Introduction

The population of Muslims is growing at a faster rate than any other religions. The Pew Research Centre (2011) reported that Muslims constituted about 25 per cent of the world’s population. The global population of Muslims is predicted to increase from 1.6 billion in 2010 to 2.2 billion in 2030. If this trend continues, the Muslim population is estimated to grow to 2.76 billion, or 29.7 per cent of the world’s population, by 2050. The increase of Muslim population by region from the year 2010 to 2030 is depicted in Table 6.1. These figures indicate that Islam is one of the largest and fastest-growing religions in the world, which in turn will significantly influence the halal industry.

Table 6.1 Muslim population by region, 2010–2030

| 2010 | 2030 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Muslim population (’000) | Estimated % of global Muslim population | Estimated Muslim population (’000) | Estimated % of global Muslim population | |

| World | 1,619,314 | 100% | 2,190,154 | 100.0% |

| Asia-Pacific | 1,005,507 | 62.1% | 1,295,625 | 59.2% |

| Middle East–North Africa | 321,869 | 19.9% | 439,453 | 20.1% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 242,544 | 15.0% | 385,936 | 17.6% |

| Europe | 44,138 | 2.7% | 58,209 | 2.7% |

| Americas | 5,256 | 0.3% | 10,927 | 0.5% |

Source: Pew Research Center, 2011.

Halal industry

The growth in the number of Muslims worldwide has had a huge positive impact on the global halal food market. The trend shows that the sector has grown progressively over the past decade. The value of the global halal market has been projected at US$547 billion a year (Malaysian-German Chamber of Commerce & Industry 2011). Muslim consumers are creating greater demand for halal food and other consumer goods. This is supported by the statistics shown in Table 6.2. For example, in the years 2004 to 2010, the global halal food market size grew by as much as US$64.3 billion, increasing from US$587.2 to US$651.5 billion (Pew Research Centre 2011). Similar trends can be found in the context of Malaysia as the global market demand for halal products and services also positively influences the growth of the domestic halal food industry. The market size of the halal industry in Malaysia has been estimated at RM1.5 billion. In fact, 90 per cent of this market is derived from the food industry. Meanwhile, other growing halal industries, particularly the cosmetic, pharmaceutical, and halal ingredients are the focus of small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Seong 2011).

Table 6.2 Global halal market sizes by region (US$ billion)

| Region | 2004 | 2005 | 2009 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global halal food market size | 587.2 | 596.1 | 634.5 | 651.5 |

| Africa | 136.9 | 139.5 | 150.3 | 153.4 |

| Asian countries | 369.6 | 375.8 | 400.1 | 416.1 |

| GCC countries | 38.4 | 39.5 | 43.8 | 44.7 |

| Indonesia | 72.9 | 73.9 | 77.6 | 78.5 |

| China | 18.5 | 18.9 | 20.8 | 21.2 |

| India | 21.8 | 22.1 | 23.6 | 24.0 |

| Malaysia | 6.6 | 6.9 | 8.2 | 8.4 |

| Europe | 64.3 | 64.4 | 66.6 | 67.0 |

| France | 16.4 | 16.5 | 17.4 | 17.6 |

| Russian Federation | 20.7 | 20.8 | 21.7 | 21.9 |

| United Kingdom | 3.4 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 4.2 |

| Australasia | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| Americas | 15.3 | 15.5 | 16.1 | 16.2 |

| United States | 12.3 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 13.1 |

| Canada | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 1.9 |

Source: Pew Research Centre, 2011.

The rapid expansion of the halal food market provides more opportunities in fulfilling the halal market demands, not only to Malaysia but also to other Muslim countries. New market opportunities, such as halal tourism, have emerged and are becoming increasingly popular among contemporary Muslim travellers. Halal tourism has become a new innovative product in the tourism and hospitality industry. Halal tourism promises a holiday destination for Muslims whereby the travellers will be provided services that are aligned with Shariah principles. The main part of halal tourism is concerned with both halal food and accommodation. Halal food is one of the important factors that influences the choice to visit a particular place and affects tourist attitudes, decisions, and behaviour (Henderson 2008). In fact, scholars have indicated that halal food has the potential to enhance the sustainability of tourism destinations and indeed may represent a competitive advantage (Du Rand, Heath & Alberts 2003), while the accommodation sector, which is most likely to provide food to tourists, is also closely interrelated and affected by halal tourism.

Halal tourism and hotel industry in Malaysia

In becoming a high-income nation, Malaysia, through the Economic Transformation Programmes (ETPs), has highlighted the tourism industry as one of the National Key Economic Areas (NKEA) that need to be successfully transformed. One of the 12 entry point projects (EPPs) under the Tourism NKEA is related to the hotel industry. Under the ETP, the hotel industry is classified in the business tourism theme and specifically the objective is to improve rates, mix, and quality of hotels (Performance Management & Delivery Unit (PEMANDU) 2011). In the national plan, the hotel industry is chosen as one of the critical areas that needs improvement in terms of its financial and non-financial performances. These improvement efforts are expected to result in higher quality hotels in terms of products and services that can be provided to local and international customers.

