This Springer imprint is published by the registered company Springer Science+Business Media B.V. part of Springer Nature.

The registered company address is: Van Godewijckstraat 30, 3311 GX Dordrecht, The Netherlands

This book provides an excellent framework for managers to pursue sustainable business in a strategic way. At the same time, it is a learning model, starting with the foundations of risk management and stakeholder management and moving on to the more complex challenges of strategic differentiation and business model innovation. The most challenging part however is the organizational change management and talent development which needs to follow or go hand in hand with the strategic processes.

The wealth of case studies and supporting texts is derived from the legacy of ABIS – The Academy of Business in Society where business schools and companies are working together to enhance the knowledge base for sustainable business. The book follows the rationale of the business manager in a very practical manner, and I hope it will be widely used in executive education and become a core part of learning and talent development.

Before I joined Solvay S.A., I was the CEO of a pharmaceutical company, the chairman of the Belgian Employers Association and one of the hundred founders of the Club of Rome in 1968. I was convinced of the necessity of sustainability whether environmental, social or ethical.

During my stay at the helm of Solvay S.A. (1984–2006), our global company became even more global and even more conscious of the rising global sustainability challenges. As a 150-year-old family-controlled company, we understood very well what sustainability meant. My management colleagues and I, with the support of my family shareholders, decided increasingly to take strategic decisions and operational execution only when we could grow profitably in a sustainable way, with due respect for environmental, social and ethical issues. With these principles in mind, we have reorganized some businesses, we have sold businesses where we could no longer see profitable growth with sustainability, and we have acquired businesses where we could see growth with sustainable profitability.

This book offers managers a systematic approach for pursuing sustainable profitability by integrating economic, social, environmental and ethical dimensions in business strategy and decision-making. As a member of the INSEAD Advisory Council, I have argued for a long time that the future of capitalism is in peril if – despite its global and remarkable successes – business cannot control and minimize its failures and excesses (greed, inequality, corruption, climate change, social injustice, etc.). The solution must be a more sustainable market economy. I am convinced that businesses, when profitable, sustainable and innovative, are a force for good, for a better world. I think therefore that the business schools curriculum should address the sustainability challenges in serious ways. I am very happy to see that this book offers a down-to-earth framework for making this happen. I congratulate the editors and the authors for their unique contribution to business education.

In this chapter, we are presenting an outline of the conceptual framework for this book. This framework is also a step-by-step model for managers to identify risks and opportunities for sustainable business and therefore also a managerial framework for decision making, as well as a supervisory framework for the board.

As set out in the introductory chapter, the key to sustainable business is in achieving the right balance between managing competitiveness and profitability for attractive returns to shareholders with managing the political, social and ecological context of the business which in turn can enhance competitiveness and profitability. Managing the context of the business is focused on both protecting value against sustainability risks and creating new value from sustainability opportunities. In managing context, the business is perceived as generating benefits for all stakeholders (including its shareholders) and as a credible and trustworthy player for these stakeholders.

- 1.

Risk Management focusses on the “accountabilities” of the business and consists of knowledge management of “inside-out” impacts of the business model and the business strategy. Risk management is about managing accountabilities for impacts (externalities) in shifting social contract environments. Oil companies like Shell and BP are held accountable for all environmental impacts, even if they operate within the law and governmental regulation (Shell) or if the impacts have been caused by a subcontractor (BP).

- 2.

Issues Management focusses on the more vague “responsibilities” of the business and consists of knowledge management of “outside-in” impacts of new issues from the business environment on the business. Issues management is about adopting appropriate organisational responses for latent, emerging and maturing issues of responsibility. In the face of controversy on child labour, Nike had to shift from a defensive and compliance approach to a strategic approach by changing its business model and seeking industry sector agreements as the child labour issue matured over the years.

- 3.

Stakeholder Management for Competitiveness and Trust is about identifying, weighing the importance and prioritisation of key stakeholders within the business model and managing relationships with stakeholders as key resources for comparative strategic advantage. Companies like Johnson & Johnson invest continuously in relations with key stakeholders such as hospital managers and health care staff.

- 4.

Strategic Differentiation: Strategic Bets for Sustainable Business Development is about developing sustainability value propositions to markets and stakeholders, including reconceiving products and services, redefining productivity in the value chain and developing partnerships. GE Healthcare high efficiency CT systems are designed to reduce electricity consumption for operation and ambient cooling by optimising energy use based on a customer’s usage profile. Illycaffè redefined productivity in the value chain by engaging directly with farmers to ensure high-quality supplies combined with a better income for farmers. GSK formed partnerships with NGOs to ensure that medicines would find their way to patients instead of disappearing into corrupt reselling channels.

- 5.

Business Model Innovations and Transformations: Taking Great Leaps Forward is about identifying and entering market spaces with high sustainable value and transforming business models and capabilities to capitalise on emerging market value. Umicore reinvented itself from a polluting steel giant into a specialty metals and materials producer and technology solutions for sustainable development. IBM radically changed its business model from a hardware producer of PCs and servers to a provider of IT-driven solutions for sustainable development in, for example, electricity grid efficiency and traffic management.

- 6.

Managing Change for Sustainable Business: Developing Dynamic Capabilities is about developing organisational capabilities and managerial talent for sustainable business and leadership for organisational change. All the above cited examples of innovative companies display a dynamic capability for turning sustainability threats into opportunities. Unilever does so in an exemplary way with its Sustainable Living Plan and is completely redesigning HR and talent development processes to support its strategic ambition of doubling sales and halving environmental impact.

We will now elaborate on this model by providing the conceptual background and analysis for each of these six dimensons of managing sustainable business.

Part I Risk Management: Managing the Accountabilities of the Business

This first level of analysis deals with the accountabilities for inside-out impacts (or “externalities”) of the company on its ecological, social and governance/political environment (ESG). Most companies have considerable positive impacts in terms of technological development, quality products and services, employment, tax contributions, training of the workforce (which contributes to its employability), community support, philanthropic activities and more. However, within the context of managing the company’s accountabilities, it is important to manage the risks associated with negative impacts , i.e. costs which are externalised and from which the company profits but the price to be paid in extreme cases might be prohibitive.

Negative impacts may be oil spills, air and water pollution (environment), poor and unsafe working conditions, human rights violations (social), corruption, entanglements in civil wars and complicity with governments which do not respect human rights or free speech (governance). However, a business will always have externalities, some with acceptable costs for society. How much costs are acceptable to society is very much dependent on the normative context of the company often described as the “social contract” a company operates with.

A “social contract” in this context of sustainable business refers to the normative framework the business operates with, which is determined by the expectations of society and government on the role and purpose of business 1 . These expectations go well beyond fulfilling legal and regulatory obligations by business.

The normative framework consists of both explicit and implicit expectations of governments and societies (often voiced via non-governmental organisations).

In our model, risk management deals with management of impacts within the context of the social contract of explicit expectations.

The informal, implicit and frontier expectations of the social contract are the subject of issues management. These so-called norms consist of the explicit and implicit expectations of governments and societies (often voiced via non-governmental organisations). In our model, risk management deals with management of impacts within the context of the social contract of explicit expectations. The informal, implicit and frontier expectations of the social contract are the subject of issues management .

Explicit expectations in relation to impact management can be legal or extralegal. Legal standards on social, environmental and financial accountabilities are provided by legislations of governments, directives of supranational bodies like the EU or supranational institutions like the WTO. Extralegal explicit expectations are shaped by guidelines from organisations like OECD, ILO, UNEP and UN Global Compact, covenants with governments or even strong demands from credible NGOs supported by public opinion.

Explicit expectations might vary from country to country and between continents, but with the emergence of the “global village”, corporate activities which are in line with explicit expectations in one part of the world may be judged by the court of global public opinion and media from another more stringent set of criteria.

