14 |

Clinical and Laboratory Tests to Distinguish Conversion Disorder (Functional Neurologic Symptom Disorder) from Organic Disease |

Much will be gained if we succeed in transforming your hysterical misery into common unhappiness.

I. THE GENERAL CLINICAL FEATURES OF CONVERSION DISORDER (FUNCTIONAL NEUROLOGIC SYMPTOM DISORDER)

A. Definition of conversion disorder

Conversion disorder (functional neurologic symptom disorder, DSM-5, 2013) means a temporary disorder of mental, voluntary motor, or sensory functions that mimics neurologic disease but is caused by unconscious determinants, not by organic lesions in the neuroanatomic sites that should produce the dysfunctions (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The diagnosis of functional neurologic symptom disorder remains problematic for the clinician (Allanson et al, 2002; LaFrance, 2009; Nicholson et al, 2011). Table 14-1 reviews some common dysfunctions in patients with conversion disorder (functional neurologic symptom disorder). Malingering is not considered a mental illness.

TABLE 14-1 • Symptoms and Signs of Functional Neurologic Symptom Disorder

A. Mental 1. Pseudoepileptic seizures 2. Amnestic and fugue states B. Motor 1. Paralysis (monoplegia, paraplegia, or hemiplegia) 2. Hyperkinesia: tremors, flailing, and spasms 3. Astasia–abasia 4. Aphonia–dysphagia 5. Hyperventilation, often with dizziness and syncope; weak, shallow respiration; or grunting, demonstrative respiration 6. Blepharospasm, convergence spasm, pseudo-VIth nerve palsy, and ptosis C. Sensory 1. Anesthesia, paresthesia, hyperesthesia, or pain 2. Dimness of vision, tunnel vision and spiral fields, blindness, double vision, and photophobia 3. Deafness and dizziness 4. Globus hystericus 5. Multisystem complaints, especially gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and reproductive system/sexual/menstrual 6. Urinary retention |

B. Primary and secondary gain

Classic psychoanalytic theory holds that functional neurologic symptom disorders arise from unconscious mental mechanisms that relieve overwhelming anxiety by converting it into symptoms (Meyers and Volbrecht, 2003; Weintraub, 1995; Woolsey, 1976). The symptom provides primary and secondary gains for the Pt.

1. The primary gain consists of the relief of anxiety.

2. The secondary gains consist of manipulative control over the emotional responses, attention, and actions of other persons and relief from responsibilities. Apparently, the gains make the symptom more acceptable to the Pt than the anxiety that the symptom relieves.

3. Walker et al (1989) suggested that operant conditioning, with its theory of reinforcement of behavior by reward, provides an alternative paradigm to psychoanalytic theory. They stated “Simply put, those behaviors that obtain reward are those that are expressed.”

C. Distinction between conversion disorder, factitious disorder, and malingering

1. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) distinguished between conversion disorder factitious disorder, and malingering for Pts who had symptoms and signs not caused by organic disease (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The DMS-IV Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) recognized three main types of factitious disorders: (1) factitious disorders with predominantly psychological signs and symptoms, (2) factitious disorders with predominantly physical signs and symptoms, and (3) factitious disorders with combined psychological and physical signs and symptoms. Factitious disorder (formerly known as Munchausen syndrome) a chronic variant of factitious disorder with predominantly physical signs and symptoms means the deliberate production of signs and symptoms to assume the role of a sick person. Often the Pt has had multiple surgical procedures that have failed to disclose an organic lesion or to affect a cure (American Psychiatric Association; 2000).

2. A large spectrum of symptoms and signs, such as nonepileptic seizures and many chronic pain syndromes, can occur as a functional neurologic symptom disorder in one Pt or as malingering in another. Rather than debating the question of the conscious or unconscious origin of the symptoms, the examiner’s (Ex’s) immediate operational task is to differentiate the nonorganic disorders of whatever origin from the known and diagnosable organic disorders. This is always the first dichotomy in diagnosis: Is the disorder nonorganic or organic? (Is there a lesion? See Table 15-3.) Careful selection of terms is important because of medicolegal considerations and because Pts have access to their own medical records, and are entitled to an understanding, empathetic physicians (neurologists, psychiatrists, psychologists and general practitioners) working in collaboration. Criteria for functional neurologic symptom disorder (formerly known as conversion disorder) were modified to emphasize the essential importance of the neurological examination, and in recognition that relevant psychological factors may not be demonstrable at the time of diagnosis (DSM-5, 2013).

D. DSM-5 criteria for the diagnosis of functional neurologic symptom disorder

1. Learn Table 14-2.

TABLE 14-2 • Criteria for the Diagnosis of Functional Neurologic Symptom Disorder

1. |

The patient has ≥1 symptoms of altered voluntary motor or sensory function |

2. |

Clinical findings provide evidence of incompatibility between the symptoms and recognized neurological or medical conditions. |

3. |

The symptom or deficit is not better explained by another medical or mental disorder. |

4. |

The symptom or deficit causes clinically significant distress or impairment in sound, occupational, or other important areas of functioning or warrants medical evaluation. |

2. The medical history in functional neurologic symptom disorder

a. Women, usually between 10 and 35 years of age, predominate at about 3:1. However, the quoted ratio may reflect a diagnostic bias.

b. The history discloses longstanding personality problems, with some immediate emotional stress that triggers the index event. A history of other medically unexplained symptoms, predisposing emotional problems, and of the precipitating event is essential to the diagnosis of functional neurologic symptom disorder. Do not diagnose functional neurologic symptom disorder in a previously well-adjusted 60-year-old Pt who suddenly has neurologic symptoms. Always assume that such a Pt has organic disease until proven otherwise.

c. During the interview or neurologic examination (NE), when the Ex focuses on the dysfunction, such as a tremor, it worsens. The dysfunction also worsens in the presence of family members or significant acquaintances. The symptom varies with the attention directed to it or with the presence of emotionally significant people. It is socially dependent. Remember, however, that emotional stress may similarly enhance organic tremors and involuntary movements.

3. The diagnosis of functional neurologic symptom disorder rests on two pillars

a. Pillar 1: The negative pillar is the absence of neurologic signs that would have to be present if an organic lesion caused the disability.

b. Pillar 2: The positive pillar is the history of overt psychiatric stress and the complete resolution of the symptoms with time as the psychiatric problems resolve.

E. Affective status in functional neurologic symptom disorder

1. No single affect or personality pattern accompanies conversion disorder (Woolsey, 1976). Some Pts appear blandly indifferent (la belle indifférence) to the disability by accepting it stoically or good-naturedly, as it were. However, the usefulness of this clinical sign is controversial (Stone et al, 2006) and not useful in distinguishing between functional neurologic symptom disorder and organic disease. Pts do not ask about or seem concerned about the cause or prognosis.

2. In contrast to the bland indifference of some Pts, others with neurologically unexplained symptoms, particularly sensory ones, such as pain, overreact histrionically, with much wailing or dramatic prostration. The art of diagnosis—the art—is to recognize the disproportionate underreaction or overreaction.

3. Caveats for the history

a. In searching for psychiatric stressors, the naive Ex may overlook the high achiever syndrome. Consider the Super-Kid or All-American Kid syndrome. The Pt, a straight-A student, runs cross country in the fall, plays varsity basketball in the winter, plays Little League baseball, swims competitively in the summers, and receives the yearly citizenship award at school. After school hours, the child goes to choir practice and baby-sits for the mother on weekends. The overscheduling denies the child a childhood. In desperation, the child becomes paraplegic. In such a Pt, the unremitting excellence of function, maintained at too high a cost in psychic energy, constitutes the psychiatric predisposition.

b. Some Pts with multiple sclerosis, frontal lobe damage, anosognosia, abulia, or Anton cortical blindness may seem blandly unconcerned about their disability and its implications.

II. PSYCHOGENIC DISORDERS OF MOTOR FUNCTION

A. Range of motor disorders

1. The proposal has been made to change the term psychogenic movement disorder to functional movement disorder (Edwards et al, 2014). Somatoform disorders may cause paresis, paralysis, hypokinesia, or hyperkinesia. Handedness does not influence lateralization of the observed motor abnormalities, and unilateral motor and sensory symptoms are as common on either side of the body (Butler and Zeman, 2005; Stone et al, 2002). The hyperkinesias usually take the form of tremor, spasms, or flailing about. The paralysis may affect cranial nerve muscles, causing aphonia or dysphagia, or it may affect the rest of the body in monoplegic, hemiplegic, or paraplegic distributions. Motor conversion disorders presenting as quadriplegia virtually never occurs (Video 14-1).

Video 14-1. Psychogenic movement disorder.

2. Psychogenic impotence, a very common form of psychogenic dysfunction, does not qualify as functional neurologic symptom disorder, because it represents failure of autonomic function rather than volitional muscular activity.

B. Psychogenic oculomotor signs

1. Some oculomotor manifestations: Excessive blinking, squinting or blepharospasm, convergence spasm, pseudo-VI nerve palsy, and pseudoptosis.

2. Convergence spasm: The pupils constrict along with the forceful adduction of the eyes, indicating an overactive accommodation mechanism (Griffin et al, 1976). Review accommodation in Table 4-3.

TABLE 14-3 • Differentiation of Psychogenic and Organic Paraplegia

Nonorganic paraplegia |

Organic paraplegia |

|

Onset |

Usually arises suddenly after stress in a person with a psychiatric predisposition |

May evolve slowly or suddenly in a patient with a predisposing organic cause |

Attitude to illness |

May seem indifferent or histrionic |

Appropriate concern |

MSR |

Present and normal |

Absent in spinal shock or very brisk |

Clonus |

Absent or unsustained |

Sustained |

Muscle tone |

Normal |

Flaccid acutely, then spastic |

Plantar response |

Normal plantar flexion of great toe |

Dorsiflexion of great toe unless spinal shock is present |

Abdominal/cremasteric reflex |

Present |

Absent, depending on level |

Umbilical migration |

Absent |

Upward migration if lesion affects T10 (Beevor sign) |

Sensory level |

Extends horizontally around waist; variable; differs from motor level |

Slants obliquely downward; constant border if lesion static |

Inadvertent |

May move legs inadvertently for postural support, in sleep, or with Hoover test |

Does not move legs if the paraplegia complete but may show flexor spasms |

Sphincter control |

Present |

Lost |

Anal wink reflex |

Present |

Lost in stage of spinal shock |

MRI, SSEV, and cystometrogram |

Normal but usually not needed |

Abnormal |

ABBREVIATIONS: MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; MSR = muscle stretch reflex; SSEP = somatosensory evoked potentials. |

||

3. Pseudoabducens nerve palsy: The Pt, on attempting to look to one side, say the right, will move the eyes conjugately to, or a little past, the midline. Then the abducting, that is, leading, eye deviates inward, as if the lateral rectus muscle had failed. The adducting, that is, following, eye continues to progress to the right. Careful inspection will show that the Pt has learned to use convergence, as in volitionally looking cross-eyed. When the leading eye breaks from its abducting movement to the right, the pupils simultaneously constrict. Thus a volitional convergence stimulus has arrested the abduction of the eye, not weakness of the lateral rectus muscle (Troost and Troost, 1979). In organic VI nerve palsy, the failure of abduction does not cause pupilloconstriction.

4. Pseudoptosis: In organic ptosis, the Pt tends to lift the eyebrow up, using the action of the frontalis muscle. In pseudoptosis, the voluntary contraction of the orbicularis oculi causes the eyebrow to descend. The contraction of the orbicularis oculi muscle may be extreme enough to cause blepharospasm. Pts with pseudoptosis may also use mydriatic drops to dilate the pupil, further simulating a III nerve palsy (Keane, 1982).

5. Caveats: Blepharospasm more commonly occurs secondary to dystonia or to ocular inflammation with photophobia. When organic disease causes convergence spasm, the Pt usually has other midbrain and pretectal signs (Table 5-2). Tourette syndrome may cause a variety of tics affecting the eyelids and causing excessive blinking.

6. Describe some associated findings or neighborhood signs if an organic lesion causes convergence spasm.

_________

_________

7. Describe the critical finding that distinguishes a pseudoabducens palsy from an organic palsy.

_________

_________

C. Psychogenic dysfunctions of voice production, swallowing, and breathing

1. Range of dysfunction: Mutism or low voice volume, dysphagia, and respiratory dysrhythmias.

2. Psychogenic mutism: Pts with conversion muteness may exhibit complete mutism or speak with a low voice volume. Although aphonic, the Pt has normal vocal cord action during laryngoscopy or shows pure adductor palsy, but the Pt can produce a Valsalva maneuver or a normal strong cough, proving that the adductor muscles of the vocal cords can, in fact, act forcefully. The Pt has no palatal palsy, breathes and swallows normally, and may whisper with perfect articulation. The Pt may talk or phonate during sleep, thus establishing the integrity of the vocal apparatus.

