vacherin is a French dessert consisting of an elaborately decorated meringue shell filled with whipped cream, fruit, ice cream, or sorbet. It is not to be confused with the cow’s milk cheese of the same name that is made in the French and Swiss Alps.

The sweet vacherin is formed by piping a meringue base onto a baking sheet and then building the circumference with rings of meringue, which are then baked at low heat for several hours, until the meringue becomes solid and no moisture is left. See meringue. A variation, vacherin avec couronne en pâte d’amandes, uses rounds of lightly baked almond paste instead of meringue.

The precise origins of the vacherin are unclear. The great nineteenth-century French chef Marie-Antoine Carême is generally credited with the creation of vacherin, as the layering of the piped meringue disks and the dessert’s adaptability to lavish decoration fit his style. See carême, marie-antoine. Since then, many pastry chefs have made the vacherin their signature dessert, creatively imagining new shapes and forms, including rectangles and spheres, and replacing the traditional strawberries or raspberries with exotic fruits and sorbets. The pavlova, a meringue cake with fruit that dates to the early twentieth century, may be seen as a later iteration of the original vacherin. See pavlova.

Valentine’s Day, legends say, metamorphosed from a pagan fertility ritual to a commemoration of Christian martyrs named Valentine, and then to a saint’s day. Today, Valentine’s Day is an international lovers’ celebration and a candy sellers’ delight.

Possibly because of its hypothetical erotic origin, 14 February became associated with love by such writers as Chaucer and Shakespeare. By the eighteenth century, English sweethearts were exchanging handwritten Valentine’s Day love notes. By the nineteenth century, mass-produced paper-lace cards were fashionable in England and in the United States.

Late in the nineteenth century, chocolates, long believed to be an aphrodisiac, became a favored Valentine’s Day gift. The finest were boxed in red or pink heart-shaped containers boasting all the frills, lace, and ribbons of Valentine cards. The English confectioner Richard Cadbury is credited with creating the first heart-shaped chocolate box in 1868. See cadbury and chocolates, boxed.

Other candy makers also profited from the holiday. In the United States in 1902, the New England Confectionery Company (NECCO) began stamping out inexpensive sugary conversation hearts called “Sweethearts.” Still popular today, the tiny candies bear messages such as “Marry Me” or “True Love.” See necco.

Valentine’s Day is celebrated in many countries, with everything from roses to heart-shaped cakes and cookies. But candy, especially chocolates, is among the most popular gifts. Typically, men give candy to women, though in Japan women give candy to men on 14 February, and the men reciprocate in March. See japan.

Tireless promotion of the holiday has led to sweet success for candy makers and retailers. According to the National Confectioners Association, U.S. confectionery sales for Valentine’s Day currently add up to more than a billion dollars a year, 75 percent of which is for chocolate.

See aphrodisiacs and gender.

Valrhona is a high-end French chocolate producer founded in 1922 by pastry chef Albéric Guironnet. The company is headquartered in Tain l’Hermitage, in the heart of Rhône Valley wine country; its name derives from the words “valley” and “Rhône.” Valrhona began exporting to the United States in 1984, and since then it has played an important role in the still-unfolding American chocolate revolution. Prior to the 1980s, little heed had been paid to cacao percentages or origins, and chocolate invariably meant milk chocolate of poor quality.

With the rise in status of American chefs in the 1980s, many restaurants began to hire pastry chefs. Once dessert mattered, so did the quality of the chocolate used for the increasingly complex plated desserts these chefs sought to produce. See plated desserts. Many pastry professionals turned to Valrhona, in part because of its French pedigree, but mainly because of its superior flavor and consistency.

The development of an artisanal food industry, including winemaking, bread baking, and cheese making, also fueled an interest in quality handmade chocolate, both bars and bonbons. See bonbon. The perception that chocolate was merely candy was changing. Chefs and consumers began to realize that chocolate could have different taste profiles depending on where the beans were grown and how they were handled after being harvested. While pastry chefs and chocolatiers in the United States did have other options for base chocolate, many deemed Valrhona the most desirable, and by the late 1980s and early 1990s, Valrhona could be found on the dessert menus of better restaurants throughout the United States.

Part of the company’s success may lie in the support services it provides to its professional customers: pastry chefs and chocolatiers are invited to attend classes at any of several École du Grand Chocolat locations as a way of becoming more familiar with the Valrhona product line, as well as more proficient at their craft. The schools are located in Tain l’Hermitage, Versailles, Tokyo, and Brooklyn, New York. Valrhona is also known for its innovation, especially in regard to white and milk chocolate, and new flavors are regularly launched in both the professional and nonprofessional sectors. Lesser known are Valrhona’s Vintage and Estate-Grown dark chocolate bars from Madagascar, Venezuela, Trinidad, and the Dominican Republic. These bars showcase terroir in chocolate and are fine examples of bean-to-bar single-origin bars. See chocolate, single origin.

Over the last decade, both consumers and producers have begun to consider issues of sustainability surrounding cacao. Fair Trade practices and the reality of child labor are of utmost concern. See child labor. As a company policy, Valrhona does not source beans from Ivory Coast, where bean quality tends to be poor and where a significant number of children are engaged in the cultivation and harvest of cacao.

See also cocoa and chocolate, post-columbian.

van Houten, Coenraad Johannes (1801–1887), developed a superior form of drinking chocolate by devising a process that removed substantial amounts of fatty cocoa butter from the cocoa mass, thus creating a more homogenized finished product. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in Europe, chocolate was used almost exclusively as a beverage. Chunks of unsweetened chocolate were dissolved in hot water or milk, sometimes with the addition of sugar. But the beverage was oily and heavy because of the cocoa bean’s high cocoa butter content; wooden sticks called moulinets were used to whip the drink into a froth, partly an attempt to disperse the fat evenly throughout the liquid. See chocolate pots and cups.