Malaysia has an impressive brand for an Asian tourist destination. Malaysia was one of the three countries in Asia (after Taiwan and Hong Kong) which achieved a double-digit growth in tourism receipts despite the adverse economic downturn in 2009 (Tourism Malaysia 2009). The slogan of “Malaysia is truly Asia” seems to be a success as the number of tourist arrivals increases year on year.

The tourism industry has been one of the main contributors to the national economy (Tourism Malaysia 2011). In 2016, Malaysia received around 26.76 million tourists compared to 24.58 million tourists in 2010, representing an increase of 2.18 million in arrivals. In 2017, the target is 31.8 million and the figure is expected to rise to 36 million in the year 2020 for tourists visiting Malaysia. Meanwhile, in terms of tourist spending, there has been a significant increase from RM56.5 billion in 2010 to RM82.1 billion in 2016.

In the context of the tourism sector, Muslim tourists are seen to be the highest growing area in international tourist arrivals in Malaysia. In 2012, approximately 5.44 million Muslim tourists were registered to visit Malaysia, up 0.22 million tourists from 2011 (Islamic Tourism Centre of Malaysia 2017). The statistics provided by Malaysia Tourism indicated that Muslim tourists spent about RM5,784 billion in 2010 and made up approximately 23.5 per cent of the total tourist arrivals in Malaysia in the same year (BERNAMA 2011). The top five countries for Muslim tourists were Indonesia, Brunei, Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan (Malaysian Digest 2016). The surge in demand in Islamic tourism has been a blessing for the Malaysian economy. Many Muslim tourists have transferred their holiday vacation destination to Malaysia, particularly after the tragic 9/11 event.

In Malaysia, the development of the hotel sector really commenced in the early 1990s (Aziz 2007). The gradual development of the hotel sector is focused towards luxury hotels as well as the middle and lower class hotels. The hotel sector continues to prosper from year to year. The continued growth in the tourism industry has resulted in the increase in the number of hotels in the country. Newly established hotels have grown due to the increase in tourist arrivals and the increasing demand for accommodation during their trip.

The hospitality industry is the second highest source of income to Malaysia’s GDP (Zailani, Omar, & Kopong 2011; Sahida, Rahman, Awang, & Che Man 2011). However, the tourism and hospitality sectors consist of different products and services, but both simultaneously support the industry as a whole (Aziz, Hassan, Hassan & Othman 2009). The hospitality sector consists of several facilities such as rooms, restaurants, health clubs, night clubs, bars and others, such as meeting rooms. According to Samori and Sabtu (2014), the hotel industry provides services such as accommodation, food and drinks to guests or temporary residents who want to stay at the hotel. Hotels are also defined as an operation that provides accommodation and ancillary services to those who are far from home, travelling for work or leisure. Metelka (1990) defined tourism as an “umbrella” term for a variety of products and services offered to and needed by people while away from “home”. The different products and services meant that accommodation, food services, transportation, attraction of surroundings and others are related to hospitality activities.

The significant increase in Muslim tourists has resulted in a sudden increase in demand for accommodation. In responding to this growth, a number of initiatives have been launched in the country in order to further boost the tourism sector (Malay Mail 2014). One of the initiatives is the adoption of Muslim-friendly accommodation where Shariah principles apply to the hotel operations and services that will appeal to Muslim travellers. Halal tourism has become an innovative and customised product in the tourism industry, which offers destinations and services for Muslims that comply with the Shariah rules (Razalli, Shuib & Yusoff 2013). This is the main focus of the current chapter.

Halal-based hotel operations

Despite the encouragement and efforts by the Malaysian government to develop the hotel sector, there are still inefficiencies in terms of managing the operations of hotels, particularly on the issues of halal-based operations, better known as Shariah-compliant hotel operations, the term used throughout the chapter.

In order to fill this gap, more research is needed on the Shariah-compliant hotels in Malaysia. The current practices of halal-based hotels are merely limited to halal food production. In other words, hoteliers should also ensure that the halal concept goes beyond the aspect of food. It should include other management aspects as well. Such hotels not only serve halal food and beverages, but also the operations throughout the hotel should be managed based on Shariah principles (Sahida et al. 2011). From this perspective, in addition to the hotel kitchens and food preparation processes, the halal concept will also cover the operations, design, and the financial system of the hotel.

The current general perception that Shariah-compliant hotels are only meant for Muslims should also be shifted. There are also non-Muslim consumers who choose Shariah-compliant hotels for their stay. A Shariah-compliant hotel, Al Jawhara Gardens Hotel Business Development UAE, has an annual 10 per cent increase in growth with 80 per cent of their hotel guests being non-Muslim (Muhammad 2015). Tabung Haji Hotel in Malaysia, for instance, is the choice of many non-Muslim guests due to its excellent services such as a large facility, conducive ambiance, and, more importantly, no liquor (Mohamad Azhari 2015). This means that the Shariah-compliant hotel is certainly applicable to both Muslim as well as non-Muslim consumers.

In addition, Muslim tourists, especially from Islamic countries are very sensitive in their hotel selection. Muslim travellers also have their expectations and demand certain amenities in order to uphold their religious belief while travelling for leisure or business. Rajagopal, Ramanan, Visvanathan and Satapathy (2011) indicated how halal certification can be used as a crucial marketing tool in promoting halal brand/products or services. Hotels with halal certification in their kitchen and premises can give an added competitive advantage to the hotels in attracting not only the foreign tourist but also the local visitor (Zailani et al. 2011).

