15 |

A Synopsis of the Neurologic Investigation and a Formulary of Neurodiagnosis |

In clinical situations there are three principal factors that can legitimately influence the decision making process. These are:

1. The scientific evidence

2. The practitioner’s clinical experience

3. The practical situation, including the patient’s wishes, other people’s concerns, the patient’s lifestyle and culture, the social environment, and realistic observations to the delivery of technically ideal interventions

These can be thought of as a triangle of forces.

There are some problems with each of these factors as a primary guide to treatment. Consequently, they should remain metaphorically in a state of balance in the clinician’s mind, so that he is able to establish treatment plans that are evidence based (but not mechanistic), patient centered and contextualized (but not irrational), and informed by experience (rather than by a faith in idiosyncratic ideas). Treatment frequently goes wrong because one or more of these factors have been neglected.

I. THE ROUTINE SCREENING NEUROLOGIC EXAMINATION WHEN THE PATIENT HAS NO SYMPTOMS SUGGESTING NEUROLOGIC DISEASE

A. What is the minimum allowable neurologic examination?

Every new patient (Pt) and every routine physical checkup requires the examiner (Ex) to complete a minimum screening neurologic examination (NE) of all body systems. To this requirement students often respond fretfully: “But it takes too long to do the NE on everyone!” In fact, with sufficient practice, you can learn to do a basic screening NE in about 6 minutes in the mentally normal, cooperative Pt who has no neurologic symptoms. This statement presupposes a thorough history. The better the history, the briefer the examination required. The Ex need not and should not do every test on every Pt but should expand or trim the examination to fit the Pt’s history. If a Pt presents only with a sore throat and has no neurologic symptoms whatsoever, the Ex squanders time in testing smell and taste, doing caloric irrigation, a detailed aphasia examination, and in tugging against every muscle. The expanded examination to explore neurologic symptoms often requires the time for these tasks. For a brand new Pt, we schedule a full hour to complete the history and physical examination, dictate notes, and arrange for laboratory tests or referrals. Recall that the history and clinical examination still constitute the most efficient methods known to establish the relationship between physician and the Pt that is optimum for detecting disease, and for planning a healthy lifestyle.

B. Format for the mandatory 6-minute neurologic examination for every patient

1. Appraisal during the history: During the history, the Ex appraises the Pt’s mental status, notes the facial features, the eyes and ears, ocular movements, speech and swallowing and observes the posture, gait, and movement patterns.

2. Examination of the head: Inspect the head shape and palpate the head. Record the occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) of every infant.

3. Visual system: Test visual acuity (central fields), peripheral fields, do ophthalmoscopy, and test the pupillary reflexes.

4. Do the 45-second motor examination of cranial nerves III, IV, V, VI, VII, IX, X, XI, and XII (Table 6-8).

5. Hearing: Test by conversational voice and by finger rustling.

6. Somatic motor examination

a. Undress the Pt, note the somatotype, and inspect for muscle atrophy, fasciculations, tremors, involuntary movements, and neurocutaneous stigmata.

b. Test gait by free walking; toe, heel, and tandem walking, and deep knee bend.

c. Test strength of abduction of arms, wrist dorsiflexion, grip, hip flexion, and foot dorsiflexion.

d. Test cerebellar function by finger-to-nose and heel-to-knee tests, in addition to the gait.

e. Elicit muscle stretch reflexes of biceps, quadriceps femoris, and triceps surae.

f. Elicit plantar reflexes.

7. Somatosensory examination

a. Test superficial sensation by light touch and temperature discrimination on the face, hands, and feet (Fig. 10-4).

b. Test deep sensation by the directional scratch test (Chapter 10, Section VIII), position sense in fingers and toes, and vibration sense at the ankles.

c. Test for astereognosis with coins or paper clips.

C. Recording the routine neurologic examination

When we read someone else’s NE, we want to find out the mental status and whether the Pt can see, hear, talk, swallow, breathe, stand, walk, and feel normally. Surprisingly, many write-ups fail to include that information. Hurriedly scribbling that the “neuro exam is physiological” or “within normal limits (WNL)” just will not do. When a Pt has neurologic findings, no forms or checkoff lists record the NE as well as a series of statements, best written or typed. If the Pt has no neurologic findings, you still may prefer to write out the screening NE, but a checkoff sheet can save time, and you may expand it as needed to record positive findings (Table 15-1).

TABLE 15-1 • Recording the 6-Minute Screening Neurologic Examination for Patients without Neurologic Symptoms

II. THE CONCEPT OF “SOFT” NEUROLOGIC SIGNS

A. Definition

Many of the neurologic signs described thus far result from a lesion at a known site or that affect a known pathway. The presence of the sign essentially mandates the presence of a lesion as an explanation. These “hard” signs contrast with “soft” signs that bear a statistical correlation with brain dysfunction, but do not arise from specific, known central nervous system (CNS) lesions or even mandate a brain lesion. Such findings are referred to as a neurological soft sign or minor neurological dysfunction and are often symmetric, but manifest as an abnormality of motor control, sensorimotor integration, or cerebral laterality. They can assume the appearance of impaired fine motor movements, choreoathetoid movements, disorders of conjugate gaze or cerebellar signs of the extremities.

While their etiology remains unclear, it has been suggested that they reflect lack of neurodevelopment, impaired integration of sensory and motor systems, or deficits within subcortical structures (eg, basal ganglia and limbic system), but the general implication has been that they are often benign and lessen in prominence as the individual matures (Dazzan & Murray, 2002; Martins et al, 2008). Interpretation of their significance is aided by normative data on soft signs (Tupper, 1986; Largo et al, 2001a, 2001b; Gasser et al, 2010) and a manual for criteria, cutoffs, etc, provides further guidance for their interpretation (Hadders-Algra et al, 2010). Table 15-2 lists several examples of soft signs.

TABLE 15-2 • Examples of “Soft” Signs of Brain Impairment

Dysmorphic soft signs |

Neurologic soft signs |

OFC <2 SD or >2 SD from the mean |

Nystagmus |

Skull asymmetry |

Heterotropia |

Hyper- and hypotelorism |

Asymmetric facial movements |

Unusual hair whorls |

Dysarthria |

Unusually fine or coarse hair |

Dysprosody |

Synophrys (fusion of eyebrows) |

Inability to wink eyes separately |

Malformed ears |

Saccadic smooth pursuit |

Epicanthal folds |

Measures of balance coordination, and steadiness |

Cleft lip |

Whole body clumsiness |

Iris coloboma |

Motor impersistence (inability to maintain a posture) |

Iris heterochromia |

Inability to hop on one foot |

Micro- or macrostomia Broad or absent philtrum |

Thumb–finger opposition: (Failure of successively touching of the thumb to the four fingers) |

High arched palate |

Persistence of letter reversals |

Micrognathia |

“Overflow” movements |

Pectus excavatum Single palmar crease |

Excessive “piano-playing” movements of the outstretched fingers |

Short, incurved little finger (clinodactyly) |

Choreiform twitches of the fingers when performing designated motor actions |

Polydactyly |

Irregular alternating movements |

Syndactyly |

Hypo- or hypertonia |

Abnormal toe lengths |

Poor comprehension of instructions for performing fine or gross motor tasks Right–left confusion |

Dorsal midline defects: nevus, hair patch, dimple |

|

ABBREVIATIONS: OFC = occipitofrontal circumference; SD = standard deviation. |

|

Developmental coordination disorder (DCD) applies to children who have a long-standing, nonprogressive disorder, manifested as a deficit in motor skill performance. Neurological soft signs are insufficient to explain their difficulties. DCDs are not attributable to any known medical or psychosocial condition, but significantly interfere with the individual’s activities of daily living or academic achievement (Peters et al, 2011; Blank et al, 2012).

