With its dapper white chin and resonant honk, the Canada Goose is a familiar sight and sound on ponds and fields across North America. A few decades ago, the passage of geese in the spring and fall was a rare and celebrated occurrence. In the early 1900s, their numbers had been so reduced by hunting and disturbance that none were nesting in the eastern United States, and in most areas they were only seen migrating to or from their nesting grounds far to the north in Canada. Over the last half century, however, their numbers have increased so much that they are now considered a pest in many areas.

The Snow Goose is a long-distance migrant, nesting in the High Arctic and wintering in huge numbers in a few places in the southern U.S. True migration involves the seasonal movements of whole populations of birds, and allows them to take advantage of regions that offer a wealth of resources for only part of the year. In some species migration operates on a strict schedule (see Scarlet Tanager, this page). The migration of geese is more loosely controlled by instinct. Geese have the ability to move throughout the year whenever conditions warrant. They might cover long distances nonstop, or interrupt their movement, or even reverse direction to take advantage of feeding opportunities. Plentiful food and mild weather will permit them to move farther north, while dwindling food supplies, a snowstorm, or severe cold will prompt an immediate retreat to the south. This strategy, known as facultative migration, is a way to exploit new and temporary food sources and react to weather. Along with a warming climate, this has allowed many geese to shift their primary wintering areas far to the north in just a few decades.

With their all-white plumage, long necks, and aristocratic demeanor, swans have been admired for centuries. The Mute Swan is native to Britain and Europe, where it was associated with royalty and kept as an ornamental feature of ponds on large estates as early as the 1100s. Beginning in the mid-1800s, some were brought to the United States and released in parks. They thrived and spread, and are now common on sheltered waters from New England to the Great Lakes. Two species of swans, the Tundra Swan and the Trumpeter Swan, are native to North America. Biologists are concerned about the impact the nonnative Mute Swan is having on native waterfowl; they are extremely territorial, and once a pair settles on a pond they will chase off many other species of ducks and geese. They also eat large amounts of aquatic vegetation, and could potentially outcompete native species for food.

Muscovy Duck (top) and Mallard (bottom)

Only a few species of birds have been domesticated by humans, with two ducks—the Mallard (domesticated in Southeast Asia) and the Muscovy Duck (domesticated in Central America)—being among the most important. Shown here are just two of the countless varieties and crosses of these species that can be seen in parks and farmyards around the world. Other domesticated species of birds include two geese from Europe and Asia, the Wild Turkey from Mexico, guineafowl from Africa, the Rock Pigeon from Europe, and, of course, the chicken from Southeast Asia.

The Mallard is the most widespread and familiar wild duck in North America, found in flocks on ponds and marshes across the continent. It has been domesticated, and many domestic varieties are found in city parks and farmyards. Water birds like ducks have many adaptations for an aquatic lifestyle. One of their primary challenges is getting to the food they want, since it is usually under the water. Several related species of ducks—including the Mallard—use a technique called “tipping up,” or “dabbling.” These “dabblers” simply tip forward while swimming, stretching their neck straight down underwater to reach their desired food. This only works when food is within reach and not moving, so these species forage in shallow water and feed mainly on plants.

One of the most extravagantly adorned birds, the male Wood Duck is the product of millions of years of evolution and female choice. Having precocial young (see Canada Goose, this page), the female can manage the entire nesting and chick-rearing process alone. This means she can select a mate based only on his beauty—showy plumage and intricate displays (looks and dance moves). In the same way that plant breeders select certain flower characteristics, females can drive the evolution of these traits simply by their selection of mates. The evolutionary logic is that if she chooses a beautiful and desirable mate, it increases the chance that her offspring will be beautiful and desirable, and more likely to find mates themselves. This will maximize the spread of her genes in future generations. The process is self-perpetuating, as male offspring inherit the looks of their father, and female offspring inherit their mother’s preferences. Over millions of generations, as females continually choose males that stand out from the flock, the process can lead to strikingly beautiful birds like the Wood Duck.

One of over twenty species of diving ducks in North America, the Surf Scoter nests on freshwater lakes in the far north and winters on open ocean. Unlike dabbling ducks (see Mallard, this page) scoters forage in deep water and dive to the bottom to find clams and other shellfish. Having no teeth, they simply swallow the clams whole. The powerful muscles of the gizzard pulverize the whole clam, including the shell, into pieces small enough to pass through the digestive tract. The shell fragments act as grit and help to grind up the food, so scoters, unlike geese and other birds (see this page), do not need to swallow rocks to provide a grinding surface.

Coots swim like ducks and are about the same size, but they are unrelated. In fact, coots are related to a group of marsh birds called rails, and are distantly related to cranes (see this page). Coots differ from ducks in having lobed toes rather than webbed, as well as in bill shape. The coot’s sharp clucking and nasal whining sounds are very different from the quacks and whistles commonly heard from ducks. And their nesting habits are quite different, too; for example, adult coots provide food for the young.

Its eerie wailing cries and sleek yet primitive looks make the Common Loon a charismatic and beloved symbol of the wild and pristine lakes of the North. A nesting pair requires a lake at least one-third of a mile across, with clear water (they hunt by sight). They also need a healthy population of small fish 3 to 6 inches long, as adults consume about 20 percent of their body weight in fish each day. Acid rain, pollution, algae blooms, and silt from soil erosion can all make a lake unsuitable for nesting loons. Discarded lead fishing weights can be swallowed by loons and cause lead poisoning, which is currently the largest source of human-caused mortality in the species, but they seem to be able to overcome all of these challenges and populations are currently stable or increasing.

Grebes are water birds, generally smaller than ducks. Despite their similarity to loons, cormorants, and other water birds, recent DNA research shows that their closest relatives are flamingos! The Eared Grebe is a small species common across the West. They gather by the hundreds of thousands to feast on brine shrimp at a few alkaline lakes in the fall—Great Salt Lake in Utah and Mono Lake in California each host huge numbers. On cold, sunny mornings, the Eared Grebe sunbathes by facing away from the sun and raising its rump feathers, exposing dark underlying skin to the warm sunlight.