3. Spasmodic dysphonia: When the Pt attempts to speak, the vocal cords go into spasm, causing a tight, hoarse, or strained voice (Aminoff et al, 1978).

4. Psychogenic dysphagia: The Pt chokes, or cannot swallow, but may have no accompanying signs of palatal, laryngeal, or pharyngeal dysfunction. The Pt swallows normally when asleep. The Pt may also experience globus hystericus, a distressing sensation of a lump lodged in the throat.

5. Respiratory dysrhythmias: Disorders include apnea, often in association with a Valsalva maneuver, hyperventilation, weak, shallow, or “asthenic” breathing in a Pt who avoids eye contact, or theatrical gagging, with guttural noises, stridor, rolling of the head and trunk and demonstrative, expressive eyes (Walker et al, 1989). Walker and colleagues (1989) likened the latter state of respiratory gymnastics to astasia and abasia: in both states, the Pt flirts with disaster but escapes. Hyperventilation may accompany or precede hysterical symptoms such as dizziness in Pts with somatic symptom disorder. Most Pts with psychogenic breathing disorders show no cyanosis and have a normal arterial O2 but, if misdiagnosed, may be mistakenly intubated (Walker et al, 1989).

6. Caveats: Dystonia may cause spasmodic dysphonia. Early stages of several organic diseases—such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and myasthenia gravis—may cause dysphonia and dysphagia without other signs early in the course of the diseases. Always consider myasthenia gravis when the Pt has any unexplained weakness of bulbar muscles. Semirhythmic contractions of the abdominal wall and diaphragmatic flutter may be secondary to “belly dancer’s” dyskinesia (Iliceto et al, 2004). Dyphagia lusoria may be associated with an aberrant right subclavian artery. A review of patients previously diagnosed with psychogenic dysphagia showed that a medical cause was found in two-thirds of cases (Ravich et al, 1990).

D. Psychogenic vomiting

In Pts with functional neurologic symptom disorder, the vomiting occurs mainly in the presence of emotionally significant people. Some Pts may simulate gastrointestinal bleeding by secretly adding blood to their vomitus or stool. The Pt with anorexia nervosa or bulimia vomits in the bathroom or in secret.

E. Psychogenic disturbances of station and gait

1. General features of astasia–abasia: Most common gait disorders are hemiparetic, paraparetic, ataxic, or trembling gait (Keane, 1989), and astasia–abasia. Astasia means the inability to stand, and abasia means the inability to walk. Taken together the two words imply total inability to stand and walk, but often with the Ex’s suggestion the Pt may attempt to do so (Keane, 1989). Patients with atasia–abasia show wild gyrations when standing or walking. The Pt rarely falls, or falls into the Ex’s arms (or a chair) without suffering bodily injury. The flamboyant gyrations without falling testify eloquently to the competency of the Pt’s motor system and balance (Video 14-2). When in bed or sitting, the Pt may show no disability or only minor disturbances of movement. On the Romberg test, the Pt will usually sway much more with the eyes closed.

Video 14-2. Psychogenic gait.

2. Hemiparetic and hemiplegic gaits: In psychogenic hemiplegia, the lower part of the face ipsilateral to the hemiplegia is not involved; the protruded tongue, if it deviates at all, deviates toward the normal side (Keane, 1986). Tongue deviation is uncommon in organic hemiplegia, but when it occurs the deviation is to the hemiplegic side. The arm and leg do not assume true hemiplegic postures when the Pt is at rest or when walking (Fig. 12-15; Keane, 1989). The leg of the organic hemiplegic turns outward when the Pt is recumbent. The abdominal, plantar, and muscle stretch reflexes are always normal. The hand is not preferentially affected as in organic hemiparesis.

3. Dragging monoplegic gait: The Pt walks with the good leg forward and the monoplegic limb dragging behind. The foot may be turned out or inverted or everted (Stone et al, 2002). Sudden buckling of the knee is also common.

4. Psychogenic paraplegia: Key differences on the NE are the presence of normal abdominal or cremasteric, muscle stretch, and plantar reflexes, normal muscle tone, and retention of bowel and bladder control in psychogenic paraplegia and their usual impairment in organic paraplegia (Baker and Silver, 1987).

a. Sensory changes tend to be highly variable, may not match the motor level, and do not show the dissociated loss between anterolateral and dorsal columns or the sacral sparing that may characterize organic paraplegia (Table 14-3).

b. The T10 level of the spinal cord supplies the umbilical level of the abdomen (Fig. 2-10). With organic paraplegia from a T10 level lesion, the skeletal muscles of the lower two quadrants of the abdomen are paralyzed along with all other muscles distal to T10. The upper quadrant skin-muscle reflexes will be preserved but absent in the lower two quadrants. The Pt shows Beevor sign when attempting to do a sit-up, that is, the intact upper quadrant abdominal muscles cause the umbilicus to migrate upward because of no corresponding anchoring pull from the muscles of the paralyzed lower quadrants. This sign never occurs in psychogenic paraplegia.

5. Caveats: Recall that Pts with the rostral or caudal vermis syndromes may show little dysfunction when reclining but display dystaxia when walking, particularly when tandem walking. Camptocormia (bent spine syndrome), initially attributed to a psychogenic disorder, can have many causes including a variety of neuromuscular disorders, flexion dystonia of the trunk, axial myopathy, and parkinsonism. The disorder is characterized by forward flexion of the trunk present in the standing position, increasing during walking, and abating in the supine position (Lenoir et al, 2010) Patients with involuntary movement syndromes, in particular dystonia musculorum deformans, frequently get diagnosed as having a psychogenic disorder in the early stages of their illness. Astasia–abasia has also been related to normal pressure hydrocephalus. Status cataplecticus (“limp man syndrome” due to narcolepsy has been mistaken for a psychogenic disorder (Simon et al, 2004). See the gait essay at the end of Chapter 8.

F. Techniques and observations that separate psychogenic paresis or paralysis of trunk and limbs from organic paralysis

1. Demeanor of the Pt: The Pt’s demeanor during testing of strength often provides a clue to psychogenic weakness. Usually the Pt with psychogenic paralysis makes a great show of effort to move the afflicted part, but to no avail. Thus, the Pt may grimace, grunt, or squirm, and show obvious strain, but the part does not move. It is a dramatic performance meant to communicate sincerity of effort, rather than a simple attempt to move the part, as in organic paralysis. The patient with somatic symptom disorder with partial paralysis usually moves the part very slowly. Often the Ex can see and feel that the putatively weak muscles in such a movement in fact contract very strongly. Thus, in grip testing, the Pt often co-contracts the flexors and extensors very strongly, demonstrating intact innervation, which the Ex can see and palpate. Because the Pt contracts all muscles isometrically, the Pt’s fingers only encircle the Ex’s fingers very lightly, not actually closing tightly on them. When the Ex tugs against a muscle to test strength, the Pt may offer considerable resistance and then yield suddenly, or may show a series of jactitating, cogwheel-like releases. Objective recording of strength by myometry shows different patterns of contractions in psychogenic weakness, normal individuals, and organically paralyzed Pts (van der Ploeg and Oosterhuis, 1991).

2. Distribution of psychogenic paralysis: Although the psychogenic paralysis may follow monoplegic, hemiplegic, or paraplegic distributions, it seldom affects individual muscles or groups of muscles innervated by one peripheral nerve or root. The limbs do not assume organic postures, as in organic hemiplegia, and the overall lack of signs, particularly the normal reflexes, establishes the psychogenic nature of the paralysis.

3. Eliciting inadvertent or automatic movements (synkinesias) of the paralyzed parts in psychogenic motor disorders

a. Sleep: Several inadvertent or synkinetic movements establish the integrity of the putatively paralyzed part. The Pt with psychogenic monoplegia, hemiplegia, or paraplegia moves the parts in the normal manner during sleep. When dressing the Pt may inadvertently reach out with the affected part or use it automatically for postural support. This is a key principle: The Ex finds some way to activate the putatively paralyzed muscles inadvertently or synkinetically.

b. Monrad-Krohn cough test for arm monoparesis (1922): To identify psychogenic paralysis of the arm, the Ex stands behind the Pt and grasps the two latissimus dorsi muscles between the thumb and fingers of the right and left hands. The Ex asks the Pt to cough forcefully. Both latissimus dorsi muscles synkinetically contract strongly, thus establishing the integrity of the motor pathway through the brachial plexus.

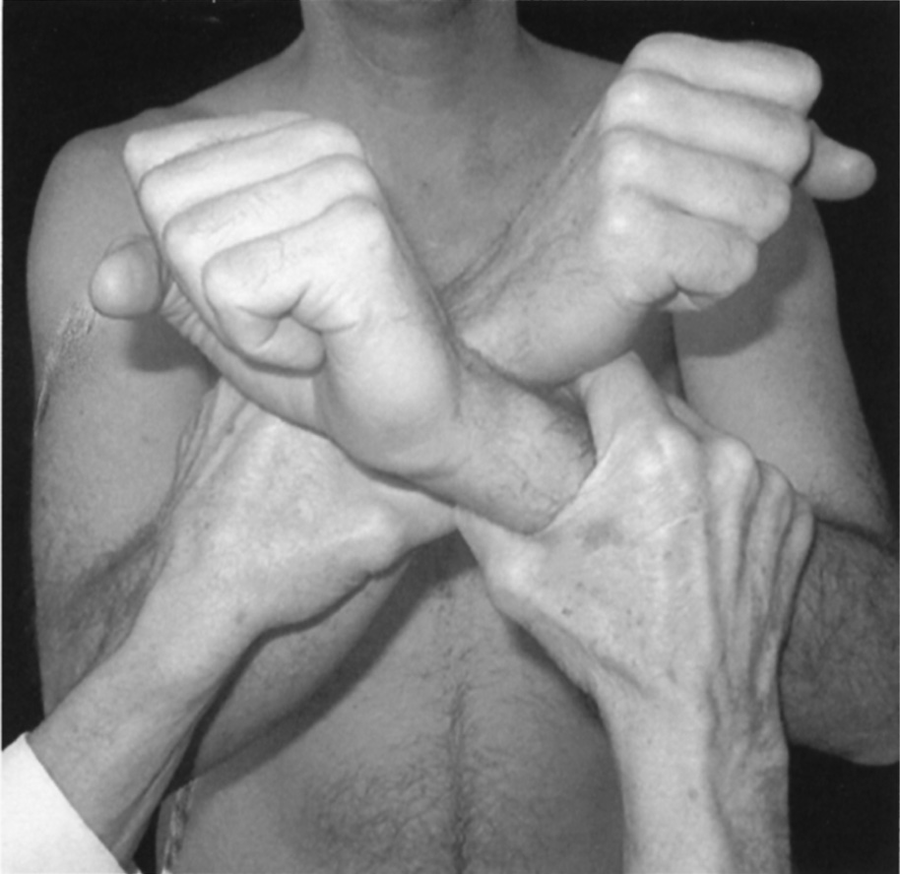

c. Double-crossed-arm pull test for psychogenic arm monoparesis

i. When required to use both sides simultaneously and unexpectedly, the psychogenic Pt will generally inadvertently contract the putatively weak side along with the normal side.

ii. Start with the Pt upright and the forearms crossed and flexed (Fig. 14-1). If the Pt’s arm is completely paralyzed, hold it in place.

iii. While holding the Pt’s forearms as shown in Fig. 14-1, say: “When I say now, try to pull back strongly away from me, and I will hold you in place.” Then say now after a brief pause. Usually, the Pt braces the paretic and nonparetic arms when pulling back.

FIGURE 14-1. The double-crossed-arm pull test for psychogenic paresis of one arm. The examiner’s hands grip the patient’s forearms. See text for instructions.