Coenraad van Houten’s father, Casparus (Senior), ran a chocolate business in Amsterdam, Holland, and developed a screw press that could separate cocoa powder from cocoa butter. See cocoa. He patented the process in 1828. The leftover cocoa butter could be added to ordinary ground cocoa beans to make the paste smoother and more tolerant of added sugar—a boon for modern candy making. Cocoa powder itself transformed “hot chocolate” into the drink we know today, rather than the oily brew of yesteryear.

Coenraad himself was an innovator. He improved on his father’s work by inventing a process called “dutching” (a.k.a. Dutch-process), which involves washing cocoa beans in an alkaline solution, usually potassium carbonate, to reduce their acidity. Dutching cocoa powder results in a darker color and milder flavor and improves its ability to dissolve in liquid. Although natural cocoa powder can be substituted for Dutch-process cocoa in most recipes (though not vice versa), it is best to follow specific recipe instructions to achieve the desired flavor and texture of the finished product.

vanilla, a flavor that in American usage has become synonymous with “ordinary” and “plain,” is actually exotic, intoxicating, and vastly underutilized. It shines on its own and enhances other flavors. Vanilla is equally useful in desserts, confections, beverages, entrees, and side dishes, and it stars in such beloved dishes as vanilla crème brûlée, vanilla milkshakes, chocolate chip cookies, and white and yellow cakes. It has medicinal value, adds aromatic notes to perfumes, and is a proven aphrodisiac. See aphrodisiacs; crème brûlée; and soda fountain.

A native of the Americas, Vanilla planifolia is the only edible fruit of the orchid family, the largest and oldest family of flowering plants in the world. Vanilla is indigenous to coastal Mexico, Central and South America, and the Caribbean. It is a tropical rainforest plant, both an epiphyte and root-producing vine. Its delicate yellow-white flowers bloom once a year, opening early in the morning, wilting by midday, and dying by mid-afternoon unless they are (rarely) pollinated by bees or hand-pollinated, a process known worldwide as “the marriage of vanilla.”

Vanilla is the world’s most labor-intensive agricultural crop. It cannot be grown commercially on massive plantations; most plantations are only a hectare or two in size. After pollination, vanilla beans remain on the vines for nine months and are picked individually. They require a four-to-six-week curing, drying, and conditioning process. They are then sorted and placed on racks to rest for at least a month before coming to market. Throughout this process, each bean is handled dozens of times.

To the early Mesoamericans, vanilla was second only to cacao in value and was treasured for its sacred properties. Its flowers were carried in amulets, as protection against the “evil eye,” and its perfumed beans adorned altars. Vanilla played a supporting role to cacao in xocolatl (chocolatl), the beverage of the elite, drunk by the Olmec and Maya long before Moctezuma served it to Cortés in 1519. See cocoa and chocolate, pre-columbian. The indigenous people of Mesoamerica used vanilla medicinally, as documented by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, who came to New Spain in 1529. Of vanilla he wrote, “It is perfumed, fragrant, precious, good, and a medicine.”

Cortés introduced cacao and vanilla to the Spanish court as a beverage. The Spaniards substituted cane sugar, cinnamon, and black pepper for the native wild honey, chili peppers, red clay, and ear flowers the Central Americans had used, and they served their chocolate hot. See chocolate, post-columbian and chocolate pots and cups. Until the beginning of the seventeenth century, vanilla in Europe was considered only a flavoring for chocolate, but this perception changed as vanilla’s popularity among the affluent quickly spread. Queen Elizabeth I adored sweets laden with sugar and flavored with vanilla. The elite of France and Italy couldn’t get enough of vanilla, whether as a flavor, a fragrance, a medicine, or an aphrodisiac.

Until the seventeenth century, the Spanish controlled the world’s supply of chocolate and vanilla, making a tidy profit. When the Dutch chartered the Dutch West India Company in 1621, they dramatically expanded the sugar trade to meet demand for sweetening chocolate, coffee, and tea. See sugar trade. Sephardic Jews who had fled the Inquisition traveled to Brazil and the Caribbean with the Dutch, working as sugar refiners and merchants, then expanding to the cacao and vanilla trade. They secured the monopoly over vanilla, sending the much-desired pods to their merchant friends and families in Europe.

Vanilla’s intoxicating flavor won over Thomas Jefferson during his time in France. Unable to find any pods upon his return to the United States, he requested that some be sent to him in Philadelphia. Soon Jefferson became known for his refined vanilla ice cream (a handwritten recipe is now in the Library of Congress). See ice cream. In the midst of the French Revolution vanilla actually traveled on sailing ships from Mexico to France, and then back to the United States.

As demand for vanilla continued to grow, plantations were established in tropical colonies around the world. The plant flourished but did not produce fruits, confounding both botanists and gentlemen farmers alike. The Totonacas in the Misantla Valley of southeastern Mexico are credited as being the first to domesticate vanilla. It appears that domestication actually occurred between the mid-1600s and mid-1700s, from as far south as coastal Guatemala north to the Misantla Valley. However, although each vine produced 30 to 40 beans annually—more than the 8 to 10 beans of wild vanilla—it was not enough to meet the rising demand for vanilla in both New Spain and Europe.

It wasn’t until twelve-year-old Edmund Albius, a slave boy in Réunion, hand-pollinated some vanilla orchids in 1851, that the code for producing vanilla in volume was broken. Orchids need pollinators. As the flowers survive only a day, natural pollination rarely occurs, even in its native habitat. This vital information secured the Indian Ocean’s place in vanilla production, first in Réunion, and later in Madagascar and the Comoro Islands. Vanilla finally became more accessible as a flavor and fragrance.

