‘Equal opportunities’ policies were first modelled in Britain in the early 1980s. In 1980, the Commission for Racial Equality listed 73 employers who had adopted their draft equal opportunities policy. By 2004, three quarters of all workplaces had a formal written equal opportunities policy, up from 64% in 1998.1

Equal opportunities policies were designed to address discrimination against women and ethnic minorities at work. These are policies adopted by firms. They include promises not to discriminate, equal pay for equal work, oversight of recruitment policies and of promotions, and monitoring of the ethnic and gender mix of the workforce.

Before there were any such policies, there were laws against discrimination, notably the 1970 Equal Pay Act, the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act and the 1976 Race Relations Act (there were predecessors, and there have been reforms afterwards, but these are the most important). Both laws created quangos to enforce non-discrimination, which were known at the time as the Commission for Racial Equality and the Equal Opportunities Commission. Both had powers to investigate and to find against individual employers.

Though the EOC and the CRE were important enforcement bodies, the adoption of equal opportunities policies by firms signalled the dissemination and generalisation of a culture of equal opportunities. This is a sea change in British employment law and practice. Discrimination had been woven into the workplace to a remarkable degree in the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

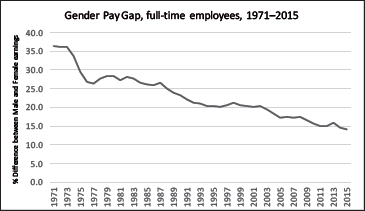

Today women are nearly half the workforce, and the gender pay gap is shrinking all the time. Employers have taken on many more black people, too, and the racially segregated workplaces that were common up into the 1970s are today exceptional.

Catherine Hakim called this change an ‘equal opportunities revolution’, and she is right. Whatever problems remain, it is hard to gainsay that the explicit promises and beliefs of mainstream British society are for equality of opportunity. It is a revolution because oppression in the home, at the borders, and in the ghettos had been a mainstay of British society, and one that shaped the world of work. A gender and racial division of labour made a hierarchy in which women and migrants were marginal workers. That hierarchy is being dismantled. More importantly, it has no significant, explicit defenders among the political or business elite.

Whether the change was caused by the new policies, or whether those policies were only symptomatic of the extensive recruitment of women and of black people, the evidence is that a profound change has taken place. We are, of course, still impatient at the persistence of discrimination, and rightly so. All the same, the distance travelled over the last 30 years is remarkable.

The paradox of the equal opportunities revolution is that very few people expected it to succeed. Most of those who worked for equal opportunities from the late 1970s on were either liberal or radical. These were people, for the most part, who saw the 1980s and 1990s as a depressing time, when progress had been thrown into reverse. For workplace organisation this was a time when trade unions lost their legal privileges and were pointedly attacked by employers, with the support of the government. Anti-trade union laws put workers’ representatives on the back foot. In the country, the tenor of government was hostile to working women and to ethnic minorities.

Curbs on welfare payments and social services as well as on nursery provision all hurt women who were trying to work. The governments of Margaret Thatcher and John Major talked about a return to ‘Victorian values’ and ‘back to basics’, seeming to suggest a far greater sympathy with traditional family life. At the same time harsh measures against immigrants, aggressive policing of inner cities, and a preoccupation with British values all seemed to point to a retrograde attitude toward black people.

And yet, the era of those Conservative governments, between 1979 and 1996, was just when the equal opportunities revolution was underway. This is the time when there was the greatest take-up of equal opportunities policies at work. The attitude of the government to those changes was mixed. Some in the Conservative Party were outspoken in their hostility to the equal opportunities policies adopted by local authorities, which they decried as ‘social engineering’. There were moments when it seemed that both the CRE and the EOC would be targeted by a hostile government, and even abolished. The Greater London Council, which had been a pioneer of equal opportunities policies, was abolished, and much of the criticism of the GLC that preceded the abolition highlighted its ‘loony-left’ policies on race and gender.