However, the statistics from the department responsible for halal certification in Malaysia, Jabatan Kemajuan Islam Malaysia (JAKIM), has shown that in 2017 there were only 442 hotels in Malaysia that have obtained the halal certification (JAKIM 2017). In 2016, the total number of hotels in Malaysia was recorded as 4,961 (Tourism Malaysia 2017). Therefore, halal certified establishments represent less than 10 per cent of the hotel industry. Hence, in order to attract more tourists, especially Muslim travelers, to Malaysia, the number of Shariah-compliant hotels should be increased.

Thus, further understanding and transformation of the hotel sector with respect to Shariah-compliant hotels are deemed as timely and necessary. The next section will explain the criteria of the Shariah-Compliant Hotel Operations Practices (SCHOP).

Shariah-Compliant Hotel Operations Practices (SCHOP)

The hotel industry in Malaysia is facing numerous new challenges. One of these challenges is internally driven—its service operations. The increasing number of visitors that come to Malaysia due to halal tourism would result in significant operational challenges to hotels. Currently, there limited research that has investigated operational aspects of hotel management, including Shariah-compliant operations.

Shariah-compliant hotels are those hotels that adopt the Shariah principles in their operational practices. The term Shariah refers to the Islamic law derived from the precepts of Islam, particularly from the Qur’an and the hadith of Prophet Muhammad S.A.W. In Islam, halal and haram principles in a Muslim lifestyle are not only for food and drink, but also cover clothing and accessories, marriage, and work-related activities (Al-Qardhawi 1995) (see also Chapters 1 and 2, this volume). In addition to the requirement to serve halal food and drink, hotel operations should also be implemented based on the Shariah principles (Sahida et al. 2011). From this perspective, the halal concept is not confined to the hotel’s kitchen wall, but will also include the operational aspects of the hotel such as human resources, marketing, and the financial system of the hotel as a whole. In other words, the hotel facilities should be comprehensively operated on Shariah principles. However, the concept of Shariah-compliant hotel is still relatively new among hoteliers and generally hotel management still have no clear guidelines how to practise the principles in their work environment. Despite the unavailability of clear guidelines, hotels that introduce the concept of Shariah operations have been gaining an advantage compared to their rivals in the Islamic guest market. This further demonstrates why clear guidelines for Shariah-compliant hotels should be established.

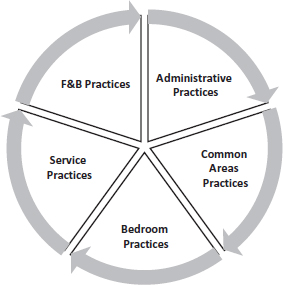

The fact that the Shariah-compliant hotel is still new among hoteliers has resulted in less knowledge and more confusion on the subject matter (Razalli et al. 2013). Even though Muslims are among the largest tourist markets in the world, perceived values of the Shariah-compliant hotel have not been clearly established. Among the general guidelines suggested are those by Rosenberg and Choufany (2009), Henderson (2010), Kana (2011), and Nursanty (2012), but these standards are still not comprehensive enough to cover the scope of the Shariah-compliant hotel as a whole. Current practices of branding hotels in the name of Shariah compliance to accommodate millions of Muslim travellers does not significantly differ from those of normal hotels. In current practice, instead of applying the Shariah principles for the whole operations, the management of the Shariah-compliant hotels only strategise certain parts of their operations to comply with the principles. Hence, this chapter discusses the criteria for Shariah-Compliant Hotel Operations Practices (SCHOP) which have five main dimensions, namely: (1) administrative practices; (2) common areas practices; (3) bedroom practices; (4) service practices; and (5) food and beverage practices.

Criteria for Shariah-Compliant Hotel Operations Practices (SCHOP)

In general, SCHOP consists of five main practices, namely (1) administrative, (2) common areas, (3) bedroom, (4) service, and (5) food and beverage. Figure 6.1 shows the dimensions of SCHOP. These practices are closely related to the structure and operations of most hotels to ensure the practical aspect of the model. All five dimensions have specific attributes that are aligned to Islamic management and Shariah principles. Available frameworks such as the halal certification system by JAKIM, IQS-Islamic Quality Standard for Hotel, Islamic human resource management (Azmi 2009; Khan, Farooq & Hussain 2010), Islamic marketing (Abuznaid 2012; Arham 2010; Hassan, Chachi & Latiff 2008), and Islamic finance (Vejzagic & Smolo 2011) were used as reference points to establish the model. Note that the Qur’an and the hadith are the main sources used for the development of the model. The model is divided into two categories: (1) standard, and (2) advanced. The standard category seeks availability of the practices, while the advanced category measures the degree of implementation of the practices. The following section will discuss the five dimensions in detail.

