sablé is a French butter cookie in the shortbread family that may have originated in Normandy. The cookie or biscuit is usually sweet and may be sandwiched in pairs with a filling. Normandy lies on the northwest coast of France, where the Atlantic provides a mild, even climate with ample rainfall, leading to a long tradition of dairy farming. High-quality butter is a key ingredient of the sablé, along with flour, egg yolks, and sugar. A little salt and vanilla, or perhaps lemon, almond, or chocolate, are the only other flavorings. For a savory sablé, grainy Parmesan or similar hard cheese is grated and mixed into the dough.

The name “sablé” derives from the French word for sand, sable, referring to the cookie’s tender, crumbly texture; it likely derives from pastry that used to be known as pâte sablée. Describing this pastry in La Bonne cuisine française (ca. 1890), Émile Dumont notes, “Pâte sablée is called this because as one eats, it breaks into little particles like grains of sand.” To produce the desirable texture, cooks and pastry chefs have various techniques for achieving that graininess, such as using large-crystal “sand” sugar, adding the sugar or flour in two separate stages, using part confectioner’s sugar and part granulated sugar, chilling the dough before cutting it, and so forth.

Besides giving the sablé a rich flavor, a high butter content with minimal handling inhibits the formation of gluten strands in the flour, which would make the dough tough or elastic. The butterfat shortens the dough by breaking up the gluten, hence the terms “shortbread” and “shortening.” “Simple as this dough is to prepare,” writes Madame E. Saint-Ange in La Bonne Cuisine (1927), “it nonetheless has one essential requirement: that it be worked rapidly with a rather cool hand. If the work takes a long time, the dough loses its sandy character; and there is quite a lot of butter, so if your hand is warm it will melt as you work and mix badly with the flour.”

See also shortbread.

saccharimeter is a scientific instrument used for sugar analysis that evolved from the simpler polariscope used by the French savant Jean-Baptiste Biot (1774–1862). From his experiments in light reflection in the second decade of the nineteenth century, Biot found that when he passed polarized light through some substances, the plane of polarization would rotate. He also found that cane sugar and beet sugar act the same in this regard, while other substances do not. Thus, a polariscope would enable him to distinguish sucrose from other sugars (such as glucose) that rotate the plane of polarization in the opposite direction. When Biot found that the strength of the sugar solution determines the extent of optical rotation, he realized that a polarimeter (a polariscope that measures this rotation) could be used to determine the quality of sugar for commercial or tax purposes. In the 1840s a French optical instrument maker named Jean-Baptiste François Soleil designed a polarimeter specifically for sugar analysis and termed it a saccharimeter. As subsequent improvements made saccharimeters more reliable and user friendly, these optical instruments came into widespread use in countries around the world.

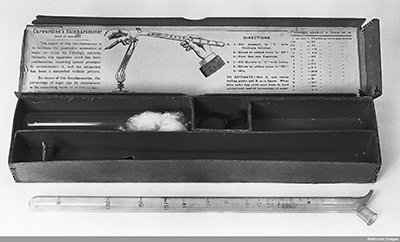

The Carwardine Saccharometer was invented around 1894 by Thomas Carwardine, a physician at Middlesex Hospital in London. Saccharometers and saccharimeters both test for the presence of sugar in urine, an indicator of diabetes, but saccharometers measure the specific gravity of a solution, while the more modern saccharimeter measures its light polarization. wellcome library, london

Saccharimeters are still used today for sugar analysis. They are also used to determine the sugar content of wines and other vegetable products. And they are used by doctors who diagnose diabetes by determining the sugar content of urine.

Sachertorte, Vienna’s famous chocolate cake, is easily that city’s most storied confection. The cake is almost the personification of the sweet—and perhaps somewhat staid—elegance that still hovers over the old Habsburg metropolis. As described by the authors of the comprehensive Appetit-Lexicon (1894), the pastry is “a superior sort of chocolate cake, distinguished from her rivals primarily by the chocolate gown she wears over her blouse of apricot jam.” Poetic hyperbole aside, the definition of what can legally be called a Sachertorte in Austria is very specific. The Österreichisches Lebensmittelbuch (the Austrian food codex) devotes six pages to a precise definition of cakes and related confectionery, starting with the celebrated Sacher. To summarize, the cake itself needs to be a chocolate sponge (minimum 15 percent chocolate solids); nuts can be added, as long as the name reflects the addition. The cake must then be covered with apricot preserves, and finally with a fudgy glaze containing chocolate and sugar. Forgeries that contain such verboten additions as buttercream, ganache, or raspberry jam may be perfectly delicious, but they are not a Sacher.

The original is named after Franz Sacher, a caterer who worked in Vienna and nearby Bratislava (then Pressburg) in the middle years of the nineteenth century. According to a story recounted by his son Eduard, the elder Sacher began his career as an apprentice in the kitchens of Prince Metternich, then the most powerful politician in the Habsburg Empire. One day in 1832 the 15-year-old Franz was apparently asked to make dinner for the great statesman and three of his friends. It was supposedly for this intimate fete that the culinary prodigy whipped up that first Sachertorte. The story is a good one, and it has been repeated so often that it has the ring of truth (not least by Eduard Sacher, who used it to good effect to promote his five-star hotel). The trouble is that Franz Sacher himself told a different tale. In a 1906 interview for the Neues Wiener Tagblatt, the 90-year old recalled first making the cake in the 1840s when he ran a restaurant and catering business in Bratislava. There is a certain logic to this. The cake is custom built to hold up to the stresses of catering. It need not be refrigerated, and the apricot glaze keeps it from drying out—the main reasons that the Hotel Sacher has been able to maintain a flourishing mail order business in the confection ever since the 1900s. Since there are no documents confirming either story, the question arises of which to trust: the memory of the nonagenarian inventor or the promotional efforts of his hotelier son?

If there is controversy regarding the cake’s birth date or place, it is nothing compared to the legal storm unleashed in the twentieth century when new owners took over the Hotel Sacher and decided to assert their ownership of the Sacher trademark. In the 1920s, like Vienna itself, the hotel and family had fallen on hard times. This circumstance led to the sale of the hotel to one set of owners and the recipe to another. As of 24 July 1934, Demel’s, Vienna’s most famous pastry shop, put the “Eduard Sacher-Torte” on its menu. Meanwhile, at the hotel, the “Original Sacher-Torte” took pride of place. Hans Gürtler, one of the hotel investors and a lawyer, took Demel’s to court and eventually won the trademark dispute in 1938—even as the Nazis were marching into town. But that wasn’t the end of it. The suit resurfaced after the war and eventually made its way to the Austrian Supreme Court. At each stage of the appeals process, culinary experts and famous chefs stood on the witness stand, testifying about the dueling recipes. The point of contention was whether Franz Sacher’s original cake had one layer (Demel’s recipe) or two (the hotel’s). The judges, however, were more interested in the intellectual property aspect of the case rather than the fine details of baking. They ruled that while the original cake indeed had a single layer (the hotel’s cake was apparently split in the 1920s), the Hotel Sacher retained the right to call its bilevel confection “the original.” As a result, we have the Original “Sacher-Torte” and all the other Sachertortes. It is easy enough to taste the hotel’s version, as their kitchens make over 360,000 of them a year and ship them worldwide. The Original Sacher-Torte needs no more refrigeration than it did when Franz Sacher ran his catering business over 150 years ago.

See also austria-hungary; layer cake; and vienna.

salon de thé is a French food-service establishment that focuses on serving tea and coffee accompanied primarily by pastries and other sweet foods. Many exist as part of a pastry shop, though it is now not uncommon for cafés and restaurants to offer this same sort of service and describe themselves as a “restaurant, café, bar, salon de thé.” The salon de thé retains a heavily gendered and class association as a respectable gathering spot where bourgeois women would congregate in the afternoon, and its design reflects a certain propriety. As opposed to the French café, which is often on a street corner or a square, open to the street, and with tables oriented so that the clientele and passersby can stare each other in the face, the typical salon de thé would be located on the second floor, removed from the potentially prurient gaze of the pedestrian, yet often hung with mirrors so that the women patrons could gaze at and assess one another.

