Endnotes

Preface

1. Paul Dirac, Nature, 126, 1930, pp. 605–6, quoted in Helge Kragh, Dirac: A Scientific Biography, Cambridge University Press, 1990, p. 97.

2. Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes, Bantam Press, 1988, p. vi.

Chapter 1: The Quiet Citadel

1. Lucretius, On the Nature of the Universe, trans. R.E. Latham, Penguin Books, London (first published 1951), pp. 61–2.

2. Recent X-ray studies have revealed that these papyri were written using metal-based inks, contradicting previous wisdom and offering prospects for optimizing computer-aided tomography of unrolled scrolls. See Emmanuel Brun, Marine Cotte, Jonathan Wright, et al., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113 (2016), pp. 3751–4.

3. Epicurus wrote: ‘To begin with, nothing comes into being out of what is non-existent.’ Epicurus, letter to Herodotus, reproduced in Diogenes Laërtius, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, Book X, 38, trans. Robert Drew Hicks, Loeb Classical Library (1925), http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Lives_of_the_Eminent_Philosophers.

4. Or as Lucretius put it: ‘The second great principle is this: nature resolves everything into its component atoms and never reduces anything to nothing.’ Lucretius, On the Nature of the Universe (n 1), p. 33.

5. As Epicurus explains: ‘And if there were no space (which we call also void and place and intangible nature), bodies would have nothing in which to be and through which to move, as they are plainly seen to move. Beyond bodies and space there is nothing which by mental apprehension or on its analogy we can conceive to exist.’ Epicurus, letter to Herodotus (n 3), Book X, 40.

6. Lucretius wrote: ‘Granted that the particles of matter are absolutely solid, we can still explain the composition and behaviour of soft things—air, water, earth, fire—by their intermixture with empty space.’ Lucretius, On the Nature of the Universe (n 1), p. 44.

7. See Plato, Timaeus and Critias, Penguin, London (1971), pp. 73–87. Plato built air, fire, and water from one type of triangle and earth from another. Consequently, Plato argued that it was not possible to transform earth into other elements.

8. Lucretius wrote: ‘It can be shown that Neptune’s bitter brine results from a mixture of rougher atoms with smooth. There is a way of separating the two ingredients and viewing them in isolation by filtering the sweet fluid through many layers of earth so that it flows out into a pit and loses its tang. It leaves behind the atoms of unpalatable brine because owing to their roughness they are more apt to stick fast in the earth.’ Lucretius, On the Nature of the Universe (n 1), pp. 73–4.

9. In The Metaphysics, Aristotle wrote: ‘They [Leucippus and Plato] maintain that motion is always in existence: but why, and in what way, they do not state, nor how is this the case; nor do they assign the cause of this perpetuity of motion.’ Aristotle, The Metaphysics, Book XII, 1071b, trans. John H. McMahon, Prometheus Books, New York (1991), p. 256.

10. Lucretius wrote: ‘Since the atoms are moving freely through the void they must all be kept in motion either by their own weight or on occasion by the impact of another atom.’ Lucretius, On the Nature of the Universe (n 1), p. 62.

11. Lucretius, On the Nature of the Universe (n 1), p. 66.

12. Lucretius again: ‘Indeed, even visible objects, when set at a distance, often disguise their movements. Often on a hillside fleecy sheep, as they crop their lush pasture, creep slowly onward, lured this way or that by grass that sparkles with fresh dew, while full-fed lambs gaily frisk and butt. And yet, when we gaze from a distance, we see only a blur—a white patch stationary on the green hillside.’ Lucretius, On the Nature of the Universe (n 1), p. 69.

13. Lucretius concluded: ‘It follows that nature works through the agency of invisible bodies.’ Lucretius, On the Nature of the Universe (n 1), p. 37.

14. Lucretius certainly thought so: ‘Observe what happens when sunbeams are admitted into a building and shed light on its shadowy places. You will see a multitude of tiny particles mingling in a multitude of ways in the empty space within the light of the beam, as though contending in everlasting conflict … their dancing [of the particles in the sunbeam] is an actual indication of underlying movements of matter that are hidden from our sight. … You must understand that they all derive this restlessness from the atoms.’ Lucretius, On the Nature of the Universe (n 1), pp. 63–4.

15. Democritus, in Hermann Diels, Die Fragmente von Vorsokratiker, Weidmann, Berlin (1903), 117, p. 426. The German translation is given as: ‘In Wirklichkeit wissen wir nichts; denn die Wahrheit liegt in der Tiefe.’ The quoted English translation is taken from Samuel Sambursky, The Physical World of the Greeks, 2nd edn, Routledge, London (1960), p. 131.

Chapter 2: Things-in-Themselves

1. Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason (see Sebastian Gardner, Kant and the Critique of Pure Reason, Routledge, Abingdon, 1999, p. 205).

2. The authors of the entry on medieval philosophy in the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy put it rather succinctly: ‘Here is a recipe for producing medieval philosophy: Combine classical pagan philosophy, mainly Greek but also in its Roman versions, with the new Christian religion. Season with a variety of flavorings from the Jewish and Islamic intellectual heritages. Stir and simmer for 1300 years or more, until done.’ Paul Vincent Spade, Gyula Klima, Jack Zupko, and Thomas Williams, ‘Medieval Philosophy’, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Spring 2013, p. 4.

3. ‘We should then be never required to try our strength in contests about the soul with philosophers, those patriarchs of heretics, as they may be fairly called.’ Tertullian, De Anima, Chapter III, translated by Peter Holmes, http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/tertullian10.html.

4. Boyle wrote: ‘To convert Infidels to the Christian Religion is a work of great Charity and kindnes to men’, in J.J. MacIntosh (ed.), Boyle on Atheism, University of Toronto Press (2005), p. 301.

5. René Descartes, Discourse on Method and The Meditations, trans. F.E. Sutcliffe, Penguin, London (1968), p. 53.

6. Descartes wrote: ‘And indeed, from the fact that I perceive different sorts of colours, smells, tastes, sounds, heat, hardness, etc., I rightly conclude that there are in the bodies from which all these diverse perceptions of the senses come, certain varieties corresponding to them, although perhaps these varieties are not in fact like them.’ Descartes, ibid., p. 159.

7. Locke wrote: ‘For division (which is all that a mill, or pestle, or any other body, does upon another, in reducing it to insensible parts) can never take away either solidity, extension, figure, or mobility from any body. … These I call original or primary qualities. … Secondly, such qualities which in truth are nothing in the objects themselves but powers to produce various sensations in us by their primary qualities, i.e. by the bulk, figure, texture, and motion of their insensible parts, as colours, sounds, tastes, &c. These I call secondary qualities.’ John Locke, Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Book II, Chapter VIII, sections 9 and 10 (first published 1689), ebooks@Adelaide, The University of Adelaide, https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/l/locke/john/l81u/index.html.

8. Berkeley wrote: ‘They who assert that figure, motion, and the rest of the primary or original qualities do exist without the mind … do at the same time acknowledge that colours, sounds, heat cold, and suchlike secondary qualities, do not. … For my own part, I see evidently that it is not in my power to frame an idea of a body extended and moving, but I must withal give it some colour or other sensible quality which is acknowledged to exist only in the mind. In short, extension, figure, and motion, abstracted from all other qualities, are inconceivable. Where therefore the other sensible qualities are, there must these be also, to wit, in the mind and nowhere else.’ George Berkeley, A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge, The Treatise para. 10 (first published 1710), ebooks@Adelaide, The University of Adelaide, https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/b/berkeley/george/b51tr/index.html.