Figure 6.1 Shariah-Compliant Hotel Operations Practices (SCHOP)

Administrative practices

Administrative practices refer to the managerial practices in relation to the quality assurance in the hotel. These practices include managerial, financial, and human resources practices. There are 15 specific practices in this dimension. Note that one of the critical requirements is for the hotel to have a group of religious advisers who monitor the compliance of hotel operations to Shariah law (Che Ahmat, Ahmad Ridzuan & Mohd Zahari 2012). Without proper planning, monitoring, and controlling in carrying out halal operations, the main objective to become fully Shariah-compliant hotels cannot be easily achieved. Therefore, in regard to be Shariah-compliant, the management should:

- Establish a Shariah advisory committee to continuously evaluate and monitor the degree of compliance of the hotel to the Shariah law.

- Set Islamic quality principles as the main hotel policy.

- Implement and monitor the internal compliance audit.

- Carry out the improvement programme based on the findings of the internal audit assessment.

The second aspect of administrative practice concerns finance. Note that this aspect is still lacking in many of the current Shariah-compliant hotels. In regards to this aspect, the Shariah-compliant hotel must pay the Zakah (for a Muslim owner) or sponsor a social responsibility programme (for a non-Muslim owner) each year. This suggestion, in fact, is in line with Rosenberg and Choufany (2009). Zakah is one of the five pillars of Islam and it is compulsory for every Muslim. A hotel should pay a business Zakah when it has fulfilled the conditions for haul (period of a year) and nisab (achieve the required amount of Zakah). The purpose of Zakah is to purify one’s wealth and to ensure equal allocation of wealth to other human beings (Vejzagic & Smolo 2011).

In addition to Zakah, other financial aspects of Islamic finance to be adopted by hotel operations relate to salary payment, income saving, and investment. In principle, Mu’amalat Islam allows any transactions (Qawaid Fiqh) as long as the transactions do not involve any forbidden transactions such as usury (riba). Interest in finance is clearly mentioned in the Qur’an as a prohibition to all Muslims as follows:

Those who consume interest cannot stand [on the Day of Resurrection] except as one stands who is being beaten by Satan into insanity. That is because they say, “Trade is [just] like interest.” But Allah has permitted trade and has forbidden interest. So whoever has received an admonition from his Lord and desists may have what is past, and his affair rests with Allah. But whoever returns to [dealing in interest or usury]—those are the companions of the Fire; they will abide eternally therein.

(Al-Qur’an, Al-Baqarah: 275)

Mu’amalat Maliyyah in Islam highlights the Shariah principles practised by Muslims since the era of Prophet Muhammad S.A.W and his companions and the progression of hybrid contracts (combination/mixture) that are being used today. Ibn Rusyd and Abu Walid Muhammad b. Ahmad al-Hafid (1981) identified several Shariah contracts that are used in Malaysia’s banking industry today based on the guidelines provided by the Shariah Advisory Council of Bank Negara Malaysia (SAC). The contracts that are widely used in the Islamic banking industry would cover the contracts of Mudarabah (profit sharing), Murabahah (cost increase profit), Wadiah (saving), Musharakah (joint venture), al-Bay’ Bithaman Ajil (BBA) (sales with delayed payment), Wakalah (Agency), Qard al-Hassan (ihsan loan), Ijarah Thumma al-Bay’ (AITAB—hire purchase), Hibah (reward), and several other Shariah-based products. Any business transactions can apply any of these contracts which refer to the guidelines of Shariah in finance by the Bank Islam Malaysia (BIMB Institute of Research and Training 2005), the Shariah Advisory Council of Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM), and the Shariah Advisory Council of Securities Commission (Suruhanjaya Sekuriti 2006). These guidelines can also be used to make financial transactions in accordance to the Syafie mazhab used in Malaysia. In the context of the hotel industry, the financial dimensions of major transactions are shown in Table 6.3.

Table 6.3 Transactions and respective contracts

| Transactions | Type of contract |

|---|---|

| Room reservation | Ijarah (leasing) Bay’ al-urbun (deposit/down payment) |

| Compensation | Ujrah (wages) |

| Savings | Wadiah/mudarabah |

| Retail trade, food & laundry | Al-bay’ (trade) |

| Storage services | Wadiah (saving) |

| Supplies materials | Istijrar (supply contract) |

In the case of the room reservation process, a contract called ijarah (leasing or hiring) and Bay’ al-urban (deposit) are deemed applicable to hoteliers. Ijarah refers to a contract between two parties to utilise a lawful benefit against a consideration (Al-Zuhayli 2002). For hotels, ijarah is the agreement between the hotel owner who allows possession of his/her assets to be used by the customers, on an agreed rental over a specified period. This implies that the customer has complete freedom to utilise the room after the payment has been made. However, the right is terminated after the agreed period is over. For Bay’ al-urbun, it is permissible for the hotel to ask for a deposit to secure the rent and protect the property from any damages during the rental period.

With respect to payment of the worker’s compensation, a contract called ujrah (wages) which is part from ijarah seems to be appropriate for hotels. Ujrah in Islamic finance is simply defined as a fee. This is the financial fee charged in return for using the services or labour. In this case, the services offered by the employees of the hotels.

All businesses want to be profitable. For the Shariah-compliant hotel, the income generated from its business should be managed according to Shariah principles as well. For savings that yield from the business, hotels can opt for the wadiah/mudarabah accounts offered by any of the Islamic banks in the country. Wadiah means a deposit. In other words, al-wadiah is the act of keeping something from an individual or organisation and will guarantee return of it on the demand of the depositor (Sabiq 1983). Wadiah account is an interest-free service offered by the banks and profit will be periodically shared by the bank with the depositor if the bank gains a profit from the money. Meanwhile, mudarabah is a deposit in the form of an investment account. It represents an agreement between the capital provider (hotel) and an entrepreneur (bank) under which the provider provides capital to be managed by the bank and any profit or loss will be shared by both parties.