Risks are mostly inherent in the externalities of the business model and the business strategy and thus are at the heart of the company’s existence. These exposures of the business model and business strategy can be life-threatening to any business.

Identifying negative impacts against the background of explicit expectations

Understanding the liabilities and possible consequences (financial and reputational)

Setting and continuously updating standards

Managing compliance, assurance and control processes

Crisis and response management (despite all of the above, something can/will go wrong)

Communications management, transparency and media management

The value proposition, i.e. the value created for customers (price, quality, service)

The market segment and types of customers (sensitivity, political)

The structure and span of the value chain from suppliers to customers

The revenue-generating processes and systems (pricing, margin setting, exploitation of quasi-monopolistic positions)

The position of the business in the value network or the “ecosystem” it forms part of, i.e. the vertically and horizontally extended value chain and relevant stakeholders

Consequently business models with different foci have different risks. For example, business models based on low cost and price leadership (e.g. Walmart, McDonald’s and FedEx) are vulnerable in different ways compared to business models based on product leadership (e.g. Apple, Fidelity Investments, BMW and Pfizer), where the brand value is more at stake. Also different strategies have specific risks: Geographical expansion and new market development, for example, maybe risky, since companies start operating in new territories with unknown complexities in the social contract fabric and the political context, e.g. BP in Columbia, Google in China, Walmart in Mexico, Shell in Russia and GSK in South Africa.

Manifest risks can be analysed in terms of their type (like environmental, social, governance/political risks) and the degree which can be evaluated in a matrix of control and repercussions. The areas of risks are defined by the spans of vertical and horizontal integration in the value chains and may be located in the supply chain, in the distribution chain (including product liabilities), in production facilities, in joint ventures, in mergers and acquisitions (hence importance of ESG due diligence) and in geographic and associated cultural risks in new markets.

Negative effects may be a combination of financial losses through costs, fines, litigation, share price erosion, market share losses, damage to reputation which increases transaction costs, diminished brand value which depresses margins and thus profitability, valuable management time spent on managing crises and the aftermaths instead of growing the business.

Managerial risks like a too narrow short-term focus, ignorance of context of business, underestimating inherent risks in the business model and business strategies, legalism and defensiveness (or lack of proactive attitude) of management

Organisational risks in organisational culture and structure, processes, systems and skills, top management driving challenging targets “whatever the costs” and middle management taking unsustainable pathways (e.g. Volkswagen emissions scandal)

Corporate governance risks caused by boards not sufficiently overseeing a broad spectrum of risks in the business and the context of business and boards not questioning basic assumptions in business models and strategies and not critically questioning risk/return imbalances

Boards should be closely involved in overseeing risk management beyond the traditional concerns of financial and technical risks. This is not in the least because regulatory risks (governments imposing new legislation with costs of administration for companies and which might, in addition, not be effective) need to be mitigated by substantial voluntary industry sector-wide standards and practices. In order to achieve this, companies may want to assume industry sector leadership and/or establish market entry barriers for low-quality unsustainable operators. This may be tricky.

A newly emerging dimension of risk management is the growing integration of sustainability risks into equity research by asset managers and fund managers and the potential of future share value being risk adjusted accordingly. Boards should be alert to this new trend. (See the introduction in Chap. 2 ).

Example for risk management | ||

VIGEO CSR Risk Management Framework | ||

Business model risk areas | Standards against which impacts should be measured | Origins of explicit expectations |

Human rights | 4 | |

Human resources | 5 | OECD |

Environment | 6 | UN |

Business behaviour | 3 | ILO |

Community relations | 3 | UNEP |

Corporate governance | 2 | Global Compact |

Human rights risks : prevention of violations, freedom of association, non-discrimination and child labour/forced labour

Human resources risks : labour relations, employee participation, restructurings, career management and employability, remuneration systems, safety and respect for working hours

Environmental risks : ecodesign, pollution, green products, biodiversity, water resources, impacts of energy use, atmospheric emissions, waste management, environmental nuisances, impacts of transport and product disposals

Risks related to business behaviour : product safety, customer info, contractual agreements, environmental and social factors in supply chains, corruption and anticompetitive practices

Community relations risks : socio-economic development, social impacts of products and contribution to good causes

Corporate governance risks : board performance, audits/internal controls, shareholder rights and executive remuneration

Part II Issues Management: Managing the “Responsibilities” of the Business

The second element of the model is an outside-in investigation of major trends in the immediate and wider business environment which may affect the business in the medium to long term. These trends produce issues that exacerbate risks in the business model and the business strategy or create new risks, thereby affecting the sustainability of the business model and strategy.

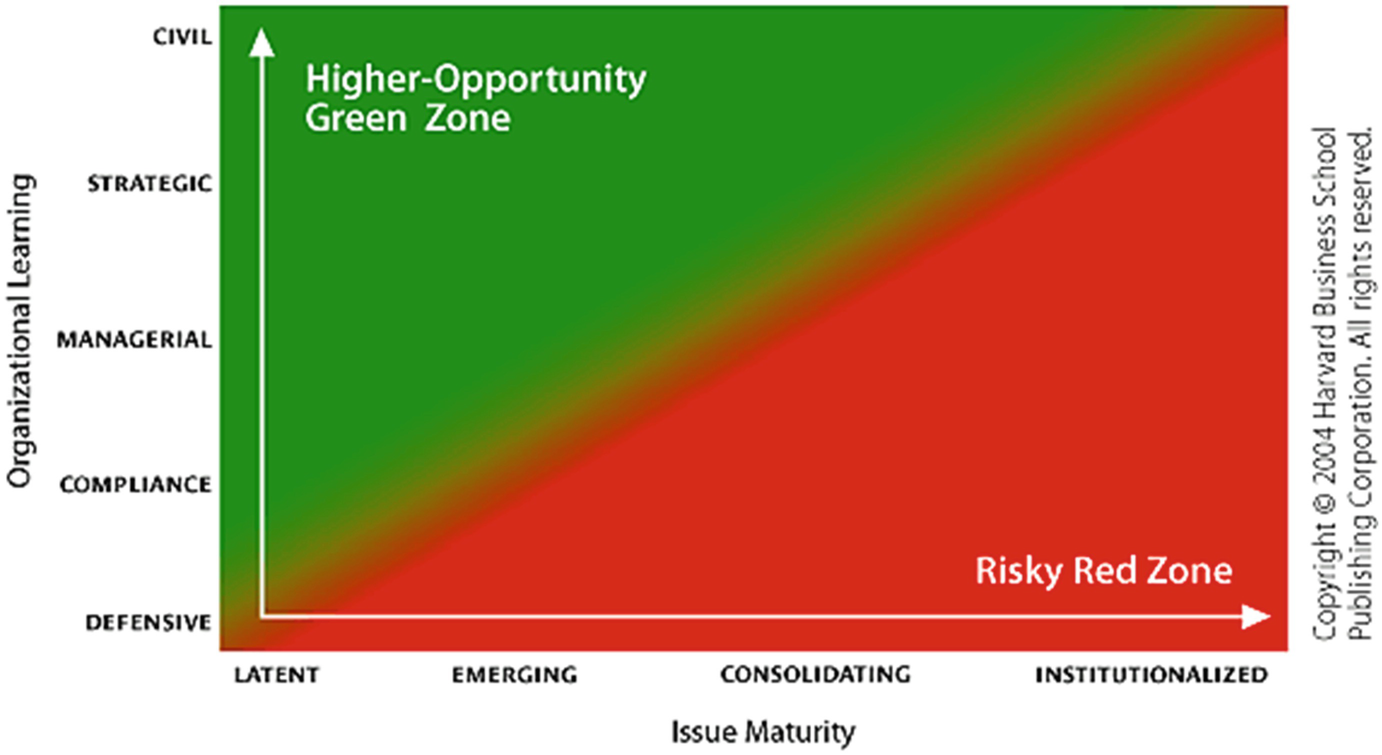

Issues management is concerned with the less formal, more implicit or even frontier expectations within social contracts . Issues management is therefore more fluid, much less predictable and more a matter of connectedness and feeling for context, judgement and opportunity assessment than straightforward analysis, standard setting and compliance management.

