and

and  allele combinations on the cognitive abilities of Inductive Reasoning and Verbal Memory with a trend toward excess decline in Perceptual Speed. The

allele combinations on the cognitive abilities of Inductive Reasoning and Verbal Memory with a trend toward excess decline in Perceptual Speed. The  allele combination, moreover, showed less-than-average decline on these abilities.

allele combination, moreover, showed less-than-average decline on these abilities.The reader has accompanied me through the highlights of a scientific journey, now covering over 50 years, one that I have pursued with the help and support of many colleagues and students. The focus of this journey throughout was to gain a clearer understanding of the progress of adult development of the cognitive abilities and the many influences that make for such great individual differences in life trajectories. What now remains is to attempt a succinct statement of what I think can now be concluded from these studies (see also Schaie 2005a; Schaie & Willis, 2010; Schaie & Zanjani, 2006, 2011). I begin by reviewing what we have learned in the context of the five questions regarding the life course of intellectual competence that I raised in the introductory chapter. I then summarize the conclusions reached from our efforts at intervening in the normal course of adult cognitive development, as well as the findings from our efforts to learn more about adult cognition in a developmental behavior, genetic, and/or family context. I then discuss findings from our extensions into identifying the genetic and environmental influences that shape adult intellectual development. In that context, I return to the heuristic model I started with in chapter 1 and suggest where our concerns must next turn. Finally, I provide information on how to access certain limited data sets from the Seattle Longitudinal Study (SLS) that I am making available for use by qualified researchers and college teachers for secondary analyses or instructional purposes.

Although the development of intellectual competence in childhood and adolescence follows a rather uniform path, with new stages of competence and differentiation of functioning occurring within a relatively narrow band with respect to age, the same cannot be said for the life course of adult intelligence. And, of course, in contrast to the major external criterion in early life—the child’s ability to master the educational and socialization systems of our public and private schools—adult intellectual competence can be referenced to an almost infinite multiplicity of outcome variables.

Although I have tried to address many of these issues with the studies described in this volume, I have nevertheless maintained a relatively narrow focus, limited to a number of basic questions assessed in considerable depth. Hence, there are many questions we could have asked our study participants had we been satisfied with narrower age ranges and smaller samples, but that our strategies involving a large data set placed beyond our reach. Unfortunately, one cannot go backward in a longitudinal study to expand one’s inquiry, although one can always add new variables or ask questions in more sophisticated ways as a study progresses. This is what I believe we have done and, building on our rich data set, is what we shall continue to do to be able to answer new questions that will arise as time passes. Of course, one can use statistical approaches that allow estimation of variables that were not directly observed in the past, leading to the interesting theme of postdiction. Here, then, are my conclusions, as they seem appropriate at the present stage of our inquiry.

The answer to this question remains quite unambiguous: Neither at the level of analysis of the tests actually given nor at the level of the inferred latent ability constructs do we find uniform patterns of developmental change across the entire ability spectrum. I continue therefore to warn those who would like to assess change in intellectual competence by means of an omnibus IQ-like measure that such an approach will not be helpful to the basic researcher or to the thoughtful clinician. I have reported some overall indices of intellectual and educational aptitude because they are of some theoretical interest, but I do not think that such global measures have practical utility in monitoring changes (or differences) in intellectual competence for individuals or groups.

At any particular time, a cross-sectional snapshot of age difference profiles for different abilities will be largely influenced by the interaction of cohort differences and age changes for any given ability. My work in the 1950s began with the observation that there were differences in the age difference patterns for the five abilities measured in our core battery. However, only by observing longitudinal data averaged over multiple cohorts can one reach definitive conclusions about whether the nature of these differences is part of a developmental process of change in adulthood that will be observed whenever the perturbations of time and place are removed. Any single ability measure, moreover, may be unduly influenced by the form and speededness characteristics of the particular test. More stable conclusions are therefore likely to be based on ability profiles that compare estimates of the latent ability constructs. The following conclusions are based on the data presented in chapter 5.

From the extensive data on the original core battery, I conclude that Verbal Meaning, Space, and Reasoning attain a peak plateau in midlife, from the 40s to the early 60s, whereas Number and Word Fluency peak earlier and show very modest decline beginning in the 50s. In contrast to our earlier conclusions, it now seems apparent on the basis of larger samples that the steepness of late-life decline is greatest for Number and least for the measure of Inductive Reasoning ability. Verbal Meaning (recognition vocabulary) declines last but also shows steeper decline than the other abilities from the 70s to the 80s. These findings are observed whether the large number of observations of individuals followed over 7 years are aggregated or whether we consider the smaller data sets for those individuals who were followed over 14, 21, 28, 35, or 42 years.