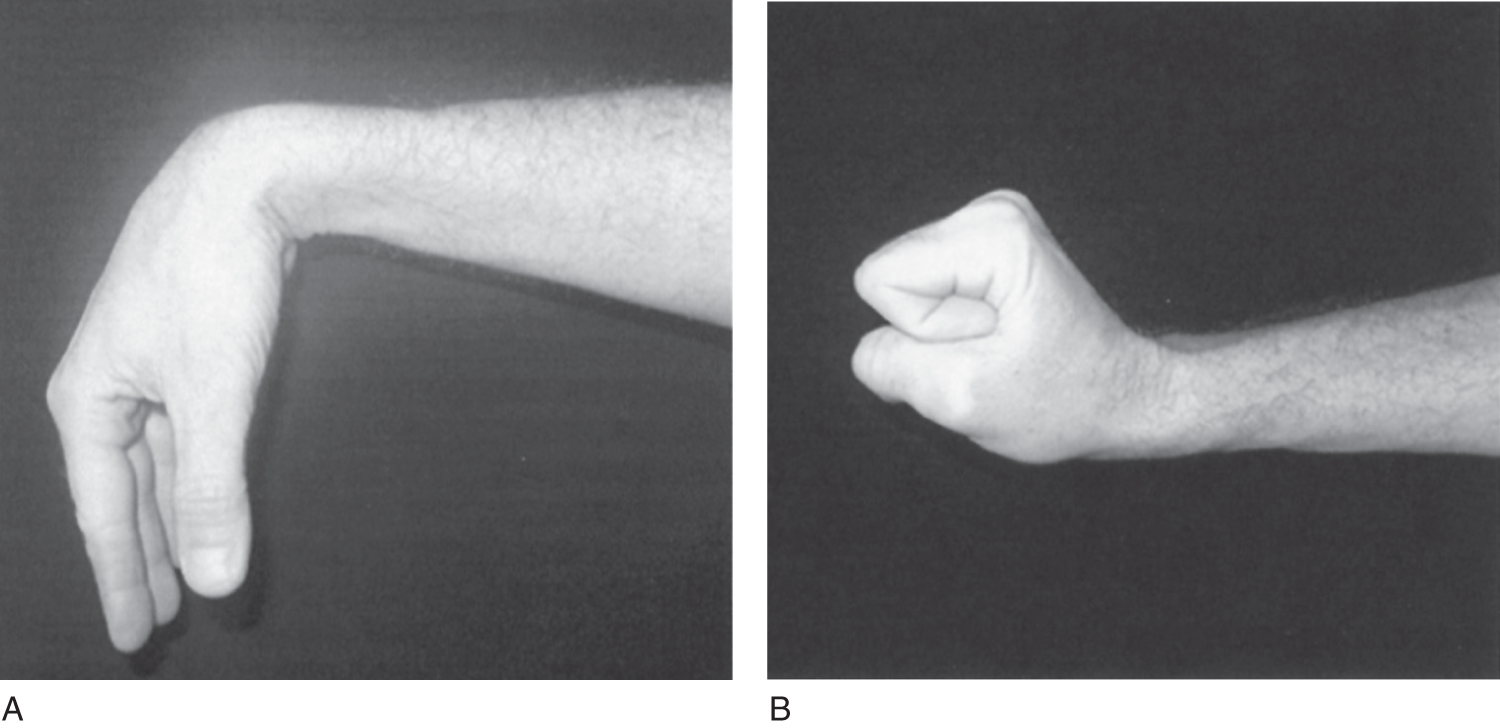

d. Make-a-fist test for psychogenic wrist drop

i. To distinguish a psychogenic wrist drop from a radial nerve palsy, ask the Pt to extend the arm out straight. The putatively paralyzed wrist hangs limply (Fig. 14-2A).

ii. Instruct the Pt to suddenly make a strong fist when you say now.

iii. If intact, the putatively paralyzed wrist extensors automatically cock the hand up into the “anatomic position” when the Pt makes a fist (Fig. 14-2B). Try this test yourself. In a true radial palsy, the wrist does not cock up.

iv. As a refinement of the test, ask the Pt to grip a screwdriver or rod strongly or to grip the rod strongly with both hands simultaneously.

FIGURE 14-2. Make-a-fist-test for psychogenic wrist drop. (A) With the forearm extended, the patient has an apparent wrist drop. (B) When the patient makes a fist, the wrist automatically dorsiflexes, proving that the extensor muscles are intact.

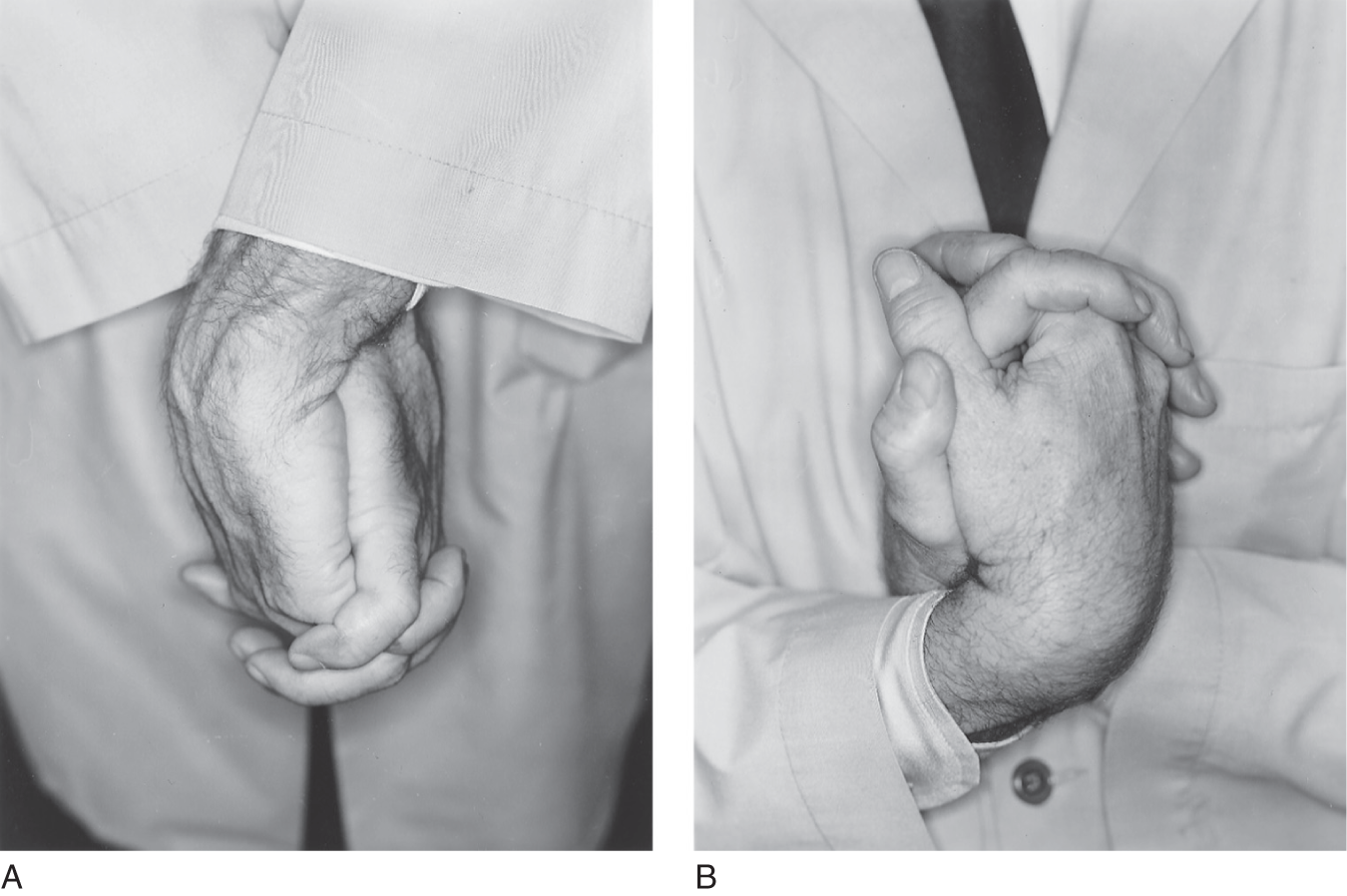

e. Reversed hands test for arm monoparesis

i. To identify psychogenic hand paralysis, the Ex has the Pt reverse and invert the hands (Figs. 14-3A and 14-3B).

ii. Then ask the Pt to look at the fingers. The Ex then points to but does not touch a finger and asks the Pt to move that finger. Usually, the Pt moves the finger of the hand opposite to the one pointed to by the Ex. Try this test on a partner. After a few trials, the subject learns to respond accurately. Thus, the test serves best during the first trials. The test also works for psychogenic anesthesia. With the Pt’s eyes closed, the Ex actually touches the finger of one hand or the other. The Pt usually moves the finger of the putatively anesthetic hand.

FIGURE 14-3. Inverted-hands test for psychogenic loss of sensation or motor function. (A) Clasp fingers as shown, with hands crossed and palms together. (B) Invert the hands. The final posture in B reverses right for left. See text for further Instruction.

f. Backward displacement test for psychogenic foot drop

i. To distinguish a psychogenic foot drop from a peroneal nerve palsy, ask the Pt to stand with the eyes closed.

ii. Place one hand flat on the Pt’s sternum and suddenly displace the Pt backward, using the other hand on the Pt’s back to prevent a fall.

iii. The Ex will see the dorsiflexor tendons of the feet spring into action as the Pt automatically reacts to the displacement.

