25

Psychiatric Disorders

Kristin S. Raj, MD

Nolan Williams, MD

Charles DeBattista, DMH, MD

The fifth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) is the common language that clinicians use for psychiatric conditions. It utilizes specific criteria with which to objectively assess symptoms for use in clinical diagnosis and communication.

COMMON PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

ADJUSTMENT DISORDERS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Anxiety or depression in reaction to an identifiable stress, though out of proportion to the severity of the stressor.

Anxiety or depression in reaction to an identifiable stress, though out of proportion to the severity of the stressor.

Symptoms are not at the severity of a major depressive episode or with the chronicity of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).

Symptoms are not at the severity of a major depressive episode or with the chronicity of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).

General Considerations

General Considerations

An individual experiences stress when adaptive capacity is overwhelmed by events. The event may be an insignificant one when objectively considered, and even favorable changes (eg, promotion and transfer) requiring adaptive behavior can produce stress. For everyone, stress is subjectively defined, and the response to stress is a function of each person’s personality and physiologic endowment.

Opinion differs about what events are most apt to produce stress reactions. The causes of stress are different at different ages—eg, in young adulthood, the sources of stress are found in the marriage or parent-child relationship, the employment relationship, and the struggle to achieve financial stability; in the middle years, the focus shifts to changing spousal relationships, problems with aging parents, and problems associated with having young adult offspring who themselves are encountering stressful situations; in old age, the principal concerns are apt to be retirement, loss of physical and mental capacity, major personal losses, and thoughts of death.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

An individual may react to stress by becoming anxious or depressed, by developing a physical symptom, by running away, drinking alcohol, overeating, starting an affair, or in limitless other ways. Common subjective responses are anxiety, sadness, fear, rage, guilt, and shame. Acute and reactivated stress may be manifested by restlessness, irritability, fatigue, increased startle reaction, and a feeling of tension. Inability to concentrate, sleep disturbances (insomnia, bad dreams), and somatic preoccupations sometimes lead to self-medication, most commonly with alcohol or other central nervous system depressants. Emotional and behavioral distressing symptomatology in response to stress is called adjustment disorder, with the major symptom specified (eg, “adjustment disorder with depressed mood”). Even with an identifiable stressor, if the patient meets syndromal criteria for another disorder such as major depression, then the convention would be to diagnose a major depression and not an adjustment disorder with depressed mood.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Adjustment disorders are distinguished from anxiety disorders, mood disorders, bereavement, other stress disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and personality disorders exacerbated by stress and from somatic disorders with psychic overlay. Unlike many other psychiatric disorders, such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, adjustment disorders are wholly situational and usually resolve when the stressor resolves or the individual effectively adapts to the situation. Adjustment disorders may have symptoms that overlap with other disorders, such as anxiety symptoms, but they occur in reaction to an identifiable life stressor such as a difficult work situation or romantic breakup. An adjustment disorder that persists and worsens can potentially evolve into another psychiatric disorder such as major depression or GAD. However, that is not the case for most patients. Patients with adjustment disorders have marked distress after a stressor and significant impairment in social or occupational functioning but not to the degree experienced by patients with a more severe disorder such as major depressive disorder or PTSD. By definition, an adjustment disorder occurs within 3 months of an identifiable stressor.

Treatment

Treatment

A. Behavioral

Stress reduction techniques include immediate symptom reduction (eg, rebreathing in a bag for hyperventilation) or early recognition and removal from a stress source before full-blown symptoms appear. It is often helpful for the patient to keep a daily log of stress precipitators, responses, and alleviators. Relaxation, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and exercise techniques are also helpful in improving the reaction to stressful events.

B. Social

The stress reactions of life crisis problems are a function of psychosocial upheaval. While it is not easy for the patient to make necessary changes (or they would have been made long ago), it is important for the clinician to establish the framework of the problem, since the patient’s denial system may obscure the issues. Clarifying the problem in the patient’s psychosocial context allows the patient to begin viewing it within the proper frame and facilitates the difficult decisions the patient eventually must make (eg, change of job).

C. Psychological

Prolonged in-depth psychotherapy is seldom necessary in cases of isolated stress response or adjustment disorder. Supportive psychotherapy (see above) with an emphasis on strengthening of existing coping mechanisms is a helpful approach so that time and the patient’s own resiliency can restore the previous level of function. In addition, cognitive behavioral therapy has long been established to treat acute stress and facilitate recovery in patients with an adjustment disorder.

D. Pharmacologic

Judicious use of sedatives (eg, lorazepam, 0.5–1 mg two or three times daily orally) for a limited time and as part of an overall treatment plan can provide relief from acute anxiety symptoms. Problems arise when the situation becomes chronic through inappropriate treatment or when the treatment approach supports the development of chronicity. There are occasions where the short-term use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) targeting dysphoria and anxiety may be useful.

Prognosis

Prognosis

Return to satisfactory function after a short period is part of the clinical picture of this syndrome. Resolution may be delayed if others’ responses to the patient’s difficulties are thoughtlessly harmful or if the secondary gains outweigh the advantages of recovery. The longer the symptoms persist, the worse the prognosis. There is also evidence that stress-related disorders are associated with increased risk of autoimmune disease, although this mechanism has yet to be elucidated.

Song H et al. Association of stress-related disorders with subsequent autoimmune disease. JAMA. 2018 Jun 19;319(23):2388–400. [PMID: 29922828]

TRAUMA & STRESSOR-RELATED DISORDERS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Exposure to a traumatic or life-threatening event.

Exposure to a traumatic or life-threatening event.

Flashbacks, intrusive images, and nightmares, often represent reexperiencing the event.

Flashbacks, intrusive images, and nightmares, often represent reexperiencing the event.

Avoidance symptoms, including numbing, social withdrawal, and avoidance of stimuli associated with the event.

Avoidance symptoms, including numbing, social withdrawal, and avoidance of stimuli associated with the event.

Increased vigilance, such as startle reactions and difficulty falling asleep.

Increased vigilance, such as startle reactions and difficulty falling asleep.

Symptoms impair functioning.

Symptoms impair functioning.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been reclassified from an anxiety disorder to a trauma and stressor-related disorder in the DSM-5. PTSD is a syndrome characterized by “reexperiencing” a traumatic event (eg, sexual assault, severe burns, military combat) and decreased responsiveness and avoidance of current events associated with the trauma. The lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adult Americans has been estimated to be 6.8% with a point prevalence of 3.6% and with women having rates twice as high as men. Many individuals with PTSD (20–40%) have experienced other associated problems, including divorce, parenting problems, difficulties with the law, and substance abuse.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

The key to establishing the diagnosis of PTSD lies in the history of exposure to a perceived or actual life-threatening event, serious injury, or sexual violence. This can include serious medical illnesses, and the prevalence of PTSD is higher in people who have experienced serious illnesses such as cancer. The symptoms of PTSD include intrusive thoughts (eg, flashbacks, nightmares), avoidance (eg, withdrawal), negative thoughts and feelings, and increased reactivity. Patients with PTSD can experience physiologic hyperarousal, including startle reactions, illusions, overgeneralized associations, sleep problems, nightmares, dreams about the precipitating event, impulsivity, difficulties in concentration, and hyperalertness. The symptoms may be precipitated or exacerbated by events that are a reminder of the original traumatic event. Symptoms frequently arise after a long latency period (eg, child abuse can result in later-onset PTSD). DSM-5 includes the requirement that the symptoms persist for at least 1 month. In some individuals, the symptoms fade over months or years, and in others they may persist for a lifetime.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

In 75% of cases, PTSD occurs with comorbid depression or panic disorder, and there is considerable overlap in the symptom complexes of all three conditions. Acute stress disorder has many of the same symptoms as PTSD, but symptoms persist for only 3 days to a month after the trauma. The other major comorbidity is alcohol and substance abuse. The Primary Care-PTSD Screen and the PTSD Checklist are two useful screening instruments in primary care clinics or community settings with populations at risk for trauma exposure.

Treatment

Treatment

A. Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy should be initiated as soon as possible after the traumatic event, and it should be brief (typically 8–12 sessions), once the individual is in a safe environment. Cognitive processing therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and prolonged exposure therapy have demonstrated the greatest evidence in improving symptoms of PTSD. Evidence also shows that these psychotherapies may be more beneficial than medications alone for PTSD. In these approaches, the individual confronts the traumatic situation and learns to view it with less reactivity. Posttraumatic stress syndromes respond to interventions that help patients integrate the event in an adaptive way with some sense of mastery in having survived the trauma. Partner relationship problems are a major area of concern, and it is important that the clinician have available a dependable referral source when marriage counseling is indicated.

