If you're new to web design, you may need some helpful hints to guide your forays into HTML (and to steer clear of well-intentioned, but out-of-date HTML techniques). Or if you've been building web pages for a while, you may have picked up a few bad HTML-writing habits that you're better off forgetting. The rest of this chapter introduces you to some HTML writing habits that will make your mother proud—and help you get the most out of CSS.

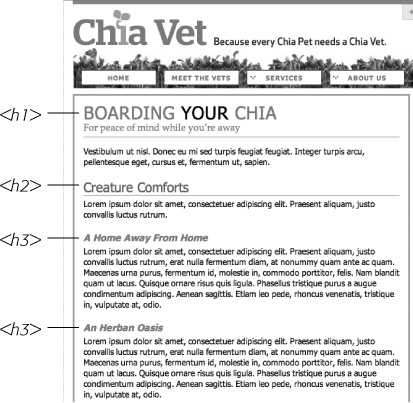

HTML adds meaning to text by logically dividing it and identifying the role that text plays on the page: For example, the <h1> tag is the most important introduction to a page's content. Other headers let you divide the content into other, less important, but related sections. Just like the book you're holding, for example, a web page should have a logical structure. Each chapter in this book has a title (think <h1>) and several sections (think <h2>), which in turn contain smaller subsections. Imagine how much harder it would be to read these pages if every word just ran together as one long paragraph.

Note

For a good resource on HTML/XHTML check out HTML & XHTML: The Definitive Guide by Chuck Musciano and Bill Kennedy (O'Reilly), or visit www.w3schools.com for online HTML and XHTML tutorials. For a quick list of all available HTML and XHTML tags, visit www.w3schools.com/tags/.

HTML provides many other tags besides headers for marking up content to identify its role on the page. (After all, the M in HTML stands for markup.) Among the most popular are the <p> tag for paragraphs of text and the <ul> tag for creating bulleted (non-numbered) lists. Lesser-known tags can indicate very specific types of content, like <abbr> for abbreviations and <code> for computer code.

When writing HTML for CSS, use a tag that comes close to matching the role the content plays in the page, not the way it looks (see Figure 1-2). For example, a bunch of links in a navigation bar isn't really a headline, and it isn't a regular paragraph of text. It's most like a bulleted list of options, so the <ul> tag is a good choice. If you're saying, "But items in a bulleted list are stacked vertically one on top of the other, and I want a horizontal navigation bar where each link sits next to the previous link," don't worry. With CSS magic you can convert a vertical list of links into a stylish horizontal navigation bar as described in Chapter 9.

HTML's motley assortment of tags doesn't cover the wide range of content you'll probably add to a page. Sure, <code> is great for marking up computer program code, but most folks would find a <recipe> tag handier. Too bad there isn't one. Fortunately, HTML provides two generic tags that let you better identify content, and, in the process, provide "handles" that let you attach CSS styles to different elements on a page.

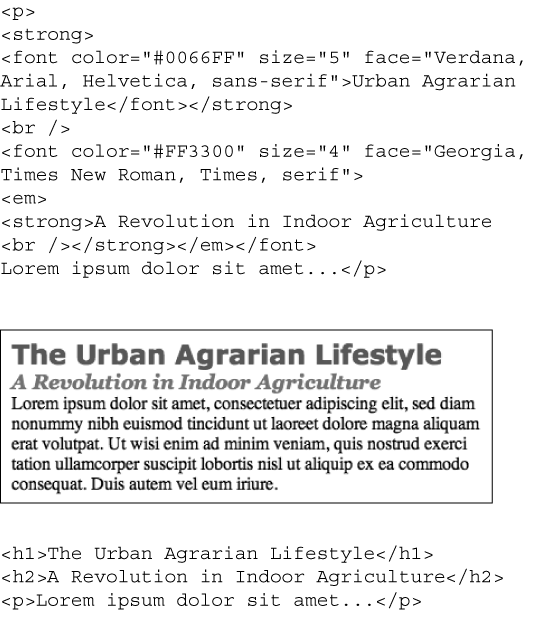

Figure 1-2. Old School, New School. Before CSS, designers had to resort to the <font> tag and other extra HTML to achieve certain visual effects (top). You can achieve the same look (and often a better one) with a lot less HTML code (bottom). In addition, using CSS for formatting frees you up to write HTML that follows the logical structure of the page's content.