B. Implications of soft signs

Many soft signs are simply variations of normal, but there is an overlap between those with “immaturity” of the central nervous system and age-matched population controls. An example is the single palmar crease that regularly occurs in certain malformation syndromes with intellectual developmental disorders, such as Down syndrome, but also occurs in some neurologically normal persons. Other signs by themselves are hard signs of a neurologic lesion but not of brain impairment per se. A lateral rectus palsy necessitates a lesion but usually in the peripheral nervous system (PNS), not in the CNS. However, if we select a lateral rectus palsy as the independent variable, it will occur more frequently in brain-impaired persons than in normal persons. Hence, it is a hard sign of a neurologic lesion, but a soft sign of a brain lesion. Dysmorphic soft signs suggest a prenatal teratogen or genetic cause for the brain impairment.

However, the importance of soft signs is their increased incidence in populations that include children with intellectual developmental disorders, learning disabilities, behavioral disorders, and schizophrenia (Tupper, 1986; Dazzan and Murray, 2002; van Hoorn, 2010; Ferrin and Vance, 2012; Mayoral et al, 2012; Patankar et al, 2012; Hembram et al, 2014; Gong et al, 2015).

BIBLIOGRAPHY · The Concept of Soft Neurologic Signs

Blank R, Smits-Engelsman B, Polatajko H, Wilson P. European Academy for Childhood Disability (EACD): recommendations on the definition, diagnosis and intervention of developmental coordination disorder (long version). Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54;54–93.

Dazzan P, Murray RM. Neurological soft signs in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:350–357.

Ferrin M, Vance A. Examination of neurological subtle signs in ADHD as a clinical tool for the diagnosis and their relationship to spatial working memory. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53: 390–400.

Gasser T, Rousson V, Caflisch J, Jenni OG. Development of motor speed and associated movements from 5 to 18 years. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:256–263.

Gong J, Xie J, Chen G, et al. Neurological soft signs in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: their relationship to executive function and parental neurological soft signs. Psychiatry Res. 2015;228:77–82.

Hadders-Algra M, Heineman KR, Bos AF, Middelburg KJ. The assessment of minor neurological dysfunction in infancy using the Touwen Infant Neurological Examination: strengths and limitations. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:87–92.

Hembram M, Simlai J, Chaudhury S, Biswas P. First rank symptoms and neurological soft signs in Schizophrenia. Psychiatry Journal. 2014; 2014.(931014):11. doi:10.1155/2014/931014.

Largo RH, Caflisch JA, Hug F, et al. Neuromotor development from 5 to 18 years. Part 1: timed performance. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001a;43:436–443.

Largo RH, Caflisch JA, Hug F, et al. Neuromotor development from 5 to 18 years. Part 2: associated movements. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001b;43:444–453.

Martins I, Lauterbach M, Slade P, et al. A longitudinal study of neurological soft signs from late childhood into early adulthood. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50:602–607.

Mayoral M, Bombín I, Castro-Fornieles J, et al. Longitudinal study of neurological soft signs in first-episode early-onset psychosis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53:323–331.

Patankar VC, Sangle JP, Shah HR, et al. Neurological soft signs in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Indian J Psychiatry. 2012;54:159–165.

Peters LH, Maathuis CG, Hadders-Algra M. Limited motor performance and minor neurological dysfunction at school age. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:271–278.

Tupper DE, ed. Soft Neurological Signs. Orlando, FL: Grune & Stratton; 1986.

van Hoorn J, Maathuis CG, Peters LH, Hadders-Algra M. Handwriting, visuomotor integration, and neurological condition at school age. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:941–947.

III. THE CONCEPT OF “FALSE” LOCALIZING SIGNS

A. Definition

A false localizing sign is a specific sign that is observed or elicited, but localization to the appropriate corresponding area by the Ex does not identify the expected lesion which is elsewhere in the CNS. The sign is not false and neither is its typical relationship to a discrete anatomical localization, but in these cases it is distant from the actual site of the primary lesion (Larner, 2003). When the interpretation of the finding does not identify the expected lesion, then further evaluation is needed as clinical teaching is not foolproof (Hellmann et al, 2013; Tsunoda et al, 2014).

B. Causes

1. False localizing signs are caused mainly by shifts of the brain that compress or displace structures distant from the lesion or that compress blood vessels that supply distant sites (Matsuura and Kondo, 1996; McKenna et al, 2009; Kearsey et al, 2010: Safavi-Abbasi et al, 2014; Wijdicks and Giannini, 2014).

2. Obstructive hydrocephalus may cause compression of cranial nerve VI along the base of the skull, even with the primary lesion at the foramen magnum. Similarly, aqueductal enlargement in hydrocephalus may cause features of the pretectal (Sylvian aqueduct) syndrome, such as impaired upward gaze.

3. False localizing oculomotor disturbances may be associated with ruptured intracranial aneurysms (Suzuki and Iwabuchi, 1974; Srinivasan et al, 2015).

4. Shifts of the brain from large unilateral lesions may compress the anterior cerebral artery under the falx or the posterior cerebral artery against the edge of the tentorium. See the section on brain herniations in Chapter 12.

BIBLIOGRAPHY · The Concept of “False” Localizing Signs

Hellmann MA, Djaldetti R, Luckman J, Dabby R. Thoracic sensory level as a false localizing sign in cervical spinal cord and brain lesions. Clin Neurol Neurosur. 2013;115:54–56.

Kearsey C, Fernando P, Benamer HTS, Buch H. Seventh nerve palsy as a false localizing sign in benign intracranial hypertension. J R Soc Med. 2010;103:412–414.

Larner AJ. False localizing signs. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:416–418.

Matsuura N, Kondo A. Trigeminal neuralgia and hemifacial spasm as false localizing signs in patients with a contralateral mass of the posterior cranial fossa. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:1067–1071.

McKenna C, Fellus J, Barrett AM. False localizing signs in traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury. 2009;23(7–8):597–601.

Safavi-Abbasi S, Maurer AJ, Archer JB, et al. From the notch to a glioma grading system: the neurological contributions of James Watson Kernohan. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;36: E4

Srinivasan A, Dhandapani S, Kumar A. Pupil sparing oculomotor nerve paresis after anterior communicating artery aneurysm rupture: false localizing sign or acute microvascular ischemia? Surg Neurol Int. 2015;6:46.

Suzuki J, Iwabuchi T. Ocular motor disturbances occurring as false localizing signs in ruptured intracranial aneurysms. Acta Neurochirurgica. 1974;30(1–2):119–128.

Tsunoda D, Iizuka H, Iizuka Y, et al. Wrist drop and muscle weakness of the fingers induced by an upper cervical spine anomaly. Eur Spine J. 2014;23(Suppl 2):S218–S221.

Wijdicks EFM, Giannini C. Wrong side dilated pupil. Neurology 2014:83:187

IV. CLOSING THE NEUROLOGIC EXAMINATION WHEN THE PATIENT HAS SYMPTOMS OR SIGNS SUGGESTING NEUROLOGIC DISEASES

A. Hypothesis testing and reaching a provisional diagnosis

When the history suggests neurologic disease, the NE must include the critical tests for the integrity of neural structures that the lesion or disease could affect. The goal is to achieve the best provisional diagnosis. To reach a provisional diagnosis, the Ex poses and tests numerous diagnostic hypotheses during the history, physical examination, and, later, the laboratory work-up. The thinking process is one of posing if’s: “If the Pt has such and such a disease or sign, then I should also find so and so. Very well, I will look for that next.”

