9

CURRICULUM PLANNING IN THE 21ST CENTURY

Ronald M. Harden

An authentic curriculum to meet the needs of the population should be designed as a collaborative activity with students and teachers playing a key role.

The changing concept of a curriculum

The concept of a medical curriculum changed dramatically over the latter part of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st century. Fresh thinking about the education process led to the integration of previously fragmented elements and to a reappraisal of the role of the teacher as a facilitator of learning rather than simply a transmitter of information. The student came to be seen as a partner in the learning process rather than a product of it or a consumer. Within medical schools, the responsibility for the curriculum switched from departments working independently and headed by powerful professors to curriculum-planning committees representing the different stakeholders.

Curricular issues addressed related to the mission of the medical school, the learning outcomes, the curriculum content, the sequence of courses, the educational strategies, the teaching and learning methods, the assessment procedures, the educational environment, communications about the curriculum and management of the process (Harden and Laidlaw 2012). With regard to educational strategies, the SPICES model described a continuum from student-centred to teacher-centred; problem-based to information-centred; integrated to discipline-based; community-based to hospital-based; electives to uniform and systematic to opportunistic.

In this chapter we focus on four aspects of curriculum planning that reflect current educational thinking and the direction in which medical education is moving in the 21st century. These trends also recognise the importance of the international dimensions of medical education. They are:

• the authentic curriculum;

• the curriculum as a collaborative activity;

• the student and the curriculum;

• the teacher and the curriculum.

The authentic curriculum

Medical schools have been accused of working in ivory towers, out of touch with the needs of society and the community which the doctors who graduate have to serve. This is no longer acceptable politically, professionally, economically or educationally. Frenk et al. argued that, ‘Professional education has not kept pace with these challenges [in healthcare delivery] largely because of fragmented, outdated, and static curricula that produce ill-equipped graduates’ (2010: 1923). Relevance is today a key and much promoted principle in medical education and is reflected in the concept of an ‘authentic’ curriculum. Changing public and professional expectations as to what is expected of a doctor, as discussed in Chapters 2 and 3, were factors that led to the introduction of an outcome- or competency-based approach to education (see Chapter 3). In the past, curricula favoured the mastery of knowledge. The gap between the theoretical knowledge of students and their clinical competence, including their communication skills and professionalism, has been highlighted. The move to an authentic curriculum is about ensuring that on graduation students have the necessary skills to practice effectively for the patient’s benefit. Learning outcomes such as communication skills, professionalism and issues such as patient safety, management of errors and teamwork are addressed. Students are trained, as described in the Mozambique case study, to be able to practise in a rapidly changing healthcare environment, to cope with unfamiliar situations, to confront the unknown and to use judgement. The emphasis on appropriate learning outcomes is highlighted in the case studies from the UK and Peru.

Case study 9.1 The University of Dundee curriculum, United Kingdom

Gary Mires and Claire MacRae

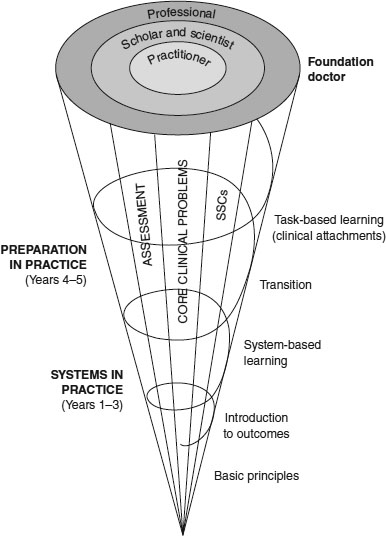

The curriculum at the University of Dundee School of Medicine is a 5-year programme with approximately 160 students in each academic year of study. The programme delivered is outcome-based, structured around the General Medical Council’s (GMC’s) Tomorrow’s Doctors learning outcomes (GMC 2009) and uses an assessment-to-a-standard approach. This means that students must achieve the specified outcomes to a defined standard at each stage of the course before being allowed to progress to the next. We use a constructivist approach to curriculum planning, resulting in a ‘spiral curriculum’ where students are given opportunities to revisit aspects of learning, building on what they already know. As new information and skills are introduced, students are encouraged to make links between concepts, deepening their understanding (Figure 9.1).