The term is a literal translation of “tearoom” and is an adaptation of the British original. According to the author of Les consommations de Paris (1875), the habit of eating meals in pastry shops was also a trans-Channel import. The first actual tearoom in Paris was opened in the 1880s by the brothers Neal, who ran a stationery and book store, the Papeterie de la Concorde, on the Rue de Rivoli. Initially, their salon de thé was no more than a couple of tables behind the counter, and its menu was limited to tea and cookies (biscuits); eventually, the brothers set up a proper tearoom upstairs. By 1900 five o’clock tea was all the rage, taken at pastry shops but also at the tearooms of swank hotels like the Ritz. Just how much actual tea anyone drank is questionable. Parisian women were more likely to prefer coffee or (hot) chocolate. However, neither the beverage nor the generally sweet food that accompanied it were the point for the French woman of leisure, as novelist Jeanne Philomène Laperche (writing under the pseudonym Pierre de Coulevain) noted in 1903: “The tea-room … makes a pleasant halting-place between her shopping and her trying-on [of clothes]. It answers two purposes—her wish to be sociable and at the same time exclusive.” In the early part of the twentieth century, the salons spread across France and eventually lost most of their English associations; drinking tea remained a largely bourgeois affectation.

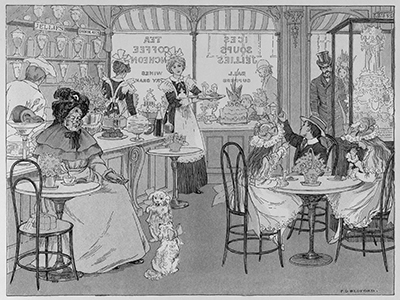

A salon de thé, or tearoom, was a fashionable British import to France. This lithograph of The Tea Shop by Francis Donkin Bedford appeared in The Book of Shops (1899). © the estate of francis donkin bedford. private collection / the stapleton collection / bridgeman images

Today, the traditional salon de thé has a decidedly old-fashioned, stuffy quality, perceived as a gathering place for women of a certain age or, in the case of marquee tearooms such as Ladurée, as a tourist trap. For a younger crowd, a more contemporary, informal version (still called a salon de thé) has taken its place. The purpose remains the same, even if rooibos and brownies have replaced lapsang souchong and a réligieuse, the mirrors now sport frames from Morocco, and the socializing takes the form of tweets and Facebook updates.

See also café; france; and tea.

salt, technically known as sodium chloride (NaCl), is one of the most important compounds in the human body. The International Journal of Food Science & Technology summarizes salt as a flavor enhancer due to its effect on different biochemical mechanisms. Salt regulates fluids in the body, assists in proper function of the adrenal glands, stabilizes heartbeats, balances sugar levels, aids in muscle contraction and expansion, and helps with communication within the nervous system. In the perception of taste, its role is essential. Without salt, the tongue would detect only the basic flavors of food.

Salt is essential to kitchen methodology, too. Ice cream owes its very existence to the discovery that when salt is mixed with ice, the melting point of the ice is lowered. That allows a mixture—such as that of cream, sugar, flavoring, and a bit of salt—to freeze and become ice cream. Today, most ice cream makers have self-contained freezers that require neither ice nor salt, but the original salt and ice mixture gave birth to the ice creams and ices that the world now enjoys. See ice cream.

There are numerous types of salts. Kosher salt, which originates from the sea or from the earth, is the most widely used in American professional kitchens because it has a larger grain that is easily picked up with three fingers to season dishes; it also disperses quickly and has a mild flavor. Another widely used salt is sea salt. Sea salt can come in crystalline or flaked form. It brings a punch of flavor to food and can also add a slightly briny note. Some specialty salts include black sea salt, pink Himalayan salt, volcanic red salt, seaweed salt, smoked Alaskan sea salt, Japanese sea salt, and cherry-smoked salt.

In bread baking, adding a 1.5 to 2 percent ratio of salt to flour, by weight, can enhance the flavor and texture of all breads. Furthermore, the addition of salt to items such as pretzels and buns after baking adds an entirely new dimension to baked goods. Whole-wheat flour benefits from salt because salt removes water from the wheat and brings the aroma and taste of the flour to the fore. The addition of salt to bleached flour can bring balance to an otherwise alkaline-tasting product. Salt should be used in bread baking to enhance the natural flavor of the ingredients; too much of it will destroy both flavor and enzymatic reactions in the dough.

Gluten development is further assisted by the addition of salt. When the gluten structures start to tighten, the dough holds on to carbon dioxide that has been released by yeast during fermentation. Salt will also control the yeast and prevent too much fermentation, which can lead to over-proofed dough. Starches in the flour are converted to simple sugars that feed the yeast. Salt’s regulatory effects on the yeast allow some of these sugars to remain, causing the dough to form a beautiful golden crust when baked.

Salt also balances sweet, and it enhances nuances of flavor in ingredients such as chocolate and caramel. A small amount of salt added to chocolate can bring out fruit flavors as well as other tangy and spicy notes that would otherwise go unnoticed. While caramel can be overly sweet, the slightest hint of salt will bring out its hidden smoky and buttery flavors. See caramels. In cakes, the presence of salt adds more depth. When egg whites are whipped and then folded into a batter, a small amount of salt helps the egg whites to hold their structure and add volume to the cake batter, which in turn produces a greater yield and a fluffier cake. See cake; eggs; and meringue.

Salt also plays a key role in leavening dough. Cookies, for instance, owe their light texture to chemical leavening with the assistance of an acid salt. See chemical leaveners. When an acid salt, such as baking soda (sodium bicarbonate, or NaHCO3), is added to dough, it releases carbon dioxide, just as yeast does in bread baking, the only difference being that the carbon dioxide is released at a specific temperature during the baking process, instead of before baking.

Dessert lovers especially prize the flavor and complexity of fleur de sel (flower of salt), once traditionally defined as the finest hand-harvested sea salt. In Guérande, Brittany, the chore was entrusted to women because men were considered too rough for such a delicate operation. Fleur de sel de Guérande is still hand-harvested, but some fleur de sel is now gathered mechanically. Today flurries of fleur de sel, whether artisanal or industrial, are sprinkled onto or into all manner of sweets—chocolates, caramels, ice creams, cakes, brownies, and cookies.

An appreciation of salt is paramount for the development of a chef’s career. Great chefs understand the true complexity of salt, even though most people perceive it as a simple ingredient.

sandesh is the Bengali word for “message,” as well as a popular sweet prepared from chhana (fresh curd cheese) and sugar or palm sugar jaggery cooked together to varying consistencies, depending on the desired result, which can be meltingly tender or dense and chewy. Sandesh is often pressed into decorative wooden molds and is sometimes filled or flavored with essences both native and exotic. Its preparation requires synergy between a ununer karigar (an artisan skilled at cooking the mixture), his skill with a tadu (a long ladle with a wooden blade used to prepare the sweetened mixture), and a patar karigar, an artisan who sits near a wooden board (pata) and magically rolls out sweets with his fingers.

In an occupation that seems to breed invention, regional sweet makers have developed numerous local specialties. For instance, in Chandannagore (part of the former French colony of Hooghly), in the early nineteenth century, Lalit Mohan Modak, grandson of Surjya Kumar Modak, created a wooden mold shaped like a palm kernel (talsansh in Bengali). A denser chhana was added to molded sweets with a rosewater-scented filling to meet the request of a local strongman who wanted to surprise his son-in-law on the occasion of Jamaishasthi, the feast honoring sons-in law. Popularly known as Jalbhara talsansh sandesh, this nineteenth-century creation from Surjya Modak’s humble establishment still draws many sweets lovers to the two shops run by his descendants.

Over time, sandesh flavored with kiwi, strawberry, mango, vanilla, and chocolate have been introduced. Low-calorie sandesh and diabetic sandesh prepared from chhana and sucralose are popular among weight watchers. While sandesh is just one of many sweets made and sold in most business establishments, Kolkata’s renowned Girish Chandra Dey & Nakur Chandra Nandy prides itself for specializing in selling “only sandesh” throughout the year.

See also india; kolkata; mithai; and palm sugar.

sanguinaccio is a kind of lightly sweetened sausage or pudding made in various ways throughout Italy with coagulated pig’s blood. When prepared in the form of a sausage, it is usually boiled for eating. Sanguinaccio is especially popular in northern Italy, Lombardy, and the Veneto in particular. In Val d’Aosta it is known as boudin, from the French, while in Tuscany it is known as biroldo. There are many dialect versions as well. Typical ingredients, depending on the region, are grape must, pine nuts, walnuts, chocolate, sugar, candied citrus, and milk. In Naples the pudding might be served with ladyfingers. Although sweet, sanguinaccio is not served as an after-dinner dessert; it stands on its own or is perhaps used as a dressing for pasta, as in the lasagnette al sugo di sanguinaccio (laganèdda cu sangìcchja) typical of the Gargano region in Apulia, where it is prepared during the pig slaughter. The pig’s blood is seasoned with lard, sugar, cocoa, cinnamon, tangerine zest, milk, and salt before being tossed with the pasta.

sap is a fluid that moves in either the xylem or phloem vascular system of a plant. Xylem sap is a watery solution of minerals taken up from the soil by the roots. It moves in xylem cells (vessel elements, tracheids) that form long rows of cylindrical pipes. The flow is driven by evaporation from the leaves, and a large tree can easily take up more than 100 liters of water a day in this way. Plants go through the trouble of extracting water from the soil with one primary goal: producing sugar. Most of the water is lost while obtaining carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and in photosynthesis, a process that converts light energy into chemical energy and stores it in the bonds of sugar molecules. Plants use phloem sap to distribute the energetic sugars throughout the organism, where they are used in growth and metabolism, and for producing sweet fruits such as apples. The liquid flows in sieve element cells, which form a channel network running throughout the plant. Phloem sap contributes to many natural sweeteners, such as flower nectar and palm sugar. See palm sugar.

