Platelet and Blood Vessel Disorders

J. Paul Scott, Veronica H. Flood

Megakaryopoiesis

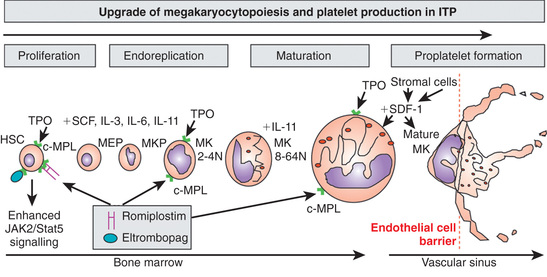

Platelets are nonnucleated cellular fragments produced by megakaryocytes (large polyploid cells) within the bone marrow and other tissues. When the megakaryocyte approaches maturity, budding of the cytoplasm occurs, and large numbers of platelets are liberated. Platelets circulate with a life span of 10-14 days. Thrombopoietin (TPO) is the primary growth factor that controls platelet production (Fig. 511.1 ). Levels of TPO appear to correlate inversely with platelet number and megakaryocyte mass. Levels of TPO are highest in the thrombocytopenic states associated with decreased marrow megakaryopoiesis and may be variable in states of increased platelet production.

The platelet plays multiple hemostatic roles. The platelet surface possesses a number of important receptors for adhesive proteins, including von Willebrand factor (VWF) and fibrinogen, as well as receptors for agonists that trigger platelet aggregation, such as thrombin, collagen, and adenosine diphosphate (ADP). After injury to the blood vessel wall, the extracellular matrix containing adhesive and procoagulant proteins is exposed. Subendothelial collagen binds VWF, which undergoes a conformational change that induces binding of the platelet glycoprotein Ib (GPIb) complex, the VWF receptor. This process is called platelet adhesion. Platelets then undergo activation. During the process of activation, the platelets generate thromboxane A2 from arachidonic acid via the enzyme cyclooxygenase. After activation, platelets release agonists, such as ADP, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), calcium ions (Ca2+ ), serotonin, and coagulation factors, into the surrounding milieu. Binding of VWF to the GPIb complex triggers a complex signaling cascade that results in activation of the fibrinogen receptor, the major platelet integrin glycoprotein αIIb-β3 (GPIIb-IIIa). Circulating fibrinogen binds to its receptor on the activated platelets, linking platelets in a process called aggregation. This series of events forms a hemostatic plug at the site of vascular injury. The serotonin and histamine that are liberated during activation increase local vasoconstriction. In addition to acting in concert with the vessel wall to form the platelet plug, the platelet provides the catalytic surface on which coagulation factors assemble and eventually generate thrombin through a sequential series of enzymatic cleavages. Lastly, the platelet contractile proteins and cytoskeleton mediate clot retraction.

Thrombocytopenia

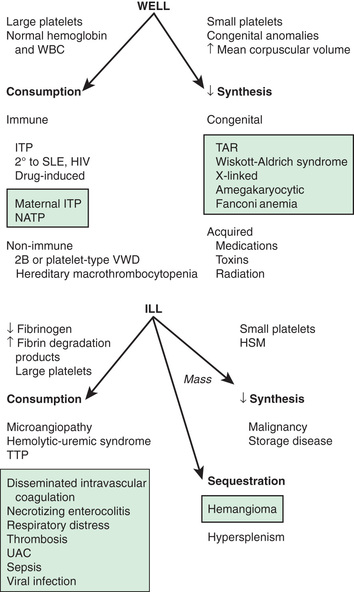

The normal platelet count is 150-450 × 109 /L. Thrombocytopenia refers to a reduction in platelet count to <150 × 109 /L, although clinically significant bleeding is not seen until counts drop well below 50 × 109 /L. Causes of thrombocytopenia include decreased production on either a congenital or an acquired basis, sequestration of the platelets within an enlarged spleen or other organ, and increased destruction of normally synthesized platelets on either an immune or a nonimmune basis (Tables 511.1 and 511.2 and Fig. 511.2 ) (see Chapter 502 ).

Table 511.1

Differential Diagnosis of Thrombocytopenia in Children and Adolescents

HELLP, Hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ITP, immune thrombocytopenic purpura; VWD, von Willebrand disease.

From Wilson DB: Acquired platelet defects. In Orkin SH, Fisher DE, Ginsberg D, et al, editors: Nathan and Oski's hematology of infancy and childhood, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2015, Saunders Elsevier (Box 34.1, p 1077).

Table 511.2

Classification of Fetal and Neonatal Thrombocytopenias*

| CONDITION | |

|---|---|

| Fetal | Alloimmune thrombocytopenia |

| Congenital infection (e.g., CMV, toxoplasma, rubella, HIV) | |

| Aneuploidy (e.g., trisomy 18, 13, or 21, triploidy, Turner syndrome) | |

| Autoimmune condition (e.g., ITP, SLE) | |

| Severe Rh hemolytic disease | |

| Congenital/inherited (e.g., Wiskott-Aldrich, Noonan, Cornelia deLange, Jacobsen syndromes) | |

| Early-onset neonatal (<72 hr) | Placental insufficiency (e.g., PET, IUGR, diabetes) |

| Perinatal asphyxia | |

| Perinatal infection (e.g., Escherichia coli , GBS, herpes simplex) | |

| DIC | |

| Alloimmune thrombocytopenia | |

| Autoimmune condition (e.g., ITP, SLE) | |

| Congenital infection (e.g., CMV, toxoplasma, rubella, HIV) | |

| Thrombosis (e.g., aortic, renal vein) | |

| Bone marrow replacement (e.g., congenital leukemia) | |

| Kasabach-Merritt syndrome | |

| Metabolic disease (e.g., propionic and methylmalonic acidemia) | |

| Congenital/inherited (e.g., TAR, CAMT) | |

| Late-onset neonatal (>72 hr) | Late-onset sepsis |

| NEC | |

| Congenital infection (e.g., CMV, toxoplasma, rubella, HIV) | |

| Autoimmune | |

| Kasabach-Merritt syndrome | |

| Metabolic disease (e.g., propionic and methylmalonic acidemia) | |

| Congenital/inherited (e.g., TAR, CAMT) |

* The most common conditions are shown in bold .

CAMT, Congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia; CMV, cytomegalovirus; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; GBS, group B streptococcus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ITP, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; PET, preeclampsia; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; TAR, thrombocytopenia with absent radii.

From Roberts I, Murray NA: Neonatal thrombocytopenia: causes and management, Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 88:F359–F364, 2003.

Idiopathic (Autoimmune) Thrombocytopenic Purpura

J. Paul Scott, Veronica H. Flood

The most common cause of acute onset of thrombocytopenia in an otherwise well child is (autoimmune) idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP ).