The core curriculum emphasises the competencies necessary for a newly qualified doctor to work in the hospital or community. In Years 1–3 in the Systems in Practice (SiP) programme, students undertake a body systems-based programme where normal and abnormal structure, function and behaviour in relation to clinical medicine are studied systematically in modules (e.g. cardiovascular, respiratory and gastrointestinal systems). In Years 4 and 5, students follow the Preparation in Practice (PiP) programme. Students apply the skills and knowledge acquired in the earlier years in a variety of clinical settings in hospital and in general practice. Towards the end of this phase students serve in doctor apprenticeships and focus on preparation for early postgraduate training. Student-selected components (SSCs) provide the student with opportunities to study areas of interest in more detail while developing transferable skills such as ability to conduct literature reviews or select research methods.

We have adopted a problem-oriented approach to learning in Dundee. Around 100 core clinical problems (CCPs) are used to provide students with ‘real’ examples as a focus for learning. This gives us the flexibility to use a wide range of educational delivery methods, including lectures, small-group teaching, traditional ‘bedside’ teaching encounters, elements of problem-based learning (PBL), team-based learning (TBL) and e-learning. Students are exposed to the clinical environment from Year 1, and are taught in a variety of clinical settings, including hospital wards, the community and the clinical skills centre, using models, simulators and simulated patients. Learning is integrated, with a number of longitudinal ‘themes’ such as medical ethics and prescribing running through the course, and this is reinforced through an Integrating Science and Specialities programme where students are encouraged to use self-directed learning and research, and to apply knowledge they have already gained in earlier parts of the course to core clinical problems to investigate solutions, think widely across systems and use basic principles when considering how to solve a problem.

Throughout the course, students use interactive online study guides designed to help them manage their own learning as they progress through the programme. The guides help students to understand what they should be learning, indicate the learning opportunities available and encourage students to assess the extent to which they have mastered the subject.

The delivery of an ‘authentic’ curriculum is reflected in the course content, the teaching and learning approaches, the learning opportunities provided, the student assessment and in the context for learning. The emphasis in the UK case study is on equipping the graduate with the competencies necessary to work as a doctor in a hospital or in the community. The Mozambique and Peru case studies show, even in difficult circumstances, how a community-based curriculum that pays attention to the required knowledge and skills in the local context can prepare students for practice. In Peru, students have contact with patients early in the curriculum and their attachment to health centres in the community is reported as contributing to the development of communication skills and an awareness of the local health situation, including the social dimensions of health and the need for prevention and promotion of health. As described in both the Mozambique and Peru case studies, PBL has proved to be an attractive educational strategy in part because it placed the basic medical sciences in the context of a clinical problem. This is described further in Chapter 10.

Case study 9.2 Training competent doctors for sub-Saharan Africa – experiences from an innovative curriculum in Mozambique

Janneke Frambach and Erik Driessen

Healthcare in sub-Saharan Africa faces a disproportionate share of the global disease burden as well as a radical shortage of physicians. Medical schools in the region cope with a lack of qualified faculty and poor infrastructure. Mozambique is a country in the south-east of sub-Saharan Africa that faces one of the most challenging healthcare situations in the world. The country has three doctors per 100,000 inhabitants, compared with the World Health Organization (WHO) African region average of 22 per 100,000. Mozambique’s gross national income per capita is 2.5 times lower than the regional average, and prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is 2.5 times higher (WHO 2012).

The Faculty of Medicine of the Catholic University of Mozambique was founded in 1995, opened its doors to students in 2000 and graduates an average of 25 doctors annually. Admittance depends on academic performance after a preparatory year. The 6-year curriculum is problem- and community-based, and has been characterised as ‘an instructive example of innovative African medical education’ (Sub-Saharan African Medical Schools Study (SAMSS) 2009: 6). The main educational methods are small-group sessions, independent study, lectures, laboratory training, communication and clinical skills sessions with real patients in a ‘university clinic’ located inside the faculty building. In a community programme each student is attached to three families for 4 years, and clinical rotations in the final 2 years. Clinical training is mainly hospital-based, with a rotation in a rural area and a primary care rotation in a health centre.