Sap contains a diversity of sugars, including glucose, fructose, sucrose, sorbitol, mannitol, raffinose, and stachyose. See fructose; glucose; and sorbitol. Most plants, however, transport sucrose, commonly known as table sugar. See sugar. Although the sugar concentration varies among species, phloem sap typically contains 20 percent sugar, twice as much as Coca-Cola (10 percent). There are two good reasons why phloem sap contains so much sugar. First, it is difficult for animals and insects to feed directly on the phloem, because their guts cannot process the very high sugar content. Second, while sweet sap has the greatest transport potential, viscosity impedes flow, and 20 percent is the most effective concentration for long-distance transport. Although plants have generally evolved toward this optimum, a number of unusually sweet plants exist. This group consists primarily of crop plants such as corn (41 percent) and potato (50 percent), the sugar junkies of the natural world.

Both xylem and phloem sap can be tapped for use in sweeteners, but owing to the plant’s natural defenses, it is usually only possible to extract miniscule amounts of sap. A notable exception is found in the production of palm sugar, where phloem sap readily flows from cuts made to the inflorescence, or the flowers. A well-known sweetener that originates directly from xylem sap is syrup made from sap tapped from trees in the early spring, when cool nighttime temperatures are followed by days with rapid warming. See maple syrup. Maple and birch xylem sap tapped under these conditions contain a few percent sugar; the sap is subsequently boiled down to produce syrup.

See also native american.

Sara Lee, one of the best-known producers of refrigerated and frozen baked goods in the United States, became famous for such products as pound cakes, coffee cakes, and New York–style cheesecake. See cheesecake; coffee cake; and pound cake. The company’s memorable and long-running slogan, “Everybody doesn’t like something, but nobody doesn’t like Sara Lee,” was written by Mitch Leigh, composer of the musical Man of La Mancha. Operating around the globe and now encompassing far more than baked goods and breads, Sara Lee’s major brand-name products include Ball Park Franks, Chef Pierre pies, Hillshire Farm meats, State Fair foods, and Jimmy Dean foods.

The original company began in 1935 when 32-year-old Charles Lubin and his brother-in-law, Arthur Gordon, bought a small Chicago-area chain of neighborhood bakeries called Community Bake Shops. The company prospered. When Lubin took over sole ownership in 1949, he named his first product, a cream-cheese-based cheesecake, after his then eight-year-old daughter and changed the name of the business to Kitchens of Sara Lee. In 1951 Lubin introduced the soon-to-be famous All Butter Pound Cake, followed by the All-Butter Pecan Coffee Cake. Both were enormously popular.

Most baking companies attract customers by keeping prices low. Lubin’s marketing strategy was to focus on quality first, even though some of his products sold for twice the price of the competition. He demanded fresh milk, pure butter, and real eggs in his baked goods. His cheesecake contained almost a pound of quality cream cheese. The excellence of the ingredients was touted in the company’s advertising. One ad campaign carried the tagline, “Sara Lee Cakes, they’re all better because they’re all butter.” Until the early 1950s, however, because of their perishability, Sara Lee Kitchens had to limit the delivery of fresh-baked cakes to a 300-mile radius of Chicago.

By 1953 Lubin had perfected a line of frozen bakery products that retained the quality he demanded while offering mass-distribution capabilities. The following year, working with the housewares manufacturer Ekco, the company developed an aluminum foil pan in which products could be baked, quickly frozen, shipped, and sold. Sara Lee frozen products would be in all 48 states by 1955. Over 200 frozen Sara Lee products are sold nationwide today, including Cream Cheese Cake, Butter Pecan Coffee Cake, All Butter Chocolate Cake, Banana Cake, Apple’n Spice Cake, and Chocolate Brownies.

Lubin’s aluminum baking pan was a major revolution in the food industry and helped usher in the era of convenience foods. In 1954 Swanson used Lubin’s innovation to introduce TV dinners, and within a year Sara Lee began selling its cheesecake nationally. At this time the dessert was still closely associated with Germans, Jewish Americans, and New York City, but thanks to the company’s wide reach, cheesecake soon lost its ethnic and regional associations.

In 1956 Sara Lee was acquired by Consolidated Foods Corporation, headed by Nathan Cummings, a successful Canadian-born importer of general merchandise whose first venture had been to purchase a small biscuit and candy business, which he later sold for a profit. In 1939, at the age of 43, Cummings had borrowed $5.2 million to buy C. D. Kenny Company, a Baltimore wholesale distributor of sugar, coffee, and tea. He built his new company through acquisitions, a strategy he followed until retiring from active management in 1968. Because Sara Lee was one of Consolidated’s best-known brand names, in 1985 the company adopted Sara Lee as its corporate name, and the Kitchens of Sara Lee was renamed Sara Lee Bakery.

On 4 July 2012, Sara Lee Corporation was split into two companies. The North American operations were renamed Hillshire Brands (makers of Jimmy Dean, Ball Park, and State Fair brands), while the international coffee and tea businesses became D. E Master Blenders 1753. The Sara Lee name continues to be used on bakery products and certain deli products distributed by Hillshire Brands.

sartorial sweets —clothes made with sugar—are surprisingly ubiquitous. Sugar weaves its way into fabrics both synthetic and natural, and clothing made of sweets offers a provocative aesthetic.

Several familiar fabrics are manufactured from molecules of sugar that nature has already stitched together. Cotton and linen consist largely of cellulose, a polymer in which glucose molecules are connected to each other, much like a line of dancers linking arms. Cotton fibers are unbranched, spiraling chains of cellulose, the strength of the fiber being directly proportionate to the length of the chain.

Linen is constituted of a cellulosic polymer derived from the bast fibers of flax plants. More brittle than cotton (think of all those wrinkles), linen consists mainly of glucose and xylose; other sugars are present in small amounts. See glucose.

Seersucker, a lightweight cotton that requires no ironing, is favored for summer suits and tropical climates. The weave is such that the cotton puckers into characteristic squares or rectangles. The puffed shapes, reminiscent, perhaps, of plump rice grains, give seersucker its name, which in Hindustani means “rice pudding and sugar” (kheer aur shakkar), an appellation that originated with the Persian shiroshakar, or “milk and sugar.”

The Japanese company Sugar Cane & Co. produces a sturdy denim from sugarcane. And a vegan version of leather is made by cultivating bacteria in sweetened green tea until a sheet forms, which can then be cut and fashioned.

Rayon, sometimes called “artificial silk,” is a cellulose-based synthetic. Adipic acid, one of the main components of nylon, another synthetic, is produced from sugars extracted from fruit peels. A new manufacturing process for obtaining adipic acid, less costly and more efficient than the original one, may help nylon once again step out in style.

Sweet Crinoline

Starch, a sugar polymer, lends stiffness and shape to fabric, expanding the ways in which it can be fashioned into clothing. See starch. The stiffness of starch should not, however, distract from the more playful—and seductive—ways in which sugar is incorporated into apparel.

Cellulose can be digested only by bovine, ovine, or caprine diners. Insofar as it refers to a straw boater, the expression “I’ll eat my hat” thus cannot be applied literally. Nevertheless, a variety of edible “hats,” mostly cakes shaped and frosted accordingly, have made it possible to swallow one’s words.

The jacket of Herb Albert’s Tijuana Brass mid-1960s record album, Whipped Cream & Other Delights, featured a woman lusciously clothed in whipped cream, licking some off her finger. A fabric called whipped cream came into style at about the same time: the “textured whipped cream mod dress” was made of white fabric with a wavy pattern that looked slightly quilted—and very à la mode.