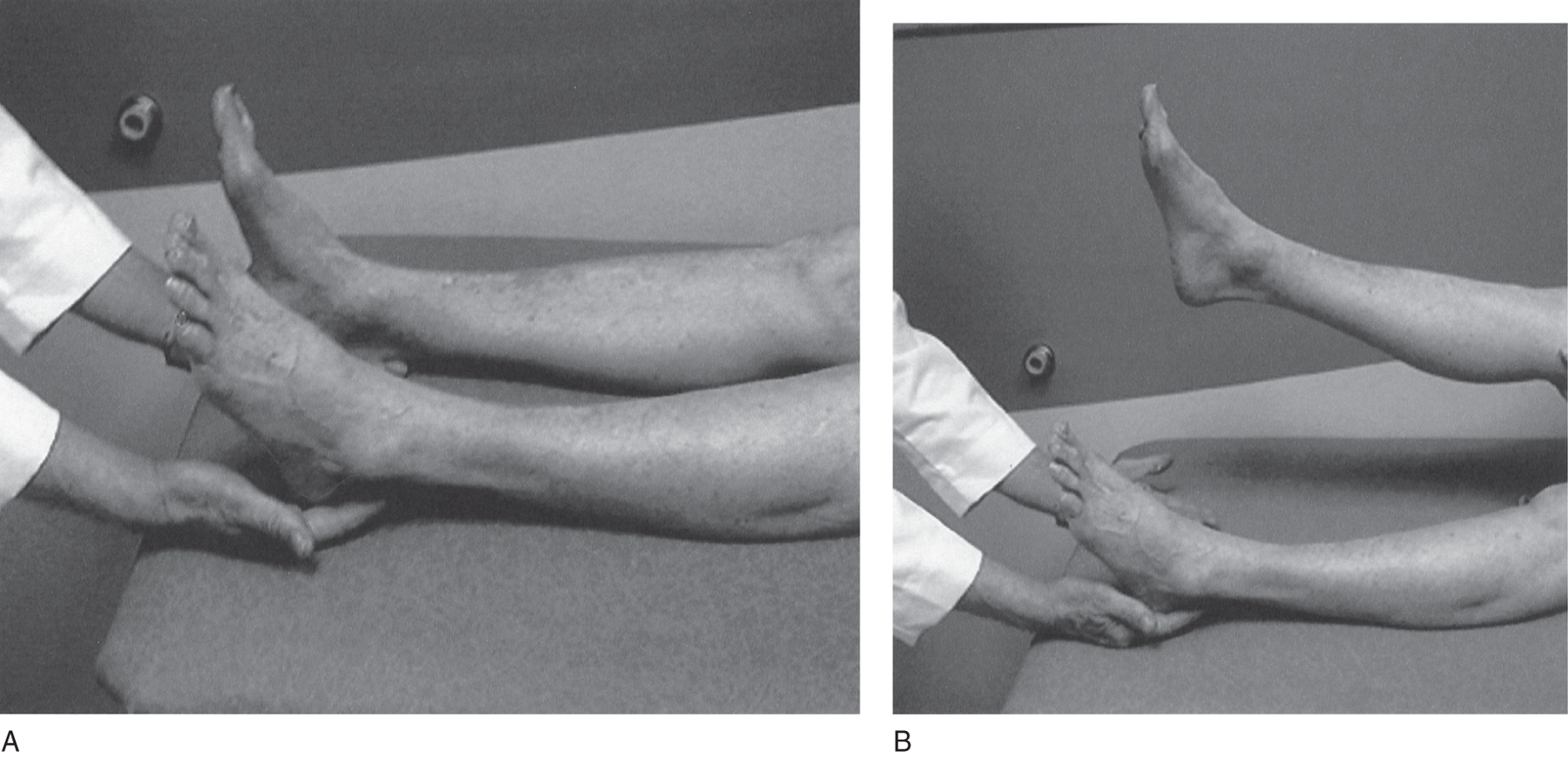

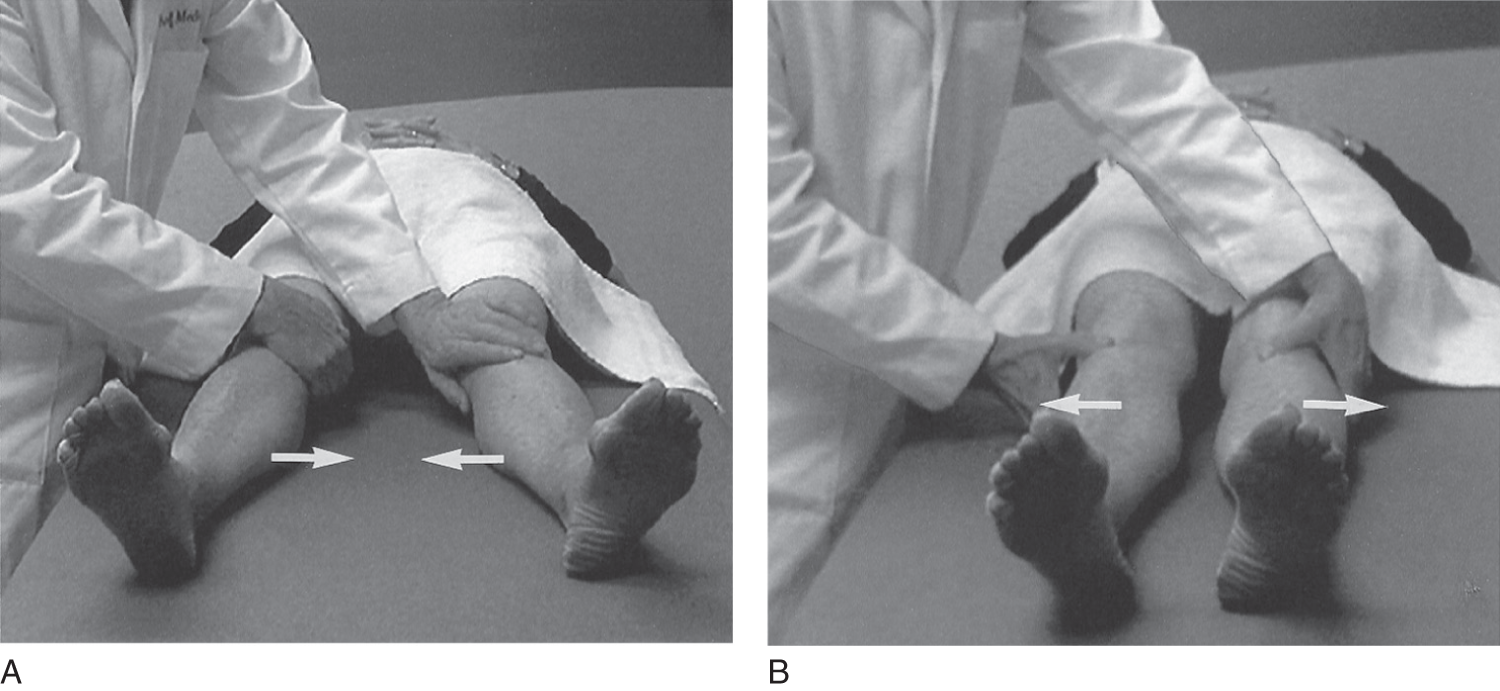

g. Hoover test for psychogenic leg monoparesis

i. With the Pt recumbent, stand at the foot of the examination table with one palm under each of the Pt’s heels (Fig. 14-4A).

ii. Ask the Pt to press down with the putatively paretic leg. The heel will not press down on the Ex’s palm.

iii. Ask the Pt to lift the normal leg up briskly in one motion. The paretic leg will press down against the Ex’s palm as an automatic, synkinetic counteraction that the Ex can feel and see (Fig. 14-4B; Stone et al, 2002).

iv. Ask the Pt to press down with both heels. Usually the Pt with psychogenic paralysis presses down with both heels, whereas the Pt with organic paralysis does not.

v. As a refinement of this test, place one hand under the paralyzed limb, press down on the knee of the sound limb, and instruct the Pt to lift it as strongly as possible. The putatively paralyzed limb will synkinetically press down.

FIGURE 14-4. Hoover leg-elevation test for psychogenic paralysis of one leg. The examiner places a hand under each of the patient’s heels. Then the examiner asks the patient to forcefully raise the normal leg. The patient will inadvertently push down with the putatively paralyzed leg.

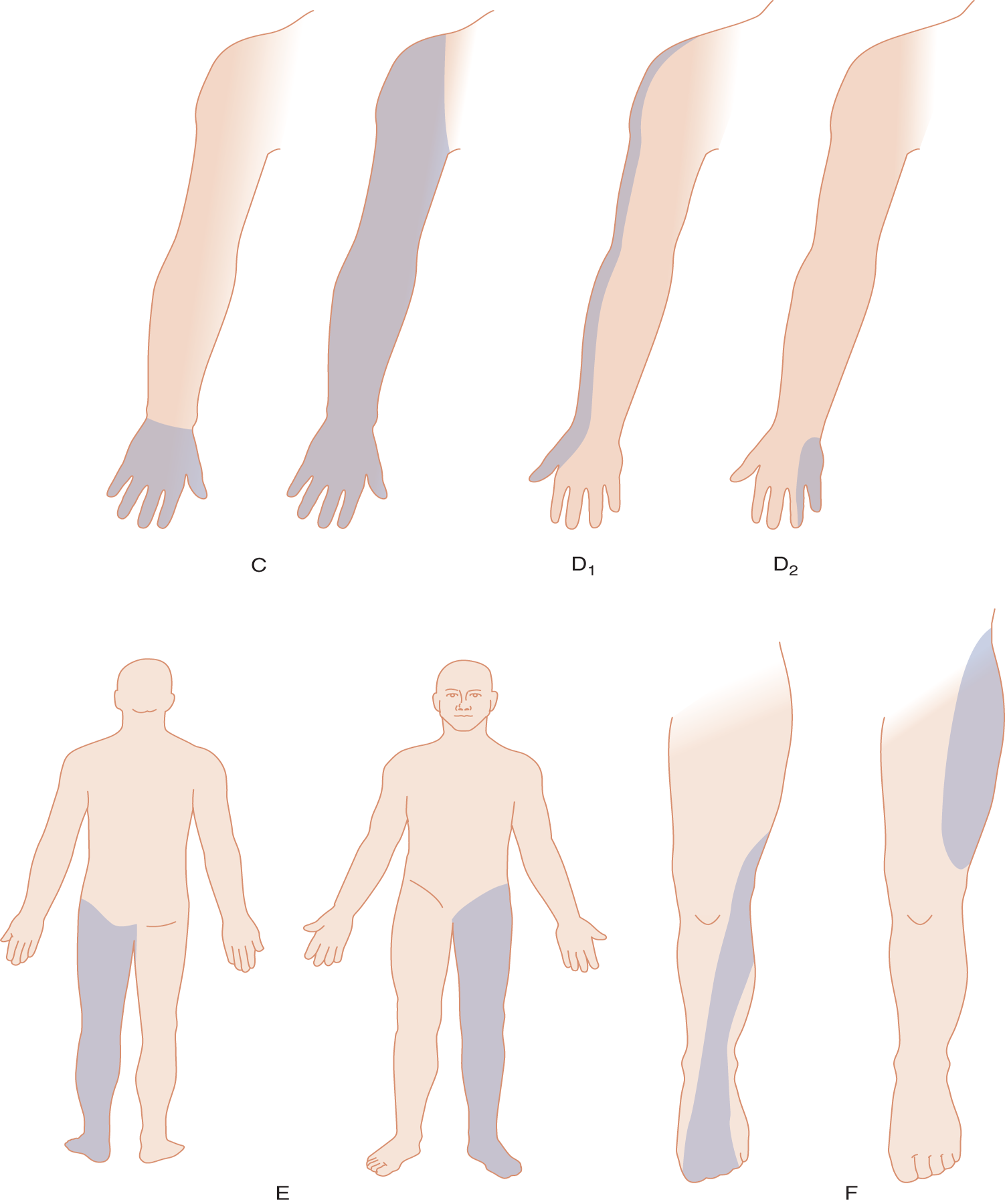

h. Raimiste leg adduction–abduction synkinesis for psychogenic leg monoparesis

i. The same principle of inadvertent synkinetic bracing of the putatively paralyzed part applies in testing adduction and abduction of the legs.

ii. With the Pt recumbent, place your hands on the Pt’s knees and ask the Pt to squeeze the legs together strongly as you hold your hands in place, in opposition to the Pt’s action (Fig. 14-5A).

iii. The Pt usually braces the putatively paralyzed limb in automatic opposition to the action of the intact limb.

iv. Similarly, ask the Pt to press the legs apart strongly against your manual resistance. The putatively paralyzed limb usually will abduct in automatic opposition (Fig. 14-5B).

FIGURE 14-5. Raimiste leg-adduction and -abduction test for psychogenic leg paresis. (A) The patient tries to adduct, that is, squeeze both legs strongly together (arrows) against the examiner’s manual opposition. (B) The patient tries to abduct, that is, separate both legs strongly (arrows) against the examiner’s manual opposition. In each case, the patient synkinetically braces the putatively paretic leg.

4. Review of formal tests to produce synkinetic movements of putatively paralyzed muscles in Pts with psychogenic weakness

a. Describe the Monrad-Krohn cough test for psychogenic brachial plexus/arm paralysis. _________

b. Name the muscle tested in the foregoing test _________

c. Test for psychogenic arm monoparesis (double pull test).

_________

d. Test for psychogenic wrist drop.

_________

e. What major nerve, when interrupted, causes a wrist drop? _________

f. Test for psychogenic foot drop._________

g. What major nerve, when interrupted, causes a foot drop?

_________

h. Test for psychogenic leg monoparesis (Hoover test). _________

i. Describe how to do Raimiste adduction–abduction test for psychogenic leg paralysis._________

_________

j. Try all of the foregoing tests on a companion.

5. Magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex can move the putatively paralyzed limb, thus proving that the pyramidal and peripheral pathways are intact (Pilai et al, 1991).

G. Psychogenic tremors

The tremor varies greatly in intensity and frequency and is present at rest, during a sustained posture, and during movement, in contrast to most organic tremors (Koller et al, 1989), midbrain or so-called rubral tremor excepted (Reza Samie et al, 1990). See Chapter 7 and Table 14-4.

TABLE 14-4 • Clinical Features of Psychogenic Tremor

1. |

Abrupt onset |

2. |

Static course |

3. |

Spontaneous remissions |

4. |

Unclassifiable tremors (complex tremors) |

5. |

Clinical inconsistencies (selective disabilities) |

6. |

Changing tremor characteristics |

7. |

Unresponsiveness to antitremor drugs |

8. |

Tremor increases with attention |

9. |

Tremor lessens with distractibility |

10. |

Responsiveness to placebo |

11. |

Absence of other neurologic signs |

12. |

Remission with psychotherapy |

SOURCE: Reproduced with permission from Koller W, Lang A, Vetere-Overfield B, et al. Psychogenic tremors. Neurology. 1989;39:1094–1099. |

|

III. PSYCHOGENIC DISORDERS OF VISION

A. Range of symptoms

The visual symptoms consist of diminished vision or blindness, nonanatomic visual field defects, diplopia, and photophobia.

B. Psychogenic blindness

1. Establishing the integrity of the visual pathways

a. The Pt retains pupillary light reactions, and the fundi appear normal.

b. The Pt has no signs of cerebral lesions extensive enough to cause cortical blindness and no history compatible with such lesions.

c. The organically blind Pt moves cautiously and slowly, rarely banging into objects. Psychogenically blind persons may bang into objects, as if to prove they cannot see.

d. The eyes of the psychogenically blind Pt may glance at a moving object that appears unexpectedly. Placing a mirror directly in front of the Pt and moving it may cause the Pt’s eyes to pursue their reflection. The Pt may show optokinetic nystagmus (railroad nystagmus) when exposed to a rotating drum or moving stripes. However, Pts can inhibit optokinetic nystagmus. Its presence thus establishes the integrity of the retinogeniculo-calcarine pathway and the efferent optomotor pathway to the brainstem from the occipital cortex, but the absence of nystagmus does not prove that the Pt has a lesion.

e. If the Pt has monocular psychogenic blindness, the swinging flashlight test will not demonstrate an afferent defect (Chapter 4, Section VI A 5).

f. The Ex may induce the Pt to have double vision by applying canthal compression (Fig. 4-4), or the ophthalmologist can use prisms to prove that the putatively blind eye sees. Different colored lenses on each eye serve the same purpose (Liu et al, 2001).

g. Electrical tests: The electroretinogram in patients with psychogenic disorders of vision remains normal, the electroencephalogram (EEG) shows a photic driving response, and visual evoked potential studies prove that impulses reach the visual cortex (Chapter 13).

