6

Reproduction, Life Cycles and Growth

John S. Lucas and Paul C. Southgate

6.1 Introduction

Only the three major groups of aquaculture animals will be considered in this chapter: fishes, bivalve molluscs and decapod crustaceans (the last two being the major ‘shellfish’ groups). The fundamental morphologies of the species in these three groups are extremely different (see invertebrate and vertebrate textbooks), as are their reproductive systems, life cycles and patterns of growth. However, although the details and requirements of the various life stages of aquaculture species vary enormously, there are some common patterns. More specific details are included in the appropriate chapters for the various groups and species.

Reproduction, life cycles and growth of seaweeds have some distinctly different features to animals and they are treated in Chapter 15.

6.2 Reproductive Physiology

6.2.1 Fishes

The sexes in most cultured fishes are separate and their paired gonads are located dorsolaterally in the body cavity. Reproductive activity is confined to a particular season of the year. Reproduction is usually triggered by environmental cues, such as increase in day length or water temperature (in temperate and tropical species), or changes in salinity or turbidity (in tropical species). These cues trigger hormonal changes within the animal brought about by stimulation of the pituitary gland.

Hormonal systems are often complex, and the pituitary gland contains three major hormones concerned with reproduction:

- gonadotrophin‐release hormone (GnRH), which controls the release of gonadotrophin from the pituitary;

- gonadotrophin‐release‐inhibitory factors (GnRIF, primarily dopamine), which inhibits the release of gonadotrophin from the pituitary; and

- gonadotrophins (GtHs), which regulate the release of gonadal steroid from the gonad. Gonadotrophins are composed of GtH I (follicle‐stimulating hormone, FSH) and GtH II (luteinising hormone, LH).

The major male and female gonadal steroids are 11α‐ketotestosterone and 17β‐oestradiol, respectively. They control the major aspects of reproduction such as reproductive behaviour, oocyte maturation, spermatogenesis and ovulation. These steroids also have a negative‐feedback influence on GtH production from the pituitary. This hormonal system is shown in Figure 6.1. Although low levels of GtH are found in the blood throughout the year, final maturation of gametes and ovulation is brought about by a surge in GtH levels in response to final environmental cues.

Figure 6.1 The reproductive endocrine physiology of fishes showing the sites of action of LHRHa and HCG used to artificially induce maturation.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Paul Southgate.

Knowledge of this system allows farmers to control reproduction in captivity and obtain spawnings of high‐quality eggs when required. Control of reproduction also allows hatchery managers to plan for maximum food production for larvae and juveniles when needed. In captivity, however, the final environmental cue for reproduction is often lacking. In this case eggs do not undergo final maturation and fishes do not ovulate or spawn because of the lack of a surge in GtH levels. This problem is usually overcome in one of two ways:

- Environmental manipulation. The environmental cues necessary for gamete maturation and spawning are provided. This method requires precise knowledge of the factors governing reproduction in a particular species. Important cues include water temperature, salinity, photoperiod and food availability.

- Hormonal manipulation. The final GtH surge is artificially attained by injection of appropriate hormones into the fish. Although crude pituitary extract can be used, human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) and luteinising hormone‐releasing hormone analogue (LHRHa) are more commonly used.

The actions of these hormones are detailed in Table 6.1 and their points of action within the maturation sequence of fishes are shown in Figure 6.1. The development of current methods used for endocrine manipulation of reproduction in cultured fishes is described by Zohar and Mylonas (2001).

Table 6.1 The actions of human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) and luteinising hormone‐releasing hormone analogue (LHRHa) in influencing reproduction in fishes.

| Hormone | Action |

| HCG | Acts directly on the gonad to induce the release of gonadal steroids (sex hormones) |

| LHRHa | Acts on the pituitary gland to stimulate the release of gonadotrophins (GtH) |

Successful spawning induction depends on a number of factors, which are outlined in the following sections.

6.2.1.1 Stage of Maturity of Brood Fish

Artificial surges in GtH will be an ineffective spawning inducer unless female oocytes have previously reached a certain stage of development. To determine this, a small sample of developing eggs is removed from the female and observed microscopically. Cannulation is used, in which a fine plastic tube is passed up through the oviduct to the ovary. Gentle suction by the mouth at the other end of the tube provides a small sample of eggs for inspection. Eggs must possess yolk globules and be of a certain size. The required size can only be determined experimentally for each species, but, as a rule of thumb, they should be at least half the diameter of eggs at spawning. Ripe males should exude milt (sperm suspension) from the genital opening when pressure is applied to the abdomen.

6.2.1.2 The Correct Hormone to Use and Hormone Dose

hCG and LHRHa are the preferred hormones for spawning induction in fishes; both are available commercially and available in purified form:

- LHRHa is more effective in bringing about oocyte maturation. It is usually used at a dose of 10–50 µg/kg fish; and

- hCG is usually used at doses of 250–2000 IU (international units of activity) per kg of fish.