Other services provided by hotels such as store, laundry, and food and beverages should also comply with the Shariah. For any form of retail trade, food, and laundry services, generally al-bay’ (trade) contract can be applied. For storage services, wadiah contract (savings) can be used. For the consistent supply of raw material transactions such as food from the suppliers, the role of the Istijrar contract may be highlighted. Istijrar is a supply contract in Islam with the terms and conditions agreed between the two parties.

The last practice in the administrative dimension concerns human resources. Human resource management is one of the critical elements that can instil trust among Muslim consumers on the level of Shariah compliance of the hotel. In this regards, a certain percentage of the staff in the hotel should be Muslims. Furthermore, the management should also consider their welfare by providing them apprioprate resources to perform their rights as a Muslim, particularly prayer. Azmi (2009) has elaborated on the application of Islamic human resource in contemporary organisations. Islamic concepts such as tanmiyyah (growth), jammaah (teamwork), taqwa (fearful), ibadah (worship), tazkiyah al-nafs (purifying one’s soul), ta’dib (instilling good manners), khalifah (vicegerent) and al-falah (success), taqlid, istidlal, ma’rifah (degree of faith), tauhid (Allah Oneness and Greatness) are all pertinent to organisations. In addition to improving the knowledge and skills of staff in an organisation, human resource development in Islam also plays the role of improving the spiritual soul of the individual in the organisation. Here are the recommendations in terms of human resource management:

- At least 30 per cent of staff should be Muslims.

- Muslim dress code/attire should be imposed.

- Provision of prayer room for staff.

- Provision of gender-specific changing room.

- Time allocation for Friday prayer (men) and also other daily prayers (men and women).

- Provision of training to staff to be friendly and helpful.

- Assurance of safety and security of the staff on the property.

Common area practices

Common area practices refer to those practices in the public areas in the hotel. This particular category is related to the aurah or the social interaction between men and women in Islam, Islamic entertainment, and the use of halal products. The following attributes represent specific practices in this category:

- Separate facilities for men and women or at least provision of segregated time slots for men and women. These facilities include the spa, gymnasium, recreational/sport, swimming pool, lounge, lift, toilet, and prayer room for guests.

- Halal products should be used in common areas such as soap in the toilet.

- Assurance of guest safety and security while staying in the hotel.

- Provide Islamic entertainment.

- Absence of magic show.

- Permitted music such as nasheed.

- Islamic architecture and design should be used in the property (for example, no picture/sculpture of living beings).

Bedroom practices

Specific attributes and practices are required in guest bedrooms. For a Shariah-compliant hotel, it is suggested the rooms be provided with certain facilities and amenities such as:

- Qiblat direction

- Qur’an

- Prayer mat

- Prayer schedule

- Bidet

- Halal toiletries

- Halal in-room food

- Islamic in-room entertainment.

Note that in terms of decoration, pictures of living beings should not be part of the room design and alcoholic beverages must not be served in the room. In addition, the hotel needs to provide separate smoking and non-smoking rooms due to smoking being deemed as Haram in Malaysia (JAKIM 1995).

Service practices

As a service organisation, human interactions between a service provider and customers are critical to determine the level of customer satisfaction. The front office department is the heart of the hotel operations where this interaction frequently occurs. Hence the role of receptionists at the front office in dealing with the customer is very important. The fourth category, service practices, is related to those practices in the context of Islamic marketing and Islamic finance. Specifically, these practices should include:

- Islamic greeting

- Notification of the banning of alcoholic drinks

- Information on halal restaurants, mosques, and groceries

- Wake-up call for Subuh prayer

- Available services for additional prayer mat and schedule

- Halal products/services such as:

- Wedding packages

- Tours

- Seminars/conferences

- No gambling products/services

- Halal shopping arcade

- Halal detergent for laundry

- Ethical and fair pricing

- Price display/information on room, meal, and other products

- Absence of price discrimination

- Ethical behaviour

- Proper location

- Absence of unnecessary delay for customer services

- Ethical promotional activities

- Absence of sexual appeal

- Absence of manipulation

- Islamic finance transactions.

Food and beverage practices

The final category is with respect to food and beverages practices. All Muslims must consume halal food and beverages. Even though this category is the focus of many Shariah-compliant hotels, it needs to be further strengthened with halal certification. Hence, it is suggested that the hotel obtain halal certification not only for the kitchen, but also for its restaurant for all meals including the meal provided for room service. The halal certification will help guarantee that the food consumed will be halal for Muslims. It will also ensure that the process of preparation, storage, and handling of the food is being managed properly based on the guidelines of the halal system.

In relation to beverages, it is important that the Shariah-compliant hotel forbids any alcoholic drinks to enter to the hotel property. The prohibition of liquor is clearly mentioned in the Qur’an:

O you who have believed, indeed, intoxicants, gambling, [sacrificing on] stone alters [to other than Allah], and divining arrows are but defilement from the work of Satan, so avoid it that you may be successful. Satan only wants to cause between you animosity and hatred through intoxicants and gambling and to avert you from the remembrance of Allah and from prayer. So will you not desist?