2. Caveats

a. Even evoked responses are not beyond manipulation, because the Pt’s thoughts can change the pattern evoked (Bumgartner and Epstein, 1982; Tan et al, 1984).

b. Acute retrobulbar neuritis can cause acute, complete blindness in an eye with a normal-appearing fundus before optic atrophy sets in. The diseased eye will show a diminished or absent direct pupillary light reflex, and the opposite pupil will fail to show a consensual reflex. The swinging flashlight test will show the afferent defect (Chapter 4, Section VI A 5).

c. In Anton syndrome, a bilateral, occipital lobe lesion causes bilateral cortical blindness, but the pupillary responses remain intact. Although obviously blind, the Pt confabulates vision, describing nonexistent scenes around him. The disorder qualifies as an anosognosia for blindness. During the diaschisis that may follow an acute, severe unilateral occipital lobe lesion, Anton syndrome may occur temporarily. In these cases, magnetic resonance imaging will show the cerebral lesion.

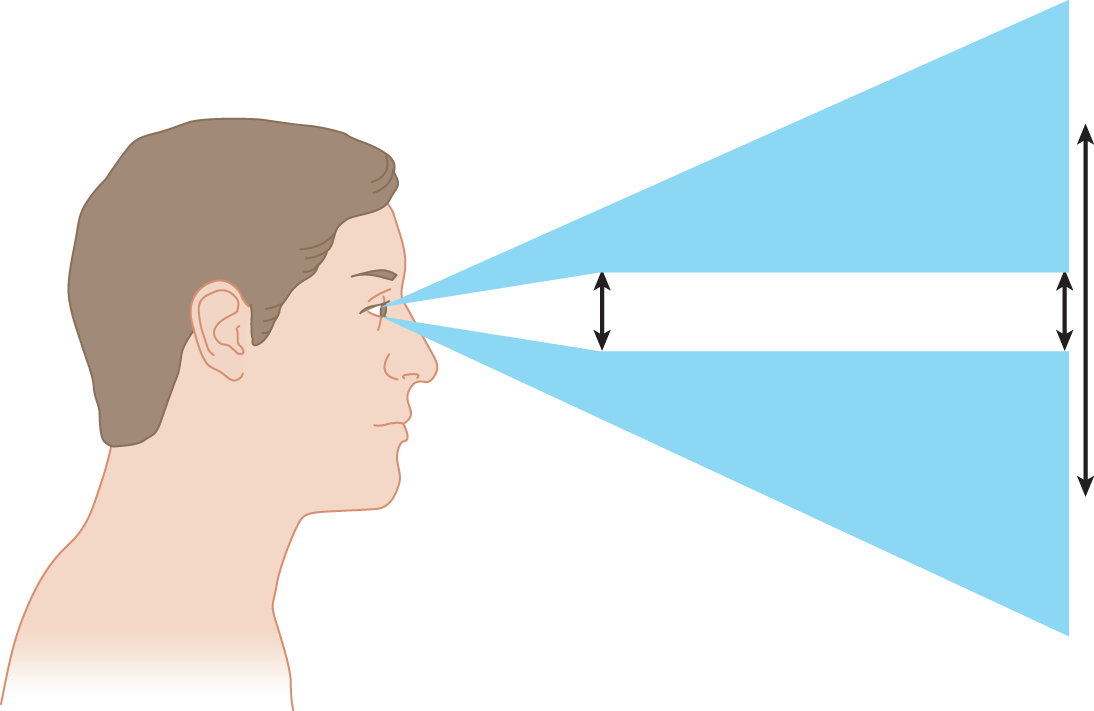

C. Psychogenic visual field defects

The typical psychogenic visual field defect consists of constriction of the diameter of the field, thereby producing tunnel or tubular vision, as if the person were looking through a tunnel. In a closely allied phenomenon, the spiral visual field, the size of the field diminishes on successive trials. In tunnel vision, the visual field remains the same diameter for near and far objects (Fig. 14-6).

FIGURE 14-6. Illustration of tunnel vision in a patient with hysteria. The normal visual field expands. In tunnel vision the field remains the same size for targets at different distances.

D. Monocular diplopia

1. The spectrum of psychogenic ophthalmologic manifestations include monocular diplopia. The diplopia will not follow any of the laws of diplopia (Chapter 4), the corneal light reflections remain aligned, and the cover–uncover test remains normal.

2. Caveat: A dislocated lens; a fold, detachment, or elevation of the retina; or a hole in the iris may cause organic monocular diplopia, but the ocular examination and ophthalmoscopy easily differentiate these conditions.

E. Photophobia

Pain in the eyes on exposure to light may occur with hysteria or with organic illnesses, for example, iritis. Careful slit-lamp examination and ophthalmologic investigation must rule out definable organic disease.

IV. PSYCHOGENIC DEAFNESS

A. Clinical and laboratory tests to establish the integrity of the auditory pathway

The psychogenically deaf Pt may turn when addressed unexpectedly from the side or may show a startle response to sudden sound when awake or asleep. The presence of a response indicates an intact auditory pathway, but absence of a response does not establish organic deafness. The tuning-fork tests of Weber and Rinne described in Chapter 9 may produce bizarre results. Audiologists have several methods of manipulating sound to recognize hysterical deafness, which, combined with the brainstem evoked response test (Chapter 13) showing evoked potentials recorded over the auditory cortex, document the integrity of the auditory pathways.

B. Caveat: acute viral illness, vascular occlusion, or pontine tegmental lesions can cause sudden deafness, with no other evidence of neurologic disease

V. PSCHOGENIC DISORDERS OF SOMATIC SENSATION

A. Range of disorders

Patients with psychogenic somatosensory disorders may complain of anesthesia, paresthesia, hyperesthesia, or pain in the body or extremities. The anesthesia usually affects all sensory modalities. If the Pt loses one modality, it usually affects touch or pain, not vibration or position sense.

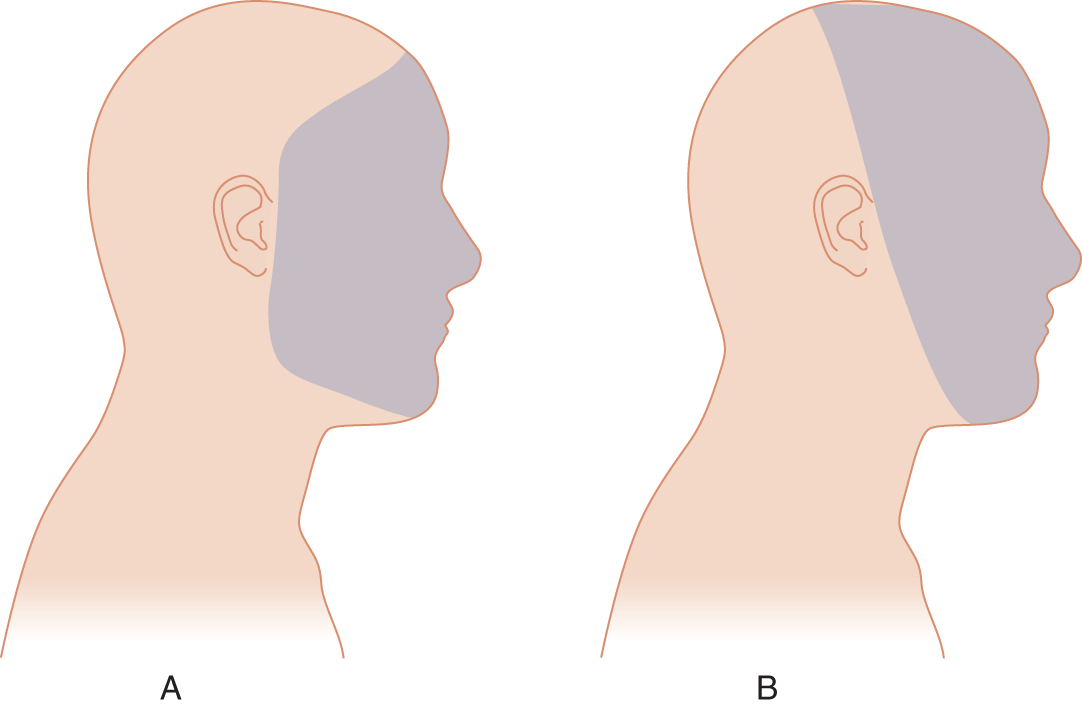

B. Nonanatomic distribution of psychogenic sensory loss

1. Psychogenic sensory losses follow nonanatomic distributions and often have variable but very sharp borders from examination to examination. Psychogenic sensory losses conform to the Pt’s mental image of the body, not to the actual anatomic pattern of innervation by peripheral nerves, nerve roots, or central pathways (Fig. 10-3). Chapter 10 explained how organic facial anesthesia from a V nerve lesion spares the angle of the mandible, which receives its sensory innervation from C2. See Figs. 10-2 and 14-7A.

2. In psychogenic anesthesia of an extremity, the loss usually includes the hand or foot and extends proximally to stop abruptly at a line transverse to the long axis of the limb, as if the extremity were amputated (seemingly a mental amputation). Often the transverse line crosses the wrist or elbow. In hysterical anesthesia of the whole arm, the loss often stops sharply at the shoulder joint, thus conforming to the Pt’s mental image of an arm but not to the actual innervation by dermatomes, peripheral nerves, or central pathways. See Figs. 14-7C and 14-7D. In psychogenic lower extremity anesthesia, the proximal border often falls at the waist or the gluteal fold posteriorly or the inguinal line anteriorly (Figs. 14-7E and 14-7F). As the anesthesia improves, the border moves distally along the limb, stopping at successive transverse levels until it disappears.

FIGURE 14-7. Contrast between psychogenic and organic sensory losses. (A) Psychogenic facial anesthesia usually includes the angle of the mandible and may stop at the hairline. (B) Organic facial anesthesia from a Vth nerve lesion spares the angle of the mandible (innervated by C2).The border follows the distribution of the entire Vth nerve or one of its three branches. See also Fig. 10-2. (C) Psychogenic loss of upper limb sensation usually stops transversely at the wrist, elbow, or shoulder. (D) Organic sensory loss when limited to a region of an upper extremity follows an anatomic distribution, either dermatomal (D1 shows the distribution of the C6 dermatome) or peripheral nerve (D2 shows the sensory distribution of the ulnar nerve). See also Figs. 2-10 and 2-11. (E) Psychogenic loss of lower extremity sensation usually stops at a joint, the gluteal fold dorsally, or the inguinal line ventrally or it may stop transversely at any lower level. (F) Organic sensory loss, when limited to a region of a lower extremity, follows an anatomic distribution, either dermatomal (F1 shows L5 dermatome) or peripheral nerve (F2 shows lateral femoral cutaneous nerve). See also Figs. 2-10 and 2-11.

3. In psychogenic paraplegia with a sensory level, the line circles the body horizontally; in organic paraplegia, the dermatomes slant downward in the abdomen; but this distinction is not absolute (Fig. 2-10 and Table 14-3). The abdominal reflexes and other reflexes below the level remain.