Hearts Worn on Sleeves, and Melting

More recently, the Ukrainian pastry chef Valentyn Shtefano created for his bride a dress consisting of 1,500 cream puffs; one can only wonder how the wedding feast ended. Shown in Munich in 2010 was a German chocolate bubble dress, so called, apparently, because of the shape of its skirt. More chocolate fashions are displayed at the annual Salons du Chocolat held in Paris, Tokyo, and New York. The gowns, inspired by chocolate, certainly look delicious, though it is not clear whether they are actually edible. Those preferring greater exposure might order, perhaps as a Valentine’s Day special, a chocolate thong.

Designed for a younger crowd are candy necklaces, consisting of small, disk-shaped NECCO-like candies with holes in the middle, strung on a string. If long enough, the necklaces can be worn and eaten simultaneously. See necco.

As this brief glimpse into the sweeter side of the textile and fashion industries indicates, sugars continue to be reconfigured into fabrics and sweets concocted into ready-to-wear marvels.

See also sugar, unusual uses of.

sauce often completes a dessert. Whether served on a plate, in a bowl, or in a glass, dessert gains a punctuation mark from a hot or cold sauce served on, under, or beside it to amplify a principal flavor or provide contrast. There are seven main categories of dessert sauces:

No matter which sauce is used, the idea of providing contrast in flavor, and often in texture, is paramount. For example, a sweet dessert is well complemented by a tart or even acidic sauce, as in a white chocolate mousse served with a tart citrus sauce, either lemon- or lime-based. On the other hand, an only slightly sweet rhubarb tart could be accompanied by a vanilla crème anglaise to achieve an overall mellow sweetness in the dessert. From the point of view of texture and mouthfeel, silky smooth sauces of all kinds provide contrast to a wide range of desserts, from crunchy praline-based ice cream to flaky stacks of puff pastry layered with pastry cream and fresh fruit.

Dessert sauces can also offer temperature contrast. Perhaps the best illustration of this concept is the classic American hot fudge sundae, in which hot and cold coexist in a single spoonful. See ice cream. In a slightly different way, the beloved American dessert apple pie à la mode reveals how temperature variations can elevate the simple to the sublime; as the ice cream melts, it turns into a cool sauce beside the warm pie. See à la mode.

Scandinavia historically refers to Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, countries in which sweets are very popular and well integrated into the culture, even though the concept of a formal dessert course is relatively modern.

Before sugar reached northern Europe, Scandinavians relied on honey and fruit extracts for sweeteners. In the Middle Ages, spice cakes made of rye, oats, and honey were enjoyed, as were sweets that could be baked over an open fire with special cast-iron equipment. Sugar changed all that. Like much of Europe, Scandinavia has a dark chapter in its history: in 1672, Denmark established a colony on St. Thomas in the Caribbean, and thus took part in the sugar trade based on slave labor. See slavery and sugar trade. As new methods of baking reached the north from France and Austria, sugar became a sought-after commodity. Scandinavian bakers traveled to Vienna, bringing back new ideas that led to the creation of different kinds of baked goods, in which the bourgeoisie was eager to indulge. What Americans know as “Danish pastry” is one such result; its Danish name of wienerbrød (Viennese bread) reveals its origins. See vienna.

Bakeries were situated primarily in cities and towns, while home baking took place in rural areas, mainly on large farms and estates that had sufficient staff, easy access to dairy, and money to buy sugar. In this way country houses and bakeries throughout Scandinavia were responsible for developing a wide range of cakes and desserts named after famous people. Napoleon cake is a classic mille-feuille made with red currant jelly; Sarah Bernhard consists of a macaron topped with chocolate ganache and coated in dark chocolate; and Prinsesstårta is a beloved Swedish cream-filled layer cake draped with a sheet of pale green marzipan. See marzipan.

In the late 1800s, inviting people for a “cake table” was a popular rural pastime in Sweden. Fifteen to twenty different cakes would be served with coffee, cold milk, and sugar. This tradition soon extended to funerals. People were invited home for cakes and coffee after the church ceremony, or they gathered at the local community center, which was used for gatherings and celebrations. On a more daily basis, coffee breaks, known familiarly as fika in Swedish, have been part of life throughout Scandinavia for the last 200 years. They are an informal way for women to meet and share a cup of coffee, some cake, and the latest gossip. Today, they have largely been replaced by the coffee break at work.

In the early 1800s, in the larger cities, cafés called konditori began to open, and some, such as La Glace in Copenhagen and Sundbergs Konditori in Stockholm, still exist to this day. See café. Konditorier in Copenhagen were particularly famous for their celebrity patrons, including Hans Christian Andersen and the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard. Throughout Scandinavia these pastry shops offered a public space where people could meet and be seen in society.

Spices

Thanks to trade with the Hanseatic League, spices have been present in Scandinavia since the fifteenth century. They were used mostly in mjød, or mead, a fermented honey drink. See mead. When spices became more affordable around 1700, they began to be used more commonly. In Scandinavia, cinnamon, cardamom, and vanilla have been especially popular in baking for the last 200 years.

Vanilla is a basic ingredient in many cake recipes and is also found in candy and caramels. See caramels. Cinnamon is used in many ways. Arguably most famous is the cinnamon bun, of which commercial and home versions exist, along with regional variations. The kanelsnegle is a Danish pastry for which cold butter is rolled into dough that is coiled around a sweet cinnamon filling. The most widespread cinnamon buns, called kanelbullar, are made with yeast dough, with melted butter added. They are offered by almost every baker throughout Scandinavia. Similar to kanelbullar are kardemummabullar, which use ground cardamom instead of cinnamon. Cardamom is used throughout Scandinavia to enhance the flavor of almost all variations of blødt brød—the soft, sweet, yeasted wheat bread that forms the basis of many buns and cakes.

The most popular Danish Christmas cookies are peperkaker, pebernødder, brunkager, and ingefærkager—and their counterparts in Norway and Sweden—all of which are very thin, crisp cookies aromatic with spices like ginger, cinnamon, and cloves. The original recipes for these gingerbread cookies date back to the 1200s and 1300s. For best results the dough should rest for several weeks before being rolled out, to enhance the flavor of the spices. A cookie cutter cuts the peperkaker into various decorative shapes, while pebernødder are formed into small round balls. No master recipe exists; instead, there are many regional variations, and bakers prize their generations-old family recipes.

Seasonality

In Scandinavia everything is seasonal, even sweets, with different cakes served in winter and summer. Although this tradition historically had to do with a scarcity of ingredients, it continues today. Winter means that nuts, dried fruit, and spices are used for flavoring, whereas summer offers an abundance of berries: strawberries, raspberries, gooseberries, red and black currants, and rose hips. In particular, layer cake, variously known as lagkage, blødkage, and tårta, and traditional for birthday parties throughout Scandinavia, is made very differently depending on the season. In the summer a sponge cake is cut into three layers, each of which is spread with cold custard and fresh berries. In the winter, jam or plain whipped cream replaces the berries. See custard; layer cake; and sponge cake. The cake is usually decorated with marzipan, chocolate, or confectioner’s sugar. Layer cakes can be simple or elaborate, baked at home or bought from the local bakery. After World War II, new products like prebaked cake layers and instant custard powder came onto the Scandinavian market. With a jar of jam and whipped cream from a spray can, one could make a layer cake in 30 minutes, not an uncommon practice even today.

In Denmark the first apples of September are baked into the traditional apple cake—thick apple sauce layered with sweet roasted bread crumbs and whipped cream, and served cold. Because Norway and Sweden have much shorter growing seasons, summer is fleeting, making the first berries of the season cause for celebration. They are added to cakes, luscious puddings and pies, and pressed for juice and made into preserves. See fruit preserves. Especially prized in northern Scandinavia are tart lingonberries and golden cloudberries. Elderberries and aromatic elderflowers are also made into refreshing summertime drinks and desserts throughout the region.

Other Baked Goods

Scandinavia has a wide variety of baked goods that are often served together on the afternoon or early evening cake table, a tradition celebrated especially by the older generation, for whom “seven sorts” of cakes were standard. More recently it has become fashionable among young people to invite friends for an old-fashioned cake table in a kind of retro gathering.

The selection of baked goods includes pastry, dry cakes, cream cakes, coffee cake, and, of course, the famous butter cookies. Danish pastry is eaten all over Scandinavia. Danish bakers added remonce, a sweet paste of sugar, butter, and nuts or marzipan, to the wienerbrød dough, and sometimes spices like cardamom or poppy seeds. Seasonal fruits or berries provide an alternative filling. Danish pastry is often eaten in the morning, like a croissant; when served in the afternoon with coffee, it is made larger and called wienerbrødsstang, meaning a “long piece” of pastry. Borgermesterkrans, or “mayor’s wreath,” is another wienerbrød variation.

