Häagen-Dazs belongs to the category of rich, dense, super-premium ice creams that have more butterfat and less overrun (air) than the average ice cream. Reuben and Rose Mattus created the upscale brand in their family-owned ice cream plant in the Bronx, New York. See ice cream and ben & jerry’s.

In 1921 young Reuben immigrated to New York from Grodno, Belarus, with his widowed mother, Lea Mattus. Reuben tasted ice cream for the very first time on Ellis Island, where newcomers were treated to the luscious dessert because it reinforced the concept of America as the land of plenty. Initially, Lea earned money by cooking for single men in her neighborhood. Then she partnered with one of the bachelors to start a business making Italian ices in the Bronx. Lea took charge, and under her frugal management the business reaped large profits. She expanded her product line, adding ice cream novelties and bulk ice cream.

Reuben worked for his mother, learning every aspect of the business. In 1936 he married a gregarious, energetic young woman named Rose Vesel. Only months after their marriage, the newlyweds bought out Lea’s partner. Reuben had fresh ideas for the business. He knew that the food industry was changing and that the Mattus company must change, too, but Lea vetoed his ideas.

After World War II, food conglomerates monopolized the space in supermarket freezers, squeezing small companies out of the marketplace. To prosper, the Mattuses needed a unique product that would fill a market niche overlooked by the big corporations. Reuben planned to survive by catering to a special segment of the market. He wanted to make an ultra-rich, top-quality ice cream that would attract consumers willing to pay extra for superior taste. Although Lea never put her stamp of approval on his plan, she gradually relinquished control.

In the late 1950s the Mattuses marketed a high-quality ice cream called Ciro’s. Sales were very good, but Ciro’s did not quite fulfill Reuben’s vision. He continued to tweak his formulas until he created exactly the right flavors and texture. He wanted a sophisticated, cosmopolitan image for his new brand, so he put a map of Scandinavia on the container. He coined the name Häagen-Dazs because he wanted it to sound Danish.

Initially, the Mattuses sold only three flavors of their new brand: vanilla, chocolate, and coffee. They expected Häagen-Dazs to find a niche, but they were surprised by the nature of the market. Rose later described it as “an alternative market … steeped in the marijuana culture of the ’60s.” The brand’s first fans “were a motley assortment of oddballs with long hair, fringe tastes, and decidedly eccentric business styles.” Like cool evangelists, the hippies spread the word about the great new ice cream with the funny name.

In 1976 Rose and Reuben’s daughter Doris Mattus Hurley opened the first Häagen-Dazs scoop shop, a successful venture that led to a chain of shops. In 1984 the Mattuses sold Häagen-Dazs to a food conglomerate, which later resold it. The brand expanded by adding new flavors and products, including ice cream bars, frozen yogurt, and sorbet. The company is now under the umbrella of General Mills.

Halloween is a fall festival celebrated on 31 October, mainly in the British Isles and North America (although since the mid-1990s its celebration has become popular in parts of Continental Europe, Asia, and South Africa). The name Halloween derives from All Hallows’ Eve, or the evening before All Saints Day, a Catholic celebration that was moved to 1 November (from its original date of 13 May) in the eighth century. The date was probably chosen to co-opt the pagan New Year’s holiday of Samhain, celebrated by the ancient Irish Celtic tribes.

Because of its placement in the calendar, Halloween has always been associated with harvest and food. Apples were sacred to the Celts, and the red fruit has been part of Halloween throughout its history, serving as game (bobbing for apples), fortune-telling device (often involving paring an apple, with the form of the parings indicating a future spouse’s initials), and food (most recently caramel apples, or apples on a stick covered with thick caramel sauce).

Halloween’s association with sweets, however, may have begun because of another holiday that was added to the festival: in 998 c.e. All Souls’ Day was designated as a day of memorial, celebrated on 2 November. The day was initially added to the celebration of All Saints’ Day as a way for families to commemorate their own deceased members as they had the saints; by the sixteenth century “soul cakes” were distributed to beggars in exchange for prayers for the souls of loved ones in Purgatory. These small, flat, round cakes were usually made with milk, eggs, and spices, although sometimes fruit or seeds were added. “Souling” became the name for the act of going house-to-house begging for cakes, or offering a small musical performance in exchange for cakes.

In 1647 the British Parliament banned the celebration of all Catholic festivals, but Halloween was still enjoyed in Scotland and Ireland. The Irish have long celebrated Halloween with a traditional cake called “barm brack,” made from dried fruit and strong black tea. See fruitcake. This cake is often baked with small charms inside of it, giving it the name “fortune cake.” Whoever receives a slice with, for example, a ring will be married soon, while a coin might indicate wealth, or a thimble, spinsterhood.

In the nineteenth century, as famine drove many of the Irish and Scots across the Atlantic to America, they brought their customs to the New World’s large middle class, which had a fondness for parties and found Halloween, with its ghost stories and fortune-telling games, ideal for their children. By the 1870s American magazines were full of stories and articles about children’s Halloween parties, with “pulling molasses candy” (also known as “pulling taffy”) a typical activity (this candy, made largely from molasses, brown sugar, butter, and water, is pulled into long, thin strips as it hardens). See taffy. Pulling candy may have been especially popular at Halloween parties because of the way the strips occasionally curled to suggest arcane symbols and mysterious shapes. The fortune cake and apples remained characteristic Halloween party foods well into the twentieth century.

This Curtiss Candy Company advertisement appeared in Woman’s Day magazine in 1956 with the tagline “Be Good to Your Goblins!” By the 1950s, homeowners preferred to give Halloween trick-or-treaters commercially wrapped treats rather than go to the trouble of making homemade doughnuts and taffy.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, commercially manufactured candy began to appear at Halloween. Sold for use at children’s parties, the first store-bought Halloween candies were small sugar pellets sold in colorful containers (which are now highly collectible), but by the 1920s these had been replaced by candy corn, an inch-high, cone-shaped confection that combines white, orange, and yellow colors, roughly mimicking the appearance of corn kernels. First created by George Renninger at the Wunderle Candy Company in the 1880s, the candy combined mainly sugar, corn syrup, and wax, and, thanks to its autumnal colors, soon became a Halloween favorite. Produced now primarily by Brach’s Confections, candy corn variants are made for other holidays (e.g., Indian Corn, which includes chocolate, is sold at Thanksgiving) and has spun off similar products, such as Brach’s Mellowcreme Pumpkins, small orange and green pumpkin-shaped candies made from sugar, corn syrup, wax, and honey. Candy corn’s distinctive shape and colors have led to reproductions in candle form and ceramics.

Trick or Treat

By the 1930s the American Halloween celebration had become largely the province of pre-adolescent boys whose mischievous pranks on the night had gradually become more and more destructive as they moved into urban areas, until many cities considered banning the festival altogether. However, homeowners soon discovered that it was more practical to buy off the pranksters with planned activities, which included parties, games, costuming, and foods. A famed 1939 article “A Victim of the Window-Soaping Brigade?” from American Home magazine suggests inviting the mischief-makers into the home for doughnuts and apple cider, and provides possibly the first national mention of the term “trick or treat.” See doughnuts.

As a result of sugar rationing during World War II, the practice of trick or treat—in which costumed children go from house to house demanding treats in exchange for no tricks—did not become popular throughout the United States until the 1950s. See sugar rationing. Companies like Brach’s, Hershey, and Nestlé started to target Halloween in both production and marketing, and homeowners agreed that it was far easier to hand out pre-made, individually wrapped treats than to cook their own mass quantities of doughnuts and taffy. See hershey’s and nestlé. The increasing boom in candy sales at Halloween led to an entire side industry of trick-or-treat bags and buckets—used by children to collect their voluminous Halloween sweets—often shaped and colored like jack-o’-lanterns.

Soon the popularity of candy corn was eclipsed by chocolate as the preferred Halloween treat. By the twenty-first century Halloween surpassed all other holidays—including Easter and Valentine’s Day—in chocolate sales, with annual revenues in the billions. See valentine’s day. Candy and cookie manufacturers now release products especially for Halloween each year. In 2012, for example, Oreo cookies made headlines with a special Halloween candy corn–flavored and colored version of the sandwich cookie in a “limited edition.” See oreos.