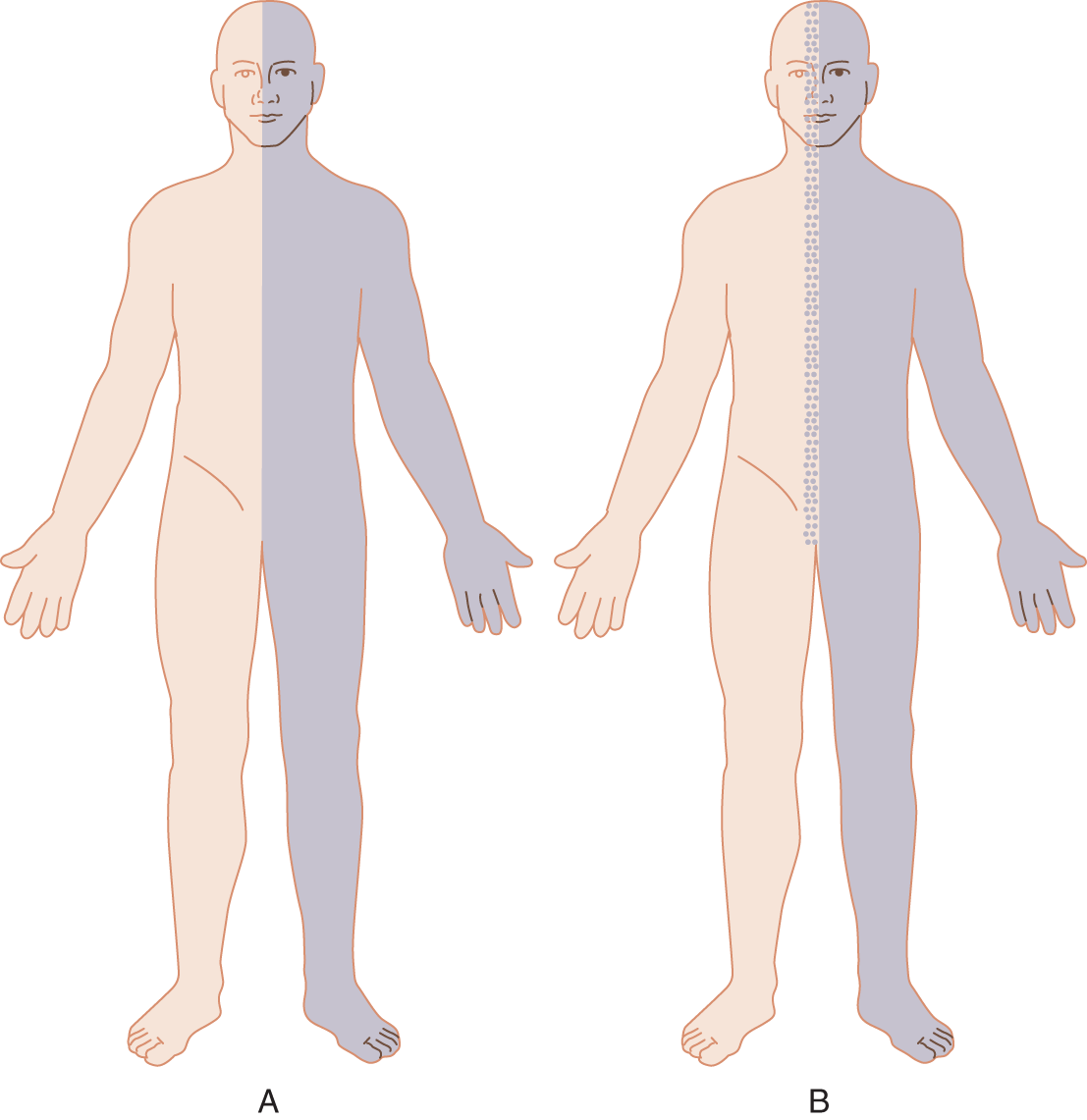

4. Some Pts show psychogenic hemianesthesia. The Pt not only loses all somatic sensation from one-half of the body but also may lose sight, hearing, taste, and smell on the affected side, an obvious anatomic impossibility. In psychogenic hemianesthesia, the sensory loss stops sharply at the midline and may run up the entire body and head as in the mental image of one-half of the body. The psychogenic Pt with hemisensory loss, for example, reports complete absence of vibratory sensation when a tuning fork, applied to the sternum or forehead, just reaches the midline. In fact, the vibration travels some distance through the bone, and its perception does not cut off sharply at the midline (Figs. 14-8A and 14-8B). Patients with organic hemisensory loss also may show a sharp cutoff. Thus, the finding is not pathognomonic of psychogenic disease (Stone et al, 2002).

FIGURE 14-8. Some differences in the borders of psychogenic and organic sensory losses in hemianesthesia. (A) In psychogenic hemianesthesia, the sensory loss usually stops abruptly at the midline for all modalities. (B) In organic hemianesthesia, the sensory loss may fade gradually at the midline, particularly for vibration. However, some patients with organic hemisensory loss also have an abrupt midline cutoff.

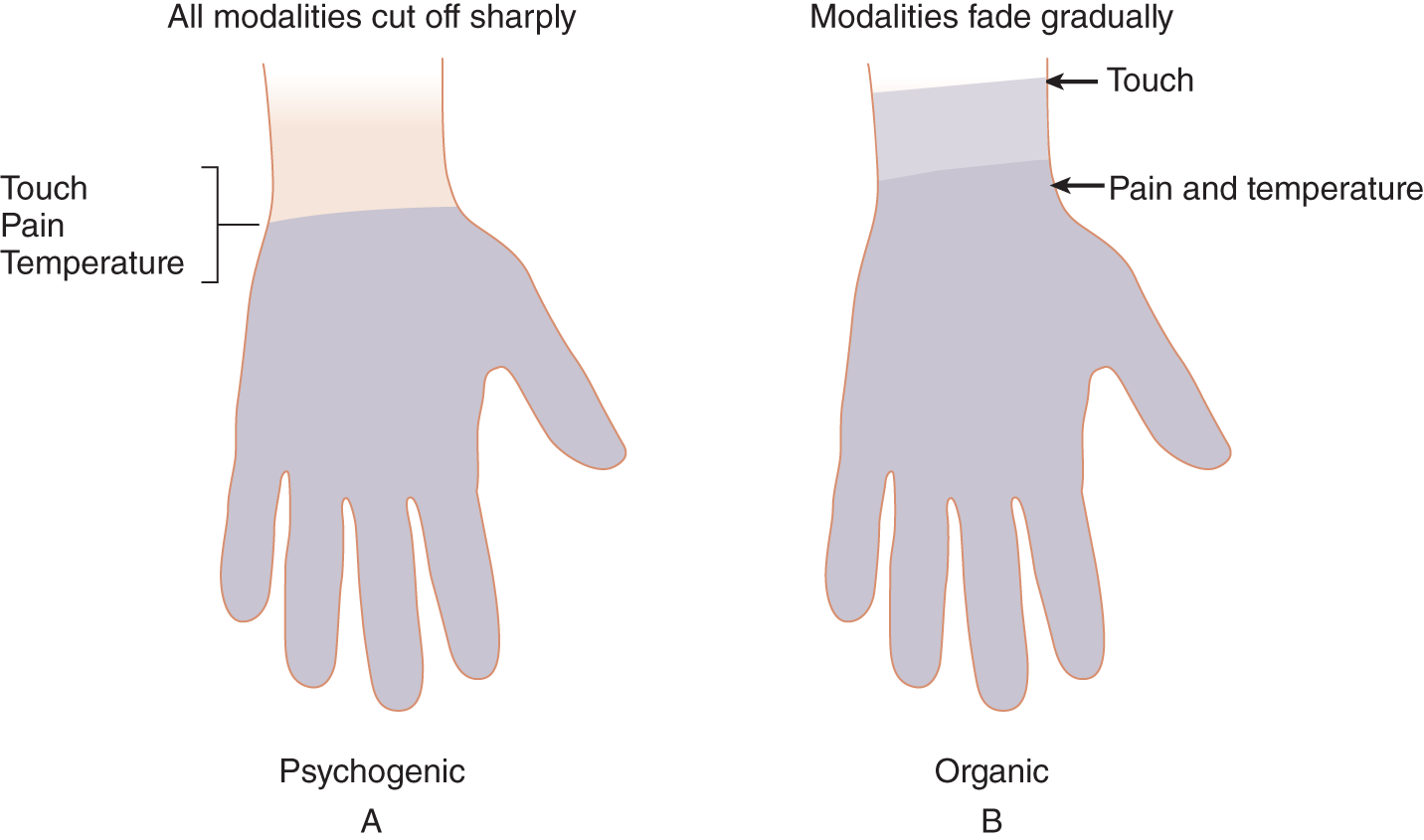

5. Figure 14-9 shows the usual differences in the border zone of organic and psychogenic sensory losses. The site of the border between the anesthetic and the normal zone in psychogenic sensory disorders, although usually sharp, may change from time to time.

FIGURE 14-9. Contrast between psychogenic and organic stocking-glove sensory loss. (A) In psychogenic stocking-glove sensory loss, the proximal border stops sharply at a joint line or skin crevice for all modalities. (B) In organic stocking-glove sensory loss, the proximal border usually fades gradually and differs for the various modalities.

C. Inadvertent proof that a sensory deficit is nonorganic

1. Normal motor function: If the Pt has psychogenic anesthesia for all modalities, not anesthesia plus paralysis, the Pt may use the part completely normally, which is impossible without proprioception. This fact plus the preservation of stretch reflexes and absence of hypotonia, atrophy, and dystaxia prove that the Pt cannot have organic anesthesia. Complete sensory loss must produce areflexia, hypotonia, and sensory dystaxia. (Review Table 10-3 for the features of sensory dystaxia.) During sleep the Pt will withdraw the putatively anesthetic extremity from pain.

2. Rhythmic responses: In testing touch or pain responses, the Ex may elicit a rhythm of answering that inadvertently discloses the integrity of the sensation in the putatively anesthetic or analgesic area. Ordinarily, to maintain the Pt’s attention, the Ex avoids such a rhythm in Pts with organic sensory deficits. Starting with areas of intact sensation, get the Pt to respond by saying yes when you apply the stimulus or no when you withhold it. Then, unexpectedly, out of rhythm, incorporate the anesthetic region in the testing. If the Pt says no each time just after the Ex unexpectedly touches the anesthetic zone, then at some level of consciousness, the Pt has perceived the stimulus.

3. Pattern of exactly opposite responses: In responding to position sense testing, the psychogenic Pt may give exactly opposite answers, saying, for example, down each time for up. The fact that the Pt gives exactly the opposite response each time means that position sense has to be intact. Even with total absence of position sense, the Pt should guess the right answer about half of the time.

4. Histrionic underreaction or exaggerated overreaction: Some Pts respond very slowly and deliberately to sensory tests. The Pt conveys the impression of trying very hard to feel the stimulus and report it correctly, that is, a pseudocooperation. Other Pts give a studied response of feeling it “just a little bit,” even after strong stimulation. In psychogenic analgesia, do not continue to apply increasingly strong pain stimuli to prove a point (or express frustration with a puzzling sensory examination). In contrast to these underreacting Pts, others overreact to sensory stimuli. The Ex learns to recognize the histrionic personality disorder overreaction or studied underreaction as inadvertent evidence of the nonorganic nature of the sensory deficit.

D. Caveats

In deciding whether a sensory loss is psychogenic or not, review the Steps in the Analysis of a Sensory Complaint (Chapter 10, Section XI). Recall also that organic pain may be referred to or radiate beyond the confines of an anatomic territory; conversely, the Pt with organic loss may impose a “body scheme” pattern. Some Pts with organic disease have true hyperesthesia, sometimes of excruciating type, as in complex regional pain type II (formerly known as causalgia), or trigger zones where the slightest stimulus of a particular site elicits unbearable pain, as in trigeminal neuralgia. Some Pts with thalamic or parietal lesions will show hemisensory losses that imitate a midline psychogenic pattern (Stone et al, 2002; Yarnell et al, 1978). See Fig. 14-8.

VI. PSYCHOGENIC NONEPILEPTIC SEIZURES

A. Definition

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures are episodes of altered motor, sensory, or mental function that resemble epileptic seizures but arise from psychological disturbances rather than from an abnormal hypersynchronous discharge of neurons (see the definition of epilepsy, page 298). The spells occur after some identifiable precipitating event. Most commonly, they occur in the presence of someone emotionally significant to the Pt, such as a parent or lover, or to avoid some unpleasant obligation. No single pathognomonic clinical feature separates true from pseudoepileptic seizures. Pseudoepileptic seizures may manifest as pure unresponsiveness without motor activity—in other words, a swoon or staring spell (Geyer et al, 2000; Leis et al, 1992)—or with motor actions.

B. Motor manifestations of psychogenic seizures

1. The pseudoepileptic motor activities include bizarre patterns of flailing, thrashing, or quivering. In contrast, a true generalized motor seizure presents a stereotyped sequence of an aura, a cry, a fall, the tonus, the clonus, incontinence, and postictal confusion and somnolence. The clonic movements die gradually in a characteristic way. Pseudoseizure Pts show more random, out-of-phase movements, with the extremities on the two sides often doing different things. Epileptic movements are more often rhythmic, in-phase bilaterally symmetrical tonic–clonic jerks; however, myoclonic seizures may present as random jerks (Keane et al, 1990).

2. In addition to extremity movements, the Pts with psychogenic seizures make side-to-side rocking head and body movements, rarely seen in true epilepsy. The posturing and jerking vary in intensity during the seizure (Meierkord et al, 1991; Rowan and Gates, 1993). Epileptic Pts may injure themselves by falling or biting their tongues. Pseudoseizure Pts may do the same, although much less frequently.