Major current issues such as a culture of systematic corruption, inequality, poverty, privacy, obesity, offshoring, access to medicines, resource depletion, forest destruction and climate change were not long ago widely considered to be part of the responsibilities of governments and regulators and not the responsibility of business . As these issues over time emerged, matured and became publicly associated with corporate responsibility, they have shifted an industry’s ground rules and pose serious threats to the sustainability of the business.

However, these issues can create new market opportunities that nimble companies can identify and exploit for comparative advantage. Of course, there are first-mover business risks involved in incorporating emerging issues very early on in business models and strategies ahead of the competition, such as cost disadvantages. Thus, companies with a business model based on cost leadership and standardisation will be less keen. However, agile companies will nevertheless consider simultaneously the risks associated with lagging behind and becoming an icon of corporate irresponsibility and greed. Industry leaders are especially prone to becoming these icons.

Issues management deals with the continuously shifting grounds of what is perceived as the responsibilities of business by public opinion at large and specific stakeholders in particular. Issues management deals with the informal, implicit and frontier expectations of the social contract.

If issues are latent, like obesity or water depletion 15 years ago, a defensive attitude (“business cannot solve these problems, governments should”) may not be damaging but alertness to the shifting grounds of perception may be necessary nevertheless. As issues emerge, positions need to be taken deliberately and managerial action is often required. At this stage, CSR departments are often tasked with compliance management, but this may not be sufficient. As Zadek describes in the Nike case, the issue of child labour was a type of collateral damage, an indirect effect of the business model, based on just in time supply policies and the remuneration policies for procurement staff. Imposing standards on suppliers by compliance officers sent by the CSR department was to no avail at first. Instead, the business model needed to be adapted. Corruption was long considered an unavoidable part of doing business, especially in developing markets. Corruption remains a challenging issue for companies and requires more than compliance management. Companies like Siemens learned the hard way that corrupt practices can be implicitly part of the business culture and business strategy and a significant overhaul of both is often required.

Issues might be linked to industry structures or even global trade conditions and again require much more exhaustive analysis and deliberate strategic action than compliance management by CSR departments. They require immediate and strong involvement of senior management and the board. In Nike’s case, a global trade agreement within the WTO provided for supply quota per country in the global apparel industry. This well-intended policy (equal access to world markets) had however unintended side effects which indirectly allowed child labour to persist. Companies like Nike had thousands of suppliers from many countries and found it impossible to control standards in the supply chain and concentrate on quality relations with fewer suppliers. Cooperation between the industry sector and the WTO was required to adapt trade agreements and avoid unintended consequences. Nike assumed industry leadership to help significantly in making this happen.

Companies like Walmart, McDonald’s and Lidl enjoy low-cost supply conditions but have low margins in sales and distribution. Apparel brands such as Nike have of course a much more profitable business model, which is based on low cost in the supply chain and high margins in the sales and distribution chain. Returns, certainly without any investment in manufacturing and other assets, can be extraordinary. However, the rule often holds that considerably higher returns bear significant risks.

Many more companies, such as Apple, source from low-cost countries and sell at high brand premiums in developed markets. But such business models become threatened over time from both ends by emerging issues: the cost basis on the supply end and the brand damage which may erode margins at the distribution and marketing end.

The emerging and maturing issues of today are without a doubt climate change (especially since the COP21 Summit in December 2015) and environmental footprints in general, along with related issues such as erosion of water reserves, emissions testing and performance of automobiles. But other issues are also seemingly maturing, like inequality in general, access to medicines, corporate tax avoidance and tax competition between countries from which companies benefit, fugitives and migration and programmed obsolescence of electrical and electronic products. Executives might be tempted to be dismissive of corporate responsibility in these or only accept a small part of responsibility, but the bets are out on how long this defensive attitude can last and when it results in a “too little, too late” blame in the medium term or even short term.

Part III Stakeholder Management: Managing Competitiveness and Trust

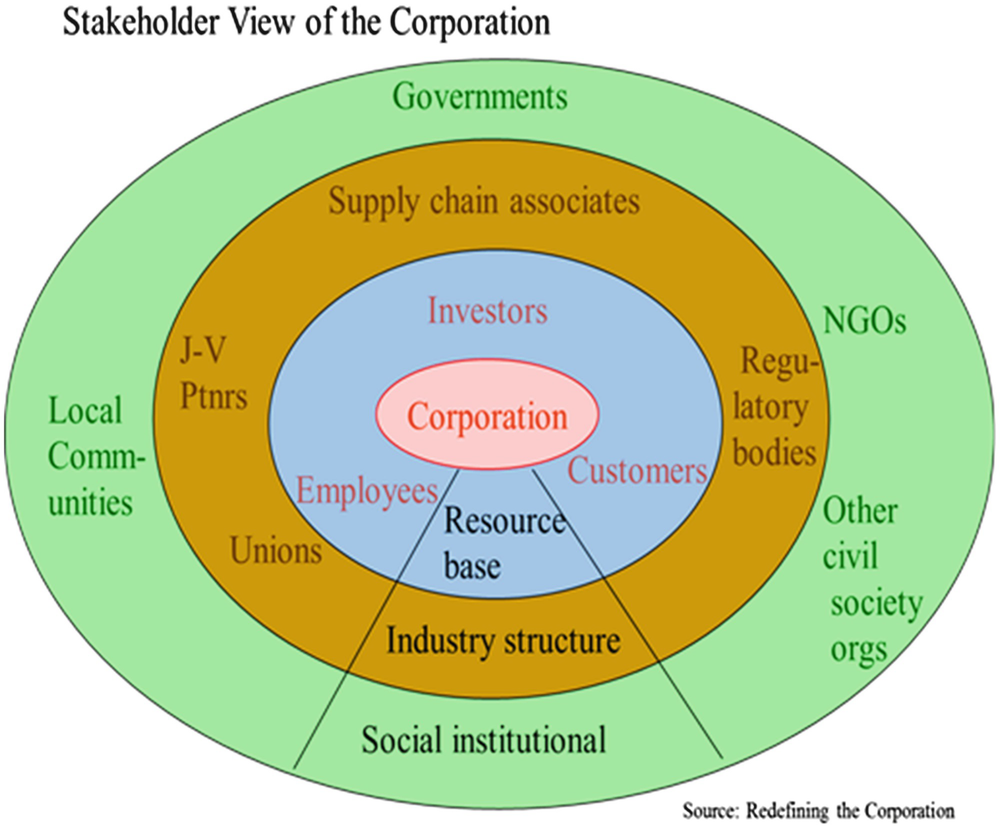

Business stakeholders are affected by the business while they also have an effect on it. The stakeholder view of the corporation allows for a clear view on all those groups and organisations with which the business is interdependent and which need to be closely monitored during management processes to provide checks and balances. The stakeholder view we introduce here is not opposed to a “shareholder view”. Shareholders, investors at large, are also stakeholders themselves, albeit that they exert considerable powers via the financial markets and based on corporate law. But the considerable powers of other stakeholders work in different ways, often indirect and on different timescales. Moreover, stakeholders may be perceived as pulling the business in different directions, maybe ultimately tearing it apart and destroying it. The task of management is to counteract the competing forces around common purpose and common interest . At times, trade-offs and compromises need to be made, but more value can be created by finding new innovative solutions, new creative approaches that can go beyond pedestrian compromise.

Resource base stakeholders such as investors, customers and employees.

Industry structure stakeholders such as suppliers, unions, joint venture partners and regulatory bodies. Even competitors can be seen as part of this group of stakeholders.

Social-institutional stakeholders such as governments, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), other civil society organisations and local communities.