In the mid-1800s, French and Italian immigrants came to the Gulf Coast of Mexico, where some became vanilla producers. They developed more effective methods of curing and drying the beans, thus improving quality. In the early 1870s, three French immigrants went to France on business and learned about hand-pollination. Upon returning to Mexico, they charged for their welcomed information, and within two decades vanilla production grew to over 300 tons a year. The Mexican industry thrived until the early twentieth century, when the demand for oil and the Mexican Revolution triggered its decline. Madagascar soon surpassed Mexico in vanilla production, and Mexico never recovered. Vanilla is now grown in tropical regions worldwide, but Madagascar continues to lead the industry.

People in Europe have always used vanilla beans in cooking, but in the United States extracts are generally used. It is easy to adulterate pure extracts with imitation vanilla, or to substitute imitation vanilla and label it as pure—a serious problem in the first half of the twentieth century. See adulteration. In the 1960s the U.S. Food and Drug Administration established a Standard of Identity in an effort to guarantee pure vanilla in manufactured products. Nevertheless, the battle over the regulations continues, as the powerful Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association (FEMA) lobby represents traders who sell pure vanilla as well as manufacturers who produce both pure and imitation flavors. FEMA’s advocacy for both sides has made it difficult to enforce the label laws for pure vanilla, thereby undercutting its use.

Supply and demand control the cost of vanilla. When prices are low, pure vanilla is used; when vanilla is scarce, prices go up, the laws are ignored, and “natural flavors or “other natural flavors” (a euphemism for imitation vanilla) are substituted for pure, thus undercutting the farmers. Increasingly, vanilla farmers are switching to other crops in order to survive.

While pure vanilla may never completely disappear, the industry continues to decline. It is up to consumers to demand pure vanilla in purchased products, and to use it in cooking to keep pure vanilla a viable crop. Certainly the world would be considerably more plain and ordinary without it.

See dumplings.

vegetables and herbs, the leaves, stems, roots, and nonsweet fruits of any edible plant, can be sweetened to deliver what our ancestors valued as happiness—the taste of the sun and the promise of ripeness. Candidates most suited to this transformation from everyday foodstuff to pleasure giver are those vegetables and herbs whose stems or fruits or leaves are sufficiently fleshy and bland to allow them to absorb and retain the effect of applying sweetness in whatever form is most appropriate.

Among plant foods of Eurasian or African origin, the fruits of nonsweet melons and gourds, aubergines (eggplants), and the fleshy stems of chard, lovage, celery, artichoke, angelica, fennel, and celery are traditionally sugared, candied, or preserved in syrup. See candied fruit and fruit preserves. Among roots and tubers similarly available for sugar-treatment are ginger, dandelion, parsnip, turnip, carrot, yam, and eryngo, while seaweed is also eaten sugared in Eastern traditions. Herbs and seeds traditionally sugared or candied (rather than used for flavoring) are usually those with digestive properties, such as mint, cumin, and aniseed. See comfit and confetti.

Plant foods of New World descent suitable for sugaring—a treatment unavailable until after the Columbian exchange—include sweet cassava, both savory and sweet potatoes, tomatoes, cactus paddles, and all of the squashes, particularly pumpkin and marrow. Ingredients and recipes traveled in both directions. Jean Anderson, in The Food of Portugal, describes doce de chila or gila, a sweet preserve made from Cucurbita ficifolia, “a gourd with strings like spaghetti-squash,” as a popular stuffing in Portuguese egg sweets, including a version of the ever-popular caramel custard, toucinho do céo, to replace the more labor-intensive fios de ovos, egg-yolk threads trickled into hot sugar-syrup. See egg yolk sweets and portugal.

The process by which any foodstuff, including bitter medicinal herbs, can be made more palatable through sweetening was simple and primitive when honey or cane syrup served as the transforming agent; it has become complicated and open to commercialization with the arrival of cheap, manufactured beet sugar, corn syrup, and the like. Stems and leaves have little if any natural sweetness, though their roots can sometimes be providers, making them an excellent vehicle for the juice of sugarcane, a giant grass native to the delta of the Ganges that traveled east to China and west through Persia and the Middle East. A taste for sugar eventually spread into Europe through the Arab ascendancy at both ends of the Mediterranean. See sugarcane. In The Legendary Cuisine of Persia, the food historian Margaret Shaida provides a recipe for carrot jam cooked with its own weight of sugar flavored with orange zest, rosewater, and cardamom, and another for cucumber jam similarly prepared. In her book Sherbet & Spice, the Turkish food writer Mary Işın underlines the high regard for sweet foods in Islamic culture and provides instructions for making an aubergine preserve that has been popular throughout the Ottoman Empire since the sixteenth century.

The virtues of sugared vegetables, particularly those with established medicinal properties, are well recognized in literature. In sixteenth-century France, says historian Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat, Nostrodamus suggested that candied eryngoes, the roots of sea holly prepared in imitation of ginger root, “have all the virtues, goodness and qualities of green ginger.” See nostradamus. French confectioners who had learned their skills from the extravagant courts of Italy prepared “candied ribs of lettuce leaves in syrup like angelica,” calling them angels’ lips (bouches d’ange) to encourage licentious behavior in ladies of the aristocracy. Similar preserves prepared with celery, considered an aphrodisiac, could be considered appropriate for gentlemen. Identical hopes are expressed when Shakespeare has his comic character Falstaff, in The Merry Wives of Windsor, mention eryngo root (presumably candied) as an aphrodisiac: “Let it hail … kissing confits, and snow eringoes.” See aphrodisiacs.

Meanwhile, traditional recipes that make use of the natural sweetness in roots and tubers continued in parallel with sugar-based confections, particularly in northern lands. Even after they had fallen out of favor, they reappeared at times of shortage, as in poverty or wartime, when trade routes were cut. Parsnip and carrot have long been the poor man’s sweetener in cakes, puddings, and dumplings, and they continue to feature in contemporary recipes for festival foods, such as the English Christmas pudding. The tradition for home-grown sweetness in celebration foods is maintained in the pumpkin pie (with or without maple syrup) of America’s Thanksgiving dinner, while sweet potato pie is eaten by African Americans as a reminder of their African heritage at the more recently established winter festival of Kwanzaa.