Initially, a mid‐range dose is used, and the optimum dose is determined by trial and error. If the dose is too low, it will fail to induce a spawning. Too high a dose will cause final oocyte maturation to occur too rapidly and will result in poor egg quality. A very low dose will be effective if the oocytes are very mature (determined by cannulation).

6.2.1.3 Method of Hormone Administration

Hormones are administered either intramuscularly (IM) (Figure 6.2) or intraperitoneally (IP) (into the body cavity). IM injections have the disadvantage of hormone loss when the needle is withdrawn; however, minimising the injection volume can reduce this. IP injections avoid the problem of hormone loss but can result in damage to internal organs or injection into the intestine, where the hormone will be ineffective.

Figure 6.2 Intramuscular injection of hormones into Eurasian Perch, Perca fluviatilis.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Tomáš Policar.

Hormones can also be administered as a pellet containing the hormone. The hormone is mixed with cholesterol and compressed to form a pellet, which is injected into the muscle. The advantage of using pellets is that the release of the hormone into the blood system occurs more evenly and does not result in a sudden increase in hormone levels as does liquid injection. Cellulose can also be incorporated into the pellet to help regulate the rate of hormone release: the more cellulose, the slower the rate of release.

6.2.1.4 Timing of Hormone Administration

Hormonal induction of spawning is more successful if the hormone is administered so that spawning occurs at a time of day when it would occur naturally. To achieve this, knowledge of the time of natural spawnings and the length of time taken between hormone administration and ovulation (‘latent period’) is required. For example, barramundi spawn naturally after dark and have a latent period of ca. 36 hr. Therefore, the hormone is administered at around 7am to induce a spawning after dark the following night.

As detailed above, GnRIF inhibits the release of GtH within the pituitary (Figure 6.1). GnRIF is actually dopamine, and dopamine antagonists such as pimozide and domperidone can block its inhibitory action. Thus, spawning may be facilitated by administering a dopamine antagonist to brood fish. The use of a combination of GnRIF analogue (e.g., LHRHa) and a dopamine antagonist (e.g., domperidone) to induce ovulation and spawning of cultured fishes is known as the ‘Linpe method’. A mix of LHRHa (stimulating GtH) and pimozide (inhibiting GnRIF) is now available commercially and spawning kits are available for the major groups of cultured fishes such as carps and salmonids.

6.2.2 Decapod Crustaceans

The sexes in cultured decapod crustaceans are separate, and the paired gonads are located dorsally and laterally to the gut. Their reproduction and gonad maturation are hormonally regulated. Synthesis and release of crustacean reproductive hormones occur in response to both exogenous and endogenous factors and, in the wild, reproduction is closely related to seasonal cues. These seasonal cues are similar to those for fishes, e.g., photoperiod, water temperature and food availability.

Reproduction in decapod crustaceans is controlled by hormones released from the sinus gland and associated centres (X‐organ and Y‐organ). These glands which secrete fundamental hormones for the body’s functioning are surprisingly located within the eyestalks. The hormones are gonad‐inhibiting hormone (GIH), moult‐inhibiting hormone (MIH) and several other hormones. A commonly used technique to induce reproductive maturation in shrimps is eyestalk ablation. This removes the eye, together with the eyestalk and its source of hormones. Eyestalk ablation is usually unilateral (applied to one eye only) and is achieved by:

- cutting off the eyestalk; or

- cauterising, crushing or ligaturing the eyestalk.

In females, ablation results in an increase in total ovarian mass, owing to the acceleration of primary vitellogenesis and the onset of secondary vitellogenesis. In males, ablation induces spermatogenesis, enlargement of the vas deferens and hypersecretion in the androgenic gland. Eyestalk ablation also removes the source of MIH and other compounds that control moulting (ecdysis). Reproduction in decapod crustaceans is often characterised by a pre‐copulation or pre‐spawning moult.

Gonad maturation after ablation can be very rapid in shrimps, and females can develop full ovaries within 3–4 days. As in other arthropods, the spermatozoa of decapod crustaceans have no flagella and are non‐motile. At mating, the male inserts a spermatophore (a large bundle of the non‐motile spermatozoa) into a ventral receptacle for the spermatophore (thelycum) or onto the ventral surface of a female shrimp near her gonadophore. Fertilisation occurs externally upon ovulation and passage of the oocytes through the gonadophore, and the eggs are shed into the water column. Spermatophores may remain implanted through several ovarian maturation cycles and may fertilise as many as six spawnings within one moult cycle. The spermatophores are lost with the moulted exoskeleton.

Copulation in decapod crustaceans typically involves a soft‐shelled female that has just moulted and a hard‐shelled male. As decapod crustaceans moult regularly (section 6.4.2), it means that fertilisation can be reliably obtained by keeping female and male broodstock together in appropriate conditions. This is used for hatchery production in freshwater prawns, freshwater crayfish, crabs, lobsters and some shrimp species. In the groups other than shrimps, the fertilised eggs are not shed into the water column but are retained on the female’s abdominal appendages (pleopods) until the larvae or juveniles hatch (Figure 23.11). Females brooding eggs on their pleopods are known as ‘berried’ or ovigerous females. More detailed information on the reproductive biology of decapod crustaceans is provided by Mente (2008).