Epidemiology

In a small number of children, estimated at 1 in 20,000, 1-4 wk after exposure to a common viral infection, an autoantibody directed against the platelet surface develops with resultant sudden onset of thrombocytopenia. A recent history of viral illness is described in 50–65% of children with ITP. The peak age is 1-4 yr, although the age ranges from early in infancy to elderly. In childhood, males and females are equally affected. ITP seems to occur more often in late winter and spring after the peak season of viral respiratory illness.

Pathogenesis

The exact antigenic target for most such antibodies in most cases of childhood acute ITP remains undetermined, although in chronic ITP many patients demonstrate antibodies against αIIb-β3 and GPIb. After binding of the antibody to the platelet surface, circulating antibody-coated platelets are recognized by the Fc receptor on splenic macrophages, ingested, and destroyed. Most common viruses have been described in association with ITP, including Epstein-Barr virus (EBV; see Chapter 281 ) and HIV (see Chapter 302 ). EBV-related ITP is usually of short duration and follows the course of infectious mononucleosis. HIV-associated ITP is usually chronic. In some patients, ITP appears to arise in children infected with Helicobacter pylori or rarely following vaccines.

Clinical Manifestations

The classic presentation of ITP is a previously healthy 1-4 yr old child who has sudden onset of generalized petechiae and purpura. The parents often state that the child was fine yesterday and now is covered with bruises and purple dots. There may be bleeding from the gums and mucous membranes, particularly with profound thrombocytopenia (platelet count <10 × 109 /L). There is a history of a preceding viral infection 1-4 wk before the onset of thrombocytopenia. Findings on physical examination are normal, other than petechiae and purpura. Splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, bone pain, and pallor are rare. A simple classification system from the United Kingdom has been proposed to characterize the severity of bleeding in ITP on the basis of symptoms and signs rather than platelet count, as follows:

- 1. No symptoms

- 2. Mild symptoms: bruising and petechiae, occasional minor epistaxis, very little interference with daily living

- 3. Moderate symptoms: more severe skin and mucosal lesions, more troublesome epistaxis and menorrhagia

- 4. Severe symptoms: bleeding episodes—menorrhagia, epistaxis, melena—requiring transfusion or hospitalization, symptoms interfering seriously with the quality of life

The presence of abnormal findings such as hepatosplenomegaly, bone or joint pain, remarkable lymphadenopathy other cytopenias, or congenital anomalies suggests other diagnoses (leukemia, syndromes). When the onset is insidious, especially in an adolescent, chronic ITP or the possibility of a systemic illness, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), is more likely.

Outcome

Severe bleeding is rare (<3% of cases in 1 large international study). In 70–80% of children who present with acute ITP, spontaneous resolution occurs within 6 mo. Therapy does not appear to affect the natural history of the illness. Fewer than 1% of patients develop an intracranial hemorrhage (ICH). Proponents of interventional therapy argue that the objective of early therapy is to raise the platelet count to >20 × 109 /L and prevent the rare development of ICH. There is no evidence that therapy prevents serious bleeding. Approximately 20% of children who present with acute ITP go on to have chronic ITP. The outcome/prognosis may be related more to age; ITP in younger children is more likely to resolve, whereas development of chronic ITP in adolescents approaches 50%.

Laboratory Findings

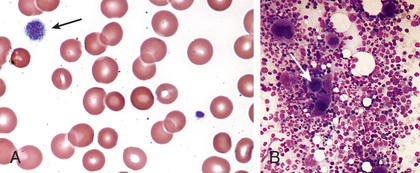

Severe thrombocytopenia (platelet count <20 × 109 /L) is common, and platelet size is normal or increased, reflective of increased platelet turnover (Fig. 511.3 ). In acute ITP the hemoglobin value, white blood cell (WBC) count, and differential count should be normal. Hemoglobin may be decreased if there have been profuse nosebleeds (epistaxis) or menorrhagia. Bone marrow examination shows normal granulocytic and erythrocytic series, with characteristically normal or increased numbers of megakaryocytes. Some of the megakaryocytes may appear to be immature and reflect increased platelet turnover. Indications for bone marrow aspiration/biopsy include an abnormal WBC count or differential or unexplained anemia, as well as history and physical examination findings suggestive of a bone marrow failure syndrome or malignancy. Other laboratory tests should be performed as indicated by the history and examination. HIV studies should be done in at-risk populations, especially sexually active teens. Platelet antibody testing is seldom useful in acute ITP. A direct antiglobulin test (Coombs) should be done if there is unexplained anemia, to rule out Evans syndrome (autoimmune hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia) (see Chapter 484 ). Evans syndrome may be idiopathic or an early sign of systemic lupus erythematosus, autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome or common variable immunodeficiency syndrome. An ANA should be considered in adolescents, especially with other features of SLE (see Chapter 183 ).

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The well-appearing child with moderate to severe thrombocytopenia, an otherwise normal complete blood cell count (CBC), and normal exam findings has a limited differential diagnosis that includes exposure to medication inducing drug-dependent antibodies, splenic sequestration because of previously unappreciated portal hypertension, and rarely, early aplastic processes, such as Fanconi anemia (see Chapter 495 ). Other than congenital thrombocytopenia syndromes (see Chapter 511.8 ), such as thrombocytopenia–absent radius (TAR) syndrome and MYH9-related thrombocytopenia, most marrow processes that interfere with platelet production eventually cause abnormal synthesis of red blood cells (RBCs) and WBCs and therefore manifest diverse abnormalities on the CBC. Disorders that cause increased platelet destruction on a nonimmune basis are usually serious systemic illnesses with obvious clinical findings such as hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) (see Fig. 511.2 , and Table 510.1 in Chapter 510 ). Patients receiving heparin may develop heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Isolated enlargement of the spleen suggests the potential for hypersplenism caused by liver disease or portal vein thrombosis. Autoimmune thrombocytopenia may be an initial manifestation of SLE, HIV infection, common variable immunodeficiency, and rarely, lymphoma or autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome. Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome must be considered in young males found to have thrombocytopenia with small platelets, particularly if there is a history of eczema and recurrent infection (see Chapter 152.2 ).