The <div> tag and the <span> tag are like empty vessels that you fill with content. A div is a block, meaning it has a line break before it and after it, while a span appears inline, as part of a paragraph. Otherwise, divs and spans have no inherent visual properties, so you can use CSS to make them look any way you want. The <div> (for division) tag indicates any discrete block of content, much like a paragraph or a headline. But more often it's used to group any number of other elements, so you can insert a headline, a bunch of paragraphs, and a bulleted list inside a single <div> block. The <div> tag is a great way to subdivide a page into logical areas, like a banner, footer, sidebar, and so on. Using CSS, you can later position each area to create sophisticated page layouts (a topic that's covered in Part III of this book).

The <span> tag is used for inline elements; that is, words or phrases that appear inside of a larger paragraph or heading. Treat it just like other inline HTML tags such as the <a> tag (for adding a link to some text in a paragraph) or the <strong> tag (for emphasizing a word in a paragraph). For example, you could use a <span> tag to indicate the name of a company, and then use CSS to highlight the name using a different font, color, and so on. Here's an example of those tags in action, complete with a sneak peek of a couple of attributes—id and class—frequently used to attach styles to parts of a page.

<div id="footer"><p>Copyright 2006,<span class="bizName">CosmoFarmer.com</span></p> <p>Call customer service at 555-555-5501 for more information</p></div>

This brief introduction isn't the last you'll see of these tags. They're used frequently in CSS-heavy web pages, and in this book you'll learn how to use them in combination with CSS to gain creative control over your web pages (see the box on ID Selectors: Specific Page Elements).

CSS lets you write simpler HTML for one big reason: You can stop using a bunch of tags and attributes that only make a page better looking. The <font> tag is the most glaring example. Its sole purpose is to add a color, size and font to text. It doesn't do anything to make the structure of the page more understandable.

Here's a list of tags and attributes you can easily replace with CSS:

Ditch <font> for controlling the display of text. CSS does a much better job with text. (See Chapter 6 for text-formatting techniques.)

Stop using <b> and <i> to make text bold and italic. CSS can make any tag bold or italic, so you don't need these formatting-specific tags. However, if you want to really emphasize a word or phrase, then use the <strong> tag (browsers display <strong> text as bold anyway). For slightly less emphasis, use the <em> tag (browsers italicize content inside this tag).

Skip the <table> tag for page layout. Use it only to display tabular information like spreadsheets, schedules, and charts. As you'll see in Part III of this book, you can do all your layout with CSS for much less time and code than the table-tag tango.

Eliminate the awkward <body> tag attributes that enhance only the presentation of the content: background, bgcolor, text, link, alink, and vlink set colors and images for the page, text, and links. CSS gets the job done better (see Chapter 7 and Chapter 8 for CSS equivalents of these attributes). Also trash the browser-specific attributes used to set margins for a page: leftmargin, topmargin, marginwidth, marginheight. CSS handles page margins easily (see Chapter 7).

Don't abuse the <br> tag. If you grew up using the <br> tag (<br /> in XHTML) to insert a line break without creating a new paragraph, then you're in for a treat. (Browsers automatically—and sometimes infuriatingly—insert a bit of space between paragraphs, including between headers and <p> tags. In the past, designers used elaborate workarounds to avoid paragraph spacing they didn't want, like replacing a single <p> tag with a bunch of line breaks and using a <font> tag to make the first line of the paragraph look like a headline.) Using CSS's margin controls you can easily set the amount of space you want to see between paragraphs, headers, and other block-level elements.

Note

In the next chapter, you'll learn about a technique called a "CSS Reset" which eliminates the gaps browsers normally insert between paragraphs and other tags (see Starting with a Clean Slate).

As a general rule, adding attributes to tags that set colors, borders, background images, or alignment—including attributes that let you format a table's colors, backgrounds, and borders—is pure old-school HTML. So is using alignment properties to position images and center text in paragraphs and table cells. Instead, look to CSS to control text placement (see Indenting the First Line and Removing Margins), borders (Adding Borders), backgrounds (Determining Height and Width), and image alignment (CSS and the <img> Tag).

It's always good to have a map for getting the lay of the land. If you're still not sure how to use HTML to create well-structured web pages, then here are a few tips to get you started:

Use only one <h1> tag per page, and use it to identify the main topic of the page. Think of it as a chapter title: You only put one title per chapter. Using <h1> correctly has the added benefit of helping the page get properly indexed by search engines (see the box on Two New HTML Tags to Learn).