Chapter 3: An Impression of Force

1. The full quotation reads: ‘The alteration of motion is ever proportional to the motive force impressed; and is made in the direction of the right line in which that force is impressed. … And this motion (being always directed the same way with the generating force), if the body moved before, is added to or subducted [i.e. subtracted] from the former motion, according as they directly conspire with or are directly contrary to each other; or obliquely joined, when they are oblique, so as to produce a new motion compounded from the determination of both.’ Isaac Newton, Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, first American edition trans. Andrew Motte, Daniel Adee, New York, 1845, p. 83.

2. See, e.g., Catherine Wilson, Epicureanism at the Origins of Modernity, Oxford University Press, 2008, especially pp. 51–5.

3. Newton wrote: ‘The extension, hardness, impenetrability, mobility, and vis inertia of the whole, result from the extension, hardness, impenetrability, mobility, and vires inertia of the parts; and thence we conclude the least particles of all bodies to be also all extended, and hard and impenetrable, and moveable, and endowed with their proper vires inertia.’ Newton, Mathematical Principles (n 1), p. 385. In this quotation, vis inertia simply means ‘inertia’, the measure of the resistance of a body to acceleration (‘vis’ means force or power). Newton then equates the inertia of an object to the sum total—the vires inertia—of all its constituent atoms (‘vires’ is the plural of ‘vis’).

5. The first law is given in the Mathematical Principles as: ‘Every body perseveres in its state of rest, or of uniform motion in a right line [straight line], unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impressed thereon.’ Newton, ibid., p. 83.

6. Newton wrote: ‘An impressed force is an action exerted upon a body, in order to change its state, either of rest, or of moving forward uniformly in a right line. This force consists in the action only; and remains no longer in the body, when the action is over. For a body maintains every new state it acquires, by its vis inertiae only. Impressed forces are of different origins as from percussion, from pressure, from centripetal force.’ Newton, ibid., p. 74.

8. Suppose we apply the force for a short amount of time, Δt.* This effects a change in the linear momentum by an amount Δ(mν). If we now assume that the inertial mass m is intrinsic to the object and does not change with time or with the application of the force (which seems entirely reasonable and justified), then the change in linear momentum is really the inertial mass multiplied by a change in velocity: Δ(mν) = mΔν. Applying the force may change the magnitude of the velocity (up or down) and it may change the direction in which the object is moving. Newton’s second law is then expressed mathematically as FΔt = mΔν: impressing the force for a short time changes the velocity (and hence linear momentum) of the object. Now this equation may not look very familiar. But we can take a further step: dividing both sides of this equation by Δt gives F = mΔν/Δt. The ratio Δν/Δt is the rate of change of velocity (magnitude and direction) with time. We have another name for this quantity: it is called acceleration, usually given the symbol a. Hence Newton’s second law can be re-stated as the much more familiar F = ma, or Force equals Inertial mass × Acceleration.

9. Newton states the third law thus: ‘To every action there is always opposed an equal reaction: or the mutual actions of two bodies upon each other are always equal, and directed to contrary parts.’ Newton, Mathematical Principles (n 1), p. 83.

10. Mach wrote: ‘With regard to the concept of “mass”, it is to be observed that the formulation of Newton, which defines mass to be the quantity of matter of a body as measured by the product of its volume and density, is unfortunate. As we can only define density as the mass of a unit of volume, the circle is manifest.’ Ernst Mach, The Science of Mechanics, quoted in Max Jammer, Concepts of Mass in Contemporary Physics and Philosophy, Princeton University Press, 2000, p. 11.

11. These quotations are derived from H.W. Trumbull, J.F. Scott, A.R. Hall, and L. Tilling (eds), The Correspondence of Isaac Newton, Cambridge University Press, Vol. 2, pp. 437–9, and are quoted in Lisa Jardine, The Curious Life of Robert Hooke: The Man Who Measured London, Harper Collins, London, 2003, p. 6.

12. Newton wrote: ‘That the fixed stars being at rest, the periodic times of the five primary planets, and (whether of the sun about the earth or) of the earth about the sun, are in the sesquiplicate proportion of their mean distances from the sun.’ Newton, Mathematical Principles (n 1), p. 388. ‘Sesquiplicate’ means ‘raised to the power 3⁄2’.

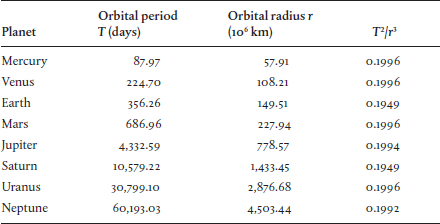

13. Only six planets were known in Newton’s time, but we can now extend Kepler’s logic to eight planets as follows:

For sure, there is some variation in the ratio T2/r3, but the deviation from the mean value of 0.1984 is never greater than two per cent.

14. Proposition VII states: ‘That there is a power of gravity tending to all bodies, proportional to the several quantities of matter which they contain.’ Newton, Mathematical Principles (n 1), p. 397.

15. Proposition VIII states: ‘In two spheres mutually gravitating each towards the other, if the matter in places on all sides round about and equi-distant from the centres is similar, the weight of either sphere towards the other will be reciprocally as the square of the distance between their centres.’ Newton, Mathematical Principles (n 1), p. 398.

16. Newton wrote: ‘Hitherto we have explained the phænomena of the heavens and of our sea, by the power of Gravity, but have not yet assigned the cause of this power. … I have not been able to discover the cause of those properties of gravity from phænomena, and I frame no hypotheses.’ Newton, Mathematical Principles (n 1), p. 506.

* We use the Greek symbol delta (Δ) to denote ‘difference’. So, if we apply the force at some starting time t1 and remove it a short time later, t2, then Δt is equal to the time difference, t2– t1.

Chapter 4: The Sceptical Chymists

1. Stanislao Cannizzaro, Sketch of a Course of Chemical Philosophy, in Il Nuovo Cimento, 7 (1858), pp. 321–66. Reproduced as Alembic Club (Edinburgh) Reprint 18, The University of Chicago Press, 1911. This quote appears on p. 11.

2. See, e.g., Jed Z. Buchwald, The Rise of the Wave Theory of Light, University of Chicago Press, 1989, pp. 6–7.

3. Isaac Newton, Opticks, 4th edn (first published 1730), Dover Books, New York, 1952. This quote from Querie 29 appears on p. 370.

4. Querie 31 contains the passage: ‘Have not the Small Particles of Bodies certain Powers, Virtues or Forces, by which they act at a distance, not only upon the Rays of Light … but also upon one another for producing a great Part of the Phænomena of Nature? For it’s well known that Bodies act upon one another by the attractions of Gravity, Magnetism and Electricity … and make it not improbable but that there may be more attractive Powers than these.’ Newton, Opticks, ibid., pp. 375–6.

5. Querie 31 continues: ‘I had rather infer … that their Particles attract one another by some Force, which in immediate Contact is exceeding strong, at small distances performs the chymical Operations above-mention’d, and reaches not far from the Particles with any sensible Effect.’ Newton, Opticks, ibid., p. 389.