Halloween treats started to come under fire in the 1960s, as the urban myth of the razor blade in the apple spread. In 1974 a Texan named Ronald Clark O’Bryan earned the nickname “The Candyman” for poisoning his eight-year-old son Timothy with a cyanide-laced “Pixy Stix,” a long straw usually filled with innocent dextrose and citric acid. O’Bryan’s crime led to the notion of the anonymous poisoner of Halloween candy. Even though this myth had virtually no basis in fact, parents began to clamp down on trick or treat, while hospitals initiated programs to X-ray children’s trick-or-treat bags. However, trick or treat proved to be too beloved a ritual to die, and it is now celebrated in areas of Europe and Japan as well.

Dia de los Muertos

In Mexico and Central America—where Catholic holidays combined with Aztec and Mayan traditions instead of Celtic—Halloween is seldom observed. Instead, Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead), a festival that combines commemoration of the dead with skull imagery, is celebrated on 2 November (although the festivities may begin on 31 October). The small sugar skull, made from a process known as alfeñique (in which items are molded from sugar paste), has become the primary symbol of Dia de los Muertos, although the skulls (which may be decorated with sequins and other inedible objects) are seldom consumed. Pan de muerto, or “bread of the dead,” is a simple sweet bread (sometimes anise seed is added), which may be baked in the shape of bones or even a corpse, and is eaten as part of the festival, often at the graveside of a loved one. See day of the dead.

See also anthropomorphic and zoomorphic sweets; breads, sweet; and children’s candy.

halvah means “sweetmeat” in Arabic, and diverse preparations throughout the eastern Mediterranean share this generic name. In Lebanon and Syria, in Israel and Jewish communities all over the world, and in Greece and the Balkans, halvah generally refers to a tahini-based sweet (also known as halva, helva, halwa, or halawa).

Halvah is first mentioned in the thirteenth-century Arabic Kitāb al-Ṭabīkh (The Book of Dishes), where halwā yabisā (dry sweetmeat) describes a sugar candy with almonds and sesame or poppy seeds, flavored with saffron and cinnamon. It appears to be similar to the sesame and honey candy called pasteli in Greek, a different type of confection. See greece and cyprus. In his seventeenth-century Seyahatname (Book of Travels), Evliya Çelebi, the famous Ottoman chronicler of the eastern Mediterranean, mentions tahin helvāsi or tahine. He describes the street vendors of halvah in Istanbul, praises the quality of halvah in Bursa, and writes that Konya’s most revered sweet was halvah. See turkey.

Sesame halvah is a combination of tahini paste and natef, an intriguing, sweet Arab dip made by boiling the root of soapwort (Saponaria officinalis) in water, then whipping the brown broth until it becomes white foam—an amazing transformation made possible by the presence of saponin in the root. The white foam is then mixed with thick sugar syrup, and tahini is added to make the halvah. The mixture is churned and beaten in a special machine, after which the resulting hard mass is transferred to a large bowl or trough in which strong young men knead it by hand. The somewhat irregular, fibrous texture of this coveted hand-kneaded halvah—still made in family workshops in Greece, Turkey, and the Middle East—distinguishes it from mechanically produced factory halvah with its compact, uniform texture.

It is unclear how and when halvah was adopted by the Polish Ashkenazi community and sold in Jewish dairy stores. Eastern European immigrants introduced halvah to the United States, and in 1907 Nathan Radutzky, a Jew from Kiev, became the first to produce halvah on New York’s Lower East Side. His family continues to be the leading manufacturer of halvah in the United States. Now that modern chefs have rediscovered this ancient sweet, small producers have begun making organic, “gourmet” halvah spreads.

In Greece, tahini halvah is a very popular sweet, especially eaten during Lent. It is often called halvas tou bakali (the grocer’s halvah) to distinguish it from homemade confections.

Flour, semolina, or cornstarch constitutes the main ingredient in a different kind of halvah that is popular in Iran, Turkey, Greece, and the Persian Gulf. To make this rich style of halvah, the starch is sautéed in butter and then moistened with sugar or honey syrup to make a soft, buttery sweet, one that can be traced back to medieval times. Al-Warrāq’s tenth-century Baghdadi cookbook describes the cooking process and gives instructions for making date, apple, and carrot halvah—dishes later brought to India by the Mughals. See india. Turabi Efendi’s 1862 Turkish Cookery Book lists several of these so-called helvāssi. Some are made with wheat starch, whereas the recipe for irimik helvāssi calls for tiny pearls of sago, “small as gunpowder.” Unlike tahin helvāsi, considered a poor person’s sweet, these soft halvahs are often moistened with syrup mixed with milk and enriched with almonds, pine nuts, pistachios, and other nuts. This type of halvah is occasionally shaped with spoons, like quenelles, but more often it is transferred to molds, or spread on a pan, and left to set before being cut into squares or diamonds and served at room temperature. Halvas simigdalenios (semolina halvah) is the Greek version, for which semolina is toasted in olive oil instead of butter. There is also an old, frugal Greek version of olive oil halvah that uses chickpea flour instead of semolina.

See also middle east and north africa.

hamantaschen are triangular cookies filled with prunes, poppy seeds, jam, or even chocolate chips. These cookies are served at Purim, the holiday celebrating the Jewish people’s deliverance from serious danger in the remote past. The word likely derives from the German Mohntaschen, poppy seed pastries, though some ascribe its origin to a combination of Homen—the Yiddish name for Haman, chief minister of the biblical Persian king Ahasuerus and enemy of the Jews (Esther 3:7)—and tash (pocket or bag) from the Middle High German tasche. Although in Israel these pocket pastries are called oznei Haman (Haman’s ears), elsewhere the cookie’s three corners are said to represent Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—the three patriarchs whose merit saved the Jews. Hamantaschen have also been said to represent the wicked minister Haman’s hat. In any case, eating these cookies symbolically commemorates Esther’s cunning in saving the Jews from Haman’s proposed annihilation in fifth-century b.c.e. Persia.

Sometimes made with yeast and sometimes from a short butter crust, hamantaschen are a relatively new addition to the global Jewish gastronomic scene, although similar filled pastries, like the Mohntaschen, were known in medieval Germany and Central Europe. One of the earliest American recipes for Mohn Maultaschen (poppy seed tartlets) may be found in “Aunt Babette’s” Cookbook: Foreign and Domestic Receipts for the Household, published in Cincinnati in 1889 by the publishing company of Edward H. Bloch, a leader in the Reform Jewish movement. It calls for a filling of ground poppy seed, egg yolks, sugar, lemon peel, and crushed almonds both bitter and sweet, with raisins, citron, and rosewater as optional additions. Stiffly beaten egg whites are folded into this mixture, which is used to fill squares of puff pastry that are then shaped into triangles and baked in a hot oven.

Nineteenth-century cookbooks often give recipes for preferred Purim treats, such as the Purim Fritters (also called Queen Esther’s Toast but known today as French Toast) in Jennie June’s American Cookery Book (published by the American News Company in 1866), or Purim Puffs, basically a doughnut, in The 20th Century Cookbook (published in 1897 by C. F. Moritz and Adelle Kahn). At the beginning of the twentieth century in America, hamantaschen with a short dough became extremely popular, even among non-Jews. Traditional fillings included poppy seed or a thick purée of prunes or apricots called lekvar, a type of fruit butter. Today, Nutella, chocolate chips, lemon curd, and even Biscoff cookie spread are frequently used. See nutella.

In the seasonal cycle of Jewish holidays, Purim’s gastronomic position is quite important. Because it is the last festival before Passover, Purim is an occasion to use up all the previous year’s flour. Hamantaschen, along with other sweets and fruit, are prepared and sent as gifts, called shalach manot, to neighbors, the poor, and the elderly. During the rest of the year, hamantaschen are often displayed with other pastries in Jewish bakery windows from Brooklyn to Paris.

See also judaism; passover; and poppy seed.

See turnovers.

Hanukkah, also Hanukah, Chanukah, or Chanukkah, is the Festival of Lights celebrating the Maccabean victory over the Seleucids in 164 b.c.e. Arriving at the Temple to cleanse and rededicate it, the Maccabees found only enough sacred oil to light the menorah, the candelabrum, for one day. But a miracle occurred, and one day’s supply lasted for eight. Therefore, for each of the eight nights of Hanukkah, an additional candle is inserted into the menorah, from right to left. The candles are lit by a shammas (or helper candle), from left to right, until on the final night an eight-candled menorah is aglow. After the candle ceremony, it is traditional to sing songs, play with a dreidel (spinning top), open presents, and eat latkes (fried potato pancakes) as well as other fried foods, including desserts fried in or made with oil. For example, Persian Jews eat zelebi, a snail-shaped, deep-fried sweet. See zalabiya. Jews in Latin America eat buñuelos, fried pastries introduced by Spanish settlers who likely learned to make them from Iberian Muslims.