6.2.3 Bivalve Molluscs

Most species of cultured bivalves have separate sexes, but the total situation within the group is more complex than in cultured fishes and decapod crustaceans. Some cultured bivalves, e.g., some scallops, are hermaphrodites with eggs and sperm produced simultaneously. Other bivalves change sex during development. Usually these are protandrous, with younger individuals being male and older individuals being female. Some bivalves may undergo more than one change (often annually) in functional sexuality and are said to show rhythmic consecutive hermaphroditism (e.g., Ostrea species). Although the causes of sex change in bivalves are poorly understood, gene‐activated components that respond to environmental factors, sex‐determining genes and food supply have all been suggested.

As in fishes and decapod crustaceans, gamete maturation in bivalves is influenced by a number of exogenous factors, including water temperature, food availability, light intensity and lunar periodicity. It is also influenced by endogenous factors including hormones, genetic factors and levels of endogenous energy reserves. Gonad maturation in bivalves relies on both direct food intake and utilisation of endogenous energy reserves. Water temperature is perhaps the major influence on gonad maturation in bivalves. However, the relationship between increased water temperature and increased natural phytoplankton production (food availability) is also very important.

Major spawning cues for bivalves include a change in water temperature, a change in salinity, lunar periodicity and chemicals (pheromones) associated with water‐borne gametes from other individuals. With the exception of lunar periodicity, these are commonly used to induce spawnings in bivalve hatcheries (section 6.3.2). Gametes are generally liberated into the surrounding water where they are fertilised. In some species (e.g., Ostrea edulis), fertilised eggs are retained in the mantle cavity, where they develop into swimming larvae before being released. More detailed information on the reproductive biology of bivalve molluscs can be found in Chapter 24 and in Gosling (2002).

6.3 Life Cycles

6.3.1 Sequence of Stages

At breeding, mature adults shed their eggs and sperm freely into the water or the male impregnates the female. Fertilisation results in a zygote and subsequently an embryo, which develops within the egg. Embryonic development occurs over a period of hours or days, depending on the species and temperature. In a typical life cycle for a species with planktonic larvae, the embryo emerges from the egg as a swimming larva that develops into a juvenile over a period of days, weeks or even, in some species, months. This may be a progressive process, as in shrimps and most fish; or the larva may abruptly settle out of the plankton onto an appropriate substrate and metamorphose into a juvenile, as in bivalves and other benthic invertebrates. The juvenile then grows progressively over a period of months or years until it reaches sexual maturity and the life cycle is completed (Figure 6.3).

From the viewpoint of aquaculture, these life cycles can be divided into the following sequence of stages:

- broodstock conditioning to produce ripe adults for spawning;

- spawning, either natural or induced (the latter being more common in aquaculture);

- egg fertilisation;

- larval rearing;

- postlarval and juvenile rearing;

- grow‐out rearing to commercial size; or

- grow‐out rearing to sexual maturity for use in breeding.

Figure 6.3 Generalised life cycle of a pearl oyster (Pinctada species) showing the phases of culture.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Paul Southgate.

In the intensive aquaculture of a species, many of these phases in the life cycle require different culture techniques (Figure 6.4). For example, different culture methods are used for larvae, juveniles and grow‐out stock in the intensive culture of bivalves, shrimps and fishes. In extensive aquaculture, however, there may be very little change in culture techniques throughout all phases of the life cycle, e.g., extensive culture of tilapia and freshwater crayfish.

Figure 6.4 How typical stages in aquaculture relate to the generalised life‐cycle stages of animals in aquaculture.

Source: Reproduced with permission from John Lucas.

6.3.2 Broodstock Selection and Conditioning

This involves selecting appropriate animals to serve as sources of gametes. It may involve selecting stock with particular genetic traits (Chapter 7). In many cases the broodstock are simply obtained from the field (Figure 6.4) and there is no opportunity for selective breeding to improve the aquaculture‐related attributes of the species. As described, most aquatic animals become sexually mature and reproduce during the warmer months of the year in response to increasing photoperiod, food availability and rising water temperature. Knowing the major cues for gonad maturation, conditions in an aquaculture hatchery can be manipulated to bring on sexual maturity outside natural reproductive seasons. This is known as broodstock conditioning, and it allows hatchery production on a year‐round basis.

6.3.3 Spawning

Methods of inducing spawning in individual species and groups are described in detail in other chapters. However, it is appropriate to summarise these methods in five categories:

- Mild stress, such as abrupt temperature increases, e.g., with bivalves.

- Manipulation of the body’s reproductive hormones by injection or implantation of reproductive hormones into the body in fishes or by eyestalk ablation in shrimps.

