9

Chinese Religions

Introduction

Religion, in the modern Chinese context, is festive, celebrating the passage of men and women in the Chinese community through the cycle of life and death. Chinese religion is traditionally defined by the rites of passage, i.e. birth, maturation, marriage and burial, and the annual cycle of calendrical festivals. Membership of the Chinese social community is demonstrated by participation in the rites of passage and the annual festivals, rather than by intellectual assent to a body of revealed scripture. Chinese religion is therefore a cultural rather than a theological entity. All of the religious systems coming from abroad into the Chinese cultural complex found it necessary to accommodate to the religious and cultural values of China in order to survive and function. The success of Western religions especially has depended upon acceptance of the strong Chinese values of family and social relationships, and adaptation in some way to the customs of the Chinese people. The seasonal festivals as well as the rites of passage have equally survived the iconoclastic rigours of the socialist state of mainland China and the even more devastating secularized education and industrial revolution of maritime China. (‘Maritime China’ and ‘diaspora China’ are almost synonymous: maritime China refers to all Chinese living outside of mainland China on the Pacific basin or the islands of South-East Asia, while China of the diaspora refers to all Chinese living abroad owing to the political and economic situation on the mainland.)

The term for religion in China, tsung-chiao, refers literally to a tsung or lineage of chiao or teachings, of which the common men and women of China have traditionally admitted three: the Confucian system of ethics for public life; the Taoist system of rituals and attitudes towards nature; and the Buddhist salvational concepts concerning the afterlife. The three teachings, Buddhist, Taoist and Confucian, act as three servants to the faith and needs of the masses, complementing the social system. Confucius regulates the rites of passage and moral behaviour in public life; Taoism regulates the festivals celebrated in village and urban society, and heals the sick; Buddhism brings a sense of compassion to the present life and salvation in the afterlife, providing funeral rituals for the deceased and refuge from the cares of the world for the weary. But the Chinese commonly say that ‘the Three Religions all revert to a common source’ (San-chiao kuei-i), meaning in modern times that in fact the functionaries or priests of the three religions are dependent on the beliefs and needs of the common people of China, and attain meaning and livelihood as servants of the people. Religion is therefore a celebration by and for the people.

The Main Primary Sources

The main primary sources for the study of Chinese religion are: (1) the Confucian ritual classics, histories and local gazetteers; (2) Taoist canonical writings, popular manuals and fiction; and (3) Buddhist canonical texts and popular devotional shan-shu books. The Confucian sources for religious custom and the rites of passage include later dynastic summaries in the form of sumptuary or ritual laws governing provincial and local variations in the rituals used at birth, maturation, marriage and burial [25]. Local and provincial officials frequently summarized the state-approved ritual laws in popular manuals commonly known as Complete Home Rituals, still available in temple and village bookshops in maritime China [6]. Though the variations found by anthropologists throughout mainland and maritime China often seem too disparate for systematic comparison, in fact at the deep structural level the Chinese rites of passage always follow the Confucian model.

The primary source for public ritual where a Taoist priest or liturgical expert is required is the Taoist canon, now available in inexpensive photo-offprint for scholarly and ritual use [5]. The canon contains hundreds of chiao rituals of renewal and chai funeral liturgies used today for festival and for burial. The canon also preserves philosophical treatises, exorcisms and healing rituals, internal ‘alchemy’ or meditative tracts, alchemical formulae, medicine and herbal texts, and other rich sources of myth and popular Chinese religious practices. Field research in East and South-East Asia has uncovered a vast quantity of primary materials concerning the modern practice of Chinese religion in mainland and maritime China of the diaspora (South-East Asia). These modern sources are now in the process of publication [34; 35].

Popular Buddhist sources of Chinese religious practice are found in the shan-shu publications, privately funded treatises on meritorious lives, legends and myths for public distribution [10; 18]. (For other sources of Buddhist practices, see chapter 8 on Buddhism in this volume.) Popular fiction dating from the Ming and the Ch’ing dynasties onwards, available in corner bookstores and penny lending libraries throughout maritime China, has been used as a firsthand source for popular beliefs and practices. The pioneering work in these vernacular publications has been done by the noted sociologist and sinologist Wolfram Eberhard [10].

An Introduction to the History of Chinese Religion

Chinese religious history is divided into four major periods, listed traditionally as the spring, summer, autumn and winter of cultural development [2; 33]. The birth of Chinese religion is traceable to the oracle bones: prognostications were made by inscribing questions to the spirits on the carapace of a tortoise or the leg bone of an ox, and then applying heat to the bone to obtain an oracle reading. The cracks appearing in the bones gave the negative or positive response of the spirit to the problems posed by the Kings of Shang, c.1760–1100 BCE, China’s first historically documented period [19]. The religious cosmology depicted in the oracle readings is not unlike the cosmology of later summer and autumn Chinese history.

The later spring of China’s religious history extends from the beginning of the Chou kingdom, c.1100 BCE, through the Warring States era to the beginning of the Han dynasty in 206 CE. During this extended period six ways of thought are generally recognized to have formed the core of the Chinese cultural/religious system. Three of these, the moral/ethical directives of Confucius, the penal codes of the legalists, and the secular agnosticism of the logicians, form what came to be called the Confucian way (Ru-chiao). The teachings of the Confucian school are traditionally considered to be collected in the Four Books and the Five Classics [24]. The legalist writings and the works of the logicians, along with the writings of the Confucian classics, are well summarized in the History of Chinese Philosophy of Feng Yu-lan, translated and annotated by Derk Bodde [11].

The second set of three teachings from ancient China, the Taoist, Muoist and yin-yang Five-Element schools, form what came to be called spiritual Taoism (Tao-chiao) in the summer of Chinese religious history. The works of Lao-tzu (sixth/fifth century BCE), and Chuang-tzu (fourth century BCE) are the fundamental mystical and theoretical sources for religious Taoism [23]. The treatise on the brotherhood of man and universal love of Muo-tzu is now included as a part of the Taoist canon, providing inspiration for the sworn brotherhood and fraternal societies of modern China [47]. The yin-yang Five-Element (or Five-Mover-Five-Phase) cosmology which derives from the Tsou Yen school of ancient China formed the theoretical system of the so-called ‘New Text’ Confucian liturgists of the Han dynasty and inspired the first converts to religious Taoism [20].

In a more holistic sense such generalizations, which create a false dichotomy between the philosophical and the religious, the Confucian and the Taoist, are purely academic, i.e. simple heuristic devices to explain the richness of the Chinese religious/cultural heritage. In practice the Confucian statesman, Taoist poet and master of ceremonies for popular household ritual were often the same person. Like two sides of the same precious coin, Confucian social ethics and Taoist communion with nature formed the core of the Chinese religious spirit [29].

The second period of Chinese religious history, extending from 206 BCE to 900 CE, the summer or maturity of the three religions of China, witnessed the introduction of Buddhism into China from India; the formation of liturgical or spiritual Taoism as the priesthood of the popular religion; and the supremacy of Confucianism as custodian of the moral/ethical system of Chinese social culture. The rites of passage summarized by the New Text Confucianists of the early Han period, and the grand Taoist liturgies of renewal, became standardized for all of China [15].

The third period of Chinese religious history, the autumn or religious reformation, extended roughly from the beginning of the Sung dynasty c.960 CE to the end of the Ch’ing dynasty and the imperial system, 1912 CE. During this period a true reformation of the religious spirit of China occurred, some 500 years before the reformation of European religious systems. The Chinese religious reformation was typified by lay movements in both Buddhism and Taoism, a syncretism, even ecumenism, between Buddhist and Taoist spiritual elements, and the growth of local popular cultures [15]. Secret societies, religious cults, clan and temple associations, merchant groups or huikuan flourished throughout China. Christianity was brought to China by Jesuits in the sixteenth century, and by increasing waves of missionaries in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but owing to the inability of Christian missionaries to adapt to the religious cultural system of China, it never equalled the popularity of Buddhism in the Chinese context [15].

The modern period of Chinese religious history is compared to winter in the four seasons of nature’s constant cycle. Like a phoenix rising from the ashes of a burnt-out fire, or the drop of yang in the sea of yin which brings about cosmic rebirth in the depths of winter, the spirit of Chinese religion is at present experiencing a new vitality and rebirth both in the People’s Republic and the maritime diaspora of China. To study Chinese religion in the modern era is indeed illuminating, since the structure of the religious system, which was often hidden by the proliferation of local customs and rituals in the recent past, is now laid bare by the necessities of secular society, and the exigencies of cultural continuity in a world filled with political as well as technological upheaval. Chinese religion continues to be a vehicle of self-expression and identity for the people who comprise China’s masses, whether in continental, maritime or emigrant China overseas.