For all that, the government never did abolish the CRE or the EOC, and the Department of Employment quietly supported their efforts to promote equal opportunities policies. More importantly, leading businesses, at first cautiously, and then enthusiastically, embraced the equal opportunities revolution. By 1998, 55% of all private business had equal opportunities policies (rising to 68% in 2004). All the other reforms of industry and employment law were pulling the country to the right. But the incremental reforms under the heading of equal opportunities carried on.

Most of the political left’s policies seemed to be out of keeping with the times. There was not great support for economic planning, or trade union power — not even among trade unionists. But there was increasing sympathy for equal opportunities. These policies seemed to chime well with the other innovations that were taking place at work. Codes of practice, legalisation, tribunals, monitoring, all seemed commensurate with the new discipline of Human Resource Management. HRM saw personnel departments take on much of the work of managing relations between employers and employees that had formerly been done through negotiations with trade unions. Social scientist Alan Wolfe said that in the 1990s the right won the economic war and the left won the cultural war. One clear sign of that is the integration of the goal of equal opportunities within a restructured economy.

Trying to understand why the equal opportunities revolution happened, when the conditions seemed so hostile to such change, is one of the goals of this book.

All change at work

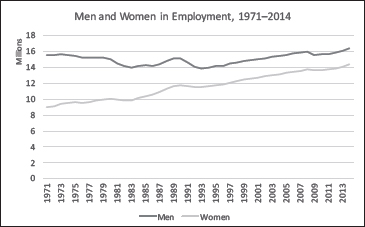

Between 1950 and 2015 the regime of workplace organisation has been through a sea change. Back then women made up just 35% of the workforce. Since then women’s share in employment has climbed markedly to around 46% today.

Source: ONS

Between 1991 and 2011 the percentage of ‘White British’ residents in England and Wales fell from 94% to 86%. In England and Wales, a workforce of 25.7 million now includes 3 million non-white workers.2

Go further back and see that in Britain at the start of the twentieth century just one tenth of married women worked, compared with 60% in 1990. Though Britain in 1900 governed an empire of 350 million, including India, much of Africa, and the Caribbean, the black presence in the United Kingdom was relatively small, until migration from the West Indies (from 1948), East Africa (of Asians from 1967), India, and Pakistan began. Net migration to the United Kingdom between 1961 and 2011 was 2,149,000, more latterly coming from Africa and Eastern Europe.3

On the basis of these changes, the Home Office claimed in 2002 that Britain was ‘a more pluralistic society’ and a ‘multicultural society’, and further that ‘today very few people believe that women in Britain should stay at home and not go out to work’.4

The change in the make-up of British society, and most importantly in its workforce, has many causes. They are: agitation on the part of women and black workers, full employment and economic restructuring; and these changes are clearly marked by laws on race and sex discrimination, enforced by dedicated government bodies, and adopted as workplace codes by most employers. These legal codes forbid discrimination and unequal pay for equal work — and much more. Just what the forces were that gave rise to these changes is the subject of this book.

The change in the composition of the British workforce was sharply contested. As we will explain in Chapter One, the particular settlement between employers and labourers in the early twentieth century was exclusive, resting on an overwhelmingly white and male workforce that had established its rights and position over many years. Later, as women and then black workers were introduced into the workforce, labour relations were markedly hierarchical, as these newer recruits were employed in defined areas, and on worse terms.

The old labour regime was not deliberately constructed by any single agent to be the way that it was. Nobody sat down and planned a largely white, male labour force. Rather it came about out of the distinctive social position of the core industrial workforce, and the way that they fought to establish their authority within the workplace. But if it was not deliberately designed to be exclusive, discriminatory, and hierarchical, once in place it was. What is more, many agents, employers, governments, and even trade union representatives often used the shape of the settlement to defend their own positions, often to the detriment of those women and black people who were disadvantaged.

The unravelling of the established gender and racial ordering of the workforce, and its reconstruction, is a long and complicated story, and it is by no means complete. All the same that sea change in the working lives and broader society of Britain has been remarkable. In this book we look at the equal opportunities revolution as a real, historical event, to try to understand the actions and decisions that people took that made it happen.