Treatment of any comorbid substance abuse is an essential part of the recovery process for patients with PTSD. In patients with comorbid substance use disorders, there is evidence for better outcomes when substance abuse treatment is delivered alongside trauma-focused psychotherapy. Support groups and 12-step programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous are often very helpful.

Video telepsychiatry for psychotherapy or medication management allows for access to these resources that some patients, such as those in rural settings, may not otherwise have. There is similar efficacy in reduction of PTSD symptoms in women veterans with video teletherapy as with in-person therapy, and the practice of telepsychiatry is becoming more widely available.

B. Pharmacotherapy

SSRIs are helpful in ameliorating depression, panic attacks, sleep disruption, and startle responses in PTSD. Sertraline and paroxetine are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for this purpose, and the SSRIs are the only class of medications approved for the treatment of PTSD. They are, therefore, considered the pharmacotherapy of choice for PTSD. Early treatment of anxious arousal with beta-blockers (eg, propranolol, 80–160 mg orally daily) may lessen the peripheral symptoms of anxiety (eg, tremors, palpitations) but has not been shown to help prevent development of PTSD. Similarly, noradrenergic agents such as clonidine (titrated from 0.1 mg orally at bedtime to 0.2 mg three times a day) have been shown to help with the hyperarousal symptoms of PTSD. The alpha-adrenergic blocking agent prazosin (2–10 mg orally at bedtime) has mixed evidence for decreasing nightmares and improving quality of sleep in PTSD, with a recent negative randomized control trial. Benzodiazepines, such as clonazepam, are generally thought to be contraindicated in the treatment of PTSD. The risks of benzodiazepines, including addiction and disinhibition, are thought to outweigh the anxiolytic and sleep benefits in most patients. Trazodone (25–100 mg orally at bedtime) is commonly prescribed as a non–habit forming hypnotic agent. Second-generation antipsychotics have not demonstrated significant utility in the treatment of PTSD, but agents such as quetiapine 50–300 mg/day may have a limited role in treating agitation and sleep disturbance in PTSD patients. Work with novel agents such as MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine; also called Ecstasy) have shown early promise in the treatment of PTSD and are under investigation.

Prognosis

Prognosis

The sooner therapy is initiated after the trauma, the better the prognosis. A study published in 2018 comparing sertraline and prolonged exposure therapy for patients with PTSD demonstrated that patients who received their preferred treatment were more likely to be adherent, respond to treatment, and have lower self-reported PTSD, depression, and anxiety symptoms. Approximately half of patients with PTSD experience chronic symptoms. Prognosis is best in those with good premorbid psychiatric functioning. Individuals experiencing an acute stress disorder typically do better long-term than those experiencing a delayed posttraumatic disorder. Individuals who experience trauma resulting from a natural disaster (eg, earthquake or hurricane) tend to do better than those who experience a traumatic interpersonal encounter (eg, rape or combat).

Guideline Development Panel for the Treatment of PTSD in Adults, American Psychological Association. Summary of the clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Am Psychol. 2019 Jul–Aug;74(5):596–607. [PMID: 31305099]

Merz J et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of pharmacological, psychotherapeutic, and combination treatments in adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a network meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(9):904–13. [PMID: 31188399]

Raskind MA et al. Trial of prazosin for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 8;378(6):507–17. [PMID: 29414272]

Zoellner LA et al. Doubly randomized preference trial of prolonged exposure versus sertraline for treatment of PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2019 Apr 1;176(4):287–96. [PMID: 30336702]

ANXIETY DISORDERS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Persistent excessive anxiety or chronic fear and associated behavioral disturbances.

Persistent excessive anxiety or chronic fear and associated behavioral disturbances.

Somatic symptoms referable to the autonomic nervous system or to a specific organ system (eg, dyspnea, palpitations, paresthesias).

Somatic symptoms referable to the autonomic nervous system or to a specific organ system (eg, dyspnea, palpitations, paresthesias).

Not limited to an adjustment disorder.

Not limited to an adjustment disorder.

Not a result of physical disorders, other psychiatric conditions (eg, schizophrenia), or drug abuse (eg, cocaine).

Not a result of physical disorders, other psychiatric conditions (eg, schizophrenia), or drug abuse (eg, cocaine).

General Considerations

General Considerations

Stress, fear, and anxiety all tend to be interactive. The principal components of anxiety are psychological (tension, fears, difficulty in concentration, apprehension) and somatic (tachycardia, hyperventilation, shortness of breath, palpitations, tremor, sweating). Sympathomimetic symptoms of anxiety are both a response to a central nervous system state and a reinforcement of further anxiety. Anxiety can become self-generating, since the symptoms reinforce the reaction, causing it to spiral. Additionally, avoidance of triggers of anxiety leads to reinforcement of the anxiety. The person continues to associate the trigger with anxiety and never relearns through experience that the trigger need not always result in fear, or that anxiety will naturally improve with prolonged exposure to an objectively neutral stressor.

Anxiety may be free-floating, resulting in acute anxiety attacks, occasionally becoming chronic. Lack of structure is frequently a contributing factor, as noted in those people who have “Sunday neuroses.” They do well during the week with a planned work schedule but cannot tolerate the unstructured weekend. Planned-time activities tend to bind anxiety, and many people have increased difficulties when this is lost, as in retirement.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent psychiatric disorders. About 7% of women and 4% of men will meet criteria for GAD over a lifetime. GAD becomes chronic in many patients with over half of patients having the disorder for longer than 2 years. Anxiety disorder in the elderly is twice as common as dementia and four to six times more common than major depression, and it is associated with poorer quality of life and contributes to the onset of disability. The anxiety symptoms of apprehension, worry, irritability, difficulty in concentrating, insomnia, or somatic complaints are present more days than not for at least 6 months. Manifestations can include cardiac (eg, tachycardia, increased blood pressure), gastrointestinal (eg, increased acidity, nausea, epigastric pain), and neurologic (eg, headache, near-syncope) systems. The focus of the anxiety may be a number of everyday activities.

B. Panic Disorder

Panic attacks are recurrent, unpredictable episodes of intense surges of anxiety accompanied by marked physiologic manifestations. Agoraphobia, fear of being in places where escape is difficult, such as open spaces or public places where one cannot easily hide, may be present and may lead the individual to confine his or her life to home. Distressing symptoms and signs such as dyspnea, tachycardia, palpitations, dizziness, paresthesias, choking, smothering feelings, and nausea are associated with feelings of impending doom (alarm response). Although these symptoms may lead to overlap with some of the same bodily complaints found in the somatic symptom disorders, the key to the diagnosis of panic disorder is the psychic pain and suffering the individual expresses. Panic disorder is diagnosed when panic attacks are accompanied by a chronic fear of the recurrence of an attack or a maladaptive change in behavior to try to avoid potential triggers of the panic attack. Recurrent sleep panic attacks (not nightmares) occur in about 30% of panic disorders. Anticipatory anxiety develops in all these patients and further constricts their daily lives. Panic disorder tends to be familial, with onset usually under age 25; it affects 3–5% of the population, and the female-to-male ratio is 2:1. The premenstrual period is one of heightened vulnerability. Patients frequently undergo evaluations for emergent medical conditions (eg, heart attack or hypoglycemia), which are then ruled out before the correct diagnosis is made. Gastrointestinal symptoms (eg, stomach pain, heartburn, diarrhea, constipation, nausea and vomiting) are common, occurring in about one-third of cases. Myocardial infarction, pheochromocytoma, hyperthyroidism, and various recreational drug reactions can mimic panic disorder and should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Patients who have panic disorder can become demoralized, hypochondriacal, agoraphobic, and depressed. These individuals are at increased risk for major depression and suicide. Alcohol abuse (in about 20%) results from self-treatment and is frequently combined with dependence on sedatives. Some patients have atypical panic attacks associated with seizure-like symptoms that often include psychosensory phenomena (a history of stimulant abuse often emerges). About 25% of panic disorder patients also have obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

C. Phobic Disorders

Simple phobias are fears of a specific object or situation (eg, spiders, height) that are out of proportion to the danger posed, and they tend to be chronic. Social phobias are global or specific; in the former, all social situations are poorly tolerated, while the latter group includes performance anxiety (eg, fear of public speaking). While patients with simple phobias such as fear of heights may function as long as they do not have to be in tall buildings or airplanes, a patient with agoraphobia may not be able to function vocationally or interpersonally.