3. Patients with epileptic or psychogenic seizure show pelvic thrusting. Pelvic thrusting is strongly associated only with the thrashing type of pseudoseizure (Geyer et al, 2000).

C. Physiologic changes in psychogenic versus true seizures

1. Usually, in psychogenic seizures, the blood pressure, pulse rate, and pupillary size do not change materially, whereas in organic seizures they often change dramatically. Particularly with quiet staring spells of organic origin, the heart rate increases more than 30%, whereas in psychogenic seizures it does not (Opherk and Hirsch, 2002). True crying may occur in psychogenic seizures but excessively rarely in epileptic seizure (Lesser, 1996). However, laughter occurs in some epileptic seizures.

2. Serum prolactin, when measured at 10 to 20 minutes after a suspected ictal event, is elevated in approximately 90% of Pts who have just had a generalized tonic–clonic seizure and more than 50% of those who have had complex partial seizures.

3. Table 14-5 summarizes the differences between psychogenic and true seizures (Video 14-3).

TABLE 14-5 • Differentiation of Psychogenic and Epileptic Seizures

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures |

Epileptic seizures |

|

Cause |

Psychiatric predisposition always present; comorbid depression, sexual/physical abuse, anxiety, dissociative, and somatoform disorders; differentiate culture-bound syndromes |

Hypersynchronous neuronal discharge based on anatomic or metabolic disease; specific triggers uncommon, but touch, sight, sound, or mental activities, eg, calculation, may elicit a seizure |

Onset |

Onset often gradual, over minutes |

Onset with brief aura or instantaneously |

Location/circumstances |

Usually at home, in the presence of emotionally significant persons; do not occur while asleep |

Occur anywhere, anytime, night or day, during sleep or wakefulness, and may follow a diurnal pattern |

Induction of seizure |

Often inducible by suggestion, or placebo challenge, ie, IV saline, etc; patient may hyperventilate |

Not induced by suggestion; hyperventilation may induce a seizure, especially petit mal |

Vocalization/Emotion |

Vocalization may take the form of sobbing, yelling, or bizarre utterances |

Overt, single outcry may initiate a generalized seizure, but formed words or sobbing are rare; laughter may occur (gelastic epilepsy) |

Frequency |

May be several per day |

Except for petit mal and myoclonic seizures, other types usually less than one per day |

Motor activity |

Variability from moment to moment; arrhythmic or out-of-phase movements on the two sides; rolling, side-to-side head or trunk movements; pelvic thrusting common with thrashing type of seizures; may be simply staring or akinetic |

Usually follow a stereotyped pattern, depending on seizure type; staring spells often accompanied by twitch of face, blinking, or lip smacking; pure akinetic seizures are rare; pelvic thrusting uncommonly occurs |

Duration |

Often prolonged, >5 min, and may imitate status epilepticus; may come out of spell when addressed or stimulated |

Usually <3 min but may have status epilepticus; addressing or stimulating the patient does not terminate the seizure |

Incontinence |

Very rare |

Not uncommon |

Autonomic changes |

Do not occur |

Increased pulse rate, sometimes cardiac dysrhythmias, pupillodilation, sweating, cyanosis, excessive salivation, and slobbering |

Injury |

Unusual; tongue biting very rare |

Sometimes injury from falling or tongue biting |

Postictal state |

May remember events during episode; overt postictal confusion and somnolence unusual |

Amnestic for time of seizure, except for some focal seizures; often postictal confusion or somnolence |

Response to anticonvulsants |

No response despite therapeutic levels and multiple drugs |

Depending on seizure type and cause, patient usually responds to appropriate anticonvulsants |

Objective laboratory signs |

Video-EEG always normal; serum and CSF prolactin levels normal |

Video-EEG always abnormal (if electrodes are properly situated); increased serum prolactin in the appropriate setting at 10-20 min after a suspected event. |

ABBREVIATIONS: CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; EEG = electroencephalogram. |

||

Video 14-3. Description of Jacksonian seizures by a patient with MRI evidence of multiple enhancing lesions in both cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres consistent with brain metastases.

4. Two spells that, broadly considered, fall into the psychogenic category but are distinct clinically from the usual psychogenic seizure are breath-holding spells in infants and young children (page 513) and behavioral “tuning out” or staring spells. Normal babies, normal older persons, and especially learning disabled children frequently show spells consisting of an arrest of activity and a blank stare. You likely have noticed a tendency to sit and stare, to “blank out,” at times, when events seem overwhelming or insolvable. The learning disabled child may show these spells repeatedly in the classroom or at home. The hallmark is that the observer can always terminate the spell abruptly by a stimulus such as touching the person or calling that person’s name.

D. Caveats

1. Range of true epileptic seizures: Almost every conceivable neurologic symptom or sign has occurred in some Pt at some time as a true epileptic seizure. Epileptic seizures that arise in the frontal lobes may manifest by bicycle peddling motions, asymmetric tonic posturing (fencing position), often without loss of consciousness. Seizures arising in the supplementary motor area may also manifest as screaming, and even sexual activity (genital manipulation, pelvic thrusting). No matter how bizarre, the attack may be organic, including fugue states or confusional attacks (Ellis and Lee, 1978; Manford and Shorvon, 1992; Markand et al, 1978). In many instances, even the most experienced neurologist observing an attack cannot distinguish psychogenic attacks from organic ones. Pseudoepileptic seizures occur in adolescents and children, but rarely before age 8 to 10 years. Although pseudoseizures can occur at night, they do so only when the Pt is already awake, but true epileptic seizures may occur during sleep (Lesser, 1996).

2. Triggering of seizures: Hyperventilation can precipitate pseudoseizures and organic seizures, in particular petit mal. Rarely, thought processes such as calculation or playing games such as chess or cards may trigger true seizures (Goossens et al, 1990). The resolution requires combined video and EEG monitoring in a laboratory or ambulatory monitoring until the attacks can be recorded (Rowan and Gates, 1993).

a. Normal records during an attack virtually exclude epilepsy, but the EEG, which depends on surface electrical activity, rarely may appear normal, even during some epileptic attacks.

b. The most difficult problem is the combination of seizures and pseudoseizures that occurs in about 10% of epileptics (Benbadis et al, 2001). Patients with unrecognized pseudoepileptic seizures erroneously sometimes get intubated and receive intravenous medication for status epilepticus (Leis et al, 1992).

3. Rule out hypoglycemia: Whenever a Pt exhibits any undiagnosed attack that alters consciousness or results in a frank seizure, always measure the blood glucose level and, if indicated, other blood constituents.

4. Comorbid psychiatric disorders: Psychiatric illnesses are expected in pseudoseizures (Bowman, 2000).

VII. FACTITIOUS FEVERS

Some pts may produce false temperature readings by manipulating a thermometer. If a Pt has a puzzling fever or hypothermia of unknown origin, measure a fresh sample of urine with your own thermometer. The urine specimen will reflect the true body temperature, thus bypassing any manipulation the Pt manages with the thermometer (Murray et al, 1977). The Ex always has to consider doing a lumbar puncture and culturing the blood and urine in Pts with true fever of unknown origin.

VIII. THE AMNESIAS: PSYCHOGENIC (DISSOCIATIVE) AND ORGANIC

A. Psychogenic amnesia

1. Recognition of psychogenic amnesia rests on the psychiatric history and mental status examination rather than on bedside techniques such as those described for detecting other psychogenic signs and symptoms.

2. Psychogenic amnesias often start suddenly and generally are selective or restricted. Organic dementias tend to be global rather than selective and are accompanied by other evidence of organic brain impairment.

B. Some special types of organic amnesia

1. Organic amnesia follows an overt disease that obviously affected the brain, such as head trauma, limbic encephalitis, (infectious, autoimmune, paraneoplastic) and substance abuse, or occurs in the context of a neuronal degenerative disease.

2. Korsakoff syndrome (Korsakoff psychosis, amnestic-confabulatory syndrome) occurs most commonly in the context of alcohol use disorder and withdrawal delirium (delirium tremens).

3. The transient global amnesia (TGA) syndrome involves middle-aged to elderly Pts, the opposite age range from psychogenic amnesia. The Pt becomes temporarily disoriented for person, place, and date, but has no loss of consciousness, and fully recovers within a few hours, leaving a memory gap regarding events during the episode. During the attack, there is inability to learn both verbal and nonverbal material. TGA may follow various precipitating events, such as emotional stress, contact with cold water, physical exercise, sexual intercourse, and a variety of medications and/or medical procedures. The pathogenesis is unknown (Tong and Grossman, 2004; Video 14-4).

Video 14-4. A physician with transient global amnesia (TGA).

4. In the pure amnestic syndrome the Pt has retrograde and anterograde amnesia but retains a normal IQ. Damage to the medial quadrant of the temporal lobe causes it.

IX. PAIN, ESPECIALLY HEADACHE AND BACKACHE

A. Organic and psychogenic pain

1. Pain presents the most common and most difficult differential diagnosis of all, particularly separating psychogenic pain, major depressive disorder, and organic disease (Video 14-5).

Video 14-5. Chronic migrainous headaches in a patient with a colloid cyst of the III ventricle.

2. Organic pain may affect facial expression resulting in grimacing and eyelid narrowing. It may increase the pulse rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and pupillary size and result in defensive postures to relive pain.

3. Pure organic pain syndromes without explicit interictal signs, such as migraine or trigeminal neuralgia, present in patterns recognizable by the history. Pain of visceral origin, such as gallbladder pain that is intermittent, causes no interictal signs. However, definable or diagnosable organic causes of the two most common pain disorders, headache and low backache, usually offer one or more objective signs that certify the diagnosis. Because every practitioner will have Pts with these two pain syndromes, we review next the objective findings that point toward the organic diagnosis or that mandate further study by imaging, electromyography, or cerebrospinal fluid examination. With no objective findings on the NE, the likelihood of organic disease or of a specific diagnosis by laboratory further studies becomes very small (Lewis et al, 2002), and the psychiatric investigation becomes paramount.

B. Signs of organic headaches associated with definable lesions

Use the following tests or procedures to screen Pts for organic causes of headache:

1. Palpate/percuss for pain over various sites on the head and neck:

a. The entire scalp.

b. Sinuses and mastoid.

c. Exit sites of the ophthalmic and maxillary divisions of CrN V and the greater occipital nerve.

d. Temporal artery.

e. Masseters and neck muscles for tenderness or spasm.

2. Test for consistent alteration of pain by posture and position, particularly straining, bending forward, and the Valsalva maneuver.

3. Test for nuchal rigidity or some other limitation of neck movement.

4. Listen for bruits over neck vessels or head and palpate neck for masses.

5. Inspect the ear drum for otitis.

6. Check fundi for absence of venous pulsation, papilledema and hypertensive exudates.

C. Signs of organic low back pain or sciatica

Patients with low backache or sciatica syndrome will generally show at least one of the following signs (review Chapter 10, Section VII A-I):

1. Resistance to movement or jarring.

2. Characteristic antalgic gait.

3. Tilt of the spine.

4. Characteristic rising from a chair by bracing the arms to push up.

5. Flat lumbar curve.

6. Paravertebral muscle spasm.

7. If the Pt has a radicular syndrome look for:

a. Slight flexion of affected leg when standing and “soft” Achilles tendon.

b. Decreased or absent triceps sure muscle stretch reflex.

c. Atrophy of the calf on the side of radiating pain.

d. Weakness of the extensor hallucis longus and foot dorsiflexion.

e. Pain elicited by leg-raising tests.

X. SOME FINAL CAVEATS ON THE DIAGNOSIS OF PSYCHOGENIC DISORDERS

A. Consider an organic illness with a psychogenic (functional) overlay

Organic pain may not follow standard textbook distributions. Some Pts with undiagnosed illnesses, in shopping from physician to physician, elaborate on or exaggerate their organic symptoms in desperation as they try to convince physicians of the reality of their illness. Many previous physicians will have asked the same questions over and over in the review of systems, inadvertently suggesting symptoms for the Pt to worry about or to imagine. Such Pts may be neither malingering nor frankly hysterical, but legitimately worried about their health. The Ex always has to consider that an organic disease underlies the seemingly psychogenic complaints (Azher and Jankovic, 2005; DePaulo and Folstein, 1978; Schrag et al, 2004; Stone et al, 2002; Stone et al, 2005). See Table 14-6.