Puffins are in the Alcid family, a group of birds adapted to life on the ocean and coming to land only to nest in colonies on small islands or rocky sea cliffs. Alcids live in some of the coldest ocean water in the world, and spend the entire winter at sea without ever coming to land. They are the Northern Hemisphere equivalent of penguins, but their similarities are the result of convergent evolution. These two groups of birds have independently evolved similar solutions to the challenges of finding food in a frigid ocean.

Cormorants are fish-eating birds that are common around larger bodies of water worldwide. The Great Cormorant is said to be the most efficient marine predator in the world, catching more fish per unit of effort, on average, than any other animal. Cormorants have had a long association with humans, and a centuries-old practice in Asia uses captive cormorants to catch fish for their human handlers. In recent decades, a population increase of Double-crested Cormorants in the United States and Canada has brought them into conflict with human fishermen.

Two of the world’s eight species of pelicans are found in North America—the Brown Pelican, in saltwater along our coasts, and the American White Pelican, mainly in freshwater and in the West. Both are instantly recognizable by their very large size and characteristic pelican pouch. They are among our largest birds; the American White Pelican is more than two thousand times as heavy as a hummingbird. That’s equivalent to the difference between a human and a blue whale.

They may appear graceful and elegant at a distance, but up close the large size and dagger-like bill of the Great Blue Heron make it a fearsome predator. That bill is usually aimed at fish, but frogs, crayfish, mice, and even small birds are on the menu if they come within striking range. At nearly four feet tall, it is the tallest bird that most people will see. They are often seen resting or standing patiently at the water’s edge, just watching. If disturbed, the heron will fly up with a deep disgruntled croak, beating its wings slowly and deeply, and curling its neck back onto its shoulders after a few wing beats.

Egrets and herons differ only in name; they are all in the same family. Most egrets are white, and some species have very lacy plumes. The egret’s delicate feathers were the height of fashion in women’s hats in the late 1800s, and plume hunters destroyed nesting colonies and killed hundreds of thousands of birds every year to ship feathers to the major cities of the United States and Europe. By 1900, the populations of many species were dangerously low. Public outcry over the wanton killing of birds for nothing more than fashion led to the formation of the first Audubon Societies, the first laws to protect wild birds, and the establishment of the U.S. National Wildlife Refuge System. With protection, most species quickly recovered.

The Roseate Spoonbill is one of the most remarkable birds in North America. Found along the southeast coast from Texas to Georgia, their pink color and spoon-shaped bill makes them instantly recognizable. They feed by swinging their bill back and forth in muddy water, slightly open so water passes through between the upper and lower mandibles. Tiny prey like shrimp or small fish can be felt, grabbed, and swallowed. Ibises are in the same family, but with downcurved bills.

There are fifteen species of cranes in the world, and only three of them have populations that are considered secure. One of those is the Sandhill Crane, found throughout most of North America and increasing in numbers. The other native species on this continent is the Whooping Crane. Never common or widespread, the Whooping Crane was reduced to a total population of only about twenty individuals in 1941, most of those migrating between northern Canada and Texas. The nesting grounds in Canada were not discovered until 1954. Since then, with the help of dedicated work by generations of biologists, the population has slowly increased and now numbers several hundred birds in the wild.

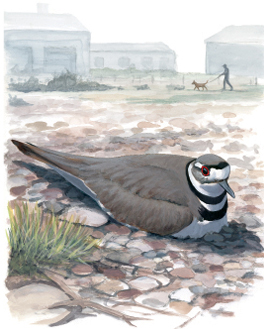

The first sign that a Killdeer has taken up residence nearby is the piercing “kill-deer” call repeated over and over from high in the air. This is the male, advertising to rivals and his mate, claiming a territory. Usually the territory is an open field with a bit of gravel—the edge of a parking lot, a gravel road, even a gravel rooftop can serve as a nesting site. Because they nest on open ground, these birds face some serious challenges in protecting their eggs and young from predators, and they have developed an impressive array of tricks and strategies to keep themselves and their eggs safe.

The Long-billed Curlew is one of the largest sandpipers in the world, and its bill is one of the longest relative to body size of any bird in the world. One might expect them to use their long bill to reach prey hidden deep in mud or burrows, but more often they do not. This species nests on dry short-grass prairie in the western U.S., where they eat mainly grasshoppers and other insects plucked out of the grass with the tip of their bill. Some spend the winter along coastal waterways, probing in mud for marine worms, fiddler crabs, and other prey. But many curlews winter in the dry grasslands of northern Mexico, where they continue to eat grasshoppers.

The Sanderling is commonly seen on wave-washed sand on both coasts. This is the sandpiper best adapted to sandy beaches, and therefore the one most often encountered by beach-going humans. They have evolved a foraging strategy that takes advantage of the food uncovered by wave action along the beach. An incoming wave rushes up the beach, stirring up the surface of the sand and sending the birds in a quick dash uphill to escape the rising water. As soon as the wave begins to recede they run downhill after it, watching for any invertebrates that have been dislodged by the movement of water and sand, and stopping to probe and to feed. A few seconds later the next wave forces them to dash uphill again. There are many other species of sandpipers, and most are found on mudflats where they can forage less frantically.

The American Woodcock is a very unusual sandpiper that lives in the woods, hunting invertebrates in the soil by smell. Unlike most other sandpipers, they are solitary and secretive. The surest way to encounter one is to go out in the spring and listen for males displaying. After sunset, male woodcocks come out of the woods into nearby grassy fields to show off for any females who are watching. From the ground they give a nasal buzz, and then launch into an impressive display. Climbing several hundred feet into the twilight sky, they circle and then drop quickly down, all the time “singing” a complex, high-pitched twitter. Most, if not all, of the sound is produced by air rushing past their narrow outer wing feathers.

Gulls may be the most versatile birds in the world. In a bird triathlon—swim, run, fly—gulls would be among the favorites to win. Other birds may be faster swimmers, faster runners, and faster fliers, but no other bird does all three so well, and this versatility allows gulls to take advantage of a very wide range of feeding opportunities. The Ring-billed Gull is a medium-size gull common across the continent near any water. It often hangs around restaurant and shopping center parking lots hoping for food. Many other species of gulls occur especially along the ocean shores.