For the more limited data on the latent construct estimates (obtained only in the fifth through eighth study cycles), it appears that peak ages of performance are still shifting, and that we now see these peaks occurring in the 50s for Inductive Reasoning and Spatial Orientation and in the 60s for Verbal Ability and Verbal Memory. By contrast, Perceptual Speed peaks in the 20s and Numeric Ability in the late 30s. Even by the late 80s, declines for Verbal Ability and Inductive Reasoning are modest, but they are severe in very old age for Perceptual Speed and Numeric Ability, with Spatial Orientation and Verbal Memory in between.

Again, I must caution that these are average patterns of age change profiles. Individual profiles depend to a large extent on individual patterns of use and disuse and on the presence or absence of neuropathology. Indeed, virtually every possible permutation of individual profiles has been observed in our study (see Schaie, 1989a, 1989b).

For some ability markers, significant but extremely modest average changes have been observed in the 50s. Nevertheless, I continue to maintain that individual decline prior to 60 years of age is almost inevitably a symptom or precursor of pathological age changes. On the other hand, it is clear that by the mid-70s significant average decrement can be observed for all abilities, and that by the 80s, average decrement is severe except for Verbal Ability.

From the largest longitudinal data set, the aggregated changes over 7 years in the core battery, I conclude that statistically significant decrement occurs for Number and Word Fluency by age 60 years and for Space and Reasoning by age 67 years, but for Verbal Meaning only by 81 years of age. For the composite indices, average statistically significant decrement is first observed at age 60 years for the Index of Intellectual Ability and at age 67 years for the Index of Educational Aptitude.

At the latent construct level, statistically significant decrement is first observed by age 60 years for Spatial Ability, Numeric Ability, and Perceptual Speed; by age 67 years for Inductive Reasoning; and by age 74 years for Verbal Ability and Verbal Memory.

The average magnitude of age-related decrements during the 7-year period when they first become statistically significant is quite small, but it becomes increasingly larger as the 80s are reached. The difference in performance for the core battery between age 25 years and the age at which the first decrement is observed is less than 0.3 SD. However, by 88 years of age, that difference amounts to 0.75 SD for Reasoning; approximately 1 SD for Verbal Meaning, Space, and Word Fluency; and as much as 1.5 SD for Number. For the latent construct measures, initial declines are even smaller (between 0.10 and 0.25 SD). The cumulative change from 25 to 88 years of age differs widely by ability domain. Because of gains in midlife, it is virtually zero for Verbal Ability; ranges from 0.6 to 0.8 SD for Inductive Reasoning, Verbal Memory, and Spatial Orientation; and amounts to approximately 2 SD for Numeric Ability and Perceptual Speed.

From these data, I conclude that it is during the period of the late 60s and 70s that many people begin to experience noticeable ability declines. Even so, it is not until the 80s are reached that the average older adult will fall below the middle range of performance for young adults. There are some occupations for which speed of performance is important, but because broad individual differences in the speededness of behavior exist, even here there is substantial overlap in the performance of young and old workers until the 80s are reached. This conclusion is reached even independent of the possibility that compensatory effects of experience in many skilled trades and professions may lessen the effect of age declines in the basic cognitive skills. Hence, it turns out that for decisions relating to the retention of individuals in the workforce, chronological age is not a useful criterion for groups and certainly not for individuals. This conclusion has, of course, been the rationale for largely abandoning mandatory retirement in the United States.

Throughout our studies, I have been cognizant not only of the fact of individual aging, but also of the fact that there have been profound changes in environmental support and societal context that must be part of shaping individual development. I have tried to document the impact of these changes on intellectual development by charting cohort (generational) differences in the intellectual performance measures. These studies have clearly demonstrated that there are substantial generational trends in intellectual performance. As documented in chapter 6, these trends amount to as much as 1.5 SD across the 70-year cohort span that we have investigated.

For the core battery, the form of these generational trends is positive for Verbal Meaning, Space, and Reasoning, but it is concave for Number (with peak performance for the 1924 cohort and decline thereafter) and is convex for Word Fluency (with lowest performance for the 1931 cohort and return to the 1889 baseline thereafter).

In the case of the latent construct estimates, equally substantial positive cohort gradients were observed for Inductive Reasoning, Perception, Spatial Orientation, and Verbal Memory. However, at the factor level, the cohort gradient for Verbal Ability takes a concave form, presumably because the additional markers of this construct are less speeded than our original single measure. Interestingly, decline is observed here for the baby boomer cohorts, particularly the trailing edge of that group. Numeric Ability at the latent construct level peaks with the 1917 cohort and shows a negative trend until the 1959 cohort, with some modest gain for the post–baby boomers.

An understanding of these cohort differences is important to account for the discrepancy between the longitudinal (within-participant) age changes and the cross-sectional (between-group) age differences reported in chapter 4. In general, I conclude that cross-sectional findings will overestimate within-individual declines whenever there are positive cohort gradients and will underestimate decline in the presence of negative cohort gradients. Curvilinear cohort gradients will lead to temporary dislocations of age difference patterns and will over- or underestimate intraindividual age changes, depending on the direction of differences over a particular time period.

