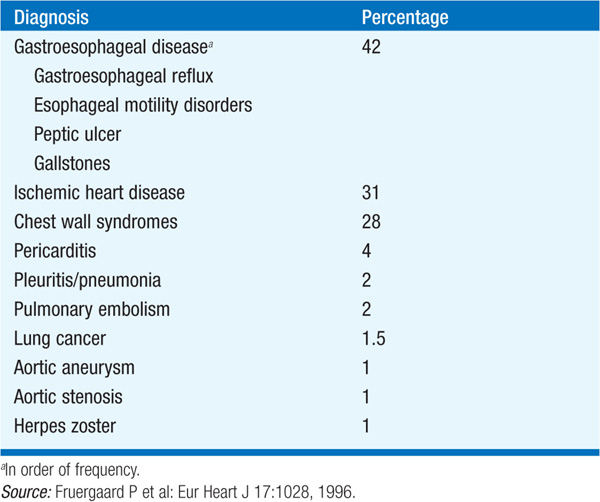

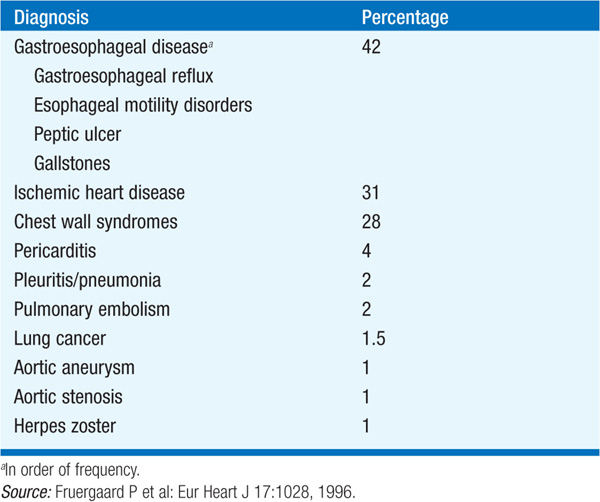

There is little correlation between the severity of chest pain and the seriousness of its cause. The range of disorders that cause chest discomfort is shown in Table 37-1.

TABLE 37-1 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES OF PATIENTS ADMITTED TO HOSPITAL WITH ACUTE CHEST PAIN RULED NOT MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION

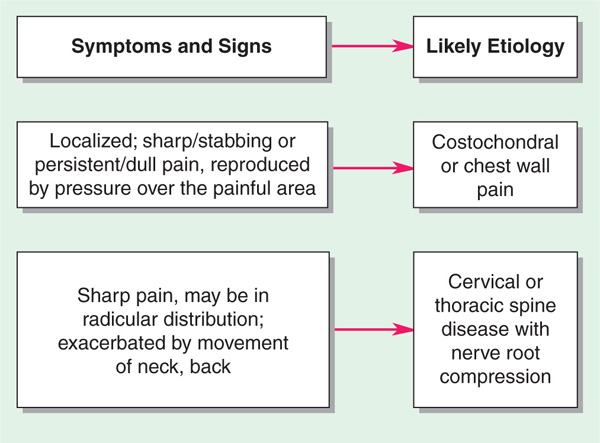

The differential diagnosis of chest pain is shown in Figs. 37-1 and 37-2. It is useful to characterize the chest pain as (1) new, acute, and ongoing; (2) recurrent, episodic; and (3) persistent, e.g., for days at a time.

FIGURE 37-1 Differential diagnosis of recurrent chest pain. *If myocardial ischemia suspected, also consider aortic valve disease (Chap. 123) and hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (Chap. 124) if systolic murmur present.

FIGURE 37-2 Differential diagnosis of acute chest pain.

Substernal pressure, squeezing, constriction, with radiation typically to left arm; usually on exertion, especially after meals or with emotional arousal. Characteristically relieved by rest and nitroglycerin.

Similar to angina but usually more severe, of longer duration (≥30 min), and not immediately relieved by rest or nitroglycerin. S3 and S4 common.

May be substernal or lateral, pleuritic in nature, and associated with hemoptysis, tachycardia, and hypoxemia.

Very severe, in center of chest, a sharp “ripping” quality, radiates to back, not affected by changes in position. May be associated with weak or absent peripheral pulses.

Sharp, intense, localized to substernal region; often associated with audible crepitus.

Usually steady, crushing, substernal; often has pleuritic component aggravated by cough, deep inspiration, supine position, and relieved by sitting upright; one-, two-, or three-component pericardial friction rub often audible.

Due to inflammation; less commonly tumor and pneumothorax. Usually unilateral, knifelike, superficial, aggravated by cough and respiration.

In anterior chest, usually sharply localized, may be brief and darting or a persistent dull ache. Can be reproduced by pressure on costochondral and/or chondrosternal junctions. In Tietze’s syndrome (costochondritis), joints are swollen, red, and tender.

Due to strain of muscles or ligaments from excessive exercise or rib fracture from trauma; accompanied by local tenderness.

Deep thoracic discomfort; may be accompanied by dysphagia and regurgitation.

Prolonged ache or dartlike, brief, flashing pain; associated with fatigue, emotional strain.

(1) Cervical disk disease; (2) osteoarthritis of cervical or thoracic spine; (3) abdominal disorders: peptic ulcer, hiatus hernia, pancreatitis, biliary colic; (4) tracheobronchitis, pneumonia; (5) diseases of the breast (inflammation, tumor); (6) intercostal neuritis (herpes zoster).

APPROACH TO THE PATIENT Chest Pain

A meticulous history of the behavior of pain, what precipitates it and what relieves it, aids diagnosis of recurrent chest pain. Fig. 37-2 presents clues to diagnosis and workup of acute, life-threatening chest pain.

An ECG is key to the initial evaluation to rapidly distinguish pts with acute ST-elevation MI, who typically warrant immediate reperfusion therapies (Chap. 128).

For a more detailed discussion, see Lee TH: Chest Discomfort, Chap. 12, p. 102, in HPIM-18.