Cheese-based dishes such as kugel and cheesecake are also eaten during Hanukkah to honor Judith’s slaying of Holofernes, a general who attempted to demolish the town of Bethulia, Israel, in the sixth century b.c.e. Judith, a beautiful widow, gave Holofernes wine and cheese, and once the general became drunk, she cut off his head. Emboldened, the Israelites defeated Holofernes’s terrified troops.

In Israel today, sufganiyot are the most popular Hanukkah treat. The word “sufganiyot” was a neologism for pastry, derived from the Talmudic sofgan or sfogga, meaning “spongy dough.” Sufganiyot are basically raised jelly doughnuts rolled in sugar, a recipe brought by Jewish Central European settlers in the early part of the twentieth century. In Europe doughnuts (Krapfen, pączki) had long been fried for a variety of holidays by Germans, Poles, and others. According to Gil Marks (2010), the jelly doughnut’s modern-day popularity dates from the 1920s when Histadrut, the Israeli labor federation, encouraged its compatriots to replace the homemade latkes (potato pancakes) popular among European immigrants with commercially produced sufganiyot. See doughnuts.

No matter the ethnic origin of the baker, every bakery in Israel makes sufganiyot for Hanukkah. Today, they are sometimes filled with foie gras, sometimes with dulce de leche—anything goes in the contemporary Israeli kitchen. See dulce de leche. In that spirit, rugelach—crescent or half-moon-shaped cookies made from cream-cheese-enriched dough and commonly filled with apricot preserves or chocolate—are now also popular at Hanukkah, even though they are not prepared with oil. See rugelach.

See also doughnuts; fried dough; fritters; greece and cyprus; and pancakes.

hard candy is nearly as hard to define as it is to chew. In the United States, the term describes a wide variety of sweets, including drops, fruit lozenges, peppermints, lollipops, sour balls, candy sticks and canes, and rock candy. Familiar American brands like Life Savers, Necco Wafers, Tootsie Pops, Boston Baked Beans, Red Hots, and Lemonheads use hard candy techniques—boiling sugar to the “crack” or “hard crack” stage—to create specialized tastes. See life savers; necco; and stages of sugar syrup. The British-English notion of “boiled sweets” shares some similarities with North American “hard candy”; meanwhile, the Scots refer to “hard boilings,” which include “soor plooms” (sourballs), “fizzy boilings” like sherbet lemons that explode as they dissolve in the mouth, and chalky, crumbly mints called “Berwick cockles” for their rounded shape ribbed with peppermint stripes. See sherbet powder.

Temperature is of primary importance in making clear candies like fruit drops. When a syrup of sugar and water is cooked to the hard crack stage (once called the “caramel height”) at the upper end of the temperature range for candy making, 275 to 338°F (135 to 170°C), the sugar syrup forms breakable threads. See caramels. Cooking to a high temperature decreases the amount of water in syrup, and sugar syrup containing less than 2 percent water is optimal for hard candy, as it creates a clear, hard mass when cooled. Confectioners have also long known that crystals or “grain” can be produced when sugar is boiled, especially when it is stirred, a practice important for lower-temperature syrups, in which grain helps the mixture to harden on cooling. This process of crystallization, known as “graining,” is desirable in certain confections, like fudge, but it is discouraged in clear hard candies made from high-temperature sugar syrups. See fudge.

The sucrose in sugar inverts to glucose and fructose when dissolved in water. See fructose and glucose. Doctoring—adding inverting and flavoring agents—is a technique to control this inversion. To help prevent the formation of crystals, corn syrup, which does not crystallize, is often added to the sugar solution at a ratio of less than 3 parts corn syrup to 2 parts sugar. See corn syrup. In pure, clear hard candy, tartaric acid or lemon may be added to enhance inversion and prevent graining or recrystallization. Acids prevent graining, while stirring induces graining. It is all about balance, which confectioners have perfected over centuries.

The boiled sugar syrup can be formed into shapes, poured into molds, pulled into rolls and cut, crystallized on a stick, or layered over a filling. Adding butter to the sugar syrup results in butterscotch; cooking at a slightly lower temperature with an even sugar and corn syrup ratio results in brittle; and adding flavorings results in mints or lemon drops. See brittle and butterscotch. Hard candies must be wrapped or stored airtight in a dry place; otherwise, moisture will cause them to turn sticky or grainy, rather than retaining their smooth, glistening property.

Early accounts from China describe boiling barley and water to a hard consistency, then spinning it into sticks rolled in toasted sesame seeds. See barley sugar. Persian exports of boiled sugar lumps were known in Europe by the twelfth century, and soon came to be flavored with violets, cinnamon, or rosewater and even gold leaf in manus christi. From the Persian fanid came the English penid or pennet, flavored with peppermint or oil of wintergreen for smokers or for medicinal uses. With the discovery of techniques like panning, sugar syrup could be poured in layers to form a smooth, hard coating. See panning. Sugar syrup made hard shells for spices, nuts, or shards of lemon or orange peel to sweeten medieval comfits, the precursor of hard candies such as cinnamon Tic Tacs. Candied flowers and larger comfits called dragées also used this sugar-coating process; however, comfits and their modern descendants are not technically hard candies, since the sugar syrup is taken only a few degrees above boiling. North Americans might consider the modern British Gobstopper, or jawbreaker, to be the ultimate layering of sugar to form a hard candy—it is a hard, round ball with varicolored layers that are revealed as the ball is sucked.

Rose acid, colored with cochineal, was a popular boiled sweet on the streets of London. The sparkling, glass-like appearance of hard candy prompted the desire for more vivid color than could be obtained from the bodies of insects, leading in the 1830s to the dangerous addition of synthetic pigments from lead- and mercury-derived reds to the then-novel coal-tar dyes. See food colorings.

Because of a belief in the medicinal properties of sugar and the precision with which sugar syrup must be treated, hard candy was once the province of apothecaries, but with mechanization in the mid-nineteenth century came the potential for mass production of boiled sweets, and penny candy became available to the masses, especially children. See children’s candy and penny candy. By the early twentieth century, the perception of candy had come full circle from a valued and prescribed digestive to a craving that could lead to addiction. Thus, housewives were encouraged to make their own candy, not simply to avoid toxic dyes from coloring agents and the ink of the wrappers, but mainly to prevent moral dissolution from too much candy consumption.

See also candy; candied flowers; comfit; and medicinal uses of sugar.

Haribo, a candy manufacturer, is an extremely well-known German brand whose signature product is Gummi Bears. The company’s name is an acronym for Johann “Hans” Riegel Bonn. Riegel (1893–1945), a trained confectioner, started his own company from scratch in Bonn in 1920. He created the Gummi Bears in 1922, inspired by the costumed bears that were a featured attraction at fairs. In 1925 Riegel added licorice to his line of products, and the company’s wheel-shaped licorice candies became extremely popular.

Like many of his contemporaries, Riegel recognized the importance of advertising early on, and in the mid-1930s he came up with the advertising slogan still used today: “Haribo macht Kinder froh” (Haribo makes children happy). Upon Riegel’s death, his sons Hans (1923–2013) and Paul (1926–2009) took over, and Haribo thrived, with 1,000 employees in 1950. The company’s dancing bears were renamed Goldbären (gold bears) in 1960 and trademarked in 1967; today, they are sold in 116 countries. The first TV ads appeared in 1962, and soon thereafter the phrase “und Erwachsene ebenso” (and grown-ups too) was added to the company’s slogan to broaden its consumer base (in English-speaking countries, the slogan reads “Kids and Grown-Ups Love It So, the Happy World of Haribo”).

Today, Haribo has expanded, with over 6,000 employees. In addition to its classic fruit gums and licorice and chewy candy varieties, the company releases a constant stream of new products to appeal to current tastes. Haribo has been the subject of controversies surrounding management succession, forced labor during World War II (which the company has denied), and the naming of some licorice products with the term Neger (Negro). In 1993 Negergeld (Negro money) was renamed Lakritztaler, licorice coins. See licorice.

See also anthropomorphic and zoomorphic sweets; candy; and gummies.