- Transfer of gametes from a container where animals have spawned to one where they have not and thus allowing the pheromones associated with gametes to trigger responses from the recipients, e.g., bivalves.

- Gonad stripping, where the broodstock is known to have ripe gametes. The body is appropriately massaged to expel gametes, e.g., fishes (Figure 6.5, Figure 17.2), or gonads are removed from a sacrificed animal and lacerated to release gametes, e.g., bivalves (section 24.4.2.1).

- Injecting a neurotransmitter substance directly into the gonad of a ripe animal, presumably to cause gonad contractions, e.g., some bivalves.

Figure 6.5 Stripping eggs from pikeperch, Sander lucioperca.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Tomáš Policar.

It is evident that the greatest range of induced spawning techniques is used with bivalves (section 21.4.2). To an extent this reflects the fact that they are more readily induced to spawn than fishes or shrimps.

6.3.4 Egg Fertilisation

Where the broodstock sexes are segregated, fertilisation involves mixing an appropriate amount of sperm suspension with a suspension of eggs. The objective is to run a course between low fertilisation rates, as a result of insufficient sperm, and polyspermy, where eggs are penetrated by a number of sperm. When an egg is penetrated by a sperm, its surface often changes to prevent further sperm penetration. If, however, sperm are very abundant, other penetrations may occur before the barrier is established and the egg then contains two or more haploid nuclei from sperm. These may result in a polyploid (2+n) zygote and the subsequent embryo develops abnormally.

6.3.5 Larval Rearing

Embryonic development is usually a brief process, from a few hours to several days duration. It requires the developing embryos to be cleaned of any debris and chemicals from spawning induction and fertilisation. The embryos need to be maintained in finely filtered (e.g., 0.2–2 µm) water to reduce levels of bacteria, which may potentially invade the surfaces of the eggs. Developing embryos must also be provided with adequate levels of DO.

The larval stages of most fishes, crustaceans (Figure 6.6) and bivalves (Figure 26.13) are planktotrophic, i.e., dependent on exogenous food supplies for much of their development. When larvae first hatch, however, they usually have sufficient energy reserves in the yolk to support development for a day or more before they need to feed (Figures 19.7). These reserves were present in the egg and were passed on from the mother. Fish larvae, for example, do not develop a functional gut until some time after hatching: they depend on endogenous reserves until they can support themselves by feeding on appropriate foods in their environment (Figure 6.7). The embryos and early larval stages of most aquatic animals utilise lipids and proteins from yolk reserves to fuel development to this point. It has been estimated, for example, that embryonic development in some bivalves utilises about 70% of the lipid reserves of the egg. Bivalve larvae must again rely on endogenous energy reserves at the end of larval development, during metamorphosis, when they temporarily lose the ability to feed. Unlike fishes and crustacean larvae, which retain the ability to feed during the steady transition from larva to juvenile, bivalve larvae must accumulate substantial energy reserves during larval development. In some gastropod species, e.g., abalone and trochus, the eggs contain sufficient nutrient reserves to support larval development through to the juvenile phase without the larva having to feed. This lecithotrophic development is usually relatively brief and associated with relatively large and yolky eggs.

Figure 6.6 The life cycle of the mud crab, Scylla serrata, showing successive developmental stages.

Source: Holme et al. 2009. Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

Figure 6.7 Diagram showing early development in salmonids. E, eye development of embryo inside the egg; Fe, fertilised egg; H, hatching with large yolk sac; S, larva beginning to seek external food; Re, completion of yolk sac resorption and total reliance on exogenous nutrition.

Source: Kamler 1992. Reproduced with permission from Springer. Adapted from Raciborski 1987.

The life cycles of freshwater animals often differ from this general pattern in that planktonic larval stages are omitted or much abbreviated. This is known as direct development. Freshwater species with direct development typically produce larger and yolkier eggs than related marine animals (Figure 23.11). These large eggs support a comparatively longer embryonic period to result in the hatching of juveniles or near‐juveniles. The eggs are usually protected during this long embryonic development and the adult may carry them, e.g., on the female crayfish’s pleopods or in the mouths of some fishes, or there may be ‘nests’ and patterns of reproductive behaviour to protect broods of eggs. (Egg‐protecting behaviour also occurs in some freshwater and marine fishes that have normal larval stages.)

Direct development occurs in freshwater crayfish, but giant freshwater prawns, Macrobrachium species, and the mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis, have larval stages. They must migrate downstream to saline water to release the larvae, which cannot survive in freshwater.

Planktotrophic larval development is often the most demanding phase of the life cycle for aquaculture, and it can last from several days to many weeks (or even months in the case of rock lobsters, section 2.8.1). The larvae are physically and physiologically fragile. They require well‐controlled environmental parameters, such as DO, pH, N waste levels, bacterial populations, levels of organic and inorganic particles, and temperature. They are often reared in large tanks to buffer these environmental parameters; but tank culture also has hazards, such as contamination and pathogenic bacterial blooms.