Terns are closely related to gulls, but they are much more elegant, with very graceful flight, slender wings, and long pointed bills. Most tern species eat small fish exclusively, which they catch by hovering and then diving headfirst into the water. Most species nest in colonies and are highly migratory, traveling far south to find their preferred prey in the winter.

If you see a large hawk perched along a road or field edge anywhere in North America, it’s likely to be this species. The Red-tailed Hawk is a species in the genus Buteo—a group of large hawks with long, broad wings—and it thrives in the open woods and small fields that we create in suburbia, feeding mainly on squirrels and small rodents. One pair has even taken up residence (famously) in Central Park, in the middle of Manhattan. The evocative scream of the Red-tailed Hawk is familiar to millions of people from the soundtracks of desolate western scenes in movies and TV shows. Unfortunately, the accompanying footage usually shows a Bald Eagle or Turkey Vulture.

The hawks in the genus Accipiter specialize in hunting small birds. With long tails and relatively short, powerful wings, they are excellent fliers and can maneuver easily through tangled branches and around obstacles. Small birds sound the alarm and shelter in fear when an Accipiter shows up, and a hawk is often the reason for a sudden drop in bird feeder activity. It can be shocking to witness the capture of a small bird by one of these hawks, but it is important to remember the critical role that predators play in ecology. A recent study found that the mere suggestion of a predator causes smaller species to change their behavior, staying closer to shelter. This creates an opportunity for the prey of the smaller birds (insects, seeds, and so on) to survive in areas the birds are avoiding. Predators control the populations of their prey species, and also alter the behavior of survivors. All of this has far-reaching effects on the entire community.

The national bird of the United States was nearly extinct in the 1970s, when its population was decimated by DDT poisoning. Thankfully, with protection, the species is again widespread and fairly numerous. It’s now possible to see Bald Eagles in every state, but they still face numerous threats, including lead poisoning. Despite the fearsome appearance of their bill, eagles never use it as a weapon to attack or defend. They use their talons for that, and use their bill only to tear apart food. Bald Eagles are primarily scavengers, taking easy prey such as dead fish whenever they can, and congregating around dams and other open water in the winter. Ask at your local nature center or bird supply store—chances are there is a good eagle-viewing spot near you.

The Turkey Vulture and its close relatives the Black Vulture and the California Condor are nature’s cleanup crew. They patrol from the air to find dead animals, then drop down for a meal. Several adaptations help them do this: they have evolved the ability to ride updrafts and thermals with almost no effort so they can stay airborne for hours, a powerful sense of smell to find food sources from the air, featherless heads for easy cleanup, and a unique community of gut bacteria that would be toxic to most other animals. Vultures are often called “buzzards,” but in Britain that name is used for hawks related to the Red-tailed Hawk.

The American Kestrel is one of the smallest falcons in the world, related to the Peregrine Falcon but a dainty eater of grasshoppers and mice. Formerly more numerous, often nesting in barns, the American Kestrel has been declining for decades, and its petulant “killy killy killy” call is no longer a familiar sound. Kestrels can still be seen in open country, often perched on wires or fenceposts along roadsides or hovering over fields as they hunt for grasshoppers and mice, but few people see them regularly. Reasons for the decline are still unknown, but it may be related to the loss of farmland habitat, or the increased use of insecticides on farms and lawns, or the loss of nest sites as fewer large dead trees are left standing.

Wherever you live, chances are there is a Great Horned Owl living within a few miles. This species has proven to be very adaptable and has taken advantage of the abundance of small mammals in suburbia, essentially taking the night shift where Red-tailed Hawks hunt in the day. It is a very opportunistic hunter. On average, 90 percent of its diet is mammals, but the diet of some individuals can be up to 90 percent birds, mainly waterfowl or medium-size birds roosting in the open, also nestlings (including raptors), and even smaller owls.

The Eastern Screech-Owl (and the very similar Western Screech-Owl) are common in woodland edges across the continent. Most owls are active at night and find a sheltered and secluded spot to rest through the whole day, often using the same perch every day. This makes them especially sensitive to disturbance at their daytime roost. Their cryptic colors and ear tufts provide camouflage and usually allow them to hide, but other birds or squirrels sometimes discover a roosting owl and mob it (see this page lower left). If you find a roosting owl it is important to avoid disturbing it. Watch from a distance and don’t stay in the area long. The velvety surface and soft edges of owl feathers are not as water repellent as typical feathers, so owls tend to get wet in the rain. This could be one reason why so many seek out sheltered daytime roost sites in hollow trees or dense vegetation.

No other North American bird has such a complex history with humans. The Wild Turkey is at the same time a symbol of the wild and bountiful forests of the New World and one of the most widely domesticated birds in the world. In 1621 the Pilgrims brought domestic turkeys with them from England, and then wrote about a “great store of Wild Turkies” in Massachusetts, but by 1672—only fifty years later—it was “rare to meet with a wild turkie,” and by 1850 the species was completely gone from not only Massachusetts but much of the eastern U.S. It was more than one hundred years before the species returned, thanks to prolonged efforts by wildlife managers, the regeneration of forests, and a reduction of hunting. Wild Turkeys rebounded in the late 1900s, and are now a common sight even in suburban yards.

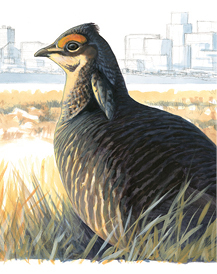

The chicken-like birds in the grouse and pheasant family have been favorites of hunters for millennia. Many species are now very rare in the wild, and a few are extinct. In North America one population is extinct—the Heath Hen (considered a subspecies of the Greater Prairie-Chicken). It was found along the Atlantic coast from Boston to Washington, D.C., the same area that the first European colonists occupied, and by the 1830s it was almost exterminated. The last surviving population was on Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, where the last individual was seen in 1932.