The media including the press, TV, radio, Internet and social networks are giving voice to stakeholders but act sometimes as stakeholders in their own right. However, stakeholders can be sources of both risk and opportunity . A stakeholder management model of the business should distinguish between risk and opportunities with each stakeholder and manage these accordingly. Stakeholder management creates firm value by minimising risk and maximising opportunity in relationships with stakeholders.

Risks and opportunities provided by stakeholders may vary, and accordingly, different weightings of stakeholders should be undertaken . In knowledge-based industries, human resources carry more risks and opportunities compared to physical asset-based companies like oil companies, who in turn need to attach more risks to environmental activists and regulators. All stakeholders are important, but some more than others, depending on the industry sector and the specific business model and business strategy of the company.

Source: John Elkington, unpublished

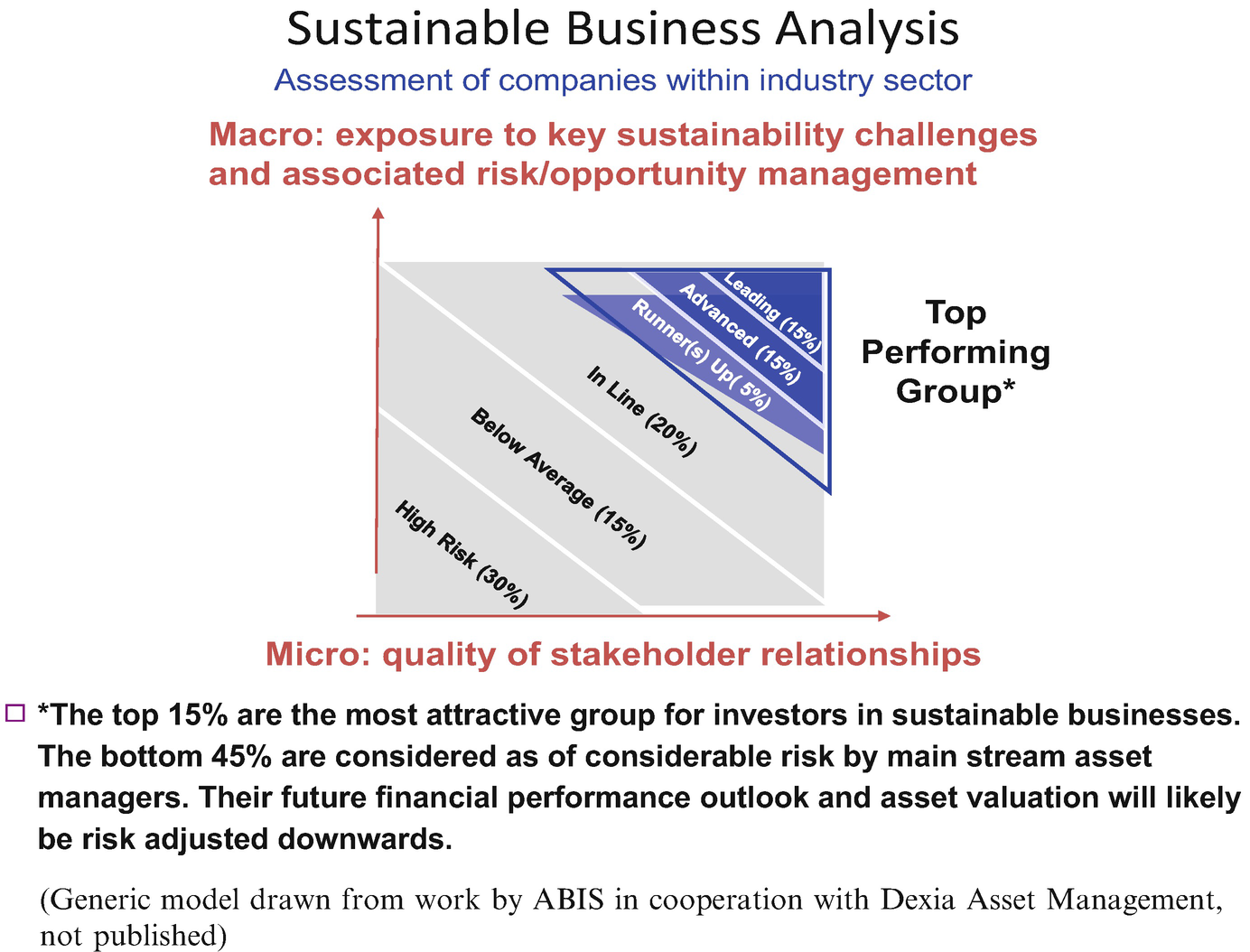

In sum, stakeholder management is a vital part of managing a sustainable business. This is also recognised by sustainable asset managers and, increasingly, mainstream asset and fund managers in the financial services industry, who evaluate each company on risks and opportunities both in the business exposure to sustainability trends and in stakeholder relationships. This is commercially sensitive information which is not published. But the authors of this chapter have been deeply involved in the development of such assessment models for asset management firms. In these models, the quality of stakeholder relationships is an important part of the assessment and makes up for 50% of the assessment rating.

(Generic model drawn from work by ABIS in cooperation with Dexia Asset Management, not published)

Stakeholder management provides the method and channels for encompassing Risk Management (Part I) and Issues Management (Part II) . Risks and issues are better managed with a smart and credible stakeholder strategy and implementation.

Leading companies like Johnson & Johnson, Novartis, Orange, IKEA, BMW and many more have implemented stakeholder-based business principles. These companies define risks and opportunities with each stakeholder and develop and evaluate key performance indicators and expectations from relationships with each stakeholder. They consistently build knowledge resources and social capital. They are keenly aware of risks from impacts/externalities and of emerging issues and proactively manage these with stakeholders. Stakeholder management becomes in this way the management model of the business.

The financial pre-occupation of many companies have rather eroded, not enhanced competitive advantage. It diverts management attention from sustainable value creation. The Shareholder Model, solely focussed on profit maximisation and share performance, is typically not successful, even on its own terms and has undermined the legitimacy and stability of the market economy. It will end up destroying the very shareholder value it proclaims to defend and grow. 2

And so, unfortunately, it happened as predicted by John Kay with companies like Daimler Benz, Marks & Spencer, Vodafone and others. Shareholders, customers, staff, suppliers and other stakeholders paid dearly for the aberration Kay denounced in a radical way as “unfit for wealth creation in free markets”. It took these companies often more than a decade to turn themselves around with new management, renewed business purpose and renewed attention to value creation with stakeholders and ultimately for shareholders.

Part IV Strategic Differentiation: Creating Comparative Advantage

A seminal contribution in strategy was Michael E. Porter’s five forces model (1980) which profoundly influenced the thinking of researchers and practitioners in business strategy around the world since the 1980s. In essence, Porter argued from a rather external, industry-based perspective that the goal of the strategist is to understand and cope not only with competition but with customers, suppliers, potential entrants and, inevitably, also substitute products. These five forces define an industry’s structure and shape the nature of competitive interaction within any industry sector.

Originally Porter was sceptical about social issues affecting business, but he started to integrate the idea of sustainable business in his strategy model, recognising that ESG issues form part of the competitive context in the medium and long term. His concept of shared value is the vehicle for this, which was first published with Mark Kramer in the Harvard Business Review in 2006. In this book, we republished the subsequent publication in 2011, again with Mark Kramer, which expands further on their core thesis of CSV (creating shared value): that businesses can create economic value and value for society in mutually beneficial ways, that this creates comparative advantage for the business and that the value for stakeholders and society is more sustainable since it is underpinned with economic fundamentals.