Before the legislation of the 1970s the concept of ‘equal opportunity’ had a distinctive meaning. Equal opportunity, a shortening of ‘equality of opportunity’, came into use in the late nineteenth century as liberals sought to show how they were not like socialists. Henry Broadhurst explained the meaning of ‘True Liberalism’: ‘Liberalism does not seek to make all men equal; nothing can do that. But its object is to remove all obstacles erected by men which prevent all having equal opportunities.’5

At that time, of course, the Liberals were facing down an emerging challenge from the labour movement, which was demanding equality. The liberal press parodied that as ‘levelling’. Liberal Party-supporting trade union leader Henry Broadhurst was saying that he was not levelling all people down to the same point, but giving them ‘equality of opportunity’. (Note that the inequality being looked at is social inequality, between ‘men’.)

The Reverend J. J. R. Armitage, the Munitions Area Chaplain, lectured on the meaning of ‘Equality’ at the Empire Theatre, Coventry during the First World War. Armitage was sure that ‘the doctrine of equality had no sanction from science or from experience’. On the other hand, the ‘clergy and the Church of God, without fear or favour, had through the centuries preached to the all-powerful ruling classes that the lowest soul was in the eyes of Heaven of equal value with the highest’. He said ‘they should endeavour to make it possible for every boy, without restraint of class privilege or birth, to go wherever his talent leads him’. If only we could ‘grant equality of opportunity and the way was opened in competition’.6

In 1943, in the middle of the Second World War, Viscount Hinchingbrooke was talking to the Bradford Rotary Club about the Conservative Party of the future. Lord Hinchingbrooke ‘urged the desirability of a society in which an individual, in whatever circumstances he might be placed, would have full scope to use his abilities in service of his fellow man’. ‘Equality of opportunity’, he said, ‘therefore became one of our war aims — by which all might attain to positions of highest endeavour in service to their fellows’.7 In raising the ideal of ‘equality of opportunity’ Viscount Hinchingbrooke was trying to head off the more socialistic aims of the Beveridge Report, of which he thought Britons ought to be wary.

In all these instances, equal opportunities are set out as the fulfilment of the free market; equality of opportunity is the counter-claim to the socialist demand for equality. To get rid of unfair discrimination is to make the labour market more perfect.

This was the meaning, too, of Milton Friedman’s 1979 distinction between equality of opportunity and equality of outcome. Noting that the American Declaration of Independence seemed to put in train two rival principles, Liberty and Equality, Friedman explains: ‘In the early decades of the Republic, equality meant equality before God; liberty meant the liberty to shape one’s own life.’ More, Friedman says: ‘Equality came more and more to be interpreted as “equality of opportunity” in the sense that no one should be prevented by arbitrary obstacles from using his capacities to pursue his own objectives.’ He goes on to say: ‘Neither equality before God nor equality of opportunity presented any conflict with liberty to shape one’s own life’ — that is they were commensurate with a free labour market.8 He expands, later on:

Equality of opportunity, like personal equality, is not inconsistent with liberty; on the contrary, it is an essential component of liberty. If some people are denied access to particular positions in life for which they are qualified simply because of their ethnic background, color, or religion, that is an interference with their right to ‘Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.’ It denies equality of opportunity and, by the same token, sacrifices the freedom of some for the advantage of others.9

Friedman contrasts equality of opportunity with another idea of equality that he differentiates by giving it different qualifier, ‘equality of outcome’:

A very different meaning of equality has emerged in the United States in recent decades — equality of outcome. Everyone should have the same level of living or of income, should finish the race at the same time. Equality of outcome is in clear conflict with liberty.10

Equality of opportunity was a call often linked with education, as in 1914 when Mr Henry Davies, the Glamorgan Director of Mining, appealed to the Miner’s Federation to get behind a school set up by mine-owners. ‘There was to be equality of opportunity for all’, said Davies, ‘the miner’s son, the checkweigher’s son would have the same advantages of the manager’s son’.11 In 1917 a National Union of Teachers’ leader Mr H. Walker called for the raising of the school leaving age, at a meeting of the Labour Club, backed by councillor J. Thicket, who said ‘there should be equality of opportunity for the children of rich and poor alike’.12