Quail are related to chickens, grouse, and pheasants, but classified in a separate family. Several species of quail are common in the American Southwest from Texas to California. Small groups, called “coveys,” are often seen foraging on the ground at the edge of brushy areas, or sprinting single file across roads or trails. Only one species—Northern Bobwhite—is found in the East, and it is now much less common than it was fifty years ago.

The pigeon is surely the most familiar bird in North America, and it’s not even native. Domesticated thousands of years ago in the Middle East and now completely adapted to city life, this bird is abundant, and both loved and hated, in cities worldwide. In the wild, Rock Pigeons roost and nest on cliff ledges, so adapting to the ledges of human structures like buildings and bridges was not hard for them.

Pigeons and doves are closely related. Along with the American Robin, the Mourning Dove is one of the most widespread species in North America, found in virtually every backyard from British Columbia to Arizona to Maine. Their mournful hooting call is often mistaken for an owl’s. One contributor to their success is the ability to nest almost year-round, even in northern climates. Most species in the northern states have a very limited nesting season of less than two months, but Mourning Doves stretch their nesting season to over six months, from March to October, and even longer in the South.

Several species of hummingbirds (including the Rufous Hummingbird) are common in western North America. In the East only the Ruby-throated Hummingbird is expected. Hummingbirds and flowers have evolved together, and the flowers that are pollinated by hummingbirds are often perennial, red, tubular, and without strong odor. Hummers can smell, but they find the flowers by sight and remember the locations of perennials to return to them every year. A narrow tube helps ensure that only hummingbirds can reach the nectar. Flowers also adjust their nectar content to lure hummingbirds back for repeated visits, which increases the chance of pollination.

Blue-throated Mountain-Gem and Calliope Hummingbird

The Calliope Hummingbird is found in the western mountains, while Blue-throated Mountain-gem is one of several species that range just north of the Mexican border into the southwestern states. Hummingbirds are extreme. They have the longest bill and shortest legs relative to body size, and are unable to walk or hop—every movement requires flying. This painting shows the largest hummingbird found north of Mexico and the smallest. There are larger species in South America (up to the Giant Hummingbird, which is about as heavy as a Song Sparrow) and a couple of smaller species (the smallest is the Bee Hummingbird of Cuba). The smaller species (including Rufous Hummingbird) beat their wings over seventy times a second. That adds up to over 250,000 wing beats per hour, and over a million wing beats in just four hours of flying. In a year a single bird beats its wings well over half a billion times!

The roadrunner is one of the most iconic species of the American desert Southwest. In the cuckoo family, they spend most of their time on the ground, fly only reluctantly, and eat almost anything they can catch, from beetles and lizards to snakes and birds. Contrary to the classic cartoon, they are not at war with coyotes.

The kingfisher family includes more than three hundred species, but only six species are found in the Americas. The name kingfisher originated in England, where only one species occurs. That species, and the six found in the Western Hemisphere, do eat mainly fish. The other three-hundred-plus species are found in Asia, Australia, and Africa, and most of them do not eat fish. They are found in forests and brushy areas, where they eat insects and other small animals. The well-known kookaburra is a member of the kingfisher family.

The Monk Parakeet comes from temperate South America and can survive as far north as Boston and Chicago. Many parrot species around the world are threatened with extinction. Nests are sought and raided so that the young parrots can be brought to market and sold as pets. This has a devastating impact on the overall population. Many species have escaped from captivity and now survive in the wild in cities in the southern U.S. Ironically and tragically, there are now more Red-crowned Parrots escaped from captivity and living wild in the southern U.S. than in the species’ native range in Mexico. Only one species of parrot was native to the United States—the Carolina Parakeet, now extinct.

Downy Woodpecker and Hairy Woodpecker

These two species are common in woodlands almost everywhere in the United States and Canada, and they often visit feeders, making this a frequent identification challenge for backyard birders. The appearance of the Downy Woodpecker might be evolving to match the appearance of the Hairy Woodpecker. Recent research supports the idea that a smaller species (in this case, Downy Woodpecker) can benefit when other birds mistake it for a larger species (Hairy Woodpecker). In other words, the Downy Woodpecker fools the other birds and gets a higher position in the pecking order by pretending to be a Hairy Woodpecker.

Yes, the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker is a real bird. There are four species of sapsuckers in the world, all in North America. Their name comes from a distinctive habit of drilling rows of shallow holes in trees, and returning regularly to drink the sap and to eat any insects that have been attracted. They drill two different kinds of sap wells: shallower rectangular holes and deeper, smaller, round holes. These tap into different layers of the tree tissue, which carry more or less nutritious sap at different seasons. These sap wells make the sap available to any other birds and animals in the area, and this leads ecologists to call sapsuckers a keystone species. Like the keystone at the top of an arch, removing sapsuckers from an ecological community could cause the whole system to collapse.

This crow-sized woodpecker has experienced a population surge in recent years, with the recovery of large areas of forest in many states. Still, it occurs at low density, with only about six pairs per square mile even in the best habitat, so birders are always excited to encounter one. It usually doesn’t visit bird feeders, but individual birds or family groups may learn to come for suet in some locations. No other living North American woodpecker is this large, and the bright red crest and flashing white wing patches identify it. Only the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (now presumed extinct) was larger.

The most un-woodpecker-like woodpecker, flickers are often seen hopping around on lawns or in gardens, searching for their favorite food—ants. With their odd habits and bold markings, many people never suspect flickers are woodpeckers. They are noisy in the spring and summer, giving a loud, clear keew and a long series of wik-wik-wik-wik notes. Flickers are much less common now than they were several decades ago, perhaps because there are fewer large dead trees for nesting, fewer ants, or more pesticides, but the actual cause is unknown. By excavating nesting cavities in large dead trees, flickers provide future nest sites for many other species, such as the American Kestrel. The decline of flickers may therefore influence populations of other species.

Most species of flycatchers are inconspicuous denizens of forest, swamps, and dense brush. A few species are found in the open and around buildings, and these include the phoebes. The three species of phoebes are small flycatchers that build nests on man-made structures such as porches and barns. All three have the habit of dipping their tails gently when they are perched, and all have soft whistled songs that say their name—FEE-bee—and variations.