Treatment

A number of treatment options exist (Table 511.3 ), but there are no data showing that treatment affects either short- or long-term clinical outcome of ITP. Many patients with new-onset ITP have mild symptoms, with findings limited to petechiae and purpura on the skin, despite severe thrombocytopenia. Compared with untreated controls, treatment appears to be capable of inducing a more rapid rise in platelet count to the theoretically safe level of >20 × 109 /L, although no data indicate that early therapy prevents ICH. Antiplatelet antibodies bind to transfused platelets as well as they do to autologous platelets. Thus, platelet transfusion in ITP is usually contraindicated unless life-threatening bleeding is present. Initial approaches to the management of ITP include the following:

Table 511.3

Treatment Options for Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP)

| PROS | CONS | COST | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observation | Does not expose patient to unnecessary medications | May increase parent and physician anxiety | Relatively inexpensive |

| IVIG | Rapid response in most cases | IV administration, side effects | Expensive |

| Corticosteroids | Oral, effective in 70–80% of patients, minimal side effects with short courses | Side effects, may not affect long term outcome | Inexpensive |

| Rituximab | Long-term remission in 40–60% of patients | IV administration, immune suppression, potential for reactivation of hepatitis | Very expensive |

| Splenectomy | Curative in 80% of patients | Requires surgery and anesthesia, lifelong risk of infection | Expensive |

| Thrombopoietin receptor agonists | Potential for oral administration, 40–60% of patients respond | Not curative, usually required long term, can cause elevated liver enzymes | Very expensive |

IV, Intravenous; IVIG, intravenous immune globulin.

Adapted from Flood VH, Scott JP: Bleeding and thrombosis. In Kliegman R, Lye P, Bordini B, et al, editors: Nelson pediatric symptom-based diagnosis, Philadelphia, 2017, Saunders Elsevier.

- 1. No therapy other than education and counseling of the family and patient for patients with minimal, mild, and moderate symptoms, as defined earlier. This approach emphasizes the usually benign nature of ITP and avoids the therapeutic roller coaster that ensues once interventional therapy is begun. This approach is much less costly, and side effects are minimal. Observation is recommended by the American Society of Hematology guidelines for children with only mild bleeding symptoms such as bruising or petechiae.

- 2. Treatment with either IVIG or corticosteroids, particularly for children who present with mucocutaneous bleeding. As American Society of Hematology guidelines state, “A single dose of IVIG [intravenous immune globulin] (0.8-1.0 g/kg) or a short course of corticosteroids should be used as first-line treatment.” IVIG at a dose of 0.8-1.0 g/kg/day for 1-2 days induces a rapid rise in platelet count (usually >20 × 109 /L) in 95% of patients within 48 hr. IVIG appears to induce a response by downregulating Fc-mediated phagocytosis of antibody-coated platelets. IVIG therapy is both expensive and time-consuming to administer. Additionally, after infusion, there is a high frequency of headaches and vomiting, suggestive of IVIG-induced aseptic meningitis.

- 3. Corticosteroid therapy has been used for many years to treat acute and chronic ITP in adults and children. Doses of prednisone at 1-4 mg/kg/24 hr appear to induce a more rapid rise in platelet count than in untreated patients with ITP. Corticosteroid therapy is usually continued for short course until a rise in platelet count to >20 × 109 /L has been achieved to avoid the long-term side effects of corticosteroid therapy, especially growth failure, diabetes mellitus, and osteoporosis.

Each of these medications may be used to treat ITP exacerbations, which usually occur several weeks after an initial course of therapy. In the special case of ICH, multiple modalities should be used, including platelet transfusion, IVIG, high-dose corticosteroids, and prompt consultation by neurosurgery and surgery.

There is no consensus regarding the management of acute childhood ITP, except that patients who are bleeding significantly (<5% of children with ITP) should be treated. Intracranial hemorrhage remains rare, and there are no data showing that treatment actually reduces its incidence. Mucosal bleeding in particular is the most significant in terms of predicting severe bleeding.

The role of splenectomy in ITP should be reserved for 2 circumstances: (1) the older child (≥4 yr) with severe ITP that has lasted >1 yr (chronic ITP) and whose symptoms are not easily controlled with therapy and (2) when life-threatening hemorrhage (ICH) complicates acute ITP, if the platelet count cannot be corrected rapidly with transfusion of platelets and administration of IVIG and corticosteroids. Splenectomy is associated with a lifelong risk of overwhelming postsplenectomy infection caused by encapsulated organisms, increased risk of thrombosis, and the potential development of pulmonary hypertension in adulthood. As an alternative to splenectomy, rituximab has been used “off label” in children to treat chronic ITP. In 30–40% of children, rituximab has induced a partial or complete remission. Thrombopoietin receptor agonists have also been used to increase platelet count and are approved for pediatric use.

Chronic Autoimmune Thrombocytopenic Purpura

Approximately 20% of patients who present with acute ITP have persistent thrombocytopenia for >12 mo and are said to have chronic ITP. At that time, a careful reevaluation for associated disorders should be performed, especially for autoimmune disease (e.g., SLE), chronic infectious disorders (e.g., HIV), and nonimmune causes of chronic thrombocytopenia, such as type 2B and platelet-type von Willebrand disease, X-linked thrombocytopenia, autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, common variable immunodeficiency syndrome, autosomal macrothrombocytopenia, and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (also X-linked). The presence of coexisting H. pylori infection should be considered and, if found, treated. Therapy should be aimed at controlling symptoms and preventing serious bleeding. In ITP the spleen is the primary site of both antiplatelet antibody synthesis and platelet destruction. Splenectomy is successful in inducing complete remission in 64–88% of children with chronic ITP. This effect must be balanced against the lifelong risk of overwhelming postsplenectomy infection. This decision is often affected by quality-of-life issues, as well as the ease with which the child can be managed using medical therapy, such as IVIG, corticosteroids, IV anti-D, or rituximab. Two effective agents that act to stimulate thrombopoiesis, romiplostim and eltrombopag (see Fig. 511.1 ), are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat adults and children with chronic ITP. Although these do not address the mechanism of action of ITP, the increase in platelet count may be enough to compensate for the increased destruction and allow the patient to have resolution of bleeding and maintain a platelet count >50 × 109 /L.

Bibliography

Boyle S, White RH, Brunson A, et al. Splenectomy and the incidence of venous thromboembolism and sepsis in patients with immune thrombocytopenia. Blood . 2013;121(23):4782–4790.

Breakey VR, Blanchette VS. Childhood immune thrombocytopenia: a changing therapeutic landscape. Semin Thromb Hemost . 2011;37(7):745–755.

Chaturvedi S, McCrae KR. Treatment of chronic immune thrombocytopenia in children with romiplostim. Lancet . 2016;388:4–6.

Cooper N, Bussel JB. The long-term impact of rituximab for childhood immune thrombocytopenia. Curr Rheumatol Rep . 2010;12(2):94–100.

Heitink-Pollé KM, Njisten J, Boonacker CW, et al. Clinical and laboratory predictors of chronic immune thrombocytopenia in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood . 2015;124:3295–3307.

Kühne T, Imbach P. Management of children and adolescents with primary immune thrombocytopenia: controversies and solutions. Vox Sang . 2013;104(1):55–66.