B. The concept of closure (cloture)

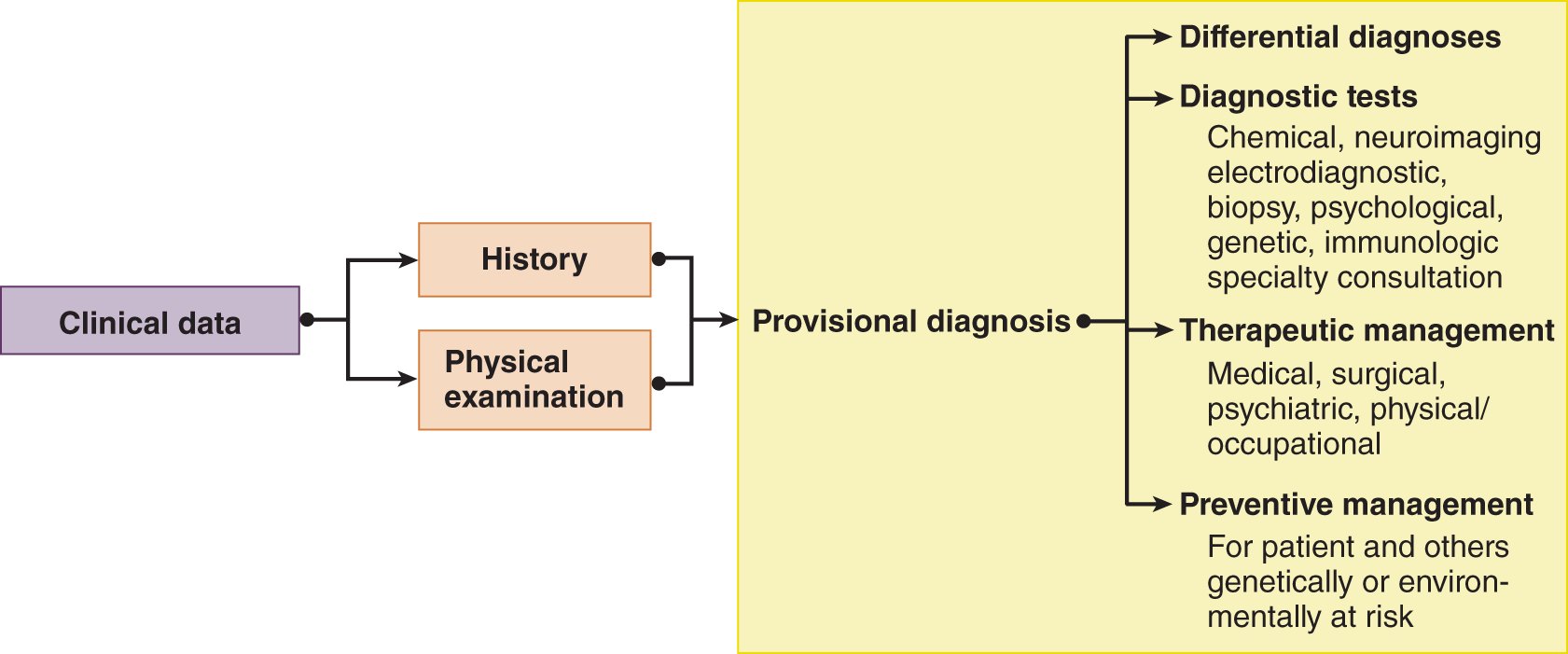

After the history, after the examination, and after the hypothesizing, the next event in the medical process is the cloture. Cloture is a technical term meaning, now that the arguments have been heard and the data presented, the time has come to pose the critical question(s) for decision and action. The provisional diagnosis and the differential diagnosis derived from it are the outcomes of the cloture, and the medical management is the action (Fig. 15-1).

FIGURE 15-1. Summary of the operational steps for cloture. The clinical data lead to a provisional diagnosis. The provisional diagnosis is the critical link in the process because it determines the differential diagnoses, leads to final diagnosis, and justifies all of the remaining steps in management.

C. The diagnostic catechism

The cloture requires six questions, three primary and the three derivative, that form the diagnostic catechism (Table 15-3).

TABLE 15-3 • The Diagnostic Catechism for Cloture

1. Is there a lesion or disease? |

2. If so, where is the lesion or the disease? |

3. What is the lesion or the disease (the provisional diagnosis)? |

4. What is the optimum diagnostic management? What clinical or laboratory tests, if any, will confirm or reject the provisional diagnosis? |