The Main Phases and Assumptions of Scholarly Study of Chinese Religion

The modern study of Chinese religion can be broken down into three main phases, namely: (1) the nineteenth-century scholars who approached the study of China from the superior colonialist attitude or as missionaries who saw Chinese practices as gross superstition; (2) the early and mid-twentieth-century scholars who as historians of religion or anthropologists approached the Chinese experience from the ‘objective’ or ‘scientific’ viewpoint; and (3) the structural phenomenologists who by participatory observation attempt to see Chinese religion from its own experiential ‘eidetic’ perspective.

The major works of the first group of sinologists who studied Chinese religions were published between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. De Groot’s massive The Religious System of China and Henri Doré’s Superstitions chinoises are classics of this period [7; 14]. The second group – historians of Chinese religion and anthropologists, with extensive fieldwork published during the past thirty years – are typified by the British social anthropologist Maurice Freedman and the American positive school of anthropology, represented by Arthur Wolf [49]. Where Freedman holds for the structured systematic view of Chinese religious practice, Wolf emphasizes the local, non-systematized and eclectic nature of field evidence. The excellent bibliography of Chinese religion prepared by Lawrence Thompson and the textbook of Chinese religion by the same author summarize modern studies in the field [42; 44].

The third and most modern form of Chinese religious studies is typified by the intensive participation of the scholar in the religious life of the Chinese environment, an approach to Chinese religion based on laying aside one’s own cultural assumptions and adopting the eidetic vision of the subject. This approach, which is basically structural in nature, owes much to the insights of Claude Lévi-Strauss, who in the study of South American myths first proposed a deep-structure theory underlying the seemingly contradictory nature of field evidence. The works of Kristofer Schipper, Emily Ahern, David Jordan and Liu Chih-wan are typical of scholars who have gone deeply into field experience to explain their insights into Chinese religion [1; 17; 28; 40]. To the above names and titles must be added the impressive work of Professor Kubo Noritada, whose field experiences in China (both maritime and mainland), and publications, are significant [22].

The Basic Assumptions of the Chinese Religious System

Chinese religion as practised in the twentieth century is based solidly on the yin – yang Five-Element theory of nature. This is a composite of the Taoist, the Tsou-yen and the Fang-shih schools of the late spring period of Chinese religious history [27].

Cosmic Gestation

From the Taoist tradition, specifically the forty-second chapter of the Lao-tzu, is taken the definitive statement of cosmic gestation:

The Tao gave birth to the One. (T’ai-chi)

The One gave birth to the Two. (yin and yang)

The Two gave birth to the Three.

The Three gave birth to the myriad creatures.

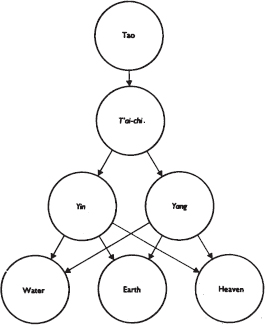

The meaning of this text (see figure 9.1) is dramatically expressed in Taoist ritual, seen throughout maritime China, South-East Asia, Taiwan, Hong Kong and modern Honolulu. The ritual is called Fen-teng (‘Dividing the new fire’) and is an essential part of the Taoist Chiao rites of cosmic renewal [37].

Yin and Yang

From a new fire struck from a flint is lit a first candle, representing the immanent, visible Tao, T’ai-chi or primordial breath within the (head) microcosm of man. From the T’ai-chi is lit a second candle, representing primordial spirit, or soul within man, the chest or heart of the microcosm. A third candle is lit symbolic of vital essence, the gut or intuitive level within man. These three candles represent T’ai-chi, the immanent, moving Tao of nature, yang and yin. They also represent the Three Spirits of the Transcendent Tao’s working in nature: San-ch’ing, Primordial Heavenly Worthy who governs heaven; Ling-pao, Heavenly Worthy who governs earths; and Tao-te, Heavenly Worthy who rules water and rebirth. Thus the Tao gestates on the macrocosmic level, heaven, earth and water; on the microcosmic level, head, chest and belly (intellect, love, and intuition). On the spiritual level the Tao is seen to be ever gestating, mediating and indwelling within man [39].

Figure 9.1 A structural view of the Chinese cosmos (from the Lao-tzu, chapter 42). The Tao gives birth to the One: T’ai-chi or primordial breath. The One gives birth to the Two: yin and yang. The Two give birth to the Three: watery underworld, earth and heaven. The Three give birth to the myriad creatures.

The Five Elements

Just as the cosmic gestation chapter of the Lao-tzu is dramatically expressed in modern ritual, so the yin – yang Five-Element theory is still enacted during the annual celebration of cosmic renewal, in modern maritime China. The ritual is called Su-ch’i and occurs on or about the winter solstice, or whenever a Chiao festival of renewal is being celebrated. During the rite, a Taoist ritual expert, called ‘Master of Exalted Merit’, plants the five elements, i.e. wood, fire, metal, water and earth, into five bushels of rice, which represent east, south, west, north and centre, i.e. the entire cosmos [32]. The elements are symbolically represented by five talismans, drawn on five pieces of silk, green, red, white, black and yellow respectively. Once the talismans have been planted in the bushels of rice, the Taoist draws a series of ‘true writs’ in the air, striking a sacred feudal contract with the spiritual powers of the cosmos, asking for the blessings of new life in spring, maturity and full crops in summer, rich harvest in autumn, and rest and security in the old age of winter. (The ‘Monthly Commands’ chapter of the Book of Rites (Li-Chi; Yüehling) reveals the Confucian origin of this Taoist rite. See [36].)

Union with the Tao

After the five elements have been ritually renewed in nature, the Taoist always completes the ritual cycle of rebirth by a special meditative prayer for bringing about union with the transcendent Tao. This ritual, the highlight of most temple liturgies practised in maritime China or wherever Chinese religion flourishes, is called the Tao-ch’ang (making the Tao present in the centre of the microcosm) or the Cheng-chiao (attaining true mystical union with the Tao). The ritual is the converse of the Su-ch’i described above. Having planted the five talismans in the five bushels of rice on the first day of the Chiao festival of renewal, on the last day the Taoist dances the sacred steps of Yü (playing the role of China’s Noah who stopped the floods of antiquity) and ‘harvests’ the talismans, one by one, ingesting them meditatively into the five organs within his body. The five organs (liver for east and wood, heart for south and fire, lungs for west and metal, kidneys for north and water, spleen/stomach for centre and union) act as a sort of divine mandala making the presence of the gestating Tao felt within the centre of the microcosm. The mystic experience of union with the Tao is thus taught by ritual performed in the village temple for the men and women of the village to see. What could not be taught by the theologian verbally is understood by the peasant through the visible expression of liturgical drama [32, last segment].

The theory of Chinese religion is, therefore, seen as an eternally cycling progress outward from the Tao to the myriad creatures, and returning to the Tao for renewal by the very process of the seasons in nature. By following the path of nature, humans attain eternal union. Ritual acts as a dramatic, non-verbal source of instruction for the laity in the Chinese religious system.

Confucian Virtue

Ritual is to Taoist cosmology as behavioural norms are to the Confucian ethic; just as the theory of Chinese religion is demonstrated in the liturgies of the Taoist Chiao festival, so the definitions of the Confucian ethic are drawn directly from the experience of the human encounter at the practical level of everyday experience. The Confucian norms for behaviour, written down in the spring of the ancient Chinese cultural system, are very much alive in the winter of the modern present. Li or respect, hsiao or family love, yi or mutual reciprocity among friends, jen, benevolence towards the stranger, and chung, loyalty to the state, are values deeply embedded in the hearts of the men and women of China, equally valid for mainland and maritime communities [23: LXVI].

