When a constant-density fluid flows without rotation, and pressure is measured relative to its local hydrostatic value (see

Section 4.9), the equations of fluid motion in an inertial frame of reference,

(4.7) and

(4.38), simplify to:

even though the fluid’s viscosity

μ may be non-zero. These are the equations of

ideal flow. They are useful for developing a first-cut understanding of nearly any macroscopic fluid flow, and are directly applicable to low-Mach-number irrotational flows of homogeneous fluids away from solid boundaries. Ideal flow theory has abundant applications in the exterior aero- and hydrodynamics of moderate- to large-scale objects at non-trivial subsonic speeds. Here, moderate size (

L) and non-trivial speed (

U) are determined jointly by the requirement that the Reynolds number, Re =

ρUL/μ (4.103), be large enough (typically Re

∼

10

3 or greater) so that the combined influence of fluid viscosity and fluid element rotation is confined to thin layers on solid surfaces, commonly known as

boundary layers.

The conditions necessary for the application of ideal flow theory are commonly present on the upstream side of many ordinary objects, and may even persist to the downstream side of some. Ideal flow analysis can predict fluid velocity away from solid surfaces, surface-normal pressure forces (when the boundary layer on the surface is thin and attached), acoustic streamlines, flow patterns that minimize form drag, and unsteady-flow fluid-inertia effects. Ideal flow theory does not predict viscous effects like skin friction or energy dissipation, so it is not directly applicable to interior flows in pipes and ducts, to boundary-layer flows, or to any rotational flow region. This final specification excludes low-Re flows and regions of turbulence.

Because

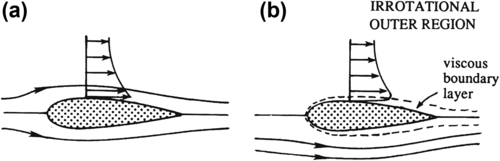

(7.1) involves only first-order spatial derivatives, ideal flows only satisfy the no-through-flow boundary condition on solid surfaces. The no-slip boundary condition

(4.94) is not applied in ideal flows, so non-zero tangential velocity at a solid surface may exist (

Figure 7.1a). In contrast, a real fluid with a non-zero shear viscosity must satisfy the

no-slip boundary condition

(4.94) because

(4.38) contains second-order spatial derivatives. At sufficiently high Re, there are two primary differences between ideal and real flows over the same object. First, viscous boundary layers containing rotational fluid form on solid surfaces in the real flow, and the thickness of such boundary layers, within which viscous diffusion of vorticity is important, approaches zero as Re → ∞ (

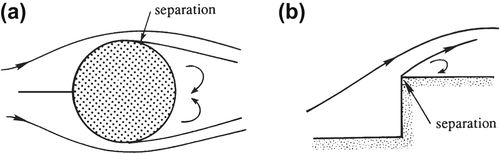

Figure 7.1b). The second difference is the possible formation in the real flow of

separated flow or

wake regions that occur when boundary layers leave the surface on which they have developed to create a wider zone of rotational flow (

Figure 7.2). Ideal flow theory is not directly applicable to such layers or regions of rotational flow. However, rotational flow regions may be easy to anticipate or identify, and may represent a small fraction of a total flow field so that predictions from ideal flow theory may remain worthwhile even when viscous flow phenomena are present. Further discussion of viscous-flow phenomena is provided in

Chapters 9 and

10.

For

(4.10) and (7.1) to apply, fluid density

ρ must be constant and the flow must be irrotational. If the flow is merely incompressible and contains baroclinic density variations,

(4.10) will still be satisfied but

(7.1) will not; it will need a body-force term like that in

(4.84) and the reference pressure would have to be redefined. If the fluid is a homogeneous compressible gas with sound speed

c, the constant density requirement will be satisfied when the Mach number,

M =

U/

c (4.111), of the flow is much less than unity. The irrotationality condition is satisfied when fluid elements enter the flow field of interest without rotation and do not acquire any while they reside in it. Based on Kelvin’s circulation theorem

(5.11) for constant density flow, this is possible when the body force is conservative and the net viscous torque on a fluid element is zero. Thus, a fluid element that is initially irrotational is likely to stay that way unless it enters a boundary layer, wake, or separated flow region where it acquires rotation via viscous diffusion. So, when initially irrotational fluid flows over a solid object, ideal flow theory most-readily applies to the

outer region of the flow away from the object’s surface(s) where the flow is irrotational. Viscous flow theory is needed in the

inner region where viscous diffusion of vorticity is important. Often, at high Re, the outer flow can be approximately predicted by ignoring the existence of viscous boundary layers. With this outer flow prediction, viscous flow equations can be solved for the boundary-layer flow and, under the right conditions, the two solutions can be adjusted until they match in a suitable region of overlap. This approach works well for objects like thin airfoils at low angles of attack when boundary layers remain thin and stay attached all the way to the foil’s trailing

edge (

Figure 7.1b). However, it is not satisfactory when the solid object has such a shape that one or more boundary layers separate from its surface before reaching its downstream edge (

Figure 7.2), giving rise to a rotational wake flow or region of separated flow (sometimes called a

separation bubble) that is not necessarily thin, no matter how high the Reynolds number. In this case, the limit of a real flow as

μ→0

does not approach that of an ideal flow (

μ = 0). Yet, upstream of boundary-layer separation, ideal flow theory may still provide a good approximation of the real flow.

In summary, the theory presented here does not apply to inhomogeneous fluids, high subsonic or supersonic flow speeds, boundary-layer flows, wake flows, interior flows, or any flow region where fluid elements rotate. However, the remaining flow possibilities are abundant, and include those that are commercially valuable (flight), naturally important (water waves), or readily encountered in our everyday lives (flow around vehicles, also see

Chapters 8 and

14 for further examples).

Steady and unsteady irrotational constant-density flow fields around simple objects and through simple geometries in two and three dimensions are the subjects of this chapter. All the coordinate systems presented in

Figure 3.3 are utilized herein.

(4.10, 7.1)

(4.10, 7.1)

does not approach that of an ideal flow (μ = 0). Yet, upstream of boundary-layer separation, ideal flow theory may still provide a good approximation of the real flow.

does not approach that of an ideal flow (μ = 0). Yet, upstream of boundary-layer separation, ideal flow theory may still provide a good approximation of the real flow.