taffy is a category of chewy candy whose definition is somewhat elastic. What differentiates a taffy from a toffee from a caramel varies from country to country and even from maker to maker. See caramel and toffee. Two criteria are most consistently used to define taffy. One is the absence of dairy ingredients. Whereas toffee and caramel include milk or cream and/or butter, taffy is typically composed primarily of sugar, corn syrup, water, and a stabilizer of some kind, such as starch or gelatin (though, to confuse matters, that stabilizer might be a dairy product). The other, more salient distinguishing characteristic of taffy is the fact that once the ingredients have been combined and cooked, the resulting sweet, sticky mass is pulled repeatedly in order to incorporate air, producing a candy that is lighter in both color and texture, as well as soft and chewy. Taffy also comes with a wider array of ingredients added for flavor and color; popular varieties range from peppermint to chocolate, cherry, lemon and licorice, in assorted pastel shades.

Part of the confusion is etymological. The origins of the words “taffy” and “toffee” are murky. The latter word is a variant of the former, and there is evidence that the harder, richer, creamier sweet we now know as English-style toffee evolved out of a softer, pulled, sugar-and-molasses-based sweet much closer to what is now known in the United States as taffy. By the early nineteenth century in the British Isles, sugar was available to all social classes, and confections such as taffy were made at home. In Wales, where taffy is also called taffi, toffee, and cyflaith, there was the Christmas Eve tradition of the Noson Gyflaith (Toffee Evening), in which hot sugar syrup was poured onto a buttered surface, and guests with buttered hands took turns pulling the stuff to make a kind of taffy. In Cumberland, England, there are records of a winter pastime called a “taffy join,” in which youngsters would pull a mixture of butter, sugar, and treacle, playfully flicking each other with the pliable strands. Immigrants to the United States brought their taffy-making traditions with them, instituting the candy-making party known to Americans as the taffy pull.

By the late nineteenth century in the United States, taffy making had become a commercial enterprise as well. It was associated in particular with seaside resorts, where taffy pulls were a common boardwalk attraction, and taffy a popular vacation souvenir. See boardwalks. Sometime in the 1880s, the candy began to be marketed as “saltwater taffy.” There are a few competing origin stories. One centers on an Atlantic City, New Jersey, shop owned by John Ross Edmiston. One stormy night, so the story goes, the tide washed over the shop, drenching it and its stock of taffy with seawater. Finding that the taffy was still edible, Edmiston, it is said, spun the event into a bit of marketing magic, thereafter labeling his product saltwater taffy. Other accounts maintain that the alleged baptism of the taffy in saltwater was mythical and, in fact, various sellers—notable among them Atlantic City’s Joseph Fralinger and Enoch James—simply liked the sound of the name and its association with seaside pleasures, and began using it to sell their taffy around the same time. In the early 1920s, Edmiston obtained a trademark for the name “saltwater taffy,” but he lost a lawsuit brought by his competitors, with the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that saltwater taffy “is born of the ocean and summer resorts and other ingredients that are the common property of all men everywhere.” In a 2013 survey of 2,000 adults from all 50 states conducted by the online retailer Candy Crate, one-fourth of respondents named saltwater taffy as their favorite summertime candy. To this day, no seawater is used in the making of saltwater taffy; it differs from other taffies in name only.

Over the course of the twentieth century, many new taffy products entered the U.S. candy market, including Mary Jane, rectangles of peanut butter-filled molasses taffy; Bit-O-Honey, honey-flavored taffy flecked with bits of toasted almond; Abba-Zaba, a taffy candy bar with a peanut butter center; Tangy Taffy, long, fruit-flavored slabs; and Laffy Taffy, originally sold as squares of fruity taffy in wrappers printed with jokes, and later repackaged under the Nestlé company’s Wonka brand as long, narrow bars. Though chocolate candies currently dominate the U.S. market, chewy candies claim more than 39 percent market share among non-chocolate confectionery sales. Candy companies continue to create new taffy products. Recent innovations include Wazoo, a taffy bar with a creamy, tangy coating covered in sprinkles, launched in Blue Razz and Wild Berriez flavors by the Topps Company in 2009, and Juicy Drop Taffy, individual pieces of taffy that come in a pouch along with an applicator filled with sour gel, debuted by Bazooka Candy Brands in 2012.

Still, nostalgia remains a powerful selling point among taffy consumers. In 2010, Bonomo Turkish Taffy, a beloved brand launched in Coney Island in 1912 but discontinued in the 1980s, returned to the market. The relaunch came thanks to the efforts of Kenneth Wiesen and Jerry Sweeney, two diehard fans who acquired the intellectual property rights in 2002 and embarked on a years-long quest to resurrect the original formula, tracking down former Bonomo cooks, building specialty equipment, and finally debuting at the National Confectionery Association Sweets and Snack Show in Chicago. Today, Bonomo Turkish Taffy is made in York, Pennsylvania, and packaged with the vintage Bonomo logo and directive to “Smack It, Crack It!” on the wrapper—a testament to the candy’s enduring appeal.

See also candy; children’s candy; corn syrup; gelatin; and starch.

tapioca is a starch extracted from the cassava root (Manihot esculenta). It is used as a thickener and to make puddings and other sweets. Tapioca “pearls” are obtained by heating the moist starch that remains in the water after cassava roots have been washed and pressed to produce flour. The pearls can be heated a second time to pop like corn, or they can be rolled into different sizes. See cassava.

In the sixteenth century tapioca spread from Brazil to Africa, the Philippines, and throughout Southeast Asia, but it was introduced into Europe as a commercial instant thickener only in the mid-nineteenth century. Professional and household kitchens alike soon adopted this novelty food item, which allowed cooks to make custards without eggs. In 1854 Henriette Davidis, Germany’s most important cookbook writer, published a recipe for tapioca for invalids in her Praktisches Kochbuch (Practical Cookbook). Europeans considered tapioca a light, easily digestible food, although the sticky pudding resulting from boiling its grains with sugar, milk, and a pinch of cinnamon owed its soothing effect more to the ingestion of the sweetened carbohydrates than to any medical virtue.

In Latin American and in Asia, tapioca mixed with sugar remains a luxurious dessert. It may be combined with coconut, spices, and eggs to make cakes, ice creams, and puddings, which are often covered with golden caramel. There is also a traditional Brazilian dessert—sagu—made with pearl tapioca cooked in red wine. In Asia, tapioca is also transformed into colorful jellies, flavored with pandan (Pandanus amaryllifolius) and tossed with grated coconut. See pandanus.

See also brazil; bubble tea; and pudding.

tart in its sweet version is a subset of the sweet pie. The Anglo-American tart can be traced to late medieval European innovations in pie pastry formulations, which made the crust tender through the addition of fat. In contrast to the tough, leak-proof flour and water crusts that dominated pie cookery at the time, these softer crusts were enticingly bitable and chewable. See pie and pie dough. They encouraged pies in which the diner simultaneously took in filling and crust to create complex combinations of taste and texture in the mouth.

Tart entered written English from France around the cusp of the fifteenth century; the British dropped the “e” from la tarte and, as is common when dishes cross borders, modified the concept to fit their own cultural preferences. What differentiates sweet tarts from pies in the British tradition is not ingredients or the placement of the filling in relation to the crust. It is the tart’s relative refinement, particularly its thinness. Gervase Markham, the author of The English Huswife (1615), the most important early-seventeenth-century British cookbook, explicitly specifies the depth of his pippin tart as 2.5 centimeters (approximately 1 inch), the height of manufactured tart pans today. In addition to providing a closer balance between filling and crust than is experienced with a pie, the tart’s thinness means that it satiates the eye and mouth more that it satisfies hunger. The tart is a dessert for the connoisseur, not the glutton; when hungry, you do not tuck into a slice of tart.

The sweet tart’s basic form is that of a disk approximately 9 inches in diameter and 1 inch high; the tart pan is often fluted. See pans. When baked freeform on a sheet with the edges of dough folded in toward the center, the tart is frequently referred to as a “rustic tart.” Today, in the Anglo-American tradition, tarts are usually completely open-faced, the form most closely associated with tarts in France. The open tart is sometimes ornamented with cross-hatching or pastry leaves or stars, radical simplifications of a previous tradition associated with high-status tables. Elaborate patterns in cut pastry characterized the pippin and pear tarts sketched by Robert May in his seminal cookbook The Accomplisht Cook (1685). However, until the late nineteenth century British fruit tarts tended to be covered, with a lightly glazed top; such glazed, covered tarts are now rare.

