baba au rhum is a rum-saturated, yeast-leavened cake that is as soaked in legend as it is in boozy syrup. The name comes from the Slavic term for “old lady” and has been used by Czechs and Poles for a variety of sweet, mold-baked preparations since at least the Middle Ages. At some point before the eighteenth century, the term also became a synonym for Gugelhupf. See gugelhupf . The Nouveau grand dictionnaire françois, latin et polonois et sa place dans la lexicographie polonaise (1743) defines a “baba ciasta” (dough baba) as a yellow cake (gâteau). In France, the word was adopted for just such a saffron-tinted pastry sometime in the eighteenth century, presumably due to the influence of exiled Polish king Stanisław Leszczyński or his daughter Marie Leszczyńska, the queen consort of Louis XV.

Numerous fanciful tales recount Leszczyński’s participation in the genesis of the yeasty cake. Some credit him personally with inventing it while in residence in Lorraine in the 1710s, whereas others assign the innovation to his pastry chef Nicolas Stohrer. See stohrer, nicolas. According to one story, the king was reading the newly translated One Thousand and One Nights and spilled some fortified wine on his slice of Gugelhupf. He is supposed to have named this new creation “baba” after the Ali Baba of one of the tales. According to another story, it was Leszczyński’s young pastry cook who came up with the idea of soaking the cake in a rum syrup. The trouble with both tales is that soaking the pastry was not part of the recipe until the nineteenth century. As late as 1808, the French food writer Grimod de La Reynière noted that “the principal flavoring of the baba is saffron and Corinth raisins [dry currants].” Contemporary cookbooks confirm that the cake was little different from a Gugelhupf at this point.

Although Leszczyński most certainly did not invent the Gugelhupf—a common enough pastry throughout Central Europe—it is highly plausible that either he or his daughter popularized the idea of snacking on the yeasty cake at Versailles when the 22-year-old princess married the 15-year-old French king in 1725. Certainly, the Polish name would have been easier than its German counterpart for the French courtiers to pronounce.

Just when the rum syrup was added is a little unclear. References to “baba au rhum” begin to crop up only in the 1840s. Ever since, the ring-shaped, rum-syrup-soaked cake has become firmly rooted in the French pastry repertoire.

Curiously, it was in Naples rather than in France that the baba became a regional icon. As in the rest of Europe, French cooking was all the rage in nineteenth-century Naples, and no self-respecting aristocratic kitchen was complete without its monsù or French chef. Consequently all sorts of French tarts, crèmes, and gâteaux were commonly served in the palazzi, and many French techniques came to be adopted by Neapolitan pasticcieri. Of all the sweet Gallic imports, none came to be as loved as the baba, now often presented in the form of a mushroom-shaped single serving, split and filled with pastry cream. Today, the baba is vastly more popular in Naples (and in Italian American pastry shops in the United States) than in France. Neapolitans are so fond of the dessert that the name is used as a term of endearment. “Si nu’ baba” (you are a baba) roughly means “you’re the real deal.” It can also mean “you’re hot stuff,” if your intentions are less platonic.

Baghdad, today’s capital of Iraq, was founded by the Abbasids in 762 c.e. Built on the ruins of an ancient Mesopotamian city dating back to around 2000 b.c.e., Baghdad was a thriving trade center strategically located at the crossroads of the Eastern and Western cultures of Persia, Greece, and Rome.

Baghdad rapidly flourished under Abbasid rule. To meet an increasing demand for spices and other luxury merchandise, traders ventured to places as distant as China. Between the eighth and thirteenth centuries, Baghdad grew into the hub of a medieval Islamic world renowned for a remarkably diverse culinary repertoire. It drew directly on the Arabs’ native heritage and on Iraq’s indigenous foodways, and indirectly on Persian practice, which had refined these traditions throughout several centuries of dominance. Active international trade introduced foreign elements, and slave girls proficient in the art of cooking were in high demand.

The Evolution of Baghdad’s Medieval Sweets

The cultivation of ingredients such as sesame, wheat, and dates from ancient times helped nurture a sweets-loving culture in the region well before the foundation of Abbasid Baghdad. Fragments of cuneiform tablets of fruitcake recipes and other records show that making pastries and confections was already a thriving business in the region, and desserts were consumed in large amounts during the religious festivals. Among these sweets were date-filled, rosewater-infused cookies (qullupu), date halvah (mirsu), and muttaqu, a flour-based pudding. See halvah.

The only culinary source surviving from the following era of Persian presence in the region, the fourth-century Sassanian book King Khosrau and His Page, mentions almond and walnut candy (lauzenak and guzenak) as well as faludhaj, a starch pudding made with fruit juice, butter, and honey. The Arabs themselves were familiar from pre-Islamic times with sweetmeats of dates mashed with toasted flour and clarified butter, and the affluent relished the translucent faludhaj.

The cultivation and processing of sugarcane, begun in the southern regions of Iraq and Persia by the sixth century c.e., contributed to the creativity of cooks to meet the demands of the newly wealthy leisure class of the Abbasid era. Islam was not against such indulgences, since sensual delight in eating was considered legitimate. Good food, after all, was one of the promised pleasures of Paradise. Moreover, dessert, with its hot properties, was believed to aid digestion when consumed after meals. Still, in the heat of summer, connoisseurs preferred to have their crêpe-like qatayif, fresh dates, and honeycomb served on crushed ice.

Dignitaries of all ranks joined professional cooks and poets in creating gourmet dishes and writing about food, both in cookbooks and in gastronomic poetry. The caliphs loved participating in cooking contests and delighted in listening to poems about food, such as one by the famous poet Kushajim (d. 961), who described lusciously made nāṭif (nougat): “like solid silver it looks, but soft and sweet as lips it tastes.” See nougat. The story of “The Porter and the Three Ladies of Baghdad” from The Arabian Nights details a “shopping list” with more than 20 sweet items, imported and local, including Lebanese malban (chewy starch candy), sultanas from Yemen, and all kinds of cookies and sticky fried pastries. This was by no means fictitious fodder; a repertoire of over 100 dessert recipes has survived in al-Warraq’s and al-Baghdadi’s tenth- and thirteenth-century cookbooks, respectively, both titled Kitāb al-Ṭabīkh.

Baghdadi cooks were spoiled as to the varieties of sugar at their disposal. The best all-purpose white sugar was sukkar ṭabarzad (chiseled sugar-cone). Less-refined qand was shaped into small balls and sticks, a delicacy to nibble at the table. Powdered sugar was generously sprinkled on desserts, while unrefined crystallized brown sugar was used only for baking cookies like kaʿk. The purest sugar was crystal-clear sukkar nabat (rock candy), eaten as candy but also crushed to decorate desserts. Sukkar Sulaymāni was a hard candy made from white sugar boiled into a thick syrup, then beaten until crystallized and shaped into discs, rings, or fingers. See candy. Molasses was also produced, though it was deemed inferior to honey. Fried pastries were commonly submerged in honey or jullab, a rosewater-infused sugar syrup.

Honey was more extensively used than sugar for making jams (murabbayat) and pastes. See fruit preserves and honey. Although the main purpose of these preserves was to aid digestion, cure simple aches and pains, or invigorate coitus, they were often enjoyed as sweets. Most were locally made from rose petals, citron peel, quince, apple, dates, dried ginger root, and even celery, carrots, and radish, though mango jam imported from India was very popular.

Light milk-puddings (muhallabiyyat) were thickened with wheat starch, rice flour, or itriya (fine noodles). Thicker puddings like khabīs and faludhaj were made with wheat starch, rice flour, or crushed almonds, and sometimes with pureed carrots, melon, apples, or quince. Sweetened with honey, they were spread on flat platters and copiously sprinkled with powdered sugar; for festive events, they were often decorated with elaborate domes of honey taffy, colored almonds, and sugar candy. Hospitality was gauged by how much faludhaj was served for dessert, and no wedding was deemed complete without it.

The latticed fritters zalabiya mushabbak, fried in sesame oil and drenched in honey, were a Baghdad specialty, beautifully described by the Abbasid poet Ibn al-Rumi (d. 896):

I saw him at the crack of dawn frying zalabiya,

Tubes of reed, delicate, and thin. The oil I saw

Boiling in his pan was like hitherto elusive alchemy.

The batter he threw into the pan looking like silver,

Would instantly transform into lattices of gold.