Havemeyer, Henry Osborne (1847–1907), was to sugar what his contemporary John D. Rockefeller was to oil. Havemeyer masterminded the creation of the so-called Sugar Trust in 1887, after organizing the merger of a dozen and a half refineries in several cities. See sugar trust. Legal challenges began almost at once and continued past his death. Yet the American Sugar Refining Company—its official name—achieved a near-perfect monopoly, at one point controlling 98 percent of the country’s sugar market. See american sugar refining company.

Harry Havemeyer was born into a New York City family that had been in the sugar business for two generations. His paternal grandfather and a great uncle were German immigrants who apprenticed in London, then got jobs at a refinery in Lower Manhattan. In 1807 the brothers opened their own refinery, W. & F. C. Havemeyer, in a small building west of present-day SoHo. In 1856 Harry’s father Frederick Christian Havemeyer Jr., with a cousin and a partner, took the business into the modern age by building a colossal, technologically advanced refinery in what is now the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn. Havemeyers & Elder employed several thousand workers and could produce 5 million pounds of sugar daily. It was Harry, though, who turned this enterprise into a sugar kingdom. In an often quoted letter, Harry’s father wrote unambiguously to Harry’s older brother, Theodore: “Get it down as a fact, that Harry is King of the sugar market.”

Notorious for his abrasive personality, the stout, balding, white-mustached Harry became a favorite subject of caricaturists as he manipulated railroads to get preferential rates, granted rebates to wholesale grocers in exchange for selling only his sugar, and engaged in other questionable or illegal business practices designed to subdue competitors and discourage new entrants into the field.

Havemeyer’s company primarily refined cane sugar, but he made substantial inroads into beet sugar refining as well. See sugarcane; sugar beet; sugar refineries; and sugar refining. Seeking to control his supply of raw materials, he invested in raw sugar sources, particularly in the plantations of the Caribbean. See plantations, sugar. He also diversified horizontally, owning such things as cooperages for making sugar barrels.

Claus Spreckels, who refined Hawaiian sugar in California, was just one of many formidable rivals who eventually capitulated and joined the Sugar Trust. The Arbuckle Brothers were among the few who did not. These coffee roasters, as big in their realm as Harry was in his, patented a novel machine that packed coffee into paper bags. When they decided to use the machine for packing sugar, Harry retaliated by getting into coffee himself. Legendary price wars ensued, ending only after both companies had sustained enormous losses.

Harry married twice, each time to a member of the sugar-refining Elder family. After his divorce from Mary Louise Elder, her niece Louisine Waldron Elder became his wife. With Louise, Harry had three children and built a celebrated collection of European art, mostly Impressionist, which he pursued as aggressively as he had his sugar kingdom. (Many of his acquisitions hang in New York City’s Metropolitan Museum.) A fellow robber baron of the period, Charles L. Freer, said of Harry’s love of art: “No one can be more deeply touched by beauty than he, provided he is in a mood to enjoy it.”

Hermé, Pierre (1961–), has, since the late 1990s, been the most internationally renowned patissier of the grand French tradition and its greatest contemporary innovator. Jeffrey Steingarten dubbed him the “Picasso of Pastry” in Vogue magazine.

A fourth-generation pastry maker, Hermé left his native Alsace for Paris after the celebrated patissier Gaston Lenôtre (1920–2009) noticed him there before Hermé had even turned fourteen. Just five years later, Lenôtre entrusted a high-profile boutique to his wunderkind apprentice.

After military service and a stint at the Belgian chocolate firm Wittamer, Hermé returned to Paris, at the age of twenty-four, to take the helm at the pastry kitchens of Fauchon. There, he took inspiration from Paris’s couturiers and began to debut his latest pastry creations in themed, seasonal collections—a practice that he has continued ever since. In 1994 Hermé released the first of his many books, Secrets gourmands (written in collaboration with Martine Gérardin), which won France’s highest cookbook award and brought him national attention.

Three years later, Paris’s oldest tearoom-cum-pastry-shop, Ladurée, featured Hermé in its new, marble-lined pastry palace on the Champs Élysées. Behind the scenes, he took charge of revamping the shop’s classic macarons. See macarons. Within a year he was not only declared France’s top pastry chef but was also the first in his profession to garner decoration as a Chevalier of Arts and Letters.

The Ladurée collaboration was short-lived, however. Accounts differ about whether it was the passionate artist and perfectionist or the bottom-line business types who initiated the break. But in 1998 Hermé launched the patisserie Pierre Hermé Paris in Tokyo. His debut in Japan was purportedly the result of contractual restraints imposed by Ladurée against his opening a rival business in France. However, the choice acknowledged and has subsequently fed the enormous Japanese appetite for traditional French pastry making.

After Hermé opened his first Parisian shop in 2001 on the rue Bonaparte and Ladurée opened one of its main outposts down the street in 2002, the macaron wars began. Parisians argued over which to buy, although, in essence, Pierre Hermé lay behind both versions. Traditionalists shop at Ladurée for classic flavors such as pistachio and rosewater, while the avant-garde go to Hermé for experimental tastes such as Szechuan pepper.

Hermé’s innovations in French pastry making go far beyond the macaron’s revival. His creative choice of ingredients includes using sugar as one would utilize salt. Conversely, he was the first to feature fleur de sel as one might showcase sugar. He makes liberal use of black pepper and other spices. He has also reinvented many classic recipes. For example, he makes pâté feuilletée by placing the butter outside of the flour mixture, although this dough is traditionally made the other way around.

His most famous signature dessert, the Isaphon, exemplifies his unique style of synthesizing classicism and innovation. It features a rose-flavored macaron, the size of an individual tart, which is filled with a litchi-infused rose cream and has a supporting rim of raspberries. A single rose petal, a raspberry, and a white-chocolate logo crown its top.

Hermé has retained an impeccable reputation for artistry, passion, and quality despite the global expansion of his brand.

Hershey, Milton S. (1857–1945), opened his own candy business after working as an apprentice in the shop of Joseph H. Royer, a confectioner in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Hershey’s first business, which sold taffy, nuts, and ice cream, opened in 1876 in Philadelphia. But it only lasted six years, owing in part to Milton’s father’s poor business acumen. After the shop failed, Milton followed his father out west to find his fortune mining silver in Denver, Colorado, an ill-conceived pursuit. But this adventure gave him his first break: in Denver he discovered a recipe for caramel that was superior to any he had ever tried. He brought that recipe back east and, after several more failed attempts, eventually succeeded with his Lancaster Caramel Company, which by 1890 made Milton Hershey wealthier than he had ever dreamed possible. The company grew to employ more than 1,500 workers in four factories, producing hundreds of varieties of caramels. But Milton Hershey wasn’t satisfied. Business didn’t excite him; invention did.

With their newfound wealth, Milton and his wife Kitty traveled the world, and in the course of their travels Milton tasted a new confection, milk chocolate, recently developed in Europe. At the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Milton saw a tiny display of chocolate-making equipment from Dresden, Germany. The smell of roasting cacao beans caught his attention, and he announced immediately that chocolate would overtake caramels as the candy of choice. He bought the equipment right then and began experimenting. At first he made simple chocolate coatings for his caramels. Although European chocolate makers kept their methods of mixing milk and chocolate closely guarded, Milton eventually developed his own techniques for mellowing the chocolate—and reducing its cost—by adding milk.

Hershey believed that chocolate was as nutritious as meat, and he lauded its healthful properties. Convinced of chocolate’s appeal, he sold the caramel business in 1900 and invested everything in a chocolate factory in the midst of cornfields in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. He then set out to build a community—Hershey, Pennsylvania—that would be as wholesome as his chocolates. This was not the same kind of company town as DuPont’s Wilmington, Delaware, or Deere & Co.’s Moline, Illinois. Milton Hershey told everyone, “I’m not out to make money. I have all that I need.” He gave his workers insurance and retirement benefits, supported the local churches, and spared no expense on amenities for the community, including a theater, gymnasium, sports arena, public transportation, swimming pools, and a public school system.

Milton Hershey christened the town’s main thoroughfares Chocolate and Cocoa Avenues. By 1911 the Chocolate Camelot that seemed as if it had sprouted overnight from the Pennsylvania farmland was the talk of the state. Milton Hershey was hailed as a visionary and his factory was humming, employing 1,200 workers and churning out $5 million worth of chocolate products annually, including iconic brands like Hershey’s Milk Chocolate Bar (the Hershey Bar), Hershey’s Milk Chocolate with Almonds Bar, Kisses, and Mr. Goodbar.