Because of these cohort effects, our most recent cross-sectional data suggest much steeper declines on Verbal Meaning, Space, and Reasoning than are found in the longitudinal data and show far less decline on Number (see figure 4.4). Similar findings also obtain for the latent construct measures (see figure 4.7). The slowing of the cohort difference trend suggests that, in the next 20 or 30 years, concurrently measured age differences will become substantially smaller over that age range for which there is little or no within-participant decline. This is fortunate because there is a need to retain people to higher ages in the labor force because of the demographic reality of the aging of the baby boomers. Stereotypes about age decline will obviously be reinforced less in the absence of the dramatic shifts in ability base levels that were observed for cohorts entering adulthood in the first half of the 20th century.

Throughout this volume I have stressed the vast individual differences in intellectual change across adulthood. Some individuals, either because of the early onset of neuropathology or the experience of particularly unfavorable environments, begin to decline in their 40s, whereas a favored few maintain a full level of functioning into very advanced age.

Not all individuals decline in lockstep. Indeed, although linear or quadratic forms of decline may best describe the average aging of large groups, individual decline appears to occur far more frequently in a stairstep fashion. Individuals will have unfavorable experiences to which they respond with a modest decline in cognitive functioning but then tend to stabilize for some time, perhaps repeating this pattern several times prior to their demise. To be sure, the sequence of decline of abilities is not uniform across individuals but may depend in any one individual on the circumstances of use and disuse of particular skills. Thus, in actuarial studies of our core battery, we have observed that virtually all individuals had significantly declined in one ability by age 60 years, but that virtually no one had declined on all five abilities even by 88 years of age.

Certainly, genetic endowment will account for a substantial portion of individual differences (see chapter 16 for circumstantial evidence of heritability of adult intelligence). Nevertheless, there are many other important sources of individual differences in intellectual aging that have been implicated in our studies.

To begin with, the onset of intellectual decline seems markedly affected by the presence or absence of several chronic diseases. As discussed in chapter 10, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, neoplasms, and arthritis are all involved as risk factors for the occurrence of cognitive decline, as is a low level of overall health. On the other hand, high levels of cognitive functioning seem to be associated with survival after malignancies and late onset of cardiovascular disease and arthritis. Those persons who function at high cognitive levels are also more likely to seek earlier and more competent medical intervention in the disabling conditions of late life. They also are more likely to comply effectively with preventive and ameliorative regimens that tend to stabilize their physiological infrastructure. Perhaps even more important, they are less likely to engage in high-risk lifestyles, and they will respond more readily to professional advice that maximizes their chances for survival and reduction of morbidity. On the other hand, there does not seem to be a high relation between cognitive competence and systematic adoption of effective health behaviors. However, the more able individuals tend to engage in more effective medication use.

My interest next turned to environmental circumstances that might account for individual differences in cognitive aging. Early candidates for investigation were all those aspects of the environment that are likely to enhance intellectual stimulation (see Schaie & Gribbin, 1975; Schaie & O’Hanlon, 1990).

From the data presented in chapter 12, I conclude that the onset of intellectual decline is often postponed for individuals who live in favorable environmental circumstances, as would be the case for those persons characterized by a high socioeconomic status. These circumstances include above-average education, histories of occupational pursuits that involve high complexity and low routine, and the maintenance of intact families. Likewise, risk of cognitive decline is lower for persons with substantial involvement in activities typically available in complex and intellectually stimulating environments. Such activities include extensive reading, travel, attendance at cultural events, pursuit of continuing education activities, and participation in clubs and professional associations.

It is not surprising that intact families, our most important individual support system, reduce risk of cognitive decline. What was less obvious is the finding that cognitive decline is also less severe for those married to a spouse with high cognitive status. Our studies of cognitive similarity in married couples suggest that the lower-functioning spouse at the beginning of a marriage tends to maintain or increase his or her level vis-à-vis the higher-functioning spouse (see chapter 15).

From the very beginning of our study, we have pursued the question of whether the cognitive style of rigidity-flexibility might be associated with differential intellectual aging. I now conclude that an individual’s self-report of a flexible personality style at midlife and flexible performance on objective measures of motor-cognitive perseveration tasks do indeed reduce the risk of cognitive decline (see chapter 9). The implication of these findings is that individuals who find themselves having developed rigid response patterns in midlife would be well advised to take advantage of psychological therapeutic interventions that could lead to a more flexible response when it is needed to cope with the vicissitudes of advanced age.

Aging effects on many cognitive abilities tend to be confounded with the perceptual and response speed required to process the tasks used to measure these abilities. Thus, individuals who remain at high levels of perceptual speed are also at an advantage with respect to the maintenance of such other abilities.