Training competent doctors for a sub-Saharan African context means preparing students to confront an extremely challenging work environment. This is a difficult task for medical schools in the region, especially as they cope with shortages of adequately trained (clinical) teachers and poor resources and infrastructure. Notwithstanding these limitations, an innovative curriculum can contribute to preparing students for practice in this demanding context (Frambach et al. 2014):

• The PBL method stimulates an inquiring and independent attitude, which helps graduates deal with unfamiliar situations, e.g. as a hospital manager, in handling shortages and when encountering unfamiliar disease presentations.

• The communication and clinical skills sessions and the community programme stimulate a holistic approach towards patients, which helps to overcome communication obstacles, to discuss traditional medicine issues and to consider the influence of socio-cultural aspects.

• The diversity of curriculum elements stimulates a varied range of knowledge and skills in the social and cognitive domains, which helps graduates to enact the different roles expected of them in practice.

• The school provides an overall positive learning climate, which enhances graduates’ motivation to confront the challenges in practice.

Clinical rotations are highly valued as a preparation for practice, but their effectiveness is compromised by a lack of adequate clinical teaching and supervision.

A clinical presentation or task-based curriculum (Harden et al. 2000), with its focus on the clinical problems and tasks facing a doctor, strongly supports the principle of an authentic curriculum. As described in the UK case study, the curriculum is built around 100 common clinical tasks facing a doctor, for example the management of a patient with abdominal pain, with the basic science and clinical skills related to the task. The use of simulators and virtual patients, augmenting but not replacing experience with real patients, provides students with practical experience not otherwise available to them and emphasises the development of the required clinical skills and at the same time the relevance of an understanding of the basic medical sciences.

The authentic curriculum is reflected also in the move in assessment from a reliance on written tests of knowledge to performance assessments such as the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE), work-based assessment and portfolio assessment, as described in Chapters 17–19.

The ethical and professional objectives that link curricula with healthcare needs are high on today’s agenda. This is reflected in all aspects of curriculum planning, from the specification of learning outcomes to the integration of clinical and basic science teaching, the use of interprofessional education, the creation of appropriate learning opportunities, including experience in the community and performance-based assessment. Related to the authentic curriculum is the concept of the social accountability and responsibility of a medical school. This is one of the areas where excellence in medical education is acknowledged in the ASPIRE-to-excellence initiative (www.ASPIRE-to-excellence.org).

The curriculum as a collaborative activity

Collaboration between the key players or actors and between the different stakeholders was for the most part absent in the traditional curriculum. It can be argued that in the years ahead major advances in education will come about through collaboration among the range of stakeholders locally, nationally and internationally.

Collaboration between disciplines in the medical curriculum

Horizontal integration is now well established as a curriculum strategy. Subjects that are normally taught in the same phase of the curriculum, like anatomy, physiology and biochemistry in the early years of medicine and surgery, paediatrics and obstetrics and gynaecology in the later years, cooperate in the delivery of the education programme most commonly through system-based courses. In a cardiovascular system module, for example, students study the heart from the perspectives of the different disciplines. As illustrated in the case studies from Peru, the UK and Mozambique, this is now standard practice around the world. In vertical integration there is integration between the basic sciences and the clinical elements of the course, with students introduced to patients from the first year of the curriculum and continuing to study the basic sciences and their clinical relevance in the later years.

The rationale and benefits of integration have been described by Bandaranayake (2011) and stages on a continuum from isolation to full integration are set out in Harden’s Integration Ladder (Harden 2000).

Case study 9.3 Outcome-based curriculum in a new medical school in Peru

Graciela Risco de Domínguez

Peru, located on the west coast of South America, has a population of 30 million people whose epidemiological profile is characterised by mostly preventable infectious diseases, a growing incidence of chronic conditions and some emergent health problems. One-third of the population, mostly poor and rural, is underserved or does not have access to healthcare at all. This situation is exacerbated by a critical deficit of healthcare professionals, added to their unequal distribution across the country.

Students enter medical school directly from high school. Medical studies take 7 years, including 1 year of hospital-based internship. There are 30 medical schools in Peru. The Medical School of the Peruvian University of Applied Sciences (UPC-MS), in Lima, was founded in 2007 with the vision to innovate medical education in Peru.