In an interview in 2013 with Gerard Baker, editor-in-chief of the Wall Street Journal 3 , Porter famously made a plea “to open our thinking for creating economic value by addressing social issues”. He compared what companies like Nestlé and Illycaffè are doing as examples of CSV with the fair trade approach, which is for Porter an example of CSR. Fair trade asks for a contribution from consumers in order for coffee farmers to be paid a fair price for their crops. This is aimed at the ethical consumer segment which is limited in size and volatile when consumer priorities change. Instead, Illy pioneered a restructuring of the supply chain by cutting costs and investing in the skills and knowledge of farmers to produce higher-quality coffee (see Illy case study in this book). As a result, the farmers’ income went up considerably and this was based on economic fundamentals, whereas in the case of fair trade, it was dependent on the goodwill of consumers. At the same time, Illy strengthened its competitive advantage by ensuring access to high-quality supplies in a sustainable way.

- 1.

Reconceiving products and services to better meet social and environmental needs in a profitable way

- 2.

Redefining productivity in the value chain to make more efficient and more sustainable use of human and material resources, both in the supply and distribution chain

- 3.

Local cluster development

They also strive for forming partnerships including NGOs who become partners instead of adversaries. Local NGOs are often very well placed to take over certain roles in the value chain, e.g. ensuring that medicines, provided by pharmaceutical companies at discount prices, find their way to the patients instead of into the black market.

Despite some irrefutable examples of companies, across many industries, benefitting from implementing shared value strategies, there still remain some lingering “yes, but” cautionary sentiments. Some fear that the consequences of shared value practices have not been fully explored and all the implications might not have been fully considered.

Furthermore, stakeholder pressure may force companies to become a more sustainable business, but it does not necessarily follow that the company or its marketplace will actually become more sustainable. An example is Hydro Polymers Limited, a division of Norsk Hydro ASA, which dramatically changed its strategy due to outside pressure from Greenpeace activists. However, the rest of the industry questioned Hydro Polymers’ motivation to commit to a more sustainable solution. Moreover, China had become a major producer PVC often using environmentally unfriendly technologies. Chinese PVC is, not surprisingly, much cheaper. If European regulators do not prohibit the importation of “Made in China PVC”, the question remains whether the end users will demand a shared value with a more sustainable solution such as offered by Hydro Polymers or prefer to purchase the Chinese PVC at the lower price.

The Value of “Creating Shared Value” Contested

- 1.

Porter and Kramer claim that the CSV concept is a novelty while at the same time it bears similarity to existing concepts of CSR, stakeholder management and social innovation .

Porter and Kramer integrate some dimensions of these concepts indeed but package them in a model and a language which is understood by managers. More importantly, they do not start from societal issues and how companies should be held “responsible”, which results in CSR programmes. Porter follows an entirely different logic: he asks how corporate strategy can embrace ESG issues to make the business more sustainable. He sees ESG issues as strategic opportunities for the business and not as normative imperatives.

- 2.

Many corporate decisions that are related to social and environmental problems do not present themselves as potential win-wins but rather as dilemmas. When faced with a dilemma, world views, identities, interests and values collide and Porter doesn’t address the tensions between social and economic goals; instead, he only sees “win-wins”.

But Porter never claimed that all solutions can be “win-wins”. However, he suggests, similarly to Ed Freeman, the founder of stakeholder theory, that when confronted with conflicts between economic and social goals, managers should not complacently seek for compromises and trade-offs or pursue one at the expense of the other. Instead, these conflicts should be seen as potential sources of innovation, delivering solutions that may achieve both economic and social goals. Sustainable business and sustainable economic and social development will require substantial innovations.

- 3.

Furthermore, the examples they provide might be pioneers in some aspects of their operations while, at the same time, being criticised for harmful effects of their products.

The reality is very simply that companies like Nestlé get it right in some areas of their value chain while not in other parts (yet) and should be encouraged indeed to practise continuous improvement. If Nestlé uses Porter (who is a member of the board) and CSV to “greenwash” its more controversial parts of the business, it should be criticised for this. But this does not diminish the value of CSV itself.

- 4.

According to critics, research shows that initiatives with the goal of promoting sustainability for social and environmental gains only survive in economic terms, ensuring longevity of quality supply for the purchasing company over social and environmental needs of consumers or suppliers. There are indeed examples where a CSV initiative proved not sustainable, but to generalise from this is short sighted.

- 5.

Despite the ambitious approach to reshape capitalism, CSV doesn’t address the deep-rooted problems that are at the centre of capitalism’s legitimacy crisis. Porter’s own model of competitive strategy would need to be overturned .

Reforming capitalism is a big subject indeed and the claim that CSV is the panacea to this is indeed an exaggerated claim. The incomplete and unfinished reform and governance of financial markets that induce notorious short-termism seems more important. Business needs to pursue profitability and competitiveness within clear frameworks of fair play, transparency and the rule of law and with a perspective of long-term value creation. CSV alone will not restore the legitimacy of capitalism but it might be a major contribution to it.

Porter and Kramer’s main contribution is to have coined a concept which managers can embrace and which connects with their mindset, more than any other concept on sustainable business. It serves the purpose of advancing the mainstreaming of sustainable business as a concept for business generally and for silencing the diehards of the old school who refuse to accept any important role business can or should play in sustainable development. But of course it is not a panacea. We publish a response to Porter which gives a thoughtful commentary on the importance of a normative motivation for managers to protect the integrity of their actions in applying CSV. (See Chap. 17).

Part V Business Model Innovation and Transformation

Sustainable development with significantly reduced environmental and social impacts is a formidable challenge for business of formidable magnitude, requiring significant transformations in business models and industry structures, sooner for some, later (but inevitable) for others. It will have revolutionising effects comparable to the effects of the consumer revolution of the 1980s and the IT revolution which started at the end of the last century, when all businesses and industry sectors underwent deep transformations. Reports by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD 2010), with membership of over 60 major global firms, outline the challenges to come for the next 20 years. Clearly, as with previous transformations, there will be winners and losers of these developments.

Sustainable business needs to adopt business models that can sustain this transformation, capitalise on it and create competitive edges in the wake of it. This likely requires deep business model innovations.

Operational Excellence by cost leadership, e.g. in oil exploration (Shell, BP), food chains (Mc Donald’s) and retail (Walmart, H&M)

Product-Service Leadership by product development, innovation and branding, e.g. in footwear (Nike), pharmaceutical (Merck, GSK) and ITC (Google, Apple, Microsoft)

Total Customer Solutions by delivering complete solutions by integrated projects, e.g. IBM Smarter Planet, Energy Solutions Companies (EON) and Private Banks (ING)

Operational Excellence by production and distribution of standard cost competitive solar panels

Product-Service Leadership by development, installation and maintenance of technological advanced solar systems or hybrid systems branded for high performance even under weak sunlight conditions

Total Customer Solutions by conceiving and realising customised and co-created energy provisions where no electric grid is available, including extending provisions for health care, schooling and agriculture, generally in partnerships with NGOs

These business models are not necessarily competing with each other. These are different ways of creating, delivering and capturing value in one industry. Similarly, in the IT industry, there are different business models to be found. Apple, Google, IBM, Microsoft and Lenovo not only have different value propositions to their customers. The entire business models behind their propositions are very different.

In addition to innovations in products, services and processes, as discussed in the previous chapter, business can create competitive advantage or avoid erosion of current, often highly profitable market positions by exploring new business models.

IBM realised that its PC business would over time not be able to compete with Chinese market entrants and sold the business to a Chinese newcomer Lenovo at a time when the market value of the PC business was still high. IBM moved up the value chain into a Total Customer Solution value proposition with the Smarter Planet initiative and a business operating model behind it which is significantly different (see Chap. 25 ). IBM thus positions itself in the sustainability transformation with an innovative business model.

BP Solarex was a market leader in the solar industry in 2000. It scaled back its business model to a pure Operational Excellence proposition (manufacturing and distributing solar panels), inspired by the idea of focusing on “core competences”, a fashion already on its way out. Experiments with Total Customer Solutions as described above were halted and abolished. Ten years later, BP was forced to close most manufacturing facilities at high cost in the face of stiff cost competition from China. In 2000, BP would have been able to sell these facilities at considerable market value and move up the value chain. In 2010, it was too late.