In everyday eating, cheap sugar has transformed what was an occasional treat into a daily necessity. Relishes, chutneys, sweet pickles, and ketchups—sole survivors of that ancient tribe of vegetable pleasure-givers—add interest to fast food, whose taste would otherwise be bland.

See also cane syrup; corn syrup; honey; and sugar beet.

Venice, Italy, “the Floating City,” is a UNESCO World Heritage Site whose birth in the sea, dominion over it, and genius for commerce spawned a great trading empire, the world’s largest in its day. Over the centuries, the city created merchant princes and provided the Republic of Venice with inestimable wealth. One chronicler, writing in 1267, described the scene in the metropolis: “Merchandise flows through this noble city like water through fountains.”

Evidence of that mercantile history can still be seen along her thoroughfares: Calle dello Zucchero, Corte della Raffineria, and the Ruga dei Speziali. All are place names typical of Venice, yet they are rarely mentioned in guidebooks. But stumble on Sugar Street, the Court of the Refinery, or the Street of the Spice Merchants, and you are encountering the city’s Golden Age. These, and other related names, come largely from a time when, as a result of her vast power in the marketplace and seafaring might, Venice was dubbed Queen of the Adriatic and sugar was central to her livelihood. Here it was sold wholesale, here retail; here it was refined, here made into sweets, here purveyed as medicine. Picture ships in the harbors listing under sugar’s weight, the large warehouses heaped with it along the Zattere (begun as a loading dock in 1519), the merchants bidding for it in Rialto, once the city’s chief marketplace. Travelers commented on sugar’s presence in much the same way that Marco Polo, one of Venice’s most famous citizens, commented on the enormous quantities of sugar he saw in Hangzhou, China, during his travels.

Although il sale dolce, or “sweet salt,” as sugar was once called, had already made an appearance in Venice by the time the Crusades began in 1095, its fame grew after Crusaders found it under cultivation in the East and spread the word. They referred to sugar as a “spice,” a category in which it remained for centuries. Thus, when Venice was the spice capital of Europe and the eastern Mediterranean, sugar was included among her wares, along with cardamom, mace, pepper, cloves, nutmeg, turmeric, ginger, and cinnamon. See spices.

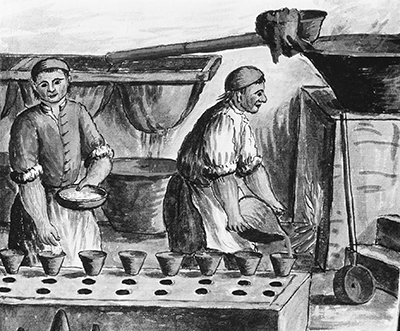

Sugar, once called “sweet salt,” was central to Venice’s fortunes, and Venetians acquired great skill in refining it. This pen, ink, and watercolor drawing by Jan van Grevenbroeck (1731–1807) shows workers at a Venetian sugar refinery. museo correr, venice, italy / roger-viollet, paris / bridgeman images

Long a producer and seller of salt, and an important trading center from the eighth century, with burgeoning connections around the Mediterranean, the Republic of Venice had moved naturally and determinedly into dealing in spices. Of these, sugar had begun to enter the Republic around 1000 c.e. By 1150, Venice is said to have been the chief port for it in the world, and from her domains sugar was distributed broadly. Sources for it changed and overlapped through the centuries. Egypt, the Levant, and Asia Minor were primary. Then, with the Fourth Crusade and the sacking of Constantinople in 1204, more avenues opened.

Sugar also came from the Stato da Mar, Venice’s “State of the Sea,” her maritime and overseas colonial possessions. One was Tyre in present-day Lebanon, where a number of Venetians had traded sugar and cultivated it on land grants, but there were also the islands of Crete (then known as Candia) and Cyprus. Our primary associations with sugar and slavery are in the Caribbean. But an early link between the two was forged earlier, largely (though not only) in colonial Venice, and particularly in those very islands. Indeed, Cyprus and Crete are often cited as the model for what was to come. There the Republic and her entrepreneurial citizens created plantation agriculture and processing facilities run at least in part by slave labor. See plantations, sugar; slavery; and sugarcane agriculture. When war and plague decimated the local agricultural workers, slaves from Arabia and Syria, sometimes prisoners of war from Greece, Bulgaria, and Turkey, were brought in to do the work alongside serfs or other members of the native population. The price of sugar was set at Rialto, the city’s chief marketplace, but the considerable human cost was not part of the calculation.

As sugar increased in importance, the estates devoted to it increased in size. Of particular note was that of the great Venetian Cornaro family on Cyprus. In 1494, Canon Pietro Casola, a pilgrim who stopped in Venice on his way to Jerusalem, wrote of his visit there, “I can only speak of a great farm … which belongs to a certain Don Federico Cornaro, a patrician of Venice … where they make so much sugar, that, in my judgment, it should suffice for all the world.”

At first, refined sugar was transported to Venice from the point of origin. But, eventually, toward the end of the 1400s, unrefined sugar began to be imported, and processing and manufacture were undertaken in the city and her possessions. Over time, Venetians perfected the refining process, producing a higher-quality product that was whiter as well as purer. As a result of their success, in the sixteenth century the republic published the first manuals on how to refine sugar and make sweets.