The idea of ‘equality of opportunity’ had been worked out as a liberal answer to labour. Later on, the moderate left took it up themselves as a form of words that seemed to be a concession to egalitarianism. In the House of Lords, Labour peer Lord Haldane attacked an anti-union law proposed as a reaction to the General Strike of 1926. The General Strike was wrong, said Haldane — ‘never again if it could be prevented would such a blow be struck at the heart of the country’ — but things would never be satisfactory ‘until workmen and employers come to be more of one mind than at present’. Arguing for such a meeting of minds, Haldane said ‘workmen desired to have the opportunity of making the best of their lives and securing for themselves the best conditions of their labour… Working people asked not for luxuries, but for equality of opportunity, and they desired that still more on behalf of their wives and children.’13

The phrase ‘equality of opportunity’ was first used as a challenge against sex discrimination toward women teachers. For them, equality of opportunity had keen meaning because of the rule that they were to be laid off if and when they married (on the assumption that they would be supported by their husbands, and that their leaving would free up jobs for men). Miss S. M. Burls told the 1929 annual conference of the National Union of Women Teachers that they ‘demanded freedom to apply for every post in the educational sphere’, and ‘impartiality which considered immaterial questions of sex or celibacy, and the justice which awarded equal remuneration and equal opportunities of promotion’. A woman’s marriage, she said, should be treated ‘as her private concern just as all the world treats a man’s’.14 At a meeting of the Plymouth Women’s Hospital Fund, chair Dr Mabel Ramsay said ‘medical women occupied an excellent position in Plymouth, but they would not be satisfied until they got the same opportunities as those given to men’, and they ‘could not stop until every avenue was open to all women’.15

The Labour Party manifesto in 1950 said ‘Our appeal is to all those useful men and women who actively contribute to the work of the nation’. They called on manual, skilled, technical, and professional workers, ‘and housewives and women workers of all kinds’. The Labour Party set out its goal of realising the ‘means to the greater end of the full and free development of every individual person’. In the context of full employment, the manifesto committed themselves: ‘Labour will encourage the introduction of equal pay for equal work by women when the nation’s economic circumstances allow it.’16 The Conservatives were a little more cautious, restricting their offer of equal pay — ‘principle of equal pay for men and women for services of equal value’ — to public employees, and also limiting it to what could be afforded.17 Five years later, Labour’s promises were vaguer, offering that ‘our goal is a society in which free and independent men and women work together as equals’, but without any proposals to make that happen.18 Women did not feature very much in the Labour Party’s electoral appeals, though in 1964 the “New Britain” they foresaw would rely on ‘encouraging more entrants to teaching and winning back the thousands of women lost by marriage’ (it was an offer that was adopted by the Conservatives at the following election). Nancy Seear was an economist and former personnel manager, who had been on the Production Efficiency Board at the Ministry of Aircraft Production in the war. She advised that ‘if we want to find an unused reserve of potential qualified manpower it is among women that it can most easily be discovered’.19

Two years later, and again with ‘full employment’ as the background, Labour put down a marker:

[W]e must move towards greater fairness in the rewards for work. That is why we stand for equal pay for equal work and, to this end, have started negotiations.

We cannot be content with a situation in which important groups — particularly women, but male workers, too, in some occupations — continue to be underpaid.

