if the synapsids had not been weakened by the end-Permian mass extinction, might they not have been replaced by dinosaurs in the Late Triassic (table 6.9)—might the synapsids have continued to be the numerically and ecologically dominant land vertebrates? Might the synapsids have evolved endothermic mammals before the dinosaurs, and might the dominant mammals have kept the dinosaurs in check for the next 150 million years—rather than the dinosaurs keeping the mammals in check, as happened in our world in the Mesozoic?

The dinosaurs evolved a robust ecosystem structure that persisted for 150 million years before being destroyed in the environmental catastrophe triggered by the Chicxulub asteroid strike at the end of the Cretaceous. After the collapse of the dinosaur ecosystem, the same ecosystem structure was convergently evolved by the mammals in the Cenozoic (table 7.2). It is important to note that the structure of the 19 ecological roles, or niches, listed in table 7.2 first appeared in the evolution of the dinosaurian-dominated ecosystems of the Mesozoic world, not in the mammalian-dominated ecosystem structure of the Cenozoic world. Mesozoic dinosaurs did not independently evolve the ecological roles of lions, wild cats, wolves, wolverines, anteaters, elephants, deer, bison, rhinoceroses, glyptodonts, goats, and ground sloths—it is the Cenozoic mammal fauna that has convergently refilled the ecological niches of allosaurs, coelophysises, velociraptors, troodonts, alvarezsaurids, sauropods, hypsilophodonts, hadrosaurs, triceratopses, ankylosaurs, pachycephalosaurs, and therizinosaurs! Some of these two groups of animals resemble each other morphologically (triceratopses and rhinoceroses, ankylosaurs and glyptodonts, therizinosaurs and ground sloths), whereas the others appear radically different—the mammalian predators are all quadrupeds, whereas the dinosaurian predators walked on their hind legs only. Yet they all were ecological analogs of each other, making their living in the roughly same way. The goats, for example, have a ruminant stomach system to process plant material, whereas the pachycephalosaurs had a gizzard-like gastric mill to accomplish the same purpose. The similarity in the herbivorous ecological roles of many of the ornithopod dinosaurs, such as the hypsilophodonts and hadrosaurs, to ungulate mammals prompted paleobiologists Matthew Carrano, Christine Janis, and Jack Sepkoski to conclude: “Although late Mesozoic and late Cenozoic terrestrial ecosystems were profoundly different in terms of both animal and plant taxa, there may be universal constraints on the ecological roles played by large herbivores, resulting in convergence in morphology (and, by implication, behavioral ecology) between groups as taxonomically distinct as dinosaurs and mammals” (Carrano et al. 1999, 256). Thus Carrano and colleagues suggest that Mesozoic hadrosaurs and Cenozoic ungulates may provide an example of both ecological and behavioral convergent evolution.8

TABLE 7.2 Convergent evolution of ecological-analog compositions of Mesozoic dinosaurian-dominated ecosystems and Cenozoic mammalian-dominated ecosystems.

| Convergent Ecological Analog |

Mesozoic Ecosystem |

Cenozoic Ecosystem |

| 1. Large ambush predator |

Allosaur (Dinosauria: Allosauridae; Allosaurus fragilis †Jurassic) |

Lion (Mammalia: Felidae; Panthera leo) |

| 2. Small ambush predator |

Coelophysis (Dinosauria: Coelophysidae; Coelophysis rhodesiensis †Triassic) |

Wild cat (Mammalia: Felidae; Felis sylvestris) |

| 3. Pursuit pack predator |

Velociraptor (Dinosauria: Dromaeosauridae; Velociraptor mongoliensis †Cretaceous) |

Wolf (Mammalia: Canidae; Canis lupus) |

| 4. Nocturnal foraging predator |

Troodont (Dinosauria: Troodontidae; Saurornithoides mongoliensis †Cretaceous) |

Wolverine (Mammalia: Mustelidae; Gulo gulo) |

| 5. Ant eater |

“Desert bird” alvarezsaurid (Dinosauria: Alvarezsauridae; Shuvuuia deserti †Cretaceous) |

Anteater (Mammalia: Myrmecophagidae; Myrmecophaga tridactyla) |

| 6. Large, herding, browsing herbivore |

Sauropod (Dinosauria: Titanosauridae; Titanosaurus madagascariensis †Cretaceous) |

Elephant (Mammalia: Elephantidae; Loxodonta africana) |

| 7. Midsize, fast-running, browsing herbivore |

Hypsilophodont (Dinosauria: Hypsilophodontidae; Hypsilophodon foxii †Cretaceous) |

Deer (Mammalia: Cervidae; Cervus elaphus) |

| 8. Large, herding, mixed-feeding herbivore |

Hadrosaur (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae; Parasaurolophus walkeri †Cretaceous) |