Without children of their own, Milton and Kitty established the Milton Hershey School for orphaned boys, and in 1918 Milton donated his entire interest in the company, worth $60 million, to the Hershey Trust for the benefit of the school. The trust, which still owns a controlling interest in the chocolate company, is now worth more than $8 billion, and the school has an enrollment of more than 1,800 disadvantaged boys and girls. See also hershey’s; kisses; and reese’s pieces.

Hershey’s, synonymous in the United States with chocolate, is the maker of a candy bar that has greatly influenced the American palate with its high sugar content and slightly sour off-notes, a taste truly distinctive from European chocolate. Introduced in 1900, the plain milk chocolate candy bar is the invention of Milton S. Hershey, a visionary who believed so strongly in the health and nutrient value of chocolate that he sold his successful caramel business for $1 million at the turn of the century to finance a massive new chocolate factory amidst the dairy farms of western Pennsylvania. See hershey, milton s. Hershey taught himself the art of making milk chocolate—no easy task—and stumbled upon a method that allowed the lipase enzymes in the milk to break down the milk fat and produce “flavorful free fatty acids,” according to Hershey chemists who later analyzed the process. In other words, the evaporated milk that went into his candy bar recipe was slightly soured. This flavor became the hallmark of the Hershey brand when the milk chocolate bar was introduced coast to coast in 1906. The first milk-chocolate candy available to most Americans, it became an instant hit.

Milton Hershey added almonds to the Hershey Bar in 1908. The nuts displaced some of the more expensive milk chocolate, making it easier to hold the price of the bar to a nickel. Hershey’s automated, assembly-line factory, which cranked out bars by the millions, also provided a cost advantage, and he was often compared with Henry Ford, a man he greatly admired. Like Ford, Milton Hershey brought a luxury item to the masses. He introduced Kisses in 1907, Mr. Goodbar in 1925, Krackel in 1938, and with the purchase of the H. B. Reese factory just down the street in the early 1960s, Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups were added to the Hershey line. See kisses. The 1970s saw the addition of Rolo and Kit Kat, brands licensed from British candy maker Rowntree, and the introduction of a product very similar to M&M’s, a peanut-butter-filled candy called Reese’s Pieces that starred in the hit movie E.T. See m&m’s and reese’s pieces.

All these brands benefited greatly from Hershey’s now ubiquitous practice of placing candy bars in gas stations, newsstands, diners, markets, and everywhere a salesman could imagine. Previously, candy sales had been limited to druggists and confectionery shops, but Hershey’s aggressive approach paid off. By the 1920s the Hershey brand was cemented in the American psyche and the Hershey flavor ingrained in the memories of America’s youth, though it has never received global acceptance. Outside the United States, a Hershey Bar is typically viewed as “cheap” chocolate because it contains so little cocoa butter. However, Hershey remains an iconic American brand and a favorite of millions.

See also chocolate, post-columbian.

Hinduism, one of the world’s oldest religions, dates back more than 4,000 years. It is the faith of the majority of the people of India and also has adherents in other Asian countries, such as Nepal and Indonesia. From a relatively austere (though polytheistic) faith, as set out in the original texts of the four Vedas (approximately 1500 b.c.e.), Hinduism has evolved into a rich amalgamation of many local and regional beliefs and cultural practices. In folk idiom, the Hindu pantheon is often referred to as consisting of 33 million gods.

This protean vision is accompanied by a deeply intimate relationship between the individual and the divine, which is reflected in the attitudes and beliefs regarding food. The practice of animal sacrifice to placate the gods existed from ancient times, as can be seen in the texts of the Vedas and epics like the Ramayana (fourth to fifth century b.c.e.) and the Mahabharata (approximately fifth century b.c.e.). Over time, however, the rituals of worship, whether in the public domain of the temple or the private domain of the home, came to include the practice of offering a whole range of edible items, cooked and uncooked, to the gods. See temple sweets. The theory behind the practice was that offerings made with undiluted devotion and accompanied by the appropriate prayers and rituals were “accepted” by the deity, and this acceptance transformed ordinary food into something holy—prasad or sacred food. Subsequently, the human devotee could consume that prasad as a blessed gift from the god.

While sacrificing an animal like a goat or a buffalo is still occasionally carried out in certain areas, the vast range of food offered to the gods all over India is vegetarian. Some major temples, such as the Jagannatha Temple in Puri, Orissa, prepare daily meals consisting of rice and vegetable preparations cooked in a style that has remained unchanged for centuries. The food is offered to the temple deities five times daily by the priests and then distributed to the crowd of devotees. However, the most common items offered in worship, whether in the smaller temples, neighborhood shrines, or individual homes, are fresh fruits and sweets that can be homemade or store bought. In a tropical country like India, fruits are varied and available throughout the year and are immune from any taint of ritual impurity. Sometimes, the fruit can be transformed into a sweet. In Bengal, the birthday (in August/September) of the god Krishna, incarnated as a dairy farmer’s son, is celebrated with sweets made from the pulp of the ripe taal (fruit of the toddy palm) combined with rice flour, grated coconut, and sugar. The mixture is deep-fried to produce crisp yet luscious fritters. The baby Krishna, often pictured holding a naru (a round ball of coconut and sweetened evaporated milk) in his hand, is referred to as Narugopal.

The systematic cultivation of sugarcane and the extraction of sugar from its juice began thousands of years ago in India, with references found in some of the Vedas and later in the Ramayana. That probably contributed to the predominance of sweet items in religious worship. Throughout the country, a whole parade of sweets made with flour, rice, coconut, semolina, milk, and dal, expressing the culinary genius of different regions, became the food of the gods. The humblest offering, available to the poorest of devotees, is the batasha, a small, round, meringue-like confection of whipped sugar, white or brown. Batashas have the advantage of lasting long even in tropical humidity and can serve as a small daily offering in home worship. They also lend themselves to large-scale distribution among the crowd present at a religious event.

Perhaps the most iconic sweet offering, found throughout India, is payasam or payesh—rice cooked in milk. See payasam. Both ingredients have high symbolic value, rice as the life-sustaining staple and milk as the gift of the cow, an animal also considered sacred by Hindus. It should be noted that the payasam of India is not the same as the rice pudding of Western cuisine, since the latter usually contains eggs, which are nonvegetarian and, in ancient times, had strong associations of impurity. Other Western items, such as cookies, cakes, and pastries, which came to India in the wake of foreign colonization, are also excluded from the list of acceptable sweet offerings in Hindu worship because of the inclusion of eggs and their association with heathens.

Religious offerings have also been influenced by the Hindu philosophical tenet of three principal gunas (dominant traits)—sattva, rajas, and tamas—that characterize living creatures and earthly substances, including food. Each has distinctive attributes, and even gods are defined by the predominance of a specific attribute. For example, milk, evaporated milk (kheer or khoa), clarified butter, and rice, all of which are used to make sweets, are considered particularly suitable for the god Vishnu because he is associated with the sattva guna.

Hines, Duncan (1880–1959), is the namesake of one of the most well-known boxed cake mixes in the United States since the mid-twentieth century. Often considered alongside Sara Lee and Betty Crocker, Duncan Hines, unlike these brands, was neither an invented character nor a pseudonym, but the first national restaurant critic in American history. See betty crocker and sara lee. An energetic, extroverted traveling salesman, Hines retired from business in 1936 to self-publish a best-selling restaurant guidebook, Adventures in Good Eating. Soon elevated to the status of “authority on American food,” his persona became associated with notions of trust, honesty, and high standards in an era when middle-class diners traveling by automobile spurred the professionalization and expansion of the restaurant industry.

Due to his widespread, sterling reputation among consumers, Duncan Hines was often courted by food companies to sell their products. Despite his fear that endorsements would compromise his critical judgment, Hines eventually relented, forming Hines-Park Foods, Inc. in 1949 with a media executive, Roy Park. The Duncan Hines brand featured over 200 products, including canned produce, coffee, citrus juices, and salad dressings, as well as appliances, tableware, and even a credit-card service. At first, the best-selling item was Duncan Hines Ice Cream—no accident, for ice cream was Hines’s favorite food, which he ate three times a day, including breakfast. The cake mixes were developed by Nebraska Consolidated Milling. They were distinguished by the requirement that cooks add fresh eggs to the mix rather than supplemental liquids, as was then the industry standard. Duncan Hines cookbooks of sweets recipes also sold well, a tradition that has endured into the twenty-first century.