Cream cakes became very popular in the late 1800s because of the strong tradition of dairy products in Scandinavia. The technologies of the Industrial Revolution allowed for cream and other dairy products to be kept cool in refrigerators, so that cakes could last throughout the day, which gave the bakers an opportunity to be creative. They came up with a range of cream cakes made with puff pastry, short crust, choux pastry, and yeast dough. See pastry, choux; pie dough; and puff pastry. Each type of cake has a distinctive name, such as the medallion, two round pieces of short-crust pastry filled with cream and a little fruit compote and decorated with chocolate or icing. See icing. A favorite type of small cream cake is the semla, a cardamom-scented yeast bun bursting with a mixture of marzipan and cream and topped with whipped cream and a dusting of powdered sugar, traditionally served at Shrovetide, the period of indulgence before Lent. Cream cakes are eaten for an afternoon coffee break, after dinner, or for a special occasion, although they can also be enjoyed simply on a rainy day or for some hygge, a Danish word that describes a special kind of comfort. These cakes are often purchased at a bakery. They must be eaten the same day due to their fresh ingredients.

Dry cakes have a longer shelf life, since they don’t contain any fresh dairy products. A typical dry cake is the so-called Napoleon’s hat, which consists of short-crust pastry and marzipan dipped in chocolate and formed into a shape resembling Napoleon’s hat. Linse is a type of short-crust pastry with a custard filling. Mazarin also has a short crust but is an open tart filled with marzipan, sugar, and butter. One variation includes fresh lingonberries, which in Sweden are often glazed with icing. Another famous dry cake is kransekage, made with marzipan, sugar, almonds, and egg whites. Kransekage became very popular among the aristocracy in the 1700s, when almonds were quite expensive, as a way to show off their wealth.

The horn of plenty—overflødighedshorn, or cornucopia—was created in the 1700s as a reference to Greek mythology. The horn was built out of rings of the kransekage, with small marzipan cakes inside. The idea is to fill the horn so full that the little cakes will spill over in abundance. It is made for special celebrations, weddings, christenings, and confirmations.

Pound cake, called sandkage in Danish, is every housewife’s savior. It is very popular for home baking and always appears on the cake table. The cake stores well and is therefore handy for unexpected guests, for whom the tradition is always to offer coffee and cake.

Småkager are butter cookies, an everyday treat with coffee. Fifty years ago, all housewives kept a store of småkager for unannounced visits. Once private homes were equipped with their own ovens, baking these cookies was easy to do, and they lasted for weeks in an airtight container.

Fried Pastries

The Scandinavian dessert repertoire includes a variety of fried goods, many of which date back to the days before ovens were common. Using cast-iron molds, they could be prepared over an open fire. Today these traditional cookies and cakes are rarely made at home, usually only at Christmas. Klejner or fattigman are crisp, twisted strips of dough often flavored with lemon zest and fried in hot oil. They vary from region to region: in Norway they are made with yeast and frequently decorated with icing after cooling; in Denmark they have no yeast and are served plain. Æbleskiver, with their pancake-like batter, are a Danish Christmas tradition. Traditionally, these plump pancakes are baked with either a slice of apple or prune sauce inside, though that practice is no longer common. They are fried in a little shortening or butter in a special cast-iron pan with round indentations. Sadly, very few Danes make æbleskiver by hand anymore, generally choosing to buy them frozen and reheat them in the oven. Æbleskiver are served with raspberry jam and powdered sugar; a glass of gløgg or mulled wine is the classic accompaniment. See mulled wine.

At Christmas, Norwegians serve krumkake, a thin, crisp waffle pressed in an ornately decorated two-sided iron that leaves its impression on the finished waffle. See wafers. While still warm, the krumkaker are rolled into cones; they are typically served with cloudberry jam. Rosette or struvor belong to an old tradition in Scandinavia. Like krumkaker, they are made with a special iron, often floral in shape, which is dipped into a liquid batter and then into hot oil. Today, rosettes are most often prepared in Scandinavian communities in the United States.

Candy and Licorice

Today, the Scandinavian sweet tooth is visible in worldwide brands of candy and candy stores. Modern Scandinavian candy stores are like supermarkets, where customers help themselves to a variety of candy and pay by weight. These shops have replaced the older style of shops where candy was bought and paid for individually. See penny candy. Such old-fashioned candy shops, called slikbutikker, existed in virtually all Scandinavian cities and towns. They are often described in children’s literature, as in Astrid Lindgren’s Pippi Longstocking. See children’s literature.

The Scandinavian love of licorice is a big part of the region’s candy tradition. See licorice. Licorice was first used as a cough medicine purchased at the pharmacy. As a nonmedicinal treat, licorice root became very popular in the early 1800s, and Scandinavian candy factories have been producing a range of hard, soft, sweet, and salty licorice for the last 200 years. There are now hundreds of corporate and artisanal brands to choose from.

Bolsjer are small, decorative pieces of hard candy made of pure sugar and fruit concentrates, or of other essential flavors. See hard candy. A few small artisanal producers still exist, such as Sømods Bolcher in central Copenhagen.

Over the past 50 years, many new, foreign products have been introduced to Scandinavia. However, when it comes to sweets, tradition remains strong. Although a significant number of small bakeries have closed over the last 20 years or so, a new generation of artisan bakers is making sure that the high-quality handmade products Scandinavian bakers are known for do not disappear. New trends are reinvigorating old traditions, such as the combining of chocolate and licorice in inventive cream cakes, or the use of fresh fruit instead of commercially prepared jam. Danish flødeboller—chocolate-coated marshmallows, sometimes with a layer of marzipan—have experienced a renaissance as chocolatiers experiment with new flavors like passion fruit, colorings like beet juice, and spices like cardamom.

Finland

Among the Nordic countries, Finland is often seen as an outlier, partly because Finns don’t speak the mutually intelligible languages of the Danes, Norwegians, and Swedes. The country’s culinary traditions differ, too, having been influenced by Russia rather than by the French haute cuisine embraced by the royal kingdoms of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Finnish culinary practices tend to be less elaborate than those of its neighbors. With nearly 40 different types of edible berries, Finland often features fruit in desserts, along with an enticing array of dairy products. In the summer, berries are baked into mustikkapiirakka, Finland’s iconic blueberry pie, or pressed and whipped into light-as-air vispipuuro, a lingonberry and semolina pudding. The oven-baked Åland pancake, a specialty of the Baltic islands between Finland and Sweden, is based on semolina or rice pudding inflected with cardamom and served with stewed prunes and whipped cream. On the mainland, Tiger Cake, a chocolate-marbled pound cake, appears on the coffee table that is as much a tradition in Finland as elsewhere.

Like other Scandinavians, Finns love salty licorice, especially the extremely strong salmiakki. They also share a love of crisp, deep-fried battercakes in the form of tippalëivät, which are traditionally served for May Day along with sima, a lightly carbonated lemon mead. The Russian influence can be seen in the use of sour cream in coffee cakes, and in the fresh cheese used for cheesecakes. See cheesecake and coffee cake. Cardamom is a favored spice that shows up not only in sweet desserts, but also in enriched breads like pulla. See breads, sweet. All manner of fruit soups—from blueberry in summer to mixed dried fruit in winter—remain popular in Finland. See soup.

See desserts, chilled.

servers, ice cream, constitute an entire category of serving utensils. Despite the fact that food chilled by ice existed in ancient Rome, and that forms of ices and ice cream became fashionable in elite European circles in the seventeenth century, the development of utensils specific to its serving is primarily an American story. See ice cream. European serving methods in the pre-mechanized eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries included elegant porcelain serving pails with matching or glass cups that would have needed little more than a serving spoon or even a tablespoon to serve the ice cream. A simple, small teaspoon could have scooped the ice cream out of a cup. Spoon-like implements with straight edges—ice cream spades—exist from the eighteenth century.

In the mid-nineteenth century, ice cream and its servers came to newly rich middle-class diners as part of an ever-expanding market for specialized flatware in the United States. The crank-driven home ice cream maker, the increased long-distance transport of large masses of ice by railway, and the lowering of sugar prices all came together in the mid-nineteenth century to broaden the volume of ice cream being served. To these developments was added the discovery of the Comstock Lode of silver in Nevada in 1859. From this easy supply of silver flowed a river of fancy new implements that complemented changing culinary tastes. Ice cream was among the foods that inspired creative and specific serving implements. It was thought to be best served with a spade or a “slice.” However, some serving sets included a pierced, pointed serving spoon that could lift a block of ice cream from the ice and let any melted water run off. The spoon could be paired with a knife that could also be used for cutting ice cream or cake. The frozen-solid hardness of ice cream and sorbets inspired the market for often gilded and engraved, specially designed, sharp-edged forks and spoons, ice cream spades, slices, saws, and hatchets.