Fillings common to both tarts and pies include fruit purées, stewed fruits, and halved, quartered, or sliced fresh fruits. See fruit. The open tart’s halved fruits, because they cannot hide, are always the most perfect available. Physical perfection might not be required of halved fruits in closed tarts, but peak ripeness is assumed in all tarts, as a comparatively small amount of fruit must communicate the dessert’s character and clarity of flavor. The tart’s tender, thin crust also means that an open tart can be spread with nothing more than a little jam or pastry cream, as a layer of intense or clean flavor epitomizes the tart’s focus on the distillation of taste experience over quantity. As a dessert intended to be savored, tarts are often produced in individual serving sizes, a disk no more than a few inches in diameter. Small tarts may be referred to as “tartelettes.” Historically, small British pies were referred to as “tarts.”

Different tart traditions handle identical fruits differently. For example, in the French culinary tradition, apple and pear tarts are made with slices of precisely sliced fruits laid down in perfect circles and then glazed. In Anglo-centric culinary cultures, this style of tart is now often explicitly referred to as a French apple (or pear) tart. Conversely, the nineteenth-century French tourte tradition did not encompass fruit pies, so cookbooks such as Fouret’s Le cuisinier royale (1820) offered recipes for the English covered fruit tart under the name of Tourte à l’Anglaise, à la Bourgeoise.

While historically the British and early American tart was clearly defined as a closed, thin fruit pie, today many English-language dictionaries restrict “tart” to the French meaning of a thin, open pie. Based on cookbook language, the shift in taste from what can be thought of as the British tradition of closed tarts to the French open tart took place in the first decades of the nineteenth century, initially in the United States. While Susannah Carter’s Frugal Housewife (1803) specifies a lid for the apple tart, by 1830 Lydia Child’s American Frugal Housewife makes clear that her cranberry tart has “no upper crust.” Webster’s An American Dictionary of the English Language (1830), perhaps in its attempt to define an American as opposed to British lexicon, explicitly places tart fillings “on” the crust, rather than “in.”

In her best-selling mid-nineteenth-century British cookbook The Book of Household Management (1861), Mrs. Beeton indexes her strawberry tart as an “open tart,” which implies that, unmodified, the word “tart” was too ambiguous to use. See beeton, isabella. Beeton specifies the open tart as always appropriate for jam tarts and thus offers a period source for understanding the nature of the tarts that created such a ruckus in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland (1865). Mrs. Beeton’s apricot tart is covered, and as late as the 1880s, British cooks still readily conceived of tarts as either open or covered, as the Handbook of Domestic Cookery’s (1882) language makes clear: “Ice the covered tart, and send the open one without any addition to the table.” Nineteenth-century cookbooks were used well into the twentieth century, but eventually the long-standing British covered tart tradition died out in the face of expanding French culinary influence.

Given the easy accessibility the Internet offers to historic and international recipes, the Anglo-American tart may once again change its form, and the dictionaries their definitions of “tart” to keep up with changing cultural practice.

tarte Tatin is an upside-down apple tart made by putting butter and sugar in the bottom of a tin-lined copper pan, baking dish, or ordinary pie pan about two and a half inches deep, adding a layer of peeled and quartered (or sliced) apples, then adding more butter and sugar to the apple layer. The whole is covered by a layer of pastry—which can be short crust, sweet short crust, or puff pastry—and baked in a hot oven until the pastry is browned and the apples are deep golden and nicely caramelized. Julia Child points out that judging the right amount of caramelization is greatly aided by the use of a Pyrex baking dish. Once the tart is cooked, it is unmolded upside down so that the crust is on the bottom and the apples are on the top, a move that may take some practice.

Tarte Tatin is served with whipped cream or ice cream while still warm. It is a rustic dessert with origins in the French provinces. The name “Tatin” belonged to two sisters who ran an inn in the Orléanais village of Lamotte-Beuvron. Whether these women invented the upside-down tart, or simply wrote down the recipe for this regional specialty, their name is famously attached to one of the most beloved desserts in France.

See also pastry, puff and upside-down cake.

Tate & Lyle is well known around the world as a sugar refiner and manufacturer of sweeteners and other products. Tate & Lyle PLC is also one of the hundred largest companies in Britain. It dates from 1921, when the two biggest British refiners amalgamated, though their founders, Henry Tate and Abram Lyle, were by that time long dead. Indeed, they never met.

Henry Tate (1819–1899) began in sugar refining in 1859, originally in Liverpool. Abram Lyle (1820–1891) was from Greenock in Scotland, where he bought a refinery in 1865. Both companies also opened refineries in London. They refined imported raw cane sugar and, in later years, faced stiff competition from imports of beet sugar, many of which were subsidized, from Continental Europe, especially Germany. See sugar beet. When sugar prices collapsed in the early 1880s, the two companies responded by innovating and specializing. Lyle began to make Golden Syrup, using a secret formula, and this became the company’s most profitable product. See golden syrup. In 2006 it was recognized as the world’s oldest extant product brand. Tate invested in new production processes to improve efficiency, and he bought patents (from Germany in 1875 and Belgium in 1892) to make sugar cubes. Sugar had previously been sold in lumps or “loaves” which had to be broken, so small cubes were a major convenience. See sugar cube. While the two companies were competitors, they also made complementary products.

Tate & Lyle formed from the 1921 merger of the two biggest British sugar refiners, Henry Tate & Sons and Abram Lyle & Sons. Here, the company advertises various kinds of sugar in packets, although it was better known for sugar cubes and Golden Syrup. hip / art resource, n.y.

Henry Tate was a great, though discreet, benefactor, making donations to Liverpool University and other educational and medical institutions. He had been a keen collector of contemporary art, especially pre-Raphaelite paintings, and wished to donate the greater part of his collection of pictures and sculptures to the nation. To do so, he financed the construction of a new gallery at Millbank in London, opened in 1897, as the National Gallery of British Art; this museum has always been known as the Tate Gallery, after its founder.

The Tate & Lyle Company

Both businesses continued to be family run, and they overcame difficulties with supplies in World War I. By 1918 they together accounted for a third of British sugar production. Although competitors, the two companies chose to amalgamate in order to maintain their power in the market, and the government sanctioned the merger even though it gave the company such a dominant position. The new company extended operations by taking over a number of smaller producers in subsequent years. In 1923 Tate & Lyle accounted for half of the refined sugar in Britain; by 1938 business acquisitions meant that it controlled three-quarters of British refining capacity. The new company also took an interest in producing its own sugar for refining by investing in a beet sugar factory in 1925. In 1937, following the establishment of the British Sugar Corporation that had a monopoly in beet production, Tate & Lyle bought cane plantations in Jamaica and Trinidad. Thus, on the eve of World War II, the company had a virtual monopoly in refining and was a major supplier of raw cane sugar.

In the years following World War II, however, refining in Britain declined slightly and accounted for a falling share of Tate & Lyle’s profits. Production of raw sugar and refining abroad became more important, although the company also began to diversify into new products, including high-fructose corn syrup as a sweetener for drinks. See corn syrup. In 1950 the company began to make Black Treacle—a variant on Golden Syrup. Britain’s entry into the European Common Market in 1973 exposed the oversupply of sugar, and the company moved further into diversification with industrial materials and artificial sweeteners. See artificial sweeteners. In response to the growing demand for low-calorie sweeteners, in 1976 the company developed sucralose, which they marketed as Splenda in partnership with the American company MacNeil Nutritionals, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson. Unlike other synthetic sweeteners, Splenda has the great advantage of being not only a substitute table sweetener, but also being useful in manufacturing. This product has become the company’s most important.

Industrial products like Splenda, including some with no connection to the food industry, became so vital to the company that it began concentrating on producing goods as inputs for industrial processes rather than for retail consumption; for instance, MacNeil supplied Splenda to the retail market, while Tate & Lyle concentrated on industrial production. In 2010 Tate & Lyle PLC sold their sugar and syrup making interests to American Sugar Holdings. Under the name “Tate & Lyle Sugars,” the new company continues to be the largest cane sugar refiner in Europe, using only “Fair Trade” materials. So the name has remained, and the new company still produces the two products that made the founding companies famous: sugar cubes and Golden Syrup.

See also sugar; sugarcane; plantations, sugar; sugar refineries; and sugar refining.

tea is a beverage made from the dried leaves of the evergreen plant Camellia sinensis. From its legendary beginnings in China to the present day, it has become the second most popular drink in the world, after water, and is enjoyed by millions across the globe. The Chinese drink fragrant teas from delicate bowls, the Japanese whisk it, Tibetans churn it with butter, Russians serve it with lemon, and North Africans add mint. Indians boil tea with condensed milk, the British and Irish drink it strong with milk, while Americans prefer it iced. Tea is very often sweetened with sugar or honey.