Mitchell WB, Bussel JB. Thrombopoietin receptor agonists: a critical review. Semin Hematol . 2015;52:46–52.

Neunert C, Noroozi N, Norman G, et al. Severe bleeding events in adults and children with primary immune thrombocytopenia: a systematic review. J Thromb Haemost . 2015;13:457–464.

Neunert CE, Buchanan GR, Imbach P, et al. Bleeding manifestations and management of children with persistent and chronic immune thrombocytopenia: data from the intercontinental cooperative ITP Study Group (ICIS). Blood . 2013;121(22):4457–4462.

Neunert C, Lim W, Crowther M, et al. American society of hematology. The American society of hematology 2011 evidence-based practice guideline for immune thrombocytopenia. Blood . 2011;117(16):4190–4207.

O'Leary ST, Glanz JM, McClure DL, et al. The risk of immune thrombocytopenic purpura after vaccination in children and adolescents. Pediatrics . 2012;129(2):248–255.

Price V. Auto-immune lymphoproliferative disorder and other secondary immune thrombocytopenias in childhood. Pediatr Blood Cancer . 2013;60(Suppl 1):S12–S14.

Psaila B, Cooper N. B-cell depletion in immune thrombocytopenia. Lancet . 2015;385:1599–1600.

Psaila B, Petrovic A, Page LK, et al. Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) in children with immune thrombocytopenic (ITP): study of 40 cases. Blood . 2009;114:4777–4783.

Revel-Vilk S, Yacobovich J, Frank S, et al. Age and duration of bleeding symptoms at diagnosis best predict resolution of childhood immune thrombocytopenia at 3,6, and 12 months. J Pediatr . 2013;163:1335–1339.

Teachey DT, Lambert MP. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune cytopenias in childhood. Pediatr Clin North Am . 2013;60:1489–1511.

Yacobovich J, Revel-Vilk S, Tamary H. Childhood immune thrombocytopenia—who will spontaneously recover? Semin Hematol . 2013;50(Suppl 1):S71–S74.

Drug-Induced Thrombocytopenia

J. Paul Scott, Veronica H. Flood

A number of drugs are associated with immune thrombocytopenia as the result of either an immune process or megakaryocyte injury. Some common drugs used in pediatrics that cause thrombocytopenia include valproic acid, phenytoin, carbamazepine, sulfonamides, vancomycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (and rarely an associated thrombosis) is seldom seen in pediatrics, but it occurs when, after exposure to heparin, the patient has an antibody directed against the heparin–platelet factor 4 complex. Recommended treatment for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia includes direct thrombin inhibitors such as argatroban or danaparoid and removal of all sources of heparin, including line flushes.

Bibliography

Cuker A. Management of the multiple phases of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Thromb Haemost . 2016;116:835–842.

Curtis BR. Drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia: incidence, clinical features, laboratory testing, and pathogenic mechanisms. Immunohematology . 2014;30:55–65.

Greinacher A. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med . 2015;373(13):252–260.

Greinacher A. Clinical practice: heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med . 2015;373:252–261.

Kam T, Alexander M. Drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia. J Pharm Pract . 2014;27:430–439.

Nonimmune Platelet Destruction

J. Paul Scott, Veronica H. Flood

The syndromes of DIC (see Chapter 510 ), HUS (see Chapter 538.5 ), and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (see Chapter 511.5 ) share the hematologic picture of a thrombotic microangiopathy in which there is RBC destruction and consumptive thrombocytopenia caused by platelet and fibrin deposition in the microvasculature. The microangiopathic hemolytic anemia is characterized by the presence of RBC fragments, including helmet cells, schistocytes, spherocytes, and burr cells.

Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura

J. Paul Scott, Veronica H. Flood

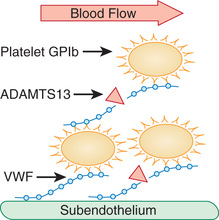

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a rare thrombotic microangiopathy characterized by the pentad of fever, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, abnormal renal function, and central nervous system (CNS) changes that is clinically similar to HUS (Table 511.4 ). Although TTP can be congenital, it usually presents in adults and occasionally in adolescents. Microvascular thrombi within the CNS cause subtle, shifting neurologic signs that vary from changes in affect and orientation to aphasia, blindness, and seizures. Initial manifestations are often nonspecific (weakness, pain, emesis); prompt recognition of this disorder is critical. Laboratory findings provide important clues to the diagnosis and show microangiopathic hemolytic anemia characterized by morphologically abnormal RBCs, with schistocytes, spherocytes, helmet cells, and an elevated reticulocyte count in association with thrombocytopenia. Coagulation studies are usually nondiagnostic. Blood urea nitrogen and creatinine are sometimes elevated. The treatment of acquired TTP is plasmapheresis (plasma exchange), which is effective in 80–95% of patients. Treatment with plasmapheresis should be instituted on the basis of thrombocytopenia and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia even if other symptoms are not yet present. Rituximab, corticosteroids, and splenectomy are reserved for refractory cases. Caplacizumab, an anti-VWF humanized immunoglobulin, blocks the interaction of ultralarge VWF multimers with platelets and many result in rapid resolution of acute TTP.

Table 511.4

ADAMTS13 Deficiency and Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura

| DISEASE | PATHOPHYSIOLOGY | LAB FINDINGS | MANAGEMENT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) |

Acquired : Ab to ADAMTS13 Congenital : Inadequate ADAMTS13 production |

Ab to ADAMTS13 ADAMTS13 <10% |

Acquired : Plasmapheresis with plasma Congenital : Scheduled plasma infusions |

Autoimmune TTP may be transient, recurrent, drug (ticlopidine, clopidogrel) associated, or seen in some pregnancy-associated cases of TTP.

ADAMTS13 mutations are often familial and chronic-relapsing RRP.

The majority of cases of TTP are caused by an autoantibody-mediated deficiency of ADAMTS13 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif member 13) that is responsible for cleaving the high-molecular-weight multimers of VWF and appears to play a pivotal role in the evolution of the thrombotic microangiopathy (Fig. 511.4 ). In contrast, levels of the metalloproteinase in HUS are usually normal. Congenital deficiency of the metalloproteinase causes rare familial cases of TTP/HUS, usually manifested as recurrent episodes of thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, and renal involvement, with or without neurologic changes, that often present in infancy after an intercurrent illness. Abnormalities of the complement system have now also been implicated in rare cases of familial TTP. ADAMTS13 deficiency can be treated by repeated infusions of fresh-frozen plasma.

Bibliography

George JN, Nester CM. Syndromes of thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med . 2014;371(7):654–664.