Bison (Eutheria: Bovidae; Bison bison) |

| 9. Large, horned, grazing herbivore |

Triceratops (Dinosauria: Ceratopsidae; Triceratops albertensis †Cretaceous) |

Rhinoceros (Mammalia: Rhinocerotidae; Rhinoceros unicornus) |

| 10. Large, armored, grazing herbivore |

Ankylosaur (Dinosauria: Ankylosauridae; Ankylosaurus magniventris †Cretaceous) |

Glyptodont (Mammalia: Glyptodontidae; Doedicurus clavicaudatus †Pleistocene) |

| 11. Midsize ruminant grazer |

Pachycephalosaur (Dinosauria: Pachycephalosauridae; Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis †Cretaceous) |

Goat (Mammalia: Bovidae; Capra hircus) |

| 12. Giant frugivore (fruit eater) |

“Sloth-claw” therizinosaur (Dinosauria: Therizinosauridae; Nothronychus mckinleyi †Cretaceous) |

Giant ground sloth (Mammalia: Megatheriidae; Nothrotheriops shastensis †Pleistocene) |

| 13. Fluvial piscivore (fish eater) |

Spinosaur (Dinosauria: Spinosauridae; Spinosaurus maroccanus †Cretaceous) |

Gavialid crocodile (Archosauria: Crocodilidae; Gavialis gangeticus) |

| 14. Shallow-marine piscivore |

Plesiosaur (Diapsida: Sauropterygia: Cryptocleididae; Cryptocleidus oxoniensis †Jurassic) |

Sea lion (Mammalia: Otariidae; Zalophus californianus) |

| 15. Small open-ocean carnivore |

Ichthyosaur (Diapsida: Ichthyosauria: Ichthyosauridae; Ichthyosaurus platyodon †Jurassic) |

Porpoise (Mammalia: Phocaenidae; Phocaena phocaena) |

| 16. Large open-ocean carnivore |

Pliosaur (Diapsida: Sauropterygia: Rhomaleosauridae; Rhomaleosaurus megacephalus †Jurassic) |

Killer whale (Mammalia: Delphinidae; Orcinus orca) |

| 17. Flying insectivore (insect eater) |

“Frog-jaw” pterosaur (Ornithodira: Pterosauria: Aneurognathidae; Batrachognathus volans †Jurassic) |

Bat (Mammalia: Vespertilionidae; Myotis myotis) |

| 18. Flying frugivore (fruit eater) |

“Bakony dragon” pterosaur (Ornithodira: Pterosauria: Azhdarchidae; Bakonydraco galaczi †Cretaceous) |

Fruit bat (Mammalia: Pteropodidae; Rousettus aegyptiacus) |

| 19. Flying piscivore |

Pteranodon (Ornithodira: Pterosauria: Pteranodontidae; Pteranodon longiceps †Cretaceous) |

Pelican (Aves: Pelecanidae; Pelicanus occidentalis) |

Source: Modified from McGhee (2011).

Note: The age of extinct species is marked with a dagger and a geologic date (e.g., †Jurassic).

Not all dinosaurian ecological roles are filled by Cenozoic mammals, and not all mammalian roles were filled by dinosaurs. Although the otter hunts fish in rivers, the gavialid crocodile is a much closer modern ecological analog than the otter to the toothy spinosaur (table 7.2). The dinosaurs were exclusively terrestrial animals, yet if we examine marine and oceanic habitats, we find that other Mesozoic animals independently evolved ecological roles that are now played by Cenozoic mammals: the plesiosaur, ichthyosaur, and pliosaur ecological niches have been convergently refilled by Cenozoic sea lions, porpoises, and killer whales. In the air, the insect-eating pterosaur and fruit-eating pterosaur niches have been independently re-evolved by the insect-eating bats and the fruit-eating bats. And the modern pelican, itself an avian dinosaur, convergently refilled the niche of the Mesozoic pteranodon and even resembles a small pteranodon in appearance. Mammals also have convergently evolved flying fish-eaters, such as the greater bulldog bat, Noctilio leporinus, although it looks nothing like a pteranodon (excepting the wings).

In these 19 ecological roles (table 7.2), the Cenozoic ecosystem play is scripted in the same way as the Mesozoic ecosystem play. The roles of the ecological play have not changed, although the cast of actors changed dramatically following the end-Cretaceous mass extinction. Would this same ecosystem structure have evolved if the end-Permian mass extinction had never happened, if the synapsids have evolved endothermic mammals before the dinosaurs, and if the dinosaur-dominated ecosystem structure of our Mesozoic world had never evolved? That is, in an alternative world in which the end-Permian mass extinction had never happened, would the mammals have evolved the same ecosystem structure (table 7.2) back in the Late Triassic? Would the dinosaurs have existed only as minor elements in that ecosystem structure, coexisting with the mammals but being held in check by the mammalian ecological dominants—the reverse of what happened in our world in the Mesozoic?

