Chapter 14

The Fields of Human Societies and Cultures

In traditional societies, cultural forms persisted over many generations, despite the fact that the people within them were continually changing. Even modern societies have distinct, enduring patterns: for example, British customs are characteristically different from Japanese. And within modern societies there are many distinct social groups, like families, businesses, schools, trade unions, factories, churches, string quartets, clubs, football teams, political parties, and so on. All have their characteristic patterns of organization, and written or unwritten rules and traditions.

Everyone recognizes the existence of patterns of social and cultural organization. We could not function as members of social groups without some knowledge of the prevailing manners, expectations, status hierarchies, and so on. In this chapter, I explore the idea that social and cultural morphic fields organize these patterns.

This approach involves more than the introduction of a new terminology. It enables us to see patterns of social and cultural organization in a much broader context. Social and cultural morphic fields are of the same general nature as the morphogenetic fields of willow trees or chick embryos, the behavioural fields of beavers or blue tits, or the social fields of flocks of birds or packs of wolves. Human social and cultural patterns depend on formative causation, and are sustained by morphic resonance.

I begin with a discussion of the organization of human societies and cultures, and the ways in which this organization is interpreted within the social sciences.

Human societies as organisms

Despite their great diversity, all human societies have fundamental features in common. All incorporate individuals into social groups; all have language; all have structures of kinship and social organization; all have myths and rituals which are in some way related to the origin of the social group and its continuation; all have customs, traditions, and manners; all impose upon the people within them expectations, obligations, rules, and laws; all have systems of morality; and all function as more or less cohesive, self-organizing wholes.

Moreover, all societies and social groups involve an awareness of the group as a unit. People not only belong to groups but they know that they are members of the group and have some conception of it as an entity. They are likewise aware of the existence of other social entities to which they do not belong.

The idea that societies are greater than the sum of their individual parts is taken for granted almost universally. Everyone has grown up with it. The parallel between societies and organisms is so pervasive that it is built into conventional phrases such as the ‘body politic’, the ‘arm of the law’, and the ‘head of state’. Economies too are thought of as if they are living organisms that develop and grow, create demands, consume resources, can be healthy or sick, and so on. Political discourse is replete with phrases that take for granted the reality of collective entities such as parties, social classes, trade unions, corporations and governing bodies. Such vaguely defined concepts as the will of the people, the national interest and spheres of influence are not mere abstractions: they shape political actions and have enormous effects on the world.

Organic views of society are traditional everywhere, and still predominate even in the West. The only major challenge to them is offered by the philosophy of individualism, which has played an important part in the political philosophy of the English-speaking world since the seventeenth century, with its development paralleling the rise of mechanistic science. Individualism gives an atomistic conception of society. The community is not a higher form of unity to which the individual is subordinate; rather the individual is the primary reality, and societies are collections of individuals.

In political thought individualism is usually taken to mean only that the state should not interfere more than necessary with individual liberty. This is the central tenet of the liberal political tradition and its modern right-wing outgrowths. The supremacy of the state in the maintenance of law and order, in the imposition of taxes, in foreign relations, in the waging of war, and in many other ways is accepted more or less unquestioningly. In practice, collectivist ideologies such as socialism and individualist ideologies such as neo-liberalism differ only in degree. All are fundamentally collectivist. They all recognize social wholes, such as corporations, armies, and nation-states, all of which are more than the sum of their parts.

From the point of view of the hypothesis of formative causation, such social entities are organized by morphic fields. As in the case of other organized systems at all levels of complexity, from molecules to ecosystems, social fields are nested in hierarchies of fields within fields (Fig. 5.9).

Cultural inheritance

The word culture comes from the Latin root colere, to till or cultivate; in English the word still retains this primary meaning in agriculture. Just as agriculture involves the imposition of a new order on the Earth, which in its natural state is wild and uncultivated, so human culture is by implication not natural. It does not arise spontaneously in growing children; we are all inculturated or cultivated as we grow up. In this sense culture is opposed to nature.