See zalabiya. An unusual sweet called barad (hailstones) was made by binding tiny balls of crisp fried pastry with cooked honey, not unlike today’s Rice Krispies squares. Spongy, delicate cakes with and without eggs, called furniyya and safanj, were baked in the tannour, a clay oven, or steamed in special pots. Milk and clarified butter were poured over the inverted cakes, which were given a final sprinkle of powdered sugar and black pepper. The brittle double-crusted honey pie basīsa was baked in the commercial oven for controlled heat. Basketfuls of kaʿk (delicate cookies), luxuriously perfumed with rosewater, ambergris, camphor, mastic, and musk, were sent as favors and distributed during religious festivals. The nut- and date-filled cookies called khushkananaj marked the end of religious festivals.

A popular street food was sweet-savory judhaba—many thin layers of bread spread in a shallow pan, sprinkled with sugar and nuts, drenched in syrup and sesame oil or chicken fat, then baked in the tannour with a chunk of meat suspended above it. The bread was served with the thinly sliced meat, with the sweet component deemed necessary to aid digestion of the meat. Quite possibly this complex dish was an early inspiration for the Ottoman baklava and Moroccan bistilla.

Although Baghdad had much to indulge in, food was not cheap. Making desserts was labor intensive and expensive, so people with limited means satisfied their cravings by purchasing a handful of fanīd (pulled taffy) from hawkers or buying sweets at the confectioners’ market, where they were not always of top quality (people with deceptive appearances were often compared to second-rate faludhaj purchased from the marketplace). From extant market inspection books we learn that it was common to adulterate honey with grape molasses, to make cookies with flour debased with ground lentil or sesame hull, or to drench zalabiya in cane-sugar syrup rather than the more desirable bees’ honey. See adulteration. While the poor ate cheap dates and date syrup, the affluent enjoyed refined sugars and honey, sucked on crystal-clear rock candy, and chewed on small sticks of peeled sugarcane infused with rosewater. Only a few times a year were the have-nots given a taste of luxury—mainly on grand occasions like religious or public feasts.

The Heritage of Baghdad’s Medieval Sweets

The sweet legacy of medieval Baghdad spread far in place and time, to the medieval Levant, Egypt, Morocco, and Andalusia, and even beyond Muslim territories. But the Mongol invasion of 1258 eclipsed Baghdad’s star, and with the rise of the Ottoman Empire the limelight shifted to Istanbul. Even so, many Abbasid desserts were incorporated into Ottoman kitchens, for which Arab cooks were often hired. The first Turkish cookbook, Muhammed Shirvani’s fifteenth-century Kitabu’t-Tabīh, was based on his translation of al-Baghdadi’s thirteenth-century Kitāb al- ṭabīkh.

By the fall of the Ottoman Empire in 1918, life in Baghdad was characterized by religious and ethnic diversity. Most of the traditional desserts persisted, especially at social gatherings and dinner parties. Today, a small box of baklava and zalabiya makes a handsome gift for a birthday party or circumcision, and trays full of them are served at weddings. In the heat of summer, Baghdadis enjoy chilled puddings, drinks, and ice cream. A typically Baghdadi sweet breakfast treat is kahi, thin sheets of dough generously brushed with oil, folded into squares, and baked. Kahi is served warm with light syrup and a scoop of clotted cream.

Various candies, such as ḥalqīm (Turkish delight), simsimiyya (a chewy candy of date syrup and tahini encrusted with toasted sesame seeds), and diamond-shaped lauzīna, are displayed in small bazaar shops and sold by hawkers. A distinctly Iraqi candy is the exotic mann il-sima (heaven-sent manna), whose main ingredient, manna, is harvested in the north of Iraq. See manna. It is enjoyed all year round, but the Chaldean Christians particularly offer it for their spring festival Khidr Elias. Up until the 1950s when there was still a thriving Jewish community in Baghdad, the confectioners among them were considered the best at making it. Also favored by Baghdad Jews for Purim was an unusual candy called khirret, made with pollen of cattail (Typha spp.) in the southern marshes of Iraq. See judaism. A common scene at Muslim holy shrines is that of women whose prayers have been answered showering visitors with an assortment of hard candies as they ululate shrilly.

Since the early 1990s, Iraq has been going through very harsh times, and the difficult economic conditions have made sweets a luxury beyond the reach of most people. Prices have skyrocketed and good-quality ingredients are hard to find. But sweets are so deeply ingrained in Iraqi culture that they are hard to abandon. An Iraqi newspaper interview about festive Muslim customs quoted one man as saying, “But can any of us husbands persuade the wife not to make kleicha [date and nut cookies] in these difficult times? I doubt it!”

See also dates; flower waters; middle east; pudding; pulled sugar; and ramadan.

Baked Alaska is a trick dessert that consists of frozen ice cream on a sponge cake base, encased by hot meringue. See meringue and sponge cake. The insulating properties of the air in the sponge cake and the meringue make it possible to deliver hot and cold temperatures in the same dish.

The origins of Baked Alaska are obscure. Baron Brisse (Léon Brisse), in his daily food column for the French newspaper La Liberté in 1866, told readers of a visit by the Chinese emperor to Paris, during which his chefs demonstrated for their French counterparts a dessert known in China “since time immemorial.” It consisted of ginger-accented vanilla ice cream baked in a pastry crust. The ice cream and meringue dessert known as omelette norvégienne, or Norwegian omelet, entered the French culinary repertoire in the 1890s.

In the United States, the dessert is associated with Delmonico’s restaurant in New York City, where Charles Ranhofer created a hot frozen dish called “Alaska Florida.” Many sources state it as fact, but without evidence, that he created the dessert in 1867 to celebrate the American government’s purchase of Alaska that year.

In America Revisited (1882), the British journalist Charles Augustus Sala described eating an “Alaska” at Delmonico’s, with more enthusiasm than accuracy—he mistook the meringue for whipped cream. “The nucleus or core of the entremet is an ice cream,” he wrote. “This is surrounded by an envelope of carefully whipped cream [sic], which, just before the dainty dish is served, is popped into the oven, or is brought under the scorching influence of a red hot salamander; so that its surface is covered with a light brown crust. So you go on discussing the warm cream soufflé till you come, with somewhat painful suddenness, on the row of ice” (Vol. 1, p. 90).

Ranhofer included his dessert in his massive cookbook The Epicurean (1894). The recipe calls for vanilla and banana ice cream and for the sponge base to be filled with apricot marmalade. Baked Alaska first appeared under that name in the first edition of The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book by Fannie Merritt Farmer in 1896. Constantly rediscovered, it reached peak popularity in the 1950s, enjoyed a revival in the 1970s, and, after the turn of the millennium, began attracting a fresh wave of admirers in search of a showpiece dessert.

See also ice cream.

Baker’s is an American brand of chocolate primarily associated with home baking. The modest place it occupies in today’s supermarket with its semisweet, unsweetened, and German’s line of baking chocolate belies the company’s pivotal role in inspiring Americans to make chocolate desserts in the first place. Originally, Baker’s chocolate was not made for baking. The company was established by James Baker in Dorchester, Massachusetts, in 1765. At first, the Walter Baker Company, as it came to be known after the founder’s grandson, manufactured tablets of drinking chocolate. They sold it locally, subsequently expanding their market across the East Coast and then nationally when, in 1869, the Transcontinental Railroad made it possible to ship the chocolate to every major American city. Prior to 1865, Baker’s sold three grades of drinking chocolate: “Best Chocolate,” “Common Chocolate,” and a low-quality “Inferior Chocolate” supplied mainly to American and West Indian slaves.

Baker’s vastly expanded its market share under the leadership of Henry Pierce (1825–1896), who assumed control of the company in 1854. Having briefly worked at a midwestern newspaper, Pierce knew the power of advertising firsthand. Consequently, once the Civil War was over, he invested heavily in promoting the brand, often using images of an attractive European waitress known as “La Belle Chocolatière,” based on a pastel by Jean-Étienne Liotard. By 1872 Baker’s was running ads in over 150 regional papers; a decade later this number had increased to over 530, and by 1896 Baker’s was reaching readers in some 8,000 newspapers nationwide. In an early version of saturation marketing, Pierce also bought full-page ads in the back of some 6 million novels and placed posters in streetcars, billboards along train routes, and cards and signs in grocery stores. At first, the company’s chocolate was touted as a wholesome, family beverage, but eventually Baker’s started promoting the idea of chocolate as a dessert ingredient.

Since women were not accustomed to baking with chocolate, they needed instruction. This tutelage came first in the form of recipe booklets and then in full-fledged cookbooks. In 1893 the company hired celebrity cooking instructor Maria Parloa of the famed Boston Cooking School to write several Baker’s cookbooks. In 1898, when Parloa protégé Fannie Farmer penned the Boston Cooking School Cookbook, it contained 16 chocolate desserts—specifying Baker’s brand chocolate in every one.