As the larvae switch from relying on their endogenous yolk reserves to feeding, providing appropriate food becomes a major aspect of larval culture. There are two main forms of food:

- microalgae for the filter‐feeding larvae of molluscs and shrimps; and

- rotifers and brine shrimp nauplii for the larvae of fishes and older larvae of shrimps (Chapter 9).

Larval density is important in hatchery culture. The advantage of high larval density is that more postlarvae can be produced per unit volume of culture tank. However, if larval density is too high, it may compromise water quality and affect larval growth and survival. The culture tank water is usually changed at regular intervals to maintain water quality. The density of larvae is reduced as they grow, despite inevitable attrition that reduces numbers. If 1 larva/mL of culture water completes development, this corresponds to one million larvae from 1000 L of culture water. Aquaculture hatcheries use larval rearing tanks up to 20 000 L and produce tens of millions of postlarvae per rearing (Figure 3.9).

Ponds may be used to provide very larger volumes for rearing larvae. Even with low densities of larvae this can result in very large numbers of postlarvae, e.g., tonnes of megalopae of Eriocheir sinensis are produced in this way in China (section 23.3.3.3).

6.3.6 Postlarval and Juvenile Rearing

It is necessary to provide appropriate substrates in the culture system to induce bivalve larvae to settle (section 24.4.2.4). The larvae are selective because, at settlement and metamorphosis, they attach and make a habitat commitment for the remainder of their lives. For fishes and shrimp larvae there is no abrupt metamorphosis. There is, however, a progressive change in behaviour of shrimp postlarvae as they become more substrate oriented. The same pattern occurs in benthic fishes.

Marine and brackish water crabs, such as portunid swimming crabs, are another example of an abrupt metamorphosis from planktonic larval stages to the first benthic juvenile stage. In this case it is via a transitional megalopa stage.

The early part of this period is often a particularly difficult one for rearing fishes, as the post‐metamorphic juveniles must be progressively weaned off live feeds onto artificial diets. Standard procedures have been developed for the major culture species (section 9.5.1), but this is often one of the particular points of difficulty in developing the culture process for a new fish species.

Post‐metamorphic juveniles of fishes, decapod crustaceans and bivalves are very small, physiologically fragile and vulnerable to predation. Over a period of days to months or more than a year, they are grown in protected conditions, before they are put out into the grow‐out environment. This may involve a period of culture in tanks at the hatchery and an onshore nursery, followed by a period of protected culture in ponds or in the field. Care is required to minimise mortality when transferring juveniles from the relative comfort of the hatchery (e.g., adequate feed and filtered water, which may be heated above ambient temperature to pond or field nursery conditions with cooler water, fluctuating food supply, predators, disease and fouling.

6.3.7 Grow‐out Rearing

Grow‐out rearing is the final phase, during which the juveniles are put out into the adult environment and reared until being harvested (Figure 6.4). They are not treated in the same manner throughout this phase: factors such as food pellet size, pond size and mesh sizes of protective or enclosing nets, may be varied as they grow.

6.3.8 Other Considerations

In some cases, the whole culture process from spawning broodstock to final marketing takes place on one farm. In other cases, the cultured organisms may be sold several times during the culture process. Broodstock may be captured by fishing or reared by a specialist farm and sold to the hatchery. Late larval stages or early juveniles are often sold from a specialist hatchery to nursery growers. Juveniles ready to be grown out may be sold from a specialist nursery to grow‐out farms. This is because the different phases of culture require particular expertise and facilities, and there is efficiency of specialisation. Most typically, the culture process involves a hatchery or hatchery/nursery selling juveniles to farmers, because the hatchery aspect is most technically demanding and because one hatchery can supply many farms. In some Asian countries, such as Taiwan, this process is taken further. There is a series of specialised facilities with expert technical staff who culture specific early‐development stages of fishes. During development, the fishes may be sold on to other facilities a number of times. Each facility may culture equivalent stages of a number of species.

Many aquaculture industries rely on natural recruitment of juveniles, thereby omitting the more technically demanding phases of aquaculture outlined in sections 6.3.2 to 6.3.6. Relying on natural recruitment is possible by knowing the times and localities of this recruitment, and other biological information about the recruits, such as settlement substrate. It may be possible to stock coastal ponds with recruits, for example, juvenile fishes, shrimps or crabs, by filling the ponds at high tides when juveniles are abundant in the adjacent inshore waters. Alternatively, the recruits may be netted from coastal water when they are abundant and then stocked into ponds. In the case of bivalve larvae, it is a matter of providing appropriate substrates to attract late‐stage larvae to settle from the water column (Figure 24.8). In freshwater ponds, the adults may be allowed to mate and care for their eggs, and then the juveniles are removed at an appropriate stage. There may still be several commercial stages in this process, whereby juveniles from the field, obtained from privately‐owned settlement substrates or by fishing, are sold to farmers for grow‐out.