These ice cream spades, saws, and hatchets appeared in endless possible patterns thanks to new technologies like the steam-driven, double-sided die-stamp that enabled more efficient production of sometimes elaborate motifs on both sides of the utensils’ handles. The wide range of patterns, as well as the variety of solutions for serving large quantities of ice cream, appealed to American consumerism. Yet, despite the number of patterns available for servers, and individual flatware to match, the ice-cream server often did not match the service pattern. Instead, it was a key example of the American fascination for developing function-specific utensils. Thus, an ice cream hatchet’s handle might try to replicate, in silver, an actual hatchet.

Serving ice cream, preferably with dramatic implements, played a leading role in the conspicuous consumption of those who could afford luxurious trappings. This service was accompanied by the display of specialized implements, especially forks, with which to eat the ice cream and sorbets. Even though ice cream was enjoying similar levels of democratization in Europe, these implements were more successful in the United States, thanks to skillful marketing that played on social insecurities, which implied that to be socially acceptable, one needed food-specific designs. The idea of eating ice cream and sorbet with an individual fork appeared as early as the 1840s, when Americans were still sensitive about not being savvy about fork usage.

The masculinity of the forms of some ice cream servers suggests that the owners of such pieces were not embarrassed to consider themselves products of American prosperity, rather than of the refined European aristocracy associated with ice cream in previous centuries. The hatchet and spade forms may also suggest that the serving of ice cream was exclusively the province of the butler or male server, rather than of a maid, given the force that was likely needed to cut the ice cream. A large amount of frozen ice cream might have been set in tower-like displays, some on stands with polar décor. The ice cream was then cut with a silver spade, hatchet, saw, or serving knife on the dining room sideboard to avoid melting in transit; a spade was used to portion the ice cream for each plate, from which it was eaten with a special fork, small spade, or shovel, all with a knife edge for cutting.

By the end of the nineteenth century, as refrigeration and the cost of ice cream fell, ice cream became a mass-market product. Nonetheless, elegant menus still showed a fascination with palate-cleansing ices served between courses, presented in glass containers from the pantry so that no fancy servers were needed. More significantly, the broader market meant that the ice cream servers were often relegated to the kitchen, and so less costly materials were used. As ice cream became standard with birthday cake, some twentieth-century ice cream servers doubled as cake servers, using a sharp or serrated edge for both. With mass-market appeal, stainless steel came to the fore between the world wars, and even silver servers often featured stainless-steel blades for strength. More casual presentations of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries have introduced brightly colored handles and circular metal scoops with a metal band that rotates to push the ice cream out into attractive balls for cones or bowls. Other innovations, such as cold-resistant silicone handles or metals that can be warmed to extract hard-frozen ice cream or sorbet from commercial containers, have replaced the spade or hatchet-like servers. Today, ice cream, no longer a luxury item, arrives in individual servings, including the cone, or with a spoon with which to eat it.

An engraved silver ice cream hatchet made by the Gorham Manufacturing Company, circa 1880. The growing popularity of ice cream in mid-nineteenth-century America, along with the proliferation of specialized tableware during the Gilded Age, inspired elegant serving pieces designed to cut through the treat’s frozen mass. dallas museum of art, gift of dr. and mrs. dale bennett / bridgeman

See also refrigeration; servers, sugar; and serving pieces.

servers, sugar, are necessary tools for the table, since sugar is used to adorn desserts and sweeten beverages. Over the years, as the forms of sugar have changed, so have the implements designed to serve it. An early place to store sugar on the table or sideboard was the sugar box, which was succeeded by the sugar bowl, and then the sugar caddy, primarily used to hold sugar for beverages. Sugar was retrieved from these boxes and bowls by means of nips or snips, scissors or tongs. Other early tools included casters or sugar sifter spoons used to shake sugar over fruit or other confections. In more recent years, sugar has been provided inelegantly at the table in simple paper packets or tubes, especially in restaurants.

Within the limited categories of sugar servers, there are many varieties in design. The greatest impact on the development of these objects occurred after the sixteenth century in Europe, when the introduction of tea, coffee, and chocolate led to a craze for these items among the elite. Although none of these beverages were generally imbibed with sugar in their native lands, Europeans perceived them as bitter. Before long, objects specifically designed around sugar added to the status of the beverage service and complemented the beautiful vessels made to hold them. During the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as tea, coffee, and chocolate pots and sugar bowls came into prominence, so too did various forms of nips, snips, tongs, and scissors. See chocolate pots and cups.

These silver sugar casters, made in Paris between 1730 and 1740, depict slaves carrying sugarcane, a reminder of sugar’s bitter origins. © rmn-grand palais / art resource, n.y.

Sugar boxes date back to the sixteenth century as storage containers appropriate for either the table or sideboard, for use with dessert or with the wine, which was sometimes sweetened. The significance ascribed to sugar can be seen in the generally high artistic levels of these objects, in their fine materials (often silver), and in their engravings and ornamentation.

Sugar caddies evolved as part of the tea equipage. Tea caddies were usually provided in pairs, for different types of teas, and sometimes included a third, larger box for sugar. This combination, usually made of silver but housed in a wooden box with mounts, evolved in the eighteenth century. Toward the end of that century, the tea set, which could include coffee and chocolate pots and hot-water urns, generally also included a matching sugar bowl, in which case the sugar caddy or box was replaced in a tea caddy set by a mixing bowl for the tea.

Sugar bowls appeared predominantly on the tea table, with coffee and chocolate at breakfast, or at the end of a meal. As sugar and tea became more affordable, the bowls grew in size. Early sugar bowls were often round in shape, their forms and decoration frequently reflecting those of the teapot. However, the first sugar bowls were not considered part of a set, and hence did not need to match. To keep the sugar clean and fresh, the bowls had covers that were lifted for retrieving the sugar with tongs or scissors; these implements never stayed in the sugar bowl, as is often common practice today. Silver and the prized porcelain imported from Asia, or of eighteenth-century European manufacture, were considered worthy materials for serving valuable sugar.

Sugar nips, nippers, or snips refer to the sharp-edged implements used to cut sugar into pieces small enough for serving. Sugar arrived from the refinery in loaves, cones, or coarse chunks that had to be separated and broken down further. See sugar refining. Scissor-like objects, generally known as sugar nips, with sharp, sometimes ridged fingers, were used to cut the lump sugar into small portions. The sugar could then be ground in a mortar, cut into even smaller pieces, or grated before being placed in a caster for sprinkling over food; the action of shaking created an even finer granulation. Cone and loaf sugar continued to be used throughout the nineteenth century in the United States, especially in rural areas, although once commercially granulated sugar became affordable, the cones were relegated to the kitchen.

Sugar tongs and scissors were designed for picking up lumps of sugar to put into a tea, coffee, or chocolate cup; the names reflect the different forms. Early sugar tongs often included two hinged or connected arms that could be pinched to grab a small lump of sugar. Some had sharp edges at the terminals to facilitate further crumbling. Sugar scissors, as the name suggests, were fashioned in the form of an X, with open, circular finger holes by which to grip and close the ends of the scissors around a lump of sugar. The scissor form became popular in the second quarter of the eighteenth century and remained so into the twentieth century, especially after Henry Tate introduced the sugar cube in London in the 1870s. See sugar cubes and tate & lyle. However, in the latter part of the eighteenth century, a simple, flat, elongated U shape became fashionable; it was easy to craft from a single sheet of silver and could be bright-cut or engraved with delicate decoration. With the increased consumption of tea, and the ever-increasing sizes of teapots and their accompanying sugar bowls, these tongs were easily made longer to accommodate the new bowl sizes. Tongs and scissors were not generally part of the tea set, but the U-form tongs sometimes did share engraved designs and initials, even armorials, with the sugar bowl.

Casters are usually found in the form of small towers, most frequently with baluster or octagonal sections and removable pierced domed caps. Initially they held sugar that had been grated from cones or chunks; as sugar became more refined, they later held granules and confectioner’s sugar. See sugar. When casters first appeared in England in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century, they were considered appropriate gifts for noblemen, on the order of objects like pomanders for spices and perfumes. Some early standing table centerpieces featuring “salts” for another prized commodity included some sort of pierced component, possibly for sprinkling sugar or spices. The development of the three-caster box or set, with one larger sugar caster and two smaller ones for pepper and dried mustard, did not appear until the era of the English dessert banquet in the late seventeenth century. See banqueting houses.