By 1897 the recently incorporated company was sold to a conglomerate of Boston capitalists headed by John Malcolm Forbes. It changed hands once again in 1927, when it was acquired by Postum (later named General Foods). Phillip Morris bought the company in 1985, and it finally spun off as a division of Mondelēz International in 2012. In 1965 the storied New England company moved to Dover, Delaware. The old Baker’s buildings in Dorchester have been converted to luxury apartments.

See also cocoa.

baker’s dozen, a phrase that denotes a cluster of 13 items, was first recorded in a pamphlet titled Have with You to Saffron-Walden, published by Thomas Nashe in 1596. According to John Hotten’s Slang Dictionary of 1864, the phrase arose from bakers’ practice of providing an additional free loaf whenever a customer bought 12 loaves, in case the loaves were underweight. The penalties for selling underweight bread were indeed severe (ranging from fines, to the destruction of the baker’s oven, to the pillory), and in England they dated back to a thirteenth-century statute known as the Assize of Bread and Ale. However, Hotten’s commonly cited explanation is probably incorrect.

Instead, the phrase “baker’s dozen” likely arose from the practice of bakers giving extra loaves to “hucksters,” that is, to peddlers who sold the bread in the street. Because the price of a loaf was fixed by the Assize of Bread and Ale, the hucksters could not charge more for the loaves than what they had paid the bakers. This meant that they could make a profit only if the bakers gave them a free loaf; the bakers were happy to comply, because they could sell more bread to the hucksters who roamed the streets than they could by remaining at their stalls to sell their own bread. This free thirteenth loaf was called the “vantage loaf” (first recorded in 1612, and so named because it gave the huckster an advantage) or “inbread” (first recorded in 1639, and so named because the extra loaf was “thrown in” by the baker). In the early nineteenth century, a baker’s dozen also came to be known as a “devil’s dozen” because of the sinister associations of the number 13.

baklava is a many-layered pastry, soaked in syrup, that is made in central and western Asia and parts of the Balkans, in countries ranging from Greece to Uzbekistan and Turkey to Egypt. The most common type of baklava consists of 40 to 80 layers of tissue-thin filo, moistened with melted butter before baking, and soaked with hot syrup after baking. See filo. It is usually filled with nuts, the most common being walnuts or almonds. In Turkey, fillings also include fresh cheese and a custard made of milk thickened with starch or semolina. Other examples of regional variations are cinnamon added to the nuts in Greece, and cardamom or rosewater to the syrup in Iran. See flower waters. Baklava is usually cut into small lozenges. Variations are made by rolling or folding the pastry sheets into diverse shapes, known in Turkey as dilberdudağı (beauty’s lips), sarığıburma (twisted turban), bülbülyuvası (nightingale’s nest), vezirparmağı (vizier’s finger), and gül baklava (rose baklava). Sugar syrup is used in Turkey and the Middle East, although honey syrup and boiled grape juice were common in the past when sugar was a luxury for ordinary people. See pekmez. In Greece, honey is sometimes added to the syrup. To make the filo sheets, dough is either rolled in individual pieces or first rolled into small circles, next stacked 10 at a time, with starch sprinkled between each layer; then the whole pile is rolled out simultaneously. The latter method is often used by both professional and home cooks and is easier for the inexperienced baker. Although few city dwellers make their own baklava today, homemade baklava is still widely produced in provincial Turkish towns.

Baklava filled with fresh cheese is always eaten hot (like the cheese-filled kunāfa of the Levant). In the past, cheese was a common baklava filling in Istanbul, but it survives today only in the provincial cuisines of Urfa, Çorum, and Isparta. Kuru baklava (“dry baklava”) is a type made for sending long distances or taking on journeys. So that the syrup does not seep out of the packaging or drip when eaten, the lemon juice that ordinarily prevents the syrup from crystallizing is omitted, giving the baklava a dry and crunchy texture. Damascus has long been famed for its kuru baklava, which visitors to the city traditionally buy to take home.

Baklava, first recorded in Ottoman Turkey in the early fifteenth century, originated in pastries made of layered and folded filo that have been known in Central Asian Turkic cuisines since the eleventh century. Such dishes appear to have then joined forces with the Arab culinary tradition of soaking pastries in syrup, giving rise to baklava. A thirteenth-century Arabic cookbook Kitāb al-Wuslaila al-Habib describes a sweet pastry very similar to baklava with the Turkish name karnıyarık (“split belly”) and uses the Turkish term tutmaç for the thin pastry sheets. In this recipe each sheet of filo is rolled around a slender rolling pin, gathered into a concertina, and formed into circles, much like the baklava types known today as sarığıburma or bülbülyuvası.

An early-fifteenth-century poem by the mystic Kaygusuz Abdal mentions baklava filled with either almonds or lentils, fillings specified in two early-sixteenth-century Persian recipes. Other fillings mentioned in historical Turkish sources are clotted cream and puréed melon. Ottoman pastry cooks working for the palace or wealthy patrons sought to make baklava with an increasing number of ever-thinner layers. An account of the circumcision feast for the son of Murad III mentions “trays of many-layered baklava,” and in the mid-seventeenth century one writer refers to baklava consisting of a thousand layers, clearly an exaggeration but revealing how the number of layers had become a culinary status symbol. Moreover, the baklava had to be so delicate that a coin dropped from a height of about 2 feet pierced each layer and struck the bottom of the baking tray.

Baklava is a festive dish, associated above all with Ramazan (Ramadan in Arabic-speaking nations). Until 1826, every year on the 15th of Ramazan, janissary soldiers marched to the palace in the Baklava Procession to collect hundreds of trays of the sweet, which had been baked in the palace kitchens. One tray was shared by 10 janissaries, 2 of whom would carry the tray back to the barracks. A popular Ramazan poem about this event begins with the following verse:

As the sun and moon revolve

May divine aid be your company

The sultan gave baklava

To his loyal janissaries.

For centuries baklava has been a feature of meals on religious feast days, or at weddings and other celebrations; it also once was the custom to present baklava as a gift to neighbors and acquaintances on special occasions. Turkish novelist Aziz Nesin (1915—1995) recalled that when he was a child of five, his mother had become inconsolable because she could not afford the sugar and nuts needed to bake a tray of baklava as a gift for his schoolteacher. Today, baklava still retains this festive character in many countries and is often made or bought for family gatherings on days and nights of celebration and thanksgiving.

See also greece and cyprus; islam; middle east; persia; and turkey.

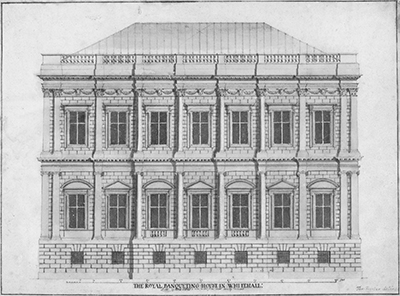

banqueting houses were small garden buildings in Tudor and Stuart England, so called because “banqueting” was the primary activity enjoyed in them. The Tudor “banquet” was not the sumptuous feast that we now associate with the word, but a delectable, intimate repast of marzipans, jellies, quince cakes, meringues, gingerbread, and other treats, washed down with ipocras, a form of mulled wine flavored with cinnamon, cloves, ginger, peppercorns, nutmeg, and rosemary, all steeped in sugar. See hippocras. Gervase Markham described the banquet in The English Housewife (first published in 1615), giving specific orders for the “making of Banquetting stuffe and conceited dishes, with other pretty and curious secrets.” The order in which the food was presented was precisely detailed, beginning with “a dish made for shew only, as Beast, Bird, Fish or Fowl,” followed by the sweets listed above, as well as marmalade, not a jam but oranges filled with sugar paste, then sliced. The elegant and decorative little delicacies were eaten off special plates or roundels, approximately the same size as dessert plates today, often decorated with witty pictures, inscriptions, and puzzles. Fine examples in embossed and painted leather survive (at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London), but the most magnificent are the set of eight silver plates, hallmarked 1586, depicting the life of the Prodigal Son (part of the Collection of the Duke of Bucchleuch). The banquet was offered to intimate friends of the host, invited into a banqueting house in the garden or sometimes on the roof. At some houses, there was a choice of going to the garden or onto the roof.