Li is, like many Chinese characters, a symbol not limited by a single linear definition. The word means religious ritual as well as heartfelt respect, an attitude which is basic to the ego in approaching human relationships. The word reflects the virtue of the chuntzu, the man or woman of outgoing, giving nature, who imitates heaven in generous liberality, and like the great ocean conquers by ‘being low’, letting all things flow into its embrace [25, bk I: 62, 116, 257]. Hsiao is the virtue governing family relationships. Its definition embraces the love of children for parents and parents for children, making the family the very centre of Chinese social life. Yi represents the sense of deep commitment that friend must give to friend, and reciprocity governing the transactions of honest business. Jen, literally all the good things which happen when two humans meet, is best translated by the word ‘benevolence’, from a Latin root, bene-volens, meaning ‘wishing good things’ for others. The comment of tourists coming back from mainland China, ‘how kind everyone is’, reflects the modern sense of jen, welcoming the stranger (hao-k’o), for which the great cities of China were traditionally famous. Finally chung, the sense of loyalty to the reigning power of state, coupled with an immense sense of democratic vote or common decision at the village and community level, makes China one of the most stable cultural systems in human history [12].

The Cosmos

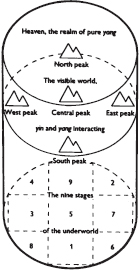

The yin – yang Five-Element theory governs not only the rituals of religious Taoism, but also the concepts of the present and the afterlife of the ordinary men and women of China. The principles of yang and yin, when joined together in harmonious union – often represented as a dragon and a tiger in a sort of cosmic struggle of gestation – form the visible earth. Separated, yang floats upwards to form the heavens, and yin sinks downwards to form the watery and fiery underworld [12: 42–8]. The three stages of the cosmos, heaven, earth and underworld, are reflected in the head, chest and belly of the microcosm (see figure 9.2). Upon death the soul, which has completed its life-cycle, is thought to sink downwards into the realms of yin, where it is purged of its darkness and sins for a period before release to the heavens [30]. During this period the soul can cause sickness in the family or other calamity if unattended by the prayers and food offerings of the living. The function of the medium, or shaman, in China as in Japan, Korea and South-East Asia, is to descend to the underworld (shaman) or act as a channel for the voice of the deceased (medium) to inquire about the needs of the unattended or sickness-causing soul. Buddhist ritual, especially, is thought to be efficacious in freeing the soul from the tortures of hell to ascend to the western heavens and paradise [13].

Figure 9.2 The spatial structure of the Chinese cosmos. Heaven is pure, separated yang; earth is the visible world, where yin and yang interact. The watery or fiery underworld is the realm of pure yin, divided into the nine sections of the magic square.

Hell

Hell is seen in the drawings of modern temple frescoes and devotional books to have nine cells or stages of punishment, each governed by a demon king [9]. The role of Buddhist and Taoist ritual is to lead the soul through these stages, paying off the evil politicians whose role in the afterlife, as in the present, is to tax and punish the common man and woman. In the Chinese system, only politicians stay eternally in hell, in charge of the tortures of the damned. The paper money burned at funeral and other rituals in China is symbolic of the merits of the living whose acts of love and giving are like banknotes in hell, drawing interest to free the souls of the deceased into eternal life [48].

Life-cycles

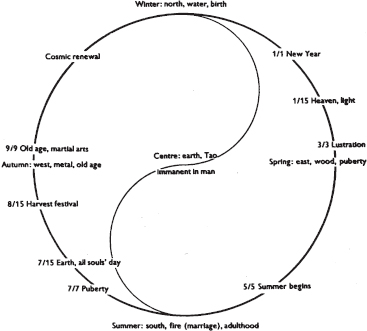

Figure 9.3 The temporal structure of the Chinese cosmos. Yang is born at the winter solstice, yin at the summer solstice. The human life-cycle and the annual cycle of festivals follow the same pattern.

Finally, the theory of cyclical growth and renewal is equally reflected in the annual cycle of festivals of the lunar almanac, and the cycle of life of humankind in the cosmos. Birth, maturation, marriage, old age and death in the cycle of life are reflected in the planting of spring, growth of summer, harvest of autumn, and old age or rest of winter (figure 9.3). The annual cycle of festivals liturgically celebrates these natural events of life, as explained below. Chinese religion is therefore eminently practical, integrating the individual into family and community, celebrating the passage of men and women through the cycle of life and of nature. Though the secular mind of the modern Chinese intellectual tends to deny the influence of the religious cultural system on the individual, the contemplative mystic of the Taoist and Buddhist community and the banquets of the common people of the Chinese community draw the politician and the academician into the joys of festive celebration.

Characteristic Practices of Chinese Religion

The Rites of Passage

Birth, maturation, marriage and burial have been regulated from the Han period onwards by the sumptuary and ritual law of the Confucian tradition.

Birth Birth is the least regulated of the life rituals. Tradition allows the pregnant mother a respite from unwanted labour before birth by placing taboos on excessive needlework, tying of bundles or bales, lifting, moving furniture, and other duties which by psychological or physical pressure may cause a miscarriage. The T’ai-shen or ‘foetus spirit’ is made ritual protector of the pregnant mother, a jealous deity who punishes any person harassing the parent before childbirth. Directions for the birth process itself prescribe a woman midwife or doctor to care for the mother in labour, and pay special attention to the disposal of the placenta. Strict custom decrees one month of rest for the mother after delivery, with special foods rich in protein and vitamins, and so forth, prepared by family members. The wife’s family must provide complete clothes, diapers and other necessary items on the first, fourth and twelfth months after the baby’s birth. Presents given to the child or the mother at this time, such as fresh eggs, specially prepared chicken, health wines or rice, symbolize good health and prosperity for both [41].

Maturation The elaborate ritual of ‘capping’ for the boy and ‘hair-styling’ for the girl, important events in traditional educated families in the past, have been more or less dropped in modern times. Some communities still celebrate the boy or girl going off to college, or commemorate the kuan maturation rituals as a part of the marriage festivities. Otherwise the rite of puberty, or maturation, is only celebrated in the more traditional families, and often only by a banquet in which a chicken is served to the young adult to commemorate approaching maturity [48].

Marriage Marriage in modern China of the diaspora is still a most elaborate affair, with the six stages observed in a fashion adapted from the traditional past. The stages or steps of Chinese marriage are as follows [16]:

Proposal, consisting in the exchange of the ‘eight characters’ – the year, month, day and hour of birth for both parties. The eight characters of the boy are placed by the family altar of the girl’s household, and any untoward event in the family during a three-day waiting period signals that the girl rejects the marriage.

Engagement is announced by the bride’s side sending out invitations for the auspiciously chosen wedding day, with a box of moon-shaped biscuits.

The bride’s dowry is sent to the groom’s home in a solemn procession through the streets. The entire community sees the gifts en route, and notes whether the bride’s vanity box is prominently displayed. The groom-to-be opens the vanity box with a special key, symbolizing that the love of the young couple is sincere. The bride-price is usually sent by the groom’s family, counted, and sent back at this time. The groom’s gifts to the bride, in the form of jewellery, clothes and other items, match the value of the dowry.

The bridal procession, formerly carried out by means of a bridal palanquin, now makes use of a limousine or taxi. The groom must go to meet the bride at her home, and accompany her back to his residence to the accompaniment of music, fireworks and streamers. On arrival at the groom’s home, the bride pretends to be weak as crossing the threshold she steps over a smoking hibachi or cooking-pot, a saddle and an apple at the gate, symbolizing (by homonyms) a pure and peaceful crossing into the new household.

The exchange of marriage vows frequently takes place in a Christian church in the modern setting. The bride and groom toast each other with a small cup of rice wine, and then proceed to an extensive banquet. During the banquet the bride and groom must toast each table of guests. Tea coloured to look like whisky is taken by the young couple, while each guest must swallow a complete glass of spirits. The traditional custom of reciting poetry and giving long speeches is frequently but not always shortened.

The morning after is celebrated by the young bride serving breakfast to her new parents-in-law, and in turn being served breakfast by them. A basket of dried dates and seeds is given to the new parents-in-law, a homonym for ‘many children’ (many seeds) from the bride. The bride returns home to her own parents ‘for the first time as a guest’ on the third day after marriage.

Burial Funeral rites in modern China of the diaspora may be extensive and costly, using Taoist and Buddhist forms as in the past, or completely Westernized in mortuary and church-burial form. Even when performed in a mortuary or church, certain aspects of the traditional rites of burial are observed, however, as noted in the following traditional account, taken from Chinese manuals [26].

The moment of death. When death occurs at home, or sometimes in a modern hospital, the dying person often asks to be put on the floor, as near as possible to the ancestor shrine in the main hall of the room. Death is signalled to the neighbours by wailing. The family immediately goes into mourning, by removing all jewellery and fine clothes, and dressing in coarse cloth, hemp or muslin, as custom decrees. The burial day is chosen, and invitations are sent out to all paternal relatives to the sixth degree, and all maternal relatives to the third degree, to attend the funeral.