Kappler S, Ronan-Bentle S, Graham A. Thrombotic microangiopathies (TTP, HUS, HELLP). Hematol Oncol Clin North Am . 2017;31:1081–1103.

Loirat C, Coppo P, Veyradier A. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in children. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2013;25:216–224.

Mariotte E, Veyradier A. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: from diagnosis to therapy. Curr Opin Crit Care . 2015;21:593–601.

Ortel TL, Erkan D, Kitchens CS. How I treat catastrophic thrombotic syndromes. Blood . 2015;126:1285–1293.

Peyvandi F, Scully M, Kremer-Hovinga JA, et al. Caplacizumab for acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura. N Engl J Med . 2016;374(6):511–522.

Reese JA, Muthurajah DS, Kremer Hovinga JA, et al. Children and adults with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura associated with severe, acquired ADAMTS13 deficiency: comparison of incidence, demographic and clinical features. Pediatr Blood Cancer . 2013;60:1676–1682.

Sadler JE. Pathophysiology of thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura. Blood . 2017;130(10):1181.

Sadler JE, Moake JL, Miyata T, George JN. Recent advances in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program . 2004;2004:407–423.

Scully M, Cataland S, Coppo P, et al. Consensus on the standardization of terminology in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and related thrombotic microangiopathies. J Thromb Haemost . 2016;15:312–322.

Kasabach-Merritt Syndrome

J. Paul Scott, Veronica H. Flood

See also Chapter 669 .

The association of a giant hemangioma with localized intravascular coagulation causing thrombocytopenia and hypofibrinogenemia is called Kasabach-Merritt syndrome. In most patients the site of the hemangioma is obvious, but retroperitoneal and intraabdominal hemangiomas may require body imaging for detection. Inside the hemangioma there is platelet trapping and activation of coagulation, with fibrinogen consumption and generation of fibrin(ogen) degradation products. Arteriovenous malformation within the lesions can cause heart failure. Pathologically, Kasabach-Merritt syndrome appears to develop more often as a result of a kaposiform hemangioendothelioma or tufted hemangioma rather than a simple hemangioma. The peripheral blood smear shows microangiopathic changes.

Multiple modalities have been used to treat Kasabach-Merritt syndrome, including propranolol, surgical excision (if possible), laser photocoagulation, high-dose corticosteroids, local radiation therapy, antiangiogenic agents such as interferon-α2 , and vincristine. Over time, most patients who present in infancy have regression of the hemangioma. Treatment of the associated coagulopathy may benefit from a trial of antifibrinolytic therapy with ε-aminocaproic acid (Amicar) or anticoagulation with low-molecular-weight heparin.

Bibliography

Croteau SE, Gupta D. The clinical spectrum of kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma. Semin Cutan Med Surg . 2016;35:147–152.

Drolet BA, Trenor CC 3rd, Brandão LR, et al. Consensus-derived practice standards plan for complicated kaposiform hemangioendothelioma. J Pediatr . 2013;163:285–291.

Sequestration

J. Paul Scott, Veronica H. Flood

Thrombocytopenia develops in individuals with massive splenomegaly because the spleen acts as a sponge for platelets and sequesters large numbers. Most such patients also have mild leukopenia and anemia on CBC. Individuals who have thrombocytopenia caused by splenic sequestration should undergo a workup to diagnose the etiology of splenomegaly, including infectious, inflammatory, infiltrative, neoplastic, obstructive, and hemolytic causes.

Congenital Thrombocytopenic Syndromes

J. Paul Scott, Veronica H. Flood

See Table 511.2 .

Congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia (CAMT) usually manifests within the 1st few days to week of life, when the child presents with petechiae and purpura caused by profound thrombocytopenia. CAMT is caused by a rare defect in hematopoiesis as a result of a mutation in the stem cell TPO receptor (MPL). Other than skin and mucous membrane abnormalities, findings on physical examination are normal. Examination of the bone marrow shows an absence of megakaryocytes. These patients often progress to marrow failure (aplasia) over time. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is curative.

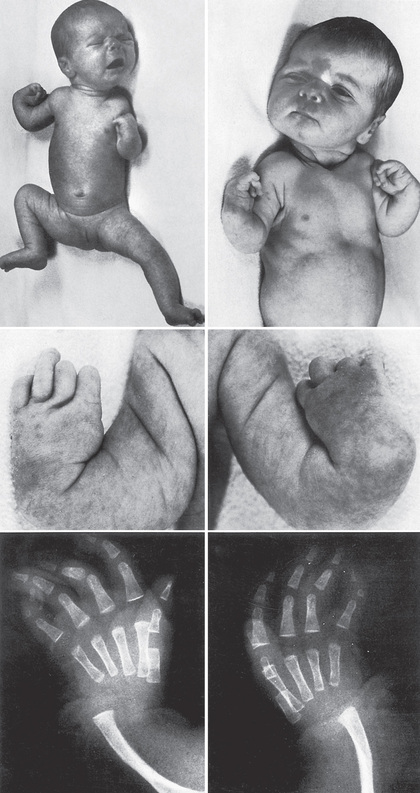

Thrombocytopenia–absent radius (TAR) syndrome consists of thrombocytopenia (absence or hypoplasia of megakaryocytes) that presents in early infancy with bilateral radial anomalies of variable severity, ranging from mild changes to marked limb shortening (Fig. 511.5 ). Many such individuals also have other skeletal abnormalities of the ulna, radius, and lower extremities. Thumbs are present . Intolerance to cow's milk formula (present in 50%) may complicate management by triggering gastrointestinal bleeding, increased thrombocytopenia, eosinophilia, and a leukemoid reaction. The thrombocytopenia of TAR syndrome frequently remits over the 1st few yr of life. The molecular basis of TAR syndrome is linked to RBM8A . A few patients have been reported to have a syndrome of amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia with radioulnar synostosis caused by a mutation in the HOXA11 gene. Different from TAR syndrome, this mutation causes marrow aplasia.

Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS) is characterized by thrombocytopenia, with tiny platelets, eczema, and recurrent infection as a consequence of immune deficiency (see Chapter 152.2 ). WAS is inherited as an X-linked disorder, and the gene for WAS has been sequenced. The WAS protein appears to play an integral role in regulating the cytoskeletal architecture of both platelets and T lymphocytes in response to receptor-mediated cell signaling. The WAS protein is common to all cells of hematopoietic lineage. Molecular analysis of families with X-linked thrombocytopenia has shown that many affected members have a point mutation within the WAS gene, whereas individuals with the full manifestation of WAS have large gene deletions. Examination of the bone marrow in WAS shows the normal number of megakaryocytes, although they may have bizarre morphologic features. Transfused platelets have a normal life span. Splenectomy often corrects the thrombocytopenia, suggesting that the platelets formed in WAS have accelerated destruction. After splenectomy, these patients are at increased risk for overwhelming infection and require lifelong antibiotic prophylaxis against encapsulated organisms. Approximately 5–15% of patients with WAS develop lymphoreticular malignancies. Successful HSCT cures WAS. X-linked macrothrombocytopenia and dyserythropoiesis have been linked to mutations in the GATA1 gene, an erythroid and megakaryocytic transcription factor.