In 1966 the Conservatives did say ‘we intend that there should be full equality of opportunity’, though it was not linked to any specific measures, but rather an argument for a more competitive economy in which we should not ‘all be equally held back to the pace of the slowest’. At the same time, they appealed to women as homemakers more than they did as potential wage earners, promising that ‘we want to see family life strengthened by our Conservative social policies’.20

The TUC Congress in September 1965 followed this with a resolution reaffirming

its support for the principles of equality of treatment and opportunity for women workers in industry, and call[ing] upon the General Council to request the government to implement the promise of ‘the right to equal pay for equal work’ as set out in the Labour Party election manifesto.21

Labour won office in 1964 and showed themselves willing to adopt some cautious measures against discrimination in the 1965 Race Relations Act. Then in 1970 they made the following manifesto statement on equal opportunities, which in its main outlines anticipated the legislative framework that was to follow, and would shape our current employment regime:

[W]e believe that all people are entitled to be treated as equals: that women should have the same opportunities and rewards as men. We insist, too, that society should not discriminate against minorities on grounds of religion or race or colour: that all should have equal protection under the law and equal opportunity for advancement in and service to the community.

Labour’s commitments were ahead of the Conservatives’ though these too were sharply opposed to discrimination. The Conservative Party under Edward Heath also committed itself: ‘We have supported and sought to improve the equal pay legislation.’ Heath’s Conservatives said they wanted to ‘ensure genuine equality of opportunity’. They despaired that ‘many barriers still exist which prevent women from participating to the full in the entire life of the country’, and that ‘women are treated by the law, in some respects, as having inferior rights to men’, promising ‘we will amend the law to remove this discrimination’.22

In 1974, Harold Wilson put his name to Labour’s election appeal. The main thrust of the manifesto was for greater control by the British people over the powerful private forces dominating economic life, and for an extensive incorporation of industrial relations.

Alongside those demands, Wilson set out another area of policy, saying ‘it is the duty of Socialists to protect the individual from discrimination on whatever grounds’. Under the heading ‘Women and Girls’, he said that they ‘must have an equal status in education, training, employment, social security, national insurance, taxation, property ownership, matrimonial and family law’. Further, he promised that ‘we shall create the powerful legal machinery necessary to enforce our anti-discrimination laws’.23 The following October, Labour could say ‘new rights for women and our determination to implement equal pay have been announced’.

Britain’s first Race Relations Act was passed in 1965, but its remit was modest. It was the Race Relations Act of 1976 that made race discrimination illegal and created the Commission for Racial Equality with powers to investigate employers to persuade them to redress the balance. Six years earlier, in 1970, the Equal Pay Act had been passed — following a strike by women machinists at Ford’s Dagenham plant demanding parity with equivalent workers on the assembly line. A further act of 1975 created the Equal Opportunities Commission that had powers to investigate and reprimand employers and other institutions for discrimination. These Commissions were both non-departmental public bodies.

With the legislative commitment, the stage was set for the revolution in equal opportunities that was to follow. As we shall see, one of the most far-reaching consequences of the legislation, and the Commissions it created, was the adoption of equal opportunities policies by employers. These policies were the third leg of the stool alongside the law and the Commissions. In themselves they were just pieces of paper — though they also tended to reorganise and even lend greater importance to personnel management, particularly in larger companies, as managers committed to take on the responsibility of enforcing the policies. They might be actively embraced by far-sighted employers, or taken on without much thought, or even reluctantly, for fear of sanctions under the law. But once in place they were a framework through which employers and employees, unions and Commissions, could negotiate the new working conditions. Their widespread adoption in the 1980s and 1990s gave institutional form to the equal opportunities revolution.

Agents of the equal opportunities revolution — activists, officials, analysts, politicians — more often talk down the successes than talking them up. How could one be satisfied with anything less than equality? As Rebecca Solnit writes, we need the ‘ability to recognize a situation in which you are travelling and have not arrived, in which you have both cause to celebrate and fight’.24

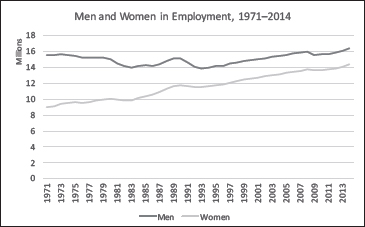

The equal opportunities revolution has been superimposed upon the old corporatist order of business, and has never wholly eclipsed it. So too, the inequalities between men and women, and between white and black, are greatly moderated but have not disappeared. How could it be otherwise? Equal opportunities does not imply equality of outcome. Equality of opportunity in the sense of greater competition has increased social inequality in income, as measured in the ‘Gini coefficient’ (0=equality, 1=inequality).

