M&M’s, with their shiny, colored candy coating protecting the chocolate inside, are the perfect embodiment of childhood. Each pellet-sized piece is like a special present just waiting to be opened and enjoyed. But the candy was never intended as a child’s treat. Ironically, it was born out of war, made specifically for the soldiers of World War II who were stationed in tropical climates where chocolate bars would melt. The man who developed the M&M brand, Forrest E. Mars Sr., first saw confections like these on the battlefields of the Spanish Civil War in the mid-1930s. According to legend, Mars was traveling through Spain with a member of the Rowntree family, famous British confectioners whose business rivaled Mars’s own. Both men were intrigued by the lentil-shaped chocolates the soldiers kept tucked away for a quick pick-me-up. Upon discovering the candy, they supposedly entered into a gentleman’s agreement whereby Rowntree would take the idea back to the United Kingdom, introducing it as a product called Smarties, and Mars would bring the candy to the United States—where it became M&M’s.

The truth of that tale is unknown. Forrest Mars had been kicked out of the family’s American business, which had been producing Milky Way, Snickers, and Three Musketeers candy bars since the early 1920s; and he did depart from Britain before World War II, leaving his candy business, the third largest in the United Kingdom and best known for the Mars bar, in the hands of his top managers. See mars. Because of his time abroad, when Forrest Mars returned to the United States in 1939, he knew better than most Americans that world tensions were high and that the country was likely headed toward war. If he planned to launch a new business, it was critical to secure a steady supply of chocolate, and that meant a visit to Hershey, Pennsylvania, home to the largest American chocolate manufacturer, the Hershey Chocolate Company. See hershey’s. Mars’s father, Frank Mars, was Hershey’s biggest customer, using the firm’s product to cover his company’s popular candy bars. Several times a week, trainloads of chocolate left Hershey, Pennsylvania, bound for the Mars plant on Chicago’s West Side. But on his return to the United States, Forrest Mars had to start from scratch. In a brilliant business move, he invited the eldest son of Hershey president William R. Murrie to partner in his new venture, asserting he would treat Bruce Murrie like family and even putting his name on the product, calling it M&M’s for “Mars and Murrie.”

Bruce Murrie was working on Wall Street at the time. At the urging of his father, he quit his job and joined in a limited partnership with Forrest Mars in the spring of 1940. Murrie put up 20 percent of the capital, and Mars contributed the rest. Murrie was named the company’s executive vice president. He and Forrest Mars set up shop in Newark, New Jersey, with equipment imported from Italy that could candy-coat the chocolate. Manufacturing began almost immediately. With a steady supply of Hershey chocolate and 10 panning drums to apply the thin candy shell, the original M&M’s were not stamped with a letter but did come in a variety of colors: brown, yellow, green, red, and occasionally violet. They were packaged in a cardboard tube that first hit store shelves in 1941. Sales were brisk from the beginning, and fearing encroachment from a competitor—like Rowntree’s Smarties—Forrest Mars patented the M&M’s manufacturing process that spring.

His partnership with Murrie paid off handsomely. In 1942, when the government ordered severe rationing, M&M did not suffer; Murrie’s father made certain the firm got all the supplies it needed. The War Department was initially M&M’s biggest customer, and millions of M&M’s went to bomber pilots stationed in North Africa and the Pacific Theater. See military. The Army also bought the candies for C-rations it distributed to soldiers in the Philippines, Guam, and other tropical climates. After the war the popularity of the brand followed the soldiers back home, although it took a few years for sales to regain their wartime peak. Forrest Mars blamed the dip on Bruce Murrie’s poor sales efforts, and the two had a falling out in 1949. Eventually, Mars bought out Murrie’s minority stake for $1 million.

In 1950 Forrest Mars began printing the letter m on the candy using black ink, yet another move designed to discourage copycats. Four years later, the peanut version of the candy was introduced, and the ink changed to the now familiar white. Oddly, the original peanut M&M’s were all tan-colored; they were changed to match the hues of plain M&M’s in 1960. With the peanut variety, Mars introduced its famous advertising slogan, “Melts in Your Mouth, Not in Your Hand,” which lasted for decades. In recent years the company has become more creative with the brand, toying with its colors and candy fillings. Today, M&M’s varieties include peanut butter, almond, raspberry, mint, and pretzel, in addition to the original plain and peanut. The company markets special color collections at holiday times and even sells special colors at its M&M World stores in iconic locations like Times Square and the Las Vegas strip. Consumers can also order specially printed M&M’s online.

The candy has developed a cult-like following. A check of the Internet reveals all manner of myth and legend surrounding the taste of different flavors and the special powers attributed to the green M&M in particular. Musicians seem to have a penchant for M&M’s, with many famous rock-and-roll bands requesting them backstage at rock concerts. Even the White House has specially packaged M&M’s in red, white, and blue with the U.S. presidential seal. A multibillion-dollar brand, M&M’s are sold around the world, and are just as popular in places like Japan and Israel as they are in the United States.

See also candy; children’s candy; and panning.

macarons (spelled with a single o) are colorful, filled cookies made from ground almonds, sugar, and egg whites that have become popular worldwide since the early 2000s. Any discussion of macarons must begin with the essential distinction between this French confection and the American macaroon, which refers most often to cookies made with sweetened coconut flakes. Macarons have a very simple ingredient list: almond flour, confectioner’s sugar, sugar, and egg whites. Flavoring and coloring agents can be added to the shells, as long as they don’t prevent the cookies from rising and obtaining their distinctive “foot,” a narrow, delicate edge that indicates a macaron’s overall quality. Macaron shells are thin and slightly crunchy, with a soft and moist interior. Achieving that perfect balance is where making macarons gets complicated, because the amount of air incorporated, the length of beating, and a temperamental oven can all affect the final result, which is why macarons are mainly made by professional pastry chefs, even though single-subject cookbooks on the topic for the home kitchen have recently proliferated.

Filled macarons were invented in the early twentieth century at the famed Parisian tea salon and pastry shop Ladurée. See salon de thé. Pierre Desfontaines, the second cousin of Louis Ernest Ladurée, had the idea of piping ganache on an almond-based shell and topping it with another shell. Although sweet macarons are standard, savory fillings, such as tomato jam or foie gras, are now also encountered, especially at restaurants where tasting menus offer a savory macaron as an amuse-bouche.

Macarons are believed to have appeared in Venetian monasteries in the eighth century, after the Arabs had brought almonds to Italy. Some sources state that in 791 a French abbey in Cormery began making ring-shaped almond cookies said to evoke a monk’s belly button, though this version more likely emerged only in the nineteenth century. In any case, by the Middle Ages, almond-based foodstuffs were already popular throughout Europe. Legend has it that the macaron arrived in France with Catherine de Medici in 1533, when she married King Henry II, though like many similar food genealogies, this story is likely inaccurate. See médici, catherine de. In any case, a cookie made from almonds and sugar became popular in France, where various cities, such as Paris, Reims, Montmorillon, Saint-Jean-de-Luz, and Amiens developed their own distinct version. Nuns were often the driving force behind macarons, which they made for both nutritional and commercial purposes (baked goods, honey, and other food products were a source of revenue for most religious orders). See convent sweets. Such was the case in Nancy, another French city famous for its macarons. In the late eighteenth century the nuns of Les Dames du Saint Sacrement’s convent, who were forbidden to eat meat, began making macarons because they were nutritious. After the closing of the convent at the time of the French Revolution, two sisters began selling the macarons in order to make a living. They became legendary as “les Soeurs Macarons,” to the point that a street now bears that name in Nancy. Nancy-style macarons are flatter than Parisian ones and don’t have a smooth surface.

By the middle of the seventeenth century, recipes for macarons had begun appearing in French cookbooks. François Pierre de la Varenne’s Le Pâtissier François, published in 1653, mentions macarons several times as elements of other recipes, seemingly to give those dishes body. The 1692 Nouvelle instruction pour les confitures, les liqueurs, et les fruits states that macarons are a combination of sweet almonds, sugar, and egg white, and offers instructions that include flavoring the batter with orange blossom water and icing them once baked, if desired. See flower waters and icing. From that point on, similar recipes for macarons appear regularly in cookbooks.

Nineteenth-century French confectionery cookbooks offer recipes for almond cookies that are made into a paste with egg whites and sugar (lemon zest is sometimes added), then combined with whipped egg whites, shaped into small mounds, and baked. Alexandre-Balthazar-Laurent Grimod de la Reynière’s 1839 Néo-physiologie du gout par ordre alphabétique, ou Dictionnaire générale de la cuisine française, ancient et moderne lists no fewer than eight macaron recipes, including two for macarons soufflés, which could be closer to the light, meringue-based macarons we most often think of today. See meringue.