Sugar sifter spoons function in much the same way as casters, holding grated lump, granulated, or confectioner’s sugar that can be sprinkled by shaking the spoon from side to side. Their sharp-edged pierced decorations allow sugar to sprinkle through the piercings. While the exact date of their origin is unclear, the earliest sifter spoons, with fairly deep bowls and long handles, seem to have appeared in the latter part of the eighteenth century. Their popularity in the nineteenth century and later is probably due to the advent of mechanized sugar refining and the patenting of a powdered sugar machine in 1851, which meant that sugar could be sprinkled in a more highly refined state from the spoons.

See also serving pieces.

serving pieces are the objects and tools devised for presenting sweets. Historically, they were treasured—stored separately and not in daily use. Examples include the Limoges enamel valued at the sixteenth-century Valois court, or the Venetian bowls in Henry VIII’s Whitehall Glasshouse. Some pieces were exotic, such as the gilded and lacquered “wicker China” at Salisbury House, London, in 1612. In Renaissance Italy, tin-glazed istoriato dishes painted with classical myths were popular. Dutch and English customers had tin-glazed plates painted with moralizing or mocking rhymes, successors to the earlier trenchers, which were disks of thin beech wood. Painted and gilded with a motto or a biblical text, these delicate mats had a plain side for candied fruit. See candied fruit.

Imported Chinese porcelain arrived in Italy beginning in the late fifteenth century, and from the mid-sixteenth century it rapidly became the desired material for serving fruit across northern Europe. The silver-mounted Imari porcelain service of Charles of Lorraine (now in Vienna’s Imperial Silver Chamber) shows how colorful ceramic services imported from China and Japan retained their appeal well into the eighteenth century.

In the early seventeenth century, fruit, a prestigious delicacy, was set out on broad “scalloped” dishes, as listed in Charles I’s inventories in the 1630s; beginning in the 1660s, this style was superseded by standing dishes on trumpet feet. For evening parties at courts, sugared fruit was piled up in decorative silver trays. Apart from the decorative pastry lids on pies and tarts, height was the desired effect. Service en pyramide created height by stacking graded salvers called porcellanes, a term used from the mid-sixteenth century, even though the salvers were not always made of porcelain. At the 1668 peace celebrations at Versailles, dessert was served in seize porcelains en pyramide.

New delicacies such as flavored creams required new serving wares. Between 1637 and 1639, Viscountess Dorchester’s dessert closet contained a sugar box, “cream bowls of china garnished with silver, China dishes, glasses and bottles … 5 drawers full of Chinay dishes and glass plates, a dozen tortus shell dishes.” Robert May, in The Accomplisht Cook (1678 edition), recommended “little round Jelly glasses,” to be stacked up on salvers. Before the early eighteenth century, flat ceramic plates and dishes were hard to fire in kilns. Metal or lead glass offered an alternative: “The broader your cream dish, the more beautiful your cream will look,” as Rebecca Price advised in 1681. She also recommended a silver server (salver) for “Jelly Lemons” and a salver for “Spoonefulls of Spanish Cream.” In 1702 the French chef Massialot recommended “China” for wet sweetmeats in his Nouvelle instruction pour les confitures.

Porcelain offered shiny color and ornament for ladles, bowls, and dishes for cream and compotes, as well as for plates painted with flowers and dessert tureens shaped like fruit. At Chelsea in 1755, a “compleat service for the dessert” featured large cabbage leaves, vine leaves, and small sunflower leaves. By the 1770s, European porcelain factories were making special ice-filled ceramic bucket-shaped containers, with a central saucer, for serving ice cream. See ice cream. The Meissen, St. Cloud, Chantilly, and Sèvres factories all supplied porcelain handles for dessert flatware. At Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1770, Governor Botetourt had a case of flatware “with China handles,” plus gilt-handled dessert sets, standard since the late seventeenth century. Diners often carried small folding pocketknives for fruit.

A new implement, a silver trowel devised for dexterous lifting of delicate pastries and cakes, was adopted from Oslo to London by 1720. Porcelain and creamware trowels soon followed. For serving ice cream, two-handled glass or porcelain cups, presented on small salvers, became standard, as depicted in M. Emy’s L’Art de bien faire les glaces d’office (1768). See emy, m. Silversmiths created spades with curved sides to slice the ice cream. See servers, ice cream. Gilding remained the preferred finish for both serving implements and dessert wares. In the 1760s the botanically knowledgeable second Duchess of Portland ordered a complete service, including blackcurrant and strawberry leaf dishes for fruit tarts, candelabra formed as plant stems with insects and butterflies, and serving spoons and forks with leaf-encrusted handles and bowls. These themed dessert services suited the eighteenth-century concept of summer dining al fresco in garden houses and grottoes, or on a boating lake, as at Wanstead House.

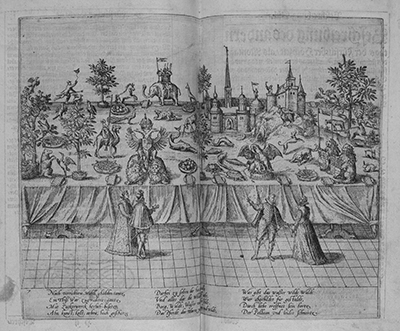

At all social levels, setting out a dessert was a valuable skill. Banquets (desserts) at sixteenth-century European courts are known about mostly from descriptions by heralds and stewards, images of royal marriages, feasts of knightly orders (the Garter, St. Esprit), and feasts held for imperial elections. In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, professional table deckers created striking effects with silver, glass, and porcelain. For evening assemblies from the 1740s, epergnes in all these materials, with small hanging baskets for sweetmeats and sugared fruit, were popular. See epergnes. For large feasts, serving wares were rented from goldsmiths, glass sellers, and confectioners. In the 1760s, Domenico Negri depicted on his trade cards the fanciful dessert centerpieces on Chinese, marine, and classical themes available to rent from his premises at the Sign of the Pineapple in London’s Hanover Square.

Exceptional creations attracted comment in the press: the royal goldsmith Hugh Le Sage made for the Prince of Nassau “a very curious piece of wrought plate (for a desert) of exquisite workmanship” (Daily Advertiser, April 1731). For the Duke of Richmond, a 1730s list of “Things to be gott in Paris” included a confectioner and “a compleatt sett of desert dishes with looking glasses.” Mirror centerpieces, fashionable from the early eighteenth century, were dressed with clusters of porcelain figures and sugar flowers, which were replaced in the early nineteenth century by gilded stands for fruit or fresh flowers.

French and English handbooks of instructions, such as Hannah Woolley’s Queenlike Closet or Rich Cabinet … of Rare Receipts (for) … Ingenious Persons of the Female Sex (1670) or The Whole Duty of a Woman (1737), stress the importance of symmetry in the layout but rarely specify the dishes. In Manchester the confectioner Elizabeth Raffald recommended a “Deep China Dish” as the centerpiece for a dessert. Classes for women in pastry making and dessert planning were held in London in the 1720s and later.

Wealthy owners of costly porcelain dessert services often showed them in glazed display cases near the dining room, as at Apsley House, London, and Alnwick Castle. Exceptional eighteenth-century Sèvres services can be seen at Waddesdon Manor, the Rothschild Collection (Paris), and Woburn Abbey. Other European porcelain services made for imperial and princely households are in St. Petersburg, Vienna, and Munich. Beginning in the 1760s, creamware, aimed at middle-class consumers, offered a cheaper decorative substitute for porcelain. The best known are Queens Ware services from Wedgwood’s factory, often decorated with transfer printing; Leeds potters produced a variety called pearlware. Baskets with pierced borders were popular at all social levels. These English wares were widely exported.

Once the concept of the restaurant was invented in Paris in the 1760s, this new setting increasingly offered an agreeable environment alongside confectioners’ shops for respectable women to eat in public, and restaurants gradually transformed the preparation of sweets. More-complex and fashionable delicacies such as ice cream, puff pastry, and meringues became treats to be prepared by professionals and consumed away from home. See meringue and pastry, puff. Serving wares for commercial eating places were elaborate, adopting conventions such as special tiered stands for cakes, and tall glasses for iced confections. See cake and confectionery stands.