Source: Mike Brewer et al, Accounting for changes in inequality since 1968, Institute of Fiscal Studies, 2009, p 1

The income gap between wealthy and less so has opened up, and to some extent that is associated with the inequalities of race and sex. Even if all racial discrimination were to cease, since socio-economic status tends to reflect the socio-economic status of parents, black people by their incomes, on average lower, will still raise children who are less likely to succeed than their white counterparts. That would be so because colour would still be a marker of class, even if there were no active discrimination. For women, the income penalty of leaving full-time employment to raise children persists stubbornly despite many measures (such as the legal right to paternal leave). But for the most part, women have improved their position relative to men, and black people have improved their position relative to white, over time. The distant horizon of equality of outcome has not been reached, and campaigners’ determination to press onwards is both understandable and laudable. But the perspective of the campaigner is not one that illuminates just how far we have come over just a few decades.

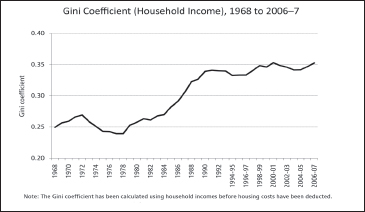

On average women earned 36.5% less than men per hour in 1970, compared to 15% less than men in 2010.25

There are two ways to measure the gender pay gap. If you compare the earnings of men and women in full-time employment, the gap today is quite small, and has fallen over some years. The other way, which compares all hourly earnings, gives a larger pay gap because more women work in part-time employment, and part-time employment is less well paid by the hour. The striking thing, however, is that while hourly pay for all workers gives a larger gender pay gap, the same trend towards convergence is there in both measures. The gender pay gap is closing.

Source: ONS

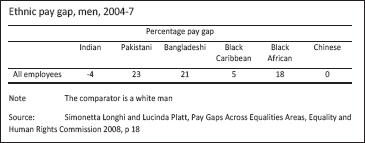

The ethnic pay gap, by contrast has worsened somewhat in the last ten years. However, the position of some established ethnic minorities, at least as reflected in the ethnic pay gap, is more encouraging.

According to the estimates, the ethnic gap in hourly average pay between white men and Indians, black Caribbean, and Chinese men is statistically insignificant. These minorities are well established, and their disadvantage in employment in earlier times is well recorded, but more recently they appear to have overcome those barriers. Black Africans and Bangladeshis are more recent arrivals, and they are at a clear disadvantage in the jobs market, as are Pakistanis (suggesting that Muslims in particular are at a disadvantage in the workforce today). The social science researchers who looked at the ethnic pay gap saw one of the principle barriers to advance being the concentration of these minorities in particular, and precarious, occupations — black disadvantage being closely linked to class.26

This book is mostly about relations at work. The equal opportunities policy is a workplace policy. Like the sex- and racebased hierarchies that went before, equal opportunities policies are about managing all employees, white and black, men and women. In what follows we look first at the old regime that was overturned by the equal opportunities revolution, in Chapter One. This chapter is quite detailed, explaining how sex and race discrimination came to be built in to the old ‘corporatist’, or ‘tripartite’ order of industrial relations. Then we go on to look first at the question of race, the creation of the Commission for Racial Equality and the promulgation of equal opportunities policies at work in Chapter Two. In Chapter Three we go on to look at the question of women, the Equal Opportunities Commission and its impact upon employment practice. In Chapter Four we consider the revolution in workplace relations overall, and ask what the motives were for employers who adopted these policies. The fifth chapter looks at some of the critical reaction to equal opportunities policies, both conservative criticisms and radical ones. In Chapter Six we consider the way that equal opportunities policies came as part and parcel of the new Human Resource Management theory of workplace relations. Chapter Seven looks at the way that the organised labour movement was at odds with the changes at work, and how the economic cycle impacted on employment, for men and women, and for black and white. Many looking at these questions have showed that influences outside work, in particular the ‘second shift’ of domestic work for women and Britain’s institutional racism, have entrenched discrimination — and we look at these in Chapter Eight, though drawing attention too to the ways that even those barriers are being moved. Chapter Nine looks at the different examples that British policy makers had to draw on, of native self-government in the British Empire, of the Fair Employment Commission in Northern Ireland, affirmative action in the United States, and the work of the European Union on women’s equality. In Chapter Ten we look at how the equal opportunities model was generalised in workplace rights for lesbians and gays and for the disabled, and also how, paradoxically, the generalisation of the model made the EOC and the CRE redundant. Chapter Eleven looks at some of the contradictions in the system that has been created by the equal opportunities revolution.