Of course, Venice herself used the sugar that was manufactured and bought and sold there. Treasured by the patricians of the city (the only ones who could afford it), sugar was an ingredient in their cuisine, a flavor enhancer, and a condiment. In the Renaissance the separation between sweet and savory did not yet exist. Therefore, sugar was used in cooking many dishes with which we would not associate it today, such as eggs, pasta, meat, and fish. A few of these recipes still remain, like Veneto’s famous sarde in saor, a dish of sardines in a sweet and sour sauce made with vinegar, onions, and raisins or sugar that could delight a Renaissance appetite, and probably did.

However, things are different where the sweet course or desserts are concerned. Dishes keep being invented—one of the most famous, tiramisù, believed to have been devised in the 1960s, is thought to come from Treviso, Veneto, the region of which Venice is the chief city. See tiramisù. But the origin of other sweets, especially certain typically Venetian biscuits or cookies, goes back centuries. Favette, little fried dough balls sometimes flavored with anise liquor, have sugar sprinkled on top and are among the typical sweets prepared for Venice’s celebrated Carnival. See carnival and fried dough. They appear in a plain version in 100 Ricette di Cucina Veneziana, published in 1908, considered the first cookbook specifically dedicated to Venetian cuisine. (A fourteenth-century manuscript, Anonimo Veneziano, is often cited as the first, but its recipes are not exclusively, or even primarily, Venetian.) Fritole, fried balls of yeast-raised dough, often mixed with pine nuts, are also one of the beloved sweets most associated with Carnival in La Serenissma. Once made on the spot by fritoleri, whose carts were stationed throughout the city, they are now found in pastry shops. Baicoli, a simple, but beloved, oval-shaped biscuit that goes back centuries, takes its name from a resemblance to tiny branzino (baicoli in Venetian), a common fish of the lagoon. Baicoli are often served with the light custard zabaglione. See zabaglione. Azzime dolci (sweet matzah) are biscuits sometimes enriched with fennel seeds or aniseed, mentioned by the famous Venetian rabbi, Leone di Modena, in a work published in 1637, where he recommends the addition of sugar for the weak or unwell. Zaeti are very sweet, yellowish biscuits made with polenta flour that date from the sixteenth century and frequently include raisins soaked in grappa or water. Such biscuits or cookies were often dunked in sweetened hot chocolate or coffee.

Culinary applications were not sugar’s only attraction. Equally important to its popularity in the era of humoral medicine were its medicinal uses. Spices were considered salutary and were prescribed for a variety of conditions; pharmacopeias of the day identified the properties of each. See medicinal uses of sugar and pharmacology. Sugar, almost a miracle drug, was often recommended for the healing of wounds, to relieve childbirth pains, to cure ulcers and respiratory ailments, to relieve the pain of headaches, to cleanse the blood, and as a tonic for general health. Sugar was even sometimes used in an attempt to combat the plague.

Spices revolutionized the practice of medicine because they greatly increased products available for treating health problems. That also made them the province of apothecaries, often called spezieri (spice sellers). At first, spice sellers and “pharmacists” overlapped, but in the middle of the 1300s, two separate groups, both of which dealt with sugar, were established. The spezieri da medicina sold spices, syrups, electuaries, and tonics, and became so expert in this art that they were renowned throughout Italy and beyond for their skills. (Lo Speziale [The Apothecary], an opera by Joseph Haydn with a libretto by the eighteenth-century Venetian playwright Carlo Goldoni, turns on making the title character believe that the sultan of Turkey has summoned him for his skills.) The second group, the spezieri da grosso, sold spices and sugar, but not for therapeutic use. They were also the purveyors of candles, soap, cosmetics, ink, paper, marzipan, confetti (sugared spices), sweetmeats, almonds and other nuts, dried fruits, and more. See confetti; dried fruit; marzipan; and nuts. Nor were they simply retailers. They fabricated many of their products and were involved in import and export and the wholesale trade. Thus, it was the spezieri da grosso who became the most heavily involved with the sugar refineries in the city, as well as with the business of sugar in general.

Sugar had one last major use, the building of sugar sculptures, pieces known as trionfi di zucchero, trionfi di tavola, or, in Venice, spongade. See sugar sculpture. Famous for her love of spectacle and hospitality to visitors, Venice was highly skilled in this art. In 1493, Beatrice d’Este, on a state visit representing her husband, Ludovico del Moro, the duke of Milan, wrote to him of a banquet in the Ducal Palace in which the different dishes and confetti were carried in to the sound of trumpets, and of “sugar figures of the Pope, the Doge, and the Duke of Milan, with their armorial bearings and those of your Highness; then St. Mark plus many other objects.” They were, she continued, of “colored and gilded sugar, making as many as three hundred in all, together with every variety of cakes and confectionery.” However, the most famous such occasion was a collation in 1574 when King Henry III, the new ruler of France, passed through Venice. Designs by the great architect and sculptor Jacopo Sansovino were executed by the apothecary Niccolo Cavallieri. In addition to every kind of statuette, bread, plates, knives, forks, tablecloth, furniture, fruit, flowers, and trees were all said to be so lifelike that it was only when a napkin broke in his hand that the astonished king realized that the settings were an illusion, there to dazzle him with works in sweet salt that spoke to Venice’s great power.

See also italy; sugar refining; and sugar trade.

verrine is a term coined by the Paris patissier Philippe Conticini in 1994, when he began stylishly layering ingredients with contrasting or complementary flavors, textures, and colors in small, clear glasses. It is derived from the French word verre (glass). Heading up the kitchen at Petrossian in Paris a few years later, Conticini served individual courses throughout entire meals the same way, with long-handled flatware with which to savor each bite. “What creates synergy in a dish,” he explained in the New York Times in 2001, “is not just the combination of flavors, but how they are combined. And often with a dessert, a plate simply won’t do. Because it’s flat, it does not allow the components to mingle as they are eaten. I played around with different dishes and bowls and finally decided on a glass … the flavors are like neighbors in a small community. They bump into one another, they interact and they are concentrated.”