If nineteenth-century books about Paris are to be believed, the city was teeming with macaron street vendors. Those vendors did not look like the elegant Ladurée, to be sure, but they testify to the lasting power of the combination of almonds, sugar, and egg whites. Today, cities large and small around the world have shops devoted to macarons, while pastry shops and supermarkets offer their own versions.

See also france.

madeleine is a small sponge cake in the shape of a shell that occupies a hallowed place in French patisserie. Madeleines have long been associated with the town of Commercy in Lorraine, whose bakers claim that the cake originated during the eighteenth century in the kitchens of the nearby chateau of Stanisław Leszczyński, father-in-law of Louis XV of France. The name of the cake is attributed to an elderly cook named Madeleine Paulmier (according to Bescherelle).

Nineteenth-century cookery books (those by Audot and Brisse, for instance) give recipes for madeleines as a modified pound cake or quatre-quarts mixture, a type of sponge cake with a sufficiently firm crumb to prevent its breaking apart when dipped into a cup of hot tea or a tisane. See pound cake and sponge cake. A madeleine batter is made by beating together softened butter, fine white sugar, egg yolks, and wheat flour. The mixture is aerated with whisked egg whites and flavored with zest of lemon and orange flower water or brandy. Spoonfuls of the mixture are baked in special embossed madeleine tins that resemble small scallop shells. When baked and cooled, madeleine cakes are either left plain or dusted with confectioner’s sugar. See sugar. Alternatively, a sugar glaze is brushed over the freshly baked cakes, which are replaced in the oven for a few minutes to dry.

Madeleine cakes are more attractive served upside down to display their distinctive shape, described by the writer Marcel Proust as “a little shell of a cake, so generously sensual beneath the piety of its stern pleating.” Tasting a madeleine, dipped in linden tea, revived hidden memories that profoundly influenced Proust when writing his celebrated novel A la recherche du temps perdu.

The madeleine is considered so emblematic that it represented France in the European Union’s Europe Day in 2006. The popularity of the cake remains undiminished, so in addition to the classic plain kind, many other versions are produced. Even Carême (1784–1833) listed half a dozen variations that include chopped pistachios, or currants, or candied peel. See carême, marie-antoine. Carême’s madeleines en surprise are covered with a meringue mixture and replaced in the hot oven until lightly toasted. Today’s madeleines may be filled with jam or fruit purée, or iced or frosted with chocolate. Yet all retain the characteristic indentations of the legendary little cake.

See also meringue and small cakes.

See north africa.

Maillard, Henri (1816–1900), was America’s preeminent nineteenth-century confectioner. Celebrated in his adopted country for his Frenchness, he was sometimes considered too American in his native land. “Only a Yankee could have conceived the idea of creating an edible Venus de Milo,” sniffed the French critic Eric Monod, echoing the sentiments of others in response to the 400-pound chocolate sculpture Maillard showed at the 1889 Paris Universal Exhibition.

This split identity characterized the career of Maillard, who immigrated to New York in 1848. At the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial, he included sugar models of such uniquely American figures as the Pilgrims and founding fathers, General Custer and Sitting Bull in one enormous exhibit, while flying the flags of both the United States and France above another. This latter exhibit demonstrated how cacao beans were turned into chocolate using French machinery available in the Machinery Hall’s France section. Yet Maillard used “Henry,” not “Henri,” on the exhibit’s signage and achieved great American success with the grand presidential party he catered at the White House on 5 February 1862. Hosted by First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln to unveil her renovation of the presidential mansion, the gala boasted as its centerpiece a Maillard-made confectionery steamship flying the Stars and Stripes, along with sugar models of Fort Sumter and the Goddess of Liberty.

Maillard’s first chocolate factory-cum-shop and catering facility were in downtown Manhattan. By the 1870s the factory had moved up to West 25th Street, while the shop and a restaurant occupied part of the swank Fifth Avenue Hotel at 23rd Street. Photographs of the shop, circa 1900, show an Edwardian fantasy of mirrored walls, crystal chandeliers, mahogany display cases, and a cherub-painted ceiling. Surrounding the staff are tables of beautiful baskets and boxes of chocolates, as well as candy novelties like a life-size bust of a woman that could be mistaken for a customer. Chairs and tables along one wall reinforced Maillard’s claim that his was “An Ideal Luncheon Restaurant for Ladies.”

After Maillard’s death, his son Henry Maillard Jr. moved the business slightly uptown, setting up first at Fifth Avenue and 35th Street in 1908, then at Madison Avenue and 47th Street in 1922. Hoping to expand beyond its reputation as a magnet for women, Maillard’s added a men’s-only restaurant with a separate entrance in the later location, which was visited by none other than James Beard. Maillard’s also opened a branch in Chicago, on upscale Michigan Avenue.

Although Maillard’s catering and restaurants attracted high society, its cocoa was marketed to a broader public. Free instruction in the art of preparing “Maillard’s Chocolate for Breakfast, Lunch & Travelers” was given at Maillard’s New York Chocolate School in the 1890s. The company’s chocolate candies were popular well into the 1960s, long after the Depression had driven Maillard’s other divisions into bankruptcy.

The Chicago restaurant was absorbed by the Fred Harvey chain, but Maillard’s new owner ruined the New York locations, the last of which closed in 1942—a sad fate for the memory of the immigrant who had won World’s Fair renown for his 200-pound chocolate vases and 3,000 kinds of filled chocolates.

See also chocolates, filled; chocolate, luxury; cocoa; and sugar sculpture.

malt syrup is an unrefined sweetener derived from germinated (sprouted) cereal grains, typically barley, in combination with other cooked grains. If malted barley alone is used, the resulting syrup may be called “barley malt extract,” or just “malt extract,” and the malt aroma will be more intense. Malt syrup is used in bread and other baked goods, jams, breakfast cereals, confectionery, and in brewing beer.

The first step in malting grains is to put them in a dark room and soak them in water. The germinating grains produce enzymes that convert starches into sugar to fuel growth. (Barley produces unusually active and abundant malt enzymes.) The maltster then halts enzymatic activity by quickly drying the sprouting seeds, which kills the seed embryo and preserves its nutrients. The malted grains are crushed, steeped in hot water, and mixed with cooked grains (unless it is a malt extract, in which case cooked grains are not added). Malt enzymes digest the starch present in the cooked grains, forming a slurry that is concentrated and evaporated by boiling off the water, or, in modern food-grade malt plants, by using a vacuum evaporator. The sticky dark brown syrup that is left is about half as sweet as table sugar, with a distinct flavor some have described as biscuity, honeyed, or, depending on the kilning technique, roasted, with chocolate and coffee-like flavors.

Unlike corn syrup, the predominant grain-derived sweetener used today, malt syrup has been around for several millennia. See corn syrup. According to the food writer Harold McGee, malt syrup and honey were the primary sweeteners in China from around 1000 b.c.e. to 1000 c.e. Table sugar was too expensive for the peasantry, but malt syrup could be made from common household grains, such as rice, sorghum, and wheat. The classic sixth-century Chinese text Qímín Yàoshù (Essential Techniques for the Welfare of the People) includes chapters on how to prepare sprouted grains and how to extract malt sugar, or maltose. Malt syrup and maltose remain important ingredients in traditional Chinese confections such as Ding Ding Tong and Dragon’s Beard Candy. See china.

Malt syrup was not produced on a commercial scale in the United States until around 1920, when persistent sugar shortages led to greater interest in alternative sweeteners. See sugar rationing. Malt syrup was particularly attractive because it offered breweries devastated by Prohibition a potential new revenue stream. Instead of using malted barley as one of the four main ingredients in beer (along with hops, yeast, and water), some breweries simply canned malt syrup and sold it to consumers for use in cooking and baking. This “liquid malt extract” had good culinary uses, but it was also sold with a wink, since consumers could use the cans to illegally brew beer in their homes. Indeed, the LA Brewing Co. sold a malt extract that included a “Bohemian” hop flavoring, obviating the need for consumers to procure hops.