(Al-Maidah: 90–91)

This prohibition also applies to business as the prophet Muhammad S.A.W pointed out in a hadith:

Allah’s Messenger cursed ten people in connection with wine: the wine-presser, the one who has it pressed, the one who drinks it, the one who conveys it, the one to whom it is conveyed, the one who serves it, the one who sells it, the one who benefits from the price paid for it, the one who buys it, and the one for whom it is bought.

(Termidzi & Ibu Majah)

Hence, even though liquor is deemed as a major contributor of income to many hotels, it is definitely not permissible for the Shariah-compliant hotel. To Muslims, submission to God’s command is paramount and Muslims seek the benefits not only during their lifetime but also in the hereafter.

Table 6.4 summarises all five dimensions and their attributes discussed above. There are five dimensions and a total of 64 attributes for SCHOP.

Table 6.4 SCHOP dimensions and attributes

| 1.0 | ADMINISTRATION |

| 1.1 | Management |

| 1.1.1 | Shariah Advisory Committee |

| 1.1.2 | Islamic quality principles in hotel policy |

| 1.1.3 | Internal audit |

| 1.1.4 | Improvement programme |

| 1.1.5 | Zakah/social responsibility payment |

| 1.1.6 | Islamic finance in terms of: |

| 1.1.6.1 | Salary payment |

| 1.1.6.2 | Income saving |

| 1.1.6.3 | Investment |

| 1.2 | Staff |

| 1.2.1 | Islamic human resources |

| 1.2.1.1 | 30% ratio of Muslim staff |

| 1.2.1.2 | Muslim dress code/proper attire |

| 1.2.1.3 | Prayer room for staff |

| 1.2.1.4 | Separate changing room (men/women) for staff |

| 1.2.1.5 | Muslim male staff break for Friday prayer |

| 1.2.1.6 | Friendly and helpful staff |

| 1.2.1.7 | Safety and security for staff |

| 2.0 | COMMON AREAS |

| 2.1 | Separate facilities for men and women/time allocation |

| 2.1.1 | Spa |

| 2.1.2 | Gym |

| 2.1.3 | Recreation/sport |

| 2.1.4 | Swimming pool |

| 2.1.5 | Lounge |

| 2.1.6 | Lift |

| 2.1.7 | Toilet |

| 2.2 | Halal soap in toilet |

| 2.3 | Prayer room for staff and guests |

| 2.4 | Attention to guests’ safety/security and property |

| 2.5 | Islamic entertainment |

| 2.5.1 | Absence of magic show |

| 2.5.2 | Permitted music |

| 2.6 | Islamic architecture and interior design |

| 3.0 | BEDROOM |

| 3.1 | Islamic room |

| 3.1.1 | Qiblat direction |

| 3.1.2 | Quran |

| 3.1.3 | Prayer mat |

| 3.1.4 | Prayer schedule |

| 3.1.5 | Absence of pictures of living beings |

| 3.1.6 | Bidet |

| 3.1.7 | Halal toiletries |

| 3.1.8 | Halal in-room food (creamer, coffee, etc.) |

| 3.1.9 | Absence of alcoholic beverages |

| 3.1.10 | Islamic in-room entertainment |

| 3.1.11 | Smoking vs. non-smoking room |

| 4.0 | SERVICES |

| 4.1 | Reception/front desk |

| 4.1.1 | Islamic greeting |

| 4.1.2 | Notification of the ban on alcoholic drink |

| 4.1.3 | Guest safety and security to the room |

| 4.1.4 | Information on Halal restaurants, mosques, and halal groceries |

| 4.1.5 | Wake-up call for Subuh prayer |

| 4.1.6 | Request for additional prayer mat, schedule, etc. |

| 4.2 | Islamic marketing |

| 4.2.1 | Halal products/services |

| 4.2.1.1 | Islamic packages |

| 4.2.1.1.1 | Weddings |

| 4.2.1.1.2 | Tours |

| 4.2.1.1.3 | Seminars/conferences |

| 4.2.1.1.4 | Absence of gambling activities |

| 4.2.1.2 | Halal products |

| 4.2.1.2.1 | Halal shopping arcade |

| 4.2.1.2.2 | Halal detergent for laundry |

| 4.2.2 | Ethical and fair pricing |

| 4.2.2.1 | Price display/information |

| 4.2.2.1.1 | Room |

| 4.2.2.1.2 | Meal |

| 4.2.2.1.3 | Products/packages |

| 4.2.2.2 | Absence of price discrimination |

| 4.2.3 | Ethical place |

| 4.2.3.1 | Proper location |

| 4.2.3.2 | Absence of unnecessary delay |

| 4.2.4 | Ethical promotion |

| 4.2.4.1 | Absence of sexual appeal |

| 4.2.4.2 | Absence of manipulation |

| 4.2.5 | Islamic finance |

| 4.2.5.1 | Islamic finance transactions |

| 5.0 | FOOD and BEVERAGES |

| 5.1 | Halal-certified restaurant |

| 5.1.1 | Halal breakfasts |

| 5.1.2 | Halal meals (lunch/dinner, etc.) |

| 5.1.3 | Halal room service meals |

| 5.2 | Absence of alcohol |

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Shariah-compliant hotel is a new product in halal tourism that has a huge impact on the national economy. Muslims around the world have special needs and obligations when travelling, and the Shariah-compliant hotel will be able to fulfil some of those needs. Important needs include halal food and beverages, halal products and services, social needs, and the obligation to perform daily prayers. All these needs must be provided by hotels during their guest’s stay.