Preparing the corpse and coffining. The corpse is washed ritually and put in a coffin. Layers of white paper money or talismans are put over the corpse, symbolizing purification and protection from harmful germs or baleful influences after death. Even when done in a mortuary with an open coffin, the custom of laying white paper talismans across the body of the deceased is observed. Mourning visitors put incense in the incense pot and offer the bereaved family condolences and money gifts to help meet the expense of a funeral. The family altar and all decorations in the front room are covered with white cloth during the entire funeral. Food and precious belongings are put into the coffin before the closing and sealing.

Mourning at home or in the funeral parlour. A Taoist or Buddhist priest, or a Christian minister (sometimes all three), is asked to perform the funeral ritual at home or in the funeral parlour. Paper houses containing complete furnishings, symbolic clothes and paper money for the bank of merits in hell are burned. The burning of paper signifies the merits of the living, and the prayers of the community for the eternal salvation of the deceased. Flowers, incense and paper items, funeral wreaths and a special ancestor shrine for the deceased are presented during the funeral rite.

The funeral procession. Chinese and Western bands, playing traditional and modern dirges, children portraying the twenty-four scenes of filial piety as burial drama, a willow branch symbolizing the soul of the deceased, and the entire mourning family accompany the coffin to the grave. All of the invited mourners pause before the cemetery, with only the immediate family and the officiating ministers or priests going to the grave-side. After burial the willow branch is carried back to the family altar and used ritually to ‘install’ the soul of the deceased in the memorial tablet. The ancestor shrine, less and less frequently seen in the families of maritime China, acts as a reminder to the living of the central place of family and its virtues of love and mutual care in the present life.

Post-funerary liturgies are performed for the deceased by Buddhist, Taoist or Christian ministers on the seventh, ninth and forty-ninth days after burial, and on the first and third anniversaries of death in a special manner. The Taoist rituals are especially colourful, depicting a journey of the Taoist high priest into the underworld where the demonic politicians of hell are tricked and cajoled into releasing the soul into paradise. A huge funerary banquet is provided for all guests, relatives and coffin-bearers who attended the funeral when the burial is completed.

Through much of the diaspora of maritime China, ancestor worship within the family has been supplanted by ancestor tablets which are kept for a fee at a Buddhist shrine, pagoda or temple. The altar in the main room of the traditional Chinese household, with the patron spirits of the family in the centre and the ancestor shrine on the left or ‘west’ side, is less and less frequently seen in Honolulu and South-East Asia. Education in Chinese religion at the college level, however, and the influx of Chinese from mainland China (who are, as a rule, more religious than those from secularized Taiwan or Hong Kong) tend to restore the practice of such traditional religious customs.

The Annual Cycle of Festivals

The festive cycle of Chinese religious life follows the farmer’s almanac, reflecting the busy time of the planting, weeding and harvesting process when religious festivals are relatively infrequent, and the rest periods when festivals predominate. Cyclical festivals fall in the odd-numbered or yang months, and farming activity in the even-numbered or yin (earth) months. The festivals are doubly symbolic, representing the progress of men and women through life as well as the ripening, harvesting and storing of crops. The calendar is followed enthusiastically by Chinese communities of the diaspora, and recognized cognately by mainland communities [3; 8; 33].

First (lunar) month, first day The lunar New Year, or festival of spring, is a family banquet in honour of the ancestors and the living members of the family who assemble from distant places to affirm identity. The New Year festival is the most important and widely celebrated of Chinese festivals today. Five or seven sets of chopsticks, wine, tea and bowls of cooked rice are laid out in memory of the ancestors on the family altar or table. Then a sixteen- or twenty-four-course banquet is served. Flowers, freshly baked cake, sweets, sweet dried fruit, three or five kinds of cooked meat, fish, noodles, bean curd, and various kinds of vegetable dishes, all with homophonic meaning for blessing and prosperity in the New Year, are served at the banquet. Women wear flowers in their hair, children receive presents and cash in a red envelope, new clothes are donned and fireworks signal the beginning of the first lunar month of spring. Good-luck characters are pasted by the door and the lintels, and visits made to friends, shrines and churches on New Year’s Day.

First month, fifteenth day This is the festival of light. The first full moon of the New Year is celebrated by a lantern procession and a dragon dance. Children carry fancy lanterns in the streets, and contests are held for the best lantern, best poems and best floats in the lantern parade.

Third month, third day The lustration festival is celebrated from the beginning of the third lunar month until 105 days after the winter solstice, in the fourth lunar month, as a sacrificial cleaning of the graves and the celebration of the bright and clear days of spring. The graves are cleaned and symbolically ‘roofed’ or covered with talismanic tiles, begging for blessing in spring. The family holds a picnic in the hills after offering food at the grave.

Fifth month, fifth day The beginning of summer is celebrated by the eating of tseng-tzu (rice cakes), by dragon boat races on the river and by rituals to keep children healthy and safe from the colds of summer. The colourful Taoist ritual exorcising the spirits of pestilence is seen throughout the coastal areas of south-east China and the diaspora.

Seventh month, seventh day The festival of puberty, or the seven sisters day, is celebrated throughout maritime China, Japan and the diaspora with the charming tale of the spinning-girl and the cowherd boy, whose eternal tryst is commemorated on this evening.

Seventh month, fifteenth day ‘All souls’ day’ or the Buddhist Ullambhana is celebrated throughout Asia as a pre-harvest festival. The souls are freed from hell in a ritual of general amnesty before the rice and other crops are harvested from the soil. As on New Year’s Day, the entire family celebrates with a banquet.

Eighth month, fifteenth day The full moon of autumn marks the harvest festival, celebrated with a banquet of fresh fruits and round mooncakes eaten under the rising harvest moon. Poetry reading and family evenings after the harvest express thanks for nature’s bounteous plenty.

The winter festivals From the ninth month, ninth day until the eleventh month, eleventh day, various festivals celebrate the autumn and the winter period of rest and recycling. The Taoist rite of cosmic renewal or Chiao is most frequently celebrated at this time, up until the winter solstice [37]. Besides the cyclical festivals, various birthdays celebrating the heroes or saints of the folk religion occur at even and odd month intervals throughout the year, according to local custom. These patron saints’ festivals include the festivals of the local patron saints of the soil, on the first and fifteenth day of each month; the Heavenly Empress Ma-tsu, who protects fishermen, sailors and immigrants, on the fourth month, twenty-third day; Kuan-kung, patron of merchants and martial arts, on the sixth month, fifteenth day; and Tz’u-wei the patron of the pole-star, on the ninth month, ninth day. Taoist, Buddhist and popular temples usually offer rituals on all festive occasions. The spirit of Chinese religion, ecumenic or irenic rather than syncretistic,1 moulds all religious systems to the needs of the people for ritual to celebrate the rites of passage.

Religious Functionaries

Three functionaries assist the people of the village in the practice of the rites of passage and the festivals. These are the Buddhist monk, the Taoist priest and the possessed medium or shaman. The Buddhist monk provides Pure Land-motivated chants, Ch’an (Zen) meditation and tantric, that is, mantric chant, mudra (hand gesture) and eidetic visualization2 as regular services in the local Buddhist monasteries. The majority of the temples (miao) of popular Chinese religion are ministered by Taoist priests under the direction of a lay temple board of directors. Taoists provide various rituals for healing and blessing, including the universally popular ritual asking blessing from Ursa Major, the constellation of the Pole Star. Both Buddhist and Taoist temples offer a modernized version of the method of prognostication of the yarrow stalk and I Ching book (that is, numbered wooden sticks are drawn from a wooden container by chance, and the corresponding hexagram is read by a monk or nun in the temple) for reading one’s fortune or common-sense advice in practical home and business matters. The temple or religious centre in the Chinese village is truly a cosmic as well as a cultural axis, providing fairs, opera, puppet shows, storytellers and meeting-places as well as religious services. As with the medieval cathedrals of Europe, the villagers build their own temples from local donations, and spend years, decades even, in making these cultural focal points into objects of artistic pride and functional meaning.