Finally, those individuals who rate themselves as satisfied with their life’s accomplishments in midlife or early old age seem to be at an advantage compared with those dissatisfied with their lifetime accomplishments. Some individuals tend to deny the inescapable fact that some cognitive losses will occur with advancing age in almost everyone and may therefore avoid constructive lifestyle modifications while they are still feasible. People who overestimate their cognitive losses are frequently those who are still functioning well. But excessive pessimism about one’s rate of aging can also result in self-fulfilling prophecies if the consequence of such attitudes is a reduction of their active participation in life (see chapter 16).

I have used event history methods to develop life tables for the occurrence of decline events on the five single-ability markers in the core battery, and I developed a calculus that allows estimation of the most probable age by which an individual can expect to experience decline on each of these abilities (Schaie, 1989a). The most highly weighted variables in this calculus that predict earlier-than-average decline were found to be a significant decrease in flexibility during the preceding 7-year period, low educational level, male gender, and low satisfaction with success in life (see chapter 19).

Once adult intellectual development has been described and a number of antecedents of individual differences have been identified, it then becomes useful to think about ways in which normal intellectual aging might be slowed or reversed.

In conjunction with Sherry Willis, who analyzed these issues and developed training programs that could be applied to our study samples, we began to initiate a series of cognitive interventions. In contrast to training young children, for whom it can be assumed that new skills are conveyed, older adults are likely to have access to the skills being trained but through disuse have lost their proficiency. Longitudinal studies are therefore particularly useful in distinguishing individuals who have declined from those who have remained stable. In the former, training should result in remediation of loss; in the latter, we are dealing with the enhancement of previous levels of functioning, perhaps compensating for the cohort-based disadvantage of older persons.

Results from our cognitive interventions (chapter 7) allow the conclusion that cognitive decline in old age is, for many older persons, likely to be a function of disuse rather than of the deterioration of the physiological or neural substrates of cognitive behavior. In the initial studies, a brief 5-hour training program succeeded in improving the performance of about two thirds of the participants on the abilities of Spatial Orientation and Inductive Reasoning.

The average training gain amounted to roughly 0.5 SD. Even more dramatically, of those for whom significant decrement could be documented over a 14-year period, roughly 40% were returned to the level at which they had functioned when first studied. The analyses of structural relationships among the ability measures prior to and after training further allow the conclusion that training did not result in qualitative changes in ability structures and is thus highly specific to the targeted abilities.

The literature is replete with cognitive interventions that show significant pre–postintervention gains but often also report diminution of training effects after brief time intervals. Our follow-up of cognitive training over 7- and 14-year periods (including further booster training) has demonstrated that those participants who showed significant decline at initial training do remain at a substantial advantage over untrained comparison groups. Long-term effects for those who had remained stable at initial training differed by ability. Significant effects were shown to prevail on the intervention for Inductive Reasoning, but not on the Spatial Orientation training. Finally, replication of initial training with new samples confirmed the magnitudes of the training effects obtained in the initial study.

Some might ask how these interventions on laboratory tasks relate to real-life issues. Clearly, the showing of substantial relationships between performance on psychometric ability tests and the measure of practical intelligence or everyday problem solving suggests that these training interventions may be quite useful in a broad sense. The cost of institutionalization for individuals who are only marginally incompetent to live independently because of relatively low levels of intellectual competence is high. Modest educational interventions similar to those described in this volume, on the other hand, are quite inexpensive. As a consequence, some of the interventions developed in the course of our study have been included in a large-scale field trial to see whether they can raise competencies sufficiently to keep many elders independent for a longer period as well as to enhance the quality of their lives.

The SLS has not only provided empirical data but has also been a vehicle for introducing methodological innovations, as well as introducing to developmental psychology methods common in other disciplines but only rarely used in psychology. These contributions are briefly summarized here.

The conversion of the SLS from a single-occasion cross-sectional study to a multicohort longitudinal study was accompanied by the introduction of the age-period-cohort model into psychological developmental research (Schaie, 1965). This was followed by developing the distinction between cross-sectional and longitudinal sequences and the concept of following the same individuals over time or collecting successive random samples from the same cohorts (Baltes & Schaie, 1968). Early on, methodological studies were conducted to provide examples of how to address the issue of sampling with or without replacement and the role of monetary incentives in recruiting study participants. Following the introduction of restricted factor analysis by Karl Jöreskog, the SLS was one of the first developmental studies to switch to a design measuring behavioral change at the latent construct level. Hence, we were also the earliest users of structural equation models to test propositions regarding factorial invariance of cognitive abilities in both cross-sectional and longitudinal data sets.