Kingbirds are larger, bolder, and more colorful flycatchers found in wide open spaces. They are known for their fearless and aggressive defense of their territory and nest against all intruders. The kingbird is quicker and more agile in flight than larger birds, and attacks any passing hawk from above and behind, often pecking at the back of the hawk’s head as shown here. Kingbirds choose conspicuous perches in open country—fences, telephone wires, etc.—and watch for large flying insects.

The high, sharp twittering of Chimney Swifts is a common sound over eastern towns in the spring and summer, but you will never see one perched. These remarkable birds spend the entire day high in the air, and spend the night clinging to the walls inside a chimney. Before the advent of chimneys, they roosted and nested in large, hollow trees, or even on the bark of large trees protected by an overhanging limb. Exactly how they spend their winters is not known. Once they start migrating in September to their wintering grounds in South America, it’s possible that they stay in the air for the entire time, until they return to their nesting chimney the following April. Recent research has documented that some other species of swifts stay airborne, flying continuously, for up to ten months. How and when they sleep is still unknown, but a study of frigatebirds showed them flying continuously for weeks at a time, and that the time spent sleeping each day during continuous flight was only 6 percent of the daily sleep they get when they can perch. Like other birds (see Mourning Doves, this page), they can sleep one side of their brain while the other side is still alert, but flying frigatebirds actually spend about one-quarter of their sleep time with both sides of the brain asleep!

The summer hayfield buzzes with activity, and swallows skim the tops of the grasses from one end to the other, nabbing insects just above the field. Virtually every barn in North America has swallows nesting in it, and it is rare to find a Barn Swallow nest that is not in a building. This species adapted to nesting in barns almost as soon as the structures were first erected in the U.S., and the rapid spread of humans and barns in the 1800s probably allowed the Barn Swallow to greatly expand its nesting range.

Tree Swallows, like all swallow species, eat mainly insects that they capture in flight. This requires an abundance of small insects in the air, and that requires good weather. When the air is too cold or damp for insects to be flying (a chilly early morning or during a storm, for example), large numbers of swallows will rest together in reeds or bushes. They use torpor to conserve energy (see this page lower left). They can survive for a few days with no food, but longer stretches of cold and damp weather can be a serious challenge.

Several species of crows are found in different regions across the continent, and they are among the most intelligent of all birds. Intelligence is difficult to define, and difficult to test in birds. One indirect measure of intelligence is the ability to adapt and thrive in many different environments—to innovate—and ravens and crows are certainly some of the most innovative birds. They also understand the concept of trading, and have a sense of fair trade. In one study, human experimenters traded with ravens. Some humans were “fair” and traded items of equal value, while others were “unfair,” giving a lower-quality item in exchange. The birds learned the tendency of each individual human and preferred to trade with the fair ones.

Ravens are very closely related to crows, and share the crows’ intelligence and rich social life. Birds use their bills for feather care, preening regularly to keep their feathers properly aligned and clean, but they can’t preen their head with their own bill. For that they must use their feet, to scratch away any debris and to rearrange feathers. Some species have specialized claws with comb-like structures that allow better feather care. Ravens and some other species engage in mutual preening, which is presumably the best way to keep head feathers clean and straight.

This colorful and boldly marked species is common in wooded areas, including suburbs and city parks, and a frequent visitor to birdfeeders throughout the East. Its close relative the Steller’s Jay is similarly common in the West. When theories of protective coloration were first being debated around 1900, birds like the Blue Jay were a puzzle. It was difficult to imagine how such flashy colors could be helpful for concealment. Now we know that color patterns evolve for many reasons, not just camouflage. The head pattern of the Blue Jay is probably to disrupt the perceived shape of the head, making it harder for a predator to recognize the bird and to tell what direction it is looking. The bright white flashes in wings and tail probably help by startling a predator in the moments before an attack. One experiment found that fast movement by prey would cause a predator to hesitate, and even more so if the fast movement is accompanied by a sudden flash of color. A panicked Blue Jay taking off in a burst of movement and flashes of white could cause a predator to flinch, and that might allow the jay to escape.

Several closely related species of scrub-jays are found in the western and southern U.S., where they are among the most brash and fearless visitors to bird feeders. They are especially fond of peanuts. Like other jays, they seem to be particularly susceptible to West Nile Virus, which arrived in North America in 1999 and spread quickly across the continent like other invasive species (see this page, European Starling), becoming a serious threat to birds as well as a major human health issue. Birds are the host of the virus, which is transmitted by mosquitoes. Initially, populations of jays and many other species declined sharply. While some species recovered quickly, recent surveys show that populations of other species are still reduced.

Black-capped, Mountain, and Chestnut-backed Chickadees

Inquisitive, bold, and social, chickadees are among the most popular and well-known birds wherever they occur. They are among the most reliable customers at bird feeders, and are often the first to discover a new feeder. Named for their chick-a-DEE-DEE-DEE call, their scolding dee-dee-dee calls announce the presence of predators or any other newsworthy event. Like many other birds (and unlike humans), chickadees can see ultraviolet light—a whole range of color beyond purple. Male and female chickadees look alike to us, with white cheeks, but they look quite different to each other, as males have a much stronger ultraviolet reflection on their cheeks.

Titmice are closely related to chickadees, and the four species in North America all have drab grayish color and short crests. As early as the 1300s the name titmose was in use in England, by combining the Middle English words tit (meaning “small”) and mose (meaning “small bird”)—literally “small small bird.” After a century or two, this became titmouse, and in another century or two was shortened to tit, which is still used today for Eurasian species such as the Blue Tit. The name chickadee is uniquely American, and refers to the birds’ distinctive calls. Early Europeans in North America used the name titmouse for chickadees as well—for example, in 1840 Audubon wrote about the Black-capt Titmouse.

Bushtits are the smallest non-hummingbird birds in North America, slightly smaller than the Golden-crowned Kinglet. Five of them together weigh one ounce. They are found in the western states in open brush and gardens. They almost always travel in flocks of up to several dozen, constantly flitting and chattering through the foliage of shrubs and trees. Despite their similarity to chickadees they are not closely related. Their nearest relatives are in Europe and Asia.