Malt extracts remain popular with home brewers today, but a greater volume of malt syrup worldwide goes into baking, confectionery, and even breakfast cereals. All malt products can be classified as diastatic (containing active enzymes) or nondiastatic (with enzymes inactivated by high processing temperatures). When diastatic malt products are used in baking, the enzymes can increase fermentation activity, helping to condition the dough. Care must be taken not to overuse diastatic malt or the finished product will come out “over-proofed,” smelling of alcohol. Malt syrup also aids in the caramelization, or browning, of bread and pizza crusts, and dark malt extracts do the same in hearth breads. Of course, malt flavor is delicious in its own right, regardless of malt’s functional attributes, and barley malt syrup is an essential ingredient in New York–style bagel recipes. In the United Kingdom, malt is the key ingredient in malt loaf, a sweet, dense, chewy loaf of bread. Light malt extracts lend many breakfast cereals sweetness and color. See breakfast cereal.

Barley malt extract also appears on the ingredient lists of numerous popular confections and malt-based beverages. In the United Kingdom, Mars makes Maltesers, round milk chocolates with malt honeycomb centers; their United States counterpart, Whoppers, are malted milk balls produced by the Hershey Company. See hershey’s and mars. Both contain malted milk, a powdered blend of whole milk, malt extract, and wheat flour that was invented by William and James Horlick and trademarked under the “malted milk” name in 1887. Malted milk became a mainstay of soda fountains in the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with soda jerks adding malted milk powder to milkshakes to form “malts.” See milkshakes and soda fountain. When light malt extract is incorporated into ice cream recipes, it helps control crystallization and imparts a rich toasted flavor.

As a sugar substitute, malt syrup has generally enjoyed a healthful reputation. In 1889 the Scotsman John Montgomerie filed an application for a U.S. patent on digestive biscuits, claiming his “malted bread” would make “nourishing food for people of weak digestion.” Today, over 71 million packs of Digestives are sold every year in the United Kingdom. Ovaltine, a powdered malt mix invented in the late nineteenth century by a Swiss chemist, was a nutritional supplement believed to be especially good for infants, and by the early twentieth century it had become a popular children’s drink in the United States and United Kingdom, often replacing hot chocolate. In the twentieth century, malt extracts often included cod liver oil to boost its value as a dietary supplement and to protect against rickets. Today, as fructose has fallen out of favor, malt syrup advocates may point to the absence of fructose in maltose. Maltose is a disaccharide, a combination of two glucose molecules, while sucrose (table sugar) is a combination of glucose and fructose. Malt syrup also contains some minerals and vitamins not present, or only minimally present, in other sweeteners. The recent rise of gluten-free dieting has made malt syrup a somewhat less desirable sweetener for many manufacturers. General Mills replaced malt syrup with molasses in their flagship Chex cereal and now advertises all but the Wheat Chex flavor as gluten-free.

See cassava.

manjū, a traditional Japanese sweet, are steamed, stuffed buns made from wheat, rice, or buckwheat flour. Sweetened azuki paste (an) is the most common filling for manjū today, but the earliest manjū were vegetarian versions of meat buns. See azuki beans. According to one of many stories about their origin, Zen monks brought the recipe for manjū to Japan from China in the Kamakura era (1185–1333). The monks ate manjū stuffed with vegetables as snacks, sometimes in a broth. During the Muromachi period (1336–1573), peddlers dressed as monks sold savory manjū in medieval cities. By the late 1600s, “sugar manjū” stuffed with azuki paste became more prevalent than the savory type. The elite adopted manjū for use in the tea ceremony but commoners also enjoyed them, and the sweet remains one of the most popular of traditional confections in Japan, where there are many varieties. The flour to make Sake Manjū is kneaded with amazake (a rice beverage made from rice, water, and kōji—the mold Aspergillus oryzae), which imparts a tangy taste. Chestnut Manjū contain pieces of chestnut mixed with the sweetened azuki paste. Rikyū Manjū, alleged to be a favorite of tea master Sen no Rikyū (1522–1591), have brown sugar mixed into the flour. Tea Manjū are made with powdered green tea. Hot-spring resorts sell Hot Spring Manjū cooked by the steam of the hot spring. Savory versions of manjū survive as buns stuffed with meat (nikuman) or curry (karēman).

manna is the magical biblical substance provided by God to sustain the Israelites as they wandered in the wilderness of Sinai for 40 years after the exodus from Egypt until they arrived in the land of Canaan. The name of the food itself evokes wonder and mystery. When the Israelites first saw it, they asked one another, “What is it?” (Hebrew, mān hû’ [Exodus 16:15]), which yielded the name of the substance (in Hebrew, mān). The earliest Greek translators of the Hebrew Bible associated the sound of the word with Greek manna (meaning “morsel” or “crumb”), which became the standard term in English and other European languages.

The Israelites’ question has confounded biblical readers since antiquity. The collection of disparate properties ascribed to manna cannot be reconciled perfectly with any known natural substance, a situation that underscores manna’s inherent malleability as a symbol. It is first described as “bread from the heavens,” which appeared daily with the morning dew as something “fine, flaky; as fine as frost on the ground,” and which would melt when the sun grew hot (Exodus 16:4–21). It is said to look “like coriander seed” and its color is either “white” or “like the color of bdellium,” a yellowish gum resin. Its taste was like “wafers in honey” or “the cream of oil” (Exodus 16:33; Numbers 11:7–8).

The Israelites were permitted to gather only enough manna each morning for a single day, since it would spoil rapidly and breed worms, except on the Sabbath, when the double portion collected the day before was miraculously preserved (Exodus 16:19–30). Manna could be boiled or baked, and in one detailed account the Israelites are said to “gather it and grind it between millstones or pound it in a mortar, and boil it in a pot and make it into cakes” (Exodus 16:23; Numbers 11:8). As is often the case with sweets, an all-manna diet eventually sickened the Israelites and drove them to violent complaint against God, who responded by forcing them to eat only quail meat until it came out of their noses (Numbers 11:4–20). Both the crime and the punishment highlight the principle that too much of a good thing can lead to dissatisfaction.

The manna stopped appearing as miraculously as it had begun once the Israelites reached their Promised Land. Its sustaining power was commemorated by the eternal preservation of one portion in a jar placed in front of the Ark of the Covenant (Exodus 16:34–35; see Hebrews 9:4), as well as by later references to its demonstration of God’s nourishing spirit (Deuteronomy 8:3; Nehemiah 9:20; see John 6:31). Early postbiblical Jewish texts emphasized this aspect of manna by calling it “food of the angels” and a manifestation of God’s “sweetness toward children” (Wisdom of Solomon 16:20–21), and further claimed that in the messianic kingdom God would feed the righteous with manna (2 Baruch 29:8).

Since antiquity attempts have been made to associate the biblical manna with natural phenomena in the Sinai Desert. Building on a tradition that goes back to the Hellenistic Jewish historian Josephus, many modern scholars have identified manna with a secretion produced by insects on the tamarisk tree (Tamarix mannifera), which shares several properties with honeydew produced by plant lice in the region. See insects. Others have argued for a connection with a species of lichen (Lecanora esculenta) often spread by the wind in large quantities through the Central Asian steppes, although this species is not found in the Sinai region. Nevertheless, the symbolic demands of the biblical narrative prevent any perfect identification.

Ancient rabbinic tradition preferred to emphasize the wondrous nature of manna. It was thought to be one of 10 things produced at twilight on the sixth day of creation for the eventual preservation of humanity, alongside such items as Moses’s rod, the rainbow, and the tablets of the law. It fell from the sky every day together with gemstones and pearls. It was used as perfume and cosmetics by the Israelite women. It was called the “food of the angels” because, like the angels, those who ate it did not have to relieve themselves since the manna was absorbed entirely into their bodies. Some sources claimed that manna could assume the taste of whatever food a person desired. Others argued that its taste differed according to the condition or age of the person eating it: to little children it tasted like milk, to youths like bread, to the elderly like honey, and to the sick like barley soaked in oil and honey.

Whether or not a scientific explanation can be offered, the various descriptions of manna associate it with another important symbolic food for the Israelites: honey. See honey. The country promised throughout their manna-eating journey is called a “land flowing with milk and honey” (e.g., Exodus 3:8), and manna shares both its sweetness and preservative qualities with honey. Likewise, the dual sustenance provided by manna and water in the desert suggests a parallel to the divine food and beverage of the ancient Greeks, ambrosia and nectar, which are also closely connected with honey.