The success of the ice creams and cakes mixes was immediate and took a large market share from established brands like Pillsbury. As a consequence, Hines-Park Foods drew attention from larger companies. Seeking to capitalize on the mid-century boom in food processing, Procter & Gamble purchased the brand in 1956 and whittled its portfolio down to the cake mixes. After Hines’s death in 1959, his status as America’s popular food expert was eclipsed by the next cohort of tastemakers, notably Julia Child. Duncan Hines the person, a critic, became just Duncan Hines the product, cake mixes.

Under Procter & Gamble’s ownership, and then that of Aurora Foods and Pinnacle Foods, Hines baked goods have remained consistently popular. Although commercial fortunes can change at a whim, the future of Duncan Hines as an icon of American sweets appears to be strong. Dozens of cake flavors have been introduced, as well as mixes for brownies, muffins, and cookies, and frostings. With no face attached to the name Duncan Hines, the cake mixes have instead been associated with reliability, ease of use, and a sense of taste and texture that belies their industrial origin. The name has also taken on a nonculinary life of its own. By the twenty-first century “Duncan Hines” was such a part of many Americans’ experiences with baked goods that dozens of hip-hop rappers’ lyrics substitute his name for the word “cake,” which in urban slang means “money.”

See also cake mix.

hippocras, or hypocras, was a sweet, spiced medicinal wine familiar in late medieval and early modern Europe. To pharmacists, it was one of a class of “infusions” in which health-giving substances were combined with drinkable liquids: drinking hippocras was thus one of the more pleasant ways to improve one’s health. The term was first recorded in the fourteenth century, and vinum Hippocraticum (as it soon became known in Latin to physicians and pharmacists) was still being prescribed in the late eighteenth century, but it is merely the best-known example of a class of medicinal wines that existed long before and still exist today.

Hippocras changed over time with the availability and reputation of individual spices. See spices. The precise recipe might vary in any case: hippocras was made to order, often from a doctor’s prescription. Even the definition of “hippocras” was not fixed. In almost every source, the sweetener has to be sugar, more costly than honey (until the seventeenth century) and believed to be more health giving. The principal spice was usually cinnamon. Cloves and ginger were commonly included. Some sources say that the wine should be white—like the sugar—whereas others allow white or red as appropriate. Wines, like spices, varied in their medicinal effects. Hippocras was normally drunk cold; since the wine and nearly all the spices were (in terms of humoral theory) hot, adding further heat was not necessary or advisable.

Recipes are found in both cookery books and pharmaceutical manuals. This typical recipe dates from 1631:

Take 10 lb. best red or white wine, 1½ oz. cinnamon, 2 scruples cloves, 4 scruples each cardamom and grains of paradise, 3 drams ginger. Crush the spices coarsely and steep in the wine for 3 or 4 hours. Add 1½ lb. whitest sugar. Pass through the sleeve several times, and it is ready.

From the fifteenth to eighteenth century, hippocras was consistently defined by the fact that it is strained through a woolen or cotton bag called a “hippocras bag” or “Hippocrates’s sleeve.” Steeping followed by filtering was the best way to produce a crystal-clear, fresh-tasting wine that had absorbed the full flavor of the required spices. It is uncertain whether the bag was named after the wine or the wine after the bag: it is also not quite certain that the name derives from that of the “father of medicine,” the semi-legendary ancient Greek physician Hippocrates, although such is the usual view. Why the wine or the bag should be named after him is unknown. Despite widespread claims to the contrary, neither was invented by Hippocrates, who must have died about 1,700 years before the first recorded mention of either.

The procedure for making hippocras could be simplified by using a ready-made mix of ground spices. From the late-fourteenth-century household manual Le mesnagier de Paris, it seems that “spices for hippocras” were sold in this form by Parisian grocers.

Although the taste of good hippocras may resemble a sweet white vermouth, vermouth is not a hippocras by the usual definition, because its medicinal ingredients are herbs rather than spices. Ginger wine (though based on one spice rather than several) is a closer modern analog. The nearest ancient equivalent was the Roman conditum, a sweetened, flavored wine whose principal “active ingredients” were spices.

See also medicinal uses of sugar; mulled wine; and punch.

holiday sweets are central to the observance of secular and commemorative occasions in societies throughout the world. Although all holidays are at heart commemorative, recalling some significant religious or historical event, they tend to become self-commemorative as well, accruing new traditions that are connected only indirectly or not at all to the essential nature of the original event. This process encourages the development of increasingly local traditions. Another, related process is that of grafting, by which a holiday belonging to a newly adopted religion incorporates elements of older traditions. The spread of Christianity famously involved such cultural absorption: the Christmas tree resulted from the association of Christmas with northern European pagan practices. See christmas.

Inherent in holiday celebrations are opposing cultural tendencies of conservation and innovation. As commemorative events, holidays naturally encourage or even demand continuity of cultural practices through time, particularly in the realm of food. Long after certain dishes have disappeared from everyday life, they are prepared for special occasions, and thereby preserved. Furthermore, local ingredients and humble dishes maintain a central role in many holiday celebrations, especially those that are solemn in nature. Thus, sweetened wheat berries are frequently served at funerals and related commemorations of the dead (see the discussion of kolyva and pastiera below). See funerals and wheat berries.

At the same time, holidays are loci of innovation, into which the novel and exotic are naturally incorporated. This process involves not only unfamiliar ingredients but also dishes generally ascribed to differing socioeconomic realms, and in this way holiday foods serve to bind the various strata of society. Thus, on festive occasions, the middle class and poor tend as much as possible to surpass the limits of their usual diet and eat foods normally consumed only by the rich. For example, although in medieval Europe sugar and imported spices such as cinnamon, cloves, cardamom, nutmeg, and saffron were consumed with any frequency only by the rich, they gradually came to be featured in an ever-growing array of holiday dishes among the less well-to-do sectors of society.

Other key ingredients that marked sweet foods as celebratory were chocolate and highly refined wheat flour—as opposed to the less refined wheat flour and flours from other grains, such as rye, millet, barley, and oats, seldom found in holiday confections. See flour. Yet other, more common ingredients like butter and other fats, milk and cheese, and some nuts, which in premodern times were expensive for the nonelite, further augmented the extravagance of celebration. The historical value of the European sweet Christmas breads made with dough from refined wheat flour enriched with eggs, milk, and butter and seasoned with sugar, spices, and candied fruit, derived not just from the effort required for their preparation but from the actual value of all the ingredients. Examples include Italian panettone and pandolce, German stollen, Dutch kerststol, and Norwegian julekage.

Other holiday dishes are rendered more specific to a given occasion through some aspect of their preparation, especially their shape (such as the Easter lamb cake or dove-shaped Italian colomba pasquale; the log-shaped French Christmas cake bûche de Noël; or the Hot Cross bun with its cross-shaped marking) or their color (red for Valentine’s Day, red and green for Christmas, black and orange for Halloween, etc.). See easter; halloween; and valentine’s day.

An Archaic Family of Holiday Sweets

One old family of European dishes illustrates the role of symbolism in celebratory foods and highlights the development of pastiera, an elaborate and particularly rich dish that arose out of an older, very humble tradition.

In the Mediterranean world, preparations with whole grains developed symbolic religious significance in remote antiquity. In ancient Greece, they formed part of the ritual celebration of native divinities and were later grafted onto Christian observance, with the whole grains symbolizing the dual notion of death and resurrection. Various savory whole-grain dishes (generally combined with one or more legumes) persist to this day as celebratory foods in association with events of the Greek Orthodox calendar. The most notable is kolyva, a dish of boiled whole-wheat berries that, in numerous variations, is sweetened with honey or powdered sugar and fortified with crushed nuts, sesame seeds, and dried fruit. This dish is famously associated with funeral commemorations but is also consumed on various saints’ days, All Souls’ Day, and the first Saturday of Lent.

Within the Orthodox world, kolyva and its symbolic value were widely adopted beyond Greece for commemorative celebrations. The dish appears under the same name (in locally adapted forms) in the Balkans (Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania) and in the eastern Slavic lands (Ukraine, Belarus, Russia). A second but also ultimately Greek name for the dish, kutia (from the Greek koukìa, “kernels”), is also used in these Slavic lands as well as in Catholic Poland, where kutia is regionally featured in the traditional Christmas Eve meal. Interestingly, the dish also appears in various parts of southern Italy and Sicily—regions with deep historical connections to Greece—under the name cuccìa (from the Greek koukìa). In some places cuccìa is the name of savory wheat-berry preparations, but it is best known as a sweet concoction that includes nuts and candied fruits and nowadays also chocolate; the key ingredient is, however, fresh ricotta. In Sicily, sweet cuccìa with ricotta is eaten on Saint Lucy’s Day (13 December), which formerly coincided roughly with the winter solstice in the old (Julian) calendar, with the traditional Greek symbolic value of death and resurrection clearly at play.