5. What is the optimum therapeutic management? |

6. What is the optimum preventative management? |

D. Is there a lesion (Table 15-3, question 1)?

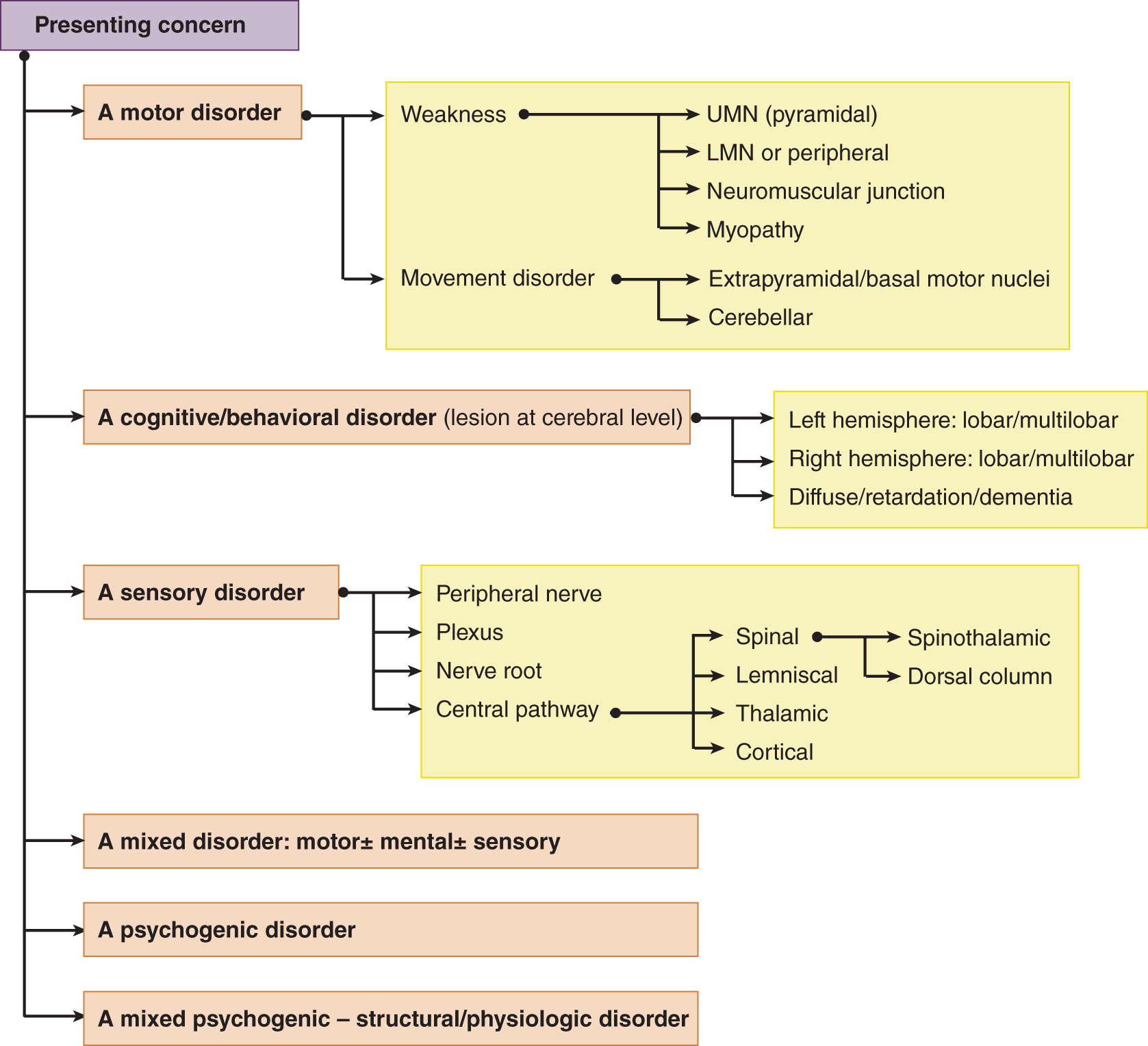

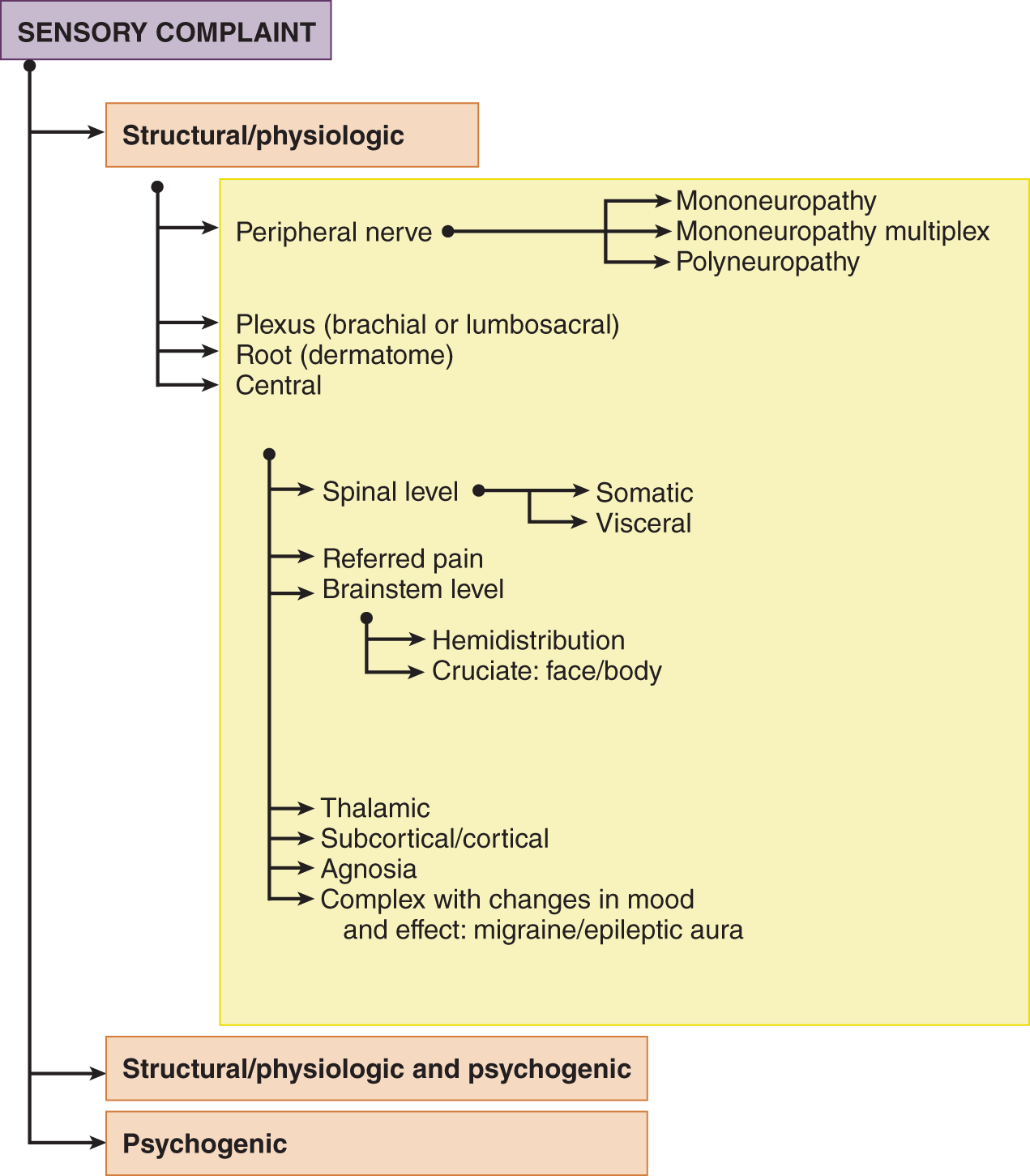

The first dichotomy is whether the disorder is structural/physiologic or psychogenic. That is the meaning of the first question, “Is there a lesion or a disease?” The Ex initially tries to discover neurologic signs that identify an anatomic lesion. Then the Ex considers organic disorders with biochemical lesions, such as some types of epilepsy or migraine, that exhibit no physical signs in the interictal examination. Next, the Ex considers emotional disorders with no lesion. The Ex must try to separate psychogenic from structural/physiologic disorders because the provisional diagnosis thus achieved determines the extent and type of clinical and laboratory tests required to establish the final diagnosis. To answer yes to the question, “Is there a lesion?” the Ex hopes to find at least one sign. One firm sign may mean more than a multitude of symptoms. In answering the question, think through Fig. 15-2 to start generating the possibilities in your mind.

FIGURE 15-2. Preliminary possibilities when the patient’s complaint and the neurologic examination suggest neurologic disease. Are the symptoms and signs, motor, mental, or sensory? Are they organic or psychogenic, or some combination? LMN = lower motoneuron; UMN = upper motoneuron.

E. Where is the lesion or the disease (Table 15-3, question 2)?

If the clinical evidence suggests a lesion or disease, ask these questions:

1. Is the lesion or disease in the structure or the biochemistry of the Pt?

2. Is it at the level of gene, chromosome, or cell? Is it at the level of blending of cells into tissues or of tissues into organs, or of organs into systems, or of systems into the general somatotype of the Pt? Do the findings constitute a diagnostic neuroanatomic, morphologic, biochemical, or genetic syndrome?

3. Can a decision be made as to the organ or organs, system or systems involved by the lesion? If it affects the nervous system, is the lesion:

a. In the PNS or CNS?

b. If the lesion involves the CNS, is it intra-axial or extra-axial?

c. If intra-axial, is it focal: in the cerebrum, ventricular cavities or passageways, basal ganglia, brainstem, cerebellum, or spinal cord; or is it multifocal or diffuse?

d. If the lesion could be extra-axial, is it:

i. In a meningeal or bony covering?

ii. In a meningeal space: epidural, subdural, or subarachnoid?

iii. In a nerve root, plexus, peripheral nerve, neuromuscular junction, or muscle?

4. When the Pt’s symptoms and signs suggest a neurologic disease, try to classify it as motor, sensory, sensorimotor, headache, or cognitive/behavioral syndrome.