See also christianity; judaism; and symbolic meanings.

maple sugaring is the practice of making maple syrup from the sweet sap that flows from sugar maple trees in late winter–early spring. Owning a sugar bush—a stand of sugar maple trees—and a sugar house, and annually harvesting sap to make maple syrup, persists as a rural family tradition throughout New England, the Upper Midwest, and southeastern Canada. Only in these regions are there forests of trees full of running sweet sap, and this sap runs for only one or two months a year. Each spring, thousands of people go into the woods to tap the maple trees, harvest the sap, and move the sap into the many small sugar houses (or, in Canada, sugar shacks) that dot the region’s heavily wooded landscape. Now a practice known to many, sugaring has long been a visible part of communities and landscapes in the northern forests of North America.

Sugaring is a communal practice. Maple trees grow interspersed with many other tree species (pine, birch, oak) in the forested landscape, and sugaring season draws many people into the woods to help with the harvest. There is only a small window of time when this can happen, which requires warm days and cool nights that permit the tree temperatures to hover between 40 and 45°F (4 to 7°C). People have to collect sap and boil it into syrup nonstop, day and night, an activity that leads to much conviviality: in Vermont, the tradition is boiling hot dogs in the evaporating sap for dinner; in Quebec, eggs are boiled in it for breakfast. In How America Eats (1960) food writer Clementine Paddleford described her foray into sugar making and tasting sap: “We drank sap fresh from the pail, a clear white liquid, like sweetish rainwater. It tasted of sun, of the earth and the weather.” Maple sugaring is a social and sensory experience.

This 1940 photograph shows a young woman, Julia Fletcher, gathering sap from sugar maples on Frank H. Shurtleff’s farm in North Bridgewater, Vermont. Sugaring remains a social event that draws people into the woods to help with the harvest. photograph by marion post wolcott (1910–1990) / library of congress

Sugar Houses or Cabanes à Sucre

Sugar houses are the descendants of earlier open sheds that provided some protection for the large iron kettles used before the nineteenth-century invention of stainless-steel evaporators. Sugar houses vary in size and appearance but generally consist of one main room with a side room or two for wood, propane, and other materials needed to help the sap evaporate into syrup. Almost exclusively made of wood, sugar houses tend to have a steeply pitched roof to prevent pileups of snow, as well as a few windows to help let out the steam generated from the evaporator. Spending time in the sugar house with friends and family is commonplace, a rite of spring.

Unlike other functional buildings populating the region’s still primarily agrarian and wild landscape, sugar houses are seen to be centers of both instrumental and social activity. Many, if not most, sugar makers sell their maple syrup. But when it is time to boil, the sugar house is transformed by the people who have come to talk, share food and drink, and help with the sugaring. The allure of maple sugaring may lie in being able to be with friends and family, warm in the middle of the snowbound landscape of late winter when sap is most often boiled. Sugaring stories often evoke an idealized view. As John Elder writes: “The sugarhouse was a beautiful sight when we arrived in the dusk. Steam was billowing out of the louvers we had so laboriously built, and a golden light from the Coleman lantern within was shining out of the open door … illuminating both the steam and the smoke from our chimney” (2001, p. 92). It is in the sugar house that all the new season’s maple syrup is first tasted and crucial decisions are made: the grade of each run, the possibilities for blending, the markets for selling, and the gifts to give to friends.

As a centuries-old tradition, sugaring involves many rituals. One is the annual sugar-on-snow party. These parties are held in small sugar houses but also at large maple festivals. There are many unconfirmed stories as to the origin of sugar-on-snow events, but what needs to happen is confirmed. Hot, thickened syrup is poured onto snow, creating a lacy pattern. By cooking the syrup to 234°F (112°C), it becomes thicker and develops a caramel flavor. When the syrup is poured onto the snow, the syrup hardens and contracts, creating a maple taffy of sorts. This taffy can either be eaten straight off the snow or twirled around a wooden stick. In some locales, the taffy is named “leather aprons” (in French Canadian, it is called tire d’érable). The resulting confection is served with a pickle and an unsweetened doughnut. See doughnuts and taffy. Sugar-on-snow is simultaneously hot and cold, sweet and sour, and making this dish remains part of the vibrant celebration of the North American sugaring tradition.

See also maple syrup.

maple syrup is a sweetener made from intensive evaporation of the sap of maple trees. Most maple syrup is made by harvesting sap from the species Acer saccharum, the sugar maple. Sap can also be harvested from Acer nigrum (black maple), Acer rubrum (red maple), and Acer saccharinum (silver maple), but none have sap as sweet as the sugar maple. Sugar maple trees grow almost exclusively in the northeast region of Canada and the United States. Some stands may be found as far south as Georgia, but the larger tracts needed for sugaring are found primarily in the northern forest. Most of the commercially produced maple syrup comes from the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick, Ontario, and Quebec and the American states of Vermont, New Hampshire, New York, and Maine.

Sap is the lifeblood of any tree, bringing nourishment (water, sugar, nutrients) from the soil up to the branches, leaves, and fruit. See sap. The uniqueness of the species Acer saccharum lies in its high percentage of sugar. Maple syrup is primarily sucrose, although some syrups, usually the darker ones, can also contain fructose and glucose. See fructose and glucose. There are certain times of year when the sap flows the sweetest, generally as late winter turns to early spring. When the wood of the tree reaches the right temperature, between 40 and 45°F (4 to 7°C), the starches turn to sugars, and sweet sap begins to flow. The sap is harvested by “tapping” the trees. It takes 40 gallons of sap to make 1 gallon of syrup because what comes from the trees is primarily water. Making maple syrup is a major exercise in evaporation. See maple sugaring.

Maple sugaring long predates the establishment of strong national borders between the United States and Canada; fur trappers and traders were aware of and possibly trading syrup by the early 1700s. As early as 1672, a French Catholic missionary, during a journey on the northern side of Lake Huron, wrote of a baptism where “maple water” was used. In Vermont evidence exists that the Abenaki people taught the colonists how to gouge the sugar maple tree with an axe and then use bark buckets to collect the sap; settlers called maple syrup “Indian molasses.” See native american. By 1749 other settlers were writing about harvesting sap and boiling it down to maple syrup in large ironware kettles. In northern New England and southeastern Canada, most rural families owned lands with a “sugar bush,” a stand of sugar maple trees. For most early settlers in the region, maple syrup was the only available sweetener, and more often than not the syrup was cooked down until it crystallized into maple sugar because it was easier to store. People would hack pieces from tubs or blocks of sugar to use either whole or heated back into liquid form.

Technologies of Production

The methods of procuring sap and making syrup used by the Native Americans and early settlers relied completely on natural conditions. Reed, bark, or wood spouts were used to draw off the sap into clay or bark vessels. The sap was boiled into syrup in large kettles, usually suspended by a metal rope hanging from a pole, over a constantly stoked wood fire. The pole was held up by two forked stakes. By the mid-1800s much of the process was brought indoors, initially in an open shed where the kettles were placed underneath the roof but still hung over an open fire. Later, enclosed structures and more efficient means of moving the sap from the trees to a holding tank and then to an evaporator were developed. By the late nineteenth century metal evaporators had been introduced. They were invented by David Ingalls in Dunham, Quebec, and soon updated and adopted by New England sugar makers. This technological innovation, along with others, allowed for the development of commercial maple syrup production. By the twentieth century the making of maple syrup had moved beyond the backyard woodlot.

Maple sugaring is an old-fashioned practice open to new technologies. One of the first was the invention of metal taps that could be inserted into trees to direct the flowing sap into metal buckets, which were then transferred into larger containers and transported by horse and wagon to the sugar house. Images of this process are still found on many jugs of maple syrup. Although taps are still central to the process of harvesting sap, today most maple sap is transported from the sugar bush by means of plastic tubing, with gravity or vacuum extractors pushing down the sap directly into the sugar house. There, machines perform reverse osmosis to remove much of the water from the sap. All this occurs before the sap is ever funneled into the flat metal evaporators that a century earlier had transformed the production of maple syrup and created new markets for this wild food.

Maple syrup is now an agricultural commodity, accounted for and supervised by state and provincial agencies and trade associations. Canada and the United States are the only two maple syrup–producing countries in the world. In 2009 worldwide production of maple syrup was estimated at 13,320,000 gallons, with Canada accounting for 82 percent of that production. Quebec is by far the largest maple syrup producer in Canada, and in the world, with 75 percent of all maple syrup worldwide coming from this province. The central and eastern part of the province is responsible for most of this maple syrup. In the United States, Vermont is consistently the leading producer of maple syrup (40 percent of total production in 2013), followed by Maine and New York. Other states making maple syrup include New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, Ohio, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. In 2013 U.S. domestic production of maple syrup was 3.2 million gallons.