The medium, shaman and oracle are three different functionaries within the Chinese system, with a different word for each role. The medium, whose body is occupied by a spirit while in trance, the shaman, who travels into the afterlife, whether the underworld or the heavens, and the oracle, who speaks in the words of a bystanding spirit, fulfil the roles of seer, healer and keeper of justice in villages where the spiritual power of the temple and the religious system provides more stability than the rapidly changing political and industrial forces of change. The medium and the shaman have tended to multiply in those areas where political stability is repressive or lacking (such as Taiwan, Korea, the Philippines and South-East Asia) and practically to disappear where economic growth or strictly enforced political discipline is dominant, as in Japan or mainland China [45].

Conclusion

The power of the folk religion in modern China, whether in the diaspora or on the mainland, has not been destroyed but rather simplified and strengthened by modernization and political change. Proto-scientific systems such as feng-shui, or the placing of buildings to utilize the wind and the sun, and di-li or the placing of graves so as to preserve natural watersheds, are quite visible throughout maritime China. The festivals and their paraphernalia such as incense, paper money and paper clothes are still seen in the countryside and outlying areas of mainland China. Religion dies hard in modern Asian society because it is a vehicle for self-expression and cultural identity, giving the ego a firm place in family, society and nation. Just as the Chinese who have emigrated to South-East Asia and America are finding new meaning in asserting the festivals of the past, so the peasants and masses of mainland China will restore the celebrations of life’s cycle which give meaning to existence in a vital socialist society. Such a phenomenon is possible because religion is a cultural force in China, affirming and strengthening the smooth working of human relationships in the difficult struggle for survival in a hard-working peasant and industrial environment. Religion brings joy and meaning to the passage of life and death in a truly social context.

The Mystic Tradition in China

The Chinese mystic tradition is perhaps one of the most fascinating aspects of the study of Asian religion. From the early Taoist texts of the Lao-tzu and Chuang-tzu (Laozi and Zhuangzi, fifth to fourth centuries BCE) to late Ming dynasty (sixteenth century CE) forms of Ch’an (Zen) meditation that combined breathing techniques and Pure Land chant with sitting, Chinese ‘mystic’ writers have inspired more than two millennia of ascetic and monastic practice. The mystic tradition in China merits a separate detailed study, the basic elements of which are itemized below.

Mysticism is defined in the Taoist ascetic (hsiu-yang) tradition as the practice of ‘heart-mind fasting’ and ‘sitting in forgetfulness’. These two terms, taken from the Chuang-tzu Nei-p’ien, chapters 4 and 5, name the method for practising the emptying of the mind of all judgement and the heart of all desires, a requisite precondition for realizing the presence of the Transcendent Tao (Wu-wei chih Tao/Wuwei zhi Dao). The Western term for such a practice is kenosis, i.e. the emptying of the mind of conceptual imagery and judgement. The mind which does not judge can ‘hear the music of the Tao of Heaven’, in the words of the Chuang-tzu (Zhuangzi).

The Chuang-tzu Nei-p’ien (the first seven chapters of the Book of Chuang-tzu) distinguishes clearly between the wu ‘kataphatic’ possessed medium tradition and the ‘apophatic’ mystic. In the last lines of chapter 7, Chuang-tzu describes how the fledgling mystic Lieh-tzu goes in search of a master. He finds Hu-tzu, the ‘Empty Gourd’ Taoist on the top of a hill, and the wu trance medium/psychic Chi-hsien (Zixian). Chi-hsien is a popular healer, while Hu-tzu is a master of kenotic (emptying) prayer. Chi-hsien is taken by Lieh-tzu to meet the mystic ‘Empty Gourd’. Three encounters take place, after which (the fourth meeting) Chi-hsien flees and never comes back. The mystic (emptying all thoughts and images) and the psychic (filling the mind with images, resulting in spirit-possession) are two diametrically opposed traditions.

The prayer method of apophasis or kenosis invoked for mystic prayer is a simple technique without doctrinal or other religious content. It can be practised in any religious tradition, and is in fact found in many Western prayer systems.3 The methods of apophatic or kenotic prayer are very highly developed in both the Chinese Buddhist and Taoist traditions. They are described in simple-to-follow form in a number of well-known texts.

The first of these meditative texts is the well known Lao-tzu Tao-te Ching (Laozi Daode Jing), attributed to the mystic of the sixth/fifth centuries BCE, Lao-tzu (Laozi). The work is sometimes called ‘the 5,000 Character Book’ because its eighty-one brief chapters contain about that many Chinese written characters. The work is divided into two sections, the ‘Tao’ (Dao, Transcendent, unmoved gestator) and the ‘Te’ (De, the primordial first mover, seen as female ‘breath’ or primal energy). A second-century BCE version of the work was discovered at Ma Wang Tui (Mawangdui) in Hunan province in 1974. In this early version the ‘Te’ section of the book is placed first, and the ‘Tao’ last. This arrangement suggests the title ‘The Classic for Attaining the Tao (Way)’ i.e. the way of kenotic prayer that leads to union with the eternal Transcendent.4

Lao-tzu warns in the very first chapter of the Tao-te Ching that the conceptualization and verbalizing of the mystic experience is completely relative, if not impossible. One can use words to describe the infinite, such as ‘mysterious’ and ‘gateway to all mysteries’, but the experience itself is intuitive, beyond words. Yet the Tao-te Ching attempts to describe the experience of union with the Transcendent in terms of nature, using such symbols as water, wind, the empty hub of a wheel to describe what the words generated by intellectual judgement fail to convey.

Water is the best of all. Without contention,

It does good for all things.

It goes to the lowest place, that others avoid.

Because of this it is closest to Tao.

The simplicity of the Taoist way makes no distinction between the high and the lowly, is not elated by praise or discouraged by criticism. Possessions and wealth are things to be given away and a life of simplicity is to be pursued, because such a way of life is closest to Tao. It is only when mind and heart are freed from images and desires that the mystic can indeed be one with the transcendent Tao. Like the empty hub of a wheel, the mystic is centred on the Tao when intellect and will are unimpeded by the relative.

A thirty-spoked wheel has a single hub.

It is because its centre is empty

That it can be used on a cart.

Greatness is judged not by praise and acclaim, but by finding the lowest position, like water, which is closest to Tao.

The great river and ocean are the greatest

Of all creatures,

Because they are the lowest.

Thus all things flow into them.

Lao-tzu teaches that the person who is a true mystic, far from being an anti-social recluse, brings good to all who come in need of help. The success of the contemplative life is measured by the ability to give and to heal.

Be like Tao,

[Wu-wei, Transcendent Act]

Make little things important.

Requite anger with goodness.

Long ago Taoists took Goodness as their master,

Touched the subtle, wondrous mysteries of Tao …

Such as shivering when wading in a winter creek,

Careful not to disturb the neighbours,

Polite and thoughtful when invited as a guest,

Sensitive as ice beginning to melt;

Simple as an uncarved block of wood,

Unspoiled as a wild valley meadow,

Cleared of mud and silt like a placid pond.

One can only keep this kind of Tao

By not getting too full,

Staying new and fresh like sprouting grass.

Beauty for the mystic is found in the act of giving, just as Tao from an eternal unmoving first act gestates ‘one’, ‘two’, ‘three’ and all the myriad creatures. The mystic not only avoids argument and contention, but in the very act of emptying and giving does not put down or harm those who receive healing.

Words in contracts are not beautiful,

Beautiful words are not found in contracts.

Good people don’t dispute,

Disputes do not bring good.

Knowledge isn’t always wise.

Wisdom isn’t something learned.

The Taoist … finds joy in giving to others.

The more given, the more happiness.

Heaven’s Tao gives,

Without harm or discord.

The depth of Lao-tzu’s words is expanded and clarified by the humorous stories and wisdom of Chuang-tzu (Zhuangzi).5 Except for chapter 2, which is quite long, and chapter 3, which is short, the Nei-p’ien chapters are of even length, and move consistently through a series of humorous tales which describe a method of interior ‘emptying’ or kenosis.

Chapter 1 shows that the relative action of the great and the small must not be judged as good or bad. The great bird P’eng (a symbol of heaven/yang) flies for six months with one flap of the wings. The great fish Ao (water/yin) swims for six months with one flap of its tail. A small bird flies from the ground to a tree branch with many flaps of its wing. A small mouse needs many sips of water to fill its belly. The human mind judges one thing good and another bad on the basis of a relative judgement of size or accomplishment. The Taoist sage Lieht-zu learned to ride on the wind, while the sage of Mt Ku-yi (Guyi) could ascend to the clouds on a dragon. The accomplishments of one person do not make another person less good. True goodness is measured by the bringing of interior peace and blessing to all who come in contact with the Tao.