There is a kind of awkwardness that comes from looking at all the social questions that fall under the equal opportunities category together. The two most important equal opportunities questions: those of discrimination against women, and of discrimination against black people, are matters in their own right. The case for considering them under the same heading is that they really are under the same heading, as the two substantial questions addressed in equal opportunities policies. They are very different, though. Sex cuts through society across the question of class, at a right angle to it, as it were. There are women in the upper classes, and women in the working classes. Race, while it is not the same as class, tends to track social inequality much more directly. Women’s oppression in the family has been a feature of the life of elites, and of working-class people — the inequality is reproduced in each family unit. There have been wealthy black people, and even black people in the ruling elites (though very few might be counted as such in Britain). On the other hand, the social status of black people has been shaped by their relationship to a division of labour that is outside of the home (which is not of course to say that the question of the domestic economy and women’s relationship to it is not an issue for black people). Proportionately, black and Asian people are fewer, pointedly fewer, than the white population (around 87% of the population of the United Kingdom), so that they have at times been referred to as ‘the minorities’; there are fewer black and Asian people than there are women, who, though they have in occasional mistakes been referred to as a minority, are in fact the majority. For that reason, the question of equality for women has probably been more important, not morally, but in its weight within British society, and so too have changes in the balance of power between the sexes.

This book dodges between the two cases of sex discrimination and of race discrimination, sometimes seeming to read as if they were the same, but that is only because what is being addressed is the policy of equality of opportunity. Equal opportunities policies are not, of course, restricted to women and black people. The equal opportunities revolution has expanded outwards to take in new questions, such as sexual orientation, disability, and more. Those questions are given less weight in the treatment here, because it is largely historical, looking at the way that the ideas, campaigns, policies, and practices changed over the years. In driving those changes, the questions of sex and of race discrimination simply carried more weight. No moral judgment is intended in the priority given, only to tell the story.

The words we use about race are often awkward, and rightly so, since there really are no good grounds for sifting people out according to their colour. The words date quickly because they carry an unstated stigma. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was founded in America in 1909 and has fought for black Americans ever since — but few today would be happy with the choice of its title. C. L. R. James wrote many essays in support of ‘negroes’, where today we would say black people. In the 1970s some radical Asians called themselves ‘black’, and the radical Greek economist Yanis Varoufakis even served as president of the Essex University Black Students Society. The collective ‘black’ for all those who are not white, though, is not always right. British Asians are often differentiated from black Britons, and called Asians, or sometimes brown. Black would have done as a collective noun for all those who are not white in the 1970s, but less so today. In the text I have used ‘black’ as the generic word where the meaning is clear, sometimes ‘black and Asian’, ‘black and brown’, or the negative ‘not white’ — knowing that none of these are satisfactory. The American ‘people of colour’ strikes many as too close to ‘coloured’, and sounds demeaning, and ‘black and minority ethnic’, while accurate, strikes me too much as policy-makers’ jargon. I have not changed terms in quotations, to keep the historical record. No words will ever satisfy, because the naming fixes what is fluid. Geneticists tell us that there is no biological foundation to the concept of race, fixing as it does on minor heritable features of skin colour and hair, and point out that the genetic variation within ‘races’ is greater than between them. Still the fetish concept of race is a social fact in that people treat it as if it were real, and so in their actions it becomes real. I hope that people will not get caught up too much in the language used here, which will no doubt be out-of-date already.