Quebec now sells maple syrup solely under the auspices of the Quebec Federation of Maple Syrup Producers. About 85 percent of production is sold to packers or bulk buyers and exporters who redistribute bulk or prepackaged maple products. These products can be sold to food stores, supermarkets, and gift shops in both domestic and international markets. Producers can sell maple products of only 5 liters or less directly to the consumer. In the United States, by contrast, maple syrup remains primarily a small-scale enterprise for individual sugar makers. In Vermont, it is estimated that over 3,000 people actively tap trees to make and sell maple syrup, with some tapping 100 trees and others tapping thousands. Making maple syrup has become a new growth area in Vermont agriculture. In 2000, 1 million taps were installed; by 2012 there were over 3 million.

Grading and Tasting Syrup

Anyone who wants to sell syrup, whether from the farmstead, to the general store or to major blender/packers, must adhere to state or provincial regulations. The primary regulations seek to ensure that all maple syrup sold is pure (not adulterated) and consistent according to grade. See adulteration. In the United States, grade was usually defined as a combination of appearance by color and density. There have been different names for these grades, but until recently the four grades were Fancy, Medium Amber, Dark Amber, and Grade B. Sitting in a sugar shack, watching the sap evaporate into syrup in the large stainless-steel evaporator, the sugar maker looks for the moment when the density and color are uniform. Density is determined when a small bit of syrup is poured into a hydrometer and measured; the goal is 66 percent or 67 percent Brix (a scale indicating sugar content). See brix. All grades of maple syrup have the same density. As of 2014, all maple syrup produced in the United States and Canada began to use a unified grading system that relies on taste as well as appearance. All maple syrups for consumption are now called Grade A. The four different categories are Golden, Delicate Taste; Amber, Rich Taste; Dark, Robust Taste; and Very Dark, Strong Taste.

The sweet yet earthy complexity of maple syrup means that this wild food is still in demand even though new technologies have created simple and inexpensive sweeteners. In the United States, maple sugar candy remains a popular treat found in shops all over New England. The syrup is cooked at high heat long enough to reach a crystalline stage; it is then poured into molds, often in the shape of a sugar maple leaf, where it cools into a fudge-like candy. Maple butter is made by heating the syrup to the soft-ball stage at 235°F (113°C) and then chilling it quickly and stirring until it reaches a creamy consistency. See stages of sugar syrup. “Sugar-on-snow” is an old-fashioned treat for the sugaring season. Thickly boiled sap is poured in lacy patterns onto snow, where it immediately hardens into a taffy-like confection. Pouring maple syrup over pancakes and waffles for breakfast is a national American tradition, even if many Americans use Aunt Jemima or other “faux” syrups instead of the real thing. See aunt jemima. In Quebec, several desserts made with maple syrup are central to the region’s culinary repertoire, especially pouding de chomeur (poor man’s pudding). This simple dish involves pressing biscuit dough into individual cups or a baking dish, pouring a mixture of maple syrup and cream over the dough, and then baking it in the oven. Tarte au sirop d’érable (maple syrup pie) is like a sugary pecan pie without the nuts.

Maple syrup is a long-lived sweetener with a bright future. Consumers of all types increasingly desire maple syrup, as other sweeteners, such as high-fructose corn syrup and cane sugar seem fraught with problems. See corn syrup. Maple syrup is a flavorful natural product. More demand exists for maple syrup in the United States now than since before World War II, and sugar makers cannot keep up with it. In addition, the syrup is regularly shipped to countries around the globe, including Japan, Thailand, and Australia. Maple syrup is thus not an artifact of a rural agrarian past, but a vital part of everyday life.

marmalade generally refers to a chunky, sweet-sharp, semi-liquid jelly laced with chopped Seville (bitter) orange peels. Although the word “marmalade” may be applied to other fruits or vegetables suspended in jelly, according to a 2001 law, products labeled as marmalade in the European Union must be made with citrus fruit only. A mainstay of British breakfasts, marmalade is typically eaten on buttered toast. It has been extolled by writers and poets from T. S. Eliot to Ian Fleming (James Bond enjoyed Frank Cooper’s marmalade at breakfast every day).

The Portuguese marmelada, from which the English “marmalade” derives, comes from marmelo, or quince. The origins of today’s preserve date back over 2,000 years to a solid cooked quince and honey paste similar to contemporary membrillo, the Spanish quince paste. See fruit pastes. Used as a preserve and reputed remedy for stomach disorders in ancient Greece and Rome, quince marmalade was eagerly taken up by the Spanish and Portuguese during medieval times after they learned about it from the Moors, who had settled the Iberian Peninsula in the eighth century. In the late Middle Ages, marmalades began to be sweetened by sugar rather than honey, a transition that continued into the sixteenth century.

The first shipments of marmelada, packed in wooden boxes, arrived in London in 1495. Expensive and imbued with purported medical and aphrodisiac powers, it was a popular food among noble families, who served it after feasts as a digestive sweetmeat. Around this time, northern Europeans also prepared cooked quince and sugar preserves called alternately chardequince, condoignac, cotignac, or quiddony.

The Scots pioneered marmalade’s switchover from quince to bitter orange in the eighteenth century. The preserve’s texture was now thinner, and it was served as a breakfast and teatime spread rather than as an after-dinner digestive. By the late nineteenth century, orange marmalade was being mass-produced by venerable British firms, including Frank Cooper and Keiller’s.

As the British Empire expanded, orange marmalade traveled to British colonies around the globe. It was never embraced as a spread as enthusiastically in the United States as in Britain but was used more often as a flavoring for baked goods. Because Seville oranges are available for only a few weeks in January and February, contemporary home cooks view marmalade making as a seasonal ritual.

See also fruit and fruit preserves.

Mars, Inc. is the largest candy company in the United States, boasting such venerable brands as M&M’s, Milky Way, Three Musketeers, Snickers, Skittles, Starburst Fruit Chews, and Twix. With its purchase in 2008 of the chewing gum giant Wm. Wrigley Jr. Co., it added brands like Life Savers, Altoids, Doublemint, and Orbit to this iconic lineup, becoming a confectionery behemoth with global sales estimated at more than $30 billion. It is one of the largest privately held firms in the United States, being wholly owned by the Mars family of northern Virginia. The company operates a pet food division and owns Uncle Ben’s Rice and other food brands, but the majority of its sales derives from candy brands that are household names worldwide.

Mars’s beginnings are twofold, stretching back to the turn of the twentieth century when Frank C. Mars watched his mother cooking. Frank was a sickly child, struck by polio, and spent practically all of his youth indoors. He soon found he had a knack for making confections. At age nineteen, he struck out on his own, selling his candies door-to-door to small shopkeepers in and around Minneapolis-St. Paul. In 1902, the same year he opened his firm, he married Ethel G. Kissack; their only son Forrest was born two years later. But the business was not successful, and in 1910 Ethel filed for divorce, sending Forrest to live with her parents in Canada. Soon afterward, Frank remarried (another Ethel, coincidentally) and moved west to Seattle, where he tried his hand at a new business, but it, too, failed. Returning to Minneapolis-St. Paul, with no available credit, he and Ethel set up shop in a modest room above a kitchen, and Frank began making small batches of candy that Ethel took to sell on the trolley cars each morning. The biggest seller was a butter-cream concoction that eventually made its way into Woolworth and a dozen or so smaller retailers. By 1923 Frank Mars had finally found success. But what happened next is where the story gets sticky. To hear Frank Mars’s son Forrest tell it, Forrest is the one who gave Frank the idea that turned the business into a million-dollar enterprise.

Father and son had not seen each other since the divorce, but they happened to meet when Forrest was working one summer as a traveling salesman while attending college at Yale. During lunch at a five-and-dime, while they were drinking malteds, Forrest claims he came up with the idea to put the flavor of a malted milk shake in a candy that could be sold nationwide, not just locally. Based on that advice, Frank Mars invented the Milky Way in 1924, a combination of caramel and fluffy nougat surrounded by a solid coating of chocolate. The Milky Way was strikingly different from competing bars. First, the chocolate covering kept it fresh, so it could be sold coast to coast. Second, because malt-flavored nougat—made of egg whites and corn syrup—was the bar’s main ingredient, the Milky Way appeared larger but tasted just as chocolaty and cost less to produce. The Milky Way brought in sales of nearly $800,000 its first year on the market.