The design of the new curriculum took into account the main characteristics of the Peruvian medical education and major international trends in medical education informed by visits to leading foreign medical schools. The healthcare needs of the Peruvian population were analysed through indepth interviews and focus groups with the main local stakeholders and using the available statistical information. A leading consulting company in Peru (Apoyp ConsultorÍa 2005) conducted a prospective study of the new scenarios of professional practice. Based on this information the mission of UPC-SM was established:

(Apoyp Consultoría 2005)

Ten learning outcomes were identified based on the Global Minimum Essential Requirements of the Institute for International Medical Education (IIME) (Schwarz and Wojtczak 2002), adapted in line with the school’s mission, and the courses and the curriculum were built around them.

Horizontal integration of basic and pre-clinical sciences with clinical sciences was implemented from the first semester using initially TBL and later PBL. Vertical integration was ensured throughout four curricular threads, with each thread integrating a group of courses and curricular activities. Students’ personal development was achieved through early contact with patients and health services. This helped students to acquire communication skills and ethics competences and at the same time built on the awareness about the health situation of the population. The scientific research thread ends with the completion of a thesis which is required for graduation. Clinical reasoning and clinical skills are developed using bedside training, ambulatory facilities and simulation. The Public Health and Primary Care thread, which is critical in the curriculum, begins in the first semester and continues until the eighth semester. Training is done at health centres and in the community, where students learn about prevention, promotion and social determinants of health.

Student assessment includes competence-based strategies such as OSCEs and mini-clinical evaluation exercises (Mini-CEXs). The organisational structure of the UPC-SM does not include academic departments. Curriculum thread coordinators facilitate curriculum integration.

Lessons learned from the experience included:

• the creation of a new medical school is an opportunity for innovation in medical education;

• it is possible to design a curriculum according to the modern trends in medical education, but with very particular characteristics adapted to the reality of the country;

• the implementation of an innovative curriculum requires a great deal of teacher training;

• a new curriculum requires a new organisational structure for the medical school;

• students who have just graduated from high school do well in TBL and PBL;

• a curriculum of 7 years allows the development of the general competencies by the student. It also allows the articulation of the basic sciences with professional training.

Collaboration among the different professions

High on today’s agenda is a discussion about the place of interprofessional education. Many mistakes in medical practice are a result of poor teamwork and communication between doctors, nurses, midwives and other healthcare professions. If healthcare professionals have to work together effectively in clinical practice, it is argued that they should learn to do so as part of the medical curriculum. This is discussed further in Chapter 14.

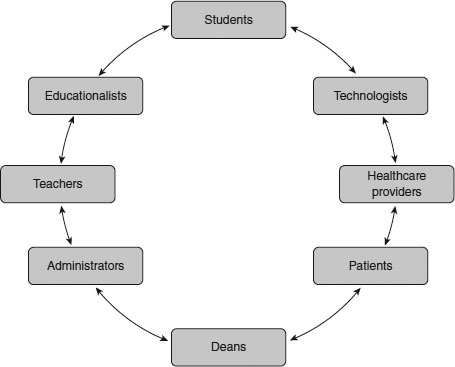

Collaboration among the different stakeholders

In planning and implementing a curriculum, the need for collaboration goes beyond the different subject experts working together to deliver an integrated programme. All of the stakeholders, as illustrated in Figure 9.2, should work together in the planning and implementing of a curriculum – in specifying the learning outcomes and in planning the approaches to teaching, learning and assessment.

Collaboration among those responsible for the different phases of education

Much attention has been paid to collaboration between disciplines in the context of the undergraduate or basic medical curriculum. The situation is different across the phases of education with the different phases – undergraduate, postgraduate and continuing education – operating in silos with little or no communication between them. Less attention has been paid by medical schools, specialty organisations and regulating bodies to collaboration across the different phases. The level of collaboration can be seen as a continuum (Table 9.1) and progress is being made from a position of isolation to a higher level of collaboration.