6. Boyle wrote: ‘And, to prevent mistakes, I must advertise you, that I now mean by elements, and those chymists, that speak plainest, do by their principles, certain primitive and simple, or perfectly unmingled bodies, which not being made of any other bodies, or of one another, are the ingredients, of which all those called perfectly mixt bodies are immediately compounded, and into which they are ultimately resolved.’ Robert Boyle, The Sceptical Chymist, reproduced in Thomas Birch, The Works of the Honourable Robert Boyle, Vol. 1, London, 1762, p. 562.

7. Joseph Priestley, Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air, Vol. II, Section III, London 1775, http://web.lemoyne.edu/~GIUNTA/priestley.html.

8. Dalton wrote: ‘An enquiry into the relative weights of the ultimate particles of bodies is a subject, as far as I know, entirely new: I have already been prosecuting this enquiry with remarkable success. The principle cannot be entered upon in this paper; but I shall just subjoin the results, as they appear to be ascertained by my experiments.’ The paper was published two years later, in 1805. John Dalton, quoted in Frank Greenaway, John Dalton and the Atom, Heinemann, London, 1966, p. 165.

9. Cannizzaro, Sketch of a Course of Chemical Philosophy (n 1), p. 11.

10. Cannizzaro, Sketch of a Course of Chemical Philosophy (n 1), p. 11.

11. Cannizzaro, Sketch of a Course of Chemical Philosophy (n 1), p. 12.

12. Einstein wrote: ‘In this paper it will be shown that, according to the molecular-kinetic theory of heat, bodies of a microscopically visible size suspended in liquids must, as a result of thermal molecular motions, perform motions of such magnitude that they can be easily observed with a microscope. It is possible that the motions to be discussed here are identical with so-called Brownian molecular motion; however the data available to me on the latter are so imprecise that I could not form a judgement on the question.’ Albert Einstein, Annalen der Physik, 17 (1905), pp. 549–60. This paper is translated and reproduced in John Stachel (ed.), Einstein’s Miraculous Year: Five Papers that Changed the Face of Physics, Centenary edn, Princeton University Press, 2005. The quote appears on p. 85.

Chapter 5: A Very Interesting Conclusion

1. Albert Einstein, Annalen der Physik, 18 (1905), pp. 639–41, trans. and repr. in John Stachel (ed.), Einstein’s Miraculous Year: Five Papers that Changed the Face of Physics, centenary edn, Princeton University Press, 2005. The quote appears on p. 164.

2. Maxwell wrote that the speed is: ‘… so nearly that of light, that it seems we have strong reason to conclude that light itself (including radiant heat, and other radiations if any) is an electromagnetic disturbance in the form of waves propagated through the electromagnetic field according to electromagnetic laws.’ James Clerk Maxwell, A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field, Part I, §20 (1864), https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/A_Dynamical_Theory_of_the_Electromagnetic_Field/Part_I.

3. Einstein wrote: ‘The introduction of a “light ether” will prove to be superfluous, inasmuch as the view to be developed here will not require a “space at absolute rest” endowed with special properties …’. Albert Einstein, Annalen der Physik, 17 (1905), pp. 891–921, trans. and repr. in Stachel, Einstein’s Miraculous Year (n 1), p. 124.

4. We make our first set of measurements whilst the train is stationary. The light travels straight up and down, travelling a total distance of 2d0, where d0 is the height of the carriage, let’s say in a time t0. We therefore know that 2d0 = ct0, where c is the speed of light, as the light travels up (d0) and then down (another d0) in the time t0 at the speed c. If we know d0 precisely, we could use this measurement to determine the value of c. Alternatively, if we know c we can determine d0. We now step off the train and repeat the measurement as the train moves past us with velocity ν, where ν is a substantial fraction of the speed of light. From our perspective on the platform the light path looks like ‘Λ’. Let’s assume that total time required for the light to travel this path is t. If we join the two ends of the Λ together we form an equilateral triangle, Δ. We know that the base of this triangle has a length given by νt, the distance the train has moved forward in the time t. The other two sides of the triangle measure a distance d and we know that 2d = ct (remember that the speed of light is assumed to be constant). If we now draw a perpendicular (which will have length equal to d0) from the apex of the triangle and which bisects the base, we can use Pythagoras’ theorem: the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides, or d2 = d02 + (½νt)2. But we know that d = ½ct and from our earlier measurement d0 = ½ct0, so we have: (½ct)2 = (½ct0)2 + (½νt)2. We can now cancel all the factors of ½ and multiply out the brackets to give: c2t2 = c2t02 + ν2t2. We gather the terms in t2 on the left-hand side and divide through by c2 to obtain: t2(1 – ν2/c2) = t02, or, re-arranging and taking the square-root: t = γt0, where γ = 1/√(1 – ν2/c2).

5. On 21 September 1908, Minkowski began his address to the 80th Assembly of German Natural Scientists and Physicians with these words: ‘The views of space and time which I wish to lay before you have sprung from the soil of experimental physics, and therein lies their strength. They are radical. Henceforth space by itself, and time by itself, are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality.’ Hermann Minkowski, ‘Space and Time’ in Hendrik A. Lorentz, Albert Einstein, Hermann Minkowski, and Hermann Weyl, The Principle of Relativity: A Collection of Original Memoirs on the Special and General Theory of Relativity, Dover, New York, 1952, p. 75.

6. Albert Einstein, Annalen der Physik, 18 (1905), pp. 639–41, in Stachel, Einstein’s Miraculous Year (n 1), p. 161.

7. The energy carried away by the light bursts in the stationary frame of reference is E, compared with γE in the moving frame of reference. Energy must be conserved, so we conclude that the difference must be derived from the kinetic energies of the object in the two frames of reference. This difference in kinetic energy must be, therefore, γE – E, or E(γ – 1). As it stands, the term E(γ – 1) isn’t very informative, and the Lorentz factor γ – which, remember, equals 1/√(1 – ν2/c2)—is rather cumbersome. But we can employ a trick often used by mathematicians and physicists. Complex functions like γ can be re-cast as the sum of an infinite series of simpler terms, called a Taylor series (for eighteenth-century English mathematician Brook Taylor). The good news is that for many complex functions we can simply look up the relevant Taylor series. Even better, we often find that the first two or three terms in the series provide an approximation to the function that is good enough for most practical purposes. The Taylor series in question is: 1/√(1 + x) = 1 – (½)x + (3⁄8)x2 – (5⁄16)x3 + (35⁄128)x4 – (63⁄256)x5 +. … Substituting x = –ν2/c2 means that terms in x2 are actually terms in ν4/c4 and so on for higher powers of x. Einstein was happy to leave these out, writing: ‘Neglecting magnitudes of the fourth and higher order …’. Neglecting the higher-order terms gives rise to a small error of the order of a few per cent for speeds ν up to about fifty per cent of the speed of light, but the error grows dramatically as ν is further increased. So, substituting x = –ν2/c2 in the first two terms in the Taylor series means that we can approximate γ as 1 + ½ν2/c2. If we now put this into the expression for the difference in kinetic energies above, we get: E(γ – 1) ~ ½Eν2/c2, or ½(E/c2)ν2. Did you see what just happened? We know that the expression for kinetic energy is ½mν2, and in the equation for the difference we see that the velocity ν is unchanged. Instead, the energy of the light bursts comes from the mass of the object, which falls by an amount m = E/c2.