But in another sense culture is natural; no human beings exist without culture, and cultures themselves can be compared to living organisms. They have forms that are inherited and reproduced again and again; they are self-organizing; and they change and evolve. The same ambiguity is inherent in agriculture itself: in one sense it is artificial, but in another sense the crops that are grown in the fields are natural; they have a life of their own; they develop in accordance with the natural rhythms of day and night, seasons and weather; and crops themselves and systems of agriculture change and evolve.

There is a general agreement that the inheritance of culture cannot be explained genetically.1 It is obvious that as babies grow up they learn the language of their natural or adoptive parents and assimilate the prevailing culture. Further, within a given society customs and traditions are passed on from generation to generation, and however this transmission occurs it can hardly be genetic. Edward O. Wilson, for example, confined the role of genetic evolution to the innate human capacity to develop one culture or another. ‘To the extent that the specific details of culture are non-genetic, they can be decoupled from the biological system and arrayed beside it as an auxiliary system.’2

Richard Dawkins took this approach further in proposing the concept of memes, which he defined as ‘units of cultural inheritance’.3 He compared them to genes:

Examples of memes are tunes, ideas, catch-phrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches. Just as genes propagate themselves in the gene pool by leaping from body to body via sperm and eggs, so memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain via a process which, in the broad sense, can be called imitation … As my colleague N.K. Humphrey neatly summed up, ‘memes should be regarded as living structures, not just metaphorically but technically.’4

Dawkins at first appeared to regard memes as atomistic units of cultural inheritance, just as he regarded genes as atomistic units of biological inheritance; and this aspect of his proposal was widely attacked by social scientists and anthropologists, most of whom think of cultures organismically, as wholes with coherent patterns of interconnection between their various elements. Dawkins responded by proposing the existence of ‘co-adapted meme complexes’, a term that Susan Blackmore shortened to ‘memeplex’.5

Morphic fields have some of the characteristics that Dawkins attributes to memes: they are ‘living structures,’ propagated within societies by a process that in a broad sense can be called imitation. But cultural morphic fields are not atomic units of culture; like all other types of morphic fields, they are structured in nested hierarchies of fields. And they are not passed on solely by imitation, but their acquisition is favoured by morphic resonance. Other things being equal, the more often a cultural morphic field has been realized, the greater the probability of its recurrence; it will become increasingly habitual.

The personal and mental life of every human being is shaped by culture, not least through languages and the cultural heritages that they embody: think, for example, of the differences between people brought up as Germans and Nigerians. And every human society has structures and patterns that are inseparable from the cultural heritage of that society. On the present hypothesis, as children grow up they come under the influence of various social morphic fields, and tune in to the chreodes of their culture, the learning of which is facilitated by morphic resonance. For example many American boys learn to play in baseball teams, and English boys in cricket teams. The social roles that people take up – the roles of secretaries, goalkeepers, bosses, workers, and so on – are shaped by morphic fields stabilized by morphic resonance with those who have played these roles before. Likewise, the patterns of relationship among the various social roles, for example between parents and children, are shaped by the morphic fields of the social unit, in this case the family, maintained by resonance from the group’s own past and from other more or less similar groups.

Theories of social and cultural organization

In the nineteenth century the primary preoccupation of social theorists was social change and development. The century began in the wake of the French and American revolutions, while in England the industrial revolution was gathering momentum. Social changes were unmistakeable realities, and sociology began in this context. Its founders, such as Henri de Saint-Simon and Auguste Comte, thought of society as a developing organism that could be understood in the positivistic spirit of science. Not only could society be understood in terms of sociological laws, but this knowledge could be used to control human behaviour, and in particular to help bring about the development of socialism. Against this background Karl Marx formulated his theory of social change through conflict between classes and attempted to discern the laws that developing societies would follow as they progressed towards the final communistic state, a classless society in which historical tensions disappeared. Class conflict was the ‘motor of history’, and the final achievement of communism would be the ‘end of ordinary history’.