Natural recruitment is often the start of an extensive or semi‐intensive culture process, i.e., where the stocking rate is low to moderate, and capital is limited. It is the basis of many major aquaculture industries, but there are inherent problems. As in fisheries, that natural recruitment levels vary from year to year and are not completely predictable in time. Fishing pressure on the wild adult stock may reduce its reproductive output and hence natural recruitment. Another disadvantage of relying on natural recruitment is that there is no opportunity for stock improvement. It is impossible to select for desirable traits for aquaculture.

6.4 Growth

6.4.1 Size vs. Age

There are two patterns of growth occurring simultaneously in many developing organisms.

- Absolute growth rate, e.g., rate of increase in length or mass per unit time, which is quite insignificant initially, when the animal is very small (Figure 6.8). Then, as the animal grows, its capacity to feed and assimilate food progressively increases. The absolute growth rate increases and the size vs. age curve becomes steeper. This is known as the exponential phase of growth.

- Relative growth rate, e.g., growth increment / unit body mass / unit time, is very rapid during the early phases of an animal’s life cycle (Figure 6.8). Relative growth may be 200% and more during the first week or so of development and remain at a high level during the early months.

Figure 6.8 Generalised curves of size, absolute growth rate and relative growth rate vs. age.

Source: Reprinted from Malouf & Bricelj (1989) with permission from Elsevier Science.

The size vs. age relationship reflects the changing pattern of absolute growth, producing a sinusoidal curve (Figure 6.8). There is an upper inflection in the size vs. age curve, and the upper curve typically slopes gently towards a final theoretical size, L∞, which it would reach if the animal lived indefinitely.

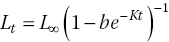

Some complex logistic equations, such as the von Bertalanffy growth function (VBGF), are used to describe the relationship between size and age. One form of the VBGF is:

where Lt is size at time t; L∞ is maximum size; b and K are growth coefficients; b is related to the ratio of maximum size to initial size; and K is the growth coefficient, often used in comparisons of growth rates between populations and species.

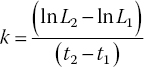

However, over short periods of measurement (months), when the animals are in the exponential (rapid) phase of growth, a relative growth coefficient can be obtained from the following equation:

where L1 is size at initial time t1 and L2 is size at final time t2

This growth coefficient, k, is readily calculated and is widely used in comparative studies.

6.4.2 Growth in Decapod Crustaceans

Growth in decapod crustaceans basically follows the pattern outlined in section 6.4.1. The pattern of growth is, however, complicated by moulting, whereby the animal sheds its old exoskeleton (Figure 6.9) and expands rapidly during a short period before a new exoskeleton hardens. Thus, growth appears to occur in a series of abrupt steps rather than as a continuous process (Figure 6.10). The details of the moult cycle are outlined in Table 6.2.

Figure 6.9 A pile of moulted shells (exuviae) from mitten crabs, Eriocheir sinensis.

Source: Reproduced with permission from John Lucas.

Figure 6.10 Staircase‐like pattern of growth of decapod crustaceans with moults to expand in size by ‘inflation’ alternating with hard‐shelled periods (instars) during which the animal is fixed in size externally, but it feeds and grows tissue.

Source: Reproduced with permission from John Lucas.

Table 6.2 Events in the moult cycles of decapod crustaceans, from one inter‐moult period (instar X) to the next (instar X + 1).

| Phase | Duration1 | External body size | Organic tissue mass | Behaviour | Shell |

| Intermoult (instar X) | Days–weeks | Fixed | Increasing | Feeding; locomotion | Hard |

| Pre‐moult | Hours–several days | Little change | Decreasing = > increased organics in body fluids | Ceasing feeding; may seek cover | Shell decalcifying |

| Moult | Minutes–hours | Rapid increase | Low | Rapidly shedding old shell; no feeding; may be concealed | Old shell discarded; new soft shell |

| Post‐moult | Hours–days | Little change | Begins increasing | Begins feeding | Hardening |

| Intermoult (instar X+ 1) | Days–weeks (months2) | Fixed | Increasing | Feeding, locomotion | Hard |

1 The durations of the stages are correlated with the animal’s size: small size = short durations: large size = long durations.

2 Last instars of some large species, e.g., marine lobsters, mud crabs, which may cease moulting (terminal anecdysis)

The decapod crustacean’s life is divided into a series of ntermoult periods or instars, which may be numbered consecutively for convenience. These are punctuated by moults (or ecdyses) and the animal continues to moult, unless it goes into a final terminal instar when it ceases to moult (terminal anecdysis). The moults are more frequent earlier in life and the size increments at moults are relatively larger, but absolutely smaller. The result is a size vs. age relationship that fundamentally looks like the relationship in Figure 6.8, but with a stepwise pattern instead of a smooth curve (Figure 6.10).