There are six types, determined by the method of treating the leaves. White, yellow, and green teas are unfermented, oolong is semi-fermented, and black and puerh (compressed teas) are fermented. These types are all processed in different ways to produce a huge variety in the color and shape of the leaf, and in the flavor and aroma of the beverage.

When green tea first arrived in the West in the seventeenth century, it was expensive, and only the rich could afford to drink it. This tea was quite bitter and was often taken for medicinal purposes. Quite early on, sugar (which was by now a familiar ingredient) was added as a sweetener. Milk was sometimes added, but its use became widespread only with the introduction of black tea.

In Central Asia, along the Silk Road from China to Turkey, tea prepared fairly weak, steaming hot, and without milk is often served with plenty of sugar, especially for guests as a sign of hospitality: the more sugar, the more honor. It is sometimes the custom to serve something sweet with the tea, rather than sweetening the tea itself. Sugar lumps are sometimes placed on the tongue and the tea is drawn through them. See sugar cube. Sweets and sweetmeats such as sugared almonds are popular accompaniments; in Russia, jam is served in a little dish and eaten by the spoonful alternately with sips of tea. In Japan, delicate and beautiful small confections or sweetmeats called wagashi are served with green tea, especially during the Tea Ceremony, to offset the tea’s bitterness. See wagashi.

“Tea” can also mean a meal or a social occasion such as afternoon tea, which became fashionable in Britain in the nineteenth century. As the evening meal came to be served later, the hungry gap in the afternoon was filled by a light meal, at about 4 or 5 o’clock, of dainty savory or sweet items such as cucumber, jam, or honey sandwiches, cakes, pastries, or biscuits. Cream tea include cones with strawberry jam and cream.

During the nineteenth century the tradition of high tea was finding a place in lower- and middle-class homes, as the tax was reduced in 1784 and cheaper black tea was now being imported from India. Working-class families could now afford to drink tea as their main beverage (rather than gin or beer), and after work they welcomed a hearty meal at about 6 o’clock, served with a pot of black tea with milk and sugar. Hot dishes were eaten; sometimes there were cold meats and pies accompanied by bread, butter and jam, cakes, fruit loaves, and biscuits.

Tearooms sprang up in many cities of Britain and North America at the end of the nineteenth century. Ladies tired from shopping could enjoy a refreshing cup of tea with their friends and sustain themselves until dinner time with a slice of cake or sweet pastry. Here, two little girls have dressed up for their own tea party, circa 1909. library of congress

Meanwhile, in the United States, ladies were gathering in their parlors or on their verandas for “low tea” (so-called because the tea and cakes were served on low tables, in contrast to “high tea,” when a more substantial meal was eaten at a high dining table). Tea parties, with homemade specialties such as strawberry shortcake, pecan pie, or angel cake, were held to raise funds for churches or charities.

Tea rooms sprang up in many cities of Britain and North America at the end of the nineteenth century. Ladies tired from shopping could enjoy a refreshing cup of tea with their friends and sustain themselves until dinner time with a slice of cake or sweet pastry. Taking afternoon tea out has again become fashionable, especially in large hotels, where the fare is sumptuous and elegant. In France, salons de thé, which became popular in the early twentieth century, still thrive. See salons de thé. Exquisite gateaux, tarts, and biscuits such as macarons, palmiers, and madeleines are served. The French have devised new blends of teas flavored with fruits and spices, and have also developed a tea-based cuisine, including tea-scented jellies.

During the nineteenth century, British women in India adapted afternoon tea to local traditions. A typical Anglo-Indian afternoon tea would consist of sandwiches (often with spicy fillings), Indian savories such as pakora and samosas served with English cakes, kul kuls (a type of fried cake), or sweetmeats such as barfi. See india.

In Australia, where tea is still an important evening meal, teatime sweet specialties include lamingtons and Anzac biscuits. A pavlova might be served for special occasions. See pavlova.

Tea is also an important flavoring in food, especially in sweet dishes, and is becoming increasingly popular, partly because of the variety of teas available. The flavor of teas can be strikingly different depending on how the tea is produced. Japanese green teas, which are steamed, have grassy, seaweed flavors, while Chinese green teas, which are pan-fried, produce savory toasted flavors. Oolongs lend a floral or fruity taste; black teas are richer and stronger, sometimes adding a hint of bitterness. Flavoring with matcha (powdered green tea) not only gives a vibrant color, because of its high caffeine content it also adds a little kick. Teas scented with flowers, fruits, or aromatic oils are particularly good for flavoring sweet dishes.

temple sweets are confections offered to gods and goddesses at their temples’ altars throughout India. Food (cooked or raw) that is offered to the deities is called bhog. After the priest has presided over the gift-giving ceremony and presented the offering, the blessed food comes back to the devotees as prasad. This practice of sharing foods with the immortals has long been the central idea of communal kitchens in temple complexes. Hindu gods and goddesses are known for their sweet tooth and fondness for milk products. See hinduism. Lord Krishna in his childhood often stole butter, and his disciple in Bengal, Chaityana, shared his tastes, particularly when it came to kheer (milk pudding). Another Hindu god with a fondness for sweets is Lord Ganesha. Lord Ganesha, the elephant god, is renowned for his prodigious appetite for modaka and laddu. See laddu and modaka.

To facilitate such sweet encounters between devotees and the objects of their worship, special care is taken to maintain the purity of the food offered. Thus, temples sometimes hire cooks who are Brahmin (the priestly caste), or sometimes specially trained men are employed in the sacred ritual of preparing temple sweets. For instance, the Siddhivinayak Temple in central Mumbai, which is devoted to Ganesha, sells devotees mahaprasad (blessed food) of specially prepared laddus (here made with chhana dal, ghee, sugar, peanuts, and cardamom). The holy treats are made by 36 trained cooks in the sacred kitchen. Each location has its own rules regarding the preparation of sacred sweets offered and shared with devotees. At the Sikh Golden Temple (Harmandir Sahib) in Amritsar, for example, the person cooking the kadaprasad (a creamy grain-based dessert made with equal amounts of wheat flour, sugar, and ghee) in the holy site’s kitchens has to recite scriptures while preparing the sweet offering.

Perhaps the best known of the pilgrimage sites is the Jagannath Temple in Puri, Odisha. There, 500 cooks and 300 helpers prepare and offer the mahaprasad to Lord Jagannath six times a day, feeding around 100,000 devotees daily. Mainly the sweets are prepared from one of the following combinations: flour, ghee and sugar; rice or wheat flour, milk, and sugar; or sugar cooked with various forms of milk. Of all the sweets, khaja—an oval, layered, fried sweetmeat prepared from flour, sugar, and clarified butter—is perhaps the most popular item in mahaprasad parcels. It is just one of Odisha’s contributions to the map of the temple sweets of India.

Lastly, peda, a round sweet prepared from khoa (thickened milk), sugar, and a good dose of cardamom, is found in the Kashi Viswanath Temple in Benaras and the Baidyanath Temple in Deogarh. There is a dedicated lane in the temple town of Deogarh that goes by the name Peda Galli, with sweetshops selling this famous sweet.

Thailand, a nation in the Indochina peninsula in Southeast Asia, has a sweets culture that has evolved dramatically since its origins in the thirteenth century. Historically, Thai sweets were sacred and precious, reserved for divinity—monks and royalty. Today, sweets are abundant and accessible to people of all stations.

Origin of Thai Sweets

Centuries before the founding of the first Thai kingdom of Sukhothai, sometime in the thirteenth century, Thais migrated from southern China to Southeast Asia, where they settled among inhabitants of the Dvaravati and Angkor kingdoms. They embraced the Buddhism and Hinduism taught by Indian and Ceylon priests, adapting and assimilating new religious rituals into their traditional cultural beliefs and customs. See buddhism and hinduism.

Sweets were originally introduced as religious and ceremonial offerings. Since they were considered sacred foods, only celestial beings, including mortals with royal lineage and monks, were allowed to eat them.

Religious fables contain many stories of ancient Thai sweets. The earliest sources reveal that Thai sweets were named for the main ingredient, appearance, technique, or vessel used in their making. The first sweets were predominately Indian in origin and made from staples with religious significance, such as rice, coconut, beans, honey, seeds, and jaggery made from coconut sap, palm sap, or cane sugar, which would remain the staples used in the creation of Thai sweets for many centuries. See india and palm sugar. Cooking methods were limited to slow boiling, steaming, or grilling, because the early cooking wares were made from fragile terra cotta that could not handle high temperatures.