Developmental theories of society were not the monopoly of the socialists and communists. Capitalistic theories also flourished, especially in Britain and America, where Herbert Spencer had a particularly strong influence. His primary interest was in social evolution, and he did much to popularize the general concept of evolution, leading rather than following Darwin in the use of this word (see above). But although Spencer emphasized the idea of society as an organism, he interpreted it in a paradoxically individualist manner. Society is an organism ‘whose corporate life must be subservient to the parts instead of the lives of the parts being subservient to the corporate whole’.6

Darwin and his followers emphasized the importance of competition between individual organisms in the struggle for survival. The principle of the survival of the fittest provided a seemingly scientific justification for capitalism and meant that inequalities in wealth, position, and power were inevitable. This principle was not, however, confined to individuals within a given society, but extended to entire social groups. Competition and conflict between groups was assumed to have raised the evolutionary level of society in general. This idea spawned a variety of speculative theories of social evolution collectively known as social Darwinism.7 Such theories had considerable political influence, and were commonly invoked in support of imperialism in general and the British Empire in particular. In the United States they provided a convenient explanation for the dominance of the ‘advanced’ white races and their expansion into the territory of the ‘primitive’ Red Indians; in Australia for taking over the land of the ‘backward’ aborigines; and so on. The following account of social evolution from the 1911 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica summarizes the general principles:

The first organized societies must have been developed, like any other advantage, under the sternest conditions of natural selection. In the flux and change of life the members of these groups of men which in favourable conditions first showed any tendency to social organization became possessed of a great advantage over their fellows, and these societies grew up simply because they possessed elements of strength which led to the disappearance before them of other groups of men with which they came into competition. Such societies continued to flourish, until they in turn had to give way before other associations of men of higher social efficiency. In the social process at this stage all the customs, habits, institutions and beliefs contributing to produce a higher organic efficiency of society would be naturally selected, developed and perpetuated.8

Different authors filled in the details of this general scheme as they saw fit; and here, as elsewhere, Darwinism lent itself to almost untrammelled speculation.

Functionalism and structuralism

There was a widespread reaction against this kind of armchair theorizing in the first few decades of the twentieth century, and many sociologists and anthropologists emphasized the need for the empirical study of societies as they actually are, regardless of how they came to be that way. The most popular theoretical framework for these studies was called functionalism, and it remained predominant in various forms until the 1960s. The primary metaphor was physiological: just as structures such as the heart, liver and kidneys serve the needs of the organism as a whole and maintain it in a more or less steady state, so also social institutions and activities function to maintain the society as a whole as it exists in its environment.

Closely akin to functionalism is systems theory, which provided the dominant model in sociology in the 1950s and 1960s.9 It emphasized the principles of interaction, feedback, and homeostasis, familiar on the one hand to physiologists and on the other hand to control engineers. Systems theory was strongly influenced by cybernetics, the theory of communication and control, and was applied in the study of political processes, industrialization and complex organizations. It provided the theoretical basis for computer models that came to be widely used in commercial, governmental, and military organizations.

The structuralist school grew up after the Second World War and had much in common with functionalism, sharing its assumption that societies are organic wholes. But instead of trying to explain all social and cultural structures in terms of their functions, structuralists attempted to discern the unobservable structures that underlay observable phenomena such as myths, systems of kinship, classifications, and patterns of exchange of goods. In several respects, structuralism superseded functionalism, which could be seen not so much as an opposing theory but as an early version of structuralism.10

The structuralist approach was widely influential in anthropology and sociology, and also in linguistics, especially through the work of Noam Chomsky (see above), in the study of art and literature, and as an approach to biological form.11 The mathematical models of morphogenetic fields of René Thom (see above), and Goodwin and Webster (see above) were put forward in a general structuralist context.

But what are these underlying structures? They sometimes sound very like Platonic Ideas or Forms. Some structuralists do indeed seem to belong to the Platonic or idealist tradition; others deny that they are idealists and seek to reduce these structures to physico-chemical mechanisms. The French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, for example, took the reductionist course, and referred the structures of culture and society to hypothetical mechanisms in the brain. His own intellectual development was much influenced during the 1940s by cybernetics and information theory. He proposed that the ‘algebra of the brain’ could be represented as a rectangular matrix of at least two (but perhaps several) dimensions that could be read up and down or side to side, like a crossword puzzle.12 The binary oppositions, represented by + and –, were comparable to the binary codes on which computers work. And so we come back once again to the computer metaphor for the human mind.