Seeing Eye to Eye

When Forrest Mars graduated from college and joined his father’s business, he expected to be rewarded handsomely for his contribution. But the two men did not see eye to eye. Forrest wanted to expand the business rapidly, into Canada and beyond. However, Frank Mars had failed many times before striking it rich with the Milky Way, and he did not share his son’s enthusiasm. After Forrest threatened and insulted him, Frank decided he had no choice but to buy his son out of the business, giving him $50,000 if he would disappear and never contact his father again.

Undaunted, Forrest Mars set out for Europe to seek his fortune. He traveled to Switzerland first to learn the fine art of making chocolate and then settled in England. In the small industrial town of Slough outside London, he set up shop in a tiny factory with some second-hand equipment and began making a version of his father’s Milky Way bars, which he egotistically dubbed the Mars bar. Unable to afford to manufacture his own chocolate, he purchased his chocolate covering from Cadbury and sweetened the bar slightly to appeal to British taste. See cadbury. He traveled to London to sell the bars to shopkeepers himself and soon acquired a loyal following. By the end of 1933, the Mars bar’s popularity had grown to the point where Forrest could enlarge the factory and automate it, and soon sales expanded into other European countries. The success of the Mars bar abroad soon rivaled the success of its American cousin and became the foundation for an empire that quickly eclipsed Frank Mars’s U.S. firm.

Brand Confusion

Forrest nevertheless was not satisfied until he regained control of his father’s Chicago-based business in 1960, finally reuniting his firm with its American counterpart. In the meantime, Forrest had founded M&M’s in the United States, which went on to lead the American candy conglomerate, now renamed Mars, Inc., with headquarters just outside of Washington, D.C.—a fact that surprises many Europeans who have always considered Mars a British-based company. Mars, Inc.’s two-pronged beginning has also resulted in continued confusion over the Mars and Milky Way brands. In the United States the company sells a Mars bar, but it is not the same as the British Mars bar, which is really an anglicized version of the Milky Way. Instead, the American Mars bar has caramel, nougat, and whole almonds buried inside, and it is covered in a thick milk chocolate coating.

The firm’s global beginnings have given it an unprecedented advantage in the modern age, for Mars, Inc. was a global powerhouse long before the idea of global brands became necessary in the age of the internet. The firm operates on six continents and in more than 180 countries. The Mars family has always understood that the world is, in fact, a very interconnected place, and their business reflects that global pursuit. From the beginning, Forrest Mars said he wanted to build a global empire, and that is exactly what he did. He died in 1999 at the age of 95.

See also candy bar; chewing gum; life savers; and m&m’s.

Marshall, Agnes Bertha (1855–1905), was among the foremost Victorian cookbook writers. Born in Walthamstow, Essex, she was one of the daughters of John Smith, a clerk, and his wife Susan. Her father died when she was young, and her mother remarried. Sadly, little is currently known of her education or where she learned to cook. The only clue to where she trained may be found in an 1886 interview of her husband in the Pall Mall Gazette: “I should tell you that Mrs. Marshall has made a thorough study of cookery since she was a child, and has practiced in Paris and Vienna with celebrated chefs.”

Agnes Marshall (1855–1905) was one of the foremost Victorian cooks and an extraordinary businesswoman who founded a cookery school, wrote cookbooks, sold hand-cranked ice cream machines and ice cream molds, and started a weekly magazine called The Table. This print is of unknown origin.

Following her marriage to Alfred William Marshall at St. George’s Church, Hanover Square, in 1878, the path of Agnes Marshall’s career becomes clearer. If she were alive today, Mrs. Marshall would be judged a formidable force in business; for a Victorian woman, she was truly extraordinary. In 1883, following her purchase of property on Mortimer Street in London (a very unusual transaction, since women had earned the legal right to purchase property, particularly with their own money, only in 1870), Mrs. Marshall opened a cookery school. She started with no pupils on the first day, but a year later she was demonstrating to classes of up to 40 people, five or six days a week.

In 1885 The Book of Ices was published, followed by Mrs. A. B. Marshall’s Book of Cookery in 1888, Mrs. A. B. Marshall’s Larger Cookery Book of Extra Recipes in 1890, and, finally, Fancy Ices in 1894. See ice cream.

Prompt to respond to commercial opportunities, Mrs. Marshall offered a range of hand-cranked ice cream machines, which even today prove to be faster and more reliable when pitted against modern electric machines. See ice cream makers. Once the ice cream was made, Mrs. Marshall was there to offer a huge range of splendid molds in which to form the ice cream, and ice caves to freeze it solid. See molds, jelly and ice cream. Fancy Ices took her ices to a more elaborate and embellished level, and this book includes the earliest reference in English to putting ice cream in a cone. See ice cream cones.

In 1886, no doubt using the facilities of the cookery school, Mrs. Marshall launched a weekly magazine called The Table, and in 1888 she was the first person to suggest, in the magazine, using liquefied gas for ice cream making at the table. In 1892 she undertook an extensive lecturing tour of major cities in England, taking the stage with a team of helpers to cook an entire meal in front of audiences of up to 600 people.

The staggering scale of Mrs. Marshall’s achievements is arguably unequalled. She was a unique one-woman industry, and her recipes were always concise, accurate, detailed, and successful. She deserves much more credit than she has been given by history.

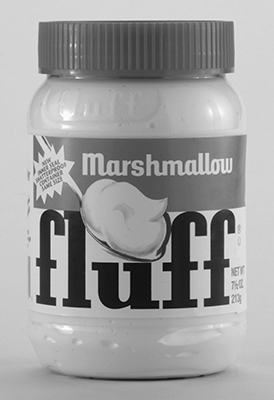

Marshmallow Fluff is an iconic brand of marshmallow cream manufactured by the Durkee-Mower company of Lynn, Massachusetts, since 1920. See marshmallows. The sticky sweet spread is a staple comfort food in New England, where it is best known as an essential layer of the fluffernutter—a Marshmallow Fluff and peanut butter sandwich.

The sugary spread known as Marshmallow Fluff is so beloved in its home state that legislation is pending to make the fluffernutter—a combination of Marshmallow Fluff and peanut butter—the official state sandwich of Massachusetts. © durkee mower inc.

Fluff is also a versatile baking ingredient. It can substitute for marshmallows as a topping on hot cocoa or sweet potatoes, or serve as a sweet adhesive in whoopee pies, frostings, fudge, Rice Krispies treats, meringues, salads, candies, fillings, chiffon pies, sorbets, shakes, and cheesecakes. Diluted, it becomes a dessert sauce.

Durkee-Mower whips Fluff’s four ingredients—dried egg whites, corn syrup, sugar syrup, and vanillin—batch by batch to ensure consistency. The surface of Fluff is smooth like a melted marshmallow, but once breached, reveals a light, stiff porous interior that turns glassy smooth again upon standing. The confection spreads and sticks, but does not drip. It expands and contracts with temperature, requires no refrigeration, and apparently holds up in zero gravity. Sunita Williams, an astronaut and Massachusetts native, squirreled away her own jar of Fluff onboard the International Space Station. For New Englanders like Williams, Marshmallow Fluff is the stuff of home. Generations of northeasterners will argue that Fluff is quintessential to their childhood, be it the wholesome 1950s or the far-out 1970s.

Marshmallow Fluff was invented in 1917 by Archibald Query, a French-Canadian immigrant and candy maker living in Somerville. Query sold the recipe to returning World War I veterans H. Allen Durkee and Fred L. Mower, who founded Durkee-Mower and began selling the concoction door to door. By the 1920s Fluff was being advertised in Boston newspapers. In 1930 the company debuted the “Flufferettes,” a female vocal trio who sang dreamy odes to Fluff on the Yankee Radio Network. In 1961 Durkee-Mower developed the “Fluffernutter” trademark. Around this time, Fluff packaging adopted its signature look—a blue-and-white label sketched in classic “Dick, Jane, and Spot” style and a ruby-red lid. The iconic jar has remained unchanged since, inspiring powerful Pavlovian responses among the long-initiated.

Apart from strawberry and raspberry varieties, released in 1953 and 1994, respectively, Marshmallow Fluff has remained its simple self. The Lynn factory, built in 1950, remains Fluff’s sole locus of production and uses the same basic methods and machinery from that era. The company has not changed its jar design since 1947 and rarely advertises. Although Fluff can be found in 28 states and 10 countries, the vast majority is sold in upstate New York and New England. In these regions’ grocery stores, Fluff can be found in its familiar place alongside the peanut butter, no mere third wheel to jelly.