Local, national and international collaboration

Looking to the future, medical schools are unlikely to survive as self-sufficient entities that provide all aspects of their teaching, learning and assessment programme. Such independence will become even more difficult with increasing specialisation in medicine and with the need for students to access high-quality online learning resources and simulations. These are expensive to produce and may be beyond the budget of an individual school. At the same time there are demands to equip students with an international perspective of medicine that goes beyond their local setting and which provides them with the skills required of an international citizen. These include a sound knowledge of global issues, the skills for working in an international context and the values for a global citizen.

Table 9.1 Levels of collaboration across the different phases of education

| Isolation |

There is no communication between the different phases |

| Awareness |

Each phase has a level of awareness of the training programme in other phases |

| Cooperation |

There is a measure of collaboration with, for example, an agreement as to the learning outcomes for each phase and planned progression of students and trainees |

| Coordination |

Some joint planning can be seen across the different phases, for example, with collaboration in the development of learning resources and learning opportunities |

| Integration |

The boundaries between the phases become blurred or disappear |

More clearly defined learning outcomes, as described in Chapter 3, will support the unbundling of the curriculum and a sharing of learning resources, learning experiences and assessments. The experience in Peru, as highlighted in the case study, demonstrated how a curriculum can be based on international trends in medical education, but adapted to the local contexts with collaboration by local stakeholders.

The student and the curriculum

The student is a key factor in the curriculum. There has been a significant change in perceptions of the students’ role and their contribution to the education process. The student is no longer seen as a product of the education system or as a consumer, but rather as a partner in the learning process.

Student-centred learning

In the traditional teacher-centred curriculum the emphasis is on the teacher and what is taught. By contrast, in a student-centred approach the emphasis is on the student and what is learned. The teacher’s responsibility is to facilitate this. As described in the UK case study, students are encouraged to take responsibility for their own learning assisted by study guides and a clear statement of the expected learning outcomes.

Curriculum developments such as PBL, TBL, peer-to-peer learning, and the flipped classroom are consistent with this move toward student-centred learning. The move to student-centred learning is supported by new learning technologies, as discussed in Chapter 16.

Personalised adaptive learning

In healthcare, attention is being focused on personalised medicine, where the individual needs of each patient are addressed. In education, too, there is a move to an education programme personalised to the needs of the individual student, recognising that, just as with patients, each student is different in terms of their abilities, their previous experience, their learning styles and their aspirations. A greater understanding of how students learn and the availability of an increasingly powerful range of tools in the teacher’s tool kit makes this possible. While fundamental changes to the curriculum to support adaptive learning may be some time away, there is much that the teacher can do today to move in this direction. The use of electives or SSCs is an example. Learning activities can be scheduled so that in sessions with simulators in the clinical skills laboratory, the students’ time allocated is related to their mastery of the skills. What is fixed is the standard students achieve, not the time to achieve it.

Student engagement

How students engage with the delivery of the educational programme will vary from institution to institution depending on social, cultural and other issues. What is certain, however, is that the concept of the student as a stakeholder and partner in the learning process, as described in Chapter 7, is attracting increasing attention. This may manifest in different ways, as outlined in the ASPIRE-to-excellence criteria for excellence in student engagement in a medical school (www.ASPIRE-to-excellence.org). Students take on an active role on curriculum and other committees and are consulted, involved and participate in the policy decisions and in the shaping of the teaching and learning experience. Students may be involved also in the delivery of the teaching programme as a peer teacher or as a developer of learning resources. Students may be engaged in the medical school’s research programme and may represent the school and contribute to national and international education meetings.

The teacher and the curriculum

We have highlighted above the importance of the student. For a curriculum to be successful, the role of the teacher is also important. There is good evidence that the input of the teacher is as significant as, if not even more significant than, the design of the curriculum. Teaching in medicine is a challenging activity that requires, if the teaching is to be effective and the students’ needs addressed, an understanding of medicine and the subject content as well as a mastery of a range of teaching skills. Teacher training is important, particularly as illustrated in the case study from Peru, when an innovative curriculum is introduced.