The processes of:

- moulting to expand body dimensions; and

- growth, in terms of adding organic tissue and energy content.

are completely independent (Table 6.2). The decapod crustacean feeds and builds up organic tissue during the intermoult period. This is the critical period of growth, although there is no change in external dimensions: body size is constrained by the exoskeleton. The animal does not feed during the periods immediately before, during and after moulting. Its shell is too soft for feeding and it is vulnerable. It is ironic that it is the period of non‐growth, although it is the period when the soft‐shell body expands rapidly by absorbing water.

6.4.3 Energetics of Growth

The growth rate depends on the extent to which net energy intake exceeds metabolic rate and to what extent energy is diverted from growth to reproduction in mature animals (section 8.5). Energy committed to gametogenesis is a major component of the body’s resources in many aquaculture animals. Hence gametogenesis is at least part of the cause for growth tapering off with age.

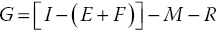

The energy for growth may be expressed as a summation of input and outputs.

where G is the growth rate; I is the food ingestion rate; M is the metabolic rate; E is the excretion rate of waste molecules from metabolism; F is faeces production; R is gametogenesis; and [I – (E + F)] is the net rate of energy intake, i.e., food intake – (excreted wastes and faeces). The equation can be expressed as net rate of energy intake less energy spent of metabolism and reproduction:

or

6.4.4 Measuring Growth

6.4.4.1 General

Growth rate often needs to be measured accurately. It is a means of predicting when the stock will be ready for harvest. Suboptimum growth rates draw attention to factors such as poor health, inadequacy of feeds and nutrition, poor environmental quality, poor source of stock, etc., that may be adversely influencing performance.

The change in size of a substantial representative sample of the cultured organisms must be measured to determine the growth rate. For example, an appropriate sample from each pond on a shrimp farm may be at least 100 individuals. The size of aquaculture organisms may be measured in various ways, but different methods are more appropriate for seaweeds, fishes, bivalves and crustaceans. The four main measurements of size used in aquaculture are:

- A linear dimension measured with callipers or a ruler, according to size. The advantages of this method are that it is quick and easy, and the animal is not unduly harmed. The disadvantages are that it cannot be used for flexible organisms (e.g., seaweeds) and it does not give an indication of the condition (fat/thin) of the animal.

- Wet weight of the whole living organism, weighed on scales. The advantage of this method is that it is quick and easy, and the animal is not unduly harmed.

- Dry weight. The dead organism, or a quantified piece of it, is dried in an oven at ~50 °C until all moisture has evaporated. The advantages of this method are that it gives a tissue weight value that is not complicated by water content and the value is relatively quickly and easily obtained.

- Ash‐free dry weight (AFDW). Once the dry weight of an organism (or piece of it) is determined, it is heated in a furnace at ca. 500 °C for ca. 24 hr. All organic molecules are burnt off in the furnace, leaving only inorganic ash. The weight of ash is then subtracted from the dry weight. This gives the AFDW, which is the dry weight of organic matter in the animal. Animal or tissue sample dry weight – AFDW = dry weight of organic matter. Knowing the amount of organic matter in an animal is a very accurate measure of size. A particular advantage of AFDW determinations is that it is accurate for animals with large inorganic components, such as shells (e.g., bivalves), for which it is difficult to estimate organic tissue content because it is relatively small. A less accurate alternative to AFDW is to use Condition Index (section 6.4.4.3).

Determining dry weight and AFDW requires specialised equipment such as a drying oven, 500 °C furnace (Figure 6.11) and a sensitive balance. As such, these are the prerogative of laboratory studies that require very accurate data. Linear measurements and wet weights are used to assess size or growth on farms.

Figure 6.11 A laboratory muffle furnace of the kind that is used to deternmine ash‐free dry weight. Metal or porcellaine crucibles are used to contain samples in the furnace and tongs are used to handle the crucibles.

Source: Cjp24 2009. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Share‐Alike Licence, CC BY‐SA 3.0.

It is often sufficient for the farmer to observe measured growth, but in some circumstances, there may be a need to calculate growth rates, e.g., for comparisons of growth rate through the seasons or between batches. The growth rate may be calculated on the assumption of linear growth, i.e., change in size over period of measurement. However, as illustrated in Figure 6.8, growth is not linear. The growth coefficient provided in section 6.4.1 can be used as a more accurate value for comparisons of relative growth rate, provided the animals are in the appropriate phase of growth.

6.4.4.2 Fishes

Fish length has long been used as an assessment of size and growth. Two measurements are typically used:

- Standard length (SL). SL is measured from the tip of the snout to the base of the caudal fin (tail). In fish larvae, however, SL is from the tip of the snout to the tip of the notochord.

- Total length (TL). TL is measured from the tip of the snout to the tip of the caudal fin. However, measuring TL may be inaccurate if there is damage to the caudal fin, and it is difficult to measure accurately in larvae and juveniles.

As noted previously, length takes no account of fatness or condition of a fish and may therefore be a poor guide to tissue growth. Consequently, wet weight is also frequently used for size and growth assessment, usually in combination with length.