Nevertheless, due to the unavailability of an established standard, the concept has been applied differently by different hoteliers. This also reflects different definitions of what a Shariah-compliant hotel is and, eventually, reflects different practices among the hoteliers. Furthermore, there is no government-linked certification body for the Shariah-compliant hotel. In the case of the hotel industry, the current certification by JAKIM is solely for halal, which is mainly for food and products. It does not cover other Shariah-compliance aspects as mentioned in this chapter.

Therefore, the Shariah-Compliant Hotel Operations Practices (SCHOP) approach has been developed to fill the gap in current practices. SCHOP aims to cover all aspects of Shariah compliance for a hotel. This would include the administration, common areas, bedroom, services, and food and beverages of the hotel. These practices, in fact, reflect the operations of most hotels in the world. It is hoped that SCHOP provides proper guidelines for hoteliers to achieve better performance and more importantly to achieve the status of the Shariah-compliant hotel.

References

Abuznaid, S. (2012) ‘Islamic marketing: Addressing the Muslim market’, An-Najah University Journal for Research—Humanities, 26 (6): 1473–1503.

Al-Qardhawi, Y. (1995) Halal and Haram dalam Islam. Translated by S.A. Semai. Singapore: Pustaka Islamiyah.

Al-Zuhayli, W. (2002) Financial Transactions in Islamic Jurisprudence. Vol. 2. Translated by M.A. El-Gamal. Damascus: Dar Al-Fikr.

Arham, M. (2010) ‘Islamic perspectives on marketing’, Journal of Islamic Marketing, 1 (2): 149–164.

Aziz, Y.A. (2007) Empowerment and Emotional Dissonance: Employee Customer Relationships in the Malaysian Hotel Industry. PhD. University of Nottingham, UK.

Aziz, Y.A., Hassan, H., Hassan, M.W. and Othman, S. (eds) (2009) Current issues in Tourism & Hospitality Services in Malaysia. Serdang University: Putra Malaysia Press.

Azmi, I.A.G. (2009) ‘Human capital development and organizational performance: A focus on Islamic perspective’, Shariah Journal, 17(2): 353–372.

BERNAMA. (2011) Malaysia to be More Aggressive to Dominate Global Halal Market. [online] Available at: www.halalfocus.com (accessed 7 July 2012).

BIMB Institute of Reseach and Training. (2005) Konsep Syariah Dalam Sistem Perbankan Islam. Kuala Lumpur: BIMB BIRT.

Che Ahmat, N.H., Ahmad Ridzuan, A.H. and Mohd Zahari, M.S. (2012) ‘Customer awareness towards syariah compliant hotel’, paper presented at the International Conference on Innovation Management and Technology Research (ICIMT), Malacca, Malaysia.

Du Rand, G., Heath, E. and Alberts, N. (2003) ‘The role of local and regional food in destination marketing: A South African situation analysis’. In C.M. Hall (ed.) Wine, Food and Tourism Marketing. New York: Haworth Hospitality Press, 97–112.

Hassan, A., Chachi, A. and Latiff, S.A. (2008) ‘Islamic marketing ethics and its impact on customer satisfaction in the Islamic banking industry’, JKAU: Islamic Economy, 21 (1): 27–46.

Henderson, J.C. (2008) ‘Representations of Islam in official tourism promotion’, Tourism Culture and Communication, 8 (3): 135–146.

Henderson, J.C. (2010) ‘Sharia-compliant hotels’, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 10 (3): 246–254.

Ibn Rusyd and Abu Walid Muhammad b. Ahmad al-Hafid. (1981) Bidayah al-Mujtahid waNihayah al-Muqtasid. Vol. Juz 2. Kaherah: Maktabah wa matba’ah Mustafa al-Babi al-Halabi wa Awladih.

Islamic Tourism Centre of Malaysia (ITC). (2017) Muslim-friendly Tour Highlights. [online] Available at: www.itc.gov.my/tourists/discover-the-muslim-friendly-malaysia/islamic-tour-highlights/(accessed 25 September 2017).

Jabatan Kemajuan Islam Malaysia (JAKIM). (1995) E-fatwa. [online] Available at: www.e-fatwa.gov.my/fatwa-kebangsaan/merokok-dari-pandangan-islam (accessed 2 April 2014).

Jabatan Kemajuan Islam Malaysia (JAKIM). (2017) Senarai Hotel & Resort Yang Mendapat Sijil Halal Malaysia (Jakim) [online] Available at: www.halal.gov.my/ehalal/directory_hotel.php (accessed 29 September 2017).

Kana, A.G. (2011) ‘Religious tourism in Iraq, 1996–1998: An assessment’, International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2 (24): 12–20.

Khan, B., Farooq, A. and Hussain, Z. (2010) ‘Human resource management: An Islamic perspective’, Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 2 (1): 17–34.