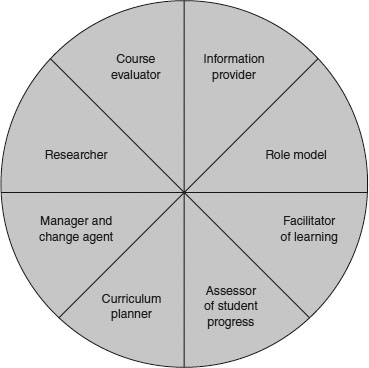

The role of the teacher has changed in recent years, reflecting different public and professional expectations of the training and the product, developments in technology, new educational approaches and increasing engagement of the student. The teacher has a number of roles in the curriculum (Figure 9.3).

Information provider

The teacher can be a direct source of information, knowledge and skills for the student directly through the delivery of lectures, small-group work and teaching in the clinical or laboratory context. The teacher can also assist the student to acquire knowledge from hand-outs, textbooks and a wide range of online resources.

The teacher has a responsibility to help the student address the problem of information overload by advising on the learning outcomes and the selection of learning experiences to address the outcomes from the opportunities available. The teacher should guide the student as to how best to access, select and evaluate the rich range of possible resources. The teacher may prepare resource materials in print or electronic format and communicate with students through social networks such as blogs, Facebook or Twitter. The teacher should also identify the ‘threshold concepts’ essential for a student’s understanding of the subject.

Role model

‘We must acknowledge’, suggested Tosteson (1979: 690), when Dean at Harvard Medical School, ‘that the most important, indeed the only, thing we have to offer our students is ourselves. Everything else they can read in a book.’ Role modelling is a powerful tool through which the medical teacher can pass on appropriate attitudes and values. Effective role models are important in medical education: they help to shape the values, attitudes, behaviour and ethics of students. They also have important influences on career choices. Role models, as William Osler advocated more than a century ago, improve students’ learning by example. Students often pattern their activities on their teacher’s behaviour, including their interactions with patients and their communication skills and ethical practice.

Role modelling may have a negative as well as a positive effect on the student. A dissonance is created, for example, when students having been taught the principles of ethical behaviour see a bad example in clinical practice. Many of the attributes associated with a good role model, however, can be acquired and strategies are available to help doctors to become better role models (Cruess et al. 2008).

Facilitator of learning

The role of the teacher has changed from being ‘a sage on the stage’ to ‘a guide on the side’. Rather than the teacher’s role being the transmission of information and skills to the student, the teacher now has a responsibility as a facilitator of learning: the good teacher can be defined as someone who does this most effectively. The teacher can facilitate learning in many ways. As described in the Mozambique case study, the teacher can help to create within the medical school an education environment that supports the learning of the students and encourages appropriate learning behaviour. The learning outcomes and the learning opportunities available can be made explicit and communicated to the student in such a way that learning is facilitated. Study guides can be prepared to serve as a guide or tutor for the student when the teacher is not available. In activities in the more formal curriculum, such as PBL, as described in the UK case study, the teacher has an important role to play as a facilitator.

Motivation of learning is an under-researched and often ignored aspect of medical education. The teacher should work with individual students to support, motivate and inspire them, and promote a sense of ownership of the course and their studies. Working with students on their portfolio can be a rewarding experience and can help to achieve this. Students may require particular support at times of transition, for example when they enter medical school or when they move to a clinical environment.

Assessor of student progress

Once a student is admitted to a medical school, the teacher has a responsibility to work with the student and to ensure that the student achieves the required learning outcomes. Students’ progression through the curriculum should be monitored and assistance given as required. This role is reflected in the assessment-to-a-standard approach described in the UK case study. The teacher can be seen as a diagnostician, identifying any problems related to students’ progress and guiding their studies to meet their individual needs, with the provision of feedback as required. Students in difficulty may require remedial teaching while those who have mastered a topic may benefit from guidance as to how they might explore the areas at a more advanced level – smoothing the pebbles and polishing the diamonds. At the same time, students should be encouraged to assess their own competence across the different domains.

Assessment of students by the teacher also has the important function of certifying when students are capable of moving on to the next part of the course and, upon completion of the course, practising as a doctor under supervision.