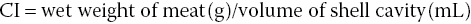

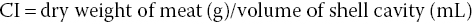

6.4.4.3 Bivalve Molluscs

Bivalves are usually assessed in terms of shell dimensions, e.g., shell length (SL), shell height (SH) and shell width (SW). If only one dimension is used, as is often the case, it is the largest dimension of the shell. This is not the same in all bivalves, e.g., the largest shell dimension is SH in oysters, SL in mussels and often SW in clams.

The major problem with shell dimensions as a measure of growth is that they take no account of tissue growth. The bivalve shell tends to grow, regardless of the condition of the animal. The shell may increase at a slow rate while tissue mass declines. This can occur during periods of low phytoplankton abundance or adverse environmental conditions or disease. Shell increments in these circumstances only show apparent growth and this is where AFDW determinations would show the true state of the tissue and bivalve health.

There is also a simpler method for determining the relative amount of tissue in relation to the shell. This is called the condition index (CI) and is a quantitative measure used in commercial aquaculture, primarily to assess reproductive condition:

or

Volume of shell cavity can be determined by immersing an intact bivalve and then measuring the displaced water.

The CI is used for table oysters and is more concerned with gonad condition and how ‘fat’ the oysters are than with tissue growth per se.

6.4.4.4 Decapod Crustaceans

Decapod crustaceans tend to be measured by a linear measurement of their carapace. Crabs, with a carapace that is broader than it is long, have their maximum carapace width (CW) measured. Other decapod crustaceans, shrimps, freshwater prawns, freshwater crayfish, etc., with carapaces that are longer than broad have their carapace lengths (CL) measured. These latter groups of crustaceans have well‐developed abdomens. These tend to flex vigorously when they are held, hindering total length measurements, which are therefore not usually used.

Because of the moult cycle, the water content of decapod crustacean tissues is very variable and wet weight measurements of a few individuals are dubious. Wet weight measurements of large groups of individuals are more reliable as they accommodate the range of moult conditions in the group. The mean wet weight is determined, and this has the advantage of being more rapid than taking individual carapace measurements.

Frequency of moulting is a fair indication of relative growth rate in a cultured population of decapod crustaceans, but it is difficult to assess. It is no substitute for size measurements.

6.5 Summary

- The sexes in most cultured fishes are separate. Reproductive activity is naturally confined to a particular season of the year and usually responds to environmental cues, such as increase in day length or water temperature. These trigger hormonal changes controlled by the pituitary gland.

- Knowledge of these cues and of hormonal control of reproduction allows control of fish reproduction in hatcheries through environmental manipulation and by hormonal injection.

- Reproduction in decapod crustaceans is controlled by hormones released from the sinus gland and associated centres (X‐organ and Y‐organ) located within the eyestalks. The hormones include gonad‐inhibiting hormone (GIH) and moult‐inhibiting hormone (MIH) and a commonly used technique to induce reproductive maturation in shrimps is eyestalk ablation. Eyestalk ablation is usually unilateral (applied to one eye only).

- Most bivalves have separate sexes and reproductive maturation is influenced by exogenous factors such as water temperature and food availability. Major spawning cues for bivalves include a change in water temperature, a change in salinity, lunar periodicity and chemicals (pheromones) associated with water‐borne gametes from other individuals. Gametes are generally liberated into the surrounding water where they are fertilised.

- The life cycle of aquaculture animal includes: broodstock conditioning to produce ripe adults for spawning; spawning, either naturally or induced (the latter being more common in aquaculture); egg fertilisation; larval rearing; postlarval and juvenile rearing; grow‐out rearing to commercial size; or grow‐out rearing to sexual maturity for use in breeding.

- Growth in decapod crustaceans is complicated by moulting and growth appears to occur in a series of abrupt steps rather than as a continuous process. The decapod crustacean’s life is divided into a series of intermoult periods or instars.

- Linear measurements are most often used to assess growth rates of aquaculture animals, but determining dry weight or ash‐free dry weight (organics content) provides a more accurate measure of tissue growth.

References

- Raciborski, K. (1987). Energy and protein transformation in sea trout (Salmo trutta L.) larvae during transition from yolk to external food. Polskie Archiwum Hydrobiologii, 34, 437–502.

- Gosling, E. (2002). Bivalve Molluscs, Biology, Ecology and Culture. Fishing News Books. Blackwell Publishing, UK. 443 pp.

- Kamler, E. (1992). Early Life History of Fish: An Energetics Approach. Chapman & Hall, London. 267 pp.

- Malouf, R.E. and Bricelj, V.M. (1989). Comparative biology of clams: environmental tolerances, feeding and growth. In: Clam mariculture in North America, J. Manzi, M. Castagna (eds.), Elsevier, New York. pp. 23–73.

- Mente, E. (2008). Reproductive Biology ofCcrustaceans: Case Studies of Decapod Crustaceans. CRC Press. 565 pp.

- Zohar, Y. and Mylonas, C.C. (2001). Endocrine manipulations of spawning in cultured fish: from hormones to genes. Aquaculture, 197, 99–136.