The industry sector model: Business model innovation changes the entire industry: Google, IBM and Dell.

The entrepreneurial model: Business model innovation changes the value chain in major ways: Umicore, Illy and IPOed Batteries. In this last case, a move to focus on core competencies in materials development was complemented by creating a network of partnerships and outsourced activities.

The financial model: Business model innovation creates entirely new pricing models: eBay and Apple’s iPod.

- 1.

Which current needs will the business model address—or which new needs will it create?

- 2.

Which innovative activities can create value by meeting these needs?

- 3.

How can these activities be linked in innovative ways?

- 4.

Who will perform which activities and which innovative governance will be needed?

- 5.

How will value be created and delivered for each stakeholder?

- 6.

How can value be co-created by engagement with the communities?

- 7.

Which revenue models will make the business model sustainable?

Business model innovation is neither about minor changes to the business model to capture easy gains in costs and efficiency nor about a compliance-driven adaptation to gradually minimise negative impacts.

Environmental impact

Social impact

Financial innovation

Base of the pyramid

Diverse impact

- (i)

A company’s sustainable value proposition to its customers and all other stakeholders

- (ii)

How it creates and delivers this value

- (iii)

How it captures economic value while maintaining or regenerating natural, social and economic capital beyond its organisational boundaries

Furthermore, they argue that sustainable value for customers and shareholders can only be created by creating value to a broader range of stakeholders. A business is embedded in a stakeholder network and—in spite of the fact that a business model is a market-oriented approach—particularly a business that contributes to sustainable development needs to create value to the whole range of stakeholders and the natural environment, beyond customers and shareholders.

Roome and Louche page 30 (Nigel Roome and Céline Louche, “Journeying Toward Business Models for Sustainability: A Conceptual Model Found Inside the Black Box of Organisational Transformation” in the journal Organization & Environment , Special Issue “Business models for Sustainability: Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Transformation, volume 29 number1 March 2016 (guest editors: Stefan Schaltegger, Erik Hansen and Florian Lüdeke-Freund), Online: http://oae.sagepub.com/content/29/1.toc )

Part VI Managing Change: Developing Dynamic Capabilities and HR Talent

In response to Michael Porter’s external industry structure perspective on strategy, Jay Barney (1991) developed a resource-based view focusing on internal resources. This model criticised the basic assumption behind the industry-based view, i.e. that firms have the same resources or the same access to resources to implement strategies. This assumption ignores the company’s resources heterogeneity, and mobility, as possible sources of competitive advantage. He observed that businesses develop strong competitive positions based on various resources including all assets, capabilities, organisational processes, corporate attributes, information and knowledge that enable the firm to develop and implement strategies which are designed improve its competitiveness.

Porter’s five forces framework, which applied the structure-performance paradigm of industrial organisation economics to strategy, focused on evaluating suppliers, customers and the threat of new entrants and/or substitute products. This framework is still valid to a certain extent, but it does not succeed in revealing the dominant logic of value capture in newer industries and in newer fields like sustainability. This dominant logic is now recognised to be the way businesses develop core resources which are unique, rare and difficult to imitate and by definition take a long time to grow and materialise.

Core resources include knowledge (including manifest and tacit understanding of the dynamics of markets and social contracts), relationships (unique relationships with all stakeholders in the value chain and in the economic, social and political context of the business), capabilities (managerial, HR talent and organisational resources) and purpose (encompasses the basic values and beliefs shared with stakeholders and the distinctive contribution of the business to the wellbeing of stakeholders).

An overarching resource for comparative advantage is called “dynamic capability”. This is the capability of the organisation for purposefully creating, extending and modifying the resource base of the business, by building, integrating and reconfiguring internal and external competences to respond to rapidly changing environments and contexts, not in the least the social, political and environmental context.

Dynamic capabilities are distinct from operational capabilities (which are based on current competencies), and it goes well beyond the popular concept of “core competencies”. The demise of companies like Kodak and Nokia demonstrated the limitations of the latter.

Success of today is the greatest enemy of tomorrow’s success, Peter Drucker is supposed to have said (although the quote cannot be traced). So a key question follows from this: how can executives of currently successful companies change their existing mental models and paradigms to adapt to radical and often disruptive change to come, not in the least in the face of the sustainability transformation.

The main dilemma in the practice of management is to make the best of existing resources yet at the same time grasp the ongoing depreciation of this resource base .

The concept of dynamic capabilities, especially understood in terms of organisational knowledge processes and management culture, is a predominant concept to explain the significant competitive advantages of firms across a wide range of industries like Apple, IBM, BMW and Johnson & Johnson.

Organisations and their staff need the capability and agility to learn quickly and to build strategic knowledge assets and integrate these into business processes. This means effectively developing capacities to sense and shape opportunities and threats, to seize opportunities and to maintain competitiveness through enhancing, combining, protecting and, when necessary, reconfiguring the business intangible and tangible asset base.

“Path dependency” is a term which refers to the natural reliance of organisations and managers to continue thinking and acting in patterns that evolved over time in the history of the business and the industry sector. Path dependency is a particular impediment for managers and organisations in responding to discontinuous ongoing change.

Dynamic capability is an extended paradigm explaining how competitive advantage is gained and held . Firms resorting to resource-based strategy attempt to accumulate valuable technology assets and employ an aggressive intellectual property stance. However, winners in the global marketplace have been firms demonstrating timely responsiveness and rapid and flexible product innovation, along with the management capability to effectively coordinate and redeploy internal and external competences. The sustainability transformation will require a formidable range of dynamic capabilities sizing two aspects. First, it refers to the shifting character of the environment; second, it emphasises the key role of strategic management in appropriately adapting, integrating and reconfiguring internal and external organisational skills, resources and functional competences towards changing environment.

Practical men who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.

Leaving exaggeration aside, the concept of dynamic capabilities challenges managers to question their assumptions, theories, models and beliefs, in other words, their theories in use which fashion and inform their actions. Some executives are still complacent about the formidable challenge of managing sustainable business and sustainable development. They find it difficult to grasp the full and complex picture of business and its context. They are maybe likely to get away with it for some time, but their businesses will inevitably not belong to the winners in the global economy of tomorrow.

The sustainability revolution is unfolding as one of the great transformations in global business and of a much bigger and deeper scale than the consumer revolution or the IT revolution. Since the world has embraced in Paris the idea that a zero carbon emissions economy will be the inevitable goal to be reached sometime this century, rather sooner than later, most certainties, business models, recipes for success and other beaten paths will become redundant. Businesses with the greatest reservoir of dynamic capability will be the winners in the global marketplace by disruptive innovation, radical self-invention and relentless development of new talent.

One of the key questions “what new talent is needed to enhance the dynamic capability of the business for the sustainability transformation?” is still unresolved . Matthew Gitsham (in Chap. 31 ) explores this question through interviews with global CEOs, leading academics and consultants. He has clustered these talents around three poles: talents required related to grasping context, complexity and connectedness. These largely cognitive talents will need to be complemented by some new character traits such as curiosity and ongoing questioning, systems “feeling” and empathy, courageousness in trespassing boundaries and challenging the status quo. This will require a major departure from a CEO culture of potent self-assurance, unquestionable certainty bordering on arrogance, linear pursuit of single-minded goals and defensiveness of extant assumptions.

Participants in EMBA programmes and in programmes of executive education at large form the talent pool from which the leaders will emerge to steer businesses through the sustainability transformation which is unfolding. Their deep immersion into sustainability risk management, issues management, stakeholder management, strategic differentiation with new sustainable value propositions, business model innovation capitalising on sustainability opportunities and fostering dynamic capabilities for sustainable business development is a must if one takes the future seriously.