Treatment

Treatment

In all cases, underlying medical disorders must be ruled out (eg, cardiovascular, endocrine, respiratory, and neurologic disorders and substance-related syndromes, both intoxication and withdrawal states).

A. Pharmacologic

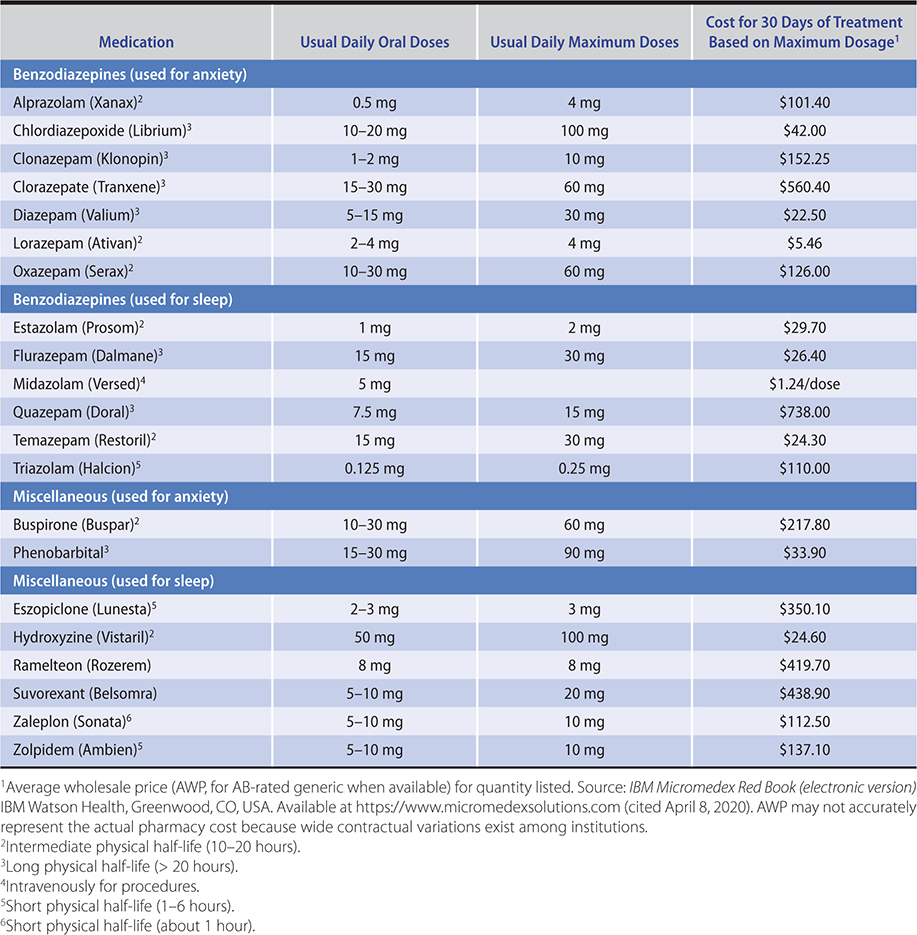

1. Generalized anxiety disorder—Antidepressants including the SSRIs and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are first-line treatment and safe and effective in the long-term management of GAD. Some patients may find more noradrenergic SNRIs such as levomilnacipran too activating to tolerate. The antidepressants appear to be as effective as the benzodiazepines without the risks of tolerance or dependence. However, benzodiazepines take effect more quickly if not immediately, which can be beneficial in brief acute management (Table 25–1).

Table 25–1. Commonly used antianxiety and hypnotic agents (listed in alphabetical order within classes).

Antidepressants are the first-line medications for sustained treatment of GAD, having the advantage of not causing physiologic dependency problems. Antidepressants can themselves be anxiogenic when first started—thus, at the initiation of treatment, patient education and at times concomitant short-term treatment with a benzodiazepine are indicated. SSRIs, such as escitalopram and paroxetine, are FDA-approved. The SNRIs venlafaxine and duloxetine are FDA-approved for the treatment of GAD in usual antidepressant doses. Initial daily dosing should start low (37.5–75 mg for venlafaxine and 30 mg for duloxetine) and be titrated upward as needed. While most antidepressants including tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors are often effective in the treatment of anxiety disorders, their side effects and drug interactions make them second- or third-line agents. Buspirone, sometimes used as an augmenting agent in the treatment of depression and compulsive behaviors, is also effective for generalized anxiety. Buspirone is usually given in a total dose of 30–60 mg/day in divided doses. Higher doses are sometimes associated with side effects of gastrointestinal symptoms and dizziness. Bupropion may be the most anxiogenic antidepressant and does not have evidence in treatment of anxiety disorders. There is a 2- to 4-week delay before antidepressants and buspirone take effect, and patients require education regarding this lag. Sleep is sometimes negatively affected. Gabapentin (titrated to doses of 900–1800 mg orally daily, with larger doses at night) appears effective and lacks the habit-forming potential of the benzodiazepines. Unfortunately, like buspirone, many patients find gabapentin less effective than benzodiazepines in the management of acute anxiety. Beta-blockers, such as propranolol, may help reduce peripheral somatic symptoms. Alcohol is the most frequently self-administered drug and should be strongly discouraged.

2. Panic disorder—Antidepressants are the first-line pharmacotherapy for panic disorder. Several SSRIs, including fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline, are approved for the treatment of panic disorder. The SNRI venlafaxine is FDA approved for treatment of panic disorder. As with GAD, panic disorder is often a chronic condition; the long-term use of benzodiazepines can result in tolerance or even benzodiazepine dependence. While panic disorder often responds to high-potency benzodiazepines such as clonazepam and alprazolam, the best use of these agents is generally early in the course of treatment concurrently with an antidepressant. Once the antidepressant has begun working after 4 or more weeks, the benzodiazepine may be tapered.

Whether the indications for benzodiazepines are anxiety or insomnia, the medications should be used judiciously. The longer-acting benzodiazepines are used for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal and anxiety symptoms; the intermediate medications are useful as sedatives for insomnia (eg, lorazepam), while short-acting agents (eg, midazolam) are used for medical procedures such as endoscopy. Benzodiazepines may be given orally, and several are available in intramuscular or parenteral formulations. In psychiatric disorders, the benzodiazepines are usually given orally; in controlled medical environments (eg, the intensive care unit [ICU]), where the rapid onset of respiratory depression can be assessed, they often are given intravenously. Lorazepam does not produce active metabolites and has a half-life of 10–20 hours; these characteristics are useful in treating elderly patients or those with liver dysfunction. Ultra–short-acting agents, such as triazolam, have half-lives of 1–3 hours and may lead to rebound withdrawal anxiety. Longer-acting benzodiazepines, such as flurazepam, diazepam, and clonazepam, produce active metabolites, have half-lives of 20–120 hours, and should be avoided in the elderly; however, some clinicians prefer clonazepam because of its long half-life and thus ease of dosing to once or twice a day. Since people vary widely in their response and since the medications are long lasting, the dosage must be individualized. Once this is established, an adequate and scheduled dose early in the course of symptom development will obviate the need for “pill popping,” which can contribute to dependency problems.

The side effects of all the benzodiazepine antianxiety agents are patient and dose dependent. As the dosage exceeds the levels necessary for sedation, the side effects include disinhibition, ataxia, dysarthria, nystagmus, and delirium. (The patient should be told not to operate machinery and drive with caution until he or she is well stabilized without side effects.)

Paradoxical agitation, anxiety, psychosis, confusion, mood lability, and anterograde amnesia have been reported, particularly with the shorter-acting benzodiazepines. These agents produce cumulative clinical effects with repeated dosage (especially if the patient has not had time to metabolize the previous dose), additive effects when given with other classes of sedatives or alcohol, and residual effects after termination of treatment (particularly in the case of medications that undergo slow biotransformation).

Overdosage results in respiratory depression, hypotension, shock syndrome, coma, and death. Flumazenil, a benzodiazepine antagonist, is effective in overdosage. Overdosage (see Chapter 38) and withdrawal states are medical emergencies. Serious side effects of chronic excessive dosage are development of tolerance, resulting in increasing dose requirements, and physiologic dependence, resulting in withdrawal symptoms similar in appearance to alcohol and barbiturate withdrawal (withdrawal effects must be distinguished from reemergent anxiety). Abrupt withdrawal of sedative medications may cause serious and even fatal convulsive seizures. Psychosis, delirium, and autonomic dysfunction have also been described. Both duration of action and duration of exposure are major factors related to likelihood of withdrawal.