Both structuralism and functionalism faced a grave difficulty in so far as they implied that societies are harmoniously integrated organisms whose institutions serve to maintain a more or less steady state. Many societies and social institutions are far from harmonious and are not in equilibrium: they change. Think for example of the changes in Russia, in Brazil, in Kenya, or indeed anywhere else over the last century. Neither functionalism nor structuralism offered an adequate explanation of such changes; this was perhaps their greatest weakness, and a major reason for a decline in their influence. Explanations of social change in terms of conflict, competition and strain seem more plausible than functionalist theories of a social steady state, or structuralist theories of changeless patterns in the human mind. Meanwhile the empirical study of social change, for example in response to urbanization or rural development, became the main focus of many sociologists and anthropologists.

An interpretation of social and cultural patterns in terms of morphic fields provides a way of retaining the important insights of functionalism and structuralism while moving beyond a Platonist-reductionist dualism. Functionalism stresses the functional interrelations among the parts of a society, and structuralism the underlying patterns or structures. Both seem eminently compatible with the idea of morphic fields.13 Such fields structure human language, thought, culture, and society and organize the interrelations of the component parts. They are stabilized by self-resonance from a society’s own past and by morphic resonance from previous similar societies. Since morphic fields are probability structures, social and cultural regularities would be expected to be statistical in nature rather than precisely determinate, in accordance with the facts.

But what about social and cultural change? Morphic fields have a stabilizing and conservative effect; they cannot in themselves account for the initiation of change. Such changes depend on a variety of factors, including contact or conflict between different societies, classes, or cultural systems; on changes in the environment; on the spread of new technologies like television and mobile telephones; and so on. Here, as elsewhere, the origin of new fields depends on circumstances and on creative processes that cannot be explained in terms of repetition (see Chapter 18). But once new patterns of activity have arisen, the spread and adoption of these innovations may well be facilitated by morphic resonance. And often-repeated patterns of social change – in the processes of urbanization, for example – are shaped by chreodes and stabilized by morphic resonance.

Group minds

Intangible social influences are a matter of common experience. Many phrases in everyday language refer to them: the power of tradition, peer-group pressure, the force of conformity, and so on. All of us have experienced the feelings of shame that are associated with social disapproval and the positive feelings engendered by social approval; and we are familiar with the invisible influences referred to by terms such as solidarity, loyalty, morale, and team spirit.

Emile Durkheim, one of the founders of twentieth-century sociology, thought of such organizing influences as aspects of the conscience collective. The French word conscience embraces the meanings of both ‘consciousness’ and ‘conscience’ in English. He defined this as ‘the set of beliefs and sentiments common to the average members of a single society which form a determinate system that has a life of its own.’ It has its ‘own distinctive properties, conditions of existence, and mode of development.’ It transcends the lives of individuals: ‘they pass on and it remains.’14

Sigmund Freud, too, was driven to the conclusion that there are not just individual but collective minds:

I have taken as the basis of my whole position the existence of a collective mind, in which mental processes occur just as they do in the mind of the individual … Without the assumption of a collective mind, which makes it possible to neglect the interruptions of mental acts caused by the extinction of the individual, social psychology in general cannot exist. Unless psychical processes were continued from one generation to another, if each generation were obliged to acquire its attitude to life anew, there would be no progress in this field and next to no development. This gives rise to two further questions: how much can we attribute to psychic continuity in the sequence of generations? And what are the ways and means employed by one generation in order to hand on its mental states to the next one? I shall not pretend that these problems are sufficiently explained or that direct communication and tradition – which are the first things to occur to one – are enough to account for the process.15

Freud concluded that an important part of this collective mental inheritance was transmitted unconsciously.