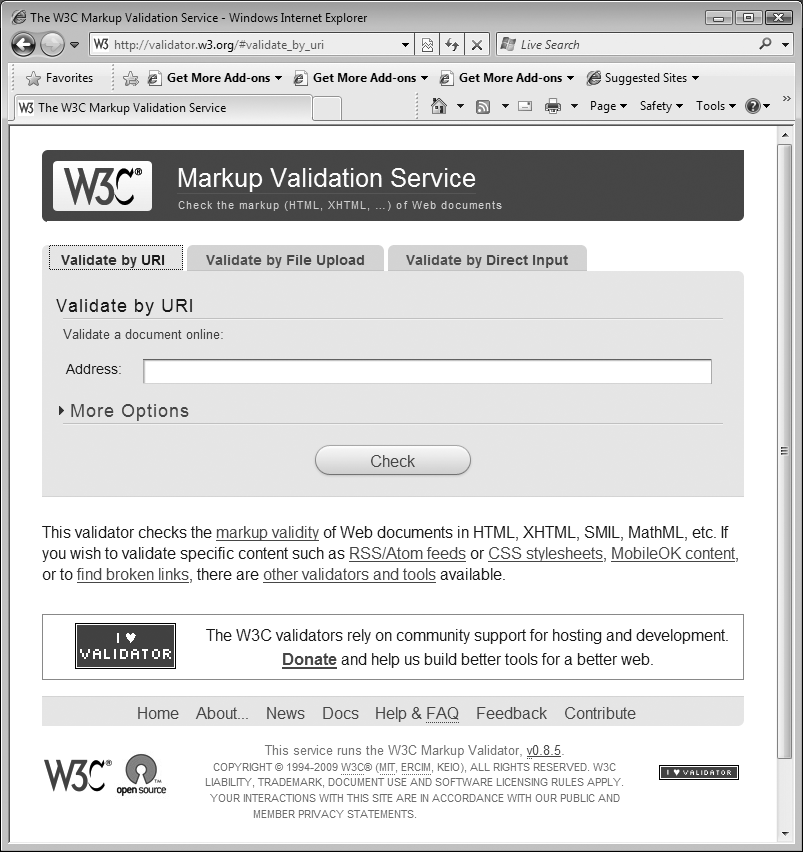

Figure 1-3. The W3C HTML validator located at http://validator.w3.org lets you quickly make sure the HTML in a page is sound. You can point the validator to an already existing page on the Web, upload an HTML file from your computer, or just type or paste the HTML of a web page into a form box and then click the Check button.

Use headings to indicate the relative importance of text. Again, think outline. When two headings have equal importance in the topic of your page, use the same level header on both. If one is less important or a subtopic of the other, then use the next level header. For example, follow an <h2> with an <h3> tag (see Figure 1-4). In general, it's good to use headings in order and try not to skip heading numbers. For example, don't follow an <h2> tag with an <h5> tag.

Use unordered lists when you've got a list of several related items, such as navigation links, headlines, or a set of tips like these.

Use numbered lists to indicate steps in a process or define the order of a set of items. The tutorials in this book (see Formatting Lists) are a good example, as is a list of rankings like "Top 10 websites popular with monks."

To create a glossary of terms and their definitions or descriptions, use the <dl> (definition list) tag in conjunction with the <dt> (definition term) and <dd> (definition description) tags. (For an example of how to use this combo, visit www.w3schools.com/tags/tryit.asp?filename=tryhtml_list_definition.)

If you want to include a quotation like a snippet of text from another website, a movie review, or just some wise saying of your grandfather's, try the <blockquote> tag for long passages or the <q> tag for one-liners.

Take advantage of obscure tags like the <cite> tag for referencing a book title, newspaper article, or website, and the <address> tag to identify and supply contact information for the author of a page (great for a copyright notice).

As explained in full on HTML to Forget, steer clear of any tag or attribute aimed just at changing the appearance of a text or image. CSS, as you'll see, can do it all.

When there just isn't an HTML tag that fits the bill, but you want to identify an element on a page or a bunch of elements on a page so you can apply a distinctive look, use the <div> and <span> tags (see The Importance of the Doctype). You'll get more advice on how to use these in later chapters (for example, Don't Forget Margins and Padding).

Don't overuse <div> tags. Some web designers think all they need are <div> tags, ignoring tags that might be more appropriate. For example, to create a navigation bar, you could add a <div> tag to a page and fill it with a bunch of links. A better approach would be to use a bulleted list (<ul> tag). After all, a navigation bar is really just a list of links.

Remember to close tags. The opening <p> tag needs its partner in crime (the closing </p> tag), as do all other tags, except the few self-closers like <br> and <img> (<br /> and <img /> in XHTML).

Validate your pages with the W3C validator (see Figure 1-3 and the box on Tips to Guide Your Way). Poorly written or typo-ridden HTML causes many weird browser errors.