With their element of surprise, stunning visual appeal, and make-ahead assembly, verrines have since sparked the imagination of other patissiers, who showcase them in chic shops from Paris to New York City and Tokyo. In France, sweet and savory verrines are served at bistros and cafés, as well as at Michelin-starred restaurants. Their presence in that country’s supermarket frozen-food cases is arguably evidence of the inevitable slide from culinary trend to cliché.

The verrine has been slow to catch on in the United States. For Americans, it is perhaps less an artful concept than a very modern, delicate, clean-tasting parfait—and, more important, a reminder of flavors that go together. Even a simple combination, such as the components of a Greek salad layered in a jam jar (à la Gourmet magazine, August 2008), can transform lunch into un pique-nique.

See also plated desserts.

Vienna, the capital of Austria, was the residence of the Habsburg monarchs for several centuries and the center of an empire that around 1900 had more than 50 million inhabitants. See austria-hungary. The various nationalities in this multinational empire, among them Austrians, Slavs, Italians, and Hungarians, all contributed to what are today known as Viennese cuisine and Viennese sweets. While Vienna is nowadays widely known as the capital of cakes, confections, ice cream, and coffeehouses, it took quite some time for the city to establish this reputation.

Until the sixteenth century, sugar was very expensive. Honey was the main sweetening agent used, and gingerbread and mead were widely appreciated. See gingerbread; honey; and mead. By the thirteenth century, Vienna had become a center of fine pastry. Subsequent centuries saw the development of various other trades dealing in sweet pastry, including bakers of flat wafers (Oblaten) and hollow wafers (Hohlhippen), as well as fritters (Krapfen). See fritter and wafers.

Initially, only apothecaries—also called confectionarii—had the right to make and sell sugar. It was traded either in a pure form, as a medicine, or in the form of candied fruit, herbs, blossoms, spices, or roots, which were considered to be “healthy” food. See candied fruit and spices. Many products of this sort came to Vienna via Italy. Duke Albert III (1349–1395) decided that only apothecaries were allowed to produce and sell candied items; all imports from Venice were forbidden. See venice. Only around the middle of the sixteenth century did the apothecaries lose their monopoly in producing and selling sugar and candied products. Others were now allowed to call themselves Zuckermacher (producers of sugar) or Zuckerbacher (producers of candied fruit, stewed fruit, jams, etc.). It is assumed that the German term bacher, as in Zuckerbacher, has nothing to do with baking. The word seems to come from zusammenpacken—packing things together like sugar and fruit, nuts, and herbs. Zuckerbäcker did not bake anything for a long time. In any case, sixteenth-century guild regulations forbade confectioners from using ordinary flour for their work—they were allowed to use only expensive rice flour—and compliance with this rule was closely monitored by the urban bakers. See guilds.

It is said that Emperor Ferdinand I (1503–1564) brought confectioners from the Netherlands to Vienna. The earliest document mentioning a court confectioner in Vienna dates from the year 1566, when Matthias de Vos(s), from the Netherlands, was employed at court. From that time onward, confectioners worked at the Habsburg court, until the collapse of the empire in 1918.

The new trade, with its tempting products, did not remain restricted to the court. Soon independent confectioners opened their own shops in Vienna—Hanns Eysengrein, Georg Thurner, and Georg Diersch were the first, around 1568. Diersch’s daughter Catharina also became a confectioner in Vienna. But the number of independent confectioners grew slowly, because the raw materials for their work were very expensive, and the number of wealthy people who could afford their costly products was limited. Confectioners were allowed to use a narrow range of raw materials: rice flour, almonds, pine nuts, sweet chestnuts, raisins, pistachios, and fruit. They produced sugar bars, delicate breads made from ground almonds and pistachios, sugar-bretzels, marchpane (marzipan), candied fruit, jams, almond milk, ice cream, and lemonades.

The Vienna Guild of Confectioners was founded in 1744. Eighteen confectioners were accepted as members; each was allowed to employ a single apprentice. The confectioners were entitled to sell their products either within the city walls or outside the city. At that time the city center (today Vienna’s first district) was still walled in. The city walls were separated from the suburbs by a large green area where the Viennese frequently took their Sunday walks. Afterward they would enjoy some delicacies at a confectioner’s shop. But the range of confectionery products was still limited: biscuits, zwieback, almond and sugar pastry, white and colored sweetmeats, marzipan, candied fruit, fruit preserved in sugar, ice cream, fresh jellies, and all kinds of refreshments were offered to the public by the city’s independent confectioners.

Confectioners’ Shops and Coffeehouses in Vienna

Confectioners’ shops—Konditoreien in German—were not technically cafés. See café. Coffeehouses had sprung up in Vienna in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The Viennese appreciated the new drink and the parlors that offered it, where men could smoke and read newspapers. Only the owners of coffeehouses were allowed to sell coffee, and they sold little that could be characterized as dessert. In turn, confectioners were not allowed to sell coffee, a regulation that changed only at the turn of the twentieth century, when confectioners were allowed for the first time to sell savory products like sandwiches, salads, ham rolls, toasts, and Prague eggs (hard-boiled eggs filled with a mixture of yolk and mayonnaise and decorated with fish, ham, etc.). Originally, confectioners’ shops were mainly visited by ladies—but ladies were mostly accompanied by gentlemen, and therefore, around 1900, the confectioners’ guild thought that the shops should also offer something more substantial.

In addition to being served at small confectionery shops, delicacies were offered in lemonade huts and refreshment tents, which were especially set up for the summer. The eighteenth century brought an ice-cream boom to Vienna; the most fashionable confectioners in the second half of the eighteenth century were Milano and Taroni in the elegant Graben (today a fashionable shopping street linking Kohlmarkt and St. Stephen’s Square)—another indication of Italy’s important influence on the production of sweets, candy, and ice cream. See ice cream and italy.