The second chapter, entitled ‘Abstain from Arguing about Things’,6 opens with the story of the sage Nan Guo-tzu Chi (Nanguozi Ji) who could make ‘the body like dry wood and the mind like ashes’, i.e. one with the Tao, by abstaining from all judgements. The simple rule for the meditation of union is to abstain from any sort of judgement, including good as well as bad. When verb is not put to noun, and the heart – mind is at peace, then the meditator can ‘hear the music of heaven’. Judgements are at any rate relative. The monkeys in a zoo were angry because the zoo-keeper gave them only three bananas in the morning, and four in the evening. So the zoo-keeper gave them four in the morning, and three in the evening. The monkeys were then quite happy. Winning or losing an argument does not make the winner correct or the loser wrong.

Once a Chinese princess was married by her father the king to a prince who lived in a far-off land. She cried and cried when leaving her home, but when arriving in her new kingdom she repented her tears. Her new life was filled with peace and happiness. For the Taoist, the entire cosmos is home. Eternity has already begun, and death is only a change of residence.

The fourth chapter teaches the Taoist meditative method called ‘heart-mind fasting’, that is, keeping the heart and mind focused on Tao’s presence in nature, and in the interior of the meditator, rather than on thoughts and judgements within the mind. This simple technique is achieved by focusing awareness on the ‘lower cinnabar field’, the centre of the physical body, rather than on thoughts in the mind or desires in the heart. The Tao’s presence is experienced in the body’s physical centre. Tao’s act of eternal gestation is seen, heard and felt with the intuitive powers of the belly rather than with the logical faculties of mind or the self-seeking powers of the will in the heart. The heart stops listening to the ears or the mind when it is focused on the Tao.

Only the Tao dwells in the void. Fasting in the heart means that the heart – mind is emptied, so that only the Tao may dwell there.

Keep the ears and eyes focused on the Tao within, so that the mind is not engaged in the human struggle for fame. Shut out all worldly knowledge and judgements, so that spirits and demons will not come and dwell inside.

The conviction that judgements and forces both inside and outside the human mind and body are spiritual energies that must be exorcised in order to be aware of Tao’s presence is essential to Taoist mysticism. To the fourth-century CE woman Taoist Wei Huacun is attributed the authorship of the Yellow Court Inner Chapters (Huang-t’ing Nei-ching).7 In this text of the later monastic ascetic Taoist tradition, the meditator is given the names of hundreds of spirits and their energies that reside in every crevice and section of the body’s microcosm, reflecting the spiritual energies of the outer cosmos.8 As in the Buddhist Tantric tradition, the meditator is taught to envision each spirit and send it out of the body, thus voiding the interior before the meditation of union with the Tao.

Chapter 5 uses the symbol of the Fu, the royal talisman of China’s ancient kingdoms, to explain the method of union with the Tao. In ancient China, kings and loyal courtiers swore fealty by breaking a jade seal in half. The king kept one half, and the duke, lord or marquis kept the other half. At the winter solstice festival the loyal knights returned to the king’s banquet table, and matched their talismans to those of the king, proving loyal service.

In the same manner, the Tao is the heavenly half of a talisman (Ling), and the meditator is the other half (Bao). When judgement is stopped, when the meditator ‘sits in forgetfulness’ (dzuowang), then the two halves of the talisman can be joined.9

The Tao-realized person is called in chapter 6 a Chen-jen (Zhenren), i.e. a ‘true person’. The meditation of ‘sitting in forgetfulness’ is described as follows:

My limbs do not feel, my mind is darkened

I have forgotten my body, and discarded my knowledge

By so doing, I have become

One with the Infinite Tao.

The final chapter, 7, tells two stories: (1) the story of Empty Gourd (related above) and (2) the story of Mr Hundun (the person united to the Tao) who did not have the five sense apertures of ordinary humans. Each day the Lord of the Southern Ocean (yang) and the Lord of the Northern Ocean (yin) came to play inside Hundun’s warm interior (i.e. the meditation of ‘heart – mind fasting’ and ‘sitting in forgetfulness’). They felt sorry for Hundun, and decided to give him the seven apertures of an ordinary human being: two eyes, two ears, two nostrils, and a mouth. Each day they drilled one hole. On the seventh day Hundun died.

So, too, meditation on the Tao’s presence dies when we fill our hearts and minds with judgements, and do not let go. The meditator must be like a mirror, not holding thoughts or worries inside: ‘The person who has touched the Tao uses the heart-mind like a mirror, not reaching out and grabbing, not holding on, responding, but not storing inside. Thus s/he can bring healing without harming self or others.’

The later Taoist religious tradition, which has developed from the second century CE up to the present, relies on these ideas for inspiration and enlightenment. All truly Taoist ritual is initiated by a meditation called Fa-lu in which the Taoist high priest (man and woman can equally perform this role) empties all of the spirits and images out of the heart – mind, before inviting the Transcendent Tao to be present. All of the spirits of the cosmos, including images of the Tao as gestating, mediating and indwelling, are exorcised or sent out of the body. A grand ‘mandala’ or cosmic design is constructed around the meditating Taoist. The spirits of the heavens are seen to be in the north, facing the Taoist (who stands with his/her back to the south). The spirits of yang (Blue Dragon, spring and summer) are in the east, to the right of the Taoist. The spirits of yin (White Tiger, autumn, winter) are to the west. The spirits of the water and underworld, the ‘orphan souls’ (images from the past filling the mind with worries) are left outside of the sacred temple or meditative area. These spirits of past memories, unrequited ancestors, all those who suffered because of the individual or the community offering prayer, are released from memory. These rites are enacted throughout the villages of south-east China, Taiwan, South-East Asia and Hong Kong in the modern period. (For a fuller explanation of the Taoist ritual process, see [33].)

The kenotic tradition is also preserved in modern Chinese and Tibetan Buddhist practice. It is to be found in three separate forms: (1) the combined Pure Land chant and Ch’an (Zen) meditations of the Chinese Buddhist monastery; (2) the practice by the laity of a popular form of Chih-kuan (Zhiguan), i.e. Samatha-vipassana centring meditation from the T’ien-t’ai Buddhist tradition; and (3) the Tibetan Tantric forms of mandala chant ritual and Dzog-chen sitting meditation.

The first of these methods, the Chinese form of Ch’an (Zen) which uses Pure Land chant (nianfuo) along with quiet sitting meditation in the lotus position, can be found in most traditional Buddhist monastic centres. Monks and nuns on Mt Chiu-hua (Jiuhua Shan) in Anhui province, the Xixia monastery outside of Nanjing, and a great number of mountain retreats in Fujian and Gwangdong provinces continue to practise and transmit the teachings of the traditional Chinese Ch’an tradition. The chanting of the Amida Sutra, the Heart Sutra, the P’u-men P’in chapter (26) of the Lotus Sutra, the Great Compassion Sutra, and other traditional texts are combined with daily sitting in the dhyana or vipsyana, with the mind focused on the Hsia Tan-t’ien (xiadantian) or ‘lower cinnabar’ region, about three inches below the navel and three or so inches within. The laity who attend Buddhist temple services on the first and fifteenth of each lunar month, days which the government has declared to be officially sanctioned for Buddhist services, spend a great part of the morning listening to the monks and nuns chant sutras, a practice which the Buddhist monks say is a more sure and expedient way to attain ‘mind and heart emptying’ than sitting meditation. The laity as well as most monks set more store by Pure Land chant than by ‘sitting’. The older Buddhist masters teach their modern disciples that this latter practice, if done without a spiritual guide, can lead to pride, distractions, and self-aggrandizement.

A second popular form of emptying meditation is practised by a widespread lay movement in modern China. A great number of private lay masters teach a form of zhiguan or ‘centring’ prayer based on the Greater and Lesser Vipassana sutras, i.e. the Ta Chih-kuan (Da Zhiguan) and Hsiao Chih-kuan (Xiao Zhiguan) healing texts of the T’ien-t’ai (Tiantai) tradition. This phenomenon is found everywhere in modern China, and is not limited to Buddhist texts. Pseudo-Taoist Ch’i-kung (Qigong) masters and self-styled Buddhist zhiguan experts are so numerous that government attempts to control their spread (sometimes by arresting popular leaders and forbidding unapproved public Qigong demonstrations) have been ineffective. The majority of such masters and their followers are often quite highly motivated. No fees are asked for the transmission of meditative teachings. The goal of the teacher and of the meditator is for the most part healing rather than the pure meditation of emptying. The purpose of learning Vipassana or Qigong meditation is almost always to heal some illness. Men and women who are accomplished masters must be able to free themselves and their followers from illness.