The origins of the banqueting house appear to be medieval, as in the early sixteenth century the antiquary John Leland noted that Henry VIII had moved a “praty baketynge house of tymber,” originally erected in the early fifteenth century by Henry V, from the “Pleasance” at Kenilworth into the court of the castle. Henry VIII himself built numerous little banqueting houses in his garden at Hampton Court, all carefully recorded in Wyngaerde’s drawings of ca. 1560 (at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford). Each of Henry’s banqueting houses was different in plan (some square, some polygonal) but each had an upper room, brilliantly glazed on all sides and accessible via a stair turret that rose to a platform on the “leads” or flat roof. Clearly, the banquet was meant to be consumed while appreciating the glories of the landscape. Nowhere is this better illustrated than at Lacock Abbey (Wiltshire), where ca. 1550 Sir William Sharington built a three-story octagonal tower with a banqueting room in the upper story with expansive windows and, at its center, a splendidly carved Purbeck marble table. Shell-headed niches in the base contain figures of Bacchus, Ceres, and the Roman epicure Apicius, wonderfully apposite banqueting companions. After enjoying their banquet, the more energetic banqueters could climb the winding stair up to the balustraded roof of the tower for splendid views over the gardens and medieval fishponds.

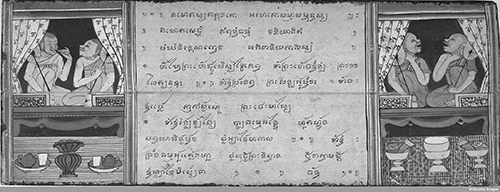

Banqueting houses were small garden buildings where hosts entertained guests at the end of a formal meal and served delicacies such as marzipan, gingerbread, meringues, and hippocras, a mulled wine. This drawing by the British artist Thomas Forster (1672–1722) depicts the royal banqueting house in Whitehall, London. yale center for british art, paul mellon collection

Later Elizabethan houses, such as Hardwick Hall (Derbyshire), had banqueting houses on both the roof and in the garden. At Hardwick, the great south tower room is approached via a long walk across the roof and entered through a door, above which looms a ferocious gorgon’s head, an apotropaic device to discourage evil spirits from destroying the joyful mood. On roof level, one can also look down on Bess of Hardwick’s two lozenge-shaped banqueting houses: one in the corner of the south garden and the other in the orchard, to the north of the house.

Because of their relatively small size, banqueting houses were inexpensive to build, so they were perfect for architectural experimentation. Just like banqueting food, they were meant to be “curious” and “artificiall,” according to Markham again, who wrote that they “lustre to the Orchard.” The octagonal form was particularly popular in the Tudor period and remained an option well into the seventeenth century. Even Elizabeth I, who rarely spent money on her palaces or gardens, erected an octagonal banqueting house at the end of the long terrace at Windsor in 1576 for which plans survive in the National Archives (London). Later banqueting houses were built on more unusual plans: rectangular; oval; lozenge-shaped (as at Hardwick); or in the shape of a cross superimposed on a square, as at Montacute (Somerset). When Sir Francis Drake’s ship “The Golden Hind” became unfit, he removed the cabin from its deck and turned it into a banqueting house in his garden in Deptford. William Cecil, Lord Burghley, had banqueting houses at all of his houses: sketches in his own hand survive for those he built in his London garden (dated 1565; preserved at Burghley House, Northamptonshire). At his grandest house, Theobalds (Hertfordshire), visitors commented on a semicircular banqueting house with statues of 12 Roman emperors and, on the roof, lead cisterns that could be used for bathing in the summer.

Such exuberance did not please everyone, and at the turn of the century, John Stow wrote grumpily in his Survey of London (1598) that banqueting houses bear “great shew and little worth.” Although the practice of building them continued through the early Stuart period, the practice gradually died out. Those few banqueting houses that survive today generally stand empty and unused, evidence of changes in fashion that not only affected gardens but also spelled the doom of the little banquet itself.

See also dessert and sweet meals.

bar cookies are made by pouring, spreading, or pressing batter into a square or rectangular pan (sometimes in several layers) and cutting the finished product into individual pieces after baking. This type of cookie is more cake-like than are drop cookies and rolled cookies, due to the addition of more eggs or shortening to the batter. See drop cookies and rolled cookies. Bar cookies are also known as pan cookies, squares, bars, and, in Britain, tray bakes.

These cookies were not invented at a single moment in time, but rather represent a natural evolution from cakes and sweet breads cooked in a single pan. They are a style of bakery item particularly suitable for families and informal events, and because they are more quickly made than individually formed cookies, and also pack and transport well in the pan, they are popular with the busy home cook. The best known, and arguably the most popular form, are brownies. See brownies.

References to “bar cookies” appear in grocers’ advertisements in the 1890s, but their exact nature is not certain. Most of these references apply to Kennedy’s Fig Bar Cookies (later called Fig Newtons), but these are formed from extruded dough with a filling. See fig newtons. Other references to fruit and date squares at this time are clearly for a confectionery product. The first known recipe for a baked item that unequivocally fits the concept of a bar cookie appears in the Indianapolis Star on 3 July 1924 for a peanut bar cookie with a peanut frosting.

Bar cookies are still popular today, and are likely to remain so, because of their ease of preparation and great range of ingredients, flavors, and textures.

See also small cakes.

barfi (also spelled burfi), from the Persian and Urdu word for snow, is a sweet with a fudge-like consistency that is especially popular in northern India. It seems to be a relatively recent invention. The classic barfi is made from finely granulated sugar and khoa/khoya, milk solids produced by slowly boiling milk until it becomes thick, stirring constantly to prevent caramelization. These two ingredients are cooked together and, when thick, spread over a greased plate. Once cooled, the mixture is cut into squares, diamonds, or circles. At this stage it resembles snow, hence its name. According to Mrs. Balbir Singh in her classic Indian Cookery, a sugar to khoa ratio of 1 to 4 is the preferred base for barfi.

Varying proportions of other ingredients may be added, including melon seeds, guava, grated carrot, or grated coconut. Flavorings include saffron, rosewater, kewra water (an extract made from padanus flowers), vanilla, orange, mango, and especially cardamom powder. Some varieties, notably those made with pistachios and almonds, do not contain khoa; instead, ground nuts (peanuts) are boiled in a sugary syrup. Barfi is a favorite sweet at Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights. When distributed to guests at weddings and other festivities, barfi is often decorated with finely beaten and edible silver leaf (vark).

A variant is Mysore pak, a popular South Indian sweet with a granular texture. It is made by roasting chickpea flour with ghee, then cooking it with sugar syrup, adding more ghee, and cutting it into squares when cool.

barley sugar is a hard, clear sugar confection with a golden color, formed in round or oval drops or long twisted sticks. It is made in the United Kingdom, Australia, and North America (“barley sugar candy”), and also in France, where it is known as sucre d’orge.

Traditionally, barley sugar is made by boiling sugar to hard crack or the start of caramel at 328° to 346°F (150° to 160°C) and adding an acid to prevent recrystallization on cooling. See stages of sugar syrup. Craft production employed lemon juice or vinegar, but mass-produced barley sugar in the United Kingdom is now often made with a mixture of sugar and glucose, which has the same effect. See glucose. Lemon essence is generally used as a flavoring in the British tradition of sugar boiling.

In Les friandises et leurs secrets (1986), Annie Perrier Roberts notes how in France, sucre d’orge is a speciality of various spa towns, as well as the city of Tours, and as Sucre d’Orge des Religieuses de Moret it has an association with convent sweets and the town of Moret sur Loing. See convent sweets.

Originally, the sweets contained a decoction of barley, but this disappeared from recipes around the start of the eighteenth century. Barley sweets were regarded in some way as medicinal; even today in Britain, sucking barley sugar is sometimes recommended as a treatment for overcoming motion sickness. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration, after discovering the complete lack of barley in modern barley sugar, has discouraged the use of this traditional name.

Baskin-Robbins, an American chain of ice cream shops, was the brainchild of brothers-in-law Burton “Burt” Baskin and Irvine “Irv” Robbins. Today, every ice cream shop in the United States seems to churn out a host of exotic flavors, from olive oil and lavender to honey jalapeño and sweet corn. But when Baskin-Robbins was launched in the early 1950s, its notion of serving 31 flavors was novel.

Burt and Irv had started out as small-time ice cream shop owners with separate businesses in Southern California. In 1945 Robbins opened Snowbird Ice Cream in Glendale, California, where he offered 21 flavors. A year later Baskin opened Burton’s Ice Cream Shop in Pasadena. By 1948 the two ice cream entrepreneurs boasted half a dozen shops in Southern California. A year later the number had jumped to more than 40. In 1953 the brothers-in-law took a leap and joined forces to create Baskin-Robbins, which became the international ice cream juggernaut we know today. They also began to franchise their operation.