8. Einstein, Annalen der Physik, 18 (1905), p. 164, in Stachel, Einstein’s Miraculous Year (n 1).

Chapter 6: Incommensurable

1. Max Jammer, Concepts of Mass in Contemporary Physics and Philosophy, Princeton University Press, 2000, p. 61.

2. Einstein wrote: ‘It is not good to introduce the concept of the [relativistic] mass M … of a moving body for which no clear definition can be given. It is better to introduce no other mass concept than the “rest mass”, m. Instead of introducing M it is better to mention the expression for the momentum and energy of a body in motion.’ Albert Einstein, letter to Lincoln Barnett, 19 June 1948. A facsimile of part of this letter is reproduced, together with an English translation, in Lev Okun, Physics Today, June 1989, p. 12.

3. Okun wrote: ‘… the terms “rest mass” and “relativistic mass” are redundant and misleading. There is only one mass in physics, m, which does not depend on the reference frame. As soon as you reject the “relativistic mass” there is no need to call the other mass the “rest mass” and to mark it with the index 0.’ In his opening paragraph, picked out in a large, bold font, he declares: ‘In the modern language of relativity theory there is only one mass, the Newtonian mass m, which does not vary with velocity.’ Okun, ibid., p. 11.

4. See, e.g., A.P. French, Special Relativity, MIT Introductory Physics Series, Van Nostrand Reinhold, London, 1968 (reprinted 1988), p. 23.

5. Albert Einstein, Annalen der Physik, 18 (1905), pp. 639–41. Trans. and repr. in John Stachel (ed.), Einstein’s Miraculous Year: Five Papers that Changed the Face of Physics, centenary edn, Princeton University Press, 2005. The quote appears on p. 164.

6. Paul Feyerabend, ‘Problems of Empiricism’, in R.G. Colodny, Beyond the Edge of Certainty, Englewood-Cliffs, New Jersey (1965), p. 169. This quote is reproduced in Jammer, Concepts of Mass (n 1), p. 57.

Chapter 7: The Fabric

1. John Wheeler with Kenneth Ford, Geons, Black Holes and Quantum Foam: A Life in Physics, W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1998, p. 235.

2. Albert Einstein, ‘How I Created the Theory of Relativity’, lecture delivered at Kyoto University, 14 December 1922, trans. Yoshimasa A. Ono, Physics Today, August 1982, p. 47.

3. Albert Einstein, in the ‘Morgan manuscript’, quoted by Abraham Pais, Subtle is the Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein. Oxford University Press, 1982, p. 178.

4. Wheeler with Ford, Geons, Black Holes and Quantum Foam (n 1).

6. Albert Einstein, letter to Heinrich Zangger, 26 November 1915. This quote is reproduced in Alice Calaprice (ed.), The Ultimate Quotable Einstein, Princeton University Press, 2011, p. 361.

7. We can get some sense for what the Schwarzschild solutions tell us by supposing we measure two events at some distance far away from a massive object, where the effects of spacetime curvature can be safely ignored. Spacetime here is flat, and we note the time interval Δt between the two events. The Schwarzschild solutions show that the same measurement performed closer to the object where spacetime is more curved will yield a different result, Δt’, where Δt’ = Δt/(1 – Rs/r). Here Rs is the Schwarzschild radius, given by Gm/c2, where m is the mass of the object, c is the speed of light, and G is the gravitational constant. Let us further assume that we’re well outside the Schwarzschild radius, so r is much larger than Rs. (The Schwarzschild radius of the Earth is about 9 millimetres.) This means that the term in brackets is a little smaller than 1, so Δt’ is slightly larger than Δt, or time intervals are dilated. This is gravitational time dilation—clocks run more slowly where the effects of gravity (spacetime curvature) are stronger. It is an effect entirely separate and distinct from the time dilation of special relativity, which is caused by making measurements in different inertial frames of reference. We can make a similar set of deductions for a measurement of radial distance interval Δr, at a fixed time such that Δt = 0. We find Δr’ = (1 – Rs/r)Δr. Now Δr’ is slightly smaller than Δr. Distances contract under the influence of a gravitational field.

8. See Metromnia, National Physical Laboratory, 18, Winter 2005.

Chapter 8: In the Heart of Darkness

1. Albert Einstein, Proceedings of the Prussian Academy of Sciences, 142 (1917), quoted in Walter Isaacson, Einstein: His Life and Universe, Simon & Shuster, New York, 2007, p. 255.

2. Newton wrote: ‘… and lest the systems of the fixed stars should, by their gravity, fall on each other mutually, he hath placed those systems at immense distances one from another’. Isaac Newton, Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy, first American edn trans. Andrew Motte, Daniel Adee, New York, 1845, p. 504.

3. See, e.g., Steven Weinberg, Cosmology, Oxford University Press, 2008, p. 44.

4. According to Ukranian-born theoretical physicist George Gamow: ‘When I was discussing cosmological problems with Einstein he remarked that the introduction of the cosmological term was the biggest blunder he ever made in his life.’ George Gamow, My World Line: An Informal Autobiography, Viking Press, New York, 1970, p. 149, quoted in Walter Isaacson, Einstein (n 1), pp. 355–6.

5. Hubble’s law can be expressed as ν = H0D, where ν is the velocity of the galaxy, H0 is Hubble’s constant as measured in the present time, and D is the so-called ‘proper distance’ of the galaxy measured from the Earth, such that the velocity is then given simply as the rate of change of this distance. Although it is often referred to as a ‘constant’, in truth the Hubble parameter H varies with time depending on assumptions regarding the rate of expansion of the universe. Despite this, the age of the universe can be roughly estimated as 1/H0. A value of H0 of 67.74 kilometres per second per megaparsec (or 2.195 × 10−18 per second) gives an age for the universe of 45.66 × 1016 seconds, or 14.48 billion years. (The age as determined by the Planck satellite mission is 13.82 billion years, so the universe is a little younger than it’s ‘Hubble age’ would suggest.)

6. Lemaître wrote: ‘Everything happens as though the energy in vacuo would be different from zero.’ Georges Lemaître, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 20 (1934), pp. 12–17, quoted in Harry Nussbaumer and Lydia Bieri, Discovering the Expanding Universe, Cambridge University Press, 2009, p. 171.

7. In 1922, Russian physicist and mathematician Alexander Friedmann offered a number of different solutions of Einstein’s original field equations. These can be manipulated to yield a relatively simple expression for the critical density (ρc) of mass-energy required for a flat universe: ρc = 3H02/8πG, where H0 is the Hubble constant and G is the gravitational constant. The value of H0 deduced from the most recent measurements of the cosmic background radiation is 67.74 kilometres per second per megaparsec, or 2.195 × 10−18 per second. With G = 6.674 × 10−11 Nm2kg−2 (or m3kg−1s−2), and H02 = 4.818 × 10−36 s−2, we get ρc = 8.617 x 10−27 kgm−3, which translates to 8.617 × 10−30 gcm−3. Compare this with the density of air at sea level at a temperature of 15°C, which is 0.001225 gcm−3.