Rice was the ingredient held in the highest esteem. The Thai word for sweet is khanom, a combination of khao and nom, meaning “food with sweet taste.” Khao means “food or rice,” and nom, a Khmer word, implies “food made with rice flour.” Some historians interpret the word nom as milk or, in particular, rice milk or a milky batter made from milling rice grains and water together with a stone grinder. Most Thai sweets were made with nom.

However, ancient sweets made with whole-grain glutinous rice were not called khanom but were given names starting with khao (rice). Khao nieo daeng is a good example. Garnished with sesame seeds, it is made with cooked glutinous rice and a mixture of coconut cream and palm jaggery, which colors the rice red.

Another example illustrates an ingenious cooking method that uses leaves to wrap the ingredients. Khao tom phat, a mandatory sweet for alms and religious rituals, is made with partially cooked glutinous rice sweetened with coconut cream and palm jaggery, wrapped in banana leaves and stirred while boiling.

Sweets made with rice dough have names starting with khanom, such as khanom tom daeng (boiled red) and khanom tom khao (boiled white). Rice-dough sweets were presented as offerings to the Rice Goddess during rice planting and harvesting. Glutinous rice dough perfumed with flower-scented water and jaggery are shaped into small balls and boiled. A portion of each ball is dressed with grated coconut cooked with reddish jaggery, while the rest is coated with fresh grated coconut, salt, and sesame seeds.

Khanom bueng (terracotta tile) is a sweet named after the cooking vessel it resembles. A light batter of rice and mung bean flour, coconut cream, and jaggery is spread paper-thin over a heated flat terracotta pan. The result is small, round, sweet crisps resembling tiles.

Ayutthaya Kingdom (1351–1767)

Toward the latter period of the Ayutthaya Kingdom, Maria Guimard (or Maria Gimard, or Maria Guyomar de Pinha), a woman with Portuguese, Japanese, and Bengalese ancestry, is credited with inventing countless Thai sweets. She lived some time during the seventeenth century and inherited her skill from her mother’s Japanese Catholic family, who in turn had acquired most of their culinary experience from Catholic missionaries before fleeing Japan to escape religious persecution.

Guimard had a very dramatic life. Her Greek husband, a colorful advisor to King Narai (1656–1688), was executed for treason, landing her in jail, from which she escaped. She was recaptured, however, and subsequently became a slave in the royal kitchen. Cooking for two kings over several decades, she was eventually honored for her culinary contributions.

Guimard created egg-based desserts from Portuguese recipes by using refined sugar, a rare commodity that became available due to the demands of Europeans who preferred their tea sweetened. See portugal and portugal’s influence in asia. Metal cookware, available in the royal kitchen, enabled her to employ new cooking techniques, such as baking and glacé, the process of coating sweets with a sugary syrup. In addition, serving sweets as desserts, a foreign custom, was introduced to the royal table.

Guimard’s most famous confections are phoi thong (golden fluff, originally Portuguese fios de ovos), thong yip (pick-up gold), thong yod (gold droplets), and med khanun, which resembles jackfruit seed. These golden delicacies came to symbolize prosperity and auspicious blessings, and are presented as religious and ceremonial offerings to this day.

Guimard substituted coconut milk for cow’s milk to make Portuguese pudim fla, inventing a steamed Thai flan, sangkhya. See flan (pudím). She also recreated caramel custard, but Thais later changed her recipe, using whole eggs instead of egg whites and baking the dessert in ordinary terracotta pots instead of rare metal pans, calling it khanom moh kang (pot for making curry).

Guimard also recreated Japanese-European sponge cake, or kasutera, which the Thais called khanom foo (light and airy). Her Bengalese background liberated her to invent sweets using tropical ingredients. One magnificent creation was luk chob, originally doces finos from Portugal. Using sweetened mung bean paste as a substitute for the Portuguese almond paste filling, she shaped the mixture into exquisite miniature fruits and flowers encased in thin floury paste, sweetened with sugar and coconut milk, and scented with jasmine water. They were painted with natural dyes to resemble the real flowers and fruit.

Maria Guimard’s innovations created a sensation among her assistants, who duplicated her recipes at home, even though it was forbidden and considered a sacrilege. The temptation not to eat them was too great. Eventually, sweets were made in larger quantities as offerings during special ceremonies. Afterward, in order to not waste them, they would be served to guests and family members. And by the eighteenth century, Bangkok had many sweet markets selling confections made not only by Thais, but by Chinese, Indians, and European settlers as well.

Chakri Kingdom (1782 to Present)

By the beginning of the Chakri dynasty in the eighteenth century, countless new sweets had been invented, mostly in the royal courts. Each day the king was served a dessert tray with at least five kinds of exquisitely shaped sweets, selected for their complementary tastes and appearances. A profusion of delicacies was swathed in aromatic infusions and natural colorings that incorporated perfumed blossoms, herbs, barks, and smoke from scented candles. See aroma and food colorings. Ice shipped from Singapore for the first time during the reign of Rama IV (1851–1868) was used to cool the perfumed syrups, creating new sweets for the king’s table.

Commoners also created sweets, using regional ingredients. Some reinvented royal recipes by substituting ordinary ingredients for rare and expensive ones. A good example is sweet and creamy sticky rice. Imaginative toppings invented by commoners—including one made with sweet-savory dried shrimp perfumed with kaffir lime threads—garnished this adaptation of a court confection. And yet, for the Thais, sweets remained precious, gracing the tables of the king and wealthy aristocrats. Fruits remained the commoners’ choice, served at the end of the meal to cleanse the palate. See fruits.

In the twentieth century, prosperity and Westernization revolutionized the culture of sweets. While traditional and ancient Thai sweets continue to be imbued with symbolic and religious meanings and served at rituals and ceremonies, they are no longer considered sacred. Instead, sweets are meant to be enjoyed by everyone and for all occasions. Today the Thais display savoir-faire and a taste for a modern lifestyle by emulating the latest fads from America and Europe. Specialty shops selling expensive and exquisitely baked pastries, such as chocolate and Japanese cakes with a Western twist, are popular. Sweets are not eaten merely as desserts but are identified by trendsetters who can afford the latest imported delicacies. In twenty-first-century Thailand, sweets have become the symbol of fashionable taste.

See also egg yolk sweets and nanbangashi.

tiramisù is a dessert made of coffee-soaked ladyfinger cookies (savoiardi) with mascarpone cheese, cocoa powder, eggs, liqueur, and sugar. Its name, tiramisù (tira mi sù), means “pick-me-up,” perhaps a reference to the effect of the caffeine in the espresso and cocoa powder used in the recipe. The dessert is made in nearly a hundred variations, and although it is a kind of zuppa inglese, an old dish related to the trifle, in its present form tiramisù is a relatively recent invention—the first written mention by name in any language dates only to the 1980s. See zuppa inglese.

Tiramisù is thought by many to have been invented in the Veneto region of Italy in the 1960s. The Washington Post writer Jane Black attributes its invention there in 1969 to Carminantonio Iannaccone, a baker who worked as a chef in Treviso (Veneto). Gino Santin, in his La Cucina Veneziana (1988), attributes the dessert’s invention to Alfredo Beltrame, the owner of El Toulá restaurant in Treviso. But there are additional claims, one of the best supported being that of another Treviso restaurant, Le Beccherie (now closed), where owners Aldo and Ada Campeol and their pastry chef Roberto Linguanotto are said to have invented the dessert in 1970. Tiramisù’s original creation is also claimed by regions outside the Veneto, the most important being Friuli Venezia-Giulia, where the heirs to the restaurant Il Roma di Tomezzo (also now closed) have initiated a lawsuit to prove that their tiramisù predates all others.

However, most culinary invention stories are apocryphal, as dishes tend to evolve rather than be invented. Legend has it that the antecedent of tiramisù may be the sweet known as dolce del principe, found in Lombardy, Emilia, Tuscany, and the Veneto, born perhaps as part of the banquet celebrating the visit of the grand duke of Tuscany, Cosimo III de’ Medici, to the city of Siena in the 1570s. The present-day popularity of tiramisù may be due to the relative ease of its preparation, which increased in the early 1980s with the availability of commercial mascarpone cheese and its subsequent export to the United States.

toffee, in Britain, denotes confections based on sugar, often brown, boiled with golden syrup or molasses-dark black treacle, and with milk, butter, or cream, to between 284° and 309°F, or 140° to 154°C (soft to hard crack). See stages of sugar syrup and sugar. Its color varies from medium to dark brown, and its texture is hard. Toffee boiled to higher temperatures is brittle enough to break but still chewy when eaten. Closely related to caramels and butterscotch, toffee provides a flavoring for sweet sauces or sticky toffee pudding, and small pieces add interest to ice creams. See butter; caramel; and sticky toffee pudding. Chewy varieties are included in chocolate bars. The toasty flavor that characterizes toffee is produced by the Maillard reaction, which occurs when sugars and proteins (from the dairy products) are heated together at high temperatures. See maillard, henri. Graining (recrystallization of the sugar) is discouraged, often by the addition of tartaric or other acid, except in a handful of recipes associated with Scotland and closely related to fudge or tablet. See fudge. Tablet is similar to fudge but has a harder texture and snaps satisfyingly; however, it still has the grained texture of fudge.