Curriculum planner

The development of an authentic curriculum that mirrors the mission of the medical school and relates to the needs of the community is an important task for the medical teacher. The students admitted to study medicine in the medical school and the teachers and resources available should be taken into account in the planning of the curriculum. Curriculum planning should be done in collaboration with the range of stakeholders, including teachers from the different disciplines, other healthcare professions and representatives of postgraduate programmes. Patients can also have a useful input and students should be represented on the curriculum committee. The committee should determine the expected learning outcomes and the most appropriate sequence of courses to achieve these. Decisions need to be taken about the educational strategies and the approaches to be adopted to teaching and learning. Consideration should also be given to the student assessment as an integral part of the education programme. A grid should be prepared relating the learning outcomes to the courses and assessment.

The curriculum should be built on sound education principles, including the need to encourage students to reflect and to engage in active learning. As far as possible, the curriculum should be designed to meet the different needs of the individual students.

Manager and change agent

Many management decisions at a university or medical school remain top-down with regard to strategic planning, budgeting, staff appraisals and quality assurance processes. Quality and efficiency are seen as management objectives. In general there has been a move to wider participation in management decisions and to greater flexibility, accountability and responsiveness to the needs of students. As a stakeholder, the teacher cannot afford to be disengaged from the decision-making processes within the institution. At an individual level, the teacher also has management responsibilities. These will vary with teaching responsibilities and may range from responsibility for management of a small part of the learning programme to responsibility for a module, a course or a phase of the curriculum. In terms of learning experiences, teachers are responsible for managing their own personal teaching session, which may be a lecture, a small-group activity, a clinical experience or a practical or clinical skills laboratory. Whatever the level of responsibility, the teacher will have four specific functions to perform as a manager: planning, organising, implementing and monitoring. This will require time management, delegating, communicating, team working, negotiating and conflict resolution.

We can’t expect the future to be the same as the past. Significant changes are taking place in medical education in terms of curriculum planning, teaching and learning methods and assessment. Effective management is essential if we are to respond to change, whether the change arises from the internal rearrangement of functions or personnel or from external factors. Without sound management, change may result in low morale and poor end results. Potential obstacles to change must be identified and tackled. These may include a conservatism, rigidity and reluctance to change; a failure to recognise the need for change; a clear vision of the change proposed; a possible increase in staff workload and lack of resources; and a lack of an incentive to change.

The teacher as a researcher

The teacher is a professional and not just a technician delivering an education programme. With this is a responsibility to contribute to advancing the field of education, identifying what works and what doesn’t work in the teaching programme and exploring ways of improving the learning experience for students. Medical education is enriched when teachers take this broader view of their role.

Teachers should be not just consumers of research, but producers of research – a move from education research for teachers to education research by teachers, from teachers as researched to the teacher as the researcher. Such practice-related or action research is an important contribution that can be made by all teachers to research in education. As a result, the teacher is empowered and the role of the teacher as a stakeholder in change is recognised. Teachers may work on their own, critically appraising and improving teaching practice, perhaps supported by staff with education research experience or as part of a larger research team with external funding.

By accepting a role as researcher, teachers can improve their own teaching practice; they can learn from their experience and a rich insight into key educational issues can be gained. The teacher as a researcher is consistent with the professionalism and scholarship of teaching and is simply an extension of what was seen as the traditional role of the teacher, not a change to the role.

The teacher as a course evaluator

As a professional, teachers have a responsibility to evaluate the courses or learning experiences for which they are responsible. The information gained is used to make decisions about the value and/or worth of an education programme. One approach to curriculum evaluation in common use is Kirkpatrick’s four-level evaluation model (Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick 2006). Outcomes assessed are:

1 learning satisfaction or reaction to the programme;

2 learning attributed to the programme;

3 changes in the learner’s behaviour by application of the knowledge to practice;

4 the impact of the programme on patient outcomes.

This model of evaluation on its own, however, does not illuminate why a programme works or doesn’t work. The ten issues relating to a curriculum described by Harden and Laidlaw (2012) need to be examined if further insight is to be obtained. Other curriculum evaluation models include the logic model and the CIPP (context, input, process and product) model (Frye and Hemmer 2012).

The teacher as a professional

As professionals, teachers have a responsibility to ensure they have the necessary skills and abilities to fulfil the roles described above. Proficiency in the tasks required can be acquired through participation in staff development programmes or from following the example of more experienced teachers. Teachers have a responsibility to enquire into their own competence as a teacher and to keep themselves up to date with developments in education and how these might impact on their teaching. This can be achieved through reading medical education journals, through participation in education conferences or networking with teachers with a similar interest.