8. The mass of a proton is 1.67 × 10−24 g, so we need a critical density of the order of 5.16 × 10−6 protons per cubic centimetre. The length of St Paul’s Cathedral is 158 metres, with a height of 111 metres and a width between transepts of 75 metres. We can combine these to obtain a rough estimate of the volume, 158 × 111 × 75 = 1.315 × 106 m3, or 1.315 × 1012 cm3. If the critical density ρc is equivalent to 5.16 × 10−6 protons per cm3, then to meet this density we would need to fill St Paul’s Cathedral with 6.79 × 106 protons, which I’ve rounded up to an average of 7 million protons. To calculate the number of protons and neutrons in the air inside St Paul’s Cathedral, I’ve assumed the air density at sea level (see n 7) of 0.001225 gcm−3. This gives the total mass of air inside the Cathedral of 1.611 × 109 g. Assuming an average proton/neutron mass of 1.6735 × 10−24 g gives a total number of protons and neutrons inside the cathedral of 9.63 × 1032.

9. So, what is the density of dark energy? If we assume ρc is 8.62 × 10−30 gcm−3, we know from the latest Planck satellite results that dark energy must account for about sixty-nine per cent of this, or 5.94 × 10−30 gcm−3. This is really a mass density, so we convert it to an energy density using E = mc2, giving 5.34 × 10−16 Jcm−3. If we call this vacuum energy density ρv, we can use the relation Λ = (8πG/c4)ρv to calculate a value for the cosmological constant of 1.109 × 10−52 per square metre. We can put this dark or vacuum energy density into perspective. The chemical energy released on combustion of a litre (1,000 cubic centimetres) of petrol (gasoline for American readers) is 32.4 million joules, implying an energy density of 32,400 Jcm−3. So, ‘empty’ spacetime has an energy density about 1.6 hundredths of a billionth of a billionth (1.6 × 10−20) of the chemical energy density of petrol. It might not be completely empty, but it’s still the ‘vacuum’, after all.

Chapter 9: An Act of Desperation

1. Max Planck, letter to Robert Williams Wood, 7 October 1931, quoted in Armin Hermann, The Genesis of Quantum Theory (1899–1913), trans. Claude W. Nash, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1971, p. 21.

2. Max Planck, letter to Wilhelm Ostwald, 1 July 1893, quoted in J.L. Heilbron, The Dilemmas of an Upright Man: Max Planck and the Fortunes of German Science, Harvard University Press, 1996, p. 15.

3. Max Planck, Physikalische Abhandlungen und Vorträge, Vol. 1, Vieweg, Braunschweig, 1958, p. 163, quoted in Heilbron, ibid., p. 14.

4. Einstein wrote: ‘If monochromatic radiation (of sufficiently low density) behaves … as though the radiation were a discontinuous medium consisting of energy quanta of magnitude [hν], then it seems reasonable to investigate whether the laws governing the emission and transformation of light are also constructed such as if light consisted of such energy quanta.’ Albert Einstein, Annalen der Physik, 17 (1905), pp. 143–4, English translation quoted in John Stachel (ed.), Einstein’s Miraculous Year: Five Papers that Changed the Face of Physics, Princeton University Press, 2005, p. 191. The italics are mine.

5. The Rydberg formula can be written 1/λ = RH(1/m2 – 1/n2), where λ is the wavelength of the emitted radiation, measured in a vacuum, and RH is the Rydberg constant for hydrogen.

6. Bohr imposed the condition that the angular momentum of the electron in an orbit around the nucleus be constrained to nh/2π, where n is an integer number (a quantum number) and h is Planck’s constant.

7. We saw in Chapter 5 that in Einstein’s derivation of E = mc2 he deduced that the energy of a system measured in its rest frame (call this E0) increases to the relativistic energy E = γE0 when measured in a frame of reference moving with velocity ν. We can re-arrange this expression to give E/γ = E0, or E√ (1 – ν2/c2) = E0. Squaring both sides of this equation then gives: E2(1 – ν2/c2) = E02. If we now multiply through the term in brackets and re-arrange, we get: E2 = (E/c)2ν2 + E02. Of course, (E/c)2 = m2c2, so E2 = (mν)2c2 + E02. For speeds ν much less than c the product mν is the momentum of the object, given the symbol p. We generalize p to represent the relativistic momentum. Finally, we have E2 = p2c2 + E02. We can now substitute for E0 = m0c2 to give E2 = p2c2 + m02c4. This is the full expression for the relativistic energy of radiation and matter. If this expression is unfamiliar and rather daunting, think of it this way. If the relativistic energy E is the hypotenuse of a right-angled triangle, then the kinetic energy pc and the rest energy m0c2 form the other two sides. The expression is then just a statement of Pythagoras’ theorem. For photons with m0 = 0, this general equation reduces to E = pc.

8. You might wonder why the kinetic energy is equal to pc and not ½pc, which would appear to be more consistent with the classical expression for kinetic energy, ½mν2 (which we can re-write as ½pν, where p = mν). Are we missing a factor of ½? Actually, no. If we’re prepared to make a few assumptions, we can derive a simpler expression for the relativistic energy for situations where the speed ν is much less than c. Recall from Chapter 5 (n 7) that for speeds ν much less than c we can approximate γ as 1 + ½ν2/c2. Using this simplified version in E = γE0 gives E = E0 + ½E0ν2/c2. Again, we can substitute E0 = m0c2 to give E = m0c2 + ½m0ν2, which is the rest energy plus the classical kinetic energy with speed ν. Setting the linear momentum p = mν gives us E = m0c2 + ½pν.

9. De Broglie wrote: ‘After long reflection in solitude and meditation, I suddenly had the idea, during the year 1923, that the discovery made by Einstein in 1905 should be generalized by extending it to all material particles and notably to electrons.’ Louis de Broglie, from the 1963 re-edited version of his Ph.D. thesis, quoted in Abraham Pais, Subtle is the Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford University Press, 1982, p. 436.

10. In 2012, the Australian tennis player Sam Groth served an ace with a recorded speed of 263.4 kilometres per hour. We can covert this to 73 metres per second. The mass of a tennis ball is typically in the range 57–59 grams, so let’s run with 58 grams, or 0.058 kilograms. This gives a linear momentum p = mν for the ball in flight of 0.058 × 73 = 4.2 kgms−1. We can now use λ = h/p to calculate the wavelength of the tennis ball. We get: λ = 6.63 × 10−34/4.2 metres, or 1.6 × 10−34 metres. Compare this with wavelengths typical of X-rays, which range between 0.01 and 10 × 10−9 metres. The wavelength of the tennis ball is much, much shorter than the wavelengths of X-rays.

Chapter 10: The Wave Equation

1. Felix Bloch, Physics Today, 29, 1976, p. 23.

2. In modern atomic physics, the azimuthal quantum number l takes values l = 0, 1, 2, and so on up to the value of n – 1. So, if n = 1 then l can take only one value, l = 0. This corresponds to an electron orbital labelled 1s (the label ‘s’ is a hangover from the early days of atomic spectroscopy when the absorption or emission lines were labelled ‘s’ for ‘sharp’, ‘p’ for ‘principal’, ‘d’ for ‘diffuse’, and so on). For n = 2, l can take the values 0 (corresponding to the 2s orbital) and 1 (2p). The magnetic quantum number m takes integer values in the series –l, … 0, … , +l. So, if l = 0, m = 0 and there is only one s orbital, irrespective of the value of n. But when l = 1 there are three possible orbitals corresponding to m = –1, m = 0, and m = +1. There are therefore three p orbitals. In the case of the 2p orbitals these are sometimes shown mapped to Cartesian co-ordinates as 2px, 2py and 2pz.