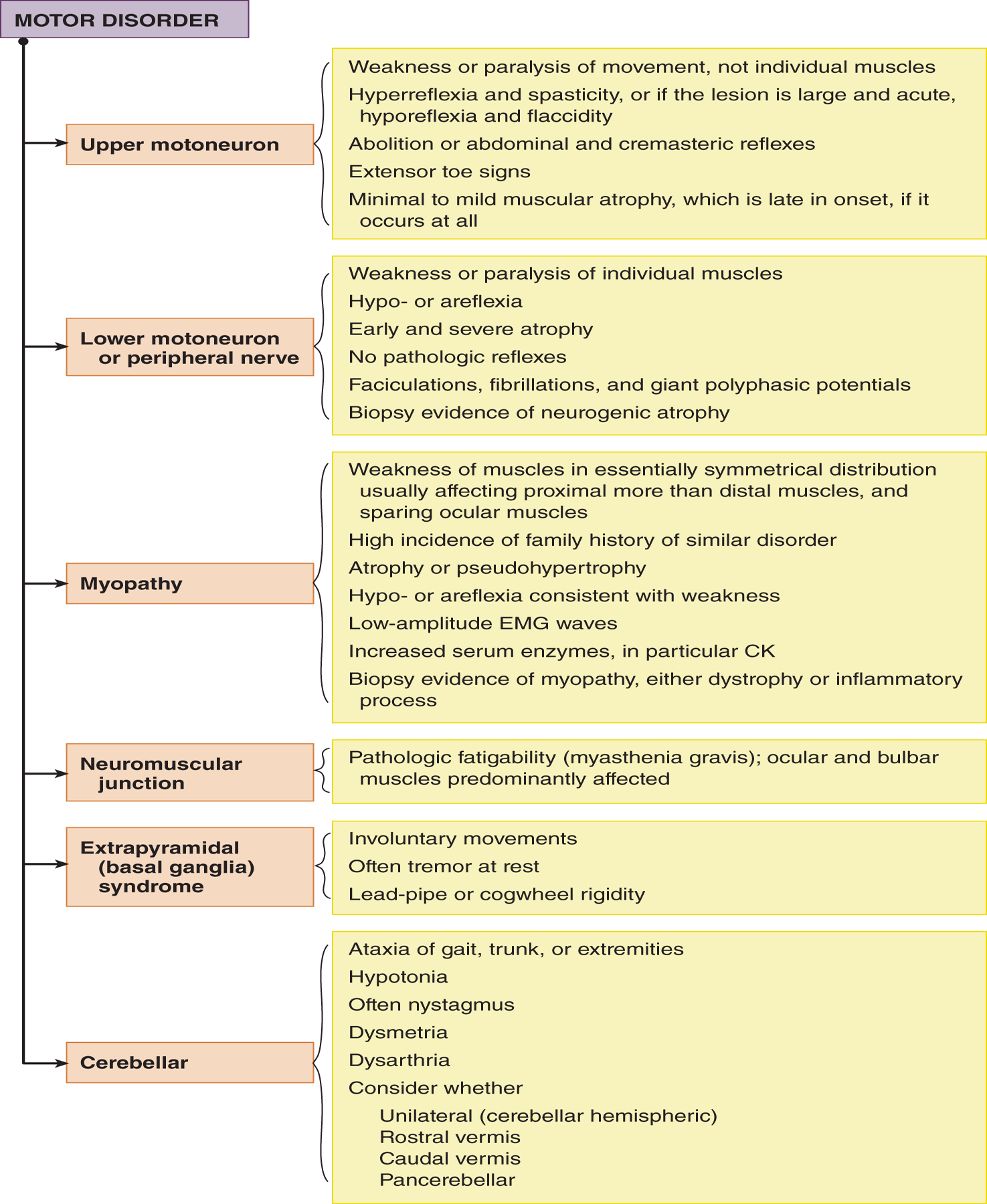

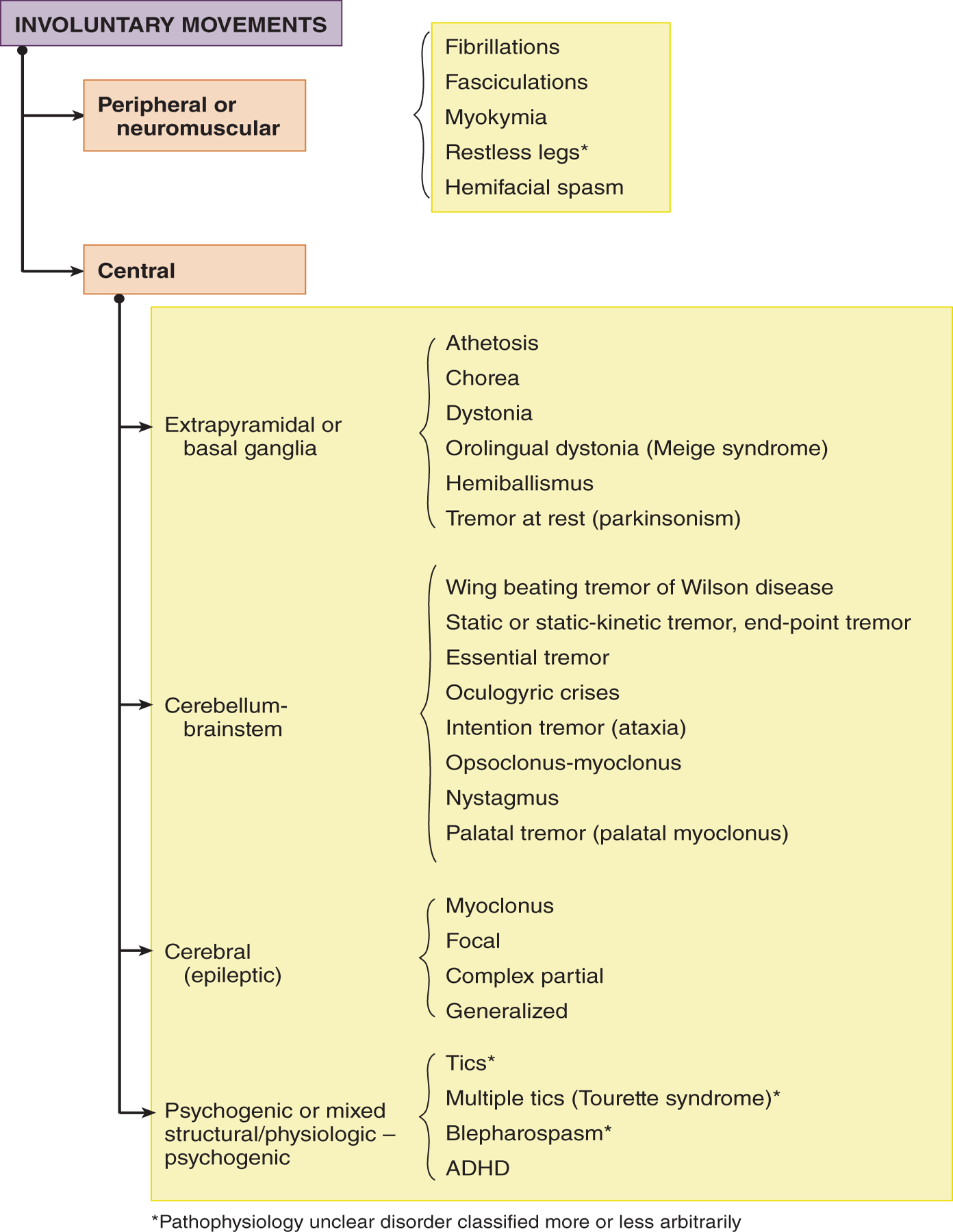

a. If motor, think through Fig. 15-3 to locate the neuronal system affected; if an involuntary movement syndrome, see Fig. 15-4.

b. If sensory, see Fig. 15-5.