In the eighteenth century, too, Vienna’s sweet makers began to expand their repertoire. An advertisement by the city confectioner Ulrich Schmidt in Wiener Zeitung from 1748 shows that confectioners had finally won the fight against restrictions to their production. Schmidt was evidently now able to use wheat flour, and his shop offered butter pies and various types of cake, including bread cake, butter cake, Linzer Torte, almond cake, biscuit and French cake. See linzer torte. Around 1800, Konrad Höfelmeyer ran an elegant confectioner’s shop at Tuchlauben, where he sold jams and cakes alongside edible table centerpieces such as tragacanth figures. See sugar sculpture and tragacanth. Ludwig Dehne from Württemberg established a fashionable ice-cream parlor on Michaelerplatz, opposite the Imperial palace, around 1785. Under the direction of Dehne’s widow, the shop later became famous for its crèmes, pink vanilla jelly, cakes, sugarcoated pills and fruit, sweets, candy, sorbets, liqueurs, and ice cream. In 1857, Dehne’s was taken over by Christoph Demel, the chief confectioner of Dehne. Demel successfully continued what Dehne had begun.

Sweets for a Broader Public

Once domestic sugar refined from beets came onto the Austrian market in the mid-nineteenth century, sweets became less expensive and more accessible to a broader public. Thus, more confectioners were able to set up their own businesses. Among them were Ludwig Heiner, who opened his shop on Wollzeile in 1840; Louis Lehmann, whose establishment on Singerstrasse was well known for stewed and sugar-coated fruit (Lehmann’s shop moved to Graben after 1945 and closed in 2008); Anton Gerstner, whose shop at Stock-im-Eisen (now Kärntner Strasse) opened in 1847 and became famous for ice cream and Christmas decorations; and Joseph Sluka in Rathausstrasse. All of these confectioners—including Demel—became purveyors to the imperial and royal court. The list of their sweet inventions was almost endless: strudels, cakes, biscuit-rolls filled with jam, doughnuts, sweet slices, Marmorkuchen (a cake made to look like marble by combining dark and light batters), and many others. See doughnuts and strudel.

For a long time chocolate was little used by confectioners. It was very hard and crumbled easily. Chocolate was primarily made into a hot drink, although in Austria it might be ground and added to cake batters. It was only after Swiss innovations in the mid-nineteenth century that chocolate could easily be melted and added to batters and made into chocolate icing. The popularity of Joseph Dobos’s eponymous torte in the 1890s led to a wide assortment of chocolate-based cakes, such as Esterházy Torte, Alpenmilchtorte, and Panamatorte, to name just a few. See dobos torte.

Ice cream was made not only by Viennese confectioners. From the second half of the nineteenth century, a number of Italian families came to Vienna to open ice-cream parlors. They stayed during the warm months and returned to Italy in winter. Many of these families still have their shops in Vienna and sell their ice cream from April to October.

In the twentieth century an ever-larger number of people could afford confectionery products. Josef Prousek had come to Vienna in 1896 from Gablonz (today in the Czech Republic). He worked as a confectioner, and in 1913 he took over a confectioner’s shop and chocolate manufactory in Vienna’s second district. Prousek was able to expand his business quickly, adding a large number of shops to his network all over Vienna. Today his chain of confectionery shops, now run under the name Aida, offers a wide range of cakes, sweet snacks, bonbons, and savory snacks.

See also bonbon; cake; fruit preserves; lemonade; marzipan; nuts; and torte.

vinarterta is a strictly Icelandic cake, even though its name means “Viennese cake” and its origins are most likely Viennese by way of Denmark. Traditionally served with coffee at weddings and Christmas since around 1860, the festive, rectangular delicacy comprised five to nine layers of fruit jam and shortbread pastry, although contemporary versions incorporate baking powder–leavened bread in order to achieve a lighter consistency. It is frequently iced with a simple sugar glaze that can be laced with vodka or bourbon. The dough is often flavored with almonds, and the fruit filling spiked with cardamom, vanilla, or red wine. In the late nineteenth century, prunes, once a luxury item in Iceland, were gradually replaced in many households by less expensive fruits, such as the rhubarb that proliferates in the countryside. Because vinarterta has a long shelf life, it can last for several months when well wrapped.

Vinarterta’s many layers have led to its nickname of randalín, which means “striped lady.” The torte is perhaps more beloved today by Iceland’s expatriate community, particularly in Canada, than in its own country. This fact is not surprising if one considers that vinarterta was at the height of its popularity when the Icelandic fishing industry collapsed in the late 1800s, and ash-fall from the explosion of the volcano Askja in eastern Iceland in 1875 poisoned much of the nation’s vegetation and livestock. As a result of these natural disasters, nearly 25 percent of Iceland’s population relocated to find work abroad. They took with them their beloved vinarterta recipe, and the dessert soon became (and remains to this day) a powerful symbol of national identity for Iceland’s displaced people, even as their use of the Icelandic language declined and they anglicized their names.

The Vipeholm experiment sought to determine the role of carbohydrates in dental cavity formation through a series of tests carried out in a Swedish mental institution in the 1940s. In the 1930s, dental health in Sweden was exceptionally poor, with 99.9 percent of the population suffering from cavities. Thus, in 1938, the Swedish Parliament passed a costly resolution to provide all citizens with dental care (the Public Dental Service). The National Medical Board was asked to conduct a preventative clinical study at Vipeholm, an institution for the mentally disabled in Lund whose isolation would allow for the kind of controlled conditions the experiment required.