References and Further Readings

Part I Risk Management

Al-Debei, M.M., and D. Avison. 2010. Developing a unified framework of the business model concept. European Journal of Information Systems 19(3): 359–376.

Anderson, D., and K. Anderson. 2009, Spring. Sustainability risk management. Risk Management and Insurance Review 12(1): 25–38.

IFC International Finance Corporation. Environmental and Social Risk Management (Portal 2012).

Lenssen, J., N. Dentchev, L. Roger. 2014. Sustainability, risk management and governance: Towards an integrative approach. Corporate Governance 14(5): 670–684

Tamara Belefi, Beth Jenkins, and Beth Kyle. 2006. Social risk as strategic risk . Harvard Kennedy School of Governance.

Yilmaz, A. 2010. Reputation risk management and corporate sustainability . Lap Lambert Academic Publishing.

Part II Issues Management

Boutillier, R. 2012. A stakeholder approach to issues management . Business Expert Press.

Health R. and M. Palenclar. 2009. Strategic issues management, organisations and public policy challenges . London: Sage.

Leisinck, P. et al. 2013. Managing social issues: A public values perspective . Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishers.

Renfro, W. 1993. Issues management in strategic planning . Westport: Quorum Books.

Part III Stakeholder Management

Buckup, S. 2012. Building successful partnerships: A production theory of global multi stakeholder collaboration . Springer.

Drucker, P. 1994, April 13. Post-capitalist society . Harper Business; Reprint edition.

Freeman, E. 2010. Strategic management: A stakeholder approach . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Post, J., L. Preston, and S. Sachs. 2004, Mar. Redefining the corporation: Stakeholder management and organizational wealth. Administrative Science Quarterly 49(1): 145–147.

Renn, O. 2014. Stakeholder involvement in risk governance. Ark Group.

Sarkis, J. 2014. Facilitating sustainable innovation through collaboration: A multi-stakeholder perspective . Dordrecht: Springer.

Part IV Strategic Differentiation

Holst, A. 2015. Sustainability value management: Stronger metrics to drive differentiation and growth . Accenture.

Lenssen, G. et al. 2013, August. Strategic innovation for sustainability: A special issue of corporate governance. The International Journal of Business in Society .

Lowitt, E. 2012. The Future of value, how sustainability creates value through competitive differentiation . Wiley.

Lubin, D., and D. Esty. 2010, May. The sustainability imperative (The new mega trend after quality and IT). Harvard Business Review .

O’Toole, J., and D. Vogel. 2011. Two and a half cheers for conscious capitalism. California Management Review 53(3): 60–76.

Orsato, R.J. 2009. Sustainability strategies . London: Palgrave.

Part V Business Model Transformation

AtKisson, A. 2012. The sustainability transformation: How to accelerate positive change in challenging times . Routledge.

Gilden, P. 2011. The great disruption: How the climate crisis will transform the global economy . London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Roome, N. and C. Louche. Journeying toward business models for sustainability: A conceptual model found Inside the Black Box of Organisational Transformation. 29(1):11–35.

Schaltegger S., E. Hansen, and Florian Lüdeke-Freund. 2016. Business models for sustainability: A co-evolutionary analysis of sustainable entrepreneurship, innovation and transformation. Organization & Environment 29(3):264–289.

Sommer, A. 2012. Managing green business model transformation . Berlin: Springer.

Teece, D. 2011. Dynamic capabilities: A guide for managers. Ivey Business Journal .

WBCSD 2010: Vision 2050: The new agenda for business http://www.wbcsd.org/vision2050.aspx

Part VI Dynamic capability and Talent

Barney, J.B. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management , 17. Jg., H. 1, S. 99–120

Benn, S. et al. 2014. Organisational change for corporate sustainability, a guide for leaders and change agents for the future , 3rd edn. London: Routledge.

Edwards, M. 2010. Organisational transformation for sustainability . New York: Routledge.

Lenssen, G. et al. 2009, August. Corporate responsibility and sustainability: Leadership and organisational change, special issue of corporate governance. The International Journal of Business in Society .

Joris-Johann Lenssen

Justification and Objectives of This Book

Over the last 10 years or so, directors of executive education, EMBA and MBA programmes have been seeking to integrate “something about business ethics, CSR or sustainability” into their programmes. While these subjects are usually optional courses in the MBA curriculum, Exec Ed and EMBA programmes increasingly feature mandatory modules in this field.

Clearly market pressures are pushing for a faster integration at the Exec Ed level. We know of many companies exerting pressure in governing bodies of business schools, such that the dean and faculty finally come to terms with the urgent necessity of paying serious attention to the wider responsibilities of the firm, its impacts on society and the environment, its role in countries with weak governance and more.

Craig Smith as the lead editor and myself published Mainstreaming Corporate Responsibility in 2009. It was primarily intended to support professors in strategy, accounting, marketing, economics and operations management—all the core subjects of the MBA curriculum—in integrating ESG (environmental, social, governance) issues into their courses with appropriate texts and cases.

This new book in front of you is addressed primarily at the EMBA level and Exec Ed programmes, and, as such, it is not organised by the classical MBA subjects. Instead, it follows the rationale of the business manager—how she/he gets confronted with sustainability challenges and how he/she and his/her organisation builds ways and means for addressing them in a practical way, yet also with methodological rigour.

We are steering clear of the term “CSR” as much as we can in this book. The term seems to be controversial with managers. CSR is often seen as the remit of the CSR department (and not of line management) to deal with. It is seen as rather a tactical or defensive activity or at worst a PR exercise, rightly or wrongly associated with “doing good” or philanthropy. The reasons for the controversy are manifold and often not entirely justified. However, we wish stay clear of these misunderstandings.

The subject of sustainable business stretches, in the mind of the manager, far beyond challenges of social responsibility and includes concerns about risk management in relation to externalities, strategic issues management as social trends emerge, seeking competitive advantage and transforming business models with sustainability issues, broad-based strategy generation and implementation through stakeholder management.

All these concerns are instrumental in nature driven by the pressures of markets, societies and governmental and non-governmental organisations or inspired by long-term aspirations to claim industry leadership and seek first-mover advantages or simply to be recognised among the globally most excellent companies. These companies, it is assumed, attract more easily top talent and are more trusted by regulators, partners and customers, which can substantially reduce transaction costs.

Michael Porter defined competitive advantage as dependent on the position of the firm in the value chain and on how it deals with the five forces that define the industry structure. However, it is now easily recognised by managers that no matter how important the position of the company in the value chain and in the industry structure, the long-lasting advantages of the firm are to be found in the intangible resources which can be leveraged beyond the industry structure. These intangible resources are embedded in knowledge, relationships, capabilities and binding purpose , which can be leveraged for creating value with all stakeholders.

There is, of course, a whole body of research and a school of resource-based strategic reasoning to support this, but managers come to this conclusion purely based on their observation and experiential knowledge and find the ongoing academic divide on the best way to create competitive advantage rather irrelevant. An industry sector view and a resource-based view are perceived to be complementary by managers.

Many managers find also that opposing shareholder value to stakeholder value is maybe of theoretical significance, but not of much practical significance and a misleading way of painting managerial realities. Both pressures are continuously invading processes of managerial decision making, and opposing these from the outset hinders a clear focus on long-term value creation. In other words, opposing stakeholder value to shareholder value may provoke the unintended opposite effect.

The cliché that the pursuit of profit is most of the time opposed to “responsible behaviour” does not resonate with the new generation of managers who are coming to Exec Ed programmes. They have a more balanced outlook and consider these oppositions as abstractions or even aberrations of the real-life world of management.

Of course many (top) executives are driven by power, ego and financial gain, but in my observation, most are driven by a strong nonfinancial performance aspiration. This is key for understanding managerial behaviour.