Marshmallow Fluff is not the only commercially available brand of marshmallow cream. Kraft has marketed Jet-Puffed Marshmallow Crème since 1961, and Limpert Brothers, Inc., of Vineland, New Jersey, has sold a more syrupy marshmallow cream as an ice cream topping since 1913. Paradoxically, Limpert Brothers also markets its product under the name Marshmallow Fluff. In one of the stranger deals in American business, Limpert Brothers and Durkee-Mower agreed to share trademark rights in 1939, provided that Limpert Brothers sold wholesale and Durkee-Mower sold for individual use only, except in New England. The two Fluffs are, in a sense, nonoverlapping magisteria.

In 2006 Marshmallow Fluff’s retro reputation found itself in the crosshairs of the twenty-first-century fight against childhood obesity. Massachusetts State Senator Jarrett Barrios proposed limiting servings of Marshmallow Fluff in public school lunches to one per week. Indignant, Massachusetts State Representative Kathi-Anne Reinstein counterclaimed that the fluffernutter ought to be crowned as the state sandwich.

Barrios, who was not raised in Massachusetts, did not anticipate the public outcry he encountered. He quickly rescinded his proposal and promised to support Reinstein’s instead. His spokesman assured the Associated Press that Barrios loved Fluff as much as the next legislator.

That same year, the annual “What the Fluff” festival debuted in Archibald Query’s hometown of Somerville. Billed as an “ironic tribute,” the recurring festival has featured Fluff cook-offs, Fluff-inspired games, Fluff-sculpted hair-dos, Fluff science experiments, and impersonations of Query and the Flufferettes. The outpouring of love has proven anything but ironic—the festival draws several thousand people every year.

marshmallows are light, spongy confections made of sugar or corn syrup, water, and a gelling agent that have been whipped and set to capture an airy density. The modern marshmallow is also typically coated in cornstarch, sugar, or chocolate, as naked marshmallow is pertinaciously sticky to the touch.

The marshmallow takes its name from the marsh mallow (Althaea officinalis), a wetland weed native to Europe. A spitting image of its cousin the hollyhock, the marsh mallow sports a tall, sturdy stalk and pale pink flowers. Mucilage (similar to sap) is found throughout the plant’s body but especially in its thick, fibrous root. Physicians of the ancient world recommended extracting the mucilage by boiling the root and consuming it with milk, honey, or wine to cure a variety of ailments. The Greek naturalist Theophrastus noted that meats cooked with marsh mallow cleaved together—a dramatic exhibition of the plant’s supposed flesh-healing powers! In fact, he was witnessing the stickiness that would make the mucilage the first gelling agent of the marshmallow.

Over the centuries, marshmallow mucilage proved most effective as an antidote to cough and sore throat. (Modern medical studies have verified that marshmallow root does indeed soothe inflammation in mucous membranes.) In the nineteenth century European physicians prescribed boiling down the mucilage with sugar to create a palatable cough syrup. In France, the mucilage was whipped with sugar and egg whites to create lozenges. See lozenge and medicinal uses of sugar. By century’s end, French confectioners had dropped the medicinal mucilage for more readily available gelatin. The French also traditionally used rosewater to flavor their marshmallows, which emerged a delicate pink. Although marshmallows may have lost their eponymous ingredient, in France today they can still be found blushing a similar hue as the mallow’s blossoms.

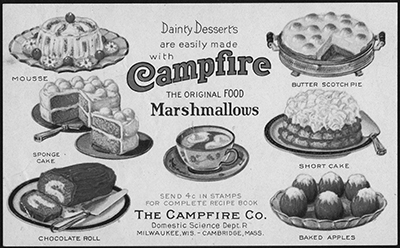

This advertising card, produced by The Campfire Co. sometime around the turn of the twentieth century, encouraged consumers to use marshmallows in their dessert recipes. For centuries confectioners had made marshmallows in individual batches, but by the early twentieth century, automation meant that these treats could be mass produced. boston public library

In the nineteenth century marshmallows immigrated to the United States, where their next major innovation awaited. At the time, confectioners made marshmallows by whipping the necessary ingredients and letting the foam set in individual cornstarch molds. By the early twentieth century, however, marshmallows could be produced in large batches. In 1954 Alex Doumakes, of the American marshmallow company Doumak, invented an extrusion process by which marshmallows were forced through a chute and cut to their desired size. The innovation reduced the time required to make a marshmallow from 24 hours to 1 hour.

Today, marshmallows are mass-produced and sold throughout the Americas, Europe, and Asia. Although they can be eaten plain, they are often gussied up in various candy iterations. Peeps and Circus Peanuts, for example, cast marshmallows into whimsical shapes. See peeps. In Japanese Tenkei candies, marshmallows are filled with jam or cream. Mallomars and MoonPies pair chocolate-coated marshmallows with graham cracker. See moonpies. Chocolate-covered marshmallows are popular the world over, but the French are especially attached to their chocolate-coated marshmallow bears, an iconic childhood treat.

Marshmallows are also a versatile ingredient, lending their fluffy sweetness to fruit salads, cookies, Rice Krispie treats, and rocky road ice cream. In 1917 Angelus Marshmallows (once made by Cracker Jack) commissioned a recipe booklet to popularize novel uses of marshmallows. Thanks to the booklet, they became a favorite topping for hot cocoa and for sweet potatoes, especially at Thanksgiving.

These seasonal uses hint at another fateful property of the marshmallow: thermoreversibility. That is to say, marshmallows can revert to their original viscous state when heated. Quick to note the gooey lusciousness of a toasted marshmallow, the Imperial Candy Company launched the Campfire Marshmallows brand in 1917, explicitly promoting the candy as a camping staple. Before long, campers were sandwiching toasted marshmallows between graham cracker and chocolate, and the s’more was born. See s’mores.

The most recent development in marshmallows has been toward batch-made boutique brands. Countering the homogeneity of mass-produced marshmallows, independent confectioners experiment with different densities, flavors (by adding fruit syrups, herbs, or spices), and textures (by coating with cookie crumbs, bacon bits, or the like). A British company has fully realized the marshmallow as a blank canvas by custom-printing marshmallows with clients’ personal photographs. Marshmallows can also be modified by replacing the usual gelatin with fish gelatin (for kosher marshmallows) or agar (for vegan ones).

Culinary developments may aim to sophisticate the humble marshmallow, but the confection’s lasting cultural impact seems tied to childhood. Some American cities celebrate Easter with “marshmallow drops,” events in which helicopters rain marshmallows on earthbound children. Popular toy blow-guns made of PVC pipe shoot miniature marshmallows as ammunition. In the movie Ghostbusters (1984), marshmallows are forever personified by the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man, a cartoonish villain of bloated, springy step. In the world of psychology, Stanford researcher Walter Mischel’s famed “marshmallow test” of 1970 presented children with a feat of forbearance—eat one marshmallow now or wait 15 minutes to be rewarded with two—and immortalized the marshmallow as the supreme symbol of temptation.

See also ancient world; children’s candy; gelatin; japan; and marshmallow fluff.

marzipan is a firm paste of finely ground nuts, almost always almonds, and sugar, sometimes bound with either whole eggs or egg whites. It may be scented with rosewater or orange flower water, but the main flavor and aroma come from the nuts. As a result of its fine flavor and versatile texture, marzipan has many uses in confectionery, baking, and dessert making, working equally well in baked and unbaked goods. It can be modeled or molded into shapes, used as a covering for celebratory cakes, rolled thinly as a layer in pastries, or baked into biscuits and petits fours. It has been a prime component in fancy baking and decorative sugar craft over many centuries, and remains an important celebratory confection, particularly for a wide range of festival and holiday sweetmeats. See holiday sweets.

Mixtures of honey and nuts, which have been known for thousands of years, are the precursors of many sweet nut confections, marzipan among them. However, it is the cultivation and refinement of sugar in sixth-century c.e. Persia that we have to thank for the development of the fine, long-keeping sugar–nut paste we know as marzipan today. See sugar and sugar refining. In English, we use the German name marzipan, and that nation is still renowned for its very fine product. Debate persists over the origin of the word, but it seems to have come initially to southern France and Italy from the Persian and Armenian marzuban, applied to jewel boxes and both the wooden box and marzipan it contained, only later evolving to focus on the contents. The French (massepain), Spanish (mazapán), and Italian (marzapane) words may also refer to either the month of March or to pastries and bread, hinting at a connection with a time of year or simply to confectionery in general. In England, the earliest marzipan cakes were similarly called “marchpane,” and these flamboyantly iced, gilded, and decorated sweetmeats certainly sound like festive jewels for the dessert table.