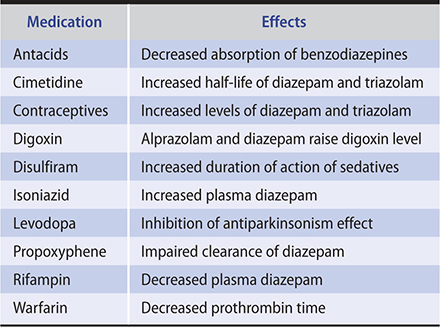

Common withdrawal symptoms after low to moderate daily use of benzodiazepines are classified as somatic (disturbed sleep, tremor, nausea, muscle aches), psychological (anxiety, poor concentration, irritability, mild depression), or perceptual (poor coordination, mild paranoia, mild confusion). The presentation of symptoms will vary depending on the half-life of the medication. Benzodiazepine interactions with other medications are listed in Table 25–2.

Table 25–2. Benzodiazepine interactions with other medications (listed in alphabetical order).

Antidepressants have been used in conjunction with beta-blockers in resistant cases. Propranolol (40–160 mg/day orally) can mute the peripheral symptoms of anxiety without significantly affecting motor and cognitive performance. They block symptoms mediated by sympathetic stimulation (eg, palpitations, tremulousness) but not nonadrenergic symptoms (eg, diarrhea, muscle tension). Contrary to common belief, they usually do not cause depression as a side effect and can be used cautiously in patients with depression.

3. Phobic disorders—Social phobias and agoraphobia may be treated with SSRIs, such as paroxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine. In addition, phobic disorders often respond to SNRIs such as venlafaxine. Gabapentin is an alternative to antidepressants in the treatment of social phobia in a dosage of 300–3600 mg/day, depending on response versus sedation. Specific phobias such as performance or test anxiety may respond to moderate doses of beta-blockers, such as propranolol, 20–40 mg 1 hour prior to exposure. Specific phobias tend to respond to behavioral therapies such as systematic desensitization, which is when the patient is gradually exposed to the feared object or situation in a controlled setting.

B. Behavioral

Behavioral approaches are widely used in various anxiety disorders, often in conjunction with medication. Any of the behavioral techniques can be used beneficially in altering the contingencies (precipitating factors or rewards) supporting any anxiety-provoking behavior. Relaxation techniques can sometimes be helpful in reducing anxiety. Desensitization, by exposing the patient to graded doses of a phobic object or situation, is an effective technique and one that the patient can practice outside the therapy session. Emotive imagery, wherein the patient imagines the anxiety-provoking situation while at the same time learning to relax, helps decrease the anxiety when the patient faces the real-life situation. Physiologic symptoms in panic attacks respond well to relaxation training. Both GAD and panic disorder appear to respond as well to cognitive behavioral therapy as they do to medications. Exercise, both aerobic and resistance training, have demonstrated effects in reducing anxiety symptoms across many anxiety disorders as well.

C. Psychological

Cognitive behavioral therapy is the first-line psychotherapy in treatment of anxiety disorders. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders includes a cognitive component of examining the thoughts associated with the fear, and a behavioral technique of exposing the individual to the feared object or situation. The combination of medication and cognitive behavioral therapy is more effective than either alone. Mindfulness meditation can also be effective in decreasing symptoms of anxiety. Group therapy is the treatment of choice when the anxiety is clearly a function of the patient’s difficulties in dealing with social settings. Acceptance and commitment therapy have been used with some success in anxiety disorders. It encourages individuals to keep focused on life goals while they “accept” the presence of anxiety in their lives.

D. Social

Peer support groups for panic disorder and agoraphobia have been particularly helpful. Social modification may require measures such as family counseling to aid acceptance of the patient’s symptoms and avoid counterproductive behavior in behavioral training. Any help in maintaining the social structure is anxiety-alleviating, and work, school, and social activities should be maintained. School and vocational counseling may be provided by professionals, who often need help from the clinician in defining the patient’s limitations.

Prognosis

Prognosis

Anxiety disorders are usually long-standing and may be difficult to treat. All can be relieved to varying degrees with medications and behavioral techniques. The prognosis is better if the commonly observed anxiety-panic-phobia-depression cycle can be broken with a combination of the therapeutic interventions discussed above.

Carpenter JK et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Depress Anxiety. 2018 Jun;35(6):502–14. [PMID: 29451967]

LeBouthillier DM et al. The efficacy of aerobic exercise and resistance training as transdiagnostic interventions for anxiety-related disorders and constructs: a randomized controlled trial. J Anxiety Disord. 2017 Dec;52:43–52. [PMID: 29049901]

Stein MB et al. Treating anxiety in 2017: optimizing care to improve outcomes. JAMA. 2017 Jul 18;318(3):235–6. [PMID: 28679009]

OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE DISORDER & RELATED DISORDERS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Preoccupations or rituals (repetitive psychologically triggered behaviors) that are distressing to the individual.

Preoccupations or rituals (repetitive psychologically triggered behaviors) that are distressing to the individual.

Symptoms are excessive or persistent beyond potentially developmentally normal periods.

Symptoms are excessive or persistent beyond potentially developmentally normal periods.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), classified as an anxiety disorder in the DSM-IV, now is part of a separate category of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Related Disorders in DSM-5. In OCD, the irrational idea or impulse repeatedly and unwantedly intrudes into awareness. Obsessions (recurring distressing thoughts, such as fears of exposure to germs) and compulsions (repetitive actions such as washing one’s hands many times or cognitions such as counting rituals) are usually recognized by the individual as unwanted or unwarranted and are resisted, but anxiety often is alleviated only by ritualistic performance of the compulsion or by deliberate contemplation of the intruding idea or emotion. Some patients with OCD only experience obsessions, while some experience both obsessions and compulsions. Many patients do not volunteer the symptoms and must be asked about them. There is an overlapping of OCD with some features in other disorders (“OCD spectrum”), including tics, trichotillomania (hair pulling), excoriation disorder (skin picking), hoarding, and body dysmorphic disorder. The incidence of OCD in the general population is 2–3% and there is a high comorbidity with major depression: major depression will develop in two-thirds of OCD patients during their lifetime. Male-to-female ratios are similar, with the highest rates occurring in the young, divorced, separated, and unemployed (all high-stress categories). Neurologic abnormalities of fine motor coordination and involuntary movements are common. Under extreme stress, these patients sometimes exhibit paranoid and delusional behaviors, often associated with depression, and can mimic schizophrenia.

Treatment

Treatment

A. Pharmacologic

OCD responds to serotonergic antidepressants including SSRIs and clomipramine in about 60% of cases and usually requires a longer time to response than depression (up to 12 weeks). Clomipramine has proved effective in doses equivalent to those used for depression. Fluoxetine has been widely used in this disorder but in doses higher than those used in depression (up to 60–80 mg orally daily). The other SSRI medications, such as sertraline, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine, are used with comparable efficacy each with its own side-effect profile. There is some evidence that antipsychotics and topiramate may be helpful as adjuncts to the SSRIs in treatment-resistant cases. Alternatively, low-dose clomipramine may be an effective adjunct to an SSRI in some patients, though caution should be used when prescribing multiple serotonergic agents given the risk of serotonin syndrome. Plasma levels of clomipramine and its metabolite should be checked 2–3 weeks after a dosing of 50 mg/day has been achieved, with levels being kept under 500 ng/mL to avoid toxicity. Preliminary studies have suggested a role for ketamine and esketamine in the treatment of OCD. Small randomized trials have suggested up to 50% of patients get some relief of their OCD symptoms with in 1 week of a ketamine infusion. Unfortunately, the effects of ketamine on OCD are short-lived and further studies are required to confirm efficacy and optimal dosing.

B. Behavioral

OCD may respond to a variety of behavioral techniques. One common strategy is exposure and response prevention. As in the treatment of simple phobias, exposure and response prevention involves gradually exposing the OCD spectrum patient to situations that the patient fears, such as perceived germs or situations that a hoarder must part with things they are hoarding. By gradually exposing patients to increasingly stressful situations and helping them manage their anxiety without performing the unwanted behavior, OCD spectrum patients are often able to develop some mastery over the behaviors.