Toffee is made both at home and commercially. Glucose, corn syrup, and vegetable fats such as palm oil find their way into recipes used in industry, as do flavorings such as lemon, mint, vanilla, rum, and banana. See corn syrup and glucose. Nuts, especially almonds, Brazil nuts, or coconut, can be stirred in. See coconut and nuts. Homemade toffee is poured into trays to set. Commercially produced toffee used to be presented this way in Britain and was broken in the shop using a special hammer, but hygiene regulations now discourage this practice. Industrially produced varieties are frequently cut into small pieces and individually wrapped for sale as toffees.

Toffee remains popular in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand. In North America a hard, buttery candy with almonds is known specifically as English toffee (just as chewy milk and sugar confections used to be known as “American caramels” in Britain). As a class of confectionery, it is less general in the non-Anglophone world, although some items, such as Dutch hopjies, are similar.

Cinder toffee or honeycomb toffee (known as hokey pokey in New Zealand) is a special type, made by boiling sugar to the crack stage and adding vinegar and bicarbonate of soda immediately before pouring. This addition makes the mixture foam, creating a distinctive airy texture. Honeycomb toffee is used commercially as the filling for a popular chocolate bar known as a Crunchie in the United Kingdom and Violet Crumble in Australia. It has a special association with the Ould Lammas Fair at Ballycastle in Ireland, where it is known as “yellowman.”

Taffy is recorded as an earlier version of the word “toffee”; dictionary definitions suggest a possible link to a sugar-refining term, “tafia,” indicating the point at which boiling molasses would set to a hard cake. See taffy. Taffy survived as a name in Wales, and in the United States, sometimes in reference to a pulled version of the sweet; in both countries a taffy pull was a form of evening entertainment into the twentieth century.

Everton toffee (once associated with Everton, now a suburb of Liverpool) is claimed to have originated in the late eighteenth century with a family recipe originally belonging to one Molly Bushell. The cookbook author Eliza Acton included recipes for it in her Modern Cookery of 1847, showing it as similar to modern butterscotch and flavored with lemon or ginger. Nearly 40 years later, in the Confectioner’s Hand-Book (ca. 1881), E. Skuse wrote, “I do not think I could select a better, older, or more popular sweet than Everton toffee to commence my recipes, because it is a toffee which is known all over the world; it is a great favorite with young and old.” Only the presentation distinguished this type of toffee from butterscotch. See butterscotch.

Other than these mentions, the history of toffee remains obscure. Recipes for it are notable by their absence from printed confectionery books prior to the mid-nineteenth century. A hard texture seems to have been the most consistent feature. Among Skuse’s recipes are rose or lemon toffee, based on white sugar. Neither involves dairy products, a usage suggesting that the term “toffee” had a wider application relating to sugar boiled at a high temperature (the term “toffee apple” for a fresh apple dipped in sugar boiled to hard crack may reflect this). Perhaps other names were used for toffee-type confections. Skuse also mentions “stickjaw” (toffees are notorious for welding one’s teeth together), made from boiled sugar and coconut and popular among London children; “hardbake,” a hard sweet including almonds, possibly the ancestor of North American “English toffee”; and “tom trot,” made from boiled molasses. See molasses. Tim Richardson, in Sweets: A History of Temptation (2002), quotes a confectioner from 1864 who remarked that the latter two treats were popular everywhere in England. Although toffee became an everyday sweet, in northern England hard toffee made with black treacle or molasses had, until a few decades ago, a distinct association with the time around Guy Fawkes Night (5 November); and an early nineteenth-century Scottish source refers to “taffie” as treacle and flour boiled together and eaten at Halloween. See halloween.

Toffees packed in brightly colored tins were enormously popular in early- and mid-twentieth-century Britain, as they were an inexpensive luxury. They were produced by the ton by several large companies, such as Sharp’s, Bluebird, and Mackintosh (later part of Rowntree-Mackintosh, a brand now subsumed into Nestlé). The tins were often treasured by their owners long after the contents were consumed, and many survive as collectors’ items.

See also hard candy.

Tootsie Roll is a classic, grainy, cocoa-flavored taffy. It is widely believed that Tootsie Roll was invented in 1896 by the Austrian-born immigrant Leo Hirschfeld, who sold the candies in his Brooklyn candy shop, and later merged with a larger candy company to expand his business. However, contemporary records, trademark filings, and advertising suggest that this account is not entirely accurate.

Stern & Saalberg, a midsized New York candy manufacturer, trademarked the name “Tootsie Roll” in 1909; the filing specifies the first use in commerce in 1908. The company marketed the candy heavily beginning in 1910. At that time, Hirschfeld was the head candy maker for Stern & Saalberg, where he had worked since at least 1894. Stern & Saalberg was reorganized in 1917 as The Sweets Company of America; Hirschfeld, who had risen to the position of vice president, left in 1922 and committed suicide in 1924.

Although Tootsie Roll today is considered a children’s candy, in the early decades it was marketed to and enjoyed by both adults and children. Traditionally, chocolate could only be sold in the cooler months. Toostie Roll was appealing as a year-round chocolate alternative. In World War II and later conflicts, Tootsie Rolls were a popular choice for military rations due to their sturdy durability—so much so that some battalions were said to use “Tootsie Roll” as a code name for bullets.

The Tootsie Pop, a hard candy surrounding a soft Tootsie center, was introduced in 1931. It was the first lollipop to contain a candy “prize.” See lollipops. Today, Tootsie Pops and Tootsie Rolls are the flagship products of Chicago-based Tootsie Roll Industries, the direct descendent of Stern & Saalberg.

See nougat.

torte, the German word for gâteau or cake, typically designates a festive, fancy, round concoction, usually multilayered and filled. It thus stands in contrast to the French tarte (thin and mostly involving fruit of some kind) and German Kuchen, a simpler affair. See kuchen and tart. In Germany today, Torten are often composed of several sponge cake layers (sometimes sitting on a thin shortcrust base) spread with buttercream or whipped cream, or some variation of them. See cream and sponge cake. Glazed with cream or jam (or both), or coated with a thin sheet of marzipan, they are typically garnished with chocolate sprinkles, fruit, nuts, or small marzipan figures. See marzipan and sprinkles. Comparable American-style cakes typically involve much more sweet icing or frosting. See icing. Some French gâteaux, for example the Opéra, bear some similarity to Torten; however, the French term is much looser in meaning and may refer to a wide variety of pastries. The most popular and best-known tortes are arguably the Hungarian Dobos torte (multiple thin sponge cake layers alternating with chocolate buttercream and topped with caramel) and German Black Forest cake. The Austrian Linzer torte is somewhat atypical, resembling a tart more than a cake, and the Viennese Sachertorte consists of a chocolate cake spread with apricot jam and glazed with chocolate icing. See black forest cake; dobos torte; linzer torte; and sachertorte.

The late Latin word torta stood for a flat, round bread, which spawned many variations throughout Europe, such as the French tarte and tourte (meat or fish pie, pastry with fruit or jam) and the Italian torta. Today, the latter designates a simple open or covered pie, usually with a savory filling (the open sweet version is generally called a crostata). But during the Renaissance these sorts of baked goods were often very elaborate.

In Germany, the patrician Sabina Welserin from Augsburg showed herself to be a real Torten specialist in her 1553 Kochbuch. For her, as well as for Marx Rumpolt in his Ein New Kochbuch (1581), Turte [sic] tended to be a covered pie, with a savory or sweet filling, often involving fruit and vegetables, but also with cheese or almond paste. See pie. It was baked in a special pan, typically round and with straight sides. Rumpolt’s Hungarian Turte differs from these, however. Based on a fourteenth-century Italian recipe for a torta ungaresca, it consists of 20 or 30 sheets of pastry made from flour and water, each “thin as a veil,” spread with butter or lard, and sitting on top of an apple filling: a kind of apple strudel, in fact. See strudel.