The SLS was also one of the first psychological studies to apply event history and life table methods (see chapter 19) to the study of adult development also see Schaie 2007b. Another first was the application of longitudinal designs to cognitive training paradigms, as well as the development of family similarity paradigms for adult parent–offspring and sibling dyads. Most recently, we have introduced the concept of postdiction to utilize methods of extension analysis to estimate data for previous measurement occasions in longitudinal studies by developing algorithms based on the concurrent relationship between measurement batteries, parts of which were not administered on earlier occasions.

Any extensive study eventually requires some measurement development. Measures specifically constructed for use in the SLS include both expansions of previously existing tests and the construction of new tests. The Science Research Associates Primary Mental Abilities (SRA-PMA; Thurstone & Thurstone, 1949) test was expanded, made more user friendly for adults, and named the Schaie-Thurstone Adult Mental Abilities Test (STAMAT; Schaie, 1985). The Moos Family Environment Scales (Moos & Moos, 1986) were adapted and reformatted for work across the adult life span for studying perceptions of current families as well as families of origin. A measure of cognitive styles, the Test of Behavior Rigidity (TBR: Schaie & Parham, 1975), was newly constructed to measure the dimensions of Motor-Cognitive Flexibility, Attitudinal Flexibility, and Psychomotor Speed. In addition, 13 latent personality factor scores were derived from this test. Also newly constructed were three self-report inventories: The first, the Life Complexity Inventory (LCI; Gribbin, Schaie, & Parham, 1980), includes extensive demographic information, lifestyle variables, leisure use, and complexity characteristics of the individual’s work and home environments. The second, the Health Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ, Maier, 1995), gathers information on subjective perceptions of health status, preventive behaviors, nutrition, and substance use as well as utilization of preventive health care.

The third is the PMA Retrospective Questionnaire (Schaie, Willis, & O’Hanlon, 1994), used in our studies of the congruence of objective cognitive change and its subjective perception (chapter 16). All of these instruments have been normed by age and gender, and a variety of validity and/or reliability studies have been constructed for them.

Going beyond the study of age in single individuals, we began to be interested in the effects of cognitive aging within families (chapter 15). We began these studies by tracing the impact of shared environment on similarity in intellectual functioning in married couples. Our studies provide some support for the notion of marital assortativity in mate selection by demonstrating substantial within-couple correlations. These relationships persist over time (in our study, over as long as 21 years) and, indeed, in some instances increase in the direction of the spouse who was the higher functioning at base level.

More recently, influenced by developments in the behavior genetics literature, we began to assess the adult children and siblings of our longitudinal participants. Significant adult parent–offspring similarities were observed for our total sample for all ability measures (except Perceptual Speed) and for the cognitive style measures. The magnitudes of correlation are comparable to those found between young adults and their children. However, same-gender pairs showed higher correlations on Verbal Meaning, Number, and Word Fluency; opposite-gender pairs’ higher correlations were on Spatial Orientation, Inductive Reasoning, and Motor-Cognitive Flexibility.

Our data strongly support the hypothesis that if shared environmental influences are relatively unimportant in adulthood, then similarity in parent–offspring pairs should remain reasonably constant in adulthood across time and age.

Given our interest in generational differences in ability, we asked whether level differences within families equaled or approximated differences found for similar cohort ranges in a general population sample. Comparable differences were indeed found to be the rule, but there were some exceptions. The general population estimates underestimated the advantage of the offspring cohort for Spatial Orientation and Psychomotor Speed but overestimated that advantage for Perceptual Speed.

More recently, we addressed differences in the rate of cognitive change across generations. This issue is of considerable importance as most industrialized nations are beginning to consider adjusting the age of eligibility for their old-age pension systems to compensate for the increasingly adverse ratio of workers to those not in the workforce. Such efforts must avoid simply moving from retirement for reasons of age to retirement by reason of disability. It becomes critical, therefore, to know whether age declines in ability occur at a slower rate for successive generations. Our comparison across parents and biologically related offspring for changes in the decade of the 60s has found that there is indeed a slowing of decline over this age period. Although the parents showed modest but significant decline, there was no statistically significant decline for the second generation except on the variable of Number ability.

Substantial family similarity was documented also for the adult sibling pairs. In general, parent–offspring and sibling correlations were of similar magnitude. However, after controlling for age, sibling correlations were somewhat lower than those observed for the parent–offspring pairs. Interestingly, stability of sibling correlations across time and age was not as strong as for the parent–offspring data.

When our study began, there was considerable pessimism regarding the possibility that personality variables might be able to influence the life course of intelligence. Nevertheless, I thought early on that it would be useful to collect data on the adult development of possibly cognition-relevant personality and attitudinal traits. We therefore explicitly studied the attitudinal trait of Social Responsibility, derived other personality traits and attitudes from the TBR questionnaire, and added the NEO to measure the Big Five personality factors and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale as an indicator of psychological distress or depression (chapters 12 and 13).