C. Psychological

In addition to behavioral techniques, OCD may respond to psychological therapies including cognitive behavioral therapy in which the patient learns to identify maladaptive cognitions associated with obsessive thoughts and challenge those cognitions. For example, a patient with OCD may fear that if he does not wash his hands 50 times after shaking hands, he or someone close to him might develop a serious disease. These cognitions can be identified and gradually replaced with more rational thoughts. A technique used to help quell obsessive thoughts is “thought stopping.” In this technique, the patient is taught to identify an obsessive thought and then to derail it. For example, the patient may be taught to say “STOP” any time an obsessive thought is present. In time, thought stopping can mitigate some of the obsessive thoughts.

D. Social

OCD can have devastating effects on the ability of a patient to lead a normal life. Educating both the patient and family about the course of illness and treatment options is extremely useful in setting appropriate expectations. Severe OCD is commonly associated with vocational disability, and the clinician may sometimes need to facilitate a leave of absence from work or encourage vocational rehabilitation to get the patient back to work.

E. Procedures

Transcranial magnetic stimulation also is effective and FDA-approved for OCD. Psychosurgery has a limited place in selected cases of severe unremitting OCD. Experimental work suggests a role for deep brain stimulation in OCD, and it is FDA approved on a humanitarian device exemption basis for refractory OCD patients.

Prognosis

Prognosis

OCD is usually a chronic disorder with a waxing and waning course. As many as 40% of patients in whom OCD problems develop in childhood will experience remission as adults. However, it is less common for OCD to remit without treatment when it develops during adulthood.

Carmi L et al. Efficacy and safety of deep transcranial magnetic stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a prospective multicenter randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2019 Nov 1;176(11):931–8. [PMID: 31109199]

Hirschtritt ME et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017 Apr 4;317(13):1358–67. [PMID: 28384832]

Rodriguez CI et al. Randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder: proof-of-concept. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013 Nov;38(12):2475–83. [PMID: 23783065]

FEEDING & EATING DISORDERS

See Chapter 29.

SOMATIC SYMPTOM DISORDERS (Abnormal Illness Behaviors)

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Prominent physical symptoms may involve one or more organ systems and are associated with distress, impairment, or both.

Prominent physical symptoms may involve one or more organ systems and are associated with distress, impairment, or both.

Sometimes able to correlate symptom development with psychosocial stresses.

Sometimes able to correlate symptom development with psychosocial stresses.

Combination of biogenetic and developmental patterns.

Combination of biogenetic and developmental patterns.

General Considerations

General Considerations

Any organ system can be affected in somatic symptom disorders. In DSM-5, somatic symptom disorders encompass disorders that were listed under somatic disorders in DSM-IV, including conversion disorder, hypochondriasis, somatization disorder, and pain disorder secondary to psychological factors. Vulnerability in one or more organ systems and exposure to family members with somatization problems plays a major role in the development of particular symptoms, and the “functional” versus “organic” dichotomy is a hindrance to good treatment. Clinicians should suspect psychiatric disorders in a number of conditions. For example, 45% of patients describing palpitations had lifetime psychiatric diagnoses including generalized anxiety, depression, panic, and somatic symptom disorders. Similarly, 33–44% of patients who undergo coronary angiography for chest pain but have negative results have been found to have panic disorder.

In any patient presenting with a condition judged to be somatic symptom disorder, depression must be considered in the diagnosis.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

A. Conversion Disorder (Functional Neurologic Symptom Disorder)

“Conversion” of psychic conflict into physical neurologic symptoms in parts of the body innervated by the sensorimotor system (eg, paralysis, aphonic) is a disorder that commonly occurs concomitantly with panic disorder or depression. The somatic manifestation that takes the place of anxiety is often paralysis, and in some instances the dysfunction may have symbolic meaning (eg, arm paralysis in marked anger so the individual cannot use the arm to strike someone). Nonepileptic seizures can be difficult to differentiate from intoxication states or panic attacks and can occur in patients who also have epileptic seizures. Lack of postictal confusion, closed eyes during the seizure, ictal crying, and a fluctuating course can suggest nonepileptic seizures; some symptoms such as asynchronous movements or pelvic thrusting can occur in both nonepileptic seizures and frontal lobe seizures (see also Chapter 24).

Electroencephalography, particularly in a video-electroencephalography assessment unit, during the attack is the most helpful diagnostic aid in excluding epileptic seizures. A serum prolactin levels rise more than twice baseline abruptly in the postictal state is more likely to be associated with an epileptic seizure. La belle indifférence (an unconcerned affect) is not a significant identifying characteristic, as commonly believed, since individuals even with genuine medical illness may exhibit a high level of denial. It is important to identify physical disorders with unusual presentations (eg, multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus).

B. Somatic Symptom Disorder

Somatic symptom disorder is characterized by one or more somatic symptoms that are associated with significant distress or disability. The somatic symptoms are associated with disproportionate and persistent thoughts about the seriousness of the symptoms, a high level of anxiety about health, or excessive time and energy devoted to these symptoms. The patient’s focus on somatic symptoms is usually chronic. Panic, anxiety, and depression are often present, and major depression is an important consideration in the differential diagnosis. There is a significant relationship (20%) to a lifetime history of panic-agoraphobia-depression. It usually occurs before age 30 and is ten times more common in women. Preoccupation with medical and surgical therapy becomes a lifestyle that may exclude other activities. Patients most often first present to primary care physicians and experience reassurance regarding their physical condition as only briefly helpful or dismissive. Patients’ complaints of symptoms should always be first carefully medically evaluated.

C. Factitious Disorders

These disorders, in which symptom production is intentional, are not somatic symptom conditions in that symptoms are produced consciously, in contrast to the unconscious process of the other somatic symptom disorders. They are characterized by self-induced or described symptoms or false physical and laboratory findings for the purpose of deceiving clinicians or other health care personnel. The deceptions may involve self-mutilation, fever, hemorrhage, hypoglycemia, seizures, and an almost endless variety of manifestations—often presented in an exaggerated and dramatic fashion (Munchausen syndrome). Factitious disorder imposed on another, previously termed Munchausen by proxy, is diagnosed when someone (often a parent) creates an illness in another person (often a child) for perceived psychological benefit of the first person, such as sympathy or a relationship with clinicians. The duplicity may be either simple or extremely complex and difficult to recognize. The patients are frequently connected in some way with the health professions and there is no apparent external motivation other than achieving the patient role. A poor clinician-patient relationship and “doctor shopping” tend to exacerbate the problem.

Complications

Complications

Sedative and analgesic dependency is the most common iatrogenic complication. Patients may pursue medical or surgical treatments that induce iatrogenic problems. Thus, identifying patients with a potential somatic symptom disorder and attempting to limit tests, procedures, and medications that may lead to harm are quite important.

Treatment

Treatment

A. Medical

Medical support with careful attention to building a therapeutic clinician-patient relationship is the mainstay of treatment. It must be accepted that the patient’s distress is real. Every problem not found to have an organic basis is not necessarily a mental disease. Diligent attempts should be made to relate symptoms to adverse developments in the patient’s life. It may be useful to have the patient keep a meticulous diary, paying particular attention to various pertinent factors evident in the history. Regular, frequent, short appointments that are not symptom-contingent may be helpful. Medications (frequently abused) should not be prescribed to replace appointments. One person should be the primary clinician, and consultants should be used mainly for evaluation. An empathic, realistic, optimistic approach must be maintained in the face of the expected ups and downs. Ongoing reevaluation is necessary, since somatization can coexist with a concurrent physical illness.

B. Psychological

The primary clinician can use psychological approaches when it is clear that the patient is ready to make some changes in lifestyle in order to achieve symptomatic relief. This is often best approached with orientation toward pragmatic current changes rather than an exploration of early experiences that the patient frequently fails to relate to current distress. Cognitive behavioral therapy has been shown to be an effective treatment for somatoform disorders by reducing physical symptoms, psychological distress, and disability. Group therapy with other individuals who have similar problems is sometimes of value to improve coping, allow ventilation, and focus on interpersonal adjustment. Hypnosis used early can be helpful in resolving conversion disorders. If the primary clinician has been working with the patient on psychological problems related to the physical illness, the groundwork is often laid for successful psychiatric referral.

For patients who have been identified as having a factitious disorder, early psychiatric consultation is indicated. There are two main treatment strategies for these patients. One consists of a conjoint confrontation of the patient by both the primary clinician and the psychiatrist. The patient’s disorder is portrayed as a cry for help, and psychiatric treatment is recommended. The second approach avoids direct confrontation and attempts to provide a face-saving way to relinquish the symptom without overt disclosure of the disorder’s origin. Techniques such as biofeedback and self-hypnosis may foster recovery using this strategy.