For years, Americans had been fiercely loyal to the classic ice cream triumvirate of vanilla, chocolate, and strawberry. Even Howard Johnson, who marketed 28 flavors in its famous orange-roofed restaurants dotting America in the 1950s and 1960s, could not quite manage to tear customers away from the tried-and-true ice cream standards. Baskin and Robbins changed all that. Believing that Americans were ready for a more sophisticated menu of flavors, they rolled out 31. Black Walnut, Cherry Macaroon, Chocolate Mint, Coffee Candy, and Date Nut were among the original flavors.

Not only were the men bent on expanding Americans’ palate for ice cream, they wanted their shops to project an aura of fun. The advertising firm they hired recommended that the company adopt a “31” logo, to represent Baskin-Robbins’s strategy of offering a different flavor of ice cream for each day of the month. They also created a shop décor that instantly invited customers to have a good time, with its riot of smiling clowns and pink and brown polka dots. (Today, the dots are pink and blue.)

Baskin-Robbins, believing that people should be allowed to try a range of flavors to discover the one they most wanted to buy, also introduced a now-iconic small plastic spoon with which to sample ice cream flavors. Thus was born the famous little pink spoon that spawned millions of progeny in ice cream shops around the world.

Despite Howard Johnson’s conviction that Americans would never stray from their preference for plain old vanilla, ice cream devotees flocked to Baskin-Robbins stores. At their factory in Burbank, Baskin and Robbins invented hundreds of ice cream flavors each year, including classics like Blueberry Cheesecake and Jamoca Almond Fudge. Flavors rotated through the stores so that customers would be greeted with something new whenever they stopped by for ice cream. Since 1945 the company has rolled out more than 1,000 flavors. Some, however, never made it to the ice cream shops, such as Ketchup, Lox and Bagels, and Grape Britain. More successful were flavors celebrating popular culture or special events, such as the popular Lunar Cheesecake (a nod to Neil Armstrong’s moon landing), Cocoa a Go-Go (a tribute to the go-go dancing craze), and Beatle Nut, to honor the Fab Four as they were about to embark on their first American tour.

In 1967 the Baskin-Robbins ice cream empire was sold to United Fruit Company for an estimated $12 million. Six months later Baskin died of a heart attack at age 54. In the 1970s the company expanded into the global market, unveiling outlets in Japan, Saudi Arabia, Korea, and Australia. In many countries, Baskin-Robbins has introduced flavors designed to appeal to local tastes. For example, in Japan, Matcha (green tea) ice cream shares freezer space with Strawberry Shortcake. Today, Baskin-Robbins, with over 7,000 stores in nearly 50 countries, is part of Dunkin’ Brands, owner of another global snack icon, Dunkin’ Donuts. See dunkin’ donuts.

In a 1976 interview in the New York Times, Irv Robbins took credit for Americans’ newfound delight in exotic ice cream flavors. “They’re not embarrassed to ask for some of these wild flavors,” the bespectacled ice cream man said. “I think we’ve had a little bit to do with making it acceptable.”

See also ice cream.

Baumkuchen means “tree cake,” and a glance at one of these German specialties explains the name. In its uncut form, a Baumkuchen is a 3- to 5-foot-tall cylindrical column, hollow on the inside and patterned in ridged rings on the outside. The result surely suggests a tree trunk, albeit one glazed with a sheer white icing or, for more modern tastes, a chocolate frosting. To be served, it is cut horizontally in curved shavings and slices to show a series of rings much like the age rings of tree trunks. Those rings are a result of the baking process. Baumkuchen is one of a long line of spit cakes, some dating back to medieval times. These cakes are baked—or perhaps more correctly, grilled or toasted—on rotisserie spits over or in front of wood fires or, commercially today, electric grill-ovens. The spits are fitted with cone-shaped or elongated sleeves covered in layers of wet parchment. The batter for Baumkuchen is a rich, foamy, custard-like mixture that includes eggs, butter, flour, and possible flavorings of lemon, almond, or vanilla. When the spit is hot enough, portions of batter are poured over the parchment (or the spit is lowered into a trough of batter), and the thick liquid wraps around the revolving spit as it bakes. When one layer has turned pale golden brown, another is poured over and so on, accounting for the rings and often adding up to between 16 and 35 layers, depending on the width desired.

Baumkuchen is the most famous spit cake but not the only one. Lithuanians love their šakotis, Poles their sękacz, Hungarians their kürtőskalács, and Swedes their spettekaka. The French cherish the petite, cone-shaped gâteaux à la brioche still baked by artisans in the southwest part of the country. In Hampton Court, the palace of Henry VIII, one can watch Tudor-period cooking demonstrations during the Christmas season that often include the spit cake trayne roste. Oddly, Baumkuchen enjoys a loyal following in Japan, where in about 1919 a German baker, Karl Juchheim, who had been imprisoned by the Japanese, went to Kobe upon his release and opened a Baumkuchen bakery that not only survives but also has inspired many others throughout the country. Baumkuchen today is baked in the United States, especially in Chicago and in Huntington Beach, California.

See desserts, chilled.

bean paste sweets are a group of popular Asian confections filled or composed of a sweetened bean paste. Bean paste made from azuki beans is the quintessential sweet filling used in numerous Japanese, Chinese, and Korean pastries. See azuki beans. It is prepared by boiling azuki beans, pounding or chopping them, and combining and cooking the paste with sugar, and lard in some countries. For a more refined version, the paste is pressed through a sieve to remove the skins. Red azuki beans, because of their auspicious color, have meant good fortune since the Han dynasty (206 b.c.e to 220 c.e.) and are eaten on holidays, birthdays, and other festive occasions in pastries, puddings, soups, and other sweet confections.

Typical azuki desserts in Japan include anmitsu, for which an, small cubes of agar-agar jelly, and pieces of fruit are served in a syrup. Anpan is a sweet bun filled with red bean paste. (This is also a popular dim sum or sweet in China.) An is also used as a stuffing for mochi and as a topping for dango. See dango; japanese baked goods; and mochi.

In China, the most popular azuki-bean confections include tang yuan, glutinous rice balls filled with red azuki, ground sesame, or date paste that are served at banquets for festive occasions as well as on the Lantern Festival, a holiday observed 10 days after Chinese New Year. Zong-zi are conical-shaped dumplings made with glutinous rice stuffed with sweet and savory fillings and wrapped in bamboo leaves and served during the Dragon Boat Festival in the spring. Mooncakes are the traditional holiday pastry served on the Festival of the Harvest Moon. See mooncakes. Baozi or do sha bao is a steamed bun filled with sweet azuki or date paste.

Korean azuki-paste desserts are equally celebrated. The most prominent are chalboribbang, “sweet” rice pancakes consisting of two glutinous barley-flour pancakes stuffed with sweet bean paste, and patjuk, an azuki-bean porridge traditionally served during the Winter Solstice Festival.

See also china; japan; and korea.

Beeton, Isabella (1836–1865) was a writer, cook, and author of Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1861), arguably the most famous English domestic manual ever published. As an icon of Victorian culture, both during and after her lifetime, Beeton bridged the transition from tradition to modernism, typifying an era in the throes of industrialization and advancing knowledge.

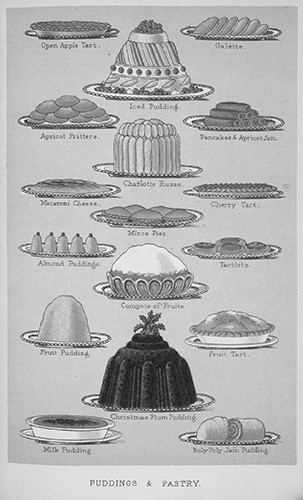

Originally commissioned as a series of articles by her publisher husband Samuel Beeton, Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management was a compilation of essays and recipes, ranging from medicinal tonics to pineapple ice cream. In addition to recipes for kitchen classics such as boiled carrots and mashed potatoes, four extensive chapters were dedicated to cakes, confectionery, and sweet dishes—a dessert panorama showcasing traditional English recipes like Bakewell Tart alongside dishes with a more colonial twist, such as “Delhi Pudding.”

Although the publication celebrated traditionally feminine domestic skill, acknowledging the real expertise that had perhaps gone unappreciated in the past, it also strongly implied that a woman’s place was in the home, a space somewhat isolated from the public jurisdictions of men. While Beeton may not be considered a feminist by today’s standards, her work unified the domestic experience, becoming a ubiquitous title in bookshelves across the country. Her legacy lies in her unique talent for digesting and communicating information, making it accessible to the world beyond the kitchen walls.

Though it may be a surprise to most, Isabella Beeton was not the matronly or middle-aged mother that we often presume her to be; she died at the age of 28, a day after giving birth to her fourth child. Her books, however, lived on beyond her years, a timeless comment on domestic prowess and an embodiment of the nineteenth-century feminine ideal. So powerful was her influence that her subsequent publishers kept the news of her death quiet in order to give gravitas to future installments of Household Management, and even published full titles under her name.