Malay Mail. (2014) Malaysia Plans to Boost Islamic Tourism Sector, Says Ministry, 4 January. [online] Available at: www.themalaymailonline.com/travel/article/malaysia-plans-to-boost-islamic-tourism-sector-says-ministry#bXSdD42qsAYGY4lw.97 (accessed 29 September 2017).

Malaysian Digest. (2016) Malaysia Expects to Attract 3.2 million Inbound Muslim Tourist Arrivals. [online] Available at: www.malaysiandigest.com/frontpage/29-4-tile/603224-malaysia-expects-to-attract-3-2-million-inbound-muslim-tourist-arrivals.html (accessed 28 September 2017).

Malaysian-German Chamber of Commerce & Industry. (2011) Market Watch Malaysia 2010—The Food Industry. [online] Available at: http://malaysia.ahk.de/fileadmin/ahk_malaysia/Dokumente/Sektorreports/Market_Watch_2010/Food_2010__ENG_.pdf

Metelka, C.J. (1990) The Dictionary of Hospitality, Travel & Tourism. 3rd ed. Albany, NY: Delmar.

Mohamad Azhari, N.H. (2015) ‘Tabung Haji’s Syariah compliant hotels expanding’, BERNAMA, 11 December. [online] Available at: www.bernama.com/en/features/news.php?id=1198350 (accessed 28 September 2017).

Muhammad, R. (2015) ‘The global Halal market—stats & trends’, Halal Focus, 16 January. [online] Available at: http://halalfocus.net/the-global-halal-market-stats-trends/(accessed 12 November 2015).

Nursanty, E. (2012) ‘Halal tourism, the new product in Islamic leisure tourism and architecture’, Department of Architecture; University of 17 Agustus 1945 (UNTAG) Semarang, Indonesia. [pdf] Available at: www.academia.edu/2218300/Halal_Tourism_The_New_Product_In_Islamic_Leisure_Tourism_And_Architecture (accessed 24 February 2019).

Performance Management & Delivery Unit(PEMANDU). )2011) Chapter 10: Revving Up the Tourism Industry. [pdf] Available at: http://etp.pemandu.gov.my/upload/etp_handbook_chapter_10_tourism.pdf (accessed 27 February 2011).

Pew Research Centre. (2011) ‘The future of the global Muslim population’, The Pew Forum on Religious and Public Life, 27 January. [online] Available at: www.pewforum.org/The-Future-of-the-Global-Muslim-Population.aspx (accessed 10 September 2017).

Rajagopal, S., Ramanan, S., Visvanathan, R. and Satapathy, S. (2011) ‘Halal certification: Implication for marketers in UAE’, Journal of Islamic Marketing, 2 (2): 138–153.

Razalli, M.R., Shuib, M.S. and Yusoff, R.Z. (2013) ‘Shariah compliance Islamic Moon (SCI Moon): Introducing model for hoteliers’, paper presented at the Seminar Hasil Penyelidikan Sektor Pengajian Tinggi Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia, UUM.

Rosenberg, P. and Choufany, H. (2009) ‘Spiritual lodging: the Sharia-compliant hotel concept’, HVC-Dubai Office: 1–6.

Sabiq, S. (1983) Fiqh Al-Sunnah. Dar Al-Fikr: Lebanon.

Sahida W., Rahman S.A., Awang, K. and Che Man, Y. (2011) ‘The implementation of Shariah compliance concept hotel: De Palma Hotel Ampang, Malaysia’, paper presented at the Conference on Humanities, Historical and Social Sciences, Singapore.

Seong, L. K. (2011) ‘Halal certification as a spring board for SMEs to access the global market’. The Star Online, 28 May. [online] Available at: www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2011/05/28/halal-certification-as-a-spring-board-for-smes-to-access-the-global-market/(accessed 28 September 2017).

Samori, Z. and Sabtu, N. (2014) ‘Developing hotel standard for Malaysian hotel industry: An exploratory study’, Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 121: 144–157.

Suruhanjaya Sekuriti. (2006) Buku Keputusan Majlis Penasihat Syariah Suruhanjaya Sekuriti. Kuala Lumpur: Suruhanjaya Sekuriti.

Tourism Malaysia. (2009) ‘Malaysia tourism key performance indicators 2009, annual tourism statistical report’. Ministry of Tourism and Culture, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Tourism Malaysia. (2011) ‘Tourism Malaysia—statistics’, Ministry of Tourism and Culture, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. [online] Available at: http://www.tourism.gov.my/statistics (accessed 23 March 2011).

Tourism Malaysia. (2017) ‘Hotel & room supply’, Ministry of Tourism and Culture, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. [online] Available at: http://mytourismdata.tourism.gov.my/?page_id=348#!from=2015&to=2016 (accessed 29 September 2017).

Vejzagic, M. and Smolo, E. (2011) ‘Maqasid Al-Shari’ah in Islamic finance: An overview’, paper presented at the 4th Islamic Economic System Conference, Kuala Lumpur.

Zailani, S., Omar, A. and Kopong, S. (2011) ‘An exploratory study on the factors influencing the non-compliance to Halal among hoteliers in Malaysia’, Journal of Business Management, 5 (1): 1–12.