C. Behavioral

Behavioral therapy is probably best exemplified by biofeedback techniques. In biofeedback, the particular abnormality (eg, increased peristalsis) must be recognized and monitored by the patient and therapist (eg, by an electronic stethoscope to amplify the sounds). This is immediate feedback, and after learning to recognize it, the patient can then learn to identify any change thus produced (eg, a decrease in bowel sounds) and so become a conscious originator of the feedback instead of a passive recipient. Relief of the symptom operantly conditions the patient to utilize the maneuver that relieves symptoms (eg, relaxation causing a decrease in bowel sounds). With emphasis on this type of learning, the patient is able to identify symptoms early and initiate the countermaneuvers, thus decreasing the symptomatic problem. Migraine and tension headaches have been particularly responsive to biofeedback methods.

D. Social

Social endeavors include family, work, and other interpersonal activity. Family members should come for some appointments with the patient so they can learn how best to live with the patient. This is particularly important in treatment of somatic and pain disorders. Peer support groups provide a climate for encouraging the patient to accept and live with the problem. Ongoing communication with the employer may be necessary to encourage long-term continued interest in the employee. Employers can become just as discouraged as clinicians in dealing with employees who have chronic problems.

Prognosis

Prognosis

The prognosis is better if the primary clinician intervenes early before the situation has deteriorated. After the problem has crystallized into chronicity, it is more difficult to effect change.

den Boeft M et al. How should we manage adults with persistent unexplained physical symptoms? BMJ. 2017 Feb 8;356:j268. [PMID: 28179237]

Henningsen P. Management of somatic symptom disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018 Mar;20(1):23–31. [PMID: 29946208]

Liu J et al. The efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy in somatoform disorders and medically unexplained physical symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2019 Feb 15;245:98–112. [PMID: 30368076]

CHRONIC PAIN DISORDERS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Chronic complaints of pain.

Chronic complaints of pain.

Symptoms frequently exceed signs.

Symptoms frequently exceed signs.

Minimal relief with standard treatment.

Minimal relief with standard treatment.

History of having seen many clinicians.

History of having seen many clinicians.

Frequent use of several nonspecific medications.

Frequent use of several nonspecific medications.

General Considerations

General Considerations

A problem in the management of pain is the lack of distinction between acute and chronic pain syndromes. Most clinicians are adept at dealing with acute pain problems but face greater challenges in treating a patient with a chronic pain disorder. Patients with chronic pain can frequently take many medications, stay in bed a great deal, have seen many clinicians, have lost skills, and experience little joy in either work or play. Relationships suffer (including those with clinicians), and life becomes a constant search for relief. The search results in complex clinician-patient relationships that usually include many medication trials, particularly sedatives, with adverse consequences (eg, irritability, depressed mood) related to long-term use. Treatment failures can provoke angry responses and depression from both the patient and the clinician, and the pain syndrome is exacerbated. When frustration becomes too great, a new clinician is found, and the cycle is repeated. The longer the existence of the pain disorder, the more important become the psychological factors of anxiety and depression. As with all other conditions, it is counterproductive to speculate about whether the pain is “real.” It is real to the patient, and acceptance of the problem must precede a mutual endeavor to alleviate the disturbance.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

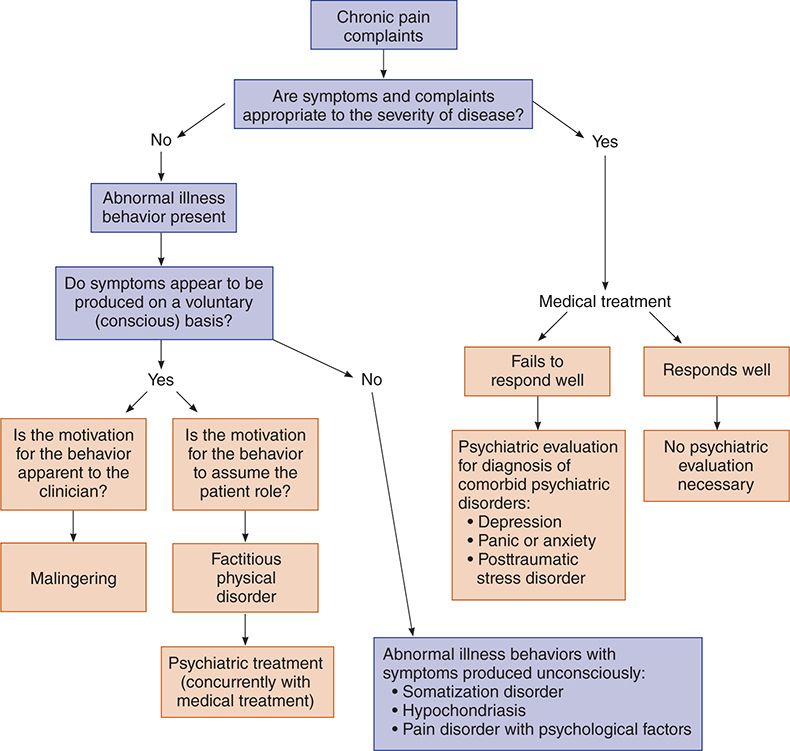

Components of the chronic pain syndrome consist of anatomic changes, chronic anxiety and depression, anger, and changed lifestyle. Usually, the anatomic problem is irreversible, since it has already been subjected to many interventions with increasingly unsatisfactory results. An algorithm for assessing chronic pain and differentiating it from other psychiatric conditions is illustrated in Figure 25–1.

Figure 25–1. Algorithm for assessing psychiatric component of chronic pain. (Adapted and reproduced, with permission, from Eisendrath SJ. Psychiatric aspects of chronic pain. Neurology. 1995 Dec;45(12 Suppl 9):S26–34.)

Chronic anxiety and depression produce heightened irritability and overreaction to stimuli. A marked decrease in pain threshold is apparent. This pattern develops into a preoccupation with the body and a constant need for reassurance. Patients may have started avoiding usual behaviors when they first developed pain, and then chronic avoidance of usual physical functioning can lead to the development of chronic pain. The pressure on the clinician becomes wearing and often leads to covert rejection of the patient, such as not being available or making referrals to other clinicians.

This is perceived by the patient, who then intensifies the effort to find help, and the typical cycle is repeated. Anxiety and depression are seldom discussed, almost as if there is a tacit agreement not to deal with these issues.

Changes in lifestyle involve some of the pain behaviors. These usually take the form of a family script in which the patient accepts the role of being sick, and this role then becomes the focus of most family interactions and may become important in maintaining the family, so that neither the patient nor the family wants the patient’s role to change. Cultural factors frequently play a role in the behavior of the patient and how the significant people around the patient cope with the problem. Some cultures encourage demonstrative behavior, while others value the stoic role.

Another secondary gain that can maintain the patient in the sick role is financial compensation or other benefits. Frequently, such systems are structured so that they reinforce the maintenance of sickness and discourage any attempts to give up the role. Clinicians unwittingly reinforce this role because of the very nature of the practice of medicine, which is to respond to complaints of illness. Helpful suggestions from the clinician are often met with responses like, “Yes, but….” Medications then become the principal approach, and drug dependency problems may develop.

Treatment

Treatment

A. Behavioral

The cornerstone of a unified approach to chronic pain syndromes is a comprehensive behavioral program. This is necessary to identify and eliminate pain reinforcers, to decrease medication use, and to use effectively those positive reinforcers that shift the focus from the pain. It is critical that the patient be made a partner in the effort to manage and function better in the setting of ongoing pain symptoms. The clinician must shift from the idea of biomedical cure to ongoing care of the patient. The patient should agree to discuss the pain only with the clinician and not with family members; this tends to stabilize the patient’s personal life, since the family is usually tired of the subject. At the beginning of treatment, the patient should be assigned self-help tasks graded up to maximal activity as a means of positive reinforcement. The tasks should not exceed capability. The patient can also be asked to keep a self-rating chart to log accomplishments, so that progress can be measured and remembered. Instruct the patient to record degrees of pain on a self-rating scale in relation to various situations and mental attitudes so that similar circumstances can be avoided or modified.

Avoid positive reinforcers for pain such as marked sympathy and attention to pain. Emphasize a positive response to productive activities, which remove the focus of attention from the pain. Activity is also desensitizing, since the patient learns to tolerate increasing activity levels.