MYH9-related thrombocytopenia comprises a number of diverse hereditary thrombocytopenia syndromes (e.g., Sebastian, Epstein, May-Hegglin, Fechtner) characterized by autosomal dominant macrothrombocytopenia, neutrophil inclusion bodies, and a variety of physical anomalies, including sensorineural deafness, renal disease, and eye disease. These have all been shown to be caused by different mutations in the MYH9 gene (nonmuscle myosin-IIa heavy chain). The thrombocytopenia is usually mild and not progressive. Some other individuals with recessively inherited macrothrombocytopenia have abnormalities in chromosome 22q11. Mutations in the gene for glycoprotein Ibβ, an essential component of the platelet VWF receptor, can result in Bernard-Soulier syndrome (see Chapter 511.13 ).

Bibliography

Albers CA, Newbury-Ecob R, Ouwehand WH, Ghevaert C. New insights into the genetic basis of TAR (thrombocytopenia-absent radii) syndrome. Curr Opin Genet Dev . 2013;23:316–323.

Balduini CL, Savoia A. Genetics of familial forms of thrombocytopenia. Hum Genet . 2012;131(12):1821–1832.

Geddes AE. Congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia. Pediatr Blood Cancer . 2011;57:199–203.

Worth AJ, Thrasher AJ. Current and emerging treatment options for Wiskott-aldrich syndrome. Expert Rev Clin Immunol . 2015;11:1015–1032.

Neonatal Thrombocytopenia

J. Paul Scott, Veronica H. Flood

See also Chapter 124.4 .

Thrombocytopenia in the newborn rarely is indicative of a primary disorder of megakaryopoiesis. It is usually the result of systemic illness or transfer of maternal antibodies directed against fetal platelets (see Table 511.2 ). Neonatal thrombocytopenia often occurs in association with congenital viral infections, especially rubella, cytomegalovirus, protozoal infection (e.g., toxoplasmosis), and syphilis, and perinatal bacterial infections, especially those caused by gram-negative bacilli. Thrombocytopenia associated with DIC may be responsible for severe spontaneous bleeding. The constellation of marked thrombocytopenia and abnormal abdominal findings is common in necrotizing enterocolitis and other causes of necrotic bowel. Thrombocytopenia in an ill child requires a prompt search for viral and bacterial pathogens.

Antibody-mediated thrombocytopenia in the newborn occurs because of transplacental transfer of maternal antibodies directed against fetal platelets. Neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenic purpura (NATP) is caused by the development of maternal antibodies against antigens present on fetal platelets that are shared with the father and recognized as foreign by the maternal immune system. This is the platelet equivalent of Rh disease of the newborn . The incidence of NATP is 1 in 4,000-5,000 live births. The clinical manifestations of NATP are those of an apparently well child who, within the 1st few days after delivery, has generalized petechiae and purpura. Laboratory studies show a normal maternal platelet count but moderate to severe thrombocytopenia in the newborn. Detailed review of the history should show no evidence of maternal thrombocytopenia. Up to 30% of infants with severe NATP may have ICH, either prenatally or in the perinatal period. Unlike Rh disease, first pregnancies may be severely affected. Subsequent pregnancies are often more severely affected than the first.

The diagnosis of NATP is made by checking for the presence of maternal alloantibodies directed against the father's platelets. Specific studies can be done to identify the target alloantigen. The most common cause is incompatibility for the platelet alloantigen HPA-1a. Specific DNA sequence polymorphisms have been identified that permit informative prenatal testing to identify at-risk pregnancies. The differential diagnosis of NATP includes transplacental transfer of maternal antiplatelet autoantibodies (maternal ITP), and, more commonly, viral or bacterial infection.

Treatment of NATP requires the administration of IVIG prenatally to the mother. Therapy usually begins in the second trimester and is continued throughout the pregnancy. Fetal platelet count can be monitored by percutaneous umbilical blood sampling. Delivery should be performed by cesarean section. After delivery, if severe thrombocytopenia persists, transfusion of 1 unit of platelets that share the maternal alloantigens (e.g., washed maternal platelets) will cause a rise in platelet counts to provide effective hemostasis. However, a random donor platelet transfusion is more likely to be readily available. Some centers have units available that may lack the antigens most often involved. After there has been one affected child, genetic counseling is critical to inform the parents of the high risk of thrombocytopenia in subsequent pregnancies.

Children born to mothers with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (maternal ITP) appear to have a lower risk of serious hemorrhage than infants born with NATP, although severe thrombocytopenia may occur. The mother's preexisting platelet count may have some predictive value in that severe maternal thrombocytopenia before delivery appears to predict a higher risk of fetal thrombocytopenia. In mothers who have had splenectomy for ITP, the maternal platelet count may be normal and is not predictive of fetal thrombocytopenia.

Treatment includes prenatal administration of corticosteroids to the mother and IVIG and sometimes corticosteroids to the infant after delivery. Thrombocytopenia in an infant, whether a result of NATP or maternal ITP, usually resolves within 2-4 mo after delivery. The period of highest risk is the immediate perinatal period.

Two syndromes of congenital failure of platelet production often present in the newborn period. In CAMT the newborn manifests petechiae and purpura shortly after birth. Findings on physical examination are otherwise normal. Megakaryocytes are absent from the bone marrow. This syndrome is caused by a mutation in the megakaryocyte TPO receptor that is essential for development of all hematopoietic cell lines. Pancytopenia eventually develops, and HSCT is curative. TAR syndrome consists of thrombocytopenia that presents in early infancy, with bilateral radial anomalies of variable severity, ranging from mild changes to marked limb shortening. It frequently remits over the 1st few yr of life (see Chapter 511.8 and Fig. 511.4 ).

Bibliography

Curtis BR. Recent progress in understanding the pathogenesis of fetal and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia. Br J Haematol . 2015;171:671–682.

Peterson JA, McFarland JG, Curtis BR, et al. Neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia: pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Br J Haematol . 2013;161(1):3–14.