Take-home messages

• Curriculum planning should be considered in the context of the vision or mission of the medical school, the specified learning outcomes, the courses in the education programme and their sequence, the content addressed, the education strategies, the teaching and learning methods, the assessment approaches, the educational environment, communication about the curriculum to staff and students and the education management.

• Increasing attention is being paid to the need for an authentic curriculum where the focus is on equipping graduates with the competence to work as a member of a team and to practise medicine as a doctor.

• Curriculum planning and delivery should be a collaborative activity involving all of the stakeholders. It should include interdisciplinary and interprofessional education, collaboration between those responsible for the different phases of undergraduate, postgraduate and continuing education, and collaboration with other schools locally, nationally and internationally.

• A feature of a curriculum should be student engagement in curriculum planning and in delivery of the teaching programme. Students can also be engaged in the school’s research programme and in representing the school nationally and internationally at medical education conferences.

• The success of a curriculum will depend on the teachers. Roles for the teacher include information provider, role model, facilitator of learning, assessor of students’ progress, curriculum planner, education manager, researcher and course evaluator.

Bibliography

Apoyo ConsultorÍa (2005). Estudio del mercado de formación de médicos y su futura demanda laboral, Lima: Apoyo ConsultorÍa.

ASPIRE (2014). Online. Available HTTP: http:www.aspire-to-excellence.org (accessed 8 September 2014).

Bandaranayake, R. (2011) The integrated medical curriculum, London: Radcliffe Publishing.

Cruess, S.R., Cruess, R.L. and Steinert, Y. (2008) ‘Role modelling – making the most of a powerful teaching strategy’, British Medical Journal, 336(7646): 718–21.

Frambach, J., Manuel, B., Fumo, A., Van der Vleuten, C. and Driessen, E. (2014) ‘Students’ and junior doctors’ preparedness for the reality of practice in sub-Saharan Africa’, Medical Teacher, 37: 64–73.

Frenk, J., Chen, L., Bhutta, Z.Z., Cohen, J., Crisp, N., Evans, T., Fineberg, H., Garcia, P., Ke, Y., Kelley, P., Kistansamy, B., Meleis, A., Naylor, D., Pablos-Mendez, A., Reddy, S., Scrimshaw, S., Sepulveda, J., Serwadda, D. and Zurayk, H. (2010) ‘Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world’, The Lancet, 376(9756): 1923–58.

Frye, A.W. and Hemmer, P.A. (2012) ‘Program evaluation models and related theories. AMEE guide 67’, Medical Teacher, 34(5): e288–99.

General Medical Council (2009) Tomorrow’s doctors: Outcomes and standards for undergraduate medical education, London: GMC. Online. Available HTTP: www.gmc-uk.org/New_Doctor09_FINAL.pdf_27493417.pdf_39279971.pdf (accessed 10 June 2014).

Harden, R.M. (2000) ‘The integration ladder: A tool for curriculum planning and evaluation’, Medical Education, 34(7): 551–7.

Harden, R.M. and Laidlaw, J.M. (2012) Essential skills for a medical teacher: An introduction to teaching and learning in medicine, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier Publishing.

Harden, R.M., Crosby, J., Davis, M.H., Howie, P.E. and Struthers, A.D. (2000) ‘Task-based learning: The answer to integration and problem-based learning in the clinical years’, Medical Education, 34(5): 391–7.

Kirkpatrick, D. and Kirkpatrick, J. (2006) Evaluating training programs: The four levels (3rd edn), San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Schwarz, M.R. and Wojtczak, A. (2002) ‘Global minimum essential requirements: A road towards competence-oriented medical education’, Medical Teacher, 23(2): 125–9.

Sub-Saharan African Medical Schools Study (SAMSS) (2009) Site visit report: Faculty of Medicine, Catholic University of Mozambique, Washington, DC: SAMSS.

Tosteson, D.C. (1979) ‘Learning in medicine’, New England Journal of Medicine, 301(13): 690–4.

World Health Organization (2012) Mozambique: Health profile. Online. Available HTTP: http://www.who.int/gho/countries/moz.pdf (accessed 8 September 2014).