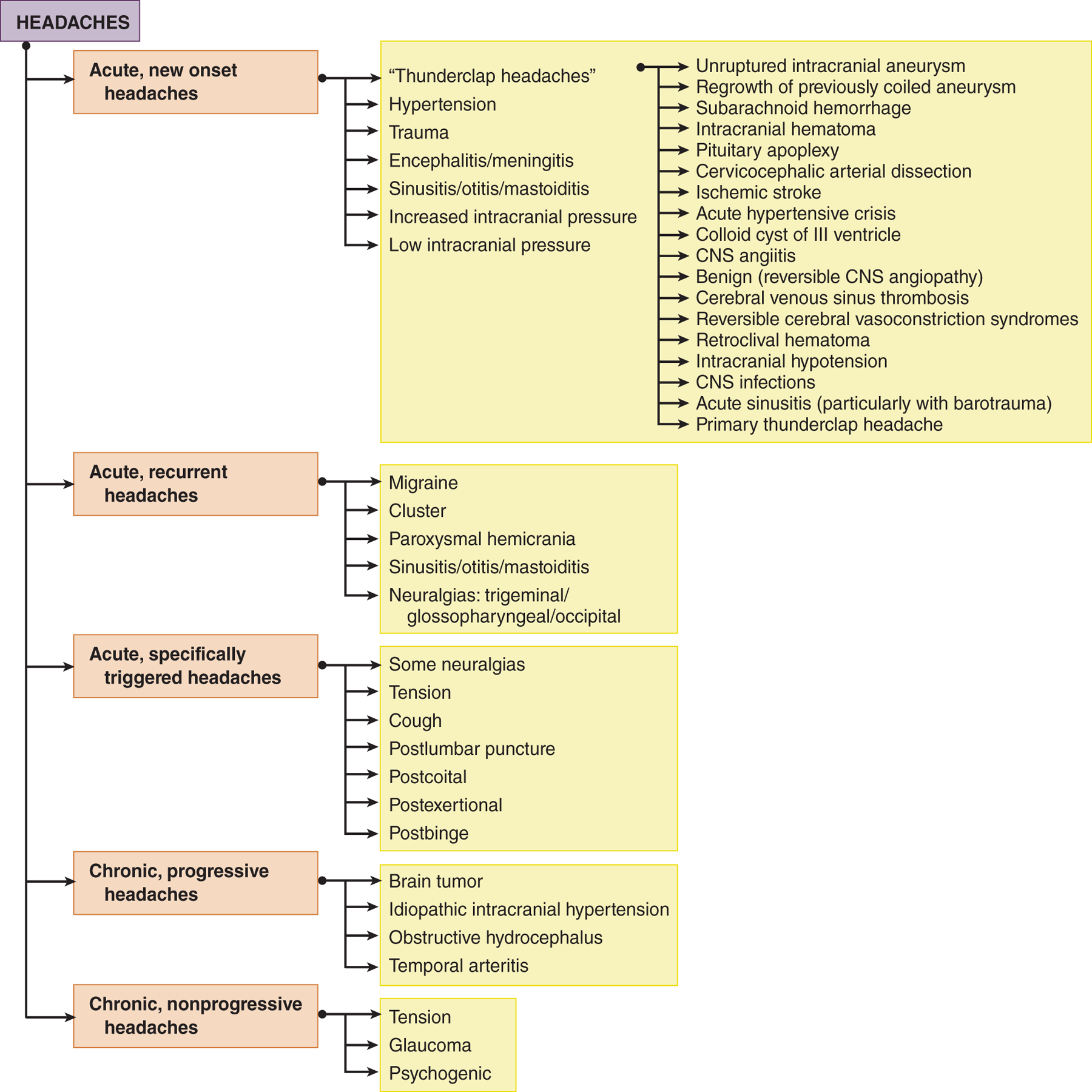

c. If a headache, see Fig. 15-6.

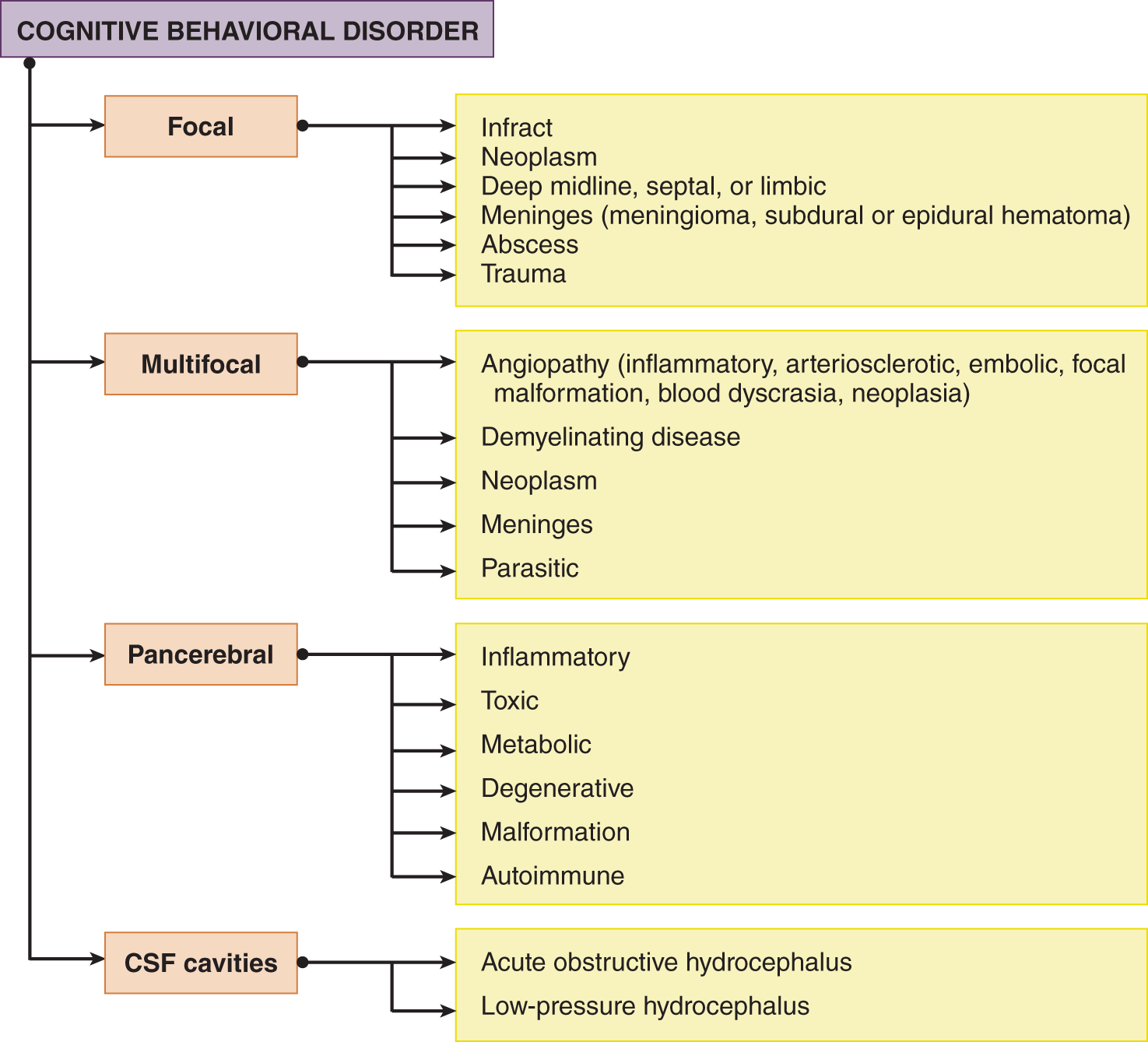

d. If an organic mental syndrome, see Fig. 15-7.

FIGURE 15-3. Consider these loci as possible lesion sites if the patient has symptoms and signs suggesting an organic disorder of the motor system. CK = creatine kinase; EMG = electromyographic.

FIGURE 15-4. Consider these loci as possible lesion sites if the patient has an involuntary movement disorder.

FIGURE 15-5. Consider these loci as possible lesion sites if the patient has a sensory complaint.