Biofeedback techniques (see Somatic Symptom Disorders, above) and hypnosis have been successful in ameliorating some pain syndromes. Hypnosis tends to be most effective in patients with a high level of denial, who are more responsive to suggestion. Hypnosis can be used to lessen anxiety, alter perception of the length of time that pain is experienced, and encourage relaxation. Mindfulness-based stress reduction programs have been useful in helping individuals develop an enhanced capacity to live a higher quality life with persistent pain.

B. Medical

A single clinician in charge of the comprehensive treatment approach is the highest priority. Consultations as indicated and technical procedures done by others are appropriate, but the care of the patient should remain in the hands of the primary clinician. Referrals should not be allowed to raise the patient’s hopes unrealistically or to become a way for the clinician to reject the case. The attitude of the clinician should be one of honesty, interest, and hopefulness—not for a cure but for control of pain and improved function. If the patient manifests opioid addiction, detoxification may be an early treatment goal.

Medical management of chronic pain is addressed in Chapter 5. The harms of opioids generally outweigh the benefits in chronic pain management. A fixed schedule lessens the conditioning effects of these medications. SNRIs (eg, venlafaxine, milnacipran, and duloxetine) and TCAs (eg, nortriptyline) in doses up to those used in depression may be helpful, particularly in neuropathic pain syndromes. Both duloxetine and milnacipran are approved for the treatment of fibromyalgia; duloxetine is also indicated in chronic pain conditions. In general, the SNRIs tend to be safer in overdose than the TCAs (although venlafaxine may be more arrhythmogenic in overdose than other SRNIs but less than TCAs); suicidality is often an important consideration in treating patients with chronic pain syndromes. Gabapentin and pregabalin, anticonvulsants with possible applications in the treatment of anxiety disorders, have been shown to be useful in neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia.

In addition to medications, a variety of nonpharmacologic strategies may be offered, including physical therapy and acupuncture.

C. Social

Involvement of family members and other significant persons in the patient’s life should be an early priority. The best efforts of both patient and therapists can be unwittingly sabotaged by other persons who may feel that they are “helping” the patient. They frequently tend to reinforce the negative aspects of the chronic pain disorder. The patient becomes more dependent and less active, and the pain syndrome becomes an immutable way of life. The more destructive pain behaviors described by many experts in chronic pain disorders are the results of well-meaning but misguided efforts of family members. Ongoing therapy with the family can be helpful in the early identification and elimination of these behavior patterns.

D. Psychological

In addition to group therapy with family members and others, groups of patients can be helpful if properly led. The major goal, whether of individual or group therapy, is to gain patient involvement. A group can be a powerful instrument for achieving this goal, with the development of group loyalties and cooperation. People will frequently make efforts with group encouragement that they would never make alone. Individual therapy should be directed toward strengthening existing coping mechanisms and improving self-esteem. For example, teaching patients to challenge expectations induced by chronic pain may lead to improved functioning. As an illustration, many chronic pain patients, making assumptions more derived from acute injuries, incorrectly believe they will damage themselves by attempting to function. The rapport between patient and clinician, as in all psychotherapeutic efforts, is the major factor in therapeutic success.

Busse JW et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ. 2017 May 8;189(18):E659–66. [PMID: 28483845]

Markozannes G et al. An umbrella review of the literature on the effectiveness of psychological interventions for pain reduction. BMC Psychol. 2017 Aug 31;5(1):31. [PMID: 28859685]

Urits I et al. Off-label antidepressant use for treatment and management of chronic pain: evolving understanding and comprehensive review. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2019 Jul 29;23(9):66. [PMID: 31359175]

PSYCHOSEXUAL DISORDERS

The stages of sexual activity include excitement (arousal), orgasm, and resolution. The precipitating excitement or arousal is psychologically determined. Arousal response leading to orgasm is a physiologic and psychological phenomenon of vasocongestion, a parasympathetic reaction causing erection in men and labial-clitoral congestion in women. The orgasmic response includes emission in men and clonic contractions of the analogous striated perineal muscles of both men and women. Resolution is a gradual return to normal physiologic status.

While the arousal stimuli—vasocongestive and orgasmic responses—constitute a single response in a well-adjusted person, they can be considered as separate stages that can produce different syndromes responding to different treatment procedures.

Clinical Findings

Clinical Findings

There are three major groups of sexual disorders.

A. Paraphilias

In these conditions, formerly called “deviations” or “variations,” the excitement stage of sexual activity is associated with sexual objects or orientations different from those usually associated with adult sexual stimulation. The stimulus may be a woman’s shoe, a child, animals, instruments of torture, or incidents of aggression. The pattern of sexual stimulation is usually one that has early psychological roots. When paraphilias are associated with distress, impairment, or risk of harm, they become paraphilic disorders. Some paraphilias or paraphilic disorders include exhibitionism, transvestism, voyeurism, pedophilia, incest, sexual sadism, and sexual masochism.

B. Gender Dysphoria

Gender dysphoria is distress associated with the incongruence between one’s experienced or expressed gender and one’s assigned gender. As a disorder, it is defined by significant distress or impairment; those experiencing this incongruence but without the distress would not meet criteria for having gender dysphoria. Screening should be done for conditions related to the oppression and stigmatization that transgender people face, including a high risk of suicide.

C. Sexual Dysfunctions

This category includes a large group of vasocongestive and orgasmic disorders. Often, they involve problems of sexual adaptation, education, and technique that are often initially discussed with, diagnosed by, and treated by the primary care provider.

There are two conditions common in men: erectile dysfunction and ejaculation disturbances.

Erectile dysfunction is inability to achieve or maintain an erection firm enough for satisfactory intercourse; patients sometimes use the term incorrectly to mean premature ejaculation. Decreased nocturnal penile tumescence occurs in some depressed patients. Psychological erectile dysfunction is caused by interpersonal or intrapsychic factors (eg, partner disharmony, depression). Organic factors are discussed in Chapter 23.

Ejaculation disturbances include premature ejaculation, inability to ejaculate, and retrograde ejaculation. (Ejaculation is possible in patients with erectile dysfunction.) Ejaculation is usually connected with orgasm, and ejaculatory control is an acquired behavior that is minimal in adolescence and increases with experience. Pathogenic factors are those that interfere with learning control, most frequently sexual ignorance. Intrapsychic factors (anxiety, guilt, depression) and interpersonal maladaptation (partner problems, unresponsiveness of mate, power struggles) are also common. Organic causes include interference with sympathetic nerve distribution (often due to surgery or radiation) and the effects of pharmacologic agents (eg, SSRIs or sympatholytics).

In women, the most common forms of sexual dysfunction are orgasmic disorder and hypoactive sexual desire disorder.

Orgasmic disorder is a complex condition in which there is a general lack of sexual responsiveness. The woman has difficulty in experiencing erotic sensation and does not have the vasocongestive response. Sexual activity varies from active avoidance of sex to an occasional orgasm. Orgasmic dysfunction—in which a woman has a vasocongestive response but varying degrees of difficulty in reaching orgasm—is sometimes differentiated from anorgasmia. Causes for the dysfunctions include poor sexual techniques, early traumatic sexual experiences, interpersonal disharmony (partner struggles, use of sex as a means of control), and intrapsychic problems (anxiety, fear, guilt). Organic causes include any conditions that might cause pain in intercourse, pelvic pathology, mechanical obstruction, and neurologic deficits.

Hypoactive sexual desire disorder consists of diminished or absent libido in either sex and may be a function of organic or psychological difficulties (eg, anxiety, phobic avoidance). Any chronic illness can reduce desire as can aging. Hormonal disorders, including hypogonadism or use of antiandrogen compounds such as cyproterone acetate, and chronic kidney disease contribute to deterioration in sexual desire. Alcohol, sedatives, opioids, marijuana, and some medications may affect sexual drive and performance. Menopause may lead to diminution of sexual desire in some women, and testosterone therapy is sometimes warranted as treatment.

Treatment

Treatment

A. Paraphilias

1. Psychological—Paraphilias, particularly those of a more superficial nature (eg, voyeurism) and those of recent onset, are responsive to psychotherapy in some cases. The prognosis is much better if the motivation comes from the individual rather than the legal system; unfortunately, judicial intervention is frequently the only stimulus to treatment because the condition persists and is reinforced until conflict with the law occurs. Therapies frequently focus on barriers to normal arousal response; the expectation is that the variant behavior will decrease as normal behavior increases.

2. Behavioral—In some cases, paraphilic disorders improve with modeling, role-playing, and conditioning procedures.

3. Social—Although they do not produce a change in sexual arousal patterns or gender role, self-help groups have facilitated adjustment to an often hostile society. Attention to the family is particularly important in helping people in such groups to accept their situation and alleviate their guilt about the role they think they had in creating the problem.