This lithograph depicting fashionable pastries and puddings appeared in the 1888 edition of Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management, England’s most famous domestic manual. The volume was popularly called Mrs Beeton’s Cookbook because more than 900 of its 1,112 pages contained recipes. british library, london © british library board. all rights reserved / bridgeman images

See also united kingdom.

See doughnuts.

Belgium, a small kingdom in Western Europe, has been internationally famous for its chocolate and waffles only since the 1970s. The country’s reputation for sweets can be explained by its long history of culinary influences and its many eras of opulence. Before Belgium became an independent nation in 1830, the region had been part of various monarchies that introduced French, Spanish, and Austrian influences, and with them Italian, Arabic, and Near-Eastern ones. With regard to foreign influences, it is telling that in the late fifteenth century the Canary Islands were known as the Flemish Isles because of the large population of Flemings who grew sugarcane there to ship to the Low Countries. As a result of their activity, the price of sugar fell by almost 60 percent within several years. See sugar trade.

Despite—or because of—foreign domination, this part of Europe flourished: agricultural output was high; international trade enriched the ports of Bruges, Ghent, and Antwerp; and manufacture brought prosperity to Brussels, Liège, and Mons. Even during harsh years when prices were high, Flemish laborers ate fruit pies, sugared compotes, and pancakes with honey at fairs, harvest feasts, and weddings. See fairs. Jacques Jordaens has depicted Belgium’s sweet tooth in various versions of his painting The King Drinks (ca. 1640), which shows a celebration of the children’s feast Drie Koningen (Three Kings Day, 6 January), when a special cake containing an almond was baked. Whoever found the almond became king for a day. Jordaens’s holiday table is laden with waffles, pastries, beer, and wine. See twelfth night cake.

By the end of the eighteenth century, however, austere times had arrived, and abundant sweets were for most of the population a thing of the past. Average annual sugar consumption at that time barely reached 5 kilos per capita. Very slowly, sugar intake rose to 15 kilos before World War I. In the 1930s the League of Nations estimated Belgium’s average sugar consumption to be 28 kilos, higher than the European average (22 kilos) but significantly lower than the annual intake in, for example, Great Britain (49 kilos). Belgian nutritionists encouraged higher sugar consumption because of sugar’s energy value. One way to achieve this was by promoting tea drinking (which was unpopular in Belgium) with plenty of sugar, “as in England,” to increase the number of calories consumed by the elderly. Moreover, housewives were instructed to convince their husbands and children to consume more sugar in any way possible. The campaign worked. In the 1970s average yearly sugar consumption rose to 35 kilos per capita; it is 45 kilos today.

The nineteenth century’s low intake can be explained by both the high price of sugar and the subsequently close link between sugar and higher social class. For a long time, pastries, viennoiseries, cakes, puddings, ice creams, chocolates, marmalades, cookies, and various friandises found in French haute cuisine were available exclusively to rich Belgians. Harsh living conditions caused working-class men to consider a sweet tooth a feminine trait, so they hardly even used sugar in their daily cups of coffee. Nonetheless, relatively simple pastries such as mattentaart (a small round cheesecake), pain à la grecque (crisp, thin bread that has no connection with Greece, but with the Flemish word for “ditch”), peperkoek (gingerbread), speculaas (a shortbread biscuit with cinnamon), or vlaai (a solid flan with brown sugar) were produced locally, becoming more widespread in the 1900s. See gingerbread and speculaas.

By that time, the situation had irrevocably begun to change as a result of technological and organizational innovations in the production, transportation, and retailing of sugar and candy; the lowering of taxes on sugar; and promotional campaigns by manufacturers, nutritionists, and public authorities. The price of sugar fell, and gradually more people ate it in very diverse forms, including the “invisible” sugar added to lemonade, canned vegetables, and bread. Moreover, the large biscuit and chocolate factories that had appeared in the 1880s manufactured individually wrapped products that could be advertised easily (among which was Côte d’Or, which produced individually sized chocolate bars).

Several developments illustrate the diffusion of sugar within Belgian society between the late 1880s and early 1930s. Especially telling is the story of the gâteau du dimanche, the “Sunday cake” that the governor of the province of Hainault in southern Belgium advocated in 1886: he favored establishing home economics schools for young girls, where they could learn how to prepare a sweet pie that might be used as a reward for good children (and to keep husbands away from the tavern). Significant, too, was the fact that school manuals for household education gradually included a larger number of recipes for sweets: between 1900 and 1930, desserts barely accounted for 10 percent of the total recipes in these books, but their numbers rose to 30 percent in the late 1930s to 1950s. Furthermore, the amount of sugar called for in pastries, biscuits, and other desserts in these manuals increased between 1900 and 1950. Waffles are a good example: the ratio of sugar to flour was 1 to 3 around 1900, but it rose to 1 to 1 in the 1930s to 1950s.

It was during the latter part of this sweet zenith that warnings against too much sugar consumption appeared: sugar, especially for young children, was considered bad for the health. See sugar and health. In 1956, for example, a dietician cited sugar’s energy as very harmful; he warned particularly against processed white sugar, preferring by far the unrefined cane sugar that he saw as natural. Such a view appeared increasingly in cookbooks, women’s magazines, and television programs, and it influenced the perception and usage of sugar. Since the 1970s the number of desserts in cookbooks has diminished somewhat, and the amount of sugar (for example, for making waffles) has declined significantly. Although the use of visible sugar (as added to coffee, for instance) has fallen, the use of “invisible” sugar has only grown.

The trends toward healthier and so-called authentic desserts have necessitated the upgrading of many ordinary sweets like speculaas, which nowadays appears as a flavor in honey and ice cream and as a spread for bread, as well as in numerous forms on the menus of fancy restaurants. Many of Belgium’s old, ordinary sweets have now been transformed into culinary heritage, thereby giving them a second life. This upgrading of ordinary sweets has been accompanied by the gradual trickling down of luxury sweets to the masses, leading to a great variety of chocolates, ice creams, and pastries that can be enjoyed by the Belgian population at large. Baba au rhum, bavarois, and savarin have descended from haute cuisine, while éclairs and waffles from popular cooking have gained new status.

See also chocolate, luxury and godiva.

Ben & Jerry’s is now an internationally recognized ice cream business, but that was not part of Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield’s career plan when they were growing up on Long Island, New York. In fact, they had no career plan. After college, each considered different options before deciding to go into business together. Starting a bagel company was their first choice. They planned to deliver fresh bagels, lox, cream cheese, and the New York Times to customers every Sunday morning. However, after they learned how steep the start-up costs would be, they opted for ice cream.

They took a $5 correspondence course in ice cream making from Penn State University and began visiting homemade ice cream shops, tasting and taking notes. In 1978, with $12,000 they had scraped together, they renovated a gas station in Burlington, Vermont, and opened Ben & Jerry’s Homemade Ice Cream and Crepes. They chose Burlington, despite its cold winters, because it was a college town and had no homemade ice cream shop. The crepes were intended as a hedge against the slow winter ice cream business. The partners stopped making crepes when their ice cream became popular enough to weather the winter.

Cohen and Greenfield created an ice cream that was richer and creamier than most because it contained more butterfat and was mixed with less air. Since Cohen did not have a strong sense of taste, they flavored the ice cream more intensely as well. Best of all, taking their cue from the mix-ins Steve Herrell had made famous in his eponymous Somerville, Massachusetts, ice cream parlor, they mixed extra-large chunks of chocolate, nuts, cookies, or candy into the ice cream. Customers flocked to the small shop.

Soon, the partners began selling ice cream to local restaurants and grocery stores. They continued to expand the business, adding shops, distributing to more stores, and franchising scoop shops. In 1984, needing capital, they sold shares in the company to Vermont residents, thereby strengthening the company’s local image as well as raising cash. The stock was priced at $10.50 a share, with a minimum purchase of 12 shares. The offering sold out quickly.

Cohen and Greenfield believed in supporting the Vermont community. In addition to selling stock only to Vermonters, they used local, non-bovine-growth-hormone milk in their ice cream. They hired a local artist to design the company graphics. They also thought work should be a pleasure. “If It Isn’t Fun, Why Do It?” was a company credo. They gave their flavors funky names like Whirled Peace, Chubby Hubby, and Chunky Monkey. They held a free ice cream cone day every year and gave pregnant women two free cones, all of which created a strong brand identity.

Values before Profits

From the beginning, the men applied their countercultural values to the enterprise. They believed that no one in the company should earn more than five times the entry-level staff’s salary. They put a profit-sharing plan in place almost before there were profits. One of the more popular company benefits was free ice cream. Each employee could have up to three pints a day.