A particularly interesting development out of this tradition in southern Italy is the most famous of Neapolitan holiday sweets, pastiera, a pie with a pasta frolla (short pastry) crust filled with sweetened ricotta fortified with egg yolks and flavored with candied fruit and orange blossom water. See candied fruit; cheese, fresh; flower waters; and pie dough. But what makes pastiera truly distinctive among ricotta-based pies is the de rigueur inclusion of cooked wheat berries; in this regard, the name for the dish in some Campanian dialects is telling: pizza cu’ gran, or “pie with grain.” Pastiera (attested as early as the seventeenth century) is made specifically for the Easter celebration. The ancient connection of a whole-grain sweet with death and resurrection clearly applies, but in this case it appears that the transfer from minor and more solemn occasions to the most important and joyous of Christian holidays occurred because of the complexity of the dish, both in terms of its preparation and expensive ingredients. The grain is necessarily still present, but here it becomes a complement to the enriched ricotta.

Other Noteworthy Families of Holiday Dishes

Fried Dough, Both Simple and Stuffed

Deep frying has always been a relatively expensive way to cook, but in the Mediterranean world, where olive oil and in some regions other vegetable oils were available, it has long been a feature of celebratory communal events, including holidays. Simple preparations of fried dough dressed with honey, syrup, or sugar are widely known from the Middle East to Spain, a culinary tradition that goes back as far as classical Greece and Rome; of similar antiquity are the analogs in Jewish and other Semitic cultures. Related preparations have also long been made for holidays across South and Southeast Asia. Indeed, this family of holiday sweets is one of the oldest and most widespread across the globe.

Beginning with some simple, nonfilled versions of fried dough (often quite soft and thus batter-like), the following examples can be noted:

Holiday preparations in which the fried dough is stuffed with a sweet filling include Italian zeppole (for the feast of Saint Joseph or for Carnival), Polish pączki (for Carnival), German Berliner or Pfannkuchen (for New Year’s Eve and Carnival), and Israeli sufganiyot (for Hanukkah).

Bread Puddings

Some old and ultimately elaborate holiday sweets developed out of the very humble European tradition of using stale bread as the basis for substantial everyday dishes, both savory and sweet (e.g., Danish ølsuppe, “beer soup”; German Schwarzbrot pudding, “black bread pudding”; and Silesian Mohnpielen, poppy seed dumplings). Of these, perhaps the most famous are the impressive English holiday puddings, such as plum pudding (Christmas) and figgy pudding (Christmas and Palm Sunday), which traditionally included breadcrumbs in their base. An elaborate sweet bread pudding strongly associated with the solemn occasion of Lent is the Mexican capirotada, an outlier of the Spanish family of (primarily savory) migas dishes. See pudding and southwest (u.s.).

Highly Spiced Christmas Cookies

The high cost of oriental spices in Medieval Europe rendered them especially appropriate for use in festive sweets, and a great many cookie-like sweets from the late medieval tradition feature centrally in Christmas celebrations. A few notable examples:

See also carnival; chinese new year; christianity; day of the dead; diwali; doughnuts; greece and cyprus; hanukkah; india; islam; italy; judaism; netherlands; passover; and ramadan.

honey, composed mainly of fructose and glucose, is essentially nectar concentrated by honeybees to around 18 percent moisture. Besides tasting sweeter than table sugar, the fructose in honey is especially soluble in water, helping to make honey hygroscopic, or able to absorb moisture from the air. See fructose. This quality means that honey is useful in baked goods as it keeps them from drying out. Honey also lends a lovely golden appearance and good flavor.

Honey was mankind’s earliest and most potent form of sweetness and remained so in the Western world until the plantation system of sugar production developed in the seventeenth century and the price of sugar fell. See plantations, sugar. Honey lost further ground as a sweetener when the process of extracting sugar from sugar beets was perfected in the early nineteenth century. See sugar beets.

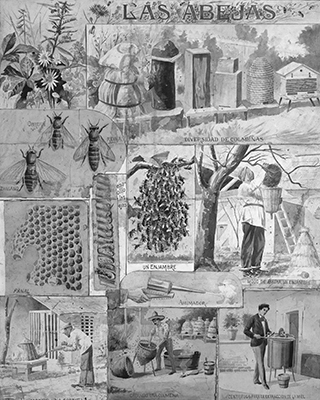

The first recorded beehives, shown on ancient Egyptian wall paintings, depict men removing honeycomb from cylindrical hives and packing it into jars. This French illustration, called “Bees,” dates to 1900. It was intended for publication in Mexico. musÉe national de l’education, rouen, france / archives charmet / bridgeman images

Prehistoric honey hunters risked multiple stings to track down wild bee nests in rock crevices and tree hollows, as indigenous peoples still do today in places such as Nepal, the Amazon, and Africa. Bees and honey are depicted in rock art dating back at least 26,000 years. Wall paintings and records from ancient Egypt show how honey was first used in sweet food. Triangular cakes and containers of honey are shown in Rekhmire’s tomb from around 1450 b.c.e. A Cairo museum has a honey cake from this era in the shape of a figure, like an early gingerbread man. See anthropomorphic and zoomorphic sweets and gingerbread.

Along with boiled-down grape must and dried fruits, honey was the main sweetener of food in ancient Greece and Rome. See ancient world; dried fruit; and grape must. Particular honeys were famous. Archestratus, a Sicilian poet and gourmet who traveled around the ancient Greek world, recommends that the flat cakes of Athens be eaten with Attic honey from the herb-scented hills around Athens. Cheesecakes, breads, and sweets all used honey, and it is included in many of the recipes attributed to Apicius, compiled around the fourth century c.e., not only in dishes and sauces but also to preserve fruits and other fresh foods. See cheesecake and fruit preserves.

Honey predated cultivated sugarcane in India and was part of the ritualistic drink soma during the Rigvedic period of around 1700–1100 b.c.e. Although the culture of sweets in India is largely founded on sugar, a mixture of curds, ghee, and honey known as madhuparka was used by Aryans to welcome guests. Early medicinal works mention a sweet called pupalika that was a cake with honey at its center. See india.

Medieval Persian and Arab cooks used honey alongside sugar in dishes such as halvah and baklava. It was such an important part of cooking in tenth-century Baghdad that one cookbook includes 10 different types. Honeyed foods were given to guests as part of the Arab tradition of hospitality. See baghdad; baklava; halvah; and persia.

The use of honey in pastries and other sweets spread westward with the Moors from the eighth century c.e., including the sweets made with nuts, honey, and egg white that are called turrón in Spain, turrone in Italy, and nougat in France. See nougat. Sicilian food shows a layer of Arab influence today in sweet dishes such as sfinci, deep-fried balls of dough drenched in honey. See fried dough.

Spiced honey gingerbreads, such as Lebkuchen and Leckerli, are a part of a long tradition in Central and Northern Europe. As they are today, these gingerbreads were elaborately decorated and molded into shapes such as the figures of saints, hearts, and pigs, or joined together into gingerbread houses. Stronger-tasting honeys from particular nectar sources, such as buckwheat honey, were favored for such recipes. Lebkuchen were first written about in Germany in 1320 when production was centered in monasteries, which often kept honeybees to produce wax for church candles; they were later made by bakers’ guilds. See guilds. Nuremberg, as a center for Bavarian honey production as well as for the spice trade, was a prominent location for this activity.

In the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, respectively, Europeans introduced honeybees (Apis mellifera) in North America and then Australia and New Zealand, where they thrived. In these regions, honey soon became a favorite ingredient in cooking as well as in baking, contributing flavor, shine, and sweetness to a wide variety of sweet and savory dishes. The American Bee Journal included honey recipes using honey beginning in 1876.

Symbolism

In Greek mythology, the infant Zeus was fed on honey, and in many cultures a ritual drop of honey was placed on the lips of infants, although today honey is not recommended for children under the age of one because of the risk of botulism. West Indians use a mixture of honey, oil, and spices called “Luck,” and in Upper Burma a muslin cloth dipped in honey is given to the baby.

According to Jewish tradition, a child dips a piece of apple in honey on his or her first day of school to symbolize the sweetness of knowledge, and honey cake is served on the Jewish New Year to wish good fortune for the year ahead. See rosh hashanah.