Longitudinal data suggest a very modest gain in Social Responsibility with age until age 74 years. Women show greater Social Responsibility than men until age 46 years, but the age gradients for both genders coincide thereafter. Only modest cohort differences were found, with the lowest Social Responsibility level shown by the 1952 cohort. Interestingly, however, there were significant secular trends, with an overall decline in self-reports of Social Responsibility from 1956 to 1977 and a significant rise thereafter.

Item factor analyses of the 75-item TBR questionnaire have resulted in a fairly parsimonious 13-factor solution. The factors identified were Affectothymia, Superego Strength, Threctia, Premsia, Untroubled Adequacy, Conservatism of Temperament, Group Dependency, Low Self-Sentiment, Honesty, Interest in Science, Inflexibility, Political Concern, and Community Involvement. Although significant cross-sectional age differences were found for all 13 personality factors, fewer significant within-individual age changes were found. Most noteworthy were modest within-individual increases with age in Superego Strength, Untroubled Adequacy, Honesty, Threctia, and Conservatism. Age-related declines were found for Affectothymia, Premsia, and Political Concern. No age trends were found for Low Self-Sentiment, Interest in Science, Inflexibility, and Community Involvement.

Our studies with the NEO resulted in findings of negative age differences for Neuroticism, Extraversion, and Openness and a positive age difference for Agreeableness. Conscientiousness did not differ significantly by age group. Estimated longitudinal age changes suggested rather different life course patterns. Here, Neuroticism and Openness showed increases until midlife, with stability thereafter; Extraversion had a concave pattern of increment until midlife, with a decrease in old age; Agreeableness showed steep age-related increments; and Conscientiousness declined until midlife, with stability thereafter. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale data for our older participants showed a trend toward modest increase in psychological distress with increasing age.

Interestingly, we can show that there are modest but significant concurrent relationships between personality trait measures and ability constructs that account for up to 20% of shared variance. Both our 13 personality factor measures and the NEO could be related to the cognitive ability constructs. The personality dimensions that showed the highest relationship with high performance on the latent cognitive ability factors were high Untroubled Adequacy, low Conservatism, and low Group Dependency from the measurement of the 13 personality factors and high scores of Openness on the NEO.

Given reasonable stability across time for our personality measures, we might argue, therefore, that prediction of future cognitive change over age would benefit from the inclusion of personality traits as predictors of distal levels of cognitive performance. At least in the SLS, it was possible to show that some of the personality-cognition relations could be found over as long as a 35-year interval.

At the inception of the SLS, not enough was known about mechanisms and prevalence of dementia in population samples to warrant including prediction of future cognitive impairment in our study design. However, advances in relevant sciences and the acquisition of complex longitudinal-sequential data have opened the possibility of seriously addressing the identification of risk for dementia utilizing cognitive data collected long before clinically noticeable symptoms of impairment become apparent.

We reported in this volume some results of our work with the apolipoprotein E (ApoE) genetic marker of dementia as it relates to cognitive decline (chapter 18). We confirmed excess decline over 7 years in persons over age 60 years who possess the  and

and  allele combinations on the cognitive abilities of Inductive Reasoning and Verbal Memory with a trend toward excess decline in Perceptual Speed. The

allele combinations on the cognitive abilities of Inductive Reasoning and Verbal Memory with a trend toward excess decline in Perceptual Speed. The  allele combination, moreover, showed less-than-average decline on these abilities.

allele combination, moreover, showed less-than-average decline on these abilities.

Studies were then considered that involved the neuropsychological assessment (with an expanded Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease [CERAD] battery) of a community-dwelling sample of older adults who were not known to suffer from clinically diagnosable cognitive impairment (chapter 20). Age differences, favoring the young-old, were found on this battery in our normal sample. Significant gender differences in favor of women were found for the Fuld Retrieval test, the Fuld Rapid Verbal Retrieval test, the Word List Recall, and the Mattis total score. Preliminary results for a 3-year follow-up assessment yielded moderate-to-good stabilities for the neuropsychology battery. The observed 3-year changes were positive for the young-old and partially positive for the old-old, but significant decrements were found for the very old subgroup.

We were able to link the measures used in clinical practice with our psychometric battery for the study of normal aging. Most measures had their primary loadings on our Verbal Memory factor. However, the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised (WAIS-R) Digit Span, Vocabulary, and Comprehension scales had their primary loadings on the Verbal Comprehension factor, and the WAIS-R Block Design loaded most prominently on the Spatial Ability factor. Several neuropsychological measures also had secondary and/or tertiary loadings on Spatial Ability, Inductive Reasoning, and Numeric Facility. We were able to use the neuropsycho-logical data to identify participants in our study who appeared to have reached early cognitive impairment or who had indications that future monitoring would identify such impairment.