Thrombocytopenia From Acquired Disorders Causing Decreased Production

J. Paul Scott, Veronica H. Flood

Disorders of the bone marrow that inhibit megakaryopoiesis usually affect RBC and WBC production. Infiltrative disorders, including malignancies, such as acute lymphocytic leukemia, histiocytosis, lymphomas, and storage disease, usually cause either abnormalities on physical examination (lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, or masses) or abnormalities of the WBC count, or anemia. Aplastic processes may present as isolated thrombocytopenia, although there are usually clues on the CBC (leukopenia, neutropenia, anemia, or macrocytosis). Children with constitutional aplastic anemia (Fanconi anemia) often (but not always) have abnormalities on examination, including radial anomalies, other skeletal anomalies, short stature, microcephaly, and hyperpigmentation. Bone marrow examination should be performed when thrombocytopenia is associated with abnormalities found on physical examination or on examination of the other blood cell lines.

Platelet Function Disorders

J. Paul Scott, Veronica H. Flood

There is no simple and reliable test to screen for abnormal platelet function. Bleeding time and the platelet function analyzer (PFA-100) have been used in the past, but neither has sufficient sensitivity or specificity to rule in or rule out a platelet defect. Bleeding time measures the interaction of platelets with the blood vessel wall and thus is affected by both platelet count and platelet function. The predictive value of bleeding time is problematic because bleeding time is dependent on a number of other factors, including the technician's skill and the patient's cooperation, often a challenge in the infant or young child. The PFA-100 measures platelet adhesion and aggregation in whole blood at high shear when the blood is exposed to either collagen-epinephrine or collagen-ADP. Results are reported as the closure time in seconds. The use of the PFA-100 as a screening test remains controversial and, like the bleeding time, lacks specificity. For patients with a positive history of bleeding suggestive of von Willebrand disease or platelet dysfunction, specific VWF testing and platelet function studies should be done, irrespective of the results of the bleeding time or PFA-100.

Platelet function in the clinical laboratory is measured using platelet aggregometry. In the aggregometer, agonists, such as collagen, ADP, ristocetin, epinephrine, arachidonic acid, and thrombin (or the thrombin receptor peptide), are added to platelet-rich plasma, and the clumping of platelets over time is measured by an automated machine. At the same time, other instruments measure the release of granular contents, such as ATP, from the platelets after activation. The ability of platelets to aggregate and their metabolic activity can be assessed simultaneously. When a patient is being evaluated for possible platelet dysfunction, it is critically important to exclude the presence of other exogenous agents and to study the patient, if possible, off all medications for 2 wk. Further evaluation using flow cytometric analysis or molecular testing is often necessary to make a more definitive diagnosis.

Acquired Disorders of Platelet Function

J. Paul Scott, Veronica H. Flood

A number of systemic illnesses are associated with platelet dysfunction, most frequently liver disease, kidney disease (uremia), and disorders that trigger increased amounts of fibrin degradation products. These disorders frequently cause prolonged bleeding time and are often associated with other abnormalities of the coagulation mechanism. The most important element of management is to treat the primary illness. If treatment of the primary process is not feasible, infusions of desmopressin have been helpful in augmenting hemostasis and correcting bleeding time. In some patients, transfusions of platelets and cryoprecipitate have also been helpful in improving hemostasis.

Many drugs alter platelet function. The most common drug in adults that alters platelet function is acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin ). Aspirin irreversibly acetylates the enzyme cyclooxygenase, which is critical in the formation of thromboxane A2 . Aspirin usually causes moderate platelet dysfunction that becomes more prominent if there is another abnormality of the hemostatic mechanism. In children, common drugs that affect platelet function include other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), valproic acid, and high-dose penicillin. Specific agents to inhibit platelet function therapeutically include those that block the platelet ADP receptor (clopidogrel) and αIIb-β3 receptor antagonists, as well as aspirin.

Congenital Abnormalities of Platelet Function

J. Paul Scott, Veronica H. Flood

Severe platelet function defects usually present with petechiae and purpura shortly after birth, especially after vaginal delivery. Defects in the platelet GPIb complex (the VWF receptor) or the αIIb-β3 complex (the fibrinogen receptor) cause severe congenital platelet dysfunction. Although laboratory tests of platelet function are available, molecular characterization by genetic testing is rapidly progressing for platelet disorders.

Bernard-Soulier syndrome , a severe congenital platelet function disorder, is caused by absence or severe deficiency of the VWF receptor on the platelet membrane. This syndrome is characterized by thrombocytopenia, with giant platelets and greatly prolonged bleeding time (>20 min) or PFA-100 closure time. Patients may have significant mucocutaneous and gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. Platelet aggregation tests show absent ristocetin-induced platelet aggregation but normal aggregation to all other agonists. Ristocetin induces the binding of VWF to platelets and agglutinates platelets. Results of studies of VWF are normal. The GPIb complex interacts with the platelet cytoskeleton; a defect in this interaction is believed to be the cause of the large platelet size. Bernard-Soulier syndrome is inherited as an autosomal recessive disorder. Causative genetic mutations are usually identified in the genes forming the GPIb complex of glycoproteins Ibα, Ibβ, V, and IX.

Glanzmann thrombasthenia is a congenital disorder associated with severe platelet dysfunction that yields prolonged bleeding time and a normal platelet count. Platelets have normal size and morphologic features on the peripheral blood smear, and closure times for PFA-100 or bleeding time are extremely abnormal. Aggregation studies show abnormal or absent aggregation with all agonists used except ristocetin, because ristocetin agglutinates platelets and does not require a metabolically active platelet. This disorder is caused by deficiency of the platelet fibrinogen receptor αIIb-β3 , the major integrin complex on the platelet surface that undergoes conformational changes by inside-out signaling when platelets are activated. Fibrinogen binds to this complex when the platelet is activated and causes platelets to aggregate. Glanzmann thrombasthenia is caused by identifiable mutations in the genes for αIIb or β3 and is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. For both Bernard-Soulier syndrome and Glanzmann thrombasthenia, the diagnosis is confirmed by flow cytometric analysis of the patient's platelet glycoproteins. Bleeding in Glanzmann thrombasthenia may be quite severe and is typically mucocutaneous, including epistaxis, gingival, and GI bleeding. There are reports of curative therapy using stem cell transplant.