Honey has long been regarded as sacred. Offerings of honey cakes were made to the gods of ancient Egypt and Greece, and bees were seen as creatures that could fly between worlds. Honey is one of the five elixirs of immortality in Hinduism. See hinduism. The Old Testament describes the Promised Land as “flowing with milk and honey,” and honey in general symbolizes sweet delight, as in the “Song of Solomon”: “Your lips distil nectar, my bride; Honey and milk are under your tongue.” See christianity. More recently, Sicilian newlyweds have been given a loving spoonful of honey to share at the bridal feast.

The changing symbolism of honey and bees reflects the preoccupations of each era. The ancient Romans admired how a honeybee would bravely die for its colony, while the Victorians saw bees as moral creatures that would sting the sinful. In the industrial age, honey came to be regarded as a symbol of nature, sometimes representing a lost rural idyll, as in W. B. Yeats’ “bee-loud glade” in “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” (1890) or Rupert Brooke’s wartime poem “The Old Vicarage, Grantchester” (1916): “Stands the Church clock at ten to three? / And is there honey still for tea?” Other artists and writers use honey to convey a more vital essence of life. German artist Joseph Beuys compared hive honey to blood (both substances are around the same temperature) and used it in his 1977 installation Honey Pump at the Work Place, for which he pumped honey in transparent pipes around a museum full of people from across the globe discussing how to change the world.

In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, architects have also been inspired by honey and beehives. The parabolic arches used by the Spanish architect Gaudi (1852–1926) are thought to have been inspired by the way honeycomb hangs in the wild. In 1921 Mies van der Rohe entered a submission called “Honeycomb” in a competition for a high-rise building in Berlin that was a prototype skyscraper; Frank Lloyd Wright used the hexagonals found in the honeycomb in his buildings from the 1920s onward.

In recent years, concern about mass honeybee deaths, including the phenomenon known as colony collapse disorder, has led to bees and honey being seen as an emblem of environmental vulnerability.

Honey and Health

Honey has been used for healing for at least 4,000 years. Many cultures in the ancient world used it in remedies for the skin, eyes, and ears, for wound treatment and gut health.

The first recorded prescription using honey is on a Sumerian clay tablet from around 2000 b.c.e. that recommends it be mixed with river dust, oil, and water; honey is also mentioned in Chinese literature from around this time. The ancient Egyptian Ebers papayrus (ca. 1550 b.c.e.) contains 147 prescriptions using honey, including formulas for ulcers and burns, and for skin conditions from scurvy, after circumcision, and to reduce inflammation.

The ancient Greek philosopher Democritus believed that moistening oneself inside with honey and outside with oil was a key to longevity, and followers of Pythagoras in the sixth century b.c.e. breakfasted on bread and honey for a disease-free life. The physician Hippocrates (ca. 450–377 b.c.e.) said that honey cleaned, softened, and healed ulcers and sores.

The Qurʾān states that God inspired bees to produce liquids of different colors that contain cures for man. Medieval Arab apothecaries used honey as well as sugar in preparations. Syrups could be sweetened with honey, and lohoch was a paste made of roots boiled up and mixed with honey and almond oil for throat and chest complaints. Honey continues to be used in pastilles and cough lozenges up to the present day.

Ayurvedic medicine specifies eight different kinds of honey to be used for healing, and doctors practicing this form of medicine still believe that the addition of honey makes a prescription work better, perhaps because the sugars it contains help burst the cell walls of the other bioactive ingredients so that they become more effective. The first book in English specifically about honey (and the only one until the twentieth century) was published in 1759 by a London apothecary, Sir John Hill, titled The Virtues of Honey in Preventing Many of the Worst Disorders.

While honey has continued to be used in folk and traditional medicines, especially in remote regions of Africa, Nepal, and Russia, it was largely dropped in the era of modern medicine and antibiotics. A 1976 editorial in Archives of Modern Medicine dismissed honey as “worthless but harmless.” Piqued by this statement, Peter Molan, a biochemist in New Zealand, unearthed references in more than 100 published scientific papers that suggested honey was, in fact, actively beneficial. Since then, apitherapy, or the medicinal uses of hive products including honey, has grown apace.

Laboratory tests show the antimicrobial effect of specific honeys. Darker-colored honeys such as New Zealand manuka and Australian jarrah honeys are among those proved to be the most potent. Honey wound dressings have been licensed for use in Britain and the United States, as wound-care specialists say honey kills bacteria without damaging the surrounding tissues. All honeys are antimicrobial because their sugars kill bacteria and fungi, and also because honey is acidic. In addition, an active enzyme in honey can catalyze a reaction that produces hydrogen peroxide, which has a strong antimicrobial effect. Honeys, especially those from particular nectar sources such as buckwheat, have phytochemicals such as flavanoids that may further enhance their ability to heal.

Honey Production

The first recorded beehives, shown on ancient Egyptian wall paintings, depict men removing honeycomb from cylindrical hives and packing it into jars. The men are holding smoking bowls before the hives, a trick still used today to make the bees less likely to sting.

Bee-men in the forests of central Europe made ownership marks beside wild bee nests in trees and created detachable doors that enabled them to raid the colonies more easily. Log hives were hung in the trees or set on the ground; such hives eventually became a form of folk art, carved into figures such as bears or humans.

Woven wicker beehives were covered in cloom, a mixture of cow dung and lime. These wicker hives were replaced by the domed, woven straw hive called a skep, from the old Norse skeppa (grain basket). In rainy places, skeps could be placed in shelters or placed in niches built into a wall, known as bee boles. But the problem with such methods was that the bees were often killed when the honeycomb was removed. The loss of their bees upset the beekeepers; the many clerical beekeepers were especially troubled by the deaths they caused. It was a clergyman who eventually solved the problem. On 30 October 1851, the Reverend Lorenzo Langstroth conceived the idea of the “bee-space,” a corridor around ⅜ of an inch wide that could be built between and around the honeycombs. This space was just enough for two bees to pass each other but not so big that they would start to build a comb to fill the gap. This invention allowed honey and brood comb to slide in and out of a moveable frame hive, enabling the beekeeper to remove the honey or inspect the bees without destroying the colony. Most commercial hives around the world now operate on this principle.

The other major advance for commercial honey production occurred in 1865 when Major Franz von Hruschka, an Austrian living near Venice, gave his son a piece of comb in a basket. As the boy swung the basket around his head, Hruschka noticed how the honey came out of the comb due to the centrifugal force, which became the prime method of honey extraction, replacing the earlier technique of squeezing honey from the comb.

Honey has been produced and exported for centuries. The major producers at present are China, India, Vietnam, Europe (particularly Germany, Hungary, and Bulgaria), Ukraine, the United States, Argentina, and Mexico. Honey is transported in large vats and blended by honey packers. Today, there is a greater emphasis on the organoleptic qualities of particular honeys, known as varietal or monofloral honeys, which are produced largely from specific nectar sources. Tupelo and sourwood honeys from the southern United States, avocado honey from Mexico and California, heather honey from the United Kingdom, wild thyme honey from Greece, chestnut honey from Spain and Italy, arbutus honey from Sardinia and Portugal, the butterscotch-like honeys of New Zealand such as rewarewa, the eucalyptus honeys of Australia, and leatherwood honey from Tasmania are just some of the kinds that are sought out by honey lovers. Honeydew honey, made from the sweet secretions of aphids feeding on tree sap, is another prized product, although its strong flavor is not to everyone’s taste. See insects.

Honey is graded according to various criteria, such as viscosity. In the United States, honey is described partly according to a range of colors on the Pfund scale, using the terms “water white,” “extra white,” “white,” “extra light amber,” “light amber,” “amber,” and “dark amber.” Chefs and home cooks regard high-quality honey as a gourmet food to be drizzled on top of sweet dishes or onto a piece of cheese. The lower-grade honey used by the food industry is sometimes known as “baking honey.” The most artisanal honey, sometimes called “raw,” may be left as it is or barely heated, to no higher than the temperature of the hive, in order to retain more of its nutrients and flavor, and simply strained to remove bees’ legs and wax. Commercial honey tends to be flash-heated and fine-filtered to keep it runny longer. Honey crystallizes at different rates according to its storage temperature and the composition of its sugars, with higher-fructose honeys such as acacia remaining liquid. Removing all particles and air bubbles from the honey slows down this crystallization process. Alternatively, a small amount of finely granulated honey can be stirred into honey to get a set or creamed texture of small, smooth crystals.