FIGURE 15-6. Consider these diagnostic possibilities if the patient has headaches. A-V = arteriovenous.

FIGURE 15-7. Consider these diagnostic possibilities if the patient has mental, emotional, or intellectual deficits that suggest an organic neurologic disorder.

F. What is the lesion or the disease (Table 15-3, question 3)?

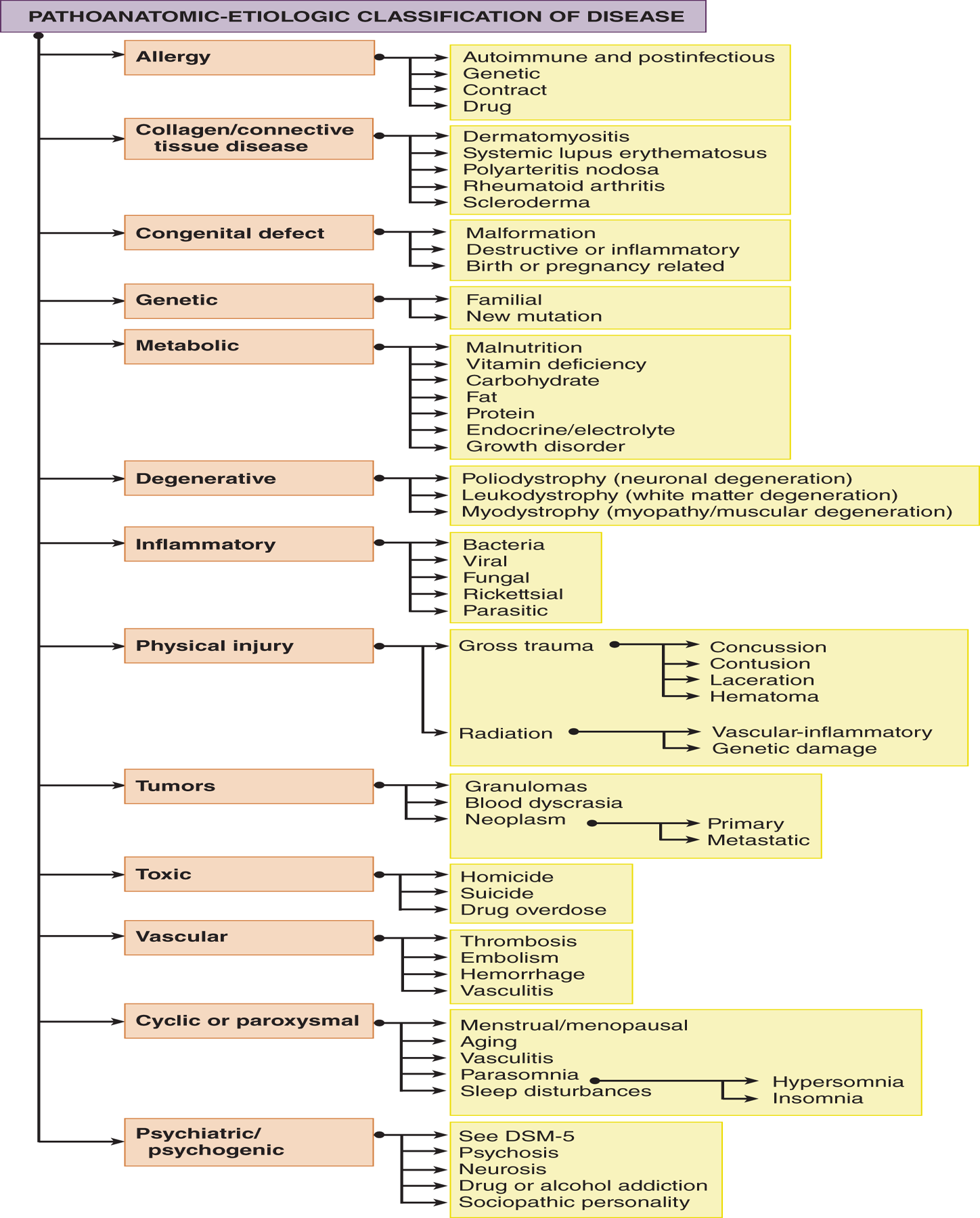

Having hypothesized the neuronal system, or systems, involved, and the lesion site, the Ex next has to hypothesize what the lesion is. For this purpose, systematically think through the entities shown in Fig. 15-8. Then state a provisional diagnosis according to the principle of parsimony: the simplest diagnosis that will explain the signs and symptoms.

FIGURE 15-8. Brief pathoanatomic and etiologic classification of disease. Review this dendrogram systematically for each patient to generate the gamut of etiologic possibilities that may cause the clinical findings. The branching of the dendrogram vertically and to the right can be continued almost endlessly. DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th ed (Video 15-1).

Video 15-1. Young patient with Wernicke’s encephalopathy and severe sensorimotor polyneuropathy post-bariatric surgery, associated with low blood thiamine blood levels.

G. What is the optimum diagnostic management (Table 15-3, question 4)?

What tests, clinical or laboratory, will confirm or reject the provisional diagnosis and establish the final diagnosis?

1. The explicitly stated provisional diagnosis provides the basis to generate a differential diagnosis list. The Ex selects any further clinical tests that will best affirm or deny the provisional diagnosis or point to another diagnosis. Having exhausted all clinical tests, the Ex selects laboratory tests according to these principles:

a. Select the one or two best tests to support or reject the provisional diagnosis.

b. Given tests of approximately equal clinical value, select the simplest, safest, and cheapest ones, but never curtail the investigation in the sole interest of “cost containment.” Failure to diagnose a diagnosable disease is the costliest mistake of all.

c. When faced with a hopeless or untreatable disorder, take all reasonable steps to exclude a treatable disorder.

2. To select the most appropriate laboratory tests, review the possible ones listed in Table 13-1.

H. What is the optimum therapeutic management (Table 15-3, question 5)?

1. State the therapeutic goals and how to meet them. Just what can you hope to do for the Pt?

2. What emotional, educational, or socioeconomic perils does the Pt face because of the illness? What agencies—lay, rehabilitative, vocational, or governmental—might help?

I. What is the optimum preventative management (Table 15-3, question 6)?

1. Having identified the Pt’s illness, the Ex has to identify other persons at risk. How can they be reached and offered prophylaxis? Consider for Pts with environmentally induced, contagious or infectious, or hereditary diseases.

2. Follow the Pt to ensure that your final diagnosis is indeed final and that the Pt’s subsequent course continues to confirm its finality.

V. A PRÉCIS FOR SUCCESS IN THE NEUROLOGIC EXAMINATION

A. Attitudes for success in the neurologic examination

1. Maintain professionalism: Accept neutrally, as purely clinical phenomena, every behavior and every revelation made by the Pt. If you react emotionally to the Pt, you lose the objective judgment required to make correct clinical decisions.

2. Expect the abnormal: By expecting every finding to be abnormal, you will do a much more vigilant examination than if you expect normality.

3. Enjoy the NE: Make the NE a game of friendly challenges to maintain the interest of both yourself and Pt in the outcome of each test. “Let’s see how light a touch you can feel?” Or “How soft a sound you can hear.” “Hold your hands out in front and let’s see how still you can keep them.” In testing strength, “Do your best, don’t let me win,” etc.

B. Overall principles for performance of the neurologic examination

1. Do an organized NE: A disorganized examination is the most common error of all. Correct it by laying out your instruments in order of use and proceeding rostrocaudally, doing the head and cranial nerve examination, motor examination, and sensory examination in order (see the Standard NE at the start of the text).