Hereditary deficiency of platelet storage granules occurs in 2 well-characterized but rare syndromes that involve deficiency of intracytoplasmic granules. Dense body deficiency is characterized by absence of the granules that contain ADP, ATP, Ca2+ , and serotonin. This disorder is diagnosed by the finding that ATP is not released on platelet aggregation studies and ideally is characterized by electron microscopic studies. Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome (with 9 subtypes) is a dense granule deficiency caused by defects in lysosomal storage. Affected patients present with oculocutaneous albinism and hemorrhage caused by the platelet defect; some patients also develop granulomatous colitis resembling Crohn disease or pulmonary fibrosis/interstitial lung disease (Table 511.5 ). Chédiak-Higashi syndrome also presents with a dense granule defect, immune dysfunction, and albinism (see Chapter 156 ). Gray platelet syndrome is caused by the absence of platelet α granules, resulting in large platelets that are large and appear gray on Wright stain of peripheral blood. In this rare syndrome, aggregation and release are absent with most agonists other than thrombin and ristocetin. Electron microscopic studies are diagnostic. Autosomal recessive gray platelet syndrome is mapped to defects in the NBEAL2 gene, while autosomal dominant disease is associated with a mutation in GFI1B . Quebec platelet syndrome is caused by degradation of platelet α granules caused by defects in PLAU , a urokinase-type plasminogen activator. Treatment usually involves antifibrinolytic therapy.

Table 511.5

Comparison of 9 Types of Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oculocutaneous albinism | Variable, mild-moderate: brown to white hair | Severe: lack of hair and iris pigment | Mild-moderate: light skin pigment | Severe: blonde hair, gray iris | Variable: light-brown hair, brown iris | Variable: iris heterochromia | Variable | Variable: tan skin, silver hair, brown iris | Pale skin, silver-blonde hair, pale-blue iris |

| Platelet defect/bruising | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Granulomatous colitis | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | − |

| Pulmonary fibrosis/ILD | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Other symptoms |

Neutropenia Failure to thrive Hypothyroidism CAH |

Depression | High cholesterol | Cutaneous infections |

+ , Present; −, absent; CAH, congenital adrenal hyperplasia; ILD, interstitial lung disease.

Other Hereditary Disorders of Platelet Function

Abnormalities in the pathways of platelet signaling/activation and release of granular contents cause a heterogeneous group of platelet function defects that are usually manifested as increased bruising, epistaxis, and menorrhagia. Symptoms may be subtle and are often made more obvious by high-risk surgery, such as tonsillectomy or adenoidectomy, or by administration of NSAIDs. In the laboratory, bleeding time is variable, and closure time as measured by the PFA-100 is frequently, but not always, prolonged. Platelet aggregation studies show deficient aggregation with 1 or 2 agonists and/or abnormal release of granular contents.

The formation of thromboxane from arachidonic acid (AA) after the activation of phospholipase is critical to normal platelet function. Deficiency or dysfunction of enzymes, such as cyclooxygenase and thromboxane synthase, which metabolize AA, causes abnormal platelet function. In the aggregometer, platelets from such patients do not aggregate in response to AA.

The most common platelet function defects are those characterized by variable bleeding time/PFA closure times and abnormal aggregation with 1 or 2 agonists, usually ADP and/or collagen. Some of these individuals have only decreased release of ATP from intracytoplasmic granules; the significance of this finding is debated.

Treatment of Patients With Platelet Dysfunction

Successful treatment depends on the severity of both the diagnosis and the hemorrhagic event. In all but severe platelet function defects, desmopressin, 0.3 µg/kg intravenously, may be used for mild to moderate bleeding episodes. In addition to its effect on stimulating levels of VWF and factor VIII, desmopressin corrects bleeding time and augments hemostasis in many individuals with mild to moderate platelet function defects. Antifibrinolytic therapy may be useful for mucosal bleeds. For individuals with Bernard-Soulier syndrome or Glanzmann thrombasthenia, platelet transfusions of 0.5-1 unit single donor platelets correct the defect in hemostasis and may be lifesaving. Rarely, antibodies develop to the deficient platelet protein, rendering the patient refractory to the transfused platelets. In such patients, the off-label use of recombinant factor VIIa has been effective, and this treatment is undergoing clinical trials. In both conditions, HSCT has been curative.

Bibliography

Blavignac J, Bunimov N, Rivard GE, Hayward CP. Quebec platelet disorder: update on pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Thromb Hemost . 2011;37:713–720.

Gunay-Aygun M, Huizing M, Gahl WA. Molecular defects that affect platelet dense granules. Semin Thromb Hemost . 2004;30(5):537–547.

Gunay-Aygun M, Falik-Zaccai TC, Vilboux T, et al. NBEAL2 is mutated in gray platelet syndrome and is required for biogenesis of platelet α-granules. Nat Genet . 2011;43:732–734.

Hinckley J, Di Paola J. Genetic basis of congenital platelet disorders. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program . 2014;2014:337–342.

Lambert MP, Poncz M. Inherited platelet disorders. Orkin SH, Fisher DE, Ginsberg D, et al. Nathan and Oski's hematology of infancy and childhood . ed 8. Saunders Elsevier: Philadelphia; 2015:1010–1027.

Lambert MP. Update on the inherited platelet disorders. Curr Opin Hematol . 2015;22:460–466.

Loredana Asztalos M, Schafernak KT, Gray J, et al. Hermansky-pudlak syndrome: report of two patients with updated genetic classification and management recommendations. Pediatr Dermatol . 2017;34(6):638–646.

Monteferrario D, Bolar NA, Marneth AE, et al. A dominant-negative GFI1B mutation in the gray platelet syndrome. N Engl J Med . 2014;370(3):245–252.

Nurden AT, Nurden P. Congenital platelet disorders and understanding of platelet function. Br J Haematol . 2014;165:165–178.

Quiroga T, Mezzano D. Is my patient a bleeder? A diagnostic framework for mild bleeding disorders. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program . 2012;2012:466–474.

Seward SL Jr, Gahl WA. Hermansky-pudlak syndrome: health care throughout life. Pediatrics . 2013;132:153–160.

Disorders of the Blood Vessels

J. Paul Scott, Veronica H. Flood

Disorders of the vessel walls or supporting structures mimic the findings of a bleeding disorder, although coagulation studies are usually normal. The findings of petechiae and purpuric lesions in such patients are often attributable to an underlying vasculitis or vasculopathy. Skin biopsy can be particularly helpful in elucidating the type of vascular pathology.

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

See Chapter 192.1 .

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

See Chapter 679 .

Other Acquired Disorders

Scurvy, chronic corticosteroid therapy, and severe malnutrition are associated with “weakening” of the collagen matrix that supports the blood vessels. Therefore, these factors are associated with easy bruising, and particularly in the case of scurvy, bleeding gums and loosening of the teeth. Lesions of the skin that initially appear to be petechiae and purpura may be seen in vasculitic syndromes, such as SLE.

Bibliography

Amos LE, Carpenter SL, Hoeltzel MF. Lost at sea in search of a diagnosis: a case of unexplained bleeding. Pediatr Blood Cancer . 2016;63:1305–1306.

Hickey SE, Varga EA, Kerlin B. Epidemiology of bleeding symptoms and hypermobile Ehlers-danlos syndrome in paediatrics. Haemophilia . 2016;22:e490–e493.