The business was thriving and competitors noticed. When the Pillsbury corporation tried to freeze Ben & Jerry’s out of some supermarkets to protect its Häagen-Dazs brand in 1984, the company fought back with a successful “What’s the Doughboy Afraid Of?” campaign. Cohen and Greenfield were seen as young entrepreneurs standing up to a corporate giant. The case, which was settled out of court, was a public relations triumph for Ben & Jerry’s. See häagen-dazs.

In 1985 the men established the Ben & Jerry’s Foundation with gifts from Cohen and Greenfield and an annual company contribution of 7.5 percent of pretax profits. Ben & Jerry’s was recognized as a progressive company with a strong social conscience. In 1993 the partners received the James Beard Humanitarians of the Year Award.

The company’s sales had reached $48 million by 1988, the year President Ronald Reagan presented Cohen and Greenfield with the National Small Business Persons of the Year Award in a White House ceremony. Ironically, at the time they were developing Peace Pops, a chocolate-covered ice cream bar that promoted reducing the military budget. They hardly expected an invitation to the White House.

The company continued to grow, expanding into Canada in 1988, to Russia in 1992, the United Kingdom in 1994, and Japan in 1998. To raise capital for continued growth, Cohen and Greenfield took the company public. In April 2000 the board accepted a $325 million offer, and Ben & Jerry’s became a wholly owned subsidiary of Unilever.

Although no longer involved in the operation of the company, Cohen and Greenfield are active in its foundation as well as other philanthropic enterprises. Ben & Jerry’s ice cream remains a popular global brand and an inspiration to entrepreneurs.

See also ice cream.

benne seed wafers, crisp and delicate sweet wafers dotted with benne (sesame) seeds, have been a favorite cookie attributed to the Lowcountry of South Carolina and Georgia since the 1940s, both in general American cookbooks and local Charleston ones. They are typically served at weddings, funerals, and similar catered affairs, and it has been said that if benne seed wafers were not served at a Charleston wedding, the couple would not be legally married. Approximately the size of a U.S. quarter, but with the thickness and crispness of a Communion wafer, benne seed wafers are sold both in bulk and retail, usually in small packages or cookie tins in gift stores.

The typical benne seed wafer recipe calls for butter beaten until light with brown sugar; egg whites or whole eggs, flour, and benne seeds are added to make a batter thin enough to drop or pipe in rounds before baking. The wafers’ small size and quick baking time make them laborious to bake at home without specialized equipment.

Benne seeds, Sesamum indicum, were originally brought to the American colonies from Africa as a source of oil and to feed West African slaves. They grow in rows in an okra-like pod with a fuzzy green exterior that is attached to the slender stalk of a flowering plant. The word for “sesame” in the Wolof language of Senegal is benne, which came to be used in the American South; Thomas Jefferson refers to the seed with a variety of spellings, including Bene, benne, and beni.

It is likely that the original cookie was made from a drop batter in which sesame seeds were substituted for nuts. See drop cookies. Several bakeries, primarily Old Colony Bakery in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, are known for their benne seed wafers, but no compelling evidence exists for attributing the recipe to a specific bakery or creator.

See also south (u.s.).

Betty Crocker began as a simple feminine signature on the bottom of a letter from a Minneapolis flour company in 1921 and grew into a name so recognizable that, in 1945, Fortune magazine called her the second best-known woman in America—superseded only by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. The ranking was especially impressive, considering that Betty never actually existed.

Betty Crocker was created out of the belief that homemakers did not want to correspond with a man when they sent letters with baking questions to the Washburn Crosby Company (the forerunner to General Mills, which was incorporated in 1928). Samuel Gale, working in the company’s in-house advertising department, believed that women wanted replies from another woman on domestic matters. The surname “Crocker” was chosen in honor of William G. Crocker, a recently retired director of the company, and “Betty” for its all-American wholesomeness.

In the first few years of Betty’s existence, a dialogue of sorts blossomed between the flour company and its customers through letters and text-heavy magazine ads. Women had questions, and Betty had answers. The need for a baking expert was understandable, since new technology was making mother’s traditional kitchen advice increasingly obsolete. More and more homes had running water and electricity. Refrigerators were replacing iceboxes, while gas and electric stoves replaced coal-burning stoves. Food was changing, too—new convenience products began to line grocery shelves, and flour was increasingly processed. To complicate matters, units of measurement were not standardized. A cup might mean either 8 fluid ounces or the teacup from the cupboard. Baking pans came in all shapes and sizes, making it difficult to plan for baking success.

To help spread the gospel of good baking advice, the Washburn Crosby Company gave Betty Crocker her own radio show, with several different members of the company’s home service staff voicing the part of Betty. The powerful combination of love and baking quickly emerged as a popular theme in Betty’s radio broadcasts, recipe booklets, and advertisements. Cake, more than any other baked good, came to embody all that was Betty Crocker. Birthdays, graduations, retirement parties, and other holidays and family gatherings, she assured listeners, would not be the same without cake. Her Old-Fashioned Jelly Roll Cake, Pineapple Upside Down Cake, and Favorite Fudge Cake signified something extra, something special—a treat equal parts presentation and taste. It is no surprise that a flour company should promote recipes that used as much flour as possible, and Betty’s followers proved all too eager to “bake someone happy.”

The wholesome image of Betty Crocker, an icon of modern American convenience baking, has changed over the years to make her persona more up to date. Here she appears in advertising from 1955, 1965, and 1996.

An early recipe pamphlet series titled Foods Men Hurry Home For! included recipes for Honey Chocolate Cake with Marshmallow Filling and Almond Roca Frosting, as well as recipes for Chocolate Coconut Ribbon Cake and Kaffee Klatsch Cake (Orange Coffee Cake). Betty’s team was so serious about cakes that they introduced the finely milled Gold Medal Special Cake Flour (later renamed Softasilk). Betty devoted an entire 1935 radio broadcast “Cake Clinics” to curing “sick” cakes:

This morning I am going to talk about the food that strikes the highest note in the entire meal—the cake you serve for dessert. I think among all the foods served at your table, this is one where your reputation as a hostess and as a good provider for your family is most at stake.

For better or worse, Betty’s take on cake as one of the tenets of feminine achievement resonated with homemakers as they scrambled for Betty’s latest Pink Azalea Cake; Lord, Lady, and Baby Baltimore Cakes; Cherry Angel Food Cake; and Creole Devil’s Food Cake recipes. One woman wrote to Betty, “I don’t make your fudge cake, because I like white cake, but my neighbor does. Is there any danger of her capturing my husband?” Another wrote, “I derive so much from your lessons. Before I started listening to your talks on WCCO, I made such wretched cakes that my husband used to throw them down to the furnace to burn them. But now I am really proud of the ones I make.”

Cake continued to be big business for General Mills when it paid a large, undisclosed amount to a notorious Hollywood cake baker, the aptly named Harry Baker, for his Chiffon Cake recipe. See chiffon cake. In 1948 Betty Crocker announced her latest cake, “The Cake Discovery of the Century,” combining the richness of butter cake with the lightness of sponge cake. The secret ingredient of vegetable oil helped catapult Betty’s Chiffon Cake into sweets stardom, to become the most popular cake of the mid-century.

At around the same time, Betty Crocker’s cake mixes advertising “You Add the Eggs Yourself” eclipsed all other cake-mix brands, including Pillsbury, Swans Down, and Duff. Betty’s cake mixes still dominate grocery-store baking aisles, as if echoing her reassuring message, “I guarantee a perfect cake every time you bake … cake … after … cake … after … cake.”

See also angel food cake; cake; cake mix; hines, duncan; and upside-down cake.

biofuel, unlike the fossil fuels extracted from decomposed material, is made from living plants. Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) is the source of two major fuels: solid-based (bagasse—the fiber left over after crushing the cane—and the cane’s tops and leaves) and liquid-based (ethanol, obtained from the fermentation of sugars). Approximately 26 million hectares of sugarcane are planted worldwide (a small area compared to all major crops), of which about 5 million are currently dedicated to ethanol fuel, primarily in Brazil. Sugarcane is produced in more than 100 countries, though a handful, including Brazil, India, China, Pakistan, and Thailand, represent three-quarters of the total production.

Solid Fuel

Sugarcane is one of the most efficient energy crops. Bagasse has historically been used around the world to power sugar and ethanol mills. A well-run mill (for example, with efficient boilers) can be self-sufficient in heat and power, and also generate a large surplus that may be sold to the grid.