Conrad Hagger offers another rich source on the subject of tortes. His 1718 Neues saltzburgisches Koch-Buch includes over forty recipes (and engravings) for richly, colorfully decorated sweet and savory cakes (among them the first German-language recipes using chocolate). These cakes were clearly also intended to decorate the table along with sugar sculptures, which in turn came to be replaced by porcelain, allowing the pastry makers to concentrate on Torten. See sugar sculpture. As sponge cake became fashionable in the seventeenth century under the guise of the French biscuit, elaborate constructions took the place of the medieval pies of old, with bright, flashy icings or edible lace—styles of decoration that led to the richness of contemporary tortes.

See also cake; cake decorating; and layer cake.

tragacanth is a gum exudate obtained from various species of wild goat thorn (Astragalus spp.) native to the Mediterranean and Middle East. It is most commonly harvested from the Mediterranean species A. massiliensis (Miller) Lam. and from the Asiatic A. brachycalyx Fisch., which grows in Lebanon, Iran, and Syria. Both are dense, thorny shrubs that favor rocky hillsides. The sap exudes naturally from the lower branches in June, and in the heat of the day it coagulates into irregular ribbons and long vermicular strands of dry white gum. In commercial culture, both the lower branches and upper roots are slashed to encourage the release of the sap. Most of the world’s supply currently comes from Iran. It usually appears in commerce as a fine, cream-colored powder. It has also been referred to in culinary literature as Syrian tragacanth, adragant, and gum dragon.

Tragacanth has been used since antiquity in medicine and as a binding agent for making pills, incense, and pomander beads. When the gum is put into water, it swells into a gelatinous mass. Its principal use in confectionery is as a binding ingredient of gum paste and other edible modeling materials. Printed recipes for preparing sugar pastes of this kind first appeared in books of secrets published in the second half of the sixteenth century. Early practitioners usually soaked the gum in rosewater until it formed a thick mucilaginous mass, kneading in powdered sugar to make a thick, pliable paste. William Jarrin (1784–1848), a late Georgian confectioner, invented a specialized press for producing very large quantities of the paste. See jarrin, william alexis. Tragacanth was also employed to bind modeling pastes made with starch, marble dust, plaster, and alabaster for making more durable table ornaments.

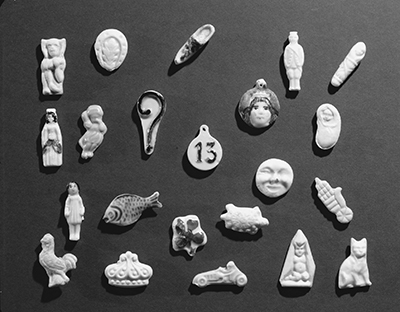

For making very fine gum paste ornaments for pièces montées and cake decorations, confectioners formerly used intricately carved wooden boards. The intaglio motifs were dusted with starch before the paste was pressed in, the excess trimmed off with a knife, and the ornament knocked out by banging the mold on the work surface. Gum pastes used for this purpose needed a high degree of strength and elasticity. A generous proportion of tragacanth to sugar, often as high as one ounce of gum to one pound of sugar powder, was required. See sugar sculpture.

Tragacanth is still an important ingredient of commercial confectioners’ preparations such as petal paste and pastillage, but its high price in recent years has meant that it is commonly substituted with carboxymethyl cellulose (commercially sold as tylose powder, or CMC), which has similar thickening and binding properties.

In the early modern period, tragacanth was also occasionally used as an ingredient in a few specialized baked goods and biscuits, as in this 1699 recipe from the manuscript receipt book of Elizabeth Birkett:

To bake jumbals all of sugar

Take one pound of refined sugar, beat it and searce it finely, put to it a graine of muske and as much ambergrease, and put it into a marble or wooden mortar, and as much Gum Dragon; that hath been steeped all night in rose water, and of the white of an egg well beaten, of them both as much as will wet it. See that you may beat it to a paste, work them up with a little fine sugar, and rowl them, make them into what fashion you please, lay them on a wafer and bake them in a soft oven.

See also cake decorating; pastillage; and sap.

See golden syrup.

tres leches cake (pastel de tres leches in Spanish) is a sponge cake soaked in three milks (tres leches), usually condensed milk, evaporated milk, and cream. The immediate origin is almost certainly a recipe developed or at least disseminated by Nestlé in the 1970s or 1980s in cookbooks and on the backs of labels on cans of La Lechera (the milkmaid) condensed milk. The technique of soaking cakes and tortes in liquids goes back several centuries and is found in English trifle and Italian tiramisù. In the Spanish world, antes (starters) were often liquid-soaked cakes and tortes that bridged the sweet-savory boundary.

By the 1990s, tres leches cake had spread across Latin America. Although most closely associated with Mexico, almost every Latin American country has a version. It is called torta genovesa (torta from Genoa) in Colombia, is cakey rather than sodden in Argentina, is offered at weddings in Panama, and is served direct from the pan in Costa Rica. By the first decade of the twenty-first century, tres leches cake was to be found in the United States, Canada, Australasia, Britain, Germany, and India, in forms varying from cupcakes to ice cream, with and without fruits, and dressed up with frostings of meringue or whipped cream. Supermarkets offered tres leches cake mixes and cans of ready-mixed tres leches.

See also evaporated milk; sweetened condensed milk; trifle; tiramisù; and torte.

trifle is a traditional British dessert consisting of layers of cake or sponge biscuits (often laced with sherry or other alcohol), jam or fruit, crushed macarons or ratafia biscuits, thick rich custard, and a frothy cream or a syllabub topping, often decorated with slivered almonds, angelica, glacé cherries, or the like. There are many variations on this theme. Trifle is best made in a glass bowl so that the decorative layers can be seen. It is often served at parties, celebrations, or festive occasions such as Christmas.

The word “trifle” comes from the Middle English trufle, which in turn came from the Old French trufe (or trufle), meaning something of little importance, a fit subject for mockery, or an idle tale. Originally the culinary meaning of the word trifle was “a dish composed of cream, boiled with various ingredients,” or not far removed from what we call today a fool. See fools. In fact, the words “fool” and “trifle” were used interchangeably for a period, and Florio, in A Worlde of Words, his Italian–English dictionary of 1598, bracketed the two terms when he wrote: “a kind of clouted cream called a foole or a trifle.”

The first known recipe titled “trifle” appeared in Thomas Dawson’s The Good Huswife’s Iewell in 1596. It was made of thick cream, sweetened with sugar, and flavored with ginger and rosewater, more like a fool. This theme continued throughout the seventeenth century, with slight variations in flavorings. However, in 1654, Jos Cooper, cook to Charles I, gave a recipe “To make a Foole,” which bears a closer resemblance to the modern trifle: slices of bread soaked in sack (sherry) at the bottom of the dish, with a custard perfumed with mace and rosewater and sweetened with sugar poured over.

It was not until the mid-eighteenth century that trifle became the complex dessert known today. The first printed recipes for a trifle similar to the modern version appeared in 1751. One was given by Hannah Glasse in the fourth edition of The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, and two appeared in The Lady’s Companion. All three recipes called for Naples biscuits soaked in sack or red wine, layered with custard and topped with syllabub or cream. Glasse garnished her trifle with ratafias, currant jelly, and flowers, while one of the recipes from The Lady’s Companion was garnished with apples, walnuts, or fruit.

After this appearance of the “modern” trifle, other “trifling relations” appeared on the scene, such as whim wham, The Dean’s cream, Swiss Cream, Tipsy cake, Hedgehog cake, and Wassail Bowl. In Victorian times, trifles became even grander and were given imposing titles such an “An Excellent,” “An Elegant,” “A Grand,” and “Queen of Trifles.”

Trifle was enthusiastically welcomed in the United States and was often called by endearing names such as tipsy squire, gipsy squire, or tipsy parson, and it was an American writer, Oliver Wendell Holmes, who in 1861 wrote of “that most wonderful object of domestic art called trifle … with its charming confusion of cream and cake and almonds and jam and jelly and wine and cinnamon and froth.”

See also biscuits, british; custard; flower waters; macarons; and syllabub.

trompe l’oeil (French for “that which deceives the eye”) had its origin in classical Greece and Rome and refers to the depiction of people, objects, or scenes rendered with such meticulous, three-dimensional exactitude that they appear to be real. Simultaneously witty, amusing, and intellectual, trompe l’oeil engages spectators, raising philosophical questions about the very definitions of art and perception. And it embraces not only painting, sculpture, architecture, and the decorative arts, but the culinary arts as well—reaching far above and beyond the mock apple pie recipe on the back of a Ritz Cracker box, a “dirt cake” made from crushed chocolate cookies and presented in a flowerpot (gummy worms optional), or a fondant-swathed custom creation that is more performance piece than dessert.