White-breasted Nuthatch and Red-breasted Nuthatch

Nuthatches spend a lot of time clinging to the bark of trees, like woodpeckers, but the similarities end there. They cling to the bark with just their feet and can move in any direction around a tree trunk. They do not chisel into wood with their bills, instead mostly gleaning food from the bark. When visiting bird feeders, they quickly grab a seed and fly back into a tree. Wedging the seed into a bark crevice, they pound it open with their bill. This is apparently the origin of their name—they are really nut hackers. White-breasted Nuthatches are resident and defend their territories year-round, but many Red-breasted Nuthatches nest in the far north. In years when the numbers of spruce and pine seeds in the northern forests are low, Red-breasted Nuthatches move south in huge numbers.

Vireos are small and inconspicuous songbirds, generally found in dense leafy vegetation and more noticeable for their voice than for their appearance. They are not related to toucans, but the Red-eyed Vireos that spend the summer in the U.S. and southern Canada migrate south to winter in the Amazon basin in South America, and they have all seen toucans.

The wrens are a Neotropical family, with only one species in the Old World, and only a few north of Mexico. Most species are nonmigratory, and mainly insectivorous, which limits their range to warm climates. Among the most remarkable features of wrens are their songs, which are loud, rich, and varied. Each male Carolina Wren knows a repertoire of up to fifty different song phrases, which it uses in various performances to impress mates or rivals. Males from the western population of the Marsh Wren have an even more diverse repertoire of up to 220 different songs!

The Golden-crowned Kinglet is one of the smallest birds in North America, smaller than some hummingbirds. They weigh about as much as a U.S. nickel, and still manage to survive the winter as far north as Canada. Most of the day—up to 85 percent of daylight hours—is devoted to searching for food. At night they find a sheltered spot, huddle with up to ten or so other kinglets, and enter torpor to conserve energy. Like other birds, their metabolism increases in the winter, essentially revving the engine to produce more heat, even though this uses more fuel. They eat insects, which in the winter means mainly insect eggs and larvae gleaned from twigs and bark. Kinglets in the winter probably need at least eight calories a day, which doesn’t sound like much, but if we ate at the same rate, a hundred-pound person would need about sixty-seven thousand calories, which is about twenty-six pounds of peanuts, or twenty-seven large pizzas, every day. Do you “eat like a bird”?

One of the most familiar and beloved birds in North America, the American Robin is equally at home in the foothills of California, the shelterbelts of Nebraska, and the suburbs of Boston. No matter where your backyard is, if you have a grassy lawn, chances are you will see robins there hunting earthworms. It has been calculated that a single robin can eat 14 feet of earthworms in a day. When early British colonists noticed this bird’s red breast, it reminded them of the robin they knew from gardens in Britain, and they named this bird to match, but the two species are only distantly related, and the American Robin is much larger.

The Wood Thrush and several similar species are related to the American Robin but are retiring denizens of shaded forest. All have extraordinary songs. Many birds defend a nesting territory in the summer. This is essentially a bit of private property, and the nesting pair that has claimed it will defend their territory against others of their species. Ideally their “property” will provide everything that is needed to successfully nest and raise young. They defend as much space as they need, so territories tend to be small in very productive areas and larger elsewhere. A few species of long-distance migrants (including thrushes) also defend winter territories, but as individuals, not in pairs. In both winter and summer birds are very faithful to their territory and return each year. A Wood Thrush might spend its whole life on the same few acres each summer and winter, with a 1,500-mile commute in between.

With their gentle demeanor and pleasing colors, bluebirds are among the most beloved birds in North America. They are classified in the thrush family, related to the American Robin and the Wood Thrush. Besides their color, they differ from other thrushes in their choice of habitat (open fields and orchards), nesting site (in a cavity), and in their social system (traveling in small groups of five to ten birds). They eat mainly insects and fruit, but in recent years some bluebirds have begun to frequent bird feeders, where they eat softer foods like suet, sunflower hearts, and mealworms.

The mockingbird gets its name from its habit of mimicking the sounds of other species in its song. They are not “mocking” these other species, of course. Most likely the sounds have no particular meaning (although there is evidence that mockingbirds know the source of their material). The birds are simply using the variety of sounds to show off their vocal prowess. Copying sounds that they hear is an easy way to expand their repertoire, and could also allow other mockingbirds to judge the quality of the copy. On average each male knows about 150 different sounds, and mixes them up in every singing bout.

Native to Europe, starlings were introduced in New York City in 1890, and quickly multiplied, spreading to the Pacific coast by the 1950s and becoming one of the most abundant birds on the continent. As their numbers increased, they usurped the nesting cavities of native species like the Eastern Bluebird and the Red-headed Woodpecker, contributing to the declines of those species. In North America, starlings are considered an invasive species—a nonnative species that spreads and causes economic or environmental damage. But starlings are not malicious; they have simply adapted to, and thrive in, the environment created by humans (see this page). The North American continent had been altered by other invasive species well before starlings arrived here. Earthworms are nonnative, and they fundamentally alter plant communities by changing the chemistry and structure of the soil. Most of the backyard and roadside plants that we see every day were also introduced from elsewhere: dandelion, buckthorn, most honeysuckle, kudzu, knapweed, and others, as well as hundreds of species of insects including the honeybee and the cabbage white butterfly. And humans are, of course, the ultimate invasive species. Starling populations in the U.S. have declined dramatically since the 1960s, presumably due to changes in farming practices, and their impact is now greatly reduced.

Waxwings get their name from the small red tips on the feathers of their inner wing, which reminded early naturalists of the red sealing wax used on important letters. The birds’ red markings are not wax, of course, but keratin (the same substance as the rest of the feather) formed into a solid flat tip and decorated with red pigment. Waxwings eat mainly fruit, and live an itinerant life, moving continuously through the winter. They spend most of the year in small flocks simply wandering in search of fruit. They will stay in an area only as long as the fruit lasts, then wander again in search of the next meal. For example, birds tagged in Saskatchewan were found later in California, Louisiana, and Illinois. One bird wandered from Ontario to Oregon, another from Iowa to British Columbia.