William McDougall (who carried out the experiments on the inheritance of learned behaviour in rats described in Chapter 9) was an influential social psychologist who likewise came to the conclusion that societies have an autonomy that is best conceived of in terms of a group mind:

A society, when it enjoys a long life and becomes highly organized, acquires a structure and qualities which are largely independent of the qualities of the individuals who enter into its composition and take part for a brief time in its life. It becomes an organized system of forces which has a life of its own, tendencies of its own, a power of moulding all its component individuals, and a power of perpetuating itself as a self-identical system, subject only to slow and gradual change … We may fairly define a mind as an organized system of mental or purposive forces; and, in the sense so defined, very highly organized human society may properly be said to possess a collective mind. For the collective actions which constitute the history of any such society are conditioned by an organization which can only be described in terms of the mind, and which yet is not comprised within the mind of any individual; the society is rather constituted by the system of relations obtaining between the individual minds which are its units of composition.16

Ideas such as these had a widespread influence in the first few decades of the twentieth century, but were no longer respectable among Western intellectuals after the Second World War. This was partly because of the increasingly reductionist climate of the academic world, and also because of the frightening manifestations of the collective psyche in Nazi Germany and other nationalist movements. The idea of invisible organizing principles over and above the individuals within a society has, of course, remained, but they are referred to by more neutral terms such as patterns of relationship,17 social structures, and social consensus. These are, however, just as elusive as the group mind, and raise the same kinds of problems. Attempts to reduce them to mechanisms within the brains of individual people seem inadequate and unconvincing, while interpretations in terms of changeless Platonic Forms seem incompatible with changing historical reality. The hypothesis of formative causation enables these structures, patterns, and consensuses, together with the notions of the group mind and the conscience collective, to be embraced within the idea of morphic fields.

Collective behaviour

Collective behaviour is a term used by sociologists to refer to ‘the ways in which people behave together in crowds, panics, fads, fashions, crazes, cults, followings, reform and revolutionary social movements, and other similar groupings’.18 It has been defined as ‘the behaviour of individuals under the influence of an impulse that is common and collective, in other words, that is the result of social interaction.’19 Many studies have been made of the spread of rumours, jokes, fads and crazes, hysterical contagion, the behaviour of rioting mobs, and so on; but there are no generally agreed theories that can account for these phenomena.20

As we have seen, the behaviour of schools, flocks, herds, and packs of social animals suggests the idea that fields embrace all the individuals within them (Chapter 13). The idea of such fields of influence may also shed much light on human collective behaviour. Crowds, for example, have often been compared to composite organisms, with their own laws and properties. A useful classification of crowds by Elias Canetti distinguishes several types with quite distinct properties, which from the present point of view can be taken to represent different types of crowd field. One type is the open crowd:

The crowd, suddenly there where there was nothing before, is a mysterious and universal phenomenon … As soon as it exists at all, it wants to consist of more people: the urge to grow is the first and supreme attribute of the crowd … The natural crowd is the open crowd; there are no limits whatever to its growth; it does not recognize houses, doors or locks and those who shut themselves in are suspect … The open crowd exists so long as it grows; it disintegrates as soon as it stops growing.21

Canetti contrasts this extreme type of the spontaneous crowd with the closed crowd:

The closed crowd renounces growth and puts the stress on permanence. The first thing to be noticed about it is that it has a boundary … The boundary prevents disorderly increase, but it also makes it more difficult for the crowd to disperse and so postpones its dissolution. In this way the crowd sacrifices its chance of growth, but gains in staying power. It is protected from outside influences which would become hostile and dangerous and it sets its hope on repetition.22

But within crowds of both basic types there is equality: ‘it is for the sake of equality that people become a crowd and they tend to overlook anything which might detract from it’. Moreover, the crowd has a goal or direction: ‘A goal outside the individual members and common to all of them drives underground all the private differing goals which are fatal to the crowd as such. Direction is essential for the continuing existence of the crowd … A crowd exists so long as it has an unattained goal.’23

Crowds are temporary, and precisely for this reason can reveal to us some of the features of collective social organization that are so easily taken for granted in more permanent groups. Teams are another kind of temporary group of which most of us have had direct experience. Here too, although a team is more structured and disciplined than a crowd, the individual is subordinate to the collective behaviour directed towards a common goal – in many games, such as football, quite literally the scoring of goals. As Michael Novak expressed it:

When a collection of individuals first jells as a team, truly begins to react as a five-headed or eleven-headed unit rather than as an aggregate of five or eleven individuals, you can almost hear the click: a new kind of reality comes into existence … A basketball team, for example, can click in and out of this reality many times during the same game; and each player, as well as the coach and fans, can detect the difference … For those who have participated in a team that has known the click of communality, the experience is unforgettable.24