Culinary deception has had a long, distinguished history, and sophisticated examples continue to surprise and delight the senses. In Japan, which is home to two ancient, interlinked examples of edible trompe l’oeil—mukimono (decorative vegetable sculpting) and modoki, playful-poetic evocations of dishes based in the Buddhist avoidance of meat and fish products out of respect for animal life—sweets are generally eaten as a snack or during tea ceremonies, or presented as gifts. Inspiration has always been taken from the fields, forests, oceans, and seasons, and, according to the Japanese food authority Elizabeth Andoh, the maker must discern how best to convey the essence of the food he or she is preparing. In turn, the recipient provides a vivid imagination and a sense of humor, as well as a full measure of kando (awe) and kansha (appreciation). A number of the steamed rice-and-bean confections called wagashi, which were greatly influenced by foreign trade and the introduction of sugar during the late Muromachi era (1336–1573), imitate something from nature—a baked sweet potato, say, or a chestnut. See wagashi. A more modern (ca. 1909) snack, sold at street stands and food courts, is the beguiling fish-shaped pastry called taiyaki (baked sea bream), molded and cooked in what is basically a waffle iron. Although red bean paste is the traditional filling, other sweet options include custard, fruit, chocolate, and hazelnut spread. (Chinese sausage, bacon, pizza, and cheeseburger are among the savory choices.) One theory as to the enduring appeal of taiyaki stems from the fact that sea bream is an expensive fish. Eating taiyaki, which are cheap to make and buy, is a way for a penny-pinching student or humble salaryman to feel wealthy.

The qualities of awe and appreciation, along with religion, also played an integral part in the trompe l’oeil foods of Europe during the Middle Ages, when dishes disguised as something else relieved the tedium of a Christian church calendar packed with meatless fasting days. Eggs and dairy products were among the foods abstained from, and fast-day recipes in early cookery books might substitute, for instance, almond milk, made from expensive almonds ground and steeped in water, for butter and eggs in cakes and pies.

Edible objects modeled from march-pane (marzipan) and similar pastes, then hardened in an oven, were in evidence at royal feasts in France during the thirteenth century. See marzipan. As the Renaissance took hold, so did the decorative possibilities of sugar, which had spread throughout Europe from North Africa—Egypt, in particular. Sugar’s great popularity could be attributed to three factors: a preference for the whitest (i.e., most processed, thus most expensive) sugar, which was derived both from the Arab style and an age-old association between whiteness and purity; the durability of refined sugar under optimal circumstances; and the ease with which it could be combined with ingredients such as almonds. In Charlemagne’s Tablecloth: A Piquant History of Feasting (2004), Nicola Fletcher takes note of an account of a wedding in Pesaro in 1475: “The entire table service was made out of sugar: plates, cutlery, and even wineglasses that remained waterproof for the duration of the feast (they were broken and eaten afterward), as well as imitation fruit, nuts, and berries for decoration.” Sugar plate, which resembled translucent porcelain, was made by dissolving gum tragacanth in rosewater and lemon juice and pounding the mixture together with egg white and fine sugar to create a smooth, malleable paste, which was then rolled into sheets. See tragacanth. Not only was sugar sweet, Fletcher observes, “it provided endless scope for showing off. The medieval voidee, or final course, became so elaborate that it evolved into an event in its own right. Whereas the words banquet and feast used to mean the same thing, now a feast meant the meat and fish courses and a banquet meant just the sweetmeats.”

Taking pride of place at a banquet (which could be offered any time of day, with or without a preceding feast) was an extravagant edible centerpiece, which ranged from an allegorical representation of a classical figure, say, to one that reflected purported aphrodisiac properties—a gingerbread bull or ram, for instance. See sugar sculpture. Both animals were symbols of lust, and spicy ginger was said to provoke Venus. The sculpted sugar displays, or “subleties,” which marked the courses of a banquet, were often anything but. The sly, winking reference points came in a great variety of forms, including animals, objects, castles, mounted knights, and what the Reverend Richard Warner described in Antiquitates culinarie (1791) as “an extraordinary species of ornament, in use both among the English and the French … representations of the membra virilia, pudendaque muliebira, which were formed of pastry or sugar, and placed before the guests at entertainments, doubtless for the purpose of causing jokes and conversations among them.” The playfulness of the tradition lives on in the gingerbread houses, candy hearts, molded chocolate bunnies and eggs, and wares of erotic bakeshops today.

Another relic is the French bûche de Noël (Yule log cake), a sponge roulade with buttercream “bark,” marzipan holly sprigs, and cunning little mushrooms made of meringue and dappled with cocoa powder. See buche de noël and meringue. Its antecedent is found in the winter solstice celebrations of the Iron Age, when the Celts burned enormous logs decorated with holly, pine cones, or ivy; the pagan ritual was one of many woven into later Christmas celebrations across Europe. The first known recipe for bûche de Noël was published in 1898, in Le mémorial historique et géographique de la pâtisserie, by the Parisian pastry chef Pierre Lacam.

Trompe l’oeil foods are not necessarily about preference, dietary restrictions, wealth, or craftsmanship. American mock foods, for instance, were created by cooks well versed in Old World traditions who had to punt with ingredients more readily to hand. Take apple pie, for instance. Even though recipes for apple pie—not to mention the apples themselves—came to the colonies very early, thrifty cooks in the mid-nineteenth century substituted soda crackers when fresh apples were out of season or when they ran out of their supplies of dried or storage apples. Soda crackers (improved versions of ship’s or soldier’s biscuit) were sturdy and absorbed liquids and flavors well; in addition to being used in apple and mince pies, they were used in all manner of shore dishes, such as hashes, crab or griddle cakes, puddings, and chowders. An “Apple Pie without Apples” appeared in the Confederate Receipt Book of 1863 (in which it appears above “Artificial Oysters,” made with green, or sweet, corn); and in How We Cook in Los Angeles (1894), Mrs. B. C. Whiting referred to it as “California Pioneer Apple Pie, 1852,” noting that “the deception was most complete and readily accepted. Apples at this early date were a dollar a pound, and we young people all craved a piece of Mother’s apple pie to appease our homesick feelings.”

In 1934 the National Biscuit Company (Nabisco) introduced a richer, more delicate cracker called “Ritz” to its Philadelphia and Baltimore markets. Although the name conjured the elite sensibilities of César Ritz, the “king of hoteliers and hotelier to kings,” at 19 cents a box it was advertised as one of life’s most affordable luxuries during the Great Depression. Nabisco’s recipe for mock apple pie, which first appeared on the box in 1935, was an immediate sensation, and the company soon distributed the upscale buttery cracker nationwide. In 1991, after a 10-year hiatus, the recipe was reinstated on the box in response to consumer demand.

The faux filling in a mock apple pie is helped along by cream of tartar (potassium hydrogen tartrate), a white, odorless powder that is a natural byproduct of winemaking. It comes from the tartaric acid found in grapes and other fruits, including apples. But the pie’s enduring appeal is also due in large part to the brain’s effect on culinary perceptions: If it has a golden crust and is sweet and fragrant with cinnamon and lemon, it must be an apple pie. The brain is essentially filling in the blanks—such as true apple flavor and aroma. This phenomenon of how our various senses are stimulated is called “multisensory perception.” See neuroscience. Extremely important to flavor, it has sparked the scientific curiosity of restless, innovative chefs the world over. For almost 40 years there has always been more to a meal than meets the eye at the restaurants (in Los Angeles; Washington, D.C.; Las Vegas; and New York City) of Michel Richard. A former pastry chef with a classical foundation—and arguably the best French chef in the United States—Richard is known for witty, artistic (and often fat-free) presentations that look one way and taste another. One dessert on the dinner menu at Citronelle (now closed) in Washington, D.C., that always elicited gasps of delight was a wake-up call for the eyes and palate: It consisted of chocolate and puff-pastry “bacon”; a “fried egg” made of apricot paste (the yolk) and cream-cheese sauce (the white); slices of lemon pound-cake “toast” with vanilla ice cream “butter”; “hash browns” with caramelized apple standing in for the potato, and raspberry sauce “ketchup”; and, served in a coffee cup, a “cappuccino” of coffee mousse topped with cream and grated chocolate.