The potential for co-generation from sugarcane biomass has long been recognized, and many studies have investigated this vast and highly underutilized fuel. Conservative estimates from 2009 put worldwide potential at 425 million tons, equivalent to 662.4 million barrels of crude oil, located primarily in Asia (China, India, Pakistan, and Thailand) and South America (Brazil and Colombia) but also in Australia, Mexico, and Guatemala. In 2012 Brazil, for example, generated 1400 million watts from bagasse, though the potential would be 10 to 15 times greater if tops and leaves were included. Currently, a major limiting factor is the low price paid to sugarcane producers for their surplus electricity due to competition from hydropower.

Liquid Fuel: Ethanol

Ethanol can be produced from many feedstocks, but sugarcane remains king. Brazil provides the world’s leading example of ethanol from sugarcane. In 2012 about 85 billion liters were produced worldwide (approximately 536 M bbl, or million barrels oil equivalent), of which about 45 percent were from sugarcane. Fermentable sugars represent 6 to 16 percent of the sugarcane weight, making it the best feedstock for ethanol. Consequently, many sugarcane-producing countries in addition to Brazil are considering the ethanol option, primarily as a blend with gasoline in different proportions. These include China, Colombia, Central America, India (where cane is also used as feedstock in the chemical industry), Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania, and Thailand.

The use of ethanol as transport fuel goes back to the origin of the automobile industry. In 1826 Samuel Morey ran the prototype engine on ethanol; Nikaulos Otto in 1860 burned ethanol in his engines; and Henry Ford’s 1908 Model T, called the Quadricycle, also used ethanol. The use of ethanol fuel was so widespread that in 1902 an exhibition was held in Paris dedicated to its uses for vehicles, farm machinery, cookers, and heaters.

Sugarcane fuel ethanol has been used in Brazil since the early twentieth century (the first tests took place in 1907), but dramatic expansion began with the creation of Brazil’s National Alcohol Program in 1975. In its 2013–2014 harvest, Brazil produced about 25 billion liters of ethanol. There are currently 17 million cars with flex fuel engines (engines modified to use hydrated ethanol and gasoline in different blends), a number that could reach 49 million by 2020. In 2013 demand was estimated at 22 billion liters, of which 10 billion were anhydrous (almost pure ethanol used in a fixed blend of 20 to 25 percent with gasoline) and 12 billion hydrous. It is predicted that in 2020 demand in Brazil will reach 34.6 billion liters (16.6 billion anhydrous and 17.8 billion hydrous ethanol). This represents 60 percent of the estimated 840 million tons of raw cane production in 2020. The average productivity of ethanol is currently 6,000 to 7,000 liters per hectare (lha), but various studies indicate that with efficient management and money spent on research and development, the amount could increase to 15,000 lha.

Combining Solid and Liquid Fuels

Sugarcane stalks contain approximately 14 to 16 percent sucrose and 12 to 14 percent bagasse with other residues (for example, tops and leaves), which are increasingly used as fuel. The sugar contents represent 2.54 gigajoules per ton and 4.65 gigajoules per ton for residues. Based on an average yield of 82.4 tons per hectare in southeast Brazil, this represents 383 gigajoules per hectare. Considering a co-generation efficiency of 69 percent, about 287 gigajoules per hectare are available per ton of sugarcane. With the progressive introduction of more efficient boilers (currently 20 to 100 kilowatt hours and up to 200 kilowatt hours), and of greater amounts of sugarcane processed, huge surpluses of electricity can be generated. A modern sugarcane plantation could generate up to 15 times more energy than it consumes. In addition, current productivity is considered low compared to its agronomic potential of up to 340 tons per hectare.

Since many countries run a very inefficient sugar industry, sugarcane fuel has great potential for improvement with modest investment and hence will continue to play a key role in the future, despite the potential advances of second-generation biofuels.

A drawback of ethanol fuel is that it requires land. As the world’s population exceeds 7 billion, competition for food crops continues to increase, which has generated heated debate. However, in the case of sugarcane, the potential impact would be minimal, because it is one of the best feedstocks for ethanol production, both from an agronomic and an economic standpoint, and the total area is very small compared to what is needed for major crops such as wheat, corn, or soybean.

See also sugar refining; sugarcane; and sugarcane agriculture.

bird’s milk is the stuff of fantasy, and the name of this beloved Eastern European sweet reflects its mythical qualities and physical scarcity. The candies are indeed ethereal: small, chocolate-enrobed bars with a soft, marshmallow-like interior, colored white for vanilla or egg-yolk yellow for lemon. Bird’s milk candies were first produced in Poland by the famous E. Wedel company in the mid-1930s; in 2010 the company received a trademark for them from the European Union. From Poland the candy spread in popularity throughout Eastern Europe, especially Russia, where during the Soviet era of food deficits, obtaining a box of bird’s milk candies was considered a coup, nearly as unlikely as milking a bird.

Bird’s milk torte, a sponge cake with a soft, mousse-like filling and a chocolate glaze, is a purely Soviet invention from 1978, dreamed up by Vladimir Guralnik, the pastry chef at Moscow’s once-chic Praga restaurant. The cake soon became a cult item, almost as unattainable as its name suggests. Within a few years a factory was built to accommodate Muscovites’ yearning for this dessert, yet even the production of 2,000 tortes a day could not satisfy demand, and the cake remained a deficit item.

Still, whenever it could be obtained, bird’s milk was enjoyed by all segments of Soviet society. “As Guralnik later recalled in an interview for the Moscow Times, “I remember making a 15-kilogram sponge cake for Brezhnev’s 70th birthday. I don’t know if he really liked sponge cake, but that’s all he could eat with his constantly slipping dentures.” In the United States, bird’s milk cake is still popular among Russian émigrés, who use gelatin and Cool Whip to achieve the desired consistency.

birth is a life event associated with sweet foods that appear in various rituals, among which baptism, christening, or other formal presentation of a new child to a community are public events, while the actual birth, attended by women only (at least historically), is private. The foods served vary according to religion, culture, and personal beliefs, but sweetness fulfills various symbolic and practical roles, including bestowing good fortune on the child and wishing the mother well to recover her strength. Sweets form part of gift exchanges within a community and can symbolize joy and fertility, prosperity, and also provide visitors with refreshment.

In contemporary Britain, North America, and former English colonies in the southern hemisphere, a formal christening party provides the principal example of sweetness in a christening cake covered in icing and decorated with a pastillage plaque of an infant, or a model of a crib or baby, or possibly a more overtly religious symbol, such as a bible or religious text. Fruitcakes have been used to celebrate births in British culture since at least the seventeenth century, when a “groaning cake” (along with a cheese known as a groaning cheese) was provided for female supporters waiting to be allowed into the birth chamber. See fruitcake. These women were known as “God’s sibs” (siblings in God, hence “gossip”), and were also provided with drinks, as mentioned by Shakespeare in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, where Puck talks of a gossip’s bowl containing ale and a roasted crab[apple]. Rum butter (a solid mixture of butter, sugar, and rum) was provided in the English Lake District for visitors, who left coins for the baby in the bowl it was served in.

In Continental Europe, comfits or confetti are some of the most important sweet items associated with births. See comfit and confetti. Today, countries around the northern Mediterranean use these as favors, now mostly in the form of sugared almonds. Packed in bags or boxes with colors and trimmings considered appropriate, a few are presented to each guest. Favors, essentially tokens in exchange for gifts given to mother and child, are also found in North American baby showers and christening showers. In Dutch tradition, the arrival of a child is celebrated with musjies (“little mice”), tiny pink and white anise comfits, served on top of buttered rusks. Further afield, noql (sugared almonds with an irregular, bobbly surface) are served with tea and sweet biscuits at Afghan naming celebrations.

The association of comfits with birth ritual goes back many centuries. Renaissance Italian practice included various sweetmeats provided in the birth chamber for visitors, and images on special birth trays often include depictions of attendants carrying round sweetmeat boxes; records occasionally detail items including almond or pine nut sweetmeats, cakes (pane biancho, or white cake, probably like a sponge cake), and confetti as a general term. Some items were purchased from apothecaries; others were homemade.

In the sixteenth-century poem Batchelar’s Banquet, a satirical translation of the French Quinze Joies de Mariage, the author bemoans the “cost and trouble” of laying in sweets, including various comfits, only to see female guests carry away as much as they pleased. This poem also mentions sugar for the midwife. Both sugared almonds as celebratory foods and the custom of paying the midwife partly with sweet foods appears to have been more widespread. In Sherbet and Spice (2013), food historian Mary Işın reveals that during the late Ottoman period in Turkey, at six days after the birth of a child the potty under the cradle was filled with sugar almonds, which were given to the midwife.