TABLE 14-6 • Organic Disorders with Bizarre or Subtle Neurologic Manifestations Often Mistaken for Psychogenic Illness

Early multiple sclerosis: fleeting sensory loss, retrobulbar neuritis, transient paraplegia |

Porphyria: abdominal pain, peripheral neuropathy, seizures, and mental changes |

Endocrinopathies: fatigue, weakness, nervousness, and tremors |

Involuntary movement syndromes with bizarre gait disturbances, in particular dystonia with tortipelvis and camptocormia, early degenerative diseases such as spinocerebellar degenerations, certain channelopathies, and paroxysmal kinesigenic and nonkinesigenic dyskinesias |

Seizures with bizarre auras affecting vision, somatic sensation, and visceral auras with crawling sensations, abdominal auras of something like fluid running through the chest or abdomen, odd smells or odors, sexual feelings such as orgasm, forced thoughts, and forced laughter |

Myasthenia gravis with transient cranial nerve dysfunction, fatigability, and weakness |

Neuropathies, particularly carpal tunnel syndrome, causalgia (reflex sympathetic dystrophy), and autonomic neuropathies |

Early Tourette syndrome with multiple tics, throaty sounds, and urgent, obsessive personality patterns |

Midline neoplasms or butterfly gliomas with personality changes preceding objective neurologic signs |

Collagen-vascular disease with neuropathy, fleeting central nervous system symptoms, fatigue, and fever |

Syringomyelia with dissociated pain and temperature loss |

Foramen magnum or spinal level meningioma with spastic-ataxic gait |

B. Remain patient

The diagnosis rests on the totality of the clinical evidence from the history and NE, not on any pathognomonic single finding or parlor trick that fools the Pt. During the history and examination, avoid the impression of trying to unmask or expose the Pt. Avoid confrontation and tricks, such as hypnosis or electric shocks, to “speed up” recovery. Ridding the Pt of psychogenic symptoms does not rid the Pt of the psychogenic illness. The symptom is not the problem—something else is.

C. Maintain professionalism to avoid diagnostic errors

Those puzzling and troublesome Pts whose illnesses consist of organic, psychogenic, and factitious factors often provoke anger. Neophyte physicians may refer to these Pts by inexcusable names such as “crocks,” “gomers,” or “gorks.” Remember yet another aphorism: If you deprecate the Pt, you have failed to understand the Pt’s problem. The psychogenic symptom is a way of communicating something that the Pt cannot face or verbalize, a distinct cry for help. Whatever the diagnostic label, the Pt is distressed. Such Pts need a physician who remains receptive and potentially helpful, rather than dismissing the person as a cheat, a liar, or a fraud. Regard every event in the consulting room, whether an extensor plantar response or a factitious fever, neutrally as a clinical phenomenon. Reacting with hostility or overt disbelief will degrade the quality of your examination and greatly increase the possibility of an error in diagnosis or management. Avoid adversarial polarization with the Pt trying to prove the reality of an illness and you trying to disprove it. Retain the grace and humility to recognize the fallibility of your own judgments. Never dismiss the Pt with a belittling: “It is all in your head.” At the end of the encounter, you can hint that the findings suggest a disorder that may end in recovery, but let the Pt retain the refuge of “patienthood.”

D. Avoid the patient’s trap

The intimacy of the medical examination provides a prime opportunity for some Pts to indulge in pathologic manipulation. Such Pts may act seductively, try to exploit their illness for pity or favors, or consciously or subconsciously try to provoke hostility. If duped by these maneuvers, you lose any possibility of helping the Pt. For this and many other reasons, the medical model forbids the physician to succumb emotionally to the Pt, whether with love, pity, or hostility.

E. Beware of factitious disorder (formerly known as Munchausen syndrome) and factitious disorder imposed on another (formerly known as Munchausen syndrome by proxy)

1. A practiced Pt with factitious disorder or Munchausen syndrome can fool many of the tests described in this text, including falsifying a Babinski sign.

2. In factitious disorder imposed on another, the parent or spouse acts as an enabler or frankly creates the illness of another family member. In children be wary of illness willfully perpetuated by a parent. Here are two of the worst cases in my experience. The first was a registered nurse whose son repeatedly presented at the emergency room with hypoglycemic seizures. Immunoassay of the child’s blood showed porcine insulin. Sometime later the mother herself presented to an emergency room with hypoglycemia induced by self-administered insulin. In the second instance, a hospitalized child repeatedly had mysterious fevers caused by coliform bacteria septicemia. A video camera hidden in the hospital room showed the mother injecting feces into the child’s intravenous tube. In view of the male propensity to batter children, we have to conclude that not all parents, mothers or fathers, love their children.

F. Following-up

Schedule follow-up appointments to ensure that your proffered diagnosis was the correct diagnosis, as the rate of misdiagnosis of conversion symptoms, although declining, remains at about 4% (Stone et al, 2005).

G. The patient may have some disease you had not thought of or even heard of

Never diagnose a psychogenic illness by exclusion because you cannot find another diagnosis. Call in a consultant who just may recognize the porphyria, smoldering collagen disease, occult carcinoma, parasitic infestation, chronic liver abscess, multiple sclerosis, or masked depression that you did not even consider. Remember this:

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

BIBLIOGRAPHY · Clinical and Laboratory Tests to Distinguish Conversion Disorder and Malingering from Organic Disease

Allanson J, Bass C, Wade DT. Characteristics of patients with severe disability and medically explained neurological symptoms: a pilot study. J Neurol Neursurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:307–309.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed (DSM-5). Arlington, TX: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Aminoff MJ, Dedo HH, Izdebski K. Clinical aspects of spasmodic dysphonia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1978;41:361–365.

Azher SN, Jankovic J. Camptocormia: Pathogenesis, classification, and response to therapy. Neurology. 2005;65:355–369.

Baker JHE, Silver JR. Hysterical paraplegia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50:375–382.

Benbadis SR, Agrawal V, Tatum IV WO. How many patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures also have epilepsy? Neurology. 2001;57:915–917.

Bowman ES. The differential diagnosis of epilepsy, pseudoseizures, dissociative identity disorder, and dissociative disorder not otherwise specified. Bull Menninger Clin. 2000;64:164–180.

Bumgartner J, Epstein CM. Voluntary alteration of visual evoked potentials. Ann Neurol 1982;12: 475–478.

Butler C, Zeman AZG. Neurological syndromes which can be mistaken for psychiatric conditions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:131–138.

DePaulo JR, Folstein MF. Psychiatric disturbances in neurological patients: detection, recognition, and hospital course. Ann Neurol. 1978;4:225–228.

Edwards MJ, Stone J, Lang AE. From psychogenic movement disorder to functional movement disorder: it’s time to change the name. Movement Disorders. 2014; 29(7):849–852.

Ellis JM, Lee SI. Acute prolonged confusion in later life as an ictal state. Epilepsia. 1978;19:119–128.

Geyer J, Payne TA, Drury I. The value of pelvic thrusting in the diagnosis of seizures and pseudoseizures. Neurology. 2000;54:227–229.

Goossens LAZ, Andermann F, Andermann E, et al. Reflex seizures induced by calculation, card or board games, and spatial tasks: a review of 25 patients and delineation of the epileptic syndrome. Neurology. 1990;40:1171–1176.

Griffin JF, Wray SH, Anderson DP. Misdiagnosis of spasm of the near reflex. Neurology. 1976:26:1018–1020.

Iliceto G, Thompson PD, Day BL, et al. Diaphragmatic flutter, the moving umbilicus syndrome, and “belly dancer’s” dyskinesia. Movement Disorders. 2004;5(1):15–22.

Keane AM, Morris HH, Luders H, et al. Supplementary motor seizures mimicking pseudoseizures: some clinical differences. Neurology. 1990;40:1404–1407.

Keane JR. Hysterical gait disorders. Neurology. 1989;39:586–589.

Keane JR. Neuro-ophthalmic signs and symptoms of hysteria. Neurology. 1982;32:757–762.

Keane JR. Wrong-way deviation of the tongue with hysterical hemiparesis. Neurology. 1986;36:1406–1407.

Koller W, Lang A, Vetere-Overfield B, et al. Psychogenic tremors. Neurology. 1989;39:1094–1099.

LaFrance WC. Somatoform disorders. Sem Neurol. 2009;29:234–246.

Leis AA, Ross MA, Summers AK. Psychogenic seizures: ictal characteristics and diagnostic pitfalls. Neurology. 1992;42:95–99.

Lenoir T, Guedj N, Benoist M. Camptocormia: the bent spine syndrome, an update. Eur Spine. 2010;19(8):1229–1237.

Lesser RP. Psychogenic seizures. Neurology. 1996;46:1499–1506.

Lewis DW, Ashwal S, Dahl G, et al. Practice parameter: evaluation of children and adolescents with recurrent headaches: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2002;59:490–498.

Manford M, Shorvon SD. Prolonged sensory or visceral symptoms: an under-diagnosed form of non-convulsive focal (simple partial) status epilepticus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55:714–716.

Markand ON, Wheeler GL, Pollack SL. Complex partial status epilepticus. Neurology. 1978;28:189–196.

Meierkord H, Will B, Fish D, et al. The clinical features and prognosis of pseudoseizures diagnosed using video-EEG telemetry. Neurology. 1991;41:1643–1646.

Meyers JE, Volbrecht ME. A validation of multiple malingering detection methods in a large clinical sample. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2003;18:261–276.

Monrad-Krohn GH. On the function of the latissimus dorsi muscle as a sign of functional dissociation in simulated and “functional” paralysis of the arm. Acta Med Scand. 1922;56:9–11.

Murray HW, Tuazon CU, Guerrero IC, et al. Urinary temperature: a clue to early diagnosis of factitious fever. N Engl J Med. 1977;296:23.

Nicholson TRJ, Stone J, Kanaan RAA. Conversion disorder. A problematic diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(11):1267–1273.

Opherk C, Hirsch LJ. Ictal heart rate differentiates epileptic from non-epileptic seizures. Neurology. 2002;58:636–638.

Pilai JJ, Markind S, Streletz LJ, et al. Motor evoked potentials in psychogenic paralysis. Neurology. 1991;42:935–936.

Ravich WJ, Wilson RS, Jones B, Donner MW. Psychogenic dysphagia and globus: reevaluation of 23 patients. Dysphagia. 1990;4(4):244.

Reuber M, Mitchell AJ, Howlett SJ, et al. Functional symptoms in neurology: questions and answers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:307–314.

Reza Samie M, Selhorst JBG, Koller WC. Posttraumatic midbrain tremors. Neurology. 1990;40:62–66.

Rowan AJ, Gates JR. Non-Epileptic Seizures. Stoneham, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1993.

Schrag A, Brown RJ, Trimble MR. Reliability of self-reported diagnoses in patients with neurologically unexplained symptoms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:608–611.

Simon DK, Nishino S, Scammell TE. Mistaking diagnosis of psychogenic gait disorders in a man with status cataplecticus (“Limp Man Syndrome”). Mov Disorders. 2004;19(7):838–840.

Stone J, Smyth R, Carson A, et al. Systematic review of misdiagnosis of conversion symptoms and “hysteria”. BMJ. 2005;331(7523):989. Epub 2005 Oct 13.

Stone J, Carson A, Sharpe M. Functional symptoms and signs in neurology: assessment and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(Suppl 1):2–12.

Stone J, Sharpe M, Carson A, et al. Are functional motor and sensory rarely more frequent on the left? A systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:548–558.

Stone J, Smyth R, Carson A, et al. La belle indifference in conversion symptoms and hysteria. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:204–209.

Stone J, Zeman A, Sharpe M. Functional weakness and sensory disturbance. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:241–245.

Tan CT, Murray NMF, Sawyers D, et al. Deliberate alteration of the visual evoked potential. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1984;47:518–523.

Tong DC, Grossman M. What causes transient global amnesia? New insights from DWI. Neurology. 2004;62(12):2154–2155.

Troost BT, Troost EG. Functional paralysis of horizontal gaze. Neurology. 1979;29:82–85.

van der Ploeg RJO, Oosterhuis HJGH. The “make/break test” as a diagnostic tool in functional weakness. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54:248–251.

Walker FO, Alessi AG, Digre KB, et al. Psychogenic respiratory distress. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:196–200.

Weintraub MI. Malingering and conversion reactions. Neurol Clin. 1995;13:229–450.

Woolsey RM. Hysteria: 1875–1975. Dis Nerv Syst. 1976;37:379–386.

Yarnell P, Melamed E, Silverberg R. Global hemianesthesia: a parietal perceptual distortion suggesting non-organic illness. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1978;41:843–846.

Learning Objectives for Chapter 14

Learning Objectives for Chapter 14