3. Bloch, Physics Today (n 1), p. 23.

4. A sine wave moving to the right in the positive x-direction has a general form sin(kx – ωt), where k is the ‘wave vector’ given by 2π/λ and ω is the ‘angular frequency’ given by 2πν, where λ and ν are the wavelength and frequency of the wave. It might not be immediately obvious that this represents a wave moving to the right, in the positive x-direction, so let’s take a closer look at it. Let’s call the location of the first peak of this wave as measured from the origin xpeak. At this point sin(kxpeak – ωt) = 1, or alternatively the angle given by kxpeak – ωt is equal to 90° (or (½)π radians). We know that k = 2π/λ and ω = 2πν, so we can rearrange this expression to give xpeak = νλt + λ/4. Of course, ν times λ is just the wave velocity, ν. At a time t = 0, the first peak of the wave appears at a distance xpeak = λ/4: the wave rises to its peak in the first quarter of its cycle, before falling again, as in ∿. As time increases from zero, we see that xpeak increases by a distance given by νt. In other words, the wave moves to the right.

5. Erwin Schrödinger, Annalen der Physik, 79 (1926), p. 361. Quoted in Walter Moore, Schrödinger: Life and Thought, Cambridge University Press, 1989, p. 202.

6. We can rewrite ½mν2 in terms of the classical linear momentum, p = mν, as ½p2/m. Schrödinger’s wave equation could be interpreted to mean that p2 in the kinetic energy term had been replaced by a differential operator.

7. Let’s just prove that to ourselves. We’ll use the function x2. The two mathematical operations we’ll perform are ‘multiply by 2’ and ‘take the square root’. If we multiply by 2 first, then the result is simply √2x2 or 1.414x. If we take the square root first and then multiply by 2, we get 2x.

8. Heisenberg wrote: ‘I remember discussions with Bohr which went through many hours till very late at night and ended almost in despair; and when at the end of the discussion I went alone for a walk in the neighbouring park I repeated to myself again and again the question: Can nature possibly be as absurd as it seemed … ?’ Werner Heisenberg, Physics and Philosophy: The Revolution in Modern Science, Penguin, London, 1989 (first published 1958), p. 30.

9. The frequency of the wave is given by its speed divided by its wavelength, ν = ν/λ, where ν is the velocity. Alternatively, λ = ν/ν, which we can substitute into the de Broglie relationship λ = h/p to give ν/ν = h/p. Rearranging, we get ν = pν/h.

10. The 1s orbital has n = 1 and l = 0 and possesses a spherical shape. This can accommodate up to two electrons (accounting for hydrogen and helium). For n = 2 we have a spherical 2s (l = 0) and three dumbbell-shaped 2p (l = 1) orbitals, accommodating up to a total of eight electrons (lithium to neon). For n = 3 we have one 3s (l = 0), three 3p (l = 1), and five 3d (l = 2) orbitals. These can accommodate up to eighteen electrons but it turns out that the 4s orbital actually lies somewhat lower in energy than 3d and is filled first. The pattern is therefore 3s and 3p (eight electrons—sodium to argon), then 4s, 3d, and 4p (eighteen electrons—potassium to krypton).

Chapter 11: The Only Mystery

1. Richard P. Feynman, Robert B. Leighton, and Matthew Sands, The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol. III, Addison-Wesley, Reading, Massachusetts, 1965, p. 1–1.

2. Paul Dirac, Proceedings of the Royal Society, A133, 1931, pp. 60–72, quoted in Helge S. Kragh, Dirac: A Scientific Biography, Cambridge University Press, 1990, p. 103.

3. The catalogue can be found at http://pdg.lbl.gov/. Select ‘Summary Tables’ from the menu and then ‘Leptons’. The electron tops this list.

4. Einstein wrote: ‘Quantum mechanics is very impressive. But an inner voice tells me that it is not yet the real thing. The theory produces a good deal but hardly brings us closer to the secret of the Old One. I am at all events convinced that He does not play dice.’ Albert Einstein, letter to Max Born, 4 December 1926, quoted in Abraham Pais, Subtle is the Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein, Oxford University Press, 1982, p. 443.

5. Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky, and Nathan Rosen, Physical Review, 47, 1935, pp. 777–80. This paper is reproduced in John Archibald Wheeler and Wojciech Hubert Zurek, (eds), Quantum Theory and Measurement, Princeton University Press, 1983, p. 141.

6. Bell wrote: ‘If the [hidden variable] extension is local it will not agree with quantum mechanics, and if it agrees with quantum mechanics it will not be local. This is what the theorem says.’ John Bell, Epistemological Letters, November 1975, pp. 2–6. This paper is reproduced in J.S. Bell, Speakable and Unspeakable in Quantum Mechanics, Cambridge University Press, 1987, pp. 63–6. The quote appears on p. 65.

7. E.g., for one specific experimental arrangement, the generalized form of Bell’s inequality demands a value that cannot be greater than 2. Quantum theory predicts a value of 2√2, or 2.828. The physicists obtained the result 2.697 ± 0.015. In other words, the experimental result exceeded the maximum limit predicted by Bell’s inequality by almost fifty times the experimental error, a powerful, statistically significant violation.

8. A.J. Leggett, Foundations of Physics, 33, 2003, pp. 1474–5.

9. For a specific experimental arrangement, the whole class of crypto non-local hidden variable theories predicts a maximum value for the Leggett inequality of 3.779. Quantum theory violates this inequality, predicting a value of 3.879, a difference of less than three per cent. The experimental result was 3.852 ± 0.023, a violation of the Leggett inequality by more than three times the experimental error.

10. In these experiments for a specific arrangement the maximum value allowed by the Leggett inequality is 1.78868, compared with the quantum theory prediction of 1.93185. The experimental result was 1.9323 ± 0.0239, a violation of the inequality by more than six times the experimental error.

Chapter 12: Mass Bare and Dressed

1. Hans Bethe, Calculating the Lamb Shift, Web of Stories, http://www.webofstories.com/play/hans.bethe/104;jsessionid=45C0C719DE8CEA2C0899D6A63E281F24.

2. Although structurally very different, we can get some idea of how the perturbation series is supposed to work by looking at the power series expansion for a simple trigonometric function such as sin x. The first few terms in the expansion are: sin x = x – x3/3! + x5/5! – x7/7! +. … In this equation, 3! means 3-factorial, or 3 × 2 × 1 (= 6); 5! = 5 × 4 × 3 × 2 × 1 (= 120), and so on. For x = 45° (0.785398 radians), the first term (x) gives 0.785398, from which we subtract x3/3! (0.080745), then add x5/5! (0.002490), then subtract x7/7! (0.000037). Each successive term gives a smaller correction, and after just four terms we have the result 0.707106, which should be compared with the correct value, sin(45°) = 0.707107.

3. Murray Gell-Mann, Nuovo Cimento, Supplement No. 2, Vol. 4, Series X, 1958, pp. 848–66. In a footnote on p. 859, he wrote: ‘… any process not forbidden by a conservation law actually does take place with appreciable probability. We have made liberal and tacit use of this assumption, which is related to the state of affairs that is said to prevail in a perfect totalitarian state. Anything that is not compulsory is forbidden.’ He was paraphrasing Terence Hanbury (T.H.) White, the author of The Once and Future King.