In recent years, modernist wizards such as Ferran and Albert Adrià, Andoni Luis Aduriz, Wylie Dufresne, and René Redzepi have embraced the concept of trompe l’oeil. Their transformative offerings may trick the eye, such as Dufresne’s carrot-and-coconut “sunnyside-up egg”; turn a preconceived idea on its head, such as Aduriz’s “carpaccio” of dehydrated watermelon; or create an edible illusion that explores the boundaries between sweet and savory, like Albert Adrià’s “dessert of frozen time,” which he describes as “a dirt road” in autumn. “The dessert, as it was eventually plated, included cherry sorbet, salted honey yogurt, frozen chocolate powder, and spice bread, all evoking one fall moment” (Gopnik, 2011, p. 54). Who is to say they’re not real?

See also banqueting houses; plated desserts; and sweetness preference.

truffles, named after the precious subterranean fungus, are orbed confections made from chocolate ganache, usually enrobed with couverture chocolate. The contrast between the creamy center and the crisp chocolate shell reflects the contrast between the artisanal and the industrial, and between tradition and modernity. Home cooks often simply roll the ganache in unsweetened cocoa powder. See cocoa.

There is documentation that a small amount of pastel trufado, or chocolate truffle, was shipped from Hamburg, Germany, to Guaymas, Mexico, in 1883. As with many well-loved confections, however, truffles have their own origin legends. The most common story credits a certain French confectioner, N. Petruccelli, with creating the first truffle, in Chambéry, France, in 1895. After he ran low on chocolate for the holiday season, he stretched what little he had by mixing small balls of cream, sugar, and powdered chocolate, then dipping them in chocolate. Antoine Dufour popularized the treat when he began selling truffles in a luxury London shop, Prestat, by 1902. Their popularity was established by 1908, when they appeared in the textbook Revised American Candy Maker, and surged again with the introduction of Lindt’s Lindor melting chocolate in 1949. The iconic round shape of Lindt truffles dates to 1967.

Part of the reason for the popularity of truffles is that, while they are a fashionable product, they are flexible enough to allow modifications. Cultural preferences cause American, Swiss, French, and Belgian truffles to vary in size and purity of ingredients. Truffles easily adapt to trends, incorporating new flavors and exotic spices, including curry powder–coconut, matcha green tea, and raspberry–salted licorice. They can be made inexpensively for the mass market by machines that produce 500 pounds of truffles an hour, or carefully shaped by hand to retain a luxurious, artisanal appeal.

See also chocolate, luxury and lindt, rodolphe.

Turkey has been a melting pot of peoples and cultures for thousands of years, from the first farmers of the Neolithic Age to the Hittites, Lydians, and Byzantines. Turkish people from Iran and Central Asia arrived in large numbers after the Iranian Seljuks, a Turkish dynasty, spawned the Anatolian Seljuk state in 1077. The Seljuks were followed by centuries of Ottoman rule (1299–1922), when a sophisticated cuisine evolved that exerted widespread influence across western Asia and eastern Europe. The diversity of Turkish sweets and desserts reflects both the varied roots of the cuisine, ranging from Central Asia and Persia to the Middle East and the Balkans, and the innovative character of Ottoman cuisine. Particularly from the fifteenth century onward, the palace and upper echelons of society could afford fine ingredients and skilled cooks to prepare dishes for those who appreciated good food.

A Turkish street vendor sells lollipops in the form of birds and flowers in Istanbul in the mid-seventeenth century. The lollipop sticks have been inserted into a bottle gourd attached to a long pole. The Dutch caption reads, “Sweets seller, little birds made of sugar.” Dated 1660. © university of manchester

Symbolic significance is attached to sugar in Islamic culture, as shown by two apocryphal sayings ascribed to the Prophet Muhammad: “The love of sweets springs from faith” and “True believers are sweet.” See islam. Mevlana Jalaladdin Rumi, an Islamic mystic who lived in Konya during the Seljuk period, frequently used sugar as a metaphor for God’s love, as in, for example, “I am a mine of sugar, I am the sugarcane.” The Turks gave this spiritual significance a fresh twist by renaming the three-day festival of Eid al-Fitr following Ramadan the Şeker Bayram (Sugar Feast). All over Turkey, sweet foods symbolize happiness and goodwill, so no rite of passage or religious festival is complete without the sweets associated with it. Zerde (saffron pudding) is traditionally served at circumcision feasts, lokma (doughnuts) or irmik helvası (semolina helva) at funerals, sweets such as akide (hard boiled sweets), lokum (Turkish delight) and sugared almonds at mevlits (memorial ceremonies), and aşure (a pudding made of whole-wheat grains, dried fruits, pulses, and rosewater) during the month of Muharrem (especially the tenth day). Nevruz macunu, a sweet paste made of 40 or more spices mixed with sugar, has been distributed in the city of Manisa on Nevruz, the first day of the ancient Persian New Year, since the sixteenth century. Ramadan is not complete without güllaç (a milk pudding made from layers of transparent starch wafers) and baklava, which is also a favorite on just about every festive occasion. Some traditions have lapsed in the twentieth century, such as preparing a crumbly type of flour helva called gaziler helvası (warriors’ helva) for the souls of dead soldiers after battles. See halvah.

Origins

The most ancient Turkish pudding is aşure (related to the English flummery, frumenty, or fluffin; the Greek and Romanian koliva; Armenian anuş abur; Russian kutya; Sephardic Jewish kofyas; and Chinese ba bao zou), whose roots go back to harvest rituals in the Neolithic period when wheat was first domesticated at Karacadağ in eastern Turkey. See wheat berries.

Sweet dishes with a Central Asian stamp are güllaç (“rose food,” the pudding made of transparent starch wafers soaked in syrup or sweetened milk) and sweet pastries like baklava made with layers of thin pastry that were a staple of nomadic Turcoman cuisine. See filo. Pastries soaked in honey or sugar syrup originate in medieval Arab cuisine, itself rooted in earlier Sasanian (224–651) Persian cuisine. In Ottoman Turkish cuisine, some of these pastries, such as yassı kadayıf (a yeast-risen griddle cake soaked in syrup), continued almost unchanged after the medieval period, while new types such as baklava emerged in the early fifteenth century. See baklava. Other contributions of the Persian or Arab cuisines to Turkish confectionery are the earliest sweets—sugar candy, peynir şekeri (pulled sugar), koz helvası (nougat), and sugared almonds—as well as puddings like flour helva, muhallebi (milk pudding made with rice flour), and saffron-scented zerde. Tavukgöğüsü (milk pudding thickened with shredded chicken breast), another dish of Arab origin that later spread to Western European cuisines, survives today only in Turkey, where it is also made in a caramelized version known as kazandibi, an innovation of the nineteenth century. See blancmange.

Keten helva or pişmaniye (from the Persian pashmak), a confection in the form of fine silky threads made of roasted flour and boiled sugar or honey, was introduced from Persia to Turkey in the Anatolian Seljuk era (eleventh to thirteenth centuries). This texture inspired the Turkish name keten helva (linen helva), the Greek molia tis grias (old woman’s hair), and the Chinese “dragon’s beard.” Although keten helva is sometimes likened to candy floss, the ingredients, flavor, and method are very different. Keten helva is made by repeatedly twisting and stretching a ring of pulled sugar or honey in flour roasted in butter, a process requiring a high degree of expertise. The ring should be twisted between 15 to 45 times, each additional twist producing finer strands. Keten helva used to be made at home for winter gatherings of friends and neighbors called helva sohbeti (helva conversation) in towns and villages throughout most of Turkey, but today this custom is dying out, and the sweetmeat is now produced mainly by commercial confectioners.

Provincial specialties include peynirli helva (“cheese helva,” made with semolina and fresh cheese, sometimes then baked); kar helvası (snow helva), made by mixing pekmez, honey or fruit syrup, with crunchy compacted snow; hot baklava with a cheese filling; lollipops in the form of hollow animal figures; demir tatlısı (fritters made with decoratively shaped irons, known as nan-i panjara in Iran and rosettes in the United States); and ice cream thickened with salep (orchid root). The latter, a specialty associated with the city of Kahramanmaraş in southeastern Turkey, is called dövme dondurma (beaten ice cream) because it is beaten with a wooden implement to produce a chewy consistency. It can be stretched into long ropes that take nearly an hour to melt, even in direct sunlight.

Confectionery of many kinds used to be sold by street vendors, but few of these varieties remain today. Among the survivors are macun, a soft toffee in bright colors wrapped around a stick, and kağıt helva (paper helva), consisting of wafers sandwiched together with soft nougat. See nougat and toffee.