The investigation began in 1945 as a vitamin study but was refocused in 1947 to examine the correlation between dental caries and the consumption of carbohydrates. See dental caries. The patients in the test sample were forced to consume unnatural quantities of carbohydrates. For two years they were served sugar in the form of liquids, as bread at meals or between meals, and in as many as 24 sticky toffees a day. The outcomes revealed high levels of lactobacilli in the patients, and their consumption of sticky carbohydrate-dense products between meals led to high rates of caries activity. The publication of the results in 1953, and the controversy it engendered, caused the Swedish government to refuse all subsequent grants to the institution that conducted the Vipeholm study. Nonetheless, the findings prompted the replacement of sugar with sugar substitutes in commercial products such as chewing gum that were frequently consumed between meals.

Saturday Candy

The results also prompted the Swedish government to introduce “Saturday candy,” which remains a Swedish custom. National marketing campaigns encouraged parents to allow children to consume candy once a week, rather than spreading their consumption out over several days. As a result, Swedes eat 17.9 kilograms of candy per capita each year, an amount second only to the Danes. The Swedes’ excessive sweet tooth for candy is particularly noticeable among the younger generation: the average teenager today consumes candy three to five times a week, and among the general population candy constitutes an estimated quarter of the average weekend energy intake. In light of these statistics, and with the intention to improve overall population health, the Swedish government is considering reinforcing the Saturday candy tradition to prevent the current harmful consumption of candy several times a week. Critics are skeptical of this approach and find the pervasive “eat as much as you like, once a week” mantra harmful to public health. Instead, they suggest a 10 kronor ceiling on the amount of candy that can be consumed once a week, a constraint that would place Sweden at the average candy consumption level of the European Union—7.5 kilograms per capita per year.

vision, or visual cues—especially color—influence how we perceive what we eat. Even before our first bite, we anticipate what we will taste based upon how the food looks, and this anticipation can influence how we then experience the flavor. Darker-colored chocolate is perceived to have a more intense chocolate flavor than lighter-colored chocolate, and orange-colored chocolates can seem to have an orange flavor—but only if the person eating it thinks that the orange ones should taste orange. A green macaron might be pistachio, lime, or green tea-flavored, depending on the shade, but it is probably not infused with salted caramel or vanilla. In this case, the color creates an expectation about the flavor of the macaron. When the actual flavor is similar to the expectation, assimilation often occurs; people taste what they expect to taste, and an orange-flavored macaron that is colored green could easily be perceived as lime by many people. But when there is a larger discrepancy, such as with a green-colored but coffee-flavored macaron, contrast occurs and the mismatch is more often detected, to the delight or dismay of the consumer.

At least some color-flavor associations are learned over time. They can vary across cultures as well as within a culture. As different cultures consume different sweets (pumpkin, blackcurrant, and red bean all can be used in sweets but are popular in different regions), the expectation elicited by a particular color will depend hugely on context. The color of a gummi bear can indicate its flavor, but whether green means apple, lime, or strawberry depends on both the manufacturer and country of purchase. As with the macaron, the color creates an expectation about the specific identity of the flavor of the gummi bear. Some expectations about intensity, however, might exist without the need for experience. In the case of dark chocolate, the richer color creates an expectation that the chocolate will be more intense, and it may be that the brain naturally expects flavors that look more intense to taste more intense. But even these sorts of associations can change as a result of experience; adding red food coloring tends to lead to foods tasting sweeter, but adding green can actually reduce the perceived sweetness. Some scientists have speculated that this particular association has to do with fruit becoming both redder and sweeter as it ripens. Fans of red velvet cake might think about how much the red color might be enhancing their flavor experience. Moreover, even the color of the plate on which a dessert is served can matter; people eating strawberry mousse on a white plate perceived the mousse as more intense and sweeter, and liked it more, than when it was served on a black plate. Food manufacturers are aware of these effects, and many have experimented with adjusting the color of both actual food items and food packaging.

While the role of color has been explored for many years, other cues may be important as well. Glossiness can provide information about oiliness or wetness, and can potentially influence expectations about flavor. Recent studies have shown that shape can also influence taste. For instance, people are better at detecting low levels of sugar in water when looking at curved shapes than when looking at sharp-edged shapes. This could be because the curved shapes evoke pleasantness, which is in turn associated with sweetness. However, at least for sweets, the mapping between shape and identity may be less consistent than that between color and identity. Various chocolatiers make heart-shaped chocolates with raspberry, praline, or even chili and cinnamon ganache. While shape can influence the eating experience directly by changing the rate at which chocolate melts in the mouth, shape also likely influences perception by providing visual information that sets expectations, and perhaps even by eliciting particular flavor memories. In the United Kingdom, after Cadbury changed their Dairy Milk bar to a more curved shape, some consumers believed that the taste had changed as well, though the recipe remained the same. See shape.

Further evidence for the role of vision comes from restaurants in which people “dine in the dark.” At these restaurants, which now exist in cities around the world, blind waiters serve patrons an entire meal in complete darkness. The restaurants vary in how much information patrons are given about what they will eat; some keep the entire menu a surprise, whereas others allow particular dishes to be selected. When people do not know what to expect and lack visual information, they often are unable to identify what they are eating. Although people in other settings may sometimes close their eyes to enhance the perceptual sensitivity of their other senses, there is no evidence that removing visual cues entirely sharpens flavor sensitivity. Much of the appeal of these restaurants may be due to the novelty of the experience rather than to actual heightened taste experiences.

Some chefs use visual cues in a playful way, to create dishes in which visual expectations add drama to the dining experience. Heston Blumenthal has created a dessert that looks like a traditional British Christmas fruitcake but tastes like a chocolate brownie. Ferran Adrià has developed an “apple caviar” dish that has the appearance of caviar but tastes sweet rather than savory. At Manresa, near San Francisco, a meal starts with a brown-colored olive madeleine and a red bell pepper jelly, and ends with a chocolate madeleine and a strawberry jelly colored so that they look identical to the starter. The scientific evidence shows that visual presentation matters, so the next time you serve sweets, remember that your eyes can also feast upon a delicious dessert.

See also food colorings and neuroscience.