The third form of kenotic prayer practised widely throughout Tibet and parts of Mongolia, Gansu, Qinghai, Szechuan and Yunnan provinces is Tantric Buddhism. This powerful form of visualization and emptying through the use of mudra, mantra and mandala meditation is based firmly on the philosophy of Madhyamaka, the ‘empty’ middle way. The Tantric method of prayer is totally non-judgmental, freeing the mind from conceptual images and the will from any form of assent or denial. Whereas Ch’an (Zen) sitting focuses on emptying the mind, and Pure Land chant on purifying the devotional heart, Tantric prayer uses mind to contemplate (mandala), mouth to chant (mantra) and body and hands to dance (mudra) in a form of total bodily kenosis. Tantric prayer in its Tibetan form achieves kenosis by overload, i.e. by visualizing such powerful sacred images that the mind is no longer drawn by any form of judgement or the heart by desires. The state of absolute detachment elicited by the stark beauty of the Tibetan highlands that gave birth to this unique form of prayer changed warlike Tibet and Mongolia into nations whose cultures became focused on prayer and devotion, rather than war and conquest. Up to the present Tibet rejects the modernization imposed by the polluting Han Chinese socialist technocracy in favour of the spiritual abundance of a simpler form of life based on pastoral nomads, quiet farming and Tantric meditation.

The above is only a brief summary of a marvellously rich tradition. Many excellent works exist in English that can assist the reader to learn more of Ch’an (Zen) meditation, Pure Land chant and Tantric contemplation. Modern bookshops are filled with treatises on and translations of Buddhist prayer. Fewer works are available on the Taoist tradition of kenosis, due to what is conceived as ‘Taoist’ in Western book markets rather than to the reality of Taoist practice in China. Though there are many translations of the Laozi and Zhuangzi, treatises on Taoist liturgical prayer in English are less well known. The opening of China to the modern world since 1960 has begun to alleviate this situation. (For an excellent bibliography of Taoist literature, see [4]; for descriptions of Taoist ritual, see [33]; for a detailed bibliography on every aspect of Buddhism, Taoism and popular religion up to the early 1980s, see [43].)

Religion in Modem China

Perhaps one of the most volatile and unpredictable areas in modern Chinese life is the status of religion under ‘socialism with a special Chinese flavour’. After the opening of China to Western investment and economic progress in 1979–80, the enlightened policies of Deng Xiaoping have brought about a certain amount of freedom of religious practice in China, which was again curtailed to some extent after the democracy movement and demonstrations in Tiananmen Square in May – June 1989.10 The condition of religion in China from June 1989 to 1996 is quite different from the period 1980–9.

The opening of China to the market economy in the early 1980s brought with it, in Deng Xiaoping’s words, ‘files and insects’, i.e. a certain amount of religious freedom, which was seen as unavoidable with the coming of free markets, private small businesses and individual enterprise. Scholars of the Academy of Social Sciences were quick to point out that the restoration of the ‘freedom of religion’ clause allowed by the first Chinese socialist constitution constituted an improvement in Chinese social and cultural values. Surveys done by the Academy between 1984 and 1988 showed that where religion was practised, ‘production was high, divorce was low, family values were maintained, and loyalty to the state and its principles upheld’ [33: 193–212]. The survey of religion published by the Shanghai branch of the Academy of Social Sciences, entitled The Religious Question in the Socialist Era [31],11 pointed out that religion in China could no longer be called the ‘opiate of the people’ because socialist China no longer had a capitalist class which could use religion as a tool to oppress the proletariat. Religion for the Chinese was for the most part a festive rather than a doctrinal system.

The five great religions officially recognized by the Chinese state are the Buddhist, Taoist, Islamic, Catholic and Protestant faiths. Monks, priests, ministers and mullahs from each of these traditions are educated at state expense in state-constructed and subsidized seminaries. In spite of the official attitude of the state and the Communist Party to religion, the Marxist – Leninist principle of the ‘united front’ (i.e. the unifying of party goals with religious faiths) is used as the guiding principle for handling religious questions in China. Since 1980 the re-promulgation of ethnic minority as well as religious rights has inspired a more open attitude towards religious belief and practice in China. The fact that religious rights are seen as analogous to ethnic minority rights has brought about both an opening and a restricting of religious practice at the official level. To understand this phenomenon, it is necessary to examine each of the religious traditions as a separate entity, since the state and the Party handle each religion in a different fashion.

The first and most obvious area of scholarly study and state – Party concern is with Islam in China. The Yuan dynasty (1261–1365) policy of using Islamic and other minorities to govern the Han Chinese brought a huge influx of Arab, Persian, Turkish and other military officials into thirteenth- and fourteenth-century China. These Yuan-sponsored officials for the most part married Han Chinese women, and became a separate ethnic group (of multi-ethnic origin) classified as Hui i.e. of Islamic origin, in China. The Ming dynasty (1365–1644) did not employ this diverse ethnic group in the capacity of civil officials, but continued to use the Hui as military experts. The Qing (Ch’ing) dynasty, on the other hand, discriminated against and completely eliminated the Hui from all posts, civil or military, causing great unrest among Islamic peoples in China, which resulted in uprisings, wars and massacres during the foreign (Manchu) Qing rule. An enlightened socialist China decided after the 1980 reforms to allow a certain amount of autonomy for all of the Islamic areas in China, built seminaries and schools that taught the Qur’an, Islamic, Arabic and Iranian studies, and trained mullahs at state expense. This policy was implemented not only for the Hui minority, a term used to name people of Islamic belief or descent in such widely separate places as Yunnan, Hunan, Fujian, Shandong, Beijing, Gansu and Ningxia (a Hui autonomous region), but also among the Uighur, Khazak, Salah (an immigrant Islamic group coming to Qinghai province from Samarkand during the Yuan dynasty), Bao’an and other Islamic minorities. These groups are remarkable for their maintaining of ancient divisions, such as the ‘loud’ and ‘quiet’ method of reading the Qur’an, Sufi, Sunni and even Shi’a beliefs (such as among the Kirgiz ethnic group of Persian origin). Ties between the Islamic groups of China and the Middle Eastern Islamic nations are close. The Chinese government grants travel permits for the annual pilgrimage to Mecca.

Buddhism is also a very obvious area of concern in and support by official state policy. The Buddhist Studies Association supports the restoration of Buddhist shrines, the gathering of immense financial profit from tourism to Buddhist sacred places, and the education of Buddhist monks and nuns to staff chosen monastic and temple environments in places of popular devotion throughout China. Great Buddhist centres such as Putuo Shan, with its devotion to Guanyin (Avalokiteshvara; symbol of compassion), Jiuhua Shan (and its shrine to Dizangwang, Ksitigharba; symbol of salvation from suffering), Xixiashan outside Nanjing, Omei Shan, Wutai Shan and other great centres have continued the tradition of Ch’an meditation, Pure Land Chant, and popular devotion including the rites of zhaodu: praying for the ascent of deceased souls from Buddhist purgatory to the Pure Land.

Tibetan Buddhism is a special case, because of the delicate question of Tibetan cultural and religious independence as against complete political separation, which the Chinese government does not consider to be a question open to discussion. For this extremely sensitive reason, the rebirth of Tibetan religion, with the flocking of monks and nuns to traditional monasteries, the rebuilding of the great temples (destroyed completely during the Cultural Revolution) and immense numbers of pilgrims turning prayer wheels, circumambulating and prostrating in the old fashion, makes Tibet, Qinghai, Gansu, Yunnan and western Szechuan (which comprised the ancient Tibetan kingdom) appear to have undergone an almost complete restoration of the traditional religious system. The Jhokang temple in Lhasa, Drepung, Kumbun, Labrang, Rongwo and other great monasteries have restored the ‘living Buddha’ tradition of the past. Foreign visitors to Tibet are everywhere asked for pictures of the Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibet and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, now in exile in India. The revival of religion in all Tibetan-speaking areas is found among old and young alike.