The wood warblers are the most numerous, conspicuous, and diverse of the Neotropical migrants—species that nest in North America and winter in the subtropics and tropics. Their arrival each spring in the North is eagerly anticipated by birders, especially in the eastern part of the continent, where a “fallout” of migrants can include twenty or more species of brilliantly colored warblers. The fact that most species weigh under 10 grams (about a third of an ounce) makes their intercontinental journeys even more remarkable. The Black-throated Blue Warbler is typically found in moist leafy understory—the kind of situation created by a stand of mountain laurel or rhododendron. Most species have similarly narrow preferences for habitat, and this makes them vulnerable as even small shifts in climate lead to changes in plant communities.

Blackpoll, Townsend’s, and Hooded Warblers

Over fifty species of wood warblers in North America show an incredible diversity of colors and patterns, with the black pigment melanin a key to that variation. Wood warblers are known for their intense colors and high energy—the late ornithologist Frank Chapman once called them the “dainty, fascinating sprites of the tree-tops.” We tend to focus on the brilliant yellow to red carotenoid pigments, and the brightness of these colors might be an indication of the health of the bird (see this page). The black feathers also contribute to the appearance of most species of warblers. Patches of deep black are striking, and bright yellow and orange seem even more brilliant when set off against black. Recent research has found that healthier birds produce blacker feathers, not because of more pigment, but because of the microstructure of the feathers themselves. More barbules and a more consistent feather structure create a deeper black appearance. In this way, differences in melanin-based markings might be an important signal of the condition of the bird.

The brightly colored tanagers live mainly in the forest canopy. Larger than warblers, with stout bills, they are actually related to cardinals. The lives of highly migratory species like the Scarlet Tanager have to run on a strict schedule. Spring migration leads immediately into nesting, and in the few weeks between nesting and fall migration they need to complete a molt of all of their feathers. Birds have an excellent sense of time and a complex relationship with time. Certain genes are known to be associated with time cycles, and multiple light sensors synchronize annual and daily cycles according to day length. This allows birds to begin and end migration on time, and also, for example, to adjust their migration direction and urgency to date and latitude. A sense of time is also critical to singing and many other daily activities.

Named for its bright red color, like the robes of the cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church, this is one of the most recognizable birds in North America. In the breeding season (spring and summer) it is common to see a male cardinal feeding an adult female. The males are signaling their fitness in their ability to find enough food to share with their mate. This is one of the species that has benefited most from suburbanization over the last century. Cardinals thrive in the suburban landscape of open lawns with scattered shrubs and trees and plentiful bird feeders. In 1950 they were found north only to southern Illinois and New Jersey; now they are a conspicuous visitor to bird feeders year-round as far north as southern Canada.

Related to cardinals, the grosbeaks are highly migratory, nesting across the U.S. and southern Canada, and wintering in Central America. Why migrate? There are many downsides to migration: it’s dangerous and energy intensive, and it requires extreme adaptations. Even brain size is linked to migratory habits. Large brains require a lot of energy, making them incompatible with long-distance flights, so migratory species average smaller brains. But about 19 percent of the world’s bird species, and huge numbers of birds, migrate every year. Migrants are able to nest in areas with reduced competition and a burst of abundant food. Basically, they are traveling farther to get cheap food and lodging. The trip is not easy but the deals are so good it’s worth the extra distance. The energy used to travel is paid back by the energy gained in the northern summer.

Lazuli Bunting and Indigo Bunting

Related to cardinals and grosbeaks, buntings are small finch-like birds of hedgerows and brushy edges. Buntings are strongly sexually dimorphic—the males and females look different—and recent studies show that this is linked to migration. More than three-quarters of migratory species are dimorphic, while over three-quarters of sedentary species are not. In sedentary populations pairs remain together on a small territory all year and usually share the work of defending that territory and raising young. With migration, sexual roles diverge. Males arrive on the breeding grounds first and establish a territory, females come a few days later and select a mate. The most attractive males are more likely to be chosen, and more quickly, which drives the evolution of more showy plumage. As the female’s responsibilities shift away from territorial defense into the work of raising a family, drabber plumage is an advantage. It provides better camouflage and is less costly to produce, leaving her with more resources for the combined demands of migrating and producing eggs.

Several species of towhees (which are basically oversized sparrows) are found in different regions across North America. Two plain brownish species are often seen in suburban yards in the southwest and in California. Birds that live in the desert have evolved and adapted to stay cool and conserve water. They can get by with little water, but they do need some. During the hottest part of the day, birds reduce their activities overall and try to relax in the shade. Foraging activities and trips to water occur mainly early and late in the day. Many species have long-term pair bonds and maintain year-round territories, reducing the need for energetic displays. Fighting is relatively rare. And there are many mechanisms to shelter eggs and chicks from the heat, and to provide water. Even with all of this, life in the desert is challenging. A recent study of future climate suggests that many songbirds (especially smaller species) will not be able to survive the predicted higher temperatures in the desert.

Almost every winter bird feeder in the United States and southern Canada is visited by Dark-eyed Juncos, but the juncos that show up can look very different depending on where you live. The birds shown here are all males of the same species—Dark-eyed Junco—but represent distinct regional variations or subspecies. Slate-colored Junco (upper) is found mainly east of the Rocky Mountains. Oregon (middle) is found in the west, and Gray-headed (lower) is found in the southern Rocky Mountains. Evolution is an ongoing process continuing all the time, and populations in different regions can diverge (evolve different features) because of different selective pressures. With enough time and divergence they can become different species. In the case of the Dark-eyed Junco, all the differences we see have evolved since the last ice age, about fifteen thousand years ago. These populations look quite different, but they sound the same, act the same, and (most important) seem to recognize each other as the same species and interbreed wherever their ranges meet. Regional populations that we can distinguish, but that don’t seem to be recognized by the birds, are classified as subspecies (see this page).