When successful sportsmen are questioned about their experiences as members of teams, some speak of a ‘sixth sense’ which enables them to be in the right place at the right time; others speak of empathy and intuition. In general, ‘an incredible power of communication often develops between members of a team where one can anticipate the moves of the other’.25

Such phenomena can be, and often are, interpreted in terms of group minds. An interpretation in terms of morphic fields provides an alternative that incorporates the group mind concept and in addition provides a natural explanation for the building up of group habits by morphic resonance from the group itself in the past and from other groups that resembled it. Think, for example, of the Manchester United football team, or the Boston Symphony Orchestra, or the local Methodist church: each has its own characteristic traditions and ethos and, at the same time, generic resemblances to other football teams, orchestras, or Methodist churches.

The collective unconscious

The collective unconscious of the psychologist Carl Jung has much in common with the concept of the group mind, and what Jung called the archetypes resemble what Durkheim called ‘collective representations’.26 Jung wrote as follows:

The collective unconscious is a part of the psyche which can be negatively distinguished from a personal unconscious by the fact that it does not, like the latter, owe its existence to personal experience and consequently is not a personal acquisition. While the personal unconscious is made up eventually of contents which have at one time been conscious but which have disappeared from consciousness through having been forgotten or repressed, the contents of the collective unconscious have never been in consciousness, and therefore have never been individually acquired, but owe their existence exclusively to heredity. Whereas the personal unconscious consists for the most part of complexes, the content of the collective unconscious is made up essentially of archetypes.27

One of the reasons why Jung adopted this idea was that he found recurrent patterns in dreams and myths that suggested the existence of unconscious archetypes, which he interpreted as a kind of inherited collective memory. He was unable to explain how such inheritance could occur, and his idea was clearly incompatible with the conventional mechanistic assumption that heredity depends on information coded in DNA molecules. Even if it were to be assumed that the myths of, say, a Yoruba tribe could somehow become coded in their genes and their archetypal structure be inherited by subsequent members of the tribe, this would not explain how a Swiss person could have a dream that seemed to arise from the same archetype. Jung’s idea of the collective unconscious did not make sense in the context of the mechanistic theory of life; consequently it was not taken seriously within orthodox science. But it makes good sense in the light of formative causation.

By morphic resonance, structures of thought and experience that were common to many people in the past contribute to morphic fields. These fields contain as it were the average forms of previous experience defined in terms of probability. This idea corresponds to Jung’s conception of archetypes as ‘innate psychic structures’:

There is no human experience, nor would experience be possible at all, without the intervention of a subjective aptitude. What is this subjective aptitude? Ultimately it consists in an innate psychic structure … Thus the whole nature of man presupposes woman both physically and spiritually. His system is tuned in to prepare for a quite definite world where there is water, light, air, salt, carbohydrates, etc. The form of the world into which he is born is already inborn in him as a virtual image. Likewise parents, wife, children, birth, and death are inborn in him as virtual images, as psychic aptitudes. These a priori categories have by nature a collective character; they are images of parents, wife and children in general … They are in a sense the deposits of all our ancestral experiences.28

Although Jung thought the collective unconscious was common to all humanity, he did not regard it as entirely undifferentiated: ‘No doubt, on an earlier and deeper level of psychic development … all human races had a common collective psyche. But with the beginning of racial differentiation essential differences are developed in the collective psyche as well.’29

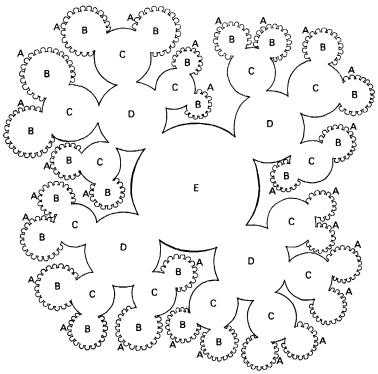

The psychologist Marie-Louise von Franz took this idea further (Fig. 14.1). Below the level of the personal unconscious lies a ‘group unconscious’ of families, clans, tribes and so on. Below this is a ‘common unconscious’ of wide national units: ‘We can see, for instance, that Australian or South American Indian mythologies form such a wider “family” of relatively similar religious motifs which, however, they do not share with all of mankind.’ Below this lies ‘the sum of those universal psychic archetypal structures that we share with the whole of mankind’.30