Finally, we were able to develop algorithms by means of extension analyses that allow us to obtain postdicted estimates of earlier performance on permit tests of the hypothesis that it may be possible to identify those at risk for an eventual clinical diagnosis of dementia. These algorithms are based on knowledge of the concurrent relationship of neuropsychological measures with our psychometric assessment battery and applied to earlier psychometric measures. Results of these studies suggest that data from psychometric tests suitable for a normal community-dwelling population can predict high risk for dementia as long as 7 and 14 years prior to the identification of cognitive impairment by a neuropsychologist.

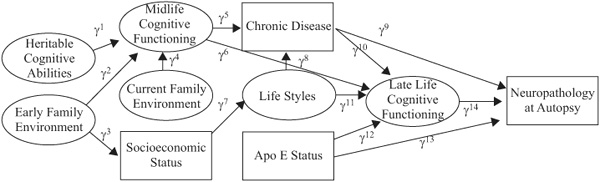

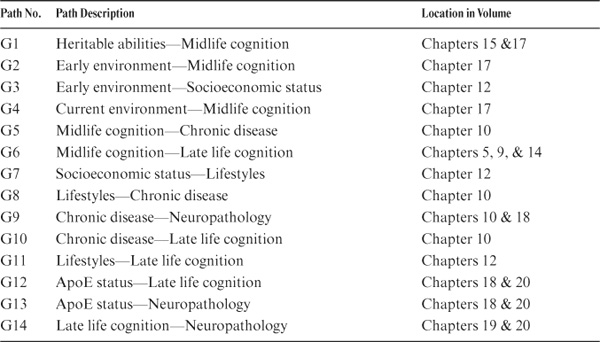

Having begun my exposition of findings from the SLS by providing a conceptual model, I now attempt to identify as clearly as possible where to find both methods and substantive data relevant to the relationships posited in that model. The model offered in chapter 1 is, of course, primarily a heuristic guide to our comprehensive research program. I reproduce it again as figure 21.1 so that the reader will be able to compare it directly with the submodels that have directly guided specific research efforts conducted as part of the SLS. However, I have numbered each of the proposed causal paths so that I can specify more conveniently where data used for estimating a given path or relevant for the understanding of a particular path may be located in this volume.

FIGURE 21.1. Seattle Longitudinal Study conceptual model with path identifications. See table 21.1 for additional information.

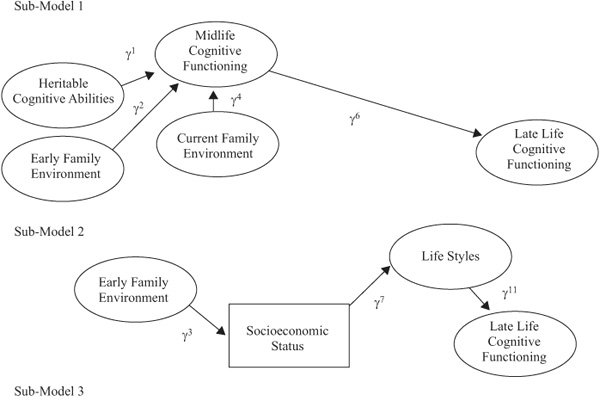

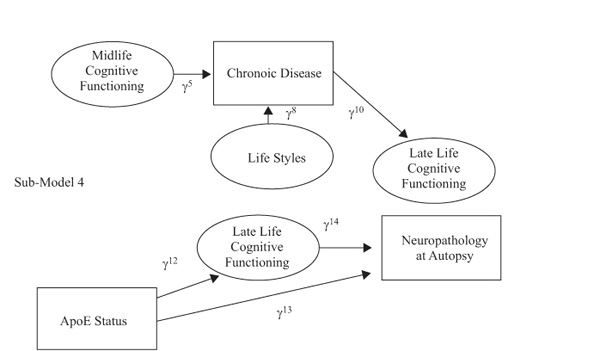

To make the relationship between the conceptual model and the empirical data more comprehensible, I have divided the overall model into four submodels (see figure 21.2). The first submodel is concerned with the heritable and contextual variables that directly affect the life course of cognitive functioning. This model not only represents the longitudinal study of cognition over the adult life course but also indicates our efforts to assess the relative impact of heritability and environmental influences.

The second submodel includes influences that originate in the early family environment that result in social status and lifestyle factors that influence late-life cognitive functioning. It represents our work on charting the individual’s microenvironment and the resultant lifestyle factors that make the difference in achieving successful aging.

FIGURE 21.2. Submodels with path identifications. See table 21.1 for additional information.

The third submodel tracks the influences of chronic disease as moderated by lifestyles and of cognitive functioning on late-life cognitive functioning. This model represents our efforts to take advantage of our collaboration with a health maintenance organization to account for the effects of chronic disease on cognitive aging.