This species is the the most familiar sparrow in the West, found in large winter flocks in weedy areas. There are many other species of sparrows, almost all of them brownish and streaked and found on or near the ground. Most small songbirds migrate at night, which makes their journeys even more remarkable and mysterious. The potential advantages of flying at night include: less turbulent air; cooler temperatures that mean less water lost to panting; fewer predators; stars more visible for navigation; and the daytime can be spent on refueling. After sunset birds launch into flight, climb to several thousand feet, and fly for hours. How they decide which night to fly is complex. In the big picture, changes in day length trigger hormones, which lead to physiological changes that increase the bird’s urge and ability to migrate. Even captive birds display this migratory restlessness in the spring and fall—fidgeting, nocturnal activity, and other actions. Each night a bird might check its body condition, fat reserves, the current temperature and trend, wind direction and speed, changes in barometric pressure, approaching weather, date, current location, and more. A complex appraisal of all of these factors leads to a decision to take off or to wait. Launching into the night with an unknown destination is risky, but waiting might be even more risky (see this page).

This is the familiar sparrow of gardens and hedgerows, especially in the East. In the spring and early summer many people find that a bird is attacking their windows. The bird is not just flying into the glass randomly, or trying to get into the house—it is attacking its reflection in the glass. The bird sees itself in the reflective surface (a car’s side-view mirror is also a common target) and with breeding-season hormones making it more aggressive and territorial, the sight of a potential rival triggers the need to defend its territory and a relentless but futile effort to drive off the intruder. You can eliminate the reflection by covering the glass (on the outside), but the bird will usually just move to another window and continue its attacks there. If you just want to stop it from attacking a bedroom window and waking you up, for example, then covering one or two windows might be enough. The activity should taper off in a few weeks, as the breeding season ends and the territorial drive fades.

The House Sparrow, native to Eurasia, is not closely related to the sparrows native to North America. It is one of the most successful bird species in the world, colonizing cities on every continent except Antarctica. Like crows and starlings, this species has proven to be extremely adaptable, and has spread by taking advantage of opportunities that other birds do not. They live in small groups all year, and one of the secrets of their success may be the fact that groups are better at problem solving. This effect has been shown in many animals, from humans to birds. When faced with a puzzle, such as an inaccessible food source, a group of birds might each try a slightly different approach. If one bird solves the problem, the rest of the group learns from that and all have access to the food. One study found that groups of six sparrows solved problems seven times faster than groups of two, and that urban sparrows were better at problem solving than country sparrows. For all of their success, however, House Sparrow populations have been declining worldwide for many decades. This is presumably related to the decline of small farms and livestock, including the shift from horses to cars for transportation.

These small streaked finches are regular visitors to bird feeders and—true to their name—they are often seen around houses. If you have small finches nesting on a windowsill, porch ledge, or Christmas wreath, they are undoubtedly House Finches. Adult males are bright red on the head and breast, while females are brownish and streaked, without red. The House Finch is native to the western United States and only recently colonized the East. It is said that in 1939, a pet store owner on Long Island, New York, released a small number of House Finches when he learned that it was illegal to keep native birds. From that small group they spread throughout the eastern U.S., and have now met and merged with the expanding western population.

Known to many—appropriately—as “Wild Canaries,” goldfinches are among the most conspicuous bright yellow birds. The American Goldfinch is found continent-wide, and the Lesser Goldfinch only in the West. All are frequent visitors to bird feeders, and a flock will often sit calmly for minutes at a time, occupying all of the perches on a feeder and nibbling seeds. Most migratory birds travel as individuals, but goldfinches travel in flocks during the nonbreeding season, and there is some evidence that groups can stay together for years. A European study of tagged siskins (close relatives of goldfinches) found multiple records of birds that were recaptured together a month later, with maximum records of birds still together after more than three years and over 800 miles.

The Bobolink and the meadowlarks are all related to blackbirds and orioles. They are found in open meadows and pastures, and their songs are some of the most iconic sounds of summer hayfields. For nesting these birds require a large open field with tall grass, and little disturbance (for example, free of dog walkers). Fields meeting those requirements have become scarce in many areas, and Bobolinks and meadowlarks have correspondingly become scarce. They are still common in the Great Plains and other areas with large hay fields. When they leave the breeding grounds, Bobolinks migrate in flocks to the grasslands of southern South America—one of the longest migrations of any songbird.

Several species of orioles migrate north to breed in North America, but most oriole species are resident in Central and South America. Migratory habits can adapt quickly, and even within a species there can be wide variation in both migratory and sedentary populations. It has long been assumed that migratory behavior is the more recent trait, with sedentary tropical ancestors gradually increasing seasonal shifts to the north. A recent study suggests that migratory behavior appeared and disappeared multiple times as different species evolved, and that many songbirds now resident in the American tropics evolved from migratory species. In this scenario, some individuals of a species nesting in North America and wintering in the tropics would simply not migrate all the way back to the north, and remain in or near the tropics to breed. Then, being isolated from the migratory population, the new tropical group would evolve into a distinct species.

Brown-headed Cowbirds (in the blackbird family) use a nesting strategy called brood parasitism. They lay their eggs in other birds’ nests, and the unwitting foster parents do all of the work of incubating and feeding the young cowbird. The foster parents continue to care for the baby cowbird even if it grows much larger than them. It’s tempting to criticize the cowbird, and some of their behavior can seem cruel and downright criminal, but we have to guard against the tendency to project our own values on the natural world. The female cowbird does not choose to lay her eggs in the nests of other birds—that’s just the way cowbirds have evolved, and she seeks every advantage for her own offspring. It’s a remarkable system, and for the cowbirds it works remarkably well.

The Common Grackle is truly common in suburban and rural habitats across the eastern two-thirds of the continent. They are large, strong, and opportunistic, and can prey on the eggs and young of smaller songbirds. Like some other species, such as crows and Brown-headed Cowbirds, grackles feed on corn and other crops, and are essentially subsidized by human agriculture. This allows their population to increase, which leads to greater impacts on the species around them. It’s not their fault, and doesn’t have to detract from their iridescent splendor.

Wherever there is water and dense reeds or brush, you can find the Red-winged Blackbird. A small patch of cattails or willows in a roadside culvert makes a suitable nesting territory, and in more extensive marshes hundreds nest in close proximity. One of the harbingers of spring, males return and start advertising on their territories as early as the first warm days in February, even in New England.