Figure 14.1 Diagram showing the structure of the collective unconscious as interpreted by von Franz. A, ego consciousness; B, personal unconscious; C, group unconscious; D, unconscious of large national units; E, unconscious common to all humanity, containing universal archetypal structures. (After von Franz, 1985)

Such a conception is in general agreement with the idea of morphic resonance, the specificity of which depends on similarity: members of particular social groups are in general more similar to past members of the same groups than to social groups of entirely different races and cultures; but underlying all human groups are general similarities through which all participate in a common human heritage.

Evolutionary psychology

From the 1990s, a cross-disciplinary movement linked together findings from evolutionary theory, anthropology, psychology, archaeology and computer theory under the banner of Evolutionary Psychology. Two of the leaders of this field, John Tooby and Lena Cosmides, summarized its principles as follows:

- The brain is a physical system. It functions as a computer with circuits that have evolved to generate behaviour that is appropriate to environmental circumstances.

- Neural circuits were designed by natural selection to solve problems that human ancestors faced while evolving into Homo sapiens.

- Consciousness is a small part of the contents and processes of the mind; conscious experience can mislead individuals to believe that their thoughts are simpler than they actually are. Most problems experienced as easy to solve are very difficult to solve and are driven and supported by very complicated neural circuitry.

- Different neural circuits are specialized for solving different adaptive problems.

- Modern skulls house a stone-age mind.31

The assumption that all inherited behaviour is genetic leads evolutionary psychologists to assume that adaptive ‘neural circuits’ were built up over very long periods of time through random mutation and natural selection. The mind is ‘like a Swiss army knife … constituted by multiple content-rich mental modules, each adapted to solve a specific problem faced by Pleistocene hunter-gathers’.32 All this is assumed to be genetically programmed. As Tooby and Cosmides put it: ‘Genes are the means by which functional design features replicate themselves from parents to offspring. They can be thought of as particles of design.’33 Because evolution by random mutation and natural selection are slow processes, they can have had almost no effect on the evolution of genetically inherited adaptive behaviour under the conditions of modern urban life in technological societies. Hence the idea that ‘modern skulls house a stone-age mind’, since the processes of natural selection that shaped the adaptive neural circuits took place over many generations when our ancestors were hunter-gatherers: ‘If our minds are collections of mechanisms designed to solve the adaptive problems posed by the ancestral world, then hunter-gatherer studies and primatology become indispensible sources of knowledge about modern human nature.’34

Evolutionary psychology agrees with the idea of morphic resonance in focussing attention on ancestral patterns that survive in the modern world long after conditions that helped shape them have changed. For example, an innate fear of snakes could be inherited by morphic resonance on the basis of many painful or dangerous encounters with snakes by our human and pre-human ancestors.35 And for millions of years, our ancestors were subject to predation by carnivores, and children were particularly susceptible. So it is an interesting fact that children’s first nightmares are often of devouring beasts, their most exciting games are of capture and pursuit, and bedtime stories include flesh-eating monsters. A survey of American five- and six-year olds found that their greatest fears were not of realistic dangers like germs or traffic accidents, but of wild animals, predominantly snakes, lions, tigers and bears.36

But there is no evidence that these fears are coded in genes and arose by random mutations. A collective memory through morphic resonance would provide a simpler explanation. Thinking of behavioural inheritance in terms of morphic resonance greatly increases the plausibility of evolutionary psychology as a general approach, and liberates it from its mechanistic dogmatism. Morphic resonance does not require habits of behaviour to be genetically programmed through random mutations and natural selection over many generations, and hence need not try and explain all hereditary aspects of human behaviour in terms of speculations about what happened in the Stone Age, allowing for little or no behavioural evolution since then. The morphic fields of behaviour are subject to natural selection, but their evolution can be rapid. New patterns of behaviour that have arisen in response to modern technology can be inherited by morphic resonance, and behavioural evolution can occur far faster than any genetic mechanism would allow.