This performance aspiration is not primarily focused on financial performance but rather shaped by the desire to achieve challenging goals, to rise above conflicting agendas, to solve difficult problems and to be seen as smart by accomplishing what others find impossible to achieve. It is easy to see how this perception of managerial motivation can be conducive for facilitating learning on sustainable business. There is therefore no need for moral teaching and telling managers to be more responsible. This is generally not effective anyway.

Starting from practical real-life concerns instead of theoretical concerns and recognising profit seeking as a natural and primordial drive for managers and businesses

Subscribing to the position that the business of business is profitable business indeed, but with the critical question of what makes business profitability sustainable

Providing texts to provoke critical thinking and critical debate on how to achieve sustainable profitability

Providing cases that are as close to the business reality and complexity as possible, where the link between financial and nonfinancial performance issues is always present

- Building up a rationale for a step-by-step learning process in six different stages:

Risk management

Issues management

Stakeholder management

Creating competitive advantage

Fostering innovation and transformation

Building organisational capabilities

There is currently high interest from the corporate world in what makes a sustainable business and the large majority of participants of Exec Ed programmes and the EMBA see the subject as integral to their development and further learning. We hope we have provided a book that can help to respond to these expectations.

Managing Sustainable Business: An Introduction

A business that is well managed for the long term

A business with a robust business model, a prudent financial model and highly developed value propositions for customers and all other stakeholders

A business that can anticipate or respond flexibly to sudden changes in the business environment, including the social and political environment

A business that is capable of transforming its business model in the face of irreversible deep changes in markets and in the expectations of society

A business that commands respect and trust

A business which is aware of the contexts it operates in and the shifting requirements of these contexts

One can identify a generic use of the word “sustainable” in the sense of lasting, robust, long-term oriented, which encompasses the entire business. Most managers sense that their business should stay clear of opportunistic, high risk, short-term-driven motives determined by profit maximisation only. They have seen the spectacular failures of this approach in the past with respected companies like Daimler Benz, Marks & Spencer, Citigroup and others, whose managers abandoned pride and purpose for power and stock options and in the end almost ruined their company and destroyed shareholder value on a massive scale. These concerns are about corporate sustainability .

At the same time, managers associate sustainable business with sustainability , which is a term that can be traced to the Brundtland Report ( Our Common Future , 1987) on sustainable development and refers to accountability of the company for its impacts.

Managers recognise that managing impacts and issues (economic, social, ethical, political, environmental) is often ignored in mainstream courses on strategy and business environment in EMBA programmes. However, managing impacts and issues is but a part of the entire challenge of sustainable business. Excelling in sustainable HR and talent management, sustainable finance, sustainable marketing, sustainable expansion into new markets, needs to be part of an overall approach to sustainable business. Effective stakeholder management, innovation and developing dynamic capabilities are key in this broad based approach. (See Parts III, IV, V and VI).

Sustainable Business: An Outline

A sustainable business is highly responsive to the demands and challenges of both markets and societies.

It optimises competitiveness as well as legitimacy and mutually beneficial relationships with key stakeholders by constantly adapting and renewing its value propositions through its portfolio of products, services, brand positioning and communications.

It also pays attention to the long-term shifts in the political, social and ecological environment on which it depends for its resources.

It is concerned about its reputational capital and the trust (social capital) it needs to keep transaction costs low and to benefit from a favourable licence to operate.

Managing sustainable business has become increasingly complex. There are several causes:

Globalisation has heralded new opportunities for companies but also causes new complexities in global supply chains, global competition, cross-cultural complexities and clashes of values and norms, weak governance environments, challenges to the power and legitimacy of big business and anti-globalisation movements.

The ICT revolution has transformed the way business is done and managed, but it has also made the global critical village possible. Global interconnectedness makes news travel fast and endangers reputational capital by sound-bite-driven media. Social, environmental and political issues can emerge and spread quickly and pose risks as well as opportunities for nimble companies.

Macro trends such as climate change, resource depletion, environmental depletion, demographic change, geopolitical change, talent shortages and increasing rich-poor divides between and within societies affect business models in the medium to long term and create new winners and losers.

This affects all business functions: procurement, marketing, finance, accounting, human resource management, product development and R&D. It will also affect the economics of the business models and the valuation of equities through risk assessment and risk mitigation and will change the competitive context of entire industries by the bets companies are likely to make to take advantage of changing circumstances.

The challenges to the governance of the firm are thus formidable, not in the least because investors are looking increasingly at the sustainability risks and opportunities underlying the business model and the long-term strategy of companies. Firms are well advised to take a strategic approach to these challenges in order to identify threats and opportunities as well as their strengths and weaknesses.

Resources need to be allocated, capabilities need to be developed and new knowledge needs to be harnessed. This requires sound judgement beyond normative rhetoric on leadership and corporate responsibility.

The normative rhetoric which is so pervasively used by activists within and outside the business schools is a serious impediment for mainstreaming the sustainable business agenda in executive education and executive practice, since this does not connect with the life world of executives and at best leads to tactical responses to activists’ demands.

On the other side, some CEOs might be posturing and paying lip service to the “urgent needs” of “concerted action” and the “transformational change required” but fail to lead and manage change internally, not in the least because management development for sustainable development is not adequate and because only a limited number of business schools seem capable of supporting this.

A Managerial Framework for Sustainable Business

- 1.

Risk Management: Managing the Accountabilities of Business

Knowledge management of inside-out impacts of the business model and the business strategy and managing accountabilities for impacts (externalities) in shifting social contract environments

- 2.

Issues Management: Managing the “Responsibilities” of Business

Knowledge management of outside-in impacts of new issues from the business environment on the business and adopting appropriate organisational responses for latent, emerging and maturing issues of “corporate responsibility”

- 3.

Stakeholder Management: Managing Competitiveness and Trust

Identifying, prioritising and weighing importance of key stakeholders and managing relationships as key resources for comparative advantage

- 4.

Strategic Differentiation: Creating Competitive Advantage

Developing sustainability value propositions to markets and stakeholders, including reconceiving products and services, redefining productivity in the value chain and developing partnerships

- 5.

Innovation and Business Model Transformation: Taking Great Leaps Forward

Identifying and entering market spaces with high sustainable value and transforming business models and capabilities to capitalise on emerging market value

- 6.

Managing Change: Developing Dynamic Capabilities and Managerial Talents

Developing organisational capabilities and managerial knowledge, skills and mindsets for sustainable business

Closing Reflection

A final reflection in this introduction concerns the instrumental/strategic versus the moral/normative case for sustainable business. My co-author Craig Smith who is an eminent professor of CSR and business ethics at INSEAD and I have had long debates on this, and we come from different perspectives. However, in the end we concluded that the opposition between both perspectives may be false and that they are rather complementary.

A purely strategic approach without any moral compass may not be sustainable since it may appear to stakeholders as not entirely sincere and trustworthy. A normative approach without strategic business underpinning may appear to shareholders as naive, unrealistic and a moral luxury and fall victim to the next round of cost-cutting.

But a normative framework like the UN Global Compact on Sustainable Business seems the minimum indispensable requirement.

We agreed that win-win solutions may not be possible all the time and that trade-offs made by managers in favour of short-term profits will be difficult to resist or avoid but should be criticised nevertheless.

In any case, the question whether sustainability is part of business ethics or rather that addressing ethical issues is part of sustainable business in a very “academic” question indeed.

I’d like to thank Craig for his enduring commitment to this book and his relentless production of new interesting case studies and for the enlightening debates we had in the 3 years leading up to the publication of this book. He is a fine scholar and an admired colleague in the field.

Further Reading on the Themes Touched on in This Introduction

Pearlstein, Steven. 2013, September. How the cult of shareholder value wrecked American business. The Washington Post Wonkblog .

Goedhart, Marc., Tim Kolter, and David Wessels. 2015, March. The real business of business . McKinsey and Company.