2. Ensure the Pt’s comfort and safety during each test.

3. Understand each test and each definition operationally: Separate observation and description from interpretation. If you understand the operation and the purpose of each test of the NE, you will interpret the findings correctly.

4. Titrate, or match, the Pt’s sensory or motor functions against yours, whenever possible: Titrate or match visual fields, visual acuity, vibration and hearing thresholds, and strength.

5. Quantify or scale the test results, whenever possible: Measure circumferences of the head and extremities. Scale dysfunctions as minimal, mild, moderate, or severe, or enumerate on a scale from 0 to 4+.

6. Think circuitry: Visualize each neuroanatomic circuit as you test it. Unless you review circuitry daily, you forget it. If you find a neurologic abnormality, review the neighborhood signs that should accompany it by visualizing the conjunction of the circuits of the nervous system and test for these neighborhood signs. If you suspect a CNS lesion, actually draw a cross section of the CNS at the level of the suspected lesion and locate and label the clinically relevant nuclei and tracts. If you suspect a lesion of the PNS, draw the course of the relevant nerve.

7. Consider whether any unusual finding is a normal variation that simply reflects the genetic background of the Pt: Commonly, the Ex fails to call in and examine the entire family to decide about pseudopapilledema, the OFC, height of the arch of the foot, facial features, overall somatotype, etc.

8. Consider whether any finding preexisted: Ptosis, VI nerve palsy, anisocoria, hemiplegia, and atrophy. This precaution is especially important in examining the comatose Pt when a preexisting finding, such as anisocoria, may mislead you. Get old photographs or family videos.

9. Extend the basic NE when required: Reproduce triggering factors: hyperventilation, fatigability during exercise, dizziness on change of position, or trouble in swallowing. Have the Pt return when symptomatic and repeat the tests.

C. The mental status examination

1. Weave in the questions that test the sensorium skillfully, as ordinary conversation, not as an inquisition: Do not ask the who, where, when, and what questions in machine-gun style, except in an acute head injury.

2. Complete the Mini-Mental-State Examination (MMSE) battery and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test, if the history raises the question of cognitive impairment.

D. Examination of the cranial nerves and head

1. Measure the OFC of every infant.

2. Test the visual fields on the diagonals, not on the meridians: Testing on the vertical or horizontal meridians may entirely miss a quadrantic defect (Fig. 3-13).

3. Test pupilloconstriction correctly: Darken the room, ask the Pt to fixate on a distant point to eliminate pupilloconstriction from accommodation, and flash a light into each eye separately from the side. Then do the swinging flashlight test.

4. Test the corneal reflex from the side: Bring the cotton wisp in from the side, out of sight of the Pt’s vision, to avoid a visually induced blink response. Do not use the cotton tip of an applicator stick (no sticks around the eyes).

5. Press on the zygomatic arch (cheekbone), not on the jaw, to test the strength of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and other rotators of the head: Direct pressure on the cheekbone tests the head rotators without working through the lateral pterygoid muscles. If the pterygoids are weak, strong lateral pressure on the jaw may dislocate the temporomandibular joint, especially in elderly and edentulous Pts.

E. Motor examination

1. Recognize that each behavior produced by the conscious or the unconscious Pt establishes the integrity of some neuroanatomic circuit: By observing and correctly interpreting all spontaneous and elicited behaviors of the unconscious Pt, the Ex can test most of the sensory and motor circuits that can be tested in the conscious Pt.

2. Apply the concept of deficit and release phenomena and of neural shock (diaschisis) to the Pt with an acute neurologic lesion: Neural shock (depression) means that acute upper motoneuron lesions manifest only by deficit signs, not by the classic release signs as with chronic lesions. Because of neural shock, signs and symptoms temporarily extend beyond those expected by the actual anatomic size of an acute lesion.

3. Test every Pt’s gait, when possible. Nothing tests the integrity of the Pt’s nervous system so quickly (Chapter 8, Section VI), but Exs often fail to test it.

4. Test strength by use of principles: Review the length–strength law, the law of predominant strength of the antigravity muscles, and the law of matching the Pt and Ex muscle to muscle, particularly in testing finger strength (Fig. 7-3).

5. Elicit the muscle stretch reflexes by a whiplash swing, not a peck. Be a “swinger” of reflex hammers (Fig. 7-5). If no reflexes are elicited, try repositioning and relaxing the part, altering the pressure or tension on the tendon, and use Jendrassik reinforcement.

6. Try first to elicit the extensor toe sign from the lateral side of the foot, not the sole: Demented, psychotic, or Pts with an intellectual disability, the elderly and often the ticklish young, or those with painful peripheral neuropathies resist the discomfort of plantar stimulation but may tolerate pressure on the lateral side of the foot.

F. Sensory examination

1. Establish good communication: Inform the Pt of the nature of the stimulus and the response to make. “Which is the sharpest, number 1 or number 2?” “Is the toe up or down?” etc.

2. Isolate the modality to be tested: Conceal the test object from sight or perception by any modality other than the one being tested.

3. Monitor the Pt’s attention and reliability: The Ex sometimes withholds a stimulus when the Pt expects it, and forewarns the Pt of that possibility.

4. Test temperature discrimination rather than pain around the face and in children: Test temperature discrimination by the tuning-fork and finger methods shown in Fig. 10-4. Pain and temperature sensations test the same pathways, the fewer the pinpricks, the better. Testing temperature discrimination is far more comfortable for every Pt. Children will not accept pain testing, but children as young as 3 years will play the temperature game.

G. Closure (cloture) of the neurologic examination

1. Write out the NE informatively or use a check list to state what you have actually tested and found to be negative or positive (Table 15-1): At least your notes should enable the reader to find out about the Pt’s mental state and whether the Pt can sit, stand, walk, talk, breathe, see, hear, and feel normally. I would rather you simply state that than write out every negative finding, but some negatives are important as exclusionary evidence.

2. Write a three-line summary: If you have come to grips with the clinical problem, you can write it out in no more than three lines, no matter how complicated. Your ability to summarize the findings is the best single test of your ability to function as a physician. “This is a 64-year-old hypertensive African American salesman who had the acute onset of headache, unresponsiveness, eyes deviated to the left, flaccid right hemiplegia, and nuchal rigidity.” From that summary, the probable diagnosis leaps out at you: left hypertensive putaminal hemorrhage probably extending into the ventricle and subarachnoid space.

3. Always recite the diagnostic catechism (Table 15-3): If tempted to make a psychological diagnosis, review the list of structural/physiologic diseases commonly misdiagnosed (Table 14-6).

4. Review the pathoanatomic and etiologic classifications of disease to ensure that you have considered the gamut of possible causes for the clinical findings (Fig. 15-8).

VI. COMFORT: THE ULTIMATE OBJECTIVE OF EVERY CONTACT BETWEEN PATIENT AND PHYSICIAN

For hundreds, even thousands of years, physicians have understood the goals of the medical model and have expressed them in aphorisms. The two given here apparently arose in the Middle Ages, but their exact authorship is unknown. Here is the first:

A painless examination,

A complete cure,

Leaving no blemish behind.

And here is the other:

The physician can only rarely cure,

Can sometimes palliate,

But can always give comfort.

At the end of every Pt–physician contact, the Pt should at least feel benefited and comforted, even when the physician cannot cure or even palliate. Comfort comes not from false optimism, pity, patronizing pap, or condescending platitudes, but from empathy and competence (Video 15-2). Each Pt–physician contact remains incomplete, the ring remains open, and the physician remains but a technocrat, until the Pt feels this beneficence.

Video 15-2. Young patient with past history of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage treated with clipping, discussing her main health concerns.

Learning Objectives for Chapter 15

Learning Objectives for Chapter 15