4. Pharmacologic—Medroxyprogesterone acetate, a suppressor of libidinal drive, can be used to mute disruptive sexual behavior in men. Onset of action is usually within 3 weeks, and the effects are generally reversible. Fluoxetine or other SSRIs at depression doses may reduce some of the compulsive sexual behaviors including the paraphilias. A focus of study in the treatment of severe paraphilia has been agonists of luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LHRH). Case reports and open label studies suggest that LHRH-agonists may play a role in preventing relapse in some patients with paraphilia.

B. Gender Dysphoria

1. Psychological—Individuals with gender dysphoria often find benefit from psychotherapy, providing them with a safe place to explore and understand their thoughts and feelings, and to identify their own specific needs and desires and adjust to a changing life.

2. Social—Peer support groups, parent psychoeducation and support, and community empowerment are important social components of treatment.

3. Medical—Some individuals with gender dysphoria choose to pursue surgery or hormone therapy or both. Most recommendations prior to surgery include that the individual spends significant time prior living as their desired gender. Rates of suicide fall significantly after surgery but still remain much higher than the general population.

C. Sexual Dysfunction

1. Psychological—The use of psychotherapy by itself is best suited for those cases in which interpersonal difficulties or intrapsychic problems predominate. Anxiety and guilt about parental injunctions against sex may contribute to sexual dysfunction. Even in these cases, however, a combined behavioral-psychological approach usually produces results most quickly.

2. Behavioral—Syndromes resulting from conditioned responses have been treated by conditioning techniques, with excellent results. Masters and Johnson have used behavioral approaches in all of the sexual dysfunctions, with concomitant supportive psychotherapy and with improvement of the communication patterns of the couple.

3. Social—The proximity of other people (eg, a mother-in-law) in a household is frequently an inhibiting factor in sexual relationships. In such cases, some social engineering may alleviate the problem.

4. Medical—Even if the condition is not reversible, identification of the specific cause helps the patient to accept the condition. Partner disharmony, with its exacerbating effects, may thus be avoided. Of all the sexual dysfunctions, erectile dysfunction is the condition most likely to have an organic basis. Sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil are phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors that are effective oral agents for the treatment of penile erectile dysfunction (eg, sildenafil 25–100 mg orally 1 hour prior to intercourse). These agents are effective for SSRI-induced erectile dysfunction in men and in some cases for SSRI-associated sexual dysfunction in women. Use of the medications in conjunction with any nitrates can have significant hypotensive effects leading to death in rare cases. Because of their common effect in delaying ejaculation, the SSRIs have been effective in premature ejaculation.

Flibanserin is a 5-HT1A-agonist/5-HT2-antagonist that is FDA approved for the treatment of female hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Women treated with flibanserin have a marginally higher number of sexual events. The medication interacts with alcohol, causing hypotensive events, so patients need to be educated about this risk. Flibanserin is taken 100 mg orally at bedtime to circumvent the side effects of dizziness, sleepiness, and nausea.

In addition to flibanserin, a second medication was approved by the FDA in 2019 for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women. Bremelanotide activates melanocortin receptors, although the mechanism of action in hypoactive sexual desire disorder is unclear. It is self-administered by injection to the thigh or abdomen about 45 minutes before anticipated sexual activity. In the registration trials, about 25% of women had a clinically significant increase in libido compared to 17% of controls. While the response rates appear low, bremelanotide was generally well tolerated and does represent another option for some women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder.

Dhillon S et al. Bremelanotide: first approval. Drugs. 2019 Sep;79(14):1599–606. [PMID: 31429064]

Hadj-Moussa M et al. Evaluation and treatment of gender dysphoria to prepare for gender confirmation surgery. Sex Med Rev. 2018 Oct;6(4):607–17. [PMID: 29891226]

PERSONALITY DISORDERS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Long history dating back to childhood.

Long history dating back to childhood.

Recurrent maladaptive behavior.

Recurrent maladaptive behavior.

Difficulties with interpersonal relationships or society.

Difficulties with interpersonal relationships or society.

Depression with anxiety when maladaptive behavior fails.

Depression with anxiety when maladaptive behavior fails.

General Considerations

General Considerations

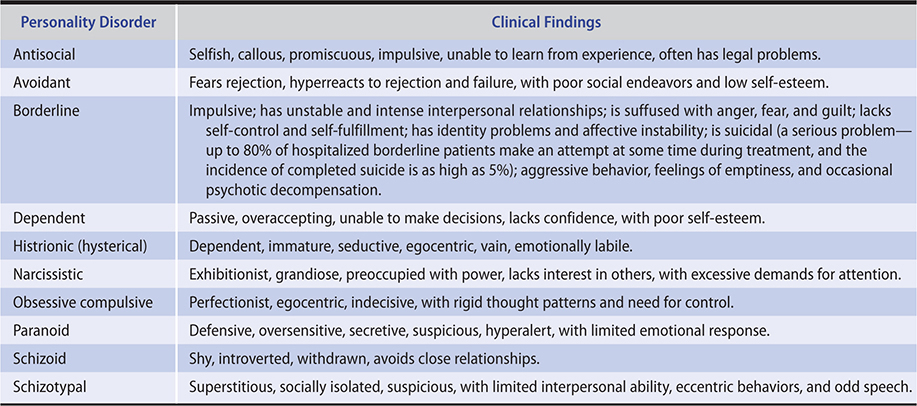

An individual’s personality structure, or character, is an integral part of self-image. It reflects genetics, interpersonal influences, and recurring patterns of behavior adopted to cope with the environment. The classification of subtypes of personality disorders depends on the predominant symptoms and their severity. The most severe disorders—those that bring the patient into greatest conflict with society—tend to be antisocial (psychopathic) or borderline.

Classification & Clinical Findings

Classification & Clinical Findings

See Table 25–3.

Table 25–3. Personality disorders: Classification and clinical findings (listed in alphabetical order).

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Patients with personality disorders tend to experience anxiety and depression when pathologic coping mechanisms fail and may first seek treatment when this occurs. Occasionally, the more severe cases may decompensate into psychosis under stress and mimic other psychotic disorders.

Treatment

Treatment

A. Social

Social and therapeutic environments such as day hospitals, halfway houses, and self-help communities utilize peer “pressure” to modify the self-destructive behavior. The patient with a personality disorder often has failed to profit from experience, and difficulties with authority can impair the learning experience. The use of peer relationships and the repetition possible in a structured setting of a helpful community enhance the behavioral treatment opportunities and increase learning. When problems are detected early, both the school and the home can serve as foci of intensified social pressure to change the behavior, particularly with the use of behavioral techniques.

B. Behavioral

The behavioral techniques used are principally operant conditioning and aversive conditioning. The former simply emphasizes the recognition of acceptable behavior and its reinforcement with praise or other tangible rewards. Aversive responses usually mean punishment, although this can range from a mild rebuke to some specific punitive responses such as deprivation of privileges. Extinction plays a role in that an attempt is made not to respond to inappropriate behavior, and the lack of response eventually causes the person to abandon that type of behavior. Pouting and tantrums, for example, diminish quickly when such behavior elicits no reaction. These traits are less likely to develop in children at risk for development of antisocial tendencies due to a genetic predisposition when they are given positive reinforcement for positive behaviors. Dialectical behavioral therapy is a program of individual and group therapy specifically designed for patients with chronic suicidality and borderline personality disorder. It blends mindfulness and a cognitive-behavioral model to address self-awareness, interpersonal functioning, affective lability, and reactions to stress. Psychodynamic psychotherapy can also be an effective treatment.

C. Psychological

Psychological interventions can be conducted in group and individual settings. Group therapy is helpful when specific interpersonal behavior needs to be improved. This mode of treatment also has a place with so-called “acting-out” patients, ie, those who frequently act in an impulsive and inappropriate way. The peer pressure in the group tends to impose restraints on rash behavior. The group also quickly identifies the patient’s types of behavior and helps improve the validity of the patient’s self-assessment, so that the antecedents of the unacceptable behavior can be effectively handled, thus decreasing its frequency. Individual therapy should initially be supportive, ie, helping the patient to restabilize and mobilize coping mechanisms. If the individual has the ability to observe his or her own behavior, a longer-term and more introspective therapy may be warranted. The therapist must be able to handle countertransference feelings (which are frequently negative), maintain appropriate boundaries in the relationship, and refrain from premature confrontations and interpretations.

D. Pharmacologic