The fourth submodel charts the relation between genetic predisposition and late-life cognitive functioning to result in the detection of neuropathology at eventual autopsy. The evidence for these paths is as yet incomplete as we are still in the process of collecting relevant data. Table 21.1 indicates the specific chapters that provide evidence for each of these paths in some detail.

Although we have learned a lot about adult intellectual development in our journey that now extends over 50 years, I am very conscious of the fact that many questions remain that can be addressed by further analyses of our database and the data currently being collected (with funding from the National Institute on Aging that currently extends through 2015). Included in these new studies will be further emphases on biological markers of aging and the relation of cognitive change to changes in brain structure and functioning, including the application of structural and functional MRI imaging approaches.

TABLE 21.1. Location of Evidence for Relationships Specified in the Conceptual Model

The questions that need to be asked next can be loosely grouped under the following topics:

1. Differences in rate of aging across generations. We report in this volume favorable data on the slowing of the rate of cognitive decline across biologically related parent–offspring dyads during the seventh decade of life. New data will hopefully permit examining this phenomenon over a 14-year period and into the eighth age decade.

2. Crosscultural generalizability of differential patterns of cognitive aging. We have previously conducted pilot studies in China that suggested both similarities and differential patterns as compared with American samples (see Dutta et al., 1989; Schaie, Nguyen, Willis, Dutta, & Yue, 2001). These studies should be replicated and extended to other cultures, including larger samples of American ethnic minorities.

3. Effects of retirement on the maintenance of cognitive functioning in old age. The cognitive effects of retirement seem to be positive for those in routine jobs, but retirement leads to lower functioning in those retiring from complex jobs (see DeFrias & Schaie, 2001; Dutta, Yue, Schaie, Willis, O’Hanlon, & Yu, 1986; Ryan, 2008). These results may well have been affected by the abandonment of mandatory retirement and therefore need to be replicated with more current data.

4. Relation of psychometric and practical intelligence. Further studies are needed to determine the predictive value of laboratory measures of cognition to functioning in the community. To do so, longitudinal data need to be acquired for objective measures of instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs).

5. Psychometric abilities and early detection of risk for dementia. The work reported in this volume is encouraging enough to suggest further work on the relation between measures used for the description of normal aging and neuropsychological measures used to detect neuropathology.

6. Brain–behavior relationships. Cognitive changes with normal aging need to be related to structural and functional changes in the brain. We need to know whether early cognitive declines in midlife represent changes in brain structure and function. We also need to know whether those individuals who gain in cognitive performance in midlife differ in brain morphology from those who remain stable or decline.

7. Neuropathology detected at postmortem. The delineation of the relationship of documented long-term behavior change to structural changes in the brain needs to be continued. Of particular interest will be individuals who retained competent behavior close to their demise even though neuropathology is identified at postmortem.

There is no way that I and my associates will ever be able to fully explore all of the implications of the rich data that we have been privileged to collect. I have therefore begun to develop a public use archive for use by qualified researchers and college teachers for secondary analyses or instructional purposes. This archive is available at http://geron.psu.edu/sls. Here I describe its content and provide instruction on how it can be accessed.

The data archive currently contains all PMA and TBR scores for the eight waves of the study, plus a limited number of demographic descriptors. The files have been stripped of any personal information and of the original identification numbers to make it impossible to identify any particular individual. Altogether, there were 4,857 participants at first occasion. Of these, 1,235 returned for a second assessment, 591 returned for a third occasion, 371 for a fourth occasion, 262 returned for a fifth occasion, and 139 participants returned six or more times. The data set consequently consists of seven cross-sectional files and eight longitudinal files.

Those interested in using the archive should access the SLS Web site at http://www.uwpsychiatry.org/sls. The following steps should be taken:

1. Select the “For Researchers” button.

2. Select “Measures” to become familiarized with the variable provided.

3. Select “Objectives.”

4. Select “SLS Datasets.”

5. Select “New User Setup.”

6. Print access application form and submit as indicated.

Approved users will then be given a time-limited password that will allow them to download data sets of interest from the University of Washington “Catalyst” file-sharing system.

A broadly conceived longitudinal study, far from becoming outdated and obsolete, can often provide the basis for new and exciting questions that could not have been formulated given the state of the art at the study’s inception. This volume provides an account of the many ways in which the original questions proliferated into an extensive program of studies of adult cognitive development and of the many influences that led to the vast individual differences in developmental trajectories. This exciting voyage of discovery has provided me with the basis for my own exciting scientific career and an opportunity to train several cohorts of successful graduate students (cf. Hertzog, 2009). As I have moved from being the contemporary of my youngest study participants to that of the older participants, it has also continued to provide encouragement for me in my continuing efforts to shed further light on the dynamics of adult development. Hence, I do not yet consider my work done, and I hope that the reader will anticipate future installments in the account of this odyssey as eagerly as I do.