If the mammals had “got there first,” so to speak, and established a mammalian-dominated ecosystem structure that persisted throughout the Mesozoic, what would have happened when the Chicxulub asteroid impacted the Earth at the end of the Cretaceous? That cosmic event would still have happened, whether there had ever been an end-Permian mass extinction or not, as that event had an extraterrestrial cause. In our world, that impact-generated global environmental catastrophe triggered the collapse of the dinosaurian ecosystem and the extinction of all of the nonavian dinosaurs. In an alternative world in which the end-Permian mass extinction had never happened, would the Chicxulub asteroid impact have destroyed the mammalian ecosystem instead, and would the dinosaurs have then convergently refilled the ecological niches vacated by the extinct mammals? Would that alternative world have had a Mesozoic fauna dominated by mammals, and a Cenozoic fauna dominated by dinosaurs?

The answer to that hypothetical question is … probably not. One of the traits that enabled the mammals to differentially survive the Chicxulub asteroid strike was their ability to burrow underground and hibernate. That trait is an ancient synapsid trait, one that predates the evolution of the mammals—and one that also enabled the synapsids to differentially survive the end-Permian mass extinction, as discussed in chapter 6. It was no accident that the small-bodied, barrel-chested, burrowing dicynodont synapsid Lystrosaurus survived the catastrophic environmental conditions triggered by the Siberian LIP, and that approximately 90 percent of all land vertebrates alive in the Early Triassic were lystrosaur synapsids (Sahney and Benton 2008). (However, remember from chapter 6 that that synapsid population resurgence was short and not sweet, as the reptilian rhynchosaur and rauisuchian competitors were soon to evolve in the Middle Triassic, and the deadly dinosaurs proliferated in the Late Triassic; table 6.9). It is a curious quirk of evolution that this trait is found in both highly derived, high-metabolic-rate endothermic mammals and ancient, primitive, ectothermic animals like amphibians—animals that are not even amniotes. The phylogenetic distribution of this trait explains some of the great mystery of why almost all of the highly derived, ecologically advanced, high-metabolic-rate dinosaurs were exterminated by the end-Cretaceous mass extinction, whereas very ancient ectothermic animals like frogs and snakes survived: the dinosaurs did not burrow underground and they did not hibernate. The dinosaurs, to our knowledge, never evolved the ecological equivalents of mammalian moles, woodchucks, rabbits, and the like.

Large body size is always a survival liability in times of ecological crisis—large-bodied animals need too much food—and in a hypothetical world in which the mammals were ecologically dominant when the Chicxulub asteroid struck the Earth, all of the large-bodied mammals would no doubt have perished, just as all of the large-bodied dinosaurs did in our world. But—just as actually happened in our world—diverse lineages of mammals that could burrow and hibernate would have survived to rediversify in the postextinction hypothetical world. The small-bodied dinosaurs did not have this capability, and they also perished, along with their large-bodied kin, in the end-Cretaceous mass extinction. Only the avian dinosaurs survived, probably as a result of both small body size and their ability to fly: they could cover large areas in search of food when food was in very short supply in the post-asteroid-impact world. No doubt vast, uncountable numbers of birds starved to death at the end of the Mesozoic terrestrial world, but enough passed through the evolutionary bottleneck to continue the survival of the dinosaurian lineage to this day.

In summary, rather than the end-Permian mass extinction, it was the end-Cretaceous mass extinction that created our modern Cenozoic terrestrial world with its mammal-dominated ecosystems (McGhee et al. 2004). Even in a hypothetical world in which the end-Permian mass extinction never happened, in which the dinosaurian ecosystem never evolved, and in which the mammals became dominant in the Late Triassic, the selective effect of the end-Cretaceous mass extinction would still have resulted in a postapocalyptic terrestrial world that continued to be dominated by mammals, not by dinosaurs.

However, if the end-Permian mass extinction had never happened and the dinosaurian ecosystem had never evolved, then the mammals would have escaped being ecologically dominated and preyed upon by the dinosaurs. Mammals never would have been forced to remain small, mouse- or chipmunk-size creatures during the Jurassic and Cretaceous, digging underground to hide from the terrible small coelurosaurian dinosaur predators, forced to remain nocturnal creatures scurrying furtively for food in the dark of the night in hopes of not being noticed by nocturnally hunting troodont dinosaurs. The 150-million-year-long nightmare of our mammalian ancestors might never have happened.