Beginning in the early nineteenth century, the variety of serving implements for desserts multiplied, driven by new dining practices, industrial innovation, and the constant invention of novelties. In the 1840s, Elkingtons, an entrepreneurial Birmingham firm, and Christofle in Paris almost simultaneously invented techniques for electroplating flatware. Shiny but much less expensive than sterling silver, and more durable than the earlier silver substitute known as Sheffield plate, this new material was fashioned into a huge range of slices, scoops, knives, and spoons.

American manufacturers were inventive in devising tools for particular delicacies. This “jewelry of silver,” a term used in Scribner’s Monthly 1874 article “The Silver Age,” ranged from oyster forks to “knife-edge ice cream spoons,” sawback cake knives, and servers for asparagus, celery, berries, pastries, and salad.

Machine-made pressed glass offered a decorative and colorful alternative to cut glass, which continued to be admired throughout the nineteenth century. Mid-nineteenth-century housewives appreciated colorful porcelain dishes and plates that reproduced rococo design of the 1740s and 1750s, including shell-shaped baskets and comports for fruit. As illustrated in Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management (in many editions from 1861), dessert tables were still laid in a symmetrical arrangement, echoing the location of the earlier savory dishes, with the addition of trowels, grape scissors, and decorative serving spoons, as well as small knives, spoons, and forks with gilded or mother-of-pearl handles. See beeton, isabella.

Today, informality in eating, driven by a lack of time to prepare foods as much as by changing attitudes to diet, means that desserts are rarely elaborately presented at home. However, a birthday or other celebration still merits a special effort, such as bringing out a treasured old dish or bowl and small forks. Restaurants and caterers for large dinners compete to present their confections with style, although the wares and tools are usually simple, practical expressions of contemporary design.

See also banqueting houses; fruit; and sugar sculpture.

sexual innuendo has coupled sweetness with love and sexuality since ancient times. In the Old Testament’s Song of Solomon, the female speaker equates her lover with sweet apples:

As the apple tree among the trees of the wood, so is my beloved among the sons. I sat down under his shadow with great delight, and his fruit was sweet to my taste. (2:3)

In his fourth-century work The Fall of Troy, Quintus Smyrnaeus alludes to “love’s deep sweet well-springs.” In the late thirteenth century “sweetheart” arose in English as a term of endearment, followed shortly after by “sweeting.” In the late sixteenth century “sweetikins” appeared: “She is such a honey sweetikins,” wrote Thomas Nashe in a pamphlet from 1596. “Sweetling” and “sweetie” appeared in the mid-seventeenth century, while “sweetie-pie,” “sugar pie,” and “sugar” emerged as terms of endearment around 1930. In 1969 The Archies released their hit song “Sugar, Sugar,” in which a “candy girl” is advised to “pour a little sugar” onto her boyfriend.

Not surprisingly, “honey” has also long been used as a term of endearment. In a fourteenth-century manuscript called “William and the Werewolf,” the hero tells his beloved, “Mi hony, mi hert, al hol thou me makest” (My honey, my heart, you make me completely whole). In a sixteenth-century bawdy poem by the Scottish poet William Dunbar, a woman calls her lover “my swete hurle bawsy, / my huny gukkis” (my sweet calf, my honey cakes). In the late nineteenth century “honey bunny” appeared, though a precursor might be found in a 1719 poem by Thomas D’Urfrey in which a lover proclaims, “My Juggy, my Puggy, my Honey, my Bunny.”

Sweet foods have also been used in sexual contexts to represent various parts of the human body. Slang words for the buttocks, for example, have included “hot cross buns” and “pound cake.” In addition, baked goods have been used as metonyms for female breasts, as with “cupcakes,” “apple dumplings,” and “love muffins,” but more often they are imagined as sweet globular fruits: apples, oranges, cantaloupes, mangoes, and especially peaches and melons. Sweet foods have also inspired several slang names for the penis, including “custard chucker,” “ladies’ lollipop,” and “sweet meat.” Slang names for the vagina have included “honey pot,” which was first used in a narrative published in 1673 called Unlucky Citizen: “Desiring by all means to gain his will on the Wench, and to have a lick at her Honey-pot.” “Jelly roll” was a popular slang name for the vagina in the 1920s, as was “fur pie” from the 1930s onward. The 1999 film American Pie, in which a teenager copulates with a warm apple pie, appears to have prompted the recent use of “apple pie” as a slang synonym for “vagina.”

The lyrics of many popular songs construe sexuality in terms of sweet foods. The term “jelly roll,” as mentioned earlier, was used as a slang name for the vagina and appeared in numerous jazz and blues songs of the 1920s, such as “I Ain’t Gonna Give Nobody None o’ My Jelly Roll,” “Nobody in Town Can Bake a Jelly Roll Like Mine,” and “The New Jelly-Roll Blues.” The latter song, as recorded by Peg Leg Howell in 1926, includes these suggestive lyrics:

Jelly roll, jelly roll, ain’t so hard to find.

Ain’t a baker shop in town bake ’em brown like mine

I got a sweet jelly, a lovin’ sweet jelly roll,

If you taste my jelly, it’ll satisfy your worried soul.

Sexual innuendo also characterizes the lyrics of Bessie Smith’s jazz classic “I Need a Little Sugar in My Bowl,” which she recorded in 1931: “I need a little sugar in my bowl, / I need a little hot dog, between my rolls.” Smith’s song “Kitchen Man” from 1929 is equally suggestive:

When I eat his doughnuts

All I leave is the hole

Any time he wants to

Why, he can use my sugar bowl.

Songs that made risqué use of sweet foods persisted throughout the twentieth century. Roosevelt Sykes, in 1961, sang, “I’m the sweet root man, try this potato of mine.” In the 1970s The Guess Who sang about a woman withholding sex from a man in their song “No Sugar Tonight.” Steve Miller admired a woman’s breasts when he crooned, “I really like your peaches, want to shake your tree,” and the Rolling Stones equated “brown sugar” with young black women: “Brown sugar how come you taste so good? / Brown sugar just like a young girl should.” In some song lyrics, sweet foods were employed as stand-ins for an erect penis: Tom Waits, in “Ice Cream Man,” sings, “I got a cherry popsicle right on time / A big stick, mamma, that’ll blow your mind,” while 50 Cent in “Candy Shop” says, “I’ll take you to the candy shop, / I’ll let you lick the lollypop.” Contemporary pop stars continue to honor the tradition of sweet and bawdy lyrics. In her 2013 album Blow, Beyoncé croons, “Can you lick my Skittles, it’s the sweetest in the middle, / Pink is the flavor, solve the riddle.”

See pastry, puff.

shape, perhaps against expectation, influences the way we perceive sweetness, leading to the question of whether sweetness itself has a shape. While the question might seem like a nonsensical one, a growing body of empirical evidence now documents the fact that the majority of Western consumers will match sweet-tasting foods with rounded (rather than angular) shapes. Why such an association should exist is not altogether clear. It may have something to do with the fact that both sweetness and roundness are treated as positive sensory attributes. By contrast, most Westerners match bitterness, sourness, and carbonation with more angular shapes, the link in these cases perhaps being that all three cues are associated with stimuli that are potentially dangerous or bad for us, and hence generally best avoided.

Shape Symbolism in Action

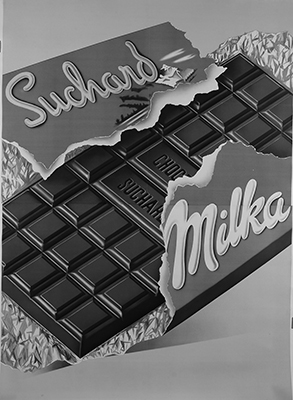

Foods are typically rated as tasting sweeter when they are served in a round format rather than a more angular one. Such an observation may help to explain why consumers complained following the introduction of the new, rounder Cadbury Dairy Milk chocolate bar in 2013, saying that the confection tasted sweeter following its change in shape. Mondelēz International, the company that currently makes the product, asserts that the recipe hasn’t changed. In the future, food companies may be able to use the cross-modal correspondence between roundness and sweetness to enhance the design of their product offerings.

Furthermore, once it is realized that taste attributes can be communicated by means of shape cues, a rich world of “synesthetic marketing” opens up. It can be argued that the labels, logos, and packaging of sweet products should be rounder (to set up the right expectation in the mind of the consumer), while products that are bitter or carbonated should be angular.

Desserts are rated as tasting significantly sweeter if served from a round plate than from an angular one, while food served from a white plate is perceived as tasting sweeter than food served from a black plate. Presenting a dessert on a round white plate may thus allow the chef to reduce the sugar content while not compromising on taste. No wonder, then, that many restaurateurs are now starting to sit up and take note of the emerging research on shape symbolism and taste.

Cross-Cultural Differences in the Shape of Sweetness