How to Make Marzipan

There are several techniques for making marzipan, depending on the desired consistency. Whereas homemade marzipan is generally raw, confectioner’s marzipan is gently cooked to 356–392°F (180–200°C) to both sterilize and manage the moisture content, which according to European Union rules should be no higher than 8.5 percent. Great care must be taken to ensure that the nuts are not overworked to the extent that they become oily. Bitter almonds may be added in small proportions to enhance the almond flavor, which may be more or less desirable depending on the intended use of the marzipan.

Homemade Marzipan

Most domestic recipes call for 2 parts ground blanched almonds and 1 or 1 ½ parts fine confectioner’s sugar. These ingredients are kneaded together with either egg white or egg yolk, the latter often specified in recipes for celebratory cakes, where the whites are used for the icing.

Raw Marzipan

This is the basic professional-grade marzipan, consisting of 2 parts almonds to 1 part sugar. The almonds are blanched and skinned, and left to soak in cold water until use. The nuts are ground with the sugar in fine granite rollers, using water to reduce oiling. The mass is then gently cooked in a double-walled pan, to sterilize it and reduce the water content, until almost dry to the touch.

French Marzipan

To make a whiter French marzipan, the almonds are ground before sugar syrup or glucose is added. See glucose. The mixture is cooked to a smooth paste, which is then turned out onto a slab and spread thinly to cool quickly.

Macaron Paste

For this version, blanched almonds and sugar are milled along with egg white. More egg white is added depending on the final desired consistency, in a proportion of up to one-tenth of the weight of the nuts. See macaron.

Variations

Although true marzipan is made with almonds in a 2 to 1 proportion of nuts to sugar, a number of variations exist:

Uses of Marzipan

Marzipan is a crucial ingredient in numerous cakes and breads, from German stollen to Danish Kransekage, as well as being a filling for pastries. See stollen. It is also formed into quite specific sweets and cakes, many of which are traditional for special occasions or festive times of year.

Modeling and Molding

Marzipan’s firm yet pliable texture allows it to be formed into intricate models of every imaginable shape and size. Colorful marzipan fruits and animals for Christmas and for Easter eggs and lambs are produced all over Europe. Many of the forms are traditional, such as German breads (Marzipanbrot) and potatoes (Marzipankartoffeln) for Christmas, or Martorana fruits, also known as pasta or frutta reale, made for All Saint’s Day in Sicily. Forms may be modeled by hand, and either painted, sprayed, or rolled in edible dyes or powders to enhance a realistic finish. Others are shaped in metal or plastic molds. Wooden molding boards are used for making evenly sized and shaped pieces—round, oval, or pear-shaped—for enrobing in chocolate. All kinds of marzipan sweets may be finished using special tools such as cutters, nippers for edge crimping, and decorative rollers for making uniform patterns on marzipan sheets. See confectionery equipment.

Cakes

A thick layer of marzipan between the fruitcake and icing is a critical element in many large celebratory cakes, such as British Christmas or wedding cakes. See fruitcake and wedding cake. Simnel cake, for Easter, includes a layer of marzipan in its center, and a baked and glazed top layer of marzipan decorated with 11 marzipan balls to represent the 12 disciples minus Judas.

Confections

There are numerous special small marzipan cakes or sweets made in Germany that come from two distinctive schools, those of Lübeck and Königsberg (today’s Russian Kaliningrad). See niederegger. The latter traditionally tastes a little less sweet and comes in the form of petits fours cut with special crimped cutters. The result can resemble a vol-au-vent and be partially filled with boiled apricot jam or liqueur fondant, topped with a firmer fondant and decorated. See fondant. The overall characteristic, though, is to let the pieces set for 24 hours before browning them in a hot oven.

See also cake decorating; flower waters; germany; and nuts.

mastic is the crystallized sap of the mastic tree (Pistachia lentiscus var. Chia), a kind of wild pistachio shrub or small tree. Lentiscus (or Schinus) shrubs grow wild all over the eastern Mediterranean shores, but only on the southern part of the island of Chios do the plants produce mastic. Pink peppercorns (Schinus molle) and sumac (Rhus coriaria) are two other flavorings from plants of the same family that grow in different parts of the world. The word “mastic” derives from the ancient Greek verb mastichao (to gnash the teeth); “masticate” has the same origin.

Mastic crystals were the most glamorous of the various ancient resins, certainly more so than gum arabic or tragacanth. See tragacanth. Chios mastic (masticha) has a subtle, fruity flavor and a distinct sweet aroma that other natural gums lack. These characteristics made it a precious commodity beginning in Roman times. Its crystals were used as chewing gum and breath freshener, as well as medicine. See chewing gum. Recent studies have proven that mastic oil, extracted from the crystals, does indeed possess antibacterial properties that may be beneficial against stomach ulcers.

Since early Byzantine times, mastic crystals have been used as flavoring for mastichato, a most sought-after aperitif mentioned by Alexander Trallianus (ca. 525–ca. 605 c.e.). This drink, along with mastic crystals, used to be Chios’s main export. A similar smooth, mastic-flavored drink is still produced on Chios and is frequently referred to as the “ladies’ ouzo.”

Today, ground mastic is used to flavor breads and cookies in Greece and throughout the Middle East and North Africa. It should be added sparingly, as large quantities yield a bitter and turpentine-like taste. Lokum (Turkish Delight) is flavored with mastic, as is dondurma—the famous Turkish eggless ice cream. See lokum. The enviable, strand-like texture of dondurma is sometimes mistakenly attributed to mastic; however, it is salep, the powerful ancient thickener extracted from the starchy bulb of the orchid Orchis mascula, that gives the frozen dessert its texture. A similar mastic-scented ice cream is called kaimaki in Greece. Ypovrichio (submarine) refers to a spoonful of sugar paste scented with mastic, served submerged in a glass of cold water—hence the name. The anointing oil used by the Greek Orthodox Church includes mastic along with other aromatics.

Mastic production has remained unchanged for centuries. The whole family tends and carefully prunes the trees in winter. In summer, skilled workers make slits on the trunk and lower branches to collect the mastic “tears” throughout the fall. Picking over and sorting the crystals is a long and tedious process. The medieval mastichochoria, the mastic-producing villages of southern Chios, were built by Genoese rulers between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Unlike other villages of the island, they are constructed around central towers, with tall external walls that offered protection from pirates and thieves who coveted the valuable produce. During the more than four centuries of Ottoman rule that followed, mastic production was directly overseen by the sultan.

In recent years, after a period of steady decline, mastic sales have surged worldwide, thanks to research and promotion. In 1997 Chios mastic was named a European Union Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) product. It is now sold as not only a flavoring but also the key ingredient in various health products and cosmetics.

See also greece and cyprus; ice cream; middle east; and north africa.

mead, made from honey, water, and yeast, may be mankind’s earliest crafted alcoholic drink. Honey mixed with water ferments by means of yeasts, both in the air and within the honey itself, which feed on its sugars. See honey. This process would occur naturally if rain chanced to fall into a bowl of honeycomb. Early observers likely took note of the resulting drink’s intoxicating powers and were spurred on to make more.

Many different styles of mead evolved and are still made today. The drink can be dry or sweet, with an alcohol content generally ranging from around 8 to more than 16 percent. Mead can be sparkling, distilled, or spiced. When flavored with herbs and spices, mead is called metheglin, a drink considered to have healthful properties. Cornwall and Wales were known for their mead, and the Celtic words meddyg (healing) and llyn (liquor) provide the etymological root for this drink. Fruit meads, made with honey and fruit juice, are called melomel and have many variations. Pyment is made with grape juice, cyser from apples, black mead from black currants, red mead from red currants, morat from mulberries, and myritis from bilberries.

The ancient Greeks and Romans made many kinds of honeyed drinks. Pliny’s recipe for mead in the first century c.e. was to mix honey and rainwater in a proportion of 1 to 3 and to keep it in the sun for 40 days. A spiced combination of mead and wine called mulsum cheered the chilly Roman troops occupying northern Europe and is thought to be the origin of mulled wine. See mulled wine.

While wine took over in southern countries, honey drinks remained prominent in the north, both as mead and as honey beers. In 300 b.c.e. Pytheas, a Greek mariner, sailed north of Britain for six days and reached a land of barbarians who “from grain and honey made a fermented drink.” Pliny commented on how the people of the British Isles consumed great quantities of the honey brew. In Wales, freemen could pay dues to the king in the form of mead, and a free township had to supply “the worth of a vat of mead to the King, which ought to be capacious enough for the King and his adult companion to bathe in it.”