Chapter 13: The Symmetries of Nature

1. Wolfgang Pauli, part of a conversation reported by Chen-Ning Yang at the International Symposium on the History of Particle Physics, Batavia, Illinois, 2 May 1985, quoted by Michael Riordan, The Hunting of the Quark: A True Story of Modern Physics, Simon & Shuster, New York, 1987, p. 198.

2. It is relatively straightforward to picture the symmetry transformations of U(1) in the so-called complex plane, the two-dimensional plane formed by one real axis and one ‘imaginary axis’. The imaginary axis is constructed from real numbers multiplied by i, the square root of minus one. We can pinpoint any complex number z in this plane using the formula, z = reiθ, where r is the length of the line joining the origin with the point z in the plane and θ is the angle between this line and the real axis. This expression for z can be re-written using Euler’s formula as z = r(cosθ + isinθ), which makes the connection between U(1) and continuous transformations in a circle and with the phase angle of a sine wave.

3. We can get a very crude sense for why this must be from Heisenberg’s energy–time uncertainty relation and special relativity. According to the uncertainty principle the product of the uncertainties in energy and the rate of change of energy with time, ΔEΔt, cannot be less than h/4π. The range of a force-carrying particle is then roughly determined by the distance it can travel in the time Δt. We know that nothing can travel faster than the speed of light so the maximum range of a force-carrying particle is given by cΔt, or hc/4πΔE. If we approximate ΔE as mc2, where m is the mass of the force carrier, then the range (let’s call it R) is given by h/4πmc. We see that the range of the force is inversely proportional to the mass of the force carrier. If we assume photons are massless (m = 0), then the range of the electromagnetic force is infinite.

4. The radius of a proton is something of the order of 0.85 × 10−15 m. If we assume that the force binding protons and neutrons together inside the nucleus must operate over this kind of range, we can crudely estimate the mass of the force-carrying particles that would be required from h/4πRc. Plugging in the values of the physical constants gives us a mass of 0.2 × 10−27 kg, or ~100 MeV/c2, about eleven per cent of the mass of a proton. This is the figure obtained by Yukawa in 1935 for particles that he believed should carry the strong force between protons and neutrons. Although the strong force is now understood to operate very differently (see Chapter 15), Yukawa was correct in principle. These ‘force carriers’ are the pions, which come in positive (π+), negative (π–) and neutral (π0) varieties with masses of about 140 MeV/c2 (π+ and π–) and 135 MeV/c2 (π0).

5. Riordan, The Hunting of the Quark (n 1), p. 198.

6. Yang wrote: ‘The idea was beautiful and should be published. But what is the mass of the [force-carrying] gauge particle? We did not have firm conclusions, only frustrating experiences to show that [this] case is much more involved than electromagnetism. We tended to believe, on physical grounds, that the charged gauge particles cannot be massless.’ Chen Ning Yang, Selected Papers with Commentary, W.H. Freeman, New York, 1983, quoted by Christine Sutton in Graham Farmelo, (ed.), It Must be Beautiful: Great Equations of Modern Science, Granta Books, London, 2002, p. 243.

7. I’ve scratched around in an attempt to find a simple and straightforward explanation for what is a very important feature of quantum field theories, but have come to the conclusion that this is really difficult to do without resorting to a short course on the subject. The best I can do is give you a sense for where the ‘mass term’ comes from. Remember that Schrödinger derived his non-relativistic wave equation from the equation for classical wave motion by substituting for the wavelength using the de Broglie relation, λ = h/p. His manipulations had the effect of changing the nature of the kinetic energy term in the equation for the total energy. In Newtonian mechanics this is the familiar ½mν2, where m is the mass and ν the velocity. We can re-write this in terms of the linear momentum p (= mν) as ½p2/m. In the Schrödinger wave equation, the expression for kinetic energy is structurally similar but the classical p2 is now replaced by a mathematical operator (let’s call it p2, which means the operator is applied twice to the wavefunction, ψ). But, as we saw in Chapter 10, Schrödinger’s equation does not conform to the demands of special relativity. In fact, Schrödinger did work out a fully relativistic wave equation but found that it did not make predictions that agreed with experiment. This version of the wave equation was rediscovered by Swedish theorist Oskar Klein and German theorist Walter Gordon in 1926 and is known as the Klein–Gordon equation. Its derivation is based on the expression for the relativistic energy, E2 = p2c2 + m02c4, which is ‘quantized’ by replacing the classical p2 with the quantum-mechanical operator equivalent, p2, just as Schrödinger had done. There are two things to note about this. First, we’re dealing not with energy but with energy-squared. Second, we have now introduced a term which depends on the square of the mass. We introduce a quantum field, ϕ, on which the momentum operator is applied, and in consequence a term in the dynamical equations appears which is related to m2ϕ2. Although the Klein–Gordon equation does not account for spin (so it can’t be used to describe electrons, as Schrödinger discovered), it is perfectly valid when applied to particles with zero spin (as it happens, particles such as the pions). From it we learn that mass terms related to m2ϕ2 can be expected to appear in any valid formulation of quantum field theory that meets the demands of special relativity.

Chapter 14: The Goddamn Particle

1. Leon Lederman, with Dick Teresi, The God Particle: If the Universe is the Answer, What is the Question?, Bantam Press, London, 1993, p. 22.

2. Look back at Chapter 12, n 3. We can crudely estimate the range of a force carried by a particle with a mass this size from h/4πmc. Let’s set m = 350 × 10−27 kg (a couple of hundred times the proton mass) and plug in the values of the physical constants. We get a range of about 0.5 × 10−18 m, well inside the confines of the proton or neutron (which, remember, have a radius of about 0.85 × 10−15 m). A recent paper by the ZEUS Collaboration at the Hadron-Elektron Ring Anlage (HERA) in Hamburg, Germany recently set an upper limit on the size of a quark of 0.43 × 10−18 m. This article is available online at the Cornell University Library electronic archive site (http://arxiv.org), with the reference arXiv: 1604.01280v1, 5 April 2016. Actually, it turns out that the weak force carriers are not quite this heavy (they are a little less than 100 times the mass of a proton).

3. Schwinger later explained: ‘It was numerology … But—that’s the whole idea. I mentioned this to [J. Robert] Oppenheimer, and he took it very coldly, because, after all, it was an outrageous speculation.’ Comment by Julian Schwinger at an interview on 4 March 1983, quoted in Robert P. Crease and Charles C. Mann, The Second Creation: Makers of the Revolution in Twentieth-century Physics, Rutgers University Press, 1986, p. 216.

4. Some years later, Nambu wrote: ‘What would happen if a kind of superconducting material occupied all of the universe, and we were living in it? Since we cannot observe the true vacuum, the [lowest-energy] ground state of this medium would become the vacuum, in fact. Then even particles which were massless … in the true vacuum would acquire mass in the real world.’ Yoichiro Nambu, Quarks, World Scientific Publishing, Singapore, 1981, p. 180.

5. Higgs wrote: ‘I was indignant. I believed that what I had shown could have important consequences in particle physics. Later, my colleague Squires, who spent the month of August 1964 at CERN, told me that the theorists there did not see the point of what I had done. In retrospect, this is not surprising: in 1964 … quantum field theory was out of fashion …’. Peter Higgs, in Lillian Hoddeson, Laurie Brown, Michael Riordan, and Max Dresden, The Rise of the Standard Model: Particle Physics in the 1960s and 1970s, Cambridge University Press, 1997, p. 508.