Taoism is the least noticed of China’s traditional religious systems, due to the rigours of the celibate monastic life and the long years of training required for popular Taoist priests who perform the rites of passage for China’s villages and cities. The state keeps a close watch over Taoist mountains, collecting fees from tourists and pilgrims who come to these famous sacred shrines. Taoists are trained at the state-run White Cloud monastery (Baiyun Guan) in Beijing, in the Quanzhen (Ch’uan-chen) style rather than the more traditional liturgies of the Celestial Master, the meditations of the Shangqing (Shang-ch’ing) and the popular rites of the Lingbao (Ling-pao) traditions. (For a more detailed description of these various Taoist schools, see [4; 33; 43].) The great Taoist centres of Mao Shan, Lunghu Shan, Qingcheng Guan, Wudang Shan and many others have been restored and support communities of Taoists in their scenic environs. Popular ‘fireside’ (married) Taoist priests who act as ritual experts for villages and cities are found throughout Fujian, Zhejiang, Gwuangzhou, Zhiangxi, and other south-eastern provinces.

Christianity in its Protestant and Catholic forms has registered the greatest growth of any of the religions of modern China. Candidates flock to seminaries, where they are educated at state expense. Political control over the Protestant faith is maintained by an internal organization called the ‘Three Self’ movement, while Catholics are carefully watched by the ‘Patriotic Association’ (Aiguohui). Though this latter state-sponsored group has officially declared itself a schismatic church, not recognizing papal authority in Rome, in fact all of the faithful, almost all of the priests and more than 70 per cent of the state-appointed bishops do recognize the authority of Rome. Belonging to the Patriotic Association for most of the clergy is simply a means of being allowed some form of religious freedom. A good number of Catholics and Protestants, however, maintain an ‘underground’ church, that does not accept any form of activity classified as ‘United Front’ by the state. The underground churches have been officially declared illegal, and their members are arrested and gaoled when their activities become public. In spite of such difficulties, Christianity in China flourishes as it never did under the dominance of the foreign missionary in the past. More people attend churches in China than in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, or city parishes in the United States and Europe.

Three separate bodies of officials watch over religious growth in China. The highest of these is the United Front Association (Tongjanbu), the official Party organ. The second is the Religious Affairs Bureau, nominally a local or provincial organization with headquarters in the central government in Beijing. In fact the majority of the Religious Affairs Bureau officials are Communist Party members dedicated to the eventual elimination of religion in the perfected socialist state of the future. There is however a small body of dedicated cadres who in fact work for the freedom and growth of religion in China. Finally, each of the five religious groups has a control organ working from within: the above-mentioned ‘Three Self’ Christians, the ‘Patriotic’ Catholics, and the Buddhist, Taoist and Islamic Studies associations. Within each of these groups, Party, state, and religious body, are dedicated men and women who see religion in China as part of its cultural heritage, and thus, in spite of opposition, work for its growth and smooth functioning within the market economy and increasingly consumer-oriented society of ‘socialism with a special Chinese flavour’. In fact, the number of people practising religion of some sort is approximately equivalent to the number of Party members in China, each standing at 6 per cent of the population. In one of his last addresses, Zhou Enlai predicted that ‘religion would be present for at least the next 200 years in China’. The prediction of the insightful Premier, as in so many other instances, is proving to be correct.

Notes

1 ‘Irenic’ signifies an attitude of peace and acceptance towards other people and their ideas, stemming from the self. ‘Ecumenic’ connotes a positive effort to understand points held in common between two opposing religious systems. Thus, to the Chinese, Buddhism is a system for the afterlife, Taoism for the present (natural) life and Confucianism for moral virtue. The self is inwardly irenic, outwardly ecumenic with regard to the three religious teachings. There can never be an ecumenism of dogma, only of religious experience.

2 ‘Eidetic visualization’ means the constructing of an imaginative picture of the Taoist heavens, the arrival of Taoist spirits, or other imaginative contemplations rather in the style of the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises known in Western Christian terms. ‘Eidetic’ means that the outlines of the meditation are drawn by the classical text, while the meditator himself or herself fills in the outlines with a complete devotional experience of the text. Thus the eidos or substantial form of the meditation is fixed by custom, whereas the qualitative or devotional aspects are determined by the meditator.

3 The ‘dark night of the soul’ and ‘dark night of the senses’, terms found in the writings of the Western mystics Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross, are examples of apophatic or kenotic forms of prayer. Also included within this tradition are the works of the Pseudo-Dionysius, the Cloud of Unknowing, and Meister Eckhardt. Though the analogy between these forms of Western mystic prayer and the Buddhist Taoist tradition in China have often been pointed out by scholars and mystics in Asia and the West, official church authorities, Protestant and Catholic alike, have been slow in recognizing the significance of inter-religious prayer and dialogue.

4 There are many excellent translations of both versions of the text. The standard works of D. C. Lau are an excellent introduction. The romanization of Chinese characters used here includes the Wade – Giles as well as the modern Pinyin, where both forms seem helpful.

5 The first seven chapters of the Chuang-tzu, called the ‘Inner Chapters’ (Chuang-Tzu Nei-p’ien), are thought to be the most authentic part of the thirty-three-chapter text.

6 The chapter is also called ‘Making All Things Equal’. The Chinese Zhi wu lun, ‘Equalizing Discourse on Things’, or an alternative reading, ‘Zhai Wulun’ (‘Abstention from Arguing about Things’), have the same meaning.

7 Note that the Inner Chapters of the Chuang-tzu and the Inner Chapters of the Yellow Court Canon both contain the basic directions for the practice of mystic contemplation; the Chuang-tzu teaches the exorcism of judgement, while the Yellow Court Canon’s Inner Chapters teach the exorcism of all images and spiritual energies from the mind and body.

8 The head, chest and belly of the meditator are seen to respond to heaven, earth and the underworld in the macrocosm. Taoist ritual also uses this meditative method [33].

9 Note that the term Ling-pao (Lingbao) used in religious Taoist ritual preserves this meaning. The Taoists use talismans in ritual to join heaven and earth, humans with the Tao of Transcendence. The talisman must not be seen as a superstitious fetish, but as a sign of meditative process practised by the Taoist, that preceded the act of public ritual. In a deeper sense, Tao is the heavenly or Ling half of the talisman, and Te (of the Tao-te Ching) is the earthly or human half, the Bao.

10 The official term used for the incident of 4 June 1989, dongluan, ‘political disturbance’, reflects the psychological turmoil caused by the students and others during the events of May – June 1989. The officially recognized causes of the Tiananmen incident are attributed to foreign influence, especially on the students of Beijing who participated in the demonstrations. The demise of socialism in the USSR and the dissolution of the Soviet Union is officially attributed to the freedom of religion allowed by Moscow in the 1980s. Much of the freedom of religion allowed by the Chinese government during the 1980s has been subtly curtailed during the early 1990s.

11 An edition of 8,000 volumes sold out within the first month of publication, and has not yet appeared in a second printing.

Bibliography

1 AHERN, E., The Cult of the Dead in a Chinese Village, Stanford, Stanford University Press, 1973

2 BODDE, D., Festivals in Classical China, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1975

3 BODDE, D. (ed. and tr.), Li-Chen Tun, Annual Customs and Festivals in Peking, as Recorded in the Yen-ching Sui-shih-chi, 2nd edn, Hong Kong University Press, 1965

4 BOLTZ, JUDITH, A Survey of Taoist Literature, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1986

5 Cheng-t’ung Tao-Tsang and Wan-li Tao-tsang, Ming dynasty versions of the Taoist canon, are reprinted in Taiwan and readily available for library and private use: e.g. Taipei, I-wen Press, 1961

6 Complete Home Rituals (Chia-li Ta-ch’eng), Hsinchu, Chu-lin Press, 1960. This and similar volumes are found throughout maritime China, as popular summaries of the works cited in item 25 below.

7 DORÉ, H., Researches into Chinese Supersititions (tr. M. Kennelly et al.), 13 vols, Shanghai, T’usewei, 1914–; repr. Taipei, Ch’eng Wen, 1966

8 EBERHARD, W., Chinese Festivals, Taipei, 1964; prev. publ. New York, H. Schuman, 1952; London/New York, A. Schuman, 1958

9 EBERHARD, W., Guilt and Sin in Traditional China, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1967

10 EBERHARD, W., The Local Cultures of South and East China (tr. A. Eberhard), Leiden, Brill, 1968

11 FÊNG, YU-LAN, A History of Chinese Philosophy (tr. D. Bodde), 2 vols, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1952–3

12 FÊNG, YU-LAN, A Short History of Chinese Philosphy (tr. and ed. D. Bodde), New York, Macmillan, 1962; prev. publ. 1948