6. In his Nobel lecture, Weinberg said: ‘At some point in the fall of 1967, I think while driving to my office at MIT, it occurred to me that I had been applying the right ideas to the wrong problem.’ Steven Weinberg, Nobel Lectures, Physics 1971–1980, ed. Stig Lundqvist, World Scientific, Singapore (1992), p. 548.

7. In an interview with Robert Crease and Charles Mann on 7 May 1985, Weinberg declared: ‘My God, this is the answer to the weak interaction!’ Steven Weinberg, quoted in Crease and Mann, The Second Creation (n 3), p. 245.

8. In his Foreword to my book Higgs, Weinberg wrote: ‘Rather, I did not include quarks in the theory simply because in 1967 I just did not believe in quarks. No-one had ever observed a quark, and it was hard to believe that this was because quarks are much heavier than observed particles like protons and neutrons, when these observed particles were supposed to be made of quarks.’ See Jim Baggott, Higgs: The Invention and Discovery of the ‘God’ Particle, Oxford University Press, 2012, p. xx.

9. Lederman, with Teresi, The God Particle (n 1), p. 22.

Chapter 15: The Standard Model

1. Willis Lamb, Nobel Lectures, Physics 1942–1962, Elsevier, Amsterdam (1964), p. 286.

2. Enrico Fermi, quoted as ‘physics folklore’ by Helge Kragh, Quantum Generations: A History of Physics in the Twentieth Century, Princeton University Press, 1999, p. 321.

3. Murray Gell-Mann and Edward Rosenbaum, Scientific American, July 1957, pp. 72–88.

4. Murray Gell-Mann, interview with Robert Crease and Charles Mann, 3 March 1983, quoted in Robert P. Crease and Charles C. Mann, The Second Creation: Makers of the Revolution in Twentieth-century Physics, Rutgers University Press, 1986, p. 281.

5. Gell-Mann said: ‘That’s it! Three quarks make a neutron and a proton!’, interview with Robert Crease and Charles Mann, 3 March 1983, quoted in Crease and Mann, ibid., p. 282.

6. ‘We gradually saw that that [colour] variable was going to do everything for us!’, Gell-Mann explained. ‘It fixed the statistics, and it could do that without involving us in crazy new particles. Then we realized that it could also fix the dynamics, because we could build an SU(3) gauge theory, a Yang-Mills theory, on it.’ W.A. Bardeen, H. Fritzsch, and M. Gell-Mann, Proceedings of the Topical Meeting on Conformal Invariance in Hadron Physics, Frascati, May 1972, quoted in Crease and Mann, The Second Creation (n 4), p. 328.

7. Joe Incandela, CERN Press Release, 14 March 2013.

8. ‘The data are consistent with the Standard Model predictions for all parameterisations considered.’ ATLASCONF-2015-044/CMS-PAS-HIG-15-002, 15 September 2015.

Chapter 16: Mass without Mass

1. Frank Wilczek, ‘Four Big Questions with Pretty Good Answers’, talk given at a Symposium in Honour of Heisenberg’s 100th birthday, 6 December 2001, Munich. This article is available online at the Cornell University Library electronic archive site (http://arxiv.org), with the reference arXiv:hep-ph/0201222v2, 5 February 2002. See also ‘QCD and Natural Philosophy’, arXiv:physics/0212025v2 [physics.ed-ph], 12 December 2002.

2. Lucretius, On the Nature of the Universe, trans. R.E. Latham, Penguin Books, London, first published 1951, p. 189.

3. Lucretius wrote: ‘The more the earth is drained of heat, the colder grows the water, the colder grows the water embedded in it.’ Lucretius, ibid., p. 243.

4. Each side measures 2.7 centimetres, so the volume of the cube of ice is 2.73 = 19.7 cubic centimetres. If we look up the density of pure ice at 0°C we find this is 0.9167 grams per cubic centimetre. So, the mass (which I’ll not distinguish from weight) of the cube of ice is given by the density multiplied by the volume, or 0.9167 × 19.7 = 18.06 grams.

5. S. Durr, Z. Fodor, J. Frison, et al., Science, 322, pp. 1224–1227, 21 November 2008, arXiv:0906.3599v1 [hep-lat], 19 June 2009.

6. Sz. Borsanyi, S. Durr, Z. Fodor, et al., Science, 347, pp. 1452–1455, 27 March 2015, also available as arXiv:1406.4088v2 [hep-lat], 7 April 2015. See also the commentary by Frank Wilczek, Nature, 520, pp. 303–4, 16 April 2015.

7. Wilczek, ‘Four Big Questions’ (n 1).

8. See Frank Wilczek, MIT Physics Annual 2003, MIT, pp. 24–35.

9. Albert Einstein, Annalen der Physik, 18 (1905), pp. 639–41, trans. and repr. in John Stachel (ed.), Einstein’s Miraculous Year: Five Papers that Changed the Face of Physics, centenary edn, Princeton University Press, 2005. The quote appears on p. 164.

10. Frank Wilczek, The Lightness of Being, Penguin, London, 2008, p. 132.

Epilogue

1. Albert Einstein and Leopold Infeld, The Evolution of Physics, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1938, p. 313, quoted in Alice Calaprice, The Ultimate Quotable Einstein, Princeton University Press, 2011, p. 390.

2. Max Jammer, Concepts of Mass in Contemporary Physics and Philosophy, Princeton University Press, 2000, p. 167.

3. Stephen P. Martin, ‘A Supersymmetry Primer’, version 6, arXiv: hep-ph/9709356, September 2011, p. 5.

4. The Planck length is given by √(hG/2πc3), where h is Planck’s constant, G is Newton’s gravitational constant, and c is the speed of light.

5. Lee Smolin, Three Roads to Quantum Gravity: A New Understanding of Space, Time and the Universe, Phoenix, London, 2001, p. 211.

6. Carlo Rovelli, ‘Loop Quantum Gravity: The First Twenty-five Years’, arXiv: 1012.4707v5 [gr-qc], 28 January 2012, p. 20.

8. In Reality and the Physicist, the philosopher Bernard d’Espagnat wrote: ‘… we must conclude that physical realism is an “ideal” from which we remain distant. Indeed, a comparison with conditions that ruled in the past suggests that we are a great deal more distant from it than our predecessors thought they were a century ago’, Reality and the Physicist: Knowledge, Duration and the Quantum World, Cambridge University Press, 1989, p. 115.

9. In 1900, the great British physicist Lord Kelvin (William Thomson) is supposed to have famously declared to the British Association for the Advancement of Science that: ‘There is nothing new to be discovered in physics now. All that remains is more and more precise measurement.’ Whilst it appears that we have no evidence that Kelvin ever said this, in Light Waves and their Uses, published in 1903 by The University of Chicago Press, American physicist Albert Michelson wrote:

Many other instances might be cited, but these will suffice to justify the statement that ‘our future discoveries must be looked for in the sixth place of decimals.’ It follows that every means which facilitates accuracy in measurement is a possible factor in a future discovery, and this will, I trust, be a sufficient excuse for bringing to your notice the various methods and results which form the subject-matter of these lectures.

This quote appears on pp. 24–5. It is thought that Michelson may have been quoting Kelvin.